Advanced Measurement Strategies to Reduce Sampling Noise in VQE for Quantum Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on mitigating finite-shot sampling noise in the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE).

Advanced Measurement Strategies to Reduce Sampling Noise in VQE for Quantum Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on mitigating finite-shot sampling noise in the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE). Covering foundational concepts to advanced applications, we detail how sampling noise distorts cost landscapes, creates false minima, and induces statistical bias, hindering reliable molecular energy calculations. We explore a suite of mitigation strategies, including Hamiltonian measurement optimization, classical optimizer selection, and error-mitigation techniques like Zero-Noise Extrapolation. The content benchmarks these methods on quantum chemistry models, offering validated, practical guidance for achieving the measurement precision required for high-stakes applications in biomedical research and clinical development.

Understanding the Sampling Noise Problem in VQE: Sources, Impacts, and Challenges for Quantum Chemistry

Defining Finite-Shot Sampling Noise and Its Role in the NISQ Era

Finite-shot sampling noise is a fundamental source of error in quantum computing that arises from the statistical uncertainty in estimating expectation values through a finite number of repetitive quantum measurements, known as "shots." In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, this noise presents a critical bottleneck for the practical application of variational quantum algorithms such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE). Unlike errors from decoherence or gate infidelities, sampling noise is intrinsic to the measurement process itself; even on perfectly error-free quantum devices, estimating an expectation value ⟨Ψ|H|Ψ⟩ from a finite number of circuit executions will yield a statistical distribution rather than a deterministic value [1] [2].

The standard deviation of this statistical distribution defines the magnitude of finite-shot sampling noise. For an expectation value calculated from N-shots, the standard error scales as O(1/√N)

[1]. This inverse square root relationship makes it prohibitively expensive to simply "measure our way out" of the problem: reducing the error by a factor of 10 requires a 100-fold increase in measurement shots. With current quantum hardware often limiting shot counts and charging per-shot on cloud platforms, this creates a fundamental constraint on the precision achievable in near-term quantum applications, particularly in resource-intensive fields like quantum chemistry where high-precision energy estimation is essential [1] [3].

Quantitative Characterization of Sampling Noise

Fundamental Mathematical Description

The core mathematical relationship defining finite-shot sampling noise for quantum expectation values is expressed as:

std(E[Ĥ]) = √(var(E[Ĥ]) / N_shots) [1]

where:

std(E[Ĥ])represents the standard deviation (sampling noise) of the estimated expectation valuevar(E[Ĥ])denotes the intrinsic variance of the quantum observable Ĥ in the state |Ψ⟩N_shotsis the number of measurement repetitions

For quantum neural networks (QNNs) and other variational algorithms, this noise fundamentally limits the precision with which cost functions and their gradients can be evaluated, directly impacting optimization performance and convergence [1] [2].

Comparative Impact Across Quantum Algorithms

Table 1: Characterization of Sampling Noise Across Quantum Algorithm Types

| Algorithm | Key Sampling Noise Challenges | Typical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| VQE [4] [5] | Measurement of numerous non-commuting Pauli terms in molecular Hamiltonians | High measurement budget; optimization stagnation |

| QNNs [1] [2] | Finite-shot estimation of model outputs and gradients during training | Reduced convergence speed; increased output noise |

| QKSD [6] | Ill-conditioned generalized eigenvalue problems sensitive to matrix perturbations | Significant distortion of approximated eigenvalues |

The impact of sampling noise varies considerably across different algorithmic frameworks. In VQE for quantum chemistry, molecular Hamiltonians decomposed into Pauli strings require measuring hundreds to thousands of non-commuting terms, with each term subject to individual sampling noise [4] [7]. For Quantum Krylov Subspace Diagonalization (QKSD), the algorithm solves an ill-conditioned generalized eigenvalue problem where perturbations from sampling noise can dramatically distort the computed eigenvalues [6]. In Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs), sampling noise affects both the forward pass evaluation and gradient calculations during training, potentially leading to slow convergence or convergence to suboptimal parameters [1] [2].

Experimental Protocols for Sampling Noise Mitigation

Variance Regularization in Quantum Neural Networks

Variance regularization introduces a specialized loss function that simultaneously minimizes both the target error and the output variance of quantum models [1] [2].

Protocol Steps:

- Circuit Design: Implement a parameterized quantum circuit (PQC)

U(x,φ)that encodes input dataxand parametersφto generate quantum state|Ψ(x,φ)⟩ - Observable Selection: Define cost operator

Ĉ(ϕ)whose expectation valuef_{φ,ϕ}(x) = ⟨Ψ(x,φ)|Ĉ(ϕ)|Ψ(x,φ)⟩produces the QNN output - Regularized Loss Function: Construct loss function

L_total = L_task + λ⋅var(E[Ĥ])where:L_taskis the primary task-specific loss (e.g., mean squared error for regression)var(E[Ĥ])is the variance of the expectation valueλis a hyperparameter controlling regularization strength

- Optimization: Employ gradient-based or gradient-free optimization techniques to minimize

L_total - Validation: Evaluate both task performance and output variance on test datasets

Key Implementation Note: With proper circuit construction, the variance term can be calculated without additional circuit evaluations, making this approach resource-efficient for NISQ devices [1] [2].

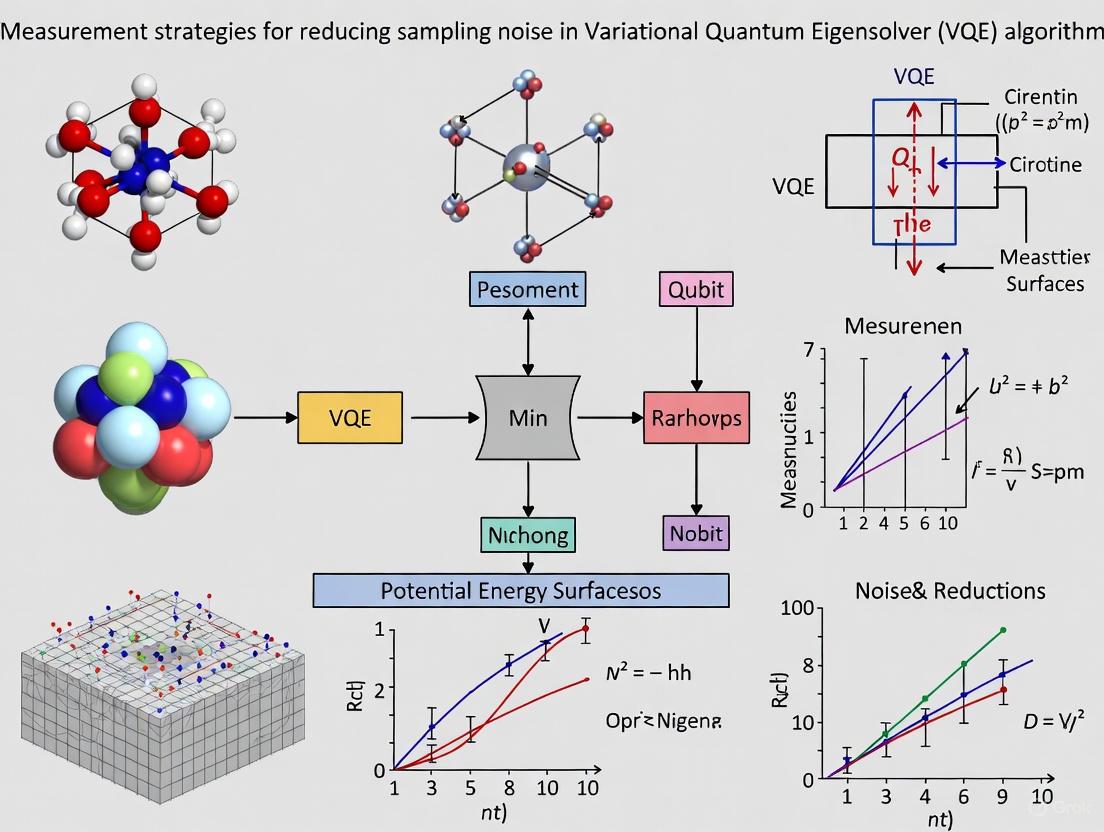

Figure 1: Variance Regularization Workflow for Quantum Neural Networks

Advanced Measurement Strategies for Quantum Chemistry

Efficient Hamiltonian term measurement addresses the challenge of evaluating molecular Hamiltonians containing hundreds to thousands of Pauli terms [6] [3].

Protocol Steps:

- Hamiltonian Decomposition: Express molecular Hamiltonian as

H = Σc_iP_iwhereP_iare Pauli strings - Term Grouping: Employ commutativity-based grouping (Pauli terms that commute can be measured simultaneously) or overlapping grouping techniques to minimize total measurement bases

- Shot Allocation Optimization: Implement optimal shot allocation across groups using weighted strategies based on term coefficients

|c_i|or estimated variances - Readout Error Mitigation: Integrate quantum detector tomography (QDT) to characterize and correct readout errors [3]

- Classical Shadows (Optional): For simultaneous estimation of multiple observables, consider locally-biased classical shadows to reduce shot overhead [3]

Validation Metrics: Track absolute error |E_est - E_ref| against reference energies and standard error σ/√N to distinguish systematic from statistical errors [3].

Hardware-Aware Optimization Strategies

Gradient-free optimization combined with noise-aware circuit design provides practical pathways for NISQ implementations [8] [5].

Protocol Steps:

- Circuit Architecture Selection: Design hardware-efficient ansatze with reference to mathematical structures like matrix product states (MPS) for shallow-depth circuits [4]

- Parameter Pre-training: Classically optimize initial circuit parameters using MPS simulations or other classical approximations to avoid poor initializations [4]

- Optimizer Selection: Implement genetic algorithms or other gradient-free optimizers that demonstrate superior performance in noisy environments compared to gradient-based methods [8]

- Error Mitigation Integration: Apply zero-noise extrapolation (ZNE) with neural network-enhanced fitting to extrapolate to the zero-noise limit [4]

- Iterative Refinement: For adaptive VQE approaches, use greedy selection with reduced measurement requirements for operator pool evaluation [5]

Table 2: Key Experimental Resources for Sampling Noise Research

| Resource / Technique | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Variance Regularization [1] [2] | Reduces output variance of expectation values as regularization term | QNN training; Variational quantum algorithms |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) [3] | Characterizes and mitigates readout errors via detector calibration | High-precision energy estimation; Readout error correction |

| Locally Biased Classical Shadows [3] | Reduces shot overhead through importance sampling of measurement bases | Multi-observable estimation; Quantum chemistry |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) [4] | Mitigates hardware noise by extrapolating from intentionally noise-amplified circuits | NISQ algorithm implementations; Error mitigation |

| Genetic Algorithms [8] | Gradient-free optimization resilient to noisy cost function evaluations | Parameter optimization on real quantum hardware |

| Matrix Product State (MPS) Pre-training [4] | Provides noise-resistant initial parameters for quantum circuits | VQE initialization; Circuit parameter optimization |

Figure 2: Sampling Noise Mitigation Strategy Taxonomy

Finite-shot sampling noise represents a fundamental challenge in the NISQ era that cannot be addressed simply by increasing measurement counts due to practical constraints on current quantum hardware. Through strategic approaches including variance regularization, advanced measurement protocols, and hardware-aware optimization, researchers can significantly reduce the impact of sampling noise on variational quantum algorithms. For VQE applications in quantum chemistry and beyond, these techniques enable more accurate energy estimation, improved convergence behavior, and more efficient resource utilization. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, the development of sampling noise mitigation strategies will remain essential for bridging the gap between theoretical potential and practical implementation of quantum algorithms in real-world applications.

Within the framework of research on measurement strategies for reducing sampling noise in the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), a significant challenge emerges from the fundamental distortion of the variational energy landscape. In practical implementations, the expectation value of the Hamiltonian, ⟨H⟩, cannot be measured exactly due to finite computational resources. Instead, it is estimated using a limited number of measurement shots (Nshots), resulting in an estimator, ⟨H⟩est, that includes a stochastic error, ϵsampling [9]. This sampling noise has profound and detrimental consequences: it distorts the topology of the cost landscape, creates illusory false variational minima, and induces a statistical bias known as the 'winner's curse', where the best observed energy value is systematically biased below its true expectation value [10] [11]. This phenomenon misleads classical optimizers, causing premature convergence and preventing the discovery of genuinely optimal parameters. This application note details the mechanisms of this distortion and presents validated protocols for mitigating its effects, thereby enhancing the reliability of VQE computations for applications such as molecular energy estimation in drug development.

The Impact of Noise on the Variational Landscape

Mechanisms of Landscape Distortion

Sampling noise fundamentally alters the features that a classical optimizer encounters during the variational search. The following table summarizes the key distortion phenomena and their direct consequences for optimization.

Table 1: Phenomena of Variational Landscape Distortion and Their Consequences

| Distortion Phenomenon | Description | Consequence for Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| False Variational Minima | Spurious local minima appear in the landscape solely due to statistical fluctuations in energy measurements [9]. | Optimizer is trapped in parameter sets that do not correspond to the true ground state. |

| Stochastic Variational Bound Violation | The estimated energy falls below the true ground state energy, ⟨H⟩est < E0, violating the variational principle [9]. | Loss of a rigorous lower bound, making it impossible to judge solution quality. |

| 'Winner's Curse' Bias | In population-based optimization, the best individual's energy is artificially low due to being selected from noisy evaluations [10] [11]. | Premature convergence as the optimizer chases statistical artifacts rather than true improvements. |

| Gradient Obscuration | The signal of the cost function's curvature is overwhelmed when the noise amplitude becomes comparable to it [11]. | Gradient-based optimizers (SLSQP, BFGS) diverge or stagnate due to unreliable gradient information [10]. |

Visualizing the Distortion

The diagram below illustrates the transformative effect of sampling noise on a smooth variational landscape, leading to the pitfalls described above.

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Noise Effects

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Optimizer Resilience

This protocol outlines a method to systematically evaluate the performance of different classical optimizers under controlled sampling noise, as performed in recent studies [10] [9].

1. Problem Initialization:

- Select Benchmark Systems: Choose a set of molecular Hamiltonians of increasing complexity. Exemplary systems include Hâ‚‚, linear Hâ‚„, and LiH (in both full and active spaces) [10] [9].

- Define Ansatz: Select a parameterized quantum circuit. Studies have used the truncated Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz (tVHA) and hardware-efficient ansätze (HEA) to generalize findings [10].

- Set Noise Level: Define the sampling budget, typically the number of shots (Nshots) per energy evaluation. Lower shots correspond to higher noise.

2. Optimizer Configuration:

- Assemble Optimizers: Select a portfolio of optimizers from different classes:

- Standardize Initialization: Use identical initial parameters and convergence thresholds for all optimizers to ensure a fair comparison.

3. Execution and Data Collection:

- Run each optimizer on the defined problems and record the optimization trajectories.

- For population-based algorithms (e.g., CMA-ES, iL-SHADE), track both the best individual and the population mean energy [11].

4. Analysis:

- Convergence Reliability: Calculate the success rate of each optimizer in reaching energies near the known ground state.

- Bias Assessment: Compare the final "best" energy to a high-precision reference. The 'winner's curse' will manifest as a large, consistent negative bias in the best individual. Verify that the population mean is a less biased estimator [11].

- Resource Efficiency: Measure the number of function evaluations (quantum circuit executions) required for convergence.

Protocol 2: Quantifying the 'Winner's Curse' Bias

This protocol provides a direct method to quantify the 'winner's curse' bias and validate the population mean tracking mitigation strategy.

1. Experimental Setup:

- Choose a single molecular system (e.g., Hâ‚‚ or LiH) and a fixed ansatz.

- Select a population-based metaheuristic optimizer such as CMA-ES.

2. Data Acquisition:

- Run the optimizer for a fixed number of generations under a strong noise condition (e.g., Nshots = 100 - 1000).

- In each generation, record the following for the entire population:

- The energy of the best individual.

- The mean energy of the entire population.

- The true energy (computed with high shots, e.g., 10âµ) for both the best individual and the population mean.

3. Data Analysis:

- Plot the estimated energies (best and mean) and the true energies against the generation number.

- Calculate the bias for each generation: Biasbest = True Energybest - Estimated Energybest and Biasmean = True Energymean - Estimated Energymean.

- The 'winner's curse' is empirically demonstrated if Biasbest is consistently positive and significantly larger than Biasmean [11].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for VQE Noise Studies

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Exemplary Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Optimizers (CMA-ES, iL-SHADE) | Adaptive metaheuristic algorithms that implicitly average noise via population dynamics, identified as most resilient [10] [11]. | Navigating noisy, rugged landscapes and mitigating the 'winner's curse' via population mean tracking. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | A technique to characterize and model readout errors on the quantum device, enabling the construction of an unbiased estimator for observables [3]. | Mitigating systematic measurement errors to achieve high-precision energy estimation, e.g., reducing errors to ~0.16% [3]. |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | An error mitigation technique that intentionally increases noise levels to extrapolate back to a zero-noise expectation value [4]. | Mitigating the combined effects of gate and decoherence noise on measured energies, often combined with neural networks for fitting [4]. |

| Grouped Pauli Measurements | A strategy that groups simultaneously measurable Pauli terms from the Hamiltonian to minimize the total number of circuit executions required [4]. | Reducing sampling overhead and measurement noise for complex molecular Hamiltonians (e.g., BODIPY) [4] [3]. |

| Matrix Product State (MPS) Circuits | A problem-inspired ansatz whose one-dimensional chain structure is effective for capturing local entanglement with shallow circuit depth [4]. | Providing a stable, pre-trainable circuit architecture that is less prone to noise-induced fluctuations during optimization [4]. |

| Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements | A measurement strategy that allows for the estimation of multiple observables from the same set of data [3]. | Reducing shot overhead and enabling efficient error mitigation via techniques like QDT [3]. |

Data Presentation: Quantitative Findings on Optimizer Performance and Error Reduction

Recent empirical studies have yielded quantitative data on optimizer performance under noise and the efficacy of various error reduction strategies. The following tables consolidate these key findings.

Table 3: Benchmarking Results of Classical Optimizers Under Sampling Noise [10] [9] [11]

| Optimizer | Class | Performance under High Noise | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES | Adaptive Metaheuristic | Most Effective / Resilient | Implicit noise averaging; suitable for population mean tracking. |

| iL-SHADE | Adaptive Metaheuristic | Most Effective / Resilient | Success-history based parameter adaptation; high resilience. |

| SLSQP | Gradient-based | Diverges or Stagnates | Fails when cost curvature is comparable to noise amplitude. |

| BFGS | Gradient-based | Diverges or Stagnates | Relies on accurate gradients, which are obscured by noise. |

| COBYLA | Gradient-free | Moderate | Less affected by noisy gradients but can converge to false minima. |

Table 4: Efficacy of Sampling Error Reduction Strategies [6] [4] [3]

| Strategy | Principle | Reported Efficacy |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient Splitting & Shifting | Optimizes measurement of Hamiltonian terms across different circuits to reduce variance [6]. | Reduces sampling cost by a factor of 20–500 for quantum Krylov methods [6]. |

| Grouped Pauli Measurements | Minimizes the number of distinct circuit configurations that need to be measured [4]. | Reduces number of samplings and mitigates measurement noise [4]. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | Characterizes and corrects for readout errors in measurement apparatus [3]. | Reduces absolute estimation error by an order of magnitude (from 1-5% to 0.16%) [3]. |

| Population Mean Tracking | Uses the population mean, rather than the best individual, as a less biased estimator [10] [11]. | Corrects for the 'winner's curse' bias in population-based optimizers. |

The distortion of the variational landscape by sampling noise presents a fundamental obstacle to reliable VQE experimentation. The emergence of false minima and the 'winner's curse' bias can severely mislead optimization. The protocols and data presented herein demonstrate that a strategic combination of resilient optimization algorithms—specifically adaptive metaheuristics like CMA-ES and iL-SHADE—and advanced measurement strategies—such as Hamiltonian term grouping, QDT, and population mean tracking—is essential for robust results. Future work must integrate these sampling noise strategies with methods that mitigate other hardware noise sources (e.g., gate errors, decoherence) to fully unlock the potential of VQE for practical drug development applications on NISQ-era quantum processors.

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for determining molecular ground state energies, a fundamental problem in quantum chemistry and drug development [12]. Based on the Rayleigh-Ritz variational principle, VQE leverages parameterized quantum circuits to generate trial wavefunctions while employing classical optimizers to minimize the expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian [13]. This approach has demonstrated significant potential for solving electronic structure problems that remain intractable for classical computational methods as molecular complexity increases [14]. The algorithm's hybrid nature makes it particularly suited for noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, which represent the current state of quantum computing technology [15].

Despite early successes with small molecules such as H₂, scaling VQE to complex molecular systems presents substantial challenges, including limited qubit availability, quantum hardware noise, and the barren plateau phenomenon where gradients vanish exponentially with increasing qubit count [15]. This application note examines critical advances in VQE methodologies that enable more accurate molecular energy estimation across a range of molecular complexities, with particular emphasis on measurement strategies that mitigate sampling noise – a fundamental limitation in near-term quantum computations.

Fundamental VQE Framework and Protocols

Core Algorithmic Structure

The VQE algorithm operates through an iterative process that combines quantum circuit evaluations with classical optimization. The molecular energy estimation problem is formulated as:

[ E(\Theta,R) = \langle \Psi(\Theta) | H(R) | \Psi(\Theta) \rangle ]

where (H(R)) represents the molecular Hamiltonian parameterized by nuclear coordinates (R), and (\Psi(\Theta)) denotes the trial wavefunction parameterized by variational parameters (\Theta) [13]. The algorithm solves the optimization problem (\min_{\Theta,R} E(\Theta,R)) through repeated quantum measurements and classical parameter updates.

Table: Core Components of the VQE Framework

| Component | Description | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Hamiltonian Formulation | Mathematical representation of molecular energy | Jordan-Wigner transformation of molecular Hamiltonian into Pauli terms [13] |

| Ansatz Design | Parameterized quantum circuit for trial wavefunctions | Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCCSD), hardware-efficient ansätze [14] |

| Quantum Measurement | Estimation of expectation values | Finite sampling from quantum circuits [11] |

| Classical Optimization | Parameter adjustment to minimize energy | Gradient-based methods, metaheuristics [15] |

Basic Experimental Protocol: Hydrogen Molecule

The hydrogen molecule serves as the fundamental test case for VQE implementations. The standard protocol for Hâ‚‚ ground state energy calculation comprises the following steps:

Hamiltonian Specification: For a bond distance of 0.742 Ã…, the Hamiltonian is constructed from 15 Pauli terms with predetermined coefficients:

PauliTerms = ["IIII", "ZIII", "IZII", "ZZII", "IIZI", "ZIZI", "IIIZ", "ZIIZ", "IZZI", "IZIZ", "IIZZ", "YXXY", "XYYX", "XXYY", "YYXX"][13]Circuit Initialization: A double excitation gate parameterizes the trial wavefunction using the transformation: (|\Psi(\theta)\rangle = \cos(\theta/2)|1100\rangle - \sin(\theta/2)|0011\rangle) where the first term represents the Hartree-Fock state and the second represents a double excitation [13].

Energy Measurement: The expectation value of the Hamiltonian is measured using either local simulation or quantum processing units (QPUs) such as IBM's "ibm_fez" device [13].

Parameter Optimization: The parameter θ is optimized through:

- Exhaustive Search: Evaluating energy across θ = -0.5 to 1.0 rad in 0.001 rad increments

- Gradient Descent: Employing the parameter-shift rule for gradient calculation: (\frac{\partial E(\theta)}{\partial \theta} = \frac{E(\theta+s) - E(\theta-s)}{2\sin(s)}) with (s = \pi/2) [13]

This protocol typically identifies the minimum energy of -1.1373 hartrees at θ = 0.226 rad for the H₂ molecule [13].

Figure 1: VQE Protocol for Hâ‚‚ Ground State Energy Calculation

Scaling Challenges and Noise Resilience Strategies

The Sampling Noise Problem in VQE

As VQE scales to larger molecular systems, sampling noise emerges as a critical barrier to accurate energy estimation. Finite-shot sampling distorts the cost landscape, creating false minima and inducing the "winner's curse" where statistical minima appear below the true ground state energy [11]. This noise arises from the fundamental quantum measurement process, where the precision of expectation value estimates scales as (1/\sqrt{N}) with (N) measurement shots [15]. The resulting landscape deformations are particularly problematic for gradient-based optimization methods, which struggle when cost curvature approaches the noise amplitude [11].

Visualization studies reveal that smooth, convex basins in noiseless cost landscapes become distorted and rugged under finite-shot sampling, explaining the failure of local gradient-based methods [11] [15]. Research demonstrates that sampling noise alone can disrupt variational landscape structure, creating a multimodal optimization surface that traps local search methods in suboptimal solutions [15]. This effect is especially pronounced in strongly correlated systems like the Fermi-Hubbard model, where the inherent landscape complexity compounds with stochastic noise effects [15].

Noise-Resilient Optimization Strategies

Recent benchmarking of over fifty metaheuristic algorithms for VQE optimization has identified several strategies that demonstrate particular resilience to sampling noise:

Table: Performance of Optimization Algorithms in Noisy VQE Landscapes

| Algorithm | Noise Resilience | Key Characteristics | Molecular Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES | Excellent | Population-based, adaptive covariance matrix | Consistent performance across Hâ‚‚, Hâ‚„, LiH Hamiltonians [11] [15] |

| iL-SHADE | Excellent | Advanced differential evolution variant | Robust performance in 192-parameter Hubbard model [15] |

| Simulated Annealing (Cauchy) | Good | Physics-inspired, probabilistic acceptance | Effective for Ising model with sampling noise [15] |

| Harmony Search | Good | Musician-inspired, maintains harmony memory | Competitive in 9-qubit scaling tests [15] |

| Symbiotic Organisms Search | Good | Biological symbiosis-inspired | Shows robustness in noisy conditions [15] |

| Standard PSO/GA | Poor | Standard population methods | Sharp performance degradation with noise [15] |

A critical innovation for noise mitigation involves correcting estimator bias by tracking the population mean rather than relying on the best individual when using population-based optimizers [11]. This approach directly addresses the "winner's curse" by preventing overfitting to statistical fluctuations. Additionally, ensemble methods and careful circuit design have shown promise in improving accuracy and robustness despite noisy conditions [11].

Advanced Protocols for Complex Molecular Systems

Fragment Molecular Orbital VQE (FMO/VQE)

For complex molecular systems beyond the capabilities of standard VQE, the Fragment Molecular Orbital approach combined with VQE (FMO/VQE) represents a significant advancement in scalability [14]. This method enables quantum chemistry simulations of large systems by dividing them into smaller fragments that can be processed with available qubits.

The FMO/VQE protocol comprises these critical steps:

System Fragmentation: The target molecular system is divided into individual fragments, typically following chemical intuition (e.g., each hydrogen molecule in Hâ‚‚â‚„ clusters treated as a fragment) [14].

Monomer SCF Calculations: The molecular orbitals on each fragment are optimized using the Self-Consistent Field theory in the external electrostatic potential generated by surrounding fragments [14].

Dimer SCF Calculations: Pair interactions between fragments are computed to capture inter-fragment electron correlations [14].

Quantum Energy Estimation: The VQE algorithm with UCCSD ansatz is applied to each fragment using the Hamiltonian: (\hat{H}{I} \Psi{I} = E{I} \Psi{I}) where (\hat{H}_{I}) represents the Hamiltonian for monomer (I) [14].

Total Property Evaluation: The total energy is computed by combining the fragment energies with interaction corrections [14].

This approach has demonstrated remarkable accuracy, achieving an absolute error of just 0.053 mHa with 8 qubits in a Hâ‚‚â‚„ system using the STO-3G basis set, and an error of 1.376 mHa with 16 qubits in a Hâ‚‚â‚€ system with the 6-31G basis set [14].

Handling Unsupported Atoms in Molecular Simulations

For complex molecules containing atoms beyond the standard supported set in quantum chemistry packages (e.g., CuO), researchers can employ alternative backends such as the OpenFermion-PySCF package [16]. The protocol involves:

- Backend Specification: Adding the method='pyscf' argument when generating the molecular Hamiltonian

- Hamiltonian Construction: Building the Hamiltonian with support for extended atomic types

- Circuit Execution: Proceeding with standard VQE optimization procedures

This approach enables researchers to study biologically relevant systems containing transition metals and other elements crucial for drug development applications [16].

Figure 2: FMO/VQE Workflow for Complex Molecular Systems

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Critical Computational Tools for VQE Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Software Frameworks | Qiskit (IBM) [17], PennyLane [16] | Circuit construction, algorithm implementation | Hâ‚‚ molecule simulation; CuO complex molecule handling |

| Classical Optimization Libraries | Mealpy, PyADE [11] | Metaheuristic algorithm implementations | Noise-resilient optimization with CMA-ES, iL-SHADE |

| Quantum Chemistry Backends | OpenFermion-PySCF [16] | Hamiltonian generation for unsupported atoms | Complex molecules with transition metals |

| Fragment Molecular Orbital Methods | FMO/VQE implementation [14] | Divide-and-conquer quantum simulation | Large systems like Hâ‚‚â‚„, Hâ‚‚â‚€ with reduced qubit requirements |

| Error Mitigation Tools | Population mean tracking [11] | Sampling noise reduction | Correcting estimator bias in stochastic landscapes |

The evolution of VQE methodologies from simple Hâ‚‚ molecules to complex molecular systems demonstrates significant progress in quantum computational chemistry. Critical advances in noise-resilient optimization strategies, particularly population-based metaheuristics like CMA-ES and iL-SHADE, have addressed fundamental challenges in sampling noise that previously limited VQE accuracy and reliability [11] [15]. The development of fragment-based approaches such as FMO/VQE has successfully extended the reach of quantum simulations to larger systems while maintaining accuracy with limited qubit resources [14].

For drug development professionals and research scientists, these advances enable more accurate estimation of molecular properties crucial to understanding biological interactions and drug design. The integration of noise mitigation strategies directly into optimization protocols represents a practical approach to overcoming the limitations of current NISQ devices. As quantum hardware continues to advance, combining these algorithmic innovations with improved physical qubit counts and coherence times will further expand the accessible chemical space for quantum-assisted drug discovery.

Future research directions should focus on optimizing measurement strategies to reduce circuit repetitions, large-scale parallelization across quantum computers, and developing methods to overcome vanishing gradients in optimization processes [12]. Additionally, investigating the combined impact of various noise sources and developing comprehensive mitigation strategies will be essential for achieving quantum advantage in complex molecular simulations.

Connecting Measurement Error to Algorithmic Instability and Optimization Failure

In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithm for molecular energy estimation, particularly for quantum chemistry applications in drug development [18] [19]. However, its practical implementation is severely challenged by finite-shot sampling noise, which fundamentally distorts optimization landscapes and induces algorithmic instability [9] [11]. This application note examines the causal relationship between measurement error and optimization failure, providing researchers with validated protocols to enhance the reliability of VQE calculations for molecular systems.

Measurement noise originates from the statistical uncertainty inherent in estimating expectation values from a finite number of quantum measurements ("shots") [9]. For drug development researchers investigating molecular systems, this sampling noise creates a significant reliability gap between theoretical potential and practical implementation, ultimately limiting the utility of quantum computations for predicting molecular properties critical to pharmaceutical design [19].

Quantitative Impact of Sampling Noise

Statistical Distortions in the Variational Landscape

Finite-shot sampling introduces Gaussian-distributed noise to energy estimations, fundamentally altering the optimization landscape that classical optimizers must navigate [9]. The measured energy expectation value becomes:

[ \bar{C}(\bm{\theta}) = C(\bm{\theta}) + \epsilon{\text{sampling}}, \quad \epsilon{\text{sampling}} \sim \mathcal{N}(0,\sigma^2/N_{\mathrm{shots}}) ]

where (C(\bm{\theta})) is the true noise-free expectation value and (N_{\mathrm{shots}}) is the number of measurement shots [9]. This noise manifestation produces two critical failure modes:

- False Variational Minima: Noise-induced fluctuations create local minima in the energy landscape that do not correspond to physically meaningful states [9] [11]. These illusory minima can trap optimizers in suboptimal regions of parameter space, preventing convergence to the true ground state.

- Stochastic Variational Bound Violation: The variational principle guarantees that the true energy expectation value should always be greater than or equal to the exact ground state energy. However, sampling noise can cause the measured energy to artificially dip below this theoretical threshold, violating the variational bound and producing unphysical results [9].

The Winner's Curse Phenomenon

In population-based optimization, a statistical bias known as the "winner's curse" occurs when the best-observed energy value is systematically lower than its true expectation value due to random fluctuations [9] [11]. This bias emerges because we selectively track the minimum noisy measurement rather than the true energy, causing optimizers to converge to parameters that appear superior due solely to statistical artifacts rather than genuine physical merit.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Sampling Noise on VQE Optimization

| Noise Effect | Impact on Optimization | Experimental Manifestation | Reported Severity |

|---|---|---|---|

| False Minima | Premature convergence to suboptimal parameters | Stagnation well above chemical accuracy (>1 mHa) [5] | 60-80% convergence failure in noisy ADAPT-VQE [5] |

| Winner's Curse | Systematic underestimation of achieved energy | Apparent violation of variational principle [9] | Biases of 2-5 mHa in molecular energies [9] |

| Gradient Corruption | Loss of reliable direction for parameter updates | Divergence/stagnation of gradient-based methods [9] | SLSQP, BFGS failure when curvature ≈ noise level [9] |

| Barren Plateaus | Exponentially vanishing gradients | Flat landscapes indistinguishable from noise [9] | Exponential concentration in parameter space [9] |

Experimental Evidence and Performance Benchmarks

Recent systematic benchmarking across quantum chemistry Hamiltonians (Hâ‚‚, Hâ‚„, LiH) reveals distinct optimizer performance degradation under sampling noise [9]. Gradient-based methods (SLSQP, BFGS) diverge or stagnate when the cost curvature approaches the noise amplitude, while gradient-free black-box optimizers (COBYLA, SPSA) struggle to navigate the resulting rugged, multimodal landscapes [9].

Visualizations of variational landscapes demonstrate how smooth, convex basins in noiseless simulations deform into rugged, multimodal surfaces under realistic shot noise [11]. This topological transformation explains why optimizers that perform excellently in noiseless simulations often fail dramatically under experimental conditions.

Table 2: Optimizer Performance Under Sampling Noise

| Optimizer Class | Representative Algorithms | Noise Resilience | Key Limitations | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-Based | SLSQP, BFGS, Adam | Low | Gradient corruption, curvature noise sensitivity | Only for high-shot regimes (>10âµ shots) [9] |

| Gradient-Free | COBYLA, SPSA | Medium | Slow convergence, local minima trapping | Small molecules (< 6 qubits) with moderate shot counts [9] |

| Quantum-Aware | Rotosolve, ExcitationSolve | Medium-High | Limited to specific ansatz types [20] | Fixed UCC-style ansätze with excitation operators [20] |

| Metaheuristic | CMA-ES, iL-SHADE | High | Higher computational overhead per iteration | Complex molecules, strong correlation, noisy regimes [9] [11] |

Causal Pathway from Measurement Error to Optimization Failure

The relationship between measurement error and optimization failure follows a well-defined causal pathway that can be visualized and systematically addressed. The following diagram illustrates this cascade of effects and potential mitigation points:

Causal Pathway from Measurement Error to Optimization Failure

Shot-Efficient Measurement Protocols

Variance-Based Shot Allocation

Theoretical optimum allocation strategies dynamically distribute measurement shots based on the variance of individual Hamiltonian terms [18] [9]. For a Hamiltonian ( H = \sumi \alphai Pi ) decomposed into Pauli terms ( Pi ), the optimal shot allocation follows:

[ Ni \propto \frac{|\alphai| \sqrt{\text{Var}(Pi)}}{\sumj |\alphaj| \sqrt{\text{Var}(Pj)}} ]

where ( Ni ) is the number of shots allocated to term ( Pi ), ( \alphai ) is its coefficient, and ( \text{Var}(Pi) ) is the variance of the expectation value [18]. This approach achieves 6.71-51.23% shot reduction compared to uniform allocation while maintaining accuracy [18].

Pauli Measurement Reuse in ADAPT-VQE

For adaptive VQE variants, significant shot reduction comes from reusing Pauli measurement outcomes obtained during VQE parameter optimization in subsequent operator selection steps [18]. This protocol exploits the overlap between Pauli strings in the Hamiltonian and those generated by commutators of the Hamiltonian with operator pool elements.

Experimental Protocol: Pauli Measurement Reuse

- Initial Setup: Identify overlapping Pauli strings between Hamiltonian measurement requirements and anticipated gradient measurements for operator selection

- Measurement Execution: Perform grouped Pauli measurements during VQE optimization phase

- Data Caching: Store measurement outcomes with appropriate metadata (parameter values, circuit version)

- Operator Selection: Reuse compatible measurements for gradient calculations in ADAPT-VQE operator selection

- Validation: Cross-verify with minimal fresh measurements to ensure consistency

This approach reduces average shot usage to 32.29% compared to naive measurement schemes [18].

Noise-Resilient Optimization Methods

Robust Optimizer Selection and Configuration

Adaptive metaheuristics, particularly CMA-ES and iL-SHADE, demonstrate superior performance under sampling noise due to their implicit averaging of stochastic evaluations and population-based search strategies [9] [11]. The key advantage lies in their ability to track population means rather than overfitting to potentially biased best individuals.

Experimental Protocol: CMA-ES for Noisy VQE Optimization

- Population Initialization:

- Initialize population size ( \lambda = 4 + \lfloor 3 \ln N \rfloor ) where ( N ) is parameter count

- Sample initial population around Hartree-Fock or chemically-informed initial parameters

Sampling and Evaluation:

- Generate ( \lambda ) candidate parameter vectors: ( x_k \sim m + \sigma \mathcal{N}(0, C) )

- Evaluate energy for each candidate with sufficient shots to control noise (typically ( 10^4 - 10^5 ) shots)

- Apply measurement reuse and shot allocation strategies where possible

Selection and Update:

- Select ( \mu = \lfloor \lambda/2 \rfloor ) best candidates

- Update distribution parameters: ( m \leftarrow \sum{i=1}^\mu wi x_{i:\lambda} $

- Update covariance matrix and evolution paths

Termination Criteria:

- Energy stability: ( |E{best}^{(k)} - E{best}^{(k-50)}| < 10^{-4} ) Ha

- Distribution collapse: ( \sigma < 10^{-6} $

- Maximum iterations (typically 1000)

Gradient-Free Quantum-Aware Optimizers

For specific ansatz classes, gradient-free optimizers leverage analytical knowledge of the energy landscape. ExcitationSolve extends Rotosolve-type optimizers to handle excitation operators with generators satisfying ( Gj^3 = Gj ) [20]. The energy dependence on a single parameter follows a second-order Fourier series:

[ f{\theta}(\thetaj) = a1 \cos(\thetaj) + a2 \cos(2\thetaj) + b1 \sin(\thetaj) + b2 \sin(2\thetaj) + c ]

requiring only five energy evaluations to determine the global optimum along that parameter [20].

Error Mitigation Integration

Multireference Error Mitigation (MREM)

For strongly correlated systems relevant to pharmaceutical applications, Multireference State Error Mitigation (MREM) extends the original REM protocol by using multiple reference states to capture hardware noise characteristics [21]. This approach is particularly valuable when single-reference states (e.g., Hartree-Fock) provide insufficient overlap with the true ground state.

Experimental Protocol: MREM Implementation

- Reference State Selection:

- Identify dominant Slater determinants from inexpensive classical methods (CASSCF, DMRG)

- Select 3-5 determinants ensuring substantial cumulative overlap with target state

Circuit Preparation:

- Implement reference states using Givens rotations for symmetry preservation

- Maintain particle number and spin symmetry throughout

Noise Characterization:

- Prepare and measure each reference state on quantum hardware

- Compute exact noiseless energies classically

Error Extrapolation:

- Apply linear or polynomial fit to noisy vs. exact energies across references

- Use fit to mitigate target state energy measurement

MREM demonstrates significant improvement over single-reference REM for challenging systems like Nâ‚‚ and Fâ‚‚ bond dissociation [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Noise-Resilient VQE

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function | Implementation Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Optimizers | Variance-Based Shot Allocation [18] | Dynamically distributes shots to minimize total variance | Requires variance estimation; compatible with grouping |

| Pauli Grouping Strategies | Qubit-Wise Commutativity [18] | Groups commuting Pauli terms for simultaneous measurement | Reduces measurement overhead by ~60% [18] |

| Noise-Resilient Optimizers | CMA-ES [9] [11] | Population-based evolutionary strategy | Automatic covariance adaptation; implicit noise averaging |

| Quantum-Aware Optimizers | ExcitationSolve [20] | Gradient-free optimizer for excitation operators | Specifically for UCC-style ansätze; 5 evaluations per parameter |

| Error Mitigation | Multireference EM [21] | Leverages multiple reference states for noise characterization | Essential for strongly correlated systems |

| Alternative Cost Functions | WCVaR [22] | Weighted Conditional Value-at-Risk | Focuses optimization on low-energy tail of measurement distribution |

| Amantanium Bromide | Amantanium Bromide, CAS:58158-77-3, MF:C25H46BrNO2, MW:472.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Antroquinonol | Antroquinonol, CAS:1010081-09-0, MF:C24H38O4, MW:390.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Measurement error presents a fundamental challenge to reliable VQE optimization for drug development applications, inducing algorithmic instability through false minima, winner's curse bias, and gradient corruption. However, integrated strategies combining shot-efficient measurement protocols, noise-resilient optimizers like CMA-ES, and advanced error mitigation techniques like MREM can significantly enhance reliability. For researchers pursuing quantum chemistry calculations on near-term hardware, a systematic co-design of measurement strategies, optimization algorithms, and error mitigation is essential for producing chemically meaningful results. The protocols outlined herein provide a pathway toward more robust quantum computations for molecular systems relevant to pharmaceutical development.

Practical Methods for Reducing Sampling Overhead and Measurement Error in VQE

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithms have emerged as a promising approach for quantum chemistry simulations on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. These hybrid quantum-classical algorithms aim to solve the electronic structure problem for molecular systems by finding the ground state energy of the Hamiltonian. However, a significant bottleneck in practical implementations is the exceptionally high number of quantum measurements (shots) required to estimate the energy expectation value and its gradients with sufficient precision [18].

The molecular Hamiltonian in quantum chemistry is typically expressed as a linear combination of Pauli string operators: $$H = \sum{i=1}^{M} ci Hi$$ where $ci$ are real coefficients and $H_i$ denotes tensor products of Pauli operators ($X$, $Y$, $Z$, or $I$) [4]. Measuring each of these terms individually would require an impractically large number of quantum executions, making the computation prohibitively expensive for current quantum hardware.

Intelligent Pauli string measurement strategies address this challenge through two complementary approaches: grouping techniques that allow simultaneous measurement of compatible operators, and shot allocation methods that optimize measurement distribution based on statistical properties. When combined, these strategies can dramatically reduce the quantum resources required for chemical accuracy in VQE simulations [18].

Theoretical Foundation of Pauli Measurements

Pauli Operators and Quantum Measurement

In quantum computing, Pauli measurements generalize computational basis measurements to include measurements in different bases and of parity between qubits. The fundamental Pauli operators ($X$, $Y$, $Z$) have eigenvalues ±1 with corresponding eigenspaces that each constitute half of the available state space [23].

For multi-qubit systems, Pauli measurements can be represented as tensor products of single-qubit Pauli operators (e.g., $X⊗Z$, $Y⊗Y$, $Z⊗I$). These operators similarly have only two unique eigenvalues (±1), with each eigenspace comprising exactly half of the total Hilbert space. The key insight for measurement reduction is that not all Pauli operators need to be measured separately—certain operators commute and can be measured simultaneously [23].

Commutativity Relationships for Operator Grouping

Two Pauli operators $Pi$ and $Pj$ can be measured simultaneously if they commute ($[Pi, Pj] = 0$), meaning their corresponding measurement circuits can be consolidated. The most commonly exploited commutativity relationships include:

- Qubit-wise commutativity (QWC): Two Pauli operators commute qubit-wise if for every qubit position, the single-qubit operators commute (i.e., they are identical or one is the identity). QWC grouping is efficient to compute and implement experimentally [18].

- General commutativity: Broader commutativity based on the algebraic property $[Pi, Pj] = 0$, which includes but is not limited to QWC. This enables larger groups but may require more complex measurement circuits [18].

The critical advantage of grouping is that measuring a group of $k$ commuting operators requires similar quantum resources (circuit depth, execution time) as measuring a single operator, yet provides information about all $k$ terms simultaneously.

Grouping Methodologies and Protocols

Qubit-Wise Commutativity Grouping Protocol

Objective: Partition the set of Hamiltonian Pauli terms into the minimum number of groups where all terms within each group commute qubit-wise.

Experimental Procedure:

- Term Representation: Convert each Hamiltonian term to its Pauli string representation with explicit qubit indices.

- Compatibility Graph Construction: Create a graph where vertices represent Pauli terms and edges connect terms that commute qubit-wise.

- Graph Coloring Solution: Solve the graph coloring problem to partition the graph into the minimum number of color classes, where each color corresponds to a measurement group.

- Measurement Circuit Generation: For each group, construct a unitary transformation $U$ that simultaneously diagonalizes all operators in the group to the computational basis.

- Parallel Execution: Implement the measurement circuits on quantum hardware, allocating shots according to variance-based optimization.

Table: Qubit-Wise Commutativity Grouping Examples

| Hamiltonian | Original Terms | After QWC Grouping | Reduction Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ (4 qubits) | 15 terms | 5 groups | 66.7% |

| LiH (14 qubits) | 150 terms | 45 groups | 70.0% |

| BeHâ‚‚ (14 qubits) | 225 terms | 62 groups | 72.4% |

General Commutativity with Commutator Grouping

Objective: Extend beyond QWC to exploit general commutativity relationships, potentially including commutators of Hamiltonian terms with operator pool elements in adaptive VQE approaches [18].

Advanced Protocol:

- Commutator Identification: For ADAPT-VQE applications, compute commutators $[H, Ï„i]$ between the Hamiltonian $H$ and operator pool elements $Ï„i$.

- Commutator Grouping: Apply grouping strategies to the resulting commutator expressions, which themselves consist of Pauli strings.

- Unitary Construction: Design measurement circuits that leverage general commutativity rather than just qubit-wise compatibility.

- Resource Balancing: Balance the reduced measurement count against potentially more complex measurement circuits requiring additional two-qubit gates.

This approach has demonstrated particular value in ADAPT-VQE, where the operator selection step requires measuring numerous gradient observables in addition to the Hamiltonian itself [18].

Variance-Based Shot Allocation Strategies

Theoretical Framework for Optimal Allocation

While grouping reduces the number of distinct measurement circuits, variance-based shot allocation optimizes how many times each circuit should be executed. The core principle is to allocate more shots to terms with higher statistical uncertainty and larger contribution to the total energy [18].

For a Hamiltonian $H = ΣciPi$ (after grouping), the total variance in energy estimation is: $$\text{Var}(E) = \sum{i=1}^M \frac{ci^2 \text{Var}(Pi)}{Si}$$ where $Si$ is the number of shots allocated to measure group $i$, and $\text{Var}(Pi)$ is the variance of operator $P_i$ with respect to the current quantum state [18].

Implementation Protocols

VMSA (Variance-Based Shot Allocation) Protocol:

- Initial Shot Distribution: Perform an initial calibration run with a small number of shots (e.g., 100-1000) per group to estimate variances.

- Variance Estimation: Compute $\text{Var}(Pi) = ⟨Pi^2⟩ - ⟨P_i⟩^2$ for each measurement group.

- Optimal Allocation Calculation: Distribute a fixed total shot budget $S{\text{total}}$ according to: $$Si = S{\text{total}} \times \frac{|ci| \sqrt{\text{Var}(Pi)}}{\sumj |cj| \sqrt{\text{Var}(Pj)}}$$

- Iterative Refinement: Periodically re-estimate variances during VQE optimization as the quantum state changes.

VPSR (Variance-Based Progressive Shot Reduction) Protocol:

- Baseline Establishment: Begin with high shot counts to establish precise variance estimates.

- Progressive Reduction: Systematically reduce shots for terms whose energy contribution falls below a significance threshold.

- Dynamic Reallocation: Continuously shift shots from well-converged terms to terms with higher uncertainty.

Table: Performance Gains from Combined Strategies in ADAPT-VQE

| Molecule | QWC Grouping Alone | VPSR Shot Allocation | Combined Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | 38.59% shot reduction | 43.21% shot reduction | 65-70% shot reduction |

| LiH | 35-40% shot reduction | 51.23% shot reduction | 70-75% shot reduction |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 38.59% shot reduction | ~45% shot reduction | ~68% shot reduction |

Integrated Workflow for Shot-Efficient ADAPT-VQE

Diagram 1: Shot-optimized ADAPT-VQE workflow with measurement reuse and variance-based allocation.

Measurement Reuse Strategy

A particularly innovative approach in recent research involves reusing Pauli measurement outcomes obtained during VQE parameter optimization in the subsequent operator selection step [18]. This strategy exploits the fact that:

- Overlapping Pauli Sets: The Hamiltonian measurement and gradient estimation via commutators often share common Pauli strings.

- Classical Storage: Measurement outcomes for each Pauli string can be classically stored and reused across algorithm iterations.

- Incremental Updates: As new operators are added to the ansatz, only new Pauli strings require additional quantum measurements.

This protocol reduces the shot overhead in ADAPT-VQE by 32.29% compared to naive measurement approaches, while maintaining chemical accuracy across various molecular systems [18].

Experimental Validation and Performance Analysis

Molecular Test Systems

The shot-efficient strategies have been validated across multiple molecular systems:

- Small molecules: Hâ‚‚ (4 qubits) serving as a minimal test case

- Medium systems: LiH and BeHâ‚‚ (14 qubits) representing more chemically relevant systems

- Complex systems: Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„ with 8 active electrons and 8 active orbitals (16 qubits) demonstrating scalability [18]

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table: Comprehensive Shot Reduction Across Multiple Strategies

| Optimization Method | Hâ‚‚ Shot Reduction | LiH Shot Reduction | BeHâ‚‚ Shot Reduction | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QWC Grouping | 38.59% | 37.2% | 38.59% | Low |

| General Commutativity | 42.7% | 45.1% | 46.3% | Medium |

| VMSA Allocation | 6.71% | 5.77% | ~7% | Low |

| VPSR Allocation | 43.21% | 51.23% | ~45% | High |

| Measurement Reuse | 32.29% | 30.5% | 31.8% | Medium |

| Combined Approach | 68.4% | 72.1% | 70.5% | High |

Chemical Accuracy Maintenance

Crucially, these shot reduction strategies maintain chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa or ~1 kcal/mol error) while dramatically reducing quantum resource requirements. For the Hâ‚‚ molecule, the combined approach achieved:

- Energy error: < 0.001 Ha

- Shot reduction: 68.4% compared to unoptimized measurement

- Circuit depth: Reduced by adaptive ansatz construction [18]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Implementation

| Tool Name | Type | Function | Implementation Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qubit-wise Commutativity Checker | Algorithm | Identifies simultaneously measurable Pauli terms | Groups Hamiltonian terms with O(n²) complexity |

| Graph Coloring Solver | Software Module | Solves minimum coloring for commutativity graph | Implements greedy or exact coloring algorithms |

| Variance Estimator | Statistical Tool | Computes operator variances from quantum measurements | Guides optimal shot allocation in VMSA/VPSR |

| Pauli Measurement Reuse Database | Classical Storage | Stores and retrieves previous measurement outcomes | Eliminates redundant quantum executions |

| Commutator Analyzer | Symbolic Computation | Expands [H, Ï„_i] into Pauli terms | Enables gradient measurement in ADAPT-VQE |

Intelligent Pauli string measurement strategies represent a crucial advancement toward practical quantum chemistry on NISQ devices. By combining grouping methodologies with variance-based shot allocation, researchers can achieve substantial shot reductions of 65-75% while maintaining chemical accuracy.

The most promising direction emerging from recent research is the integration of multiple optimization strategies: QWC grouping for implementation simplicity, general commutativity for maximal term consolidation, variance-aware shot allocation for statistical efficiency, and measurement reuse across algorithm stages. This combined approach addresses both the number of distinct measurement circuits and the optimal distribution of shots among them.

As quantum hardware continues to evolve with innovations like AWS's Ocelot chip targeting reduced error rates [24], the measurement strategies outlined here will become increasingly critical for extracting maximum value from each quantum measurement. Future research directions should explore machine learning-enhanced shot allocation, dynamic grouping during VQE optimization, and hardware-aware grouping that considers specific device characteristics and connectivity.

Accurately measuring the expectation value of molecular Hamiltonians is a central and resource-intensive task in the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm. On near-term quantum devices, high readout errors and limited sampling statistics pose significant challenges for achieving chemical precision [3]. This application note details two advanced measurement strategies—Locally-Biased Classical Shadows (LBCS) and Informationally Complete (IC) measurements—that synergistically reduce sampling noise without increasing quantum circuit depth.

LBCS optimizes the probability distribution of single-qubit measurement bases to minimize the variance in estimating specific observables [25] [26]. IC measurements use a single, fixed set of informationally complete basis rotations to characterize the quantum state, enabling the estimation of all Hamiltonian terms from the same dataset and providing a direct interface for error mitigation [27] [3]. Used individually or in combination, these strategies offer researchers a practical toolkit to significantly lower the measurement overhead in VQE experiments.

Core Theoretical Foundations

The Measurement Problem in VQE

The electronic structure Hamiltonian in quantum chemistry is expressed as a linear combination of Pauli operators: [ O = \sum{Q \in {I,X,Y,Z}^{\otimes n}} \alphaQ Q ] where each ( \alpha_Q \in \mathbb{R} ) [25] [26]. Directly measuring each term ( Q ) independently incurs a substantial resource overhead. The key to efficiency lies in grouping terms that are measurable in the same basis and in optimizing the shot allocation to reduce the overall statistical variance of the energy estimate ( \langle \psi(\theta) | O | \psi(\theta) \rangle ) [4] [28].

Locally-Biased Classical Shadows (LBCS)

The standard Classical Shadows protocol uses a uniform distribution ( \betai(Pi) = 1/3 ) to select measurement bases ( X, Y, Z ) for each qubit ( i ) [25] [26]. LBCS generalizes this by introducing a product probability distribution ( \beta = {\betai}{i=1}^n ), where ( \beta_i ) is a non-uniform probability distribution over ( {X, Y, Z} ) for the ( i )-th qubit [25] [26].

The estimator for the observable ( O ) is constructed as [26]: [ \nu = \frac{1}{S} \sum{s=1}^S \sum{Q} \alpha_Q f(P^{(s)}, Q, \beta) \mu(P^{(s)}, \text{supp}(Q)) ] where:

- ( S ) is the number of measurement shots.

- ( P^{(s)} ) is the full-weight Pauli operator selected for the ( s )-th shot according to distribution ( \beta ).

- ( \mu(P^{(s)}, \text{supp}(Q)) ) is the product of the ( \pm 1 ) measurement outcomes for qubits in the support of ( Q ).

- ( f(P, Q, \beta) = \prod{i=1}^n fi(Pi, Qi, \beta) ) is the rescaling function that ensures unbiasedness, defined qubit-wise as [26]: [ fi(Pi, Qi, \beta) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } Pi = I \text{ or } Qi = I \ (\betai(Pi))^{-1} & \text{if } Pi = Q_i \ne I \ 0 & \text{else} \end{cases} ]

This protocol provides an unbiased estimator, ( \mathbb{E}(\nu) = \text{tr}(\rho O) ), and its variance can be minimized by optimizing the distributions ( \beta_i ) based on prior knowledge of the Hamiltonian and a reference state [25] [26].

Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements

IC measurements offer a fundamentally different approach. Instead of biasing random measurements, a single, specific set of basis rotations (e.g., using ( U = H ) or ( U = HS^\dagger ) on each qubit) is performed to create an informationally complete positive operator-valued measure (POVM) [27] [3]. The key advantage is that the data from this fixed set of measurements can be reused to compute the expectation value of any observable, including all terms in the Hamiltonian, via classical post-processing [27].

This approach is particularly powerful for measurement-intensive algorithms like ADAPT-VQE, where the energy and the gradients for the operator pool can be estimated from the same IC dataset, eliminating the need for repeated quantum measurements for each commutator [27]. Furthermore, the fixed measurement setup allows for efficient parallel execution and simplifies the application of error mitigation techniques like Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) [3].

Synergistic Protocol: LBCS and IC Measurements

While LBCS and IC measurements can be used independently, their combination is highly effective. The AIM-ADAPT-VQE scheme uses IC measurements to reduce circuit overhead [27]. This IC framework can be enhanced by implementing LBCS principles to optimize the shot allocation across the different measurement settings, thereby further reducing the shot overhead while preserving the benefits of informational completeness [3].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated protocol for employing these strategies in a VQE experiment.

Experimental Validation and Performance Data

Performance of LBCS

The LBCS technique has been benchmarked for molecular Hamiltonians of increasing size, showing a consistent and sizable reduction in variance compared to unbiased classical shadows and other measurement protocols that do not increase circuit depth [25] [26]. The optimization of ( \beta ) relies on a classical reference state (e.g., Hartree-Fock or a multi-reference perturbation theory state) and the Hamiltonian coefficients [26].

Table 1: Variance Reduction from LBCS for Molecular Hamiltonians

| Molecule (Active Space) | Number of Qubits | Variance Reduction vs. Uniform Shadows |

|---|---|---|

| H$4 (4e4o) [4] | 8 | Consistent improvement observed [25] [26] |

| BODIPY-4 (8e8o) [3] | 16 | Significant reduction enabling high-precision measurement [3] |

| Larger molecules [26] | >20 | Sizable reduction maintained with increasing system size [26] |

Performance of IC Measurements and AIM-ADAPT-VQE

The AIM-ADAPT-VQE scheme, which uses IC measurements, was tested on several H$_4$ Hamiltonians. Numerical simulations demonstrated that the measurement data obtained for energy evaluation could be reused to estimate all commutators for the ADAPT-VQE operator pool with no additional quantum measurement overhead [27]. Furthermore, when the energy was measured within chemical precision, the resulting quantum circuits had a CNOT count close to the ideal one [27].

Combined Performance on Hardware

A comprehensive study implementing LBCS, IC measurements, and error mitigation achieved high-precision energy estimation for the BODIPY molecule on an IBM Eagle r3 quantum processor [3]. The techniques reduced the absolute error in the energy estimate by an order of magnitude, from 1-5% to 0.16%, bringing it close to the threshold of chemical precision (1.6 × 10$^{-3}$ Hartree) [3].

Table 2: Summary of Key Experimental Results from Literature

| Study | Key Method | System Tested | Key Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hadfield et al. (2022) [25] [26] | LBCS | Molecular Hamiltonians | Sizable variance reduction without increasing circuit depth |

| Nykänen et al. (2025) [27] | AIM-ADAPT-VQE (IC) | H$_4$ Hamiltonians | Eliminated measurement overhead for gradient estimation |

| Practical Techniques (2025) [3] | LBCS, IC, QDT, Blending | BODIPY-4 on IBM Eagle r3 | Reduced estimation error to 0.16%, near chemical precision |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing LBCS for Energy Estimation

This protocol details the steps to implement the Locally-Biased Classical Shadows method for estimating the energy of a molecular Hamiltonian.

Objective: Estimate ( \langle \psi | O | \psi \rangle ) for a given state ( \rho = |\psi\rangle\langle\psi| ) and Hamiltonian ( O = \sumQ \alphaQ Q ) with a minimized number of shots ( S ).

Required Reagents & Solutions: Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for LBCS

| Item | Function / Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Reference State | A classical approximation of ( | \psi\rangle ) (e.g., Hartree-Fock, MPS) used to optimize the bias distribution ( \beta ) [25] [26]. |

| Hamiltonian Decomposition | The target Hamiltonian ( O ) decomposed into its Pauli string representation ( \sum \alpha_Q Q ) [26]. | |

| Bias Optimization Routine | A classical algorithm (e.g., convex optimization) to solve for the variance-minimizing distributions ( \beta_i ) for each qubit [25] [26]. |

Procedure:

- Input Preparation:

- Obtain the Hamiltonian ( O = \sumQ \alphaQ Q ).

- Obtain a classical reference state ( \rho_{\text{ref}} ) (e.g., via Hartree-Fock calculation).

Bias Optimization:

- For each qubit ( i ), optimize the probability distribution ( \beta_i ) over {X, Y, Z}.

- The optimization aims to minimize the predicted variance of the estimator, ( \sum{Q,R} f(Q, R, \beta) \alphaQ \alphaR \text{tr}(\rho{\text{ref}} QR) ), which is convex in certain regimes [25] [26].

- The output is a set of optimized distributions ( \beta = {\beta_i} ).

Quantum Measurement and Estimation:

- For each shot ( s = 1 ) to ( S ):

- Prepare the quantum state ( \rho ).

- For each qubit ( i ), randomly select a measurement basis ( Pi \in {X, Y, Z} ) according to the optimized distribution ( \betai ).

- Measure all qubits, obtaining outcome ( \mu(P^{(s)}, i) \in {\pm 1} ) for each.

- On a classical computer, compute the estimate for each shot: [ \nu^{(s)} = \sum{Q} \alphaQ f(P^{(s)}, Q, \beta) \mu(P^{(s)}, \text{supp}(Q)) ]

- Compute the final estimate: ( \nu = \frac{1}{S} \sum_{s=1}^S \nu^{(s)} ).

- For each shot ( s = 1 ) to ( S ):

Protocol 2: Integrating IC Measurements with Error Mitigation

This protocol leverages Informationally Complete measurements and Quantum Detector Tomography to mitigate readout errors.

Objective: Estimate the energy and other observables from a single set of IC measurements while mitigating readout noise.

Required Reagents & Solutions: Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for IC Measurements

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Fixed IC Measurement Basis | A predetermined set of single-qubit gates (e.g., H, HS$^\dagger$) applied to all qubits to create an informationally complete POVM [27] [3]. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) Circuits | A set of circuits used to characterize the noisy measurement effects of the quantum device [3]. |

| Noise Mitigation Solver | A classical algorithm (e.g., least squares) that uses the QDT data to invert the effects of readout noise on the experimental IC data [3]. |

Procedure:

- Calibration - Quantum Detector Tomography:

- Execute a set of QDT circuits (e.g., all combinations of |0⟩ and |1⟩ state preparations) in parallel with the main experiment, using a blended scheduling strategy to average over time-dependent noise [3].

- Collect statistics to construct a matrix ( \Lambda ) that describes the probability of a noisy outcome given a perfect input state.

State Preparation and IC Measurement:

- Prepare the ansatz state ( |\psi(\theta)\rangle ).

- Apply the fixed set of basis rotation gates (e.g., H or HS$^\dagger$) to all qubits to rotate into the IC measurement basis.

- Measure all qubits in the computational basis. Repeat this step for ( T ) shots per setting to gather sufficient statistics.

Classical Post-Processing and Error Mitigation:

- Use the QDT matrix ( \Lambda ) to mitigate the readout errors in the collected IC data.

- Process the mitigated data to reconstruct an unbiased estimator for the quantum state's properties.

- From this reconstructed data, compute the expectation values for all terms ( \alpha_Q Q ) in the Hamiltonian ( O ), as well as for any other observables of interest (e.g., commutators for ADAPT-VQE) [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 5: Essential Research Tools and Methods

| Tool / Method | Function in Measurement Optimization |

|---|---|

| Matrix Product States (MPS) | A classical ansatz used for pre-training quantum circuit parameters and as a reference state for optimizing LBCS distributions ( \beta ) [4]. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | A calibration procedure used to characterize and subsequently mitigate readout errors on the quantum device, essential for high-precision results [3]. |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | An error mitigation technique that can be combined with neural networks to fit noisy data and extrapolate to the zero-noise limit [4]. |

| Blended Scheduling | An execution strategy that interleaves circuits from different experiments (e.g., main VQE, QDT) to average out the impact of time-dependent noise [3]. |

| Variance-Preserved Shot Reduction (VPSR) | A dynamic shot allocation strategy that minimizes the total number of measurement shots while preserving the variance of measurements during the VQE optimization [28]. |

| Pauli Grouping | A technique to group Hamiltonian terms into cliques of commuting Pauli strings that can be measured simultaneously, reducing the number of distinct circuit executions [4] [28]. |

| Aplindore Fumarate | Aplindore Fumarate|Dopamine D2 Receptor Agonist|RUO |

| Alphadolone | Alphadolone, CAS:14107-37-0, MF:C21H32O4, MW:348.5 g/mol |

Coefficient Splitting and Shifting Techniques for Redundant Hamiltonian Component Removal

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is a leading hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for finding ground state energies of molecular systems on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices [29]. A fundamental challenge impeding its practical application is sampling noise, which arises from the statistical uncertainty in estimating the energy expectation value through a finite number of measurements [7]. The molecular Hamiltonian, when mapped to qubits, becomes a weighted sum of numerous Pauli operators (Pauli strings). The need to measure each term individually, especially the non-commuting ones, creates a prohibitively large measurement overhead, often reaching thousands of measurement bases even for small molecules [7] [29].

This application note details two advanced measurement reduction strategies—Coefficient Splitting and Coefficient Shifting—framed within a broader thesis on mitigating sampling noise. These techniques function by strategically manipulating the Hamiltonian's coefficients to remove redundant components, thereby streamlining the measurement process without sacrificing the accuracy of the final energy calculation.

Theoretical Foundation

The VQE Framework and the Measurement Problem

In VQE, the goal is to find the parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) that minimize the energy expectation value ( E(\vec{\theta}) = \langle \psi(\vec{\theta}) | \hat{H} | \psi(\vec{\theta}) \rangle ), providing an upper bound to the true ground state energy [29]. The qubit Hamiltonian is expressed as: [ \hat{H} = \sum{i} ci \hat{P}i ] where ( ci ) are real coefficients and ( \hat{P}i ) are Pauli strings (tensor products of I, X, Y, Z operators) [30]. The energy estimation requires measuring the expectation value of each term ( \langle \hat{P}i \rangle ), which is computationally expensive for two primary reasons:

- Non-Commuting Terms: Pauli strings that do not commute cannot be measured simultaneously in the same basis, requiring separate circuit executions for each group of commuting operators [7].

- Numerous Terms: The number of Pauli terms in the Hamiltonian grows rapidly with molecular size, leading to a massive measurement budget that dominates computational time [7].

Defining Redundancy in the Hamiltonian

A redundant Hamiltonian component is a Pauli term ( \hat{P}k ) whose expectation value ( \langle \hat{P}k \rangle ) is either known a priori or can be inferred from the measurement of other terms, making its direct measurement unnecessary. Redundancy often arises from:

- Physical Symmetries: The system may conserve quantities like particle number or spin symmetry. An operator ( \hat{P}_k ) that commutes with a conserved symmetry operator ( \hat{S} ) (([\hat{H}, \hat{S}] = 0)) may have a fixed, known expectation value in the eigenbasis of ( \hat{S} ) [7].

- Algebraic Constraints: Certain Pauli operators may be related through algebraic identities (e.g., ( \hat{P}i \hat{P}j = \hat{P}_k )), allowing one expectation value to be derived from others.

The core principle of the techniques described herein is the identification and removal of these redundant terms to create a more efficient, reduced measurement schedule.

Core Methodologies

Coefficient Splitting Technique

The Coefficient Splitting technique is used when a redundant term ( \hat{P}k ) has a known, fixed expectation value ( Ck ) (e.g., from a symmetry argument). Instead of measuring ( \hat{P}_k ), we remove it from the Hamiltonian and redistribute its coefficient among other, non-redundant terms.

Protocol:

- Identify a Redundant Term: Select a Pauli term ( \hat{P}k ) with coefficient ( ck ) for which the expectation value is known to be a constant ( C_k ) in the relevant symmetry sector.

- Form the Reduced Hamiltonian: Remove ( \hat{P}k ) from the Hamiltonian. [ \hat{H}{reduced} = \hat{H} - ck \hat{P}k ]

- Split and Shift the Coefficient: The known energy contribution of the redundant term, ( ck Ck ), is a constant. This constant is added to the final energy, and the coefficient ( ck ) is strategically split and added to the coefficients of a subset of the remaining terms in ( \hat{H}{reduced} ). The splitting is designed to minimize the overall variance of the estimator.

- Construct the Effective Hamiltonian: The resulting Hamiltonian for measurement is: [ \hat{H}{effective} = \hat{H}{reduced} + \sum{i \in S} \Delta ci \hat{P}i ] where ( S ) is the selected subset of terms and ( \sum \Delta ci = 0 ) to keep the expectation value unchanged, as ( \langle \hat{H} \rangle = \langle \hat{H}{effective} \rangle + ck C_k ).

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Coefficient Splitting

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Remove redundant terms with known expectation values. |

| Prerequisite | A priori knowledge of ( \langle \hat{P}_k \rangle ). |

| Classical Overhead | Low (simple coefficient arithmetic). |

| Impact on Variance | Can be optimized to lower the overall energy estimator variance. |

Coefficient Shifting Technique

Coefficient Shifting is a constraint-based method used to enforce a known value for the expectation of an operator ( \hat{C} ) (e.g., particle number ( \hat{N} )) by adding a penalty term to the Hamiltonian. The "shifting" occurs when this constrained problem is reformulated into an unconstrained one on a modified Hamiltonian.

Protocol: