Beyond the Hype: Confronting ADAPT-VQE Limitations and Breakthroughs in the NISQ Era

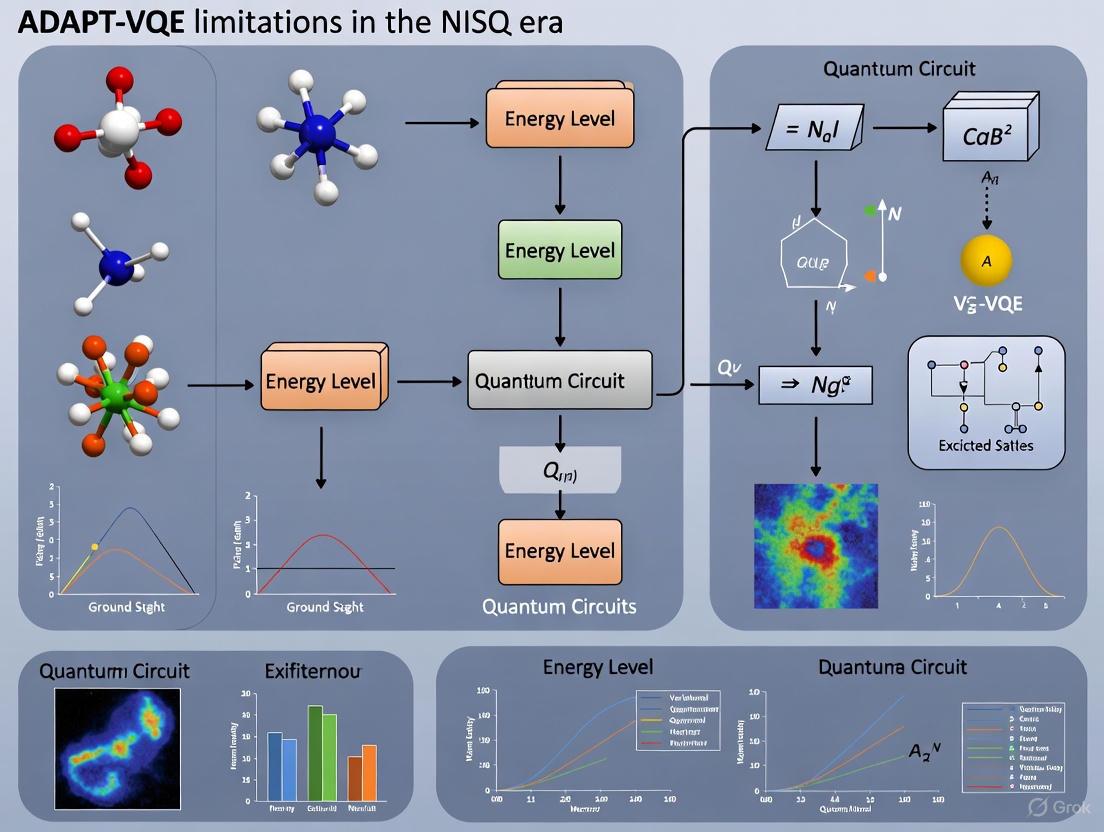

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) for quantum chemistry simulations in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era.

Beyond the Hype: Confronting ADAPT-VQE Limitations and Breakthroughs in the NISQ Era

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) for quantum chemistry simulations in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of ADAPT-VQE, methodological innovations overcoming current hardware constraints, practical optimization strategies for implementation, and validation through comparative benchmarks. Drawing on the latest research, we outline a path toward chemically accurate molecular simulations and assess the prospects for quantum advantage in biomedical research.

The Quantum Chemistry Promise: Why ADAPT-VQE Matters for Molecular Simulation

Variational Quantum Eigensolvers (VQEs) represent a class of hybrid quantum-classical algorithms designed to compute molecular energies on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices by leveraging the variational principle [1]. In traditional VQE implementations, a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) of fixed structure is used to prepare a trial wavefunction, whose energy expectation value is minimized via classical optimization [2]. While hardware-efficient ansätze offer reduced circuit depth, they often lack chemical intuition and face challenges with optimization barriers such as barren plateaus [3]. Chemically-inspired ansätze, like Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC), provide physical grounding but typically generate deep quantum circuits prohibitive for current hardware [4]. Furthermore, fixed ansätze are inherently system-agnostic, often containing redundant operators that unnecessarily increase circuit depth and variational parameters—a significant problem for noise-limited NISQ devices [2]. This landscape of limitations prompted the development of adaptive, problem-tailored approaches, culminating in the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) algorithm [5].

The ADAPT-VQE Algorithm: Core Principles and Methodology

ADAPT-VQE represents a paradigm shift from fixed ansätze to dynamically constructed, system-specific quantum circuits. Rather than employing a predetermined circuit structure, ADAPT-VQE grows the ansatz iteratively by selecting operators from a predefined pool based on their potential to lower the energy [5]. The algorithm's mathematical foundation lies in the iterative construction of a parameterized wavefunction. At iteration m, the ansatz takes the form: |Ψ^(m)⟩ = âˆ{k=1}^m exp[θk Ï„k] |Ψ0⟩ where Ï„k are anti-Hermitian operators from the pool, and θk are variational parameters [4].

The ADAPT-VQE protocol implements a systematic workflow:

Algorithm 1: ADAPT-VQE

- Initialization: Begin with a reference state (usually Hartree-Fock, |Ψ0⟩) and predefine an operator pool {τi} (e.g., UCCSD pool).

- Gradient Evaluation: For each operator in the pool, measure the energy gradient: ∂E/∂θi = ⟨Ψ|[H, τi]|Ψ⟩.

- Operator Selection: Identify the operator Ï„* with the largest gradient magnitude.

- Ansatz Expansion: Append exp[θ{new} τ*] to the current circuit, initializing θ{new} = 0.

- Parameter Optimization: Perform a classical optimization to minimize energy E(θ1, ..., θm) with respect to all parameters.

- Convergence Check: Repeat steps 2-5 until the gradient norm falls below a predetermined threshold [5] [2].

This iterative, greedy approach ensures that each added operator provides the maximum possible energy descent at that step, creating a compact, problem-tailored ansatz [6].

Table 1: Key Components of the ADAPT-VQE Framework

| Component | Description | Common Implementations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference State | Initial wavefunction | Hartree-Fock state [1] | ||

| Operator Pool | Set of available operators | UCCSD, qubit excitations [5] | ||

| Selection Metric | Criterion for operator choice | Gradient magnitude ⟨Ψ | [H, τ_i] | Ψ⟩ [2] |

| Optimizer | Classical minimization method | BFGS, COBYLA [1] [7] | ||

| Convergence | Termination criterion | Gradient norm < ε or energy change < δ [5] |

Advantages Over Traditional VQE: Mitigating NISQ Limitations

ADAPT-VQE addresses several fundamental challenges that plague fixed-ansatz VQEs:

Circuit Compactness and System-Tailored Design

By selectively adding only the most relevant operators, ADAPT-VQE generates significantly shorter circuits compared to fixed UCCSD ansätze [4]. This compactness reduces exposure to quantum noise—a critical advantage on NISQ hardware. Numerical simulations demonstrate that ADAPT-VQE can achieve chemical accuracy with up to 90% fewer operators than fixed UCCSD for simple molecules like H₂ and LiH [5].

Mitigation of Barren Plateaus and Optimization Traps

The adaptive construction provides an intelligent parameter initialization strategy that avoids random initialization in flat energy landscapes (barren plateaus) [5]. Even when converging to local minima at intermediate steps, the algorithm can continue "burrowing" toward the exact solution by adding more operators, which preferentially deepens the occupied minimum [5]. This systematic growth makes ADAPT-VQE largely immune to the barren plateau problem that plagues many fixed ansätze [5].

Robustness to Statistical Noise

The greedy nature of operator selection provides inherent resilience to statistical sampling noise. Even with noisy gradient estimations, the algorithm tends to select operators that improve the wavefunction [2]. Implementations on actual quantum hardware (25-qubit error-mitigated devices) have successfully generated parameterized circuits that yield favorable ground-state approximations despite hardware noise producing inaccurate absolute energies [2].

Diagram 1: ADAPT-VQE Algorithm Workflow. The iterative process dynamically constructs an efficient, problem-specific ansatz.

Implementation Considerations and Practical Challenges

Despite its theoretical advantages, practical implementation of ADAPT-VQE presents significant challenges, primarily related to quantum measurement overhead. The operator selection step requires evaluating gradients for all operators in the pool, potentially demanding tens of thousands of noisy quantum measurements [2]. Each iteration introduces additional parameters to optimize, creating a high-dimensional, noisy cost function that challenges classical optimizers [2].

Several strategies have emerged to address these limitations:

Measurement Reduction Techniques: Recent advances include reusing Pauli measurement outcomes from VQE optimization in subsequent gradient evaluations, reducing average shot usage to approximately 32% of naive approaches [3]. Variance-based shot allocation strategies applied to both Hamiltonian and gradient measurements can reduce shot requirements by up to 51% while maintaining accuracy [3].

Classical Pre-optimization: The Sparse Wavefunction Circuit Solver (SWCS) approach performs approximate ADAPT-VQE optimizations on classical computers by truncating the wavefunction, identifying compact ansätze for later quantum execution [4]. This method has been applied to systems with up to 52 spin orbitals, bridging classical and quantum resources [4].

Hamiltonian Simplification: The active space approximation reduces computational complexity by focusing on chemically relevant orbitals, enabling applications to molecules like benzene on current quantum hardware [7].

Table 2: ADAPT-VQE Performance Across Molecular Systems

| Molecule | Qubits | Key Result | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | 4 | Robust convergence to chemical accuracy | Noiseless simulation [1] |

| Hâ‚‚O | 12 | Stagnation above chemical accuracy with measurement noise | Noisy emulation (10,000 shots) [2] |

| LiH | 12 | Gradient-based optimization superior to gradient-free | Classical simulation [1] |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | 38.59% shot reduction with measurement reuse | Shot-efficient protocol [3] |

| Benzene | 24-36 | Hardware noise prevents accurate energy evaluation | IBM quantum computer [7] |

| 25-body Ising | 25 | Favorable ground-state approximation despite hardware noise | Error-mitigated QPU execution [2] |

Research Reagents: Essential Components for ADAPT-VQE Implementation

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for ADAPT-VQE Experiments

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| UCCSD Operator Pool | Provides fundamental building blocks for ansatz construction | Fermionic excitation operators: {Ï„i^a, Ï„{ij}^{ab}} [4] |

| Qubit Mappings | Transforms fermionic operators to qubit representations | Jordan-Wigner, parity transformations [1] [8] |

| Active Space Approximation | Reduces problem size by focusing on relevant orbitals | Selection of active electrons and orbitals (e.g., 2e/2o for prodrug study) [8] [7] |

| Classical Optimizers | Minimizes energy with respect to circuit parameters | BFGS (noiseless), COBYLA (noisy environments) [5] [7] |

| Error Mitigation | Counteracts hardware noise effects | Readout error mitigation, error extrapolation [8] |

| Shot Allocation Strategies | Optimizes quantum measurement budget | Variance-based allocation, Pauli measurement reuse [3] |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Molecular Simulation

ADAPT-VQE has demonstrated promising applications in real-world drug discovery challenges, particularly through hybrid quantum-classical pipelines. In prodrug activation studies, researchers have employed ADAPT-VQE to compute Gibbs free energy profiles for carbon-carbon bond cleavage in β-lapachone derivatives—a critical step in cancer-specific drug targeting [8]. By combining active space approximation (2 electrons/2 orbitals) with error-mitigated VQE executions on superconducting quantum processors, these studies achieved chemically relevant accuracy for reaction barrier predictions [8].

Another significant application involves simulating covalent inhibition of the KRAS G12C protein, a prominent cancer drug target [8]. Quantum computing-enhanced QM/MM (Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics) simulations provide detailed insights into drug-target interactions, particularly the covalent bonding mechanisms that enhance therapeutic specificity [8]. These implementations demonstrate ADAPT-VQE's potential in addressing meaningful biological problems despite current hardware limitations.

Diagram 2: Drug Discovery Application Pipeline. ADAPT-VQE integrates into a broader workflow for practical pharmaceutical applications.

Current Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite its promising attributes, ADAPT-VQE faces significant challenges that currently prevent its widespread application on NISQ hardware. Hardware noise remains the primary obstacle, with quantum gate errors needing reduction by orders of magnitude before quantum advantage can be realized [7]. Even with sophisticated error mitigation, current quantum processors produce inaccurate absolute energies for complex molecules like benzene [7].

The measurement overhead problem, while improved through recent techniques, remains substantial for large molecular systems. The requirement to evaluate numerous observables for operator selection creates a scaling challenge that demands further innovation in measurement reduction strategies [3]. Additionally, the classical optimization component becomes increasingly difficult as the ansatz grows, with rough parameter landscapes complicating convergence [2].

Future research directions focus on several key areas: (1) developing more efficient measurement strategies that leverage classical shadows and machine learning approaches; (2) creating better error mitigation techniques tailored to adaptive algorithms; (3) optimizing operator pools for specific chemical systems to reduce search space; and (4) enhancing classical pre-optimization methods to minimize quantum resource requirements [4] [3]. As hardware improves and these algorithmic advances mature, ADAPT-VQE is positioned to become an essential tool for computational chemistry and drug discovery on increasingly capable quantum devices.

Quantum computing in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era represents a critical phase of development where available hardware possesses between 50 and 1000+ qubits but remains severely constrained by noise and limited connectivity [9]. These fundamental hardware limitations directly impact the performance and feasibility of quantum algorithms, particularly sophisticated variational approaches like the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE). Designed to simulate quantum systems with reduced circuit depth, ADAPT-VQE itself faces significant execution challenges on current NISQ devices [2] [10]. This technical analysis examines the core hardware constraints in the NISQ era, quantifying their specific impacts on algorithm performance and outlining experimental methodologies for benchmarking and resource estimation within the context of ADAPT-VQE research.

The performance of quantum algorithms is constrained by fundamental physical resources of the underlying hardware. These resources can be categorized into physical and logical types, both critically determining what computations are feasible in the NISQ era [9].

Table 1: Fundamental Quantum Hardware Resources and Current NISQ Limitations

| Resource Category | Specific Parameters | Description & Role in Algorithms | Current NISQ Limitations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Qubits | Qubit Count | Number of physical quantum bits; determines problem sizeä¸Šé™ [9]. | 50-1000+ qubits available, but quality varies significantly [9] [11]. | ||

| Qubit Quality/Error Rate | Probability of error per physical qubit operation [9]. | High error rates prevent commercially relevant applications [9]. | |||

| Coherence | T₠(Relaxation Time) | Time for a qubit to decay from | 1⟩ to | 0⟩ state [12]. | Limits circuit execution time (e.g., ~41.8 μs mean T₠on a 20-qubit chip) [12]. |

| T₂ (Dephasing Time) | Time for a qubit to lose its phase coherence [12]. | Typically shorter than T₠(e.g., ~3.2 μs mean T₂) [12]. | |||

| Gate Performance | Single-Qubit Gate Fidelity | Accuracy of single-qubit gate operations [12]. | Can exceed 99.8% on advanced platforms [12] [11]. | ||

| Two-Qubit Gate Fidelity | Accuracy of entangling gate operations [12]. | Approaching 99.9% for best superconducting qubits; ~98.6% median on a 20-qubit chip [12] [11]. | |||

| Connectivity | Qubit Topology | Arrangement and connectivity of qubits (e.g., square grid) [12]. | Limited connectivity requires SWAP networks, increasing circuit depth and error [12]. | ||

| Measurement | Readout Fidelity | Accuracy of final qubit state measurement [12]. | Measurement errors are significant (e.g., ~2.7% for | 0⟩, ~5.1% for | 1⟩) [12]. |

Impact of Hardware Limitations on ADAPT-VQE Performance

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm, while designed for efficiency, encounters multiple critical bottlenecks when deployed on real NISQ hardware. The algorithm's iterative structure—which involves repeated quantum circuit evaluations for operator selection and parameter optimization—makes it particularly vulnerable to hardware imperfections [2] [10].

Measurement Overhead and Shot Requirements

A primary challenge is the massive quantum measurement overhead (shot requirements). The standard ADAPT-VQE protocol requires estimating gradients for every operator in a pool during each iteration, demanding tens of thousands of noisy measurements [2] [13]. This overhead arises because the operator selection criterion requires calculating the gradient of the energy expectation value for each operator in the pool, defined as: $$\mathscr{U}^* = \underset{\mathscr{U} \in \mathbb{U}}{\text{argmax}} \left| \frac{d}{d\theta} \Big \langle \Psi^{(m-1)} \left| \mathscr{U}(\theta)^\dagger \widehat{H} \mathscr{U}(\theta) \right| \Psi^{(m-1)} \Big \rangle \Big \vert _{\theta=0} \right|$$ This process must be repeated every iteration, creating a prohibitive sampling burden on real devices where each measurement is costly and noisy [2]. Recent research focuses on shot-efficient strategies like reusing Pauli measurements between optimization and selection steps and employing variance-based shot allocation to distribute measurement resources optimally [13].

Noise-Induced Optimization Failures

Quantum hardware noise fundamentally disrupts the classical optimization process essential to ADAPT-VQE. Noise transforms the optimization landscape from smooth to noisy and non-convex, creating challenges like barren plateaus where gradients vanish exponentially with system size [2] [14]. As demonstrated in experiments, introducing statistical noise (simulating 10,000 shots on an emulator) causes ADAPT-VQE to stagnate well above chemical accuracy for molecules like Hâ‚‚O and LiH, whereas noiseless simulations recover exact energies [2]. This noise sensitivity means that even with algorithmic improvements, current hardware limitations prevent meaningful chemical accuracy in molecular energy calculations [10].

Circuit Depth and Decoherence Constraints

The adaptive nature of ADAPT-VQE leads to progressively deeper quantum circuits with each iteration. This increasing circuit depth directly conflicts with the limited coherence times (T₠and T₂) of NISQ hardware [9] [12]. When the total execution time of a quantum circuit exceeds the coherence time, quantum information is lost through decoherence, rendering results unreliable. This limitation is particularly acute for complex molecules requiring deep ansätze, effectively placing a hard upper bound on the feasible number of ADAPT-VQE iterations and the complexity of treatable systems [10].

Diagram 1: ADAPT-VQE workflow with noise impact. The iterative process is vulnerable to hardware noise at critical stages of gradient measurement and parameter optimization, leading to potential failures.

Benchmarking and Noise Modeling: Experimental Protocols

To systematically evaluate hardware limitations, researchers employ rigorous benchmarking and noise modeling protocols. These methodologies are essential for predicting algorithm performance and guiding hardware development.

Quantum Volume and Comprehensive Benchmarking

Quantum Volume (QV) serves as a holistic benchmark measuring a quantum processor's overall capability by considering gate fidelity, qubit connectivity, and circuit depth [15]. Additional metrics like Circuit Layer Operations Per Second (CLOPS) assess computational throughput, while dedicated characterization protocols measure specific parameters [15]:

- Randomized Benchmarking (RB): Characterizes average gate fidelities by applying random gate sequences and measuring survival probability [12].

- Coherence Time Measurements: Directly measure Tâ‚ and Tâ‚‚ times using specialized experiments [12].

- Gate Set Tomography: Provides complete characterization of quantum operations but is resource-intensive [12].

Constructing Accurate Noise Models

Advanced noise models create digital twins of quantum processors by integrating measured parameters into comprehensive error models. The typical workflow involves [12]:

- Parameter Extraction: Measuring fidelity, coherence times, and error rates for each qubit and gate.

- Model Construction: Implementing error channels (amplitude damping, phase damping, depolarizing noise) that reflect physical noise processes.

- Validation: Comparing simulation results with actual hardware outputs across benchmark circuits.

These models accurately predict how arbitrary quantum algorithms will execute on target hardware, enabling performance prediction and resource estimation without costly device access [12].

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Hardware Benchmarking and Noise Characterization

| Protocol Category | Specific Methods | Measured Parameters | Role in ADAPT-VQE Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware Characterization | Randomized Benchmarking (RB) | Average Gate Fidelities (Single- and Two-Qubit) [12] | Determines maximum feasible ansatz depth and complexity. |

| Coherence Time Measurements | Tâ‚ (Relaxation) and Tâ‚‚ (Dephasing) Times [12] | Sets upper bound on total circuit execution time. | |

| Hamiltonian Tomography | Native Gate Set Identification [12] | Informs efficient compilation and operator pool design. | |

| Algorithm Performance Benchmarking | Quantum Volume (QV) | Overall Processor Capability [15] | Provides cross-platform comparison of hardware suitability. |

| Circuit Layer Operations Per Second (CLOPS) | Computational Throughput [15] | Estimates total runtime for multi-iteration ADAPT-VQE. | |

| Noise Simulation & Mitigation | Digital Twin Simulation | Full System Performance Prediction [12] | Predicts ADAPT-VQE performance on specific hardware. |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | Error Mitigation via Post-Processing [11] | Improves energy estimation from noisy measurements. |

Successfully executing ADAPT-VQE research requires both hardware access and specialized software tools for simulation, optimization, and error mitigation.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for ADAPT-VQE Experimentation

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Frameworks | Function & Application | Relevance to ADAPT-VQE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Hardware Platforms | Superconducting QPUs (IBM, Google) | Physical quantum computation with 100-1000+ qubits [12] [11] | Target deployment platform for algorithm testing. |

| Trapped Ion QPUs (IonQ) | High-fidelity qubits with all-to-all connectivity [11] | Alternative platform with different noise characteristics. | |

| Software Frameworks | Qiskit (IBM), Cirq (Google) | Quantum circuit design, compilation, and execution [12] | Standard toolkits for algorithm implementation. |

| TensorFlow Quantum, Pennylane | Hybrid quantum-classical optimization [14] | Manages classical optimization loop in VQEs. | |

| Specialized Prototypes | Qonscious Runtime Framework | Conditional execution based on dynamic resource evaluation [9] | Enables resource-aware adaptive algorithm execution. |

| Eviden Qaptiva Framework | High-performance noise simulation and benchmarking [12] | Creates digital twins for performance prediction. | |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | Infers noiseless results from noisy data [11] | Post-processing to improve energy estimation. |

| Probabilistic Error Cancellation | Corrects results using noise characterization data [11] | Active correction during computation. |

Diagram 2: Hybrid quantum-classical workflow for ADAPT-VQE. The algorithm relies on tight integration between classical computing resources (optimization, error mitigation) and quantum resources (ansatz execution, measurement).

The path toward practical quantum advantage using algorithms like ADAPT-VQE requires co-design between algorithmic improvements and hardware development. Current research focuses on shot-efficient measurement strategies [13], noise-resilient ansatz designs [2], and resource-aware runtime frameworks [9] to maximize what is possible within NISQ constraints. The ultimate solution, however, lies in the transition to Fault-Tolerant Application-Scale Quantum (FASQ) systems capable of meaningful error correction [11]. Until this transition occurs, understanding and strategically navigating the intricate landscape of hardware limitations remains essential for productive research in quantum computational chemistry and materials science.

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithm for molecular simulations on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. Unlike fixed-structure ansätze such as unitary coupled cluster (UCCSD), ADAPT-VQE iteratively constructs a problem-tailored quantum circuit by dynamically appending parameterized unitary operators selected from a predefined pool [5]. This adaptive construction offers significant advantages including reduced circuit depth, mitigation of barren plateaus, and systematic convergence toward accurate ground-state energies [3] [5]. However, these advantages come at a substantial cost: a dramatically increased quantum measurement overhead that presents a major bottleneck for practical implementations on current quantum hardware [3] [2].

The measurement overhead problem in ADAPT-VQE arises from two primary sources. First, the operator selection process at each iteration requires evaluating gradients with respect to all operators in the pool, necessitating extensive quantum measurements [3]. Second, the subsequent variational optimization of all parameters in the growing ansatz demands repeated energy evaluations [2]. Unlike conventional VQE with fixed ansätze, ADAPT-VQE incurs this substantial measurement cost repeatedly throughout its iterative circuit construction process. For complex molecular systems, this overhead can become prohibitive, potentially requiring millions of quantum measurements [16]. As we progress through the NISQ era, where quantum resources remain scarce and expensive, solving this measurement overhead problem becomes not merely beneficial but essential for realizing practical quantum advantage in computational chemistry and drug development applications.

Quantifying the Measurement Overhead Challenge

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm generates measurement overhead through two interconnected computational processes, each requiring extensive quantum measurements:

Gradient Evaluation for Operator Selection: At each iteration, the algorithm must identify the most promising operator to add to the growing ansatz. This selection is typically based on the gradient of the energy with respect to each operator in the pool [5]. Evaluating these gradients requires measuring the expectation values of commutators between the Hamiltonian and each pool operator [3]. For molecular systems, the operator pool can contain hundreds of elements, making this step particularly measurement-intensive.

Parameter Optimization Loop: After adding a new operator, all parameters in the ansatz must be re-optimized [2]. This variational optimization requires numerous evaluations of the energy expectation value, each demanding extensive sampling (shots) on quantum hardware to achieve sufficient precision, especially in the presence of noise.

Comparative Resource Requirements

Recent studies have quantified the substantial resource reductions achievable through optimized ADAPT-VQE implementations compared to earlier approaches. The following table summarizes these improvements for selected molecular systems:

Table 1: Measurement Overhead Reductions in ADAPT-VQE Implementations

| Molecule | Qubit Count | Original ADAPT-VQE | Optimized ADAPT-VQE | Reduction | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH | 12 | Baseline | 2% of original | 98% | [16] |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | Baseline | 0.4% of original | 99.6% | [16] |

| Hâ‚‚ | 4 | Uniform shot distribution | Variance-based allocation | 43.21% | [3] |

| LiH | 12 | Uniform shot distribution | Variance-based allocation | 51.23% | [3] |

| Hâ‚‚O | 6 | Standard ADAPT-VQE | GGA-VQE (noisy) | ~50% improvement | [2] |

The measurement costs in early ADAPT-VQE implementations were particularly prohibitive. As demonstrated in Table 1, recent optimizations have achieved dramatic reductions—up to 99.6% for specific molecular systems [16]. These improvements stem from multiple strategies including shot-efficient allocation algorithms, novel operator pools, and modified classical optimization routines.

Strategic Approaches to Measurement Reduction

Algorithmic Optimizations

Several algorithmic innovations have demonstrated significant reductions in measurement requirements:

Pauli Measurement Reuse and Variance-Based Allocation: This approach recycles Pauli measurement outcomes obtained during VQE parameter optimization for subsequent gradient evaluations in later iterations. When combined with variance-based shot allocation that distributes measurements optimally among Hamiltonian terms based on their statistical properties, this strategy reduces shot requirements by 32.29% on average compared to naive measurement approaches [3].

Greedy Gradient-Free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE): This modification replaces the standard two-step ADAPT-VQE procedure with a single-step approach that selects operators and determines their optimal parameters simultaneously [2] [17]. By leveraging the known trigonometric structure of single-parameter energy landscapes, GGA-VQE finds optimal parameters with only 2-5 circuit evaluations per operator, dramatically reducing measurement overhead and demonstrating improved noise resilience [2].

Overlap-ADAPT-VQE: This variant replaces energy-based convergence criteria with overlap maximization relative to a target wavefunction [18]. By avoiding local minima in the energy landscape, it produces more compact ansätze with fewer operators and consequently reduced measurement requirements throughout the optimization process.

Hardware-Efficient Formulations

Alternative operator pool designs significantly impact both circuit depth and measurement requirements:

Qubit-Excitation-Based Pools: Unlike traditional fermionic excitation operators, qubit excitation operators obey qubit commutation relations rather than fermionic anti-commutation rules [19]. This allows for more circuit-efficient implementations while maintaining accuracy, asymptotically reducing gate requirements and associated measurement overhead.

Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) Pool: This novel pool design incorporates coupled cluster and exchange operators specifically tailored for hardware efficiency [16]. When combined with other improvements, CEO-ADAPT-VQE reduces CNOT counts by up to 88% and measurement costs by up to 99.6% compared to early ADAPT-VQE implementations [16].

The relationships between these different optimization strategies and their specific approaches to reducing measurement overhead are illustrated below:

Diagram 1: Measurement overhead reduction strategies in ADAPT-VQE and their functional relationships.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Shot-Efficient ADAPT-VQE with Pauli Reuse

The protocol for shot-efficient ADAPT-VQE integrates two complementary techniques for measurement reduction [3]:

Pauli Measurement Reuse: During the VQE parameter optimization step, measurement outcomes for Pauli operators are stored and reused in the subsequent operator selection step of the next ADAPT-VQE iteration. This approach capitalizes on the fact that the same Pauli strings appear in both the Hamiltonian and the commutators used for gradient calculations.

Variance-Based Shot Allocation: Instead of distributing measurement shots uniformly across all Hamiltonian terms, this method allocates shots proportionally to the variance of each term. Terms with higher variance receive more shots, optimizing the trade-off between measurement cost and precision. The theoretical framework for this approach follows the optimal shot allocation formula derived in prior work [3].

Implementation of this protocol has demonstrated significant reductions in shot requirements—achieving chemical accuracy with only 32.29% of the shots needed by naive measurement approaches for molecular systems ranging from H₂ (4 qubits) to BeH₂ (14 qubits) [3].

Greedy Gradient-Free ADAPT-VQE (GGA-VQE)

GGA-VQE fundamentally restructures the standard ADAPT-VQE workflow to eliminate costly gradient measurements and high-dimensional optimization [2] [17]. The experimental protocol proceeds as follows:

Initialization: Begin with a simple reference state (typically Hartree-Fock) and an empty ansatz circuit.

Operator Screening: For each candidate operator in the pool:

- Evaluate the energy at 2-5 different parameter values (typically θ = 0, ±α, ±2α)

- Fit the energy as a function of the parameter: E(θ) = A cos(θ + φ) + C

- Analytically determine the optimal parameter value θ* that minimizes E(θ)

Greedy Selection: Identify the operator that yields the lowest energy at its optimal parameter θ*.

Ansatz Update: Append the selected operator to the circuit with parameter fixed at θ*.

Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 until convergence criteria are met.

This protocol was successfully implemented on a 25-qubit trapped-ion quantum processor (IonQ Aria) using Amazon Braket, achieving over 98% fidelity in ground state preparation for a 25-spin Ising model—marking the first fully converged adaptive VQE implementation on quantum hardware of this scale [2] [17].

The complete experimental workflow for measurement-efficient ADAPT-VQE implementations, integrating both algorithmic and hardware-specific optimizations, is shown below:

Diagram 2: Complete experimental workflow for measurement-efficient ADAPT-VQE implementations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementation of measurement-efficient ADAPT-VQE requires both theoretical components and computational tools. The following table details these essential "research reagents" and their functions:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Measurement-Efficient ADAPT-VQE

| Research Reagent | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pools | Provides generators for ansatz construction | Fermionic (UCCSD), Qubit excitation (QEB), Coupled Exchange (CEO) [16] [19] |

| Shot Allocation Algorithms | Optimizes distribution of quantum measurements | Variance-based allocation, weighted by term importance [3] |

| Measurement Reuse Protocols | Recycles quantum measurements across algorithm steps | Pauli string outcome reuse between VQE and gradient steps [3] |

| Classical Optimizers | Adjusts circuit parameters to minimize energy | L-BFGS-B, COBYLA, gradient-free optimizers [20] [7] |

| Qubit Tapering | Reduces problem size using symmetries | Identifies and removes qubits via Zâ‚‚ symmetries [7] |

| Active Space Approximations | Reduces Hamiltonian complexity | Selects correlated orbital subspaces, freezes core orbitals [7] |

| Leucomycin A7 | Leucomycin A7, CAS:18361-47-2, MF:C38H63NO14, MW:757.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Justicidin B | Justicidin B, CAS:17951-19-8, MF:C21H16O6, MW:364.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The measurement overhead problem represents a fundamental challenge in deploying ADAPT-VQE algorithms on current quantum hardware. As this analysis demonstrates, significant progress has been made in developing strategies to mitigate this overhead through algorithmic innovations, hardware-efficient formulations, and optimized implementation protocols. The most successful approaches combine multiple techniques—measurement reuse, variance-based shot allocation, and novel operator pools—to achieve dramatic reductions in quantum resource requirements [3] [16].

Despite these advances, current quantum hardware still faces limitations in achieving chemically accurate results for complex molecular systems. Hardware noise, gate errors, and residual measurement overhead continue to constrain practical applications [7] [2]. However, the recent successful implementation of greedy adaptive algorithms on 25-qubit hardware demonstrates a promising path forward [2] [17]. As quantum hardware continues to improve and measurement-efficient algorithms mature, the prospect of achieving practical quantum advantage for molecular simulations grows increasingly tangible.

For researchers in computational chemistry and drug development, these developments signal a crucial transition from purely theoretical studies toward practical quantum-enhanced simulations. The resource optimization strategies outlined in this work provide an essential toolkit for designing experiments that maximize information gain while respecting the severe constraints of NISQ-era quantum devices. Through continued refinement of these approaches, quantum computers may soon become indispensable tools for understanding complex molecular systems and accelerating drug discovery processes.

Accurately estimating molecular energy stands as the foundational challenge in computational drug discovery. The behavior of molecules, from folding proteins to drug-target binding, is governed by quantum mechanics, specifically by the Schrödinger equation [21] [22]. Solving this equation for molecular systems allows researchers to determine stable configurations, reaction pathways, and binding affinities—the crucial predictors of a potential drug's efficacy [21]. However, the computational complexity of exactly solving the Schrödinger equation for anything but the smallest molecules scales exponentially with system size, creating an insurmountable barrier for classical computers exploring vast chemical spaces estimated at 10^60 compounds [21] [23].

The Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era presents both new opportunities and significant constraints for tackling this problem. While quantum computers naturally encode quantum information, current hardware limitations—including noise, decoherence, and limited qubit counts—require innovative algorithmic approaches [2]. The Adaptive Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) has emerged as a promising hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed to navigate these constraints by systematically constructing problem-tailored quantum circuits [2] [3]. This technical guide examines molecular energy estimation within the context of ADAPT-VQE research, providing detailed methodologies and frameworks for researchers pursuing quantum-enabled drug discovery.

Molecular Energy Fundamentals in Drug Discovery

The Quantum Mechanical Basis

At the heart of molecular energy estimation lies the time-independent Schrödinger equation:

$$Ĥ|\Psi⟩ = E|\Psi⟩$$

Where $Ĥ$ represents the molecular Hamiltonian, $|\Psi⟩$ is the wavefunction describing the quantum state of the system, and $E$ is the corresponding energy eigenvalue [21]. For drug discovery applications, the ground state energy ($E_0$) is particularly crucial as it determines molecular stability, reactivity, and interaction capabilities [21]. The variational principle provides the theoretical foundation for most computational approaches:

$$E0 = \min{|\Psi⟩}⟨\Psi|Ĥ|\Psi⟩$$

This principle states that the expectation value of the energy for any trial wavefunction will always be greater than or equal to the true ground state energy [21].

Key Energy Metrics in Pharmaceutical Research

Table 1: Critical Energy Metrics in Drug Discovery

| Energy Metric | Computational Description | Pharmaceutical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Free Energy | $\Delta G = -k_B T \ln K$ | Determines drug-target binding affinity and potency [22] |

| Activation Energy | Energy barrier along reaction coordinate | Predicts metabolic stability and reaction rates [21] |

| Conformational Energy | Energy differences between molecular configurations | Influences protein folding and drug specificity [22] |

| Solvation Energy | Energy change upon transferring to solvent | Affects bioavailability and membrane permeability [21] |

Limitations of Classical Computational Methods

Classical computational methods face fundamental limitations in drug discovery applications. Density Functional Theory (DFT) often struggles with strongly correlated electron systems commonly found in transition metal complexes and excited states crucial for photochemical properties [22]. Empirical force fields, while computationally efficient, lack quantum mechanical accuracy for modeling bond formation and breaking or charge transfer processes [21] [22]. These limitations become particularly problematic when studying enzyme-drug interactions, where quantum effects significantly influence binding mechanisms and reaction pathways.

ADAPT-VQE for NISQ-Era Molecular Energy Estimation

Core Algorithmic Framework

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a significant advancement over fixed-ansatz VQE approaches [2] [3]. Unlike chemistry-inspired ansatze such as Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) or hardware-efficient approaches, ADAPT-VQE iteratively constructs a system-tailored quantum circuit, balancing circuit depth with accuracy—a critical consideration for NISQ devices [3].

The algorithm proceeds through two fundamental steps iteratively:

Step 1: Operator Selection At iteration $m$, given a parameterized ansatz wavefunction $|\Psi^{(m-1)}⟩$, the algorithm selects a new unitary operator $\mathscr{U}^$ from a predefined pool $\mathbb{U}$ based on the gradient criterion: $$\mathscr{U}^ = \underset{\mathscr{U} \in \mathbb{U}}{\text{argmax}} \left| \frac{d}{d\theta} ⟨\Psi^{(m-1)}|\mathscr{U}(\theta)^\dagger Ĥ \mathscr{U}(\theta)|\Psi^{(m-1)}⟩ \Big|_{\theta=0} \right|$$ This identifies the operator that induces the greatest instantaneous decrease in energy [2].

Step 2: Global Optimization After appending $\mathscr{U}^*(\thetam)$, the algorithm performs a multi-parameter optimization: $$(\theta1^{(m)}, \ldots, \thetam^{(m)}) = \underset{\theta1, \ldots, \thetam}{\operatorname{argmin}} ⟨\Psi^{(m)}(\thetam, \ldots, \theta1)|Ĥ|\Psi^{(m)}(\thetam, \ldots, \theta_1)⟩$$ This optimizes all parameters simultaneously to find the lowest energy configuration [2].

ADAPT-VQE Workflow and Optimization

The following diagram illustrates the complete ADAPT-VQE workflow, including key optimization steps for NISQ devices:

NISQ-Specific Optimizations

Shot-Efficient Measurement Strategies A major bottleneck in ADAPT-VQE implementation is the exponential number of measurements (shots) required for operator selection and parameter optimization [3]. Two key strategies address this:

Pauli Measurement Reuse: Reusing Pauli measurement outcomes from VQE parameter optimization in subsequent operator selection steps, particularly for commuting Pauli strings shared between Hamiltonian and gradient observables [3].

Variance-Based Shot Allocation: Dynamically allocating measurement shots based on variance estimates, focusing resources on high-variance terms. This approach has demonstrated shot reductions of 43.21% for Hâ‚‚ and 51.23% for LiH compared to uniform allocation [3].

Measurement Grouping and Commutativity Grouping Hamiltonian terms and gradient observables by qubit-wise commutativity (QWC) or general commutativity reduces the number of distinct measurement circuits required. When combined with measurement reuse, this strategy has achieved average shot usage reduction to 32.29% of naive measurement schemes [3].

Experimental Protocols for Molecular Energy Estimation

Molecular System Preparation Protocol

Step 1: Molecular Geometry Specification

- Input Cartesian coordinates or internal coordinates for the target molecule

- For drug targets, include protein binding pocket residues if studying intermolecular interactions

- Specify charge and spin multiplicity (e.g., singlet, doublet) relevant to drug-like molecules

Step 2: Active Space Selection

- Select molecular orbitals constituting the active space for correlated calculations

- For transition metal complexes in drug targets, include metal d-orbitals and ligand donor orbitals

- Balance computational feasibility with chemical accuracy (typical ranges: 4-14 orbitals)

Step 3: Qubit Hamiltonian Generation

- Apply Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation to fermionic Hamiltonian

- For NISQ devices, consider qubit tapering to reduce qubit count by exploiting symmetries

- The final Hamiltonian takes the form: $HÌ‚ = \sumi ci Pi$ where $Pi$ are Pauli strings

ADAPT-VQE Implementation Protocol

Step 1: Algorithm Initialization

- Prepare reference state (typically Hartree-Fock) using single-qubit gates

- Define operator pool: commonly fermionic excitation operators (singles, doubles)

- Set convergence threshold: chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa) is typical for drug discovery

Step 2: Iterative Circuit Construction For each iteration until convergence:

- Gradient Evaluation: Compute gradients for all pool operators using quantum device

- Operator Selection: Identify operator with largest gradient magnitude

- Circuit Appending: Add selected operator with initial parameter θ=0

- Parameter Optimization: Optimize all circuit parameters using classical minimizer

- Convergence Check: Check if norm of gradient vector < threshold

Step 3: Energy and Property Extraction

- Measure final energy expectation value with error mitigation

- Extract additional properties (dipole moments, orbital energies) if needed for drug design

Measurement Optimization Protocol

Variance-Based Shot Allocation

- For each Pauli term $Pi$, estimate variance $σi^2$ from initial measurements

- Allocate total shot budget $S{\text{total}}$ proportional to $|ci|σ_i$

- For $M$ total terms: $Si = S{\text{total}} \times \frac{|ci|σi}{\sumj |cj|σ_j}$

- Iteratively update variance estimates during optimization

Pauli Measurement Reuse

- Identify commuting sets between Hamiltonian and gradient observables

- Cache measurement outcomes from VQE optimization steps

- Reuse compatible measurements for gradient calculations

- Update cache with new measurements as circuit grows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for ADAPT-VQE Molecular Energy Estimation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Molecular Energy Estimation |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Simulation Platforms | Qiskit, Cirq, PennyLane | Provide abstractions for quantum circuit construction, execution, and result analysis [2] [3] |

| Classical Electronic Structure | PySCF, OpenMolcas, GAMESS | Generate molecular Hamiltonians, reference states, and active space orbitals [3] |

| Hybrid Algorithm Frameworks | Tequila, Orquestra | Manage quantum-classical workflow, parameter optimization, and convergence tracking [2] |

| Measurement Optimization | Qiskit Nature, PennyLane Grouping | Implement commutativity grouping, shot allocation, and measurement reuse protocols [3] |

| Error Mitigation Tools | Mitiq, Zero-Noise Extrapolation | Reduce effects of hardware noise on energy measurements through post-processing [2] |

| Chemical Data Resources | PubChem, ChEMBL, ZINC | Provide molecular structures, properties, and bioactivity data for validation [23] |

| DL-Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate | DL-Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, CAS:142-10-9, MF:C3H7O6P, MW:170.06 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Methyl Tanshinonate | Methyl Tanshinonate | Methyl Tanshinonate is a tanshinone derivative for research use, shown to inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome activation. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Performance Analysis and Benchmarking

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 3: ADAPT-VQE Performance Across Molecular Systems

| Molecule | Qubit Count | Circuit Depth | Energy Error (mHa) | Shot Reduction | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | 4 | 12 | <0.1 | 43.21% [3] | Statistical noise in measurements [2] |

| LiH | 10 | 48 | 1.2 | 51.23% [3] | High-dimensional parameter optimization [2] |

| Hâ‚‚O | 14 | 76 | 2.8 | N/A | Noise-induced optimization stagnation [2] |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | 82 | 3.1 | ~32% [3] | Measurement overhead for operator selection [3] |

Comparative Analysis with Classical Methods

Accuracy and Resource Requirements ADAPT-VQE demonstrates potential for achieving chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa) with significantly reduced quantum resources compared to fixed-ansatz approaches [3]. For the water molecule, ADAPT-VQE achieves comparable accuracy to classical full configuration interaction (FCI) while requiring substantially fewer quantum gates than UCCSD [2]. However, current NISQ implementations still face challenges with statistical noise causing optimization stagnation above chemical accuracy thresholds [2].

Measurement Overhead Analysis The shot-efficient ADAPT-VQE framework demonstrates substantial improvements in measurement efficiency:

- Measurement reuse alone reduces shots to ~38% of naive approach

- Combined with commutativity grouping, this improves to ~32% of naive approach [3]

- Variance-based shot allocation provides additional 5-51% reduction depending on molecular system [3]

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The integration of Explainable AI (XAI) techniques with quantum algorithms represents a promising frontier for enhancing interpretability in molecular energy estimation [24]. Techniques such as QSHAP (Quantum SHapley Additive exPlanations) and QLRP (Quantum Layer-Wise Relevance Propagation) are being developed to provide insights into feature importance and decision processes within quantum machine learning models for drug discovery [24].

As quantum hardware continues to evolve with improving gate fidelities and increased qubit coherence times, the practical scope for molecular energy estimation will expand to larger, pharmaceutically relevant systems [21]. Research directions include developing more compact operator pools, improving measurement strategies, and creating robust error mitigation techniques specifically tailored for molecular energy problems [3]. The ongoing benchmarking of clinical quantum advantage and development of scalable, transparent quantum-classical frameworks will be crucial for establishing molecular energy estimation as a reliable tool in the drug discovery pipeline [24].

Evolving the Algorithm: Recent Methodological Breakthroughs in ADAPT-VQE

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a significant advancement in quantum computational chemistry, specifically designed for the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era. Unlike fixed-structure ansätze such as Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD), ADAPT-VQE dynamically constructs a problem-specific ansatz by iteratively appending parameterized unitary operators from a predefined "operator pool" to an initial reference state. This iterative process, guided by gradient-based selection criteria, systematically grows the ansatz to recover correlation energy, typically yielding more compact and accurate circuits than static approaches. The algorithm's performance and efficiency, however, are profoundly influenced by the composition and properties of this operator pool, making its design a central research focus.

Early ADAPT-VQE implementations predominantly utilized fermionic operator pools, such as the Generalized Single and Double (GSD) excitations pool. While these pools can, in principle, converge to exact solutions, they often generate quantum circuits with considerable depth and high measurement overhead, presenting significant implementation challenges on current NISQ hardware. Recent research has therefore shifted toward developing more hardware-efficient and chemically-aware operator pools. Among the most promising innovations is the Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool, a novel construct designed to dramatically reduce quantum resource requirements while maintaining or even enhancing algorithmic accuracy. This technical guide explores the architecture, advantages, and implementation of CEO pools, positioning them as a pivotal development for practical quantum chemistry simulations on near-term quantum devices [16] [25].

The Core Concept: What Are Coupled Exchange Operators?

The Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool is a novel type of operator pool designed specifically to enhance the hardware efficiency and convergence properties of the ADAPT-VQE algorithm. Its development stems from a critical analysis of the structure of qubit excitations and their impact on quantum circuit complexity [16].

Theoretical Foundation and Design Principles

Traditional fermionic pools, like GSD, are composed of operators that correspond to single and double excitations in the molecular orbital basis. When mapped to qubit operators (e.g., via Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformations), these fermionic operators often translate into multi-qubit gates with high Pauli weights, resulting in deep circuits with high CNOT counts.

The CEO pool is built on a fundamentally different principle. It explicitly incorporates coupled electron pairs directly into its design. The operators within the CEO pool are constructed to efficiently capture the dominant correlation effects in molecular systems, particularly those involving paired electrons, which are ubiquitous in chemical bonds. This targeted design avoids the inclusion of less relevant operators that contribute minimally to energy convergence but significantly increase circuit depth and measurement costs. The primary innovation lies in formulating exchange-type interactions that natively respect the coupling between electron pairs, leading to a more chemically-intuitive and hardware-efficient operator set [16].

Table 1: Core Components of the CEO Pool

| Component | Description | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Coupled Pair Interactions | Operators designed to act on coupled electron pairs. | Efficiently capture dominant correlation effects in molecular bonds. |

| Exchange-Type Terms | Operators facilitating the exchange of states between coupled pairs. | Model electron exchange correlations with low quantum resource cost. |

| Hardware-Efficient Mapping | A formulation that leads to lower Pauli weights upon qubit transformation. | Minimize CNOT gate count and circuit depth in the resulting quantum circuit. |

Advantages and Performance Metrics

The implementation of the CEO pool within ADAPT-VQE, an algorithm referred to as CEO-ADAPT-VQE, demonstrates substantial improvements over previous state-of-the-art methods across several key performance indicators. The advantages are most pronounced in metrics critical for NISQ-era devices: circuit depth, gate count, and measurement overhead [16].

Quantitative Performance Gains

Numerical simulations on small molecules such as LiH, H6, and BeH2 (represented by 12 to 14 qubits) reveal the dramatic resource reductions enabled by the CEO pool. When compared to the original fermionic (GSD) ADAPT-VQE, the CEO-based approach achieves superior performance with a fraction of the resources.

Table 2: Quantitative Resource Reduction of CEO-ADAPT-VQE vs. Original ADAPT-VQE

| Molecule | CNOT Count Reduction | CNOT Depth Reduction | Measurement Cost Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| LiH (12 qubits) | 88% | 96% | 99.6% |

| H6 (12 qubits) | 85% | 95% | 99.0% |

| BeH2 (14 qubits) | 73% | 92% | 98.5% |

| Average Reduction | ~82% | ~94% | ~99% |

These figures represent the resource requirements at the first iteration where chemical accuracy (1 milliHartree error) is achieved. The reduction in measurement costs is particularly critical, as the large number of measurements required for operator selection and energy evaluation constitutes a major bottleneck for VQE algorithms on real hardware [16] [2].

Comparative Analysis with Other Ansätze

The CEO-ADAPT-VQE algorithm not only outperforms its predecessor but also holds a significant advantage over popular fixed-structure ansätze.

- vs. UCCSD: CEO-ADAPT-VQE consistently outperforms UCCSD in all relevant metrics, including parameter count, CNOT gate count, and achieved accuracy, especially for systems exhibiting strong correlation.

- vs. Other Static Ansätze: The measurement cost of CEO-ADAPT-VQE is reported to be five orders of magnitude lower than that of other static ansätze with comparable CNOT counts. This makes it a far more feasible algorithm for execution on current quantum devices where measurement is a time-consuming and noisy process [16].

Furthermore, the adaptive nature of the algorithm helps mitigate issues like "barren plateaus" (exponential vanishing of gradients in large parameter spaces), which often plague fixed, hardware-efficient ansätze. The problem-specific, iterative construction of the ansatz maintains a more tractable optimization landscape [25].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementing and benchmarking the CEO-ADAPT-VQE algorithm involves a well-defined hybrid quantum-classical workflow. The following protocol details the key steps for a typical molecular simulation, from initialization to convergence.

CEO-ADAPT-VQE Workflow Protocol

Step 1: Initialization

- Classical Pre-processing: Perform a classical Hartree-Fock (HF) calculation for the target molecule to obtain a set of molecular orbitals and the corresponding second-quantized electronic Hamiltonian.

- Qubit Hamiltonian Mapping: Transform the fermionic Hamiltonian into a qubit-represented Hamiltonian using a transformation such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev.

- Reference State Preparation: Prepare the HF state, ( \vert \psi_{\text{ref}} \rangle ), on the quantum computer. This is typically a simple computational basis state (e.g., ( \vert 0\rangle^{\otimes n} )).

Step 2: Adaptive Ansatz Construction Loop For iteration ( m = 1 ) to ( M_{\text{max}} ):

- Gradient Evaluation: For every operator ( \mathscr{U}k ) in the pre-defined CEO pool, compute the energy gradient: [ gk = \frac{d}{d\theta} \langle \psi^{(m-1)} \vert \mathscr{U}k(\theta)^\dagger \hat{H} \mathscr{U}k(\theta) \vert \psi^{(m-1)} \rangle \Big\vert{\theta=0} ] This is typically done using quantum hardware to evaluate the expectation values of commutators ( [\hat{H}, Ak] ), where ( Ak ) is the generator of ( \mathscr{U}k ).

- Operator Selection: Identify the operator ( \mathscr{U}^* ) with the largest absolute gradient magnitude: [ \mathscr{U}^* = \underset{\mathscr{U}k \in \text{CEO Pool}}{\text{argmax}} \vert gk \vert ]

- Ansatz Appending: Append the selected operator to the current ansatz: [ \vert \psi^{(m)}(\vec{\theta}) \rangle = \mathscr{U}^*(\thetam) \vert \psi^{(m-1)}(\vec{\theta}{old}) \rangle ] The ansatz now has the form ( \prod{k=1}^{m} \mathscr{U}k(\thetak) \vert \psi{\text{ref}} \rangle ), where the product is ordered from the last operator to the first.

- Variational Optimization: Execute a classical optimization routine to minimize the energy expectation value with respect to all parameters ( \vec{\theta} = (\theta1, ..., \thetam) ) in the new ansatz: [ E^{(m)} = \underset{\vec{\theta}}{\text{min}} \langle \psi^{(m)}(\vec{\theta}) \vert \hat{H} \vert \psi^{(m)}(\vec{\theta}) \rangle ] The quantum computer is used to prepare ( \vert \psi^{(m)}(\vec{\theta}) \rangle ) and measure the expectation value of the Hamiltonian for different parameter sets.

- Convergence Check: If the energy change ( \vert E^{(m)} - E^{(m-1)} \vert ) is below a predefined threshold (e.g., 1 milliHartree for chemical accuracy), exit the loop. Otherwise, proceed to the next iteration.

The following diagram visualizes this iterative workflow.

Key Experimental Considerations

- Measurement Techniques: To reduce the quantum resource overhead during the gradient evaluation step (Step 2.1), advanced measurement techniques like commutation-based grouping or classical shadow tomography can be employed to minimize the number of distinct quantum measurements required.

- Classical Optimizer: The choice of classical optimizer (e.g., COBYLA, SPSA) is critical. For NISQ devices, optimizers that are robust to noise and require fewer function evaluations are preferred.

- Operator Pool Definition: The specific mathematical definition of the CEO pool is foundational. It is constructed from a set of anti-Hermitian generators ( {\hat{A}k} ) that define the parameterized unitaries ( \mathscr{U}k(\theta) = e^{\theta \hat{A}k} ). The novelty of the CEO pool lies in the specific coupled structure of these ( \hat{A}k ) generators [16] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing CEO-ADAPT-VQE requires a combination of quantum software, hardware, and classical computational resources. The following table outlines the essential "research reagents" for this field.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for CEO-ADAPT-VQE Research

| Tool Category | Example Solutions | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Algorithm Frameworks | Qiskit (IBM), CUDA-Q (NVIDIA), Amazon Braket | Provide libraries for constructing CEO pools, defining ansätze, and managing the hybrid quantum-classical loop. |

| Classical Computational Chemistry Software | PySCF, Q-Chem, GAMESS | Perform initial Hartree-Fock calculation and generate the molecular electronic Hamiltonian. |

| Quantum Hardware/Simulators | IBM Quantum Systems, IonQ Forte, QuEra Neutral Atoms, NVIDIA GPU Simulators | Execute the quantum circuits for state preparation and expectation value measurement. |

| Operator Pool Definitions | Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) Pool, Qubit-ADAPT Pool, Fermionic (GSD) Pool | The core "reagent" that defines the search space for building the adaptive ansatz. |

| Measurement Reduction Tools | Classical Shadows, Commutation Grouping Algorithms | Reduce the number of quantum measurements needed for gradient estimation and energy evaluation. |

| Tropodifene | Tropodifene, CAS:15790-02-0, MF:C25H29NO4, MW:407.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Benzenamine, 3-methoxy-4-(1-pyrrolidinyl)- | Benzenamine, 3-methoxy-4-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-, CAS:16089-42-2, MF:C11H16N2O, MW:192.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Leading quantum computing companies are actively developing the ecosystem supporting this research. For instance, Amazon Braket provides a unified platform to access various quantum devices (from partners like IonQ and QuEra) and simulators, which is ideal for testing and benchmarking CEO-ADAPT-VQE across different hardware architectures [26]. NVIDIA's CUDA-Q platform has been used to run record-scale quantum algorithm simulations (e.g., 39-qubit circuits), demonstrating the scalability of the classical components needed for this research [27].

The development of the Coupled Exchange Operator pool marks a significant stride toward realizing the potential of quantum computational chemistry in the NISQ era. By moving beyond generic fermionic operator pools to a chemically-informed, hardware-efficient design, CEO-ADAPT-VQE successfully addresses critical bottlenecks of circuit depth and measurement cost. The demonstrated reductions in CNOT counts and measurement overhead by orders of magnitude bring practical simulations of small molecules within closer reach of existing quantum hardware.

Future research will likely focus on further refining operator pools for specific molecular systems and chemical problems, such as transition metal complexes or catalytic reaction pathways. The integration of CEO-ADAPT-VQE with advanced error mitigation techniques and more powerful quantum hardware, as highlighted by the rapid progress in companies like IBM, Google, and IonQ, will be crucial for scaling these methods to larger, industrially relevant molecules [28]. As the field progresses, innovative operator pools like the CEO are poised to form the computational backbone for the first practical quantum chemistry applications, ultimately accelerating discoveries in drug development and materials science.

The Adaptive Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a promising algorithmic framework for quantum chemistry simulations on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. By iteratively constructing problem-tailored ansätze, it addresses critical limitations of fixed-ansatz approaches, including circuit depth and trainability issues such as barren plateaus [3]. However, a significant bottleneck hindering its practical implementation is the enormous quantum measurement (shot) overhead required for both parameter optimization and operator selection [13] [3].

This technical guide details two integrated strategies—Pauli measurement reuse and variance-based shot allocation—developed to drastically reduce the shot requirements of ADAPT-VQE. These methodologies address the core challenge of measurement inefficiency, enabling more feasible execution of adaptive quantum algorithms on contemporary hardware while maintaining chemical accuracy [13].

Core Methodologies

Pauli Measurement Reuse Strategy

The Pauli measurement reuse strategy is designed to eliminate redundant evaluations of identical Pauli operators across different stages of the ADAPT-VQE algorithm [13] [3].

Theoretical Foundation: The ADAPT-VQE algorithm operates through an iterative cycle. In each iteration, the classical optimizer requires the energy expectation value, which involves measuring the Hamiltonian, expressed as a sum of Pauli strings. Concurrently, the operator selection step for the next iteration requires calculating gradients of the form ( \frac{d}{d\theta} \langle \psi | U^\dagger(\theta) H U(\theta) | \psi \rangle |{\theta=0} ), where (U(\theta)) is a pool operator. These gradients often involve measuring commutators ([H, Ak]), which can be expanded into a linear combination of Pauli strings [3]. Crucially, there is significant overlap between the Pauli strings in the Hamiltonian (H) and those resulting from the commutator expansion.

Protocol Implementation:

- Initial Setup and Analysis: Before the first ADAPT-VQE iteration, perform a classical analysis of the molecular Hamiltonian (H) and all operators (Ak) in the predefined pool. Compute the commutators ([H, Ak]) and expand both (H) and each commutator into their constituent Pauli strings.

- Measurement and Storage: During the VQE parameter optimization step in iteration (m), measure all Pauli strings (Pj) constituting the Hamiltonian (H = \sumj cj Pj). Store these measurement outcomes (estimated expectation values (\langle P_j \rangle)) in a dedicated classical registry.

- Reuse in Operator Selection: When proceeding to the operator selection step for iteration (m+1), instead of performing new quantum measurements for all Pauli strings in the gradient observables, the algorithm first checks the registry. For any Pauli string (Pj) that has already been measured in step 2, the stored value (\langle Pj \rangle) is reused.

- Iterative Update: The registry is updated at the end of each VQE optimization step, ensuring that the most recent state characterization is used for subsequent operator selection.

This protocol decouples the shot-intensive quantum measurement from the classical post-processing for operator selection, leading to significant resource savings without introducing substantial classical overhead [3].

Variance-Based Shot Allocation

Variance-based shot allocation optimizes the distribution of a finite shot budget across different measurable observables to minimize the overall statistical error in the estimated energy or gradient [13] [3].

Theoretical Foundation: The statistical error (variance) in estimating the expectation value of a linear combination of observables (O = \sumi ci Oi) depends on the variances of the individual terms and the number of shots allocated to each. The goal is to distribute a total shot budget (S{\text{total}}) among (T) terms to minimize the total variance (\sigma^2{\text{total}} = \sum{i=1}^T \frac{ci^2 \sigmai^2}{si}), where (\sigmai^2) is the variance of term (i) and (si) is the number of shots allocated to it, with the constraint (\sum{i=1}^T si = S{\text{total}}) [3].

Protocol Implementation: Two primary strategies are employed:

- Variance-Matched Shot Allocation (VMSA): This method allocates shots proportional to the magnitude of the coefficient ( |ci| ) and the estimated standard deviation ( \sigmai ) of each term: ( si \propto |ci| \sigma_i ). This heuristic aims to equalize the contribution to the error from each term.

- Variance-Proportional Shot Reduction (VPSR): This method, adapted from theoretical optima, allocates shots proportional to the squared coefficient and variance of each term: ( si \propto ci^2 \sigma_i^2 ). This provides a more aggressive reduction in shots for terms with lower uncertainty and smaller coefficients, leading to greater overall shot efficiency [3].

Application in ADAPT-VQE: This strategy is applied to two critical measurement steps:

- Hamiltonian Measurement: Shots are allocated across the grouped Pauli terms of the Hamiltonian (H) during VQE optimization.

- Gradient Measurement: Shots are allocated across the grouped Pauli terms arising from the commutator expansions ([H, A_k]) used for operator selection.

The integration of this strategy requires an initial pre-fetch of measurements to estimate the variances ( \sigma_i^2 ) for the current quantum state, followed by the optimized shot allocation for the final, high-precision estimation.

Integrated Workflow

The two strategies are designed to work synergistically within a single ADAPT-VQE workflow. The following diagram illustrates the integrated process and the logical relationship between its components.

Experimental Protocols & Performance Data

Protocol for Validating Pauli Measurement Reuse

The protocol for validating the Pauli measurement reuse strategy involves numerical simulations on molecular systems to quantify shot reduction [3].

1. System Preparation:

- Molecular Systems: Select a set of benchmark molecules, such as Hâ‚‚, LiH, BeHâ‚‚, and Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„ (with an active space of 8 electrons in 8 orbitals, requiring 16 qubits).

- Qubit Encoding: Map the electronic Hamiltonian to a qubit Hamiltonian using the Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation.

- Operator Pool: Define an operator pool, typically consisting of fermionic excitation operators (e.g., single and double excitations).

2. Baseline Measurement:

- Execute the standard ADAPT-VQE algorithm without any shot-efficient enhancements.

- For each iteration, record the total number of shots consumed for both VQE optimization and operator selection. This establishes the baseline shot count.

3. Enhanced Protocol Execution:

- Execute the modified ADAPT-VQE algorithm incorporating the Pauli measurement reuse protocol.

- Implement qubit-wise commutativity (QWC) grouping for both the Hamiltonian and gradient observables.

- In the operator selection step, systematically replace measurements of Pauli terms already present in the registry with their stored values.

4. Data Collection and Analysis:

- Track the cumulative number of shots used across all ADAPT-VQE iterations until convergence to chemical accuracy (1 milliHartree).

- Compare the total shots against the baseline to calculate the percentage reduction.

- Verify that the final energy and ansatz structure are not compromised by the reuse strategy.

Key Results: The application of this protocol demonstrated a significant reduction in quantum resource requirements. When combined with measurement grouping, the reuse strategy reduced the average shot usage to 32.29% of the naive full-measurement scheme. Using measurement grouping alone resulted in a reduction to 38.59% [3].

Protocol for Validating Variance-Based Shot Allocation

This protocol tests the efficacy of variance-based shot allocation in reducing the number of measurements required for energy estimation within ADAPT-VQE [3].

1. System Preparation:

- Use simpler molecular systems like Hâ‚‚ and LiH with approximated Hamiltonians to facilitate extensive numerical analysis.

- Prepare the initial reference state (e.g., Hartree-Fock) and define the ansatz growth path.

2. Shot Allocation Implementation:

- Variance Estimation: For a given quantum state (|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle), perform an initial set of measurements (a "pre-fetch") to estimate the variance (\sigmai^2) for each grouped Pauli term in the observable (either (H) or ([H, Ak])).

- Shot Budgeting: Allocate a total shot budget (S{\text{total}}) for the observable estimation. Distribute the shots among the terms according to the VMSA ((si \propto |ci| \sigmai)) or VPSR ((si \propto ci^2 \sigma_i^2)) strategies.

- Final Estimation: Perform the final measurements using the allocated shots (s_i) for each term and compute the weighted sum to obtain the expectation value.

3. Performance Evaluation:

- For a fixed total shot budget (S_{\text{total}}), compare the statistical error in the energy estimate obtained from variance-based allocation against that from a uniform shot distribution.

- Alternatively, determine the minimum (S_{\text{total}}) required by each method to achieve a target statistical error (e.g., chemical accuracy).

Key Results: Application of this protocol to Hâ‚‚ and LiH molecules showed substantial improvements in shot efficiency [3]:

- For Hâ‚‚, shot reductions of 6.71% (VMSA) and 43.21% (VPSR) were achieved relative to uniform shot distribution.

- For LiH, shot reductions of 5.77% (VMSA) and 51.23% (VPSR) were achieved.

Table 1: Quantitative performance of shot-efficient strategies.

| Strategy | Test System | Key Metric | Performance Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pauli Reuse + Grouping | Multiple Molecules (Hâ‚‚ to BeHâ‚‚) | Average Shot Usage | 32.29% of baseline [3] |

| Grouping Only | Multiple Molecules (Hâ‚‚ to BeHâ‚‚) | Average Shot Usage | 38.59% of baseline [3] |

| VPSR | Hâ‚‚ | Shot Reduction vs. Uniform | 43.21% [3] |

| VMSA | Hâ‚‚ | Shot Reduction vs. Uniform | 6.71% [3] |

| VPSR | LiH | Shot Reduction vs. Uniform | 51.23% [3] |

| VMSA | LiH | Shot Reduction vs. Uniform | 5.77% [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Implementing shot-efficient ADAPT-VQE requires a combination of quantum computational and classical electronic structure resources. The following table details the essential components.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational resources.

| Item Name | Type | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Hamiltonian | Input Data | The electronic structure of the target molecule in second quantization, defining the problem for VQE [3]. |

| Fermionic Pool Operators | Input Data | A pre-defined set of excitation operators (e.g., singles and doubles) from which the adaptive ansatz is constructed [3]. |

| Qubit Hamiltonian | Processed Data | The molecular Hamiltonian mapped to a linear combination of Pauli strings using an encoding (e.g., Jordan-Wigner) [3]. |

| Pauli Measurement Registry | Software/Data | A classical data structure that stores the estimated expectation values of measured Pauli strings for reuse across algorithm steps [3]. |

| Commutativity Grouping Algorithm | Software Tool | An algorithm (e.g., Qubit-Wise Commutativity) that groups mutually commuting Pauli terms into measurable sets, reducing circuit executions [3]. |

| Variance Estimation Routine | Software Tool | A classical subroutine that analyzes initial measurement samples to estimate the variance of individual Pauli terms for shot allocation [3]. |

| 1-Propyne, 3-(1-ethoxyethoxy)- | 1-Propyne, 3-(1-ethoxyethoxy)-, CAS:18669-04-0, MF:C7H12O2, MW:128.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sodium Diacetate | Sodium Diacetate, CAS:126-96-5, MF:C4H7NaO4, MW:142.09 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of Pauli measurement reuse and variance-based shot allocation presents a comprehensive strategy for mitigating one of the most pressing bottlenecks in adaptive variational quantum algorithms. By systematically eliminating redundant quantum measurements and optimizing the informational yield from each shot, these methods significantly lower the quantum resource overhead of ADAPT-VQE [13] [3]. The documented protocols and performance data provide a roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to implement these shot-efficient techniques, thereby advancing the feasibility of quantum computational chemistry on NISQ-era devices.

In the pursuit of quantum advantage for molecular simulations on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, researchers face significant constraints in qubit count, connectivity, and coherence times. Variational quantum algorithms, particularly the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), have emerged as promising approaches for electronic structure calculations during this era. However, current quantum hardware limitations prevent meaningful evaluation of complex molecular Hamiltonians with sufficient accuracy for reliable quantum chemical insights [10]. These constraints are particularly pronounced for adaptive VQE protocols like ADAPT-VQE, where circuit depth and measurement requirements grow substantially with system size.

Active space approximation represents a foundational strategy for Hamiltonian simplification, enabling researchers to focus computational resources on the most chemically relevant electrons and orbitals. This approach is especially valuable in the NISQ context, where problem sizes must be reduced to accommodate hardware limitations [8]. By truncating the full configuration interaction (FCI) problem to a manageable active space, the exponential scaling of quantum simulations can be mitigated, making molecular systems tractable for current quantum devices while preserving essential chemical accuracy.

Theoretical Framework of Active Space Approximations

Mathematical Foundation

The electronic structure problem is governed by the molecular Hamiltonian, which in second quantization is expressed as:

$$\hat{H}=\sum {pq}{h}{pq}{\hat{a}}{p}^{\dagger }{\hat{a}}{q}+\frac{1}{2}\sum {pqrs}{g}{pqrs}{\hat{a}}{p}^{\dagger }{\hat{a}}{r}^{\dagger }{\hat{a}}{s}{\hat{a}}{q}+{\hat{V}}_{nn}$$