Dynamical Decoupling Protocols: Boosting Accuracy in Quantum Chemistry Computations

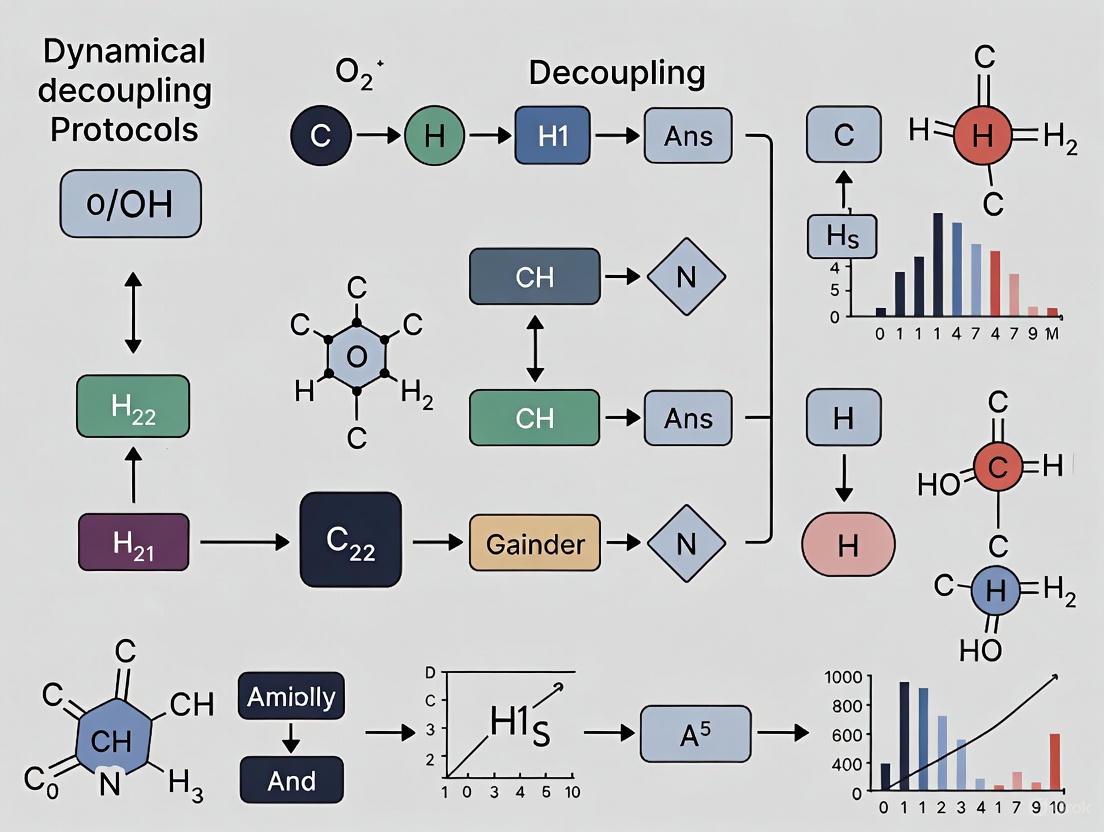

This article explores the critical role of dynamical decoupling (DD) protocols in suppressing decoherence and enhancing the fidelity of quantum chemistry computations on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices.

Dynamical Decoupling Protocols: Boosting Accuracy in Quantum Chemistry Computations

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of dynamical decoupling (DD) protocols in suppressing decoherence and enhancing the fidelity of quantum chemistry computations on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. We cover foundational principles, from the basic Hahn spin echo to advanced sequences like CPMG and UDD, and detail their methodological application in key algorithms such as Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE). The content provides a troubleshooting guide for dominant error sources like memory noise and crosstalk, and presents validation data from recent hardware demonstrations, including the first complete error-corrected quantum chemistry simulation. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource outlines how DD and quantum error correction are paving the way for practical quantum advantage in simulating molecular systems.

Understanding Dynamical Decoupling: The Foundation of Noise Suppression in Quantum Systems

Dynamical decoupling (DD) is an open-loop quantum control technique employed in quantum computing to suppress decoherence by taking advantage of rapid, time-dependent control modulation [1]. In its simplest form, DD is implemented by periodic sequences of instantaneous control pulses, whose net effect is to approximately average the unwanted system-environment coupling to zero [1]. These techniques, derived from nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), have become essential for protecting quantum information in applications ranging from quantum sensing to quantum information processing [2] [1].

For quantum chemistry computations, where simulating molecular systems requires maintaining quantum coherence for computationally useful periods, dynamical decoupling provides a critical error suppression method [3]. By mitigating the interactions between the quantum system and its environment, DD sequences enable more accurate simulations of molecular structures, reaction pathways, and electronic properties that are fundamental to drug development and materials science [4].

The Foundation: Hahn Spin Echo

Basic Principle and Protocol

The foundation of most dynamical decoupling sequences is the Hahn spin echo, first discovered in 1950 by Erwin Hahn [1]. The technique was originally developed in the context of nuclear magnetic resonance but its principle is general. It is designed to reverse the effects of dephasing caused by slow or static inhomogeneities in the environment.

The Hahn echo protocol for a single qubit proceeds as follows [5] [1]:

- A qubit, initially in a superposition state, is allowed to evolve for a time Ï„

- At time τ, a short and strong control pulse is applied, which effectively rotates the qubit state by 180° (a π-pulse) around an axis in the equatorial plane of the Bloch sphere

- The qubit is then allowed to evolve for another period of time Ï„

The crucial effect of the π-pulse is that it inverts the accumulated phase. The qubits that were precessing faster and had accumulated more phase now precess "backwards" relative to the slower ones. After the second evolution period of τ, the slower and faster components realign perfectly, leading to a recovery of the quantum coherence in the form of an "echo" [1].

Experimental Implementation

The experimental implementation of the Hahn echo follows a specific pulse sequence [5]:

- Initialization: Initialize the qubit into a superposition state using an ( X_{\pi/2} ) (X90) pulse

- Free evolution: Allow the system to evolve for time Ï„

- Refocusing pulse: Apply a ( Y_\pi ) (Y180) pulse

- Second free evolution: Allow the system to evolve for another period Ï„

- Readout: Apply a final ( X_{\pi/2} ) pulse to project the state for measurement

The Hahn echo is effective at cancelling noise that is constant or varies very slowly on the timescale of 2Ï„. However, it is ineffective against noise that fluctuates on a faster timescale [1].

Diagram: Hahn Echo Pulse Sequence for a single qubit, showing initialization, free evolution periods, refocusing pulse, and final measurement.

Advanced Dynamical Decoupling Sequences

Common DD Sequences and Their Properties

To combat more general, time-varying noise, the Hahn echo concept extends into sequences of multiple pulses [1]. These sequences create more frequent and robust "refocusing" of the qubit's state, effectively filtering out a wider band of noise frequencies.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Dynamical Decoupling Sequences

| Sequence | Pulse Sequence | Noise Suppression | Robustness to Pulse Errors | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hahn Echo | ( \tau - X_\pi - \tau ) | Static/low-frequency dephasing | Low | Basic refocusing, Tâ‚‚ measurement |

| CPMG | ( \tau/2 - X\pi - \tau - X\pi - \tau/2 ) | Time-varying dephasing | High (compensates over-rotation) | NMR, trapped ions, NV centers [1] |

| XY4 | ( \tau - X\pi - \tau - Y\pi - \tau - X\pi - \tau - Y\pi ) | Generic system-environment interactions | Moderate | Universal decoupling [3] |

| UDD | Non-uniform spacing: ( \delta_j=T\sin^2(\frac{\pi j}{2n+2}) ) | High-frequency noise with sharp cutoff | Varies | Specific noise spectra [1] |

| CDD | Recursive construction | Arbitrarily high-order noise cancellation | Decreases with concatenation level | Quantum memory [1] |

The CPMG Sequence

One of the most widely used and robust periodic sequences is the Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) sequence [1]. It is an improvement on the original Carr-Purcell sequence that makes it resilient to pulse errors. The sequence consists of a train of equally spaced π-pulses:

Free evolution (Ï„/2) - (Ï€-pulse) - Free evolution (Ï„) - (Ï€-pulse) - ... - Free evolution (Ï„) - (Ï€-pulse) - Free evolution (Ï„/2)

The key innovation of Meiboom and Gill was to apply the π-pulses along an axis perpendicular to the initial qubit state in the Bloch sphere's equatorial plane [1]. This change has the critical effect of compensating for small pulse rotation errors. If a pulse slightly over-rotates the qubit, the next pulse in the sequence will have an opposite over-rotation effect, canceling the error to first order.

Advanced DD Protocols

Uhrig Dynamical Decoupling (UDD) uses non-uniformly spaced π-pulses, with the timing of the j-th pulse in a sequence of n pulses applied over a total time T given by ( \delta_j=T\sin^2\left({\frac{\pi j}{2n+2}}\right) ) [1]. This specific timing is mathematically optimized to provide a high-order suppression of general dephasing noise.

Concatenated Dynamical Decoupling (CDD) provides a recursive method for constructing sequences that can theoretically cancel noise to an arbitrarily high order [1]. The design is hierarchical: CDD-1 is simply the Hahn spin echo, CDD-2 replaces each period of free evolution in CDD-1 with the entire CDD-1 sequence itself, and so on.

Theoretical Foundation: Average Hamiltonian Theory

The effectiveness of dynamical decoupling is formally described using Average Hamiltonian Theory (AHT) [1]. The goal of AHT is to describe the net evolution of a system under a rapid, periodic control sequence with a single, time-independent effective Hamiltonian (H_eff).

The analysis begins with the total Hamiltonian of a qubit coupled to an environment: [ H{\text{total}}(t) = H{\text{sys}} + H{\text{ctrl}}(t) + H{\text{err}} ] where ( H{\text{ctrl}}(t) ) represents the DD pulses and ( H{\text{err}} ) is the noise to be suppressed [1].

The analysis proceeds by moving into an interaction picture defined by the control pulses (the "toggling frame"). In this frame, the error Hamiltonian is modulated by the control pulses: [ {\tilde{H}}{\text{err}}(t) = Uc^{\dagger}(t)H{\text{err}}Uc(t) ] where ( U_c(t) ) is the control unitary evolution operator [1].

The total evolution over one DD cycle of period T is expressed using the Magnus expansion: [ U{\text{err}}(T) = {\mathcal{T}}\exp\left(-i\int0^T {\tilde{H}}{\text{err}}(t')dt'\right) = \exp(-iH{\text{eff}}T) ] where ( H{\text{eff}} ) can be written as a series ( H{\text{eff}} = H^{(0)} + H^{(1)} + H^{(2)} + \ldots ) [1].

The first-order term (the average Hamiltonian) is: [ H^{(0)} = \frac{1}{T}\int0^T {\tilde{H}}{\text{err}}(t)dt ]

A successful DD sequence makes these terms vanish. A sequence that makes ( H^{(0)} = 0 ) is considered a first-order decoupling sequence. Higher-order sequences like UDD or CDD are designed to make both ( H^{(0)} ) and ( H^{(1)} ) (and sometimes higher terms) simultaneously zero [1].

Diagram: Theoretical Framework of Dynamical Decoupling showing the transformation from environmental noise to an effective Hamiltonian through the toggling frame and Magnus expansion.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Hahn Echo Experimental Protocol

For superconducting qubits, the Hahn echo protocol can be implemented as follows [5]:

Device Setup Requirements:

- Configured DeviceSetup with Qubit objects

- Signal generation and readout capabilities (e.g., SHFQC+ instrument)

- TunableTransmonQubit parameters:

drive_lo_frequency: Qubit drive frequencyresonance_frequency_ge: Ground-to-excited state transition frequencyreadout_resonator_frequency: Readout resonator frequency

Pulse Parameters:

- ( X_{\pi/2} ) pulse: Gaussian edge pulses with

sigma = 0.25(normalized time units) - ( Y\pi ) pulse: Same duration as ( X{\pi/2} ) pulse but with doubled amplitude

- Free evolution time Ï„: Swept parameter, typically from nanoseconds to microseconds

Sequence Steps:

- Qubit Initialization: Ground state preparation

- First ( X_{\pi/2} ) pulse: Creates superposition state

- First free evolution period (Ï„): System accumulates phase

- ( Y_\pi ) pulse: Refocusing pulse

- Second free evolution period (Ï„): Phase continues evolving

- Second ( X_{\pi/2} ) pulse: Projects state for measurement

- Readout: Measurement of qubit state

Hahn-Ramsey Scheme for Enhanced DC Magnetometry

The Hahn-Ramsey scheme extends the basic Hahn echo by incorporating detuned RF pulses to increase the visibility of spin phase oscillations [2]. This approach is particularly valuable for DC magnetometry applications.

The sequence consists of [2]:

- Initial and final π/2 pulses with detuning Δ

- Free precession time Ï„

- Central π pulse with opposite detuning -Δ

The general expression of the Hahn-Ramsey signal is [2]: [ s(2\tau) = \langle \uparrow | R^\dagger(\theta,\pi/2) U^\dagger(0,\tau) R^\dagger(-\theta,\pi) U^\dagger(\tau,2\tau) \times R^\dagger(\theta,\pi/2) \sigma_z R(\theta,\pi/2) \times U(\tau,2\tau) R(-\theta,\pi) U(0,\tau) R(\theta,\pi/2) | \uparrow \rangle ]

This scheme achieves a visibility of the Ramsey fringes comparable to or longer than the Hahn-echo Tâ‚‚ time and provides improved sensitivity to DC magnetic fields [2].

Learning Dynamical Decoupling (LDD)

Recent advances demonstrate that DD performance can be improved by optimizing rotational gates to tailor them to specific quantum hardware [3]. This approach, termed Learning Dynamical Decoupling (LDD), uses closed-loop optimization to find optimal DD sequences without precise knowledge of the noise model.

The LDD protocol [3]:

- Initialization: Start with a base DD sequence (e.g., CPMG or XY4)

- Parameterization: Parameterize the rotation angles in the DD sequence

- Cost Function Evaluation: Execute sequence on quantum hardware and measure cost function

- Classical Optimization: Use optimizer to find parameters that minimize cost function

- Iteration: Repeat until convergence to optimal sequence

This approach has been shown to outperform canonical decoupling sequences like CPMG and XY4 in suppressing noise in superconducting qubits [3].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Dynamical Decoupling Experiments

| Component | Specifications | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qubit Platform | Superconducting transmon, NV center, trapped ions | Physical qubit implementation for DD experiments | TunableTransmonQubit with drivelofrequency = 6.4e9 Hz [5] |

| Control System | Arbitrary waveform generators, RF sources | Precise timing and generation of DD pulses | SHFQC+ instrument with 6 signal generation channels [5] |

| DD Pulse Library | Gaussian, SINC, DRAG pulses | Implement rotation gates with minimal error | Gaussian edge pulses with sigma = 0.25 [5] |

| Optimization Framework | Closed-loop optimal control algorithms | Hardware-tailored DD sequence optimization | COBYLA or Bayesian optimizers [3] |

| Noise Characterization Tools | Ramsey, spin echo, Tâ‚, Tâ‚‚ measurements | Quantify noise properties and DD performance | Free induction decay measurements [2] |

Applications in Quantum Chemistry Computations

Protecting Quantum Simulations

For quantum chemistry computations, dynamical decoupling enables more accurate simulations of molecular systems by protecting quantum coherence during computation [4]. Specific applications include:

- Molecular energy calculations: Protecting quantum states during variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) algorithms for estimating molecular ground-state energies

- Chemical dynamics simulations: Maintaining coherence during time evolution of molecular systems

- Reaction pathway exploration: Enabling longer quantum circuits for studying chemical reactions

Error Suppression for Practical Quantum Advantage

Current quantum computers suffer from noise that limits their computational capabilities [3]. Dynamical decoupling serves as a critical error suppression method to increase circuit depth and result quality on noisy hardware [3]. This is particularly important for quantum chemistry applications, where problems like simulating cytochrome P450 enzymes or iron-molybdenum cofactor (FeMoco) may require millions of physical qubits [4]. Protecting these computations with DD sequences can substantially reduce resource requirements.

Diagram: Integration of Dynamical Decoupling in Quantum Chemistry Workflow showing how DD sequences are inserted into quantum circuits to suppress environmental noise during chemical computations.

From its origins in the simple yet profound Hahn spin echo to modern optimized sequences, dynamical decoupling has evolved into an essential technique for quantum computation and quantum chemistry applications. The core principle of refocusing unwanted phase accumulation through precisely timed control pulses provides a powerful method to combat decoherence in noisy quantum systems.

For researchers in quantum chemistry and drug development, understanding and implementing these protocols is crucial for leveraging current and near-term quantum computers. As quantum hardware continues to advance, with error correction milestones being demonstrated in 2025 [6], dynamical decoupling will remain a vital component of the quantum toolkit, enabling more accurate simulations of molecular systems and bringing practical quantum advantage closer to reality.

Dynamical decoupling (DD) is a powerful technique widely applied in quantum information science to suppress the decoherence of qubits by averaging out unwanted environment-system coupling [7]. In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, quantum technologies face fundamental constraints from qubit decoherence and control errors, which present significant challenges to achieving quantum advantages [7]. While quantum error correction原则上 can eliminate these errors, it requires stringent error rates and substantial physical qubit overhead that remain beyond current technological capabilities [7]. Dynamical decoupling addresses this challenge by applying carefully designed pulse sequences that effectively "average out" the detrimental interactions between a quantum system and its environment, thereby extending coherence times and preserving quantum information.

The technique has demonstrated significant utility across multiple quantum platforms, including nuclear spins, solid-state spin defects, neutral atoms, superconducting circuits, trapped ions, semiconductor quantum dots, and paramagnetic molecules [7]. Beyond mere coherence preservation, dynamical decoupling enables critical applications in Hamiltonian engineering for quantum simulation, noise spectrum reconstruction, sensitive quantum metrology, and state protection in quantum computing [7]. However, traditional dynamical decoupling implementations face substantial limitations from control errors, which can accumulate throughout pulse sequences and significantly compromise their effectiveness.

Theoretical Foundation

Basic Principles of Decoherence Suppression

At its core, dynamical decoupling operates on the principle of repeatedly applying control pulses to a quantum system to effectively average out its interactions with the environment. This approach is analogous to the "spin-echo" technique in nuclear magnetic resonance but extends it to more sophisticated pulse sequences. The fundamental mechanism involves applying a sequence of inversion pulses (Ï€ pulses) that reverse the time evolution of the quantum system, effectively canceling out the effects of slow environmental noise.

The mathematical foundation rests on the filter-function formalism, where the DD sequence acts as a high-pass filter that suppresses low-frequency noise components. For a qubit with resonant frequency dominating the Hamiltonian, the quantum state can be described by coherence orders p = ±1, 0 corresponding to S± = Sx ± iSy and Sz, respectively, where Sx,y,z are Pauli matrices [7]. The p = ±1 states represent coherence undergoing decoherence with characteristic time T₂, while p = 0 represents population undergoing relaxation with characteristic time T₠[7].

The Control Error Challenge

Despite its theoretical promise, practical dynamical decoupling implementation faces significant challenges from control errors. Non-robust sequences like UDD become impractical to implement, while robust ones like CPMG tend to significantly overestimate decoherence times [7]. This overestimation problem has remained largely unaddressed for decades, leading to numerous reports of exceptionally long yet plausible decoherence times across various qubit platforms that may not reflect true performance [7].

Control errors primarily manifest as imperfections in the inversion pulses, which can induce unintended coherence-order changes (Δp = ±1) and cause coherence-population mixing [7]. This generates undesired coherence transfer pathways that contaminate experimental results and lead to inaccurate measurements of true decoherence times. The problem is particularly acute in systems where the relaxation time (Tâ‚) well exceeds Tâ‚‚ and where single gate fidelity is relatively low [7].

Table 1: Classification of Dynamical Decoupling Sequences and Their Characteristics

| Sequence Type | Representative Sequences | Robustness to Control Errors | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-robust | UDD | Low | Theoretical studies, ideal systems |

| Robust | CPMG, XY-8, XY-16 | Moderate | Decoherence time measurement, noise spectroscopy |

| Phase-cycled | Hadamard phase cycling | High | Accurate Tâ‚‚ measurement, quantum error mitigation |

Phase Cycling for Error Mitigation

The Phase Cycling Approach

Phase cycling emerges as a powerful quantum error mitigation (QEM) strategy to address control errors in dynamical decoupling. This technique employs a set of functionally equivalent quantum circuits that leverage phase degree of freedom, with systematically designed phase configurations that classify qubit dynamics based on their evolution pathways [7]. The approach selectively extracts desired dynamics (error-free channels) by averaging observables obtained from all circuits in the ensemble.

Traditional two-step phase cycling (TPC) proves sufficient only when all pulses are error-free, but becomes inadequate under realistic conditions with noisy inversion pulses [7]. These pulses induce unintended coherence-order changes and cause coherence-population mixing, generating two distinct types of echoes: desired echoes reflecting pure decoherence (pathways with only p = ±1 states) and undesired echoes that undergo intermittent relaxation processes (pathways involving p = 0 states) [7]. In standard CPMG experiments, these echoes overlap, causing TPC to significantly overestimate T₂ and leading to positively biased, misleading assessment of qubit performance [7].

Hadamard Phase Cycling Protocol

Hadamard phase cycling represents an advanced quantum error mitigation method specifically designed for inversion-pulse-based dynamical decoupling (IDD) sequences, including CP, CPMG, XY-8, XY-16, and UDD [7]. This protocol exploits group structure to design phase configurations of equivalent ensemble quantum circuits, effectively eliminating circuit outputs generated from erroneous dynamics with scaling that is linear with circuit depth [7].

The complete error mitigation of control errors would theoretically require exponential scaling with circuit depth according to the selection rule of coherence-only dynamic processes. However, Hadamard phase cycling achieves effective mitigation with linear scaling by designing quantum circuits whose phase configurations form an abelian group [7]. This makes the approach practical for implementation on current quantum hardware while maintaining high effectiveness.

Diagram 1: Phase cycling workflow for coherence pathway separation

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Hadamard Phase Cycling Implementation Protocol

Objective: Implement Hadamard phase cycling to mitigate control errors in inversion-pulse-based dynamical decoupling sequences for accurate decoherence time measurement.

Materials Required:

- Quantum processor or ensemble qubit system

- Pulse sequence generator with phase control capability

- Detection system for quantum state measurement

- Data processing unit for signal averaging

Procedure:

Initial System Characterization

- Measure baseline Tâ‚ and approximate Tâ‚‚ without dynamical decoupling

- Characterize single gate fidelity and pulse error rates

- Identify optimal pulse intervals based on system parameters

Phase Configuration Design

- Design an abelian group of phase configurations for the target DD sequence

- Ensure linear scaling with circuit depth (N configurations for N-pulse sequence)

- Enforce orthogonality conditions between desired and undesired pathways

Ensemble Circuit Execution

- Implement the base dynamical decoupling sequence (CPMG, XY-8, etc.)

- For each phase configuration in the Hadamard set:

- Apply phase shifts to all pulses according to the configuration

- Execute the complete pulse sequence

- Measure the final quantum state observable

- Repeat each configuration for sufficient averaging to overcome statistical noise

Signal Processing and Reconstruction

- Compute the weighted average of observables across all phase configurations

- Apply pathway selection rules to isolate desired coherence signals

- Reconstruct the pure decoherence signal without control error contamination

Decoherence Time Extraction

- Fit the processed decay curve to exponential or stretched exponential model

- Extract accurate Tâ‚‚ value from the fitted parameters

- Calculate confidence intervals through statistical analysis

Validation Metrics:

- Consistency of extracted Tâ‚‚ across different sequence types

- Agreement with theoretical predictions for model systems

- Improvement in state fidelity preservation for quantum memory applications

Experimental Validation Across Qubit Platforms

The Hadamard phase cycling protocol has been experimentally validated across multiple quantum platforms, demonstrating its broad applicability and effectiveness:

Ensemble Electron Spin Qubits:

- System: Cu²âº-based molecular qubits at 8 K

- Sequence: Modified CPMG with Hadamard phase cycling

- Results: Successful separation of desired and undesired echoes, revealing true T₂ of 7.33 μs compared to significantly overestimated values from conventional methods [7]

- Significance: Demonstrated more than 600 times faster decay for desired echoes compared to undesired echoes, highlighting the critical importance of proper error mitigation [7]

Nitrogen-Vacancy Centers in Diamond:

- Application: Accurate acquisition of decoherence times under control errors

- Performance: Significant enhancement of measured Tâ‚‚ accuracy

- Utility: Reliable characterization of qubit performance for quantum sensing applications

Single Trapped Ion Qubits:

- System: Single â´â°Ca⺠ion qubits

- Metric: State fidelity preservation during dynamical decoupling

- Results: Near-quantitative effective state fidelity achievement with Hadamard phase cycling

Superconducting Qubits:

- System: Superconducting transmon qubits

- Challenge: Significant control errors in microwave pulses

- Outcome: Effective preservation of state fidelity during dynamical decoupling sequences

Table 2: Experimental Results of Hadamard Phase Cycling Across Qubit Platforms

| Qubit Platform | Key Metric | Conventional DD | With Hadamard Phase Cycling | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu²⺠Molecular Qubits | Measured T₂ | Significantly overestimated | 7.33 μs | >600× for desired vs. undesired echo decay |

| NV Centers in Diamond | Tâ‚‚ accuracy | Positively biased | Accurate acquisition | Qualitative improvement |

| Trapped â´â°Ca⺠Ions | State fidelity | Reduced by control errors | Near-quantitative preservation | Significant for quantum memory |

| Superconducting Transmons | State fidelity | Compromised | Effectively preserved | Essential for reliable operation |

Application in Quantum Chemistry for Drug Discovery

Relevance to Quantum Computational Chemistry

In the context of quantum chemistry computations for drug discovery, dynamical decoupling with proper error mitigation plays a crucial role in enabling accurate quantum simulations on NISQ-era hardware. Quantum chemistry methods using quantum mechanics to model molecules and molecular processes are cornerstones of modern computational chemistry [8]. These methods provide fine descriptions of receptor-ligand interactions and chemical reactions, making them increasingly valuable for drug design and discovery [9].

The application of quantum chemistry in drug discovery faces significant challenges, particularly for systems containing metal ions in binding sites, design of highly selective inhibitors, optimization of bi-specific compounds, understanding enzymatic reactions, and studying covalent ligands and prodrugs [9]. Dynamical decoupling with error mitigation can enhance the reliability of quantum computations for these applications by extending qubit coherence times and preserving quantum state fidelity throughout complex calculations.

Specific Applications in Drug Discovery

Binding Affinity Calculations:

- Quantum mechanics methods provide more accurate binding affinity predictions than classical molecular mechanics

- DD protocols preserve quantum coherence during extended quantum phase estimation algorithms

- Enhanced accuracy for systems with metal ions or charge transfer complexes

Reaction Mechanism Elucidation:

- Modeling of enzymatic reaction pathways requires sustained quantum coherence

- Phase-cycled DD enables accurate simulation of reaction coordinate evolution

- Critical for understanding covalent inhibition and prodrug activation

Force Field Parameterization:

- QM calculations generate reference data for molecular mechanics force fields

- Improved computational accuracy through error-mitigated quantum computations

- Enhanced predictive power for QSAR/QSPR models in drug design

Diagram 2: DD workflow in drug discovery computations

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Platforms for Dynamical Decoupling Experiments

| Material/Platform | Function in DD Research | Specific Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Qubits | Test platform for DD protocols | Cu²âº-based molecules | Well-defined spin states, tunable coordination environments |

| Solid-State Defects | Quantum sensing and memory | NV centers in diamond | Long coherence times, optical addressability |

| Trapped Ions | High-fidelity quantum operations | â´â°Ca⺠ions | Excellent quantum control, long coherence times |

| Superconducting Qubits | Scalable quantum processing | Transmon qubits | Fast gate operations, scalable architecture |

| Pulse Generators | DD sequence implementation | Arbitrary waveform generators | Nanosecond timing resolution, phase control |

| Cryogenic Systems | Qubit environment control | Dilution refrigerators | Millikelvin temperatures, low vibration |

Dynamical decoupling represents a critical technique for mitigating environmental decoherence in quantum systems, with particular relevance to quantum chemistry computations in drug discovery research. The implementation of phase cycling methods, specifically Hadamard phase cycling, addresses long-standing challenges with control errors that have compromised accurate decoherence time measurement and state fidelity preservation across diverse quantum platforms.

The integration of scalable quantum error mitigation with dynamical decoupling suppression facilitates the development of quantum technologies with noisy qubits and control hardware, directly impacting the reliability of quantum chemistry calculations for drug design applications [7]. As quantum computational approaches become increasingly integrated into standard computer-aided drug design toolsets [9], robust dynamical decoupling protocols will play an essential role in ensuring the accuracy and predictive power of these methods for critical pharmaceutical applications including binding affinity prediction, reaction mechanism elucidation, and force field parameterization.

The experimental validation of Hadamard phase cycling across multiple qubit platforms—from ensemble molecular spins to single trapped ions and superconducting qubits—demonstrates its broad applicability and effectiveness in overcoming control errors that have previously limited dynamical decoupling performance. This advancement enables more accurate characterization of quantum systems and enhanced preservation of quantum information, ultimately supporting more reliable quantum computations for drug discovery challenges.

Dynamical decoupling (DD) is an open-loop quantum control technique employed to suppress decoherence in quantum systems, a critical challenge for realizing practical quantum computers. Its fundamental principle is to apply rapid, time-dependent control pulses that approximate the averaging of unwanted system-environment interactions to zero [1]. For quantum chemistry computations, where simulating molecular systems requires maintaining qubit coherence for extended periods, DD provides a low-overhead method for protecting quantum information without the full resource requirements of quantum error correction [10]. The sequences explored in this application note—CPMG, UDD, and CDD—represent key milestones in the evolution of DD design, each offering distinct advantages for specific experimental conditions and noise environments.

Theoretical Foundation and Sequence Specifications

Fundamental Operating Principle

The theoretical foundation of DD is most effectively described using Average Hamiltonian Theory (AHT). The goal is to transform the total system-bath Hamiltonian, through the application of a controlled sequence of pulses, such that the error terms in the effective (average) Hamiltonian are canceled to the highest possible order [1]. The analysis begins with the total Hamiltonian:

[H{\text{total}}(t) = H{\text{sys}} + H{\text{ctrl}}(t) + H{\text{err}}]

where ( H{\text{ctrl}}(t) ) represents the DD control pulses and ( H{\text{err}} ) encapsulates the noise to be suppressed. By moving into the interaction picture (the "toggling frame"), the error Hamiltonian becomes modulated by the control pulses: ( \tilde{H}{\text{err}}(t) = Uc^\dagger(t) H{\text{err}} Uc(t) ). The Magnus expansion is then used to express the total evolution over one cycle period ( T ) in terms of an effective Hamiltonian: ( U{\text{err}}(T) = \exp(-iH{\text{eff}}T) ). A successful DD sequence is one that makes the leading terms of ( H_{\text{eff}} ) vanish [1].

Sequence Architectures and Timing Diagrams

The following dot code defines the logical structure and pulse timing for the three primary DD sequences.

Quantitative Sequence Comparison

Table 1: Performance and Characteristic Comparison of Common DD Sequences

| Sequence | Pulse Spacing | Order of Error Suppression | Robustness to Pulse Imperfections | Experimental Complexity | Optimal Noise Spectrum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPMG | Uniform, equally spaced | First-order | High (compensates over-rotation errors) [1] | Low | Slow noise, large low-frequency component [11] |

| UDD | Non-uniform, optimized ( \delta_j = T \sin^2\left(\frac{\pi j}{2n+2}\right) ) [1] | High-order (n pulses suppress to n-th order for pure dephasing) [1] | Moderate | Moderate | Noise with sharp high-frequency cutoff [1] |

| CDD | Recursively defined | Theoretically arbitrary high-order (increases with concatenation level) [1] | Varies with level | High (exponential pulse growth) | General time-varying noise |

Experimental Performance and Protocol

Empirical Performance Survey on Superconducting Qubits

A large-scale survey of DD performance across 60 sequences was conducted on IBM Quantum superconducting-qubit processors, providing critical comparative data [12]. The study assessed the ability of various sequences to preserve an arbitrary single-qubit state, a fundamental task for quantum memory. Key findings include:

- High-order sequences like universally robust (UR) DD and quadratic DD (QDD) generally outperformed other sequences across multiple devices and pulse interval settings [12].

- Performance optimization for basic sequences like CPMG and XY4 was achievable by optimizing the pulse interval, not necessarily using the minimum possible interval. The optimal interval was often substantially larger than the minimum device capability [12].

- Robust DD sequences were identified as the preferred choice over traditional counterparts, especially as systematic and random control errors are reduced in future hardware [12].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics from IBMQ Hardware

| Sequence Family | Relative State Preservation Fidelity | Sensitivity to Pulse Interval | Remarks from Experimental Survey |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic (Hahn, CPMG, XY4) | Good | High (performance tunable via interval optimization) | Nearly matches high-order sequence performance with optimized interval [12] |

| High-Order (CDD, UDD, QDD, NUDD, UR) | Excellent | Consistent across devices and settings | Statistically superior for short pulse intervals; advantage diminishes with sparser placement [12] |

| Unprotected Evolution | Baseline (Poor) | N/A | Used as a reference for performance comparison [12] |

Detailed Protocol: Implementing CPMG for Quantum Memory

Objective: To suppress dephasing noise and extend coherence time during an idle period of a quantum computation, such as between gate operations in a quantum chemistry simulation.

Principle: The CPMG sequence is a periodic, equally-spaced sequence of π-pulses. The key innovation is the application of π-pulses along an axis perpendicular to the initial qubit state, which provides inherent robustness against pulse rotation errors. If one pulse over-rotates, the next pulse in the sequence induces an opposite effect, canceling the error to first order [1].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Initialization: Prepare the qubit in an arbitrary superposition state in the equatorial plane of the Bloch sphere (e.g., ( |+ \rangle = \frac{|0\rangle + |1\rangle}{\sqrt{2}} )).

- First Free Evolution Period: Allow the system to evolve freely for a duration of ( \tau/2 ).

- Apply π-Pulse: Apply a strong, fast π-pulse around the y-axis (assuming initial state along x). This pulse effectively inverts the accumulated phase of the qubit.

- Second Free Evolution Period: Allow the system to evolve freely for a full period ( \tau ).

- Repeat Pulses and Evolution: Continue applying a π-pulse followed by a free evolution period of ( \tau ). Repeat this pattern for the desired number of pulses, ( n ).

- Final Free Evolution Period: After the final π-pulse, allow a final free evolution period of ( \tau/2 ).

- Measurement: Measure the final state of the qubit to determine the preservation fidelity.

Critical Parameters:

- Total Sequence Time (T): The total duration the qubit is idle and requires protection.

- Number of Pulses (n): More pulses provide more frequent refocusing but also introduce more potential errors from imperfect pulses.

- Pulse Interval (τ): The time between the centers of consecutive π-pulses. This is a key parameter to optimize for a given device and noise environment [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DD Experiments

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cloud-Based Quantum Processors | Provides the physical experimental testbed for implementing and benchmarking DD sequences. | IBM Quantum (IBMQ) superconducting transmon qubit devices (e.g., ibmqarmonk, ibmqbogota) [12]. |

| Open-Pulse Level Control | Enables precise control over the timing, shape, and duration of DD pulses, which is crucial for advanced sequences. | Open-pulse functionality within the IBM Quantum Experience platform [12]. |

| Arbitrary Waveform Generators (AWGs) | Generates the precise time-varying control signals needed to implement DD pulses on the qubit. | Standard equipment in experimental quantum computing labs. |

| Genetic Algorithm Optimization | A classical optimization technique used to empirically tailor DD strategies for specific hardware and circuits. | GADD (Genetic Algorithm-inspired DD) can find sequences outperforming canonical ones [10]. |

| State Tomography/Randomized Benchmarking | Provides the metrics to quantify the performance of a DD sequence in preserving quantum states or gate fidelities. | Used to measure state preservation fidelity and sequence performance [12] [10]. |

| Guaiacol | Guaiacol | |

| PAR-2-IN-2 | PAR-2-IN-2, MF:C25H20F3N5O2, MW:479.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between CPMG, UDD, and CDD is not unilateral but depends on the specific experimental context. CPMG offers a robust, straightforward protocol highly effective against low-frequency noise. UDD provides superior, high-order protection for a fixed number of pulses, ideal for environments with specific spectral characteristics. CDD offers a systematic path to arbitrarily high-order decoupling, though its practical implementation is constrained by the exponential growth in pulse number.

Future research in quantum chemistry computations will likely leverage empirical learning techniques, such as genetic algorithms, to tailor DD strategies directly to the specific noise profile of a quantum processor and the structure of a target quantum circuit [10]. This data-driven approach has already demonstrated significant improvements over canonical sequences, particularly as circuit size and complexity increase. Furthermore, the challenge of suppressing multi-qubit crosstalk in large-scale quantum chemistry simulations remains an active frontier, driving the development of staggered DD and other multi-qubit protection schemes [10].

Average Hamiltonian Theory (AHT) and the Magnus expansion provide the fundamental mathematical framework for understanding and designing dynamical decoupling (DD) protocols in quantum computing and quantum chemistry simulations. These techniques are essential for mitigating decoherence, a significant obstacle in near-term quantum applications, including the simulation of chemical systems for drug development. AHT allows for the analysis of complex, time-dependent control sequences by describing their net effect through a single, time-independent effective Hamiltonian [1] [13]. The theory was initially developed for nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and has since become a cornerstone for quantum control, enabling the design of pulse sequences that suppress unwanted interactions between a quantum system and its environment [13]. The Magnus expansion provides the rigorous mathematical toolset to compute this effective Hamiltonian, offering an exponential representation of the solution to time-dependent linear differential equations [14]. Within the context of quantum chemistry computations, applying these principles through dynamical decoupling is critical for extending qubit coherence times, thereby enabling more complex and accurate molecular simulations on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices [15].

Mathematical Foundation of the Magnus Expansion

The Magnus expansion offers a formal solution to a first-order homogeneous linear differential equation for a linear operator [14]. Given a system described by the equation ( Y'(t) = A(t)Y(t) ), with the initial condition ( Y(t0) = Y0 ), the solution is expressed in exponential form as ( Y(t) = \exp(\Omega(t, t0)) Y0 ). The core of the expansion lies in representing the operator ( \Omega(t) ) as an infinite series: [ \Omega(t) = \sum{k=1}^{\infty} \Omegak(t) ] The first four terms in the Magnus expansion are given by [14]: [ \begin{aligned} \Omega1(t) &= \int{0}^{t} A(t1) \, dt1, \ \Omega2(t) &= \frac{1}{2} \int{0}^{t} dt1 \int{0}^{t1} dt2 \,[A(t1), A(t2)], \ \Omega3(t) &= \frac{1}{6} \int{0}^{t} dt1 \int{0}^{t1} dt2 \int{0}^{t2} dt3 \, \left( [A(t1), [A(t2), A(t3)]] + [A(t3), [A(t2), A(t1)]] \right), \ \Omega4(t) &= \frac{1}{12} \int{0}^{t} dt1 \int{0}^{t1} dt2 \int{0}^{t2} dt3 \int{0}^{t3} dt4 \, \left( [[[A1,A2],A3],A4] + [A1,[[A2,A3],A4]] + [A1,[A2,[A3,A4]]] + [A2,[A3,[A4,A1]]] \right) \end{aligned} ] Here, ( [A, B] \equiv A B − B A ) denotes the matrix commutator. A sufficient condition for the convergence of this series for ( t \in [0, T) ) is ( \int{0}^{T} \|A(s)\|_{2} ds < \pi ) [14]. The key advantage of using the Magnus expansion in quantum mechanics is that the truncated series preserves important qualitative properties of the exact solution, such as unitarity, which is essential for quantum time evolution [14].

Average Hamiltonian Theory in Dynamical Decoupling

Core Principles and Formalism

Average Hamiltonian Theory leverages the Magnus expansion to describe the net effect of a periodic control sequence, such as a dynamical decoupling pulse sequence, applied to a quantum system. The total Hamiltonian of a system coupled to an environment is: [ H{\text{total}}(t) = H{\text{sys}} + H{\text{ctrl}}(t) + H{\text{err}} ] where ( H{\text{ctrl}}(t) ) represents the time-dependent control pulses and ( H{\text{err}} ) is the error Hamiltonian representing unwanted noise or couplings [1]. The goal of a DD sequence is to design ( H{\text{ctrl}}(t) ) such that the effective average Hamiltonian, derived via the Magnus expansion, cancels out ( H{\text{err}} ) to the highest possible order.

The analysis is performed in the "toggling frame," an interaction picture defined by the control pulses. In this frame, the error Hamiltonian is modulated as ( \tilde{H}{\text{err}}(t) = Uc^{\dagger}(t) H{\text{err}} Uc(t) ), where ( Uc(t) ) is the evolution under the control pulses [1]. The total evolution over one DD cycle of period ( T ) is then described by an effective time-independent Hamiltonian ( H{\text{eff}} ): [ U{\text{err}}(T) = \mathcal{T} \exp \left( -i \int{0}^{T} \tilde{H}{\text{err}}(t') dt' \right) = \exp(-i H{\text{eff}} T) ] where ( H{\text{eff}} ) can be expressed as a series ( H{\text{eff}} = \bar{H}^{(0)} + \bar{H}^{(1)} + \bar{H}^{(2)} + \dots ) using the Magnus expansion. The first-order (zeroth-order in the Magnus terminology used in [1]) term is the average Hamiltonian: [ \bar{H}^{(0)} = \frac{1}{T} \int{0}^{T} \tilde{H}{\text{err}}(t) dt ] A first-order decoupling sequence is designed to make ( \bar{H}^{(0)} = 0 ). The second-order term is: [ \bar{H}^{(1)} = -\frac{i}{2T} \int{0}^{T} dt2 \int{0}^{t2} dt1 [\tilde{H}{\text{err}}(t2), \tilde{H}{\text{err}}(t_1)] ] Higher-order sequences, such as Uhrig Dynamical Decoupling (UDD) and Concatenated Dynamical Decoupling (CDD), aim to nullify these higher-order terms for superior noise suppression [1].

Conceptual Workflow of AHT

The following diagram illustrates the logical process of applying Average Hamiltonian Theory to analyze a dynamical decoupling sequence.

Standard Dynamical Decoupling Protocols and Their Average Hamiltonians

The following table summarizes key dynamical decoupling sequences, their structures, and the properties of their resulting average Hamiltonians [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Standard Dynamical Decoupling Sequences

| Sequence Name | Pulse Sequence Structure | Average Hamiltonian Properties | Key Applications & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hahn Spin Echo | Free evolution (τ) — π-pulse — Free evolution (τ) | Cancels static dephasing noise to first order ( ( \bar{H}^{(0)} = 0 ) ). Ineffective against fast noise [1]. | Foundation of DD; basic refocusing [1]. |

| Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) | Free evolution (τ/2) — (π-pulse) — Free evolution (τ) — (π-pulse) — ... — Free evolution (τ/2) | First-order decoupling; robust to pulse errors due to phase alignment [1]. | High-fidelity data storage; NMR; NV centers [1]. |

| Uhrig Dynamical Decoupling (UDD) | Non-uniformly spaced π-pulses. j-th pulse time: ( \delta_j = T \sin^2\left( \frac{\pi j}{2n+2} \right) ) | Higher-order suppression of general dephasing noise, optimized for specific noise spectra [1]. | Superior performance with fewer pulses for noise with high-frequency cutoff [1]. |

| Concatenated DD (CDD) | Recursive construction. CDD-1 = Hahn echo. CDD-n replaces free evolution in CDD-(n-1) with full CDD-(n-1) sequence. | Systematically cancels noise to arbitrarily high order in theory [1]. | Number of pulses grows exponentially with concatenation level; challenging to implement [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating AHT for a Two-Pulse Echo Sequence

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for AHT Validation Experiments

| Item Name | Specifications / Function |

|---|---|

| Quadrupolar Spin Samples | Powdered samples containing spin I=1, I=3/2 (e.g., NaNO₃), or I=5/2 (e.g., AlCl₃) nuclei. Serves as the quantum system for testing [16]. |

| NMR Spectrometer | High-field NMR system (e.g., Varian UNITY NMR) with solid-state NMR probes for applying RF pulses and detecting signals [16]. |

| Arbitrary Waveform Generator | Hardware for generating precise, timed radio-frequency (RF) control pulses with defined phase, duration, and amplitude [16]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

This protocol outlines an experiment to probe the validity of AHT for a simple two-pulse echo sequence on a quadrupolar spin system, as detailed in [16].

System Preparation

- Place a powdered sample of NaNO₃ (for I=3/2) or AlCl₃ (for I=5/2) into a solid-state NMR probe.

- Insert the probe into a high, static magnetic field ( B_0 ) generated by the NMR spectrometer. This field defines the quantisation axis for the spins.

Pulse Sequence Execution

- Apply the two-pulse echo sequence: ( (\pi/2){x} - \tau - \pi{x} - \tau - \text{Acquire} ).

- Systematically vary the experimental parameters:

- Pulse Spacing (Ï„): Measure over a range from short to long values.

- Pulse Width: Perform experiments with different pulse durations.

- Quadrupolar Coupling Constant (( \omega_Q )): Use samples with different known coupling strengths.

Data Acquisition and Phase Cycling

- Record the resulting NMR signal (echo).

- Implement a phase cycling scheme on the RF pulses (e.g., varying the phase of the ( \pi ) pulse). This technique helps suppress spurious artifacts and isolate the desired signal, as predicted by AHT [16].

Computational Validation

- AHT Calculation: Compute the first-order average Hamiltonian ( \bar{H}^{(0)} ) for the two-pulse sequence, taking into account the system's evolution under the first-order quadrupolar interaction ( H_Q ) during the finite-width RF pulses.

- Numerical Simulation: Solve the Von Neumann equation ( \frac{d\rho}{dt} = -i[H, \rho] ) numerically for the exact same parameters, where ( H ) is the total time-dependent Hamiltonian. This provides a benchmark for the AHT prediction.

Data Analysis and Comparison

- Compare the simulated echo signal from the AHT approach with the exact numerical result.

- Quantify the accuracy of AHT by analysing the deviations as a function of Ï„, pulse width, and ( \omega_Q ).

- Compare the final acquired experimental spectra with and without the phase cycling scheme to validate the artifact suppression predicted by the AHT analysis.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The workflow for the experimental validation protocol is summarized below.

Advanced Considerations and Recent Developments

Limitations and Breakdown of AHT

While powerful, AHT has limitations. Its predictions are accurate only in the perturbative limit, where the product of the error Hamiltonian strength and the cycle time is small. In many practical quantum sensing scenarios, such as with solid-state spins, this condition is violated, leading to a breakdown of AHT [13]. Convergence can also fail for systems with large internal couplings or when using long pulse sequences [17] [16]. For instance, studies on spin I=3/2 and I=5/2 nuclei show that AHT accurately predicts dynamics only for short delay times (Ï„), small bandwidths, and short RF pulses [16]. Furthermore, AHT typically assumes ideal, instantaneous pulses; accounting for finite pulse widths and errors introduces significant complexity [18] [16].

"Beyond AHT" Approaches and Current Research

Recent research focuses on methods that operate beyond the valid regime of AHT.

- Exact Methods: One approach is to develop exact analytical or numerical methods to evaluate the sensor response to a target field, bypassing the limitations of the Magnus expansion entirely [13].

- Symmetries: It has been established that certain symmetries in pulse sequences, such as rapid echoes, can allow the Magnus expansion to remain accurate even beyond its general convergence limit [13].

- Advanced Sequence Design: New DD sequences continue to be developed. For example, the recent "Topological Dynamical Decoupling" (Tn) family achieves complete cancellation of pulse area errors to all orders by enforcing a topological phase condition, a significant advancement for hardware-efficient error suppression [19].

- Hybrid Quantum-Classical Workflows: In quantum chemistry, DD is a key enabling technology. It has been used in demonstrations of unconditional exponential quantum scaling advantage [15] and is integrated into hybrid HPC-QPU workflows that combine quantum computing with classical molecular dynamics and embedding techniques to study complex systems like proton transfer in water [20].

These developments ensure that AHT and its extensions remain at the forefront of enabling robust quantum computation and simulation.

The Problem of Decoherence in Quantum Chemistry Computations

Quantum chemistry stands to be revolutionized by quantum computation, which offers the potential to exactly solve the electronic structure problem for complex molecules and materials. However, contemporary quantum processing units (QPUs) operate in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, characterized by limited qubit counts and vulnerability to environmental noise [21]. Among these noise sources, decoherence presents a fundamental challenge, causing the loss of quantum information and corrupting computational results before algorithms can complete execution. This application note examines the specific impacts of decoherence on quantum chemical calculations and details the experimental methodology for employing dynamical decoupling protocols to mitigate these effects, thereby enhancing the reliability of computed molecular energies and properties.

Understanding Decoherence and Its Impact on Quantum Chemistry

Fundamental Mechanisms of Decoherence

Decoherence is the process by which a quantum system loses its quantum behavior, such as superposition and entanglement, due to interactions with its environment, causing it to behave classically [22]. This manifests through several mechanisms:

- Dephasing: A random phase accumulation between the |0⟩ and |1⟩ components of a qubit's superposition state, which degrades quantum interference without changing energy populations [21].

- Damping: The loss of energy from the qubit to its environment, leading to the decay of excited states [21].

- Depolarization: A random, undifferentiated perturbation that pushes the qubit state toward the maximally mixed state [21].

From a quantum information perspective, decoherence occurs when a qubit becomes entangled with its environment. This sharing of quantum information effectively "measures" the system, collapsing fragile superpositions and destroying the quantum correlations essential for computation [23] [24] [22].

Consequences for Chemical Property Calculations

In quantum chemistry, the electronic energy is a functional of the one- and two-particle reduced density matrices (1- and 2-RDMs) [21]. These matrices must obey physical N-representability constraints. Noise from decoherence produces corrupted RDMs that violate these constraints, leading to unphysical results, such as inaccurate ground state energies and molecular properties [21]. Furthermore, decoherence directly limits the depth of quantum circuits that can be executed reliably, preventing the implementation of complex, deep algorithms required for high-accuracy chemical simulations [22].

Table 1: Primary Decoherence Mechanisms and Their Effects on Quantum Chemical Calculations

| Mechanism | Primary Effect on Qubit | Impact on Chemical Calculation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dephasing | Loss of phase coherence in superposition states | Incorrect quantum phase interference, leading to erroneous energy eigenvalues | ||

| Damping | Energy relaxation from | 1⟩ to | 0⟩ state | Corruption of electronic excited state populations and properties |

| Depolarization | Random, undifferentiated state mixing | Complete loss of quantum information, rendering all computed properties invalid | ||

| Shot Noise | Statistical uncertainty from finite measurements | Uncertainty in measured RDMs and final computed energies [21] |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Decoherence

This section provides a detailed methodology for quantifying decoherence in a qubit system intended for chemical computations. The following workflow outlines the complete experimental process from preparation to data analysis.

Protocol for Measuring Qubit Coherence Time (Tâ‚‚)

Objective: To characterize the rate of dephasing in a superconducting qubit by measuring its Ramsey decay time, Tâ‚‚.

Materials and Reagents:

- Dilution refrigerator maintaining a base temperature of < 20 mK

- Superconducting qubit chip (e.g., transmon design)

- Microwave pulse generators with IQ modulation and timing resolution < 1 ns

- Cryogenic amplification chain

- Heterodyne detection system

Procedure:

- Qubit Preparation: Cool the system to its ground state |0⟩.

- State Initialization: Apply a π/2 pulse around the Y-axis to create the superposition state |+⟩ = (|0⟩ + |1⟩)/√2.

- Free Evolution: Allow the qubit to evolve freely for a variable time delay, t.

- Second π/2 Pulse: Apply a second π/2 pulse around the X-axis.

- Measurement: Perform a projective measurement in the computational basis (Z-measurement) to determine the probability P(|1⟩).

- Repetition: Repeat steps 1-5 for a range of delay times t, and for each t, repeat the sequence a sufficient number of times (e.g., 1,024 shots) to estimate P(|1⟩) accurately.

- Data Analysis: Fit the resulting oscillation decay of P(|1⟩) to the form A + B exp(-t/T₂) cos(2πΔft + φ), where Δf is the detuning frequency. The extracted parameter T₂ is the coherence time.

Protocol for Benchmarking Energy Calculation Error Under Noise

Objective: To evaluate the impact of decoherence on the accuracy of a quantum chemical energy calculation for a simple molecule.

Materials and Reagents:

- Quantum computing platform (e.g., superconducting processor or trapped-ion system)

- Classical optimizer for variational algorithms

Procedure:

- Molecule Selection: Select a test molecule (e.g., Hâ‚‚, LiH).

- Hamiltonian Formulation: Map the electronic Hamiltonian of the molecule to a qubit representation using a Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation.

- Algorithm Selection: Implement the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm.

- Noisy vs. Ideal Execution: a. Execute the VQE algorithm on the target NISQ device. b. Simulate the same VQE algorithm on a classical computer using a noise model that includes amplitude damping and dephasing channels parameterized by experimentally measured Tâ‚ and Tâ‚‚ times.

- Reference Calculation: Perform a Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) calculation on a classical computer to obtain the exact, noise-free ground state energy [21].

- Error Quantification: For each computation, calculate the energy error as E_calculated - E_FCI.

- Analysis: Compare the error from the noisy NISQ device execution with the error from the noisy simulation and the ideal simulation.

Dynamical Decoupling as a Mitigation Strategy

Dynamical Decoupling (DD) is an open-loop quantum control technique designed to suppress decoherence by applying rapid, time-dependent control pulses that average unwanted system-environment interactions to zero [1]. The foundational principle, derived from the Hahn spin echo, is to refocus the phase evolution of a qubit by applying a controlling π-pulse that inverts the accumulated phase error, causing it to unwind during a subsequent free evolution period [1].

Standard Dynamical Decoupling Sequences

Table 2: Common Dynamical Decoupling Sequences and Their Properties

| Sequence | Pulse Spacing | Key Feature | Best Suited Noise Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hahn Echo [1] | τ - π - τ | Single refocusing pulse | Quasi-static noise |

| Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) [1] | τ/2 - π - τ - π - ... - τ - π - τ/2 | Robust to pulse errors; even spacing | Low-frequency noise |

| Uhrig Dynamical Decoupling (UDD) [1] | Non-uniform, optimized | Maximally suppresses dephasing for a given number of pulses | Noise with high-frequency cutoff |

Protocol for Implementing a CPMG Sequence

Objective: To extend the coherence time Tâ‚‚ of a qubit by implementing a CPMG dynamical decoupling sequence.

Materials and Reagents:

- Quantum processor with calibrated π-pulses

- Pulse sequencing hardware

Procedure:

- Qubit Initialization: Prepare the qubit in the |+⟩ state using a π/2 pulse.

- First Free Evolution: Allow the qubit to evolve freely for a duration of Ï„/2.

- Pulse Application: Apply a π-pulse (typically around the Y-axis for robustness against pulse errors).

- Second Free Evolution: Allow the qubit to evolve for a full period Ï„.

- Repetition: Repeat steps 3-4 (apply π-pulse, evolve for τ) for the desired number of cycles, N.

- Final Free Evolution: After the final π-pulse, allow a final free evolution of τ/2.

- Measurement: Apply a final π/2 pulse for readout and measure the qubit state.

- Characterization: Repeat the entire sequence for different total sequence times and numbers of pulses N to measure the effective coherence time under DD.

The sequence can be visualized as a periodic refocusing of the qubit's phase, where the timing of pulses is critical for effective error cancellation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Solutions for Decoherence Mitigation Experiments

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Dilution Refrigerator | Cools qubits to milli-Kelvin temperatures to minimize thermal noise (T₠decay) [22]. | Base temperature ≤ 10 mK, with cryogenic wiring and filtering. |

| Cryogenic Amplifier | Boosts weak quantum signals at low temperatures while adding minimal noise. | HEMT amplifier, noise temperature ~ 3 K, mounted at 4 K stage. |

| Arbitrary Waveform Generator (AWG) | Generates precise, high-fidelity control pulses for qubit gates and DD sequences. | Sampling rate ≥ 1 GSa/s, vertical resolution ≥ 14 bits. |

| Superconducting Qubit Chip | The physical platform hosting the qubits for computation. | Transmon qubits with Tâ‚, Tâ‚‚ > 50 μs, anharmonicity ~200 MHz. |

| Electromagnetic Shielding | Protects qubits from external magnetic and radio-frequency interference. | Mu-metal magnetic shield and cryogenic RF shielding. |

| SABA1 | SABA1, MF:C22H19ClN2O5S, MW:458.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| TrkA-IN-7 | TrkA-IN-7, MF:C16H13N3O3, MW:295.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Data Presentation and Analysis

The efficacy of dynamical decoupling is quantitatively assessed by measuring the enhancement in coherence time and the corresponding improvement in algorithmic fidelity.

Table 4: Quantitative Performance of Decoherence Mitigation Strategies

| Mitigation Technique | Reported Coherence Gain | Resulting Energy Error Reduction | Experimental System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eulerian Decoupling [25] | 2 orders of magnitude increase in Tâ‚‚ | Not Specified | Solid-state spin (NV center) |

| RDM Post-Processing [21] | Not Applicable | Nearly an order of magnitude error reduction | Simulated Hâ‚‚, LiH, BeHâ‚‚ molecules |

| Decoherence-Free Subspaces (DFS) | Not Directly Comparable | >10x extension of quantum memory lifetime [22] | Trapped-ion system (H1 hardware) |

Decoherence remains a primary obstacle to achieving practical quantum advantage in computational chemistry. However, as detailed in these application notes, a combination of strategies—particularly dynamical decoupling protocols—provides a powerful and experimentally validated means to suppress decoherence and extend the coherent window for computation. When integrated with other error mitigation techniques like RDM post-processing [21] and advanced quantum error correction, these methods form a critical toolkit for researchers pushing the boundaries of what is possible in quantum chemistry on near-term hardware. The continued development and refinement of these protocols are essential for progressing from proof-of-concept calculations to reliable simulations of industrially relevant molecules and materials.

Implementing DD for Quantum Chemistry: From Theory to Practice on Real Hardware

Integrating DD Protocols into Quantum Algorithms for Chemistry

Quantum chemistry simulations on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices face significant challenges from decoherence and operational errors that limit their practical utility. Dynamical decoupling (DD) has emerged as a powerful, low-overhead technique for suppressing these errors during qubit idle periods, making it particularly valuable for quantum chemistry algorithms which often involve substantial computational latency. Originally developed for quantum memory protection, DD involves applying carefully timed sequences of control pulses to qubits to average out system-environment interactions [10]. The integration of DD protocols specifically tailored for quantum chemistry computations represents a critical advancement toward achieving chemically accurate results on current quantum hardware. This approach is especially valuable for complex simulations such as ligand-protein binding affinity predictions in drug development, where even small errors in energy calculations can lead to erroneous conclusions about relative binding affinities [26].

Fundamental Principles of Dynamical Decoupling

Theoretical Foundation

Dynamical decoupling operates on the principle of coherent averaging, where a system's interaction with its environment is suppressed through rapid, periodic control pulses. In the simplified framework of a noisy system, the evolution during an idle period is governed by a time-independent system-bath interaction Hamiltonian (H{SB}) and bath-specific Hamiltonian (HB). For time (\tau), the system evolution follows the unitary operator: (f{\tau} = \exp[-i\tau(H{SB} + HB)]) [10]. Consider the decoupling group (G \subseteq \mathrm{SU}(2)) where elements (gj \in G) represent physical actions on the system Hilbert space. The conjugation action of (G) on (f{\tau}) transforms the system-bath interaction: (gj^{\dagger}f{\tau}gj = \exp[-i\tau gj^{\dagger}(H{SB} + HB)gj] = \exp[-i\tau(H{SB}' + HB')]), where (H{SB}' = gj^{\dagger}H{SB}gj) [10]. For a general single-qubit system-bath coupling Hamiltonian expressed as (H{SB} = \sum{\alpha=x,y,z} \sigma^{\alpha} \otimes B^{\alpha}), this transformation enables selective cancellation of unwanted interaction terms through appropriate choice of (g_j) and pulse timing.

DD Sequence Design Considerations

The design of effective DD sequences must account for several hardware-aware factors: cancellation of specific terms in the system-bath interaction Hamiltonian, increasing the order in pulse spacing to which errors are suppressed, and reducing the effect of systematic errors in pulse implementation [10]. For multi-qubit quantum chemistry circuits, additional considerations include mitigating quantum crosstalk and accounting for control restrictions imposed by circuit structure. While numerous DD sequences have been theoretically developed, including Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG), universally robust DD (URDD), and Eulerian DD (EDD), their theoretical guarantees for canceling single-qubit errors do not extend to multi-qubit quantum crosstalk, which represents a central source of error in large chemistry circuits [10].

Protocol Integration Methodologies

Empirical Learning of DD Strategies

The genetic algorithm-inspired search to optimize DD (GADD) provides a framework for empirically tailoring DD strategies for specific quantum chemistry circuits and devices. This approach addresses the challenge that optimal pulse sequences vary significantly across different quantum processors and circuit configurations [10]. The GADD protocol proceeds through the following systematic steps:

Table 1: GADD Protocol Implementation Steps

| Step | Action | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Circuit Decomposition | Identify all idle periods in the target quantum chemistry circuit where DD can be applied |

| 2 | Sequence Initialization | Populate an initial candidate set of DD sequences, including canonical sequences (XY4, XY8, CPMG) and randomly generated patterns |

| 3 | Fitness Evaluation | Execute each candidate sequence on the target hardware with a simplified version of the chemistry circuit, using circuit fidelity as the fitness metric |

| 4 | Genetic Operations | Apply selection, crossover, and mutation to generate new candidate sequences based on fitness performance |

| 5 | Iterative Refinement | Repeat steps 3-4 for multiple generations until convergence to an optimal sequence |

| 6 | Validation | Test the optimized sequence on the full target chemistry circuit to verify performance improvement |

This empirical approach has demonstrated significant advantages, with learned DD strategies consistently outperforming canonical sequences across various experimental settings, with relative improvement increasing with problem size and circuit sophistication [10].

Staggered DD for Crosstalk Mitigation

For multi-qubit quantum chemistry circuits, staggered DD sequences provide enhanced crosstalk suppression compared to simultaneous application across all qubits. The staggered DD implementation protocol involves:

- Qubit Connectivity Analysis: Map the physical qubit connectivity and identify potential crosstalk channels based on the hardware topology

- Temporal Offset Calculation: Determine optimal timing offsets for DD pulse application across different qubits to minimize simultaneous switching noise

- Sequence Alignment: Ensure DD pulses are positioned to avoid overlapping with sensitive two-qubit gate operations in the chemistry algorithm

- Performance Validation: Verify error suppression using randomized benchmarking protocols specifically designed for multi-qubit circuits

This approach is particularly valuable for quantum chemistry applications involving large molecular systems, where crosstalk-induced errors can significantly impact the accuracy of energy calculations [10].

Integration with Mid-Circuit Measurements

Quantum chemistry algorithms increasingly incorporate mid-circuit measurements (MCMs) for dynamic circuit execution, which introduce additional error channels. The Quantum Instrument Randomized Benchmarking (QIRB) protocol provides a method to quantify and suppress MCM-induced errors [27]. The integration protocol involves:

Table 2: DD-MCM Integration Protocol

| Component | Implementation | Error Suppression Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Measurement DD | Apply optimized DD sequences immediately before MCM operations | Supports decoherence during measurement preparation |

| Post-Measurement DD | Implement DD after measurement and reset operations | Mitigates errors induced by classical feedforward |

| Crosstalk Suppression | Use staggered DD during parallel measurements | Reduces measurement-induced crosstalk on neighboring qubits |

| Dynamic Adaptation | Adjust DD sequences based on measurement outcomes | Enables adaptive error suppression in active reset cycles |

Experimental demonstrations on 27-qubit IBM Q processors have quantified how dynamical decoupling eliminates a significant portion of measurement-induced crosstalk error [27].

Application to Quantum Chemistry Workflows

Quantum Chemistry Algorithm Integration

The integration of DD protocols into quantum chemistry workflows requires careful consideration of algorithm-specific requirements. For density functional theory (DFT) simulations on quantum processors, DD sequences must be optimized to protect during the preparation and evolution phases that calculate electron repulsion integrals [28]. The implementation follows a structured approach:

- Circuit Analysis: Decompose the quantum chemistry algorithm into operational blocks (state preparation, unitary evolution, measurement) and identify idle periods within each block

- DD Sequence Selection: Choose appropriate DD sequences based on idle time duration and noise characteristics - shorter sequences for brief idling and higher-order sequences for extended idle periods

- Hardware-Specific Optimization: Use empirical learning approaches like GADD to tailor sequences for specific quantum processing units (QPUs) and their unique noise profiles

- Performance Verification: Validate energy calculation accuracy using benchmark molecular systems with known reference values

This approach has demonstrated particular value for quantum algorithms simulating ligand-pocket interactions, where accurate binding energy calculations require error suppression below the 1 kcal/mol threshold that significantly impacts drug design decisions [26].

Benchmarking and Validation Framework

Robust validation of DD-enhanced quantum chemistry computations requires specialized benchmarking protocols:

Molecular Benchmark Sets: Utilize established quantum chemistry datasets such as QUID (QUantum Interacting Dimer) framework containing 170 non-covalent systems modeling chemically and structurally diverse ligand-pocket motifs [26] or QM9 dataset featuring approximately 134,000 small organic molecules with optimized 3D geometries and DFT-calculated properties [29]

Error Metric Establishment: Define application-specific fidelity metrics including:

- Binding energy deviation from classical reference calculations

- Molecular property prediction errors (HOMO-LUMO gaps, dipole moments)

- Wavefunction fidelity for strongly correlated systems

Cross-Platform Validation: Verify DD protocol performance across different quantum hardware platforms (superconducting, trapped-ion) to ensure methodological robustness

The QUID framework establishes a "platinum standard" for ligand-pocket interaction energies through tight agreement between complementary coupled cluster and quantum Monte Carlo methods, achieving agreement of 0.5 kcal/mol, which provides a robust target for DD-enhanced quantum simulations [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Quantum Chemistry Research Toolkit

| Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GADD Framework | Empirical DD sequence optimization | Hardware-tailored error suppression for specific chemistry circuits |

| QUID Dataset | 170 non-covalent dimer structures | Benchmarking ligand-pocket interaction energy calculations [26] |

| QM9 Dataset | ~134K small organic molecules | Training and validation for property prediction models [29] |

| PubChemQCR | 3.5M molecular relaxation trajectories | ML interatomic potential training with energy/force labels [30] |

| QIRB Protocol | Mid-circuit measurement error characterization | Quantifying and suppressing MCM-induced errors in dynamic circuits [27] |

| Rys Quadrature | Electron repulsion integral computation | Efficient evaluation of two-electron integrals in DFT calculations [28] |

| G43 | N-(2-carbamoylphenyl)-5-nitro-1-benzothiophene-2-carboxamide | Explore the research applications of N-(2-carbamoylphenyl)-5-nitro-1-benzothiophene-2-carboxamide. This product is for Research Use Only and not for human or veterinary use. |

| BCR-ABL-IN-7 | BCR-ABL-IN-7, MF:C19H16FN3O3S, MW:385.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implementation Considerations for Drug Development

For researchers in pharmaceutical applications, specific implementation guidelines enhance the practical utility of DD protocols:

Binding Affinity Focus: Prioritize error suppression in circuit segments most critical for intermolecular interaction energy calculations, particularly those determining van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonding contributions

Conformational Sampling: Implement DD strategies that remain effective across multiple molecular conformations encountered during binding, including non-equilibrium geometries along dissociation pathways

Accuracy Thresholds: Target energy error budgets below 1 kcal/mol, as this threshold significantly impacts binding affinity predictions and compound prioritization decisions [26]

Dataset Utilization: Leverage specialized datasets like QUID that specifically model protein-ligand interaction motifs, including π-π stacking, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic interactions [26]

Performance Metrics and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Performance Assessment

Experimental implementations of empirically learned DD strategies demonstrate significant performance advantages across multiple metrics:

Table 4: DD Protocol Performance Comparison

| Protocol | Sequence | Error Reduction | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical DD | XY4, CPMG | Baseline | Single-qubit memory protection |

| Staggered DD | Variable timing | 2.1× vs. simultaneous | Multi-qubit crosstalk suppression [10] |

| GADD-Optimized | Empirically learned | 3.5× vs. canonical | Hardware- and circuit-specific optimization [10] |

| MCM-Enhanced DD | QIRB-validated | 68% crosstalk reduction | Circuits with mid-circuit measurements [27] |

The relative improvement of learned DD strategies increases with problem size and circuit sophistication, making them particularly valuable for complex quantum chemistry simulations involving dozens of qubits [10]. Experimental demonstrations include successful application to mirror randomized benchmarking on 100 qubits, GHZ state preparation on 50 qubits, and the Bernstein-Vazirani algorithm on 27 qubits [10].

Computational Overhead Considerations

While DD introduces additional pulses into quantum circuits, the overhead remains modest compared to the error suppression benefits:

- Pulse Count: Optimized sequences typically require 4-16 pulses per idle period, with exact counts determined by idle duration and noise spectrum

- Temporal Overhead: DD sequences occupy less than 15% of total circuit runtime in most chemistry applications

- Compilation Impact: Modern quantum compilers efficiently integrate DD sequences during circuit transpilation, minimizing additional complexity for algorithm developers

- Fidelity Gain: The fidelity improvements consistently outweigh overhead costs, particularly for deeper circuits representing complex molecular systems

Future Directions and Development Pathways

The integration of dynamical decoupling with quantum chemistry algorithms continues to evolve along several promising research directions:

Algorithm-Aware DD: Developing DD sequences specifically optimized for common subroutines in quantum chemistry simulations, such as basis transformation, time evolution, and phase estimation