Meredith Gwynne Evans: The Unsung Architect of Chemical Reactions

Exploring the groundbreaking contributions of M.G. Evans to transition state theory and chemical kinetics

Introduction: The Hidden Architect of Chemical Transformations

In the intricate world of chemical reactions—from the metabolic processes sustaining life to the industrial synthesis revolutionizing technology—lies a fundamental question: how do molecules actually transform from reactants to products? This mystery captivated a brilliant but often overlooked British chemist, Meredith Gwynne Evans, whose pioneering work in the 1930s laid the foundation for our modern understanding of chemical reaction mechanisms.

Alongside scientific luminaries like Henry Eyring and Michael Polanyi, Evans helped develop the transition state theory, a conceptual framework that explains the fleeting moment when chemical bonds break and form 1 . Though his name may not be as widely recognized as some of his contemporaries, Evans' contributions continue to resonate through laboratories worldwide, enabling advancements in fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to materials science.

Key Concepts and Theories: Visualizing the Invisible

At the heart of Evans' work lies a deceptively simple question: what exactly happens during the infinitesimal moment when reactants transform into products? Before transition state theory, chemists struggled to explain why some reactions occurred rapidly while others proceeded slowly, or why temperature dramatically affected reaction rates.

Evans and his collaborators proposed that molecules must overcome an energy barrier—passing through a fleeting transition state that is neither reactant nor product but something in between 1 .

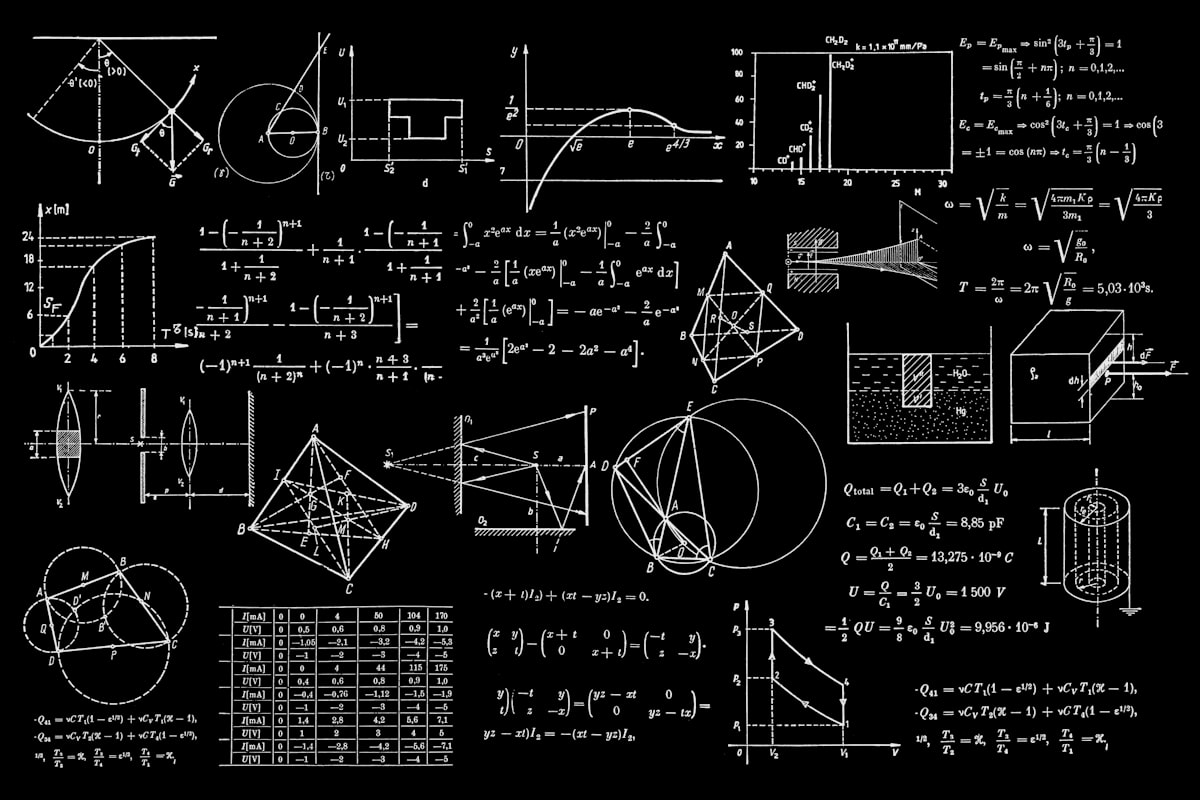

What set Evans' approach apart was his pioneering integration of quantum mechanics with traditional chemistry. During his time at the University of Manchester, Evans collaborated with physicists like Douglas Hartree and Lawrence Bragg to apply quantum principles to chemical problems 1 .

This interdisciplinary approach allowed him to visualize molecular interactions at an unprecedented level, considering how electrons and atomic orbitals rearrange during reactions.

In-Depth Look at a Key Experiment: Unveiling Reaction Mysteries in Solution

The 1935 Collaboration with Michael Polanyi

While Henry Eyring was publishing similar work at Princeton, Evans and Polanyi were conducting groundbreaking research at the University of Manchester. Their seminal 1935 paper published in the Transactions of the Faraday Society titled "Some applications of the transition state method to the calculation of reaction velocities, especially in solution" represented a quantum leap in understanding chemical kinetics 1 .

This research was particularly significant because it extended transition state theory beyond gas-phase reactions to reactions in solution—a more complex environment due to solvent molecules influencing reaction pathways. Their work provided chemists with mathematical tools to predict how quickly chemical reactions would occur under various conditions, a fundamental capability that underpins everything from drug design to materials synthesis.

Methodology: Step-by-Step Scientific Detective Work

Evans and Polanyi's approach combined theoretical brilliance with practical scientific investigation:

Theoretical Framework Development

They first established mathematical equations describing how the transition state—an activated complex with partial bonds—exists in equilibrium with reactants before decomposing into products.

Quantum Mechanical Calculations

Using the emerging principles of quantum mechanics, they calculated potential energy surfaces for simple reactions, mapping how energy changes as molecules approach, interact, and transform.

Experimental Validation

Though primarily theoretical, their work drew upon experimental data from various chemical reactions to validate their equations. They paid particular attention to how solvents affect reaction rates by stabilizing or destabilizing the transition state.

Mathematical Formulation

They derived equations relating reaction rates to temperature, activation energy, and entropy changes, allowing predictions about how reaction rates would change under different conditions.

| Concept | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Activated Complex | A transient state where bonds are breaking and forming | Explained why reactions have energy barriers |

| Solvation Effects | How solvent molecules influence transition state stability | Extended theory beyond gas-phase reactions |

| Transmission Coefficient | Probability that activated complex becomes products | Refined accuracy of reaction rate predictions |

| Entropy of Activation | Measure of molecular organization in transition state | Explained why some reactions are faster than others |

Results and Analysis: Revolutionizing Chemical Prediction

The core results of Evans and Polanyi's work transformed chemical kinetics:

Quantitative Predictive Power

Their equations successfully predicted reaction rates for various systems based on fundamental molecular properties, reducing the need for extensive experimental measurement.

Solvent Effects Explained

They demonstrated how polar solvents accelerate reactions by stabilizing charged transition states, providing the first theoretical framework for understanding solvent effects on reaction rates.

Connection to Thermodynamics

Their work beautifully connected kinetics (reaction rates) with thermodynamics (equilibrium constants), revealing the deep unity of chemical principles.

Activation Parameters

They established methods to determine the entropy and enthalpy of activation—key parameters that provide insight into the molecular organization and energy changes occurring during the transition state.

| Reaction Type | Experimental Activation Energy (kJ/mol) | Calculated Activation Energy (kJ/mol) | Deviation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H + H₂ → H₂ + H | 32.8 | 33.5 | 2.1 |

| CH₃ + H₂ → CH₄ + H | 34.3 | 35.1 | 2.3 |

| C₂H₅I → C₂H₄ + HI | 168 | 172 | 2.4 |

| Solvolysis of t-butyl chloride | 89.5 | 91.2 | 1.9 |

| Reaction | Solvent | Dielectric Constant | Predicted Rate Increase | Experimental Rate Increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SN1 reaction | Water | 80.1 | 1.0 × 10⁶ | 2.5 × 10⁶ |

| Ester hydrolysis | Ethanol | 24.3 | 1.8 × 10² | 2.1 × 10² |

| Ion recombination | Benzene | 2.3 | 0.85 × 10⁻³ | 1.2 × 10⁻³ |

| Electrophilic substitution | Nitromethane | 35.9 | 3.5 × 10³ | 5.2 × 10³ |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development of transition state theory required both theoretical brilliance and experimental ingenuity. Below are key research tools that Evans and his contemporaries employed:

Zeolite Crystals

Model systems for molecular interactionsQuantum Mechanical Calculations

Describing electron behaviorTemperature-Controlled Vessels

Precise kinetic measurementsVacuum Systems

Studying gas-phase reactionsSolvent Purification Systems

For solution chemistry studiesSpectroscopic Equipment

Identifying reaction productsLegacy: The Enduring Impact of a Scientific Visionary

Meredith Gwynne Evans died tragically young on Christmas Day in 1952 at just 48 years of age 1 . Yet his scientific legacy continues to shape modern chemistry. The transition state theory he helped develop forms the conceptual foundation for:

Drug Design

Materials Science

Environmental Chemistry

Catalysis

"The most brilliant chemist he had ever met" — George Porter (Nobel Laureate, 1967) on M.G. Evans 1

Evans' legacy also lives on through his remarkable students, including George Porter, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1967 for his work on flash photolysis 1 .

Though less celebrated than some of his contemporaries, Meredith Gwynne Evans exemplifies how theoretical insight can transform our understanding of the molecular world. His work reminds us that the most significant scientific advances often come from collaborative efforts to solve fundamental problems—and that these advances continue to shape our world in ways both visible and invisible.