Environmental Decoherence in Molecular Ground State Calculations: Challenges and Mitigation Strategies for Computational Chemistry

This article examines the critical impact of environmental decoherence on the accuracy and reliability of molecular ground state calculations, a fundamental challenge in computational chemistry and drug discovery.

Environmental Decoherence in Molecular Ground State Calculations: Challenges and Mitigation Strategies for Computational Chemistry

Abstract

This article examines the critical impact of environmental decoherence on the accuracy and reliability of molecular ground state calculations, a fundamental challenge in computational chemistry and drug discovery. We explore the foundational mechanisms by which interactions with environmental factors like lattice vibrations and nuclear spins disrupt quantum coherence. The review covers advanced methodological approaches, including dissipative engineering and hybrid atomistic-parametric models, for simulating and mitigating decoherence effects. Practical troubleshooting and optimization techniques are discussed, alongside validation frameworks for assessing calculation robustness. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis provides essential insights for performing computationally efficient and chemically accurate quantum calculations in the presence of environmental noise.

Understanding Environmental Decoherence: From Quantum Theory to Molecular Systems

Defining Quantum Decoherence and Its Significance in Chemical Calculations

Quantum decoherence describes the process by which a quantum system loses its quantum behavior, such as superposition and entanglement, due to interactions with its environment, causing it to behave more classically. This phenomenon is not just a philosophical curiosity but a fundamental physical process with profound implications for computational chemistry, quantum computing, and particularly for the accuracy of molecular ground state calculations in drug discovery research. As quantum systems, molecules and the qubits used to simulate them are exquisitely sensitive to their surroundings, and understanding decoherence is critical for advancing the frontier of computational chemistry [1] [2] [3].

Core Principles of Quantum Decoherence

Fundamental Concepts and Mechanisms

At its heart, quantum decoherence is the loss of quantum coherence. In quantum mechanics, a physical system is described by a quantum state, often visualized as a wavefunction. This state can exist in a superposition of multiple possibilities simultaneously, a property that enables the unique capabilities of quantum computers. However, when a system interacts with its environment—even in a minuscule way—these interactions cause the system to become entangled with the vast number of degrees of freedom in the environment. From the perspective of the system alone, this sharing of information leads to the rapid disappearance of quantum interference effects; the off-diagonal elements of the system's density matrix decay, and the system appears to collapse into a definite state [1] [2].

This process does not involve a true, physical collapse of the wavefunction. Instead, the global wavefunction of the system and environment remains coherent, but the coherence becomes delocalized and inaccessible to the system itself. This phenomenon, known as environmentally-induced superselection or einselection, explains why certain states (often position eigenstates for macroscopic objects) are "preferred" and appear stable, while superpositions of these states decohere almost instantaneously [1] [3].

Historical Context and Interpretative Frameworks

The concept of decoherence was first introduced in 1951 by David Bohm, who described it as the "destruction of interference in the process of measurement." The modern foundation of the field was laid by H. Dieter Zeh in 1970 and later invigorated by Wojciech Zurek in the 1980s [1]. Decoherence provides a framework for understanding the quantum-to-classical transition—how the familiar rules of classical mechanics emerge from quantum mechanics for systems that are not perfectly isolated [3]. It is crucial to note that decoherence is not an interpretation of quantum mechanics itself. Rather, it is a quantum dynamical process that can be studied within any interpretation (e.g., Copenhagen, Everettian, or Bohmian), and it directly addresses the practicalities of why quantum superpositions are not observed in everyday macroscopic objects [1] [3].

Quantitative Impact of Decoherence on Molecular Calculations

Decoherence Timescales in Molecular Systems

For molecular systems, particularly those being studied as potential quantum bits (qubits) or probed with ultrafast spectroscopy, decoherence occurs on remarkably fast timescales. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research, illustrating how decoherence parameters depend on system properties and environmental conditions.

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Decoherence Timescales and Parameters in Molecular Systems

| Molecular System | Environment | Decoherence Time | Key Influencing Factor | Source / Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thymine (DNA base) | Water | ~30 femtoseconds (fs) | Intramolecular vibrations (early-time), solvent (overall decay) | Resonance Raman Spectroscopy [4] |

| Copper porphyrin qubits | Crystalline lattice | Tâ‚ (relaxation) and Tâ‚‚ (dephasing) times | Magnetic field strength, lattice nuclear spins, temperature | Redfield Quantum Master Equations [5] |

| General S=1/2 molecular spin qubit | Solid-state matrix | T₠scales as 1/B or 1/B³; T₂ scales as 1/B² | Magnetic field (B), spin-lattice processes, magnetic noise [5] | Haken-Strobl Theory / Stochastic Hamiltonian [5] |

Impact on Calculated Molecular Properties

The effect of decoherence is not merely a technical nuisance; it directly limits the accuracy and feasibility of molecular simulations.

Table 2: Impact of Decoherence on Key Chemical Calculation Types

| Calculation Type | Target Output | Effect of Unmitigated Decoherence | Implication for Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ground State Energy Estimation | Total electronic energy | Inaccurate energy estimation; failure to converge to true ground state [6] | Misleading results for reaction feasibility and stability |

| Molecular Property Prediction | e.g., Dipole moments, excitation energies | Corruption of electronic properties derived from wavefunction | Reduced accuracy in predicting solubility, reactivity, and bioavailability |

| Molecular Dynamics (QM/MM) | Reaction pathways, binding affinities | Unphysical trajectory branching due to loss of quantum coherence [7] | Incorrect modeling of enzyme catalysis and drug-target binding |

Experimental and Theoretical Protocols for Probing Decoherence

Understanding and quantifying decoherence requires sophisticated experimental and theoretical protocols. The following workflow outlines a modern strategy for mapping decoherence pathways in molecules.

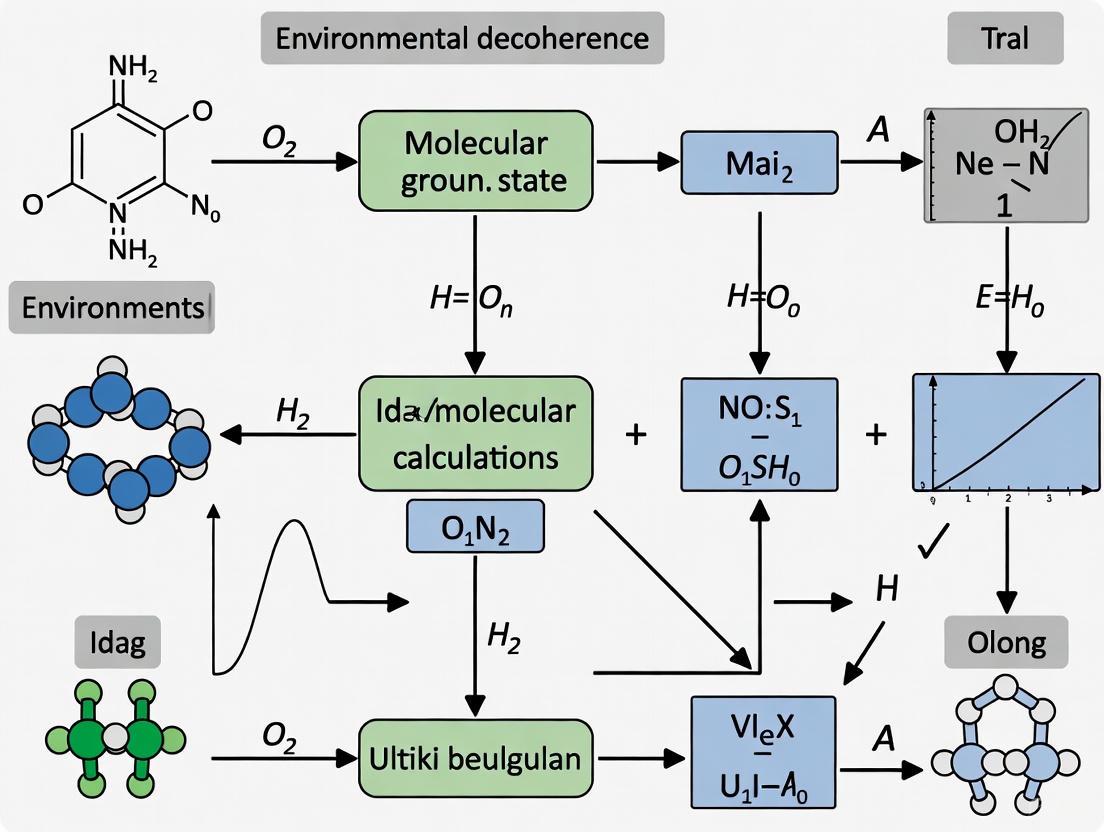

Diagram 1: Workflow for mapping molecular electronic decoherence pathways.

Protocol 1: Mapping Electronic Decoherence via Resonance Raman

This protocol, derived from recent research, allows for the quantitative dissection of electronic decoherence pathways with full chemical complexity [4].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a solution of the molecular chromophore of interest (e.g., the DNA base thymine) in a selected solvent (e.g., water) at room temperature.

- Resonance Raman Spectroscopy: Illuminate the sample with incident light of frequency ω_L, tuned to be in resonance with an electronic transition of the molecule. Collect the inelastically scattered Stokes and anti-Stokes signals. The key advantage of this method is its applicability to both fluorescent and non-fluorescent molecules in solvent at room temperature.

- Spectral Density Reconstruction: From the resonance Raman cross-sections, reconstruct the spectral density, J(ω). This function quantitatively characterizes the coupling between the electronic excitation and the frequencies (ω) of the nuclear environment (both intramolecular vibrations and solvent modes).

- Dynamics Calculation: Use the reconstructed J(ω) in a numerically exact quantum master equation (e.g., the Hierarchical Equations of Motion - HEOM) to compute the time evolution of the electronic coherence, σ_eg(t).

- Pathway Decomposition: Decompose the overall coherence loss by calculating the individual contributions from specific molecular vibrational modes and from the collective solvent modes. This identifies which chemical groups and interactions are the primary drivers of decoherence.

Protocol 2: Modeling Decoherence in Molecular Spin Qubits

For molecular spin qubits, a hybrid atomistic-parametric methodology can predict coherence times Tâ‚ and Tâ‚‚ [5].

- Hamiltonian Formulation: Model the spin qubit as an open quantum system with a stochastic Hamiltonian: Ĥ(t) = ĤS + ĤSB(t). Here, ĤS is the time-averaged system Hamiltonian (e.g., a Zeeman term), and ĤSB(t) contains the fluctuation terms.

- Atomistic Fluctuation Sampling: Use classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations at constant temperature to generate an ensemble of molecular configurations. For each configuration, sample the electronic effective spin Hamiltonian to obtain a time-series of the fluctuating gyromagnetic tensor, δg_ij(t). This avoids the need for costly numerical derivatives.

- Spectral Density Construction: Calculate the bath correlation functions from the atomistic fluctuations δgij(t) and any additional parametric noise models (e.g., for magnetic field noise δBi(t) from nuclear spins). From these, construct the total spectral density.

- Master Equation Solution: Input the spectral density into the Redfield quantum master equation to solve for the evolution of the system's density matrix, Ï_S. The relaxation time Tâ‚ and dephasing time Tâ‚‚ are directly extracted from this dynamics.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Decoherence Studies

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Decoherence Research |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrafast Laser Systems | Experimental Hardware | Generates femtosecond pulses to create and probe electronic coherences in spectroscopic protocols [4]. |

| Resonance Raman Spectrometer | Experimental Hardware | Measures inelastic scattering signals used to reconstruct the spectral density J(ω) of a molecule in its environment [4]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software | Computational Resource | Simulates classical lattice motion and generates trajectories for sampling Hamiltonian fluctuations in spin qubit models [5]. |

| Quantum Master Equation Solvers | Computational Resource | Software libraries for simulating open quantum system dynamics, such as HEOM or Redfield equation solvers [5] [4]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Codes | Computational Resource | Provides the electronic structure calculations needed to parameterize system Hamiltonians and understand coupling to vibrational modes [7]. |

Mitigation Strategies and Future Directions

The relentless effect of decoherence necessitates robust mitigation strategies, especially for quantum computing applications in chemistry.

- Dynamical Decoupling: Applying precise sequences of control pulses to the qubit system can "refocus" it and effectively reverse the effect of low-frequency environmental noise, thereby extending coherence times Tâ‚‚. This has been successfully demonstrated in molecular spin qubits [5] [2].

- Quantum Error Correction (QEC): QEC codes encode a single "logical" qubit into multiple physical qubits. By continuously detecting and correcting errors (like bit-flips or phase-flips caused by decoherence) without directly measuring the logical state, fault-tolerant quantum computation becomes possible despite noisy hardware [2].

- Decoherence-Free Subspaces (DFS): By encoding quantum information in specific combinations of physical qubits that are immune to certain types of collective noise, the information can be protected without active correction. Quantinuum has demonstrated a DFS code that extended quantum memory lifetimes by more than 10 times compared to single physical qubits [2].

- Chemical Design and Material Engineering: The ultimate strategy is to design molecules and materials with intrinsic resistance to decoherence. The experimental protocols outlined above are the first step toward establishing the chemical principles needed for this rational design, for instance, by engineering ligands to shield a spin qubit from fluctuating nuclear spins or by designing chromophores with specific vibrational spectra [5] [4].

Quantum decoherence is an inescapable physical phenomenon that directly challenges the accuracy and scalability of advanced chemical calculations, from ultrafast spectroscopy to molecular ground state estimation on quantum processors. It dictates hard limits on coherence times, as quantified by Tâ‚ and Tâ‚‚, and corrupts the quantum superpositions that underpin these technologies. However, through sophisticated theoretical models like Redfield master equations and innovative experimental techniques like resonance Raman spectroscopy, researchers are now mapping decoherence pathways at the molecular level. This growing understanding, combined with active mitigation strategies like error correction and dynamical decoupling, provides a clear roadmap for suppressing environmental noise. Mastering decoherence is not merely a technical hurdle but a fundamental prerequisite for unlocking the full potential of quantum-enhanced computational chemistry in the next generation of drug discovery and material science.

The pursuit of accurate molecular ground state calculations is fundamentally constrained by environmental decoherence—the process by which a quantum system loses its quantum coherence through interaction with its environment. For molecular quantum systems, whether serving as qubits in quantum computers or as subjects of computational chemistry simulations, three noise sources are particularly destructive: lattice phonons, nuclear spins, and thermal fluctuations [8] [9]. These interactions cause the fragile quantum information, encoded in properties like spin superposition and entanglement, to degrade into classical information, leading to computational errors and the collapse of quantum algorithms [8] [2].

Understanding and mitigating these sources is not merely an engineering challenge for building quantum hardware; it is a central problem in quantum chemistry and materials science. The accuracy of ab initio calculations for molecular ground states can be severely compromised if the simulations do not account for the decoherence pathways that would be present in a real, physical system [3] [9]. This guide provides a technical examination of these noise sources, offering both a theoretical framework and practical experimental insights relevant to researchers engaged in molecular quantum information science and drug development.

Theoretical Framework of Environmental Decoherence

Fundamental Concepts of Decoherence

Quantum decoherence describes the loss of quantum coherence from a system due to its entanglement with the surrounding environment [3] [1]. A system in a pure quantum state, described by a wavefunction, evolves unitarily when perfectly isolated. However, in reality, it couples to numerous environmental degrees of freedom—a heat bath of photons, phonons, and other particles [1]. This interaction entangles the system with the environment, causing the system's local quantum state to appear as a statistical mixture rather than a coherent superposition [3]. While the combined system-plus-environment evolves unitarily, the system in isolation does not, and its phase relationships are effectively lost to the environment [1].

This process is integral to the quantum-to-classical transition, explaining why macroscopic objects appear to obey classical mechanics while microscopic ones display quantum behavior [3]. For quantum computing and precise molecular calculations, decoherence is a formidable barrier, as it destroys the superposition and entanglement that provide the quantum advantage [8].

Impact on Molecular Ground State Calculations

Environmental decoherence directly impacts the feasibility and accuracy of calculating and utilizing molecular ground states. Key metrics affected include:

- Spin-lattice relaxation time (Tâ‚): The timescale for an excited spin to return to equilibrium with the lattice, emitting a phonon. This represents the energy relaxation of the system [9].

- Spin decoherence time (Tâ‚‚): The timescale for the loss of phase coherence between superposed states. This is always shorter than or equal to Tâ‚ and fundamentally limits the duration of coherent quantum operations [9].

Calculations that ignore these relaxation pathways risk producing results that represent an idealized, perfectly isolated molecule, not the molecule in its operational environment (e.g., in a solvent, a protein pocket, or a solid-state matrix). For drug development, where molecular interactions are simulated in silico, failing to account for the decoherence present in a biological environment can lead to inaccurate predictions of binding affinity and reaction pathways.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, primary effects, and key mitigation strategies for the three major environmental noise sources.

Table 1: Key Environmental Noise Sources and Their Impact on Molecular Qubits

| Noise Source | Physical Origin | Primary Effect on Qubit | Characteristic Decoherence Process | Exemplary Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lattice Phonons | Quantized crystal lattice vibrations [9] | Modulates crystal field, inducing spin-state transitions via spin-phonon coupling [9] | Spin-lattice relaxation (Tâ‚) [9] | Engineering rigid frameworks with high Debye temperatures [9] |

| Nuclear Spins | Magnetic dipole moments of atomic nuclei (e.g., ^1H, ^13C) in the lattice [10] | Creates a fluctuating local magnetic field at the electron spin site [10] | Spectral diffusion, dephasing (Tâ‚‚) [10] | Using nuclear spin-free isotopes; dynamic decoupling pulse sequences [10] |

| Thermal Fluctuations | Random thermal energy (kBT) within the environment [8] [2] | Excites phonon populations and causes random transitions in the environment [8] | Reduced Tâ‚ and Tâ‚‚ via increased phonon density and thermal noise [8] [9] | Cryogenic cooling to millikelvin temperatures [8] [2] |

Experimental Characterization and Methodologies

Key Experimental Protocols

Characterizing the impact of these noise sources requires sophisticated pulsed spectroscopy techniques.

Table 2: Core Experimental Protocols for Probing Decoherence

| Experiment Name | Pulse Sequence | Physical Quantity Measured | Key Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inversion Recovery | Ï€ – Ï„ – Ï€/2 – echo [9] | Spin-lattice relaxation time (Tâ‚) [9] | Directly probes the relaxation of energy to the lattice, dominated by spin-phonon coupling. |

| Hahn Echo Decay | π/2 – τ – π – τ – echo [9] | Phase memory time (Tₘ) [9] | Measures the loss of phase coherence (T₂), refocusing static inhomogeneous broadening to reveal spectral diffusion. |

| Nutation Experiment | Variable-length π/2 pulse – detection [9] | Rabi frequency and coherence during driven evolution | Confirms the successful control of the spin as a qubit and probes noise during quantum operations. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and their functions in studying and engineering molecular systems against decoherence.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Decoherence Studies

| Material / Reagent | Function in Research | Key Rationale | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents/Frameworks | Replaces ^1H (I=1/2) with ^2D (I=1) to reduce magnetic noise [9] | Weaker magnetic moment and different spin of deuterium reduce spectral diffusion from nuclear spins [9]. | Deuteration of hydrogen-bonded networks in MgHOTP frameworks reduced spin-lattice relaxation [9]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Provides a highly ordered, tunable solid-state matrix for qubits [9] | Well-defined phonon dispersion relations allow for systematic phonon engineering [9]. | TiHOTP MOF, lacking flexible motifs, showed a Tâ‚ 100x longer than MgHOTP at room temperature [9]. |

| Dilution Refrigerators | Cools quantum processors to ~10 mK [8] [2] | Suppresses population of thermal phonons and reduces thermal fluctuations, extending Tâ‚ and Tâ‚‚ [8]. | Essential for operating superconducting qubits and performing high-fidelity quantum operations [2]. |

| High-Purity Crystalline Substrates | Serves as a host material for spin qubits (e.g., in quantum dots) [10] | Minimizes material defects (e.g., vacancies, impurities) that cause charge and magnetic noise [10]. | Using isotopically purified ^28Si, which is spin-zero, drastically extends electron spin coherence times [10]. |

| SF1670 | SF1670, CAS:345630-40-2, MF:C19H17NO3, MW:307.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| SSR504734 | SSR504734, CAS:742693-38-5, MF:C20H20ClF3N2O, MW:396.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Data Visualization and Workflows

Environmental Decoherence Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and pathways through which the three primary environmental noise sources cause decoherence in a molecular qubit, ultimately leading to computational errors.

Experimental Workflow for Characterizing Decoherence

This diagram outlines a standard experimental workflow for characterizing spin coherence times in a molecular qubit framework, from sample preparation to data analysis.

Mitigation Strategies and Research Frontiers

Established Mitigation Techniques

Beyond the strategies mentioned in Table 1, the field employs several advanced techniques:

- Quantum Error Correction (QEC): QEC codes encode a single "logical" qubit into multiple entangled "physical" qubits, allowing for the detection and correction of errors without collapsing the logical state [8] [11]. Recent theoretical work shows that tailoring QEC codes to correct only the dominant error types in a sensor can make it more robust without the full overhead of perfect correction [11].

- Decoherence-Free Subspaces (DFS): Information is encoded in specific quantum states that are inherently immune to certain collective noise sources, for example, to a uniform magnetic field fluctuation that affects all qubits equally [8] [2]. Experiments on trapped-ion systems have demonstrated a decoherence-free subspace code that extended quantum memory lifetimes by more than a factor of ten compared to a single physical qubit [2].

Emerging Research and Future Outlook

The fight against decoherence is advancing on multiple fronts:

- Material Science and Phonon Engineering: Research on Molecular Qubit Frameworks (MQFs) demonstrates that structural design can profoundly impact coherence. For instance, replacing flexible, hydrogen-bonded motifs (as in MgHOTP) with rigid, interpenetrated frameworks (as in TiHOTP) can raise the phonon frequencies and increase Tâ‚ by one to two orders of magnitude [9].

- Noise-Tailored Entanglement Purification: A significant theoretical result from 2025 establishes that no universal, input-independent entanglement purification protocol can improve all noisy entangled states [12]. This underscores a paradigm shift toward developing bespoke error management strategies tailored to the specific noise profile of a given quantum system.

- Advanced Quantum Control: Techniques like dynamic decoupling, which uses sequences of precise pulses to "echo away" low-frequency noise from nuclear spins, continue to be refined and are crucial for extending coherence times in practical settings [10].

Lattice phonons, nuclear spins, and thermal fluctuations represent a triad of fundamental environmental noise sources that directly govern the fidelity and timescales of molecular ground state calculations and quantum coherence. The quantitative characterization of their effects through parameters like Tâ‚ and Tâ‚‚ provides a concrete roadmap for diagnosing and mitigating decoherence. As research progresses, the interplay between material engineering, advanced quantum control, and tailored error correction continues to push the boundaries, promising more robust molecular quantum systems for the future of computing, sensing, and drug development. The insights from molecular qubit frameworks offer a powerful paradigm for the rational design of quantum materials from the bottom up.

In quantum mechanics, the ideal of a perfectly isolated closed system is a theoretical construct; in reality, every quantum system interacts with its external environment, making it an open quantum system [13] [14]. This interaction leads to the exchange of energy and information, resulting in quantum decoherence and dissipation [1] [14]. For researchers focused on calculating molecular ground states—a critical task in drug discovery and materials science—this environmental coupling presents a significant challenge. It can alter the expected energy levels and properties of a molecule [15]. The very process that renders macroscopic objects classical (decoherence) directly impacts the accuracy of quantum simulations on both classical and quantum computers [16]. Furthermore, the interaction creates system-environment entanglement, a key factor in understanding the dynamics and stability of molecular states [17]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the frameworks of open quantum systems and the role of system-environment entanglement, with a specific focus on their implications for molecular ground state calculations in scientific research.

Theoretical Foundations of Open Quantum Systems

Core Definitions and Mathematical Descriptions

An open quantum system is defined as a quantum system (S) that is coupled to an external environment or bath (B) [13]. The combined system and environment form a larger, closed system, whose Hamiltonian is given by:

[ H = H{\rm{S}} + H{\rm{B}} + H_{\rm{SB}} ]

where (H{\rm{S}}) is the system Hamiltonian, (H{\rm{B}}) is the bath Hamiltonian, and (H{\rm{SB}}) describes the system-bath interaction [13]. The state of the principal system alone is described by its reduced density matrix, (\rhoS), obtained by taking the partial trace over the environmental degrees of freedom from the total density matrix: (\rhoS = \mathrm{tr}B \rho) [13].

The evolution of the reduced system is generally non-unitary. For a closed system, dynamics are governed by the Schrödinger equation, leading to unitary evolution. In contrast, the open system's dynamics involve a quantum channel or a dynamical map, which accounts for the environmental influence [16].

Key Theoretical Models

Different models are employed to describe the system-environment interaction, each with its own approximations and domain of applicability.

Table 1: Key Theoretical Models for Open Quantum Systems

| Model | Description | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Lindblad Master Equation [13] [14] | A Markovian (memoryless) master equation that guarantees complete positivity of the density matrix. Its general form is (\dot{\rho}S = -\frac{i}{\hbar} [HS, \rhoS] + \mathcal{L}D(\rhoS)), where (\mathcal{L}D) is the dissipator. | Quantum optics, quantum information processing, and modeling decoherence in qubits. |

| Caldeira-Leggett Model [13] | A specific model where the environment is represented as a collection of harmonic oscillators. | Quantum dissipation and decoherence in condensed matter physics. |

| Spin Bath Model [13] | A model where the environment is composed of other spins. | Solid-state systems, such as nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamonds interacting with ¹³C nuclear spins. |

| Non-Markovian Models [13] | Models that account for memory effects, where past states of the system influence its future evolution. Described by integro-differential equations like the Nakajima-Zwanzig equation. | Systems with strong coupling to structured environments, and in quantum biology. |

Quantum Decoherence and Einselection

Quantum decoherence is the process by which a quantum system loses its phase coherence due to interactions with the environment [1]. It is the primary mechanism through which quantum superpositions are transformed into classical statistical mixtures. While the global state of the system and environment remains a pure superposition, the local state of the system alone appears mixed—this explains the apparent "collapse" without invoking a fundamental wavefunction collapse [1].

A crucial consequence of decoherence is einselection (environment-induced superselection) [1]. Through the continuous interaction with the environment, certain system states—known as pointer states—are found to be robust and do not entangle strongly with the environment. These states are "selected" to survive, while superpositions of them are rapidly destroyed. This process explains the emergence of a preferred basis in the classical world, answering why we observe definite states in macroscopic objects [16].

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental structure of an open quantum system and the decoherence process.

System-Environment Entanglement and Its Characterization

Entanglement as a Core Feature of Openness

When a quantum system interacts with its environment, they typically become quantum entangled [1]. This means the combined state of S and B cannot be written as a simple product state, (\rho{SB} \neq \rhoS \otimes \rho_B). This entanglement is the vehicle through which information about the system leaks into the environment, leading to decoherence [16]. System-Environment Entanglement (SEE) is thus not merely a byproduct but a fundamental characteristic of an open quantum system's evolution.

Quantifying Entanglement and its Scaling

Recent research has focused on quantifying SEE to understand its behavior, especially in complex many-body systems. A key finding is that SEE can exhibit specific scaling laws near quantum critical points. For instance, in critical spin chains under decoherence, the SEE's system-size-independent term (known as the g-function) shows a drastic change in behavior near a phase transition induced by decoherence [17]. This makes SEE an efficient quantity for classifying mixed states subject to decoherence.

A notable result is that for the XXZ model in its gapless phase, the SEE under nearest-neighbor ZZ-decoherence is twice the value of the SEE under single-site Z-decoherence. This quantitative relationship, discovered through numerical studies and connections to conformal field theory, provides a sharp tool for diagnosing phase transitions in open systems [17].

Impact on Molecular Ground State Calculations

The Fundamental Challenge of Decoherence

The primary goal of many quantum chemistry calculations is to find the ground state energy of a molecule, which is the lowest eigenvalue of its molecular Hamiltonian [18] [19]. For a closed system, this is found by solving the time-independent Schrödinger equation, (\hat{H}|\psi\rangle = E|\psi\rangle) [15]. However, in a real-world scenario, the molecule is an open system coupled to a thermal environment.

This environmental coupling poses a two-fold problem:

- Energetic Distortion: The interaction Hamiltonian (H_{SB}) can directly perturb the effective energy levels of the molecule.

- State Degradation: Decoherence destroys the delicate quantum superpositions and entanglement that are essential for representing the true, correlated ground state of the molecule. This can lead to calculations converging to incorrect, classical-like statistical mixtures instead of the genuine quantum ground state [15] [16].

Practical Implications for Computational Methods

Table 2: Impact of Decoherence on Different Computational Platforms

| Computational Platform | Impact of Decoherence |

|---|---|

| Classical Simulations | The environment's vast number of degrees of freedom makes exact simulation intractable. Approximations are required, which can miss important non-Markovian or strong-coupling effects, leading to inaccurate predictions of molecular properties and reaction rates [15]. |

| Noisy Quantum Processors | Qubits used to simulate the molecule are themselves open quantum systems. Environmental noise causes errors in gate operations and the decay of the quantum state, limiting the depth and accuracy of algorithms like VQE [18] [19]. This directly affects the fidelity of the computed ground state energy. |

Experimental Protocols and Computational Methodologies

Protocol 1: Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) on a Noisy Device

The VQE is a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed to run on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices to find molecular ground states [19].

Detailed Protocol:

- Problem Formulation: Map the molecular Hamiltonian of interest (e.g., Hâ‚‚) onto a qubit Hamiltonian expressed as a sum of Pauli operators [19].

- Ansatz Preparation: Prepare a parameterized trial wavefunction (ansatz) on the quantum processor. A common "hardware-efficient" ansatz uses alternating layers of single-qubit RY rotations and two-qubit CNOT gates for entanglement [19].

- State Measurement: Measure the expectation value of the qubit Hamiltonian for the current trial state. This requires repeated measurements ("shots") to gather sufficient statistics.

- Classical Optimization: A classical optimizer (e.g., the NFT optimizer) uses the measured energy as a cost function. The optimizer proposes new parameters for the ansatz to lower the energy.

- Iteration: Steps 2-4 are repeated until the energy converges to a minimum. The final energy is the VQE estimate of the ground state energy.

The entire VQE workflow, highlighting the hybrid quantum-classical loop, is shown below.

Protocol 2: Quantum Selected Configuration Interaction (QSCI)

The QSCI method is designed to be more robust to noise and imperfect state preparation on quantum devices [18].

Detailed Protocol:

- Input State Preparation: A quantum computer is used to prepare an input state (|\psi_{\text{in}}\rangle). This state does not need to be the exact ground state; it can be a reasonably good approximation, such as a VQE-optimized state with a limited number of iterations [18].

- Computational Basis Measurement: The input state is measured repeatedly in the computational basis, yielding a set of bitstrings.

- State Selection: The most frequently measured bitstrings are selected as important electronic configurations for the molecule.

- Classical Diagonalization: A subspace Hamiltonian is constructed using the selected configurations. This smaller Hamiltonian is then diagonalized exactly on a classical computer to obtain the ground state energy. This energy is guaranteed to be a variational upper bound to the true ground state energy, even when using noisy quantum hardware [18].

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit for Open System Molecular Calculations

| Tool / "Reagent" | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Molecular Hamiltonian | The fundamental starting point, defining the system of interest and its internal interactions [15]. |

| Environmental Model (e.g., Harmonic Bath) | A simplified representation of the environment, crucial for theoretical analysis and simulation of open system effects [13]. |

| Lindblad Master Equation Solver | Software that simulates the Markovian dynamics of an open quantum system, used to model decoherence and relaxation. |

| Qiskit / IBM Q Experience | An open-source quantum computing SDK and platform that provides access to real quantum devices and simulators for running algorithms like VQE and QSCI [18] [16]. |

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz | A parameterized quantum circuit designed for a specific quantum processor, used in VQE to prepare trial states despite device limitations [19]. |

Case Studies in Molecular Ground State Calculation

Case Study 1: Hydrogen Molecule (Hâ‚‚) via VQE

In a proof-of-principle experiment, AQT simulated the potential energy landscape of a hydrogen molecule using VQE on a trapped-ion quantum processor [19].

- Methodology: The Hâ‚‚ Hamiltonian was mapped to a 2-qubit model. A hardware-efficient ansatz (RY and CNOT gates) was used. The algorithm was run for multiple interatomic distances to construct the dissociation curve.

- Results: The computed ground state energies for various bond lengths are shown in Table 4. The VQE results successfully reproduced the characteristic curve, with the energy minimum found at the correct bond length of ~0.753 Ã…. The algorithm demonstrated good reproducibility over multiple runs, with deviations on the order of ~0.01 Hartree.

- Open Systems Context: The results were affected by the inherent noise of the NISQ device, a practical manifestation of the quantum processor being an open system. This highlights the need for error mitigation and robust algorithms.

Table 4: Sample VQE Results for Hâ‚‚ Ground State Energy vs. Bond Length [19]

| Bond Length (Ã…) | VQE Energy (Hartree) | Classical Exact Energy (Hartree) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.50 | ~ -0.70 | -0.734 |

| 0.75 | ~ -1.14 | -1.137 |

| 1.00 | ~ -1.05 | -1.055 |

| 1.50 | ~ -0.85 | -0.848 |

Case Study 2: Diazene and Methane via QSCI

This joint research by QunaSys and ENEOS applied the QSCI method to larger molecules on an IBM quantum processor ("ibm_algiers") [18].

- Methodology:

- For diazene (Nâ‚‚Hâ‚‚), an 8-qubit system was used. The input state for QSCI was generated by a VQE simulation using a customized ansatz that entangled occupied and virtual orbitals.

- For methane (CHâ‚„), a 16-qubit system was studied to model its dissociation reaction.

- Results:

- Diazene: QSCI executed on the real device achieved an energy of -108.6176 Ha, which matched the exact classical result (CASCI) and was more accurate than the VQE input state (-108.6163 Ha) [18].

- Methane: The real-device QSCI results for the dissociation curve showed good accuracy compared to noiseless simulator VQE, particularly in the intermediate bond-length region where electron correlation is significant.

- Open Systems Context: This study explicitly demonstrated that QSCI can overcome certain open system challenges. It proved robust against noise and produced accurate energies even from imperfectly optimized input states, effectively mitigating some decoherence effects present in the NISQ device.

The framework of open quantum systems is not an abstract theory but a fundamental consideration for accurately calculating molecular ground states. Environmental decoherence and the resulting system-environment entanglement directly influence the stability, energy, and very definition of the state we seek to find. While challenging, the field is advancing rapidly. The development of noise-resilient algorithms like QSCI and the increasing fidelity of quantum hardware are providing new paths to overcome these hurdles. A deep understanding of these theoretical frameworks empowers researchers to better interpret their results, choose appropriate computational methods, and push the boundaries of accuracy in quantum chemistry, with profound implications for rational drug design and material science.

How Decoherence Disrupts Molecular Ground State Properties and Energy Calculations

Quantum computing holds immense potential for revolutionizing molecular simulation, promising to solve the Schrödinger equation for complex systems that are intractable for classical computers. A fundamental task in this field is the accurate calculation of molecular ground state energies—the lowest energy level a molecule can occupy—which determines stability, reactivity, and electronic structure. These calculations are crucial for drug discovery, materials design, and chemical engineering [20]. However, the very quantum effects that enable these advanced computations—superposition and entanglement—are exceptionally fragile. Quantum decoherence, the process by which a quantum system loses its coherence through interaction with its environment, represents the most significant barrier to realizing this potential [2] [21].

This technical guide examines how environmental decoherence disrupts molecular ground state calculations. We explore the underlying physical mechanisms, quantify its impacts on computational algorithms, and synthesize recent experimental advances in mitigating decoherence through quantum error correction. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these dynamics is not merely academic; it is essential for navigating the limitations and capabilities of current and near-term quantum simulation platforms.

Theoretical Foundations of Decoherence

The Physical Mechanism of Environmental Decoherence

In quantum mechanics, a system is described by a wave function that can exist in a superposition of multiple states. For a molecule, this could theoretically include a superposition of different structural configurations or electronic distributions. This quantum coherence enables the interference effects that are fundamental to quantum algorithms [1] [21].

Environmental decoherence occurs when a quantum system interacts with its surrounding environment—whether through stray photons, air molecules, vibrational phonons, or electromagnetic fluctuations. This interaction entangles the system with the environment, causing phase information to leak into the environmental degrees of freedom. From the perspective of an observer focused only on the system, this appears as a loss of coherence, transforming a pure quantum state into a statistical mixture [3] [21]. The different components of the system's wave function lose their phase relationship, and without this phase relationship, quantum interference becomes impossible [1]. This process is not the same as the wave function collapse posited by the Copenhagen interpretation; it happens continuously and naturally, even without a conscious observer [21].

The Mathematical Description: Density Matrices and Einselection

The evolution from a pure state to a mixed state is elegantly captured using the density matrix formalism. For a system in a pure state superposition, the density matrix contains significant off-diagonal elements representing quantum coherence. Through entanglement with the environment, these off-diagonal elements decay exponentially over time—a process known as dephasing [3] [21].

A crucial consequence of decoherence is einselection (environment-induced superselection), where the environment continuously "monitors" the system, selecting a preferred set of quantum states that are robust against further environmental disruption. These pointer states correspond to the classical states we observe [1] [3]. In molecular systems, interactions are often governed by position-dependent potentials, making spatial localization a common einselection outcome [3]. The timescales for this process can be astonishingly short—for a speck of dust in air, suppression of interference on the scale of 10â»Â¹Â² cm occurs within nanoseconds [3].

Impact of Decoherence on Ground State Energy Calculations

Algorithmic Vulnerability and the Coherence Time Barrier

Calculating molecular ground state energies typically employs algorithms like Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE), which relies on coherent evolution and quantum interference to extract energy eigenvalues from phase information [20]. These algorithms require maintaining quantum coherence throughout their execution, but decoherence imposes a strict coherence time barrier—the limited duration for which qubits maintain their quantum states [2] [21].

When decoherence occurs mid-calculation, it introduces errors that manifest as energy inaccuracies or complete algorithmic failure. The table below summarizes how decoherence specifically disrupts the requirements of ground state energy algorithms:

Table 1: Impact of Decoherence on Algorithmic Requirements for Ground State Energy Calculation

| Algorithmic Requirement | Effect of Decoherence | Consequence for Energy Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| Maintained Phase Coherence | Dephasing destroys phase relationships between superposition components [2] | Incorrect phase estimation, leading to wrong energy eigenvalues [20] |

| Preserved Entanglement | Entanglement between qubits degrades into classical correlations [2] | Breakdown of multi-qubit operations needed for molecular Hamiltonian simulation |

| Quantum Interference | Suppression of interference patterns essential for probability amplitude manipulation [3] | Failure of amplitude amplification toward ground state |

| Unitary Evolution | Introduction of non-unitary, irreversible dynamics through environmental coupling [1] | Evolution toward mixed states rather than pure ground state |

Manifestation in Computational Chemistry Metrics

The disruption caused by decoherence becomes quantitatively evident in key computational chemistry metrics. In a landmark 2025 experiment, Quantinuum researchers performed a complete quantum chemistry simulation using quantum error correction on their H2-2 trapped-ion quantum computer to calculate the ground-state energy of molecular hydrogen [20].

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Decoherence on Molecular Ground State Calculation (Molecular Hydrogen Example)

| Calculation Aspect | Target Performance | Observed Performance with Decoherence Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Ground State Energy Accuracy | Chemical Accuracy (0.0016 hartree) [20] | Error of 0.018 hartree (above chemical accuracy threshold) [20] |

| Algorithm Depth | Deep circuits for precise energy convergence | Limited to shallow circuits by accumulated decoherence [2] |

| Qubit Count Scalability | Linear scaling with molecular complexity | Exponential challenges in coherence maintenance with added qubits [2] |

| Computational Result | Deterministic, reproducible output | Noisy, probabilistic outcomes requiring statistical analysis [20] |

As evidenced by the Quantinuum experiment, despite using 22 qubits and over 2,000 two-qubit gates with quantum error correction, the result remained above the "chemical accuracy" threshold of 0.0016 hartree—the precision required for predictive chemical simulations [20]. This deviation illustrates how decoherence, even when partially mitigated, introduces errors that limit the practical utility of quantum computations for precise molecular energy determinations.

Experimental Approaches and Mitigation Strategies

Quantum Error Correction in Chemistry Simulations

The Quantinuum experiment demonstrated the first complete quantum chemistry simulation using quantum error correction (QEC), implementing a seven-qubit color code to protect each logical qubit [20]. Mid-circuit error correction routines were inserted between quantum operations to detect and correct errors as they occurred. Crucially, this approach showed improved performance despite increased circuit complexity, challenging the assumption that error correction invariably adds more noise than it removes [20].

The experimental workflow for implementing error-corrected quantum chemistry simulations involves several sophisticated stages:

Diagram 1: QEC in Quantum Chemistry Workflow

This workflow demonstrates how error correction is integrated directly into the computational process, enabling real-time detection and mitigation of decoherence effects during the quantum phase estimation algorithm.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials and Methods

Implementing decoherence-resistant quantum chemistry calculations requires specialized hardware, software, and methodological components. The table below catalogs key "research reagent solutions" employed in advanced experiments:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Decoherence-Managed Quantum Chemistry Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Implementation | Function in Mitigating Decoherence |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware Platforms | Trapped-ion quantum computers (e.g., Quantinuum H2) [20] | Native long coherence times, all-to-all connectivity, high-fidelity gates [20] |

| Error Correction Codes | Seven-qubit color code [20] | Encodes single logical qubit into multiple physical qubits to detect/correct errors without collapsing state [20] |

| Error Suppression Techniques | Dynamical decoupling [20] | Uses fast pulse sequences to cancel out environmental noise [21] |

| Algorithmic Compilation | Partially fault-tolerant gates [20] | Reduces circuit complexity and error correction overhead while maintaining protection against common errors [20] |

| Decoherence-Free Subspaces | Encoded logical qubits in DFS [2] | Encodes quantum information in specific state combinations immune to collective noise [2] |

The Path Forward: Emerging Strategies

Beyond current quantum error correction approaches, several promising strategies are emerging to address the decoherence challenge in molecular calculations:

- Bias-Tailored Codes: Focusing error correction resources on the most common types of errors in specific hardware platforms [20]

- Higher-Distance Correction Codes: Correcting more than one error per logical qubit as hardware improves [20]

- Logical-Level Compilation: Developing compilers that optimize circuits specifically for error correction schemes rather than physical gate-level translation [20]

- Material Science Innovations: Using techniques like molecular-beam epitaxy to create purer quantum materials with dramatically enhanced coherence times, as demonstrated in recent research achieving 24-millisecond coherence times—a 240x improvement [22]

Decoherence presents a fundamental challenge to accurate molecular ground state calculations by disrupting the quantum coherence that algorithms like Quantum Phase Estimation depend on. Through environmental interactions that entangle quantum systems with their surroundings, decoherence transforms pure quantum states into mixed states, suppressing interference effects and introducing errors in computed energies [1] [3] [21]. Recent experiments demonstrate that while quantum error correction can partially mitigate these effects, current implementations still fall short of the chemical accuracy threshold required for predictive molecular design [20].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these limitations define the current boundary between theoretical potential and practical application in quantum computational chemistry. The strategic integration of error correction, improved materials science, and algorithmic innovation represents the most promising path toward overcoming the decoherence barrier. As coherence times extend and error correction becomes more efficient, the quantum-classical divide in molecular simulation will progressively narrow, potentially unlocking new frontiers in molecular design and materials discovery.

Understanding and controlling quantum decoherence—the loss of quantum coherence due to interaction with the environment—is a fundamental challenge in quantum information science and molecular electronics. For molecular systems, which are promising platforms for quantum technologies due to their chemical tunability, quantifying decoherence timescales is essential for assessing their viability as qubits or components in quantum devices. This guide synthesizes recent experimental evidence on decoherence times in molecular spin qubits and molecular junctions, framing the discussion within the broader context of how environmental decoherence affects molecular ground state calculations and quantum coherence. The interplay between a quantum system and its environment can lead to deformation of the ground state, even at zero temperature, through virtual excitations, thereby influencing the fidelity of quantum computations and measurements [23].

Experimental studies across different molecular systems reveal decoherence timescales that vary over several orders of magnitude, influenced by factors such as temperature, magnetic field, and the specific environmental coupling mechanisms. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research.

Table 1: Experimental Decoherence Timescales in Molecular Systems

| System Type | Specific System | Coherence Time (Tâ‚‚) | Relaxation Time (Tâ‚) | Experimental Conditions | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Spin Qubit | Copper Porphyrin Crystal | Not Explicitly Shown | Scales as (1/B) (combined noise) | Variable Magnetic Field | Magnetic field noise (~10 μT - 1 mT), spin-lattice coupling [5] |

| Molecular Junction | MCB Junction in THF | 1-20 ms | Not Measured | Ambient Conditions, THF Partially Wet Phase | Measurement duration (Ï„_m), enclosed environment [24] [25] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Molecular Spin Qubits: A Hybrid Atomistic-Parametric Approach

The characterization of decoherence in molecular spin qubits, such as copper porphyrin, relies on a sophisticated hybrid methodology that combines atomistic simulations with parametric modeling of noise [5].

- Open Quantum System Model: The system is modeled using a Haken-Strobl-type approach, where the total Hamiltonian is ( \hat{H}(t) = \hat{H}S + \hat{H}{SB}(t) ). The static system Hamiltonian ( \hat{H}S ) describes the qubit in an external magnetic field, including the Zeeman effect and hyperfine interactions. The system-bath interaction Hamiltonian ( \hat{H}{SB}(t) ) incorporates two key fluctuation sources: time-dependent fluctuations of the molecular ( g )-tensor (( \delta g{ij}(t) )) due to lattice phonons, and stochastic fluctuations of the local magnetic field (( \delta B{i}(t) )) due to nuclear spins in the lattice [5].

- Atomistic Spectral Density Calculation: The ( g )-tensor fluctuations are obtained from first principles. This involves running classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the crystalline lattice at a constant temperature. For each snapshot of the MD trajectory, the electronic effective spin Hamiltonian of the qubit is sampled to compute the instantaneous ( g )-tensor. This process generates a time series of ( \delta g_{ij}(t) ) without requiring numerical derivatives of the Hamiltonian, preserving its symmetries [5].

- Dynamics and Timescale Extraction: The fluctuations are used to construct bath correlation functions and the corresponding spectral density ( J(\omega) ). A Redfield quantum master equation for the system's density matrix is then formulated. Solving this equation allows for the extraction of the relaxation time ( T1 ) and the coherence time ( T2 ) [5].

- Incorporation of Parametric Noise: Purely atomistic predictions of ( T_1 ) often overestimate experimental values. Quantitative agreement is achieved by introducing a parametric magnetic field noise model with a field-dependent noise amplitude to account for the effect of lattice nuclear spins, which are not fully captured in the MD simulations [5].

Molecular Junctions: Controlling Decoherence via Measurement

Experiments on mechanically controlled break-junctions (MCBs) offer a direct way to probe and control decoherence in a distinct "enclosed open quantum system" [24] [25].

- Sample Preparation: A gold wire is broken within a tetrahydrofuran (THF) environment at ambient conditions. A controlled drying process leads to the formation of a single-molecule junction self-assembled within a THF "partially wet phase." This phase acts as a controlled Faraday cage, isolating the junction from the larger, uncontrolled environment [25].

- Current-Voltage (I-V) Characterization: The junction is voltage-biased, and I-V curves are recorded. Each curve consists of 1000 data points, with scans taken for both increasing and decreasing voltage [25].

- Critical Parameter: Measurement Integration Time (

τ_m): The integration time for each current measurement is a key controllable parameter. The current is calculated as the total charge flowing through the junction during the timeτ_mdivided byτ_m. Studies toggledτ_mbetween "fast" (640 µs) and "slow" (20 ms) settings [25]. - Probing the Quantum-Classical Transition: At fast measurement times (

τ_m= 640 µs) comparable to the system's intrinsic decoherence time, the I-V data exhibits structured bands and quantum interference patterns. When the measurement time is significantly longer (τ_m= 20 ms), these interference patterns vanish, and the I-V characteristics collapse to a single, classical-averaged response. This demonstrates that the measurement duration itself can be used to control the observed decoherence dynamics [24] [25].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core logical relationships and experimental workflows for characterizing decoherence in the two primary molecular systems discussed.

Decoherence Mechanisms in Molecular Spin Qubits

The diagram below outlines the primary mechanisms and theoretical modeling pathway for decoherence in molecular spin qubits.

Probing Decoherence in Molecular Junctions

This workflow details the experimental procedure for investigating measurement-dependent decoherence in molecular junctions.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental investigation of decoherence relies on specialized materials and computational tools. The following table lists key "research reagents" and their functions in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Decoherence Studies

| Item | Function / Relevance in Decoherence Studies |

|---|---|

| Open-Shell Molecular Complexes (e.g., Copper Porphyrin) | Serve as the core spin qubit (S=1/2) with addressable and tunable quantum states for coherence time measurements [5]. |

| Crystalline Framework Matrices | Provide a solid-state environment for spin qubits, enabling the study of decoherence from lattice phonons via molecular dynamics simulations [5]. |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) Partial Wet Phase | Acts as a controlled solvent environment and Faraday cage in molecular junction experiments, enabling unusually long coherence times at ambient conditions [24] [25]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software | Used to generate classical lattice motion at constant temperature, providing the trajectory data for atomistic calculation of g-tensor fluctuations [5]. |

| Paramagnetic Nuclear Spin Sources (e.g., lattice atoms with nuclear spins) | Constitute a major source of magnetic noise (δB), leading to dephasing and a characteristic (1/B^2) scaling of (T_2) in spin qubits [5]. |

| Mechanically Controlled Break-Junction (MCB) Apparatus | Allows for the formation and precise electrical characterization of single-molecule junctions to probe quantum interference and its decay [25]. |

Computational Approaches for Modeling Decoherence in Molecular Systems

1. Introduction

The accurate calculation of molecular ground state properties is a cornerstone of computational chemistry and drug design. Traditional methods, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT), often operate under the assumption of an isolated molecule in a vacuum. However, the broader thesis of this work posits that environmental decoherence—the loss of quantum coherence due to interaction with a surrounding environment—fundamentally alters these calculations. To bridge the gap between isolated quantum systems and realistic, solvated biomolecules, we present a technical guide for developing Hybrid Atomistic-Parametric Models. This approach synergistically combines the atomistic detail of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations with the rigorous treatment of open quantum systems provided by Quantum Master Equations (QMEs).

2. Theoretical Framework

The core of the hybrid methodology lies in partitioning the system. The "system" (e.g., a chromophore or reactive site) is treated quantum-mechanically, while the "bath" (e.g., solvent, protein scaffold) is treated classically by MD. The interaction between them is parameterized from the MD trajectory and fed into a QME that describes the system's dissipative evolution.

The QME, often in the Lindblad form, governs the time evolution of the system's density matrix, Ï:

dÏ/dt = -i/â„ [H, Ï] + D(Ï)

Where:

-i/â„ [H, Ï]is the unitary evolution under the system HamiltonianH.D(Ï)is the dissipator superoperator, encapsulating environmental decoherence and energy relaxation.

3. Core Workflow and Protocol

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for constructing and applying a hybrid model.

Workflow for Hybrid Model Construction

Step 1: System Preparation

- Quantum System Selection: Identify the molecular subsystem of interest (e.g., a drug molecule's binding moiety).

- Force Field Parameterization: Parameterize the entire system (quantum system + environment) using a classical force field (e.g., GAFF, CHARMM). The quantum system requires special parameters compatible with QM/MM methods.

- Solvation and Equilibration: Place the system in a solvation box, neutralize it with ions, and run a standard energy minimization and equilibration protocol.

Step 2: Molecular Dynamics Simulation

- Protocol: Run a production MD simulation (e.g., 100-500 ns) using software like GROMACS or NAMD. Employ a Thermostat (e.g., Nose-Hoover) and Barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) to maintain constant temperature and pressure (NPT ensemble). Save trajectory frames at a frequency high enough to capture relevant bath dynamics (e.g., every 10-100 fs).

Step 3: QM/MM Energy Calculation

- Protocol: For a subset of MD snapshots, perform QM/MM single-point energy calculations. The quantum system is computed with a method like TD-DFT, while the environment is treated with the MM force field.

- Output: A time-series of the energy gap,

ΔE(t), between the ground and excited states of the quantum system, influenced by the fluctuating environment.

Step 4: Spectral Density and Parameter Extraction

The key link between MD and the QME is the spectral density, J(ω), which characterizes the bath's ability to accept energy at a frequency ω. It is calculated from the energy gap autocorrelation function, C(t) = ⟨δΔE(t) δΔE(0)⟩:

J(ω) = (1/Ï€) ∫₀∞ dt C(t) cos(ωt) / Ⅎ

From J(ω), decoherence rates (γ) and reorganization energies (λ) are derived for use in the QME.

Table 1: Extracted Parameters from MD for a Model Chromophore in Water

| Parameter | Symbol | Value (from example MD) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reorganization Energy | λ | 550 cmâ»Â¹ | Energy stabilization due to bath rearrangement. |

| Decoherence Rate | γ | 150 fsâ»Â¹ | Rate of pure phase loss (dephasing). |

| Bath Cutoff Frequency | ω_c | 175 cmâ»Â¹ | Characteristic frequency of the bath modes. |

Step 5: Quantum Master Equation Propagation

- Protocol: Initialize the quantum system in a specific state (e.g., excited state). Propagate the QME (e.g., Lindblad, Redfield) using the parameters (

γ,λ) obtained in Step 4. This is typically done with specialized quantum dynamics packages (e.g., QuTiP). - Observable: The time-dependent population of the ground state,

P_g(t) = ⟨g|Ï(t)|g⟩.

Step 6: Analysis and Validation Compare the ground state recovery dynamics from the hybrid model with:

- Experimental data (e.g., ultrafast spectroscopy).

- Results from a fully isolated quantum system calculation.

4. The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Item | Function in Hybrid Modeling |

|---|---|

| GROMACS | Open-source MD software for generating the atomistic trajectory of the solvated system. |

| CHARMM/AMBER Force Fields | Provide parameters for the classical MD simulation of the biomolecular environment. |

| Gaussian / ORCA | Quantum chemistry software for computing accurate QM/MM energies on MD snapshots. |

| Python (NumPy, SciPy) | For scripting the analysis pipeline, calculating C(t) and J(ω), and fitting parameters. |

| QuTiP (Quantum Toolbox in Python) | A specialized library for simulating the dynamics of open quantum systems using QMEs. |

Plotted Spectral Density J(ω) |

The critical output of the MD analysis, serving as the input function for the QME solver. |

5. Impact of Environmental Decoherence

The hybrid model explicitly shows how the environment suppresses quantum effects. The following diagram conceptualizes this process.

Environmental Decoherence Pathway

Table 3: Decoherence Effects on Ground State Calculations

| Calculation Context | Isolated Molecule Result | Hybrid Model (with Decoherence) Result |

|---|---|---|

| Ground State Energy | E_iso | E_iso + λ (Stabilized by reorganization energy) |

| Electronic Coherence Lifetime | Infinite (in theory) | Finite, ~1/γ (typically femtoseconds to picoseconds) |

| Transition Pathway | Quantum superposition of paths | Classical-like population transfer, suppressed interference |

6. Conclusion

Hybrid Atomistic-Parametric Models provide a powerful and computationally tractable framework for investigating molecular quantum processes in realistic environments. By rigorously integrating MD simulations with Quantum Master Equations, this approach directly addresses the critical role of environmental decoherence. It demonstrates that the molecular ground state is not an isolated eigenvalue but a dynamically stabilized entity, a finding with profound implications for predicting reaction rates, spectral properties, and ultimately, for the rational design of molecules in drug development and materials science.

Lindblad Master Equations for Dissipative Ground State Preparation

Within molecular ground state calculations, environmental decoherence has traditionally been viewed as a detrimental effect that complicates the accurate prediction of chemical properties. This decoherence, the process by which a quantum system loses its coherence through interactions with its environment, inevitably leads to the degradation of quantum information [21] [1]. However, a paradigm shift is underway, recasting dissipation not as an obstacle to be mitigated but as a powerful resource for quantum state preparation [26]. The Lindblad master equation provides a robust theoretical framework for this engineered approach, enabling researchers to steer quantum systems toward their ground states through carefully designed dissipative dynamics [26] [27]. This guide explores how the Lindblad formalism transforms our approach to molecular ground state problems, offering novel methodologies that circumvent the limitations of purely coherent algorithms, particularly for systems lacking geometric locality or favorable sparsity structures, which are common in ab initio electronic structure theory [26].

The core challenge in molecular quantum chemistry is the preparation of the ground state of complex Hamiltonians, a prerequisite for predicting chemical reactivity, spectroscopic properties, and electronic behavior. Conventional quantum algorithms often require an initial state with substantial overlap with the target ground state, a condition difficult to satisfy for many molecular systems [26]. Dissipative engineering using the Lindblad master equation inverts this logic, encoding the ground state as the unique steady state of a dynamical process, thereby offering a powerful alternative that is parameter-free and inherently resilient to certain classes of errors [26] [27].

Theoretical Foundations of the Lindblad Master Equation

The dynamics of an open quantum system interacting with its environment are generically described by the Lindblad master equation, which governs the time evolution of the system's density matrix, Ï:

$$\frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}t}\rho = \mathcal{L}[\rho] = -i[\hat{H}, \rho] + \sumk \left( \hat{K}k \rho \hat{K}k^\dagger - \frac{1}{2} { \hat{K}k^\dagger \hat{K}_k, \rho } \right)$$

This equation consists of two distinct parts: the coherent Hamiltonian dynamics, captured by the commutator term -i[\hat{H}, \rho], and the dissipative Lindbladian dynamics, described by the sum over the jump operators \hat{K}_k [26]. These jump operators model the system's interaction with its environment and are the central components for engineering desired dissipative dynamics.

The Mechanism of Engineered Decoherence

Unlike uncontrolled environmental decoherence, which randomly disrupts quantum superpositions, the engineered dissipation in this framework is purposefully designed to channel the system toward a specific target state—the ground state. The mathematical mechanism is elegant: the jump operators are constructed such that the ground state is a dark state, satisfying \hat{K}_k |\psi_0\rangle = 0 for all k. Consequently, the ground state remains invariant under the dissipative dynamics [26]. Furthermore, for all other energy eigenstates, the jump operators facilitate transitions that progressively lower the system's energy, effectively "shoveling" population from high-energy states toward the ground state [26]. This process leverages decoherence constructively, as the off-diagonal elements of the density matrix in the energy basis are suppressed, driving the system into a stationary state that corresponds to the ground state of the Hamiltonian.

Table 1: Key Components of the Lindblad Master Equation for Dissipative Ground State Preparation

| Component | Mathematical Form | Physical Role | Effect on Ground State | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hamiltonian | \hat{H} |

-i[\hat{H}, \rho] |

Governs coherent dynamics of the closed system | Determines the energy spectrum and target state |

| Jump Operator | \hat{K}_k |

\sum \hat{f}(\lambda_i-\lambda_j)\langle\psi_i|A_k|\psi_j\rangle|\psi_i\rangle\langle\psi_j| |

Induces engineered transitions between energy levels | Dark state: \hat{K}_k|\psi_0\rangle=0 |

| Filter Function | \hat{f}(\omega) |

\hat{f}(\lambda_i - \lambda_j) |

Energy-selective filtering; non-zero only for \omega < 0 |

Ensures transitions only lower energy |

Jump Operator Design for Molecular Systems

A critical challenge in applying dissipative ground state preparation to ab initio quantum chemistry is the lack of geometric structure in molecular Hamiltonians. Unlike lattice models with nearest-neighbor interactions, molecular Hamiltonians feature long-range, all-to-all interactions, complicating the design of effective jump operators [26]. Recent research has introduced two generic classes of jump operators that address this challenge.

Type-I and Type-II Jump Operators

For general ab initio electronic structure problems, two simple yet powerful types of jump operators have been developed, termed Type-I and Type-II [26].

Type-I operators are defined in the Fock space as \mathcal{A}_\text{I} = \{a_i^\dagger | i=1,\cdots,2L\} \cup \{a_i | i=1,\cdots,2L\}, encompassing all fermionic creation and annihilation operators across 4L spin-orbitals [26]. These operators fundamentally break the particle-number symmetry of the Hamiltonian. While this makes them applicable to a broad range of states, it necessitates simulation in the full Fock space, increasing computational resource requirements.

Type-II operators preserve the particle-number symmetry of the original Hamiltonian [26]. This symmetry preservation allows for more efficient simulation in the full configuration interaction (FCI) space, reducing the computational overhead significantly. The particle-number conserving property makes Type-II operators particularly suitable for molecular systems where the number of electrons is fixed.

Table 2: Comparison of Jump Operator Types for Molecular Systems

| Characteristic | Type-I Jump Operators | Type-II Jump Operators |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Form | Creation/annihilation operators: a_i^\dagger, a_i |

Particle-number conserving operators |

| Symmetry | Breaks particle-number symmetry | Preserves particle-number symmetry |

| Simulation Space | Full Fock space | Full configuration interaction (FCI) space |

| Number of Operators | O(L) |

O(L) |

| Implementation Efficiency | Moderate | High (due to symmetry) |

| Suitable Systems | General states, including superconducting systems | Molecular systems with fixed electron count |

Construction and Filter Function Implementation

The jump operators \hat{K}_k are constructed from primitive coupling operators A_k through energy filtering in the Hamiltonian's eigenbasis [26]:

\[

\hat{K}_k = \sum_{i,j} \hat{f}(\lambda_i - \lambda_j) \langle \psi_i | A_k | \psi_j \rangle | \psi_i \rangle \langle \psi_j |

\]

The filter function \hat{f}(\omega) plays the crucial role of ensuring that transitions only occur when they lower the energy of the system (\omega < 0). While this construction appears to require full diagonalization of the Hamiltonian, it can be efficiently implemented in the time-domain using [26]:

\[

\hat{K}_k = \int_{\mathbb{R}} f(s) A_k(s) \mathrm{d}s

\]

where A_k(s) = e^{i\hat{H}s} A_k e^{-i\hat{H}s} represents the Heisenberg evolution of the coupling operator. This time-domain approach enables practical implementation on quantum computers using Trotter decomposition for time evolution [26].

Experimental Protocols and Computational Methodologies

Protocol for Dissipative Ground State Preparation

The following protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for implementing dissipative ground state preparation for ab initio molecular systems:

System Specification: Define the molecular Hamiltonian

\hat{H}in second quantization, specifying the number of spatial orbitals (L) and the basis set (e.g., atomic orbitals, molecular orbitals).Jump Operator Selection: Choose between Type-I or Type-II jump operators based on the system requirements:

- Select Type-I for maximum generality when particle number conservation is not essential

- Select Type-II for improved efficiency when particle number is conserved [26]

Filter Function Design: Implement a filter function

\hat{f}(\omega)that satisfies the energy-selective criterion:\hat{f}(\omega) = 0for\omega \geq 0\hat{f}(\omega) > 0for\omega < 0- The specific form depends on spectral estimates of the Hamiltonian [26]

Time Evolution Setup: Initialize the system in an arbitrary state

\rho(0). For efficiency, choose a state with non-negligible overlap with the true ground state if possible.Lindblad Dynamics Simulation: Evolve the system according to the Lindblad master equation using numerical solvers or quantum simulation algorithms:

Convergence Monitoring: Track convergence through observables such as:

- Energy expectation value

\langle \hat{H} \rangle(t) - Reduced density matrix elements

- Distance from the target state (if known)

- Energy expectation value

Steady-State Verification: Confirm convergence to the ground state by verifying that the state remains invariant under further time evolution and satisfies

\hat{K}_k \rho_\text{ss} = 0for all jump operators.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Lindblad-Based Ground State Preparation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples/Requirements | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Hamiltonian Representation | Second-quantized operators, Molecular orbital integrals | Encodes the electronic structure problem for quantum simulation |

| Jump Operator Library | Type-I (creation/annihilation), Type-II (number-conserving) | Implements the dissipative elements for ground state preparation |

| Time Evolution Solvers | Trotter decomposition, Monte Carlo trajectory methods | Simulates the Lindblad dynamics on classical or quantum hardware |

| Filter Functions | Energy-selective filters with negative frequency support | Ensures transitions preferentially lower the system energy |

| Convergence Metrics | Energy tracking, Reduced density matrix analysis | Monitors progress toward the ground state and assesses accuracy |

| Active Space Tools | Orbital selection algorithms, Entropy-based truncation | Reduces computational cost while preserving accuracy in large systems |

Applications to Molecular Systems and Performance Analysis

The dissipative ground state preparation approach has been successfully validated on several molecular systems, demonstrating its capability to achieve chemical accuracy even in challenging strongly correlated regimes [26].

Performance in Model Molecular Systems

Numerical studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of Lindblad dynamics for ground state preparation in systems including BeHâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚O, and Clâ‚‚ [26]. These studies employed a Monte Carlo trajectory-based algorithm for simulating the Lindblad dynamics for full ab initio Hamiltonians, confirming the method's capability to prepare quantum states with energies meeting chemical accuracy thresholds (approximately 1.6 mHa or 1 kcal/mol). Particularly noteworthy is the application to the stretched square Hâ‚„ system, which features nearly degenerate low-energy states that pose significant challenges for conventional quantum chemistry methods like CCSD(T) [26]. In such strongly correlated regimes, the dissipative approach maintains robust performance, highlighting its potential for addressing outstanding challenges in electronic structure theory.