Hardware-Efficient Ansatz Design for Noisy Quantum Chemistry: Strategies for NISQ-Era Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to hardware-efficient ansatz (HEA) design for quantum chemistry simulations on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware.

Hardware-Efficient Ansatz Design for Noisy Quantum Chemistry: Strategies for NISQ-Era Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to hardware-efficient ansatz (HEA) design for quantum chemistry simulations on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles of HEAs and their trade-offs, explores advanced methodologies like the Sampled Quantum Diagonalization (SQD) and machine-learning-assisted parameter optimization, and details practical troubleshooting for noise mitigation and optimizer selection. The content further validates these approaches through benchmarking studies and comparative analysis with classical methods, offering a clear pathway for applying quantum computing to molecular energy calculations and accelerating biomedical research.

Understanding Hardware-Efficient Ansatzes: The Foundation of NISQ Quantum Chemistry

A hardware-efficient ansatz (HEA) is a design paradigm for parameterized quantum circuits that prioritizes compatibility with the physical constraints of a specific quantum processor. The primary goal of an HEA is to minimize the detrimental effects of hardware noise—the dominant challenge on today's Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices—by using shallow circuit depths and a gate set native to the target hardware [1]. This approach stands in contrast to ansatzes derived purely from problem structure, such as those used in quantum chemistry, which may require deep circuits and gates that are inefficient to implement on real devices.

Within quantum chemistry research, HEAs have been successfully employed in variational algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) to find the ground-state energies of molecules [1] [2]. Their practical usefulness, however, is ambivalent; while shallow HEAs can help avoid the barren plateau problem (where gradients vanish exponentially with qubit count), they can also suffer from it at longer depths [3]. Therefore, their design represents a critical compromise between expressibility, trainability, and hardware feasibility.

Core Design Principles

The construction of a hardware-efficient ansatz is guided by several key principles aimed at maximizing fidelity on imperfect hardware.

- Utilization of Native Gate Sets: An HEA is constructed primarily from gates that are directly and efficiently implemented by the hardware, such as single-qubit rotations (e.g.,

R_X,R_Y,R_Z) and specific two-qubit entangling gates (e.g.,CNOT,CZ, oriSWAP). This minimizes the number of physical operations required to execute a logical gate, reducing the circuit's exposure to decoherence and gate errors. - Conformity to Qubit Connectivity: The circuit's entangling gates are applied only between physically connected qubits on the processor's architecture (e.g., linear, grid, or all-to-all connectivity). This avoids the need for costly SWAP networks, which increase circuit depth and error rates.

- Minimization of Circuit Depth: By design, HEAs employ a layered, relatively shallow structure. This short runtime is essential for completing computation before quantum states decohere, making them a pragmatic choice for NISQ-era quantum chemistry simulations [1].

- Consideration of Input State Entanglement: The trainability of an HEA is profoundly influenced by the entanglement of its input states. Research indicates that HEAs are untrainable for tasks with input data following a volume law of entanglement but can be effectively used for tasks with data following an area law of entanglement, thus avoiding barren plateaus [3].

Protocol for Ansatz Design and Application in Quantum Chemistry

The following workflow outlines the key stages for designing and deploying a hardware-efficient ansatz for a quantum chemistry problem, such as estimating the ground state energy of a molecule using VQE.

Procedure Notes

Hardware Analysis (Step 2): Critical hardware specifications to catalog include:

- Native Gate Set: Identify the specific single- and two-qubit gates with the highest fidelities.

- Qubit Connectivity Map: Obtain the graph of directly coupled qubits.

- Coherence Times (T1/T2): Estimate the maximum feasible circuit depth.

- Gate Errors: Understand the primary sources of noise in the system.

Ansatz Construction (Steps 3-4): A typical HEA layer consists of blocks of single-qubit rotations on all qubits, followed by two-qubit entangling gates applied along the hardware's connectivity links. This sequence is repeated for a predetermined number of layers (

L), creating the full parameterized circuit.Optimization (Step 6): The VQE loop is hybrid quantum-classical. The quantum processor is used to prepare the ansatz state and measure the energy expectation value. A classical optimizer (e.g., COBYLA, SPSA) then proposes new parameters to minimize this energy. Barren plateaus pose a significant risk here, underscoring the need for careful ansatz design [3].

Alternative and Advanced Methods

As the field progresses, purely hardware-efficient approaches are being integrated with problem-aware techniques to create more powerful hybrid algorithms.

The SQDOpt Framework: For quantum chemistry, the Optimized Sampled Quantum Diagonalization (SQDOpt) algorithm presents an alternative to VQE. It uses a hardware-efficient ansatz but optimizes it on the quantum hardware using a fixed, small number of measurements per optimization step, addressing VQE's high measurement budget challenge [2]. In this framework, the optimized ansatz is evaluated once classically to obtain a high-precision final solution.

Learning from Data for Error Correction: While not an ansatz design technique per se, machine learning is being used to create more accurate decoders for quantum error correction codes like the surface code [4]. By learning directly from hardware data, these decoders can compensate for complex noise patterns, effectively boosting the performance of algorithms run on that hardware, including those using HEAs.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for HEA Experimentation

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Native Gate Set | The physically implemented set of quantum gates on a specific processor (e.g., RZ, √X, CZ). |

Using only RZ, RY, and CZ gates to construct an ansatz for a superconducting qubit processor. |

| Connectivity Map | A graph representing which qubits in a processor can directly interact via two-qubit gates. | Designing entangling layers so that CZ gates are only applied between adjacent qubits on a linear chain. |

| Parameterized Quantum Circuit (PQC) | A quantum circuit containing free parameters, typically in rotational gates, which are optimized during training. | The core object of an HEA, built from layers of native rotations and entangling gates. |

| Classical Optimizer | An algorithm that updates the PQC's parameters to minimize a cost function (e.g., energy). | Using the COBYLA or SPSA optimizer in a VQE loop to find a molecule's ground state energy. |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Software and methodological techniques to reduce the impact of noise on measurement results. | Applying zero-noise extrapolation to energy measurements from a shallow HEA circuit. |

| Barren Plateau Mitigation Strategies | Methods to avoid or escape regions in the parameter landscape where gradients vanish. | Initializing the HEA with parameters that generate low-entanglement states for area-law data [3]. |

| Thiacloprid | Thiacloprid, CAS:1119449-18-1, MF:C10H9ClN4S, MW:252.72 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Caloxin 2A1 TFA | Caloxin 2A1 TFA, MF:C66H92F3N19O24, MW:1592.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Discussion

Performance Analysis and Limitations

The primary advantage of HEAs—their minimal overhead on NISQ hardware—is also the source of their main limitations. Their problem-agnostic nature can lead to poor convergence or failure to capture the true ground state if the ansatz is not sufficiently expressive or is affected by noise. The barren plateau phenomenon remains a critical concern, as it can render optimization intractable for large systems [1] [3].

Furthermore, the use of a hardware-efficient ansatz in algorithms like VQE requires measuring the energy expectation value, which for molecular Hamiltonians can involve hundreds to thousands of non-commuting term measurements, creating a massive measurement overhead [2]. Advanced techniques like the SQDOpt framework are being developed specifically to address this bottleneck.

Future Directions

The future of hardware-efficient ansatzes lies in their intelligent integration with problem-specific knowledge. Hybrid ansatzes that combine hardware-efficient layers with chemically inspired unitary coupled cluster (UCC) components are a promising avenue. Furthermore, as hardware progresses towards the early fault-tolerant era with 25-100 logical qubits, the role of ansatzes will evolve [5]. On such platforms, more complex and deeper circuits will be feasible, potentially reducing the necessity for strict hardware-efficiency and enabling the use of more accurate, problem-specific ansatzes for quantum chemistry. The development of machine-learning-enhanced decoders [4] and error correction codes like the color code [6] will also extend the effective capabilities of the underlying hardware, indirectly benefiting all quantum algorithms, including those employing HEAs.

The Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era defines the current technological frontier of quantum computing, characterized by processors containing from tens to roughly a thousand qubits that operate without full error correction [7]. For researchers in quantum chemistry and drug development, these devices offer a tantalizing pathway to simulating molecular systems that are classically intractable. However, extracting scientifically valid results requires a meticulous understanding of the hardware limitations and the implementation of robust error mitigation strategies. This document provides application notes and experimental protocols framed within hardware-efficient ansatz design, detailing the current NISQ landscape and providing methodologies to navigate its constraints effectively.

Quantitative Analysis of the NISQ Hardware Landscape

The performance of NISQ devices is primarily defined by three interdependent physical parameters: qubit count, gate fidelity, and coherence time. The constraints imposed by these resources fundamentally shape the design and scope of feasible quantum chemistry experiments.

Current NISQ Device Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance metrics of representative NISQ hardware platforms.

| Platform | Typical Qubit Count | 2-Qubit Gate Fidelity (%) | Coherence Times (Tâ‚ / Tâ‚‚) | Gate Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superconducting (e.g., IBM, Google) | 27 - 1,000+ [7] [8] | 98.6 - 99.7 [8] | ~100 μs [8] | ~100 ns [8] |

| Trapped Ion (e.g., IonQ, Quantinuum) | ~11 - 50 [9] [8] | 99.8 - 99.9 [8] | 1 - 10 seconds [8] | 50 - 200 μs [8] |

| Neutral Atom (e.g., Pasqal) | Up to 100 [8] | 97 - 99 [8] | 0.1 - 1 second [8] | ~1 ms [8] |

NISQ Operational Constraints and Their Impact on Algorithms

The operational envelope of a NISQ device is determined by the total error accumulation throughout a circuit's execution. The approximate limit is given by ( N \cdot d \cdot \epsilon \ll 1 ), where ( N ) is the qubit count, ( d ) is the circuit depth, and ( \epsilon ) is the two-qubit gate error rate [8]. With per-gate error rates (( \epsilon )) typically between ( 10^{-3} ) and ( 10^{-2} ), the maximum allowable circuit depth (( d_{\text{max}} )) is severely constrained, often to the order of ( 10^2 ) to ( 10^3 ) gates [8].

Table 2: Algorithmic resource requirements and NISQ compatibility.

| Algorithm / Task | Minimum Qubits | Required Circuit Depth | Tolerance to Error Rates | NISQ Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VQE (Small Molecules) | 4-20 [2] | Moderate (100s of gates) | ( \epsilon < 10^{-4} ) for chemical accuracy [8] | Moderate (Requires aggressive error mitigation) |

| QAOA (MaxCut) | 10s-100s [7] | Shallow to Moderate | Model-dependent [8] | Low to Moderate (Performance gains elusive at small scale) |

| Quantum Machine Learning | 10s | Shallow to Moderate | Varies by model and data [3] | Moderate (Highly dependent on data encoding) |

| Digital Quantum Simulation | 10s-100s | High (1000s of gates) | Very Low (< ( 10^{-5} )) | Low (Except for highly Trotterized or simplified models) |

For quantum chemistry, the Hardware Efficient Ansatz (HEA) has emerged as a leading approach due to its minimal gate count and use of a device's native gates [3]. Its trainability, however, is highly dependent on the entanglement characteristics of the input data; it is most suitable for problems where the target wavefunction satisfies an area law of entanglement, a property common to many molecular ground states [3].

Experimental Protocols for Reliable NISQ Experimentation

The following protocols provide a structured methodology for deploying and validating hardware-efficient quantum chemistry simulations on NISQ hardware.

Protocol 1: Pre-Runtime Hardware Characterization and Calibration

Objective: To select the optimal device and qubit subset for a given experiment by assessing current hardware performance metrics.

- Metric Retrieval: Access the provider's calibration data (typically updated daily) to obtain for each qubit and link:

- Qubit Selection: Use a constraint-based compiler to map the program's logical qubits to the physical qubits with the highest aggregate fidelity and longest coherence times, while also minimizing the need for long-range communication via SWAP gates [8].

- Dynamic Benchmarking: Execute a short benchmarking circuit (e.g., a mirror circuit or randomized benchmarking) on the selected qubit subset immediately before the main experiment to validate the reported metrics and establish a baseline for error mitigation [9].

Protocol 2: Execution of a Mitigated Hardware-Efficient Ansatz Workflow

This protocol outlines the core hybrid quantum-classical loop for a Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) using a HEA, enhanced with integrated error mitigation.

Objective: To compute the ground-state energy of a molecular system (e.g., Hâ‚‚, LiH, Hâ‚‚O) using a noise-resilient, hybrid quantum-classical approach.

```dot

In the field of noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) computing, the design of the parameterized quantum circuit, or ansatz, represents a fundamental engineering compromise. This is particularly true for quantum chemistry applications such as drug development and materials science, where accurately simulating molecular electronic states is crucial. The core tension lies in balancing two competing properties: expressibility—the ability of an ansatz to represent a wide range of quantum states, including the complex entangled states of molecular systems—and trainability—the practical optimization of circuit parameters to find a specific state, such as a molecular ground state [11].

Achieving this balance is not merely theoretical. Under the NISQ paradigm, highly expressive ansatze requiring deep circuits often encounter severe limitations. Hardware noise accumulates with circuit depth, and the optimization landscape can suffer from barren plateaus, where gradients vanish exponentially with system size, rendering effective training impossible [11] [12]. Consequently, hardware-efficient ansatz design has emerged as a critical research focus, seeking architectures that maintain sufficient expressibility for target problems while remaining practically trainable on available hardware.

Theoretical Foundation: Defining the Trade-off

Expressibility and Its Demands

Expressibility measures the capability of a variational quantum circuit to generate states that closely approximate the full Hilbert space. In quantum chemistry, high expressibility is necessary to capture strong electron correlations and complex multi-reference character in molecules, which are critical for predicting reaction pathways and properties in drug candidates. Ansatze are typically made more expressive by incorporating a larger number of parameterized gates and entangling layers, increasing the circuit's depth and complexity [11].

Trainability and Its Pitfalls

Trainability refers to the efficiency and effectiveness of optimizing the parameters of an ansatz using classical methods. The primary obstacle to trainability is the barren plateau phenomenon, where the variance of the cost function gradient vanishes exponentially as the number of qubits increases [11]. On NISQ hardware, this theoretical problem is exacerbated by gate infidelities, decoherence, and readout errors, which further corrupt gradient information and impede convergence [13] [12]. A deeply expressive ansatz, if it leads to barren plateaus or is overwhelmed by noise, becomes useless for practical computation.

Table 1: Core Concepts in Ansatz Design

| Concept | Definition | Impact on Quantum Chemistry Simulations |

|---|---|---|

| Expressibility | The ability of an ansatz to generate a broad set of quantum states. | Determines whether the target molecular ground state or excited states are within reach of the variational algorithm. |

| Trainability | The ease of optimizing ansatz parameters via classical optimizers. | Directly affects the convergence, resource cost, and final accuracy of energy estimations like those in VQE. |

| Barren Plateaus | The exponential decay of cost function gradients with increasing qubit count. | Renders optimization of expressive ansatze intractable for large molecules, a key challenge in drug development. |

| Hardware Efficiency | The co-design of ansatze to match a quantum processor's native gates, connectivity, and noise profile. | Reduces circuit depth and fidelity loss, making simulations of small molecules feasible on current hardware. |

Quantitative Analysis of the Trade-off in Practice

The expressibility-trainability trade-off is not merely theoretical; it has concrete, measurable consequences on algorithmic performance. Recent studies provide quantitative evidence of this relationship.

The Sampled Quantum Diagonalization (SQD) method and its optimized variant (SQDOpt) address the measurement overhead of traditional VQE. While VQE may require "hundreds to thousands of bases to estimate energy on hardware, even for molecules with less than 20 qubits," methods like SQDOpt use a fixed, small number of measurements per optimization step (e.g., as few as 5) to guide the optimization of a quantum ansatz [2] [14]. This represents a direct engineering trade-off: by strategically limiting the information used in each step (potentially sacrificing the expressibility of the immediate energy estimation), the overall trainability of the model is enhanced, leading to more robust convergence on noisy hardware. Numerical simulations across eight different molecules showed that this approach could reach minimal energies equal to or lower than full VQE in most cases [2].

Furthermore, the choice of ansatz significantly affects performance relative to classical methods. Compared to classical Self-Consistent Field (SCF) calculations, algorithms like SQDOpt can provide superior solutions for molecules with a high ratio of off-diagonal terms in their Hamiltonian, where the expressibility of the quantum ansatz offers a distinct advantage [2].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Quantum Chemistry Algorithms

| Algorithm / Technique | Key Principle | Expressibility | Trainability & Resource Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz VQE [11] [12] | Uses an ansatz built from a device's native gates. | Moderate; limited by circuit depth to maintain fidelity on NISQ devices. | Challenging; prone to barren plateaus and noise. High measurement overhead. |

| SQDOpt [2] [14] | Combines classical diagonalization with multi-basis quantum measurements. | High; leverages quantum ansatz but can be limited by the sampled subspace. | Improved; uses fixed, low measurements per step for more robust optimization. |

| Quantum Architecture Search (QAS) [11] | Automatically searches for a near-optimal ansatz structure. | Adaptive; the algorithm discovers a structure that balances expressivity and noise resistance. | Enhanced; explicitly optimizes for trainability by inhibiting noise and barren plateaus. |

| Classical SCF [2] | A standard classical method for quantum chemistry. | Low; limited by the mean-field approximation. | High; a mature, robust, and fast classical algorithm. |

Experimental Protocols for Ansatz Evaluation

For researchers aiming to empirically validate new ansatze, the following protocols provide a framework for benchmarking.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Expressibility vs. Depth

This protocol measures the impact of increasing ansatz complexity.

- Ansatz Selection: Choose a parameterized ansatz template (e.g., hardware-efficient with alternating layers of single-qubit rotations and entangling gates).

- System Preparation: Select a target molecular system (e.g., Hâ‚‚, LiH) and generate its qubit Hamiltonian using a classical quantum chemistry package (e.g., PySCF).

- Variational Optimization: For a range of circuit depths (L = 1, 2, 4, 8, ...), run the VQE algorithm to find the ground state energy.

- Data Collection & Analysis:

- Record the final energy error relative to the exact Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) energy.

- For each depth, track the number of optimization iterations required for convergence and the variance of the energy gradient in the final stages.

Expected Outcome: Initially, deeper circuits (higher expressibility) will yield lower energy errors. However, beyond a problem-specific depth, trainability will degrade, manifested as a rising energy error, failure to converge, or vanishing gradients, indicating the onset of a barren plateau.

Protocol 2: Quantum Architecture Search (QAS)

This protocol outlines the automated search for an optimal ansatz, as detailed in [11].

- Supernet Initialization: Define a large, over-parameterized "supernet" that contains all possible candidate ansatze within its structure. This involves setting a maximum circuit depth and a set of allowed quantum gates.

- Weight-Sharing Optimization: Instead of training every possible sub-ansatz independently, train the entire supernet once. Parameters are shared among different sub-architectures, drastically reducing the computational overhead.

- Architecture Ranking: Evaluate different sub-ansatze (architectures) sampled from the trained supernet on the target task (e.g., molecular energy estimation).

- Fine-Tuning: Take the highest-performing architecture(s) and perform a final, dedicated optimization of its parameters.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the QAS protocol, which enables the automated discovery of high-performance ansatze.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful experimentation in this field relies on a suite of conceptual and software "reagents." The following table details key components.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Ansatz Research

| Tool / Technique | Function in Research | Relevance to Trade-off |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz [11] [12] | A parameterized circuit template constructed from a quantum device's native gates and connectivity. | Maximizes initial trainability and fidelity on a specific device, but may limit expressibility. |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) [15] [12] | An error mitigation technique that intentionally scales up circuit noise to extrapolate back to a zero-noise result. | Indirectly aids trainability by providing cleaner signal for gradients, allowing for slightly more expressive circuits. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) [13] | A method to characterize and correct for readout errors on the quantum hardware. | Mitigates a key source of noise that corrupts cost function evaluation, directly improving trainability. |

| Locally Biased Classical Shadows [13] | A measurement strategy that prioritizes measurement settings with a bigger impact on the final observable. | Reduces "shot overhead" (number of measurements), making the optimization of more complex ansatze more feasible. |

| Supernet [11] | An over-parameterized circuit that encompasses many smaller sub-circuits (ansatze) within its structure. | The core component of QAS, enabling the efficient search for an ansatz that balances expressivity and noise resilience. |

| Casein hydrolysate | Casein Acid Hydrolysate for Research Applications | Casein acid hydrolysate is a peptone reagent for cell culture, microbiology, and bioactive peptide research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Isocycloseram | Isocycloseram|Novel Isoxazoline Insecticide|RUO | Isocycloseram is a broad-spectrum IRAC Group 30 insecticide for research. It is a GABA-gated chloride channel modulator. For Research Use Only. Not for personal use. |

The careful management of the expressibility-trainability trade-off is the cornerstone of performing meaningful quantum chemistry simulations on today's NISQ devices. While no single ansatz template is universally optimal, strategies like Sampled Quantum Diagonalization (SQDOpt) and Quantum Architecture Search (QAS) provide powerful frameworks for navigating this design space. These approaches move beyond fixed ansatze, instead leveraging hybrid quantum-classical workflows to find problem-specific circuits that are both sufficiently expressive and practically trainable.

The future of hardware-efficient ansatz design lies in tighter integration across the stack. This includes developing ansatze that are not only hardware-efficient but also problem-inspired, incorporating known molecular symmetries and structures to enhance expressibility without gratuitous depth. Furthermore, as demonstrated by techniques like QDT and ZNE, advanced error mitigation will remain essential for stretching the capabilities of available hardware. For researchers in drug development, these evolving methodologies promise gradually increasing capacity to model complex molecular interactions, bringing quantum computing closer to becoming a practical tool in the pipeline of materials and pharmaceutical discovery.

In the pursuit of quantum advantage on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware, the design of variational quantum ansatze is paramount. The scalability and performance of these parameterized circuits are profoundly influenced by the entanglement structure of the input states they act upon. Entanglement, a quintessential quantum resource, exhibits distinct scaling behaviors commonly categorized as area laws and volume laws.

An area law denotes that the entanglement entropy between a subsystem and the rest of the system scales proportionally to the size of their shared boundary area. In contrast, a volume law signifies scaling with the size (volume) of the subsystem itself [16]. For quantum many-body systems, area laws are typical for ground states of gapped, local Hamiltonians, whereas volume laws are characteristic of highly excited or thermal states. The choice between an area-law and a volume-law-inspired input state presents a critical trade-off between efficiency and expressibility in algorithm design, directly impacting the feasibility of quantum chemistry simulations on resource-constrained devices.

Theoretical Foundation of Area and Volume Laws

The mathematical formulation of entanglement entropy is grounded in the bipartite quantum system framework. For a system partitioned into two subsystems, A and B, the entanglement entropy is the von Neumann entropy of the reduced density matrix of either subsystem: ( SA = -\text{Tr}(\rhoA \ln \rhoA) ), where ( \rhoA = \text{Tr}B(\rho{AB}) ). The scaling law dictates how ( S_A ) grows with the linear size ( L ) of subsystem A.

Area Law

An area law is expressed as ( S_A \sim L^{d-1} ) for a system in ( d ) spatial dimensions. In practical terms, for a one-dimensional (1D) chain, the entanglement entropy saturates to a constant independent of subsystem size (( L^0 )), while in two dimensions (2D), it scales with the boundary length ( L ) [17] [18]. This scaling is a consequence of the limited correlation structure found in states like low-energy ground states.

- Cluster State Example: The 2D cluster state, a resource for measurement-based quantum computation, obeys an area law for entanglement entropy. Analysis shows that the entropy ( S ) of any bipartition is bounded by ( S \le |E'| ), where ( |E'| ) is the number of edges straddling the partition. This means the entropy scales at most with the length of the boundary, not the area of the interior [17].

- Field Theory Context: For free quantum scalar fields in (3+1)-dimensional Minkowski spacetime, the entanglement entropy and its fluctuation (characterized by the capacity of entanglement) both exhibit the area law for spherical and strip entangling surfaces [18].

Volume Law

A volume law is expressed as ( S_A \sim L^d ), meaning the entanglement entropy scales extensively with the subsystem's volume. This is the maximal scaling possible and is typical for random states in Hilbert space or thermal states.

- Generation via Measurements: Counterintuitively, volume-law entanglement can be generated without unitary dynamics. Recent research demonstrates that repeated local, non-commuting measurements, even of one-body operators, can drive a system into a steady state with volume-law entanglement or mutual information between different parts [19]. This highlights that measurement-only dynamics, under the right conditions, can be a potent source of entanglement.

Table 1: Characteristics of Entanglement Scaling Laws

| Feature | Area Law | Volume Law |

|---|---|---|

| Scaling with Subsystem Size | Proportional to boundary area (( L^{d-1} )) | Proportional to subsystem volume (( L^d )) |

| Typical States | Ground states of gapped, local Hamiltonians | Random states, thermal states, highly excited states |

| Computational Tractability | Often classically simulable with MPS/DMRG | Generally difficult to simulate classically |

| Resource Requirement for Quantum Simulation | Lower | Higher |

| Example | 2D Cluster State [17] | States generated by non-commuting local measurements [19] |

Implications for Quantum Chemistry Ansatz Design

The choice of an input state with an area-law or volume-law entanglement profile has direct consequences for the efficiency and success of variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) in quantum chemistry.

The Measurement Bottleneck and Hardware-Efficient Ansatze

A primary challenge for VQAs like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) on NISQ devices is the measurement bottleneck. The molecular Hamiltonian, when expressed in the Pauli basis, consists of a large number of non-commuting terms, even for small molecules. This necessitates a vast number of measurements to estimate the energy expectation value, which is computationally expensive [2].

Hardware-efficient ansatze (HEA) are designed to address this by using shallow quantum circuits tailored to a specific quantum processor's native gates and connectivity. This approach reduces circuit depth and decoherence at the potential cost of problem-specific intuition [20].

Area-Law-Inspired Inputs for Ground State Problems

For the specific task of finding ground states of molecular systems—a central problem in quantum chemistry—area-law-inspired inputs are often advantageous.

- The SQDOpt Framework: The Sampled Quantum Diagonalization (SQD) method and its optimized variant (SQDOpt) represent a hardware-efficient optimization scheme. SQDOpt leverages a quantum ansatz that is optimized on the hardware, but its efficacy is closely tied to the entanglement properties of the input state. The algorithm's performance is competitive with classical methods like DMRG, which is renowned for its efficient exploitation of area-law entanglement in 1D systems [2].

- Trapped-Ion Implementations: Hardware-efficient ansatze for trapped-ion systems (HEA-TI) leverage global spin-spin interactions across all ions. These ansatze are applied to problems like ground state energy calculation for molecules such as H(2), LiH, and F(2). The design prioritizes the generation of sufficient entanglement with low-depth circuits, a characteristic that aligns with area-law scaling for ground state approximations [20].

When Volume-Law States Are Beneficial

While area-law states are efficient for ground states, volume-law states play a role in a broader quantum simulation context.

- Simulating Dynamics and Thermal States: Simulating quantum quenches, thermalization, or high-energy states requires an ansatz capable of representing volume-law entanglement. The dynamics of entanglement after a quench, for instance, often involve a transition from area-law to volume-law scaling before eventual saturation [18].

- Measurement-Induced Entanglement: The finding that local measurements alone can generate volume-law entanglement [19] opens alternative pathways for state preparation on quantum hardware, potentially useful for preparing complex initial states for simulation.

Table 2: Application of Area Law vs. Volume Law States in Quantum Chemistry

| Aspect | Area-Law-Informed Strategy | Volume-Law-Informed Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Target Problem | Electronic ground state properties | Quantum dynamics, thermal states, scrambling |

| Ansatz Design Principle | Short-range entanglement, low-depth circuits | High expressibility, deeper circuits or novel measurement protocols |

| NISQ Compatibility | High (low resource demands) | Limited (high resource demands) |

| Example Algorithm | SQDOpt [2], HEA-TI [20] | Protocols using non-commuting measurements [19] |

| Classical Analog | Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG) | Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) - but with exponential cost |

Experimental Protocols for Entanglement Scaling Analysis

This section provides a detailed methodology for probing the entanglement structure of a prepared quantum state on hardware, a critical step in validating ansatz design.

Protocol 1: Estimating Entanglement Entropy via Bipartition

Objective: To quantify the entanglement entropy for a given bipartition of a quantum state prepared on a processor. Materials:

- Quantum processor (e.g., superconducting qubits, trapped ions)

- Classical optimizer

- Quantum state tomography or classical shadow protocols

Procedure:

- State Preparation: Prepare the target state ( |\psi\rangle ) on the quantum processor using the variational ansatz circuit.

- Bipartition: Define a bipartition of the system into subsystems A and B.

- Reconstruction: Perform quantum state tomography on the entire system to reconstruct ( \rho ), or use efficient methods like classical shadows to estimate the reduced density matrix ( \rhoA = \text{Tr}B(|\psi\rangle\langle\psi|) ).

- Entropy Calculation: Compute the von Neumann entropy ( SA = -\text{Tr}(\rhoA \ln \rhoA) ) classically from the estimated ( \rhoA ).

- Scaling Analysis: Repeat steps 2-4 for progressively larger subsystem sizes A (e.g., 1, 2, 3, ... qubits). Plot ( S_A ) as a function of the linear size ( L ) of A. An area law is indicated by saturation (in 1D) or linear scaling with ( L ) (in 2D), while a volume law is indicated by exponential scaling in ( L ).

Protocol 2: Verification of Area Law in 2D Cluster States

Objective: To experimentally confirm the area-law scaling in a 2D cluster state, as predicted theoretically [17]. Materials:

- A quantum processor capable of 2D qubit connectivity with nearest-neighbor interactions

- Single-qubit gates and controlled-phase (CZ) gates

Procedure:

- Initialization: Initialize all qubits in the product state ( \bigotimes |+\rangle ).

- Entanglement: Apply a controlled-Z gate between every pair of qubits that are nearest neighbors on the 2D lattice.

- Bipartition and Measurement: Choose a bipartition of the lattice (e.g., a contiguous block of qubits vs. the rest). Measure the entanglement entropy across this boundary using the method outlined in Protocol 1.

- Vary Partition Size: Systematically vary the size and shape of the partitioned block (e.g., 1x1, 2x2, 3x3 squares).

- Data Analysis: Plot the measured entanglement entropy against the length of the shared boundary ( |E'| ). The results should show a linear relationship, confirming the area law, as opposed to a relationship with the area (number of qubits) inside the partition.

Workflow for estimating entanglement entropy scaling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for Entanglement-Focused Quantum Experiments

| Component / Platform | Function / Description | Relevance to Entanglement Scaling |

|---|---|---|

| Trapped-Ion Quantum Simulator (HEA-TI) | Uses global spin-spin interactions for entangling gates. | Enables efficient preparation of states with area-law-like entanglement for molecular ground states [20]. |

| Sampled Quantum Diagonalization (SQDOpt) | A hybrid algorithm combining classical diagonalization with quantum ansatz optimization. | Reduces measurement burden; performance linked to the entanglement of the underlying quantum ansatz [2]. |

| Classical Shadows Protocol | An efficient method for estimating properties from few measurements. | Crucial for probing entanglement entropy without full tomography, reducing measurement overhead [2]. |

| Non-Commuting Local Measurements | A measurement-only dynamic protocol. | A tool for generating and studying volume-law entangled states without unitary evolution [19]. |

| Transverse Field Ising Model (TFIM) Hamiltonian | A common model for generating entanglement in spin systems. | The native interaction in many platforms (e.g., trapped ions) for constructing hardware-efficient ansatze [20]. |

| (R)-MLT-985 | (R)-MLT-985, MF:C17H15Cl2N9O2, MW:448.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| BT173 | BT173, MF:C18H12BrN3O2, MW:382.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implementation Guide for Hardware-Efficient Protocols

Designing an Area-Law-Compliant Ansatz for Molecules

For quantum chemistry problems targeting ground states, the following steps are recommended:

- Select a Hardware-Efficient Structure: Choose an ansatz composed of native gates. For example, on a trapped-ion processor, use layers of single-qubit rotations and global entangling evolution under the TFIM Hamiltonian [20].

- Initialize with a Simple State: Start from a product state or a weakly entangled state, such as the Hartree-Fock state, which inherently possesses an area-law entanglement structure.

- Optimize with a Hybrid Algorithm: Employ a classical optimizer in a VQE framework or use the SQDOpt method to refine the ansatz parameters. The classical optimizer's role is to navigate the circuit parameters to find the low-entanglement ground state without explicitly breaking the area law [2].

- Verify Entanglement Scaling: Periodically, during the optimization process, run Protocol 1 to ensure the entanglement of the prepared state remains consistent with an area law, preventing unnecessary resource consumption.

A Note on Error Mitigation and Volume Law

On NISQ devices, noise can inadvertently introduce entanglement that mimics a volume law, often as a result of decoherence and gate errors. This "noise-induced entanglement" is typically detrimental to computational accuracy.

- Monitoring as a Diagnostic: Tracking the entanglement scaling of the output state can serve as a powerful diagnostic tool for noise. A deviation from the expected area law towards a volume law during a ground state calculation can indicate significant noise corruption.

- Error Mitigation: Techniques such as zero-noise extrapolation should be applied. The effectiveness of these techniques can be verified by observing the restoration of area-law scaling in the mitigated results.

Iterative protocol for preparing area-law ground states on hardware.

Within the field of noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) computing, the Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA) has emerged as a pivotal framework for implementing variational quantum algorithms, particularly for quantum chemistry problems relevant to drug development. HEAs are designed to maximize performance on near-term quantum hardware by constructing parameterized quantum circuits (PQCs) from gates that are native to a specific quantum processor, thereby minimizing circuit depth and reducing the detrimental effects of noise [21]. This application note details the common architectural patterns of HEAs, their core components, and provides standardized protocols for their application in simulating molecular systems.

Architectural Components of HEAs

The fundamental structure of a HEA consists of repeated layers of rotation and entanglement gates, applied to a prepared reference state.

Core Gate Sets

The building blocks of HEA are selected from a quantum computer's native gate set to minimize the need for transpilation and reduce overall circuit depth.

- Single-Qubit Rotation Gates: These are the primary parameterized gates in the ansatz. Each rotation gate implements a unitary operation by an angle θ around a specific axis on the Bloch sphere [22].

- Rx(θ), Ry(θ), Rz(θ): Rotation gates around the x-, y-, and z-axes, respectively. Their matrix representations are:

- ( Rx(\theta) = \begin{pmatrix} \cos(\theta/2) & -i\sin(\theta/2) \ -i\sin(\theta/2) & \cos(\theta/2) \end{pmatrix} )

- ( Ry(\theta) = \begin{pmatrix} \cos(\theta/2) & -\sin(\theta/2) \ \sin(\theta/2) & \cos(\theta/2) \end{pmatrix} )

- ( R_z(\theta) = \begin{pmatrix} e^{-i\theta/2} & 0 \ 0 & e^{i\theta/2} \end{pmatrix} )

- Rx(θ), Ry(θ), Rz(θ): Rotation gates around the x-, y-, and z-axes, respectively. Their matrix representations are:

- Two-Qubit Entangling Gates: These gates create entanglement between qubits, which is essential for capturing electron correlations in quantum chemistry [23].

- Controlled-NOT (CNOT): A CNOT gate flips the target qubit if the control qubit is in state |1⟩.

- Controlled-Z (CZ): The CZ gate applies a phase flip of -1 to the state where both qubits are |1⟩.

- Initial Reference State: The circuit is typically initialized to a reference state, often the Hartree-Fock state, which is a classical product state encoding the mean-field solution of the molecular system [21].

Layered Structure

A HEA is constructed from ( L ) identical or similar layers. The general form of the ansatz state is: [ |\Psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle = \prod{l=1}^{L} Ul(\vec{\theta}l)|\Phi0\rangle ] Here, ( Ul(\vec{\theta}l) ) is the l-th layer of the circuit, parameterized by a vector of angles ( \vec{\theta}l ), and ( |\Phi0\rangle ) is the reference state [21]. A typical layer is composed of:

- A block of single-qubit rotation gates (e.g., ( Rx, Ry, R_z )) applied to all or a subset of qubits.

- A block of two-qubit entangling gates (e.g., CNOT or CZ) arranged according to the hardware's connectivity graph (e.g., linear or circular nearest-neighbor).

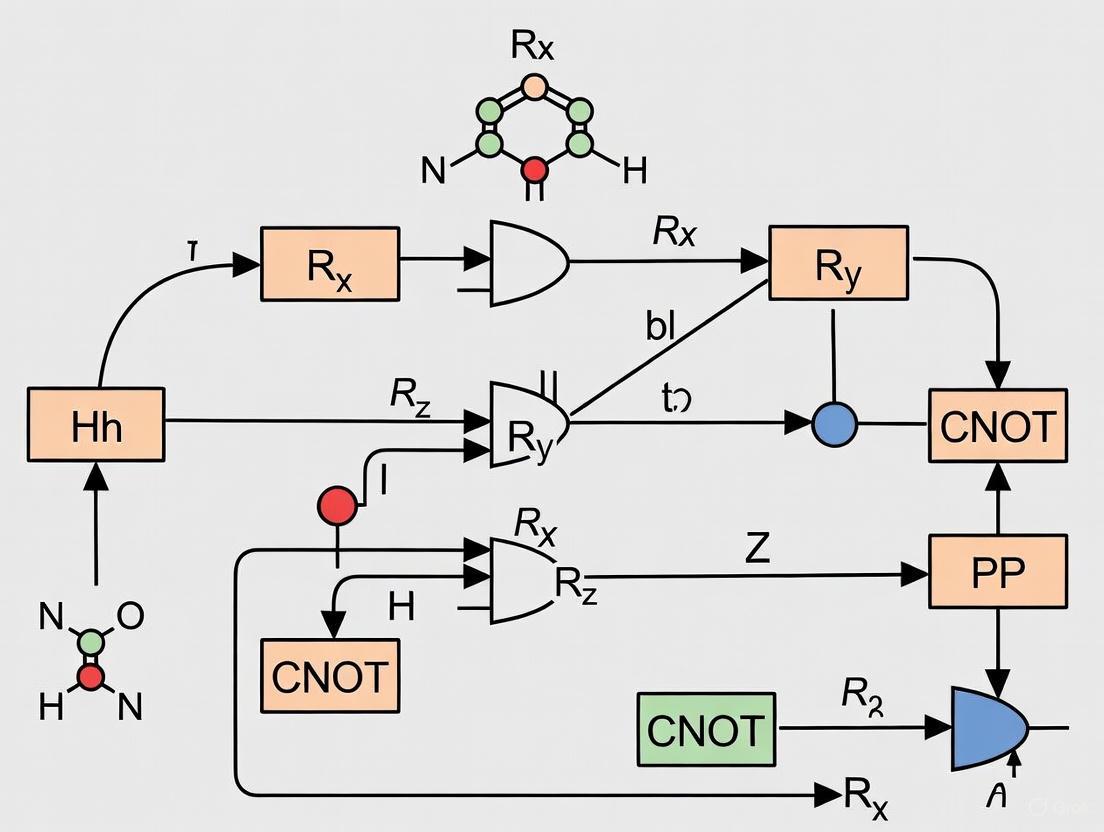

The following diagram illustrates the information flow and logical structure of a standard HEA layer.

Figure 1: Logical workflow of a Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA), showing the sequential application of layers to an initial reference state. Each layer comprises blocks of single-qubit rotations and entangling gates.

Quantitative Analysis of HEA Performance

The performance of different HEA architectures can be evaluated based on key metrics such as the number of parameters, circuit depth, and expressibility. The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison of different HEA types based on data from recent literature.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of HEA Architectures for Molecular Systems

| Molecule / System | HEA Type | Number of Qubits | Number of Layers | Parameters per Layer | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚O | Physics-Constrained HEA [21] | 12 | 4 | 24 | Accurate potential energy surfaces; superior to heuristically designed HEA |

| Hâ‚â‚‚ (20-qubit ring) | SQDOpt Framework [2] | 20 | N/A | N/A | Runtime crossover with classical VQE simulation at ~1.5 sec/iteration |

| Small Molecules | Shallow HEA (Area Law Data) [3] | <10 | 2-5 | Varies | Trainable and avoids barren plateaus |

| Small Molecules | Standard Layered HEA [23] | 4 | 2 | 24 | Circuit depth of 12 (with Rx, Ry, CNOT) |

The design of the HEA has profound implications on its trainability and scalability. The table below summarizes key theoretical guarantees and their practical implications for chemistry applications.

Table 2: Theoretical Constraints and Their Impact on HEA Design for Quantum Chemistry

| Theoretical Constraint | Formal Definition | Implication for Chemistry Simulation | Realized in Physics-Constrained HEA? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Universality [21] | Ansatz can approximate any quantum state arbitrarily well with sufficient depth. | Guarantees convergence to exact solution for complex electronic correlations. | Yes |

| Systematic Improvability [21] | ( VA^L \subseteq VA^{L+1} ), ensuring monotonic energy convergence. | Allows for controlled increase in accuracy by adding more layers. | Yes |

| Size-Consistency [21] | Energy of non-interacting subsystems A + B equals EA + EB. | Essential for scalable and accurate modeling of reaction pathways and dissociation. | Yes |

| Barren Plateau Avoidance [3] | Gradients do not vanish exponentially with qubit count for shallow depths. | Enables training for systems with area-law entanglement (e.g., ground states). | Context-Dependent |

Experimental Protocols for HEA in Quantum Chemistry

This section provides a detailed methodology for applying HEA to compute the ground-state energy of a molecule, a common task in drug development for understanding molecular stability and reactivity.

Protocol: Ground State Energy Calculation via VQE

Principle: The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm uses a hybrid quantum-classical loop to find the ground state energy of a molecular Hamiltonian by varying the parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) of a HEA to minimize the expectation value ( \langle \Psi(\vec{\theta}) | H | \Psi(\vec{\theta}) \rangle ) [2].

Procedure:

- Problem Formulation: a. Molecular Hamiltonian: Obtain the second-quantized electronic Hamiltonian ( H ) for the target molecule (e.g., water, methane) at a specific geometry. b. Qubit Mapping: Transform ( H ) into a qubit operator using a fermion-to-qubit mapping (e.g., Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev). c. Reference State Preparation: Initialize the quantum register to the Hartree-Fock state, ( |\Phi_0\rangle ).

Ansatz Definition and Parameter Initialization: a. Select HEA Architecture: Choose a layered HEA structure (e.g., Fig. 1) with a specific gate set (e.g.,

[OpType.Rx, OpType.Ry]and CNOTs [23]) and an initial number of layers (L=2-5). b. Parameter Initialization: Initialize the parameter vector ( \vec{\theta} ) randomly or based on a heuristic strategy.Hybrid Optimization Loop: a. Quantum Execution: On the quantum processor, prepare the state ( |\Psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle ) by executing the parameterized HEA circuit. b. Measurement: Measure the expectation values of the individual Pauli terms that constitute the Hamiltonian ( H ). This often requires measurements in multiple bases (X, Y, Z) or advanced techniques to reduce the measurement budget [2]. c. Energy Estimation: Classically compute the total energy expectation value ( E(\vec{\theta}) ) by summing the measured expectation values of the Hamiltonian terms. d. Classical Optimization: A classical optimizer (e.g., BFGS, COBYLA, SPSA) proposes a new set of parameters ( \vec{\theta}' ) to minimize ( E(\vec{\theta}) ). e. Convergence Check: Steps a-d are repeated until the energy converges within a predefined threshold or a maximum number of iterations is reached.

The following workflow diagram details the steps and interactions in this protocol.

Figure 2: Workflow for a Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) experiment using a Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA), illustrating the hybrid quantum-classical optimization loop.

Advanced Protocol: Optimized Sampled Quantum Diagonalization (SQDOpt)

Principle: The SQDOpt algorithm addresses the high measurement cost of VQE by combining classical diagonalization techniques with quantum measurements to optimize the ansatz [2].

Procedure:

- State Preparation and Sampling: Prepare a variational state ( |\Psi\rangle ) (e.g., using a HEA) on the quantum hardware. Measure the state in the computational basis ( N_s ) times to obtain a set of bitstrings ( \widetilde{\mathcal{X}} ) representing electronic configurations.

- Subspace Formation: From ( \widetilde{\mathcal{X}} ), randomly form ( K ) batches (subspaces) ( \mathcal{S}^{(1)}, \ldots, \mathcal{S}^{(K)} ), each containing ( d ) configurations.

- Quantum Subspace Diagonalization: For each batch ( \mathcal{S}^{(k)} ): a. Construct the projected Hamiltonian matrix ( H_{\mathcal{S}^{(k)}} ) within the subspace. b. Classically diagonalize this small matrix to find the lowest eigenvalue ( E^{(k)} ) and the corresponding eigenvector.

- Parameter Update: Use the information from the subspace diagonalizations (e.g., via a classical optimizer like Davidson's method) to update the parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) of the HEA.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 1-4 until the energy converges. The final, optimized ansatz can be evaluated once with high precision to obtain the solution [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This section catalogs the critical "research reagents" – the fundamental software and hardware components – required for experimental work with HEAs in quantum chemistry.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for HEA Experiments in Quantum Chemistry

| Research Reagent | Type | Function / Purpose | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Gate Set | Hardware | The physical operations available on a quantum processor; using them minimizes circuit depth and error. | Single-qubit rotations (Rx, Ry, R_z); Two-qubit entanglers (CNOT, CZ, √iSWAP) [23] [22]. |

| Parameterized Quantum Circuit (PQC) | Software | The abstract representation of the HEA, defining its structure and parameters. | A sequence of layers with alternating rotation and entanglement blocks [23]. |

| Fermion-to-Qubit Mapper | Software | Translates the electronic structure Hamiltonian of a molecule into a form operable on a qubit register. | Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev, or parity encoding modules in quantum chemistry libraries (e.g., InQuanto [23]). |

| Classical Optimizer | Software | The algorithm that navigates the parameter landscape to minimize the energy. | Gradient-based (e.g., SPSA, natural gradient) or gradient-free (e.g., COBYLA, BFGS) optimizers [2]. |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Software & Hardware | A suite of methods to reduce the impact of noise on measurement results without quantum error correction. | Zero-noise extrapolation, probabilistic error cancellation, and readout error mitigation [1]. |

| Quantum Hardware with Linear Connectivity | Hardware | A processor whose qubit connectivity allows nearest-neighbor interactions in a 1D chain; sufficient for many HEA architectures. | Superconducting qubit processors (e.g., IBM Cleveland) or ion-trap systems [2] [21]. |

| PDE5-IN-9 | 2-(Pyridin-3-yl)-N-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)quinazolin-4-amine | CAS 157862-84-5. High-purity 2-(Pyridin-3-yl)-N-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)quinazolin-4-amine for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Genistein | Bench Chemicals |

Hardware-Efficient Ansatzes represent a critical tool for leveraging current NISQ devices for quantum chemistry applications. The layered architecture, built from native single-qubit rotations and two-qubit entangling gates, provides a practical balance between expressibility and resilience to noise. The experimental protocols outlined—from the standard VQE approach to the more advanced SQDOpt method—provide a clear roadmap for researchers to implement these techniques. Future work will focus on further integrating physical constraints like size-consistency and developing dynamic ansatz architectures to systematically tackle larger molecular systems of interest in drug discovery.

Advanced Ansatz Methodologies and Practical Chemical Applications

Sampled Quantum Diagonalization (SQD) represents a paradigm shift in quantum algorithms for ground-state energy calculation, moving beyond the variational approach of the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE). While VQE has been the dominant method for quantum chemistry simulations on near-term devices, it faces significant challenges including optimization difficulties in high-dimensional, noisy landscapes and the problem of shallow local minima that lead to over-parameterized ansätze [24] [25]. SQD addresses these limitations by using the quantum computer as a sampling engine that generates a subspace in which the Hamiltonian is classically diagonalized [26].

The fundamental innovation of SQD lies in its hybrid approach: rather than optimizing parameters variationally, SQD collects samples from quantum circuits to construct a reduced Hamiltonian matrix, which is then diagonalized classically to obtain energy eigenvalues. This method offers provable convergence guarantees under specific conditions, particularly when the ground-state wave function is concentrated (has support on a small subset of the full Hilbert space) [26]. For the quantum chemistry community, this translates to more reliable simulations of molecular systems, while for drug development researchers, it offers a potentially more robust pathway to accurate molecular property predictions on emerging quantum hardware.

SQD Methodological Framework and Variants

Core SQD Algorithm

Sample-based Quantum Diagonalization employs quantum computers to generate a set of states that span a subspace containing approximations to the desired eigenstates. The algorithm proceeds through these key steps:

- State Preparation: Generate a set of quantum states ({|\psi_i\rangle}) using parameterized quantum circuits.

- Sampling Measurement: Measure the matrix elements (H{ij} = \langle\psii|H|\psij\rangle) and (S{ij} = \langle\psii|\psij\rangle) through quantum sampling.

- Classical Diagonalization: Solve the generalized eigenvalue problem (H\mathbf{c} = ES\mathbf{c}) on a classical computer.

- State Reconstruction: Construct the approximate eigenstate as (|\Psi\rangle = \sumi ci |\psi_i\rangle).

This approach differs fundamentally from VQE, as it circumvents the challenging parameter optimization landscape by leveraging classical computational resources for the diagonalization step [26].

Key SQD Variants and Their Applications

Several optimized variants of SQD have emerged to address specific implementation challenges:

Sample-based Krylov Quantum Diagonalization (SKQD): This variant uses quantum Krylov states generated through real or imaginary time evolution as the basis for the subspace. SKQD provides formal convergence guarantees similar to quantum phase estimation when the ground state is well-concentrated in the generated subspace [26].

SqDRIFT: This innovative variant combines SKQD with the qDRIFT randomized compilation protocol for the Hamiltonian propagator, making it particularly suitable for the utility scale on chemical Hamiltonians. By preserving convergence guarantees while reducing circuit depth requirements, SqDRIFT enables SQD calculations on molecular systems beyond the reach of exact diagonalization [26].

Overlap-ADAPT-VQE: While not strictly an SQD method, this related approach addresses similar challenges by growing ansätze through overlap maximization with target wave-functions rather than energy minimization. This strategy produces ultra-compact ansätze that avoid local minima, reducing circuit depth requirements significantly—a critical advantage for noisy hardware [24].

Table 1: Comparison of Key SQD Variants and Their Characteristics

| Variant | Key Innovation | Convergence Guarantees | Circuit Depth Requirements | Ideal Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic SQD | Classical diagonalization of quantum-sampled subspace | Dependent on state preparation | Moderate | Medium-sized molecules with concentrated ground states |

| SKQD | Krylov subspace generation | Similar to QPE under concentration assumptions | High (time evolution circuits) | Strongly correlated systems |

| SqDRIFT | Randomized compilation of propagators | Preserves SKQD guarantees | Reduced via randomization | Large systems on noisy devices |

| Overlap-ADAPT-VQE | Overlap-guided compact ansätze | Systematic through adaptive process | Significantly reduced | Strongly correlated systems on NISQ devices |

Hardware-Efficient Implementation for Noisy Quantum Chemistry

Circuit Depth Optimization Strategies

Implementing quantum chemistry algorithms on current NISQ devices requires careful attention to circuit depth constraints dictated by qubit coherence times and gate fidelity limitations. Several strategies have emerged to address these challenges:

The SqDRIFT algorithm employs randomized compilation to implement time evolution operators with reduced circuit depth. By breaking down the time evolution into a random product of unitary operations, SqDRIFT achieves a more favorable trade-off between circuit depth and accuracy, enabling utility-scale quantum chemistry calculations on existing hardware [26].

The Overlap-ADAPT-VQE approach demonstrates that compact ansätze can be constructed by maximizing overlap with target wave-functions rather than navigating the complex energy landscape. This method has shown particularly strong performance for strongly correlated systems, producing chemically accurate results with substantially fewer CNOT gates compared to standard ADAPT-VQE—in some cases reducing gate counts from over 1000 to more manageable depths for NISQ devices [24].

Noise Resilience Techniques

Quantum algorithms for realistic chemical systems must contend with various noise sources, including decoherence, gate errors, and measurement inaccuracies. Recent research has identified several optimization strategies that maintain performance under noisy conditions:

Statistical benchmarking of optimization methods for VQE under quantum noise has demonstrated that the BFGS optimizer consistently achieves the most accurate energies with minimal evaluations, maintaining robustness even under moderate decoherence. For low-cost approximations, COBYLA performs well, while global approaches such as iSOMA show potential despite higher computational costs [25].

The Overlap-ADAPT-VQE method demonstrates inherent noise resilience by constructing shorter circuits that reduce the cumulative impact of gate errors and decoherence. By avoiding the deep circuits associated with traversing energy plateaus in standard adaptive approaches, this method maintains higher fidelity on noisy processors [24].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

SqDRIFT Implementation Protocol

The following detailed protocol enables implementation of the SqDRIFT algorithm for molecular systems:

Step 1: Molecular System Setup

- Define molecular geometry (atomic symbols and coordinates)

- Select basis set (e.g., STO-3G for initial testing, cc-pVDZ for higher accuracy)

- Compute molecular Hamiltonian using quantum chemistry packages (OpenFermion-PySCF)

Step 2: Randomized Compilation Parameters

- Set evolution time steps for Krylov generation

- Determine qDRIFT protocol parameters (number of fragments, compilation strategy)

- Configure sampling parameters for measurement

Step 3: Quantum Circuit Generation

- Implement randomized compilation of time evolution operators

- Generate quantum Krylov states through parameterized circuits

- Apply measurement protocols for subspace matrix elements

Step 4: Classical Processing

- Construct subspace Hamiltonian (H) and overlap (S) matrices from measurements

- Solve generalized eigenvalue problem Hc = ESc classically

- Extract ground state energy and wavefunction approximation

This protocol has been successfully applied to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, demonstrating scalability to system sizes beyond the reach of exact diagonalization [26].

Performance Benchmarking Methodology

Rigorous benchmarking of quantum algorithms requires standardized methodologies:

Convergence Metrics:

- Track energy error versus exact diagonalization (when available)

- Monitor wavefunction fidelity or overlap with reference

- Assess convergence rate versus circuit depth/number of parameters

Resource Analysis:

- Count total number of quantum gates (particularly CNOT gates)

- Estimate total measurement requirements based on operator pool size

- Calculate classical computation costs for diagonalization

Noise Resilience Testing:

- Test under various noise models (phase damping, depolarizing, thermal relaxation)

- Evaluate performance degradation with increasing noise intensity

- Compare optimization trajectories across different noise conditions [25]

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for SQD Implementation

| Reagent Category | Specific Tools | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Software | PennyLane with adaptive modules | Circuit construction & optimization | Supports adaptive operator selection and gradient calculations [27] |

| Classical Integrators | OpenFermion-PySCF | Molecular integral computation | Provides Hamiltonian generation and second quantization mapping [24] |

| Optimization Libraries | SciPy (BFGS, COBYLA) | Parameter optimization | BFGS shows best noise resilience; COBYLA for derivative-free optimization [25] |

| Error Mitigation | qDRIFT randomized compilation | Circuit depth reduction | Enables feasible time evolution for complex molecular Hamiltonians [26] |

| Operator Pools | Restricted single/double excitations | Ansatz construction space | Balancing expressibility and computational tractability [24] |

Application to Molecular Systems

Performance on Benchmark Molecules

SQD methods have demonstrated particular effectiveness on specific molecular systems:

For the Hâ‚‚ molecule at equilibrium geometry, SQD variants achieve chemical accuracy with reduced quantum resource requirements compared to traditional VQE approaches. The algorithm successfully captures the electronic correlation essential for accurate bond energy prediction [25].

In strongly correlated systems such as stretched H₆ linear chains and BeH₂ molecules, the Overlap-ADAPT approach produces chemically accurate ansätze with significantly improved compactness compared to standard ADAPT-VQE. Where standard ADAPT-VQE required over 1000 CNOT gates for chemical accuracy, the overlap-guided approach achieved similar accuracy with substantially reduced gate counts [24].

For polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, the SqDRIFT algorithm enables treatment of system sizes beyond the reach of exact diagonalization, demonstrating scalability to chemically relevant molecules while maintaining provable convergence guarantees [26].

Integration with Classical Methods

A powerful emerging paradigm combines SQD with classical computational methods:

The Overlap-ADAPT-VQE approach can be initialized with accurate Selected-Configuration Interaction (SCI) classical target wave-functions, creating a hybrid pipeline that leverages classical methods for initial approximation and quantum refinement for ultimate accuracy [24].

This integration strategy is particularly valuable for drug development applications, where specific molecular fragments might be treated classically while quantum resources are focused on regions requiring high-accuracy correlation treatment, enabling larger systems to be addressed with limited quantum resources.

Outlook and Research Directions

The development of SQD and its optimized variants represents significant progress toward practical quantum chemistry on quantum hardware. Several promising research directions emerge:

Scalability Enhancements: Future work will focus on extending SQD methods to larger molecular systems with complex electronic structures, particularly those relevant to pharmaceutical applications such as drug-receptor interactions and transition metal complexes.

Error Mitigation Integration: Combining SQD with advanced error mitigation techniques could further extend the applicability of these methods on noisy devices. Techniques such as zero-noise extrapolation and probabilistic error cancellation may enhance performance on existing hardware.

Algorithm Hybridization: Developing tighter integration between classical quantum chemistry methods and SQD approaches will enable more efficient resource utilization, allowing classical methods to handle less correlated regions while quantum resources focus on strongly correlated active spaces.

Hardware-Specific Optimizations: As quantum processor architectures diversify, developing SQD variants optimized for specific hardware characteristics (connectivity, native gate sets, coherence properties) will be essential for maximizing performance.

For researchers in drug development and quantum chemistry, SQD and its variants offer a promising pathway toward practical quantum advantage in molecular simulations, potentially enabling accurate prediction of molecular properties, reaction mechanisms, and binding affinities that remain challenging for classical computational methods.

The application of machine learning (ML) in quantum chemistry represents a paradigm shift, offering solutions to long-standing computational bottlenecks. Within noisy quantum simulation, a primary challenge is the classical optimization of parameterized quantum circuits, such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), which is often hampered by excessive local minima and the barren plateau phenomenon [28] [29]. This creates a critical need for hardware-efficient ansatz designs and methods to rapidly initialize their parameters.

Transferable parameter prediction addresses this by using ML models to predict optimal quantum circuit parameters directly from molecular structure, bypassing expensive iterative optimization [28]. This Application Note details the integration of two powerful neural architectures for this task: the Graph Attention Network (GAT) and the SchNet model. GATs excel at processing graph-structured data by leveraging attention mechanisms to weight the importance of neighboring nodes [30] [31], making them ideal for molecular graphs where atoms and bonds form natural nodes and edges. In parallel, SchNet is a specialized graph neural network that incorporates translational and rotational invariance by design, using continuous-filter convolutional layers to model quantum interactions directly from atomic coordinates and types [32]. We demonstrate protocols for applying these models to predict parameters for quantum chemistry simulations, enabling accurate and transferable learning across molecular sizes and configurations.

Key Architectures and Comparative Performance

The table below summarizes the core attributes and demonstrated performance of GAT and SchNet in relevant scientific applications.

Table 1: Architecture and Performance Comparison of GAT and SchNet

| Feature | Graph Attention Network (GAT) | SchNet |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Self-attention mechanism on graph nodes; assigns varying importance to neighbors [31] | Continuous-filter convolutional layers; encodes quantum interactions and invariances [32] |

| Primary Input | Molecular graph (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) [33] | Atomic Cartesian coordinates and atom types [32] |

| Key Strength | Captures local molecular structure and bond relationships effectively [33] | Built-in rotational and translational invariance; directly models quantum mechanical effects [32] |

| Demonstrated Quantum Application | Predicting VQE parameters for hydrogenic systems (Hâ‚„ to Hâ‚â‚‚) [28] | Representing solvation free energy as a many-body potential; learning potentials for molecular dynamics [32] |

| Reported Performance (Example) | Model trained on Hâ‚„ showed transferability to predict parameters for larger Hâ‚â‚‚ systems [28] | Solvation free energy predictions significantly more accurate than state-of-the-art implicit solvent models like GBn2 [32] |

| Hardware Acceleration | FPGA-based accelerators (H-GAT, SH-GAT) demonstrate massive speedups over CPU/GPU [30] [34] | High expressibility for capturing many-body effects, enabling accurate coarse-grained force fields [32] |

Successful implementation of the protocols described in this note relies on several key software and data resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| quanti-gin | A specialized library for generating datasets containing molecular geometries, Hamiltonians, and corresponding optimized quantum circuit parameters [28]. | Used in generating 230,000 linear H4 instances for training [28]. |

| Tequila | A quantum computing library used for constructing and executing variational quantum algorithms, including VQE [28]. | Employed in the data generation workflow for quantum circuit ansatz and VQE minimization [28]. |

| DeepChem | An open-source toolkit that provides a wide array of molecular datasets and ML models for drug discovery and quantum chemistry [33]. | Provides access to MoleculeNet benchmark datasets [33]. |

| MoleculeNet | A benchmark collection of molecular datasets for evaluating ML algorithms on chemical tasks [33]. | Includes datasets like BBBP, Tox21, ESOL, and Lipophilicity [33]. |

| FPGA Accelerators (e.g., H-GAT, SH-GAT) | Specialized hardware platforms that offer highly efficient and power-effective inference for graph neural networks like GAT [30] [34]. | SH-GAT achieved a 3283x speedup over CPU and 13x over GPU on GAT inference [34]. |

Experimental Protocols for Transferable Parameter Prediction

Protocol 1: GAT for Predicting VQE Parameters in Hydrogenic Systems

This protocol outlines the procedure from [28] for training a GAT model to predict parameters for the Separable Pair Ansatz (SPA) quantum circuit.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Generation:

- Molecular Configurations: Generate a large set of molecular geometries for training. For example, create 230,000 instances of linear H4 molecules and 2,000 random H6 instances. The atomic coordinates should be constrained, placing each new atom 0.5 to 2.5 Ã… from an existing atom to prevent dissociation or clustering [28].

- Circuit Ansatz and VQE Optimization: For each geometry:

- Estimate the optimal chemical graph (e.g., a perfect matching graph with minimal edge weight based on Euclidean distances).

- Construct the SPA circuit ansatz using this graph and compute the corresponding orbital-optimized Hamiltonian,

H_opt. - Execute a full VQE to minimize the expectation value

⟨U_SPA| H_opt | U_SPA⟩and obtain the optimized energyE_SPAand the corresponding optimal parametersθ[28].

- Data Storage: Store each instance as a tuple

(C, H, G, E_SPA, θ), whereCis the coordinate set,His the Hamiltonian,Gis the graph, andθare the target parameters.

Graph Construction:

- Represent each molecule as a graph where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges.

- Node features can include atom type, charge, etc. The input preprocessing for the GAT model can use a Euclidean distance matrix with angles to encode spatial relationships [28].

GAT Model Training:

- Train a GAT model where the input is the molecular graph and the output is a vector of predicted circuit parameters.

- The model learns a mapping

f_GAT(G) → θ_predicted. The training objective is to minimize the difference (e.g., Mean Squared Error) betweenθ_predictedand the true, VQE-optimized parametersθfrom the dataset [28].

Parameter Prediction and VQE Initialization:

- For a new, unseen molecule, generate its graph and feed it into the trained GAT model.

- Use the output

θ_predictedas the initial parameter set for a VQE procedure, replacing a random initialization.

Performance Evaluation:

- Evaluate the success of the protocol by comparing:

- The number of VQE optimization steps required to converge when initialized with GAT-predicted parameters versus random initialization.

- The final energy accuracy achieved.

- Critically, assess the model's transferability by testing a model trained on small molecules (e.g., H4) on significantly larger instances (e.g., H12) [28].

- Evaluate the success of the protocol by comparing:

Protocol 2: SchNet for Learning Molecular Representations and Potentials

This protocol, derived from [32], describes using SchNet to learn a complex quantum chemical property—the solvation free energy—which is analogous to learning a potential energy surface for quantum circuits.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Collection:

- Gather a large set of molecular configurations from explicit solvent atomistic simulations. For example, use 600,000 atomistic configurations across multiple proteins (e.g., CLN025, Trp-cage, BBA) [32].

- For each configuration, compute the target property using a high-fidelity method. In the referenced study, the solvation free energy

E_GBn2was computed using the GB-neck2 (GBn2) implicit solvent model to create the training dataset [32].

Featurization and Model Input:

- Abstract the molecule into a graph where nodes are atoms.

- Inputs for each atom are typically its type (embedded as a vector) and its Cartesian coordinates in 3D space [32].

- Define edges in the graph based on a cutoff distance (e.g., 1.8 nm to 5.0 nm) to capture both covalent and noncovalent interactions [32].

SchNet Architecture Forward Pass:

- Embedding Layer: An initial featurization is assigned to each atom based on its type.

- Interaction Blocks (Message Passing): A series of interaction blocks update the atomic feature vectors. Crucially, these updates incorporate information from neighboring atoms within the cutoff distance, using continuous-filter convolutions that depend on interatomic distances. This step is repeated over multiple blocks (e.g., 2 to 6) to capture many-body effects [32].

- Energy Prediction: The updated feature vectors are passed through a feed-forward neural network to predict an atomic energy contribution. These are summed to produce the total energy for the molecular configuration [32].

Loss Calculation and Optimization:

- The model is trained by minimizing the difference between its predicted energy and the target energy (e.g.,

E_GBn2). The loss function is often a root-mean-squared error (RMSE) [32]. - For force field optimization, the potential contrasting method can be used. This method optimizes the overlap between the configurational distribution of the coarse-grained model (SchNet) and the reference atomistic data, ensuring thermodynamic consistency [32].

- The model is trained by minimizing the difference between its predicted energy and the target energy (e.g.,

Simulation and Free Energy Validation:

- The trained SchNet model can be used to perform molecular dynamics simulations by calculating forces via backpropagation.

- Validate the model's physical accuracy by computing free energy profiles (e.g., as a function of RMSD from a folded state) using methods like free energy perturbation with reweighting. Compare these profiles to those from reference simulations to confirm the model has learned a physically meaningful representation [32].

Discussion and Outlook

The integration of GATs and SchNets provides a powerful, complementary toolkit for advancing hardware-efficient ansatz design in quantum chemistry. GATs offer a direct path to transferable parameter prediction, demonstrably initializing VQE parameters for molecules larger than those seen in training [28]. SchNet provides a robust framework for learning fundamental molecular representations and potentials that respect physical symmetries, leading to highly accurate and transferable force fields [32].

The future of this interdisciplinary field is bright. Promising directions include the development of hybrid models that combine the strengths of GAT's attention mechanisms with SchNet's inherent physical invariances. Furthermore, the emergence of dedicated FPGA-based hardware accelerators for GNNs [30] [34] will dramatically reduce the computational overhead of model inference, making these ML-guided quantum simulations more practical and scalable. Finally, the principles of Geometric Quantum Machine Learning (GQML) [29]—building models that explicitly encode problem symmetries—will be crucial for developing next-generation, highly trainable, and data-efficient models for quantum chemistry.