Modeling Quantum Noise for Accurate Chemistry Simulations: A Guide to Depolarizing and Amplitude Damping Channels in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical role of quantum noise models, specifically depolarizing and amplitude damping channels, in computational chemistry simulations...

Modeling Quantum Noise for Accurate Chemistry Simulations: A Guide to Depolarizing and Amplitude Damping Channels in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical role of quantum noise models, specifically depolarizing and amplitude damping channels, in computational chemistry simulations on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. We explore the fundamental physics behind these noise types, their distinct impacts on quantum algorithms like VQE, and methodological approaches for their integration into chemical simulation workflows. The content further covers advanced error mitigation strategies, validation techniques for assessing model accuracy, and comparative analyses of noise resilience across different algorithmic approaches. By synthesizing the latest research and practical implementation strategies, this work aims to equip scientists with the knowledge needed to develop more reliable and predictive quantum chemistry simulations for biomedical applications.

Understanding Quantum Noise: The Fundamental Challenge in Chemical Simulation on NISQ Devices

The Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era represents the current technological frontier in quantum computing, characterized by processors containing 50 to 1,000 physical qubits that operate without full error correction [1]. For quantum chemistry applications, including molecular energy estimation and drug discovery, these devices present both unprecedented opportunities and fundamental limitations. This technical guide analyzes the core constraints of NISQ hardware through the lens of quantum noise models relevant to chemistry simulations, detailing experimental methodologies for overcoming these limitations while providing quantitative resource assessments and practical toolkits for researchers in pharmaceutical and materials science domains.

Fundamental NISQ Hardware Limitations

NISQ devices are defined by strict physical constraints that directly impact their utility for quantum chemistry applications. These limitations emerge from current technological boundaries in qubit fabrication, control, and maintenance of quantum coherence.

Physical Resource Constraints

Quantum computers in the NISQ era operate with severe resource restrictions that bound the complexity of executable algorithms [2]. The table below summarizes the key hardware limitations across major qubit platforms:

Table 1: NISQ Hardware Performance Metrics Across Platforms

| Platform | Qubit Count Range | 2-Qubit Gate Fidelity (%) | Coherence Times (Tâ‚/Tâ‚‚) | Gate Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superconducting (e.g., IBM, Google) | 27-1000+ | 98.6-99.7 [3] | 10-100 μs [3] | 20-100 ns [3] |

| Trapped Ions (e.g., IonQ, Quantinuum) | 11-50 | 99.8-99.9 [3] | 1-10 seconds [3] | 50-200 μs [3] |

| Neutral Atoms (e.g., Pasqal) | ~100 | 97-99 [3] | 0.1-1 seconds [3] | ~1 ms [3] |

The total number of gates executable before decoherence dominates is determined by N·d·ε ≪ 1, where N is the qubit count, d is the circuit depth, and ε is the two-qubit error rate [3]. This relation fundamentally constrains the algorithmic complexity achievable on NISQ devices.

Quantum Noise Models and Their Impact

For quantum chemistry simulations, understanding specific noise models is essential for developing effective error mitigation strategies. The most prevalent models include:

Unital Noise Models (Depolarizing Noise)

Depolarizing noise represents a symmetric, unital noise model that randomly replaces the current state with the maximally mixed state with probability p. For a single qubit, this channel can be represented as: Λâ‚(Ï) = (1-p)Ï + p(I/2) [4]

This model is strictly contractive and drives any quantum state toward the maximally mixed state [4]. Under such noise, the relative entropy between the state Ï(t) and the maximally mixed state diminishes as D(Ï(t)∥σ₀) ≤ nμᵗ, where σ₀ = I/2â¿ is the n-qubit maximally mixed state and μ < 1 is the contractive rate [4]. For quantum chemistry applications, this presents particular challenges for maintaining coherent superposition states essential for molecular orbital simulations.

Non-Unital Noise Models (Amplitude Damping)

Amplitude damping represents non-unital noise that models energy dissipation, a physically relevant model for molecular systems. Unlike unital noise, amplitude damping has a unique fixed point and does not necessarily drive all states toward the maximally mixed state [5]. Recent research has identified that while unital noise always induces Noise-Induced Barren Plateaus (NIBPs), Hilbert-Schmidt contractive non-unital noise (including amplitude damping) does not necessarily lead to barren plateaus, suggesting some noise types may be less detrimental to variational quantum algorithms [5].

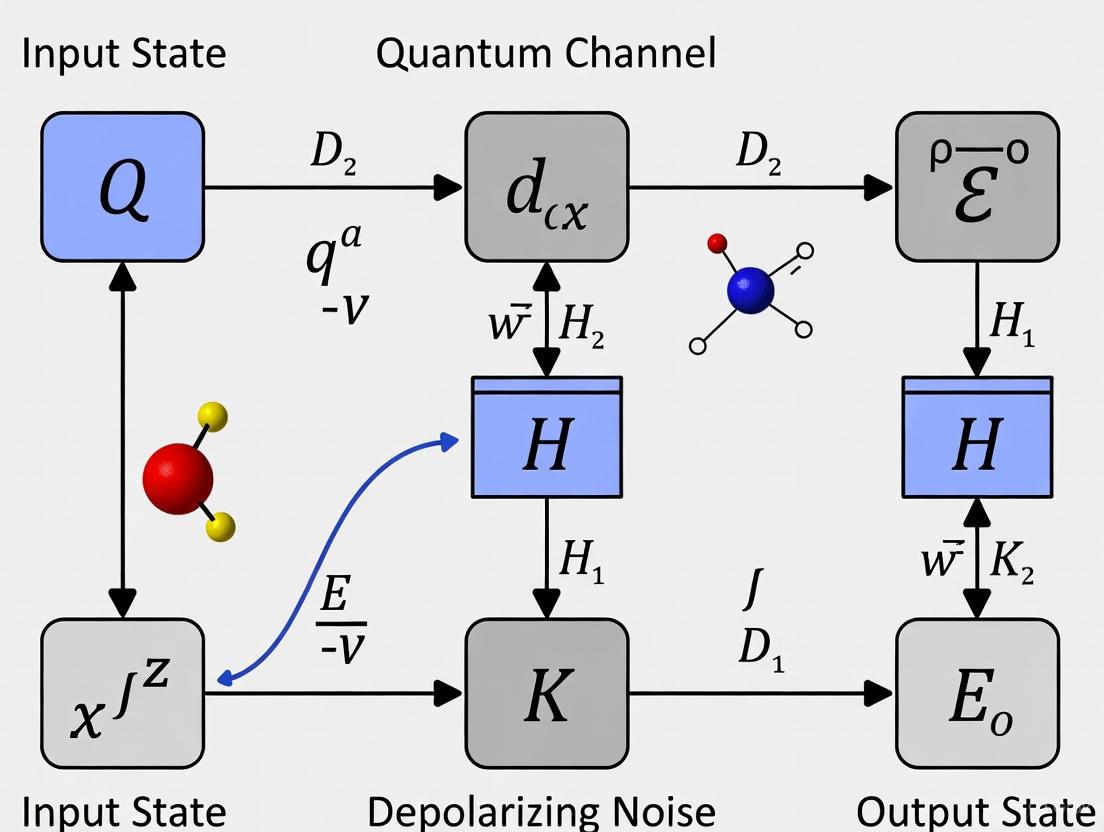

Diagram Title: NISQ Noise Model Effects on Quantum States

Algorithmic Limitations for Chemistry Applications

Theoretical Performance Boundaries

Recent complexity-theoretic results establish fundamental limitations for NISQ devices in quantum chemistry applications. For strictly contractive unital noise, quantum devices become statistically indistinguishable from random circuits when depths exceed Ω(log(n)) [4]. Even with classical processing, devices with super-logarithmic circuit depths fail to deliver quantum advantage for polynomial-time algorithms [4].

Spatial connectivity constraints further limit performance. For one-dimensional noisy qubit circuits, super-polynomial quantum advantages are ruled out in all-depth regimes, with entanglement generation capped at O(log(n)) for 1D circuits and O(√nlog(n)) for 2D circuits [4]. These bounds directly impact the simulation of complex molecular systems requiring high entanglement.

Practical Algorithmic Constraints

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), the leading NISQ algorithm for quantum chemistry, faces multiple practical constraints:

- Measurement Overhead: Resource estimates scale as S ∼ O(Nâ´/ϵ²) shots per iteration to achieve chemical accuracy [3]

- Gate Fidelity Requirements: Achieving chemical accuracy requires gate fidelities of ε < 10â»â´ to 10â»â¶ [3]

- Noise-Induced Barren Plateaus: Both unital and certain non-unital noise models cause exponentially small gradients in variational algorithms [5]

- Circuit Depth Limits: Current hardware constraints cap circuit depths at O(10²-10³) gates [3]

Table 2: Resource Requirements for Chemical Accuracy in Molecular Simulations

| Molecule | Qubits Required | Pauli Terms | Circuit Depth | Estimated Shots |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BODIPY-4 (8e8o) | 8 | 361 [6] | ~10² | 10âµ-10ⶠ|

| BODIPY-4 (14e14o) | 28 | 55,323 [6] | ~10³ | 10â·-10⸠|

| FeMoco (Nitrogenase) | ~1,000,000 (estimated) [7] | ~10¹² (estimated) | >10ⷠ| >10¹ⵠ|

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

High-Precision Measurement Techniques

Achieving chemical precision (1.6×10â»Â³ Hartree) on NISQ devices requires specialized measurement protocols. Recent experimental demonstrations on IBM Eagle processors have reduced measurement errors from 1-5% to 0.16% through integrated techniques [6]:

Protocol 1: Locally Biased Random Measurements

This technique reduces shot overhead by preferentially selecting measurement settings that have greater impact on energy estimation. The protocol maintains the informationally complete nature of measurements while optimizing resource allocation:

- Initialization: Prepare Hartree-Fock state on quantum processor

- Hamiltonian Segmentation: Decompose molecular Hamiltonian into Pauli terms

- Setting Selection: Apply biased selection toward high-weight Pauli terms

- Execution: Implement selected measurement settings on hardware

- Iteration: Update bias based on preliminary results

Protocol 2: Quantum Detector Tomography with Repeated Settings

This approach addresses circuit overhead and readout errors through parallel quantum detector tomography:

- Circuit Design: Implement informationally complete measurement circuits

- Parallel Tomography: Execute quantum detector tomography circuits alongside main computation

- Noise Characterization: Construct noisy measurement effects matrix P(m|s)

- Inversion: Apply Pâ»Â¹ to raw measurements to mitigate readout errors

- Validation: Verify mitigation efficacy through consistency checks

Protocol 3: Blended Scheduling for Time-Dependent Noise

Temporal noise variations pose significant barriers to high-precision measurements. Blended scheduling intersperses different circuit types to mitigate time-dependent noise effects:

- Circuit Grouping: Organize circuits by type (QDT, Hamiltonian terms)

- Temporal Interleaving: Execute circuits from different groups in sequence

- Noise Tracking: Monitor temporal noise patterns via calibration circuits

- Post-Processing: Apply temporal noise correction models

Diagram Title: High-Precision Measurement Workflow

Solvent-Ready Algorithm Implementation

Recent advances enable simulation of solvated molecules, critical for biologically relevant chemistry. The SQD-IEF-PCM (Sample-based Quantum Diagonalization with Integral Equation Formalism Polarizable Continuum Model) protocol represents a significant step toward practical quantum chemistry [8]:

- Wavefunction Sampling: Generate electronic configurations from molecular wavefunction using quantum hardware

- Noise Correction: Apply self-consistent process (S-CORE) to restore physical properties (electron number, spin)

- Subspace Construction: Build manageable subspace from corrected configurations for classical processing

- Solvent Incorporation: Add solvent effect as perturbation to molecular Hamiltonian using IEF-PCM

- Self-Consistent Iteration: Update molecular wavefunction until solvent and solute reach mutual consistency

Experimental implementation on IBM quantum computers with 27 to 52 qubits has demonstrated solvation free energies matching classical benchmarks within 0.2 kcal/mol for methanol [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Experimental Components for NISQ Quantum Chemistry

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements | Enables estimation of multiple observables from same measurement data [6] | Locally biased random measurements for reduced shot overhead |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | Mitigates readout errors by characterizing noisy measurement effects [6] | Parallel QDT execution alongside main quantum circuits |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Improves result accuracy without quantum error correction [1] | Zero-noise extrapolation, probabilistic error cancellation, symmetry verification |

| Hybrid Quantum-Classical Algorithms | Leverages classical resources to reduce quantum circuit demands [9] | VQE for ground state energy estimation, QAOA for optimization |

| Implicit Solvent Models | Incorporates solvent effects without explicit solvent molecules [8] | IEF-PCM for solvation energy calculation in aqueous solutions |

| Dynamic Compilation | Adapts circuits to hardware constraints and noise profiles [3] | Calibration-aware qubit placement and routing |

| Ki16425 | Ki16425, CAS:355025-24-0, MF:C23H23ClN2O5S, MW:475.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| L-167307 | L-167307, CAS:188352-45-6, MF:C22H17FN2OS, MW:376.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Future Perspectives: Beyond the NISQ Era

The transition from NISQ to Fault-Tolerant Application-Scale Quantum (FASQ) computing requires overcoming multiple technological hurdles. Current estimates suggest that a modest 1,000 logical-qubit processor would require approximately one million physical qubits with current error rates [10]. While error mitigation techniques provide a temporary bridge, their sampling overhead grows exponentially with circuit size [10].

Promising developments include new qubit designs such as fluxonium and cat qubits that may reduce error correction overhead, and algorithmic advances that identify "proof pockets" - specific subproblems where quantum methods demonstrate clear advantages [10]. For quantum chemistry, the first practical applications are likely to emerge in specialized simulation domains before expanding to broader commercial applications in pharmaceutical and materials science [10].

The scientific toolkit presented herein provides researchers with practical methodologies for extracting meaningful chemical insights from current NISQ devices while the field progresses toward fault-tolerant quantum computation capable of addressing industrially relevant molecular systems.

This technical guide provides a comprehensive examination of depolarizing noise, a critical model for describing non-coherent errors in quantum information processing. We present the complete mathematical formulation of the depolarizing channel using Kraus operators and detail its impact on quantum systems. Framed within quantum chemistry simulations, this review explores how depolarizing noise and other error models affect the accuracy of quantum computations for chemical systems, contrasting its universally detrimental effects with the context-dependent impacts of amplitude damping noise. We further synthesize current experimental protocols for noise characterization and mitigation, providing researchers with essential tools for evaluating and countering noise in near-term quantum devices.

Quantum computation holds revolutionary potential for simulating molecular systems and chemical reactions, a task that remains intractable for classical computers as system size increases [11] [12]. However, current quantum processors operate in the noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) era, where quantum information is highly susceptible to corruption from environmental interactions and imperfect control [13] [14]. These disruptive processes are formally described using quantum noise models—mathematical representations of how quantum states evolve when coupled to an external environment.

The most prevalent noise models include:

- Depolarizing Noise: A non-coherent, unital process that randomly applies Pauli operators to a qubit with equal probability.

- Amplitude Damping: A non-unital process modeling energy dissipation from an excited state to a ground state.

- Phase Damping: A coherent dephasing process that destroys phase information without energy loss.

Understanding these models, particularly their mathematical structure through Kraus operators and their physical implications for quantum algorithms, is prerequisite for developing effective error suppression and correction techniques in quantum computational chemistry.

Mathematical Formulation of the Depolarizing Channel

Kraus Operator Formalism

Quantum noise processes are formally described by completely positive trace-preserving (CPTP) maps, which guarantee the physical validity of the transformed quantum state. The most general representation of a CPTP map is the Kraus operator sum representation:

$$ \mathcal{E}(\rho) = \sum{k} A{k} \rho A_{k}^{\dagger} $$

where $\rho$ is the density matrix of the quantum state, and the Kraus operators $A{k}$ satisfy the completeness relation $\sum{k} A{k}^{\dagger} A{k} = I$ to ensure trace preservation [15].

Single-Qubit Depolarizing Channel

The single-quit depolarizing channel represents a process where the qubit remains unchanged with probability $1-p$, or undergoes randomization via Pauli $X$, $Y$, or $Z$ errors with equal probability $p/3$. This channel is described by four Kraus operators:

$$ \begin{aligned} A0 &= \sqrt{1-p} \, I \ A1 &= \sqrt{\frac{p}{3}} \, X \ A2 &= \sqrt{\frac{p}{3}} \, Y \ A3 &= \sqrt{\frac{p}{3}} \, Z \end{aligned} $$

where $I, X, Y, Z$ are the Pauli matrices. The action of the depolarizing channel on a quantum state $\rho$ is therefore:

$$ \mathcal{E}_{\text{depol}}(\rho) = (1-p)\rho + \frac{p}{3}(X\rho X + Y\rho Y + Z\rho Z) $$

This formulation reveals the depolarizing channel as a Pauli channel with equal weights for all non-identity Pauli operations. For a single qubit, the depolarizing channel can be alternatively expressed as:

$$ \mathcal{E}_{\text{depol}}(\rho) = (1-p)\rho + p \frac{I}{2} $$

which clearly shows the state being replaced with the maximally mixed state $I/2$ with probability $p$.

Multi-Qubit and Correlated Depolarizing Noise

For multi-qubit systems, the depolarizing channel can be generalized to include both local depolarizing noise (affecting qubits independently) and correlated depolarizing noise (simultaneously affecting multiple qubits). The cluster expansion approach provides a systematic framework for constructing approximate noise channels by incorporating noise components with increasing degrees of qubit-qubit correlation [16].

A $k$-th order approximate channel incorporates correlations up to degree $k$, with the full noise model requiring resources growing exponentially with the number of qubits. This approach enables honest noise modeling—where actual errors are not underestimated—which is crucial for predicting the performance of quantum error correction codes.

Table 1: Key Properties of Common Single-Qubit Noise Channels

| Noise Channel | Kraus Operators | Type | Qubit Effect | Invertible | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depolarizing | $A0 = \sqrt{1-p}I$, $A1 = \sqrt{p/3}X$, $A2 = \sqrt{p/3}Y$, $A3 = \sqrt{p/3}Z$ | Unital | Identity with prob. $1-p$, random Pauli with prob. $p/3$ each | Yes (non-CP) | ||

| Amplitude Damping | $A0 = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & \sqrt{1-\gamma} \end{bmatrix}$, $A1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & \sqrt{\gamma} \ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}$ | Non-unital | Energy dissipation: $ | 1\rangle \rightarrow | 0\rangle$ with prob. $\gamma$ | Yes (non-CP) |

| Phase Damping | $A0 = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & \sqrt{1-\lambda} \end{bmatrix}$, $A1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 \ 0 & \sqrt{\lambda} \end{bmatrix}$ | Unital | Loss of phase coherence without energy loss | Yes (non-CP) |

Comparative Analysis of Noise Channels in Quantum Chemistry

Impact on Quantum Algorithms for Chemistry

Different noise profiles distinctly impact quantum algorithms central to chemistry simulations, such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE).

Depolarizing noise consistently degrades performance across all circuit depths and error probabilities. Its unital nature introduces uniform randomization that directly corrupts quantum information, making it particularly detrimental to algorithms requiring precise phase relationships [13].

Amplitude damping noise exhibits more complex behavior. Surprisingly, in shallow quantum circuits (depths of 10-15 gates) with small error rates ($p=0.0005$), amplitude damping can actually improve performance in certain quantum machine learning tasks like quantum reservoir computing compared to noiseless reservoirs [13]. This beneficial effect occurs when the fidelity between noisy and noiseless states remains above 0.96 [13].

Phase damping noise primarily destroys phase coherence, disproportionately affecting algorithms reliant on quantum interference patterns. Its impact falls between depolarizing and amplitude damping in severity [13].

Implications for Chemical Accuracy

For quantum chemistry simulations to provide predictive value, they must achieve chemical accuracy—typically defined as an error of 0.0016 hartree (approximately 1 kcal/mol) in energy calculations [17]. Recent experiments on Quantinuum's H2-2 trapped-ion quantum computer utilizing quantum error correction have reached errors of 0.018 hartree for molecular hydrogen—above chemical accuracy but demonstrating meaningful progress [17].

Table 2: Noise Impact on Quantum Chemistry Simulation Metrics

| Performance Metric | Depolarizing Noise | Amplitude Damping Noise | Phase Damping Noise |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ground State Energy Calculation | Consistently detrimental across all error rates | Can be beneficial in shallow circuits with low error rates | Generally detrimental, but less severe than depolarizing |

| Algorithm Trainability | Induces noise-induced barren plateaus | Context-dependent effects; can sometimes improve generalization | Contributes to barren plateaus |

| Quantum Error Correction Overhead | Requires full surface code protection | May leverage bias-tailored codes for more efficient protection | May leverage bias-tailored codes for more efficient protection |

| Achievable Circuit Depth | Severely limited without correction | Moderate limitations; some beneficial effects in NISQ regime | Moderate limitations |

Visualization of the Depolarizing Channel's Effect

The following diagram illustrates the quantum state transformation through a depolarizing noise channel and its relationship to other quantum processes in chemistry simulations:

Experimental Protocols for Noise Characterization and Mitigation

Noise Deconvolution Technique

Noise deconvolution provides a post-processing method to remove known noise effects from measurement statistics. For an observable $O$ measured on a state affected by a known noise channel $\mathcal{E}$, the noise-free expectation value can be estimated as:

$$ \langle O \rangle{\text{mitig}} = c \langle O \rangle{\text{noisy}} $$

where the factor $c$ depends on the specific noise channel and its parameters [15]. This technique applies mathematical inversion of the noise map—which is typically not a completely positive map—as a classical post-processing step rather than a physical reversal.

The depolarizing channel admits an inverse map that can be applied through this deconvolution approach, though it comes at the cost of increased estimation variance: $\operatorname{Var}[\langle O \rangle{\mathrm{mitig}}] \sim c^{2} \operatorname{Var}[\langle O \rangle{\mathrm{noisy}}]$, requiring increased sampling to maintain precision [15].

Quantum Error Correction Approaches

For depolarizing noise in quantum chemistry applications, recent experiments have demonstrated complete quantum chemistry simulations using quantum error correction (QEC). Quantinuum researchers implemented the seven-qubit color code to protect logical qubits, inserting mid-circuit error correction routines during quantum phase estimation calculations for molecular hydrogen [17].

This approach showed improved performance despite increased circuit complexity, challenging the assumption that error correction necessarily adds more noise than it removes in near-term devices. The experiment utilized up to 22 qubits with over 2,000 two-qubit gates, achieving energy estimates within 0.018 hartree of the exact value [17].

Resource-Efficient Alternatives

Given the significant overhead of full quantum error correction, researchers have developed partial fault-tolerant methods that trade off some error protection for lower resource requirements. These include:

- Bias-tailored codes that specifically target the most common error types

- Repetition cat qubits that exploit hardware-level protection against bit-flip errors, reducing the surface code overhead required for fault tolerance [11]

- Dynamic decoupling techniques to suppress memory noise during qubit idling

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Noise Mitigation

| Tool/Technique | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Noise Deconvolution | Classical post-processing to invert known noise channels | Increases measurement variance; requires accurate noise characterization |

| Quantum Error Correction Codes | Active protection of logical qubits using redundancy | High qubit overhead; requires specific connectivity (e.g., surface code, color code) |

| Probabilistic Error Cancellation | Quantum circuit sampling with inverse noise maps | Active mitigation requiring quantum circuit regeneration |

| Cat Qubits | Hardware-level bit-flip suppression using repetition codes | 27× reduction in physical qubits compared to transmons for same logical performance [11] |

| Cluster Expansion Approximation | Systematic noise modeling with controlled accuracy | Honest noise modeling that doesn't underestimate errors [16] |

Depolarizing noise represents a fundamental challenge in quantum computational chemistry due to its uniformly detrimental effect on quantum information. Its mathematical formulation through Kraus operators provides the foundation for developing effective mitigation strategies, including noise deconvolution and quantum error correction. Current research demonstrates that while depolarizing noise consistently degrades algorithm performance, careful characterization and targeted error suppression can extend the computational reach of near-term quantum devices for chemistry applications. The differential impact of various noise channels—particularly the context-dependent effects of amplitude damping versus the uniformly detrimental nature of depolarizing noise—highlights the importance of noise-aware algorithm design and platform-specific optimization in the pursuit of quantum advantage for chemical simulation.

In the realm of quantum computing and simulation, noise presents a fundamental challenge to accurate information processing. Among the various types of quantum noise, amplitude damping (AD) holds particular significance for modeling energy relaxation processes that occur naturally in physical systems, including molecular simulations [18]. This quantum channel provides a rigorous framework for describing the spontaneous emission of energy from an excited state to a ground state, making it indispensable for simulating realistic quantum systems in chemistry and materials science [19].

The particular relevance of amplitude damping stems from its ability to model energy dissipation due to system-environment coupling, a process ubiquitous in molecular systems and quantum devices [18] [20]. Unlike unital noise channels like depolarizing noise, amplitude damping is non-unital, meaning it does not preserve the identity operator, leading to unique effects on quantum states that more accurately reflect physical decay processes [20] [5]. This characteristic makes AD noise especially important for quantum simulations of chemical and biological systems where energy transfer and relaxation are fundamental processes.

Within the context of quantum noise models for chemistry simulations, understanding amplitude damping is crucial for several reasons. First, it enables researchers to model realistic environmental interactions in molecular dynamics simulations. Second, it provides insights into the fundamental limitations of current noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices for computational chemistry [21] [22]. Finally, developing mitigation strategies specifically tailored to amplitude damping noise can enhance the accuracy and reliability of quantum chemistry calculations on emerging quantum hardware [18] [23].

Mathematical Foundation of Amplitude Damping

Kraus Operator Formalism

Amplitude damping is mathematically described as a completely positive trace-preserving (CPTP) map, which can be represented using the Kraus operator formalism [18] [19]. For a single qubit, the AD channel, denoted as â„°_AD, transforms an input state Ï according to:

â„°AD(Ï) = ∑i Ki Ï Ki^â€

where the Kraus operators {Ki} satisfy the completeness relation ∑i Ki^†Ki = I to ensure trace preservation [18] [22]. For the amplitude damping channel, these operators are explicitly defined as:

- K₀ = |0⟩⟨0| + √(1-γ)|1⟩⟨1| = [ \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & \sqrt{1-\gamma} \end{pmatrix} ]

- K₠= √γ|0⟩⟨1| = [ \begin{pmatrix} 0 & \sqrt{\gamma} \ 0 & 0 \end{pmatrix} ]

Here, the damping parameter γ ∈ [0,1] represents the probability of energy dissipation from the excited state |1⟩ to the ground state |0⟩ during the noise interval [18]. Physically, γ encapsulates the rate of energy loss to the environment, with γ = 0 corresponding to no damping and γ = 1 representing complete decay to the ground state.

Effect on Quantum States

The action of the amplitude damping channel on a single qubit density matrix Ï = [ \begin{pmatrix} Ï₀₀ & Ï₀₠\ Ïâ‚â‚€ & Ïâ‚â‚ \end{pmatrix} ] transforms it according to:

â„°_AD(Ï) = [ \begin{pmatrix} Ï₀₀ + γÏâ‚â‚ & \sqrt{1-γ}Ï₀₠\ \sqrt{1-γ}Ïâ‚â‚€ & (1-γ)Ïâ‚â‚ \end{pmatrix} ]

This transformation reveals several key characteristics of amplitude damping [19]:

- The population of the excited state (Ïâ‚â‚) decays at a rate γ

- The coherence terms (Ï₀₠and Ïâ‚â‚€) are attenuated by a factor of √(1-γ)

- The ground state population increases as the excited state decays

Unlike phase damping or depolarizing noise, amplitude damping specifically drives the system toward the ground state |0⟩⟨0|, modeling the physical process of energy relaxation that occurs in real quantum systems due to spontaneous emission or interactions with a zero-temperature environment.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Single-Qubit Noise Channels

| Noise Channel | Kraus Operators | Effect on States | Unital/Non-unital | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude Damping | K₀ = [ \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & \sqrt{1-\gamma} \end{pmatrix} ], K₠= [ \begin{pmatrix} 0 & \sqrt{\gamma} \ 0 & 0 \end{pmatrix} ] | Energy loss toward | 0⟩ | Non-unital |

| Phase Damping | Kâ‚€ = [ \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & \sqrt{1-\lambda} \end{pmatrix} ], Kâ‚ = [ \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 0 \ 0 & \sqrt{\lambda} \end{pmatrix} ] | Loss of phase coherence | Unital | |

| Depolarizing | K₀ = √(1-p)I, K₠= √(p/3)X, K₂ = √(p/3)Y, K₃ = √(p/3)Z | Random Pauli errors | Unital | |

| Bit Flip | K₀ = √(1-p)I, K₠= √(p)X | Bit flip with probability p | Unital |

Physical Interpretation and Relevance to Molecular Systems

Modeling Energy Relaxation

In molecular and quantum chemical systems, amplitude damping provides a crucial model for energy dissipation processes where a quantum system loses energy to its environment. This occurs through various mechanisms, including spontaneous emission, vibrational relaxation, and energy transfer to solvent molecules in solution-phase chemistry [19]. The AD channel effectively captures the fundamental process of a two-level system transitioning from an excited state to a ground state while transferring energy to its surroundings.

The physical significance of amplitude damping in molecular simulations becomes apparent when considering processes such as:

- Electronic transitions in molecules, where excited electrons relax to lower energy states

- Vibrational relaxation, where highly excited vibrational modes dissipate energy to their environment

- Spin relaxation in magnetic resonance applications

- Energy transfer in photosynthetic complexes and other molecular assemblies

In these processes, the damping parameter γ relates to physical quantities such as transition rates and relaxation timescales, which can be derived from Fermi's golden rule or measured experimentally through techniques like time-resolved spectroscopy.

System-Environment Coupling

Amplitude damping naturally arises from modeling a quantum system coupled to a zero-temperature bath, where the environment can accept energy from the system but cannot donate energy back. This represents scenarios such as:

- A molecule coupled to electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations

- A quantum emitter in a cold environment

- Electronic states interacting with phonon baths at low temperature

The Stinespring dilation theorem provides a powerful representation of amplitude damping through an isometric extension, where the system couples to an environmental ancilla [19]. For amplitude damping, this dilation takes the form:

V|0⟩ = |0,0⟩ V|1⟩ = √(1-γ)|0,1⟩ + √(γ)|1,0⟩

This representation shows that when the system starts in the excited state |1⟩, it has a probability γ of transferring its excitation to the environment, resulting in the system ending in the ground state |0⟩ while the environment becomes excited [19].

Figure 1: System-Environment Interaction in Amplitude Damping

Implications for Quantum Chemistry Simulations

Impact on Quantum Algorithms

The presence of amplitude damping noise significantly affects the performance and reliability of quantum algorithms for chemistry simulations. Recent research has revealed several critical implications:

Generation of Magic: Contrary to most noise types that degrade quantum resources, amplitude damping can actually generate or enhance nonstabilizerness (magic) in certain scenarios, unlike depolarizing noise which universally suppresses magic [20]. This has profound implications for fault-tolerant quantum computation, where magic states are essential resources.

Noise-Induced Barren Plateaus: For variational quantum algorithms (VQAs), amplitude damping can contribute to noise-induced barren plateaus (NIBPs), where cost function gradients become exponentially small as circuit depth increases [5]. However, as a Hilbert-Schmidt (HS)-contractive non-unital map, amplitude damping does not necessarily lead to barren plateaus in all scenarios, suggesting it may be less detrimental to VQA trainability than unital noise in some cases [5].

Algorithm-Specific Effects: Different quantum algorithms exhibit varying resilience to amplitude damping noise. For instance, in hybrid quantum neural networks (HQNNs) for image classification, Quanvolutional Neural Networks (QuanNN) demonstrate greater robustness against amplitude damping compared to other architectures like Quantum Convolutional Neural Networks (QCNN) [21].

Resource Requirements and Limitations

The table below summarizes key resource considerations for quantum chemistry simulations under amplitude damping noise:

Table 2: Resource Considerations for Quantum Chemistry Under Amplitude Damping

| Resource Type | Impact of Amplitude Damping | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Qubit Coherence | Reduces effective coherence time; limits circuit depth | Error mitigation; dynamical decoupling |

| Circuit Fidelity | Exponential decay with circuit depth and γ | Error correction; purification schemes |

| Magic State Resources | Can be generated or enhanced in certain cases | Leverage noise for resource generation |

| Algorithm Trainability | May contribute to noise-induced barren plateaus | Noise-aware optimization; error mitigation |

Mitigation Strategies for Amplitude Damping

Quantum Purification Techniques

Recent advances in quantum error mitigation have led to specialized purification techniques specifically designed for amplitude damping noise. These approaches can substantially enhance the fidelity of affected states or channels while maintaining low resource overhead [18].

The purification method for AD noise employs a circuit-based approach that requires only one or two ancilla qubits in combination with two Clifford gates (Hadamard and controlled-Z gates) [18]. Unlike previous purification methods that required multiple copies of states, this circuit operates on a single noisy state, reducing circuit dimension and thereby decreasing the likelihood of additional noise, while circumventing limitations imposed by the no-cloning theorem [18].

The purification process works by detecting and effectively filtering out noise-induced errors through post-selection based on ancilla measurement outcomes. When successful, this approach produces an actual purified quantum state that can be directly reused in subsequent computational tasks, achieving higher fidelity with respect to the original state [18].

Figure 2: Quantum Purification Circuit for Amplitude Damping

Error Correction and Hardware Solutions

Beyond purification, several other strategies exist for mitigating amplitude damping in quantum chemistry simulations:

Density Matrix Simulations: Using density matrix simulators like Amazon Braket's DM1 allows researchers to model amplitude damping noise explicitly in their simulations, providing more accurate predictions of algorithm performance on real hardware [22]. These simulators support up to 17 qubits and include predefined amplitude damping channels, eliminating the need to manually define Kraus operators [22].

Domain-Specific Software Platforms: Tools like Kvantify Qrunch provide chemistry-specific approaches that improve hardware utilization for molecular simulations, enabling efficient execution across entire processor architectures despite noise limitations [23]. These platforms have demonstrated 3-4× improvement in problem-size capacity compared to standard approaches [23].

Algorithm Selection and Design: Choosing algorithms with inherent robustness to amplitude damping, such as Quanvolutional Neural Networks, can significantly improve results in noisy environments [21]. Additionally, designing custom circuits that account for the specific characteristics of AD noise can enhance performance.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Simulation-Based Noise Characterization

For researchers investigating amplitude damping effects in molecular systems, the following protocol provides a methodology for systematic noise characterization:

Circuit Preparation: Implement the quantum algorithm of interest using a framework that supports noise simulation, such as Amazon Braket, Qiskit, or BlueQubit [24] [22].

Noise Introduction: Incorporate amplitude damping channels after each gate operation or at specified intervals, using the Kraus operator representation with carefully selected γ parameters based on target hardware characteristics or theoretical models.

Density Matrix Simulation: Execute the circuit using a density matrix simulator (e.g., DM1) to track the complete evolution of the quantum state under amplitude damping noise [22].

Measurement and Analysis: Perform measurements on the output state and compare results with noiseless simulations to quantify the impact of amplitude damping on algorithm performance.

Mitigation Application: Implement appropriate error mitigation strategies (purification, error correction, etc.) and reevaluate performance.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines essential computational tools and their functions for studying amplitude damping in molecular systems:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Amplitude Damping Studies

| Tool/Platform | Type | Key Function | Applicability to AD Noise |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amazon Braket DM1 | Density matrix simulator | Simulates noisy quantum evolution with predefined channels | Direct support for amplitude damping channel |

| Kvantify Qrunch | Domain-specific quantum platform | Chemistry workflows with improved hardware utilization | Mitigates effects of noise including amplitude damping |

| BlueQubit Simulator | High-performance simulator | Large-scale quantum circuit simulation | Benchmarks algorithm performance under noise |

| NVIDIA cuQuantum | SDK | Accelerated quantum circuit simulation | Enables efficient noise simulation including AD |

Amplitude damping noise represents a fundamental challenge for quantum simulations of molecular systems, directly modeling the energy relaxation processes that occur in real physical systems. Its non-unital character leads to unique effects on quantum algorithms, differing significantly from more commonly studied unital noise channels like depolarizing noise.

The specialized nature of amplitude damping necessitates tailored mitigation approaches, such as the recently developed purification techniques that offer substantial fidelity improvements with minimal resource overhead [18]. Furthermore, the unexpected ability of amplitude damping to generate magic in certain contexts suggests potential opportunities for leveraging, rather than merely mitigating, this noise source [20].

As quantum hardware continues to advance, developing more sophisticated noise models that accurately capture composite noise effects—including combinations of amplitude damping with other decoherence processes—will be essential for realizing the potential of quantum computing in molecular design and drug development. The integration of application-specific error mitigation strategies, such as those implemented in platforms like Kvantify Qrunch, points toward a future where quantum simulations can provide valuable insights for chemical and pharmaceutical research despite the persistent challenge of noise in NISQ-era devices.

This technical guide provides a comparative analysis of how depolarizing and amplitude damping noise models distinctly impact the accuracy of quantum simulations in chemistry. Framed within broader research on quantum noise for chemical simulations, this whitepaper synthesizes recent findings to demonstrate that, contrary to traditional error correction paradigms, amplitude damping noise can be harnessed to enhance performance in specific quantum machine learning (QML) tasks, whereas depolarizing noise is uniformly detrimental. Targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this document presents structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and essential toolkits to guide the design of noise-resilient quantum computational chemistry experiments.

The simulation of molecular systems is a cornerstone of chemical research with profound implications for drug discovery and materials science. While quantum computers hold the potential to exponentially speed up these simulations by naturally mimicking quantum phenomena, current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices are plagued by decoherence and operational errors [13] [7]. These imperfections, or noise, can drastically alter computational outcomes. Notably, not all noise is created equal. The physical nature of a noise model—specifically, whether it is unital (preserving the identity operator, like depolarizing noise) or non-unital (like amplitude damping)—fundamentally dictates its impact on the fidelity of chemical property predictions [13] [25]. Understanding these differences is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical step toward developing effective error mitigation strategies and leveraging noise as a potential resource for quantum advantage in chemistry.

Theoretical Foundations of Noise Models

In quantum computing, noise processes are formally described by quantum channels, which are mathematical representations of the evolution of an open quantum system. These are often expressed using the operator-sum representation: (\mathcal{E}(\rho) = \sum{k} Ek \rho Ek^{\dagger}), where ({Ek}) are Kraus operators satisfying the completeness condition (\sumk Ek^\dagger E_k = I) [26]. The distinct characteristics of depolarizing and amplitude damping channels are rooted in their unique Kraus operators.

Depolarizing Noise Channel

The depolarizing channel is a unital channel, meaning it preserves the maximally mixed state (I/d). It models a scenario where the quantum state is replaced with a completely random state with probability (p). For a single qubit, it is defined as [13] [26]: [ \mathcal{E}{D}(\rho) = (1 - p) \rho + \frac{p}{3} (X \rho X + Y \rho Y + Z \rho Z) ] Its Kraus operators are (E0 = \sqrt{1-p} I), (E1 = \sqrt{p/3} X), (E2 = \sqrt{p/3} Y), and (E_3 = \sqrt{p/3} Z). This channel symmetrically applies Pauli errors, effectively scrambling quantum information without any preferred direction.

Amplitude Damping Noise Channel

The amplitude damping channel is a non-unital channel that models the dissipation of energy from a quantum system to its environment, analogous to spontaneous emission. For a single qubit, it describes the decay from the excited state (|1\rangle) to the ground state (|0\rangle) [13] [26]. Its Kraus operators are: [ E0 = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & \sqrt{1 - \gamma} \end{bmatrix}, \quad E1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & \sqrt{\gamma} \ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} ] The corresponding quantum channel is: [ \mathcal{E}{AD}(\rho) = E0 \rho E0^\dagger + E1 \rho E_1^\dagger ] This channel is not symmetric and provides a physical model for energy loss at a finite temperature.

Comparative Mechanisms of Action

The fundamental difference between these channels lies in their symmetry and physical interpretation. Depolarizing noise acts as a symmetric randomizer, uniformly degrading all information in the system. In contrast, amplitude damping noise introduces an asymmetric, structured decay toward the ground state [13]. This structural difference is the origin of their divergent impacts on chemical accuracy, as the latter can sometimes mimic or even enhance certain learning processes in quantum machine learning algorithms [13] [25].

Experimental Protocols for Noise Impact Analysis

To quantitatively assess the impact of these noise models, researchers can employ the following detailed methodology, which is adapted from benchmark studies in quantum reservoir computing (QRC) and quantum machine learning [13] [27].

Quantum Machine Learning Task Definition

- Objective: Predict the first excited electronic energy ((E1)) of the Lithium Hydride (LiH) molecule from its ground state ((|\psi0\rangle)).

- Significance: Quantum chemistry problems, particularly energy calculation, are a fundamental benchmark for QML due to their direct industrial relevance and the exponential scaling of their classical computational cost [13] [28].

- Algorithm: Quantum Reservoir Computing (QRC). A random quantum circuit (the reservoir) processes the input ground state. The resulting quantum state is measured, and these classical measurement outcomes are fed into a simple machine learning model (e.g., linear regression) for the final prediction of (E_1) [13].

- Reservoir Construction: Implement a family of pseudo-random quantum circuits with a variable number of gates (ranging from 10 to 200 in benchmark studies) [13].

- Noise Injection: After the application of each quantum gate in the reservoir, apply a noise channel.

- For depolarizing noise, each gate is followed by (\mathcal{E}{D}(\rho)) with a chosen error probability (p).

- For amplitude damping noise, each gate is followed by (\mathcal{E}{AD}(\rho)) with a damping parameter (\gamma).

- State Evolution: The system's evolution under noise is simulated using a density matrix representation to fully capture mixed-state dynamics [27] [26].

- Metric Calculation: For each noisy circuit, compute the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the predicted (E_1) and its true value. Concurrently, track the quantum state fidelity between the final noisy state (\rho) and the ideal noiseless state (|\psi\rangle) [13].

Data Analysis and Comparison

- Performance Benchmarking: Plot the MSE against the number of gates for different error probabilities ((p) or (\gamma)) for both noise models.

- Threshold Identification: Determine the regime (number of gates and error probability) where the performance of the noisy reservoir equals or surpasses that of the noiseless reservoir. Studies indicate that for amplitude damping, this occurs when the state fidelity remains above approximately 0.96 [13].

Quantitative Results and Comparative Analysis

Empirical data from rigorous benchmarking reveals a stark contrast in how these noise models affect chemical prediction accuracy.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Noise Models on LiH Energy Prediction Task [13]

| Noise Model | Impact on Chemical Accuracy (MSE) | Key Characteristic | Performance Relative to Noiseless |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depolarizing | Significant degradation; MSE increases steadily with gate count and error probability. | Unital (symmetric scrambling) | Always worse, even for small error probabilities. |

| Amplitude Damping | Can be beneficial; MSE lower than noiseless for circuits with < ~135 gates at p=0.0005. | Non-unital (energy dissipation) | Can be superior in low-gate, low-error regimes. |

| Phase Damping | Performance degradation, but less severe than depolarizing noise. | Unital (dephasing without energy loss) | Always worse, but fidelity decreases slower than depolarizing. |

Table 2: Fidelity Thresholds for Beneficial Amplitude Damping Noise [13]

| Error Probability (p) | Maximum Beneficial Gate Count | Average Fidelity (vs. Noiseless) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0001 | Always beneficial or equal in tested range | > 0.99 |

| 0.0005 | ~135 gates | > 0.96 |

| 0.001 | ~60 gates | ~0.96 |

The data shows that the performance of circuits subjected to depolarizing and phase damping noise monotonically decreases as the number of gates increases. In contrast, for amplitude damping noise, there exists a clear crossover point where the noisy reservoir outperforms the noiseless one. This advantage is confined to a regime of shallow to moderate circuit depths (exemplified by the ~135 gate threshold for (p=0.0005)) and high state fidelity (above 0.96) [13]. This regime is highly relevant for NISQ algorithms, which often rely on shallow circuits [13] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

To implement the described experimental protocols, researchers require a suite of software and hardware tools capable of emulating quantum systems with high accuracy and configurability.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Quantum Noise Simulation in Chemistry

| Tool Name / Category | Function / Purpose | Key Features for Noise Research |

|---|---|---|

| Qiskit AerSimulator [27] | Quantum circuit emulator with configurable noise models. | Allows injection of depolarizing, amplitude/phase damping, and custom noise models; can be calibrated with backend parameters from real IBM processors. |

| Eviden Qaptiva [27] | High-performance quantum emulator. | Supports deterministic (density matrix) and stochastic (state vector) noise simulation; suitable for detailed analysis of small-to-medium circuits. |

| Paddle Quantum [26] | Quantum machine learning framework. | Built-in functions for common noise channels (bit-flip, phase-flip, amplitude damping, depolarizing); integrates with machine learning pipelines. |

| Chemical Benchmark (e.g., LiH) [13] [28] | A standardized problem for validating quantum simulations. | Provides a ground-truth reference for assessing algorithmic and noise-induced errors in a chemically relevant context. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [28] | Classical computational method for generating training data. | Used to compute accurate ground-state energies for small molecules, which can serve as training data for QML models. |

| Kopsinine | Kopsinine, CAS:559-51-3, MF:C21H26N2O2, MW:338.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| KPT-6566 | RORγ Inverse Agonist|2-[[4-[[[4-(tert-Butyl)phenyl]sulfonyl]imino]-1-oxo-1,4-dihydro-2-naphthyl]thio]acetic Acid | 2-[[4-[[[4-(tert-Butyl)phenyl]sulfonyl]imino]-1-oxo-1,4-dihydro-2-naphthyl]thio]acetic Acid is a potent RORγ inverse agonist for autoimmune disease research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Implications for Quantum Error Correction and Mitigation

The divergent impacts of depolarizing and amplitude damping noise lead to a critical strategic implication: not all noise requires the same level of mitigation priority. The finding that amplitude damping can be beneficial in specific QML contexts suggests that a nuanced approach to quantum error correction (QEC) is necessary [13] [29].

- Depolarizing and Phase Damping Noise: These should be high-priority targets for correction and mitigation. Since they offer no observable benefit and consistently degrade performance, applying techniques like Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) and Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC) is crucial for maintaining accuracy [13] [30].

- Amplitude Damping Noise: In the regime where it improves performance, aggressively correcting it could be counterproductive. Instead, researchers might focus on leveraging its structure or developing QEC codes that protect against other error types while preserving the potentially useful aspects of amplitude damping [29]. Recent theoretical work on covariant quantum error-correcting codes aims to achieve exactly this: protecting entangled sensors from noise while preserving their sensitivity for metrology and sensing tasks, a concept transferable to quantum simulation [29].

This analysis demonstrates that the impact of quantum noise on chemical accuracy is not monolithic. While depolarizing noise acts as a uniform disruptor that should be prioritized for mitigation, amplitude damping noise presents a more complex profile, with the capacity to enhance performance in specific, shallow-circuit QML applications. For researchers and professionals in drug development and materials science, these findings underscore the importance of noise-aware algorithm design. The future of practical quantum computational chemistry lies not only in suppressing all noise but also in understanding its physical mechanisms to strategically correct its worst effects while potentially co-opting its more structured forms.

The Critical Role of T1 and T2 Times in Chemical Simulation Fidelity

The accurate simulation of chemical systems, such as the calculation of molecular ground-state energies, represents a promising application for near-term quantum computers [31]. However, the practical execution of these algorithms on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices is severely constrained by various sources of quantum noise, which disrupt the delicate quantum states necessary for computation [31] [22]. These disruptions cause the quantum information to fade away, a phenomenon known as decoherence, ultimately randomizing or erasing the information within the quantum system [22]. The fight against decoherence is central to quantum computational chemistry, as these errors directly compromise the accuracy of calculated molecular properties like energies and reaction pathways [31].

Among the most critical parameters characterizing decoherence are the T1 and T2 times of a qubit. These timescales dictate how long a quantum state remains viable for computation and are fundamental components of the noise models that determine the fidelity of chemical simulations. This guide explores the role of T1 and T2 within the broader context of quantum noise models, focusing on their distinct effects in depolarizing and amplitude damping channels, and their profound impact on the performance of chemical simulations such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE).

Theoretical Foundations of T1 and T2 Relaxation

Defining T1 and T2 Times

Qubits, the fundamental units of quantum information, are inherently fragile and interact uncontrollably with their environment. This interaction leads to decoherence, which is primarily described by two characteristic times:

- T1 Time (Energy Relaxation Time): This is the timescale for a qubit to spontaneously decay from its excited state (|1⟩) to its ground state (|0⟩). It represents the loss of energy to the environment, analogous to energy dissipation in classical systems. The amplitude damping channel is the quantum noise model that mathematically describes this energy loss process [22].

- T2 Time (Phase Relaxation Time): Also known as the dephasing time, T2 quantifies the timescale over which the phase coherence of a quantum superposition is lost. A qubit in a superposition state (α|0⟩ + β|1⟩) will experience a random shifting of the relative phase between |0⟩ and |1⟩, effectively destroying the quantum interference effects that are crucial for quantum computation. Pure dephasing is modeled by the dephasing noise channel.

A key relationship between these parameters is that the total transverse relaxation time T2 is always less than or equal to twice the longitudinal relaxation time T1 (T2 ≤ 2*T1), a constraint arising from the underlying physics of the noise processes.

Mathematical Representation via Quantum Channels

The evolution of a quantum state under noise is not described by unitary gates but by more general operations known as quantum channels. These are completely positive, trace-preserving maps that act on density matrices (Ï), which can represent both pure and mixed quantum states [22].

The Kraus operator formalism provides a mathematical framework to describe these channels. A quantum channel ð’© acts on a density matrix as ð’©(Ï) = ∑ᵢ Káµ¢ Ï Kᵢ†, where the Káµ¢ are Kraus operators satisfying ∑ᵢ Kᵢ†Káµ¢ = I [22].

Amplitude Damping Channel (T1): This channel models energy relaxation. Its Kraus operators are:

- K₀ = [1 0; 0 √(1-γ)] and K₠= [0 √γ; 0 0] where γ = 1 - e^(-t/T1) is the probability of decay after time t. This channel is nonunital, meaning it has a bias that pushes qubits toward a specific state (the ground state |0⟩) [32]. This directional bias distinguishes it from other noise types and, as recent research suggests, can potentially be harnessed as a computational resource [32].

Dephasing Channel (T2-related): This channel models the loss of phase coherence without energy loss. Its Kraus operators are:

- K₀ = √(1-p) I and K₠= √p Z where p is the probability of a phase flip and Z is the Pauli-Z matrix. The relationship between p and T2 is given by p = (1 - e^(-t/T2))/2.

Depolarizing Channel: This is a unital noise model that represents a worst-case scenario where the qubit is replaced by a completely mixed state with probability p. Its Kraus operators are proportional to the Pauli matrices I, X, Y, Z. Unlike amplitude damping, it scrambles the qubit state evenly without any directional bias [32]. It is often used as a simple model to assess the worst-case impact of noise.

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of these primary noise models:

Table 1: Key Quantum Noise Models and Their Characteristics

| Noise Model | Type | Physical Process | Key Kraus Operators | Effect on Qubit State | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude Damping | Nonunital [32] | Energy Relaxation (T1) | K₀, K₠(see above) | Population decay to | 0⟩ |

| Dephasing | Unital | Phase Decay (T2) | K₀ ∠I, K₠∠Z | Loss of phase coherence | |

| Depolarizing | Unital [32] | State Scrambling | Kᵢ ∠I, X, Y, Z | Complete randomization |

Impact on Chemical Simulation Algorithms

Vulnerability of Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE)

The VQE algorithm is a leading candidate for finding molecular ground-state energies on NISQ devices [31]. It uses a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) to prepare a trial state, whose energy is measured and then minimized via a classical optimizer. The algorithm's performance is highly sensitive to noise, which corrupts the prepared quantum state.

Research on simulating VQE for molecules like sodium hydride (NaH) has shown that noise significantly impacts both the estimated energy and the fidelity of the prepared state compared to the true ground state [31]. The choice of ansatz circuit, derived for instance from Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) theory, is critical, as deeper and more expressive circuits are more susceptible to decoherence [31].

Comparative Impact of Different Noise Types

The distinct natures of T1- and T2-driven noise lead to different impacts on computational outcomes:

- Amplitude Damping (T1): This noise introduces a systematic bias toward the ground state. In some contexts, this structured, nonunital nature allows for partial adaptation by learning algorithms [30]. Furthermore, its directional bias has been theorized to enable "RESET" protocols that can recycle noisy ancilla qubits, potentially extending computation depth without mid-circuit measurements [32].

- Dephasing (T2): This noise directly attacks quantum superpositions, which are the bedrock of quantum advantage. It rapidly destroys interference effects needed for accurate quantum phase estimation and state preparation in chemical models.

- Depolarizing Noise: As a unital noise, depolarizing noise introduces significant randomness and is often found to cause severe performance degradation in algorithms like Quantum Reinforcement Learning (QRL) [30]. It represents a worst-case scenario that quickly randomizes the quantum state.

Table 2: Comparative Impact of Noise Models on Algorithm Performance

| Algorithm | Impact of Amplitude Damping (T1) | Impact of Dephasing (T2) | Impact of Depolarizing Noise |

|---|---|---|---|

| VQE | Systematic bias in energy estimation; state fidelity loss. | Destruction of phase-critical superpositions; inaccurate energy. | Severe energy inaccuracies; high state infidelity [31]. |

| Quantum Reinforcement Learning (QRL) | Allows for partial adaptation; less severe degradation [30]. | Disrupts learning dynamics and policy convergence. | Significant performance degradation; introduces high randomness [30]. |

| Generic Quantum Circuits | Can be harnessed for reset in specific protocols [32]. | Limits the coherent depth of computation. | Renders circuits classically simulatable beyond a certain depth [33]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between noise sources, their physical effects on a qubit, and the subsequent impact on a chemical simulation's output.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Noise Effects

To robustly benchmark the performance of quantum chemistry algorithms under realistic noise conditions, researchers employ systematic simulation-based methodologies. The workflow below outlines a standard protocol for evaluating the impact of T1, T2, and other noise models on chemical simulation fidelity.

Workflow for Noisy Simulation of Chemical Problems

Detailed Methodology

A comprehensive experiment, as conducted in studies of noisy quantum circuits for computational chemistry, involves several critical stages [31] [30]:

Problem Encoding:

- The molecular Hamiltonian (H(R)) for a target molecule, such as sodium hydride (NaH), is derived under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation [31].

- This fermionic Hamiltonian is transformed into a qubit representation using a mapping like the Jordan-Wigner transformation, resulting in a Hamiltonian expressed as a sum of Pauli strings: H(R) = Σⱼ cⱼ(R) Pⱼ [31].

Ansatz Preparation:

- A parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) is selected to prepare the trial wavefunction. Common choices for chemical problems are derived from Unitary Coupled Cluster theory, such as UCCSD (Unitary Coupled Cluster with Singles and Doubles) [31].

Noise Model Configuration:

- A quantum simulator capable of emulating NISQ device behavior is configured. This involves defining a custom noise model or using a predefined one.

- Key parameters to set include:

- T1 and T2 times for each qubit, which define the amplitude damping and dephasing channels.

- Gate error probabilities (e.g., for single- and two-qubit gates).

- Measurement error probabilities.

- These parameters can be extracted from hardware calibration data (e.g.,

rigettidevice properties) or set to desired values for a controlled study [22].

Execution and Optimization:

- The VQE algorithm is run iteratively. In each iteration, the quantum circuit is executed on the noisy simulator (with a sufficient number of "shots" or repetitions), and the classical optimizer (e.g., COBYLA or BFGS) adjusts the parameters to minimize the expected energy [31].

Error Mitigation Application:

- Error mitigation techniques are applied to the noisy results to improve accuracy. As explored in noise-resilient quantum learning, these can include [30]:

- Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE): Running the circuit at different noise levels and extrapolating back to the zero-noise limit.

- Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC): Using a linear combination of circuit executions to cancel out the effect of known noise channels.

- Adaptive Policy-Guided Error Mitigation (APGEM): Using reward trends from the learning algorithm to adaptively stabilize the training process against noise fluctuations [30].

- Error mitigation techniques are applied to the noisy results to improve accuracy. As explored in noise-resilient quantum learning, these can include [30]:

Table 3: Key Research Tools and Platforms for Noise Simulation Studies

| Tool / Resource | Function | Example in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Density Matrix Simulator | Simulates open quantum systems and general noise channels, representing the state as a density matrix [22]. | Amazon Braket's DM1 simulator is used to simulate predefined noise channels without manually defining Kraus operators [22]. |

| Noise Model Libraries | Predefined implementations of common noise channels (depolarizing, amplitude damping, dephasing). | Qiskit's AerSimulator allows fine-grained control over noise models to emulate NISQ devices [30]. |

| Error Mitigation Frameworks | Software packages implementing ZNE, PEC, and other mitigation techniques. | Hybrid APGEM–ZNE–PEC framework used to boost robustness of Quantum Reinforcement Learning [30]. |

| Classical Optimizers | Algorithms for tuning variational circuit parameters (e.g., COBYLA, BFGS). | Used in VQE to minimize the energy expectation value, with performance affected by noise [31]. |

| Hardware Calibration Data | Experimentally measured qubit properties (T1, T2, gate fidelities). | Informs realistic noise model parameters for simulation; can be sourced from quantum processors like Rigetti's Aspen-M-2 [22]. |

The exploration of noise in quantum chemical simulations is rapidly evolving beyond simple mitigation. A paradigm shift is underway, moving from viewing noise as a purely detrimental force to understanding its nuanced role and potentially leveraging its structure. Key future directions include:

- Harnessing Nonunital Noise: Recent theoretical work from IBM challenges the classical view by demonstrating that nonunital noise, such as amplitude damping, can be actively used to extend computation depth via "RESET" protocols that recycle noisy ancilla qubits [32]. This turns a bug into a potential feature.

- Advanced Error Mitigation: Hybrid frameworks that combine multiple techniques—such as Adaptive Policy-Guided Error Mitigation (APGEM), Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE), and Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC)—are showing promise in providing significant resilience across diverse noise models [30].

- Resource-Efficient Simulations: The use of multi-fidelity modeling, which balances computational cost and accuracy by combining simulations of varying quality, is a powerful strategy for optimizing the design of quantum systems, including reactors, and could be adapted for optimizing quantum algorithm parameters under noise [34].

In conclusion, T1 and T2 times are not just hardware metrics; they are fundamental parameters that define the accuracy and feasibility of quantum computational chemistry. Amplitude damping (T1) and dephasing (T2) have distinct and profound impacts on the fidelity of chemical simulations like VQE. While these noise processes currently pose a significant barrier to practical quantum advantage in chemistry, a deeper understanding of their effects—coupled with advanced error mitigation and the potential to harness specific noise properties—is paving the way for more robust and ultimately successful applications of quantum computing to the simulation of matter.

In the pursuit of quantum advantage for computational chemistry, managing quantum noise is a fundamental challenge. Quantum processing units (QPUs) are susceptible to various noise channels that distort calculations, particularly impacting the precise simulation of molecular systems and the prediction of spectroscopic properties [35]. Unlike classical errors, quantum errors include uniquely quantum phenomena like phase flips and amplitude damping, which have no classical analog and can destroy the quantum coherence essential for chemical computations [36]. In the context of chemistry simulations, such as calculating molecular energies or absorption spectra, these errors can lead to inaccurate predictions of reaction pathways, binding energies, and electronic properties. Current-generation noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices operate without full error correction, making the understanding and mitigation of inherent noise channels like phase damping, bit flip, and measurement errors a critical area of research for quantum computational chemistry [22].

Core Noise Channels: Theory and Impact

Mathematical Foundations of Noise Channels

In quantum computing, the evolution of a quantum state is typically described by unitary operations. However, when a quantum system interacts with its environment, this evolution is no longer unitary and must be described using the density matrix formalism and quantum channels [22]. A general quantum channel ( \mathcal{N} ) acting on a density matrix ( \rho ) is mathematically represented by the Kraus decomposition: [ \mathcal{N}(\rho) = \sumi si Ki \rho Ki^\dagger ] where the ( Ki ) are Kraus operators satisfying ( \sumi Ki^\dagger Ki = I ), and ( si ) represents the probability associated with the application of operator ( Ki ) [22]. This formalism provides a comprehensive framework for modeling various types of noise affecting qubits.

Characterization of Key Noise Channels

The following table summarizes the fundamental noise channels relevant to chemical simulations, their Kraus operator representations, and their primary effects on qubit states.

Table 1: Characterization of Key Noise Channels in Quantum Chemical Simulations

| Noise Channel | Kraus Operators | Mathematical Description | Physical Effect on Qubits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bit Flip [37] [22] | ( K_0 = \sqrt{1-p} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} )K_1 = \sqrt{p} \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} |

( \mathcal{N}(\rho) = (1-p)\rho + p X \rho X ) | Quantum analog of a classical bit error; flips |0⟩ to |1⟩ and vice versa with probability ( p ). |

| Phase Flip [37] | ( K_0 = \sqrt{1-p} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} )K_1 = \sqrt{p} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{bmatrix} |

( \mathcal{N}(\rho) = (1-p)\rho + p Z \rho Z ) | Alters the relative phase without changing energy probabilities; transforms |+⟩ to |-⟩. |

| Phase Damping [37] | ( K_0 = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & \sqrt{1-\gamma} \end{bmatrix} )K_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \sqrt{\gamma} \end{bmatrix} |

Coherent information is lost without energy loss. | Represents a uniquely quantum phenomenon where information is lost without energy loss. |

| Amplitude Damping [37] [20] | ( K_0 = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & \sqrt{1-\gamma} \end{bmatrix} )K_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & \sqrt{\gamma} \\ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} |

Models energy dissipation to the environment. | Qubit loses energy to its environment, causing relaxation from |1⟩ to |0⟩. Characterized by relaxation time Tâ‚. |

| Depolarizing [37] | ( K0 = \sqrt{1-p} I ), ( K1 = \sqrt{p/3} X ),( K2 = \sqrt{p/3} Y ), ( K3 = \sqrt{p/3} Z ) | ( \mathcal{N}(\rho) = (1-p)\rho + \frac{p}{3}(X\rho X + Y\rho Y + Z\rho Z) ) | With probability ( p ), the qubit is replaced by a completely mixed state; otherwise, it is left untouched. |

Impact of Noise on Chemical Computations

In chemical simulations, even small error rates can significantly alter computed molecular properties. For instance, in the variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) algorithm used for ground-state energy calculations, phase damping and bit-flip errors can prevent the algorithm from converging to the correct energy landscape [35]. Quantum linear response (qLR) theory, used for calculating spectroscopic properties, is particularly sensitive to noise in the quantum circuit components that construct the Hessian and metric matrices [35]. Research has demonstrated that coherent noise, such as that from imperfect gate calibration, can be particularly detrimental as it can accumulate systematically throughout a circuit, leading to large errors in the final molecular property predictions [35]. Furthermore, unlike depolarizing noise which universally suppresses nonstabilizerness (or "magic"), amplitude damping—a nonunital channel—can paradoxically generate or enhance this quantum resource under certain conditions, which may have implications for the design of noise-resilient quantum algorithms for chemistry [20].

Experimental Protocols for Noise Characterization

Protocol 1: Characterizing Bit Flip and Phase Flip Errors

Objective: To quantitatively measure the bit flip and phase flip error rates on a target qubit used in a molecular simulation.

Materials & Setup:

- Quantum processor or density matrix simulator (e.g., Amazon Braket DM1) [22]

- Single qubit initialized in the |0⟩ state

- Single-qubit gates: Hadamard (H), Pauli-X

Procedure:

- Bit Flip Characterization:

- Initialize the qubit in |0⟩.

- Apply an X-gate to flip the qubit to |1⟩.

- Let the qubit idle for a time ( t ) or apply a sequence of gates to simulate circuit depth.

- Measure the qubit in the computational basis.

- Repeat for ( N ) shots (e.g., 1000) and record the probability of measuring |0⟩, which represents the bit flip error rate ( p_{\text{bit}} ) [37].

- Phase Flip Characterization:

- Initialize the qubit in |0⟩.

- Apply an H-gate to create the |+⟩ = (|0⟩ + |1⟩)/√2 state.

- Let the qubit idle for time ( t ) or apply a sequence of gates.

- Apply another H-gate to convert phase flips into bit flips.

- Measure the qubit in the computational basis.

- Repeat for ( N ) shots and record the probability of measuring |1⟩, which represents the phase flip error rate ( p_{\text{phase}} ) [37].

Data Analysis: The error rates are calculated directly from the measurement statistics. For the bit flip experiment, ( p{\text{bit}} = N0 / N ), where ( N0 ) is the count of |0⟩ measurements after the X-gate. For the phase flip experiment, ( p{\text{phase}} = N1 / N ), where ( N1 ) is the count of |1⟩ measurements.

Protocol 2: Noise Propagation in an Entangled Chemical State

Objective: To evaluate how noise channels corrupt a maximally entangled Bell pair, a state often encountered in quantum chemistry algorithms for active space simulations.

Materials & Setup:

- Two-qubit quantum processor or density matrix simulator

- Two qubits initialized in |00⟩

- Single-qubit Hadamard gate and two-qubit CNOT gate

Procedure:

- Prepare a Bell state:

- Apply H-gate to qubit 0.

- Apply CNOT gate with qubit 0 as control and qubit 1 as target. The ideal state is (|00⟩ + |11⟩)/√2.

- Apply a custom noise model (e.g., asymmetric depolarizing, amplitude damping) to one or both qubits [37] [22].

- Measure both qubits in the computational basis.

- Repeat for ( N ) shots (e.g., 1000) to collect measurement statistics.

Data Analysis: In a noiseless scenario, measurements yield only |00⟩ and |11⟩. The presence of |01⟩ and |10⟩ outcomes indicates bit flip errors. A reduction in the correlation between the two qubits, quantified by the fidelity between the experimental and ideal Bell state density matrix, provides a comprehensive measure of the total noise impact [22].

Figure 1: Workflow for characterizing noise propagation in an entangled state.

For experimentalists and computational scientists working at the intersection of quantum computing and chemistry, the following tools are essential for conducting noise-aware research.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Noise Research in Quantum Chemistry

| Tool Name | Type/Platform | Primary Function in Noise Research |

|---|---|---|

| Amazon Braket DM1 [22] | Cloud-based density matrix simulator | Simulates mixed states and predefined noise channels; crucial for modeling decoherence. |

| Cirq [37] | Python-based SDK | Provides built-in noise channels (BitFlip, PhaseDamp) for building and testing custom noise models. |

| tUCCSD Ansatz [35] | Quantum Algorithm | A parameterized wavefunction ansatz used in VQE; its depth and structure are sensitive to noise. |

| Quantum Linear Response (qLR) [35] | Quantum Algorithm | Framework for excited states and spectra; used to benchmark how noise degrades predictive accuracy. |

| Root Space Decomposition [38] | Mathematical Framework | Aids in classifying noise propagation through quantum systems to inform error correction strategies. |

Mitigation Strategies and Error-Resilient Algorithms

Mitigating the impact of noise is essential for extracting meaningful results from NISQ-era quantum chemistry simulations. A multi-layered approach is typically required.

Table 3: Error Mitigation Techniques for Chemical Simulations on NISQ Devices

| Mitigation Strategy | Description | Use Case in Chemical Simulations |

|---|---|---|

| Error Mitigation | ||

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) [36] | Runs the same circuit at increased noise levels (e.g., by stretching gates) and extrapolates back to the zero-noise result. | Extracting a more accurate ground-state energy from a noisy VQE calculation. |

| Probabilistic Error Cancellation [36] | Uses a known noise model to invert the effect of errors during classical post-processing of results. | Correcting systematic errors in measurement of expectation values for molecular properties. |

| Dynamical Decoupling [36] | Applies rapid sequences of pulses to idle qubits to average out slow noise from the environment. | Protecting encoded quantum information in a molecular wavefunction during periods of idle circuit time. |

| Error Correction | ||

| Surface Codes [36] [39] | A topological QEC code where qubits are arranged in a 2D lattice; only requires local stabilizer measurements. | The leading candidate for protecting logical qubits encoding molecular orbital information in future fault-tolerant QPUs. |