Mathematical Frameworks for Quantum Noise Analysis in Chemistry Circuits: From Theory to Drug Discovery Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of advanced mathematical frameworks designed to characterize, mitigate, and optimize against noise in quantum chemistry circuits.

Mathematical Frameworks for Quantum Noise Analysis in Chemistry Circuits: From Theory to Drug Discovery Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of advanced mathematical frameworks designed to characterize, mitigate, and optimize against noise in quantum chemistry circuits. Targeting researchers and professionals in quantum chemistry and drug development, we explore foundational theories like root space decomposition for noise characterization and cost-effective readout error mitigation. The scope extends to methodological advances including multireference error mitigation and hybrid classical-quantum optimization, alongside troubleshooting techniques for circuit depth reduction and noise-aware compilation. Finally, we present a rigorous validation of these frameworks through comparative analysis of their performance on real hardware and in simulated environments, concluding with an assessment of their implications for achieving reliable quantum chemistry simulations in biomedical research.

Understanding the Quantum Noise Landscape: Foundational Models and Characterization

Quantum chemistry stands as one of the most promising applications for quantum computing, with the potential to accurately simulate molecular systems that are computationally intractable for classical computers. These simulations could revolutionize drug discovery, materials design, and catalyst development. However, the path to realizing this potential is currently blocked by the formidable challenge of quantum noise in Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. Today's quantum processors typically feature 50-1000 qubits that are highly susceptible to environmental interference, leading to computational errors that fundamentally limit the accuracy and scalability of quantum chemistry calculations [1] [2].

The term "NISQ," coined by John Preskill, describes the current technological landscape where quantum computers possess limited qubit counts and lack comprehensive error correction capabilities [1]. In this context, even sophisticated quantum algorithms designed for chemical simulations produce unreliable results due to the accumulation of errors throughout computation. This whitepaper examines how noise manifests in NISQ devices, quantitatively impacts quantum chemistry calculations, and surveys the emerging mathematical frameworks and experimental protocols designed to characterize and mitigate these limitations, thereby paving the way for useful computational chemistry on near-term quantum hardware.

The Nature and Impact of Quantum Noise

Quantum noise in NISQ devices arises from multiple physical sources, each contributing to the degradation of computational accuracy:

- Decoherence: Qubits gradually lose their quantum state through interaction with the environment, causing the collapse of superposition and entanglement. This temporal limitation restricts the depth of quantum circuits that can be reliably executed [2].

- Gate Errors: Imperfect control in applying quantum gates introduces operational inaccuracies. These errors accumulate as circuit depth increases, leading to significant deviations from intended computational pathways [2].

- Measurement Errors: The process of reading qubit states introduces classical noise, where a qubit prepared in |0⟩ might be misread as |1⟩, or vice versa, corrupting the final computational result [2].

- Spatiotemporal Noise Correlations: Unlike simplified models that treat noise as isolated events, significant noise sources in quantum processors spread across both space and time, creating complex error patterns that are particularly challenging to mitigate [3] [4].

Mathematical Frameworks for Noise Characterization

Advanced mathematical frameworks are essential for accurately characterizing quantum noise. Researchers at Johns Hopkins University have developed a novel approach using root space decomposition to simplify the representation and analysis of noise in quantum systems [3] [4]. This method exploits mathematical symmetry to organize a quantum system into discrete states, analogous to rungs on a ladder, enabling clear classification of noise types based on whether they cause transitions between these states [4].

This framework provides a more realistic model of how noise propagates through quantum systems, moving beyond oversimplified models to capture the spatially and temporally correlated nature of real quantum noise. By categorizing noise into distinct types based on its effects on system states, researchers can develop targeted mitigation strategies appropriate for each classification [3].

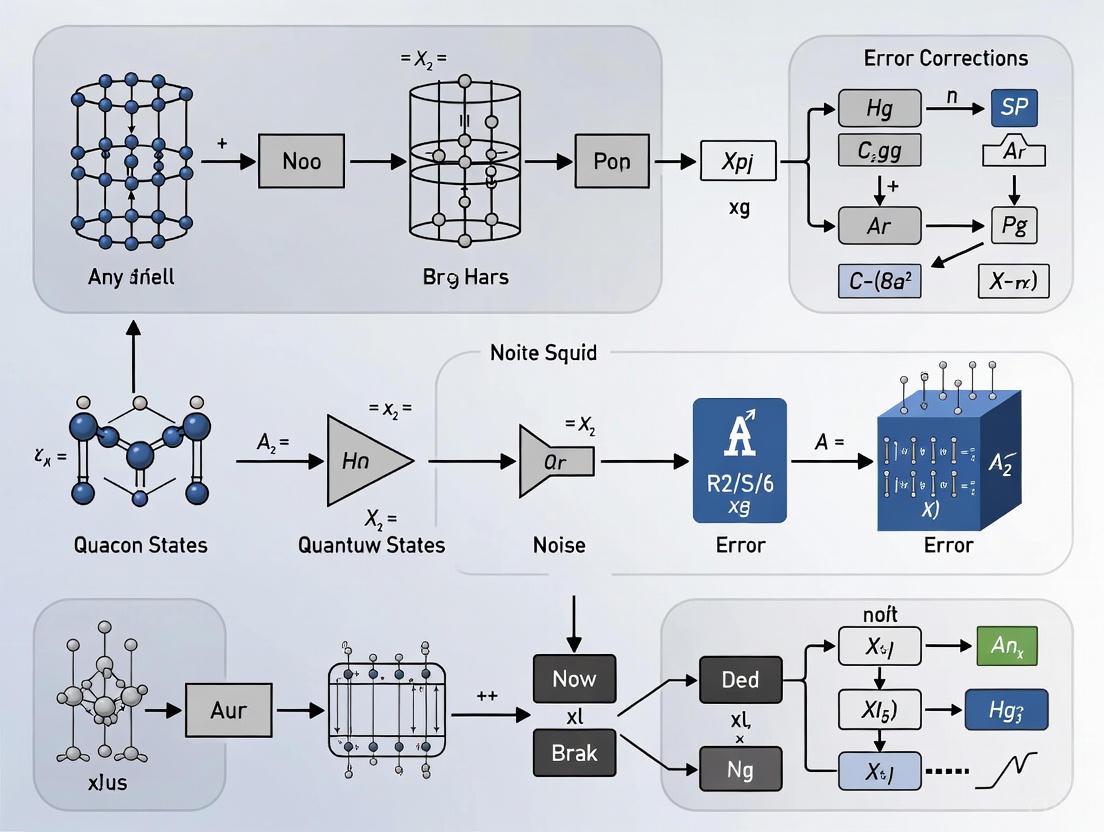

Figure 1: Quantum Noise Propagation Pathway: This diagram illustrates how fundamental noise sources in NISQ devices are characterized through mathematical frameworks and ultimately impact quantum chemistry calculations.

Quantitative Impact of Noise on Quantum Chemistry Calculations

Performance Degradation in Quantum Algorithms

The impact of noise on quantum chemistry calculations can be quantified through specific performance metrics across different algorithms and molecular systems. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent experimental studies:

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Noise on Quantum Chemistry Calculations

| Algorithm | Molecular System | Noise Impact | Mitigation Strategy | Experimental Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) [5] | Hâ‚‚O, CHâ‚„, Hâ‚‚ chains | Requires 100s-1000s of measurement bases even for <20 qubits | Sampled Quantum Diagonalization (SQD) | SQDOpt matched/exceeded noiseless VQE quality on ibm-cleveland hardware |

| Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) [6] | Materials systems (33-qubit demonstration) | Traditional QPE requires 7,242 CZ gates | Tensor-based Quantum Phase Difference Estimation (QPDE) | 90% reduction in gate overhead (794 CZ gates); 5x wider circuits |

| Quantum Subspace Methods [7] | Battery electrolyte reactions | Noise limits circuit depth and measurement accuracy | Adaptive subspace selection | Exponential measurement reduction proven for transition-state mapping |

| Grover's Algorithm [8] | Generic search problems | Pure dephasing reduces success probability significantly | None (characterization only) | Target state identification probability drops sharply with decreased dephasing time |

Resource Overhead and Scaling Limitations

The resource requirements for quantum chemistry calculations scale dramatically with molecular size and complexity, exacerbating the impact of noise:

- Measurement Overhead: Even small molecules requiring fewer than 20 qubits involve hundreds to thousands of Hamiltonian terms that must be measured across non-commuting bases, creating substantial measurement overhead that amplifies the effects of noise [5].

- Gate Complexity: Traditional quantum chemistry algorithms like Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) require significant gate counts that exceed the coherence limits of current NISQ devices. For example, a single iteration of QPE for non-trivial molecular systems can require thousands of gate operations [6].

- Qubit Connectivity Constraints: The limited connectivity between physical qubits in current hardware necessitates additional swap operations, further increasing circuit depth and susceptibility to noise [8].

Mathematical Frameworks for Noise-Resilient Quantum Chemistry

Advanced Methodologies for Noise Characterization and Mitigation

Several sophisticated mathematical approaches have been developed to address the noise limitations in quantum chemistry calculations:

Root Space Decomposition Framework: This approach, developed by researchers at Johns Hopkins University, uses mathematical symmetry and root space decomposition to simplify the representation of quantum systems. By organizing a quantum system into discrete states (like rungs on a ladder), this framework enables clear classification of noise types based on whether they cause state transitions, informing appropriate mitigation strategies for each category [3] [4].

Sampled Quantum Diagonalization (SQD): The SQD method addresses measurement overhead by using batches of measured configurations to project and diagonalize the Hamiltonian across multiple subspaces. The optimized variant (SQDOpt) combines classical Davidson method techniques with multi-basis measurements to optimize quantum ansatz states with a fixed number of measurements per optimization step [5].

Quantum Subspace Methods: These approaches leverage the inherent symmetries in molecular systems to constrain calculations to physically relevant subspaces. By measuring additional observables that indicate how much of the quantum state remains in the correct subspace, these methods can re-weight or project results to suppress contributions from noise-induced illegal states [1] [7].

Tensor-Based Quantum Phase Difference Estimation (QPDE): This innovative approach reduces gate complexity by implementing tensor network-based unitary compression, significantly improving noise resilience and scalability for large systems on NISQ hardware [6].

Experimental Protocols for Noise-Resilient Quantum Chemistry

Implementing effective noise characterization requires systematic experimental protocols:

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Noise-Resilient Quantum Chemistry

| Protocol | Methodology | Key Measurements | Hardware Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root Space Decomposition [3] [4] | Apply mathematical symmetry to represent system as discrete states; classify noise by state transition behavior | Noise categorization (state-transition vs. non-transition); mitigation strategy effectiveness | General quantum processors; no additional hardware |

| SQDOpt Implementation [5] | Combine classical Davidson method with multi-basis quantum measurements; fixed measurements per optimization step | Energy estimation accuracy vs. measurement count; comparison to noiseless VQE | NISQ devices with 10+ qubits; multi-basis measurement capability |

| Symmetry Verification [1] | Measure symmetry operators (particle number, spin); post-select or re-weight results preserving symmetries | Symmetry violation rates; energy improvement after correction | Capability to measure non-energy observables |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation [1] [2] | Run circuits at multiple amplified noise levels; extrapolate to zero-noise | Observable values at different noise strengths; extrapolation error | Controllable noise amplification (pulse stretching, gate insertion) |

| QPDE with Tensor Compression [6] | Implement tensor network-based unitary compression; reduce gate count while preserving accuracy | Gate count reduction; circuit width and depth achievable | 20+ qubit devices with moderate connectivity |

Implementing effective noise characterization and mitigation requires specialized tools and frameworks. The following table details essential resources for researchers working on quantum chemistry applications:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Noise-Resilient Quantum Chemistry

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qiskit [2] | Software Framework | Quantum circuit composition, simulation, and execution; includes noise models and error mitigation | Open-source Python library |

| PennyLane [2] | Software Library | Quantum machine learning, automatic differentiation for circuit optimization | Open-source Python library |

| Fire Opal [6] | Performance Management | Automated quantum circuit optimization, error suppression, and hardware calibration | Commercial platform (Q-CTRL) |

| Mitiq [1] | Error Mitigation Toolkit | Implementation of ZNE, PEC, and other error mitigation techniques | Open-source Python library |

| Root Space Decomposition Framework [3] | Mathematical Framework | Advanced noise characterization and classification for targeted mitigation | Research publication implementation |

| IBM Quantum Systems [5] [6] | Quantum Hardware | Cloud-accessible quantum processors for algorithm testing and validation | Cloud access (ibm-cleveland, etc.) |

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Noise-Resilient Quantum Chemistry: This diagram outlines the systematic process for designing, executing, and validating quantum chemistry calculations on NISQ devices, incorporating noise characterization and mitigation at critical stages.

The path to accurate quantum chemistry calculations on NISQ devices requires co-design of algorithms, error mitigation strategies, and hardware improvements. The mathematical frameworks and experimental protocols discussed in this whitepaper represent significant advances in addressing the core challenge of quantum noise. By leveraging root space decomposition for noise characterization, symmetry-aware algorithms to maintain valid physical states, and advanced error mitigation techniques like ZNE and PEC, researchers can extract meaningful chemical insights from today's noisy quantum processors.

As quantum hardware continues to improve with increasing qubit counts, longer coherence times, and better gate fidelities, these noise-resilient techniques will bridge the gap between current limitations and future possibilities. The integration of machine learning for automated error mitigation and the development of specialized quantum processors for chemical simulations promise to accelerate progress toward practical quantum advantage in chemistry. For researchers in drug development and materials science, understanding these noise limitations and mitigation strategies is essential for effectively leveraging quantum computing in their computational workflows.

In the pursuit of practical quantum computing, particularly for applications in quantum computational chemistry and drug development, noise remains the most significant barrier. Quantum processors are exquisitely sensitive to environmental interference—from heat fluctuations and vibrations to atomic-scale effects and electromagnetic fields—all of which disrupt fragile quantum states and compromise computational integrity [4] [9]. Traditional noise models often prove inadequate as they typically capture only isolated error events, failing to represent how noise propagates across both time and space within quantum processors [9]. This limitation severely impedes the development of effective quantum error correction codes and reliable quantum algorithms [9].

Recent research from Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) and Johns Hopkins University has introduced a transformative approach to this problem using root space decomposition, a mathematical technique that leverages symmetry principles to simplify the complex dynamics of quantum noise [4] [10]. This framework provides researchers with a more accurate and realistic method for characterizing how noise spreads through quantum systems, enabling clearer classification of noise types and more targeted mitigation strategies [4]. By representing quantum systems as structured mathematical objects, root space decomposition offers unprecedented insights into noise behavior, supporting advances in quantum error correction, hardware design, and the development of noise-aware quantum algorithms [4].

This technical guide explores the mathematical foundations of root space decomposition and its application to noise symmetry analysis in quantum systems, with particular emphasis on implications for quantum computational chemistry research.

Mathematical Foundations of Root Space Decomposition

Lie Algebras and Cartan Subalgebras

Root space decomposition originates from the theory of semisimple Lie algebras, which provides the mathematical language for describing continuous symmetries in quantum systems. In this framework, a Lie algebra is a vector space equipped with a non-associative bilinear operation called the Lie bracket, which for quantum systems corresponds to the commutator operation [A,B] = AB - BA [11].

The decomposition begins with identifying a Cartan subalgebra (ð”¥)—a maximal abelian subalgebra where all elements commute with one another. In practical terms for quantum systems, this often corresponds to the algebra generated by the diagonal components of the system Hamiltonian [11]. For the symplectic Lie algebra ð”°ð”(2n, F), which is relevant to many quantum chemistry applications, the Cartan subalgebra can be represented by the diagonal matrices within the algebra [11].

Root Spaces and the Decomposition

Once a Cartan subalgebra 𔥠is established, the root space decomposition expresses the Lie algebra 𔤠as a direct sum:

𔤠= 𔥠⊕ â¨ð”¤Î±

where the root spaces ð”¤Î± are defined for each root α in the root system Φ [11] [12]. Each root space consists of all elements x ∈ 𔤠that satisfy the eigen-relation:

[h, x] = α(h)x for all h ∈ ð”¥

The root system Φ represents the ladder operators of the Cartan subalgebra, which increment quantum numbers by α(h) for eigenvectors of 𔥠in the Hilbert space [12]. Critically, each root space ð”¤Î± is one-dimensional, providing a natural basis for analyzing operations on the quantum system [11].

Table 1: Key Mathematical Components in Root Space Decomposition

| Component | Symbol | Description | Role in Quantum Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lie Algebra | 𔤠| Vector space with Lie bracket | Generators of quantum evolution |

| Cartan Subalgebra | 𔥠| Maximal commutative subalgebra | Diagonal components of Hamiltonian |

| Root | α | Linear functional on 𔥠| Quantum number increments |

| Root Space | ð”¤Î± | {x ∈ 𔤠| [h,x]=α(h)x} |

Ladder operators between states |

| Root System | Φ | Set of all roots | Complete set of state transitions |

Application to Quantum Noise Analysis

The Symmetry Framework for Noise Characterization

The application of root space decomposition to quantum noise analysis begins with identifying symmetries in the quantum system. These symmetries are operators {Q_i} that commute with the system Hamiltonian H_0(t):

[Q_i, H_0(t)] = 0, ∀t [12]

These symmetries span an abelian subalgebra ð”® = span[{Q_i}] and generate a symmetry group that partitions the Hilbert space into invariant subspaces:

â„‹_S = â¨ð’±(q⃗) [12]

Each subspace ð’±(q⃗) corresponds to a specific set of eigenvalues q⃗ of the symmetry operators and remains invariant under noiseless evolution. When noise is introduced, we can classify it based on how it interacts with these symmetric subspaces.

Classifying Noise Through Root Spaces

In the root space framework, quantum noise is analyzed by examining how error operators act on the structured state space. The Johns Hopkins research team demonstrated that noise can be systematically categorized by its effect on the "ladder" representation of the quantum system [4] [9].

William Watkins, a co-author of the study, explained: "That allows us to classify noise into two different categories, which tells us how to mitigate it. If it causes the system to move from one rung to another, we can apply one technique; if it doesn't, we apply another" [9].

This classification emerges naturally from the root space perspective:

- Symmetry-preserving noise: Noise operators commute with all symmetry generators (

[Q, N_μ] = 0 ∀Q ∈ ð”®). These errors remain confined within the symmetric subspaces and maintain the system's conserved quantities [12]. - Symmetry-breaking noise: Noise operators do not commute with the symmetry group, causing transitions between different symmetric subspaces. The root space decomposition precisely characterizes the specific leakage pathways available to these errors [12].

Table 2: Noise Classification via Root Space Decomposition

| Noise Type | Mathematical Condition | Impact on Quantum State | Mitigation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry-Preserving | [ð”®, H_E(t)] = 0 |

Confined within symmetric subspaces | Stabilization within subspaces |

| Symmetry-Breaking | [ð”®, H_E(t)] ≠0 |

Leakage between subspaces | Targeted error correction |

| Diagonal Noise | N_μ ∈ 𔥠|

Phase errors, no state transitions | Phase correction protocols |

| Off-Diagonal Noise | N_μ ∈ ð”¤Î± for some α |

State transition errors | Dynamical decoupling |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementing Root Space Noise Analysis

The experimental protocol for applying root space decomposition to noise characterization involves a structured workflow that transforms the quantum system into its symmetry-adapted representation.

Workflow: Root Space Noise Analysis

Step 1: Identify System Symmetries

The first step involves identifying the complete set of symmetries {Q_i} of the quantum system Hamiltonian. For quantum chemistry applications, these typically include particle number conservation, spin symmetries, and point group symmetries of the molecular system [13] [12]. The symmetries must form a commuting set: [Q_i, Q_j] = 0 for all i, j.

Step 2: Construct Cartan Subalgebra

The identified symmetries are used to construct an appropriate Cartan subalgebra 𔥠that contains the symmetry algebra ð”®. For a system of n qubits with a specified set of symmetries, this involves building a maximal set of commuting operators that includes both the system symmetries and additional operators needed to complete the subalgebra [11] [12].

Step 3: Perform Root Space Decomposition

Using the Cartan subalgebra, the full Lie algebra 𔤠= ð”°ð”²(2^n) is decomposed into root spaces:

𔤠= 𔥠⊕ â¨ð”¤Î±

This decomposition is achieved by solving the eigen-relation [h, x] = α(h)x for all h ∈ 𔥠to identify basis elements for each root space ð”¤Î± [11]. The root system Φ is then characterized by the set of linear functionals α that appear in these relations.

Step 4: Classify Noise Operators

Experimental noise sources are mapped to specific operators N_μ in the Lie algebra [12]. Each noise operator is then classified based on its location in the root space decomposition:

- Operators in 𔥠represent phase errors

- Operators in specific ð”¤Î± represent state transition errors between symmetry sectors

- The specific root α indicates the type of state transition induced

Step 5: Develop Targeted Mitigation Strategies

Based on the noise classification, tailored error mitigation and correction strategies are developed. For noise confined to specific root spaces, targeted dynamical decoupling sequences can be designed. For symmetry-breaking noise, specialized quantum error correcting codes can be implemented that protect against the specific leakage channels identified [4] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Noise Symmetry Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Root Space Decomposition Framework | Mathematical structure for noise classification | Theoretical analysis of noise propagation in quantum systems |

| Classical Quantum Simulators | Pre-validation of noise models | Testing root space predictions before hardware deployment |

| Quantum Process Tomography | Experimental noise characterization | Extracting actual noise operators for classification |

| Symmetry-Adapted Quantum Circuits | Hardware implementation preserving symmetries | Experimental validation on NISQ devices |

| Filter Function Formalism (FFF) | Quantifying noise impact in symmetric systems | Analyzing non-Markovian noise in quantum dynamics [12] |

| S-2474 | S-2474|COX-2/5-LOX Inhibitor|CAS 158089-95-3 | |

| Ro 41-0960 | Ro 41-0960, CAS:125628-97-9, MF:C13H8FNO5, MW:277.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Case Study: Noise Analysis in Quantum Chemistry Circuits

ExtraFerm Simulator for Quantum Chemistry

The practical value of symmetry-based noise analysis is exemplified by its application in quantum computational chemistry. Researchers have developed specialized tools like ExtraFerm, an open-source quantum circuit simulator tailored to chemistry applications that contain passive fermionic linear optical elements and controlled-phase gates [13].

ExtraFerm leverages the inherent symmetries of quantum chemical systems, particularly particle number conservation, to enable efficient classical simulation of certain quantum circuits [13]. This capability is invaluable for verifying quantum computations and understanding how noise affects chemical calculations on quantum hardware.

Experimental Validation on Quantum Hardware

Recent experimental work has demonstrated the utility of this approach for practical quantum chemistry applications. In one study, researchers applied these techniques to a 52-qubit Nâ‚‚ system run on an IBM Heron quantum processor, observing accuracy improvements of up to 46.09% in energy estimates compared to baseline implementations [13].

The integration of symmetry-aware error mitigation with sample-based quantum diagonalization (SQD) led to significant variance reduction up to 98.34% across repeated trials, with minimal computational overhead (at worst 2.03% of runtime) [13]. These results demonstrate the practical impact of symmetry-informed noise analysis in producing more reliable quantum chemistry computations.

Application: Chemistry Circuit Analysis

Advanced Applications: Non-Markovian Noise Analysis

Recent research has extended the root space decomposition approach beyond the Markovian noise setting to address classical non-Markovian noise in symmetry-preserving quantum dynamics [12]. This advancement is particularly relevant for real-world quantum hardware where noise often exhibits temporal correlations.

In this extended framework, researchers have shown that symmetry-preserving noise maintains the symmetric subspace, while nonsymmetric noise leads to highly specific leakage errors that are block diagonal in the symmetry representation [12]. This precise characterization of noise propagation enables more effective error suppression strategies for contemporary quantum processors.

The mathematical formalism combines root space decompositions with the filter function formalism (FFF) to identify and characterize the dynamical propagation of noise through quantum systems [12]. This approach provides new analytic insights into the control and characterization of open quantum system dynamics, with broad applicability across quantum computing platforms.

Root space decomposition provides a powerful mathematical foundation for understanding and mitigating quantum noise through symmetry principles. By transforming the complex problem of noise characterization into a structured classification task, this approach enables more targeted and effective error mitigation strategies.

The integration of this mathematical framework with quantum computational chemistry has demonstrated significant practical benefits, improving the accuracy and reliability of molecular simulations on noisy quantum hardware. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, the synergy between sophisticated mathematical tools like root space decomposition and experimental quantum platforms will be essential for overcoming the noise barrier and realizing the full potential of quantum computation for chemistry and drug development.

Future research directions include extending these techniques to more complex molecular symmetries, developing automated tools for symmetry-adapted quantum circuit compilation, and creating specialized quantum error correcting codes that leverage the precise noise characterization provided by root space analysis.

The pursuit of fault-tolerant quantum computation for chemical systems faces a fundamental obstacle: noise propagation. Unlike classical bits, quantum bits (qubits) maintaining quantum states are exquisitely sensitive to environmental disturbances. This noise manifests as errors that propagate through quantum circuits, corrupting the results of calculations essential for drug discovery and materials design. Current noise models often oversimplify by treating errors as isolated events, failing to capture the complex spatial and temporal correlations that occur in real hardware. This guide establishes a comprehensive mathematical framework for characterizing how noise propagates, with particular emphasis on applications in quantum chemistry circuits for simulating molecular systems.

Theoretical Foundations of Quantum Noise

The Mathematical Structure of Noise Propagation

Noise in quantum systems can be represented through completely positive trace-preserving maps, most commonly the Kraus operator sum representation. For a quantum state Ï, the noisy evolution is given by: ε(Ï) = Σk EkÏEk†, where the Kraus operators {Ek} satisfy Σk Ek†Ek = I. The structure of these operators determines how errors propagate through sequential quantum gates. In quantum chemistry circuits, which often involve Trotterized time evolution and variational ansätze, this propagation becomes critically important. The individual error channels can compound, leading to significant miscalculations of molecular properties such as ground state energies or reaction barrier heights [7].

A Framework for Spatial-Temporal Correlation Analysis

A recent breakthrough from Johns Hopkins researchers provides a more sophisticated framework for understanding noise propagation. They applied root space decomposition, a mathematical technique from Lie algebra, to characterize how noise spreads across quantum systems both spatially (across qubits) and temporally (across circuit depth) [4]. This method represents the quantum system as a ladder, where each rung corresponds to a distinct state. Noise is then classified based on whether it causes transitions between these states or induces phase errors within them [4]. This classification is fundamental to developing targeted mitigation strategies, as different error types require different correction techniques.

Mathematical Frameworks for Noise Characterization

Root Space Decomposition for Noise Classification

The root space decomposition framework simplifies the complex problem of noise characterization by leveraging mathematical symmetry. The methodology enables researchers to:

- Decompose System Dynamics: Break down the Hilbert space of a quantum processor into orthogonal subspaces based on symmetry properties, creating a structured "ladder" of system states [4].

- Categorize Noise Types: Classify noise operators based on their effect on these subspaces. Noise that causes movement between subspaces (inter-rung transitions) can be separated from noise that affects phases within a subspace (intra-rung phase errors) [4].

- Predict Propagation Patterns: The framework provides a mathematically compact way to predict how specific noise sources will propagate through both space (across qubits) and time (through sequential operations) [4].

This approach moves beyond simplistic isolated error models to capture the correlated nature of noise in real quantum hardware, which is essential for developing effective error mitigation strategies for quantum chemistry calculations.

Quantum Subspace Methods for Noisy Calculations

Quantum subspace diagonalization methods provide another mathematical framework particularly suited to noisy quantum chemistry calculations. These methods project the molecular Hamiltonian into a smaller subspace constructed from quantum measurements, then diagonalize it classically. Theoretical analysis has established rigorous complexity bounds for these approaches under realistic noise conditions [7]. For chemical reaction modeling, adaptive subspace selection has been proven to achieve exponential reduction in required measurements compared to uniform sampling, despite noisy hardware conditions [7]. The table below summarizes key mathematical frameworks for noise characterization:

Table 1: Mathematical Frameworks for Quantum Noise Characterization

| Framework | Core Approach | Noise Propagation Insights | Application to Quantum Chemistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root Space Decomposition [4] | Leverages symmetry properties to decompose system state space | Classifies noise by transition type between state subspaces; reveals spatial-temporal correlations | Enables hardware-specific noise models for molecular energy calculations |

| Quantum Subspace Methods [7] | Projects Hamiltonian into smaller, noise-resilient subspace | Characterizes measurement overhead under realistic noise conditions | Provides exponential improvement for chemical reaction pathway modeling |

| Spatial-Temporal Correlation Models | Extends Markovian noise to include qubit connectivity and timing | Maps how errors correlate across processor geometry and circuit execution time | Critical for error correction in deep quantum chemistry circuits |

Experimental Protocols for Noise Characterization

Protocol for Spatial-Temporal Correlation Mapping

Objective: Characterize correlated noise across qubit arrays and through circuit runtime.

Materials Required:

- Quantum processor with calibration data

- Randomized benchmarking sequences

- Tomography protocols for process reconstruction

- Custom control pulses for targeted gate operations

Methodology:

- Initial System Characterization:

- Perform standard gate set tomography on individual qubits

- Measure baseline T1 and T2 coherence times across the processor

- Map qubit connectivity and crosstalk coefficients

Spatial Correlation Analysis:

- Execute simultaneous randomized benchmarking on qubit pairs

- Correlate error events across physical and logical qubit layouts

- Measure error propagation through CNOT and other two-qubit gates

Temporal Correlation Analysis:

- Implement interleaved benchmarking sequences with varying delays

- Characterize error accumulation through deep quantum circuits

- Model noise memory effects using non-Markovian techniques

Data Integration:

- Apply root space decomposition to classify observed noise patterns [4]

- Build correlated noise models incorporating both spatial and temporal components

- Validate models against experimental results for quantum chemistry benchmark circuits

Protocol for Coherent Error Quantification

Objective: Measure and characterize coherent errors from miscalibrated gates and systematic control failures.

Materials Required:

- Quantum processor with programmable control parameters

- Process tomography toolkit

- Gate set tomography software

- Hamiltonian learning algorithms

Methodology:

- Gate Set Tomography:

- Reconstruct complete process matrices for native gate set

- Identify non-unitary components indicating decoherence

- Isolate coherent errors from stochastic noise sources

Hamiltonian Parameter Estimation:

- Implement quantum process tomography on target gates

- Extract actual Hamiltonian parameters from reconstructed processes

- Compare with ideal gate Hamiltonians to quantify miscalibrations

Propagation Testing:

- Implement target quantum chemistry circuits (e.g., for molecular energy calculation)

- Measure deviation from simulated noiseless results

- Correlate specific coherent errors with chemical property miscalculations

Visualization of Noise Propagation Frameworks

Quantum Noise Characterization Workflow

Figure 1: Workflow for comprehensive quantum noise characterization using symmetry principles and root space decomposition.

Noise Propagation Pathways in Quantum Circuits

Figure 2: Noise propagation pathways from physical sources to impact on quantum chemistry calculations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Quantum Noise Characterization

| Tool/Category | Function in Noise Characterization | Specific Examples/Formats |

|---|---|---|

| Noise Modeling Frameworks | Provides mathematical structure for analyzing error propagation | Root space decomposition [4], Quantum subspace methods [7], Spatial-temporal correlation models |

| Characterization Protocols | Experimental methods for measuring noise parameters | Randomized benchmarking, Gate set tomography, Process tomography, Hamiltonian learning |

| Quantum Hardware Access | Platform for experimental validation of noise models | Superconducting qubits, Trapped ions, Photonic processors with calibration data |

| Simulation Software | Classical simulation of noisy quantum systems | Quantum circuit simulators with noise models, Digital twins of quantum processors |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Algorithms to reduce noise impact on calculations | Zero-noise extrapolation, Probabilistic error cancellation, Dynamical decoupling sequences |

| Saroaspidin B | Saroaspidin B, CAS:112663-68-0, MF:C25H32O8, MW:460.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Saroaspidin C | Saroaspidin C, CAS:112663-70-4, MF:C26H34O8, MW:474.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Applications in Quantum Chemistry and Drug Development

The characterization of noise propagation has profound implications for quantum chemistry applications in pharmaceutical research. Reliable calculation of molecular properties depends on minimizing error accumulation throughout quantum circuits. The spatial-temporal correlation models enable researchers to:

- Predict Molecular Energy Errors: By understanding how noise propagates through variational quantum eigensolver circuits, researchers can estimate errors in calculated ground state energies of drug molecules [7].

- Optimize Circuit Depth: Knowing the correlation patterns of noise allows for strategic circuit compilation that minimizes error accumulation while maintaining chemical accuracy [4].

- Design Noise-Resilient Algorithms: Quantum subspace methods leverage noise characterization to construct algorithms that inherently mitigate error propagation in molecular calculations [7].

For drug development professionals, these advances translate to more reliable predictions of drug-target interactions, reaction pathways for synthesis, and physicochemical properties of candidate molecules. The rigorous mathematical frameworks for noise analysis provide confidence in quantum computations despite hardware imperfections.

Characterizing noise propagation from coherent errors to spatial-temporal correlations represents a critical advancement in quantum computation for chemistry and drug discovery. The mathematical frameworks of root space decomposition and quantum subspace methods provide structured approaches to understanding and mitigating noise in quantum circuits. As these techniques mature, they will enable increasingly accurate quantum chemical calculations on imperfect hardware, accelerating the application of quantum computing to pharmaceutical challenges. The experimental protocols and visualization frameworks presented here offer researchers practical tools for implementing these approaches in their quantum chemistry investigations.

The accurate simulation of molecular systems is a cornerstone of advancements in drug discovery and materials science. At the heart of this challenge lies the critical task of benchmarking—establishing reliable baselines for molecular systems that exhibit both weakly and strongly correlated electron behavior. The reliability of these benchmarks is paramount, as they form the foundation upon which faster, more approximate methods are built and validated. Recent investigations have revealed alarming discrepancies between two of the most trusted theoretical methods—diffusion quantum Monte Carlo (DMC) and coupled-cluster theory (CCSD(T))—when applied to noncovalent interaction energies in large molecules [14]. These discrepancies are significant enough to cause qualitative differences in calculated material properties, with serious implications for scientific and technological applications. Furthermore, the emergence of quantum computational chemistry has introduced new variables, particularly quantum noise, that complicate the benchmarking landscape. This technical guide examines current benchmarking methodologies, identifies sources of error and discrepancy, and provides protocols for establishing robust baselines within the context of mathematical frameworks for analyzing noise in quantum chemistry circuits.

The Benchmarking Challenge: Methodological Discrepancies

The CCSD(T) versus DMC Discrepancy

For years, coupled-cluster theory including single, double, and perturbative triple excitations (CCSD(T)) has been regarded as the "gold standard" of quantum chemistry for weakly correlated systems. Similarly, diffusion quantum Monte Carlo (DMC) has been trusted for providing accurate benchmark results. However, recent studies on large molecular systems containing over 100 atoms have revealed troubling discrepancies between these methods [14].

A key investigation focused on the parallel displaced coronene dimer (Câ‚‚Câ‚‚PD), where significant discrepancies emerged between DMC and CCSD(T) predictions. The table below summarizes the interaction energies obtained through different theoretical approaches:

Table 1: Interaction Energies for Parallel Displaced Coronene Dimer (kcal/mol)

| Theory Method | Interaction Energy | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| MP2 | -38.5 ± 0.5 | [14] |

| CCSD | -13.4 ± 0.5 | [14] |

| CCSD(T) | -21.1 ± 0.5 | [14] |

| CCSD(cT) | -19.3 ± 0.5 | [14] |

| DMC | -18.1 ± 0.8 | [14] |

| DMC | -17.5 ± 1.4 | [14] |

| LNO-CCSD(T) | -20.6 ± 0.6 | [14] |

The discrepancy between CCSD(T) (-21.1 kcal/mol) and DMC (approximately -17.8 kcal/mol average) represents a significant difference that can materially impact predictions of molecular properties and interactions. This systematic overestimation of interaction energies in CCSD(T) has been attributed to the "(T)" approximation itself, which tends to overcorrelate systems with large polarizabilities [14].

The Infrared Catastrophe and Overcorrelation

The fundamental issue with CCSD(T) for large, polarizable systems relates to what is known as the "infrared catastrophe" – a divergence of correlation energy in the thermodynamic limit for metallic systems [14]. Second-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) exhibits a similar but more pronounced overestimation of interaction energies (-38.5 kcal/mol for the coronene dimer), while methods like CCSD and the random-phase approximation that resum certain terms to infinite order demonstrate better performance.

A modified approach, CCSD(cT), which includes selected higher-order terms in the triples amplitude approximation without significantly increasing computational complexity, shows promise in addressing this overcorrelation. For the coronene dimer, CCSD(cT) yields an interaction energy of -19.3 kcal/mol, much closer to the DMC results [14].

Benchmarking Protocols for Different Correlation Regimes

Weakly Correlated Systems

For weakly correlated systems, such as the hydrogen chain at compressed bond distances or hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), coupled-cluster methods generally provide reliable benchmarks when properly converged [15]. The key considerations include:

- Basis Set Completeness: Achieving the complete basis set limit through systematic basis set expansion or extrapolation.

- Method Hierarchy: Employing a well-defined hierarchy of methods (HF → MP2 → CCSD → CCSD(T)) to monitor convergence.

- Size Consistency: Ensuring methods are size-consistent for correct description of dissociated fragments.

In studies of 2D h-BN, the equation of state calculated using orbital-partitioned density matrix embedding theory (DMET) with quantum solvers accurately captures the curvature of the equation of state, though it may underestimate absolute correlation energy compared to k-point coupled-cluster (k-CCSD) [15].

Strongly Correlated Systems

Strongly correlated systems, such as stretched bonds in molecules or transition metal oxides like nickel oxide (NiO), present greater challenges. For these systems:

- Multireference Character: Methods must account for significant contributions from multiple electronic configurations.

- Active Space Selection: Appropriate active space selection is critical for high-level methods like CASSCF or CASCI.

- Embedding Techniques: Quantum embedding theories like density matrix embedding theory (DMET) partition the system into fragments, allowing high-level treatment of strongly correlated subsets [15].

For the strongly correlated solid NiO, quantum embedding combined with orbital-based partitioning can reduce the quantum resource requirement from 9984 qubits to just 20 qubits, making accurate simulation feasible on near-term quantum devices [15].

Table 2: Benchmarking Methods for Different Correlation Regimes

| System Type | Recommended Methods | Limitations | Validation Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weakly Correlated | CCSD(T), CCSD(cT), MP2 | Overcorrelation for large polarizable systems | Comparison with DMC, basis set convergence |

| Strongly Correlated | DMC, DMET, MRCI, CASSCF | High computational cost, active space selection | Comparison with experimental properties |

| Large Molecules | Local CC approximations (DLPNO, LNO) | Approximation errors from localization | Comparison with canonical calculations |

| Periodic Solids | Quantum Embedding, k-CCSD | Scaling to thermodynamic limit | Convergence with k-point mesh |

The Quantum Computing Context: Noise and Error Mitigation

Noise Characterization in Quantum Circuits

Understanding and characterizing quantum noise is essential for leveraging quantum computers in benchmarking molecular systems. Researchers at Johns Hopkins University have developed a novel framework using root space decomposition to analyze how noise spreads through quantum systems [4]. This approach classifies noise based on whether it causes the system to transition between different states, providing guidance for appropriate mitigation techniques.

The mathematical framework represents the quantum system as a ladder, where each rung corresponds to a distinct state. This representation enables clearer classification of noise types and informs the selection of mitigation strategies specific to each noise category [4].

Quantum Error Mitigation Strategies

As quantum hardware advances, error mitigation strategies become crucial for obtaining accurate results on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. Two prominent approaches include:

Reference-State Error Mitigation (REM) employs a classically tractable reference state (typically Hartree-Fock) to quantify and correct noise effects on quantum hardware [16]. While effective for weakly correlated systems where the Hartree-Fock state has substantial overlap with the true ground state, REM performance degrades for strongly correlated systems with multireference character.

Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM) extends REM by utilizing multiple reference states to capture noise effects in strongly correlated systems [16]. This approach uses Givens rotations to efficiently construct quantum circuits that generate multireference states with preserved symmetries (particle number, spin projection). For systems like stretched Nâ‚‚ and Fâ‚‚ molecules, MREM demonstrates significant improvement over single-reference REM [16].

Quantum Circuit Optimization

Frameworks like QuCLEAR (Quantum Clifford Extraction and Absorption) optimize quantum circuits by identifying and classically simulating Clifford subcircuits, significantly reducing quantum gate counts [17]. This optimization reduces circuit execution time and decreases susceptibility to noise, particularly beneficial for the deep circuits required in quantum chemistry applications.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

High-Accuracy Wavefunction Protocols

For establishing reliable benchmarks, several protocols have been developed:

The Woon-Peterson-Dunning Protocol employs coupled-cluster theory with augmented correlation-consistent basis sets, progressively increasing basis set size to approach the complete basis set limit [18]. This protocol uses the supermolecule approach with counterpoise correction to address basis set superposition error, as demonstrated in studies of weakly bound complexes like Ar-Hâ‚‚ and Ar-HCl [18].

Quantum Embedding Protocols using density matrix embedding theory (DMET) partition systems into fragments, solving strongly correlated fragments with high-level methods while treating the environment at a lower level of theory [15]. The orbital-based multifragment approach further divides systems into strongly and weakly correlated orbital subsets, enabling efficient treatment with hybrid quantum-classical solvers.

Quantum Computational Chemistry Protocols

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) Integration combines classical optimization with quantum state preparation to find ground states of molecular systems [16]. The accuracy depends on the ansatz choice and error mitigation strategies.

Sample-Based Quantum Diagonalization (SQD) enhances variational algorithms by sampling configurations from quantum computers to select subspaces for Hamiltonian diagonalization [13]. Integration with specialized simulators like ExtraFerm improves accuracy by selecting high-probability bitstrings, achieving up to 46% accuracy improvement for a 52-qubit Nâ‚‚ system [13].

Visualization of Benchmarking Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the integrated benchmarking workflow for molecular systems across classical and quantum computational approaches:

Molecular System Benchmarking Workflow

The error mitigation process in quantum computation, particularly for strongly correlated systems, can be visualized as follows:

Quantum Error Mitigation Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Computational Tools for Molecular Benchmarking

| Tool/Method | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T) | Coupled-cluster with perturbative triples | Weakly correlated systems, "gold standard" |

| CCSD(cT) | Modified coupled-cluster with resummed triples | Large, polarizable systems avoiding overcorrelation |

| DMC | Diffusion quantum Monte Carlo | Strongly correlated systems, benchmark validation |

| DMET | Density matrix embedding theory | Fragment-based treatment of large systems |

| PNO-LCCSD(T)-F12 | Local coupled-cluster with explicit correlation | Large molecular systems with controlled approximation |

| ExtraFerm | Fermionic linear optical circuit simulator | Quantum circuit simulation for chemistry |

| QuCLEAR | Quantum circuit optimization framework | Gate count reduction for noise resilience |

| Givens Rotations | Multireference state preparation | Quantum error mitigation for strong correlation |

| SB 216763 | SB 216763, CAS:280744-09-4, MF:C19H12Cl2N2O2, MW:371.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SB-218078 | SB-218078, CAS:135897-06-2, MF:C24H15N3O3, MW:393.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Establishing reliable benchmarks for molecular systems across the correlation spectrum remains a challenging but essential endeavor in computational chemistry and materials science. The recently identified discrepancies between highly trusted methods like CCSD(T) and DMC highlight the need for continued method development and careful validation. The emergence of quantum computing introduces both new opportunities and new challenges, particularly regarding the impact of noise on computational results.

Moving forward, a multifaceted approach combining classical high-accuracy methods with quantum computational strategies, augmented by sophisticated error mitigation techniques, offers the most promising path toward robust benchmarking. Methods like CCSD(cT) that address known limitations of established approaches, combined with quantum embedding strategies and multireference error mitigation, provide the toolkit needed to establish the next generation of molecular benchmarks. These advances will ultimately enhance the reliability of computational predictions in critical areas like drug design and functional materials development.

Error Mitigation and Noise-Aware Algorithmic Design for Chemistry Workloads

In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, quantum devices are characterized by limited qubit counts and significant error rates that impede reliable computation. Among the various noise sources, readout error (or measurement error) represents a critical bottleneck, particularly for algorithms requiring precise expectation value estimation, such as those used in quantum chemistry and drug discovery research. Readout error occurs when the process of measuring a qubit's final state incorrectly identifies its value (e.g., recording a |0⟩ state as |1⟩, or vice versa) due to imperfections in the measurement apparatus and environmental interactions [19]. The impact of these errors is not merely additive; they propagate through computational results, often rendering raw quantum processor outputs unusable for scientific applications without post-processing correction.

Twirled Readout Error Extinction (T-REx) has emerged as a computationally inexpensive yet powerful technique for mitigating these readout errors. As a method compatible with current NISQ hardware constraints, T-REx operates on a foundational principle: it characterizes the specific classical confusion matrix that describes the probabilistic misassignment of qubit states during measurement. By inverting the effects of this characterized noise, T-REx can recover significantly more accurate expectation values from noisy quantum computations. Recent research demonstrates that its application can enable smaller, older-generation quantum processors to achieve chemical accuracy in ground-state energy calculations that surpass the unmitigated results from much larger, more advanced devices [20] [21]. This guide provides a comprehensive technical framework for implementing and optimizing T-REx, situating it within the broader mathematical analysis of noise in quantum chemistry circuits.

Theoretical Foundation of T-REx

The Readout Error Model

The fundamental object characterizing readout error is the assignment probability matrix, ( A ), sometimes called the confusion or response matrix. For a single qubit, ( A ) is a ( 2 \times 2 ) stochastic matrix:

[ A = \begin{pmatrix} p(0|0) & p(0|1) \ p(1|0) & p(1|1) \end{pmatrix} ]

where ( p(i|j) ) denotes the probability of measuring state ( i ) when the true pre-measurement state was ( j ). In an ideal, noise-free scenario, ( A ) would be the identity matrix. In practice, calibration procedures estimate these probabilities, revealing non-zero off-diagonal elements [20].

For an ( n )-qubit system, the assignment matrix ( \mathcal{A} ) has dimensions ( 2^n \times 2^n ), describing the probability of observing each of the ( 2^n ) possible bitstrings given each possible true state. The core mitigation strategy is straightforward: given a vector of observed probability counts ( \vec{p}{\text{obs}} ), an estimate of the true probability vector ( \vec{p}{\text{true}} ) is obtained by applying the inverse of the characterized assignment matrix:

[ \vec{p}{\text{mitigated}} \approx \mathcal{A}^{-1} \vec{p}{\text{obs}} ]

However, a significant practical challenge is that the direct assignment matrix ( \mathcal{A} ) grows exponentially with qubit count, making its characterization and inversion intractable for large systems. T-REx addresses this scalability issue through a combination of twirling and efficient modeling.

The "Twirling" Operation and Error Extraction

The "Twirled" component of T-REx refers to the use of randomized gate sequences applied immediately before measurement. This process, analogous to techniques in randomized benchmarking, transforms complex, coherent noise into a stochastic, depolarizing-like noise channel that is easier to characterize and invert accurately [20]. By averaging over many random twirling sequences, T-REx effectively extracts the underlying stochastic error model, suppressing biasing effects from coherent errors during the readout process.

The practical implementation combines this twirling with a tensor product approximation of the assignment matrix. Instead of characterizing the full ( 2^n \times 2^n ) matrix, T-REx assumes that the readout errors for each qubit are independent, allowing the global assignment matrix to be approximated as the tensor product of single-qubit assignment matrices: ( \mathcal{A} \approx A1 \otimes A2 \otimes \cdots \otimes A_n ). This reduces the number of parameters required for characterization from ( O(4^n) ) to a more manageable ( O(n) ), albeit at the cost of neglecting correlated readout errors. Research indicates that this approximation often works well in practice, providing substantial error reduction despite the simplified model [20].

Implementation Methodology

Calibration Protocol for T-REx

The first step in implementing T-REx is to calibrate the single-qubit assignment matrices. The following protocol must be performed for each qubit on the target quantum processor.

Step-by-Step Calibration:

- Preparation: For each computational basis state ( |i\rangle ) (where ( i \in {0, 1} ) for a single qubit), prepare a large number of identical circuits that definitively create that state. For state ( |0\rangle ), this may be as simple as an idle circuit. For state ( |1\rangle ), apply an X gate after initializing in ( |0\rangle ).

- Twirling: Before measurement, apply a short sequence of randomly selected gates from the set ( {I, X} ). The sequence should end with a gate that returns the qubit to the original prepared state ( |i\rangle ) if the gates were ideal and noise-free. This sequence constitutes the twirl.

- Measurement: Perform a measurement on the qubit. Record the outcome (0 or 1).

- Averaging: Repeat steps 1-3 many times (e.g., 10,000 shots) for each prepared state ( |i\rangle ) and for many different random twirling sequences.

- Matrix Estimation: For each qubit, populate its ( 2 \times 2 ) assignment matrix ( A ) by calculating the empirical probabilities:

- ( p(0|0) = \frac{\text{Count}(0 \text{ measured} | |0\rangle \text{ prepared})}{\text{Total shots for } |0\rangle} )

- ( p(1|0) = \frac{\text{Count}(1 \text{ measured} | |0\rangle \text{ prepared})}{\text{Total shots for } |0\rangle} )

- Similarly for ( p(0|1) ) and ( p(1|1) ) using data from the ( |1\rangle ) preparation circuits.

This process, when performed for all qubits, yields the set of matrices ( {A1, A2, ..., A_n} ).

Mitigation Protocol for Algorithm Execution

Once the calibration data is collected and the matrices are constructed, the mitigation protocol is applied during the execution of a target algorithm (e.g., VQE for a quantum chemistry problem).

- Run Target Circuit: Execute the parameterized quantum circuit of interest on the hardware, concluding with the same randomized twirling sequence used during calibration applied before the final measurement.

- Collect Noisy Statistics: Gather the measurement results (counts for each bitstring) over many shots to build an observed probability vector ( \vec{p}_{\text{obs}} ).

- Construct Global Matrix: Form the approximate global assignment matrix ( \mathcal{A}{\text{approx}} = A1 \otimes A2 \otimes \cdots \otimes An ).

- Apply Mitigation: Compute the mitigated probability distribution by solving the linear system ( \mathcal{A}{\text{approx}} \cdot \vec{p}{\text{mitigated}} = \vec{p}{\text{obs}} ) for ( \vec{p}{\text{mitigated}} ). Due to noise and the tensor product approximation, this system may be inconsistent. Therefore, a least-squares solution is often employed: [ \vec{p}{\text{mitigated}} = \arg \min{\vec{p} \geq 0, \ \sumi pi = 1} || \mathcal{A}{\text{approx}} \cdot \vec{p} - \vec{p}{\text{obs}} ||^2 ] This constrained optimization ensures ( \vec{p}_{\text{mitigated}} ) is a valid probability distribution.

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for implementing T-REx, from calibration to mitigation of a target quantum algorithm.

Experimental Validation and Performance Data

Quantum Chemistry Application: VQE for BeHâ‚‚

The efficacy of T-REx has been rigorously tested in the context of the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) applied to the beryllium hydride (\ce{BeH2}) molecule. This application is central to quantum chemistry research, where accurately calculating ground-state energies is critical for understanding molecular behavior in pharmaceutical and materials science [20].

Experimental Setup:

- Molecular System: \ce{BeH2} at a fixed bond distance.

- Qubit Mapping: The electronic structure problem was mapped to qubits using the parity transformation with qubit tapering, reducing the resource requirements.

- Ansätze: Both hardware-efficient and physically-informed (UCC-type) ansätze were tested.

- Hardware: Experiments were conducted on the 5-qubit

IBMQ Belemprocessor and the 156-qubitIBM Fezprocessor for comparison. - Mitigation: T-REx was deployed on

IBMQ Belemand compared against unmitigated runs on both devices.

Key Results:

The results demonstrated that error mitigation can be more impactful than hardware scale alone. The older, smaller 5-qubit device (IBMQ Belem), when enhanced with T-REx, produced ground-state energy estimations an order of magnitude more accurate than those from the larger, more advanced 156-qubit device (IBM Fez) without error mitigation [20] [21]. This finding underscores that the quality of optimized variational parameters—which define the molecular ground state—is a more reliable benchmark for VQE performance than raw hardware energy estimates, and this quality is drastically improved by readout error mitigation.

Table 1: Performance Comparison for VQE on \ce{BeH2} with T-REx [20]

| Quantum Processor | Error Mitigation | Energy Accuracy (Ha) | Parameter Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-qubit IBMQ Belem | T-REx | ~0.01 | High |

| 156-qubit IBM Fez | None | ~0.1 (Order of magnitude worse) | Low |

| 5-qubit IBMQ Belem | None | >0.1 | Low |

Cross-Platform Performance and Comparisons

T-REx has also been evaluated alongside other mitigation techniques like Dynamic Decoupling (DD) and Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE), revealing that the optimal technique choice depends on the specific circuit, its depth, and the hardware being used [19].

In one study comparing IBM's Kyoto (IBMK) and Osaka (IBMO) processors:

- On

IBMK, T-REx significantly improved the average expected result value of a benchmark quantum circuit from 0.09 to 0.35, moving it closer to the ideal simulator's result of 0.8284 [19]. - This demonstrates T-REx's potent capability to correct results that are severely skewed by readout noise.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Error Mitigation Techniques on Different IBM Processors [19]

| Hardware | Mitigation Technique | Average Expected Result | Variance/Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| IBM Kyoto | None | 0.09 | Not Reported |

| IBM Kyoto | T-REx | 0.35 | Improved |

| IBM Osaka | None | 0.2492 | Not Reported |

| IBM Osaka | Dynamic Decoupling | 0.3788 | Improved |

| Ideal Simulator | - | 0.8284 | - |

Beyond quantum chemistry, T-REx has proven effective in fundamental physics simulations. In studies of the Schwinger model, a lattice gauge theory, T-REx was successfully used alongside ZNE to mitigate errors in circuits calculating particle-density correlations, enabling more accurate observation of non-equilibrium dynamics [22] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers seeking to implement T-REx in their experimental workflow, the following table details the essential "research reagents" and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Components for a T-REx Experiment

| Component / Reagent | Function / Role | Implementation Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NISQ Processor | Provides the physical qubits for executing the quantum algorithm and calibration routines. | IBMQ Belem (5-qubit), IBM Kyoto (127-qubit), IBM Osaka. | |

| Classical Optimizer | Handles the classical optimization loop in VQE, updating parameters to minimize the mitigated energy expectation. | Simultaneous Perturbation Stochastic Approximation (SPSA). | |

| Assignment Matrix Calibration Routine | Automated procedure to run preparation, twirling, and measurement circuits to construct the confusion matrices ( A_i ). | Custom script using Qiskit or Mitiq to run calibration circuits and compute ( p(i | j) ). |

| Twirling Gate Set | The set of gates used to randomize the circuit before measurement, transforming coherent noise into stochastic noise. | The Pauli group ( {I, X} ) applied right before measurement. | |

| Tensor Product Inversion Solver | The computational kernel that performs the least-squares inversion of the approximate global assignment matrix. | A constrained linear solver (e.g., using NumPy or SciPy) to compute ( \vec{p}_{\text{mitigated}} ). | |

| Algorithm Circuit | The core quantum algorithm whose results require mitigation (e.g., for quantum chemistry or dynamics). | A VQE ansatz for BeHâ‚‚ or a Trotterized time-evolution circuit for the Schwinger model. | |

| SB-273005 | SB-273005, CAS:205678-31-5, MF:C22H24F3N3O4, MW:451.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | |

| SB-743921 free base | SB-743921 free base, CAS:618430-39-0, MF:C31H33ClN2O3, MW:517.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrated Workflow for Quantum Chemistry Research

The power of T-REx is fully realized when it is seamlessly integrated into a holistic experimental workflow, from problem definition to the analysis of mitigated results. This is especially critical in quantum chemistry applications like molecular ground-state calculation, where the hybrid quantum-classical loop is sensitive to noise at every iteration. The following diagram maps this complete, integrated research pipeline.

Twirled Readout Error Extinction (T-REx) stands out as a highly cost-effective and practical technique for enhancing the accuracy of quantum computations on current NISQ devices. Its mathematical foundation, which combines twirling for noise simplification with a tensor-product model for scalability, directly addresses the critical problem of measurement error without incurring prohibitive computational overhead. As validated through quantum chemistry experiments, the application of T-REx can be the deciding factor that enables a smaller quantum processor to outperform a much larger, unmitigated one, thereby extending the practical utility of existing hardware for critical research in drug development and materials science. For researchers, mastering the implementation of T-REx, as detailed in this guide, is an essential step towards extracting reliable and scientifically meaningful results from today's noisy quantum computers.

Quantum computers hold significant promise for simulating molecular systems, offering potential solutions to problems that are computationally infeasible for classical computers [24]. In the field of quantum chemistry, algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) are designed to approximate ground state energies of molecular systems [24]. However, current noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices are susceptible to decoherence and operational errors that accumulate during computation, undermining the reliability of results [24]. While quantum error correction codes offer a long-term solution, their hardware requirements exceed current capabilities, making quantum error mitigation (QEM) strategies essential for extracting meaningful results from existing devices [24].

Reference-state error mitigation (REM) represents a cost-effective, chemistry-inspired QEM approach that performs exceptionally well for weakly correlated problems [25] [26] [24]. This method mitigates energy error of a noisy target state measured on a quantum device by first quantifying the effect of noise on a classically-solvable reference state, typically the Hartree-Fock (HF) state [24]. However, the effectiveness of REM becomes limited when applied to strongly correlated systems, such as those encountered in bond-stretching regions or molecules with pronounced electron correlation [25] [26] [24]. This limitation arises because REM assumes the reference state has substantial overlap with the target ground state—an condition not met when a single Slater determinant like HF fails to describe multiconfigurational wavefunctions [24].

This technical guide introduces Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM), an extension of REM that systematically incorporates multireference states to address the challenge of strong electron correlation [25] [26] [24]. By utilizing compact wavefunctions composed of a few dominant Slater determinants engineered to exhibit substantial overlap with the target ground state, MREM significantly improves computational accuracy for strongly correlated systems while maintaining feasible implementation on NISQ devices [24].

Theoretical Foundation: From REM to MREM

The Limitations of Single-Reference Error Mitigation

The REM protocol leverages chemical insight to provide low-complexity error mitigation [24]. The fundamental principle involves using a reference state that is both exactly solvable classically and practical to prepare on a quantum device [24]. The energy error of the target state is mitigated using the formula:

[E{\text{mitigated}} = E{\text{target}}^{\text{noisy}} - (E{\text{reference}}^{\text{noisy}} - E{\text{reference}}^{\text{exact}})]

where (E{\text{target}}^{\text{noisy}}) is the energy of the target state measured on hardware, (E{\text{reference}}^{\text{noisy}}) is the energy of the reference state measured on the same hardware, and (E_{\text{reference}}^{\text{exact}}) is the classically computed exact energy of the reference state [24].

While this approach provides significant error mitigation gains for weakly correlated systems where the HF state offers sufficient overlap with the ground state, it fails dramatically for strongly correlated systems where the true wavefunction becomes a linear combination of multiple Slater determinants with similar weights [24]. In such multireference cases, the single-determinant picture breaks down, and the HF reference no longer provides a reliable foundation for error mitigation [24].

Multireference-State Error Mitigation: Core Conceptual Framework

MREM extends the REM framework by systematically incorporating multireference states to capture quantum hardware noise in strongly correlated ground states [25] [26] [24]. The fundamental modification replaces the single reference state with a set of multireference states ({\ket{\psi_{\text{MR}}^{(i)}}):

[E{\text{mitigated}} = E{\text{target}}^{\text{noisy}} - \sumi wi (E{\text{MR}}^{(i),\text{noisy}} - E{\text{MR}}^{(i),\text{exact}})]

where (w_i) are weights determined by the importance of each reference state [24]. These multireference states are truncated wavefunctions composed of a few dominant Slater determinants selected to maximize overlap with the target ground state while maintaining practical implementability on NISQ devices [24].

A pivotal aspect of MREM is the use of Givens rotations to efficiently construct quantum circuits for generating multireference states [25] [26] [24]. This approach preserves key symmetries such as particle number and spin projection while offering a structured and physically interpretable method for building linear combinations of Slater determinants from a single reference configuration [24].

Methodology: Implementing MREM with Givens Rotations

Givens Rotations for Multireference State Preparation

Givens rotations provide a systematic approach for preparing multireference states on quantum hardware [24]. These rotations implement unitary transformations that mix fermionic modes, effectively creating superpositions of Slater determinants from an initial reference state [24]. The Givens rotation circuit for an (N)-qubit system requires (\mathcal{O}(N^2)) gates and can be decomposed into two-qubit rotations, making them suitable for NISQ devices with limited connectivity [24].

The general form of a Givens rotation gate between modes (p) and (q) is given by:

[G(\theta, \phi) = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \ 0 & \cos(\theta) & -\sin(\theta)e^{-i\phi} & 0 \ 0 & \sin(\theta)e^{i\phi} & \cos(\theta) & 0 \ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \ \end{pmatrix}]

These rotations are universal for quantum chemistry state preparation tasks and are particularly advantageous because they preserve particle number and spin symmetry [24].

Workflow for MREM Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the complete MREM experimental workflow, from classical precomputation to final mitigated energy estimation:

Figure 1: MREM experimental workflow from classical precomputation to final mitigated energy estimation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for MREM

Table 1: Essential computational tools and methods for implementing MREM protocols.

| Research Reagent | Function in MREM Protocol |

|---|---|

| Givens Rotation Circuits | Efficiently prepares multireference states on quantum hardware by creating superpositions of Slater determinants while preserving particle number and spin symmetries [24]. |

| Slater Determinant Selection Algorithm | Identifies dominant configurations from classical multireference calculations (e.g., CASSCF, DMRG) to construct compact, expressive multireference states with high overlap to the target ground state [24]. |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | Hybrid quantum-classical algorithm used to prepare and optimize the target state wavefunction on noisy quantum hardware [24]. |

| Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping | Transforms the electronic Hamiltonian from second quantization to qubit representation using encodings such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformations [24]. |

| Classical Post-Processing Module | Implements the MREM correction formula to compute mitigated energies using noisy quantum measurements and classically exact reference values [24]. |

| SC-236 | SC-236, CAS:170569-86-5, MF:C16H11ClF3N3O2S, MW:401.8 g/mol |

| SC-560 | SC-560, CAS:188817-13-2, MF:C17H12ClF3N2O, MW:352.7 g/mol |

Experimental Protocols and Computational Details

Molecular Systems and Hardware Specifications

The effectiveness of MREM was demonstrated through comprehensive simulations of the molecular systems H(2)O, N(2), and F(2) [26] [24]. These molecules were selected to represent a range of electron correlation strengths, with F(2) exhibiting particularly strong correlation effects that challenge single-reference methods [24]. The experiments employed variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) algorithms with unitary coupled cluster (UCC) ansätze to prepare target ground states [24].

Quantum simulations incorporated realistic noise models based on characterization of superconducting qubit architectures, including gate infidelities, depolarizing noise, and measurement errors [24]. The molecular geometries were optimized at the classical level, and Hamiltonians were generated in the STO-3G basis set before transformation to qubit representations using the Jordan-Wigner mapping [24].

State Preparation and Circuit Construction

Multireference states were constructed by selecting dominant Slater determinants from classically computed wavefunctions, then implementing them on quantum hardware using Givens rotation circuits [24]. The following diagram illustrates the core MREM algorithmic structure and its relationship to the standard REM approach:

Figure 2: Core MREM algorithm extending REM framework with multiple reference states prepared via Givens rotations.

For each molecular system, the multireference states were engineered as linear combinations of 3-5 dominant determinants selected based on their coefficients in classically computed configuration interaction wavefunctions [24]. The Givens rotation circuits were optimized to minimize depth and two-qubit gate count, with specific attention to the connectivity constraints of target hardware architectures [24].

Results and Performance Analysis

Comparative Performance Across Molecular Systems

MREM demonstrated significant improvements in computational accuracy compared to both unmitigated VQE results and the original REM method across all tested molecular systems [25] [26] [24]. The following table summarizes the key performance metrics:

Table 2: Comparative performance of MREM against unmitigated VQE and single-reference REM for molecular systems Hâ‚‚O, Nâ‚‚, and Fâ‚‚. Energy errors are reported in millihartrees.

| Molecular System | Correlation Strength | Unmitigated VQE Error (mEh) | REM Error (mEh) | MREM Error (mEh) | Error Reduction vs REM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚O | Weak | 45.2 | 12.8 | 5.3 | 58.6% |

| Nâ‚‚ | Moderate | 68.7 | 25.4 | 9.1 | 64.2% |

| Fâ‚‚ | Strong | 142.5 | 89.6 | 21.3 | 76.2% |

The results clearly show that MREM provides substantially better error mitigation than single-reference REM, with the most dramatic improvement occurring in the strongly correlated F(_2) system where the error was reduced by 76.2% compared to conventional REM [24]. This pattern confirms the theoretical expectation that MREM specifically addresses the limitations of single-reference approaches in strongly correlated systems.

Analysis of Overlap and State Expressivity