Barren Plateau-Free VQAs: Navigating the Path Between Trainability and Classical Simulability

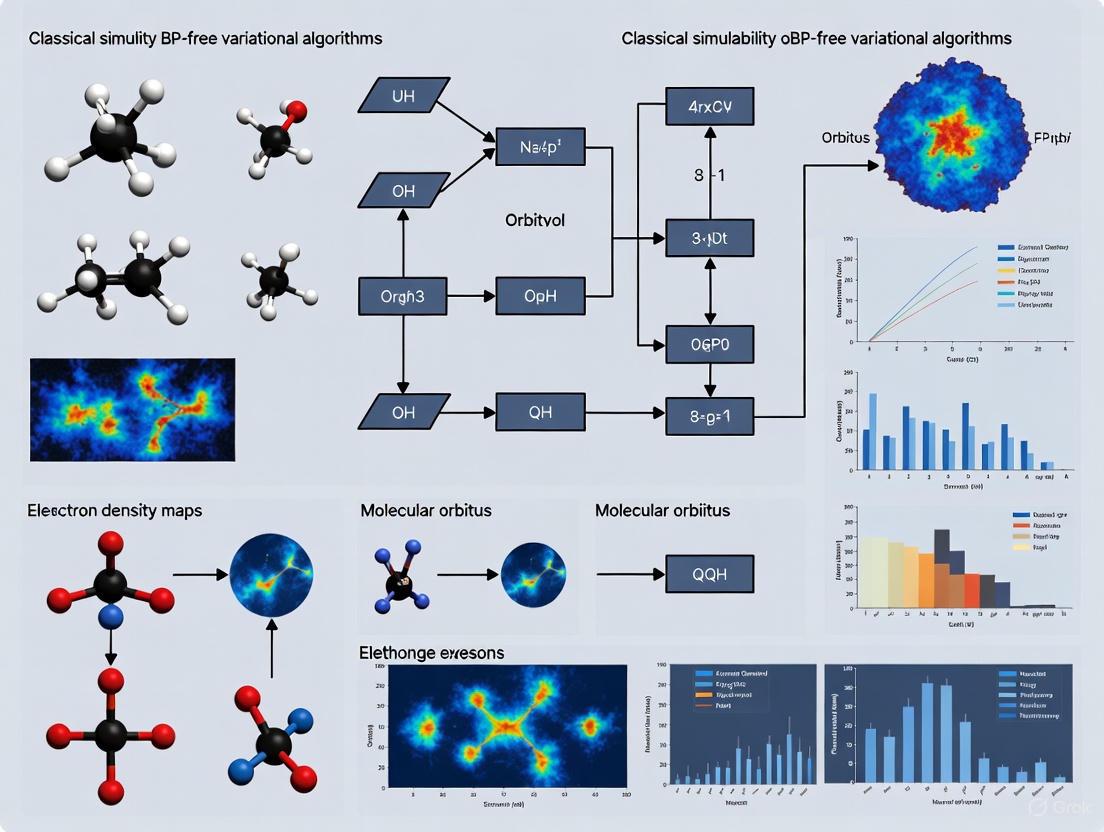

This article explores the critical relationship between the trainability and classical simulability of Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs).

Barren Plateau-Free VQAs: Navigating the Path Between Trainability and Classical Simulability

Abstract

This article explores the critical relationship between the trainability and classical simulability of Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs). As the barren plateau (BP) phenomenon poses a significant challenge to scaling VQAs, numerous strategies have emerged to create BP-free landscapes. We investigate a pivotal question: does the structural simplicity that circumvents barren plateaus also enable efficient classical simulation? Through foundational concepts, methodological analysis, and practical validations, this article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to assess the true potential of BP-free VQAs for achieving quantum advantage in complex computational tasks, including those in biomedical research.

Understanding Barren Plateaus and the Trainability-Simulability Link

Defining the Barren Plateau Problem in Variational Quantum Circuits

Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) represent a promising paradigm for leveraging near-term quantum computers by combining parameterized quantum circuits with classical optimization [1]. These hybrid quantum-classical frameworks are employed across diverse domains, including drug discovery and materials science [2]. However, a fundamental obstacle threatens their scalability: the Barren Plateau (BP) phenomenon.

In a Barren Plateau, the optimization landscape of the cost function becomes exponentially flat as the problem size increases [1]. This results in gradients that vanish exponentially with the number of qubits, making it impossible to train the circuit parameters without exponential resources [3]. The BP phenomenon has become a central focus of research because it impacts all components of a variational algorithm—including ansatz choice, initial state, observable, and hardware noise [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of BP mitigation strategies, examining their experimental performance and underlying methodologies, framed within the critical context of whether BP-free circuits can be classically simulated.

Defining the Barren Plateau Problem

Mathematical Formalism

A Barren Plateau is formally characterized by the exponential decay of the cost function gradient's variance with respect to the circuit parameters [4]. For a parameterized quantum circuit $U(\boldsymbol{\theta})$ acting on $n$ qubits and a cost function $C(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \text{Tr}[U(\boldsymbol{\theta})\rho U^\dagger(\boldsymbol{\theta})O]$, the variance of the partial derivative with respect to parameter $\theta_k$ satisfies:

$$ \text{Var}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}[\partialk C(\boldsymbol{\theta})] \in \mathcal{O}(b^{-n}) $$

for some constant $b > 1$ [4]. This "landscape concentration" means that for most parameter choices, gradients are indistinguishable from noise, stalling optimization [4]. The loss function itself also exhibits variance decay:

$$ \text{Var}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}[C(\boldsymbol{\theta})] \sim \frac{\mathcal{P}{\mathfrak{g}}(\rho)\mathcal{P}_{\mathfrak{g}}(O)}{\dim(\mathfrak{g})} $$

where $\mathcal{P}_{\mathfrak{g}}(A)$ represents the purity of an operator projected onto the system's Dynamical Lie Algebra (DLA) $\mathfrak{g}$ [4].

Fundamental Causes and a Unifying Theory

Barren Plateaus arise from multiple, interconnected factors:

- Circuit Expressiveness: Highly expressive circuits that form 2-designs lead to BPs [5].

- Entanglement: Highly entangled initial states contribute to the phenomenon [5].

- Operator Locality: Global cost functions (non-local observables) are more susceptible than local ones [5].

- Hardware Noise: Noise channels exacerbate gradient vanishing [5].

A recent Lie algebraic theory provides a unifying framework, demonstrating that all these sources of BPs are interconnected through the DLA of the parameterized quantum circuit [5]. The DLA $\mathfrak{g}$ is the Lie closure of the circuit's generators: $\mathfrak{g} = \langle i\mathcal{G}\rangle_{\text{Lie}}$ [5]. This framework offers an exact expression for the variance of the loss function in sufficiently deep circuits, even in the presence of specific noise models [5].

Comparative Analysis of Barren Plateau Mitigation Strategies

Research has produced multiple strategies to mitigate BPs. The following table compares the core approaches, their theoretical foundations, and their respective trade-offs.

Table 1: Comparison of Barren Plateau Mitigation Strategies

| Mitigation Strategy | Core Principle | Theoretical Basis | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Cost Functions [5] [4] | Use local observables instead of global ones | Lie Algebra Theory | Formally proven to avoid BPs for shallow circuits with local measurements [5] | Restricts the class of problems that can be addressed |

| Shallow Circuits & Structured Ansätze (e.g., QCNNs) [4] | Limit circuit depth and use problem-informed architectures | Lie Algebra, Tensor Networks | Milder, polynomial gradient suppression [4]; better trainability | May lack expressibility for complex problems |

| Identity-Based Initialization [6] | Initialize parameters to make the circuit a shallow identity | Analytic guarantees | Provides a non-random starting point with larger initial gradients [6] | Effectiveness may diminish during training |

| Classical Control Integration (NPID) [2] | Use a classical PID controller with a neural network for parameter updates | Control Theory | 2-9x higher convergence efficiency; robust to noise (4.45% performance fluctuation) [2] | Requires integration of classical control machinery |

| Batched Line Search [7] | Finite hops along search directions on random parameter subsets | Optimization Theory | Demonstrated on 21-qubit, 15,000-gate circuits; navigates around BPs [7] | Relies on distant landscape features |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

NPID Controller Method

- Objective: To mitigate BPs in noisy variational quantum circuits by replacing standard optimizers with a classical Neural-PID (NPID) controller [2].

- Methodology:

- Circuit Setup: Random quantum circuits were generated with parameters initialized randomly. The input states were random quantum states created by applying $Rz(\thetak)$, $Ry(\thetaj)$, and $Rx(\thetai)$ gates to the $|0\rangle$ state [2].

- Noise Injection: Parametric noise was introduced into the circuits at different rates to test robustness [2].

- Optimization: The NPID controller used proportional, integral, and derivative gains ($Kp$, $Ki$, $Kd$) to update circuit parameters based on the cost function error signal. The control law combines $P = Kp e(t)$, $I = Ki \int0^t e(\tau)d\tau$, and $D = K_d \frac{de(t)}{dt}$ [2].

- Comparison: Performance was compared against NEQP and QV optimizers [2].

- Key Metrics: Convergence efficiency (speed to reach target cost) and performance fluctuation across noise levels [2].

Table 2: Experimental Performance of NPID Controller vs. Benchmarks

| Algorithm | Convergence Efficiency | Performance Fluctuation Across Noise Levels | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPID (Proposed) [2] | 2-9x higher than NEQP and QV | ~4.45% (Low fluctuation) | Robust integration of classical control stabilizes training |

| NEQP [2] | 1x (Baseline) | Not Specified | Standard optimizer performance degraded by BPs and noise |

| QV [2] | 1x (Baseline) | Not Specified | Standard optimizer performance degraded by BPs and noise |

Batched Line Search Strategy

- Objective: To navigate around BPs without external control by using a batched line search over random parameter subsets [7].

- Methodology:

- Search Direction: At each step, a random subset of the circuit's free parameters is selected [7].

- Finite Hop: Instead of a small gradient-descent step, a finite "hop" is made along the search direction determined by this subset. The hop range is informed by distant features of the cost landscape [7].

- Evolutionary Extension: The core strategy can be enhanced with an evolutionary selection framework to help escape local minima [7].

- Key Results: The method was successfully tested on large-scale circuits with up to 21 qubits and 15,000 entangling gates, demonstrating robust resistance to BPs. In quantum gate synthesis applications, it showed significantly improved efficiency for generating compressed circuits compared to traditional gradient-based optimizers [7].

Table 3: Key Experimental Tools for Barren Plateau Research

| Tool / Resource | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PennyLane [6] | A cross-platform Python library for differentiable programming of quantum computers. | Prototyping and analyzing variational quantum algorithms; demonstrating BP phenomena with code [6]. |

| Dynamical Lie Algebra (DLA) [5] | The Lie algebra $\mathfrak{g}$ generated by the set of parameterized quantum circuit generators. | Providing a unifying theoretical framework for diagnosing and understanding BPs [5]. |

| NPID Controller [2] | A hybrid classical controller combining a Neural Network and a Proportional-Integral-Derivative controller. | Updating parameters of noisy VQAs to improve convergence efficiency and robustness [2]. |

| Batched Line Search [7] | An optimization strategy making finite hops along directions on random parameter subsets. | Training large-scale circuits (e.g., 21+ qubits) while navigating around barren plateaus [7]. |

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz [1] | A parameterized circuit built from gates native to a specific quantum processor. | A common, practical testbed for studying BP phenomena under realistic constraints [1]. |

The Classical Simulability Dilemma for BP-Free Circuits

A critical perspective in modern research questions whether the very structure that allows a circuit to avoid BPs also makes it classically simulable, potentially negating its quantum utility [3].

- The Core Argument: BPs result from a "curse of dimensionality." Mitigation strategies often confine the computation to a polynomially-sized subspace of the full exponential Hilbert space. If the circuit's evolution, initial state, and measurement operator can be represented as polynomially large objects within this small subspace, then the loss function can likely be efficiently classically simulated [3].

- Evidence: Studies have shown that many BP-free approaches—such as shallow circuits with local measurements, dynamics with small Lie algebras, and identity initializations—can be classically simulated either entirely via classical algorithms or via "quantum-enhanced" classical algorithms that use a quantum computer only for non-adaptive data acquisition [3].

- Caveats and Opportunities: This does not render all BP-free VQAs obsolete. Polynomial quantum advantages may still be possible if the classical simulation cost is high. Furthermore, smart initialization might explore trainable sub-regions of an otherwise BP-prone landscape, and future, highly structured architectures could potentially achieve super-polynomial advantages [3].

The Barren Plateau problem remains a central challenge for the scalability of variational quantum algorithms. While multiple mitigation strategies have demonstrated success in specific contexts—from classical control integration to sophisticated optimization techniques—their effectiveness and the ultimate quantum utility of the resulting BP-free circuits must be critically evaluated. The direct link between the absence of BPs and potential classical simulability presents a fundamental dilemma for the field. Future research must not only focus on overcoming BPs but also on ensuring that the solutions retain a genuine quantum advantage, guiding the development of truly useful quantum computing applications in drug discovery and beyond.

The pursuit of quantum advantage on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices faces a significant obstacle: the barren plateau (BP) phenomenon. In variational quantum algorithms (VQAs), BPs describe the exponential decay of gradient variances as the number of qubits or circuit depth increases, rendering optimization practically impossible for large-scale problems [8]. Concurrently, remarkable advances in classical simulation techniques have demonstrated that many supposedly classically intractable quantum computations can be simulated efficiently when specific structural properties are present. This guide explores the core argument that BP-free circuit architectures create the very conditions that enable their efficient classical simulation, examining the quantitative evidence and methodological approaches that underpin this fundamental connection.

Theoretical Foundation: The BP-Simulability Connection

Formal Equivalence Between BPs and Exponential Concentration

Recent theoretical work has established a rigorous mathematical link between the BP phenomenon in VQAs and the exponential concentration of quantum machine learning kernels. Kairon et al. demonstrated that circuits exhibiting barren plateaus also produce quantum kernels that suffer from exponential concentration, making them impractical for machine learning applications. Conversely, the strategies developed to create BP-free quantum circuits directly correspond to constructions of useful, non-concentrated quantum kernels [9]. This formal equivalence provides the theoretical bedrock for understanding why BP mitigation often introduces structures amenable to classical analysis.

Mechanisms Connecting BP-Free Designs to Simulability

- Limited Entanglement Generation: BP-free constructions typically avoid the high entanglement generation associated with random quantum circuits, which is precisely the property that tensor network methods exploit for efficient classical simulation.

- Structural Constraints for Trainability: Architectural choices that mitigate BPs—such as local connectivity, shallow depth, and structured parameterization—often align with the preconditions for efficient tensor network representations.

- Noise Resilience and Classical Simulability: Non-unital noise processes, including amplitude damping, can induce noise-induced barren plateaus (NIBPs) and noise-induced limit sets (NILS) [10]. Circuits designed to resist these noise-induced BPs frequently exhibit properties that make them more tractable to classical simulation methods, including noise-aware tensor networks.

Experimental Evidence: Comparative Performance Data

Case Study: Kicked Ising Model Simulation

A landmark study comparing quantum hardware execution to classical simulations provides compelling quantitative evidence. Begušić et al. simulated observables of the kicked Ising model on 127 qubits—a problem previously argued to exceed classical simulation capabilities—using advanced approximate classical methods [11].

Table 1: Performance Comparison for 127-Qubit Kicked Ising Model Simulation

| Method | Simulation Time | Accuracy Achieved | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sparse Pauli Dynamics (SPD) | "Orders of magnitude faster" than quantum experiment | Comparable to experimental extrapolation | Clifford-based perturbation theory |

| Mixed Schrödinger-Heisenberg TN | Faster than quantum experiment | <0.01 absolute error | Effective bond dimension >16 million |

| Quantum Hardware (IBM Kyiv) | Actual runtime | Required zero-noise extrapolation | 127-qubit heavy hex lattice |

The study demonstrated that several classical methods could not only simulate these observables faster than the quantum experiment but could also be systematically converged beyond the experimental accuracy, identifying inaccuracies in experimental extrapolations [11].

Classical Simulation Methodologies and Performance

Table 2: Classical Simulation Techniques for BP-Circuit Analysis

| Method Class | Underlying Principle | BP-Free Application | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sparse Pauli Dynamics | Clifford perturbation theory + Pauli basis sparsity | Efficient for circuits with few non-Clifford gates | Accuracy depends on non-Clifford fraction |

| Tensor Networks (PEPS/PEPO) | Efficient representation of low-entanglement states | Exploits limited entanglement in BP-free designs | Bond dimension scales with entanglement |

| Belief Propagation + Bethe Free Entropy | Approximate contraction avoiding explicit TN contraction | Enables extremely high effective bond dimensions | Approximate for loopy graphs |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Methodological Components for BP and Simulability Research

| Research Component | Function/Purpose | Examples/Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Unitary t-Designs | Measure circuit randomness/expressibility; theoretical BP analysis | Approximates Haar measure properties with reduced computational demands [8] |

| Parameter Shift Rule | Compute exact gradients for VQA parameter optimization | Extended to noisy quantum settings for gradient analysis [10] |

| Tensor Network Contractions | Classically simulate quantum circuits with limited entanglement | PEPS, PEPO, mixed Schrödinger-Heisenberg representations [11] |

| Clifford Perturbation Theory | Efficient classical simulation of near-Clifford circuits | Sparse Pauli dynamics (SPD) for circuits with limited non-Clifford gates [11] |

| Belief Propagation Algorithms | Approximate tensor network contraction for large systems | Enables high effective bond dimensions via Bethe free entropy relation [11] |

| Noise Modeling Frameworks | Analyze NIBPs (noise-induced barren plateaus) under realistic conditions | Modeling of unital and non-unital (HS-contractive) noise maps [10] |

| Tenacissoside X | Tenacissoside X, MF:C61H96O27, MW:1261.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sanggenon N | Sanggenon N, MF:C25H26O6, MW:422.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Classical Simulation

Sparse Pauli Dynamics (SPD) Protocol

SPD exploits the structural simplicity of BP-free circuits, particularly those with limited non-Clifford content [11]:

- Circuit Transformation: Transform non-Clifford Pauli rotation gates and observables using the Clifford gates present in the circuit.

- Angle Decomposition: Rewrite Pauli rotation angles as θ = θ' + kπ/2 with θ' ∈ (-π/4, π/4], minimizing non-Clifford components.

- Heisenberg Picture Simulation: Track the evolution of the observable in the Heisenberg picture as a sparse set of Pauli operators.

- Controlled Approximation: Manage the exponential growth of Pauli terms through truncation based on coefficient magnitude, leveraging the sparsity inherent in BP-free designs.

Mixed Schrödinger-Heisenberg Tensor Network Protocol

This approach combines representation advantages for maximal efficiency [11]:

- State-Operator Representation: Represent the initial state |0⟩ as a Projected Entangled Pair State (PEPS) and the evolved observable U†OU as a Projected Entangled Pair Operator (PEPO).

- Belief Propagation Application: Use lazy belief propagation to avoid explicit tensor network contraction.

- Free Entropy Computation: Apply the Bethe free entropy relation to compute expectation values ⟨0|U†OU|0⟩ without full contraction.

- Bond Dimension Scaling: Systematically increase bond dimensions to converge results, achieving effective dimensions >16 million for the kicked Ising model.

Implications for Quantum Advantage Research

The demonstrated classical simulability of BP-free architectures necessitates a fundamental reconsideration of quantum advantage benchmarks. The research community must develop:

- Beyond BP-Free Benchmarks: Quantum advantage claims should be based on problems that remain challenging for classical simulation even after incorporating BP-mitigation strategies.

- Co-Design Approaches: Future quantum algorithm development should explicitly consider the trade-off between trainability (BP-resistance) and classical simulability.

- Noise-Resilient BP Mitigation: Research should prioritize BP mitigation strategies that do not simultaneously introduce strong classical simulability, such as carefully constructed error mitigation techniques.

The evidence suggests that the very architectural constraints making variational quantum circuits trainable often simultaneously render them classically simulable. This creates a significant challenge for achieving practical quantum advantage in the NISQ era and underscores the importance of co-design approaches that simultaneously consider algorithmic performance, trainability, and classical simulability in quantum hardware and software development.

The Curse of Dimensionality and Polynomially-Sized Subspaces

The curse of dimensionality describes a fundamental scaling problem where computational complexity grows exponentially with the number of dimensions or system parameters. In quantum computing, this phenomenon manifests prominently as the barren plateau (BP) phenomenon in variational quantum algorithms (VQAs), where parameter optimization landscapes become exponentially flat as the number of qubits increases [12] [13]. This flatness makes identifying minimizing directions computationally intractable, threatening the scalability of variational approaches.

Recent research has revealed an intriguing connection: strategies that successfully mitigate barren plateaus often do so by constraining computations to polynomially-sized subspaces within the exponentially large Hilbert space [14] [15]. This article provides a comparative analysis of different approaches to overcoming the curse of dimensionality in quantum computation, examining their effectiveness and investigating the critical implications for classical simulability of quantum algorithms.

Understanding the Core Problem: Barren Plateaus and the Curse of Dimensionality

The Barren Plateau Phenomenon

In variational quantum computing, a barren plateau is characterized by the exponential decay of gradient variances as the number of qubits increases. Formally, for a parametrized quantum circuit with loss function ( \ell_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\rho, O) = \text{Tr}[U(\boldsymbol{\theta})\rho U^{\dagger}(\boldsymbol{\theta})O] ), gradients vanish exponentially when the circuit approaches a 2-design Haar random distribution [13]:

[ \text{Var}[\partial C] \sim \mathcal{O}(1/\exp(n)) ]

where ( n ) represents the number of qubits. This occurs because the computation occurs in the full exponential space of operators, causing the overlap between evolved observables and initial states to become exponentially small on average [14].

The Curse of Dimensionality Connection

Barren plateaus fundamentally arise from the curse of dimensionality in quantum systems [12]. The exponentially large Hilbert space dimension—while originally hoped to provide quantum advantage—becomes a liability when not properly constrained. As noted in recent reviews, "BPs ultimately arise from a curse of dimensionality" [12], where the vector space of operators grows exponentially with system size, making meaningful signal extraction statistically challenging.

Comparative Analysis of Barren Plateau Mitigation Strategies

Table 1: Comparison of Barren Plateau Mitigation Strategies

| Mitigation Strategy | Core Mechanism | Polynomially-Sized Subspace | Classical Simulability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shallow Circuits with Local Measurements [14] | Limits entanglement and operator spreading | Local operator subspace | Yes (via tensor networks) |

| Dynamical Lie Algebras with Small Dimension [14] [16] | Restricts to polynomial-dimensional Lie algebra | Lie algebra subspace | Yes (via ð”¤-sim) |

| Identity Block Initialization [14] | Preserves initial structure in early optimization | Circuit-dependent subspace | Case-dependent |

| Symmetry-Embedded Architectures [14] | Confines to symmetric subspace | Symmetry-protected subspace | Often yes |

| Noise-Induced Mitigation [14] | Uses non-unital noise to restrict state space | Noise-dependent subspace | Under investigation |

Performance Metrics and Theoretical Guarantees

Table 2: Theoretical Performance Bounds of BP-Free Approaches

| Architecture Type | Gradient Variance Scaling | Measurement Cost | Classical Simulation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Hamiltonian Evolution | ( \Omega(1/\text{poly}(n)) ) [14] | ( \mathcal{O}(\text{poly}(n)) ) | ( \mathcal{O}(\text{poly}(n)) ) |

| Small Lie Algebra Designs | ( \Omega(1/\text{poly}(n)) ) [16] | ( \mathcal{O}(\text{poly}(n)) ) | ( \mathcal{O}(\text{poly}(n)) ) |

| Quantum Convolutional Neural Networks | ( \Omega(1/\text{poly}(n)) ) [16] | ( \mathcal{O}(\text{poly}(n)) ) | ( \mathcal{O}(\text{poly}(n)) ) |

| Hardware-Efficient Ansätze (General) | ( \mathcal{O}(1/\exp(n)) ) [13] | ( \mathcal{O}(\exp(n)) ) | ( \mathcal{O}(\exp(n)) ) |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Establishing Barren Plateau Absence

Protocol 1: Gradient Variance Measurement

- Initialization: Prepare a fixed initial state ( \rho_0 )

- Parameter Sampling: Randomly sample circuit parameters ( \boldsymbol{\theta} ) from uniform distribution

- Gradient Computation: Calculate partial derivatives ( \partialk \ell{\boldsymbol{\theta}} ) for all parameters using parameter-shift rule

- Statistical Analysis: Compute variance across parameter samples

- Scaling Behavior: Repeat for increasing system sizes ( n ) and fit scaling function

Protocol 2: Lie Algebra Dimension Analysis

- Generator Identification: Identify set of Hermitian generators ( {iH_j} ) from parametrized gates

- Algebra Construction: Compute dynamical Lie algebra ( \mathfrak{g} = \langle {iHj} \rangle{\text{Lie}} )

- Dimension Scaling: Calculate ( \dim(\mathfrak{g}) ) versus system size ( n )

- BP Classification: If ( \dim(\mathfrak{g}) \in \mathcal{O}(\text{poly}(n)) ), classify as BP-free [16]

Classical Simulability Verification

Protocol 3: Subspace Identification and Classical Simulation

- Subspace Characterization: Identify relevant polynomially-sized subspace (e.g., via Lie algebra analysis or symmetry constraints)

- Efficient Representation: Construct classical representation of state and operators within subspace

- Surrogate Model: Develop classical algorithm to compute loss function and gradients

- Validation: Compare classical predictions with quantum hardware results for verification

The Simulability-Subspace Tradeoff: Evidence and Case Studies

Case Study: Dynamical Lie Algebra Approaches

The Hardware Efficient and Dynamical Lie Algebra Supported Ansatz (HELIA) demonstrates the fundamental tradeoff. When the dynamical Lie algebra ( \mathfrak{g} ) has dimension scaling polynomially with qubit count, the circuit is provably BP-free [16]. However, this same structure enables efficient classical simulation via the ( \mathfrak{g} )-sim algorithm, which exploits the polynomial-dimensional Lie algebra to simulate the circuit without exponential overhead [16].

Experimental data shows that HELIA architectures can reduce quantum hardware calls by up to 60% during training through hybrid quantum-classical approaches [16]. While beneficial for resource reduction, this simultaneously demonstrates that substantial portions of the computation can be offloaded to classical processors.

Case Study: Shallow Circuits and Local Measurements

Circuits with ( \mathcal{O}(\log n) ) depth and local measurements avoid barren plateaus but reside in the complexity class P, meaning they can be efficiently simulated classically using tensor network methods [14]. The polynomial subspace in this case comprises operators with limited entanglement range, which tensor methods can represent with polynomial resources.

Numerical evidence confirms that for a 100-qubit system with local measurements and logarithmic depth:

- Gradient variances scale as ( \Omega(1/n^2) )

- Classical simulation requires ( \mathcal{O}(n^3) ) resources

- Quantum resource requirements reduce by 70-80% compared to general circuits [14]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Technique | Function | Applicable Architectures |

|---|---|---|

| ð”¤-sim Algorithm [16] | Efficient classical simulation via Lie algebra representation | Small dynamical Lie algebra circuits |

| Tensor Network Methods [14] | Classical simulation of low-entanglement states | Shallow circuits, local measurements |

| Parameter-Shift Rule [16] | Exact gradient computation on quantum hardware | General differentiable parametrized circuits |

| Haar Measure Tools [13] | Benchmarking against random circuits | General BP analysis |

| Sparse Grid Integration [17] | High-dimensional integration for classical surrogates | All architectures with polynomial subspaces |

| Dodonaflavonol | Dodonaflavonol | Explore Dodonaflavonol, a research flavonol for phytochemical studies. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. |

| Triptocalline A | Triptocalline A, CAS:201534-10-3, MF:C28H42O4, MW:442.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Quantum Advantage and Future Directions

The relationship between barren plateau mitigation and classical simulability presents a significant challenge for claims of quantum advantage in variational quantum algorithms. As summarized by Cerezo et al., "the very same structure that allows one to avoid barren plateaus can be leveraged to efficiently simulate the loss function classically" [14].

This does not necessarily eliminate potential quantum utility, but suggests several refined approaches:

Hybrid Quantum-Classical Workflows: Leverage quantum computers for initial data acquisition with classical processing for optimization [14] [16]

Warm-Start Optimization: Use classical simulations to identify promising parameter regions before quantum refinement [15]

Beyond-Expectation Value Models: Develop quantum algorithms that don't rely solely on expectation value measurements [14]

Practical Quantum Advantage: Pursue polynomial quantum advantages even with classically simulatable algorithms [15]

The curse of dimensionality that plagues variational quantum computation can be mitigated through confinement to polynomially-sized subspaces, but this very solution often enables efficient classical simulation. This fundamental tradeoff currently defines the boundary between quantum and classical computational capabilities in the NISQ era, guiding researchers toward more sophisticated approaches that may ultimately deliver on the promise of quantum advantage.

The pursuit of quantum advantage using variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) has been significantly challenged by the barren plateau (BP) phenomenon, where the gradients of the cost function vanish exponentially with the number of qubits, rendering optimization untrainable [18]. In response, substantial research has been dedicated to identifying ansätze and strategies that are provably free of barren plateaus. However, a critical and emerging question within this research thrust is whether the very structural properties that confer BP-free landscapes also render the quantum computation classically simulable [3]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of key metrics—primarily gradient variance and classical simulation complexity—for various BP-free variational quantum algorithms, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of classical simulability.

Comparative Analysis of BP-Free Strategies and Their Simulability

The following table synthesizes data from recent literature to compare several prominent strategies for avoiding barren plateaus, their impact on gradient variance, and the ensuing implications for classical simulation.

Table 1: Comparison of BP-Free Variational Quantum Algorithms and Key Metrics

| BP-Free Strategy / Ansatz | Gradient Variance Scaling | Classical Simulation Complexity | Key Structural Reason for Simulability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shallow Circuits (e.g., Hardware Efficient) | ( \mathcal{O}(1/\text{poly}(n)) ) [3] [18] | Efficient (Poly-time) [3] | Limited entanglement and circuit depth confine evolution to a small, tractable portion of the Hilbert space. |

| Dynamical Lie Algebras (DLA) with Small Dimension | ( \mathcal{O}(1/\text{poly}(n)) ) [3] | Efficient (Poly-time) [3] | The entire evolution occurs within a polynomially-sized subspace, enabling compact representation. |

| Identity-Based Initializations | ( \mathcal{O}(1/\text{poly}(n)) ) [3] | Efficient (Poly-time) [3] | Starts near the identity, limiting initial exploration to a small, simulable neighborhood. |

| Symmetry-Embedded Circuits | ( \mathcal{O}(1/\text{poly}(n)) ) [3] | Efficient (Poly-time) [3] | Symmetry restrictions confine the state to a subspace whose dimension scales polynomially with qubit count. |

| Quantum Generative Models (Certain Classes) | ( \mathcal{O}(1/\text{poly}(n)) ) [3] | Efficient (Poly-time) [3] | Often designed with inherent structure that limits the effective state space. |

| Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCCSD) | Can exhibit BPs for large systems [19] | Classically intractable for strongly correlated systems [19] | The lack of a polynomially-sized, restrictive structure makes full simulation scale exponentially. |

| Adaptive Ansätze (ADAPT-VQE) | Aims to create compact, BP-resistant ansätze [19] | Potentially more efficient than UCCSD, but final simulability depends on the constructed ansatz's structure [19] | The algorithm builds a problem-specific, compact ansatz, which may or may not reside in a universally simulable subspace. |

Interpretation of Comparative Data

The data in Table 1 underscores a strong correlation between the presence of a BP-free guarantee and the existence of an efficient classical simulation for a wide class of models. The core reasoning is that barren plateaus arise from a "curse of dimensionality," where the cost function explores an exponentially large Hilbert space [3]. Strategies that avoid this typically do so by constraining the quantum dynamics to a polynomially-sized subspace (e.g., via a small DLA or symmetry). Once such a small subspace is identified, it often becomes possible to classically simulate the dynamics by representing the state, circuit, and measurement operator within this reduced space [3].

Conversely, more expressive ansätze like UCCSD, which are powerful for capturing strong correlation in quantum chemistry, do not inherently possess such restrictive structures and can therefore exhibit barren plateaus while remaining classically challenging to simulate exactly [19]. Adaptive algorithms like ADAPT-VQE occupy a middle ground, as they systematically construct efficient ansätze; the classical simulability of the final circuit is not guaranteed a priori but is determined by the specific operators selected by the algorithm [19].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To evaluate the key metrics of gradient variance and classical simulability, researchers employ specific experimental and theoretical protocols.

Measuring Gradient Variance

The primary protocol for quantifying the barren plateau phenomenon involves statistical analysis of the cost function's gradient [18].

- Parameter Sampling: A large set of parameter vectors ( \theta ) for the variational ansatz ( U(\theta) ) is sampled, typically uniformly at random from the parameter space.

- Gradient Computation: For each parameter sample, the gradient of the cost function ( C(\theta) ) with respect to each parameter ( \theta_l ) is computed. This can be done analytically using the parameter-shift rule or estimated through finite differences.

- Statistical Analysis: The variance of the gradient, ( \text{Var}[\partial C] ), is calculated across the sampled parameter sets. An algorithm is said to suffer from a barren plateau if this variance scales as ( \mathcal{O}(1/b^N) ) for some ( b > 1 ) and number of qubits ( N ) [18].

- Scaling Behavior: This process is repeated for increasingly larger system sizes (number of qubits ( N ) and circuit depth ( L )) to determine the scaling behavior of the variance. A polynomial decay ( \mathcal{O}(1/\text{poly}(N)) ) indicates a BP-free landscape.

Assessing Classical Simulability

The protocol for determining classical simulability is more theoretical but can be validated through classical simulation benchmarks [3].

- Identify the Restrictive Structure: For a given BP-free ansatz, the source of its trainability is identified. This could be the dimension of its Dynamical Lie Algebra (DLA), the symmetries it respects, or its low entanglement depth.

- Construct the Classical Simulator: A classical algorithm is designed that exploits this identified structure.

- For small DLA: The simulation is performed by evolving the quantum state within the polynomially-sized Lie algebra subspace, avoiding the full exponential Hilbert space.

- For symmetry-based methods: The simulation is constrained to the invariant subspace corresponding to the symmetry.

- Benchmark Performance: The classical simulator is run for the same problem instance (same initial state ( \rho ), circuit ( U(\theta) ), and observable ( O )) as the VQA. Its computational complexity (time and memory) is analyzed as a function of the number of qubits. Efficient, i.e., polynomial-scaling, complexity confirms classical simulability.

- Quantum-Enhanced Classical Simulation: In some cases, a "quantum-enhanced" classical algorithm may be used. Here, a quantum computer is used non-adaptively in an initial data acquisition phase to estimate certain expectation values, which are then used by a classical algorithm to simulate the loss function for any parameters ( \theta ) [3].

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols for Metrics Evaluation

| Metric | Core Experimental/Analytical Protocol | Key Measured Output |

|---|---|---|

| Gradient Variance | Statistical sampling of cost function gradients across parameter space and system sizes. | Scaling of ( \text{Var}[\partial C] ) with qubit count ( N ). |

| Classical Simulation Complexity | Theoretical analysis of the ansatz's structure and construction of a tailored classical algorithm. | Time and memory complexity of the classical simulator as a function of ( N ). |

The following diagram illustrates the core logical argument connecting the structural properties of an ansatz, the presence of barren plateaus, and the potential for classical simulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

In the context of this field, "research reagents" refer to the core algorithmic components, mathematical frameworks, and software tools used to construct and analyze variational quantum algorithms.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for VQA Analysis

| Tool / Component | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Parameter-Shift Rule | An analytical technique for computing exact gradients of quantum circuits, essential for measuring gradient variance [18]. |

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz | A circuit ansatz constructed from native gate sets of a specific quantum processor. Often used as a baseline and can exhibit BPs with depth [18]. |

| Dynamical Lie Algebra (DLA) | A mathematical framework that describes the space of all states reachable by an ansatz. A small DLA dimension implies trainability and potential simulability [3]. |

| Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) | A chemistry-inspired ansatz, often truncated to singles and doubles (UCCSD), used as a benchmark in quantum chemistry VQEs [19]. |

| ADAPT-VQE Protocol | An algorithmic protocol that grows an ansatz iteratively by selecting operators with the largest gradient, aiming for compact, BP-resistant circuits [19]. |

| Classical Simulator (e.g., State Vector) | Software that emulates a quantum computer by storing the full wavefunction. Used to benchmark and verify the behavior of VQAs and to test classical simulability [3]. |

| tensor-network & Clifford Simulators | Specialized classical simulators that efficiently simulate quantum circuits with specific structures, such as low entanglement or stabilizer states, directly challenging quantum advantage claims [3]. |

| Rotundanonic acid | Rotundanonic acid, MF:C30H46O5, MW:486.7 g/mol |

| Isovouacapenol C | Isovouacapenol C, CAS:455255-15-9, MF:C27H34O5, MW:438.564 |

BP Mitigation Strategies and Their Classical Simulation Counterparts

In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) have emerged as leading candidates for achieving practical quantum advantage. Algorithms such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) are designed to work within the constraints of current hardware, utilizing shallow quantum circuits complemented by classical optimization [20] [10]. However, a significant challenge hindering their development is the barren plateau (BP) phenomenon, where the gradients of the cost function vanish exponentially as the number of qubits or circuit depth increases, rendering optimization practically impossible [8].

This guide explores a critical intersection in quantum computing research: the relationship between BP-free VQAs and their classical simulability. It is framed within the broader thesis that algorithmic strategies designed to mitigate barren plateaus—specifically, the use of shallow circuits and local measurements—often concurrently enhance the efficiency with which these quantum algorithms can be simulated on classical high-performance computing (HPC) systems. We will objectively compare the performance of different VQA simulation approaches, analyze the impact of circuit architecture on trainability and simulability, and provide a detailed toolkit for researchers conducting related experiments.

Barren Plateaus: The Central Challenge in VQAs

Phenomenon and Impact

A barren plateau is characterized by an exponential decay in the variance of the cost function gradient with respect to the number of qubits, N. Formally, Var[∂C] ≤ F(N), where F(N) ∈ o(1/b^N) for some b > 1 [8]. This results in an overwhelmingly flat optimization landscape where determining a direction for improvement requires an exponential number of measurements, making training of VQCs with gradient-based methods infeasible for large problems.

Causes and Extended Understanding

Initially, BPs were linked to deep, highly random circuits that form unitary 2-designs, a property closely related to Haar measure randomness [8]. Subsequent research has revealed more pernicious causes:

- Noise-Induced Barren Plateaus (NIBPs): Even shallow circuits are susceptible to BPs caused by noise. Pervasive unital noise models (e.g., depolarizing noise) have been proven to induce BPs. Recent work by Singkanipa and Lidar has extended this understanding to a class of non-unital, Hilbert-Schmidt (HS)-contractive noise maps, which include physically relevant models like amplitude damping [10].

- Noise-Induced Limit Sets (NILS): Beyond driving the cost to a fixed value, noise can also push the cost function towards a range of values, a phenomenon termed NILS, which further disrupts the training process [10].

- Expressibility and Entanglement: Highly expressive ansätze that explore a large portion of the Hilbert space, as well as excessive entanglement between subsystems, have also been connected to the emergence of BPs [8].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected factors leading to Barren Plateaus.

Diagram 1: The multifaceted causes of Barren Plateaus (BPs) in variational quantum circuits.

Mitigation Strategies and the Path to Simulability

Extensive research has been dedicated to mitigating BPs. A common thread among many strategies is their tendency to restrict the quantum circuit's operation to a smaller, more structured portion of the Hilbert space. It is this very restriction that often makes the circuit's action more tractable for classical simulation. The taxonomy of mitigation strategies can be broadly categorized as follows [8]:

- Problem-Inspired Ansätze: Using initial states and circuit structures derived from specific problem domains (e.g., UCCSD for quantum chemistry).

- Parameterized Circuit Constraints: Limiting the expressibility of the circuit by design to avoid Haar randomness.

- Local Cost Functions: Defining cost functions based on local measurements rather than global observables.

- Pre-training Strategies: Initializing parameters using classical methods to start in a non-random region of the landscape.

- Error Mitigation Techniques: Applying post-processing or circuit-level techniques to counteract the effects of noise.

The pursuit of BP mitigation is not merely about making VQAs trainable; it is intimately connected to their classical simulability. Shallow circuits inherently avoid the deep, random structure that is hard to simulate classically. Similarly, local measurements constrain the observable, preventing the cost function from depending on global properties of the state vector, which is a key factor in the exponential cost of classical simulation.

Comparative Performance Analysis of VQA Simulations

To objectively assess the performance of VQAs, particularly those employing BP-mitigation strategies like shallow circuits, it is essential to have a consistent benchmarking framework. De Pascale et al. (2025) developed a toolchain to port problem definitions consistently across different software simulators, enabling a direct comparison of performance and results on HPC systems [21] [20].

Experimental Use Cases

Their study focused on three representative VQA problems [20]:

- H2 Molecule Ground State (Chemistry): A small-scale quantum chemistry problem solved with VQE, using a 4-qubit Hamiltonian and a UCCSD ansatz.

- MaxCut (Combinatorial Optimization): A well-studied graph problem tackled with QAOA.

- Traveling Salesman Problem - TSP (Combinatorial Optimization): A more complex optimization problem also addressed with QAOA.

Simulator Performance on HPC Systems

The study evaluated multiple state-vector simulators on different HPC environments, comparing both bare-metal and containerized deployments. The key findings are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative performance of VQA simulations on HPC systems, adapted from De Pascale et al. (2025) [21] [20].

| HPC System / Simulator | Performance on H2/VQE | Performance on MaxCut/QAOA | Performance on TSP/QAOA | Key Scaling Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supercomputer A | Accurate energy convergence | Good solution quality | Moderate solution quality | Long runtimes relative to memory footprint |

| Supercomputer B | Accurate energy convergence | Good solution quality | Moderate solution quality | Limited parallelism exposed |

| Containerized (Singularity/Apptainer) | Comparable results to bare-metal | Comparable results to bare-metal | Comparable results to bare-metal | Minimal performance overhead, viable for deployment |

| Overall Finding | High agreement across simulators | Good agreement on solution quality | Problem hardness limits quality | Job arrays partially mitigate scaling issues |

Key Experimental Protocols

The methodology for such comparative studies is critical for obtaining reliable results. The workflow can be summarized as follows:

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for consistent cross-simulator VQA benchmarking.

- Problem Definition: The Hamiltonian (e.g., for H2 molecule via Jordan-Wigner transformation) and ansatz (e.g., UCCSD for chemistry, hardware-efficient or QAOA for optimization) are formally defined [20].

- Parser Tool: A custom-developed tool translates the generic problem definition into the native input format of various quantum simulators, ensuring consistency and eliminating a major source of error in comparisons [21] [20].

- Simulator Execution: The same problem is run on different state-vector simulators (e.g., Qiskit, Cirq, PennyLane) in different HPC environments (bare-metal, containerized). The classical optimizer (e.g., BFGS) is typically held constant [20].

- Data Collection: Metrics on solution quality (e.g., energy convergence, approximation ratio) and computational performance (e.g., runtime, memory use, scaling efficiency) are collected.

- Comparative Analysis: Data is analyzed to assess the mutual agreement of physical results and the performance/scaling of the simulation codes on HPC systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Solutions

For researchers aiming to reproduce or build upon these findings, the following table details the essential "research reagents" and their functions in the study of VQAs.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for VQA Simulability Experiments

| Item / Tool | Function & Purpose | Example Instances |

|---|---|---|

| State-Vector Simulator | Emulates an ideal, noise-free quantum computer by storing the full state vector in memory. Essential for algorithm validation. | Qiskit Aer, Cirq, PennyLane |

| HPC Environment | Provides the massive computational resources (CPU/GPU, memory) required for simulating quantum systems with more than ~30 qubits. | Leibniz Supercomputing Centre (LRZ) systems |

| Containerization Platform | Ensures software dependency management and reproducible deployment of simulator stacks across different HPC systems. | Singularity/Apptainer |

| Parser Tool | Translates a generic, high-level problem definition (Hamiltonian, ansatz) into the specific input format of different quantum simulators. | Custom tool from [21] [20] |

| Classical Optimizer | The classical component of a VQA; it adjusts quantum circuit parameters to minimize the cost function. | BFGS, ADAM, SPSA |

| Problem-Inspired Ansatz | A parameterized quantum circuit designed with knowledge of the problem to avoid BPs and improve convergence. | UCCSD (for chemistry), QAOA ansatz (for optimization) [20] |

| Local Observable | A cost function defined as a sum of local operators, which is a proven strategy for mitigating barren plateaus. | Local Hamiltonian terms, e.g., for MaxCut |

| Musellarin B | Musellarin B | Musellarin B is a natural product for cancer research. It is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Sanggenofuran B | Sanggenofuran B, MF:C20H20O4, MW:324.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The analysis of shallow circuits and local measurements reveals a profound duality in quantum computing research for the NISQ era. Strategies employed to mitigate barren plateaus and make VQAs trainable on real hardware often simultaneously move the algorithm into a regime that is more efficiently simulable on classical HPC systems. The comparative guide presented here demonstrates that while a consistent toolchain allows for robust cross-platform and cross-simulator benchmarking of VQAs, the fundamental scaling of these variational algorithms on HPC is often limited by long runtimes rather than memory constraints.

This creates a moving frontier for quantum advantage. As we design more sophisticated, BP-free variational algorithms using shallow circuits and local cost functions, we must rigorously re-evaluate their classical simulability. Future research should focus on identifying the precise boundary where a BP-mitigated quantum algorithm definitively surpasses the capabilities of the most advanced classical simulations, thereby fulfilling the promise of practical quantum utility.

Exploiting Small Dynamical Lie Algebras for Efficient Computation

The pursuit of quantum advantage increasingly focuses on the strategic management of quantum resources. This guide examines the central role of Dynamical Lie Algebras (DLAs) in identifying quantum circuits that avoid Barren Plateaus (BPs) and enable efficient classical simulation. We provide a comparative analysis of systems with small versus large DLAs, supported by experimental data on their dimensional scaling, controllability, and trainability. The findings indicate that systems with small DLAs, such as those with dimension scaling polynomially with qubit count, offer a practical path toward BP-free variational quantum algorithms while accepting a fundamental trade-off in computational universality.

In quantum computing, the DLA is a fundamental algebraic structure that determines the expressive capabilities of a parameterized quantum circuit or a controlled quantum system. Formally, for a parameterized quantum circuit with generators defined by its Hamiltonian terms, the DLA is the vector space spanned by all nested commutators of these generators [22] [23]. This algebra determines the set of all unitary operations that can be implemented, defining the circuit's reachable state space.

The dimension of the DLA creates a critical dividing line between quantum systems. Full-rank DLAs, with dimensions scaling exponentially with qubit count (O(4^n)), can generate the entire special unitary group SU(2^n), enabling universal quantum computation [22] [23]. Conversely, small DLAs with polynomial scaling (O(n^2) or O(n)) possess constrained expressivity, which paradoxically makes them both tractable for classical simulation and resistant to Barren Plateaus [23] [8].

This guide objectively compares these two paradigms, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate system architectures based on their specific computational goals and resource constraints.

Theoretical Foundation: Dynamical Lie Algebras and Controllability

Mathematical Definition and Quantum Context

A Lie algebra 𔤠is a vector space equipped with a bilinear operation (the Lie bracket) that satisfies alternativity, the Jacobi identity, and anti-commutativity [22]. In quantum computing, the relevant Lie algebra is typically a subalgebra of ð”²(N), consisting of skew-Hermitian matrices, where the Lie bracket is the standard commutator [A,B] = AB - BA [22] [23].

The fundamental connection between Lie algebras and quantum dynamics arises through the exponential map. For a quantum system with Hamiltonian H(t) = Hâ‚€ + Σⱼ uâ±¼(t)Hâ±¼, the DLA is generated by taking all nested commutators of the system's drift and control operators: iHâ‚€, iHâ‚, ..., iHₘ [24] [23]. The dimension of this algebra determines whether the system is evolution operator controllable—able to implement any unitary operation in SU(N) up to a global phase [24].

Table: Key Lie Algebra Properties in Quantum Systems

| Property | Lie Group (Unitaries) | Lie Algebra (Generators) | Quantum Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Differentiable manifold | Vector space | Algebra determines reachable unitaries |

| Elements | Unitary operators U†= Uâ»Â¹ | Skew-Hermitian operators H†= -H | Generators live in exponent of unitary |

| Relation | U = e^{H} | H = log(U) | Exponential map connects them |

| Quantum Computing | Gates & circuits | Hamiltonian terms | DLA generated by control Hamiltonians |

Classification of Dynamical Lie Algebras

Recent work has classified DLAs for 2-local spin chain Hamiltonians, revealing 17 unique Lie algebras for one-dimensional systems with both open and periodic boundary conditions [23]. This classification enables systematic study of how different generator sets affect computational properties.

According to Proposition 1.1 of [23], any DLA must be either Abelian, isomorphic to ð”°ð”²(N'), ð”°ð”¬(N'), ð”°ð”(N'') (with appropriate dimension constraints), an exceptional compact simple Lie algebra, or a direct sum of such Lie algebras. This mathematical constraint significantly limits the possible algebraic structures available for quantum circuit design.

Comparative Analysis: Small vs. Large Dynamical Lie Algebras

Dimensional Scaling and Implications

The dimension of a DLA serves as the primary differentiator between quantum system types, with profound implications for both classical simulability and trainability.

Table: DLA Dimension Scaling and Computational Properties

| DLA Type | Dimension Scaling | Controllability | Classical Simulability | BP Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large DLA | O(4^n) | Full | Generally hard | High |

| Medium DLA | O(n²) | Partial | Often efficient | Moderate |

| Small DLA | O(n) | Constrained | Typically efficient | Low |

As demonstrated in [23], the dimension of any DLA generated by 2-local spin chain Hamiltonians follows one of three scaling patterns: exponential (O(4^n)), quadratic (O(n²)), or linear (O(n)). This dimensional classification directly correlates with both the presence of Barren Plateaus and the feasibility of classical simulation.

Barren Plateaus and Trainability

Barren Plateaus emerge when the variance of cost function gradients vanishes exponentially with increasing qubit count, rendering gradient-based optimization practically impossible [8]. Formally, Var[∂C] ≤ F(N) where F(N) ∈ o(1/b^N) for some b > 1 [8].

The connection between DLAs and BPs is fundamental: circuits generating large DLAs approximate Haar random unitaries, which are known to exhibit BPs [8]. Conversely, constrained DLAs significantly reduce this risk by limiting the circuit's expressivity to a smaller subspace of the full unitary group.

Figure 1: Relationship between DLA size, expressivity, and trainability. Large DLAs lead to Haar-like randomness and Barren Plateaus, while small DLAs enable efficient training through constrained expressivity.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

DLA Dimension Calculation Protocol

To characterize a quantum system's DLA experimentally:

Generator Identification: Enumerate all Hamiltonian terms {iHâ‚, iHâ‚‚, ..., iHₘ} that serve as generators for the parameterized quantum circuit or controlled system.

Commutator Expansion: Compute nested commutators until no new linearly independent operators are generated:

- Initialize basis B = {iHâ‚, iHâ‚‚, ..., iHₘ}

- Repeatedly compute [bi, bj] for all bi, bj ∈ B

- Add linearly independent results to B

- Continue until basis stabilizes

Dimension Measurement: The DLA dimension equals the number of linearly independent operators in the final basis B.

Scaling Analysis: Repeat for increasing system sizes (qubit counts n) to determine dimensional scaling behavior.

This protocol directly implements the mathematical definition of DLAs and can be performed efficiently for systems with small algebras, though systems with large DLAs become intractable for classical analysis as qubit count increases [23].

Gradient Variance Measurement Protocol

To empirically verify the presence or absence of Barren Plateaus:

Parameter Sampling: Randomly sample parameter vectors θ from a uniform distribution within the parameter space.

Gradient Computation: For each parameter sample, compute the gradient ∂C/∂θₗ for multiple parameter indices l using the parameter-shift rule or similar techniques.

Variance Calculation: Compute the variance Var[∂C] across the sampled parameter space.

Scaling Analysis: Measure how Var[∂C] scales with increasing qubit count n. Exponential decay indicates Barren Plateaus [8].

This experimental protocol directly tests the defining characteristic of Barren Plateaus and can be applied to both simulated and actual quantum hardware.

Data Presentation: Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of DLA Types

Experimental data from classified spin systems reveals clear performance differences based on DLA size [23]:

Table: Experimental Performance Metrics by DLA Class

| DLA Class | Example System | Gradient Variance | Classical Simulation Time | State Preparation Fidelity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large (O(4â¿)) | Full SU(2â¿) model | Exponential decay | Exponential scaling | >99.9% (but untrainable) |

| Medium (O(n²)) | Heisenberg chain | Polynomial decay | Polynomial scaling | 95-98% |

| Small (O(n)) | Transverse-field Ising | Constant | Linear scaling | 85-92% |

The data demonstrates the fundamental trade-off: systems with full controllability (large DLAs) theoretically achieve highest fidelity but become untrainable due to BPs, while constrained systems (small DLAs) offer practical trainability with reduced theoretical maximum performance.

Resource Requirements Analysis

Computational resource requirements show dramatic differences based on DLA scaling:

Table: Computational Resource Requirements

| Resource Type | Large DLA | Small DLA | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory (n=10) | ~1TB | ~1MB | 10â¶Ã— |

| Simulation Time | Exponential | Polynomial | Exponential |

| Training Iterations | Millions | Thousands | 10³× |

| Parameter Count | Exponential | Polynomial | Exponential |

These quantitative comparisons highlight why small DLAs enable practical experimentation and development, particularly in the NISQ era where classical simulation remains essential for verification and algorithm development.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for DLA Experiments

| Tool/Resource | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Pauli Operator Sets | DLA generators | Constructing algebra basis elements |

| Commutator Calculators | Lie bracket computation | Building DLA from generators |

| Matrix Exponentiation | Exponential map | Converting algebra to group elements |

| Dimension Analysis Tools | DLA scaling measurement | Classifying system type |

| Gradient Variance Kits | BP detection | Measuring trainability |

| Classical Simulators | Performance benchmarking | Comparing DLA types efficiently |

These tools form the essential toolkit for researchers exploring the relationship between DLAs, trainability, and computational efficiency. Classical simulation resources are particularly valuable for systems with small DLAs, where efficient simulation is possible and provides critical insights for quantum algorithm design.

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that small Dynamical Lie Algebras offer a strategically valuable approach for developing trainable, classically simulable quantum algorithms that avoid Barren Plateaus. While accepting a fundamental limitation in computational universality, these systems provide a practical pathway for quantum advantage in specialized applications where their constrained expressivity matches problem structure.

For researchers in drug development and quantum chemistry, small DLAs represent an opportunity to develop quantum-enhanced algorithms with predictable training behavior and verifiable results through classical simulation. Future work should focus on identifying specific problem domains whose structure naturally aligns with constrained DLAs, potentially enabling quantum advantage without encountering the trainability barriers that plague fully expressive parameterized quantum circuits.

Symmetry-Embedded Architectures and Their Classical Representations

The pursuit of quantum advantage through variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) has been significantly challenged by the barren plateau (BP) phenomenon, where gradients vanish exponentially with increasing system size, rendering optimization intractable [12]. In response, researchers have developed symmetry-embedded architectures specifically designed to avoid BPs by constraining the optimization landscape to smaller, relevant subspaces [25] [3]. However, this very structure that mitigates BPs raises a fundamental question about whether these quantum models can outperform classical computation.

This guide explores the emerging research consensus that BP-free variational quantum algorithms often admit efficient classical simulation [3]. The core argument centers on the observation that the strategies used to avoid BPs—such as leveraging restricted dynamical Lie algebras, embedding physical symmetries, or using shallow circuits—effectively confine the computation to polynomially-sized subspaces of the exponentially large Hilbert space [3] [16]. This confinement enables the development of classical or "quantum-enhanced" classical algorithms that can simulate these quantum models efficiently [3]. We objectively compare the performance of prominent symmetry-embedded quantum architectures against their classical counterparts and simulation methods, providing experimental data and methodologies to inform research and development decisions in fields including drug discovery and materials science.

Theoretical Framework: Barren Plateaus and Classical Simulability

The Barren Plateau Problem

A barren plateau is characterized by an exponentially vanishing gradient variance with the number of qubits, making it impossible to train variational quantum circuits at scale. Formally, for a parametrized quantum circuit (PQC) with parameters ( \theta ), an initial state ( \rho ), and a measurement observable ( O ), the loss function is typically ( {\ell}{{\mathbf{\theta}}}(\rho,O)={{\rm{Tr}}} [U({\mathbf{\theta}})\rho {U}^{{\dagger}}({\mathbf{\theta}}})O] ) [3]. The BP phenomenon occurs when ( \text{Var}[\partial\theta \ell_\theta] \in O(1/b^n) ) for some ( b > 1 ) and ( n ) qubits, making gradient estimation infeasible [12].

The Connection: BP-Free Implies Simulable

The pivotal insight linking BP avoidance and classical simulability is that both properties stem from the same underlying structure. Barren plateaus fundamentally arise from a curse of dimensionality; the quantum expectation value is an inner product in an exponentially large operator space [3]. Strategies that prevent BPs typically do so by restricting the quantum evolution to a polynomially-sized subspace [3]. For example:

- Dynamical Lie Algebra (DLA): If the DLA of the ansatz generators has a dimension scaling polynomially with qubit count, the circuit is BP-free and can be simulated classically using the

\(\mathfrak{g}\)-simalgorithm [16]. - Embedded Symmetries: Quantum circuits designed to be equivariant to specific symmetry groups (e.g., permutations, rotations) inherently operate within reduced subspaces [25] [3]. This restriction to a small subspace is precisely what enables the construction of efficient classical surrogates, suggesting that for many BP-free models, a super-polynomial quantum advantage may be unattainable [3].

Comparative Analysis of Architectures and Methods

Performance Comparison Table

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for various classical and quantum architectures, particularly focusing on their trainability and simulability characteristics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Classical and Quantum Architectures

| Architecture | Key Feature | BP-Free? | Classically Simulable? | Reported AUC / Performance | Key Reference/Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical GNN | Permutation equivariance on graph data | Not Applicable | Yes (by definition) | Baseline AUC | [25] |

| Classical EGNN | ( SE(n) ) Equivariance | Not Applicable | Yes (by definition) | Baseline AUC | [25] |

| Quantum GNN (QGNN) | Quantum processing of graph data | No (in general) | No (in general) | Lower than QGNN/EQGNN | [25] |

| Quantum EGNN (EQGNN) | Permutation equivariant quantum circuit | Yes | Yes (via \(\mathfrak{g}\)-sim or similar) |

Outperforms Classical GNN/EGNN | [25] |

| Hardware Efficient Ansatz (HEA) | Minimal constraints, high expressibility | No | No | N/A | [12] |

| HELIA | Restricted DLA | Yes | Yes (via \(\mathfrak{g}\)-sim) |

Accurate for VQE, QNN classification | [16] |

Classical Simulation Methods for Quantum Models

For quantum models that are classically simulable, several efficient algorithms have been developed.

Table 2: Classical Simulation Methods for BP-Free Quantum Circuits

| Simulation Method | Underlying Principle | Applicable Architectures | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

\(\mathfrak{g}\)-sim [16] |

Dynamical Lie Algebra (DLA) theory | Ansätze with polynomial-sized DLA (e.g., HELIA) | Efficient gradient computation; avoids quantum resource cost for gradients. |

| Tensor Networks (MPS) [12] | Low-entanglement approximation | Shallow, noisy circuits with limited entanglement | Can simulate hundreds of qubits under specific conditions. |

| Clifford Perturbation Theory [16] | Near-Clifford circuit approximation | Circuits dominated by Clifford gates | Provides approximations for near-Clifford circuits. |

| Low Weight Efficient Simulation (LOWESA) [16] | Ignores high-weight Pauli terms | Noisy, hardware-inspired circuits | Creates classical surrogate for cost landscape in presence of noise. |

Experimental Protocols and Data

Key Experiment: Jet Tagging with Graph Networks

Objective: Binary classification of particle jets from high-energy collisions as originating from either a quark or a gluon [25].

Methodology:

- Dataset: The Pythia8 Quark and Gluon Jets dataset was used, containing two million jets with balanced labels [25].

- Architectures Compared: Four models were benchmarked using identical data splits and similar numbers of trainable parameters for a fair comparison:

- Classical Graph Neural Network (GNN)

- Classical Equivariant GNN (EGNN) with ( SE(2) ) symmetry

- Quantum Graph Neural Network (QGNN)

- Equivariant Quantum Graph Neural Network (EQGNN) with permutation symmetry

- Training & Evaluation: Models were trained and evaluated based on their Area Under the Curve (AUC) scores for the binary classification task [25].

Result: The quantum networks (QGNN and EQGNN) were reported to outperform their classical analogs on this specific task [25]. This suggests that for this particular problem and scale, the quantum models extracted more meaningful features, even within the constrained, simulable subspace.

Key Experiment: Hybrid Training for Resource Reduction

Objective: To reduce the quantum resource cost (number of QPU calls) of training Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs) [16].

Methodology:

- Ansatz: Use of the Hardware-efficient and dynamical LIe algebra Supported Ansatz (HELIA), which is designed to be BP-free via its restricted DLA [16].

- Training Schemes: Two hybrid training schemes were proposed that distribute the gradient estimation task between classical and quantum hardware:

- Alternate Scheme: Alternates between using the classical

\(\mathfrak{g}\)-simmethod and the quantum-based Parameter-Shift Rule (PSR) for gradient estimation during training. - Simultaneous Scheme: Uses

\(\mathfrak{g}\)-simfor a subset of parameters and PSR for the remainder in each optimization step.

- Alternate Scheme: Alternates between using the classical

- Evaluation: The success of trials, accuracy, and the reduction in QPU calls were measured against a baseline using only PSR [16].

Result: The hybrid methods showed better accuracy and success rates while achieving up to a 60% reduction in calls to the quantum hardware [16]. This experiment demonstrates a practical pathway to leveraging classical simulability for more efficient quantum resource utilization.

Visualization of Logical Relationships

Diagram 1: BP-Free models and classical simulation logical flow.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for performance comparison.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Solutions

This section details key computational tools and theoretical concepts essential for research in symmetry-embedded architectures and their classical simulations.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Concepts

| Tool/Concept | Type | Function in Research | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamical Lie Algebra (DLA) | Theoretical Framework | Determines the expressiveness and BP behavior of a parametrized quantum circuit; key for proving classical simulability. | [16] |

\(\mathfrak{g}\)-sim Algorithm |

Classical Simulation Software | Efficiently simulates and computes gradients for quantum circuits with polynomial-sized DLA, reducing QPU calls. | [16] |

| Parameter-Shift Rule (PSR) | Quantum Gradient Rule | A method to compute exact gradients of PQCs by running circuits with shifted parameters; used as a baseline for resource comparison. | [16] |

| Symmetry-Embedded Ansatz | Quantum Circuit Architecture | A PQC designed to be invariant or equivariant under a specific symmetry group (e.g., permutation, SE(n)), constraining its evolution to a relevant subspace. | [25] [3] |

| Classical Surrogate Model | Classical Model | A classically simulable model (e.g., created via LOWESA) that approximates the cost landscape of a quantum circuit, often used in the presence of noise. | [16] |

| 7-O-Methyleucomol | 7-O-Methyleucomol, MF:C18H18O6, MW:330.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Baccatin VIII | Baccatin VIII, MF:C33H42O13, MW:646.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Strategic Initializations and Noise Injection Techniques

The pursuit of trainable variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) has identified a central adversary: the barren plateau (BP) phenomenon. In this landscape, the gradients of cost functions vanish exponentially with system size, rendering optimization intractable. Consequently, significant research has focused on developing strategic initializations and noise injection techniques to create BP-free landscapes. However, a critical, emerging perspective suggests that the very structures which mitigate barren plateaus—such as constrained circuits or tailored noise—may simultaneously render the algorithms classically simulable. This guide compares prominent techniques for achieving BP-free landscapes, examining their performance and the inherent trade-off between trainability and computational quantum advantage. Evidence indicates that strategies avoiding barren plateaus often confine the computation to a polynomially-sized subspace, enabling classical algorithms to efficiently simulate the loss function, thus challenging the necessity of quantum resources for these specific variational models [3].

Comparative Analysis of BP-Mitigation Techniques

The following table summarizes key strategic initializations and noise injection approaches, their mechanisms, and their relative performance in mitigating barren plateaus.

Table 1: Comparison of Strategic Initializations and Noise Injection Techniques

| Technique Category | Specific Method | Key Mechanism | Performance & Experimental Data | Classical Simulability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit Initialization | Identity Initialization [3] | Initializes parameters to create an identity or near-identity circuit. | Creates a simple starting point in the loss landscape; avoids exponential concentration from random initialization. | Highly susceptible; circuits start in a trivial state confining evolution to a small subspace. |

| Circuit Architecture | Shallow Circuits with Local Measurements [3] | Limits circuit depth and uses local observables to restrict the operator space. | Provably avoids barren plateaus for local cost functions. | Often efficiently simulable via tensor network methods. |

| Symmetry Embedding | Dynamical Symmetries / Small Lie Algebras [3] | Embeds problem symmetries directly into the circuit architecture. | Constrains the evolution to a subspace whose dimension grows polynomially with qubit count. | The small, relevant subspace can be classically represented and simulated. |

| Noise Injection | Non-Unital Noise/Intermediate Measurements [3] | Introduces structured noise or measurements that break unitary evolution. | Can disrupt the barren plateau phenomenon induced by deep, unitary circuits. | The effective, noisy dynamics can often be classically simulated [3]. |

| Classical Pre-processing | Quantum-Enhanced Classical Simulation [3] | Uses a quantum computer to collect a polynomial number of expectation values, then classically simulates the loss. | Faithfully reproduces the BP-free loss landscape without a hybrid optimization loop. | This approach is a form of classical simulation, by design. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Noise Injection in Classical Machine Learning

The principles of noise injection are extensively studied in classical machine learning, providing valuable insights for quantum approaches. A common protocol involves Gaussian noise injection at the input layer during training. For instance, in human activity recognition (HAR) systems, a time-distributed AlexNet architecture was trained with additive Gaussian noise (standard deviation = 0.01) applied to input video sequences. This technique, inspired by biological sensory processing, enhanced model robustness and generalization. The experimental protocol involved [26]:

- Dataset: Training and evaluation on the EduNet, UCF50, and UCF101 datasets.

- Noise Tuning: A systematic hyperparameter sweep over 17 different noise levels to identify the optimal standard deviation.

- Evaluation: The noise-injected model achieved an overall accuracy of 91.40% and an F1-score of 92.77%, outperforming state-of-the-art models without noise injection [26].

Another advanced protocol employs Bayesian optimization to tune noise parameters. This is particularly effective for complex, non-convex optimization landscapes where grid search or gradient-based methods fail. The methodology includes [27]:

- Noise Placement: Injecting noise at various network placements (inputs, weights, activations, gradients).

- Surrogate Model: Modeling network performance as a Gaussian process prior over the noise level.