Adaptive Variational Quantum Algorithms: Overcoming Noise and Measurement Challenges for Molecular Systems

This article explores the development and application of adaptive variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) for simulating molecular systems, a critical task for drug discovery and materials science.

Adaptive Variational Quantum Algorithms: Overcoming Noise and Measurement Challenges for Molecular Systems

Abstract

This article explores the development and application of adaptive variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) for simulating molecular systems, a critical task for drug discovery and materials science. We first establish the foundational principles of adaptive VQAs, highlighting their advantages over fixed-ansatz approaches for accurately modeling molecular ground states. The discussion then progresses to methodological innovations, including greedy gradient-free optimization and open-system simulations, and their practical applications. A significant focus is placed on troubleshooting the formidable challenges of noise and measurement overhead, reviewing solutions like noise-adaptive strategies and efficient generator selection. Finally, we provide a comparative analysis of algorithm performance and validation techniques on current quantum hardware, offering a comprehensive resource for researchers and development professionals navigating this rapidly advancing field.

The Principles and Promise of Adaptive VQAs for Molecular Quantum Simulation

Variational Quantum Eigensolvers (VQEs) represent a leading hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for determining molecular ground-state energies on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. The algorithm's core principle involves preparing a parameterized wave-function, or ansatz, and variationally tuning it to minimize the expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian [1]. The practical implementation of VQE on current quantum processing units (QPUs), however, faces significant challenges due to hardware noise and the fundamental limitations of commonly used ansatze.

In the NISQ era, quantum hardware is constrained by qubit counts, high error rates, and limited coherence times, which severely restricts the depth and complexity of quantum circuits that can be executed reliably [2] [3]. This review details the intrinsic shortcomings of fixed, or "system-agnostic," ansatze and underscores the necessity of adaptive, problem-tailored algorithms for achieving chemically accurate molecular simulations.

The Fundamental Shortcomings of Fixed Ansatze

Fixed ansatze, whether hardware-efficient or chemically inspired, utilize a predetermined sequence of parameterized unitary operators. This system-agnostic nature leads to several critical limitations that hinder their application for accurate molecular simulations.

- Limited Accuracy for Strong Correlation: Fixed ansatze do not provide a systematic route for the exact simulation of strongly correlated systems, which are common in transition metal complexes and reaction transition states [1].

- Presence of Redundant Operators: By not being tailored to the specific molecule or Hamiltonian, fixed ansatze often contain superfluous operators. These redundant terms increase circuit depth and the number of variational parameters without improving the ground-state approximation, exacerbating the impact of noise on NISQ devices [1].

- Poor Noise Resilience: The increased circuit depth from redundant operators directly translates to longer execution times, during which quantum decoherence and gate errors accumulate. This makes the algorithm output more susceptible to noise, often preventing it from reaching chemical accuracy [2].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Ansatz Strategies for Molecular Ground-State Calculations

| Feature | Fixed Ansatz | Adaptive Ansatz (e.g., ADAPT-VQE) |

|---|---|---|

| System Specificity | System-agnostic, predetermined structure | System-tailored, iteratively constructed |

| Circuit Compactness | Often contains redundant operators | Minimized operator count, reduced depth |

| Accuracy for Strong Correlation | Limited, no path to exactness | Systematically improvable to high accuracy |

| Noise Resilience | Poor due to typically greater circuit depth | Enhanced through shorter, relevant circuits |

| Measurement Overhead | Fixed, can be high | High initial measurement cost for operator selection, but optimized final circuit |

Adaptive VQE Protocols: A Path to Improved Accuracy

Adaptive VQE algorithms, such as the ADAPT-VQE and Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE), have been developed to overcome the limitations of fixed ansatze by dynamically constructing an operator sequence based on the problem Hamiltonian [1].

The ADAPT-VQE Protocol

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm constructs a circuit ansatz iteratively through a greedy procedure. The protocol for a single iteration is as follows.

Experimental Protocol 1: ADAPT-VQE Iteration

| Step | Action | Quantum Resources | Classical Processing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Initialization | Begin with an initial state (e.g., Hartree-Fock). | Prepare ( | \Psi^{(m-1)}\rangle) on QPU. | Access pre-computed Hamiltonian terms. | |

| 2. Operator Selection | For each operator ( \mathscr{U} ) in pool ( \mathbb{U} ), compute gradient: ( \frac{d}{d\theta} \langle \Psi^{(m-1)} | \mathscr{U}(\theta)^\dagger \widehat{H} \mathscr{U}(\theta) | \Psi^{(m-1)} \rangle \vert_{\theta=0} ). | Execute circuits for gradient estimation (requires multiple measurements per operator). | Identify ( \mathscr{U}^* ) with the largest gradient magnitude. |

| 3. Ansatz Expansion | Append the selected operator: ( | \Psi^{(m)}\rangle = \mathscr{U}^*(\theta_{m}) | \Psi^{(m-1)}\rangle ). | Update the parameterized quantum circuit. | Add a new parameter ( \theta_m ) to the optimization space. |

| 4. Global Optimization | Optimize all parameters ( \vec{\theta} = (\theta1, ..., \thetam) ) to minimize ( \langle \Psi^{(m)} | \widehat{H} | \Psi^{(m)}\rangle ). | Repeatedly execute the circuit with different parameters for energy evaluation. | Run a classical optimizer (e.g., COBYLA). |

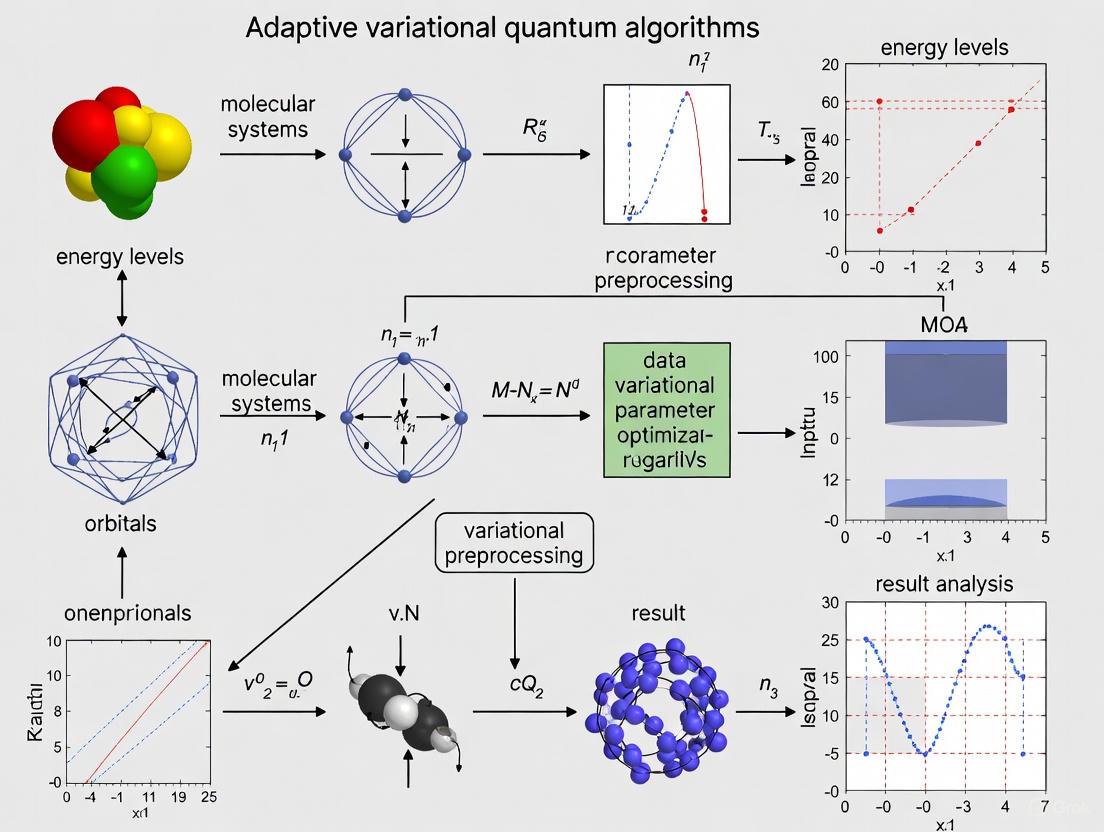

The following workflow diagram illustrates the iterative nature of the ADAPT-VQE protocol.

Case Study: ADAPT-VQE Performance Under Noise

A benchmark study comparing noiseless and noisy ADAPT-VQE simulations for Hâ‚‚O and LiH molecules clearly demonstrates the algorithm's potential and its vulnerability to noise. In noiseless conditions, ADAPT-VQE recovers the exact ground state energy to high accuracy. However, when simulated with a realistic 10,000 shots per measurement, the algorithm stagnates above the chemical accuracy threshold of 1 milliHartree, highlighting the detrimental effect of statistical noise on the optimization process [1].

Hardware Limitations and Error Mitigation

Despite algorithmic advances, the current quantum hardware's noise levels present a formidable barrier. A comprehensive study on calculating the ground-state energy of benzene using an IBM quantum computer concluded that hardware noise produces inaccurate energies, preventing meaningful quantum chemical insights [2]. The noise levels in today's devices are simply too high for the reliable evaluation of molecular Hamiltonians.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Adaptive VQE Experiments

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pool (( \mathbb{U} )) | A pre-selected set of unitary operators (e.g., fermionic excitation operators) from which the adaptive ansatz is built. | Often consists of spin-adapted or qubit-excitation operators to preserve spin symmetry and reduce circuit depth. |

| Classical Optimizer | A numerical algorithm that adjusts the quantum circuit parameters to minimize the energy. | COBYLA is commonly used; its modifications are explored for better noise resilience [2]. |

| Active Space Approximation | Reduces the computational complexity of the molecular Hamiltonian by focusing on a subset of chemically relevant molecular orbitals. | Essential for making problems tractable on limited-qubit devices; accuracy depends on orbital selection [2]. |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | A suite of methods to reduce the impact of noise on measurement results without requiring additional qubits. | Includes zero-noise extrapolation, dynamical decoupling, and measurement error mitigation. |

| Qubit Control & Data Platform | Software for managing calibration data, running experiments, and visualizing results. | Platforms like QubiCSV provide data versioning and visualization to streamline research [4]. |

To navigate the NISQ landscape, researchers must employ a full-stack optimized approach. The diagram below outlines the interconnected components of a modern quantum chemistry simulation workflow, from problem definition to result analysis.

The pursuit of chemically accurate molecular simulations on near-term quantum hardware necessitates a move beyond fixed, system-agnostic ansatze. While adaptive VQE algorithms like ADAPT-VQE offer a principled path to more compact and accurate circuits by dynamically tailoring the ansatz to the molecular Hamiltonian, they too are currently hampered by the high noise levels present in NISQ devices. Future progress hinges on the co-design of more robust adaptive algorithms, advanced error mitigation strategies, and the continued development of hardware with lower error rates and higher qubit coherence times.

The simulation of molecular systems to determine ground-state energies is a cornerstone of computational chemistry and drug discovery, yet it remains profoundly challenging for classical computers due to the exponential scaling of the quantum many-body problem. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) emerged as a leading hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed to leverage Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices for this task [5] [6]. In its standard form, VQE uses a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) to prepare a trial wavefunction, whose energy expectation value is minimized via classical optimization. However, the performance of VQE is critically dependent on the choice of ansatz. "Fixed-ansatz" methods, like the Unitary Coupled Cluster with Singles and Doubles (UCCSD), are often system-agnostic, containing redundant operators that needlessly increase circuit depth and the number of variational parameters—a major liability for error-prone NISQ hardware [1] [7].

Adaptive VQE algorithms address this fundamental limitation by moving away from a fixed ansatz. Instead, they iteratively construct a system-tailored ansatz by selectively adding operators from a predefined "operator pool." This methodology aims to build more compact and accurate circuits by identifying and including only the most physically relevant operators at each step, thereby avoiding the pitfalls of over-parameterization and deep circuits [1] [8] [7]. This document details the core mechanics of these adaptive algorithms, focusing on their iterative construction process and the central role of the operator pool, providing a framework for their application in molecular systems research.

Foundational Adaptive Algorithm: ADAPT-VQE

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) established the paradigm for iterative ansatz construction [7]. Its algorithmic workflow consists of two repeating steps: a greedy operator selection step and a global variational optimization step.

The Iterative Cycle of ADAPT-VQE

The algorithm begins with a simple reference state, typically the Hartree-Fock state. At each iteration ( m ), the algorithm [1] [7]:

Operator Selection: Given the current parameterized ansatz ( |\Psi^{(m-1)}\rangle ), the algorithm evaluates every operator ( \mathscr{U} ) in a pre-defined pool ( \mathbb{U} ). The selection criterion identifies the operator ( \mathscr{U}^* ) that exhibits the largest potential for energy reduction, as measured by the magnitude of the energy gradient with respect to its parameter: [ \mathscr{U}^* = \underset{\mathscr{U} \in \mathbb{U}}{\text{argmax}} \left| \frac{d}{d\theta} \langle \Psi^{(m-1)} | \mathscr{U}(\theta)^\dagger \widehat{A} \mathscr{U}(\theta) | \Psi^{(m-1)} \rangle \Big \vert {\theta=0} \right|. ] This operator is appended to the ansatz, creating a new, expanded circuit ( |\Psi^{(m)}\rangle = \mathscr{U}^*(\thetam) |\Psi^{(m-1)}\rangle ).

Global Optimization: The parameters of the new, expanded ansatz—including the new parameter ( \thetam ) and all previously optimized parameters—are globally optimized to minimize the energy expectation value: [ (\theta1^{(m)}, \ldots, \thetam^{(m)}) = \underset{\theta1, \ldots, \theta_m}{\operatorname{argmin}} \langle \Psi^{(m)} | \widehat{A} | \Psi^{(m)} \rangle. ] This cycle repeats until a convergence criterion (e.g., an energy threshold) is met.

The following diagram illustrates this iterative workflow:

The Operator Pool

The operator pool ( \mathbb{U} ) is a critical component that defines the search space for the adaptive algorithm. For quantum chemistry applications, common pools are composed of fermionic or qubit excitation operators [8] [7].

- Fermionic Pool: This pool consists of spin-complemented (or non-complemented) single, double, and sometimes higher excitation operators. A generalized single excitation operator is of the form ( \taup^q = \hat{a}q^\dagger \hat{a}p - \hat{a}p^\dagger \hat{a}q ), and a generalized double excitation is ( \tau{pq}^{rs} = \hat{a}r^\dagger \hat{a}s^\dagger \hat{a}p \hat{a}q - \hat{a}p^\dagger \hat{a}q^\dagger \hat{a}r \hat{a}s ), where ( p, q, r, s ) are arbitrary spin orbitals. The "restricted" pool, which only includes excitations from occupied to virtual orbitals relative to the Hartree-Fock reference, is often used to reduce computational cost [8].

- Qubit Pool: To reduce circuit depth, operators can be transformed into qubit representations (e.g., via Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformations) and then grouped into mutually commuting sets. The Qubit-Excitation-Based (QEB) pool uses operators like ( \hat{a}q^\dagger \hat{a}p \rightarrow \frac{1}{2}(Xp Xq + Yp Yq) ) and similar for doubles, which can yield shallower circuits [8].

Table 1: Common Operator Pools in Adaptive VQE

| Pool Type | Operator Examples | Key Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fermionic (UCCSD-like) | τₚq = a†_q aₚ - a†_ₚ a_qτₚqʳˢ = a†_r a†_s aₚ a_q - h.c. |

Physically motivated, respects chemical symmetries like particle number. | Can lead to deep quantum circuits after compilation to native gates. |

| Qubit-Excitation-Based (QEB) | (Xâ‚š X_q + Yâ‚š Y_q)/2Various Pauli string combinations |

Can be compiled into shallower circuits compared to fermionic operators. | May require specialized grouping or tomography protocols. |

| Restricted Pool | Excit. from occupied to virtual orbitals only. | Smaller pool size, faster gradient screening. | May miss some correlation effects in strongly correlated systems. |

Key Algorithmic Advances and Comparative Analysis

While ADAPT-VQE is powerful, its practical implementation on NISQ devices is challenging due to the significant measurement overhead required for gradient evaluation and the optimization of high-dimensional, noisy cost functions [1]. This has spurred the development of several advanced algorithms.

Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE)

The GGA-VQE algorithm simplifies the ADAPT-VQE workflow by replacing the gradient-based selection rule with a gradient-free, greedy global optimization [1]. Instead of calculating gradients for all pool operators, it directly tests each operator by temporarily adding it to the circuit, performing a global optimization of its parameter (often using a quantum-aware method), and then permanently adding the operator that yields the lowest energy. This approach has demonstrated improved resilience to statistical sampling noise, a common issue when a limited number of measurements ("shots") are used to estimate expectation values on quantum hardware [1].

Overlap-ADAPT-VQE

A significant challenge for energy-based growth is stagnation in local minima, leading to over-parameterized ansätze. Overlap-ADAPT-VQE addresses this by changing the growth objective [8]. Rather than growing the ansatz purely by minimizing energy, it systematically builds a wavefunction that maximizes its overlap with an intermediate target wavefunction that already captures electronic correlation. This target can be, for example, a classically computed wavefunction from a Selected Configuration Interaction (SCI) calculation. The resulting compact ansatz is then used to initialize a final ADAPT-VQE optimization. This strategy avoids initial energy plateaus and produces significantly more compact circuits, especially for strongly correlated systems like stretched molecular bonds [8].

ExcitationSolve is a fast, globally-informed, gradient-free optimizer specifically designed for ansätze containing excitation operators, whose generators satisfy ( Gj^3 = Gj ) (a class that includes standard fermionic excitations) [9]. For a single parameter ( \thetaj ), the energy landscape is a second-order Fourier series: ( f{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\thetaj) = a1 \cos(\thetaj) + a2 \cos(2\thetaj) + b1 \sin(\thetaj) + b2 \sin(2\theta_j) + c ). The ExcitationSolve algorithm determines the five coefficients by evaluating the energy at at least five different parameter values. It then classically computes the global minimum of this reconstructed analytic function. This method is hyperparameter-free and highly resource-efficient, as it finds the global optimum along a parameter direction using a number of energy evaluations comparable to what gradient-based methods need for a single update [9].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Adaptive VQE Algorithms

| Algorithm | Operator Selection Mechanism | Optimization Strategy | Key Advantage | Demonstrated Molecular Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADAPT-VQE | Gradient magnitude of pool operators [1] [7]. | Global optimization of all parameters after each addition [1]. | System-tailored, compact ansätze. | LiH, BeH₂, H₆ [7]. |

| GGA-VQE | Greedy evaluation: directly tests and optimizes each candidate operator [1]. | Gradient-free, analytic, or quantum-aware optimization. | Improved resilience to measurement noise. | Hâ‚‚O, LiH, 25-body Ising model [1]. |

| Overlap-ADAPT-VQE | Maximizes overlap with a pre-computed target wavefunction [8]. | Subsequent energy minimization with the overlap-built ansatz. | Avoids local minima; produces ultra-compact circuits. | Stretched BeH₂, linear H₆ chain [8]. |

| ExcitationSolve | Compatible with gradient or greedy selection methods. | Globally minimizes analytic 1D landscape per parameter [9]. | Fast, resource-efficient optimization for excitations. | Molecular ground state benchmarks [9]. |

Experimental Protocols for Algorithm Implementation

Protocol 1: Implementing a Basic ADAPT-VQE Simulation

This protocol outlines the steps for a classical numerical simulation of ADAPT-VQE, a prerequisite for hardware deployment.

- Problem Specification: Define the molecular system (e.g., geometry, basis set like STO-3G) and compute the electronic Hamiltonian in second quantization using a classical quantum chemistry package (e.g., PySCF).

- Qubit Mapping: Transform the fermionic Hamiltonian into a qubit Hamiltonian using a mapping such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev (e.g., with OpenFermion [8]).

- Initialize Algorithm: Set the reference state to ( |\psi_{\text{HF}}\rangle ) and initialize an empty ansatz circuit.

- Iterative Loop: a. Gradient Calculation: For each operator ( \mathscr{U}k ) in the chosen pool, compute the gradient ( gk = \left| \frac{d}{d\theta} \langle \psi | \mathscr{U}k^\dagger(\theta) H \mathscr{U}k(\theta) | \psi \rangle \right|{\theta=0} ). This typically requires measuring commutator relationships on the quantum computer or emulator. b. Operator Selection: Identify the operator ( \mathscr{U}^* ) with the largest ( |gk| ). c. Circuit Update: Append ( \mathscr{U}^*(\theta_{\text{new}}) ) to the current ansatz circuit. d. VQE Optimization: Use a classical optimizer (e.g., BFGS, COBYLA, or a quantum-aware optimizer like Rotosolve/ExcitationSolve) to minimize ( \langle \psi(\vec{\theta}) | H | \psi(\vec{\theta}) \rangle ) with respect to all parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) in the expanded ansatz.

- Convergence Check: If ( |\Delta E| < \epsilon ) (e.g., ( \epsilon = 10^{-6} ) Ha) for several iterations or a maximum iteration count is reached, terminate. Otherwise, return to step 4a.

This protocol is designed for enhanced performance on noisy quantum hardware or emulators.

- Steps 1-3: As in Protocol 1.

- Iterative Loop: a. Greedy Operator Trial: For each operator ( \mathscr{U}k ) in the pool: i. Construct a temporary circuit: ( |\psi{\text{temp}}(\phi)\rangle = \mathscr{U}k(\phi) |\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle ). ii. Use the ExcitationSolve method to find the optimal ( \phi^* ) for this one-parameter problem: evaluate the energy at (at least) five points for ( \phi ), reconstruct the analytic energy landscape, and classically compute the global minimum ( \phi^* ) [9]. iii. Record the energy ( Ek = \langle \psi{\text{temp}}(\phi^*)| H |\psi{\text{temp}}(\phi^)\rangle ). b. Operator Selection: Permanently add the operator ( \mathscr{U}^ ) that yielded the lowest energy ( E_k ) to the ansatz. Set its parameter to ( \phi^* ). c. Sweeping Optimization: Perform one full sweep of the ExcitationSolve optimizer over all parameters in the now-expanded ansatz.

- Convergence Check: Terminate if the energy reduction from the full sweep is below a threshold.

The logical relationship and resource flow of this protocol is shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Methodological "Reagents" for Adaptive VQE Experiments

| Research Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example Implementation / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Integral Solver | Computes molecular orbitals and the electronic Hamiltonian integrals. | PySCF [8] |

| Fermion-to-Qubit Mapper | Transforms the fermionic Hamiltonian and operators into a Pauli string representation. | OpenFermion [8] (Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev) |

| Operator Pool | The dictionary of operators from which the adaptive algorithm constructs the ansatz. | Restricted/QEB Singles & Doubles [8], Fermionic excitations [7] |

| Quantum Simulator/Hardware | Executes the quantum circuit to measure expectation values. | Statevector simulator (noiseless), QASM simulator (with shot noise), Physical QPU [1] |

| Classical Optimizer | Minimizes the energy with respect to the variational parameters. | Gradient-free (COBYLA, SPSA) [9], Quantum-aware (Rotosolve, ExcitationSolve) [9] |

| Altanserin | Altanserin, CAS:76330-71-7, MF:C22H22FN3O2S, MW:411.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Arvanil | Arvanil, CAS:128007-31-8, MF:C28H41NO3, MW:439.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The simulation of quantum systems, particularly molecular ones, represents a fundamental challenge with profound implications for materials science and drug development. On noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, hybrid quantum-classical algorithms have emerged as the leading paradigm for tackling this challenge [1]. Among these, the variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) has become a cornerstone for finding molecular ground-state energies [10]. However, standard VQE approaches employing fixed ansatze often contain redundant operators, leading to increased circuit depths and optimization difficulties on current hardware [1].

Adaptive variational quantum algorithms represent a significant evolution beyond fixed-ansatz approaches. These methods dynamically construct problem-tailored ansatze by iteratively selecting operators from a predefined pool based on specific selection criteria [11]. The original ADAPT-VQE algorithm demonstrated that this adaptive construction could yield more compact and accurate circuits compared to fixed ansatze like UCCSD [12]. However, the adaptive landscape has since expanded to include diverse families of algorithms, each founded on distinct principles and targeting unique challenges in quantum simulation.

This review explores the key adaptive algorithm families that have emerged beyond the original ADAPT-VQE framework, examining their founding principles, methodological distinctions, and applications to molecular systems research.

Algorithm Families: Founding Principles and Distinctions

Gradient-Informed Greedy Algorithms

Founding Principle: This family, including ADAPT-VQE and its variants, operates on the principle of greedy gradient minimization. At each iteration, the algorithm selects the operator from a predefined pool that demonstrates the largest magnitude gradient of the energy with respect to its parameter, then optimizes all parameters in the growing ansatz [1] [11].

Key Distinctions:

- Operator Selection: Uses the gradient criterion ( \mathscr{U}^* = \underset{\mathscr{U} \in \mathbb{U}}{\text{argmax}} \left| \frac{\partial E}{\partial \theta{\mathscr{U}}} \Big|{\theta=0} \right| ) to identify the most promising operator [1].

- Parameter Recycling: Initializes new parameters to zero and uses optimized parameters from previous iterations as starting points, ensuring monotonic energy improvement [11].

- Avoidance of Barren Plateaus: By construction, these algorithms avoid random initialization in high-dimensional parameter spaces and dynamically create landscapes conducive to optimization [11].

Molecular Applications: Primarily applied to ground-state electronic structure problems for molecules, with demonstrated success for systems like Hâ‚‚, LiH, and Hâ‚‚O [1] [10].

Variance-Based Targeting Algorithms

Founding Principle: Algorithms like adaptive VQE-X are founded on the principle of energy variance minimization rather than energy minimization itself, making them particularly suited for targeting highly excited states and phenomena at finite energy density [12].

Key Distinctions:

- Target Function: Minimizes ( \langle H^2 \rangle - \langle H \rangle^2 ) instead of ( \langle H \rangle ), allowing access to arbitrary eigenstates [12].

- State Agnosticism: Does not rely on initial state proximity to the target state, unlike ground-state methods which often benefit from Hartree-Fock initialization [12].

- Operator Pool Dependence: Performance strongly depends on operator pool choice, with long-range two-body gates accelerating convergence in non-integrable regimes [12].

Molecular Applications: Calculation of highly excited states for studying quantum dynamics, thermalization processes, and finite-temperature properties of molecular systems [12].

Open System Adaptive Simulators

Founding Principle: This family extends adaptive principles to simulate open quantum systems governed by the Lindblad equation, addressing the critical need to model environmental effects on molecular systems [13].

Key Distinctions:

- Density Matrix Formulation: Operates on density matrices rather than pure states to properly describe mixed states and decoherence [13].

- Non-Unitary Operations: Incorporates quantum channels and dissipation processes beyond unitary evolution [13].

- Dynamical Addition: Builds resource-efficient ansatze through dynamical addition of operators while maintaining accuracy throughout time evolution [13].

Molecular Applications: Simulating energy transfer in light-harvesting complexes, modeling solvent effects on molecular reactivity, and studying quantum sensing mechanisms in biological environments [13].

Lookback-Based Adaptive Methods

Founding Principle: These methods implement a "lookback" mechanism that dynamically determines the amount of historical information to leverage at each decision point, balancing bias-variance tradeoffs in sequential learning tasks [14].

Key Distinctions:

- Stability-Bias Tradeoff: Systematically selects window sizes to balance approximation bias against stochastic error [14].

- Empirical Thresholding: Uses data-driven thresholds to determine admissible history windows based on empirical loss comparisons [14].

- Multi-Scale Adaptation: Can operate across different timescales simultaneously through geometric windowing schemes [14].

Molecular Applications: Online optimization of variational parameters in streaming quantum chemistry applications, adaptive error mitigation strategies, and dynamic resource allocation during quantum computations [14].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Adaptive Algorithm Families

| Algorithm Family | Founding Principle | Selection Metric | Target States | Hardware Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-Informed Greedy | Greedy gradient minimization | Energy gradient magnitude | Ground states | High (compact circuits) |

| Variance-Based Targeting | Energy variance minimization | Variance reduction | Highly excited states | Moderate (depends on state complexity) |

| Open System Simulators | Lindblad equation simulation | Fidelity with exact solution | Mixed states | Moderate to low (additional noise terms) |

| Lookback-Based Methods | Historical information optimization | Bias-variance tradeoff | All states (via adaptive optimization) | High (resource-aware) |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Convergence and Accuracy Metrics

Adaptive variational algorithms demonstrate distinct performance characteristics across different molecular systems and target states. Quantitative benchmarking reveals both capabilities and limitations of current approaches.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks Across Molecular Systems

| Molecule | Algorithm | Qubits | Energy Error (mHa) | State Infidelity | Circuit Depth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | ADAPT-VQE | 4 | 0.08 | 1.2×10â»âµ | 12 |

| Hâ‚‚ | Fixed UCCSD | 4 | 0.10 | 1.5×10â»âµ | 16 |

| LiH | ADAPT-VQE | 6 | 0.52 | 8.7×10â»â´ | 41 |

| LiH | Fixed UCCSD | 6 | 0.68 | 1.2×10â»Â³ | 54 |

| Hâ‚‚O | ADAPT-VQE (noiseless) | 8 | 0.45 | 6.3×10â»â´ | 63 |

| Hâ‚‚O | ADAPT-VQE (noisy*) | 8 | 2.85 | 4.1×10â»Â³ | 63 |

| 25-qubit Ising | GGA-VQE | 25 | N/A | Favorable approximation | 110 |

Noisy simulation using 10,000 shots on an HPC emulator [1] *Hardware noise produced inaccurate energies, but the circuit yielded a favorable ground-state approximation when evaluated via noiseless emulation [1]

Resource Scaling and Limitations

The scaling behavior of adaptive algorithms reveals critical insights for their application to larger molecular systems:

- Parameter Growth: ADAPT-VQE shows sub-exponential growth in parameters with system size, though exponentially many parameters may be necessary for individual highly excited states [12].

- Measurement Overhead: Gradient measurements for operator selection require substantial quantum resources, though improved strategies can reduce this overhead [1].

- Circuit Depth: Adaptive methods typically achieve comparable accuracy with 25-50% reduced circuit depth compared to fixed ansatze [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core Protocol: ADAPT-VQE for Ground States

Objective: Compute the ground-state energy of a molecular system using the gradient-informed adaptive algorithm.

Pre-experiment Requirements:

- Molecular geometry and basis set specification

- Operator pool definition (e.g., UCCSD, qubit-excitation-based)

- Quantum hardware or simulator with measurement capabilities

Procedure:

- Initialization: Prepare the reference state (typically Hartree-Fock) on the quantum processor.

- Gradient Evaluation: For each operator ( Ai ) in the pool ( \mathbb{U} ), compute the gradient ( \frac{\partial E}{\partial \thetai} \Big|{\thetai=0} ) using quantum measurements.

- Operator Selection: Identify the operator ( A^* ) with the largest gradient magnitude: ( A^* = \underset{Ai \in \mathbb{U}}{\text{argmax}} \left| \frac{\partial E}{\partial \thetai} \Big|{\thetai=0} \right| ).

- Ansatz Expansion: Append ( e^{\theta^* A^} ) to the current ansatz, initializing ( \theta^ = 0 ).

- Parameter Optimization: Optimize all parameters in the expanded ansatz using a classical optimizer (e.g., BFGS, gradient descent).

- Convergence Check: If the gradient norm falls below threshold ( \epsilon ) or energy convergence is achieved, terminate; else return to step 2.

Post-processing:

- Energy extrapolation to the complete basis set limit if necessary

- Calculation of molecular properties from the optimized wavefunction

- Error analysis accounting for measurement statistics and hardware noise

Specialized Protocol: Adaptive VQE-X for Excited States

Objective: Target highly excited states of a many-body Hamiltonian using variance-based adaptive approach.

Modifications to Core Protocol:

- Target Function: Replace energy expectation with variance ( \langle H^2 \rangle - \langle H \rangle^2 ) as the minimization objective.

- Operator Pool: Consider pools with long-range two-body operators for improved convergence in non-integrable regimes [12].

- Initialization: No specific initial state requirement, as the method is not dependent on proximity to the target state.

Validation:

- Compare obtained energy with classical methods where feasible

- Compute entanglement entropy and other state-specific properties

- Verify orthogonality to lower-energy states when targeting specific excitations

Visualization of Algorithmic Workflows

Adaptive Algorithm Selection Process

ADAPT-VQE Workflow

Multi-Algorithm Decision Pathway

Algorithm Selection Guide

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Resources for Adaptive Quantum Experiments

| Research Reagent | Function | Implementation Example | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operator Pool | Defines search space for ansatz construction | UCCSD, qubit excitation, hardware-native gates | Pool choice dramatically affects convergence and circuit efficiency [12] |

| Gradient Calculator | Measures parameter sensitivities for operator selection | Parameter-shift rule, finite-difference methods | Major source of measurement overhead; efficient strategies needed [1] |

| Classical Optimizer | Minimizes energy with respect to variational parameters | BFGS, gradient descent, CMA-ES | Choice affects convergence speed and susceptibility to local minima [10] |

| Error Mitigation | Reduces impact of hardware noise on results | Zero-noise extrapolation, dynamical decoupling | Essential for accurate results on NISQ devices [1] |

| Measurement Scheme | Estimates expectation values from quantum circuits | Pauli grouping, classical shadows | Can reduce required circuit executions by orders of magnitude [1] |

| Ataciguat | Ataciguat, CAS:254877-67-3, MF:C21H19Cl2N3O6S3, MW:576.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 7u85 Hydrochloride | 7u85 Hydrochloride, CAS:120097-92-9, MF:C22H25ClN2O2, MW:384.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The landscape of adaptive variational quantum algorithms has expanded significantly beyond the original ADAPT-VQE framework, with distinct algorithm families now targeting diverse challenges in molecular simulation. Each family—gradient-informed greedy optimizers, variance-based excited state methods, open system simulators, and lookback-based adaptive approaches—embodies unique founding principles that determine its applicability to specific research problems in molecular systems and drug development.

The experimental protocols and quantitative benchmarks presented here provide researchers with practical guidance for implementing these methods, while the visualization of algorithmic workflows offers conceptual clarity for selecting appropriate approaches. As quantum hardware continues to evolve toward the 25-100 logical qubit regime [15], these adaptive algorithms will play an increasingly crucial role in achieving quantum utility for chemically relevant problems.

Future development will likely focus on reducing measurement overhead, improving noise resilience, and developing more sophisticated operator pools tailored to specific chemical applications. The integration of these adaptive quantum algorithms with classical computational chemistry workflows promises to open new frontiers in our understanding of molecular systems and accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic agents.

The accurate simulation of molecular ground states is a cornerstone of modern chemistry, with profound implications for drug discovery and materials science. However, the exponential scaling of the Hilbert space makes exact solutions classically intractable for all but the smallest systems. The advent of quantum computing, particularly through hybrid quantum-classical algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), has revitalized pursuit of this challenge. Within this domain, adaptive variational quantum algorithms have emerged as a transformative methodology designed to overcome critical limitations of fixed-ansatz approaches on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. Unlike fixed-ansatz methods that employ predetermined quantum circuits—often containing redundant operators that needlessly increase circuit depth and susceptibility to noise—adaptive algorithms iteratively construct resource-efficient, system-tailored ansätze. This protocol focuses on the implementation and application of these advanced algorithms, specifically the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter (ADAPT)-VQE and the Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive (GGA)-VQE, for targeting molecular ground states within quantum chemistry frameworks [1].

The core challenge in NISQ-era quantum chemistry is balancing ansatz expressivity against hardware constraints. Deep, highly expressive circuits are vulnerable to decoherence and gate errors, while shallow, less expressive circuits may fail to capture complex electron correlations. Adaptive algorithms address this dichotomy by systematically building compact ansätze that are specifically tailored to the molecular system of interest, thereby minimizing redundant parameters and circuit depth. By focusing only on the most physically relevant operators, these methods aim to achieve high accuracy within the stringent coherence-time limitations of current quantum hardware, establishing a pragmatic path toward quantum advantage in molecular simulation [1] [16].

Algorithmic Foundations and Key Protocols

This section details the core mechanistic protocols of two primary adaptive algorithms and the theoretical foundation of enforcing physical constraints on noisy quantum outputs.

The ADAPT-VQE Protocol

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm iteratively grows an ansatz by selecting the most energetically favorable operator from a predefined pool at each step [1].

Step 1: Operator Selection

- Objective: Identify the most promising parameterized unitary operator

U*from a poolUto append to the current ansatz|Ψ^(m-1)>. - Criterion: The selection is based on the gradient of the energy expectation value with respect to each pool operator's parameter, evaluated at zero:

U* = argmax_{U in U} | d/dθ <Ψ^(m-1)| U†(θ) H U(θ) |Ψ^(m-1)> |_{θ=0} |[1]. - Procedure: This requires evaluating the gradient for every operator in the pool, a process that can be measurement-intensive but is crucial for the algorithm's efficiency.

- Objective: Identify the most promising parameterized unitary operator

Step 2: Global Parameter Optimization

- Objective: Variationally optimize all parameters

(θ_1, ..., θ_m)in the newly expanded ansatz|Ψ^(m)> = U*(θ_m)|Ψ^(m-1)>. - Optimization Problem:

(θ_1^(m), ..., θ_m^(m)) = argmin_{θ_1, ..., θ_m} <Ψ^(m)(θ_1, ..., θ_m)| H |Ψ^(m)(θ_1, ..., θ_m)>[1]. - Challenge: This step involves a high-dimensional, non-convex optimization problem that can be hampered by noise in the cost function evaluation on real hardware.

- Objective: Variationally optimize all parameters

The following workflow diagram illustrates the iterative procedure of the ADAPT-VQE protocol:

The GGA-VQE Protocol

To mitigate the measurement overhead and noise-sensitivity of ADAPT-VQE, the Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE) was introduced. It simplifies the optimization process, offering improved resilience on NISQ devices [1].

- Core Innovation: Replaces the gradient-based operator selection with a gradient-free, greedy strategy and employs analytic, local optimization methods.

- Key Steps:

- Greedy Operator Selection: Instead of computing gradients for the entire pool, operators are selected based on a heuristic or a direct energy-lowering potential, reducing the number of quantum measurements required.

- Analytic Local Optimization: After appending a new operator, GGA-VQE often optimizes its parameter analytically or with very few energy evaluations, before proceeding to a less frequent global optimization.

- Demonstrated Performance: This protocol has been successfully executed on a 25-qubit error-mitigated QPU to compute the ground state of a 25-body Ising model. While hardware noise produced inaccurate raw energies, the algorithm generated a parameterized circuit that, when evaluated via noiseless emulation, yielded a favorable ground-state approximation [1].

Protocol for Accurate Ground-State Properties via RDM Purification

A significant challenge on NISQ devices is that noise can render measured outputs unphysical. A supplementary protocol addresses this by classically post-processing the quantum computer's output to enforce physical constraints [16].

- Objective: Recover accurate ground-state energies and properties from noisy quantum computations by purifying measured two-electron Reduced Density Matrices (2-RDMs).

- Theoretical Basis: A valid 2-RDM must correspond to an N-electron wavefunction, a condition known as N-representability. The protocol enforces a subset of these conditions (the DQG conditions) which require the two-particle (D), two-hole (Q), and particle-hole (G) matrices to be positive semidefinite [16].

- Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Prepare a quantum state

|ψ(θ)>on the hardware and perform measurements to estimate the raw, noisy 2-RDM elements(D_pq^rs)_noisy. - Classical Purification: Project the noisy 2-RDM onto the set of N-representable 2-RDMs by solving a semidefinite program that minimizes the distance to the experimental data while enforcing the DQG positivity constraints.

- Energy Calculation: Compute the ground-state energy using the purified, physically valid 2-RDM via the standard energy expression

E = sum_{ij} h_j^i D_i^j + sum_{pqrs} V_rs^pq D_pq^rs + H_n[16].

- Data Acquisition: Prepare a quantum state

This framework has demonstrated near full configuration-interaction accuracy for small molecules like Hâ‚‚, LiH, and Hâ‚„ on noisy hardware, simultaneously overcoming both ansatz limitations and hardware noise [16].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful execution of adaptive VQE experiments relies on a suite of computational tools and datasets. The table below catalogues the key "research reagent" solutions for this field.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Adaptive Quantum Chemistry

| Tool Name/Type | Primary Function | Key Features & Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) Hardware | Execution of parameterized quantum circuits. | 25+ qubit, error-mitigated QPUs are used to run adaptive algorithms like GGA-VQE; subject to gate infidelities and decoherence [1] [16]. |

| Operator Pools | Library of unitary operators for ansatz construction. | Typically consist of fermionic excitation operators (e.g., singles and doubles); system-tailored pools improve algorithm convergence and efficiency [1]. |

| Classical Optimizer | Minimizes the energy expectation value. | Algorithms like BFGS or COBYLA are used in the global optimization loop; performance is degraded by noisy cost functions [1]. |

| Aquamarine (AQM) Dataset | Benchmark for validating methods on drug-like molecules. | Contains ~60k conformers of 1,653 molecules (up to 92 atoms), with >40 QM properties computed at PBE0+MBD level; tests ability to handle large, flexible systems [17]. |

| QM40 Dataset | Benchmark for machine-learned quantum property prediction. | Contains 16 QM properties for 162k molecules (up to 40 atoms) at B3LYP/6-31G(2df,p) level; represents 88% of FDA-approved drug chemical space [18]. |

| N-Representability Solver | Classical post-processing to enforce physical constraints on RDMs. | Uses semidefinite programming to project noisy quantum data onto the set of physical 2-RDMs; crucial for obtaining accurate energies from noisy hardware [16]. |

Experimental Validation and Performance Metrics

The evaluation of adaptive VQE protocols involves benchmarking against classical simulations and assessing robustness under realistic noise conditions. The quantitative performance of these algorithms is summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Performance Summary of Adaptive Quantum Algorithms

| Algorithm / Protocol | Test System | Key Performance Metrics | Limitations & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADAPT-VQE (Noiseless Simulation) | Hâ‚‚O, LiH molecules | Recovers exact ground state energy to high accuracy [1]. | Performance is highly idealistic; not representative of hardware conditions. |

| ADAPT-VQE (Noisy Simulation) | Hâ‚‚O, LiH molecules | Stagnates well above chemical accuracy (1 mHa) with 10,000 shots per measurement [1]. | High measurement overhead; optimization hampered by noisy cost function. |

| GGA-VQE (On 25-qubit QPU) | 25-body Ising Model | Outputs a circuit yielding a favorable ground-state approximation upon noiseless emulation [1]. | Raw hardware energies are inaccurate due to noise. |

| RDM Purification Framework | Hâ‚‚, LiH, Hâ‚„ molecules | Achieves near full CI accuracy for ground-state energies on noisy hardware [16]. | --- |

| RDM Purification Framework | C₆H₈ (UED intensities) | Reproduces Ultrafast Electron Diffraction intensities with high fidelity [16]. | Demonstrates extension beyond ground-state energies to other properties. |

The workflow for a typical experimental cycle, integrating both quantum and classical processing, is depicted in the following diagram:

Adaptive variational quantum algorithms represent a sophisticated and pragmatic framework for tackling the molecular ground-state problem on current and near-term quantum hardware. By moving beyond fixed-ansatz approaches, protocols like ADAPT-VQE and GGA-VQE systematically construct resource-efficient quantum circuits that are specifically tailored to the electronic structure of the target molecule. When combined with advanced error-mitigation and post-processing techniques—such as RDM purification—these algorithms form a powerful toolkit that simultaneously addresses the dual challenges of limited ansatz expressivity and pervasive hardware noise.

The experimental protocols outlined herein, supported by benchmark datasets like AQM and QM40, provide a clear roadmap for researchers aiming to demonstrate quantum utility in chemistry. The successful calculation of ground-state energies for small molecules and the accurate reproduction of experimental observables like UED intensities mark critical steps toward this goal. Future development will focus on further reducing quantum resource requirements, improving noise resilience, and scaling these methods to larger, more pharmacologically relevant molecules, ultimately solidifying the role of quantum computation in accelerating drug discovery and materials design.

Implementing Adaptive Algorithms: From Greedy Strategies to Open System Dynamics

The Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive Variational Quantum Eigensolver (GGA-VQE) represents a significant advancement in hybrid quantum-classical algorithms, specifically engineered for the challenges of Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) computing. By introducing a greedy, gradient-free operator selection mechanism, GGA-VQE addresses the critical limitations of measurement overhead and noise sensitivity that have hindered the practical implementation of adaptive VQE protocols like ADAPT-VQE on real hardware [1] [19]. This protocol details the application of GGA-VQE for molecular system research, providing a framework for researchers to obtain reliable ground-state energy approximations—a cornerstone for computational chemistry and drug discovery endeavors such as binding affinity prediction and reaction profile calculation [20] [21].

Identifying molecular ground states is essential for predicting chemical properties and reaction dynamics, a task fundamentally limited by exponential scaling on classical computers [21]. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) leverages quantum processors to prepare and measure parameterized trial wavefunctions (ansätze), using classical optimizers to minimize the energy expectation value [1]. While VQE is a leading algorithm for the NISQ era, its standard "fixed-ansatz" implementations often yield inaccurate results for complex molecular systems due to their system-agnostic nature and high susceptibility to noise [1] [22].

Adaptive VQE variants, most notably the ADAPT-VQE algorithm, were conceived to build system-tailored ansätze iteratively. While ADAPT-VQE demonstrates improved accuracy and circuit compactness, its practical execution is hampered by two primary factors [1] [23]:

- Operator Selection Overhead: The process of selecting the next operator to append to the ansatz requires computing the gradient of the energy expectation value for every operator in a predefined pool, a process demanding tens of thousands of noisy quantum measurements [1].

- Costly Global Optimization: After each new operator is added, a global optimization over all previous parameters is necessary, leading to a high-dimensional, noisy optimization landscape that is often intractable [1].

Simulations demonstrate that under realistic shot noise (e.g., 10,000 shots), ADAPT-VQE performance stagnates well above chemical accuracy for simple molecules like Hâ‚‚O and LiH [1]. The GGA-VQE algorithm introduces a streamlined, resource-efficient approach to overcome these bottlenecks, enabling the first fully converged computation of a 25-body problem on a real 25-qubit quantum processing unit (QPU) [19] [23].

The GGA-VQE Algorithm: Core Principles and Workflow

The foundational innovation of GGA-VQE lies in its simplification of the adaptive ansatz-building loop. It replaces the separate gradient-based operator selection and global optimization steps of ADAPT-VQE with a single, greedy step that simultaneously selects the best operator and its optimal parameter [19] [23].

Table 1: Core Conceptual Differences Between ADAPT-VQE and GGA-VQE

| Feature | ADAPT-VQE | GGA-VQE |

|---|---|---|

| Selection Criterion | Maximum gradient magnitude [1] | Minimum achievable energy from fitted curve [19] |

| Parameter Optimization | Global optimization of all parameters after each step [1] | Local, one-time optimization of the new parameter only [23] |

| Measurements per Iteration | Polynomially scales with number of operators and parameters [1] | Fixed, small number (e.g., 2-5), independent of problem size [19] [23] |

| Noise Resilience | Low; suffers severe accuracy loss under shot noise [1] | High; maintains accuracy in noisy simulations and on hardware [19] [24] |

| Hardware Implementation | Not achieved on real devices [1] | Demonstrated on a 25-qubit trapped-ion QPU [19] |

The GGA-VQE Protocol

The algorithm proceeds iteratively, building an ansatz circuit one gate at a time. The workflow for a single iteration is as follows:

Step 1: Sampling Candidate Operators

For each parameterized unitary operator U_i(θ) in a predefined pool (e.g., fermionic excitation operators or hardware-native gates), the algorithm prepares the circuit U_i(θ) |Ψâ½áµâ»Â¹â¾âŸ©, where |Ψâ½áµâ»Â¹â¾âŸ© is the current ansatz state from the previous iteration [19].

Step 2: Curve Fitting for Energy Estimation

The key insight is that the energy expectation value E_i(θ) = ⟨Ψâ½áµâ»Â¹â¾| U_i†(θ) H U_i(θ) |Ψâ½áµâ»Â¹â¾âŸ© is a simple sinusoidal function of the parameter θ [23]. For each candidate, the energy is measured at only 2 to 5 strategically chosen values of θ. These few data points are sufficient to fit the function E_i(θ) = A cos(θ) + B sin(θ) + C, fully characterizing the energy landscape for that operator [19] [24].

Step 3: Analytical Minimum Identification

Using the fitted parameters (A, B, C), the angle θ_min that minimizes E_i(θ) is found analytically. This avoids any iterative optimization for this parameter [23].

Step 4: Greedy Operator Selection

The algorithm now has a pair (U_i, θ_min) for every candidate operator in the pool. It selects the operator that yields the lowest energy value E_i(θ_min) [19]. This is the "greedy" step, as it chooses the operator providing the largest immediate energy reduction.

Step 5: Ansatz Update and Parameter Fixing

The selected unitary operator U^*(θ_min) is appended to the ansatz circuit. Crucially, the parameter θ_min is fixed permanently and is not revisited in subsequent iterations [23]. This eliminates the need for the global re-optimization that plagues ADAPT-VQE.

The algorithm iterates until a convergence criterion is met, such as a minimal energy change between iterations or the exhaustion of a maximum number of operators.

Experimental Validation and Performance Metrics

The performance and noise resilience of GGA-VQE have been validated through both numerical simulations of molecular systems and a landmark demonstration on a 25-qubit trapped-ion quantum computer (IonQ's Aria system via Amazon Braket) [19] [25].

Resilience to Statistical Noise in Molecular Simulations

In simulations of small molecules like Hâ‚‚O and LiH under realistic shot noise (10,000 shots), GGA-VQE significantly outperforms ADAPT-VQE.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Under Shot Noise (10,000 shots)

| Molecule | Algorithm | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚O | ADAPT-VQE | Stagnates well above chemical accuracy [1] |

| Hâ‚‚O | GGA-VQE | ~2x more accurate than ADAPT-VQE after ~30 iterations [19] |

| LiH | ADAPT-VQE | Stagnates well above chemical accuracy [1] |

| LiH | GGA-VQE | ~5x more accurate than ADAPT-VQE under the same conditions [19] |

Hardware Demonstration: 25-Qubit Ising Model

The most compelling validation was the successful execution of GGA-VQE on a real 25-qubit QPU to compute the ground state of a 25-body transverse-field Ising model [19]. The experimental protocol and outcomes are summarized below.

Table 3: GGA-VQE Hardware Demonstration Protocol and Results

| Experimental Component | Implementation Details |

|---|---|

| Problem | 25-body Transverse-Field Ising Model Ground State [19] |

| Hardware | 25-qubit trapped-ion QPU (IonQ Aria) [19] |

| Measurements/Iteration | 5 [19] [23] |

| Result Fidelity | >98% compared to true ground state [19] [24] |

| Key Insight | The parameterized circuit (ansatz) built on the noisy QPU, when evaluated via noiseless classical emulation, yielded a favorable ground-state approximation. This "hybrid observable measurement" strategy validates that GGA-VQE constructs a high-quality solution blueprint, even with noisy energy evaluations [1] [19]. |

Application in Drug Discovery: A Practical Pipeline

Quantum computing holds the potential to revolutionize drug discovery by providing more accurate simulations of molecular interactions, which are fundamentally quantum mechanical [21]. GGA-VQE can be integrated into a hybrid quantum-classical pipeline for specific, computationally intensive tasks.

Protocol: Calculating Gibbs Free Energy Profiles for Prodrug Activation

A critical application in drug design is simulating the activation of prodrugs, which involves calculating the energy barrier for covalent bond cleavage (e.g., Carbon-Carbon bond cleavage in β-lapachone prodrugs) [20]. The following protocol outlines how GGA-VQE can be applied to this problem:

System Preparation:

- Select the molecular system along the reaction coordinate of the covalent bond cleavage.

- Employ active space approximation to reduce the full electronic structure problem to a manageable number of electrons and orbitals (e.g., a 2-electron/2-orbital system) for quantum computation [20].

- Classically optimize the molecular geometry at each point along the reaction path.

Qubit Hamiltonian Generation:

- Generate the electronic Hamiltonian within the selected active space and basis set (e.g., 6-311G(d,p)) using a classical computer.

- Transform the fermionic Hamiltonian into a qubit Hamiltonian via a parity transformation [20].

Solvation Model Integration:

- Integrate a solvation model, such as the ddCOSMO polarizable continuum model (PCM), to simulate the physiological aqueous environment. This involves calculating solvent-solute interaction terms that are incorporated into the quantum computation [20].

GGA-VQE Execution:

- For each molecular configuration along the reaction path, use GGA-VQE on a quantum device (or emulator) to compute the ground state energy. A hardware-efficient

R_yansatz with a single layer can be used as the parameterized circuit [20]. - Apply readout error mitigation techniques during the quantum measurement phase.

- For each molecular configuration along the reaction path, use GGA-VQE on a quantum device (or emulator) to compute the ground state energy. A hardware-efficient

Thermodynamic Correction and Profile Construction:

- Calculate thermal and Gibbs free energy corrections at the Hartree-Fock (HF) level classically [20].

- Combine the GGA-VQE electronic energies with the thermal corrections to construct the final Gibbs free energy profile and determine the reaction energy barrier.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key computational "reagents" required for implementing GGA-VQE in molecular simulations.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for GGA-VQE Molecular Simulation

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Specification |

|---|---|

| Operator Pool | A predefined set of parameterized unitary gates (e.g., fermionic single and double excitation operators for molecular Hamiltonians) from which the ansatz is built [1]. |

| Active Space | A selection of chemically relevant molecular orbitals and electrons, reducing the computational burden (e.g., 2 electrons in 2 orbitals) while retaining essential physics [20]. |

| Basis Set | A set of basis functions (e.g., 6-311G(d,p)) used to represent molecular orbitals in quantum chemistry calculations [20]. |

| Solvation Model | A computational model (e.g., ddCOSMO) that approximates the effect of a solvent environment on the quantum mechanical calculation [20]. |

| Error Mitigation | Software techniques (e.g., readout error mitigation) applied to raw quantum device results to improve accuracy without requiring additional qubits [20]. |

| Classical Emulator | A high-performance computing (HPC) resource used for noiseless validation of the quantum-built ansatz via "hybrid observable measurement" [1] [19]. |

| A-123189 | A-123189, MF:C26H28N4O3S, MW:476.6 g/mol |

| Azido-PEG10-alcohol | Azido-PEG10-alcohol, MF:C20H41N3O10, MW:483.6 g/mol |

GGA-VQE establishes a new, practical paradigm for adaptive variational quantum algorithms on NISQ devices. Its greedy, gradient-free protocol directly confronts the dual challenges of measurement overhead and noise susceptibility, enabling meaningful quantum computations for molecular systems today. By providing a viable path to accurate ground-state energy calculations, GGA-VQE serves as a critical tool for researchers in quantum chemistry and drug development, potentially accelerating the discovery of new therapeutics and materials by providing insights that are classically intractable. Its successful hardware demonstration marks a significant step from theoretical algorithm design toward applied quantum computational science.

Algorithmic Frameworks for Simulating Open Quantum System Dynamics in Molecular Environments

The accurate simulation of open quantum system dynamics in molecular environments represents a significant challenge in quantum chemistry, with profound implications for drug discovery, materials science, and the development of renewable energy technologies. These dynamics are fundamental to understanding photochemical reactions, energy transfer processes, and decoherence mechanisms in complex molecular systems. The inherent complexity of simulating these non-equilibrium processes arises from the need to model quantum systems coupled to extensive environmental degrees of freedom, a task that typically exceeds the practical capabilities of even the most advanced classical computational methods.

Recent advancements in hybrid quantum-classical algorithmic frameworks are creating new pathways to overcome these challenges. Adaptive variational quantum algorithms have emerged as particularly promising candidates for exploiting the capabilities of noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) processors while mitigating their limitations [1]. These algorithms systematically construct problem-specific ansätze through iterative processes, offering a pathway to simulate complex molecular dynamics with resource efficiency that can be several orders of magnitude greater than conventional quantum computing approaches [26].

This document provides application notes and detailed experimental protocols for implementing these algorithmic frameworks, with a specific focus on their application to molecular systems research. By integrating quantitative performance data, structured methodologies, and visualization tools, we aim to equip researchers with practical resources to advance the simulation of open quantum dynamics in photochemistry, photobiology, and related fields.

Key Algorithmic Frameworks and Performance Benchmarks

Adaptive variational quantum algorithms represent a class of hybrid quantum-classical methods that dynamically construct ansatz wavefunctions tailored to specific molecular systems. Unlike fixed-ansatz approaches, these methods employ system-driven, iterative protocols to build quantum circuits that contain minimal redundancy, thereby reducing circuit depth and parameter counts—critical advantages for implementation on NISQ devices [1].

The core innovation of these frameworks lies in their greedy, gradient-free optimization strategies, which enhance resilience to statistical sampling noise—a pervasive challenge in quantum processing units (QPUs) [1]. By circumventing the need for high-dimensional cost function optimization and computationally expensive gradient calculations, these algorithms significantly reduce the quantum measurement overhead required for practical implementation.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of prominent adaptive variational algorithms and recent experimental demonstrations for molecular simulations.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of Quantum Algorithms for Molecular Simulations

| Algorithm / Protocol | Key Innovation | Resource Requirements | Reported Performance / Accuracy | Experimental Platform |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGA-VQE [1] | Greedy, gradient-free adaptive ansatz construction | Reduced quantum measurement overhead; improved noise resilience | Overcomes stagnation above chemical accuracy (1 mHa) seen in noisy ADAPT-VQE | Noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) computer emulation |

| Resource-Efficient Chemical Dynamics Simulation [26] | Analog quantum simulation with novel encoding | Single trapped ion (≈1 million times more resource-efficient than conventional approaches) | Simulates ultrafast (femtosecond) dynamics with 100-billion-fold time dilation | Trapped-ion quantum computer |

| ADAPT-VQE (Noiseless) [1] | Gradient-based operator selection from predefined pool | Requires computation of Hamiltonian gradients for all pool operators | Recovers exact ground state energy to high accuracy for Hâ‚‚O and LiH | Noiseless simulation |

| ADAPT-VQE (Noisy) [1] | Same as noiseless version, but with statistical noise | 10,000 shots per measurement on HPC emulator | Stagnates well above chemical accuracy threshold | High-performance computing (HPC) emulator with simulated shot noise |

Experimental Workflow for GGA-VQE

The following diagram illustrates the iterative workflow of the Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive Variational Quantum Eigensolver (GGA-VQE), highlighting its cyclic process of operator selection and parameter optimization.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing GGA-VQE for Molecular Ground States

This protocol details the implementation of the Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE for calculating molecular ground-state energies, a foundational step for subsequent dynamics simulations.

Materials and Prerequisites

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for GGA-VQE Implementation

| Component | Specification / Function | Implementation Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Processing Unit (QPU) | NISQ-era quantum processor (superconducting or trapped ion) or high-performance emulator | Provides the quantum computational substrate for ansatz evaluation [1]. | |

| Classical Optimizer | Gradient-free global optimization algorithm (e.g., COBYLA, Nelder-Mead) | Executes on classical hardware to iteratively adjust variational parameters [1]. | |

| Operator Pool (ð•Œ) | Set of parameterized unitary operators (e.g., fermionic excitation operators UCCSD-style pool) | Forms the building blocks for the adaptive ansatz; should be chemically inspired [1]. | |

| Initial Reference State | Typically Hartree-Fock (HF) state | Ψâ½â°â¾âŸ©; serves as the starting point for the adaptive ansatz construction [1]. | |

| Hamiltonian (Â) | Molecular electronic Hamiltonian mapped to qubits (e.g., via Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation) | The Hermitian operator whose ground state is being prepared [1]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Initialization:

- Prepare the initial reference state |Ψâ½â°â¾âŸ© = |HF⟩ on the QPU.

- Define the molecular Hamiltonian  and pre-select an operator pool ð•Œ.

- Set the convergence threshold (e.g., 1.0 mHa for chemical accuracy) and a maximum number of iterations.

Iterative Ansatz Construction Loop (for iteration m = 1, 2, ...):

- Operator Selection: For each operator ð’° in the pool ð•Œ, compute the selection metric. GGA-VQE uses a gradient-free metric to identify the operator that, when applied, yields the greatest potential energy improvement [1].

- Ansatz Update: Append the selected operator ð’°* to the current ansatz to form a new parameterized state: |Ψâ½áµâ¾(θₘ, ...)⟩ = ð’°*(θₘ)|Ψâ½áµâ»Â¹â¾âŸ©. This introduces one new variational parameter θₘ.

- Parameter Optimization: Execute a global optimization over all parameters {θâ‚, ..., θₘ} of the new, longer ansatz to minimize the energy expectation value ⟨Ψâ½áµâ¾|Â|Ψâ½áµâ¾âŸ©. This step involves repeated evaluation of the expectation value on the QPU.

- Convergence Check: If the energy change from the previous iteration is below the threshold, exit the loop and proceed to the final output. Otherwise, proceed to the next iteration.

Final Output:

- The algorithm outputs the final optimized parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) and the corresponding approximation of the ground state energy E_gs.

Protocol 2: Quantum Simulation of Chemical Dynamics

This protocol is based on the resource-efficient method demonstrated by the University of Sydney team for simulating ultrafast chemical dynamics on a trapped-ion quantum computer [26].

Materials and Prerequisites

- Quantum Simulator: An analog quantum simulator, such as a single trapped ion, capable of natively encoding the molecular Hamiltonian dynamics [26].

- Molecular System: Specification of the target molecule (e.g., allene C₃H₄, butatriene C₄H₄, or pyrazine C₄N₂H₄) and its photoexcited electronic and vibrational states.

- Dynamical Model: A model Hamiltonian (e.g., a model involving coupled electronic and vibrational degrees of freedom) describing the ultrafast non-adiabatic dynamics after photoexcitation.

Step-by-Step Procedure

System Encoding:

- Map the relevant electronic and vibrational states of the molecule onto the internal and motional states of the trapped ion using a highly efficient, problem-specific encoding scheme. This step is crucial for achieving massive resource reduction [26].

Hamiltonian Engineering:

- Apply precisely controlled laser pulses to the ion to engineer an effective Hamiltonian Ĥ_sim that reproduces the dynamics of the target molecular system. This makes the trapped ion's evolution analogous to the molecular dynamics of interest.

Dynamics Simulation:

- Initialize the quantum simulator in a state corresponding to the molecule's post-photoexcitation state.

- Allow the system to evolve under the engineered Hamiltonian Ĥ_sim for a controllable laboratory time t. Due to the engineered energy scales, this laboratory time corresponds to a much shorter femtosecond-scale dynamical process in the molecule, achieving a massive time-dilation factor (e.g., 10¹¹) [26].

Measurement and Readout:

- At various time points t, measure the state of the quantum simulator (e.g., through state-dependent fluorescence of the ion).

- The measurement outcomes correspond to the populations of different electronic and vibrational states in the molecule at the simulated time, allowing the reconstruction of the dynamical trajectory.

The workflow for this analog simulation protocol is more direct than the iterative VQE process and is captured in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs the essential "research reagents"—the core algorithmic and hardware components—required for effective simulation of open quantum system dynamics in molecular environments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Simulation of Molecular Dynamics

| Toolkit Component | Category | Function & Relevance | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive VQE Algorithms | Algorithmic Framework | Constructs system-tailored, compact ansätze to minimize circuit depth and combat noise on NISQ devices. | GGA-VQE [1], ADAPT-VQE [1] |

| Resource-Efficient Encoding | Encoding Strategy | Maps molecular problems to quantum hardware with minimal qubit and gate overhead, enabling complex simulations. | Novel encoding for chemical dynamics [26] |

| Noise-Adaptive Quantum Algorithms (NAQAs) | Algorithmic Framework | Exploits, rather than suppresses, noise by aggregating information from multiple noisy outputs to steer optimization. | Contrasts with ADAPT methods [27] |

| Trapped-Ion QPU / Simulator | Hardware Platform | Provides a high-fidelity, analog simulation environment with long coherence times, suitable for dynamical studies. | Used for first quantum simulation of real molecular chemical dynamics [26] |

| NISQ QPU (Superconducting) | Hardware Platform | Provides a digital gate-based platform for running variational algorithms like VQE and testing error correction. | Used for implementing color codes and running adaptive VQEs [1] [28] |

| Gradient-Free Classical Optimizer | Software Component | Optimizes variational parameters in VQEs without requiring numerically unstable or expensive gradient calculations. | Critical for GGA-VQE performance [1] |

| Error Correction/Mitigation | Hardware/Software | Suppresses physical errors to extend coherent computation, either via QEC codes or post-processing mitigation. | Color codes [28] [29], error mitigation techniques |

| Azimsulfuron | Azimsulfuron, CAS:120162-55-2, MF:C13H16N10O5S, MW:424.40 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Abanoquil | Abanoquil, CAS:90402-40-7, MF:C22H25N3O4, MW:395.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Adaptive Variational Quantum Eigensolvers (ADAPT-VQEs) have emerged as promising algorithms for molecular simulation on near-term quantum devices, dynamically constructing ansätze by iteratively appending parametrized unitary operators, or "generators," from a predefined pool [30] [1]. The central challenge in these algorithms lies in the generator selection step, which aims to identify the most effective operator to include at each iteration to rapidly converge toward the ground state. This process is typically guided by the magnitude of the energy gradient with respect to each candidate generator [30]. However, estimating these gradients requires a large number of quantum measurements, creating a significant bottleneck that scales steeply with system size, potentially as high as ð’ª(Nâ¸) for molecules with N spin-orbitals [30]. Furthermore, a fundamental trade-off exists: highly expressive ansätze, necessary for simulating complex molecular systems, often require more costly gradient measurement procedures [31]. These methodologies must therefore strategically balance the competing demands of computational efficiency and ansatz expressibility to be practical for real-world applications such as drug development.

Core Principles and Trade-offs

The Generator Selection Problem

In adaptive variational algorithms, the quantum state at iteration k is given by |ψₖ⟩ = âˆáµ¢â‚Œâ‚áµ e^{θᵢ GÌ‚áµ¢}|ψ₀⟩, where GÌ‚áµ¢ are the selected generators and |ψ₀⟩ is the initial reference state (e.g., Hartree-Fock) [30]. The key task at each step is to identify the generator GÌ‚M from a pool 𒜠that will most effectively lower the energy, commonly achieved by selecting the one with the largest energy gradient magnitude [30]: [ gi = \langle \psik | [\hat{H}, \hat{G}i] | \psik \rangle ] The computational cost arises because evaluating *gi* for each candidate generator requires decomposing the commutator into measurable fragments and estimating their expectation values through repeated quantum measurements [30].

The Expressibility-Measurement Cost Trade-off

A fundamental trade-off governs the relationship between the expressibility of a Quantum Neural Network (QNN) and the efficiency with which its gradients can be measured [31]. Expressibility, quantified by the dimension of the Dynamical Lie Algebra (DLA) ð”¤, determines which unitaries the QNN can represent [31]. Gradient measurement efficiency ℱeff is defined as the mean number of simultaneously measurable components in the gradient [31]. As expressibility ð’³exp = dim(ð”¤) increases, the gradient measurement efficiency ℱ_eff generally decreases, meaning more measurement rounds are required per parameter [31]. This occurs because higher expressibility typically reduces commutativity between gradient operators, reducing the number that can be measured simultaneously [31]. This trade-off implies that tailoring ansatz expressivity to specific molecular systems can optimize measurement resources, whereas overly expressive ansätze waste resources, and insufficiently expressive ansätze fail to capture relevant physics [31].

Quantitative Comparison of Generator Selection Methods

The table below summarizes key generator selection methodologies, their core approaches, and resource requirements.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Generator Selection Methods

| Method | Core Approach | Key Metric | Measurement Cost | Expressibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Gradient | Evaluates all pool gradients to fixed precision [30] | Gradient magnitude | ð’ª(Pool Size); High [30] | Unconstrained; High |

| Successive Elimination (SE) | Adaptively eliminates suboptimal candidates [30] | Gradient with confidence interval | 2-10x reduction vs. standard [30] | Unconstrained; High |

| Greedy Gradient-free (GGA) | Uses energy reduction from unitary application [1] | Direct energy change | Reduced sensitivity to shot noise [1] | Maintained |

| Stabilizer-Logical Product (SLPA) | Exploits symmetric circuit structure [31] | Commutation relations | Optimal ℱeff for given ð’³exp [31] | Tailored to symmetry |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Successive Elimination (SE) for Generator Selection

The SE algorithm reformulates generator selection as a Best-Arm Identification (BAI) problem, aiming to identify the generator with the largest true gradient using minimal measurements by adaptively allocating resources and discarding unpromising candidates early [30].

Experimental Protocol:

- Initialization: Begin with the state |ψₖ⟩ from the last VQE optimization and set the active candidate set A₀ = 𒜠(the full operator pool) [30].

- Adaptive Measurement Rounds: For each round r: a. Precision Setting: Set measurement precision for the round to εr = cr ⋅ ε, where cr ≥ 1 and ε is the final target precision [30]. b. Gradient Estimation: For each generator Ĝi in the active set Ar, estimate |gi| by measuring its commutator fragments to precision εr [30]. c. Candidate Elimination: Calculate the maximum gradient magnitude in the active set, M = maxi |gi|. Eliminate all generators Ĝi satisfying [30]: [ |gi| + Rr < M - Rr ] where Rr = dr ⋅ εr is a confidence interval. This eliminates candidates whose upper confidence bound falls below the lower confidence bound of the current best candidate.

- Termination: Repeat until one candidate remains or a maximum round count L is reached. In the final round (r = L), set c_L = 1 to ensure the selected gradient is estimated to the target accuracy ε [30].

Diagram 1: Successive Elimination Workflow

Gradient Estimation via Fragmentation and Sampling

Protocol for Gradient Estimation: