Adaptive Ansatz Construction: A Guide to Dynamic Quantum Algorithms for Drug Discovery

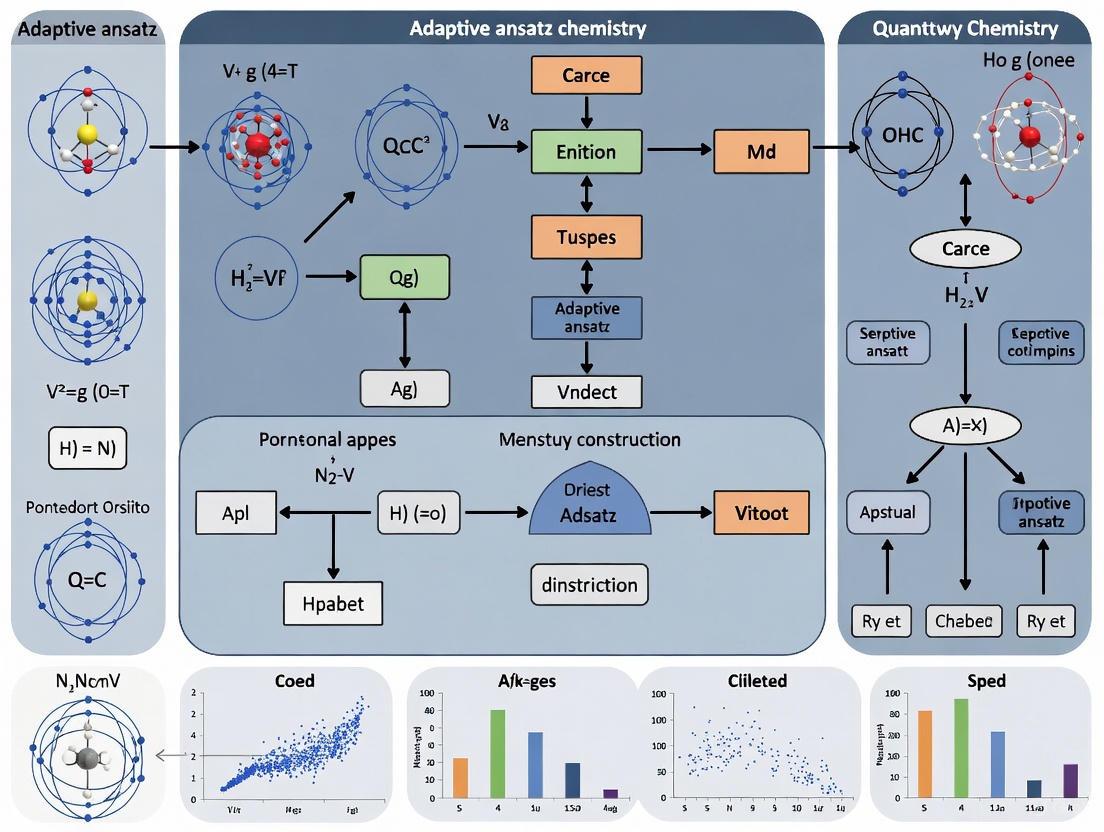

This article explores adaptive ansatz construction, a transformative technique in variational quantum algorithms that dynamically builds quantum circuits for superior performance.

Adaptive Ansatz Construction: A Guide to Dynamic Quantum Algorithms for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores adaptive ansatz construction, a transformative technique in variational quantum algorithms that dynamically builds quantum circuits for superior performance. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we cover the foundational principles of methods like ADAPT-VQE, detail cutting-edge methodological advances including reinforcement learning and novel operator pools, and provide strategies for troubleshooting critical issues like barren plateaus and high resource costs. The content also includes a comparative analysis validating these approaches against static methods, highlighting their profound implications for accelerating computational tasks in drug discovery and molecular simulation.

What is Adaptive Ansatz Construction? Core Principles and the VQE Foundation

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) represents a cornerstone algorithmic framework designed to leverage the capabilities of contemporary noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) computers. As a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm, VQE strategically partitions computational tasks between quantum and classical processors to find the ground state energy of quantum systems, a fundamental challenge in quantum chemistry, materials science, and optimization problems [1] [2]. The algorithm's primary innovation lies in its use of the variational principle of quantum mechanics, which provides that for any trial wavefunction |ψ(θ)⟩, the expectation value of the Hamiltonian H provides an upper bound to the true ground state energy: E(θ) = ⟨ψ(θ)|H|ψ(θ)⟩ ≥ E₀ [3] [4]. This formulation makes VQE particularly suitable for NISQ devices because it replaces the need for deep, coherent quantum circuits with shorter, parametrized circuits that are iteratively refined by classical optimization routines [4] [2].

The broader thesis context of adaptive ansatz construction research addresses a fundamental limitation of fixed-ansatz VQE approaches: their tendency to encounter barren plateaus in the optimization landscape where gradients vanish exponentially with system size [1] [4]. Adaptive ansatz methodologies dynamically construct circuit architectures based on iterative measurements of the quantum system's response, offering a promising path toward more scalable and noise-resilient quantum simulations [4]. This primer explores both the foundational elements of the VQE framework and the emerging research directions in adaptive ansatz construction that aim to expand the algorithm's applicability to industrially relevant problems in drug development and materials design.

Theoretical Foundations: From Quantum Mechanics to Quantum Circuits

Mathematical Framework of the Variational Principle

The VQE algorithm operationalizes the Rayleigh-Ritz variational principle, which states that the expectation value of a Hamiltonian H in any state |ψ(θ)⟩ is always greater than or equal to the true ground state energy E₀ [3] [2]. Formally, this is expressed as:

E(θ) = ⟨ψ(θ)|H|ψ(θ)⟩ ≥ E₀

The parameters θ are variationally optimized to minimize E(θ), producing an approximation to both the ground state energy and wavefunction [4]. The Hamiltonian H must be expressed in a form measurable on quantum hardware, typically as a weighted sum of Pauli strings:

H = Σᵢ αᵢ Pᵢ

where Pᵢ are tensor products of Pauli operators (X, Y, Z) and identity operators, and αᵢ are real coefficients [5] [2]. For quantum chemistry applications, the molecular Hamiltonian is first expressed in second quantization using fermionic creation and annihilation operators, then mapped to qubit operators using transformations such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev [5] [2].

Algorithmic Workflow

The VQE algorithm follows a structured hybrid workflow that partitions tasks between quantum and classical processors, as illustrated in the following diagram:

The quantum computer's role is exclusively dedicated to state preparation and expectation value measurement, while the classical computer performs the more complex tasks of energy computation and parameter optimization [5] [3] [2]. This division of labor allows VQE to function effectively on current quantum hardware with limited coherence times, as the quantum circuits required for state preparation and measurement are typically shallower than those for quantum phase estimation [4] [2].

Core VQE Components and Implementation

Hamiltonian Formulation and Qubit Mapping

For quantum chemistry applications, the electronic structure Hamiltonian in the second quantized form is:

H = Σₚₕ hâ‚šâ‚ a†ₚ aâ‚ + Σₚâ‚ᵣₛ hâ‚šâ‚ᵣₛ a†ₚ a†₠aáµ£ aâ‚›

where hâ‚šâ‚ and hâ‚šâ‚ᵣₛ are one- and two-electron integrals, and a†and a are fermionic creation and annihilation operators [3]. This fermionic Hamiltonian must be mapped to qubit operators via transformations such as Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev, or parity mapping [3] [2]. For a hydrogen molecule (Hâ‚‚) in a minimal basis set, the resulting qubit Hamiltonian takes the form:

H = -0.0996I + 0.1711Zâ‚€ + 0.1711Zâ‚ + 0.1686Zâ‚€Zâ‚ + 0.0453(Yâ‚€Xâ‚Xâ‚‚Y₃) + ... [5]

This transformation typically results in a Hamiltonian comprising O(Nâ´) Pauli terms for N molecular orbitals, though this can be reduced using techniques like the freeze-core approximation [3].

Ansatz Design Strategies

The choice of ansatz, or parameterized quantum circuit, critically determines VQE performance. The table below compares dominant ansatz classes:

Table 1: Comparison of VQE Ansatz Strategies

| Ansatz Class | Key Features | Typical Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemistry-Inspired (UCCSD) | Physically motivated, preserves symmetries | Molecular ground states, quantum chemistry | High circuit depth, limited scalability |

| Hardware-Efficient | Uses native gates, low depth | NISQ devices, optimization problems | May violate physical symmetries, barren plateaus |

| Adaptive/Genetic | Dynamically grown circuits, multiobjective optimization | Complex systems, hardware-specific implementations | Significant optimization overhead |

Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC), particularly with singles and doubles (UCCSD), provides a chemically motivated ansatz that operates on a Hartree-Fock reference state through exponential excitation operators: |ψ(θ)⟩ = e^(T-T†)|ψ_HF⟩, where T = T₠+ T₂ represents single and double excitation operators [4]. In practice, this is implemented as a quantum circuit using Trotterization, with each excitation operator corresponding to a parameterized quantum gate [5] [4].

Hardware-efficient ansätze prioritize experimental feasibility by constructing circuits from native gate sets and connectivity topologies of target quantum processors [4]. These typically employ layers of single-qubit rotations (Rx, Ry, R_z) and entangling two-qubit gates (CNOT, CZ, or iSWAP), with parameters θ optimized variationally [3] [4]. While offering reduced depth, these ansätze may break physical symmetries and suffer from barren plateaus [4].

Classical Optimizers and Measurement Strategies

The classical optimization component updates variational parameters to minimize the energy expectation value. Gradient-based approaches like SPSA and parameter shift rule are commonly employed, with the latter providing exact gradients for certain gate types [2]. For a parameterized gate U(θ) = e^(-iθ/2 P), where P is a Pauli operator, the parameter shift rule gives:

∇₀f(θ) = ½[f(θ+π/2) - f(θ-π/2)]

This enables exact gradient computation using the same quantum circuit executed at shifted parameter values [2]. Gradient-free methods like COBYLA and NM are also widely used, particularly when measurement noise presents challenges for gradient estimation [3].

Measurement requirements present a significant bottleneck, as each Pauli term in the Hamiltonian requires separate measurement. Measurement reduction techniques include grouping commuting Pauli operators, classical shadow tomography, and leveraging contextual subspace approaches that partition the Hamiltonian into classically simulable and quantum-corrected components [4].

Advanced Methodologies: Adaptive Ansatz Construction

Adaptive Ansatz Framework

Adaptive ansatz construction represents a paradigm shift from fixed to dynamically grown circuit architectures, addressing the fundamental limitations of pre-specified ansätze. The following diagram illustrates the iterative process of adaptive ansatz construction:

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm exemplifies this approach, starting from a simple initial state (typically Hartree-Fock) and iteratively growing the circuit by appending operators from a predefined pool based on gradient criteria [4]. At each iteration, the algorithm measures the energy gradient with respect to each operator in the pool, selecting the operator with the largest gradient magnitude for inclusion:

Oselected = argmaxOᵢ |∂E/∂θᵢ|

where the gradient is typically measured directly on quantum hardware [4]. This process continues until gradients fall below a specified threshold or resource limits are reached.

Constraint Incorporation and Symmetry Preservation

A critical advancement in adaptive ansatz design is the explicit enforcement of physical constraints through penalty terms or symmetry-preserving operator selections. The constrained VQE cost function takes the form:

E_constrained(θ) = ⟨ψ(θ)|H|ψ(θ)⟩ + Σᵢ μᵢ(⟨ψ(θ)|Cᵢ|ψ(θ)⟩ - Cᵢ)²

where Cᵢ represent constraint operators (e.g., particle number, spin) with target values Cᵢ, and μᵢ are penalty coefficients [4]. This approach ensures optimization remains within physically meaningful subspaces, particularly important for molecular systems where symmetry violations can lead to unphysical results [4].

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE extends this framework by constructing hardware-tailored ansätze that respect both physical constraints and device connectivity, significantly reducing circuit depth and improving convergence on real hardware [4]. These methods demonstrate that adaptive construction can simultaneously address problems of expressibility, trainability, and hardware compatibility.

Evolutionary and Multiobjective Approaches

Evolutionary VQE (EVQE) implements genetic algorithms to evolve both circuit structure and parameters, using fitness functions that balance energy minimization with resource constraints [4]. Similarly, Multiobjective Genetic VQE (MoG-VQE) employs Pareto optimization to identify circuits offering optimal tradeoffs between approximation error, circuit depth, and two-qubit gate count [4]. These approaches can automatically discover novel circuit architectures that might be overlooked by human designers, potentially uncovering more hardware-efficient representations of quantum states.

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

Standard VQE Protocol for Molecular Systems

A complete VQE implementation for molecular ground states follows these key steps:

- Molecular Specification: Define molecular geometry (atomic coordinates and species) and electronic structure parameters (basis set, charge, multiplicity) [3].

- Hamiltonian Generation: Compute molecular integrals and construct the second-quantized fermionic Hamiltonian, then map to qubit operators using Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation [5] [3].

- Ansatz Initialization: Prepare the Hartree-Fock initial state and construct the parameterized ansatz circuit, typically UCCSD or hardware-efficient varieties [5] [3].

- Measurement and Optimization: Estimate the energy expectation value through repeated measurements, then classically optimize parameters using methods like SLSQP, COBYLA, or gradient descent [5] [3].

- Verification: Compare results with classical methods such as full configuration interaction (FCI) or coupled cluster to verify accuracy [5].

For the Hâ‚‚ molecule at bond length 0.7414 Ã…, this protocol typically achieves chemical accuracy (1 kcal/mol or ~0.0016 Ha) with a simple ansatz containing just one parameter (e.g., a double excitation gate) [5]. The entire workflow can be implemented using quantum programming frameworks such as PennyLane or Qiskit, with the following code excerpt illustrating key steps:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for VQE Research

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in VQE Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Programming Frameworks | PennyLane, Qiskit, Cirq | Algorithm design, circuit construction, and execution management |

| Classical Optimizers | SLSQP, COBYLA, SPSA, L-BFGS-B | Variational parameter optimization |

| Electronic Structure Packages | PySCF, OpenFermion, Psi4 | Molecular integral computation and Hamiltonian generation |

| Qubit Mapping Modules | Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev, Parity | Fermion-to-qubit operator transformation |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE), Clifford Data Regression | Enhancement of results from noisy quantum hardware |

| Measurement Reduction Tools | Pauli grouping, classical shadows | Reduction of required quantum measurements |

| 3,5-Dichloro-2-hydroxybenzamide | 3,5-Dichloro-2-hydroxybenzamide|CAS 17892-26-1 | 3,5-Dichloro-2-hydroxybenzamide is a chemical intermediate for research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Tris(2,2,6,6-tetramethylheptane-3,5-dionato-O,O')praseodymium | Tris(2,2,6,6-tetramethylheptane-3,5-dionato-O,O')praseodymium, CAS:15492-48-5, MF:C33H57O6Pr, MW:690.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Current Research Landscape and Applications

The VQE framework has demonstrated promising results across multiple domains, with particular impact in quantum chemistry where it has enabled ground-state energy calculations for small molecules including Hâ‚‚, LiH, Hâ‚‚O, and BeHâ‚‚ on quantum hardware [4]. Recent industrial applications include pharmaceutical research, where Google collaborated with Boehringer Ingelheim to simulate Cytochrome P450, a key human enzyme in drug metabolism, with greater efficiency than traditional methods [6]. Materials science represents another fertile application area, with researchers using VQE to investigate lattice models, frustrated magnetic systems, and high-temperature superconductors [4].

The emerging commercial impact of quantum computing is evidenced by market analyses projecting growth to USD 5.3 billion by 2029, with VQE algorithms playing a significant role in near-term quantum applications [6]. Major corporations including JPMorgan Chase and IBM are actively exploring VQE for financial modeling, while national research initiatives are prioritizing quantum simulation for energy and materials applications [6].

Ongoing research addresses critical challenges in VQE implementation, particularly the barren plateau phenomenon where gradients vanish exponentially with system size [1] [4]. Advanced strategies to mitigate this include identity-block initialization, warm-start optimization, and layerwise training techniques [4]. Error mitigation has also seen significant advances, with techniques like Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) and neural network denoising demonstrating substantial improvements in result accuracy on noisy quantum processors [4] [7].

The integration of VQE with machine learning approaches represents another frontier, with variational quantum-neural hybrid eigensolvers (VQNHE) enhancing shallow ansätze with classical neural network postprocessing to achieve improved expressivity and accuracy [4]. These hybrid approaches demonstrate how classical and quantum computational paradigms can be synergistically combined to overcome current hardware limitations.

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver framework establishes a robust methodological foundation for quantum computational chemistry and optimization on NISQ-era devices. Its hybrid quantum-classical architecture effectively balances the strengths of both computational paradigms while mitigating current quantum hardware limitations. The ongoing research in adaptive ansatz construction addresses fundamental challenges in scalability and trainability, promising more efficient and hardware-tailored quantum simulations.

As quantum hardware continues to advance with improvements in qubit count, coherence times, and gate fidelities, the VQE framework is positioned to tackle increasingly complex computational challenges with potential applications in drug discovery, catalyst design, and functional materials development. The integration of adaptive ansatz strategies with error mitigation techniques and machine learning augmentation points toward a future where quantum-classical hybrid algorithms can deliver practical quantum advantage for real-world scientific and industrial problems.

Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) have emerged as leading candidates for achieving practical quantum advantage on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware. At the heart of these hybrid quantum-classical algorithms lies the ansatz—a parameterized quantum circuit that prepares trial wavefunctions for optimizing a cost function, most commonly the energy in quantum chemistry problems. The design of this ansatz critically determines the algorithm's performance, yet presents a fundamental trade-off: it must be sufficiently expressive to capture the solution, while remaining trainable and executable on hardware with limited coherence times and significant error rates.

Static ansätze, particularly the widely adopted Unitary Coupled Cluster with Singles and Doubles (UCCSD), face three persistent challenges that limit their effectiveness on NISQ devices [8]:

- Barren Plateaus: Exponential vanishing of gradients with increasing system size

- Fixed Expressivity: Inability to adapt to strong electron correlation and multi-reference character

- Hardware Inefficiency: Implementation requires deep circuits with prohibitive CNOT counts

This technical guide examines these limitations and frames them within the context of a broader research thesis: that adaptive ansatz construction provides a systematic pathway to overcoming these challenges. By dynamically building circuit structures based on iterative, measurement-driven feedback, adaptive methods offer a promising framework for achieving chemical accuracy while maintaining feasibility for near-term quantum hardware.

Fundamental Limitations of Static Ansätze

The Barren Plateau Phenomenon

The barren plateau phenomenon represents perhaps the most significant obstacle to scaling static ansätze. In this regime, the gradient of the cost function vanishes exponentially with increasing system size, effectively stalling optimization [8]. Formally, for a parameterized quantum circuit ( U(\boldsymbol{\theta}) ) with parameters ( \boldsymbol{\theta} ), the variance of the gradient ( \partialk C(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \frac{\partial C}{\partial \thetak} ) scales as:

[ \text{Var}[\partial_k C] \in O\left(\frac{1}{d^n}\right) ]

where ( n ) is the system size (number of qubits) and ( d > 1 ) is a constant related to the circuit architecture. This exponential concentration of gradients near zero makes it impossible to determine productive optimization directions without an exponential number of measurements.

For static ansätze like UCCSD and Hardware-Efficient Ansatze (HEA), the emergence of barren plateaus is particularly pronounced [9]:

- Hardware-Efficient Ansatze: Provably suffer from barren plateaus due to their random circuit structure [9]

- Problem-Inspired Ansätze (UCCSD): While initially designed to incorporate physical intuition, these still face trainability issues as system size increases [8]

- Impact: All known strategies for making variational quantum algorithms provably barren-plateau-free (shallow circuits, local cost functions, identity initialization, symmetry preservation) inadvertently render them classically simulable [9]

Table 1: Barren Plateau Characteristics Across Static Ansatz Types

| Ansatz Type | Gradient Scaling | Classically Simulable? | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware-Efficient | Exponential vanishing ( O(1/d^n) ) | No, but untrainable | None without enabling classical simulation |

| UCCSD | Polynomial to exponential vanishing | For certain system sizes | None general |

| QC-QMC | Context-dependent | Yes | Not applicable |

Fixed Expressivity and Strong Correlation

Static ansätze possess predetermined expressive power that cannot adapt to problem-specific characteristics, particularly the challenging regime of strong electron correlation. The UCCSD ansatz, derived from single-reference perturbation theory, excels where the Hartree-Fock determinant dominates but fails dramatically when multiple electronic configurations contribute significantly [8].

The fundamental limitation arises from the fixed reference state ( |\psi_{\text{ref}}\rangle ) in conventional VQE:

[ |\psi(\boldsymbol{\theta})\rangle = U(\boldsymbol{\theta})|\psi_{\text{ref}}\rangle ]

Typically, ( |\psi{\text{ref}}\rangle ) is chosen as the Hartree-Fock state ( |\text{HF}\rangle ). For molecular dissociation and strongly correlated systems, this single-reference picture breaks down, requiring a multi-configurational approach. UCCSD's cluster operator ( T = T1 + T_2 ) (containing single and double excitations) cannot efficiently generate the necessary multi-reference character from a single determinant [8].

Table 2: Expressivity Limitations in Molecular Systems

| Molecular System | Correlation Regime | UCCSD Performance | Adaptive Solution Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| BeHâ‚‚ (stretched) | Strongly correlated | Fails by several orders of magnitude | Multi-reference with selected determinants [8] |

| Nâ‚‚ (dissociation) | Multi-reference | Inaccurate bond energies | Dynamically expanded reference [8] |

| H₆ (linear chain) | Strong correlation | Poor convergence | Adaptive operator selection [9] |

Hardware Inefficiency and Resource Requirements

The implementation of static ansätze on quantum hardware reveals severe practical limitations in circuit depth, gate count, and measurement requirements. The UCCSD ansatz, when compiled to native gates, produces circuits with CNOT counts that often exceed the capabilities of current NISQ devices.

For a system with ( n ) qubits and ( \eta ) electrons, the number of double excitation operators in UCCSD scales as ( O((n-\eta)^2\eta^2) ), with each excitation requiring a complex quantum circuit for implementation. Recent analyses show [9]:

- LiH (12 qubits): UCCSD requires thousands of CNOT gates

- BeHâ‚‚ (14 qubits): CNOT counts become prohibitive for meaningful optimization

- Measurement Costs: Static ansätze require up to five orders of magnitude more measurements than adaptive approaches for comparable accuracy [9]

These resource requirements directly impact feasibility on current hardware, where decoherence times limit circuit depth and gate fidelity constraints bound overall performance.

Adaptive Ansatz Construction: Methodological Solutions

Cyclic Variational Quantum Eigensolver (CVQE)

The Cyclic Variational Quantum Eigensolver (CVQE) introduces a measurement-driven feedback cycle that systematically expands the variational space in the most promising directions [8]. Unlike static approaches, CVQE incorporates a dynamically growing reference state while maintaining a fixed entangler (e.g., single-layer UCCSD).

The CVQE algorithm proceeds through four key steps in each cycle ( k ) [8]:

Initial State Preparation: [ |\psi{\text{init}}^{(k)}(\mathbf{c})\rangle = \sum{i \in \mathcal{S}^{(k)}} ci |Di\rangle ] where ( \mathcal{S}^{(k)} ) contains Slater determinants from previous cycles

Trial State Preparation: [ |\psi{\text{trial}}(\mathbf{c}, \boldsymbol{\theta})\rangle = U{\text{ansatz}}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) |\psi_{\text{init}}^{(k)}(\mathbf{c})\rangle ]

Parameter Update: Simultaneous optimization of reference coefficients ( \mathbf{c} ) and unitary parameters ( \boldsymbol{\theta} )

Space Expansion: Sampling the optimized trial state and adding determinants with probability above threshold to ( \mathcal{S}^{(k)} )

A distinctive feature of CVQE is its staircase descent pattern, where extended energy plateaus are punctuated by sharp downward steps when new determinants are incorporated. This behavior provides an efficient escape mechanism from barren plateaus by continuously reshaping the optimization landscape [8].

ADAPT-VQE and Resource-Optimized Variants

ADAPT-VQE fundamentally reimagines ansatz construction by dynamically building the circuit through iterative operator selection [9]. The algorithm grows the ansatz according to:

[ U^{(k)}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \left[\prod{\ell=1}^k e^{\theta\ell \tau\ell}\right] U{\text{ref}} ]

where operators ( \tau\ell ) are selected from a predefined pool based on gradient criteria ( \frac{\partial E}{\partial \theta\ell} ).

Recent advancements have dramatically reduced resource requirements [9]:

- CEO-ADAPT-VQE*: Incorporates Coupled Exchange Operators (CEO pool) for improved efficiency

- Measurement Reduction: 99.6% reduction compared to original ADAPT-VQE

- CNOT Reduction: 88% reduction in CNOT count, 96% reduction in CNOT depth

Table 3: Resource Comparison for H₆ (12 Qubits) at Chemical Accuracy

| Algorithm | CNOT Count | CNOT Depth | Measurement Costs | Iterations to Convergence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original ADAPT-VQE | 100% (baseline) | 100% (baseline) | 100% (baseline) | 45 |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | 12% | 4% | 0.4% | 18 |

| UCCSD-VQE | 110% | 115% | 50,000% | N/A (inaccurate) |

AI-Driven Ansatz Generation

The integration of generative artificial intelligence with quantum algorithm design represents a cutting-edge approach to adaptive ansatz construction [10]. The QAOA-GPT framework leverages transformer models trained on graph-structured optimization problems to generate problem-specific quantum circuits in one-shot inference, bypassing iterative construction.

Key innovations include [10]:

- Sequence Modeling: Treating quantum circuits as sequences similar to natural language

- Structural Priors: Augmenting with machine learning representations of problem structure

- Gradient-Free Inference: Sidestepping gradient-based optimization at inference time

This approach demonstrates orders-of-magnitude speedups in circuit generation while maintaining solution quality, illustrating how AI can accelerate the ansatz design process.

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Methodology for Comparative Analysis

Benchmarking adaptive versus static ansätze requires standardized protocols across molecular systems and correlation regimes. Key methodological considerations include:

System Selection:

- Weak Correlation: Near-equilibrium geometries of small molecules (LiH, Hâ‚„)

- Strong Correlation: Dissociation limits and stretched bonds (BeHâ‚‚, Nâ‚‚)

- Multi-Reference Character: Symmetric systems with near-degeneracies (H₆ ring)

Convergence Criteria:

- Chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa or 1 kcal/mol) relative to exact diagonalization or FCI

- Resource counting: CNOT gates, circuit depth, total measurement shots

- Optimization iterations and wall-clock time to convergence

Error Mitigation:

- Zero-noise extrapolation for hardware results

- Measurement error mitigation through calibration

- State tomography for wavefunction analysis

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Recent comprehensive studies demonstrate the dramatic advantages of adaptive approaches [8] [9]. For the BeHâ‚‚ dissociation curve, CVQE maintains chemical accuracy across all bond lengths with only a single UCCSD layer, while fixed UCCSD fails dramatically at stretched geometries [8].

The measurement cost advantage is particularly striking. For the H₆ system, CEO-ADAPT-VQE* achieves chemical accuracy with 99.6% fewer measurements than original ADAPT-VQE and five orders of magnitude fewer than static ansätze with comparable CNOT counts [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Adaptive Ansatz Research

| Tool/Category | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Programming Frameworks | Circuit design, simulation, and execution | Qiskit, Cirq, PennyLane, Amazon Braket |

| Classical Optimizers | Parameter optimization in hybrid quantum-classical loops | Cyclic Adamax (CAD), L-BFGS, SPSA |

| Operator Pools | Libraries of generators for ansatz expansion | Fermionic excitation pools, Qubit excitation pools, CEO pools |

| Error Mitigation Tools | Noise suppression and characterization | Zero-noise extrapolation, probabilistic error cancellation, readout mitigation |

| Molecular Integral Packages | Electronic structure input data | PySCF, OpenFermion, Psi4 |

| Convergence Diagnostics | Monitoring training progress and detecting plateaus | Gradient variance estimation, energy variance tracking, reference determinant analysis |

| N,N'-Bis(8-aminooctyl)-1,8-octanediamine | N,N'-Bis(8-aminooctyl)-1,8-octanediamine, CAS:15518-46-4, MF:C24H54N4, MW:398.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Kasugamycin hydrochloride | Kasugamycin hydrochloride, CAS:19408-46-9, MF:C14H26ClN3O9, MW:415.82 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The limitations of static ansätze—barren plateaus, fixed expressivity, and hardware inefficiency—present fundamental challenges for quantum simulation on NISQ devices. Adaptive ansatz construction methodologies directly address these limitations through dynamic, problem-informed circuit generation.

The emerging research consensus indicates that systematic adaptive expansion of the variational space, whether through measurement-driven feedback in CVQE, gradient-informed operator selection in ADAPT-VQE, or AI-generated circuit designs, provides a viable pathway toward practical quantum advantage. These approaches offer:

- Escapes from Barren Plateaus through continuous landscape reshaping

- Multi-Reference Capabilities via dynamically expanded reference states

- Hardware Efficiency through compact, problem-tailored circuits

As quantum hardware continues to mature with increasing qubit counts and improved gate fidelities—exemplified by IBM's 156-qubit Quantum System Two and Quantinuum's H-Series processors with 99.9% two-qubit gate fidelity [11]—the importance of algorithmic efficiency becomes even more pronounced. Adaptive ansätze represent not merely an incremental improvement but a fundamental rethinking of how we design quantum algorithms for the NISQ era and beyond.

The integration of artificial intelligence with quantum algorithm design suggests an exciting future direction, where generative models could automatically discover optimal ansätze tailored to specific problem classes, potentially accelerating the timeline to practical quantum advantage in drug discovery, materials science, and quantum chemistry.

Adaptive quantum circuits represent a foundational shift in quantum computing, moving beyond the paradigm of static, pre-determined quantum circuits toward a dynamic, responsive model. Adaptive quantum circuits are characterized by hybrid quantum-classical programs and algorithms that dynamically modify their structure or parameters in real-time based on intermediate measurement results [12] [13]. This approach represents a significant departure from traditional quantum algorithms, incorporating mid-circuit measurements, conditional logic, and classical feedback loops that operate within the coherence window of the qubits [12]. These capabilities are rapidly evolving from theoretical concepts to practical implementations, becoming critical for scalable calibration, quantum error correction, and enhanced algorithmic performance across multiple quantum architectures [12].

The emergence of adaptive methods addresses a critical challenge in the NISQ (Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum) era: performing meaningful computations with inherently imperfect qubits. Unlike static circuits that execute predetermined sequences of gates regardless of intermediate outcomes, adaptive circuits leverage classical computing resources to make real-time decisions that optimize subsequent quantum operations. This hybrid quantum-classical control paradigm enables quantum processors to overcome some limitations of current hardware by dynamically compensating for errors, optimizing algorithmic pathways, and tailoring computations to specific problem instances [13]. The growing importance of this approach is evidenced by dedicated research conferences, such as the Adaptive Quantum Circuits (AQC) conference, which brings together leading researchers to advance these methods toward practical applications [12] [14].

Core Principles and Mechanisms

Fundamental Components

Adaptive quantum circuits integrate three fundamental technical components that enable their dynamic behavior. The first is mid-circuit measurement, which allows for the interrogation of quantum states at intermediate stages of computation without requiring full circuit execution. These measurements collapse the quantum state but provide crucial classical information that can inform subsequent operations. The second component is classical conditional logic, which processes measurement outcomes to make decisions about future quantum operations. The third is real-time classical feedback, which implements these decisions by adjusting future gate operations or circuit structures within the qubits' coherence time [12] [13].

These technical components work together to create a fundamentally different computational paradigm from static quantum circuits. The real-time adaptation enables circuits to respond to measurement outcomes, effectively creating quantum algorithms whose exact structure cannot be predicted beforehand but emerges during execution. This capability is particularly valuable for optimizing algorithmic performance and implementing error correction protocols that would be impossible with static approaches [12]. The feedback loops typically operate within stringent timing constraints, as the classical processing and decision-making must complete before qubits decohere, requiring optimized control systems and efficient classical algorithms [13].

Comparison with Static Circuit Paradigms

The distinction between adaptive and static quantum circuits manifests in several critical aspects of quantum computation. While static circuits apply a fixed sequence of quantum gates regardless of intermediate computational states, adaptive circuits employ a dynamic sequence that responds to measurement outcomes. This fundamental difference has profound implications for algorithmic design, error management, and resource requirements.

Table: Comparison of Static vs. Adaptive Quantum Circuits

| Feature | Static Circuits | Adaptive Circuits |

|---|---|---|

| Circuit Structure | Fixed, predetermined sequence | Dynamic, responsive to measurements |

| Classical Integration | Limited to pre- and post-processing | Tightly coupled real-time feedback |

| Error Management | Primarily through error correction codes | Real-time compensation and calibration |

| Resource Overhead | Primarily quantum resources | Hybrid quantum-classical resources |

| Algorithm Design | Determined before execution | Emerges during execution based on outcomes |

The adaptive approach offers particular advantages in scenarios where optimal algorithmic paths depend on intermediate results or where real-time error mitigation can extend computational fidelity. For example, in quantum chemistry applications, adaptive circuits can tailor ansatz structures to specific molecular configurations, potentially achieving higher accuracy with fewer quantum resources [15]. Similarly, in error correction, adaptive methods can respond to detected errors in real-time, implementing corrections before they propagate through subsequent operations [16].

Algorithmic Implementation: ADAPT-VQE

Core Algorithmic Framework

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter ansatz Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a groundbreaking implementation of the adaptive construction paradigm for molecular simulations [15]. Unlike conventional VQE approaches that use a fixed, pre-selected wavefunction ansatz (such as UCCSD), ADAPT-VQE systematically grows the ansatz by adding operators one at a time, with the selection dictated by the specific molecule being simulated [15]. This approach generates an ansatz with a minimal number of parameters, leading to shallower-depth circuits that are more suitable for near-term quantum devices.

The mathematical foundation of ADAPT-VQE builds upon but significantly extends unitary coupled cluster theory. While traditional UCCSD employs a fixed ansatz of the form $|\psi^{\text{UCCSD}}\rangle = e^{\hat{T} - \hat{T}^{\dagger}}|\psi_{\text{HF}}\rangle$ with predetermined excitation operators, ADAPT-VQE uses an iterative, adaptive ansatz construction:

$$ |\psi^{(k)}\rangle = e^{\thetak \hat{\tau}k}|\psi^{(k-1)}\rangle $$

where $\hat{\tau}k$ is the operator selected at iteration $k$ from a pool of possible fermionic operators, and $\thetak$ is its associated parameter [15]. This approach constructs a problem-specific ansatz that recovers the maximal amount of correlation energy at each step, resulting in more efficient circuits that require fewer parameters and gates to achieve chemical accuracy.

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The implementation of ADAPT-VQE follows a structured protocol that combines quantum state preparation, measurement, and classical decision-making in an iterative loop. The detailed experimental workflow can be visualized through the following diagram:

ADAPT-VQE Experimental Workflow

The key steps in the ADAPT-VQE protocol include:

Initialization: Begin with the Hartree-Fock (HF) reference state $|\psi0\rangle = |\psi{\text{HF}}\rangle$ and define a pool of fermionic excitation operators ${\hat{\tau}_i}$ [15].

Gradient Evaluation: For each operator $\hat{\tau}i$ in the pool, measure the energy gradient $\partial E/\partial \thetai$ with respect to its parameter. This gradient indicates how much the energy would decrease by adding that operator to the ansatz.

Operator Selection: Identify the operator $\hat{\tau}k$ with the largest magnitude gradient $|\partial E/\partial \thetak|$ [15].

Convergence Check: If the maximum gradient falls below a predetermined threshold $\epsilon$, the algorithm terminates; otherwise, it proceeds.

Ansatz Expansion: Add the selected operator to the circuit: $|\psik\rangle = e^{\thetak \hat{\tau}k}|\psi{k-1}\rangle$.

Parameter Optimization: Optimize all parameters ${\theta1, \theta2, \ldots, \theta_k}$ in the current ansatz to minimize the energy.

Iteration: Return to step 2 and repeat until convergence.

This protocol generates a compact, problem-specific ansatz that typically requires significantly fewer parameters than fixed UCCSD ansatzes while achieving higher accuracy, particularly for strongly correlated systems [15].

Experimental Validation and Performance Metrics

Molecular Simulation Case Studies

The performance of adaptive circuit construction has been rigorously validated through quantum simulations of molecular systems. Numerical experiments comparing ADAPT-VQE with conventional UCCSD approaches demonstrate superior performance across multiple metrics. In simulations of LiH, BeH₂, and H₆ molecules, ADAPT-VQE achieved chemical accuracy with significantly fewer operators and shallower circuit depths [15].

Table: Performance Comparison of ADAPT-VQE vs. UCCSD for Molecular Simulations

| Molecule | Method | Number of Operators | Circuit Depth | Achievable Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH | UCCSD | ~30 | Deep | Approximate |

| LiH | ADAPT-VQE | ~14 | Shallow | Exact (Chemical Accuracy) |

| BeHâ‚‚ | UCCSD | ~90 | Deep | Approximate |

| BeHâ‚‚ | ADAPT-VQE | ~35 | Shallow | Exact (Chemical Accuracy) |

| H₆ | UCCSD | ~150 | Deep | Approximate |

| H₆ | ADAPT-VQE | ~55 | Shallow | Exact (Chemical Accuracy) |

For the LiH molecule, ADAPT-VQE achieved chemical accuracy with only 14 operators, compared to approximately 30 required by UCCSD [15]. This reduction in operator count directly translates to shallower circuits that are more resilient to noise and more feasible on near-term devices. Similar advantages were observed for BeH₂, where ADAPT-VQE required approximately 35 operators versus 90 for UCCSD, and for H₆, where the operator count was reduced from approximately 150 to 55 while maintaining chemical accuracy [15].

Quantum Error Correction Applications

Adaptive construction principles have also demonstrated significant value in quantum error correction (QEC), particularly in the implementation of complex codes like the color code. Recent experimental work on superconducting processors has shown that the color code, which enables more efficient logical operations compared to the surface code, can be realized through adaptive measurement and feedback techniques [16].

In one comprehensive demonstration, scaling the color code distance from three to five suppressed logical errors by a factor of $\Lambda_{3/5} = 1.56(4)$ [16]. This achievement required adaptive protocols for stabilizer measurements and decoding, highlighting the crucial role of dynamic circuit capabilities. Furthermore, logical randomized benchmarking demonstrated that transversal Clifford gates implemented on these adaptive code structures added an error of only 0.0027(3), substantially less than the error of an idling error correction cycle [16].

The experimental implementation involved several adaptive components:

Real-time stabilizer measurement: Adaptive circuits measured weight-4 and weight-6 stabilizers specific to the color code architecture.

Dynamic decoding: Classical processing units performed real-time decoding of stabilizer measurement outcomes to detect and correct errors.

Logical operation adaptation: Based on decoding results, adaptive circuits implemented logical operations such as state teleportation between distance-three color codes, achieving teleported state fidelities between 86.5(1)% and 90.7(1)% [16].

These results establish adaptive quantum circuits as essential components for realizing fault-tolerant quantum computation on superconducting processors in the near future.

Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

Implementing adaptive quantum circuits requires a sophisticated toolkit spanning quantum hardware, classical control systems, and specialized software. The following table catalogues the essential "research reagents" and their functions in experimental realizations of adaptive quantum protocols.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Adaptive Quantum Circuit Experiments

| Component | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Processing Unit (QPU) | Executes quantum circuits with mid-circuit measurement capabilities | Superconducting qubits (IBM, Google) [17] [16] |

| Classical Control System | Provides real-time feedback and conditional logic | Quantum Machines OPX+ [13] |

| Hybrid Compiler | Translates high-level algorithms into executable quantum-classical instructions | Qiskit Runtime, CUDA-Q [14] |

| Operator Pool | Set of candidate operators for adaptive ansatz construction | Fermionic excitation operators [15] |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Reduces impact of noise on measurement results | Dynamical decoupling, Pauli twirling, measurement error mitigation [17] |

| Classical Shadow Protocol | Efficiently extracts information from quantum states | Randomized measurements [17] |

The classical control system represents a particularly critical component, as it must process measurement outcomes and return conditional instructions within the coherence time of the qubits. Systems such as the Quantum Machines OPX+ provide the necessary low-latency feedback (often on the order of hundreds of nanoseconds) to implement non-adaptive circuits [13]. Similarly, error mitigation techniques are essential for obtaining reliable results from current noisy quantum devices, with methods like dynamical decoupling and measurement error correction playing crucial roles in experimental demonstrations [17].

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

Quantum Machine Learning Integration

The integration of adaptive quantum circuits with machine learning techniques represents a particularly promising direction for both enhancing quantum algorithms and applying quantum computing to classical learning tasks. Recent research has demonstrated that classical machine learning (ML) algorithms can effectively process data generated by quantum devices, extending the class of efficiently solvable problems [17].

In one notable application, classical ML models were trained on classical shadow representations of quantum states to predict ground state properties of many-body systems and classify quantum phases of matter [17]. These hybrid approaches successfully addressed problems involving up to 44 qubits by leveraging various error-reducing procedures on superconducting quantum hardware [17]. The experimental protocol involved:

Data Acquisition: Preparing quantum states and performing randomized measurements to obtain classical shadows.

Error Mitigation: Applying techniques including dynamical decoupling, Pauli twirling, and McWeeny purification to refine the quantum data.

Model Training: Using classical ML algorithms (including kernel methods) to learn from the processed quantum data.

Prediction/Classification: Applying trained models to predict properties of new quantum states or classify quantum phases.

This approach demonstrates how adaptive protocols can enhance the utility of near-term quantum devices by combining them with sophisticated classical machine learning techniques.

Geometric Quantum Machine Learning

Another emerging frontier is geometric quantum machine learning (GQML), which embeds problem symmetries directly into learning protocols [18]. This approach has been used to discover quantum algorithms with exponential advantages over classical counterparts, effectively learning BQP≠BPP protocols from first principles [18]. For example, researchers have used GQML to rediscover Simon's algorithm by developing equivariant feature maps for embedding Boolean functions based on twirling with respect to identified symmetries [18].

The adaptive nature of these approaches appears in both the quantum circuit design and the classical post-processing. The research highlights the importance of data embeddings and classical post-processing, in some cases keeping the variational circuit as a trivial identity operator while achieving powerful results through sophisticated classical processing of quantum measurements [18]. This suggests future directions where adaptive circuits may specialize in efficient data generation while classical neural networks handle complex pattern recognition.

Adaptive quantum circuits represent a fundamental advancement in quantum computation, enabling dynamic, responsive algorithms that surpass the capabilities of static approaches. Through techniques such as ADAPT-VQE for molecular simulations, adaptive error correction implementations like the color code, and hybrid quantum-classical machine learning protocols, this paradigm has demonstrated significant advantages in efficiency, accuracy, and practical applicability on near-term devices.

The core innovation of adaptive construction—real-time circuit modification based on intermediate measurements—creates a more natural bridge between quantum and classical computational resources. As quantum hardware continues to advance, with improvements in qubit coherence, gate fidelity, and mid-circuit measurement capabilities, the potential applications of adaptive methods will expand accordingly. Future developments will likely focus on optimizing the division of labor between quantum and classical processors, developing more sophisticated real-time decision algorithms, and creating standardized tools for implementing adaptive protocols across diverse hardware platforms.

For researchers in fields such as drug development, where quantum simulations of molecular systems hold particular promise, adaptive methods like ADAPT-VQE offer a path to more accurate and efficient computations on emerging quantum hardware. The dynamic, problem-specific nature of these approaches makes them uniquely suited to address the complex, correlated quantum systems that are most challenging for classical computation but most relevant to pharmaceutical applications. As the field progresses, adaptive quantum circuits will undoubtedly play an increasingly central role in harnessing the potential of quantum computation for practical scientific and industrial applications.

The pursuit of quantum advantage on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware has catalyzed the development of hybrid quantum-classical algorithms, with the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) emerging as a leading candidate for quantum chemistry and optimization problems [19] [20]. At the heart of every VQE algorithm lies the ansatz—a parameterized quantum circuit that prepares trial wavefunctions for estimating the expectation value of a given Hamiltonian. The central challenge in practical VQE implementation is that fixed-structure ansätze often yield limited accuracy for strongly correlated systems while containing redundant operators that unnecessarily increase circuit depth and susceptibility to noise [21] [9].

Adaptive ansatz construction methodologies represent a paradigm shift from fixed-ansatz approaches by dynamically building problem-tailored quantum circuits. This technical guide examines two pivotal algorithmic strategies advancing this frontier: the gradient-based selection mechanism of ADAPT-VQE and the recently proposed physics-inspired slice-wise initialization. These approaches offer complementary pathways to overcome the critical bottlenecks of Barren Plateaus (BPs) and hardware noise that plague fixed-structure ansätze [9]. By examining their operational principles, resource requirements, and implementation protocols, this review provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for selecting and deploying these advanced techniques across computational chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery applications where quantum simulation promises transformative impact.

Fundamental Principles of Adaptive VQE

Variational Quantum Eigensolver Foundations

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) operates on the variational principle of quantum mechanics, which establishes that for any normalized trial state (|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle), the expectation value of the Hamiltonian (\hat{H}) satisfies (\langle \psi(\vec{\theta})|\hat{H}|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle \geq E0), where (E0) is the true ground state energy [22]. The VQE algorithm implements this principle through a hybrid quantum-classical workflow:

- State Preparation: A parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) (U(\vec{\theta})) prepares the trial state (|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle = U(\vec{\theta})|\psi{\text{ref}}\rangle) from a reference state (|\psi{\text{ref}}\rangle) (typically the Hartree-Fock state in quantum chemistry) [19].

- Quantum Measurement: The quantum processor measures the expectation value (\langle \psi(\vec{\theta})|\hat{H}|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle) by decomposing the Hamiltonian into measurable Pauli operators [23].

- Classical Optimization: A classical optimizer adjusts parameters (\vec{\theta}) to minimize the energy expectation value, with updated parameters fed back into the quantum circuit [19] [20].

This iterative loop continues until convergence criteria are met, yielding an approximation to the ground state and its energy. The accuracy and efficiency of this process critically depend on the ansatz's ability to represent the true ground state with minimal circuit depth [24].

The Barren Plateau Problem and Ansatz Expressivity

A fundamental limitation of fixed-structure, hardware-efficient ansätze is the Barren Plateau (BP) phenomenon, where the cost function gradients vanish exponentially with system size, rendering optimization intractable [9]. This occurs when the ansatz explores regions of Hilbert space that are too extensive relative to the relevant solution subspace. Adaptive construction strategies mitigate BPs by systematically growing the circuit from an initial state, constraining the search to physically meaningful regions of the Hilbert space [9]. This approach simultaneously addresses expressivity (the ability to represent the target state) and trainability (the ability to optimize parameters), which are often in tension for fixed ansätze [24] [21].

ADAPT-VQE: Gradient-Based Adaptive Construction

Algorithmic Framework and Selection Mechanism

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored VQE (ADAPT-VQE) represents a groundbreaking approach that constructs system-tailored ansätze through an iterative, physically-informed process [21] [9]. Unlike fixed ansätze, ADAPT-VQE dynamically assembles circuits from a predefined pool of operators, typically excitation operators in quantum chemistry or spin coupling terms in lattice models.

The algorithm proceeds through the following iterative steps:

- Initialization: Begin with a reference state (|\psi_{\text{ref}}\rangle) (e.g., Hartree-Fock state) and an empty ansatz (U(\vec{\theta})).

Operator Selection: At each iteration (m), compute the gradient (\frac{\partial \langle H \rangle}{\partial \thetai}) for every operator (Ai) in the pool (\mathcal{P}), where (\langle H \rangle) is the expectation value of the Hamiltonian with respect to the current ansatz state [21]. The operator with the largest gradient magnitude is selected:

[ i{\text{max}} = \arg\max{i} \left| \frac{\partial \langle H \rangle}{\partial \theta_i} \right| ]

Ansatz Expansion: Append the corresponding parameterized unitary (e^{\theta{i{\text{max}}} A{i{\text{max}}}) to the circuit:

[ U(\vec{\theta}) \rightarrow U(\vec{\theta}) \cdot e^{\theta{i{\text{max}}} A{i{\text{max}}} ]

Parameter Optimization: Perform a global optimization of all parameters in the expanded ansatz to minimize (\langle H \rangle).

- Convergence Check: Repeat steps 2-4 until gradient norms fall below a threshold (\epsilon), indicating convergence to an approximate ground state [21] [9].

Table 1: ADAPT-VQE Operator Pool Types and Characteristics

| Pool Type | Operators | Qubit Count | Circuit Efficiency | Measurement Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fermionic (GSD) | Generalized Single & Double Excitations | 12-14 qubits | Moderate | High |

| Qubit | Qubit Excitations | 12-14 qubits | High | Moderate |

| CEO | Coupled Exchange Operators | 12-14 qubits | Very High | Low |

Resource Optimization and Recent Advances

Recent research has dramatically reduced ADAPT-VQE's quantum resource requirements. The introduction of the Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool has demonstrated particularly significant improvements, capturing essential physical correlations with fewer operators and measurements [9]. When enhanced with improved subroutines, CEO-ADAPT-VQE* reduces critical resource metrics compared to the original fermionic implementation:

Table 2: Resource Reduction in State-of-the-Art ADAPT-VQE (for LiH, H₆, and BeH₂ Molecules)

| Resource Metric | Reduction Percentage | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| CNOT Count | 88% | 12-27% of original |

| CNOT Depth | 96% | 4-8% of original |

| Measurement Cost | 99.6% | 0.4-2% of original |

These advancements translate to a five-order-of-magnitude decrease in measurement costs compared to static ansätze with comparable CNOT counts, substantially enhancing feasibility for NISQ implementations [9].

Figure 1: ADAPT-VQE Algorithmic Workflow - This flowchart illustrates the iterative gradient-based selection process in ADAPT-VQE, highlighting the critical feedback loop between operator selection and parameter optimization.

Slice-Wise Initial State Optimization: Physics-Inspired Ansatz Slicing

Methodological Approach

Slice-wise initial state optimization represents an alternative adaptive strategy that bridges physics-inspired ansatz design with iterative construction [24]. Rather than selecting operators from a pool based on gradients, this method decomposes a predefined physics-inspired ansatz (e.g., the Hamiltonian Variational Ansatz) into sequential "slices" corresponding to subsets of its operators. Each slice is optimized independently, with parameters fixed before progressing to the next slice, providing an improved initial state for subsequent optimization stages [24].

The algorithmic procedure follows these key steps:

- Ansatz Decomposition: A known physics-inspired ansatz structure with (L) layers is divided into (K) slices, where each slice contains a subset of the total parameterized operations.

- Incremental Optimization: Beginning with only the first slice active, optimize its parameters while treating subsequent slices as inactive (identity operations).

- Parameter Freezing: Once optimization converges for the current slice, fix these parameters at their optimal values.

- Slice Progression: Activate the next slice and optimize its parameters while keeping previously optimized slices fixed.

- Iteration: Continue this process until all slices are incorporated and optimized [24].

This quasi-dynamical approach preserves the expressivity of physics-inspired ansätze while avoiding the measurement overhead associated with operator selection in gradient-based adaptive methods [24].

Comparative Advantages and Implementation

The slice-wise method offers distinct advantages for specific computational scenarios. By optimizing in lower-dimensional subspaces at each stage, it navigates the energy landscape more effectively than full ansatz optimization, which must explore the entire parameter space simultaneously [24]. This sequential optimization provides better parameter initialization for each subsequent stage, potentially avoiding local minima that might trap conventional optimization.

Benchmarks on one- and two-dimensional Heisenberg and Hubbard models with up to 20 qubits demonstrate that slice-wise optimization achieves improved fidelities and reduced function evaluations compared to fixed-layer VQE [24]. The method is particularly valuable when a physically-motivated ansatz structure is known, as it leverages domain knowledge while addressing optimization challenges through its incremental approach.

Figure 2: Slice-Wise Optimization Workflow - This diagram illustrates the sequential parameter optimization approach in slice-wise ansatz construction, demonstrating the incremental activation and fixation of ansatz slices.

Comparative Analysis: Algorithm Selection Guidelines

Performance and Resource Considerations

Selecting between gradient-based ADAPT-VQE and slice-wise optimization requires careful consideration of problem characteristics, available quantum resources, and computational objectives. The following comparative analysis highlights key differentiating factors:

Table 3: Algorithm Comparison: ADAPT-VQE vs. Slice-Wise Optimization

| Characteristic | ADAPT-VQE | Slice-Wise Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Ansatz Structure | Dynamic, problem-tailored | Fixed, physics-inspired |

| Operator Selection | Gradient-based from pool | Predefined by ansatz slicing |

| Measurement Overhead | High (gradient calculations) | Low (no operator selection) |

| Parameter Optimization | Global after each expansion | Sequential with freezing |

| Hardware Efficiency | High with CEO pools | Moderate |

| Best-Suited Applications | Strongly correlated systems, unknown ansatz structure | Systems with known physical ansatz, limited measurement budget |

Implementation Protocols

ADAPT-VQE Experimental Protocol:

- Operator Pool Preparation: Define a complete operator pool (e.g., fermionic excitations, qubit excitations, or CEO pool) [9].

- Gradient Evaluation Circuit: Design quantum circuits to measure gradients for all pool operators simultaneously where possible to minimize measurement overhead [21].

- Measurement Strategy: Implement classical shadow tomography or overlapping measurement techniques to reduce shot count for expectation value estimation [9].

- Convergence Thresholding: Set appropriate gradient norm thresholds (ε) based on desired chemical accuracy (typically 1.6 mHa for chemical applications) [21].

Slice-Wise Optimization Protocol:

- Ansatz Selection: Choose an appropriate physics-inspired ansatz (e.g., Hamiltonian Variational Ansatz for quantum spin models) [24].

- Slice Definition: Decompose the ansatz into logical slices based on physical principles (e.g., by operator type or lattice spatial layers) [24].

- Sequential Optimization Schedule: Implement optimization with increasing slice activation, fixing parameters from previous slices.

- Classical Optimizer Selection: Choose gradient-free optimizers (e.g., COBYLA, BOBYQA) compatible with noisy quantum hardware outputs [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing advanced VQE algorithms requires both computational and theoretical "reagents" that form the essential building blocks for successful experimentation.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Adaptive VQE Implementation

| Reagent Category | Specific Tools | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operator Pools | Fermionic GSD, Qubit Excitations, CEO Pool | Provide operator candidates for adaptive selection | CEO pool reduces measurement costs by 99.6% vs. original ADAPT-VQE [9] |

| Measurement Techniques | Classical Shadows, Overlapping Groups | Reduce shot count for expectation value estimation | Enables practical implementation on noisy hardware [9] |

| Classical Optimizers | Gradient-Free (COBYLA, BOBYQA), Gradient-Based | Adjust circuit parameters to minimize energy | Critical for optimizing high-dimensional parameter spaces [24] [21] |

| Error Mitigation | Zero-Noise Extrapolation, Probabilistic Error Cancellation | Counteract hardware noise effects | Extracts accurate results from noisy quantum computations [19] |

| Quantum Simulators | Cirq, Qiskit, PennyLane | Algorithm development and benchmarking | Cirq provides built-in GridQubits for lattice model implementation [23] |

| Curvulin | Curvulin, CAS:19054-27-4, MF:C12H14O5, MW:238.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 5-Hexenyltrichlorosilane | 5-Hexenyltrichlorosilane, CAS:18817-29-3, MF:C6H11Cl3Si, MW:217.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The algorithmic landscape for adaptive ansatz construction has evolved dramatically from the initial gradient-based selection of ADAPT-VQE to the physics-inspired slice-wise optimization technique. ADAPT-VQE with advanced operator pools (particularly CEO pools) currently offers the most resource-efficient approach for problems without strong a priori ansatz knowledge, while slice-wise optimization provides a compelling alternative when physical insight can guide ansatz design [24] [9].

Future research directions will likely focus on hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of both methodologies, potentially using slice-wise optimization for initial ansatz construction followed by ADAPT-VQE refinement. As quantum hardware continues to evolve with increasing qubit counts and improved gate fidelities, these adaptive techniques will play a pivotal role in enabling practical quantum advantage for real-world computational challenges across drug discovery, materials design, and fundamental physics [24] [21] [9]. The ongoing reduction in quantum resource requirements—demonstrated by the 99.6% decrease in measurement costs for state-of-the-art implementations—suggests that practical application of these algorithms on NISQ hardware is an increasingly achievable goal.

In the pursuit of practical quantum advantage, particularly for quantum chemistry problems such as drug development, variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) have emerged as a leading strategy for the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era. The performance of these algorithms critically depends on the quantum circuit ansatz—the parameterized unitary that prepares the trial state. The fundamental challenge lies in designing ansätze that are simultaneously expressive enough to represent the solution, trainable without encountering barren plateaus, and frugal in their consumption of precious quantum resources. This whitepaper examines how adaptive ansatz construction research is addressing this triple challenge of enhancing expressivity, improving trainability, and reducing quantum resource requirements.

Core Principles of Adaptive Ansatz Construction

Adaptive ansatz construction represents a paradigm shift from fixed, pre-defined circuit architectures to dynamic, problem-tailored circuits built iteratively. The most prominent example is the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) [9]. Unlike static ansätze such as the Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCCSD) or Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA), adaptive methods grow the circuit one operator at a time, selecting each new operator from a predefined pool based on its predicted contribution to minimizing the energy [25] [9].

This approach directly tackles the core challenges:

- Enhancing Expressivity: The circuit structure is not fixed but evolves to capture the specific physics of the problem instance. Recent research, such as the reinforcement learning (RL) framework for molecular potential energy curves, demonstrates learning a mapping from problem parameters (e.g., bond distance) to a problem-dependent quantum circuit. This allows the ansatz to adapt to varying electron correlation regimes across a molecular geometry [25].

- Improving Trainability: By constructing a compact, chemically meaningful circuit, adaptive methods avoid the barren plateau problems that plague overly expressive, hardware-efficient ansätze. The iterative, problem-tailored approach maintains a focus on the most relevant parts of the Hilbert space, leading to better-conditioned optimization landscapes [9].

- Reducing Resource Requirements: The primary resource gains come from generating shallower circuits with significantly fewer CNOT gates and parameters compared to static ansätze like UCCSD. This directly translates to reduced execution time and higher fidelity on noisy hardware [9].

Quantitative Analysis of Resource Reduction

The evolution of ADAPT-VQE variants has led to dramatic reductions in resource requirements. The following table summarizes the performance of a state-of-the-art algorithm, CEO-ADAPT-VQE*, which combines a novel Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool with other algorithmic improvements [9].

Table 1: Resource Reduction of CEO-ADAPT-VQE* vs. Original ADAPT-VQE at Chemical Accuracy

| Molecule | Qubits | CNOT Count Reduction | CNOT Depth Reduction | Measurement Cost Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH | 12 | 88% | 96% | 99.6% |

| H6 | 12 | 85% | 96% | 99.4% |

| BeH2 | 14 | 73% | 92% | 98.0% |

Source: Adapted from [9]

These improvements are not merely incremental. CEO-ADAPT-VQE* achieves a five order of magnitude decrease in measurement costs compared to other static ansätze with competitive CNOT counts [9]. This makes it a compelling candidate for practical applications on near-term hardware.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The ADAPT-VQE Protocol

The standard ADAPT-VQE protocol provides a foundational framework for adaptive ansatz construction [9].

Protocol 1: Standard ADAPT-VQE Workflow

- Initialization: Begin with a simple reference state, often the Hartree-Fock state,

|ψ₀⟩. - Gradient Calculation: For the current ansatz

U(θ)|ψ₀⟩, calculate the energy gradient with respect to each operator in a pre-defined operator pool (e.g., fermionic excitations, qubit operators). - Operator Selection: Identify and select the operator

Aáµ¢with the largest gradient magnitude. - Circuit Growth: Append the corresponding parameterized gate,

exp(θᵢ Aᵢ), to the circuit. Initialize the new parameterθᵢto zero. - Circuit Optimization: Re-optimize all parameters

θin the newly grown circuit to minimize the energy expectation value. - Convergence Check: Repeat steps 2-5 until the energy gradient norm falls below a predefined threshold, indicating convergence.

Advanced Protocol: Reinforcement Learning for Potential Energy Curves

A more advanced protocol uses Reinforcement Learning (RL) to learn a continuous mapping from a Hamiltonian parameter (e.g., bond distance) to a circuit architecture [25]. This is a non-greedy approach that contrasts with the step-wise greedy selection in ADAPT-VQE.

Protocol 2: RL for Bond-Distance-Dependent Circuits

- Problem Formulation: Define the family of Hamiltonians

{HÌ‚(R)}parameterized by bond distanceR. - Agent and Environment: The RL agent is tasked with selecting quantum circuit architectures. The environment is the quantum simulation that returns an energy (or other property) for a given circuit and bond distance.

- Training: The agent is trained on a discrete set of bond distances

{Râ‚, Râ‚‚, ..., Râ‚™}. The goal is to learn a policyf: R → UÌ‚(R, θ(R))that outputs both the circuit structure and its parameters for any givenR. - Generalization: The trained agent can generate circuits for unseen, arbitrary bond distances within the trained interval without retraining, providing continuous access to the wavefunction across the potential energy curve. This method has been demonstrated for systems like lithium hydride (LiH) and an H4 chain [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table details the essential "research reagents" and computational tools in the field of adaptive ansatz construction.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Adaptive Ansatz Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pools | A predefined set of operators (e.g., fermionic excitations, Pauli strings) from which the adaptive algorithm selects to grow the circuit. | The Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool reduces CNOT counts and measurement costs versus fermionic pools [9]. |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | The overarching hybrid quantum-classical algorithm used to optimize the parameterized circuit and compute the ground state energy [25] [9]. | Core computational engine for evaluating the performance of ADAPT-VQE and other adaptive ansätze. |

| Reference State | The initial state for the variational circuit (e.g., Hartree-Fock state). | The all-zero state or a classical approximation to the solution is a common starting point [9]. |

| Classical Optimizer | A classical algorithm (e.g., gradient descent) used to minimize the energy by adjusting the quantum circuit parameters. | A critical component of the VQE optimization loop [9]. |

| Reinforcement Learning Agent | An AI agent that learns to construct quantum circuits by interacting with a quantum simulation environment. | Used to generate bond-distance-dependent circuits for molecular potential energy curves [25]. |

| Graph Coloring Algorithms | A classical computation technique used to minimize measurement overhead by grouping commuting Pauli terms. | Picasso is a memory-efficient algorithm for coloring graphs representing Pauli strings, enabling more efficient quantum simulations [26]. |

| 1-Isomangostin | 1-Isomangostin, CAS:19275-44-6, MF:C24H26O6, MW:410.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (+)-Menthofuran | (+)-Menthofuran, CAS:17957-94-7, MF:C10H14O, MW:150.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Synergistic Advances in Quantum Error Correction

The efficient execution of adaptive algorithms on real hardware depends on robust quantum error correction (QEC). Recent advances in color codes offer a path to reducing the resource overhead for logical qubits. Compared to the well-studied surface code, color codes require fewer physical qubits per logical qubit and enable faster logical operations, such as the single-step Hadamard gate [27]. Furthermore, color codes are a key component of the "cultivation" protocol for efficiently generating magic states (T-states), which are essential for universal quantum computation [27]. Improved decoders, such as the Neural-Guided Union-Find (NGUF) decoder that combines a modified UF algorithm with a lightweight recurrent neural network (RNN), are increasing the accuracy and efficiency of these QEC codes [28]. The relationship between algorithm and hardware advancement is mutually reinforcing.

Adaptive ansatz construction represents a cornerstone in the development of practical quantum algorithms for computational chemistry and drug discovery. By dynamically tailoring the quantum circuit to the specific problem at hand, this research paradigm directly addresses the fundamental challenges of expressivity, trainability, and resource efficiency. The integration of algorithmic innovations—such as the CEO-ADAPT-VQE* protocol and RL-based circuit generation—with hardware-level progress in quantum error correction creates a powerful synergy. This concerted effort is steadily closing the gap towards a demonstrable quantum advantage for simulating molecular systems, a critical step forward for the pharmaceutical industry and materials science.

Building Better Quantum Circuits: Methodologies and Real-World Applications

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a significant advancement in quantum computational chemistry, enabling exact molecular simulations on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. Unlike fixed-ansatz approaches, ADAPT-VQE iteratively constructs a problem-tailored wavefunction ansatz by systematically selecting operators from a predefined pool, leading to compact, shallow-depth quantum circuits. This guide provides a comprehensive technical overview of the ADAPT-VQE algorithm, detailing its core mechanistic principles, implementation variants, and experimental protocols. By framing this discussion within broader research on adaptive ansatz construction, we elucidate how ADAPT-VQE circumvents limitations of pre-selected ansätze and facilitates practical quantum chemical calculations on current hardware.

Quantum simulation of chemical systems stands among the most promising near-term applications of quantum computers [15]. The variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithm for molecular simulations on quantum hardware, operating as a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm where a parameterized wavefunction ansatz is optimized to minimize the expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian [15] [29]. However, the effectiveness of conventional VQE critically depends on the choice of ansatz, which is typically fixed beforehand, leading to approximate wavefunctions and energies and performing poorly for strongly correlated systems [15].

Adaptive ansatz construction addresses this fundamental limitation by dynamically building the wavefunction ansatz tailored to the specific molecular system being simulated. The core principle involves iteratively growing the ansatz by selecting the most relevant operators from a predefined pool at each step, thereby generating an ansatz with a minimal number of parameters and corresponding shallow-depth circuits [15]. This systematic approach ensures that the algorithm recovers the maximal amount of correlation energy at each iteration, ultimately converging to chemically accurate solutions while maintaining feasibility for NISQ devices.

ADAPT-VQE specifically constructs the ansatz through a sequential application of unitary coupled cluster (UCC)-like exponentiated operators:

$$|\Psi^{(N)}\rangle = \prod{i=1}^{N} e^{\thetai \hat{A}i} |\psi0\rangle$$

where $|\psi0\rangle$ denotes the initial state (typically Hartree-Fock), and $\hat{A}i$ represents the fermionic anti-Hermitian operator introduced during the $i$-th iteration, with $\theta_i$ as its corresponding amplitude [30]. This adaptive methodology represents a paradigm shift from system-agnostic to system-tailored ansätze, potentially overcoming the computational bottlenecks associated with strongly correlated molecular systems.

Core Mechanism of ADAPT-VQE

Algorithmic Workflow and Iterative Operator Selection

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm employs a rigorous iterative procedure for constructing the ansatz, with each cycle comprising distinct phases of operator selection, ansatz expansion, and parameter optimization. The workflow is as follows:

Initialization: Begin with an initial reference state $|\psi_0\rangle$, typically the Hartree-Fock determinant, and define a pool of excitation operators $\mathbb{U}$ [15] [31].

Gradient Evaluation: At iteration $N$, for each operator $\mathscr{U}(\theta) = e^{\theta \hat{A}i}$ in the pool $\mathbb{U}$, compute the gradient of the energy expectation value with respect to the operator's parameter, evaluated at $\theta = 0$ [32]: $$ gi = \frac{d}{d\theta} \langle \Psi^{(N-1)} | \mathscr{U}(\theta)^\dagger \hat{H} \mathscr{U}(\theta) | \Psi^{(N-1)} \rangle \Big|_{\theta=0} $$ where $|\Psi^{(N-1)}\rangle$ is the current ansatz wavefunction from the previous iteration.

Operator Selection: Identify the operator $\mathscr{U}^$ with the largest absolute gradient magnitude [32]: $$ \mathscr{U}^ = \underset{\mathscr{U} \in \mathbb{U}}{\text{argmax}} |g_i| $$