Basis Rotation Grouping: A Noise-Resilient Strategy for Efficient Quantum Chemistry Measurements

This article explores basis rotation grouping, an advanced quantum measurement technique that significantly enhances the efficiency and noise resilience of molecular energy estimation on near-term quantum hardware.

Basis Rotation Grouping: A Noise-Resilient Strategy for Efficient Quantum Chemistry Measurements

Abstract

This article explores basis rotation grouping, an advanced quantum measurement technique that significantly enhances the efficiency and noise resilience of molecular energy estimation on near-term quantum hardware. We examine the foundational principles of Hamiltonian decomposition and single-particle basis rotations, detail practical methodologies for implementation including error mitigation through quantum detector tomography and post-selection, address key optimization challenges, and present validation case studies demonstrating order-of-magnitude improvements in measurement precision. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this comprehensive guide bridges theoretical concepts with practical applications in quantum computational chemistry.

The Quantum Measurement Challenge: Why Precision Matters in Computational Chemistry

The Critical Problem of Measurement Noise in Near-Term Quantum Devices

In the rapidly evolving field of quantum computing, measurement noise stands as a fundamental barrier to achieving practical computational advantages with current-generation hardware. Unlike classical bits, quantum bits (qubits) are exceptionally susceptible to environmental interference and control imperfections that introduce errors during the critical measurement phase. This noise problem is particularly acute in Near-Term Intermediate Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, where sophisticated error correction techniques remain impractical due to qubit overhead requirements. For researchers in quantum chemistry and drug development, where precise energy calculations are paramount, understanding and mitigating measurement noise is not merely an academic exercise but a prerequisite for obtaining scientifically valid results.

The impact of measurement noise extends beyond simple bit flips, introducing systematic biases that can invalidate computational outcomes. When measuring quantum states to determine molecular energies or chemical properties, noise compounds throughout the evaluation process, potentially rendering results less reliable than classical alternatives. As quantum devices scale in both qubit count and circuit depth, the complexity of noise characterization grows correspondingly, with non-Markovian effects (where noise exhibits memory-like behavior) becoming increasingly significant. This application note examines the sources, characterization methods, and mitigation strategies for measurement noise, with particular emphasis on basis rotation techniques that enhance measurement efficiency and resilience for quantum chemistry applications.

Characterizing Quantum Noise and Its Impact on Measurements

Fundamental Noise Types and Their Properties

Quantum devices face multiple noise classifications that directly impact measurement fidelity. Understanding these categories is essential for developing effective mitigation strategies:

Markovian Noise: This type of noise behaves in a "memoryless" fashion, where each gate operation experiences independent error sources. The noise at any given moment does not depend on previous states or operations. This characteristic simplifies modeling and is frequently assumed in basic error mitigation approaches. Markovian noise can often be described using simple probabilistic models where errors occur independently at each computational step [1].

Non-Markovian Noise: In contrast, non-Markovian noise exhibits temporal correlations and memory effects, where past interactions influence current noise behavior. This type of noise is particularly challenging because errors can propagate through quantum circuits in complex, correlated patterns. As quantum systems increase in size and complexity, non-Markovian effects become increasingly prevalent and problematic [1].

The distinction between these noise types has profound implications for measurement strategies. While Markovian noise can be addressed with relatively straightforward techniques, non-Markovian noise requires more sophisticated approaches that account for temporal correlations and historical dependencies throughout the computation.

Practical Manifestations of Quantum Noise

In operational quantum computing systems, noise manifests through several observable phenomena:

Decoherence: Qubits gradually lose their quantum state through interactions with the environment, causing the quantum information to fade over time. This represents a fundamental limit on computation duration [2].

Gate Errors: Imperfect control signals and environmental fluctuations cause quantum gates to implement slightly different operations than intended, leading to incorrect state transformations [2].

Measurement Errors: The process of reading out qubit states introduces classification mistakes, where the measured outcome does not match the actual pre-measurement state. These errors directly impact the reliability of computational results [2].

Cross-Talk: neighboring qubits exert influence on each other, creating correlated errors that complicate error mitigation [2].

Table: Classification and Characteristics of Quantum Noise Types

| Noise Type | Temporal Behavior | Primary Sources | Impact on Measurements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Markovian | Memoryless, time-local | Control signal fluctuations, local environmental variations | Independent errors across measurement rounds |

| Non-Markovian | Memory effects, correlated | Qubit interactions, global environmental shifts, 1/f noise | Correlated errors that propagate through circuits |

| Decoherence | Exponential decay | Environmental interactions, temperature fluctuations | Information loss increasing with measurement time |

| Readout-specific | Context-dependent | Amplifier noise, crosstalk, timing jitter | Direct misclassification of quantum states |

Noise-Resilient Measurement Protocols for Quantum Chemistry

Basis Rotation Grouping for Efficient Measurements

Basis rotation grouping represents a sophisticated measurement strategy that significantly reduces the resource overhead for quantum chemistry simulations. The fundamental insight behind this approach is that many terms in a molecular Hamiltonian can be measured simultaneously by applying appropriate basis rotations that diagonalize commuting operators. This methodology stands in contrast to "naive" measurement strategies that measure each term sequentially, resulting in excessive measurement rounds and accumulated noise.

The core protocol for basis rotation grouping involves:

Hamiltonian Decomposition: The molecular Hamiltonian is decomposed into a sum of terms, where each term comprises a respective operator that effects a single particle basis rotation and one or more particle density operators [3].

Term Grouping: Terms are grouped according to their compatibility under single-particle basis rotations. Specifically, terms that are diagonal in the same single-particle basis are grouped together [3].

Simultaneous Measurement: For each group, the quantum computer performs the respective basis rotation, followed by measurement in the computational basis of Jordan-Wigner transformations of the particle density operators [3].

This approach can reduce the required total number of measurements by up to four orders of magnitude compared to naive methods, dramatically decreasing both computational time and noise accumulation [3].

Advanced Error Mitigation Integration

To further enhance measurement resilience, basis rotation grouping can be integrated with additional error mitigation techniques:

Post-Selection by Particle Number: This technique leverages the fact that valid electronic wavefunctions must preserve specific quantum numbers. After measurement, results can be validated by computing the total particle number or spin component using the obtained measurement result. Measurements that deviate from expected values are discarded, providing a powerful form of error mitigation at minimal cost [3].

Dynamical Decoupling: This method involves applying sequences of control pulses between quantum gate operations that effectively average out unwanted interactions causing noise. These pulses help maintain quantum coherence and reduce environmental interactions during computation [1].

Randomized Compiling: This technique modifies gate sequences by adding random gates in such a way that the overall computation remains unchanged, but errors become less correlated. This approach specifically addresses non-Markovian noise by breaking up temporal correlations [1].

Basis Rotation Grouping with Error Mitigation

Zero-Noise Extrapolation Protocol

Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) represents another powerful technique for mitigating measurement noise, particularly when combined with basis rotation strategies. The core principle involves intentionally amplifying noise in a controlled manner to extrapolate back to the zero-noise scenario:

Noise Amplification: Execute the same quantum circuit at multiple different noise levels, either by stretching gate pulses or inserting identity operations [4].

Measurement Collection: Perform measurements at each noise level using efficient basis rotation grouping to obtain expectation values [4].

Extrapolation Function: Fit the relationship between noise level and measurement results using classical post-processing, potentially enhanced with neural networks for improved accuracy [4].

Zero-Noise Estimation: Extrapolate the fitted function to the zero-noise limit to obtain a noise-mitigated estimate of the measured observable [4].

When applied to variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) simulations for molecular systems, this approach has demonstrated the ability to constrain noise errors within the range of ð’ª(10â»Â²) to ð’ª(10â»Â¹), significantly outperforming non-mitigated approaches [4].

Experimental Validation and Performance Metrics

Randomized Benchmarking for Noise Characterization

Randomized Benchmarking (RB) provides a systematic methodology for quantifying the average performance of quantum gates and their susceptibility to noise. The RB protocol involves several key steps [1]:

Initial State Preparation: A qubit is initialized in a known state, typically |0⟩.

Application of Random Gates: A sequence of gates is applied randomly to the qubit, chosen from a specific set (typically the Clifford group).

Final Measurement: After applying the sequence, the final state is measured to determine execution fidelity.

Fidelity Calculation: The process is repeated for sequences of varying lengths to determine the average sequence fidelity as a function of circuit depth.

The primary output of RB is the average gate fidelity, which provides a standardized metric for comparing performance across different quantum hardware platforms. This metric is particularly valuable for establishing baseline noise levels before implementing more specialized measurement protocols for quantum chemistry applications.

Table: Noise Mitigation Techniques and Their Applications

| Mitigation Technique | Protocol Steps | Noise Types Addressed | Resource Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basis Rotation Grouping | Hamiltonian decomposition, term grouping, simultaneous measurement | Readout errors, stochastic noise | Reduced measurement rounds (up to 10â´ improvement) |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation | Noise amplification, multi-level measurement, extrapolation | Gate errors, decoherence, correlated noise | 3-5x additional circuit executions |

| Dynamical Decoupling | Insertion of control pulses between operations | Low-frequency noise, decoherence | Moderate pulse sequencing overhead |

| Randomized Compiling | Gate sequence randomization, recompilation | Non-Markovian noise, correlated errors | Minimal classical compilation |

Quantum Chemistry Application Benchmarks

The effectiveness of noise-resilient measurement strategies is ultimately validated through practical quantum chemistry simulations. Several benchmark studies have demonstrated significant improvements:

In simulations of the Hâ‚„ molecule using a noise-mitigated VQE approach with basis rotation grouping, researchers constrained energy errors to within 0.01-0.1 Hartree, surpassing mainstream variational eigensolver methods [4].

For molecular systems such as symmetrically stretched hydrogen chains, water molecules, and nitrogen dimers, measurement strategies that employ simultaneous measurement of compatible operators have demonstrated both noise resilience and reduced measurement overhead [3].

Experimental validation on real quantum hardware has shown that approaches combining basis rotation grouping with post-selection by particle number can effectively mitigate readout errors caused by long Jordan-Wigner strings, which are particularly problematic in quantum chemistry applications [3].

Noise Validation Workflow for Quantum Chemistry

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of noise-resilient measurement strategies requires specific computational tools and methodological components. The following resources constitute essential "research reagents" for experiments in this domain:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Noise-Resilient Quantum Measurements

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Simulation Platforms | Amazon Braket (DM1 simulator), MindQuantum, Qaptiva | Simulation of noisy quantum systems with configurable error models | Density matrix simulators essential for noise modeling |

| Noise Characterization Tools | Randomized Benchmarking protocols, Gate Set Tomography | Quantification of gate and measurement errors | Provides input parameters for error mitigation |

| Error Mitigation Libraries | Zero-Noise Extrapolation, Probabilistic Error Cancellation | Implementation of software-based error mitigation | Often requires integration with algorithm-specific code |

| Chemistry-Specific Compilers | Basis rotation grouping, Fermion-to-qubit transforms | Efficient measurement strategy generation | Critical for reducing measurement overhead in chemistry |

| Classical Optimizers | Stochastic Gradient Descent, CMA-ES | Parameter optimization in hybrid quantum-classical algorithms | Robustness to noisy objective functions essential |

Measurement noise represents a fundamental challenge in near-term quantum devices, particularly for precision applications such as quantum chemistry and drug development. The framework of basis rotation grouping provides a powerful methodology for enhancing measurement efficiency while simultaneously incorporating error resilience. When combined with techniques such as zero-noise extrapolation, dynamical decoupling, and post-selection validation, these approaches enable significantly more reliable quantum computations on existing hardware.

The continuing evolution of noise characterization protocols and hardware-aware algorithm design promises further improvements in measurement fidelity. As quantum devices progressively incorporate better intrinsic noise properties, the synergistic combination of hardware advances and software mitigation will ultimately unlock the full potential of quantum computing for chemical simulation and drug development. Researchers in this field should maintain focus on both theoretical understanding of noise processes and practical implementation of mitigation strategies that provide measurable improvements in computational accuracy.

Hamiltonian Decomposition Approaches for Molecular Systems

Quantum computing presents a promising alternative for the direct simulation of quantum systems with the potential to explore chemical problems beyond classical computational capabilities [5]. However, a fundamental obstacle for quantum algorithms addressing the electronic structure problem, particularly on near-term quantum devices, is the measurement problem—the prohibitively large number of measurements required to achieve chemical accuracy [6]. When using the variational quantum eigensolver approach, the molecular Hamiltonian must be decomposed into measurable components, typically Pauli operators. The required number of measurements scales poorly with system size, making this a critical bottleneck [7]. For example, while a hydrogen molecule Hamiltonian requires only 15 measurement terms, a water molecule Hamiltonian expands to 1,086 terms [7]. This tutorial explores advanced Hamiltonian decomposition approaches that dramatically reduce this measurement overhead while enhancing noise resilience.

Hamiltonian Decomposition Methodologies

Mathematical Framework of Electronic Structure Hamiltonians

The Hamiltonian of a molecular system in second-quantized form can be expressed as:

[H = \mu + \sum{\sigma, pq} h{pq} a^\dagger{\sigma, p} a{\sigma, q} + \frac{1}{2} \sum{\sigma \tau, pqrs} g{pqrs} a^\dagger{\sigma, p} a^\dagger{\tau, q} a{\tau, r} a{\sigma, s}]

where the tensors (h{pq}) and (g{pqrs}) represent one- and two-body integrals, (a^\dagger) and (a) are creation and annihilation operators, (\mu) is the nuclear repulsion energy, (\sigma) represents spin, and (p, q, r, s) are orbital indices [8]. Through the chemist notation transformation, we obtain a modified representation:

[H{\text{C}} = \mu + \sum{\sigma \in {\uparrow, \downarrow}} \sum{pq} T{pq} a^\dagger{\sigma, p} a{\sigma, q} + \sum{\sigma, \tau \in {\uparrow, \downarrow}} \sum{pqrs} V{pqrs} a^\dagger{\sigma, p} a{\sigma, q} a^\dagger{\tau, r} a_{\tau, s}]

where (T{pq} = h{pq} - 0.5 \sum{s} g{pqss}) and (V_{pqrs}) is the rearranged two-body tensor [8]. This representation enables more efficient factorization approaches.

Comparative Analysis of Decomposition Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Hamiltonian Decomposition Methods

| Method | Mathematical Form | Term Reduction | Measurement Efficiency | Error Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive Pauli Decomposition | (H = \sumi ci hi) where (hi) are Pauli words | (O(N^4)) terms | Low - requires many separate measurements | Poor - susceptible to readout errors |

| Double Factorization (DF) | (V{pqrs} = \sumt^T L{pq}^{(t)} L{rs}^{(t){\dagger}}) with (L^{(t)}{pq} = \sum{i} U{pi}^{(t)} Wi^{(t)} U_{qi}^{(t)}) | (O(N^3)) terms | Moderate - reduced term count | Moderate - Jordan-Wigner nonlocality issues |

| Compressed Double Factorization (CDF) | (V{pqrs} \approx \sumt^T \sum{ij} U{pi}^{(t)} U{qi}^{(t)} Z{ij}^{(t)} U{rj}^{(t)} U{sj}^{(t)}) with regularization | (O(N)) terms | High - significantly reduced measurements | Enhanced - optimized variance and noise resilience |

| Basis Rotation Grouping | (H = U0(\sump gp np)U0^\dagger + \sum{\ell=1}^L U\ell(\sum{pq} g{pq}^{(\ell)} np nq)U\ell^\dagger) | (O(N)) groupings | Very high - linear term scaling | Excellent - measures local operators only |

The compressed double factorization approach achieves its efficiency through numerical tensor-fitting with regularization, minimizing the approximation error (||V - V^\prime||) below a desired threshold while reducing the number of terms in the two-body factorization from (O(N^3)) to (O(N)) [8]. For a sample four-orbital system, this reduced the factorization terms from 10 to 6—a 40% reduction [8].

Basis rotation grouping provides particularly dramatic improvements, offering a cubic reduction in term groupings over prior state-of-the-art approaches and enabling measurement times three orders of magnitude smaller than commonly referenced bounds for the largest systems [5].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Compressed Double Factorization

Step-by-Step Protocol for Hamiltonian Decomposition

Protocol 1: Compressed Double Factorization of Molecular Hamiltonians

Input Preparation

- Molecular structure (symbols and geometry)

- Basis set specification

- Decomposition tolerance parameters (

tol_factor,tol_eigval) - Regularization type ("L1", "L2", or None)

Integral Computation

- Compute nuclear repulsion energy, one-body, and two-electron integrals using electronic structure methods:

Chemist Notation Transformation

- Transform two-body integrals to chemist notation:

Symmetry Shifting (BLISS Technique)

- Apply block-invariant symmetry shift to reduce one-norm:

Tensor Factorization

- Perform compressed double factorization with regularization:

Validation

- Verify decomposition accuracy by reconstructing approximate two-body tensor:

Output

- Factorized Hamiltonian components ready for quantum circuit implementation

- Quality metrics: one-norm reduction, approximation error, term count

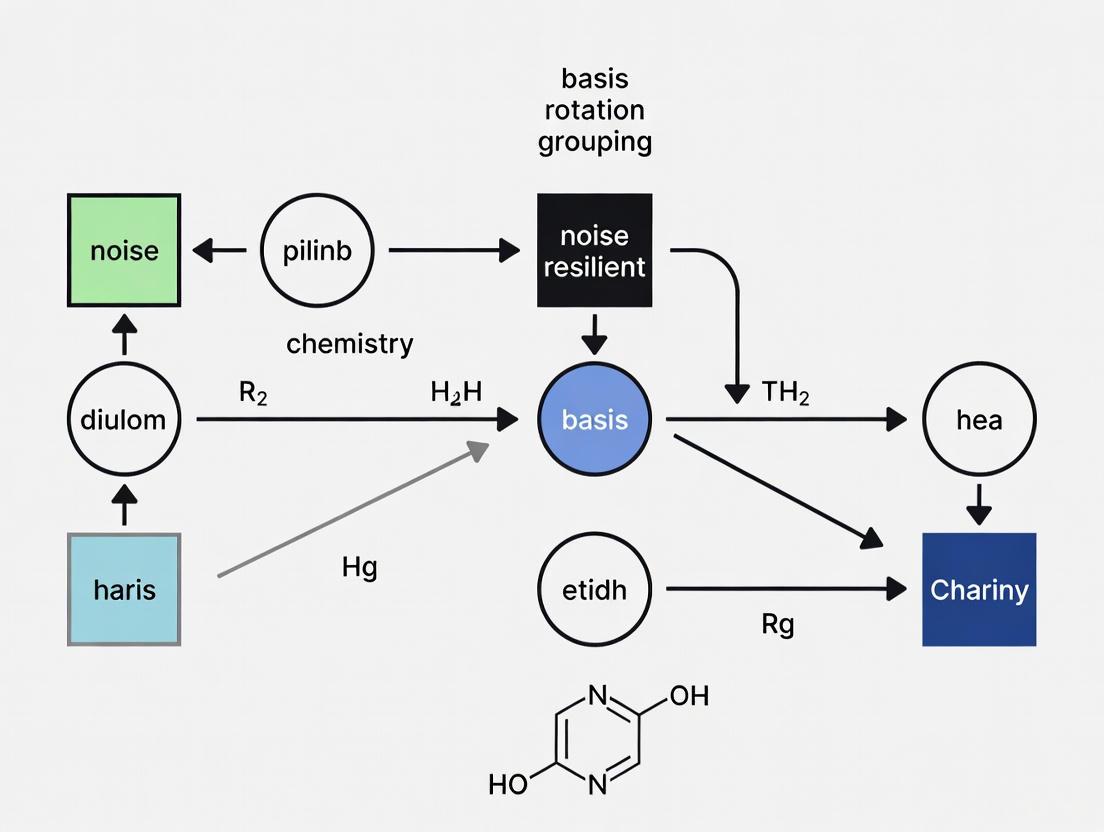

Workflow Visualization

CDF Hamiltonian Decomposition Workflow

Basis Rotation Grouping for Efficient Measurements

Theoretical Foundation

Basis rotation grouping represents a paradigm shift in measurement strategies for quantum chemistry simulations. The approach leverages tensor factorization techniques to dramatically reduce measurement requirements [5]. The fundamental insight is that the electronic structure Hamiltonian can be expressed in a factorized form:

[H = U0\left(\sump gp np\right)U0^\dagger + \sum{\ell=1}^L U\ell\left(\sum{pq} g{pq}^{(\ell)} np nq\right)U\ell^\dagger]

where (gp) and (g{pq}^{(\ell)}) are scalars, (np = ap^\dagger ap), and the (U\ell) are unitary operators implementing single-particle basis changes [5]. The measurement strategy applies the (U\ell) circuit directly to the quantum state prior to measurement, enabling simultaneous sampling of all (\langle np \rangle) and (\langle np nq \rangle) expectation values in the rotated basis.

Experimental Protocol for Basis Rotation Measurements

Protocol 2: Basis Rotation Grouping for Noise-Resilient Chemistry Measurements

Hamiltonian Factorization

- Perform eigendecomposition or pivoted Cholesky decomposition of the two-electron integral tensor

- Discard small eigenvalues to achieve controllable approximation (optional)

- Obtain unitaries (U\ell) and coefficients (gp), (g_{pq}^{(\ell)})

Quantum Circuit Design

- For each term (\ell = 0) to (L):

- Prepare ansatz state (|\psi(\theta)\rangle)

- Apply basis rotation circuit (U_\ell)

- Measure in computational basis to obtain occupation numbers

- For each term (\ell = 0) to (L):

Expectation Value Estimation

- Compute energy expectation value as: [ \langle H \rangle = \sump gp {\langle np \rangle}0 + \sum{\ell=1}^L \sum{pq} g{pq}^{(\ell)} {\langle np nq \rangle}\ell ]

- where subscript (\ell) denotes measurements after applying (U_\ell)

Error Mitigation via Symmetry Postselection

- Exploit inherent symmetries (particle number, spin) for error detection

- Discard measurements violating symmetry constraints

- This provides powerful error mitigation without additional circuit depth

Performance Validation

- Compare energy accuracy against classical methods

- Verify reduction in measurement variance

- Quantize noise resilience improvement

Measurement Efficiency Analysis

Table 2: Measurement Requirements for Molecular Systems

| Molecule | Qubits | Naive Measurements | Basis Rotation Grouping | Reduction Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H₂ | 4 | 15 | 5 | 3.0× |

| LiH | 12 | 630 | 48 | 13.1× |

| H₂O | 14 | 1,086 | 72 | 15.1× |

| N₂ | 20 | 2,959 | 135 | 21.9× |

Basis rotation grouping provides multiple advantages beyond mere term reduction. By transforming to measurement bases where operators are diagonal, it enables measurement of only one- and two-local qubit operators instead of the nonlocal operators resulting from Jordan-Wigner transformation [5]. This eliminates challenges associated with sampling nonlocal operators in the presence of measurement error while enabling efficient postselection-based error mitigation [5].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Hamiltonian Decomposition

| Resource | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| PennyLane Quantum Chemistry Module | Compute molecular integrals and perform Hamiltonian decomposition | qml.qchem.electron_integrals(mol)() qml.qchem.factorize(two_chem, compressed=True) |

| HamLib Library | Benchmarking database of quantum Hamiltonians for algorithm testing | Provides standardized Hamiltonian sets ranging from 2 to 1000 qubits [9] |

| Symmetry Shift Functions | Reduce Hamiltonian one-norm via block-invariant symmetry shifts | qml.qchem.symmetry_shift(nuc_core, one_chem, two_chem, n_elec) [8] |

| GFlowNets for Grouping | Machine learning approach for optimal Hamiltonian term grouping | Probabilistic framework for grouping commuting terms to minimize measurements [6] |

| Basis Rotation Circuits | Implement unitary changes of single-particle basis | Givens rotation networks for exact basis transformations [5] |

These tools collectively provide researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for implementing advanced Hamiltonian decomposition strategies. The PennyLane framework offers particularly accessible implementations of compressed double factorization and symmetry shifting techniques [8], while specialized libraries like HamLib provide standardized benchmarking datasets [9].

Advanced Hamiltonian decomposition approaches, particularly compressed double factorization and basis rotation grouping, represent significant advancements toward practical quantum computational chemistry. These methods simultaneously address the critical measurement bottleneck while enhancing noise resilience through intelligent term grouping and symmetry-aware error mitigation. The experimental protocols outlined provide researchers with practical methodologies for implementing these techniques, with the potential to reduce measurement requirements by orders of magnitude. As quantum hardware continues to advance, these decomposition strategies will play an increasingly vital role in enabling quantum computational chemistry applications for drug development and materials design.

In computational chemistry, chemical precision refers to the maximum allowable error in energy calculations to ensure that the results are chemically meaningful and predictive. This is formally defined as a threshold of 1.6 × 10â»Â³ Hartree, a value motivated by the sensitivity of chemical reaction rates to changes in energy [10]. Achieving this level of accuracy is critical for simulating chemical processes reliably, particularly for applications like drug design and materials science.

Within the framework of variational quantum algorithms, such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), the objective is to estimate molecular energies to within this precision. However, a key distinction exists between chemical precision (the statistical precision of an estimation procedure) and chemical accuracy (the exact error of an ansatz state relative to a molecule's true ground state energy) [10]. This article details the experimental protocols and methodologies for achieving chemical precision in the context of advanced measurement strategies, specifically basis rotation grouping, on near-term quantum hardware.

The Challenge of Measurement in Quantum Chemistry

Accurately measuring the expectation value of a molecular Hamiltonian on a quantum computer is a resource-intensive task. The Hamiltonian must first be decomposed into a sum of Pauli operators: $$H = \sumi ci hi$$ where ( hi ) are Pauli words [7]. The number of these terms grows polynomially with the size of the molecule, becoming a significant bottleneck. For example, while an Hâ‚‚ molecule Hamiltonian has 15 terms, a water (Hâ‚‚O) molecule Hamiltonian requires the measurement of 1086 distinct terms [7].

The total number of measurements ( M ) required to estimate the energy to a precision ( \epsilon ) is bounded by: $$M \le {\left(\frac{{\sum}{\ell}\left|{\omega}{\ell}\right|}{\epsilon}\right)}^{2}$$ where ( {\omega}{\ell} ) are the coefficients of the Pauli terms ( P{\ell} ) in the Hamiltonian [5]. This relationship highlights the challenge of achieving chemical precision (a small ( \epsilon )) without an "astronomically large" number of measurements [5].

Table 1: Measurement Overhead for Example Molecules

| Molecule | Number of Qubits | Hamiltonian Terms | Measurement Grouping Strategy | Resulting Number of Measurements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | 4 | 15 | Not Specified | 15 [7] |

| Hâ‚‚O | 14 | 1086 | Not Specified | 1086 [7] |

| BODIPY (8e8o active space) | 16 | 13,981 | Hamiltonian-Inspired Locally Biased Classical Shadows | Significantly Reduced [10] |

| General Systems (vs. Naive) | N/A | N/A | Basis Rotation Grouping | Cubic Reduction [5] |

Core Strategy: Basis Rotation Grouping

Theoretical Foundation

Basis Rotation Grouping is a measurement strategy rooted in a low-rank factorization of the electronic structure Hamiltonian. The technique leverages a factorized form of the Hamiltonian [5]: $$H={U}{0}\left({\sum }{p}{g}{p}{n}{p}\right){U}{0}^{\dagger }+{\sum }{\ell=1}^{L}{U}{\ell }\left({\sum }{pq}{g}{pq}^{(\ell )}{n}{p}{n}{q}\right){U}{\ell }^{\dagger }$$ Here, ( {g}{p} ) and ( {g}{pq}^{(\ell )} ) are scalars, ( {n}{p}={a}{p}^{\dagger }{a}{p} ) is the number operator, and the ( U{\ell} ) are unitary operators that implement a single-particle change of the orbital basis [5]. This decomposition allows for a drastic reduction in the number of distinct measurement settings required.

Protocol: Implementing Basis Rotation Grouping

This protocol describes the steps for implementing the Basis Rotation Grouping technique to measure the energy of a prepared quantum state.

Objective: Estimate the expectation value ( \langle H \rangle ) of a molecular Hamiltonian for a given quantum state ( |\psi(\theta)\rangle ) to a target precision. Primary Outcome: A significant reduction in the number of distinct quantum measurements and inherent resilience to readout noise.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Near-term Quantum Computer | Executes the quantum circuits for state preparation and basis rotation. |

| Classical Computer | Performs the Hamiltonian factorization, optimizes measurement allocation, and post-processes results. |

| Vibrational Structure Program (e.g., ADGA) | Generates the potential energy surface (PES) for the molecular system under study [11]. |

| Quantum Circuit Simulator | Validates the measurement strategy and circuit execution before running on hardware. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) Toolkit | Characterizes readout errors to enable unbiased estimation [10]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Hamiltonian Factorization:

- On a classical computer, perform a double factorization of the electronic Hamiltonian. This typically begins with an eigendecomposition of the two-electron integral tensor to obtain the form shown in the theoretical foundation [5].

- Output: A set of unitary matrices ( {U{\ell}} ) and scalar coefficients ( {g{p}} ), ( {g_{pq}^{(\ell)}} ).

Circuit Design and Execution:

- For each fragment ( \ell ) (from 0 to L), design a quantum circuit that: a. Prepares the state ( |\psi(\theta)\rangle ). b. Applies the basis rotation circuit ( U_{\ell} ) to the state.

- Execute each circuit on the quantum processor, measuring all qubits in the computational basis. This simultaneously samples all ( \langle n{p} \rangle ) and ( \langle n{p}n_{q} \rangle ) expectation values in the rotated basis [5].

Data Collection and Post-processing:

- For each fragment ( \ell ), collect the measurement outcomes (shots) to estimate the probabilities of each bitstring.

- From these probabilities, compute the expectation values ( {\langle {n}{p}\rangle }{\ell } ) and ( {\langle {n}{p}{n}{q}\rangle }_{\ell } ).

Energy Estimation:

- Classically reconstruct the energy estimate by combining the results from all fragments according to the formula [5]: $$\langle H\rangle ={\sum}{p}{g}{p}{\langle {n}{p}\rangle }{0}+{\sum }{\ell=1}^{L}\sum _{pq}{g}{pq}^{(\ell )}{\langle {n}{p}{n}{q}\rangle }_{\ell }$$

Error Mitigation Integration (Optional but Recommended):

- To combat readout error, perform Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) to characterize the noisy measurement effects. Use this information to build an unbiased estimator for the energy [10].

- The blended scheduling technique can be employed, where circuits for QDT and energy estimation are interleaved in time to mitigate the impact of time-dependent noise [10].

Complementary Measurement Optimization Techniques

Locally Biased Random Measurements

This technique reduces the "shot overhead" (number of times the quantum computer is measured) by intelligently selecting measurement settings. Instead of sampling all settings uniformly, it biases the selection towards those that have a larger impact on the energy estimation, while maintaining the informationally complete nature of the measurement strategy [10]. This approach is particularly powerful when combined with the classical shadows framework.

Pauli Term Grouping by Commutativity

A widely used strategy involves grouping Hamiltonian terms into simultaneously measurable sets. Two primary schemes exist:

- Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC): Terms commute locally on each qubit subspace. Diagonalization requires only single-qubit gates [11] [12].

- Full Commutativity (FC): Terms commute as whole tensor products. Diagonalization may require both one- and two-qubit gates but generally leads to fewer, larger groups [11].

The Sorted Insertion (SI) algorithm is an effective greedy method for both schemes. Terms are sorted by the absolute value of their coefficients. The algorithm iterates through the list, placing each term into the first group with which it is compatible (QWC or FC), or creating a new group if none exist [11] [12].

Error Mitigation via Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT)

Readout errors can be mitigated by performing QDT to characterize the noisy measurement process. The protocol involves:

- Preparing and measuring a complete set of basis states to construct a calibration matrix.

- Using this matrix to correct the noisy statistics obtained from energy estimation experiments, creating an unbiased estimator [10].

- Implementing blended scheduling, where circuits for QDT and energy estimation are interleaved over time to average out temporal noise fluctuations [10].

Table 3: Performance of Advanced Techniques on Near-Term Hardware

| Technique | Key Innovation | Demonstrated Result | System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basis Rotation Grouping [5] | Low-rank factorization of Hamiltonian | Cubic reduction in term groupings; measurements of 1- and 2-local operators only. | Electronic Structure |

| Locally Biased Shadows & QDT [10] | Shot-efficient biased sampling + readout error mitigation | Reduction of measurement errors from 1-5% to 0.16% (close to chemical precision). | BODIPY molecule on IBM Eagle r3 |

| Coordinate Transformation [11] | Exploiting distinguishable modes in vibrational Hamiltonians | Up to 7-fold reduction in number of measurements for 3-mode molecules. | Vibrational Structure |

Case Study: Achieving Near-Chemical Precision on Hardware

A 2025 study demonstrated the power of combining these techniques by estimating the energy of the BODIPY-4 molecule on an IBM Eagle r3 quantum processor [10].

Experimental Protocol:

- System Preparation: The Hartree-Fock state of the BODIPY molecule was prepared for various active spaces (e.g., 8, 12, 16 qubits). This state requires no two-qubit gates, isolating measurement errors.

- Measurement Strategy: Hamiltonian-inspired locally biased classical shadows were used for shot-efficient measurement.

- Error Mitigation: Repeated settings with parallel Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) were run in a blended schedule with the main experiment to mitigate time-dependent noise.

- Result: The combined strategy reduced the absolute error in the energy estimation to 0.16%, an order-of-magnitude improvement from the 1-5% error baseline and close to the target chemical precision of 0.16% (1.6 × 10â»Â³ Hartree) [10].

Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements Versus Pauli Grouping Strategies

Accurately measuring complex molecular Hamiltonians is a fundamental challenge in quantum computational chemistry. On near-term quantum devices, high readout errors and limited sampling statistics make achieving chemical precision (approximately (1.6 \times 10^{-3}) Hartree) particularly difficult [13] [10]. Two dominant strategies have emerged for estimating expectation values of quantum chemical observables: Informationally Complete (IC) measurements and Pauli grouping strategies.

IC measurements allow for the estimation of multiple observables from the same measurement data and provide a direct interface for implementing efficient error mitigation methods [13] [10]. In contrast, Pauli grouping strategies, a form of non-IC measurement, focus on partitioning the Hamiltonian into efficiently measurable fragments, often based on operator commutativity [13] [14]. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these approaches, framed within research on basis rotation grouping for efficient, noise-resilient chemistry measurements.

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Analysis

Core Principles and Definitions

- Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements: These measurements allow for the full reconstruction of the quantum state. A key advantage is the ability to mitigate detector noise by performing Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT), which uses noisy measurement effects to build an unbiased estimator for properties like molecular energy [13] [10]. Techniques such as locally biased random measurements reduce the "shot overhead" (number of measurements) while maintaining the informational completeness of the strategy [13].

- Pauli Grouping Strategies: These are non-IC methods where the Hamiltonian observable is measured in groups of Pauli strings instead of individually [13]. The primary goal is to minimize the number of measurement configurations or "circuit overhead." This is achieved by grouping commuting operators (using qubit-wise or full commutativity) into measurable fragments that can be rotated into a shared basis for simultaneous measurement [5] [14]. Advanced techniques exploit overlapping fragments, where a Pauli product can be measured in multiple groups if it commutes with all members of those groups, leading to a further reduction in the total number of measurements required [14].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes key performance characteristics of both approaches, with data drawn from experimental implementations.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of IC and Pauli Grouping Strategies

| Feature | IC Measurements | Pauli Grouping (Basis Rotation Grouping) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | State/observable estimation with error mitigation [13] [10] | Efficient Hamiltonian averaging [5] |

| Error Mitigation | Direct via Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) [13] [10] | Indirect via circuit design; can be combined with post-processing error mitigation [5] |

| Shot Overhead Reduction | Locally biased random measurements [13] | Grouping to minimize distinct measurement bases [5] [14] |

| Circuit Overhead Reduction | Repeated settings with parallel QDT [13] [10] | Non-local unitary transformations for measuring fully commuting groups [5] [14] |

| Reported Accuracy | 0.16% error on IBM Eagle r3 (from 1-5% baseline) [10] | Cubic reduction in term groupings; measurement times reduced by 3 orders of magnitude for large systems [5] |

| Measurement Type | Non-IC (focus on observable-specific estimation) [13] | Non-IC (focus on observable-specific estimation) [13] |

| Key Application Demonstrated | BODIPY molecule energy estimation (Sâ‚€, Sâ‚, Tâ‚) [13] [10] | Electronic ground-state energy estimation of strongly correlated systems [5] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for High-Precision IC Measurement with QDT

This protocol outlines the steps for molecular energy estimation using IC measurements, as demonstrated for the BODIPY molecule on IBM quantum hardware [13] [10].

1. Pre-Experimental Calculations:

- Classical Simulation: Perform a Hartree-Fock calculation for the target molecule (e.g., BODIPY-4) to obtain the reference state and the molecular Hamiltonian in a selected active space (e.g., 4e4o, 8 qubits).

- Hamiltonian Preparation: Generate the qubit Hamiltonian, which will be a sum of a large number of Pauli strings (e.g., 361 strings for an 8-qubit active space) [13].

2. Quantum Computer Execution Setup:

- State Preparation: Initialize the qubits in the Hartree-Fock state. This is a separable state, requiring no two-qubit gates, to isolate measurement errors from gate errors [13] [10].

- Blended Scheduling: To mitigate time-dependent noise, create a job schedule that interleaves (blends) circuits for energy estimation with circuits dedicated to Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT). This ensures all experiments experience the same average noise conditions [13].

3. Measurement and Data Collection:

- Locally Biased Sampling: Sample ( S ) different measurement settings (e.g., ( S = 7 \times 10^4 )), with a bias towards settings that have a larger impact on the energy estimation [13].

- Repeated Settings with Parallel QDT: For each of the ( S ) settings, repeat the measurement ( T ) times (e.g., ( T = 7 )) to collect statistics. In parallel, execute QDT circuits to characterize the readout noise matrix for the current calibration cycle [13] [10].

4. Classical Post-Processing and Error Mitigation:

- Apply QDT Correction: Use the noise matrix obtained from QDT to build an unbiased estimator for the expectation values of the Pauli strings. This corrects for systematic readout errors [13].

- Energy Estimation: Reconstruct the estimated energy from the corrected expectation values. Evaluate the absolute error against a classically computed reference energy and the standard error (precision) from the estimator variance [10].

Protocol for Efficient Measurement via Basis Rotation Grouping

This protocol is based on the "Basis Rotation Grouping" method, which leverages a low-rank factorization of the Hamiltonian [5].

1. Hamiltonian Factorization:

- Perform an eigendecomposition (or Cholesky decomposition) of the two-electron integral tensor to factorize the electronic structure Hamiltonian into the form: [ H = U0 \left(\sump gp np\right)U0^\dagger + \sum{\ell=1}^L U\ell \left(\sum{pq} g{pq}^{(\ell)} np nq\right) U\ell^\dagger ] Here, (np = ap^\dagger ap), (gp) and (g{pq}^{(\ell)}) are scalars, and (U\ell) are unitary operators that perform a single-particle basis rotation [5].

- For arbitrary basis quantum chemistry, (L = O(N)) is often sufficient. In specific bases like the plane wave basis, (L=1) is possible [5].

2. Quantum Circuit Execution:

- For each term ( \ell = 0, 1, ..., L ) in the factorization:

- Prepare the ansatz state ( |\psi(\theta)\rangle ) on the quantum processor.

- Apply the basis rotation circuit ( U\ell ) to the state.

- Measure in the computational basis to sample the expectation values of the number operators ( \langle np \rangle\ell ) and products ( \langle np nq \rangle\ell ) in the rotated basis.

3. Classical Data Combination:

- Compute the total energy expectation value by combining the results from all measurement rounds: [ \langle H \rangle = \sump gp {\langle np \rangle}0 + \sum{\ell=1}^L \sum{pq} g{pq}^{(\ell)} {\langle np nq \rangle}\ell ]

- This strategy allows for the estimation of fermionic operator expectation values by measuring only one- and two-local qubit operators, avoiding the exponential suppression of signal caused by non-local Pauli measurements in the presence of readout error [5].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the high-level logical relationship and comparative workflow between the two measurement strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Technique | Function / Description | Relevance to Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | Characterizes the readout noise matrix of the quantum device to build an unbiased estimator [13] [10]. | Critical for IC measurement error mitigation. |

| Locally Biased Random Measurements | A technique for choosing measurement settings that have a larger impact on the final estimate, reducing shot overhead [13]. | Used in IC measurements to enhance efficiency. |

| Blended Scheduling | An execution schedule that interleaves different circuit types to average out time-dependent noise [13] [10]. | Used in IC measurements to improve accuracy. |

| Low-Rank Tensor Factorization | Factorizes the two-electron integral tensor, enabling a compact Hamiltonian representation for measurement [5]. | Foundation of the Basis Rotation Grouping protocol. |

| Overlapping Grouping | A framework allowing Pauli terms to be assigned to multiple measurement groups, reducing total measurement cost [14]. | Advanced Pauli grouping technique. |

| Greedy Grouping Algorithms | Heuristic algorithms that group commuting Pauli products sequentially to minimize the norm of the residual Hamiltonian [14]. | Common in qubit-space Pauli grouping to minimize variances. |

| Unitary Basis Rotation Circuits (Uâ‚—) | Quantum circuits that implement a change of single-particle basis, allowing measurement of number operators [5]. | Core component of the Basis Rotation Grouping protocol. |

| Tacrolimus-13C,d2 | Tacrolimus-13C,d2, CAS:144490-63-1, MF:C44H69NO12, MW:804.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Catechin | Catechin, CAS:100786-01-4, MF:C15H14O6, MW:290.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between IC measurements and Pauli grouping strategies is context-dependent. IC measurements, enhanced with QDT and advanced scheduling, excel in scenarios demanding high precision and robust error mitigation on today's noisy hardware, as demonstrated by achieving 0.16% estimation error for molecular energies [10]. Pauli grouping strategies, particularly Basis Rotation Grouping, offer a structurally efficient approach with a superior asymptotic reduction in measurement runtime, making them promising for scaling to larger systems [5]. For researchers focused on obtaining the most reliable results from current NISQ-era devices, particularly for complex molecules like BODIPY, the IC measurement pathway provides a comprehensive, noise-resilient solution. Those prioritizing algorithmic efficiency and preparing for more stable future hardware may find the Pauli grouping approach, especially with overlapping fragments and non-local transformations, to be a powerful framework.

Accurately measuring the energy of molecular systems is a cornerstone of quantum computational chemistry. On near-term quantum hardware, this task is governed by a critical trade-off between precision and resource expenditure, framed by three fundamental overheads: shot overhead (number of circuit repetitions), circuit overhead (number of distinct circuit configurations), and the impact of temporal noise (time-dependent hardware drift). The pursuit of chemical precision, often defined as an error below 1.6 mHa (milliHartree), demands strategies that directly confront these constraints [10]. The framework of basis rotation grouping, which leverages unitary transformations to measure groups of commuting operators simultaneously, provides a powerful foundation for building noise-resilient measurement protocols. This application note details the quantitative scale of these challenges and presents validated experimental protocols to mitigate them, enabling more reliable molecular energy estimation on today's noisy hardware.

Quantitative Analysis of Key Overheads

The resource requirements for achieving chemical precision scale dramatically with molecular size. The tables below summarize the core challenges and the efficacy of mitigation strategies.

Table 1: Scaling of Hamiltonian Measurement Complexity with Molecular Size [7]

| Molecule | Qubits | Hamiltonian Terms (Naive) | Basis Rotation Groupings (L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | 4 | 15 | O(N) - Example Reduction |

| Hâ‚‚O | 14 | 1,086 | O(N) - Example Reduction |

| 20-Qubit System | 20 | ~10âµ (Est.) | O(N) [5] |

Shot Overhead refers to the number of repeated circuit executions (shots) required to estimate an expectation value within a target precision. For a Hamiltonian ( H = \sumi ci hi ), a common upper bound is ( M \propto (\sumi |c_i| / \epsilon)^2 ), where ( \epsilon ) is the target precision [5]. This scaling can impose an "astronomically large" number of measurements [5].

Circuit Overhead is the number of distinct quantum circuit configurations (e.g., different basis rotations) that must be executed. The number of unique measurement bases, L, is a key metric. Advanced factorization techniques can achieve L = O(N) for arbitrary basis quantum chemistry, a cubic reduction over prior state-of-the-art methods [5].

Temporal Noise encompasses slow, time-varying drifts in hardware parameters such as readout fidelity or qubit frequency, which can introduce systematic errors that are not averaged away by simple shot accumulation. On current hardware, readout errors on the order of 10â»Â² are common [10].

Table 2: Error Budget and Mitigation Efficacy in a Case Study (BODIPY-4 Molecule) [10]

| Error Source | Initial Error | After Mitigation | Mitigation Technique(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Readout Error | 1-5% | 0.16% | Parallel Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) |

| Estimation Bias | Significant | Reduced to near chemical precision | QDT-informed unbiased estimator |

| Shot Noise/Precision | N/A | Standard Error controlled via shot allocation | Locally Biased Random Measurements |

Experimental Protocols for Overhead Reduction

Protocol 1: Basis Rotation Grouping for Circuit and Shot Reduction

This protocol leverages a low-rank factorization of the electronic structure Hamiltonian to drastically reduce the number of unique measurement circuits [5].

1. Primary Objective To minimize both circuit and shot overhead in the estimation of the molecular energy ( \langle H \rangle ) by measuring groups of non-commuting Pauli terms simultaneously via a pre-processing unitary transformation.

2. Experimental Workflow The following diagram illustrates the streamlined workflow for Basis Rotation Grouping.

3. Reagents and Resources

- Quantum Hardware/Simulator: Device with native gateset capable of implementing the unitaries ( U_\ell ).

- Classical Computational Software: For performing the Hamiltonian factorization (e.g., via a double factorization of the two-electron integral tensor [5]).

- Hamiltonian: The molecular Hamiltonian in its second-quantized form.

4. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Step 1 — Hamiltonian Factorization: Classically compute the factorization of the Hamiltonian as shown in Eq. (2) [5]: ( H = U0 \left(\sump gp np\right) U0^\dagger + \sum{\ell=1}^L U\ell \left(\sum{pq} g{pq}^{(\ell)} np nq\right) U\ell^\dagger ) Here, ( np = ap^\dagger ap ) is the number operator, and ( U\ell ) are basis rotation unitaries.

- Step 2 — Quantum Execution: For each term ( \ell = 0, 1, \dots, L ) in the factorization:

- Prepare the ansatz state ( |\psi(\theta)\rangle ) on the quantum processor.

- Apply the basis rotation circuit ( U\ell ).

- Measure all qubits in the computational basis to sample from the distribution of occupation numbers ( np ) and products ( np nq ).

- Step 3 — Classical Post-Processing: Reconstruct the energy expectation value using Eq. (4) [5]: ( \langle H \rangle = \sump gp {\langle np \rangle}0 + \sum{\ell=1}^L \sum{pq} g{pq}^{(\ell)} {\langle np nq \rangle}\ell ) The subscript ( \ell ) indicates the expectation value is taken after applying ( U_\ell ).

5. Key Parameters and Specifications

- Key Metric: The number of term groupings, L, which scales as O(N) for arbitrary basis sets [5].

- Advantages: This method also inherently mitigates readout error by transforming the measurement of non-local Pauli strings (via Jordan-Wigner transformation) into the measurement of local occupation numbers ( n_p ), which are less susceptible to correlated readout errors [5].

Protocol 2: Integrated Error Mitigation via Quantum Detector Tomography

This protocol runs alongside quantum chemistry algorithms to characterize and correct readout noise, which is a major source of estimation bias [10].

1. Primary Objective To reduce systematic bias in energy estimation caused by noisy quantum measurements by characterizing the noisy measurement process and constructing an unbiased estimator.

2. Experimental Workflow The integrated QDT process for error mitigation is shown below.

3. Reagents and Resources

- Informationally Complete (IC) Measurement Set: A pre-defined set of measurements that fully characterizes the quantum state.

- Calibrated Quantum Hardware: The same device used for the main experiment.

4. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Step 1 — Parallel Circuit Execution: Interleave circuits for Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) with the primary chemistry circuits (e.g., those from Protocol 1) during the same hardware execution batch. This is crucial for capturing the same noise environment.

- Step 2 — Data Collection: For the QDT circuits, collect measurement outcomes (bitstrings) that characterize the processor's response to a complete set of input states.

- Step 3 — Tomographic Reconstruction: Classically process the QDT data to reconstruct the Positive Operator-Valued Measure (POVM) that describes the noisy measurement process of the device.

- Step 4 — Unbiased Estimation: Use the reconstructed noisy POVM to build a classical estimator that is unbiased for the intended, noiseless observable. Apply this estimator to the data from the primary chemistry circuits.

5. Key Parameters and Specifications

- Key Metric: Reduction in absolute error (bias) of the estimated energy.

- Experimental Validation: In one implementation, this technique reduced the absolute error in the energy estimation of an 8-qubit BODIPY molecule Hamiltonian from an initial 1-5% down to 0.16% [10].

- Integration: This protocol is compatible with and enhances other techniques, such as the locally biased random measurements discussed in Protocol 3.

Protocol 3: Blended Scheduling for Temporal Noise Mitigation

Temporal noise, caused by parameter drift in hardware, can be mitigated by ensuring that different measurements are averaged over the same noise profile.

1. Primary Objective To average the effects of slow temporal noise (drift) across all terms of a Hamiltonian, ensuring that the final energy estimate is not skewed by noise that correlates with the timing of specific circuit executions.

2. Experimental Workflow Blended scheduling interleaves circuits for different measurements over time.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Step 1 — Circuit Batching: Compile all circuits required for the experiment, including those for different Hamiltonian terms (e.g., H1, H2 for different electronic states) and for QDT.

- Step 2 — Schedule Generation: Instead of executing all shots for one circuit before moving to the next, generate a schedule that interleaves the execution of all circuits in a looped fashion.

- Step 3 — Data Aggregation: After execution, aggregate the results by circuit type for analysis. Because each circuit type was executed repeatedly over the total time window, their results will reflect the average temporal noise over that period.

4. Key Parameters and Specifications

- Application: This technique is particularly critical for algorithms like ΔADAPT-VQE, which estimate energy gaps between electronic states (e.g., S0, S1, T1), as it ensures any temporal noise affects all energies homogeneously, preserving the accuracy of the gap [10].

Protocol 4: Locally Biased Random Measurements for Shot Reduction

This protocol reduces the number of shots required to reach a target precision by intelligently allocating more shots to measurement settings that have a larger impact on the final energy estimate.

1. Primary Objective To minimize the total number of shots required to estimate the energy to a given precision by prioritizing informative measurement settings, leveraging the classical shadows framework.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Step 1 — Initial Uniform Sampling: Begin by collecting a small number of shots using a uniform distribution over the informationally complete set of measurement settings (e.g., random Clifford bases).

- Step 2 — Classical Estimation of Influence: Use the initial data to compute a rough estimate of the energy and, more importantly, to identify which measurement settings contribute most significantly to the variance of the estimator.

- Step 3 — Biased Sampling: Allocate subsequent shots non-uniformly, favoring the high-influence settings identified in Step 2.

- Step 4 — Iteration (Optional): Repeat steps 2 and 3 to further refine the shot allocation.

3. Key Parameters and Specifications

- Key Metric: Reduction in the total number of shots (shot overhead) compared to uniform sampling.

- Compatibility: This strategy maintains the informationally complete nature of the measurements, allowing it to be seamlessly combined with Quantum Detector Tomography (Protocol 2) for joint shot reduction and error mitigation [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Noise-Resilient Quantum Chemistry Measurements

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Basis Rotation Grouping Algorithm | Classical pre-processing that factorizes the Hamiltonian into O(N) unitary groupings [5]. | Core strategy for reducing circuit overhead in measuring molecular energies. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | A calibration technique that characterizes the actual POVM of a quantum device's measurement apparatus [10]. | Mitigating readout error bias in energy estimation; used in Protocol 2. |

| Classical Shadows Framework | A formalism for using random measurements to predict many properties of a quantum state [10]. | Enables locally biased random measurements for shot reduction (Protocol 4). |

| Blended Scheduler | A software tool that interleaves the execution of different quantum circuits over time. | Mitigating temporal noise by ensuring all measurements experience average drift (Protocol 3). |

| Informationally Complete (IC) POVM | A set of measurement operators that spans the space of quantum observables. | Prerequisite for both the classical shadows and QDT protocols [10]. |

| Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) Ansatz | A parametrized quantum circuit ansatz inspired by classical computational chemistry. | Preparing trial molecular wavefunctions (e.g., Hartree-Fock, UCCSD) for energy evaluation [7]. |

| PfDHODH-IN-1 | PfDHODH-IN-1, CAS:1148125-81-8, MF:C14H11F3N2O2, MW:296.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Methoxybenzoic Acid | 4-Methoxybenzoic Acid, CAS:1335-08-6, MF:C8H8O3, MW:152.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implementing Basis Rotation Grouping: From Theory to Quantum Circuits

Hamiltonian Decomposition into Single-Particle Basis Rotations

The electronic structure Hamiltonian is a fundamental component in quantum simulations for chemistry, dictating the energy and properties of molecular systems. For near-term quantum devices, efficiently measuring this Hamiltonian's expectation value is a significant challenge due to noise constraints and limited quantum resources. The technique of Hamiltonian decomposition into single-particle basis rotations provides a powerful framework for addressing these challenges. This method leverages unitary transformations to reframe the Hamiltonian into a more measurement-friendly form, substantially reducing the number of unique measurement configurations required and enhancing resilience to readout errors [5].

Traditional Hamiltonian averaging approaches require measuring a number of terms that grows rapidly with system size, often becoming prohibitive for larger molecules. The decomposition strategy transforms this problem by exploiting mathematical structure within the two-electron integral tensor, allowing for a more compact representation. When combined with error mitigation techniques, this approach enables more accurate quantum chemistry calculations on current noisy quantum hardware, facilitating advancements in drug development and materials science where understanding electronic behavior is critical [5].

Theoretical Foundation

Mathematical Formulation of the Decomposition

The electronic structure Hamiltonian in second quantization can be expressed in a factorized form that enables efficient measurement [5]:

[H = U{0}\left(\sum{p}g{p}n{p}\right)U{0}^{\dagger} + \sum{\ell=1}^{L}U{\ell}\left(\sum{pq}g{pq}^{(\ell)}n{p}n{q}\right)U{\ell}^{\dagger}]

where:

- (g{p}) and (g{pq}^{(\ell)}) are scalar coefficients obtained from tensor factorization

- (n{p} = a{p}^{\dagger}a_{p}) is the number operator for orbital (p)

- (U_{\ell}) are unitary operators implementing single-particle basis rotations

- (L) represents the number of term groupings, which scales as (O(N)) for arbitrary basis quantum chemistry

The unitary basis rotation operators are defined as [5]: [U = \exp\left(\sum{pq}\kappa{pq}a{p}^{\dagger}a{q}\right),\quad Ua{p}^{\dagger}U^{\dagger} = \sum{q}[e^{\kappa}]{pq}a{q}^{\dagger}] where (\kappa) is an anti-Hermitian matrix characterizing the basis transformation.

Connection to Measurement Efficiency

This decomposition dramatically reduces the number of distinct measurement configurations compared to naive Pauli word measurements. After applying each basis rotation (U{\ell}), all necessary number operator expectation values (\langle n{p}\rangle) and (\langle n{p}n{q}\rangle) can be measured simultaneously in the rotated basis. The energy expectation value is then reconstructed as [5]: [\langle H\rangle = \sum{p}g{p}{\langle n{p}\rangle}{0} + \sum{\ell=1}^{L}\sum{pq}g{pq}^{(\ell)}{\langle n{p}n{q}\rangle}{\ell}]

This approach provides a cubic reduction in term groupings over prior state-of-the-art methods, enabling measurement times three orders of magnitude smaller for the largest systems considered [5].

Experimental Protocols

Basis Rotation Grouping Measurement Protocol

Objective: Estimate the ground-state energy expectation value (\langle H\rangle) using Hamiltonian decomposition with enhanced efficiency and noise resilience.

Pre-experiment Preparation:

- Hamiltonian Decomposition:

- Perform eigendecomposition of the two-electron integral tensor

- Truncate small eigenvalues to obtain controllable approximation (optional)

- Obtain coefficients (g{p}), (g{pq}^{(\ell)}), and basis rotation parameters (\kappa^{(\ell)})

- Quantum Circuit Compilation:

- Compile each (U_{\ell}) into native gate operations

- Implement number operator measurements in rotated basis

Procedure:

- Initial State Preparation:

- Prepare reference state (|\psi(\theta)\rangle) using parameterized quantum circuit

- For VQE, use classically optimized parameters (\theta^{*})

Measure Diagonal Terms in Original Basis:

- Apply identity operation (U_{0}) (no basis rotation)

- Measure all (\langle n{p}\rangle{0}) expectation values

- Repeat for sufficient measurements to achieve target precision

Measure Two-Body Terms in Rotated Bases:

- For each (\ell = 1) to (L):

- Apply basis rotation (U{\ell}) to the prepared state

- Simultaneously measure all (\langle n{p}n{q}\rangle{\ell}) expectation values

- Repeat for sufficient measurements to achieve target precision

- For each (\ell = 1) to (L):

Classical Post-processing:

- Combine results according to energy reconstruction formula

- Apply error mitigation techniques if implemented

Validation:

- Compare with classical computational chemistry methods where feasible

- Verify consistency across different measurement runs

- Check convergence with increasing measurement samples

RESET Protocol for Noise Resilience

Objective: Mitigate noise in quantum computations using nonunital noise characteristics without mid-circuit measurements [15].

Background: Nonunital noise (e.g., amplitude damping) has directional bias that can be harnessed for error suppression, unlike unital noise that completely randomizes states [15].

Procedure:

- Passive Cooling Phase:

- Randomize ancilla qubits

- Expose to nonunital noise, driving toward partially polarized state

Algorithmic Compression:

- Apply compound quantum compressor circuit

- Concentrate polarization into subset of qubits

Qubit Swapping:

- Replace "dirty" computational qubits with purified ancillas

- Refresh system for continued computation

Applications:

- Extends computation depth without traditional error correction

- Enables measurement-free fault tolerance

- Particularly valuable for platforms with challenging measurement implementation

Data Presentation

Performance Comparison of Measurement Strategies

Table 1: Comparison of Hamiltonian measurement strategies for quantum chemistry simulations

| Method | Term Groupings | Measurement Scaling | Error Resilience | Circuit Depth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive Pauli Measurement | (O(N^4)) | Large constant prefactor | Low | Shallow |

| Prior State-of-the-Art | (O(N^3)) | Improved scaling | Moderate | Shallow |

| Basis Rotation Grouping | (O(N)) [5] | 3-order magnitude reduction [5] | High (enables postselection) | Linear [5] |

| RESET Protocol | Varies | Polylogarithmic overhead [15] | Very High (harnesses noise) | Moderate to High [15] |

Resource Requirements for Molecular Systems

Table 2: Estimated measurement resources for molecular systems using basis rotation grouping

| System Description | Qubits | Term Groupings | Measurement Reduction | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small organic molecule | 16-20 | Linear in qubits [5] | ~100x | Enables error mitigation via postselection |

| Drug-like fragment | 24-32 | Linear in qubits [5] | ~300x | Reduced sensitivity to readout errors |

| Catalytic complex | 40-50 | Linear in qubits [5] | ~1000x | Measurement of local operators only |

Visualization of Workflows

Basis Rotation Grouping Measurement Workflow

Diagram 1: Basis rotation grouping workflow for efficient Hamiltonian measurement

RESET Protocol for Noise Resilience

Diagram 2: RESET protocol leveraging nonunital noise for error suppression

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Chemistry Simulations

Table 3: Essential components for implementing Hamiltonian decomposition protocols

| Resource | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tensor Factorization Algorithm | Decomposes two-electron integrals | Use density fitting or eigendecomposition; discard small eigenvalues for approximation [5] |

| Basis Rotation Circuits | Implements unitary transformations (U_\ell) | Compile using Givens rotation networks; depth scales linearly with qubit count [5] |

| Number Operator Measurement | Measures (\langle np \rangle) and (\langle np n_q \rangle) in rotated basis | Implement via Pauli-Z measurements after basis change [5] |

| Nonunital Noise Characterization | Identifies amplitude damping channels in hardware | Essential for RESET protocol; requires device-specific noise modeling [15] |

| Compound Quantum Compressor | Concentrates polarization in ancilla systems | Key component of RESET protocol; requires specialized circuit design [15] |

| Symmetry Postselection | Projects onto correct particle number and Sz sectors | Enabled by basis rotation grouping; removes wrong symmetry components [5] |

| Sodium Gluconate | Sodium Gluconate, CAS:14906-97-9, MF:C6H11NaO7, MW:218.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| BIM-23190 | BIM-23190, CAS:182153-96-4, MF:C57H79N13O12S2, MW:1202.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Hamiltonian decomposition into single-particle basis rotations represents a significant advancement for quantum computational chemistry on near-term devices. By transforming the measurement problem into a series of efficient basis rotations, this approach achieves substantial reductions in measurement overhead while enhancing resilience to readout errors. The combination of mathematical tensor factorization with quantum basis rotations enables chemists and drug development researchers to extract meaningful electronic structure information from current noisy quantum processors.

The protocols outlined—particularly when combined with noise-aware strategies like the RESET protocol—provide a practical pathway toward simulating larger molecular systems than previously possible. As quantum hardware continues to advance, these techniques will play an increasingly important role in bridging the gap between theoretical quantum advantage and practical applications in pharmaceutical research and materials design.

Step-by-Step Guide to Diagonalizing Two-Electron Integral Tensors

In computational chemistry and quantum simulation, the two-electron integral tensor is a fundamental component of the electronic structure Hamiltonian, representing the electron-electron repulsion. Its formal definition in terms of atomic orbitals is given by:

[ (\mu\nu|\lambda\sigma) = \int \int \phi{\mu}(\mathbf{r}1)\phi{\nu}(\mathbf{r}1) \frac{1}{|\mathbf{r}1 - \mathbf{r}2|} \phi{\lambda}(\mathbf{r}2)\phi{\sigma}(\mathbf{r}2) d\mathbf{r}1 d\mathbf{r}2 ]

where ( \phi ) represents the atomic orbital basis functions and the Greek indices denote specific atomic orbitals [16]. This fourth-order tensor exhibits significant mathematical structure that can be exploited for computational efficiency. As system size increases, this tensor becomes sparse, enabling advanced matrix reordering and decomposition techniques that facilitate low-rank representations [16]. Within the context of basis rotation grouping for quantum chemistry simulations, diagonalizing or block-diagonalizing this tensor is a crucial preprocessing step that dramatically reduces quantum measurement costs and enhances noise resilience on near-term quantum hardware [5].

The diagonalization process transforms the electron repulsion integral tensor into a more compact form through tensor factorization, which can reduce the number of term groupings in quantum measurements by up to three orders of magnitude compared to naive approaches [5]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive protocol for diagonalizing two-electron integral tensors, with specific application to enabling efficient, noise-resilient quantum computations for chemical systems.

Theoretical Foundation

Tensor Factorization Framework

The two-electron integral tensor can be factorized using a double factorization approach that begins with an eigendecomposition of the two-electron integral tensor [5]. This decomposition enables a controllable approximation to the original Hamiltonian by discarding small eigenvalues, ultimately yielding a factorized form of the electronic structure Hamiltonian:

[ H = U0 \left( \sump gp np \right) U0^\dagger + \sum{\ell=1}^L U\ell \left( \sum{pq} g{pq}^{(\ell)} np nq \right) U\ell^\dagger ]

where ( gp ) and ( g{pq}^{(\ell)} ) are scalar coefficients, ( np = ap^\dagger ap ) is the number operator, and the ( U\ell ) are unitary basis rotation operators [5]. This factorization represents the Hamiltonian as a sum of diagonal one-body and two-body operators conjugated by unitary transformations, which is precisely the form exploited in basis rotation grouping for efficient quantum measurements.

The number of terms ( L ) in this decomposition scales as ( O(N) ) for arbitrary basis quantum chemistry, with specific basis sets existing where ( L = 1 ), such as the plane wave dual basis [5]. For quantum computational applications, this factorization facilitates measurement of all ( \langle np \rangle ) and ( \langle np nq \rangle ) expectation values in rotated bases defined by the ( U\ell ) operators, dramatically reducing measurement overhead.

Mathematical Formulation of Diagonalization

The diagonalization process begins with recognizing that the two-electron integral tensor, while formally a fourth-order tensor, can be represented as a matrix for decomposition purposes. The Coulomb-type integral tensor ( J ) and its exchange-type counterpart ( K ) are both symmetric with respect to basis function pairs and can be decomposed using similar mathematical approaches [16].

The core mathematical operation involves applying a sequence of transformations to obtain a bandwidth-reduced form of the tensor. If the graph corresponding to the two-electron integral tensor is disconnected, this process can yield a block-diagonal form, where each block can be separately decomposed [16]. The key insight is that for sparse tensors, an optimal reordering of columns and rows can significantly reduce the computational resources required for factorization.

Table 1: Key Mathematical Components in Two-Electron Integral Tensor Diagonalization

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Role in Diagonalization | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-electron Integral Tensor | ( (\mu\nu | \lambda\sigma) ) or ( \langle\mu\lambda | \nu\sigma\rangle ) | Initial fourth-order tensor representing electron repulsion |

| Permutation Matrix | ( P ) (from RCM algorithm) | Reorders tensor indices for bandwidth reduction | ||

| Cholesky Vectors | ( L^{(k)} ) where ( J \approx \sum_k L^{(k)} (L^{(k)})^T ) | Low-rank representation of diagonal blocks | ||

| Unitary Rotation Operators | ( U\ell = \exp\left(\sum{pq} \kappa{pq}^{(\ell)} ap^\dagger a_q\right) ) | Basis transformations for factorized measurement |

Experimental Protocol

Complete Diagonalization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for diagonalizing two-electron integral tensors, from initial integral evaluation to final factorized form for quantum measurements:

Step-by-Step Implementation Protocol

Step 1: Initial Two-Electron Integral Evaluation

Begin by computing the primitive two-electron integrals in the atomic orbital basis. For a system with K primitive basis functions, this generates a 4D tensor of dimensions K×K×K×K. For the specific case of H₂ in an STO-3G basis set, this involves 6 primitive Gaussians per atom, resulting in a 12×12×12×12 primitive integral tensor [17].

Implementation Details:

- Evaluate primitive integrals: ( [\mathbf{ab}|\mathbf{cd}] ) for all primitive Gaussian functions

- The transformation from primitive to contracted integrals follows: [ (\mathbf{ab}|\mathbf{cd}) = \sum{i=1}^{K} \sum{j=1}^{K} \sum{k=1}^{K} \sum{l=1}^{K} D{\mathbf{a}i} D{\mathbf{b}j} D{\mathbf{c}k} D{\mathbf{d}l} [\mathbf{ab}|\mathbf{cd}] ] where ( D ) contains the contraction coefficients [17]

Step 2: Basis Transformation and Tensor Reshaping

Transform the integrals from the primitive Gaussian basis to the atomic orbital basis using coefficient matrices. For efficient computation, reshape the 4D tensor into a 2D matrix representation. For a system with N atomic orbitals, the 4D tensor of size N×N×N×N is reshaped to an N²×N² matrix [17].

Implementation Code Concept:

Step 3: Reverse Cuthill-McKee (RCM) Ordering

Apply the RCM algorithm to the absolute values of the integral matrix to find a permutation that reduces bandwidth. The RCM algorithm is a heuristic method that reduces the matrix bandwidth by reordering rows and columns based on graph connectivity [16].

Algorithmic Purpose:

- Input: N²×N² matrix representation of two-electron integrals

- Output: Permutation vector P that minimizes matrix bandwidth

- If the graph corresponding to the integral tensor is disconnected, this transformation yields a block-diagonal form

Step 4: Block Identification and Cholesky Decomposition

Identify the block-diagonal structure revealed by the RCM reordering. Apply pivoted Cholesky decomposition to each diagonal block separately, which represents the incomplete Cholesky decomposition approach [16].

Mathematical Formulation: For each diagonal block Bk: [ Bk \approx Lk Lk^T ] where L_k contains the Cholesky vectors for block k.

The accuracy of the decomposition can be controlled to arbitrary precision, with the number of Cholesky vectors determining the approximation quality [16].

Step 5: Double Factorization for Quantum Applications

For quantum computational applications, perform a double factorization beginning with either a Cholesky decomposition or eigendecomposition of the two-electron integral tensor [5]. This second factorization enables the compact form used in basis rotation grouping.

Implementation Details:

- Begin with either Cholesky vectors or eigencomponents from the previous step

- Perform additional factorization to obtain the form: ( \sum{\ell=1}^L U\ell (\sum{pq} g{pq}^{(\ell)} np nq) U_\ell^\dagger )

- The number of terms L typically scales as O(N) for molecular systems

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Two-Electron Integral Diagonalization and Quantum Simulation