Navigating Quantum Resource Tradeoffs for Noise-Resilient Chemical Simulations in Drug Discovery

This article explores the critical tradeoffs between computational resources, accuracy, and noise resilience in quantum simulations for chemical systems.

Navigating Quantum Resource Tradeoffs for Noise-Resilient Chemical Simulations in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the critical tradeoffs between computational resources, accuracy, and noise resilience in quantum simulations for chemical systems. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive analysis of foundational principles, advanced methodological approaches, and optimization strategies for near-term quantum hardware. By synthesizing the latest research in error correction, algorithmic innovation, and hardware-efficient encodings, this guide offers a practical framework for selecting and validating quantum computational approaches to accelerate the simulation of complex molecular systems like drug metabolites and catalysts, bridging the gap between theoretical promise and practical application in the NISQ era.

The Quantum Simulation Landscape: Overcoming Classical Limits and NISQ-Era Noise

The simulation of molecular systems represents a computational problem of fundamental importance to drug discovery and materials science. However, the accurate modeling of molecular energetics and dynamics remains intractable for classical computers due to the exponential scaling of the quantum many-body problem. This whitepaper delineates the core algorithmic and physical limitations of classical computational methods when applied to molecular simulation. Furthermore, it explores the emergent paradigm of hybrid quantum-classical algorithms as a pathway toward noise-resilient simulation on near-term quantum hardware, detailing specific experimental protocols and resource requirements that define the current research frontier.

The Quantum Many-Body Problem and Classical Computational Intractability

At the heart of molecular simulation lies the challenge of solving the electronic Schrödinger equation for a system of interacting particles. The complexity of this task scales exponentially with the number of electrons, a phenomenon often termed the curse of dimensionality.

The Exponential Scaling of the State Space

For a molecular system with N electrons, the wavefunction describing the system depends on 3N spatial coordinates. Discretizing each coordinate with just k points results in a state space of dimension k^3N. This exponential growth rapidly outpaces the capacity of any classical computer. For context, a modest molecule with 50 electrons, discretized with a meager 10 points per coordinate, yields a state space of 10^150 dimensions—a number that exceeds the estimated number of atoms in the observable universe. This makes a direct numerical solution of the Schrödinger equation impossible for all but the smallest molecular systems [1].

Limitations of Classical Approximation Methods

Classical computational chemistry relies on a hierarchy of approximation methods to circumvent this intractability, but each introduces significant trade-offs between accuracy and computational cost, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Classical Computational Methods for Molecular Simulation and Their Limitations

| Method | Computational Scaling | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | O(Nâ´) | Neglects electron correlation; inaccurate for reaction barriers and bond dissociation [1]. |

| Coupled Cluster (CCSD(T)) | O(Nâ·) | Considered the "gold standard" but prohibitively expensive for large molecules; fails for strongly correlated systems [1] [2]. |

| Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG) | Polynomial for 1D systems | Accuracy deteriorates with higher-dimensional topological structures or complex entanglement [3]. |

| Fermionic Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) | O(N³) to O(Nâ´) | Susceptible to the fermionic sign problem, leading to exponentially growing variances in simulation outputs [2]. |

The fermionic sign problem is a particularly fundamental obstacle. It causes the statistical uncertainty in Quantum Monte Carlo simulations to grow exponentially with system size and inverse temperature, making precise calculations for many molecules and materials computationally infeasible on classical hardware [2]. Consequently, even with petascale classical supercomputers, the simulation of complex molecular processes, such as enzyme catalysis or the design of novel high-temperature superconductors, remains beyond reach.

The Promise and Challenge of Quantum Simulation

Quantum computers, which use quantum bits (qubits) to simulate quantum systems, are naturally suited to this task. Richard Feynman originally proposed this concept, suggesting that quantum systems are best simulated by other quantum systems [4]. Quantum algorithms can, in principle, simulate quantum mechanics with resource requirements that scale only polynomially with system size.

The Mapping Problem: Fermions to Qubits

A primary challenge in quantum simulation is encoding the molecular Hamiltonian—a fermionic system—into a qubit-based quantum processor. This requires transforming fermionic creation and annihilation operators into Pauli spin operators acting on qubits. Traditional mappings like the Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformations often produce high-weight Pauli terms, which translate into deep, complex quantum circuits that are highly susceptible to noise on current hardware [5].

Recent advances focus on developing more efficient encodings. The Generalized Superfast Encoding (GSE), for instance, optimizes the Hamiltonian's interaction graph to minimize operator weight and introduces stabilizer measurement frameworks. This approach has demonstrated a twofold reduction in root-mean-square error (RMSE) for orbital rotations on real hardware compared to earlier methods, showcasing improved hardware efficiency for molecular simulations [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Techniques

| Mapping Technique | Key Feature | Impact on Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner | Conceptually simple | Introduces long-range interactions, resulting in O(N)-depth circuits [5]. |

| Bravyi-Kitaev | More localized operators | Reduces circuit depth to O(log N) but with more complex transformation rules [5]. |

| Generalized Superfast (GSE) | Optimizes interaction graph | Minimizes Pauli term weight; demonstrated to improve accuracy under realistic noise [5]. |

Noise-Resilient Methodologies for Near-Term Quantum Hardware

Current quantum processors are limited by qubit counts, connectivity, and decoherence. This noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) era necessitates algorithms and methodologies that are inherently resilient to errors.

Advanced Measurement and Error Mitigation Techniques

Achieving high-precision measurements is critical for quantum chemistry, where energy differences are often minuscule (e.g., chemical precision of 1.6 × 10â»Â³ Hartree). Practical techniques have been developed to address key noise sources and resource overheads [6]:

- Locally Biased Random Measurements: This technique reduces shot overhead (the number of times a quantum circuit must be executed) by prioritizing measurement settings that have a larger impact on the energy estimation.

- Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): By characterizing readout errors via QDT, researchers can build an unbiased estimator to mitigate systematic measurement bias. This has been shown to reduce estimation errors by an order of magnitude, from 1-5% to 0.16%, for the BODIPY molecule on an IBM quantum processor [6].

- Blended Scheduling: This method interleaves the execution of different quantum circuits (e.g., for different molecular states) to average out time-dependent noise, ensuring more homogeneous and comparable results.

Noise-Resilient Hybrid Quantum-Classical Algorithms

Hybrid algorithms leverage a quantum computer for specific, computationally demanding sub-tasks while using a classical computer for optimization and control.

- The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE): VQE uses a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) to prepare a trial wavefunction, whose energy is measured on the quantum processor. A classical optimizer then varies the parameters to minimize the energy. While promising, VQE can suffer from barren plateaus (vanishing gradients) and requires extensive measurements for high precision [7] [2].

- Observable Dynamic Mode Decomposition (ODMD): A newer hybrid algorithm, ODMD, extracts eigenenergies from the real-time evolution of a quantum state. It post-processes measurement data using dynamic mode decomposition (DMD), a technique from dynamical systems theory. Theoretical and numerical evidence shows that ODMD converges rapidly and is highly resilient to perturbative noise, making it a leading candidate for near-term ground state energy estimation [3].

- Quantum-Enhanced Monte Carlo: An alternative hybrid approach uses a quantum computer to compute the energy differences in a fermionic quantum Monte Carlo algorithm. This method offloads the most computationally complex step—which is prone to the sign problem on classical machines—to the quantum processor. It has enabled simulations of molecules like molecular nitrogen and solid diamond with up to 120 orbitals using only 16 qubits, achieving accuracy close to the best classical methods but with better noise tolerance [2].

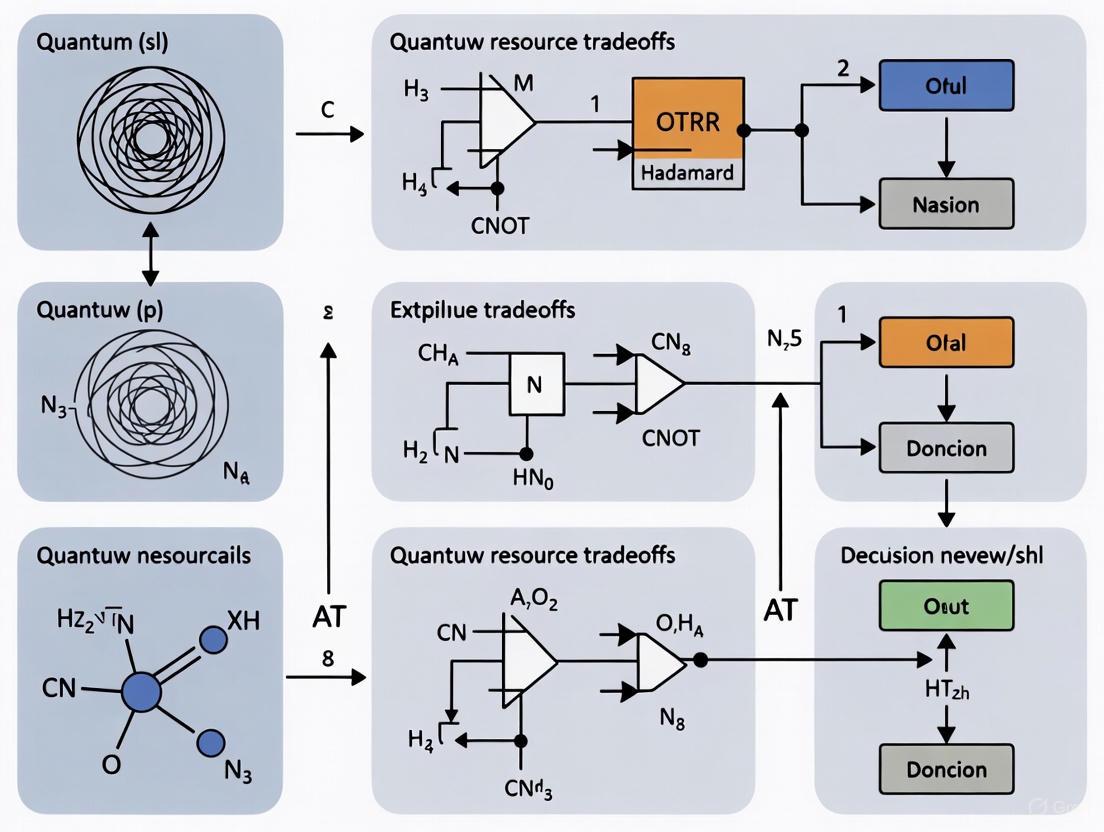

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for a noise-resilient hybrid quantum-classical simulation, integrating the key techniques discussed.

Experimental Protocols and Resource Analysis

This section details a specific experimental protocol from recent research to ground the discussed concepts in a practical implementation.

Case Study: High-Precision Energy Estimation of the BODIPY Molecule

A 2025 study demonstrated a comprehensive workflow for achieving high-precision energy estimation on IBM's noisy quantum hardware, targeting the BODIPY-4 molecule—a complex organic dye [6].

- Objective: To estimate the energy of the Hartree-Fock state for the BODIPY molecule across active spaces ranging from 8 to 28 qubits, aiming for errors close to chemical precision.

- System Preparation: The Hartree-Fock state was chosen as it is a separable state and can be prepared without any two-qubit gates, thereby isolating measurement errors from gate errors.

- Measurement Strategy: The protocol used informationally complete (IC) measurements, allowing for the estimation of multiple observables from the same dataset. This was combined with Hamiltonian-inspired locally biased random measurements to reduce shot overhead.

- Error Mitigation: Parallel Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) was performed concurrently with the main experiment. The calibrated noise model from QDT was then used to construct an unbiased estimator for the molecular energy, directly correcting for readout errors.

- Noise Averaging: A blended scheduling technique was employed, interleaving circuits for different molecular states (Sâ‚€, Sâ‚, Tâ‚) to ensure temporal noise fluctuations affected all estimations uniformly.

- Resource Overhead: The experiment on the 8-qubit system involved sampling S = 70,000 different measurement settings, with each setting repeated for T = 1,000 shots. This high sampling rate was necessary to achieve the reported reduction in absolute error to 0.16%.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key computational and methodological "reagents" essential for conducting state-of-the-art, noise-resilient chemical simulations on quantum hardware.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Noise-Resilient Chemical Simulations

| Research Reagent | Function | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Generalized Superfast Encoding (GSE) | Fermion-to-qubit mapping | Compacts Hamiltonian representation, reduces circuit depth, and improves error resilience [5]. |

| Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements | A foundational measurement strategy | Enables estimation of multiple observables from a single dataset and provides interface for error mitigation [6]. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | Readout error characterization and mitigation | Models device-specific measurement noise to create an unbiased estimator, correcting systematic errors [6]. |

| Locally Biased Random Measurements | Shot-efficient estimation | Prioritizes informative measurements, reducing the number of circuit executions (shots) required for a precise result [6]. |

| Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD) | A classical post-processing algorithm | Extracts eigenenergies from time-series measurement data; proven to be highly noise-resilient [3]. |

| Logical Qubit with Magic State Distillation | A fault-tolerant component | Enables non-Clifford gates for universal quantum computation; recent demonstrations reduced qubit overhead by ~9x [7]. |

| RS-51324 | RS-51324, CAS:62780-15-8, MF:C11H11Cl2N3O2, MW:288.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| NS-2028 | NS-2028, CAS:204326-43-2, MF:C9H5BrN2O3, MW:269.05 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Classical computers are fundamentally limited in their ability to simulate quantum mechanical systems by the exponential scaling of the many-body problem. While approximation methods are useful, they fail for many critical problems in chemistry and materials science. Quantum computing offers a physically natural and potentially scalable path forward. The current research focus has shifted from simply increasing qubit counts to developing a full stack of noise-resilient techniques—including efficient encodings, advanced measurement protocols, and robust hybrid algorithms. The experimental demonstration of end-to-end error-corrected chemistry workflows and the achievement of high-precision measurements on complex molecules underscore that the field is moving beyond theoretical hype. It is building the practical, resource-aware toolkit necessary to make quantum simulation a transformative technology for drug discovery and materials engineering.

The pursuit of practical quantum computing for chemical simulations is fundamentally a battle against noise. In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, the choice of hardware platform directly determines the feasibility and accuracy of simulating molecular systems, a task critical for drug development and materials science. Each hardware type—trapped ions, superconducting qubits, and emerging cat qubits—represents a distinct engineering compromise between qubit stability, gate speed, scalability, and inherent noise resilience. This technical analysis examines the core characteristics, experimental validations, and resource tradeoffs of these platforms within the specific context of enabling high-precision quantum simulations. The convergence of these technologies toward fault tolerance will ultimately determine the timeline for quantum computers to reliably model complex molecular interactions beyond the reach of classical computation.

Hardware Platform Analysis

Core Architectural Principles and Technical Specifications

The fundamental operating principles of each hardware platform dictate its performance characteristics and susceptibility to various noise types.

Trapped Ions utilize individual atoms confined in vacuum by electromagnetic fields. Qubits are encoded in the stable electronic states of these ions, with quantum gates implemented precisely using laser pulses. The inherent identicality of natural atoms provides excellent qubit uniformity, while their strong isolation from the environment leads to long coherence times, a critical advantage for maintaining quantum information during lengthy computations [8]. A key strength of this architecture is its inherent all-to-all connectivity via collective motional modes, simplifying the implementation of quantum algorithms that require extensive qubit interactions [9].

Superconducting Qubits are engineered quantum circuits fabricated on semiconductor chips. These macroscopic circuits, typically based on Josephson junctions, exhibit quantum behavior when cooled to temperatures near absolute zero (15-20 mK) in dilution refrigerators [8]. They leverage microwave pulses for qubit control and readout. This platform's primary advantage lies in its rapid gate operations (nanoseconds) and its compatibility with established semiconductor microfabrication techniques, which facilitates scaling to larger qubit counts [8]. However, this comes with the challenge of shorter coherence times and the need for complex, multi-layer wiring and extreme cryogenic infrastructure.

Cat Qubits represent a more recent, innovative approach designed for inherent noise resilience. Rather than relying on a two-level physical system, a cat qubit encodes logical quantum information into the phase space of a superconducting microwave resonator, using two coherent states (e.g., |α⟩ and |−α⟩) as the basis [10]. Through continuous driving and engineered nonlinearity (often with the help of a Josephson circuit), the system is stabilized to protect against the dominant error type—bit-flips or phase-flips—creating a biased-noise qubit [10]. This intrinsic protection can drastically reduce the resource overhead required for quantum error correction.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Leading Quantum Hardware Platforms

| Performance Metric | Trapped Ions | Superconducting Qubits | Cat Qubits (Emerging) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Qubit Type | Natural atoms (e.g., Ybâº) | Engineered circuits (Josephson junctions) | Stabilized photonic states in a resonator |

| Operating Temperature | Room-temperature vacuum chamber | ~15-20 mK (cryogenic) | ~15 mK (cryogenic) |

| Coherence Time | Seconds [8] | 100-200 microseconds [8] | Designed for intrinsic bit-flip suppression [10] |

| Gate Fidelity (2-qubit) | 99.99%+ (reported) [8] | ~99.85% (e.g., IBM Eagle) [8] | N/A (Early R&D) |

| Gate Speed (2-qubit) | Millisecond range | Nanosecond range [8] | N/A (Early R&D) |

| Native Connectivity | All-to-all [9] | Nearest-neighbor (various topologies) | N/A (Early R&D) |

| Key Commercial Players | IonQ, Quantinuum | IBM, Google, AWS | AWS (Ocelot chip) [9] |

Experimental Performance and Noise Resilience

Recent experimental studies highlight the distinct noise profiles and resilience strategies of each platform, which are crucial for assessing their suitability for chemical simulations.

Noise-Resilient Entangling Gates for Trapped Ions: Research has demonstrated that introducing weak an-harmonicities to the trapping potential of ions enables control schemes that achieve amplitude-noise-resilience, a crucial step toward maintaining gate fidelity under experimental imperfections. This approach leverages the intrinsically an-harmonic Coulomb interaction or micro-structured traps to design operations that are consistent with state-of-the-art experimental requirements [11].

Digital-Analog Quantum Computing (DAQC) for Superconductors: A 2024 study compared pure digital (DQC) and digital-analog (DAQC) paradigms on superconducting processors for running key algorithms like the Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT). The research found that the DAQC paradigm, which combines the flexibility of single-qubit gates with the robustness of analog blocks, consistently surpassed digital approaches in fidelity, especially as the processor size increased. This is because DAQC reduces the number of error-prone two-qubit gates by leveraging the natural interaction Hamiltonian of the quantum processor [12].

Biased-Noise Circuits for Cat Qubits: Theoretical and experimental work has shown that for circuits designed specifically for biased-noise qubits (like cat qubits), the impact of the dominant bit-flip errors can be managed with only a polynomial overhead in algorithm repetitions, even for large circuits containing up to 10ⶠgates. This is a significant advantage over unbiased noise models, where the required overhead is often exponential. This property allows for the design of scalable noisy quantum circuits that remain reliable for specific computational tasks [10].

Experimental Protocols for Noise-Resilient Metrology and Simulation

A Hybrid Quantum Metrology Protocol

A pioneering protocol for noise-resilient quantum metrology integrates a quantum sensor with a quantum computer, directly addressing the bottleneck of noisy measurements. The workflow, detailed below, was experimentally validated using Nitrogen-Vacancy (NV) centers in diamond and simulated with superconducting processors [13].

Diagram 1: Quantum Metrology with a Quantum Processor

Step 1: Sensor Initialization. The protocol begins by initializing a quantum sensor (e.g., an NV center) in a highly sensitive, possibly entangled, probe state ( \rho0 = |\psi0\rangle\langle\psi_0| ). Entanglement is key here for surpassing the standard quantum limit and approaching the Heisenberg limit (HL) in precision [13].

Step 2: Noisy Parameter Encoding. The probe interacts with the target external field (e.g., a magnetic field of strength ( \omega )), imprinting a phase ( \phi = \omega t ). Crucially, this evolution happens under realistic noise, modeled by a superoperator ( \tilde{\mathcal{U}}\phi = \Lambda \circ U\phi ), where ( \Lambda ) is the noise channel. The final state of the sensor is a noise-corrupted mixed state ( \tilde{\rho}_t ) [13].

Step 3: Quantum State Transfer. Instead of directly measuring the noisy sensor output—the conventional approach—the quantum state ( \tilde{\rho}_t ) is transferred to a more stable quantum processor. This transfer is achieved via quantum state transfer or teleportation, bypassing the inefficient classical data-loading bottleneck [13].

Step 4: Quantum Processing (qPCA). On the quantum processor, quantum Principal Component Analysis (qPCA) is applied to the state ( \tilde{\rho}t ). This quantum machine learning technique filters out the noise-dominated components of the density matrix, efficiently extracting the dominant, signal-rich component. The output is a noise-resilient state ( \rho{NR} ) [13].

Step 5: Final Measurement. The purified state ( \rho_{NR} ) is then measured on the quantum processor. Experimental implementation with NV centers showed this method could enhance measurement accuracy by 200 times under strong noise. Simulations of a distributed superconducting system showed the Quantum Fisher Information (QFI—a measure of precision) improved by 52.99 dB, bringing it much closer to the Heisenberg Limit [13].

High-Precision Measurement Protocol for Molecular Energy Estimation

For near-term hardware, achieving chemical precision (∼1.6×10â»Â³ Hartree) in molecular energy calculations requires sophisticated error mitigation at the measurement level. The following protocol, implemented on IBM's superconducting Eagle r3 processor, reduced measurement errors from 1-5% to 0.16% for the BODIPY molecule [14].

1. Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements:

- Function: Use a set of measurement bases that fully characterizes the quantum state, allowing for the estimation of multiple observables from the same data set.

- Benefit: Provides a seamless interface for error mitigation and reduces total circuit executions by enabling efficient post-processing [14].

2. Locally Biased Random Measurements:

- Function: A shot-efficient strategy that prioritizes measurement settings with a larger impact on the final energy estimation.

- Benefit: Dynamically reduces the number of measurement shots ("shot overhead") required to reach a target precision while preserving the IC nature of the data [14].

3. Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) with Repeated Settings:

- Function: Periodically characterize the readout noise of the quantum device by performing QDT in parallel with the main algorithm.

- Benefit: The calibrated noise model is used to build an unbiased estimator for the molecular energy, effectively mitigating readout errors. Reusing the same measurement settings reduces "circuit overhead" [14].

4. Blended Scheduling:

- Function: Interleave circuits for the main algorithm, QDT, and calibration across the timeline of the experiment.

- Benefit: Mitigates the impact of time-dependent noise (e.g., drift) by ensuring that calibration data remains relevant to the computation data throughout the job execution [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Experimental Tools for Noise-Resilient Quantum Simulation

| Tool / Technique | Primary Function | Relevance to Chemical Simulations |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Principal Component Analysis (qPCA) | Noise filtering of quantum states; extracts the dominant signal from a noisy density matrix [13]. | Purifies the output state of a quantum sensor or a shallow quantum circuit before measurement, enhancing accuracy for parameter estimation tasks. |

| Digital-Analog Quantum Computing (DAQC) | A computing paradigm that uses analog Hamiltonian evolutions combined with digital single-qubit gates [12]. | Reduces the number of error-prone two-qubit gates in algorithms like QFT and Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE), leading to higher fidelity simulations. |

| Biased-Noise Qubit Compiler | A compiler that maps quantum circuits into a native gate set that preserves a hardware's noise bias [10]. | When using cat qubits or similar platforms, it ensures algorithms are constructed to leverage intrinsic error protection, reducing resource overhead. |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | An error mitigation technique that intentionally increases circuit noise to extrapolate back to a zero-noise result [12]. | Can be applied to DAQC and other paradigms to further mitigate decoherence and intrinsic errors, boosting fidelity for observable calculations. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | Characterizes the readout error map of a quantum device [14]. | Critical for achieving high-precision measurements of molecular energy observables by providing a model for readout error mitigation. |

| NSC 228155 | NSC 228155, MF:C11H6N4O4S, MW:290.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| NSC-311068 | NSC-311068, CAS:73768-68-0, MF:C10H6N4O4S, MW:278.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Hardware Selection & Strategic Trade-offs for Chemical Simulations

The choice of hardware for a specific chemical simulation problem involves careful weighing of resource constraints and algorithmic demands. The relationship between these factors and hardware performance is summarized in the diagram below.

Diagram 2: Hardware Selection Logic for Chemical Simulations

Select Trapped Ions for high-fidelity, all-to-all coupled simulations. This platform is optimal for simulating small to medium-sized molecules where the algorithm requires deep circuits or extensive qubit interactions. Its long coherence times and high gate fidelity directly support the high-precision requirements for calculating molecular energy states. The trade-off is slower gate speed, which may limit computational throughput [8] [9].

Leverage Superconducting Qubits for rapid prototyping and shallow algorithms. When research workflows require fast iteration cycles or the quantum circuit is relatively shallow, the high gate speed of superconducting processors is advantageous. This makes them suitable for hybrid quantum-classical algorithms like VQE, where many circuit variations must be run quickly. The DAQC paradigm can be employed to mitigate its lower gate fidelity and limited connectivity [12] [8].

Invest in Cat Qubits for a long-term path to fault-tolerant quantum chemistry. For problems that will require large-scale, fault-tolerant quantum computers, cat qubits represent a strategic, forward-looking option. Their biased noise structure is specifically designed to reduce the resource overhead of quantum error correction. This makes them a compelling candidate for the eventual simulation of very large molecular systems, though the technology is still in early development [10].

The quantum hardware landscape offers multiple, divergent paths toward the ultimate goal of noise-resilient chemical simulation. No single platform currently dominates across all metrics; trapped ions excel in coherence and fidelity, superconducting qubits in speed and scalability, and cat qubits offer a promising route to efficient error correction. The strategic takeaway for researchers in drug development and materials science is that the selection of a quantum hardware platform must be a deliberate choice aligned with the specific demands of the simulation problem—its required precision, circuit depth, and connectivity. As these hardware roadmaps continue to advance, converging on the creation of logical qubits with lower overhead, the focus will shift from mitigating native noise to orchestrating fault-tolerant computations, ultimately unlocking the full potential of quantum-assisted discovery.

The era of Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) computing is defined by quantum processors ranging from 50 to a few hundred qubits, where noise significantly constrains computational capabilities [15]. For researchers in fields like chemical simulations for drug development, this noise presents a fundamental challenge, as it can render simulation results meaningless if not properly characterized and mitigated. Noise in these devices arises from multiple sources, including environmental decoherence, gate imperfections, measurement errors, and qubit crosstalk [15]. Understanding these phenomena is not merely an engineering concern but a prerequisite for performing reliable computational chemistry and molecular simulations on quantum hardware. The delicate quantum superpositions and entanglement necessary for simulating molecular systems are exceptionally vulnerable to these disruptive influences, making noise characterization a critical path toward quantum-accelerated drug discovery.

This technical guide examines the core noise mechanisms in NISQ devices, with a specific focus on their implications for resource-efficient chemical simulations. We delve beyond simplified models to explore sophisticated frameworks for characterizing spatially and temporally correlated noise, which is essential for developing noise-resilient simulation algorithms [16]. Furthermore, we analyze the profound tradeoffs between coherence time, gate fidelity, and operational speed that directly impact the design and execution of quantum algorithms for simulating molecular Hamiltonians. By providing a detailed overview of current characterization techniques, performance benchmarks, and mitigation strategies, this guide aims to equip computational scientists and drug development professionals with the knowledge needed to navigate the current limitations of quantum hardware and identify promising pathways toward practical quantum advantage in chemical simulation.

Fundamental Noise Processes and Their Impact

Coherent Errors vs. Incoherent Noise

In NISQ devices, noise manifests primarily through two distinct mechanisms: coherent errors and incoherent noise. Coherent errors arise from systematic miscalibrations in control systems that lead to predictable, unitary transformations away from the intended quantum operation. These include miscalibrations in pulse amplitude, frequency, or phase that result in over- or under-rotation of the qubit state. Unlike stochastic errors, coherent errors do not involve energy loss to the environment and can potentially be reversed with precise characterization. However, they accumulate in a predictable manner throughout a quantum circuit, leading to significant algorithmic drift, particularly in long-depth quantum simulations.

Incoherent noise, conversely, results from stochastic interactions between the qubit and its environment, leading to decoherence and energy dissipation. The primary manifestations are:

- Relaxation (T₠process): Energy loss from the qubit to its environment, causing a transition from the excited |1⟩ state to the ground |0⟩ state.

- Dephasing (Tâ‚‚ process): Loss of phase information without energy loss, resulting from stochastic variations in the qubit frequency that destroy quantum superposition states.

- State preparation and measurement (SPAM) errors: Inaccuracies in initializing qubits to a known state and correctly measuring the final state.

For chemical simulations, these processes directly impact the fidelity of molecular ground state energy calculations. The Lindblad master equation (LME) provides a comprehensive framework for modeling these effects, describing the non-unitary evolution of a quantum system's density matrix when coupled to a Markovian environment [15]. The LME effectively captures how quantum gates act as probability mixers, with environmental interactions introducing deviations from ideal programmed behavior.

Mathematical Modeling of Decoherence

The Lindblad formalism offers a powerful approach to quantify decoherence effects on universal quantum gate sets. The general form of the Lindblad master equation is:

[\frac{dÏ}{dt} = -\frac{i}{\hbar}[H, Ï] + \sumk \left( Lk Ï Lk^\dagger - \frac{1}{2} { Lk^\dagger L_k, Ï } \right)]

Where (Ï) is the density matrix, (H) is the system Hamiltonian, and (Lk) are the Lindblad operators representing different decoherence channels. For a simple qubit system, common Lindblad operators include (L1 = \frac{1}{\sqrt{T1}} σ-) modeling relaxation and (L2 = \frac{1}{\sqrt{T2}} σ_z) modeling pure dephasing [15].

Recent research has expanded Lindblad-based modeling to include finite-temperature effects, with a 2025 study presenting an explicit analysis of multi-qubit systems interacting with a thermal reservoir [15]. This approach incorporates both spontaneous emission and absorption processes governed by the Bose-Einstein distribution, enabling fully temperature-dependent modeling of quantum decoherence—a critical consideration for simulating molecular systems at biologically relevant temperatures.

Advanced Noise Characterization Frameworks

Spatial and Temporal Noise Correlations

A significant limitation in early noise models was their inability to capture correlated noise across space and time. Simplified models typically only capture single instances of noise, isolated to one moment and one location in the quantum processor [16]. However, the most significant sources of noise in actual devices spread across both space and time, creating complex correlation patterns that dramatically impact quantum error correction strategies.

Recent breakthroughs at Johns Hopkins APL and Johns Hopkins University have addressed this challenge by developing a novel framework that exploits mathematical symmetry to characterize these complex noise correlations [16]. By applying a mathematical technique called root space decomposition, researchers can radically simplify how quantum systems are represented and analyzed in the presence of correlated noise. This technique organizes quantum system actions into a ladder-like structure, where each rung represents a discrete state of the system [16]. Applying noise to this structured system reveals whether specific noise types cause transitions between states, enabling precise classification of noise into distinct categories that inform targeted mitigation strategies.

This approach is particularly valuable for chemical simulation applications, as it helps determine whether noise processes will disrupt the carefully prepared quantum states representing molecular configurations. By capturing how noise propagates through multi-qubit systems simulating molecular orbitals, researchers can develop more effective error mitigation strategies tailored to quantum chemistry algorithms.

Dynamical Decoupling and Fourier Transform Noise Spectroscopy

Traditional noise characterization has relied heavily on Dynamical Decoupling Noise Spectroscopy (DDNS), which applies precise sequences of control pulses to qubits and observes their response to infer environmental noise spectra [17]. While effective, DDNS is complex, requires numerous nearly-instantaneous laser pulses, and relies on significant assumptions about underlying noise processes, making it cumbersome for practical deployment [17].

A recently developed alternative, Fourier Transform Noise Spectroscopy (FTNS), offers a more streamlined approach by focusing on qubit coherence dynamics through simple experiments like free induction decay (FID) or spin echo (SE) [17]. This method applies a Fourier transform to time-domain coherence measurements, converting them into frequency-domain noise spectra that reveal which noise frequencies are present and their relative strengths [17]. The FTNS method handles various noise types, including complex patterns challenging for DDNS, with fewer control pulses and less restrictive assumptions [17].

For research teams performing chemical simulations, FTNS provides a more accessible pathway to characterize the specific noise environment affecting their quantum computations, enabling customized error mitigation based on the actual laboratory conditions during algorithm execution.

Experimental Protocols for Noise Characterization

Protocol 1: Randomized Benchmarking for Gate Fidelity

Objective: To estimate the average error rate per quantum gate using long sequences of random operations, providing a standardized metric for comparing gate performance across different qubit platforms.

Methodology:

- Initialization: Prepare the qubit in a known ground state, typically |0⟩.

- Sequence Application: Apply a long sequence of m random Clifford gates to the qubit. Clifford gates are used because they form a group that can be efficiently simulated classically, and they randomize errors.

- Inversion Operation: Apply a final recovery gate that would return the ideal system to the initial state if no errors occurred.

- Measurement: Measure the final state to determine the probability of returning to the initial state (survival probability).

- Repetition and Averaging: Repeat steps 1-4 for many different random sequences of the same length m to average over sequence-specific effects.

- Sequence Length Scaling: Repeat the entire procedure for multiple values of m (sequence lengths), typically ranging from tens to thousands of gates.

Data Analysis: The average survival probability F(m) is plotted against sequence length m. The data is fitted to an exponential decay model: [F(m) = A \cdot p^m + B] where p is the depolarizing parameter, and A, B account for SPAM errors. The average error per gate (r) is then calculated as: [r = (1 - p) \cdot (d - 1)/d] where d is the dimension of the system (d=2 for a single qubit).

Implementation Example: The University of Oxford team used this protocol to demonstrate single-qubit gate errors below (1 \times 10^{-7}) (fidelities exceeding 99.99999%) using a single trapped (^{43}\text{Ca}^+) ion [18]. They applied sequences of up to tens of thousands of Clifford gates, confirming infrequent errors with high statistical confidence and identifying qubit decoherence from residual phase noise as the dominant error contribution [18].

Protocol 2: Qutrit-Enhanced Noise Characterization

Objective: To reduce gauge ambiguity in characterizing both SPAM and gate noise by leveraging additional energy levels (qutrits) beyond the standard computational qubit subspace.

Methodology:

- System Identification: Identify a physical qubit system with accessible higher energy levels (qutrit structure). Superconducting quantum devices often naturally provide these additional levels.

- Qutrit Control Calibration: Develop high-quality control pulses that can manipulate not only the standard |0⟩-|1⟩ transitions but also |1⟩-|2⟩ transitions within the qutrit subspace.

- Extended Gate Set Implementation: Implement an extended set of quantum gates that operate on the full qutrit space rather than being restricted to the qubit subspace.

- Comparative Measurements: Perform parallel noise characterization experiments using both standard qubit-based protocols and the enhanced qutrit-enabled protocols.

- Gauge Freedom Analysis: Apply comprehensive theory on the identifiability of n-qudit SPAM noise given high-quality single-qudit control, specifically analyzing subsystem depolarizing maps that describe gauge freedoms.

Data Analysis: The additional information from qutrit dynamics helps resolve ambiguities (gauge freedoms) in standard noise characterization. By comparing the results from qubit-only and qutrit-enhanced protocols, researchers can isolate specific error sources that would otherwise be conflated in standard characterization methods.

Implementation Example: Research published in June 2025 demonstrated this approach on a superconducting quantum computing device, showing how extra energy levels reduce gauge ambiguity in characterizing both SPAM and gate noise in the qubit subspace [19]. This qutrit-enabled enhancement provides more precise noise characterization, which is particularly valuable for identifying correlated errors in multi-qubit systems used for chemical simulations.

Performance Benchmarks and Error Metrics

State-of-the-Art Performance Metrics

Table 1: Quantitative Error Metrics Across Qubit Platforms

| Qubit Platform | Single-Qubit Gate Error | Two-Qubit Gate Error | Coherence Time (Tâ‚‚) | SPAM Error | Research Group / Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trapped Ion ((^{43}\text{Ca}^+)) | (1.5 \times 10^{-7}) (99.99999% fidelity) | Not specified | ~70 seconds | ~(1 \times 10^{-3}) | University of Oxford [18] |

| Superconducting (Fluxonium) | ~(2 \times 10^{-5}) (99.998% fidelity) | ~(5 \times 10^{-4}) | Microsecond to millisecond scale | ~(1 \times 10^{-3}) | Industry research (2025) [18] |

| Trapped Ion (Commercial systems) | >99.99% fidelity | 99.9% fidelity ( (1 \times 10^{-3}) error) | Tens of seconds | Not specified | Quantinuum [18] |

| Superconducting (Transmon) | ~99.9% fidelity ( (1 \times 10^{-3}) error) | ~99% fidelity ( (1 \times 10^{-2}) error) | Hundreds of microseconds | ~(1 \times 10^{-2}) | Industry standard (IBM, Google) [18] |

| Neutral Atom | ~99.5% fidelity ( (5 \times 10^{-3}) error) | ~99% fidelity ( (1 \times 10^{-2}) error) | Millisecond scale | Not specified | Research systems [18] |

Error Budget Analysis for Chemical Simulations

For chemical simulations on NISQ devices, the overall algorithm fidelity depends on the cumulative effect of all error sources throughout the quantum circuit. A comprehensive error budget analysis must consider:

- Gate-dependent errors: Varying error rates for different gate types (single-qubit vs. two-qubit gates)

- Idling errors: Decoherence during periods between gate operations

- SPAM errors: Cumulative effect of state preparation and measurement inaccuracies

- Cross-talk: Unwanted interactions between adjacent qubits during gate operations

- Control system errors: Timing jitter, amplitude drift, and phase noise in control pulses

The Oxford team's achievement of (1.5 \times 10^{-7}) single-qubit gate error represents a significant milestone, as these operations can now be considered effectively error-free compared to other noise sources [18]. In their system, SPAM errors at approximately (1 \times 10^{-3}) became the dominant error source, four orders of magnitude larger than the single-qubit gate error [18]. This highlights a critical transition point where further improvements to single-qubit gates provide diminishing returns, and research focus must shift to improving two-qubit gate fidelity, memory coherence, and measurement accuracy.

For chemical simulation applications, this error budgeting is particularly important when determining the optimal partitioning of quantum and classical resources in hybrid quantum-classical algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE). Understanding which error sources dominate for specific molecular system sizes and circuit depths enables more efficient error mitigation strategy selection.

Table 2: Quantum Error Mitigation Techniques for Chemical Simulations

| Mitigation Technique | Mechanism | Overhead Cost | Applicable Error Types | Suitability for Chemical Simulations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | Artificially increases noise then extrapolates to zero-noise limit | Moderate (requires circuit execution at multiple noise levels) | All error types | High - minimally modifies algorithm structure |

| Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC) | Applies inverse noise operations stochastically | High (requires characterization of noise channels) | Gate-dependent errors | Medium - requires comprehensive noise characterization |

| Tensor-Network Error Mitigation (TEM) | Leverages tensor network contractions to estimate expected values | Variable (depends on bond dimension) | All error types | Medium-High - effective for shallow circuits |

| Dynamical Decoupling | Applies pulse sequences to decouple qubits from environment during idling | Low (adds minimal extra gates) | Decoherence during idle periods | High - especially beneficial for memory-intensive circuits |

| Symmetry Verification | Post-selects results that conserve known symmetries | Low (only requires classical post-processing) | Errors that violate physical symmetries | Very High - molecular systems have known symmetries |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Platforms for Quantum Noise Characterization

| Research Reagent / Platform | Function / Application | Key Features / Benefits | Representative Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trapped Ion Systems ((^{43}\text{Ca}^+)) | Ultra-high-fidelity qubit operations | Microwave-driven gates for stability, room temperature operation, long coherence times (~70s) | University of Oxford's record-setting (10^{-7}) error rate [18] |

| Superconducting Qubits with Qutrit Access | Enhanced noise characterization | Leverages higher energy levels to resolve gauge ambiguities in noise characterization | Scheme for enhancing noise characterization using additional energy levels [19] |

| Nitrogen-Vacancy (NV) Centers in Diamond | Quantum sensing and noise spectroscopy | Stable quantum systems at room temperature, capable of implementing FTNS | JILA's experimental testing of FTNS method [17] |

| Molecular Qubits and Magnets | Alternative platform for noise spectroscopy | Chemical tunability, potential for specialized quantum simulations | Ohio State University's implementation of FTNS [17] |

| Root Space Decomposition Framework | Mathematical tool for correlated noise analysis | Classifies noise into mitigation categories using symmetry principles | Johns Hopkins' symmetry-based noise characterization [16] |

| Fourier Transform Noise Spectroscopy (FTNS) | Streamlined noise spectrum reconstruction | Fewer control pulses than DDNS, handles complex noise patterns | JILA and CU Boulder's alternative to dynamical decoupling [17] |

| Lindblad Master Equation (LME) Modeling | Comprehensive decoherence modeling | Captures both noise and thermalization effects on gate operations | Unified framework for characterising probability transport in quantum gates [15] |

| NSC 42834 | NSC 42834, CAS:195371-52-9, MF:C23H24N2O, MW:344.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| NSC61610 | NSC61610, CAS:500538-94-3, MF:C34H24N6O2, MW:548.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implications for Noise-Resilient Chemical Simulations

The advances in noise characterization and mitigation directly impact the feasibility and efficiency of quantum computational chemistry. For drug development professionals seeking to leverage quantum simulations for molecular design, several key implications emerge:

First, the asymmetry between single and two-qubit gate fidelities dictates algorithm design choices. With single-qubit gates reaching near-perfect fidelity in trapped-ion systems [18], while two-qubit gates remain several orders of magnitude more error-prone, optimal chemical simulation algorithms should minimize two-qubit gate counts, even at the cost of additional single-qubit operations. This principle influences how molecular Hamiltonians are mapped to quantum circuits and which ansätze are selected for variational algorithms.

Second, the growing understanding of spatially and temporally correlated noise [16] enables more intelligent qubit mapping strategies for molecular simulations. By characterizing how noise correlates across specific qubit pairs in a processor, researchers can map strongly interacting molecular orbitals to qubits with lower correlated error rates, significantly improving simulation fidelity without increasing physical resources.

Finally, the development of platform-specific error mitigation allows researchers to tailor their approach based on available hardware. For trapped-ion systems with ultra-high single-qubit fidelity but slower gate operations, different mitigation strategies will be optimal compared to superconducting systems with faster operations but higher error rates. This hardware-aware approach to quantum computational chemistry represents a maturation of the field toward practical application in drug development pipelines.

The continued advancement of noise characterization techniques, particularly those leveraging mathematical frameworks like symmetry analysis [16] and Fourier transform spectroscopy [17], provides an essential foundation for developing the next generation of noise-resilient quantum algorithms for chemical simulation. As these tools become more sophisticated and accessible, researchers in drug development will be increasingly equipped to harness quantum advantage for simulating complex molecular interactions relevant to therapeutic design.

For researchers in chemistry and drug development, quantum computing presents a transformative opportunity to simulate molecular systems with unprecedented accuracy. However, the path to practical quantum advantage is navigated by understanding and balancing a set of core physical resource metrics. On noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, the interplay between qubit count, circuit depth, gate fidelity, and coherence time dictates the feasibility and accuracy of any simulation. This guide details these key metrics within the context of noise-resilient chemical simulation, providing a framework for researchers to assess hardware capabilities and design experiments that effectively manage the inherent trade-offs in today's quantum resources.

Defining the Core Metrics

Qubit Count

Qubit count refers to the number of distinguishable quantum bits available for computation. For chemical simulations, this metric directly determines the size and complexity of the molecular system that can be modeled.

- Role in Chemical Simulation: The number of qubits required scales with the number of spin orbitals used to represent a molecule's electronic structure. For example, simulating complex molecules like Cytochrome P450, a key human enzyme for drug metabolism, requires a substantial qubit register to represent its active site and reaction mechanisms [20].

- Beyond Raw Count: The utility of a quantum processor is not defined by qubit count alone. A significant shift in the industry in 2025 has been from a pure "qubit count" focus toward qubit quality and stabilization [21]. Furthermore, the connectivity between qubits dramatically influences the efficiency with which a quantum circuit can be executed.

Gate Fidelity

Gate fidelity is a measure of the accuracy of a quantum logic operation. It quantifies how close the actual output state of a qubit is to the ideal theoretical state after a gate operation. High fidelities are essential for achieving meaningful, uncorrupted results.

- Fidelity Targets: For fault-tolerant quantum computation, fidelities must exceed 99.9%. In 2025, leading research has demonstrated fidelities at or above this threshold [22] [23]. For instance:

- Impact on Simulation: Low gate fidelity introduces errors that propagate through a quantum circuit. In a complex simulation like a Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) calculation for molecular energy, these errors can lead to inaccurate potential energy surfaces and invalidate the final result.

Coherence Time

Coherence time (or qubit lifetime) defines the duration for which a qubit can maintain its quantum state before information is lost to decoherence from environmental noise. It is the ultimate time limit for computation.

- Typical Ranges: Coherence times vary significantly by qubit platform. For example, SPINQ's superconducting QPUs feature coherence times of up to ~100 microseconds (μs) [22], while advances in molecular-beam epitaxy (MBE) have boosted the coherence times of erbium atoms used in quantum networking to over 10 milliseconds [24].

- The Runtime Constraint: The total execution time of a quantum circuit, which is a function of the number of gates and their speed, must be shorter than the coherence time of the qubits involved. This is a fundamental constraint for deep quantum circuits required for complex chemical simulations.

Circuit Depth

Circuit depth is the number of computational steps, or gate operations, in the longest path of a quantum circuit. It is a measure of a circuit's complexity.

- Relationship with Coherence Time and Fidelity: Circuit depth is intrinsically linked to both coherence time and gate fidelity. A deeper circuit takes more time to execute (risking decoherence) and involves more gate operations (accumulating more errors). The maximum feasible circuit depth for a given processor is therefore determined by

Coherence Time / (Gate Time × Fidelity). - Relevance to Algorithms: Quantum algorithms for chemical simulation, such as Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) or deep VQE ansatzes, can require substantial circuit depths to achieve the desired accuracy, making them primary candidates for error mitigation and correction techniques.

Quantitative Metrics of Leading Quantum Platforms

The table below synthesizes performance data for various state-of-the-art quantum platforms as of 2025, providing a comparative view for researchers evaluating hardware.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of Leading Quantum Platforms

| Platform / System | Qubit Count | Reported Gate Fidelity | Reported Coherence Time | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Google Willow (Superconducting) | 105 physical qubits [21] | Not explicitly stated (demonstrated error correction "below threshold") [21] | Not explicitly stated | Demonstrated exponential error reduction; key for error correction milestones [21]. |

| SPINQ QPU Series (Superconducting) | 2–20 (modular) [22] | Single-qubit: ≥ 99.9%; Two-qubit: ≥ 99% [22] | ~20–102 μs [22] | Emphasizes industrial readiness, mass-producibility, and plug-and-play integration [22]. |

| Germanium Hole Spin Qubit (Semiconductor) | 1 (device featured) [25] | Maximum fidelity of 99.9% (geometric gates) [25] | ( T_2^* ) = 136 ns (extended to 6.75 μs with dynamical decoupling) [25] | Features noise-resilient geometric quantum computation; high-quality material system [25]. |

| MIT Fluxonium (Superconducting) | 1 (device featured) [23] | Single-qubit: 99.998% [23] | Not explicitly stated | Record-setting fidelity achieved via commensurate pulses to mitigate counter-rotating errors [23]. |

Table 2: Quantum Resource Requirements for Example Scientific Workloads (Projections)

| Scientific Workload Area | Estimated Qubits Required | Estimated Circuit Depth | Projected Timeline for Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Science (e.g., lattice models, strongly correlated electrons) | Moderate to High | High | 5–10 years [20] |

| Quantum Chemistry (e.g., complex molecule simulation) | Moderate to High | Moderate to High | 5–10 years (algorithm requirements dropping fast) [20] |

| Pharmaceutical Research (e.g., drug molecule interaction) | High | High | Demonstrated in pioneering simulations (e.g., Cytochrome P450) [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Metrics

To ensure reliable simulation results, researchers must understand how these metrics are validated. The following are detailed methodologies cited from recent experiments.

Protocol for Gate Fidelity Characterization using Gate Set Tomography (GST)

A study on a germanium hole spin qubit provides a clear protocol for characterizing gate fidelity with high precision [25].

- Objective: To benchmark the control fidelities of single-qubit gates (I, X/2, Y/2) and evaluate the performance of geometric quantum gates.

- Experimental Setup:

- Device: A double quantum dot (DQD) fabricated on an undoped strained germanium wafer, with a hole spin qubit confined using plunger and barrier gates [25].

- Initialization & Readout: The spin state is initialized into the T- state. Readout is performed via enhanced latching readout (ELR) based on Pauli spin blockade (PSB) in the (1,1)-(2,0) charge transition region [25].

- Qubit Control: Qubit operations are performed via electric dipole spin resonance (EDSR) by applying microwave pulses to a gate electrode [25].

- Procedure:

- Rabi Oscillation Measurement: A rectangular microwave burst of varying duration (τburst) is applied to observe coherent qubit rotations and determine the π-rotation time (tπ) [25].

- Gate Set Tomography (GST): A comprehensive set of gate sequences is applied to the qubit. The resulting output states are measured to reconstruct the actual quantum operations performed and estimate their fidelity compared to the ideal gates [25].

- Geometric Gate Implementation: Non-adiabatic geometric quantum computation (NGQC) is implemented by designing specific evolution paths to generate Abelian geometric phases, making the gates resilient to certain types of noise [25].

- Key Findings: The study achieved a maximum control fidelity of 99.9% for geometric X/2 and Y/2 gates, demonstrating that these gates maintained fidelities above 99% even with significant microwave frequency detuning, highlighting their noise-resilient property [25].

Protocol for Coherence Time Extension via Material Science

A breakthrough in quantum networking demonstrates how coherence time, a critical limiting factor, can be radically improved through advanced material fabrication [24].

- Objective: To extend the coherence time of individual erbium atoms to enable long-distance quantum links.

- Experimental Innovation:

- Traditional Method (Czochralski): The rare-earth-doped crystal is created by melting ingredients at over 2,000°C and slowly cooling, then chemically "carved" into the final component. This process introduces impurities and defects that limit coherence [24].

- Novel Method (Molecular-Beam Epitaxy - MBE): The crystal is built atom-by-atom in a bottom-up approach, spraying thin layer after thin layer to form the exact final device. This results in a material of exceptionally high purity [24].

- Procedure:

- Material Synthesis: The research team, collaborating with materials synthesis experts, adapted the MBE technique for the specific purpose of building rare-earth-doped crystals [24].

- Coherence Measurement: The coherence properties of the erbium atoms embedded in the MBE-grown crystal were measured, showing a dramatic increase from 0.1 milliseconds to over 10 milliseconds, with one case achieving 24 milliseconds [24].

- Key Findings: This material science innovation did not change the fundamental material but its fabrication, leading to a >100x improvement in coherence time. This theoretically supports a quantum connection spanning 4,000 km, a critical step towards a global quantum internet [24].

Visualizing Quantum Resource Interdependencies

The workflow of a quantum chemical simulation is constrained by the complex interplay between the core metrics. The following diagram maps these critical relationships and trade-offs.

Diagram Title: Quantum Simulation Workflow and Resource Constraints

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

This table details essential materials and core components driving recent advances in quantum hardware, as featured in the cited experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Advanced Quantum Platforms

| Item / Material | Function in Experiment / Platform | Key Outcome / Property |

|---|---|---|

| Strained Germanium Quantum Dots [25] | Host material for hole spin qubits. Combines strong spin-orbit interaction for all-electrical control with reduced hyperfine interaction from p-orbitals and net-zero nuclear spin isotopes. | Enables high-fidelity (99.9%), noise-resilient geometric quantum gates and fast Rabi frequencies [25]. |

| Fluxonium Qubits [23] | A type of superconducting qubit incorporating a "superinductor" to shield against environmental noise. | Lower frequency and enhanced coherence enabled MIT researchers to achieve record 99.998% single-qubit gate fidelity [23]. |

| MBE-Grown Rare-Earth-Doped Crystals [24] | Crystals (e.g., erbium-doped) fabricated via Molecular-Beam Epitaxy to act as spin-photon interfaces in quantum networks. | The bottom-up, high-purity fabrication resulted in coherence times >10 ms, enabling potential quantum links over 1,000+ km [24]. |

| Fidelipart Framework [26] | A software "reagent." A fidelity-aware partitioning framework that transforms quantum circuits into weighted hypergraphs for noise-resilient compilation on NISQ devices. | Reduces SWAP gates by 77.3-100% and improves estimated circuit fidelity by up to 250% by minimizing cuts through error-prone operations [26]. |

| Commensurate Pulses [23] | A control technique involving precisely timed microwave pulses. | Mitigates counter-rotating errors in low-frequency qubits like fluxonium, enabling high-speed, high-fidelity gates [23]. |

| RUC-1 | RUC-1, MF:C11H15N5OS, MW:265.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MAT2A inhibitor 2 | MAT2A inhibitor 2, CAS:13299-99-5, MF:C18H24ClN3O3, MW:365.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The pursuit of noise-resilient chemical simulations on quantum hardware requires a nuanced strategy that prioritizes qubit quality over quantity. As of 2025, the field has moved beyond simply counting qubits to a more holistic view where high gate fidelities (≥99.9%) and long coherence times are the true enablers of deeper, more meaningful circuits. For drug development professionals, this means that initial simulations of pharmacologically relevant molecules are within reach, but scaling to massive, high-precision calculations will require continued advances in error correction and hardware stability. The path forward lies in the co-design of algorithms, error mitigation strategies like those demonstrated in geometric quantum computation [25], and hardware, ensuring that every available quantum resource is used to its maximum potential in the quest for scientific discovery.

{#core-tradeoff}

Core Tradeoff: Algorithmic Precision vs. Hardware-Induced Error in Chemical Calculations

In the pursuit of quantum utility for chemical simulations, researchers navigate a fundamental tension: the desire for high-precision, chemically accurate results demands increasingly complex quantum algorithms, but these very algorithms are more vulnerable to the pervasive noise present on modern quantum hardware. This technical guide examines the core tradeoff between algorithmic precision and hardware-induced error, framing it within the broader context of quantum resource tradeoffs essential for achieving noise-resilient chemical simulations. We present current experimental strategies, from error correction to error mitigation, that are shaping the path toward practical quantum computational chemistry.

The Fundamental Challenge: Precision at the Cost of Resilience

Quantum algorithms for chemistry, such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE), are designed to solve the electronic structure problem with high precision. However, their performance on current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices is critically limited by hardware imperfections. The relationship is often inverse: as an algorithm's complexity and precision increase, so does its susceptibility to hardware noise [27].

This noise manifests as decoherence, gate infidelities, and measurement errors, which collectively distort the computed energy landscape. For example, in VQE, finite-shot sampling noise creates a stochastic cost landscape, leading to "false variational minima" and a statistical bias known as the "winner's curse," where the lowest observed energy is artificially biased downward [27]. This effect can even cause violations of the variational principle, a fundamental tenet of quantum chemistry. Furthermore, the Barren Plateaus (BP) phenomenon renders optimization practically impossible for large qubit counts, as gradients vanish exponentially [27].

Experimental Paradigms: Managing the Tradeoff

The field has developed three primary, non-exclusive strategies to manage this tradeoff: (1) employing Quantum Error Correction (QEC) to create more resilient logical qubits; (2) developing sophisticated Quantum Error Mitigation (QEM) techniques that post-process noisy results; and (3) designing noise-resilient optimization strategies for variational algorithms.

Quantum Error Correction: Building Resilience Logically

QEC aims to build fault tolerance directly into the computation by encoding logical qubits into many physical qubits. A landmark experiment by Quantinuum demonstrated the first complete quantum chemistry simulation using QEC on its H2-2 trapped-ion quantum computer [28] [29].

- Experimental Protocol: The researchers calculated the ground-state energy of molecular hydrogen using the QPE algorithm. They encoded logical qubits using a seven-qubit color code. Mid-circuit error correction routines were inserted between computational operations to detect and correct errors in real-time. The experiment leveraged the H2 processor's high-fidelity gates, all-to-all connectivity, and native support for mid-circuit measurements [28].

- Performance and Tradeoffs: The QEC-protected circuit, involving up to 22 qubits and over 2,000 two-qubit gates, produced an energy estimate within 0.018 hartree of the exact value. Crucially, circuits with mid-circuit error correction outperformed those without, demonstrating that QEC can provide a net benefit even on today's hardware despite increased circuit complexity [28]. The primary tradeoff is the massive resource overhead, requiring more qubits and gates.

Table 1: Performance Data from Quantinuum's QEC Experiment [28]

| Metric | Result with QEC | Chemical Accuracy Target |

|---|---|---|

| Calculated Energy Error | 0.018 hartree | 0.0016 hartree |

| Algorithm Used | Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) | - |

| QEC Code | 7-qubit color code | - |

| Maximum Qubits Used | 22 | - |

| Key Finding | QEC improved performance despite added complexity | - |

Quantum Error Mitigation: Correcting Errors in Post-Processing

In contrast to QEC, QEM techniques acknowledge noise and attempt to subtract its effects classically after data is collected. These are typically less resource-intensive and are a mainstay of the NISQ era. A key advancement is Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM), which addresses a critical limitation of simpler methods [30].

- Experimental Protocol: Standard Reference-state Error Mitigation (REM) uses a single, classically tractable reference state (e.g., Hartree-Fock) to calibrate hardware noise. Its effectiveness plummets for strongly correlated systems (e.g., during bond dissociation), where the true wavefunction is a complex combination of multiple Slater determinants [30]. MREM generalizes this by using a multireference (MR) state—a linear combination of several dominant Slater determinants—as the reference. These MR states are engineered to have substantial overlap with the target ground state. The protocol involves:

- Classically generating a compact MR wavefunction from inexpensive methods.

- Preparing this state on the quantum hardware using efficient quantum circuits, often constructed with Givens rotations.

- Using the known exact energy of this MR state to calibrate and mitigate the noise affecting the target state during a VQE calculation [30].

- Performance and Tradeoffs: MREM significantly outperforms single-reference REM for strongly correlated systems like F2 and N2. The tradeoff is an increase in classical computation for generating the MR state and a more complex state preparation circuit on the quantum device, which could itself introduce more errors if not managed carefully [30].

Optimization Under Noise: Navigating a Rugged Landscape

The distortion of the energy landscape by noise necessitates robust classical optimizers for VQE. A comprehensive benchmark study evaluated gradient-based, gradient-free, and metaheuristic optimizers on molecular Hamiltonians (Hâ‚‚, Hâ‚„, LiH) under finite-sampling noise [27].

- Experimental Protocol: The study compared optimizers like SLSQP, BFGS (gradient-based), COBYLA (gradient-free), and evolutionary metaheuristics (CMA-ES, iL-SHADE) using the truncated Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz (tVHA). Performance was measured by the ability to find accurate energy minima and avoid false solutions created by noise [27].

- Performance and Tradeoffs: The study found that gradient-based methods often diverge or stagnate in noisy regimes. In contrast, adaptive metaheuristics, specifically CMA-ES and iL-SHADE, were the most effective and resilient. A key insight for population-based optimizers was to track the population mean energy instead of the best individual's energy to counteract the "winner's curse" bias. The tradeoff is that these robust optimizers typically require more function evaluations (quantum circuit executions) [27].

Table 2: Optimizer Performance Under Noisy VQE Conditions [27]

| Optimizer Type | Example Algorithms | Performance under Noise | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-Based | SLSQP, BFGS | Prone to divergence and stagnation | Sensitive to noisy gradients |

| Gradient-Free | COBYLA, Nelder-Mead | Moderate performance | Can be trapped in false minima |

| Metaheuristic | CMA-ES, iL-SHADE | Most effective and resilient | Higher computational cost per iteration; bias can be corrected via population mean |

A Roadmap for Resource Allocation: The Scientist's Toolkit

Choosing a strategy involves a careful assessment of available quantum and classical resources. The following table details key "research reagents" and their functions in the quest for noise-resilient chemical simulations.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Noise-Resilient Chemical Simulations

| Tool / Technique | Primary Function | Key Tradeoff / Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Error Correction (QEC) [28] [29] | Creates fault-tolerant logical qubits by encoding information across many physical qubits. | Very high qubit overhead; requires specific hardware capabilities (mid-circuit measurement). |

| Multi-Reference Error Mitigation (MREM) [30] | Extends error mitigation to strongly correlated systems using multi-determinant reference states. | Increased classical pre-computation and more complex quantum state preparation. |

| Adaptive Metaheuristic Optimizers (e.g., CMA-ES) [27] | Reliably navigates noisy, distorted cost landscapes in VQE to find true minima. | Requires a larger number of quantum circuit executions (measurement shots). |

| Orbital-Optimized Active Space Methods [31] | Reduces quantum resource demands by focusing computation on a correlated subset of orbitals. | Introduces a classical optimization loop; accuracy depends on active space selection. |

| Pauli Saving [31] | Reduces measurement cost and noise in subspace methods by intelligently grouping Hamiltonian terms. | Requires advanced classical pre-processing of the Hamiltonian. |

| Trapped-Ion Quantum Computers (e.g., Quantinuum H2) [28] [29] | Provides high-fidelity gates, all-to-all connectivity, and mid-circuit measurement for advanced algorithms. | Current qubit counts are still limited for large-scale problems. |

| Resistomycin | Resistomycin, CAS:20004-62-0, MF:C22H16O6, MW:376.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| RO8191 | RO8191, CAS:691868-88-9, MF:C14H5F6N5O, MW:373.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing the Strategic Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the core challenge and the strategic responses discussed in this guide, highlighting the critical decision points for researchers.

{{< svg >}}

The journey toward quantum utility in computational chemistry is a deliberate process of co-design, requiring careful balancing of algorithmic ambitions against hardware realities. No single approach—be it QEC, QEM, or robust optimization—currently holds the definitive answer. Instead, the future lies in their intelligent integration. As demonstrated by recent experiments, combining strategies like partial fault-tolerance with error mitigation [28] or multi-reference states with noise-aware optimizers [30] [27] provides a multi-layered defense against errors. This synergistic approach, leveraging advancements across the full stack of hardware, software, and algorithm design, is the most promising path to unlocking scalable, impactful, and noise-resilient quantum chemical simulations.

Advanced Algorithms and Encodings for Pharmaceutical-Ready Quantum Chemistry

This whitepaper analyzes the landscape of quantum algorithmic paradigms for chemical simulations, focusing on the resource tradeoffs essential for achieving noise resilience on near-term quantum hardware. We provide a technical comparison of established and emerging algorithms, detailed experimental protocols, and a visualization of the rapidly evolving field. The analysis is contextualized for research scientists and drug development professionals seeking to navigate the practical challenges of implementing quantum computing for molecular systems.

Accurately simulating quantum chemical systems is a fundamental challenge across physical, chemical, and materials sciences. While quantum computers are promising tools for this task, the algorithms must overcome the inherent noise present in modern Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. This has led to a critical examination of the resource tradeoffs—including qubit count, circuit depth, coherence time, and measurement overhead—associated with different algorithmic paradigms. The core challenge is to achieve "chemical accuracy," typically defined as an error of 1.6 mHa (milliHartree) or less in energy calculations, under realistic experimental constraints. This document frames the evolution from foundational algorithms like Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) and the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) to more recent hybrid solvers within this context of optimizing for noise resilience.

Foundational Algorithms and Their Resource Demands

Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE)

Theory and Mechanism: QPE is a cornerstone quantum algorithm for determining the eigenenergies of a Hamiltonian. It operates on a principle of interference and phase kickback. Given a unitary operator (U) (which encodes the system's Hamiltonian (H)) and an input state (|\psi\rangle) that has non-zero overlap with an eigenstate of (U), QPE estimates the corresponding phase (θ), where (U|\psi\rangle = e^{i2πθ}|\psi\rangle). For Hamiltonian simulation, (U) is often constructed via techniques like qubitization, which provides a superior encoding compared to simple Trotterized time evolution. Qubitization expresses the Hamiltonian (H) as a linear combination of unitaries, (H=\sumk αk Vk), and constructs a unitary operator (Q) whose eigenvalues are directly related to (arccos(Ej/λ)), where (Ej) are the eigenvalues of (H) and (λ = \sumk α_k) [32].

Resource Requirements: The resource requirements of QPE are substantial, placing it firmly in the fault-tolerant quantum computing regime.

- Qubits: Requires a significant number of ancillary qubits in addition to the system qubits.

- Circuit Depth: The circuits are inherently deep, requiring long coherence times.

- Operations: The number of calls to the unitary (Q) scales as (O(λ/ε)) to achieve an energy precision (ε) [32].

Table 1: Resource Estimates for a Fault-Tolerant QPE Calculation on a Specific Molecule [32]

| Molecule (LiPF₆) | Basis Set Size | Estimated Toffoli Gates | Estimated Runtime (100 MHz Clock) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 72 electrons | Thousands of plane waves | ~8 × 10⸠| ~8 seconds |

| 72 electrons | Millions of plane waves | ~1.3 × 10¹² | ~3.5 hours |

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE)

Theory and Mechanism: The VQE is a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed for NISQ devices. It functions as a "guessing game" where a parameterized quantum circuit (the ansatz) is iteratively optimized by a classical computer [33]. The quantum processor is used to prepare a trial state ( |ψ(θ)\rangle ) and measure the expectation value of the Hamiltonian, ( \langle H(θ)\rangle ). The classical optimizer then adjusts the parameters ( θ ) to minimize this expectation value, converging towards the ground-state energy.

Resource Requirements and Challenges: While VQE avoids the deep circuits of QPE, it faces other profound resource constraints related to the measurement problem and optimization difficulties.

- Measurement Overhead: The Hamiltonian must be decomposed into a sum of measurable terms, ( H = \sum{j=1}^M hj Pj ), where ( Pj ) are Pauli strings. The number of measurements ( M ) required to estimate ( \langle H\rangle ) with precision ( ε ) can be prohibitively large and scales rapidly with system size [32].

- Optimization Challenges: The optimization landscape of VQE is often plagued by barren plateaus, where the gradients of the cost function vanish exponentially with system size, making convergence difficult [34].