Harnessing Symmetry Protection to Overcome Quantum Noise in Computational Chemistry for Drug Discovery

This article explores the critical role of symmetry-protected subspaces in mitigating the effects of quantum noise for practical quantum computational chemistry.

Harnessing Symmetry Protection to Overcome Quantum Noise in Computational Chemistry for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of symmetry-protected subspaces in mitigating the effects of quantum noise for practical quantum computational chemistry. As quantum computing emerges as a transformative tool for pharmaceutical research, enabling precise simulations of molecular interactions and drug-target binding, hardware limitations and environmental noise present significant obstacles. We provide a comprehensive analysis, from foundational concepts of symmetry in quantum systems to methodological applications in real-world drug design workflows like covalent inhibitor simulation and prodrug activation profiling. The article further details troubleshooting strategies for noise-induced symmetry breaking and presents comparative validation of quantum-classical hybrid approaches. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage near-term quantum hardware for more accurate and efficient molecular modeling.

Quantum Symmetry and Noise: Foundational Concepts for Robust Chemical Simulations

Theoretical Foundations and Significance

In quantum mechanics, a Symmetry-Protected Subspace (SPS) is a portion of a quantum system's Hilbert space that remains invariant under time evolution due to the presence of underlying symmetries in the system's Hamiltonian. These symmetries imply conservation laws, which effectively partition the entire Hilbert space into invariant subspaces, each demarcated according to its specific conserved quantity [1]. The discovery and utilization of these subspaces are of utmost theoretical importance with valuable applications across various quantum simulations and experimental settings.

The fundamental principle underlying SPS is that physical symmetries give rise to conserved quantities. When a quantum system possesses a symmetry—meaning its Hamiltonian commutes with the symmetry operator—the Hilbert space decomposes into subspaces characterized by different eigenvalues of the symmetry operator. Once a quantum state is prepared within one of these subspaces, it remains confined to that subspace throughout its evolution, protected from errors or noise that would otherwise drive it into other portions of the Hilbert space. This inherent protection mechanism makes SPS particularly valuable in the context of noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, where error mitigation is crucial for obtaining meaningful computational results [1] [2].

The mathematical foundation of SPS connects to Noether's theorem, which establishes the relationship between continuous symmetries and conservation laws in physics [3]. In quantum computing and quantum simulation, this relationship becomes practically exploitable for protecting quantum information against specific types of errors and decoherence processes. For researchers in computational chemistry and drug development, understanding SPS provides critical insights into designing more robust quantum simulations of molecular systems, potentially leading to more accurate predictions of molecular properties and reaction pathways.

Automated Detection and Computational Methods

Algorithmic Approaches for SPS Identification

Identifying symmetry-protected subspaces traditionally required explicit knowledge of the symmetry operators and their eigenvalues, which can be computationally demanding and theoretically challenging. Recent advances have introduced classical algorithms that efficiently detect these subspaces without explicitly identifying the underlying symmetry operator [1]. These methods rely on graph-theoretic approaches applied to state-to-state transitions under k-local unitary operations:

Transitive Closure on State Graphs: The first algorithm constructs a graph where nodes represent computational basis states and edges represent possible transitions under local unitary operations. The symmetry-protected subspaces correspond to connected components obtained through transitive closure on this graph [1].

Linear Time Complexity: This approach explores the entire symmetry-protected subspace of an initial state with time complexity linear to the size of the subspace, making it computationally feasible for practical applications [1].

Measurement Validation: The second algorithm determines, with bounded error, whether a specific measurement outcome of a dynamically-generated state resides within the symmetry-protected subspace of the initial state [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Automated SPS Detection Algorithms

| Algorithm Feature | Transitive Closure Approach | Measurement Validation Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Time Complexity | Linear in subspace size | Constant or sublinear with bounded error |

| Primary Function | Map entire SPS structure | Verify subspace membership |

| Symmetry Knowledge | Not required | Not required |

| Key Advantage | Comprehensive subspace exploration | Efficient for specific states |

| Application Context | Quantum simulation analysis | Quantum error mitigation |

These algorithms have been successfully demonstrated on several quantum dynamical systems, including the Heisenberg-XXX model and quantum cellular automata (T₆ and F₄), showing particular utility for post-selecting quantum computer data and optimizing classical simulations of quantum systems [1].

Workflow for SPS Identification

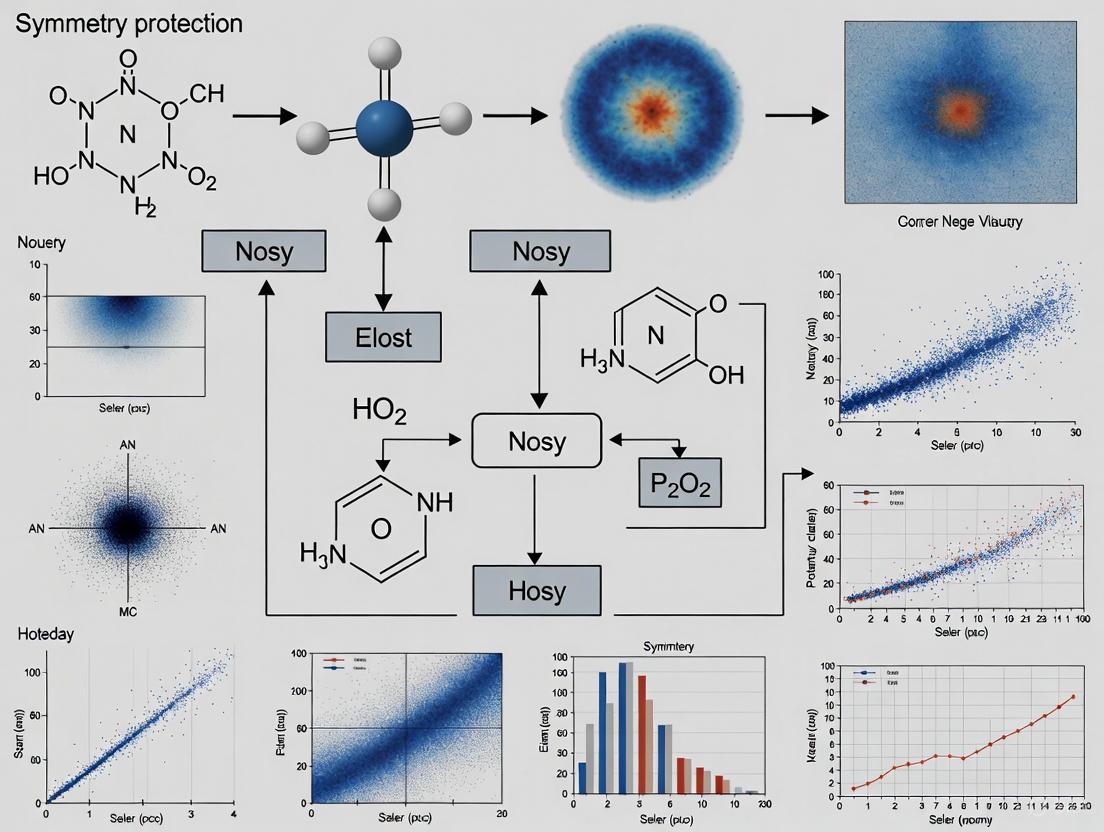

The following diagram illustrates the complete automated workflow for detecting symmetry-protected subspaces in quantum simulations:

Applications in Noisy Quantum Computational Chemistry

Error Mitigation in Quantum Chemistry Simulations

In the NISQ era, quantum computations are severely limited by hardware errors and decoherence. SPS provides a powerful approach to mitigate these effects in computational chemistry applications. By constraining quantum simulations to symmetry-protected subspaces, researchers can effectively filter out errors that violate the inherent symmetries of the molecular system being simulated [1] [2].

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm, widely used for molecular energy calculations, particularly benefits from symmetry protection. When simulating molecular systems, symmetries such as particle number conservation, spin conservation, and point group symmetries naturally emerge. These symmetries can be exploited to define protected subspaces that shield the computation from various error sources [4] [2].

Experimental demonstrations have validated this approach. For instance, implementing symmetry verification in VQE simulations has shown significant improvements in energy estimation accuracy for small molecules [2] [3]. The essential methodology involves:

- Identifying relevant symmetries in the molecular Hamiltonian

- Constructing measurement protocols to verify these symmetries

- Post-selecting measurement outcomes that respect the symmetry constraints

- Discarding results that violate symmetry conservation laws

This symmetry verification process effectively projects noisy quantum states back into the correct symmetry sector, dramatically improving the fidelity of quantum simulations without additional physical qubits or quantum error correction [3].

Chemical Reaction Modeling on NISQ Devices

Recent advances have demonstrated the practical utility of symmetry-protected approaches for accurate chemical reaction modeling on current quantum hardware. One notable protocol combines correlation energy-based active orbital selection with effective Hamiltonians from driven similarity renormalization group (DSRG) methods and noise-resilient wavefunction ansatzes [4].

This integrated approach has been successfully applied to model a Diels-Alder reaction—a fundamental transformation in organic chemistry with significant pharmaceutical relevance—on a cloud-based superconducting quantum computer [4]. The protocol achieved chemical accuracy despite hardware limitations by leveraging:

- Automatic orbital selection based on orbital correlation energy contributions

- Effective Hamiltonians that capture essential electron correlations within reduced active spaces

- Hardware-adaptable ansatzes resilient to device-specific noise patterns

Table 2: Quantum Computational Chemistry Methods Leveraging Symmetry

| Method Component | Role of Symmetry | Impact on Simulation Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Active Space Selection | Identifies orbitals with significant correlation energy | Reduces qubit requirements while preserving accuracy |

| DSRG Effective Hamiltonian | Preserves symmetry properties in downfolding | Maintains physical consistency in reduced models |

| Hardware Adaptable Ansatz | Respects symmetry constraints in circuit design | Improves noise resilience and state preparation |

| Symmetry Verification | Projects out symmetry-breaking errors | Enhances result fidelity without extra qubits |

| VQE Optimization | Constrains search to physical symmetry sector | Accelerates convergence and avoids unphysical states |

The successful implementation of this protocol represents a significant milestone in realizing quantum utility for computational chemistry, demonstrating that chemically accurate simulations are possible on existing quantum hardware when appropriate symmetry-aware techniques are employed [4].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for SPS Experiments in Quantum Chemistry

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in SPS Research |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithmic Frameworks | Transitive closure algorithms, ADAPT-VQE | Detect SPS and optimize ansatz structures |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Zero-noise extrapolation, symmetry verification | Counteract hardware noise using symmetry |

| Classical Simulators | Qiskit, Cirq, PennyLane | Test and validate SPS approaches before hardware deployment |

| Quantum Hardware Platforms | Superconducting (Quantinuum), neutral atom (QuEra) | Experimental validation of SPS methods |

| Molecular Modeling Tools | DSRG, unitary coupled cluster | Prepare effective Hamiltonians with preserved symmetries |

| Analysis Methods | Quantum state tomography, entanglement entropy | Verify symmetry protection and subspace confinement |

Detailed Protocol for Symmetry Verification in VQE

The following workflow details the experimental protocol for implementing symmetry verification in variational quantum eigensolver calculations for quantum computational chemistry:

Step-by-Step Implementation Guide:

Hamiltonian Preparation: Begin with the molecular electronic structure problem and transform it into a qubit Hamiltonian using encoding schemes such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev that preserve relevant symmetries [2].

Symmetry Identification: Identify all conserved quantities in the Hamiltonian, including particle number, total spin, and point group symmetries. Construct the corresponding symmetry operators in the qubit representation [1] [2].

Ansatz Design: Develop a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) that respects the identified symmetries. This ensures that all states generated during the VQE optimization remain within the correct symmetry sector [4] [2].

Circuit Execution: For each set of parameters during the optimization loop, execute the quantum circuit and simultaneously measure both the energy and symmetry operators [2] [3].

Symmetry Verification: Post-select measurement outcomes where the symmetry operators return the expected eigenvalues. Discard results that violate symmetry conservation, as these likely stem from hardware errors [1] [3].

Energy Estimation: Compute the energy expectation value using only the post-selected measurement outcomes. This provides a more accurate estimate of the true ground state energy [2] [3].

Parameter Update: Use a classical optimizer (COBYLA or BFGS) to adjust the circuit parameters based on the verified energy estimate, iterating until convergence [2].

This protocol has been experimentally validated in simulations of sodium hydride (NaH) and other small molecules, demonstrating significant improvements in energy accuracy compared to unmitigated approaches [2].

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The integration of symmetry-protected subspaces into quantum computational chemistry represents a rapidly advancing frontier with several promising research directions:

Machine Learning for Symmetry Discovery: Recent work has explored using deep learning techniques to automatically discover hidden symmetries in quantum systems [3]. These approaches could complement algorithmic SPS detection methods, potentially identifying non-obvious symmetries that provide additional protection for quantum simulations.

Advanced Error Mitigation Protocols: Combining symmetry verification with other error mitigation techniques such as zero-noise extrapolation and probabilistic error cancellation offers a multi-layered defense against hardware imperfections [2] [3]. Research is needed to optimize these hybrid approaches for specific chemical applications.

Drug Discovery Applications: For pharmaceutical researchers, symmetry principles extend beyond quantum simulation to molecular design itself. Many biological targets, including homotrimeric proteins like the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, exhibit inherent C3 symmetry that can be exploited in drug design [5]. Quantum simulations leveraging SPS could accelerate the discovery of symmetric ligands optimized for these targets.

Scalability to Larger Systems: Current demonstrations have focused on small molecules, but extending these approaches to pharmacologically relevant systems requires developing scalable SPS identification methods that remain efficient for larger active spaces and more complex symmetries [4].

As quantum hardware continues to advance, symmetry-protected approaches will play an increasingly vital role in bridging the gap between theoretical quantum advantage and practical applications in computational chemistry and drug discovery.

The Fundamental Challenge of Quantum Noise in Near-Term Hardware

Quantum noise presents the most significant barrier to realizing practical quantum computing, particularly for computational chemistry applications promising to revolutionize drug discovery and materials science. Near-term quantum hardware, or Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, operate without comprehensive error correction, making their computational outputs inherently unreliable. For quantum computational chemistry, where predicting molecular properties requires precision down to chemical accuracy (approximately 1.6 × 10−3 Hartree), this noise challenge becomes paramount. The fundamental thesis of this work posits that strategically exploiting symmetry—a profound property rooted in physical conservation laws—provides a powerful framework for protecting quantum information against noise, thereby extending the computational capabilities of existing hardware. This whitepaper synthesizes recent experimental advances to provide researchers with practical methodologies for noise characterization and mitigation, with particular emphasis on symmetry-protected approaches relevant to chemical simulation.

Understanding the Quantum Noise Landscape

Quantum noise in modern hardware manifests through multiple channels, each with distinct characteristics and impacts on computation. A comprehensive understanding requires moving beyond simplistic noise models to those reflecting realistic device behavior.

Beyond Depolarizing Noise: The Nonunital Noise Resource

The conventional theoretical framework has largely assumed unital noise models, where errors randomly scramble qubit states without directional preference—analogous to cream evenly mixing throughout coffee [6]. However, IBM Quantum researchers have recently demonstrated that real hardware often exhibits nonunital noise, which has a directional bias that can paradoxically be harnessed as a computational resource [6]. Unlike depolarizing channels that inevitably drive circuits toward randomness, nonunital noise (such as amplitude damping) pushes qubits toward their ground state, creating a natural "cooling" effect. This directional property enables the design of RESET protocols that recycle noisy ancilla qubits into cleaner states, effectively performing measurement-free error correction [6].

Table: Comparison of Quantum Noise Types

| Noise Type | Mathematical Property | Physical Analogy | Impact on Computation | Exploitation Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unital (e.g., depolarizing noise) | Preserves identity operator | Cream stirred evenly in coffee | Rapid loss of coherence; logarithmic depth collapse | Limited; leads to complete decoherence |

| Nonunital (e.g., amplitude damping) | Does not preserve identity | Gravity on spilled marbles | Biased state evolution; directional entropy increase | Harnessable for reset protocols and cooling |

| Colored Noise (time-correlated) | Non-Markovian spectral properties | Musical chord with harmonic structure | Frequency-dependent decoherence | Filterable via dynamical decoupling |

| Readout Noise | Classical assignment errors | Misreading a blurred gauge | Direct measurement inaccuracies | Mitigatable via detector tomography |

Quantitative Noise Impact on Chemical Precision

The stringent precision requirements for quantum chemistry simulations make them particularly vulnerable to noise effects. Recent experiments measuring the BODIPY molecule's energy on IBM Eagle r3 hardware quantified this challenge, demonstrating initial measurement errors of 1-5%—far exceeding the chemical precision threshold of 0.1% (1.6 × 10−3 Hartree) [7]. Through advanced mitigation techniques, researchers achieved a reduction to 0.16% error, approaching but still challenging the required chemical accuracy [7]. These experiments reveal that even for Hartree-Fock states (which require no entangling gates), the complex structure of molecular Hamiltonians makes high-precision measurement nontrivial, with noise effects compounding across the thousands of Pauli terms requiring evaluation.

Experimental Frameworks for Noise Mitigation

RESET Protocols for Nonunital Noise Exploitation

The IBM Quantum team has developed a structured protocol to leverage nonunital noise for error suppression without mid-circuit measurements [6]. This approach transforms a hardware limitation into a computational resource through three stages:

- Passive Cooling: Ancilla qubits are randomized and then exposed to native nonunital noise, which pushes them toward a predictable, partially polarized state.

- Algorithmic Compression: A specialized "compound quantum compressor" circuit concentrates this polarization into a smaller qubit subset, effectively purifying them.

- Swapping: These cleaner qubits replace "dirty" ones in the main computation, refreshing the system.

This RESET protocol enables polylogarithmic overhead in both qubit count and circuit depth, meaning the resource cost increases very slowly even for larger computations [6]. The approach demonstrates that with sufficiently weak and well-characterized nonunital noise, circuits can maintain computational universality and remain challenging for classical simulation—countering the prevailing assumption that noisy devices are limited to shallow circuits.

Diagram: RESET Protocol Workflow for Nonunital Noise Exploitation

High-Precision Measurement via Quantum Detector Tomography

Achieving chemical precision on NISQ devices requires specialized measurement techniques that address both statistical errors and systematic noise biases. Researchers have developed a comprehensive methodology combining several strategies [7]:

- Locally Biased Random Measurements: Reduces shot overhead by prioritizing measurement settings with greater impact on energy estimation while maintaining informational completeness.

- Repeated Settings with Parallel Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): Mitigates readout errors by characterizing the noisy measurement apparatus itself and using this characterization to build unbiased estimators.

- Blended Scheduling: Accounts for time-dependent noise by interleaving different circuit types, ensuring temporal noise fluctuations affect all experiments uniformly.

In practice, this approach enabled the estimation of BODIPY molecular energies with just 70,000 measurement settings repeated 50 times each, achieving a 10-fold error reduction from initial hardware performance [7]. The QDT component is particularly crucial, as it directly addresses the systematic biases introduced by imperfect readout, which often constitute the dominant error source in precision measurements.

Table: Experimental Parameters for High-Precision Molecular Energy Estimation

| Parameter | Implementation in BODIPY Study | Impact on Precision |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement Settings | S = 70,000 | Governs informational completeness of observable estimation |

| Setting Repetitions | T = 50 | Reduces statistical fluctuations in noisy readout |

| Active Space Size | 4e4o to 14e14o (8-28 qubits) | Larger spaces increase Hamiltonian complexity |

| Pauli Terms in Hamiltonian | Consistent across active spaces | Determines measurement circuit variety required |

| Readout Error Mitigation | Parallel Quantum Detector Tomography | Corrects systematic assignment biases |

| Temporal Noise Mitigation | Blended scheduling | Ensures uniform noise exposure across circuits |

Real-Time Noise Characterization via Frequency Binary Search

Addressing time-varying noise requires real-time characterization capabilities that circumvent the latency of external classical processing. An international collaboration has developed the Frequency Binary Search algorithm, implemented directly on field-programmable gate array (FPGA) quantum controllers [8]. This approach enables:

- Direct Qubit Frequency Estimation: The controller estimates qubit frequency fluctuations without data transfer to external computers, avoiding critical time delays.

- Exponential Calibration Efficiency: The algorithm calibrates multiple qubits simultaneously with exponential precision, requiring fewer than 10 measurements compared to thousands in conventional approaches [8].

- Scalable Noise Tracking: The method's efficiency makes it suitable for future systems with millions of qubits, where traditional calibration methods would become prohibitively resource-intensive.

This real-time capability is particularly valuable for maintaining system calibration during lengthy quantum chemistry simulations, where temporal noise drift could otherwise invalidate results obtained over extended measurement periods.

The Symmetry Protection Framework

Fundamental Physics of Symmetry in Quantum Systems

Symmetry principles dating to Emmy Noether's seminal work establish that conserved quantities in physical systems correspond directly to mathematical symmetries [9]. In quantum chemistry, these symmetries govern fundamental behaviors: Pauli exclusion principles dictating electron occupancy, point group symmetries defining molecular orbitals, and spin symmetries determining reaction pathways. The Quantum Paldus Transform (QPT) developed by Quantinuum explicitly leverages these symmetries to create more efficient problem representations on qubits [9]. By transforming complex electronic structure problems into bases that respect inherent symmetries, the QPT "strips the problem down to its bare essentials," discarding unimportant details that otherwise consume valuable quantum resources.

Symmetry-Protected Topological Phases in Noisy Environments

The protective capacity of symmetry extends even to topological phases of matter subjected to environmental noise. Recent research has characterized how symmetry-protected topological (SPT) phases persist under decoherence, with direct implications for measurement-based quantum computation [10]. The computational power of these systems—manifested through gate fidelity in quantum algorithms—serves as a sensitive probe of their topological protection. Key findings include:

- Differential Noise Resilience: SPT phases demonstrate varying robustness depending on whether environmental noises respect the underlying symmetry condition [10].

- String Order Parameters: For the Haldane phase subjected to local decoherence, the fidelity for identity gates correlates with non-local string order parameters, providing a diagnostic for topological protection.

- Enhanced Gate Stability: Gates operating within symmetry-respecting noise environments maintain significantly higher fidelity, enabling reliable computation on otherwise noisy devices.

This connection between symmetry conditions and computational fidelity provides both a diagnostic tool for assessing hardware quality and a design principle for developing noise-resilient quantum algorithms.

Diagram: Symmetry Protection Pathway in Noisy Quantum Computation

Material-Level Noise Suppression through Fabrication

At the hardware level, symmetry principles inform material engineering approaches to intrinsic noise reduction. Researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have developed a novel fabrication technique creating partially suspended superconducting "superinductors" that minimize substrate-induced noise [11]. This approach:

- Reduces Material Defect Interactions: By lifting circuit components from the silicon substrate, the technique minimizes interaction with defect-induced charge fluctuations.

- Enhances Inductive Properties: The suspended structures demonstrated an 87% increase in inductance compared to conventional designs [11].

- Maintains Manufacturing Compatibility: The chemical etching process remains compatible with standard superconducting microchip fabrication.

This material-level noise suppression complements algorithmic symmetry protection, demonstrating how symmetry-informed design operates across multiple abstraction layers to enhance quantum coherence.

Integrated Research Toolkit for Noisy Quantum Chemistry

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Noise-Resilient Quantum Chemistry

| Reagent Category | Specific Implementation | Function in Noise Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Error Characterization Tools | Quantum Detector Tomography | Characterizes readout noise for systematic error correction |

| Symmetry-Aware Compilers | Quantum Paldus Transform | Exploits molecular symmetries for efficient resource encoding |

| Real-Time Control Systems | FPGA with Frequency Binary Search | Enables adaptive noise tracking and compensation |

| Noise-Adaptive Circuits | RESET protocols with nonunital noise | Harnesses native noise properties for active error suppression |

| Precision Measurement | Locally biased classical shadows | Reduces measurement overhead while maintaining precision |

| Hardware Substrates | Suspended superinductor architectures | Minimizes substrate-induced noise at material level |

| Temporal Scheduling | Blended execution protocols | Mitigates time-dependent noise fluctuations |

| YM-53601 free base | YM-53601 free base, CAS:182959-28-0, MF:C21H21FN2O, MW:336.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PXS-5505 | PXS-5505, CAS:2409963-83-1, MF:C13H13FN2O2S, MW:280.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The path forward for practical quantum computational chemistry requires a multi-layered approach to the noise challenge, with symmetry principles providing a unifying framework across abstraction levels. While individual techniques—whether RESET protocols, detector tomography, or the Quantum Paldus Transform—offer significant improvements, their combination creates synergistic protection against the diverse noise sources plaguing NISQ devices. The research community must move beyond generic noise suppression toward application-aware mitigation strategies that exploit problem-specific symmetries, particularly for chemical simulations where molecular symmetries provide natural protection mechanisms. As hardware continues to advance, with improved fabrication techniques and real-time control systems, the integration of these symmetry-protected approaches will enable increasingly accurate molecular simulations, ultimately fulfilling the promise of quantum computing in drug development and materials discovery.

How Noise Acts as a Symmetry-Breaking Field in Quantum Circuits

The pursuit of fault-tolerant quantum computation represents one of the most significant challenges in modern physics. Within quantum circuits, carefully engineered symmetries can protect fragile quantum information from decoherence, creating resilient topological phases with inherent error-suppressing properties. However, the very environments designed to shield these quantum systems inevitably introduce noise that can fundamentally alter their symmetry-protected characteristics. This article examines the complex dual role of noise in quantum circuits, exploring how dissipative processes can spontaneously break the protective symmetries that enable topological order while simultaneously creating opportunities for novel quantum control strategies.

Recent theoretical and experimental advances have demonstrated that certain symmetry-protected topological (SPT) orders exhibit remarkable robustness against specific classes of environmental dissipation. The $Z2 \times Z2$ SPT order, exemplified by the one-dimensional cluster Hamiltonian, maintains protected edge modes even under Lindbladian dynamics that preserve strong symmetries [12]. This robustness creates a potential pathway for engineering long-lived quantum memory in noisy intermediate-scale quantum devices. However, when noise breaks the underlying symmetries protecting these topological phases, it induces phase transitions that destroy quantum coherence and computational fidelity. Understanding the precise mechanisms through which noise acts as a symmetry-breaking field provides critical insights for developing error-mitigation strategies in quantum computational chemistry and drug development research, where simulating molecular systems requires maintaining quantum coherence throughout complex computational circuits.

Theoretical Framework: Symmetry Protection and Dissipative Mechanisms

Symmetry-Protected Topological Phases in Quantum Circuits

Symmetry-protected topological phases represent distinctive quantum states of matter that cannot be continuously connected to trivial states without either closing the energy gap or breaking the protecting symmetry. In quantum circuits, these phases manifest through exotic boundary phenomena, including topologically protected edge qubits that remain immune to local perturbations. The $ZXZ$ cluster Hamiltonian serves as a paradigmatic model for studying SPT order, hosting localized edge modes protected by a global $Z2 \times Z2$ symmetry [12]. This mathematical structure ensures that quantum information encoded in these edge modes cannot be corrupted by local operations that respect the symmetry, providing a built-in error correction mechanism fundamental to reliable quantum computation.

The protective capacity of SPT orders stems from the precise algebraic relationship between the system's Hamiltonian and its symmetry operators. For the cluster Hamiltonian, the $Z2 \times Z2$ symmetry operations anti-commute with local perturbation terms while commuting with the Hamiltonian itself, creating a topological obstruction that prevents local interactions from mixing the protected ground state manifold. In closed quantum systems, this mathematical structure guarantees the stability of quantum information against symmetric perturbations. However, when quantum circuits interact with their environment, the resulting open system dynamics introduces additional symmetry considerations that determine whether topological protection survives.

Classification of Noise-Induced Symmetry Breaking

Environmental interactions in quantum circuits generate dissipative processes mathematically described by Lindblad operators within the quantum master equation framework. The impact of these processes on symmetry-protected phases depends critically on how the Lindblad operators commute with the system's symmetry operations:

Table: Classification of Noise-Induced Symmetry Breaking

| Symmetry Class | Mathematical Condition | Impact on SPT Order | Edge Mode Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong Symmetry | $[Lμ,G]=0$ for all $Lμ$ and $G∈G$ | SPT order preserved | Edge qubits remain protected |

| Weak Symmetry | $[H,G]=0$ but $[L_μ,G]≠0$ for some $μ$ | SPT order degraded | Edge modes become metastable |

| Broken Symmetry | $[H,G]≠0$ | SPT order destroyed | Edge protection eliminated |

When the Lindblad jump operators $L_μ$ commute with all elements of the symmetry group $G$ (strong symmetry), the dissipative dynamics preserves the SPT phase, maintaining a degenerate steady-state manifold capable of storing quantum information [12]. In contrast, weak symmetry occurs when the Hamiltonian commutes with $G$ but some jump operators do not, leading to the gradual degradation of topological protection while retaining a memory of initial conditions in quantum trajectories. Complete symmetry breaking eliminates topological protection entirely, rendering the system susceptible to rapid decoherence.

The distinction between strong and weak symmetries in open quantum systems has profound implications for quantum error correction. Under strong symmetry conditions, the steady-state manifold consists of non-local logical qubits that remain immune to local errors, effectively creating a naturally error-correcting quantum memory. For Hamiltonian perturbations that preserve the global symmetry, states within this manifold maintain metastability, significantly extending quantum coherence times [12]. This mathematical framework provides the foundation for understanding how specific noise profiles either preserve or disrupt topological order in quantum circuits.

Noise as a Symmetry-Breaking Field: Mechanisms and Consequences

Dynamical Phase Transitions Induced by Persistent Noise

Recent investigations have revealed that non-equilibrium fluctuations driven by persistent noise can spontaneously generate phase separation even in parameter regions where disordered configurations would remain stable at equilibrium. This noise-induced phase separation mechanism represents a fundamental departure from conventional Landau-Ginzburg theory, where phase transitions occur through spontaneous symmetry breaking in thermodynamic equilibrium [13]. In active field theories driven by persistent noise, the breaking of time-reversal symmetry becomes concentrated at phase boundaries, creating dynamically sustained domain structures that would otherwise be unstable.

The measurement of local entropy production rate provides a quantitative metric for characterizing time-reversal symmetry breaking in these non-equilibrium quantum systems. Research has demonstrated that entropy production intensifies at interfaces between topological and trivial regions, highlighting how dissipative processes actively maintain phase separation [13]. This phenomenon shares mathematical similarities with motility-induced phase separation in active matter systems, where persistent motion introduces effective attractive interactions that drive phase segregation without conventional attractive forces.

Metastability and Information Retrieval in Noisy Environments

Under weak symmetry conditions, the localized edge qubits of SPT Hamiltonians are not conserved quantities under Lindbladian evolution. However,å› ä¸ºä»–ä»¬ correspond to weak symmetries, they retain a memory of their initial state at all times within individual quantum trajectories [12]. This persistence enables novel protocols for retrieving quantum information through continuous monitoring of quantum jumps or application of error mitigation techniques that exploit the trajectory-dependent memory of initial conditions.

The development of these retrieval protocols represents a significant advance in quantum error correction, suggesting that even when the average density matrix loses topological protection, individual quantum trajectories can maintain coherence through measurement-based feedback. By leveraging the mathematical structure of weak symmetries, researchers can construct filtering operations that effectively isolate the coherent component of quantum evolution, potentially extending the computational horizon of noisy quantum processors for chemistry simulations.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Characterizing Noise-Induced Symmetry Breaking in Quantum Circuits

Experimental verification of noise-induced symmetry breaking requires precise protocols for quantifying both symmetry protection and dissipative effects:

Table: Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Noise-Induced Symmetry Breaking

| Protocol Objective | Key Measurements | Experimental Technique | Data Analysis Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identify SPT Phase | Edge mode localization, Boundary magnetization | Qubit tomography, Parity measurements | Many-body polarization, String order parameters |

| Quantify Dissipation | Entropy production, Decoherence rates | Quantum state tomography, Gate set tomography | Lindbladian reconstruction, Process tomography |

| Detect Symmetry Breaking | Symmetry operator expectation values | Randomized measurement, Interferometry | Quantum shadow estimation, Phase-sensitive detection |

| Measure Topological Robustness | State preparation and measurement fidelity | Randomized benchmarking, Loschmidt echo | Exponential decay fitting, Quantum trajectory analysis |

The experimental workflow begins with preparing the quantum system in a topological ground state, typically achieved through adiabatic state preparation or measurement-based quantum computing techniques. Researchers then characterize edge mode localization through spatially resolved quantum tomography, establishing baseline symmetry protection before introducing controlled noise channels. By systematically varying noise parameters while monitoring symmetry operator expectation values, the critical thresholds for symmetry breaking can be precisely determined.

Quantum Information Retrieval Protocols

For systems experiencing partial symmetry breaking, specialized protocols enable quantum information retrieval:

Quantum Jump Monitoring: By continuously measuring environmental interactions and recording quantum jump events, researchers can implement filtering operations that reconstruct the coherent component of system evolution. This approach leverages the trajectory-dependent memory of initial conditions preserved under weak symmetry conditions [12].

Error Mitigation Through Symmetry Verification: Quantum circuits can be designed to include symmetry verification steps that project the system back into the correct symmetry sector, effectively suppressing errors that break the protective symmetry. This technique requires redundant qubit encoding and mid-circuit measurements.

Metastable State Engineering: Under specific noise conditions, the steady-state manifold supports metastable logical qubits that persist for significantly longer timescales than individual physical qubits. Carefully designed initialization protocols can preferentially populate these protected subspaces.

These methodologies provide the experimental foundation for investigating noise-induced symmetry breaking across various quantum computing platforms, including superconducting qubits, trapped ions, and photonic quantum processors.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Investigating Noise in Quantum Circuits

The experimental investigation of noise-induced symmetry breaking requires specialized "research reagents" – quantum operations, measurement protocols, and theoretical tools that enable precise characterization of dissipative processes:

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Noise Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Experimental Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controlled Noise Channels | Amplitude damping, Phase damping, Depolarizing channels | Introduce well-characterized dissipative processes | Engineered reservoir coupling, Stochastic gate sequences |

| Symmetry Probes | Local order parameters, Non-local string operators | Quantify symmetry preservation or breaking | Interferometric measurements, Randomized benchmarking |

| Topological Invariants | Many-body polarization, Entanglement spectra | Characterize SPT order beyond local measurements | Quantum tomography, Shadow estimation techniques |

| Error Mitigation Protocols | Symmetry verification, Dynamical decoupling, Probabilistic error cancellation | Counteract specific symmetry-breaking noise | Software-level correction, Hardware-level control sequences |

These research reagents enable systematic studies of how different noise profiles affect symmetry-protected phases, facilitating the development of noise-resilient quantum circuits for computational chemistry applications. By combining controlled noise injection with precise symmetry probes, researchers can map comprehensive phase diagrams of topological stability under dissipative conditions.

Visualization: Quantum Circuit Symmetry Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental and theoretical workflow for analyzing noise-induced symmetry breaking in quantum circuits:

Implications for Quantum Computational Chemistry and Drug Development

The investigation of noise-induced symmetry breaking has profound implications for quantum computational chemistry research, particularly in drug development applications that rely on accurate molecular simulations. Quantum circuits designed to simulate molecular systems must maintain coherence throughout complex computational sequences, making them susceptible to symmetry-breaking noise that degrades computational accuracy. By leveraging the principles of symmetry-protected topological order, researchers can design quantum algorithms with built-in resilience to specific noise profiles, potentially extending the computational capabilities of near-term quantum processors for pharmaceutical applications.

Specific applications include:

Noise-Resilient Quantum Phase Estimation: Algorithms for determining molecular ground states can be protected using symmetry-aware circuit design that minimizes susceptibility to symmetry-breaking noise.

Topological Quantum Error Correction for Chemistry Simulations: Encoding chemical Hamiltonians into topological qubits provides inherent protection against local errors, potentially reducing the resource overhead for fault-tolerant quantum chemistry calculations.

Symmetry-Enhanced Variational Quantum Eigensolvers: By preserving molecular symmetries throughout variational optimization, quantum-classical algorithms can maintain physical relevance while mitigating noise-induced errors.

The integration of symmetry protection strategies with quantum computational chemistry represents a promising pathway toward practical quantum advantage in drug discovery, enabling more accurate prediction of molecular properties, reaction pathways, and binding affinities despite the inherent noise present in current quantum hardware.

The traditional view of environmental noise as an exclusively detrimental force in quantum information processing requires fundamental revision in light of recent advances in understanding noise-induced symmetry breaking. While certain noise profiles indeed destroy the protective symmetries enabling topological order, carefully engineered dissipative processes can paradoxically enhance quantum control and facilitate novel information retrieval protocols. The emerging paradigm recognizes noise as a physical resource that can be harnessed through sophisticated quantum control techniques, transforming a fundamental challenge into a potential opportunity for advancing quantum computational capabilities.

For quantum computational chemistry and drug development research, these insights provide a roadmap for developing noise-resilient quantum algorithms that maintain accuracy despite hardware imperfections. By classifying noise according to its symmetry-breaking characteristics and implementing appropriate error mitigation strategies, researchers can extend the computational horizon of quantum simulations for molecular systems. The continued investigation of noise-induced symmetry breaking will undoubtedly yield additional insights and techniques essential for realizing the full potential of quantum computing in pharmaceutical applications and beyond.

Linking Molecular Symmetries to Computational Invariants and Conservation Laws

The accurate simulation of molecular systems represents a primary application for emerging quantum technologies. However, current quantum hardware is prone to noise, which can destroy the essential physical characteristics of a simulated system. Foremost among these are symmetries and their associated conservation laws. This whitepaper details the critical link between molecular symmetries and computational invariants, framing it within the context of symmetry protection for noisy quantum computational chemistry. We provide a theoretical foundation, practical methodologies for identifying and verifying these symmetries on quantum computers, and a toolkit for researchers aiming to conduct robust simulations on contemporary hardware.

Theoretical Foundations: From Molecular Symmetry to Quantum Computation

Molecular Symmetries and Conservation Laws

In quantum mechanics, symmetries are features of a system that remain unchanged under a specific transformation, and they are fundamentally linked to conservation laws via Noether's theorem [14]. For a molecular Hamiltonian, common symmetries include:

- Geometric Symmetries: Arising from the point group of the molecular structure (e.g., rotations, reflections). These symmetries imply the conservation of quantum numbers like angular momentum [14].

- Particle Conservation: The conservation of the total number of electrons in the system.

- Spin Symmetries: The conservation of total spin (S² and S_z).

When a Hamiltonian possesses a symmetry, it commutes with the corresponding symmetry operator. That is, for a symmetry operator (\widehat{\Omega}) and Hamiltonian (\hat{H}), the commutator vanishes: ([\widehat{\Omega}, \hat{H}] = 0) [14]. This commutation relation implies that the energy eigenstates of the Hamiltonian can be labeled by the eigenvalues of the symmetry operator, which are invariants of the motion.

The Challenge of Symmetry in Quantum Computations

To run simulations on a quantum computer, the fermionic molecular Hamiltonian must be mapped to a qubit Hamiltonian. The Jordan-Wigner transformation is a common method for this, converting creation and annihilation operators into strings of Pauli matrices ((X, Y, Z)) [15] [2]. A significant challenge is that this transformation can mask the original symmetries of the molecular Hamiltonian. A symmetry that is manifest as a simple permutation of orbitals in the second-quantized form can become a complex, non-local operator in the Pauli representation [15]. On noisy hardware, errors can violate these symmetries, leading to unphysical results such as states that do not conserve the correct number of electrons or that have the wrong spin [16] [2].

Methodologies for Symmetry Identification and Verification

Revealing Hidden Symmetries in Qubit Hamiltonians

After a Jordan-Wigner transformation, the symmetries of the original Hamiltonian are still present but hidden. They can be recovered by identifying the subgroup of Clifford group transformations that correspond to the permutation symmetries of the original molecular orbitals [15]. The following theorem provides a practical method:

Theorem [15]: The transformation of Pauli strings under a permutation symmetry (P) of the original molecular Hamiltonian induces a group representation inside the group of symplectic matrices over the vector space (\mathbb{F}_2^{2n}). This representation can be computed, allowing for the explicit construction of the symmetry operator in the qubit space.

Table 1: Key Symmetry Types and Their Computational Invariants

| Symmetry Type | Original Molecular Form | Qubit Representation (Post-Jordan-Wigner) | Associated Invariant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Number | (\hat{N} = \sumi ai^\dagger a_i) | Complex Pauli string (parity-based) [15] | Electron Number |

| Spin Projection (S_z) | (\hat{S}z = \frac{1}{2} \sumi (a{i\uparrow}^\dagger a{i\uparrow} - a{i\downarrow}^\dagger a{i\downarrow})) | Complex Pauli string [15] | Magnetic Spin Quantum Number |

| Geometric (Point Group) | Permutation of orbital indices [15] | Clifford group transformation [15] | Parity, Point Group Quantum Number |

Experimental Protocols for Symmetry Verification on Noisy Hardware

Once symmetries are identified, they must be protected during computation on noisy devices. The following protocols, derived from recent research, enable this verification.

Protocol 1: Dynamical Post-Selection (DPS) for Non-Abelian Symmetries

Application: Tailored for non-Abelian lattice gauge theories, suitable for state-of-the-art qudit platforms [16].

- State Preparation: Initialize the system in a state that is invariant under the target non-Abelian symmetry group (e.g., (D_3)).

- Weak Mid-Circuit Measurement: During the evolution, repeatedly perform weak measurements of the non-commuting symmetry generators.

- Quantum Zeno Effect: The frequent measurements project the system onto the symmetry-invariant subspace, effectively freezing the evolution and suppressing symmetry-violating errors via the quantum Zeno effect.

- Post-Selection: At the end of the circuit, discard any result where the final measurement of the symmetry generators does not yield the correct eigenvalue.

This protocol is effective against fast-fluctuating noise and does not require active feedback [16].

Protocol 2: Post-Processed Symmetry Verification (PSV)

Application: A measurement-based technique to extract the gauge-invariant part of an observable, also designed for non-Abelian theories [16].

- Ancilla-Free Measurement: Run the quantum circuit without additional verification qubits.

- Measure Correlations: For a target observable (O), measure its correlation with all elements (g) of the gauge group (G): (\langle \psi | g^\dagger O g | \psi \rangle).

- Reconstruct Invariant Value: The true gauge-invariant expectation value is obtained by averaging these results: (\langle O \rangle{\text{invariant}} = \frac{1}{|G|} \sum{g \in G} \langle \psi | g^\dagger O g | \psi \rangle).

This method leverages the structure of the group transformations to mitigate errors and recover reliable data from noisy runs [16].

The workflow for selecting and applying these protocols is as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

To implement the aforementioned protocols, researchers require a set of conceptual and practical tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Symmetry-Protected Quantum Simulation

| Item / Technique | Function in Experiment | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner Transform | Encodes fermionic Hamiltonians into qubit operators. | Masks original symmetries; necessary first step [15] [2]. |

| Clifford Group Theory | Provides framework to reveal hidden symmetries in qubit Hamiltonians. | Used to compute action of permutation symmetries on Pauli strings [15]. |

| Symmetry Generators | Operators representing fundamental symmetries (e.g., (S_z), particle number). | Their measurement is key to verification protocols [16] [15]. |

| Mid-Circuit Measurement | Allows probing system state without terminating circuit. | Enables Dynamical Post-Selection (DPS) [16]. |

| Noise Models | Simulates impact of decoherence, gate error, and measurement error. | Used to test robustness of verification protocols [2]. |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | Hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for finding ground states. | Accuracy depends on ansatz symmetry and noise [2]. |

| Phortress free base | Phortress free base, CAS:741241-36-1, MF:C20H23FN4OS, MW:386.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SARS-CoV-2-IN-59 | 4-(4,5-Dihydro-1H-imidazol-2-yl)benzonitrile|CAS 850786-33-3 | 4-(4,5-Dihydro-1H-imidazol-2-yl)benzonitrile (SARS-CoV-2-IN-59). High-purity compound for research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Case Study & Data Presentation

Numerical Simulation of Noisy Quantum Circuits

Studies simulating the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) for molecules like sodium hydride (NaH) illustrate the impact of noise and the importance of ansatz selection. Numerical simulations show that gate-based noise rapidly degrades both the energy estimate and the state fidelity (the overlap with the true ground state) [2].

Table 3: Impact of Noise and Ansatz Choice on VQE Simulation (Representative Data from [2])

| Simulation Condition | Ansatz Type | Relative Energy Error | State Fidelity | Parameter Optimization Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noiseless | UCCSD | < 1% | > 0.99 | BFGS |

| Noisy (NISQ) | UCCSD | 5-15% | ~0.70 | COBYLA |

| Noisy (NISQ) | Singlet-Adapted UCCSD | 3-8% | ~0.85 | COBYLA |

| Noisy (NISQ) with Symmetry Verification | UCCSD | 2-5% | > 0.90 | COBYLA |

Key findings include:

- Ansatz Expressivity: An ansatz that inherently respects molecular symmetries (e.g., singlet-adapted UCCSD) maintains higher fidelity under noise compared to a more general but symmetry-violating ansatz [2].

- Optimizer Choice: Gradient-based optimizers like BFGS can outperform derivative-free methods like COBYLA in noiseless simulations, but their performance can degrade significantly with noise [2].

- Symmetry Verification: Applying symmetry verification protocols can recover a high-fidelity, physical state even after noise has corrupted the unmitigated result, reducing both energy error and state infidelity [16].

The following diagram summarizes the experimental workflow for a symmetry-aware VQE experiment:

The link between molecular symmetries and computational invariants is not merely a theoretical curiosity but a practical necessity for reliable quantum computational chemistry. As demonstrated, noise in current quantum hardware can easily violate these symmetries, producing unphysical results. The methodologies outlined—from uncovering symmetries obscured by the Jordan-Wigner transformation to implementing advanced verification protocols like DPS and PSV—provide a roadmap for researchers. Integrating these techniques into quantum simulation workflows, from ansatz design to final measurement, is essential for extracting chemically meaningful results and advancing the field of drug development on noisy quantum computers. The ongoing development of these symmetry-protection strategies will be a critical factor in achieving a quantum advantage in computational chemistry.

The Impact of Symmetry Breaking on Molecular Energy Calculations

In quantum computational chemistry, the protection of physical symmetries is a fundamental prerequisite for obtaining reliable results. Symmetries inherent to molecular systems, such as the total spin, provide critical constraints that quantum simulations must preserve. However, the presence of noise in modern Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices can lead to symmetry breaking, where the simulated state drifts into unphysical sectors of the Hilbert space, compromising the fidelity of energy calculations [16]. This challenge is particularly acute in open-shell molecules and multi-spin systems, where the energy differences between spin states are small and require high precision. The development of strategies to mitigate, verify, and exploit symmetry breaking has therefore become a central focus in the field, bridging the gap between abstract quantum algorithms and practical chemical applications. This guide examines the impact of symmetry breaking on molecular energy calculations, exploring both its disruptive effects and the novel computational strategies it has inspired, all within the context of advancing symmetry protection in noisy quantum computational chemistry research.

Theoretical Foundations of Quantum Symmetry

The Role of Spin Symmetry in Molecular Hamiltonians

In quantum chemistry, the electronic Hamiltonian commutes with the total spin operator ( \hat{S}^2 ), meaning that physical eigenstates must also be eigenstates of ( \hat{S}^2 ) with appropriate quantum numbers. For molecules with two or more unpaired electrons, the correct characterization of spin states becomes essential for accurately determining energy gaps. The Heisenberg spin Hamiltonian, ( H = -2J{ij} \hat{S}i \cdot \hat{S}_j ), is often employed to describe the magnetic interaction between unpaired electrons, where the exchange coupling parameter ( J ) quantifies the energy difference between high-spin and low-spin configurations [17]. The eigenvalue of this Hamiltonian is ( \frac{3J}{2} ) for the spin-singlet and ( -\frac{J}{2} ) for the spin-triplet state in a two-spin system. The accurate computation of ( J ), which is typically on the order of kcal molâ»Â¹, is a critical test for quantum computational methods, as it demands high precision in energy calculations.

Broken-Symmetry Approaches in Classical Quantum Chemistry

Classical computational chemistry has long grappled with the challenges of spin symmetry, particularly for open-shell singlet states which possess strong multi-configurational character. Single-reference methods like Hartree-Fock (HF) and standard Density Functional Theory (DFT) struggle with these systems because a single Slater determinant cannot represent a pure spin eigenstate for an open-shell singlet [17]. This limitation led to the development of broken-symmetry (BS) wavefunctions, which are spin-contaminated mixtures of singlet and triplet states, e.g., ( |\Psi{BS}\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(|\Psi{HS}\rangle + |\Psi{LS}\rangle) ) [17]. Although unphysical, these BS wavefunctions can be leveraged to extract correct energy differences using relationships like Yamaguchi's equation: ( J = \frac{E{HS} - E{BS}}{\langle \hat{S}^2 \rangle{HS} - \langle \hat{S}^2 \rangle{BS}} ), where ( E{HS} ) and ( E_{BS} ) are the energies of the high-spin and broken-symmetry states, respectively [17]. This pragmatic approach demonstrates how controlled symmetry breaking, followed by careful correction, can yield physically meaningful results.

Symmetry Breaking in Noisy Quantum Simulations

Error-Induced Symmetry Breaking on NISQ Devices

On noisy quantum hardware, intrinsic errors from decoherence, gate infidelities, and readout noise can cause a prepared quantum state to deviate from the intended symmetry sector. For lattice gauge theories and molecular simulations, this results in the population of unphysical states that violate gauge constraints or spin symmetries [16]. Unlike Abelian symmetries, non-Abelian symmetries present a particular challenge because their non-commuting nature complicates the implementation of standard error correction and verification schemes [16]. If left unchecked, this uncontrolled symmetry breaking rapidly washes out physical information, rendering simulation results meaningless. The problem is especially severe for energy calculations of molecular spin systems, where the quantities of interest are small energy differences that can be easily obscured by noise-induced symmetry violations.

Algorithmic Implications for Energy Calculations

Conventional quantum algorithms for energy calculation, such as Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE), require separate computations for individual spin states to determine energy gaps. For example, calculating the singlet-triplet energy gap ( \Delta E{S-T} ) typically involves independently estimating the energies of the singlet and triplet states and then computing their difference: ( J = \frac{\Delta E{S-T}}{2} ) for two-spin systems [17]. This approach is particularly expensive on quantum computers when chemical precision ( ~1 kcal molâ»Â¹) is required for small energy gaps. Furthermore, noise-induced symmetry breaking can introduce systematic errors in each energy estimation, compounding the inaccuracy in the final result. This vulnerability has driven the development of new algorithms that either directly compute energy differences without individual state energies or incorporate explicit symmetry protection.

Mitigation Strategies: Symmetry Verification and Protection

Symmetry Verification Techniques

Symmetry verification techniques aim to identify and discard results that violate physical symmetries, thereby mitigating the impact of hardware noise. For non-Abelian gauge theories, two advanced methods have been developed:

- Dynamical Post-Selection (DPS): This technique repeatedly performs weak mid-circuit measurements of symmetry operators without active feedback, exploiting the quantum Zeno effect to suppress transitions away from the target symmetry sector [16].

- Post-Processed Symmetry Verification (PSV): This method combines measurements of correlations between target observables and gauge transformations to extract the gauge-invariant component of an observable from a collection of noisy measurements [16].

Both approaches can recover reliable dynamics long after physical information has been lost in bare noisy simulations and are particularly suitable for state-of-the-art qudit platforms [16].

The BxB Algorithm: Exploiting Symmetry for Direct Computation

The Bayesian exchange coupling parameter calculator with broken-symmetry wave functions (BxB) represents a novel algorithmic approach that strategically incorporates symmetry terms to directly compute the exchange coupling parameter ( J ) without requiring the individual energies of spin states [17]. The BxB algorithm comprises three key components:

- Quantum Simulation with Augmented Hamiltonian: It simulates the time evolution of a broken-symmetry wave function under a modified Hamiltonian that includes an additional term ( j\hat{S}^2 ).

- Wavefunction Overlap Estimation: The SWAP test is used to estimate the overlap between the time-evolved state and a reference state.

- Bayesian Optimization: A Bayesian optimizer is employed to find the parameter ( j ) that yields the desired overlap, from which the ( J ) value is directly obtained [17].

This method has been demonstrated to compute ( J ) values within 1 kcal molâ»Â¹ of error for various systems, including Hâ‚‚, Oâ‚‚, and Nâ‚‚ molecules, with less computational overhead than conventional QPE-based approaches [17]. The workflow of this algorithm is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. BxB Algorithm Workflow for Direct J Calculation.

Error-Mitigated Ground State Preparation

Preparing the ground states of many-body Hamiltonians on noisy quantum processors is a fundamental challenge for quantum simulation. The Quantum Imaginary-Time Evolution (QITE) method is an effective approach for ground state preparation. It propagates an initial state ( |\psi0\rangle ) toward the ground state through non-unitary dynamics: ( |\psi{\text{ground}}\rangle \approx e^{-\beta H} |\psi0\rangle / \sqrt{\| e^{-\beta H} |\psi0\rangle \|} ) [18]. To implement this non-unitary operation on a quantum computer, the system is embedded into an extended Hilbert space with an ancilla qubit, allowing the non-unitary operation to be represented as a unitary operation on the larger system [18]. This ancilla-based QITE can be combined with error mitigation strategies like Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) to enhance robustness. In ZNE, the circuit depth is systematically varied (e.g., by adding identity layers) to extrapolate results to the zero-noise limit, enabling more accurate simulations of phase transitions and entanglement properties in symmetry-protected topological phases [18].

Experimental and Numerical Protocols

Protocol for BxB Algorithm Implementation

The following protocol outlines the steps for implementing the BxB algorithm to calculate the exchange coupling parameter ( J ) for a biradical molecule.

Initial State Preparation:

- Prepare the broken-symmetry wave function ( |\Psi_{BS}\rangle ) on the quantum processor. This state is typically a mixture of singlet and triplet configurations and can be initialized using appropriately parameterized quantum circuits.

Parameterized Hamiltonian Simulation:

- Construct the modified Hamiltonian ( H' = H - j\hat{S}^2 ), where ( H ) is the molecular electronic Hamiltonian and ( j ) is a parameter to be optimized.

- Implement the time evolution operator ( e^{-iH't} ) for a chosen time step ( t ) using Trotterization or other product formulas.

Overlap Measurement:

- Use the SWAP test circuit to estimate the overlap between the time-evolved state ( e^{-iH't} |\Psi{BS}\rangle ) and the original reference state ( |\Psi{BS}\rangle ).

- Perform repeated measurements to estimate the overlap ( |\langle\Psi{BS}| e^{-iH't} |\Psi{BS}\rangle|^2 ) with sufficient precision.

Bayesian Optimization Loop:

- Initialize a Bayesian optimization routine with a prior distribution for the parameter ( j ).

- Use the measured overlaps as the objective function to update the posterior distribution of ( j ).

- Iterate steps 2-4 until the parameter ( j ) converges. The converged value is directly related to the exchange coupling parameter ( J ) of the Heisenberg Hamiltonian.

Validation:

- Validate the computed ( J ) value by comparing with classical reference calculations (e.g., CASSCF) or experimental data where available.

Protocol for Symmetry Verification in G Theory Simulation

This protocol describes the application of symmetry verification for simulating non-Abelian lattice gauge theories, such as those with the discrete group ( D_3 ), on qudit hardware.

State Preparation and Time Evolution:

- Initialize the system in a physical state that respects the initial gauge symmetry.

- Apply the time evolution sequence corresponding to the target lattice gauge theory Hamiltonian.

Dynamical Post-Selection (DPS) Implementation:

- Option A (DPS): At regular intervals during the time evolution, perform weak, non-demolition measurements of a set of non-commuting symmetry generators ( {G_i} ).

- Post-Selection: Discard any experimental run where the measurement outcomes indicate a deviation from the target symmetry sector. The frequency of measurements creates a Zeno effect, suppressing symmetry-breaking errors.

Post-Processed Symmetry Verification (PSV) Implementation:

- Option B (PSV): After completing the time evolution, measure the correlation functions between the target observable ( O ) (e.g., energy) and a set of gauge transformation operators ( U(g) ) for group elements ( g ) in the symmetry group.

- Reconstruction: Compute the gauge-invariant component of the observable by averaging over the symmetry group: ( O{\text{invariant}} = \frac{1}{|G|} \sum{g} \langle U(g)^\dagger O U(g) \rangle ).

Data Analysis:

- Compare the dynamics obtained from DPS or PSV with the bare, unmitigated results and the exact theoretical prediction to assess the efficacy of symmetry verification in extending the useful simulation time.

Performance Analysis and Data

Quantitative Performance of Quantum Algorithms

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Quantum Algorithms for Spin Energy Gap Calculation

| Algorithm | Key Principle | Computational Cost | Reported Accuracy (J value) | Applicable Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) [17] | Direct energy estimation of individual spin states | High (exponential in desired precision) | Requires extreme precision for small ΔE | General purpose, but costly for energy gaps |

| BxB Algorithm [17] | Direct J calculation via Bayesian optimization on BS state | Lower than QPE; polynomial cost for overlap | Within 1 kcal molâ»Â¹ error | Hâ‚‚, Oâ‚‚, Nâ‚‚, CHâ‚‚, NF, etc. |

| Ancilla-based QITE with ZNE [18] | Imaginary-time evolution with noise extrapolation | Moderate (depends on system size and depth) | Accurate for phase transition boundaries | Many-body SPT phases (e.g., Ising-cluster model) |

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Symmetry-Conscious Quantum Chemistry

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Symmetry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broken-Symmetry Wavefunction [17] | Algorithmic Component | Serves as the initial state for direct J-calculation algorithms like BxB. | Controlled breaking of spin symmetry enables efficient computation of spin-dependent energies. |

| SWAP Test [17] | Quantum Subroutine | Measures the overlap between two quantum states. | Critical for the BxB algorithm to track state evolution under the parameterized Hamiltonian. |

| Bayesian Optimizer [17] | Classical Optimizer | Finds optimal parameter j in the modified Hamiltonian. |

Drives the BxB algorithm toward the correct J value without calculating total energies. |

| SMIRNOFF (SMIRKS Native Open Force Field) [19] | Force Field Format | Uses SMIRKS patterns for direct chemical perception in parameter assignment. | Moves beyond indirect atom typing, allowing more nuanced and symmetric parameter assignment. |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) [18] | Error Mitigation Technique | Extrapolates results from noisy circuits to the zero-noise limit. | Improves the accuracy of symmetry properties and energies from noisy quantum simulations. |

| Qubit/Qudit Hardware [16] | Physical Platform | Executes quantum circuits. | Native qudit platforms can offer more natural representations of non-Abelian symmetries. |

The accurate treatment of symmetry is a cornerstone of reliable molecular energy calculations, a challenge magnified by the inherent noise of current quantum hardware. While symmetry breaking poses a significant threat to computational fidelity, the development of sophisticated mitigation and verification strategies—such as the BxB algorithm, dynamical post-selection, and error-mitigated QITE—is turning this challenge into an opportunity. These approaches, which either enforce symmetry during computation or cleverly exploit broken-symmetry states, are extending the frontier of what is possible on NISQ devices. As quantum processors continue to evolve, the integration of robust symmetry protection protocols will be indispensable for achieving chemically accurate simulations of complex molecular systems, ultimately accelerating progress in materials science and drug development.

Methodological Pipeline: Applying Symmetry Protection to Real-World Drug Discovery

Automated Algorithms for Detecting Symmetry-Protected Subspaces

In the field of noisy quantum computational chemistry, protecting quantum simulations from decoherence and errors is a fundamental challenge. The concept of symmetry-protected subspaces offers a powerful framework for mitigating these errors by restricting the quantum dynamics to specific portions of the Hilbert space that remain invariant under certain symmetry operations [20]. In quantum chemistry simulations, these symmetries often correspond to physical conservation laws, such as particle number conservation or molecular point group symmetries [20]. The automated detection of these subspaces enables more efficient quantum error mitigation strategies, extending the computational capabilities of near-term quantum devices without requiring full fault tolerance [16] [21].

This technical guide examines core algorithms for the automated identification of symmetry-protected subspaces, detailing their theoretical foundations, implementation protocols, and practical applications in noisy quantum simulations for computational chemistry and drug development research.

Theoretical Foundation of Symmetry-Protected Subspaces

Symmetry in Quantum Systems

Symmetries in quantum systems imply conservation laws, which partition the Hilbert space into invariant subspaces of the time-evolution operator [1]. Each subspace is characterized by its conserved quantity. From a mathematical perspective, a symmetry group G acting on a Hilbert space induces a decomposition into irreducible representations, each corresponding to a symmetry-protected subspace [20]. The discovery of these subspaces does not necessarily require explicit identification of a symmetry operator or its eigenvalues, enabling efficient classical algorithms for their detection [1].

Significance for Noisy Quantum Simulation

In the context of noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, symmetry-protected subspaces provide a critical error-mitigation strategy. By constraining quantum dynamics to an invariant subspace, researchers can effectively filter out errors that violate the underlying symmetry of the physical system being simulated [16]. This approach is particularly valuable for quantum computational chemistry, where molecular Hamiltonians often exhibit rich symmetry structures that can be exploited to enhance simulation fidelity [20] [21].

Core Algorithms and Detection Methodologies

Transitive Closure on State Transition Graphs

Rotello et al. introduced two classical algorithms that form the foundation for automated detection of symmetry-protected subspaces [1] [3].

Table 1: Core Algorithms for Subspace Detection

| Algorithm Name | Time Complexity | Key Function | Error Handling | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subspace Exploration | Linear in subspace size (O( | S | )) | Discovers entire symmetry-protected subspace of an initial state | Bounded error tolerance for noisy quantum simulations |

| Membership Verification | Polynomial in system size | Determines if a measurement outcome belongs to a specified subspace | Explicit bounded error parameters |

The first algorithm explores the entire symmetry-protected subspace of an initial state by closing local basis state-to-basis state transitions [1]. The methodology operates as follows:

- Graph Representation: Represent the quantum system as a graph where nodes correspond to computational basis states and edges represent possible transitions under k-local unitary operations [1].

- Transition Closure: Compute the transitive closure of this graph starting from an initial state, grouping all states reachable through symmetry-preserving operations [1].

- Subspace Identification: The connected components of the graph correspond to distinct symmetry-protected subspaces [1] [3].

This approach efficiently identifies the invariant subspace without constructing matrices of the full Hilbert space dimension, making it scalable for quantum chemistry applications [1].

Symmetry Verification Protocols

Beyond identification, verification of symmetry preservation during quantum computation is essential. The following protocols enable practical implementation:

Dynamical Post-Selection (DPS): Based on mid-circuit measurements without active feedback, creating a quantum Zeno effect that suppresses symmetry-breaking errors [16].

Post-Processed Symmetry Verification (PSV): Combines measurements of correlations between target observables and gauge transformations to extract the symmetry-invariant component of an observable [16].

Table 2: Symmetry Verification Methodologies

| Method | Measurement Type | Hardware Requirements | Implementation Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamical Post-Selection (DPS) | Mid-circuit non-demolition | Qudit or qubit platforms with measurement capabilities | Moderate (repeated measurements) |

| Post-Processed Symmetry Verification (PSV) | Circuit end-point measurements | Standard qubit platforms | Low (classical post-processing) |

| Symmetric Channel Verification | Quantum channel characterization | Universal quantum processors | High (complete process tomography) |

Algorithmic Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for automated detection and verification of symmetry-protected subspaces in quantum simulations:

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol for Subspace Discovery

The practical implementation of symmetry-protected subspace detection requires the following experimental protocol:

System Initialization:

- Prepare the quantum system in a reference state within the expected symmetry sector

- For quantum chemistry applications, this is typically a Hartree-Fock or reference CI state [20]

State Transition Mapping:

- Identify all k-local unitary operations that commute with the expected symmetry

- Map the connectivity between computational basis states under these operations [1]

Subspace Identification:

Verification and Validation:

- Implement symmetry verification protocols (DPS or PSV) during quantum simulation

- Measure symmetry operators to confirm confinement to the identified subspace [16]

Application to Specific Quantum Systems

The algorithms have been demonstrated successfully on several quantum simulation benchmarks:

Heisenberg-XXX Model: This quantum magnetic system exhibits SU(2) symmetry, and the algorithms successfully identified the corresponding subspaces characterized by total spin quantum numbers [1].

Quantum Cellular Automata (T₆ and F₄): For these discrete dynamical systems, the algorithms discovered hidden symmetries that partition the Hilbert space into invariant sectors [1] [3].