Intrinsic Fault Tolerance in Quantum Chemistry Algorithms: A New Pathway for Accelerated Drug Discovery

This article explores the emerging paradigm of intrinsic fault tolerance within quantum chemistry algorithms, a transformative approach poised to overcome the persistent challenge of noise in quantum computations.

Intrinsic Fault Tolerance in Quantum Chemistry Algorithms: A New Pathway for Accelerated Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the emerging paradigm of intrinsic fault tolerance within quantum chemistry algorithms, a transformative approach poised to overcome the persistent challenge of noise in quantum computations. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we dissect the foundational principles of Algorithmic Fault Tolerance (AFT) and its synergy with reconfigurable hardware like neutral-atom arrays. The scope spans from methodological advances that drastically reduce error-correction overhead to concrete applications in simulating complex biological systems such as cytochrome P450 enzymes and covalent inhibitors. By providing a comparative analysis against classical and other quantum methods, alongside a troubleshooting guide for implementation, this resource maps a clear trajectory for leveraging fault-tolerant quantum chemistry to tackle previously intractable problems in molecular simulation and rational drug design.

The Quantum Noise Problem and the Promise of Intrinsic Fault Tolerance

Quantum chemistry aims to predict the chemical and physical properties of molecules by solving the Schrödinger equation, a fundamental pillar of molecular quantum mechanics. However, the computational complexity of finding exact solutions to this equation for systems with more than one electron presents what is known as "Dirac's Conundrum." In 1929, Paul Dirac himself noted that "the fundamental laws necessary for the mathematical treatment of a large part of physics and the whole of chemistry are thus completely known, and the difficulty lies only in the fact that application of these laws leads to equations that are too complex to be solved" [1]. This statement encapsulates the fundamental challenge of quantum chemistry: while we possess the correct theoretical framework, the computational burden of obtaining accurate solutions for chemically relevant systems remains prohibitive for classical computers.

The heart of this conundrum lies in the exponential scaling of the quantum many-body problem. For an N-electron system, the wave function depends on 3N spatial coordinates, making direct computation intractable for all but the smallest molecules. This scaling problem has driven the development of approximate computational methods on classical computers, but each introduces its own limitations and trade-offs between accuracy and computational cost. The emergence of quantum computing offers a promising pathway to overcome this fundamental limitation, as quantum processors naturally mimic quantum systems and can, in principle, handle this exponential scaling efficiently. This technical guide explores how recent advances in quantum error correction and fault-tolerant algorithms are creating a paradigm shift in addressing Dirac's Conundrum, with particular focus on intrinsic fault tolerance in quantum chemistry algorithms.

The Path to Fault-Tolerant Quantum Chemistry

The Error Correction Imperative

Current quantum hardware operates in what is termed the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, characterized by quantum processors without comprehensive error correction. On such devices, algorithmic performance is severely constrained by noise that limits circuit depth and system size [2]. This noise manifests through various channels including decoherence, gate imperfections, and measurement errors, which collectively impede the accurate simulation of chemical systems. For quantum chemistry to progress beyond proof-of-concept demonstrations on minimal systems, overcoming these error limitations is essential.

The transition from the NISQ era to fault-tolerant quantum computing represents the critical path toward practical quantum chemistry applications. Fault tolerance employs quantum error correction (QEC) codes to protect logical quantum information by encoding it across multiple physical qubits, enabling the detection and correction of errors without disturbing the fragile quantum state [3]. This approach allows for arbitrarily long quantum computations provided the physical error rate is below a certain threshold. Recent experimental breakthroughs have demonstrated that QEC can indeed improve the performance of quantum chemistry algorithms despite increasing circuit complexity, challenging the assumption that error correction necessarily adds more noise than it removes on current hardware [3].

Breakthrough Experiments in Error-Corrected Quantum Chemistry

In 2023, researchers at Quantinuum achieved a significant milestone by performing the first quantum chemistry simulation using a partially fault-tolerant algorithm with logical qubits [4]. Their experiment calculated the ground state energy of molecular hydrogen (Hâ‚‚) using the quantum phase estimation (QPE) algorithm implemented on three logical qubits with error detection. The team employed a newly developed error detection code designed specifically for their H-series quantum hardware, which conserved quantum resources by immediately discarding calculations where errors were detected [4].

This work was substantially advanced in 2025 when the same team demonstrated the first complete quantum chemistry computation using quantum error correction on real hardware [3]. The experiment utilized a seven-qubit color code to protect each logical qubit and inserted additional QEC routines mid-circuit to catch and correct errors as they occurred. Despite the circuit complexity involving up to 22 qubits, more than 2,000 two-qubit gates, and hundreds of intermediate measurements, the error-corrected implementation produced an energy estimate within 0.018 hartree of the exact value [3]. While this accuracy still falls short of the "chemical accuracy" threshold of 0.0016 hartree required for predictive chemical applications, it represents a critical proof-of-concept that error correction can enhance algorithmic performance even on current quantum devices.

Table 1: Key Metrics from Recent Error-Corrected Quantum Chemistry Experiments

| Experimental Parameter | Quantinuum 2023 Experiment | Quantinuum 2025 Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Target Molecule | Hydrogen (Hâ‚‚) | Hydrogen (Hâ‚‚) |

| Algorithm | Stochastic Quantum Phase Estimation | Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) |

| Logical Qubits | 3 | Not specified |

| Error Protection | Error detection code | Seven-qubit color code with mid-circuit correction |

| Circuit Complexity | Not specified | >2,000 two-qubit gates, hundreds of measurements |

| Accuracy | More accurate than non-error-detected version | Within 0.018 hartree of exact value |

| Key Innovation | First simulation with logical qubits | First end-to-end QEC chemistry computation |

Intrinsic Quantum Codes: A Theoretical Framework

A promising theoretical development toward intrinsic fault tolerance comes from the emerging concept of "intrinsic quantum codes." This framework, pioneered by Kubischna and Teixeira, defines quantum codes not as specific hardware implementations but as intrinsic geometric structures within group representations [5]. An intrinsic code is defined as a subspace within a group representation, establishing that any physical realization of this code inherently possesses specific error-correcting properties.

The power of this approach lies in its unification of diverse fault-tolerant schemes across different hardware platforms through underlying symmetry principles. By identifying a single intrinsic code, researchers can simultaneously determine properties applicable to all its physical realizations. This Schur-Bootstrap framework mathematically guarantees that if an intrinsic code satisfies the Knill-Laflamme conditions for error correction within a specific mathematical sector, then any physical realization of that code will also satisfy these conditions in the corresponding sector [5]. This means that abstract properties of the intrinsic code are automatically inherited by its physical manifestation, providing a powerful method for "bootstrapping" error protection from abstract mathematical spaces to physical quantum devices.

Quantum Algorithmic Strategies for Chemistry

Core Quantum Chemistry Algorithms

The development of fault-tolerant quantum algorithms for chemistry applications has centered primarily on quantum phase estimation (QPE) and its variants. QPE is a fundamental quantum algorithm that enables the determination of the eigenvalues of a unitary operator, making it particularly suitable for calculating molecular energy levels [3]. The algorithm works by estimating the phase accumulated by a quantum state as it evolves under the system's Hamiltonian, which describes its energy. For the molecular electronic structure problem, this involves preparing an initial guess of the molecular wavefunction and then using controlled operations to extract energy eigenvalues through quantum interference.

While QPE is powerful and theoretically well-founded, it requires deep circuits and high gate counts that make it challenging to implement on current hardware. Recent research has explored variations such as stochastic quantum phase estimation that reduce resource requirements [4]. Alternative approaches like variational quantum algorithms (VQEs) have gained attention for their shallower circuit depths, but they face challenges with optimization and accuracy limitations. The trade-offs between these approaches represent active research frontiers as the field progresses toward fault-tolerant implementations.

Table 2: Quantum Algorithms for Electronic Structure Problems

| Algorithm | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) | Eigenvalue estimation via phase accumulation | Proven correctness, conceptual clarity | Deep circuits, sensitive to noise |

| Stochastic QPE | Probabilistic implementation of QPE | Reduced resource requirements | Increased measurement overhead |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | Hybrid quantum-classical optimization | Shallower circuits, NISQ-friendly | Optimization challenges, accuracy limits |

| Recent Advances (2025) | Real-space methods with adaptive grids | Reduced resources, first quantization | Early development stage [6] |

Data Encoding Strategies for Quantum Chemistry

A critical component of quantum chemistry algorithms is the encoding of classical chemical information into quantum states. The choice of encoding strategy significantly impacts resource requirements and algorithmic performance. Several approaches have been developed, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Basis encoding: Represents classical information in the computational basis states of qubits, mapping binary strings to quantum states. This approach is straightforward but can be resource-intensive for chemical applications.

Angle encoding: Encodes classical data into rotation angles of qubits, providing a compact representation that is efficient for certain types of chemical data.

Amplitude encoding: Represents classical data in the amplitudes of a quantum state, allowing an n-dimensional vector to be encoded into logâ‚‚(n) qubits. This approach is highly efficient for state preparation but can be challenging to implement [2].

Recent comparative studies have demonstrated that quantum data embedding can contribute to improved classification accuracy and F1 scores in machine learning applications for chemistry, particularly for models that benefit from enhanced feature representation [2]. The integration of these encoding strategies with error-corrected algorithms represents an active area of research aimed at optimizing the trade-off between representation efficiency and error resilience.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Error-Corrected Quantum Phase Estimation Protocol

The groundbreaking 2025 experiment demonstrating error-corrected quantum chemistry followed a detailed methodological protocol [3]. The implementation involved several key stages:

Hamiltonian Formulation: The molecular Hamiltonian for Hâ‚‚ was encoded into a quantum-readable format using the Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation, mapping fermionic operators to qubit operators.

Logical Qubit Encoding: Each logical qubit was encoded using a seven-qubit color code, which protected against certain types of errors through redundancy and specific entanglement structures.

State Preparation: An initial approximation of the ground state was prepared using techniques adapted from classical computational chemistry.

Controlled Time Evolution: The QPE algorithm implemented controlled application of the time evolution operator U = e^{-iHt}, where H is the molecular Hamiltonian, using Trotterization or more advanced product formulas to decompose the complex operation into native gate operations.

Mid-Circuit Error Correction: Quantum error correction routines were inserted between critical operations, leveraging the H2 quantum computer's capability for intermediate measurements and conditional operations.

Quantum Fourier Transform: The final stage applied the inverse quantum Fourier transform to extract phase information, which was then converted to energy eigenvalues.

The researchers employed both fully fault-tolerant and partially fault-tolerant methods in their implementation. Partially fault-tolerant gates, while not immune to all single errors, reduce the risk of logical faults with significantly less overhead, making them practical for current devices [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Components for Fault-Tolerant Quantum Chemistry Experiments

| Component | Function | Specific Examples/Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Trapped-Ion Quantum Computer | Physical platform for quantum computation | Quantinuum H-Series with all-to-all connectivity, high-fidelity gates [4] [3] |

| Error Correction Codes | Protection of logical quantum information | Seven-qubit color code, error detection codes [4] [3] |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Algorithm implementation and compilation | InQuanto platform for quantum computational chemistry [4] |

| Mid-Circuit Measurement | Real-time error detection and correction | Native capability on H-Series hardware [3] |

| Dynamical Decoupling Sequences | Mitigation of memory noise | Reduction of idle qubit errors [3] |

| Logical-Level Compilers | Optimization of quantum circuits for specific QEC schemes | Translation from physical to logical gate operations [3] |

| 3'-Deoxyuridine-5'-triphosphate | 3'-Deoxyuridine-5'-triphosphate, CAS:69199-40-2, MF:C9H15N2O14P3, MW:468.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| APOBEC3G-IN-1 | APOBEC3G-IN-1, MF:C15H11NO3, MW:253.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization of Quantum Error Correction Workflows

Logical Qubit Protection Scheme

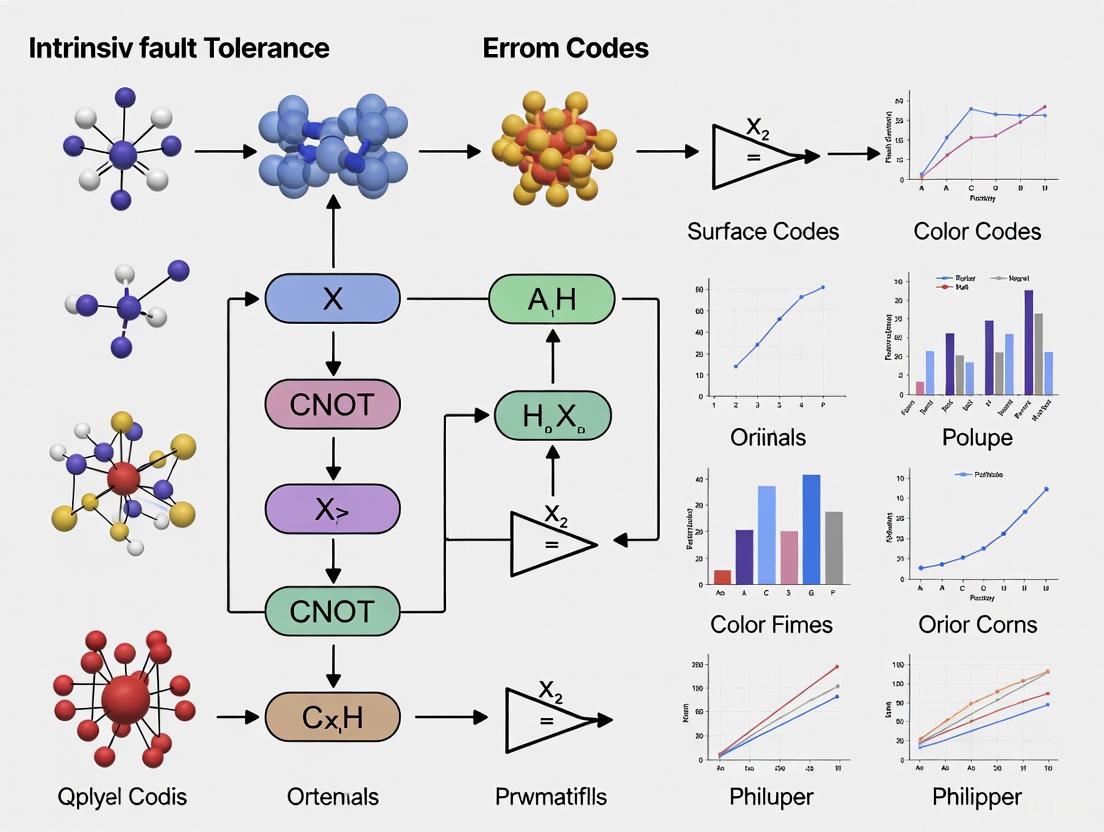

Diagram 1: Logical Qubit Protection in Quantum Chemistry Simulations. This workflow illustrates how physical qubits are encoded into logical qubits with ongoing error detection and correction during computation.

Intrinsic Code Realization Framework

Diagram 2: Intrinsic Code Framework Unifying Quantum Error Correction. This diagram shows how a single intrinsic code defined in an abstract space dictates properties across diverse physical implementations through group representation mapping.

Future Directions & Research Frontiers

The field of fault-tolerant quantum chemistry is advancing rapidly, with several clear research directions emerging. Current efforts focus on developing higher-distance error correction codes capable of correcting more than one error per logical qubit, which would significantly enhance computational reliability [3]. Another promising direction involves bias-tailored codes that specifically target the most common error types in a given hardware platform, optimizing the efficiency of error correction.

On the algorithmic front, researchers are working to refine quantum phase estimation and develop alternative approaches that reduce resource requirements while maintaining accuracy. Recent work on real-space methods with adaptive grids in first quantization shows potential for substantial resource reductions [6]. Additionally, the integration of quantum error detection and correction directly into industrial computational workflows represents a critical step toward practical application, with companies like Quantinuum already working to embed these capabilities into their InQuanto chemistry platform [4].

The theoretical framework of intrinsic quantum codes suggests that diverse quantum error correction schemes across different hardware platforms may be unified through underlying symmetry principles [5]. This insight could dramatically streamline the development of fault-tolerant quantum computation by allowing researchers to design error correction strategies in abstract mathematical spaces before implementing them in physical systems. As these advances converge, the field moves closer to realizing practical quantum advantage in chemical simulation, potentially within the next decade according to industry roadmaps that target utility-scale quantum computing by the early 2030s [4].

Dirac's Conundrum, once considered an fundamental limitation of computational quantum chemistry, is now being addressed through the powerful combination of quantum algorithms and error correction techniques. The recent experimental demonstrations of error-corrected quantum chemistry calculations represent critical milestones on the path to fault-tolerant quantum computation for chemical applications. While significant challenges remain in scaling these approaches to larger, chemically relevant systems, the rapid progress in both hardware capabilities and algorithmic sophistication suggests that practical quantum advantage in chemistry may be within reach. The emergence of theoretical frameworks such as intrinsic quantum codes further accelerates this progress by providing unifying principles that transcend specific hardware implementations. As these developments continue to mature, they promise to transform computational quantum chemistry from a field constrained by approximations to one capable of predictive accuracy across a broad range of chemical systems.

Why NISQ-Era Quantum Chemistry Reaches Its Limits

Quantum computing holds the profound potential to revolutionize chemistry by providing a native platform for simulating quantum mechanical systems. Molecules, being quantum objects themselves, are governed by effects like superposition and entanglement, which quantum computers are inherently designed to process [7]. This capability promises to unlock accurate simulations of complex molecular systems, chemical reactions, and materials properties that are beyond the reach of classical computational methods, which often rely on approximations [8]. Such advancements could dramatically accelerate developments in drug discovery, battery technology, and fertilizer manufacture [9].

However, this promise remains largely unfulfilled in the current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era. NISQ processors, while a remarkable engineering achievement, are characterized by a lack of fault tolerance, typically containing between 50 and 1,000 physical qubits that are susceptible to noise, decoherence, and gate errors [10]. This article examines the fundamental limitations that these constraints impose on quantum chemistry applications, framing the discussion within the broader research context of developing intrinsically fault-tolerant algorithmic approaches. We will explore how noise and limited resources curtail the depth and complexity of feasible quantum simulations, preventing researchers from tackling the very problems that would demonstrate a clear quantum advantage.

The NISQ Landscape and Its Core Challenges

The NISQ era is defined by quantum processors that, despite their increasing qubit counts, are too noisy and insufficiently large to implement continuous quantum error correction [10]. The term, coined by John Preskill, describes a period where quantum devices have a "quantum volume" substantial enough to perform tasks that are challenging for classical computers to simulate directly, yet not reliable enough for guaranteed correct results [10] [11]. On these devices, gate fidelities for one- and two-qubit operations typically hover around 99-99.5% and 95–99% respectively [10]. While these figures represent impressive progress, the errors they represent accumulate rapidly during computation.

The central challenge of NISQ computing is the exponential scaling of noise with circuit depth. Each gate operation introduces a small amount of noise, and as more gates are applied, this noise accumulates exponentially, eventually overwhelming the quantum information being processed [9] [10]. This places a severe constraint on the number of sequential operations—the circuit depth—that can be performed before the output becomes a "structureless stream of random numbers" [9]. Current NISQ devices can typically run only tens to a few hundred gates before their output is no longer reliable or useful, even with the application of error mitigation techniques [9]. This fragile computational environment fundamentally limits the complexity of quantum algorithms that can be executed, creating a signifcant barrier for practical quantum chemistry applications.

Quantitative Limits: Resource Estimates for Chemical Applications

To understand why NISQ devices are inadequate for transformative quantum chemistry, it is essential to compare their capabilities with the resource requirements of commercially relevant chemical applications. These applications require executing quantum circuits with millions to trillions of gates acting on hundreds to thousands of logical (error-corrected) qubits [9]. The following table summarizes the resource estimates for key transformative applications, highlighting the immense gap between requirement and reality.

Table 1: Resource Requirements for Transformative Quantum Chemistry Applications

| Application | Number of Gates | Qubit Counts | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific Breakthrough | 10,000,000+ | 100+ | Fundamental research [9] |

| Fertilizer Manufacture | 1,000,000,000+ | 2,000+ | Simulating nitrogen fixation catalysts (e.g., FeMoco) [9] [8] |

| Drug Discovery | 1,000,000,000+ | 1,000+ | Modelling complex biomolecules (e.g., Cytochrome P450) [9] [8] |

| Battery Materials | 10,000,000,000,000+ | 2,000+ | Simulating novel materials and ion dynamics [9] |

The disconnect between these requirements and NISQ capabilities is stark. For instance, while industrial researchers aim to simulate complex metalloenzymes like cytochrome P450 or the iron-molybdenum cofactor (FeMoco) for nitrogen fixation, these tasks are estimated to require millions of physical qubits [8]. In 2021, Google estimated that about 2.7 million physical qubits would be needed to model FeMoco, a figure that more recent innovations have reduced to just under 100,000—still far beyond the scale of today's hardware [8]. This gap of several orders of magnitude in both qubit counts and gate depths illustrates why NISQ-era devices cannot yet run the deep, complex circuits required for impactful quantum chemistry.

Experimental Protocols in the NISQ Era

Primary Algorithmic Approaches

Given the hardware constraints, researchers have developed specialized algorithms designed to function within NISQ's limited circuit depths. The two most prominent approaches are the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA), both of which employ a hybrid quantum-classical structure [10].

- Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE): This algorithm is designed to find the ground-state energy of a molecular system, a fundamental task in quantum chemistry. It operates on the variational principle of quantum mechanics. A parameterized quantum circuit, called an ansatz ( |\psi(\theta)\rangle ), is used to prepare a trial wavefunction on the quantum processor. The energy expectation value ( E(\theta) = \langle\psi(\theta)|\hat{H}|\psi(\theta)\rangle ) of the molecular Hamiltonian ( \hat{H} ) is measured. A classical optimizer then iteratively adjusts the parameters ( \theta ) to minimize this energy, providing an upper bound to the true ground state energy [10].

- Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA): While more often applied to combinatorial problems, QAOA's structure is relevant for chemistry. It constructs a quantum circuit with ( p ) layers, each consisting of two evolution operators: one generated by a problem-specific cost Hamiltonian ( \hat{H}C ) and another by a mixing Hamiltonian ( \hat{H}M ). The quantum state is prepared as ( |\psi(\gamma, \beta)\rangle = \prod{j=1}^{p} e^{-i\beta{j}\hat{H}{M}} e^{-i\gamma{j}\hat{H}{C}} |+\rangle^{\otimes n} ). A classical optimizer then tunes the parameters ( {\gamma{j}, \beta{j}} ) to minimize the expectation value ( \langle \psi(\gamma, \beta) | \hat{H}C | \psi(\gamma, \beta) \rangle ) [10].

Error Mitigation Techniques

Since full quantum error correction is not feasible on NISQ devices, researchers rely on post-processing techniques to extract more accurate results from noisy computations. The following table details the key "research reagent solutions" used in NISQ experiments to manage errors.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions: Key Error Mitigation Techniques for NISQ Chemistry

| Technique | Function | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | Artificially amplifies circuit noise (e.g., by stretching gate pulses) and extrapolates results back to the zero-noise limit [10]. | Assumes noise scales predictably; performance degrades in high-error regimes. |

| Symmetry Verification | Exploits inherent conservation laws (e.g., particle number) to detect errors. Measurement outcomes that violate the symmetry are discarded or corrected [10]. | Only applicable to problems with known symmetries; leads to data discard. |

| Probabilistic Error Cancellation | Reconstructs ideal quantum operations as linear combinations of noisy operations that can be physically implemented [10]. | Sampling overhead typically scales exponentially with error rates and circuit size. |

These mitigation techniques inevitably increase the number of circuit repetitions (measurement shots) required, with overheads ranging from 2x to 10x or more, creating a fundamental trade-off between accuracy and experimental time [10]. A critical workflow in NISQ experiments involves the iterative application of these techniques, as visualized below.

This workflow underscores the tight coupling between the quantum hardware and classical co-processor, which is necessary to navigate the noisy landscape of current devices.

The Path Beyond NISQ: Towards Fault Tolerance

The limitations of the NISQ era are catalyzing the transition towards fault-tolerant quantum computing (FTQC). The core idea of FTQC is to encode information into logical qubits, which are composed of many noisy physical qubits connected and controlled in such a way that errors can be continuously detected and corrected [9]. This process creates a reliable computational unit from unreliable parts, forming the foundation for scalable, general-purpose quantum computing.

Recent experimental breakthroughs indicate that this transition is underway. In mid-2025, Quantinuum reported crossing a key threshold by demonstrating a universal, fully fault-tolerant quantum gate set with repeatable error correction [12]. Their research achieved a "break-even" point for non-Clifford gates—a critical milestone where the error-corrected logical gate outperforms the best available physical gate of the same type [12]. For example, they implemented a fault-tolerant controlled-Hadamard gate with a logical error rate of ( 2.3 \times 10^{-4} ), which was lower than the physical gate's baseline error of ( 1 \times 10^{-3} ) [12]. This provides experimental evidence that error correction can work as intended and is a vital precursor to scaling.

This progress is paving the way for the Intermediate-Scale Quantum (ISQ) era, a regime that sits between NISQ and full fault-tolerance [11]. ISQ devices would feature a limited number of error-corrected logical qubits, enabling circuit depths orders of magnitude larger than what is possible today, but still falling short of the full scale required for the most transformative applications [11]. The relationship between these eras and the role of error correction is summarized in the following diagram.

Leading companies have published ambitious roadmaps targeting this transition, with IBM aiming to deliver a large-scale fault-tolerant system by 2029, and Quantinuum targeting universal fault-tolerance by the same period [10]. The demonstration of key technological milestones suggests that the community is steadily progressing from the intrinsic limitations of NISQ hardware toward a more robust and capable quantum future.

The NISQ era has been a period of remarkable experimental progress and algorithmic innovation, proving that quantum devices can be controlled and utilized for non-trivial tasks. However, for the field of quantum chemistry, its limits are stark and intrinsic. The competing constraints of exponential noise scaling, low gate fidelities, and insufficient qubit counts create a fundamental barrier that prevents NISQ devices from executing the deep, million-to-trillion-gate circuits required for simulating industrially relevant molecules and materials.

The path forward lies in the continued development of fault-tolerant quantum computing. The recent demonstration of logical gates that surpass their physical counterparts in fidelity provides a tangible signal that the field is moving beyond the NISQ paradigm [12]. For researchers in quantum chemistry, this transition cannot come soon enough. It will unlock the true potential of quantum simulation, enabling the precise modeling of complex chemical systems and ultimately delivering on the long-awaited promise of transformative applications in drug discovery, materials science, and beyond.

The simulation of complex molecular systems represents one of the most promising applications of quantum computing, with potential breakthroughs in drug discovery and materials science. However, this potential remains largely theoretical due to the fundamental challenge of quantum noise and decoherence. While Quantum Error Correction (QEC) provides a pathway to fault tolerance, traditional approaches impose prohibitive computational overhead that threatens to render quantum chemistry simulations impractical [13]. The emerging paradigm of Algorithmic Fault Tolerance (AFT) represents a fundamental shift in strategy—from treating error correction as a separate hardware-level process to embedding it intrinsically within the algorithmic flow itself. This approach is particularly suited for quantum chemistry algorithms, where it leverages the inherent structure of quantum simulations to achieve dramatic reductions in resource overhead while maintaining exponential error suppression [14].

For quantum chemists investigating biologically crucial systems like the cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in drug metabolism or the FeMoco catalyst essential for nitrogen fixation, AFT offers a credible path to practical simulation. These molecular systems contain strongly correlated electrons that defy accurate classical simulation but could be tractable on error-corrected quantum computers with significantly reduced overhead [15]. By reframing fault tolerance as an algorithmic concern rather than purely a hardware challenge, AFT aligns with the broader thesis that intrinsic fault tolerance in quantum chemistry algorithms can emerge from co-designing applications with error-corrected hardware capabilities.

Technical Foundation: Deconstructing the AFT Framework

Core Principles and Mechanisms

Algorithmic Fault Tolerance achieves its performance gains through a fundamental reimagining of how and when error correction occurs during quantum computation. Traditional QEC methods, particularly those using surface codes, typically require d rounds of syndrome extraction per logical operation (where d is the code distance), creating a significant runtime bottleneck [16]. AFT challenges this paradigm by demonstrating that only a constant number of syndrome extractions (typically just one) is sufficient when error correction is considered across the entire algorithm rather than at the individual operation level.

The AFT framework rests on two foundational pillars:

Transversal Operations: Logical gates are applied in parallel across matched sets of physical qubits within the encoded logical block. This parallelization ensures that any single-qubit error remains localized and cannot propagate through the quantum circuit, dramatically simplifying error detection and correction. The inherent fault-tolerance of transversal gates stems from their restriction of error propagation—a single physical fault results in at most one fault in each code block [16] [14].

Correlated Decoding: Instead of analyzing each syndrome measurement round in isolation (as in traditional QEC), AFT employs a joint decoder that processes the pattern of all syndrome measurements collected throughout the algorithm's execution. This holistic approach allows the decoder to identify error patterns that would be undetectable when examining individual syndrome extractions separately, effectively realizing the code's full error-correcting capability without the conventional overhead of repeated measurements [17] [16].

Theoretical Underpinnings and Formal Guarantees

The mathematical foundation of AFT is formalized in what researchers term the "Algorithmic Fault Tolerance Theorem," which states that for a transversal Clifford circuit with low-noise magic state inputs and feed-forward operations implementable with Calderbank-Shor-Steane (CSS) Quantum Low-Density Parity-Check (QLDPC) codes of increasing distance d, there exists a threshold physical error rate pth such that if the physical error rate p < pth, the protocol can perform constant-time logical operations with only a single syndrome extraction round while suppressing the total logical error rate as P_L = exp(-Θ(d)) [14].

This theoretical guarantee of exponential error suppression with only constant-time overhead represents a breakthrough in fault-tolerant quantum computing theory. It validates that the deviation of the logical output distribution from the ideal error-free distribution can be made exponentially small in the code distance d, despite using significantly fewer syndrome extraction rounds than traditional approaches [14]. The framework applies to a broad class of quantum error-correcting codes, including the popular surface code with magic state inputs and feed-forward operations, making it particularly relevant for near-term fault-tolerant implementations [18].

Comparative Analysis: AFT vs. Traditional QEC

Performance and Resource Metrics

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison Between Traditional QEC and AFT

| Parameter | Traditional QEC | Algorithmic Fault Tolerance | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syndrome Extraction Rounds per Operation | d rounds (typically 25-30) [16] | Constant (typically 1-2 rounds) [16] | 10-100× reduction [13] |

| Time Overhead | Proportional to code distance (Θ(d)) [14] | Constant time (Θ(1)) [14] | Factor of d (often ~30×) [17] |

| Logical Clock Speed | Significantly slower than physical clock speed (often 30× slower) [19] | Competitive with physical clock speed [19] | 10-100× faster execution [17] |

| Error Suppression | Exponential in d (with d rounds) [16] | Exponential in d (with constant rounds) [16] | Equivalent protection with less overhead [16] |

| Space-Time Volume per Logical Operation | Θ(d³) [14] | Orders of magnitude reduction [14] | Significant direct reduction [14] |

| Decoder Complexity | Local, frequent decoding [16] | Global, correlated decoding [16] | Increased classical processing [16] |

Hardware Implications and Platform Compatibility

The practical implementation of AFT reveals distinctive hardware requirements and compatibility considerations across different quantum computing platforms:

Neutral-Atom Quantum Computers: AFT is particularly well-suited for reconfigurable neutral-atom architectures due to their inherent capacity for parallel operations and dynamic qubit repositioning [13]. The "all-to-all" connectivity available in these systems enables efficient implementation of transversal gates across multiple qubits simultaneously. Furthermore, the identical nature of neutral-atom qubits and their operation at room temperature (without cryogenic requirements) provide additional advantages for scalable AFT implementation [17].

Superconducting Qubit Systems: While traditional superconducting architectures face challenges with fixed connectivity and limited parallel operation capabilities, recent innovations show promise for AFT adaptation. Google's Willow quantum chip, featuring 105 superconducting qubits, has demonstrated exponential error reduction as qubit counts increase—a critical prerequisite for effective AFT implementation [20].

Trapped-Ion and Photonic Platforms: The AFT framework's applicability extends beyond neutral-atom systems, with research demonstrations on trapped-ion computers showing logical error rates 22 times better than physical qubit error rates [19]. The fundamental principles of transversal operations and correlated decoding can be adapted across platforms, though optimal implementation strategies will vary based on hardware-specific capabilities and constraints.

AFT in Practice: Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Experimental Validation and Benchmarking

Researchers at QuEra, Harvard, and Yale have established rigorous experimental protocols to validate AFT performance claims through a combination of theoretical proof and circuit-level simulations:

Simulation Methodology: The validation approach employs comprehensive circuit-level simulations of the AFT protocol under realistic noise models. These simulations incorporate the basic model of fault tolerance, utilizing the local stochastic noise model where depolarizing errors are applied to each data qubit after every syndrome extraction round, with measurement errors affecting each syndrome result [14]. The probability of error events decays exponentially with the weight of the error, and the methodology can be generalized to circuit-level noise by leveraging the bounded error propagation for constant-depth syndrome extraction circuits in QLDPC codes [14].

Decoder Implementation: The experimental protocol assumes a most likely error (MLE) decoder and fast classical computation capabilities. The correlated decoding process analyzes the combined pattern of all syndrome data collected up to the point of logical operation, rather than treating each syndrome measurement round in isolation [16]. This approach shifts computational complexity from the quantum hardware to classical decoding software, which performs global error correction across the entire algorithm or large algorithm segments [16].

Performance Metrics: The key metrics evaluated include logical error rate versus physical error rate, algorithm execution time reduction, and space-time volume efficiency. Researchers have demonstrated through these simulations that the AFT approach achieves fault tolerance with competitive error thresholds compared to conventional multi-round methods, even when simulating complete state distillation factories essential for universal quantum computation [14].

Diagram 1: AFT Experimental Workflow (55 characters)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for AFT Implementation

Table 2: Essential Components for AFT Experimental Research

| Component | Function in AFT Implementation | Representative Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| CSS QLDPC Codes | Provides the foundational error-correcting code structure supporting transversal operations | Surface codes, color codes [14] |

| Syndrome Extraction Circuit | Measures stabilizer operators to detect errors without collapsing quantum state | Ancilla qubits coupled to data qubits, single extraction round per operation [16] |

| Correlated Decoder | Classical processing unit that performs joint analysis of syndrome data across algorithm execution | Most Likely Error (MLE) decoder, global analysis capability [16] [14] |

| Magic State Distillation Factory | Produces high-fidelity non-Clifford states required for universal quantum computation | Logical-level magic state distillation with 2D color codes for d=3 and d=5 [19] |

| Transversal Gate Implementation | Executes parallel operations across qubit blocks while containing error propagation | Neutral-atom arrays with dynamic reconfigurability [17] |

| Hardware Architecture | Physical platform supporting parallel operations and high connectivity | Reconfigurable atom arrays, superconducting processors with all-to-all connectivity [17] [20] |

| GSK3-IN-4 | GSK3-IN-4, CAS:370588-29-7, MF:C18H20N4O, MW:308.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Oleic acid-d2 | Oleic acid-d2, CAS:5711-29-5, MF:C18H34O2, MW:284.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application to Quantum Chemistry: Enabling Practical Molecular Simulation

Resource Estimation for Molecular Systems

The implementation of AFT has profound implications for quantum chemistry applications, particularly in simulating biologically significant molecular systems that defy classical computational approaches:

Table 3: AFT Resource Requirements for Key Molecular Simulations

| Molecular System | Significance | Logical Qubits Required | Estimated Runtime | Key Breakthrough with AFT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytochrome P450 | Drug metabolism enzyme critical for pharmaceutical development | ~1,500 logical qubits [15] | 99 hours (with cat qubits) [15] | 27× reduction in physical qubit requirements compared to traditional QEC [15] |

| FeMoco (Nitrogenase) | Biological nitrogen fixation catalyst for sustainable agriculture | ~1,500 logical qubits [15] | 78 hours (with cat qubits) [15] | Potential to simulate previously intractable strongly correlated electron systems [15] |

| RSA-2048 Factoring | Cryptographic relevance (Shor's algorithm) | 19 million physical qubits [16] | 5.6 days (vs. months with traditional QEC) [16] | 50× speedup versus previous fault-tolerance approaches [16] |

Implementation Workflow for Quantum Chemistry Algorithms

Diagram 2: AFT Quantum Chemistry Pipeline (48 characters)

The application of AFT to quantum chemistry follows a structured workflow that begins with problem formulation and extends through to solution verification. For molecular simulation problems such as calculating the ground state energy of cytochrome P450 or FeMoco, the process initiates with mapping the electronic structure problem to a qubit representation [15]. The quantum algorithm (typically Quantum Phase Estimation for ground state problems) is then compiled with explicit consideration of AFT principles, identifying opportunities for transversal operations and minimal syndrome extraction [21].

During execution, the algorithm proceeds with constant-time syndrome extraction interleaved between transversal logical operations, collecting partial error information without halting computation. Only upon completion of the algorithm or major checkpoints does the correlated decoder perform a comprehensive analysis of the accumulated syndrome data, effectively distinguishing true chemical signatures from error-induced artifacts [14]. This approach is particularly valuable for quantum chemistry applications where the final measurement (such as energy readout) matters more than intermediate state correctness, allowing AFT to deliver accelerated computation without sacrificing the accuracy essential for predictive chemical modeling.

Future Directions and Research Challenges

While Algorithmic Fault Tolerance represents a substantial advancement in practical quantum computing, several research challenges remain before widespread adoption in quantum chemistry applications:

Decoder Optimization: The correlated decoding process requires sophisticated classical algorithms capable of processing large volumes of syndrome data across temporal dimensions. Research into efficient decoding algorithms, potentially leveraging machine learning techniques, will be essential for managing the computational complexity of AFT as algorithm scale increases [19].

Hardware-Co-Design: Optimal implementation of AFT requires continued hardware development, particularly in platforms offering high connectivity and parallel operation capabilities. Neutral-atom systems show particular promise, but further work is needed to improve gate fidelities and operation speeds in these architectures [17] [13].

Application-Specific Optimization: The greatest benefits of AFT will likely emerge from co-design approaches where quantum chemistry algorithms are developed specifically to maximize transversal operations and minimize error correction overhead. This includes exploring alternative algorithm formulations that naturally align with AFT principles and identifying molecular simulation problems most amenable to the AFT approach [21].

The integration of Algorithmic Fault Tolerance with specialized qubit technologies such as cat qubits promises additional resource reductions. Recent research suggests that combining AFT with cat qubits could achieve up to 27× reduction in physical qubit requirements for complex molecular simulations like FeMoco and cytochrome P450 [15]. As these advancements mature, AFT is positioned to fundamentally accelerate the timeline for practical quantum advantage in quantum chemistry, potentially bringing previously intractable drug discovery and materials science problems within reach of quantum computational solutions.

In the pursuit of fault-tolerant quantum computing, transversal operations and correlated decoding have emerged as a foundational framework for significantly reducing the time overhead associated with quantum error correction (QEC). This paradigm, formalized as Algorithmic Fault Tolerance (AFT), leverages the deterministic propagation of errors through transversal gates and employs joint decoding of syndromes across logical algorithm layers. By shifting the complexity of error correction from the hardware execution to the classical decoding process, this approach enables logical error rates to decay exponentially with code distance (d) while slashing the runtime overhead from (O(d)) to (O(1)) for Clifford circuits [22] [17]. For researchers in quantum chemistry and drug development, these advances promise to accelerate the path to practical quantum simulation of molecular systems by making deep, error-corrected quantum algorithms computationally feasible.

The implementation of quantum error correction is widely considered a prerequisite for scalable, large-scale quantum computation. However, its substantial space-time overhead has historically been a major bottleneck. Traditional QEC schemes for a code of distance (d) require approximately (d) rounds of noisy syndrome extraction between logical gate operations to control logical error rates, dramatically inflating the runtime of logical algorithms [17]. The core innovation of AFT lies in its holistic treatment of an entire logical algorithm as a single unit of fault tolerance, rather than focusing on the error-correcting capabilities of individual gates in isolation. This approach is particularly suited for reconfigurable neutral-atom quantum processors, where the inherent flexibility of qubit arrays and the natural identicality of atomic qubits facilitate the implementation of parallel, transversal logical gates [17]. For the field of quantum chemistry, where algorithms for molecular energy calculation often involve deep circuits, this framework can potentially reduce the execution time of error-corrected computations by factors of 10 to 100, bringing complex simulations of pharmaceutical compounds within practical reach [17].

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundation

Transversal Operations: Containing Error Propagation

A transversal gate is a logical quantum operation implemented by performing a series of parallel, independent physical gates on the constituent physical qubits of the logical codeblocks. Its defining characteristic is that it prevents the propagation of errors from a single faulty physical component from cascading into multiple errors within a single logical codeblock.

- Mechanism and Implementation: In a transversal implementation of a logical entangling gate, such as a CNOT, the operation is executed as a series of physical CNOT gates between corresponding physical qubits in two logical codeblocks. A single physical error on one qubit can only propagate to a single qubit in the target codeblock, preserving the locality of errors. This containment is crucial as it ensures that the error structure remains simple and decodable, preventing the creation of complex, correlated error patterns that would challenge the decoder [22] [17].

- Role in AFT: Transversality is a key property for many stabilizer codes, including the surface code. By constructing logical circuits primarily from transversal gates, the problem of error correction is simplified. The AFT framework capitalizes on this by showing that for a broad class of quantum algorithms, one can safely execute each logical layer with just a single round of syndrome extraction when combined with a sufficiently powerful decoder, a drastic reduction from the (d) rounds typically required [17].

Correlated Decoding: Exploiting Structured Error Information

Correlated decoding is the complementary classical decoding strategy that processes syndrome information collected over multiple stages of a logical algorithm simultaneously, rather than performing independent, round-by-round decoding.

- Principle of Operation: During a transversal gate, errors propagate in a deterministic and known pattern. A correlated decoder leverages this prior knowledge of the circuit structure. It does not treat each syndrome measurement round as an independent snapshot but instead analyzes the entire history of syndrome data from before, during, and after a transversal gate to identify the most likely chain of physical errors that could have produced the observed pattern [22].

- Decoder Types and Performance: Research has explored different decoders offering trade-offs between computational runtime and accuracy [22].

- Maximum-Likelihood Decoders: These identify the most probable error chain given the full syndrome history and the circuit structure, offering high accuracy but potentially at a higher computational cost.

- Heuristic/Approximate Decoders: These provide a more computationally efficient solution by leveraging the known structure of error propagation, making them practical for real-time decoding in larger systems while still maintaining a significant performance advantage over independent decoding.

The synergy between these two principles is powerful: transversal gates ensure errors propagate in a predictable, localized manner, and correlated decoding uses this predictability to make more accurate inferences about which errors actually occurred.

Experimental Validation and Performance Analysis

Recent experimental and numerical studies have validated the significant performance gains offered by combining transversal operations with correlated decoding.

Numerical Performance Results

Simulations demonstrate that correlated decoding substantially improves the performance of both Clifford and non-Clifford transversal entangling gates [22]. The core quantitative improvement is the reduction of syndrome extraction rounds between transversal gates from (O(d)) to (O(1)), leading to an overall reduction in the spacetime overhead of deep logical Clifford circuits [22].

Table 1: Comparison of Standard Fault Tolerance vs. AFT Framework

| Feature | Standard Fault Tolerance | Algorithmic Fault Tolerance (AFT) |

|---|---|---|

| Syndrome Rounds/Gate | (O(d)) | (O(1)) |

| Time Overhead | High | Reduced by factor of ~d (e.g., 30x or more) [17] |

| Decoding Strategy | Independent, round-by-round | Correlated, across algorithm steps |

| Error Propagation | Complex and uncontrolled | Deterministic and contained via transversal gates |

| Logical Error Rate | Exponential decay with (d) | Exponential decay with (d) maintained [17] |

Resource Analysis for Quantum Algorithms

A companion study applied the AFT framework to Shor's factoring algorithm, providing a concrete resource estimate [17]. When mapped onto reconfigurable neutral-atom architectures, this approach demonstrated 10–100x reductions in execution time for large-scale logical algorithms. This order-of-magnitude improvement is critical for making lengthy quantum chemistry simulations, such as phase estimation for complex molecules, computationally tractable.

Experimental Protocol for Validating AFT Performance

The following methodology outlines the key steps for experimentally benchmarking the performance of the AFT framework on a quantum processing unit.

Objective: To quantify the reduction in logical error rate and the required number of syndrome rounds achieved by using transversal gates with correlated decoding, compared to a standard fault-tolerant approach.

Materials & Setup:

- A quantum processor capable of executing the desired QEC code (e.g., a surface code patch) and implementing the necessary transversal gate set.

- Classical control system to coordinate quantum circuit execution.

- High-performance classical computing resource to run the correlated decoder.

Procedure:

- Circuit Selection: Choose a benchmark logical algorithm, such as a deep Clifford circuit or a simplified quantum simulation circuit like a Trotter step for a molecular Hamiltonian.

- Baseline Measurement:

- Implement the benchmark circuit using standard fault-tolerant methods, interleaving (d) rounds of syndrome extraction between logical gates.

- Use a standard matching decoder for each syndrome round independently.

- Execute the circuit multiple times to gather statistics and compute the final logical error rate.

- AFT Measurement:

- Implement the identical benchmark circuit using transversal gates where possible.

- Interleave only a single round of syndrome extraction between logical gates.

- Collect all syndrome data throughout the circuit execution.

- Process the complete syndrome history using a correlated decoder to infer and correct errors.

- Execute the circuit the same number of times to compute the final logical error rate.

- Analysis: Compare the logical error rates and the total execution times (or number of QEC cycles) between the baseline and AFT implementations.

Key Metrics:

- Logical Error Rate per Gate or per Algorithm.

- Algorithm Success Probability.

- Total Number of QEC Cycles / Execution Time.

- Classical Decoder Runtime.

Implementation Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The experimental and decoding workflow for AFT involves a tight feedback loop between the quantum hardware and the classical decoder, with information from the quantum circuit directly informing the decoding graph. The following diagram illustrates this integrated process.

Workflow for AFT with Correlated Decoding

The correlated decoder's function relies on a decoding graph that is dynamically generated based on the quantum algorithm's circuit. The graph structure below represents how errors propagate through a transversal CNOT gate, which the decoder uses to find the most likely error chain.

Decoding Graph with Transversal Gate Correlation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key "research reagents" – the core components and methodologies required to implement and experiment with the AFT framework.

Table 2: Essential Components for AFT Research and Implementation

| Component / Reagent | Function & Role in AFT Framework |

|---|---|

| Reconfigurable Neutral-Atom Array | The physical platform. Provides identical qubits, dynamic connectivity, and room-temperature operation, enabling efficient mapping of transversal architectures and qubit shuttling for gate execution [17]. |

| Surface Code (or similar QEC Code) | The logical substrate. A topological QEC code that supports a set of transversal gates (e.g., Clifford gates) and provides the structure for syndrome extraction and the exponential suppression of logical errors with distance (d) [17]. |

| Transversal Gate Set | The logical operational units. A set of gates (e.g., CNOT, Hadamard) implemented transversally to contain error propagation, forming the building blocks of the logical algorithm [22] [17]. |

| Stabilizer Measurement Circuit | The error-sensing apparatus. A hardware implementation for extracting the syndrome of the QEC code without introducing excessive noise, typically run once per logical gate layer in AFT [22]. |

| Correlated Decoder | The classical brain. A software decoder that analyzes the full history of syndrome data in the context of the known circuit structure (especially transversal gates) to identify the most likely error chain, enabling the reduction in syndrome rounds [22] [17]. |

| Algorithmic Fault Tolerance (AFT) Framework | The overarching protocol. The theoretical and practical framework that integrates transversal gates and correlated decoding to reduce the time overhead of error-corrected logical algorithms [17]. |

| (E/Z)-BCI | (E/Z)-BCI, MF:C22H23NO, MW:317.4 g/mol |

| BAY-474 | BAY-474, MF:C17H15N5, MW:289.33 g/mol |

For researchers in quantum chemistry and drug development, the promise of quantum computing to simulate molecular interactions with unparalleled accuracy is often tempered by a formidable obstacle: hardware-level errors that disrupt coherent quantum dynamics. The path to practical quantum advantage requires computational platforms that offer not just scale, but intrinsic resilience. Among competing quantum technologies, neutral-atom platforms, which use individual atoms as qubits trapped by optical tweezers, are emerging as a uniquely suited architecture. Their inherent physical properties—qubit uniformity, long coherence times, and flexible, dynamic connectivity—provide a natural foundation for fault tolerance. This technical guide explores the core attributes of neutral-atom quantum computers, detailing how recent breakthroughs in Algorithmic Fault Tolerance (AFT) are leveraging these intrinsic advantages to create a robust framework for quantum simulation. For scientists modeling complex molecular systems or reaction pathways, these developments signal a credible and accelerated path toward reliable, large-scale quantum computation.

Core Technical Advantages of the Neutral-Atom Platform

The neutral-atom approach encodes quantum information in the internal energy states of individual atoms, such as Rubidium or Strontium, which are laser-cooled and suspended in vacuum chambers. This methodology delivers several foundational benefits that are critical for executing deep quantum circuits, especially in quantum chemistry applications.

- Qubit Uniformity and Scalability: Unlike manufactured qubits which can suffer from minor variations, every atom of a specific isotope is intrinsically identical, providing a perfectly uniform set of qubits. This inherent uniformity simplifies the calibration and control processes essential for scaling. Systems with several hundred qubits have already been demonstrated, with a clear path to further scaling [17] [23].

- Long Coherence Times: The quantum states used to encode information in neutral atoms are naturally isolated from the environment, leading to long coherence times. This allows quantum information to be retained for longer durations, which is a critical advantage for complex quantum algorithms, such as those required for molecular energy calculations [24].

- Dynamic, Reconfigurable Arrays: Optical tweezers allow atoms to be rearranged into arbitrary two-dimensional arrays during a computation. This "programmable connectivity" means the hardware can be dynamically reconfigured to match the interaction topology of a specific quantum algorithm or molecule, minimizing the need for costly swap operations and reducing circuit depth [17] [23].

- High-Fidelity Entangling Gates: A universal quantum computer requires high-fidelity two-qubit gates. Neutral-atom platforms leverage the Rydberg blockade effect to implement fast and strong entangling gates. When one atom is excited to a high-energy Rydberg state, it prevents neighboring atoms within a certain radius from being excited, enabling controlled quantum operations [25].

Table 1: Key Figures of Merit for Neutral-Atom Quantum Processors

| Characteristic | Representative Performance/Feature | Implication for Quantum Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Qubit Count | 256 - 448 qubits in recent demonstrations [23] [26] | Enables simulation of larger, more chemically relevant molecular active spaces. |

| Single-Qubit Gate Fidelity | >0.999 [25] | Reduces error accumulation in state preparation and single-qubit rotations within algorithms. |

| Qubit Uniformity | Perfectly identical qubits (natural atoms) [17] | Simplifies calibration and ensures consistent performance across the entire processor. |

| Operating Temperature | Room-temperature (support infrastructure) [17] | Reduces system complexity and cost compared to cryogenic alternatives. |

The Algorithmic Fault Tolerance (AFT) Breakthrough

A pivotal recent advancement that capitalizes on the neutral-atom platform's strengths is the development of Transversal Algorithmic Fault Tolerance (AFT). Introduced in a September 2025 Nature paper from QuEra, Harvard, and Yale, this framework directly addresses one of the most significant bottlenecks in fault-tolerant quantum computing: the time overhead of quantum error correction (QEC) [17].

Quantum error correction protects fragile quantum information by encoding a single logical qubit into many physical qubits. The level of protection is quantified by the code distance (d). In standard QEC schemes, performing a single logical operation requires d rounds of "syndrome extraction" measurements to detect and correct errors, dramatically inflating the algorithm's runtime [17].

The AFT framework slashes this overhead by a factor of d (often 30 or more) through a powerful synthesis of two techniques:

- Transversal Operations: Logical gates are applied in parallel across corresponding physical qubits in different logical blocks. This design ensures that any single-physical-qubit error remains contained and cannot cascade into a complex, undetectable failure, thus simplifying the error correction process [17].

- Correlated Decoding: Instead of analyzing each round of syndrome measurement in isolation, a joint "correlated decoder" analyzes the pattern of all measurements collected during the algorithm's execution. This holistic approach, often powered by machine learning, allows the system to maintain an exponentially low logical error rate with far fewer intermediate checks [17] [26].

This breakthrough is particularly potent when mapped onto reconfigurable neutral-atom arrays. The flexible connectivity allows for efficient physical arrangements of atoms that are optimal for implementing transversal gates and syndrome extraction, leading to simulated 10–100× reductions in execution time for large-scale logical algorithms like Shor's algorithm [17]. For a quantum chemist, this translates to the feasible simulation of complex molecular systems in hours instead of months.

Diagram 1: AFT vs. Traditional QEC Workflow. This flowchart contrasts the streamlined AFT approach with the high-overhead traditional quantum error correction process.

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

The practical realization of these concepts was demonstrated in a landmark 2025 experiment, which showed repeatable rounds of quantum error correction on a neutral-atom processor [26]. The following section details the methodology and essential tools that enabled this achievement.

Detailed Experimental Methodology

The protocol for sustained error correction and logical operation on a neutral-atom processor involves a sequence of precise steps [26]:

- Array Preparation and Initialization: A cloud of Rubidium-85 atoms is laser-cooled to micro-Kelvin temperatures in a magneto-optical trap within a vacuum chamber. Optical tweezers (highly focused laser beams) are used to trap and arrange individual atoms into a customizable 2D array of up to 288 atoms for the error correction code.

- Qubit Encoding: The fiducial ground state (

|0>) and a long-lived hyperfine state (|1>) of each atom's valence electron are used to define the physical qubit states. All atoms are optically pumped to initialize the|0>state. - Surface Code Layout: The atoms are partitioned into data qubits and ancillary (measurement) qubits, arranged in a checkerboard pattern to implement the surface code, a leading quantum error-correcting code.

- Stabilizer Measurement Cycle (Syndrome Extraction):

- Rydberg-Mediated Entanglement: Laser pulses are applied to entangle data qubits with their neighboring ancillary qubits via the Rydberg blockade mechanism.

- Parallel Measurement: The state of the ancillary qubits is read out using resonance fluorescence, which indirectly reveals information about errors on the data qubits (the "syndrome") without collapsing the data qubits' quantum state. This cycle is repeated multiple times without resetting the system.

- Classical Decoding and Active Correction: A machine learning-based decoder running on a classical GPU processes the sequence of syndrome measurements. The correlated decoder identifies the most probable error chain and instructs the system to apply a corrective operation.

- Logical Gate Execution: Parallel, transversal entangling gates (e.g., CNOT) are applied across corresponding physical qubits in different logical blocks. Lattice surgery techniques are used to merge and split logical qubits for more complex operations.

- Atom Loss Mitigation: The system employs "superchecks" and real-time detection to identify and handle the loss of atoms from the trap, a common challenge in neutral-atom systems. Affected code blocks can be dynamically reconfigured or reset.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Experimental Components for Neutral-Atom Quantum Processing

| Component / "Reagent" | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Rubidium-85 Atoms | The physical substrate for qubits. Chosen for its single valence electron and favorable energy level structure, including a closed optical loop for efficient laser cooling [23]. |

| Optical Tweezers | Arrays of focused laser beams that trap and hold individual atoms in a customizable 2D geometry. They can also be used to shuttle atoms to reconfigure the processor connectivity during a computation [23] [26]. |

| Rydberg-State Lasers | Lasers tuned to specific frequencies that excite atoms from their ground state to a high-energy Rydberg state. This excitation is the basis for the Rydberg blockade effect, which enables fast, high-fidelity entangling gates [25] [26]. |

| Machine Learning Decoder | A classical software algorithm (run on GPUs) that analyzes the history of syndrome measurements to identify and locate errors with high accuracy, even in the presence of atom loss [26]. |

| Surface Code | A specific quantum error-correcting code that arranges physical qubits in a 2D grid. It is highly compatible with the 2D geometry of neutral-atom arrays and is a leading candidate for fault-tolerant quantum computation [17] [26]. |

| Haloperidol-d4-1 | Haloperidol-d4-1, CAS:136765-35-0, MF:C21H23ClFNO2, MW:379.9 g/mol |

| GW604714X | GW604714X, MF:C21H18FN5O5S, MW:471.5 g/mol |

Diagram 2: Neutral-Atom Error-Correction Experimental Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in a repeatable quantum error correction experiment, from atom preparation to logical operation.

Implications for Quantum Chemistry and Drug Development

The confluence of neutral-atom hardware capabilities and advanced fault-tolerant frameworks like AFT creates a compelling value proposition for computational chemistry and pharmaceutical research.

- Accelerated Molecular Simulation: The drastic reduction in runtime overhead promised by AFT makes it feasible to contemplate the fault-tolerant execution of complex quantum chemistry algorithms, such as Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE), for pharmaceutically relevant molecules. This could enable highly accurate predictions of molecular electronic properties, reaction pathways, and drug-binding affinities that are beyond the reach of classical computers [17].

- Practical Roadmap to Quantum Advantage: The experimental demonstrations of repeatable error correction and logical operations provide a tangible and credible pathway toward scalable, fault-tolerant quantum computing. For R&D leaders in drug development, this signals a shortened horizon for practical quantum advantage in molecular simulation, necessitating accelerated planning, algorithm development, and hardware benchmarking timelines [17] [26].

- Enhanced Algorithmic Efficiency: The dynamic reconfigurability of neutral-atom arrays allows the quantum processor's connectivity to be tailored to the specific topology of the molecular Hamiltonian being simulated. This reduces the circuit depth and number of gates required, directly mitigating error accumulation and improving the overall fidelity of the simulation [17] [23].

Neutral-atom quantum computing represents a harmonious synergy of intrinsic hardware virtues and innovative error correction architectures. Its foundational strengths—inherent qubit uniformity, long-lived coherence, and programmable connectivity—are not merely convenient features but are fundamental to implementing the low-overhead, Algorithmic Fault Tolerance necessary for practical quantum computation. For the research scientist focused on quantum chemistry, this platform offers a uniquely structured and rapidly maturing path toward simulating nature's most complex molecular systems with revolutionary accuracy. The hardware connection is clear: the neutral-atom platform is intrinsically suited to shoulder the computational burdens of next-generation drug discovery and materials design.

Implementing Fault-Tolerant Algorithms for Real-World Chemistry Problems

The pursuit of fault-tolerant quantum computation has entered a transformative phase with the development of algorithmic frameworks that leverage transversal gate operations to achieve unprecedented reductions in spacetime overhead. This whitepaper examines the foundational principles of these frameworks, detailing how the synergistic combination of transversal operations, constant-time syndrome extraction, and correlated decoding enables exponential error suppression while dramatically accelerating quantum algorithms. Through a focused analysis of recent experimental breakthroughs in quantum chemistry simulations, we demonstrate how these low-overhead circuits are paving the path toward practical quantum advantage in molecular discovery and drug development applications.

The emergence of transversal algorithmic fault tolerance (AFT) represents a paradigm shift in quantum error correction methodologies. Traditional quantum error correction imposes significant temporal overhead by requiring $d$ rounds of syndrome extraction for each logical operation, where $d$ is the code distance. This multi-round verification process ensures reliability but dramatically slows computational speed, with high-reliability algorithms potentially facing 25-30x slowdowns [16].

The AFT framework fundamentally reimagines this approach by demonstrating that a wide range of quantum error-correcting codes—including the surface code—can perform fault-tolerant logical operations with only a constant number of syndrome extraction rounds instead of the typical $d$ rounds. This innovation reduces the spacetime cost per logical gate by approximately an order of magnitude, potentially accelerating complex quantum algorithms by 10-100x while maintaining exponential error suppression [16].

For quantum chemistry applications, where simulations of molecular systems require deep quantum circuits, this overhead reduction is particularly significant. It directly addresses one of the most substantial barriers to practical quantum advantage in drug discovery and materials science.

Core Framework Components

Transversal Operations Architecture

Transversal operations form the foundational layer of low-overhead fault tolerance. An operation is classified as transversal when it applies identical local gates across all physical qubits of an encoded block simultaneously. This architectural approach ensures inherent fault tolerance because a single physical qubit error remains localized and cannot propagate throughout the code block [16].

The mathematical formulation of transversal gates ensures that a single physical fault during operation results in at most one fault in each code block, which remains within the error-correcting capability of the code. For CSS codes like the surface code, all logical Clifford operations can be implemented transversally by construction. A key example is the transversal CNOT performed between two code blocks by pairing up qubits and applying CNOTs in parallel [16].

Constant-Time Syndrome Extraction

Where traditional QEC requires repetitive syndrome measurement cycles, the AFT framework limits syndrome extraction to a constant number of rounds per operation—often just one round immediately following each transversal gate. This approach dramatically increases the logical clock speed by eliminating the waiting period for multiple verification cycles [16].

In practice, each syndrome extraction round involves ancilla qubits coupling to the data block to measure stabilizers (parity checks) for error detection. While a single round means the instantaneous state might not be a perfectly corrected codeword, the algorithm proceeds without pausing for additional checks. Subsequent transversal operations continue, with further syndrome data collected in later rounds as the circuit executes [16].

Correlated Decoding Methodology

The correlated decoding mechanism enables the AFT framework to maintain reliability despite reduced syndrome extraction. Rather than decoding after each operation in isolation, AFT employs a joint classical decoder that processes all syndrome data from all rounds throughout the circuit when a logical measurement occurs [16].

This global decoder identifies error patterns that single-round decoding would miss by analyzing correlations across time. An error not fully corrected after one round leaves distinctive patterns in subsequent syndrome measurements, which the correlated decoder can reconstruct. The result is that final logical measurement outcomes achieve reliability comparable to traditional multi-round approaches, with logical error rates still decaying exponentially with the code distance $d$ [16].

Experimental Implementations in Quantum Chemistry

Quantum Phase Estimation with Error Detection

Researchers at Quantinuum have demonstrated the first complete quantum chemistry computation using quantum error correction, calculating the ground-state energy of molecular hydrogen ($H_2$) via quantum phase estimation (QPE) on error-corrected qubits. Their implementation on the H-Series trapped-ion quantum computer utilized a seven-qubit color code to protect logical qubits with mid-circuit error correction routines [3].

The experiment employed both fault-tolerant and partially fault-tolerant compilation techniques, with circuits involving up to 22 qubits, more than 2,000 two-qubit gates, and hundreds of intermediate measurements. Despite this complexity, the error-corrected implementation produced energy estimates within 0.018 hartree of the exact value, outperforming non-error-corrected versions despite increased circuit complexity [3].

Low-Overhead Magic State Preparation

Recent advances in magic state distillation have produced significant overhead reductions through optimized circuit synthesis. By leveraging enhanced connectivity and transversal CNOT capabilities available in platforms like trapped ions and neutral atoms, researchers have constructed fault-tolerant circuits for $|CCZ\rangle$, $|CS\rangle$, and $|T\rangle$ states with minimal T-depth and reduced CNOT counts [27].

The key innovation involves an algorithm that recompiles and simplifies circuits of consecutive multi-qubit phase rotations, effectively parallelizing non-Clifford operations. This approach has demonstrated particular utility in quantum chemistry applications, where these magic states enable complex molecular simulations while maintaining error suppression capabilities [27].

Table 1: Experimental Results in Quantum Chemistry Simulations

| Experiment | System | Algorithm | Qubits | Error Suppression | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantinuum Hâ‚‚ Simulation [4] | H-Series Trapped Ion | Quantum Phase Estimation | 22 (logical) | Error detection code | 0.018 hartree from exact |

| Fault-tolerant CCZ Preparation [27] | Theory/Simulation | Phase rotation parallelization | N/A | $p$ to $p^2$ reduction | N/A |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Quantum Phase Estimation with Mid-Circuit Correction

The QPE protocol for molecular energy calculation follows a structured approach: