Navigating the Noise: A Practical Guide to Quantum Optimizer Selection for Chemical Computations

Selecting the right classical optimizer is a critical determinant of success for Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) simulations in drug discovery and materials science.

Navigating the Noise: A Practical Guide to Quantum Optimizer Selection for Chemical Computations

Abstract

Selecting the right classical optimizer is a critical determinant of success for Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) simulations in drug discovery and materials science. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and development professionals, exploring the foundational challenges of optimization in noisy, finite-shot environments. It details the performance of various optimizer classes—from gradient-based to evolutionary strategies—on real-world chemical problems like protein-ligand binding and molecular energy calculations. The content offers actionable troubleshooting strategies to overcome common pitfalls like false minima and the winner's curse and concludes with validated, comparative benchmarks to inform robust optimizer selection for near-term quantum applications in the life sciences.

The NISQ Challenge: Why Chemical Landscape Optimization is Noisy and Complex

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary hardware limitations of NISQ devices? NISQ devices are constrained by three interconnected factors: the number of qubits, their quality, and their stability. Current processors contain from 50 to a few hundred qubits, which is insufficient for full-scale quantum error correction [1] [2]. Qubits are "noisy," meaning they have high error rates and short coherence times, limiting the complexity and duration of computations that can be reliably performed [2] [3].

FAQ 2: What is decoherence and how does it affect my experiment? Decoherence is the process by which a qubit loses its quantum state through interaction with its environment. This is the fundamental cause of computational errors in NISQ devices [2]. It directly limits the coherence time—the maximum duration you have to execute quantum gates before the quantum information is irretrievably lost. If your circuit's execution time exceeds the coherence time, your results will be unreliable [2] [4].

FAQ 3: Which classical optimizers are most robust for VQEs in noisy environments? Benchmarking studies evaluating over fifty metaheuristic algorithms have identified a subset that performs well on noisy, rugged optimization landscapes. The most resilient optimizers are CMA-ES and iL-SHADE [5]. Other algorithms showing good robustness include Simulated Annealing (Cauchy), Harmony Search, and Symbiotic Organisms Search [5]. In contrast, widely used optimizers like PSO, GA, and standard DE variants tend to degrade sharply in the presence of noise [5].

FAQ 4: What is the "barren plateau" problem and how can I mitigate it? A barren plateau is a phenomenon where the gradients of the cost function vanish exponentially with an increase in the number of qubits [5]. This makes optimizing the parameters of your quantum circuit incredibly difficult. Mitigation strategies include using specifically crafted, problem-inspired circuit ansatze instead of overly generic ones, and employing noise-mitigation techniques to prevent noise-induced plateaus [5] [6].

FAQ 5: What is the practical limit on quantum circuit depth today? A practical rule of thumb is that current NISQ devices can execute a sequence of approximately 1,000 gates before accumulated errors render the result indistinguishable from random noise [2]. This is a hard physical limit that shapes all NISQ-era algorithm design, necessitating the use of "shallow" circuits.

Troubleshooting Guides

Scenario 1: Consistently High Energy Readings in VQE Calculation

Problem: Your Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) experiment is converging to an energy value significantly higher than the known ground state.

Investigation & Resolution:

Check Circuit Depth vs. Coherence Time:

Analyze the Optimization Landscape:

- Action: Visualize a small region of the parameter space around your result. Noisy landscapes that appear smooth in simulations can become distorted and rugged on real hardware, trapping optimizers [5].

- Fix: Switch to a noise-resilient, global search metaheuristic optimizer like CMA-ES instead of a local gradient-based method [5].

Verify Hamiltonian Transformation:

- Action: Double-check the procedure used to map your molecular electronic Hamiltonian to a qubit Hamiltonian (e.g., Jordan-Wigner, parity transformation).

- Fix: Ensure the mapping is correct and appropriate for your target molecule and qubit connectivity. An error here will lead the algorithm to minimize the energy of the wrong Hamiltonian [6].

Preventative Protocol:

- Always start by running your VQE workflow on a classical simulator with noise models to establish a baseline before using quantum hardware.

Scenario 2: Unreliable Results Despite Successful Calibration

Problem: Results from the same quantum circuit vary significantly between runs, even when the device calibration reports show good parameters.

Investigation & Resolution:

Implement Error Mitigation:

- Action: Apply error mitigation techniques like Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE). This involves intentionally running your circuit at amplified noise levels and extrapolating the results back to the zero-noise limit [3].

- Fix: Integrate ZNE into your measurement routine. Most modern quantum software development kits (SDKs) have built-in functions for this.

Check for Measurement Error Mitigation:

- Action: Run a measurement calibration routine to characterize the readout error for each qubit.

- Fix: Construct a measurement error mitigation matrix and apply it to your results in post-processing [3].

Verify Quantum Volume:

- Action: Check the reported Quantum Volume (QV) of the device. A higher QV indicates a more capable processor overall, even if the raw qubit count is the same [2].

- Fix: If possible, select a backend with the highest available QV for your experiment, as it is a holistic metric of qubit count, fidelity, and connectivity.

Preventative Protocol:

- Increase the number of measurement shots (

shotsparameter) to reduce statistical uncertainty, accepting that this increases resource cost and execution time.

Scenario 3: Optimizer Failure or Extreme Slow Convergence

Problem: The classical optimizer in your hybrid quantum-classical algorithm fails to converge or takes an impractically long time.

Investigation & Resolution:

Diagnose a Barren Plateau:

- Action: Plot the gradient norms for a sample of parameters. If they are exponentially small, you are likely in a barren plateau region [5].

- Fix: Consider using an adaptive ansatz algorithm like Greedy Gradient-Free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE), which builds the circuit one gate at a time and has demonstrated high robustness to noise and barren plateaus [7].

Switch Optimizer Class:

- Action: Identify the class of your current optimizer (e.g., gradient-based).

- Fix: As per benchmark studies, switch to a gradient-free, population-based metaheuristic algorithm. CMA-ES and iL-SHADE are top performers for noisy VQE problems [5].

Simplify the Ansatz:

Preventative Protocol:

- When designing your experiment, consult recent optimizer benchmarking studies for the specific problem class you are solving. Do not rely solely on optimizers known to perform well only in noiseless, simulated environments.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: NISQ Hardware Specifications & Error Budgets

This table summarizes typical physical resource constraints and error rates across leading NISQ platforms. Use it for experimental planning and hardware selection.

| Resource / Metric | Superconducting Qubits | Trapped Ions | Target for Fault Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Qubits | 50 - 1,000+ [3] | ~50 (high-fidelity) [1] | Millions [9] |

| Coherence Time (T2) | Microseconds to milliseconds | Tens to hundreds of milliseconds | Significantly longer than gate time |

| Single-Qubit Gate Fidelity | 99.9% [9] | > 99.5% (typical) | > 99.99% |

| Two-Qubit Gate Fidelity | 95% - 99% [2] [3] | > 99% (typical) | > 99.9% |

| Measurement Fidelity | ~95-99% [9] | ~99% (typical) | > 99.9% |

| Max Practical Circuit Depth | ~1,000 gates [2] | Varies, limited by gate speed & coherence | Effectively unlimited with error correction |

Table 2: Optimizer Performance in Noisy Landscapes

This table compares the performance of selected classical optimizers for VQE, based on benchmarking over 50 metaheuristics in noisy conditions [5].

| Optimizer | Class | Performance in Noise | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES | Evolutionary Strategy | Consistently Best | Adapts its search strategy to the landscape geometry. |

| iL-SHADE | Differential Evolution | Consistently Best | A state-of-the-art DE variant with parameter adaptation. |

| Simulated Annealing (Cauchy) | Physics-Inspired | Robust | Good at escaping local minima. |

| Harmony Search | Music-Inspired | Robust | Efficiently explores parameter space. |

| Particle Swarm (PSO) | Swarm Intelligence | Degrades Sharply | Performance drops significantly with noise. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Evolutionary | Degrades Sharply | Struggles with rugged, noisy landscapes. |

Workflow: Resilient VQE Experiment Setup

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz | A parameterized quantum circuit designed to minimize depth and maximize fidelity on a specific hardware architecture, respecting its native gates and connectivity [6]. |

| Error Mitigation Suite (e.g., ZNE) | Software-based post-processing techniques that improve result accuracy without the massive qubit overhead of full error correction. Essential for extracting a usable signal from noisy hardware [3]. |

| Metaheuristic Optimizers (CMA-ES, iL-SHADE) | Classical algorithms that perform global search in the parameter space. They are more robust to the noisy, rugged optimization landscapes produced by NISQ hardware than many gradient-based methods [5]. |

| Quantum Volume (QV) Benchmark | A holistic metric that evaluates the overall computational power of a quantum processor, integrating qubit count, connectivity, and gate fidelities. A better indicator of capability than qubit count alone [2]. |

| Greedy/Gradient-Free Algorithms (e.g., GGA-VQE) | Advanced VQE variants that build circuits iteratively with minimal quantum resource requirements. They have demonstrated high noise resilience and have been run successfully on real 25-qubit hardware [7]. |

The Impact of Finite-Shot Noise on Variational Energy Landscapes

Frequently Asked Questions

What is "finite-shot noise" and why does it matter for my VQE experiments? Finite-shot noise arises from the statistical uncertainty in estimating energy expectation values using a limited number of measurements (shots) on a quantum device. Instead of obtaining the exact expectation value ( C(\bm{\theta}) = \langle \psi(\bm{\theta}) | \hat{H} | \psi(\bm{\theta}) \rangle ), you get a noisy estimator ( \bar{C}(\bm{\theta}) = C(\bm{\theta}) + \epsilon{\text{sampling}} ), where ( \epsilon{\text{sampling}} ) is a zero-mean random variable with variance proportional to ( 1/N_{\text{shots}} ) [10]. This noise distorts the true energy landscape, creating spurious local minima and misleading your classical optimizer.

I keep finding energies below the true ground state. Is my calculation successful? Unfortunately, no. This is a classic statistical artifact known as the "winner's curse" or stochastic variational bound violation [10] [11]. When you take a finite number of shots, the lowest observed energy in a set of measurements is a biased estimator. Random fluctuations can make a computed energy appear lower than the true ground state, which physically is impossible under the variational principle. This can cause your optimizer to converge to a false minimum.

My gradient-based optimizer was working perfectly in noiseless simulations but fails on real hardware. Why? Gradient-based optimizers (like BFGS, SLSQP, and gradient descent) rely on accurate estimations of the cost function's curvature to find descent directions. Under finite-shot noise, the gradient signal can become comparable to or even smaller than the amplitude of the noise itself [10] [11]. When this happens, the calculated gradients become too unreliable for the optimizer to make progress, causing it to stagnate or diverge.

Which classical optimizers are most robust to this type of noise? Recent extensive benchmarking studies have identified adaptive metaheuristic algorithms as the most resilient. Specifically, the Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) and improved Success-History Based Parameter Adaptation for Differential Evolution (iL-SHADE) consistently outperform other methods in noisy VQE optimization [10] [5] [11]. Their population-based approach inherently averages out some of the stochastic noise.

Is there a way to correct for the "winner's curse" bias? Yes. When using population-based optimizers, a simple but effective strategy is to track the population mean energy instead of the best individual's energy [10] [11]. The population mean provides a less biased estimate of the true cost function. Alternatively, you can re-evaluate the energy of the purported "best" parameters with a very large number of shots before accepting it as your final result.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Optimizer Converges to a False Minimum

Symptoms:

- The reported final energy is inconsistently below the theoretical ground state upon re-evaluation.

- Large fluctuations in the energy trajectory during optimization.

- The solution does not correspond to a physically plausible molecular state.

Solutions:

- Apply Bias Correction: Implement population mean tracking. In your optimization loop, record and use the average energy of the entire population of candidate solutions to guide the search, rather than just the single best member [10] [11].

- Re-evaluate Elite Parameters: At the end of each optimization iteration, take the top candidate solutions and re-evaluate their energies with a significantly higher number of shots (e.g., 10x your standard amount). Use this more precise measurement to select the true best performer for the next generation.

- Switch Your Optimizer: If you are using a local, gradient-based method (e.g., BFGS, SLSQP), switch to a global, adaptive metaheuristic. The table below summarizes the performance of various optimizer classes.

| Optimizer Class | Examples | Performance under Finite-Shot Noise |

|---|---|---|

| Gradient-Based | BFGS, SLSQP, Gradient Descent | Prone to divergence and stagnation; performance degrades sharply [10] [5]. |

| Gradient-Free Local | COBYLA, SPSA | More robust than gradient-based methods, but can still get trapped in local spurious minima [10] [12]. |

| Metaheuristic (Non-Adaptive) | PSO, Standard GA, DE | Performance degrades significantly with noise and problem scale [5]. |

| Metaheuristic (Adaptive) | CMA-ES, iL-SHADE | Most resilient; consistently achieve the best performance by implicitly averaging noise [10] [5] [11]. |

Problem: Barren Plateaus and Vanishing Gradients

Symptoms:

- The gradients of the cost function with respect to the parameters are exceedingly close to zero.

- The optimizer fails to make any progress from the initial point, regardless of the parameter initialization.

Explanation: A Barren Plateau (BP) is a phenomenon where the gradient of the cost function vanishes exponentially with the number of qubits [5]. Finite-shot noise exacerbates this problem because the exponentially small gradient signal is drowned out by the constant-level sampling noise, making it impossible for gradient-based optimizers to find a descent direction [10] [5].

Solutions:

- Use Physically-Motivated Ansätze: Problem-inspired ansätze, like the (truncated) Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz (tVHA) or Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC), are less likely to exhibit barren plateaus compared to highly expressive, hardware-efficient ansätze [10].

- Adopt Gradient-Free Optimizers: Metaheuristic algorithms like CMA-ES do not rely on gradient information and are therefore not directly affected by vanishing gradients. They can navigate flat landscapes through a population-based global search [5].

Problem: High Resource Cost of Measurements

Symptoms:

- Optimization takes an impractically long time because a vast number of shots are needed to achieve stable convergence.

- A trade-off between measurement budget and solution accuracy is forced.

Solutions:

- Use Measurement-Frugal Optimizers: Implement adaptive shot strategies like the iCANS (individual Coupled Adaptive Number of Shots) optimizer. iCANS dynamically allocates more shots to gradient components that have a larger predicted influence on the parameter update, drastically reducing the total number of measurements required for convergence [13].

- Employ Quantum-Aware Optimizers: For specific, physically-motivated ansätze (e.g., those built from excitation operators), use algorithms like ExcitationSolve [12]. This gradient-free optimizer determines the global optimum along a parameter direction by fitting the known analytical form of the 1D energy landscape, which requires only a handful of energy evaluations per parameter.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Optimizers

To rigorously evaluate the performance of different classical optimizers under finite-shot noise, follow this established methodological framework [10] [5].

1. System and Ansatz Selection:

- Benchmark Molecules: Start with small, well-understood systems like the Hydrogen molecule (H₂), a linear Hydrogen chain (H₄), and Lithium Hydride (LiH). These can be studied in both full and active space configurations to manage complexity.

- Ansätze: Test across different ansatz types to generalize your findings:

- Problem-Inspired: Truncated Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz (tVHA), Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCCSD).

- Hardware-Efficient: The

TwoLocalcircuit and other hardware-native ansätze.

- Extended Validation: Confirm results on condensed matter models like the 1D Ising model and the Fermi-Hubbard model, which exhibit different landscape features.

2. Noise and Cost Evaluation Setup:

- Noise Modeling: Simulate the effect of finite shots by adding zero-mean Gaussian noise to the exact energy expectation value. The standard deviation of the noise should be set to ( \sigma / \sqrt{N_{\text{shots}}} ), where ( \sigma ) is the standard deviation of the Hamiltonian [10].

- Cost Evaluation: The cost function is the (noisy) expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian, ( \langle H \rangle ), estimated from a finite number of measurements.

3. Optimizer Comparison:

- Test a Diverse Set: Benchmark a wide range of optimizers from different classes:

- Gradient-Based: SLSQP, BFGS, Gradient Descent.

- Gradient-Free Local: COBYLA, SPSA.

- Metaheuristic: CMA-ES, iL-SHADE, PSO, Simulated Annealing.

- Performance Metrics: For each optimizer, track:

- Final achieved energy error (relative to FCI or exact diagonalization).

- Number of cost function evaluations to converge.

- Consistency of convergence across multiple random initializations.

The workflow for such a benchmarking experiment can be summarized as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational "reagents" used in studying finite-shot noise, as identified in the research.

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| tVHA Ansatz | A problem-inspired, physically-motivated quantum circuit ansatz; helps mitigate barren plateaus [10]. |

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA) | A problem-agnostic ansatz built from native hardware gates; used as a contrast to physical ansätze to study landscape deformation [10]. |

| CMA-ES Optimizer | An adaptive metaheuristic optimizer; identified as one of the most robust choices for noisy VQE landscapes [10] [5]. |

| iL-SHADE Optimizer | An advanced adaptive Differential Evolution variant; consistently top performer in noisy optimization [10] [5]. |

| iCANS Optimizer | A gradient-based optimizer that adaptively allocates measurement shots to be resource-frugal [13]. |

| ExcitationSolve Optimizer | A quantum-aware, gradient-free optimizer for ansätze with excitation operators; finds global optimum per parameter efficiently [12]. |

| H₂, H₄, LiH Molecules | Benchmark quantum chemistry systems for initial algorithm testing and validation [10]. |

| Ising & Fermi-Hubbard Models | Condensed matter models used to test optimizer scalability and generalizability to rugged landscapes [5]. |

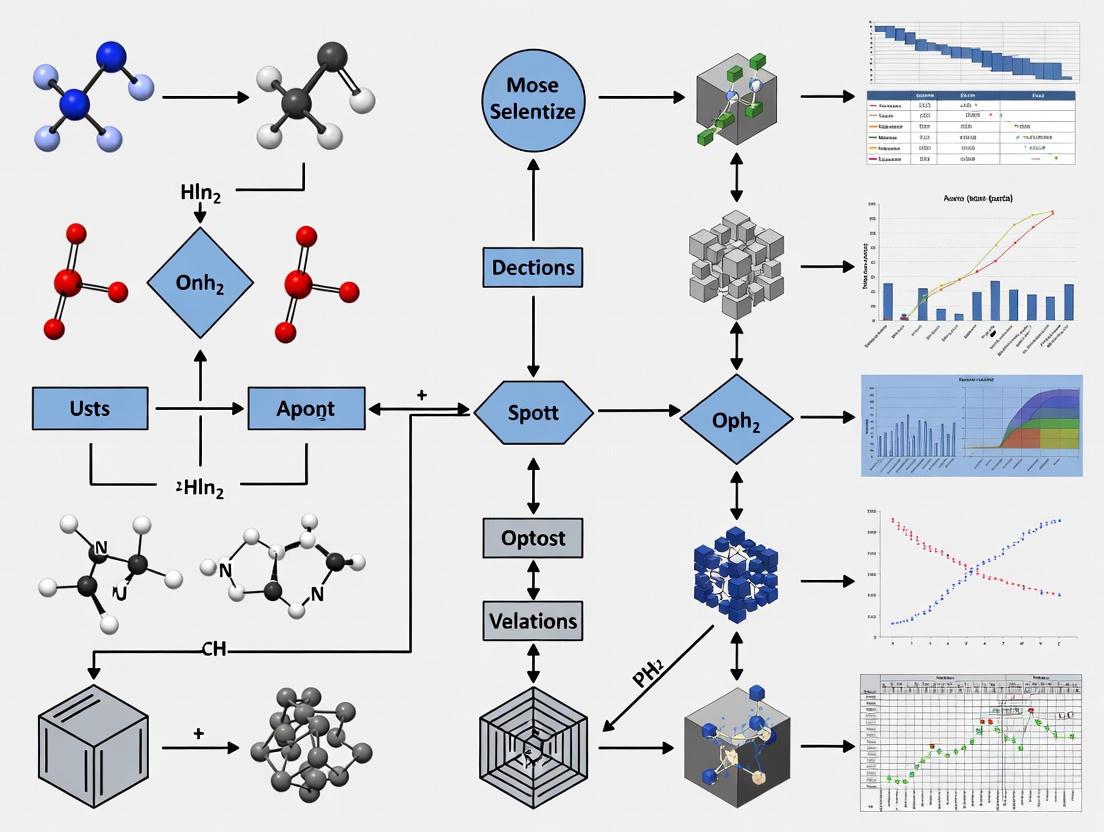

The logical relationship between the core components of a robust VQE optimization strategy under noise is shown below.

This guide addresses the primary obstacles in optimizing Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) for chemical computations on noisy hardware. It provides diagnostic and mitigation strategies for researchers confronting Barren Plateaus, the Winner's Curse, and False Minima.

FAQs

FAQ 1: What are the distinct types of Barren Plateaus, and how do I diagnose them? Barren Plateaus (BPs) manifest in two primary forms, both leading to exponentially vanishing gradients as the number of qubits increases, but with different root causes.

- Noise-Induced Barren Plateaus (NIBPs): Caused by hardware noise and decoherence. The gradient vanishes exponentially with circuit depth and the number of qubits. This occurs even for circuits that might otherwise be trainable in a noiseless setting [14].

- Algorithm-Induced Barren Plateaus: Caused by the algorithm's own structure, such as using deep, randomly initialized parameterized circuits or global cost functions, which lead to a flat training landscape [14] [15].

Diagnosis: If you observe an exponential decay in gradient magnitudes with increasing qubit count, even after improving parameter initialization, you are likely facing a Barren Plateau. NIBPs will be particularly pronounced when running on actual hardware or simulations with realistic noise models.

FAQ 2: My optimizer converges to a result that seems better than the theoretical minimum. What is happening?

This is a classic symptom of the Winner's Curse, a statistical bias that occurs under finite sampling noise. When you use a limited number of measurement shots (N_shots), your estimate of the cost function becomes a random variable. The "best" observed value in a set of samples is often an underestimation of the true cost due to random fluctuations, creating an illusion of performance that violates the variational principle [10] [11].

FAQ 3: Why does my optimization get stuck in poor local minima, especially when using more shots? You are likely encountering False Minima. Sampling noise distorts the true cost landscape, transforming smooth basins into rugged, multimodal surfaces. These false minima are spurious local minima introduced by noise, not the underlying physics of the problem. Gradient-based optimizers are particularly susceptible to getting trapped here when the curvature of the landscape is of the same order of magnitude as the noise amplitude [10].

FAQ 4: Do gradient-free optimizers solve the Barren Plateau problem? No. While it was initially hypothesized that gradient-free methods might bypass BP issues, it has been rigorously proven that they do not. In a Barren Plateau, the cost function differences between any two parameter points are exponentially suppressed. Consequently, any gradient-free optimizer requires exponential precision (and hence, an exponential number of shots) to discern a direction of improvement, just like gradient-based methods [15].

FAQ 5: What are the most resilient classical optimizers for noisy VQAs? Recent benchmarks indicate that adaptive metaheuristic optimizers show superior resilience to the noisy, distorted landscapes of VQAs.

- Top Performers: CMA-ES (Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy) and iL-SHADE (Improved Success-History Based Parameter Adaptation for Differential Evolution) consistently outperform other methods [10] [11].

- Reason for Success: As population-based methods, they implicitly average out sampling noise across the population, which provides a more stable signal for the optimization direction and helps correct for the Winner's Curse bias [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating Barren Plateaus

Symptoms:

- Vanishing gradients (or cost differences) that scale exponentially with the number of qubits.

- Inability for the classical optimizer to find a direction of improvement, leading to random walking on a flat landscape.

Resolution Strategies:

- Reduce Circuit Depth: Since NIBPs worsen with circuit depth, the most direct strategy is to design and use shallower ansatzes [14].

- Use Structured Ansatzes: Prefer problem-inspired ansatzes (like UCCSD or the Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz) over completely random, hardware-efficient ansatzes, as they are less prone to BPs [16].

- Employ Local Cost Functions: Define cost functions as a sum of local observables instead of a single global observable, which can help avoid algorithm-induced BPs [14].

- Investigate Advanced Optimizers: Some hybrid classical-quantum strategies, such as those incorporating classical PID controllers, have shown promise in improving convergence efficiency on noisy landscapes, though this remains an active research area [17].

Issue 2: Correcting for the Winner's Curse and False Minima

Symptoms:

- The best-reported cost from an optimization run is unrealistically low (violating the variational principle).

- The optimizer converges to different "minima" on different runs with the same parameters.

- Re-evaluation of the optimal parameters with a high number of shots reveals a much worse cost.

Resolution Strategies:

- Track Population Mean: When using population-based optimizers (e.g., CMA-ES), track the mean cost of the population instead of the best individual's cost. The population mean provides a less biased estimator of the true performance [10] [11].

- Re-evaluate Elite Candidates: Always re-evaluate the final best parameters (

θ_best) with a very large number of shots to get a precise, unbiased estimate of the true cost and confirm the solution's validity [11]. - Adaptive Metaheuristics: Use resilient optimizers like CMA-ES or iL-SHADE, which are designed to handle noisy landscapes and reduce the risk of being deceived by false minima [10].

- Careful Parameter Initialization: Strategies like initializing parameters to zero have been shown to lead to more stable and faster convergence for certain chemical ansatzes, providing a better starting point [16].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Optimizer Resilience under Sampling Noise

Objective: Systematically evaluate and compare the performance of classical optimizers under realistic finite-shot noise conditions.

Materials: Table: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Molecular Hamiltonians (e.g., H₂, H₄, LiH) | Serves as the target cost function (ground state energy) for the VQE [10] [16]. |

| Parameterized Quantum Circuit (Ansatz) | The variational wavefunction ansatz (e.g., UCCSD, tVHA, Hardware-Efficient) [10] [16]. |

| Classical Optimizers | The algorithms being tested (e.g., CMA-ES, iL-SHADE, SLSQP, BFGS, ADAM) [10]. |

| Quantum Simulator/ Hardware | The platform for cost function evaluation. A simulator allows controlled noise introduction [10]. |

Methodology:

- Problem Setup: Select a benchmark problem (e.g., finding the ground state of an H₄ chain) and an ansatz.

- Noise Introduction: For each cost function evaluation in the optimization loop, use a fixed, finite number of measurement shots (

N_shots), introducing sampling noise. - Optimizer Configuration: Run multiple independent optimizations for each candidate optimizer (CMA-ES, iL-SHADE, BFGS, etc.) from the same set of initial parameters.

- Data Collection: For each run, record:

- The best-reported cost at each iteration (the "noisy" best).

- The true cost at each iteration (calculated with a very high number of shots for analysis purposes).

- The final parameters.

- Analysis:

- Success Rate: Calculate the percentage of runs that converged to a value near the true ground state energy.

- Convergence Speed: Analyze the number of iterations or function evaluations required to converge.

- Bias Analysis: Compare the final "noisy" best cost with the "true" cost for the same parameters to quantify the Winner's Curse.

This protocol directly visualizes how optimizers navigate a noisy landscape. The workflow is summarized below.

Protocol 2: Mitigating the Winner's Curse via Population Mean Tracking

Objective: Implement and validate a bias-correction strategy for population-based optimizers.

Methodology:

- Standard Approach: Run a population-based optimizer (e.g., CMA-ES). The standard procedure is to select the individual with the lowest noisy cost as the best candidate for the next generation.

- Bias-Correction Approach: In a parallel run, instead of using the noisy best individual, calculate and use the mean of the population's parameters (or track the mean cost) to guide the optimization.

- Validation: After convergence, re-evaluate the final parameters from both approaches with a high number of shots.

- Comparison: The population-mean approach should yield a final parameter set whose true cost is closer to the noisy-reported cost, demonstrating reduced bias from the Winner's Curse [10].

The following diagram illustrates the key obstacle of the Winner's Curse and the logic behind the mitigation strategy.

Optimizer Performance Reference

The following table summarizes key findings from recent studies on optimizer performance under noisy conditions, providing a guide for initial optimizer selection.

Table: Optimizer Performance under Sampling Noise

| Optimizer | Type | Key Strengths | Key Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES [10] [11] | Adaptive Metaheuristic | Highly resilient to noise; implicit averaging mitigates Winner's Curse. | Can have slower convergence speed. |

| iL-SHADE [10] [11] | Adaptive Metaheuristic | Effective on noisy, rugged landscapes; good global search. | |

| ADAM [16] | Gradient-based | Can perform well with good initialization in some problems. | Struggles when gradient precision is lost to noise; prone to false minima [10]. |

| BFGS / SLSQP [10] | Gradient-based | Fast convergence in low-noise, convex landscapes. | Diverges or stagnates when cost curvature is comparable to noise amplitude [10]. |

The Critical Role of the Classical Optimizer in VQE Workflows

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why does my VQE calculation fail to converge to the correct ground-state energy? Your issue likely stems from the optimizer being trapped by noise-induced local minima or barren plateaus. On noisy hardware, the smooth, convex optimization landscape observed in noiseless simulations becomes distorted and rugged, which causes widely used optimizers like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) or standard Gradient Descent to fail. It is recommended to switch to more robust metaheuristic algorithms such as CMA-ES or iL-SHADE, which are specifically designed to handle such complex, noisy landscapes [5].

2. Which classical optimizer should I use for a noisy, real quantum device? Based on large-scale benchmarking of over fifty algorithms, the most resilient optimizers under noisy conditions are CMA-ES and iL-SHADE. Other algorithms that demonstrate good robustness include Simulated Annealing (Cauchy), Harmony Search, and Symbiotic Organisms Search. You should avoid standard Differential Evolution (DE) variants, PSO, and Genetic Algorithms (GA), as their performance degrades sharply in the presence of noise [5].

3. How does the choice of optimizer affect the overall runtime and measurement cost of my VQE experiment? The optimizer choice is the primary determinant of the number of measurements (shots) required. Algorithms that are susceptible to noise or barren plateaus need an exponentially large number of shots to resolve tiny gradients. Using a noise-resilient metaheuristic optimizer can drastically reduce the total measurement overhead, making the VQE workflow feasible on near-term devices [5].

4. My VQE results are inconsistent across multiple runs. Is this an optimizer problem? Yes, inconsistency is a classic symptom of an optimizer struggling with a noisy and stochastic cost landscape. The statistical uncertainty (shot noise) from a finite number of measurements creates a rugged landscape that can trap less robust optimizers in different local minima on different runs. Employing optimizers known for stability in noisy environments, like iL-SHADE, will improve consistency [5].

5. For a chemical system like a small aluminum cluster, what optimizer and ansatz combination is recommended? Benchmarking studies on aluminum clusters (Al-, Al₂, Al₃-) have successfully used the Sequential Least Squares Programming (SLSQP) optimizer in conjunction with an EfficientSU2 ansatz. This setup, executed on a statevector simulator with a STO-3G basis set, has achieved results with percent errors consistently below 0.02% against classical benchmarks [18] [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Persistent High Energy Due to Barren Plateaus

- Symptoms: The optimization progress stalls almost immediately, with the energy value remaining nearly constant and gradients vanishing across many iterations, regardless of the initial parameters.

- Diagnosis: This indicates the presence of a barren plateau, where the gradient variance vanishes exponentially with the number of qubits.

- Recommended Actions:

- Switch Optimizers: Immediately move from local, gradient-based optimizers to global, population-based metaheuristics. The recommended choices are CMA-ES or iL-SHADE [5].

- Verify Problem Formulation: Check if your Hamiltonian and ansatz are overly expressive, as this can induce barren plateaus.

- Use Error Mitigation: Incorporate error mitigation techniques like zero-noise extrapolation to partially counteract the effects of noise that can exacerbate plateaus [9].

Issue 2: Inaccurate Ground-State Energy for Molecules

- Symptoms: The VQE calculation converges, but the final energy value shows a significant error when compared to classical computational benchmarks like Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) or data from the CCCBDB.

- Diagnosis: The inaccuracy can originate from a suboptimal combination of optimizer settings, ansatz, and basis set.

- Recommended Actions:

- Systematically Benchmark Parameters: Follow the protocol below to test different configurations [18] [19].

- Select a Robust Optimizer: From your benchmarking results, choose the best-performing optimizer, which is often SLSQP or COBYLA for small molecules in noiseless simulations [20] [19].

- Adjust Basis Set: If computationally feasible, try a higher-level basis set (e.g., from STO-3G to 6-31G) to improve accuracy, as this has been shown to yield results closer to classical benchmarks [18] [19].

Table: Key Parameters for VQE Benchmarking on Chemical Systems

| Parameter Category | Options to Test | Impact on Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Optimizer | SLSQP, COBYLA, CMA-ES, L-BFGS-B, iL-SHADE | Directly affects convergence efficiency, accuracy, and robustness to noise [18] [5]. |

| Circuit Ansatz | EfficientSU2, UCCSD, Hardware-Efficient | Determines the expressibility of the wavefunction and the circuit depth, which influences noise susceptibility [19]. |

| Basis Set | STO-3G, 6-31G, cc-pVDZ | Higher-level sets improve accuracy but increase qubit requirements and computational cost [18] [19]. |

| Simulator/Noise Model | Statevector, QASM Simulator (with/without IBM noise models) | Critical for evaluating performance under realistic, noisy conditions versus ideal ones [18] [19]. |

Issue 3: Poor Convergence on Real Noisy Quantum Hardware

- Symptoms: The algorithm converges to a poor solution or fails to converge at all when run on real hardware, despite working well on noiseless simulators.

- Diagnosis: The optimizer is unable to navigate the rugged energy landscape created by device noise and measurement uncertainty.

- Recommended Actions:

- Choose a Noise-Resilient Optimizer: Your primary strategy should be to use an optimizer from the top-performing tier identified in noisy benchmarking, specifically CMA-ES or iL-SHADE [5].

- Employ Error Mitigation: Integrate techniques like probabilistic error cancellation to obtain more accurate expectation values for the optimizer to use [9].

- Warm-Start the Optimization: If possible, use a solution from a classical approximation or a smaller problem as an initial point for the optimizer to refine.

Table: Metaheuristic Optimizer Performance in Noisy VQE Landscapes

| Optimizer | Performance in Noise | Key Characteristic | Best-Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES | Excellent | Covariance matrix adaptation; very robust | Noisy, rugged landscapes where gradient information is unreliable [5]. |

| iL-SHADE | Excellent | Advanced differential evolution variant with history-based parameter adaptation | High-dimensional, multimodal problems with noise [5]. |

| Simulated Annealing (Cauchy) | Good | Physics-inspired; allows "uphill" moves to escape local minima | Finding good approximate solutions in complex landscapes [5]. |

| Harmony Search | Good | Musically inspired; balances exploration and exploitation | |

| Particle Swarm (PSO) | Poor | Performance degrades sharply with noise | Not recommended for noisy VQE [5]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Poor | Performance degrades sharply with noise | Not recommended for noisy VQE [5]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Benchmarking of Optimizers for a Chemical System

This protocol is adapted from BenchQC studies on aluminum clusters [18] [19].

- System Preparation: Define your molecular system (e.g., Al₂) and generate its geometry.

- Active Space Selection: Use a quantum-DFT embedding framework to select an active space (e.g., 3 orbitals with 4 electrons).

- Hamiltonian Generation: Perform a single-point calculation using a quantum chemistry package (e.g., PySCF) to generate the second-quantized Hamiltonian. Map it to qubits using the Jordan-Wigner transformation.

- Parameter Variation: Run independent VQE calculations, each time varying one key parameter while keeping others at a tested default:

- Classical Optimizer: Test SLSQP, COBYLA, CMA-ES, etc.

- Ansatz: Test EfficientSU2, UCCSD, etc.

- Basis Set: Test STO-3G, 6-31G, etc.

- Execution and Analysis: Execute the VQE workflow on a statevector simulator (for a baseline) and a noisy simulator (for realism). Record the final energy, convergence speed, and number of function evaluations. Compare the results against a classical benchmark from NumPy (exact diagonalization) or the CCCBDB.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Optimizer Robustness under Noise

This protocol is based on the methodology used to benchmark over fifty metaheuristics [5].

- Model Selection: Choose a benchmark model with a known challenging landscape, such as the 1D Ising model or the Fermi-Hubbard model.

- Noise Introduction: Use a finite number of measurement shots (e.g., 1000 shots per expectation value estimation) to introduce realistic sampling noise into the cost function. For more realism, incorporate a hardware-specific noise model.

- Optimizer Testing: Run a wide array of optimizers (CMA-ES, iL-SHADE, PSO, GA, etc.) from the same set of initial parameters.

- Performance Metrics: For each optimizer, track:

- The best energy value found.

- The convergence trajectory (energy vs. function evaluations).

- The consistency across multiple runs (to assess stability).

- Ranking: Rank the optimizers based on their ability to consistently find the global minimum or a high-quality approximation thereof in the noisy environment.

Workflow and Logic Diagrams

VQE Optimizer Troubleshooting Logic

Problem-Solution Map for Noisy VQE Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for a VQE Workflow in Quantum Chemistry

| Item / 'Reagent' | Function / 'Role in Reaction' | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Optimizer | The catalyst that drives the parameter search towards the ground state; its choice critically determines efficiency and success. | CMA-ES/iL-SHADE: For noisy hardware. SLSQP/COBYLA: For small, noiseless simulations [5] [20]. |

| Parametrized Quantum Circuit (Ansatz) | The 'scaffold' that defines the space of possible quantum states explored by the algorithm. | EfficientSU2: Hardware-efficient, general-purpose. UCCSD: Chemistry-inspired, more accurate but deeper [19]. |

| Basis Set | The set of basis functions used to describe molecular orbitals; affects the Hamiltonian's form and qubit count. | STO-3G: Minimal, fast. 6-31G, cc-pVDZ: Higher accuracy, more expensive [18] [19]. |

| Noise Model / Error Mitigation | Simulates device imperfections or techniques to counteract them, providing more realistic/accurate expectation values. | IBM Device Noise Model: For realistic simulation. Zero-Noise Extrapolation: A common error mitigation technique [9] [19]. |

| Classical Benchmark | The 'control' or 'reference' against which the quantum result is validated for accuracy. | NumPy Eigensolver: Exact diagonalization. CCCBDB: Database of classical computational chemistry results [18] [19]. |

Optimizer Toolkit: From Gradient Descent to Evolutionary Strategies in Chemical VQE

This technical support center is designed for researchers and scientists working on the frontier of quantum chemistry, particularly in selecting and troubleshooting optimizers for noisy chemical computations. The selection of an appropriate classical optimizer is a critical determinant of success for variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) used in simulating molecular systems. The content below provides a structured guide to navigate the challenges associated with different optimizer families in this complex landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) experiment is converging to different energy values on each run. What is the most likely cause and how can I address it?

A: This is a classic symptom of convergence to local minima, a common challenge on noisy, non-convex landscapes. Your current optimizer is likely sensitive to initial parameters.

- Primary Troubleshooting Step: Switch to a metaheuristic optimizer known for global exploration capabilities. The Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) has been empirically shown to deliver superior performance in such scenarios by effectively navigating past local optima [21].

- Alternative Approach: Implement a hybrid strategy. Begin with a global metaheuristic like CMA-ES or a Cooperative Metaheuristic Algorithm (CMA) to locate a promising region of the parameter space, then refine the solution using a faster, gradient-based method [22].

Q2: The optimization performance of my quantum circuit degrades significantly as I increase the number of parameters (e.g., for more complex molecules or deeper circuits). Which optimizer family scales best with problem dimension?

A: Scalability is a major concern. Gradient-free and metaheuristic methods often face challenges in high-dimensional spaces, but some are designed to handle them.

- Recommended Solution: For high-dimensional regimes, such as those involving complex control pulses with many parameters, CMA-ES is recommended due to its superior dimension scaling compared to other algorithms like Nelder-Mead [21].

- Advanced Strategy: Consider a hybrid algorithm like Particle Swarm-guided Bald Eagle Search (PS-BES), which incorporates techniques like Lévy flights to maintain a robust search strategy and avoid local minima traps in large search spaces [23].

Q3: How can I design my optimization workflow to be more resistant to the inherent noise in near-term quantum devices?

A: Noise resistance is a key criterion for optimizer selection in the NISQ era.

- Algorithm Selection: Prioritize optimizers known for their noise resistance. Evolution Strategies (ES) and CMA-ES are generally robust to noisy fitness evaluations [21] [24].

- Noise-Adaptive Frameworks: Explore Noise-Adaptive Quantum Algorithms (NAQAs). These methods do not suppress noise but instead exploit it by aggregating information from multiple noisy outputs to adapt the optimization problem itself, guiding the system toward improved solutions [25]. The core steps involve sampling, problem adaptation, and re-optimization.

Q4: I am constrained by limited computational resources. Are there optimizers that can reduce the cost of my experiments?

A: Yes, the choice of optimizer can significantly impact computational overhead.

- Gradient-Free Advantage: Gradient-free methods, such as Evolutionary Algorithms, avoid the substantial memory and computational costs associated with storing and computing gradients [24]. This can reduce GPU memory overhead and computational cost.

- Batching for Efficiency: To maximize valuable quantum device uptime, use optimizers that support batching. This allows the algorithm to test multiple candidate parameter sets in a single iteration, uploading a batch of waveforms to the quantum hardware and speeding up the experimental execution time [21].

Optimizer Benchmarking and Selection Tables

The following tables summarize key performance metrics for different optimizer families, based on recent benchmarking studies, to aid in the selection process.

Table 1: Optimizer Family Characteristics and Benchmarking Criteria

| Optimizer Family | Key Characteristics | Best Suited For | Common Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-Based | Uses gradient information for efficient local convergence; requires differentiable objectives. | Smooth, convex landscapes; problems where accurate gradients can be computed. | Gets stuck in local minima; high memory usage for gradients and optimizer states [24]. |

| Gradient-Free | Does not require gradient information; treats the objective function as a black box. | Non-differentiable, noisy, or non-convex problems. | Slower convergence; can require more function evaluations than gradient-based methods. |

| Metaheuristics | High-level, inspiration-based algorithms (e.g., from nature) for global optimization. | Complex landscapes with many local minima; global search problems. | Can be computationally expensive; requires careful hyperparameter tuning [21] [26]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Benchmarking of Select Algorithms for Quantum Calibration [21]

| Algorithm | Noise Resistance | Local Optima Escape | Dimension Scaling | Convergence Speed | Batching Support | Ease of Setup (Hyperparameters) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES | High | Strong | Excellent (Recommended for high dimensions) | Moderate to Fast | Supported | Moderate (Hyperparameters are crucial) [21] |

| Nelder-Mead | Moderate | Weak | Poor (Low-dimensional settings) | Fast (in low dimensions) | Not Typically Supported | Easy (Few hyperparameters) |

| Cooperative MA (CMA) [22] | High | Strong (via SES technique) | Good | Fast (after setup) | Supported | Complex (Hybrid algorithm) |

| PS-BES [23] | High | Strong (via ARS technique) | Good | Fast | Supported | Complex (Hybrid algorithm) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Optimizer Performance on a Noisy Quantum Simulator

This protocol provides a methodology for comparing the performance of different optimizers in a controlled, simulated environment that mimics real-world experimental conditions [21].

- Objective: Quantify the performance of candidate optimizers (e.g., CMA-ES, Nelder-Mead, Adam) based on convergence budget, success probability, and final solution quality.

- Setup:

- Simulation Environment: Use a quantum simulator (e.g., Qiskit, Cirq) that incorporates realistic noise models (amplitude damping, phase damping, gate errors) [27].

- Test Problem: Define a target operation, such as a specific quantum gate (e.g., a Hadamard or CNOT gate) or a simple molecular Hamiltonian (e.g., H₂) for VQE.

- Loss Function: Implement a fidelity measure (e.g., state fidelity, process fidelity) or a Hamiltonian expectation value as the loss function to be minimized. This function will inherently include sampling noise.

- Execution:

- For each optimizer, run the optimization from the same set of initial parameters multiple times (e.g., 50-100 runs) to account for stochasticity.

- For each run, record the loss function value versus the number of iterations (or function evaluations), the total number of evaluations until convergence, and the final achieved loss.

- Analysis:

- Convergence Budget/Speed: Plot the average loss vs. function evaluations across all runs for each optimizer.

- Success Probability: Calculate the percentage of runs that converge to a loss value below a predefined threshold (e.g., fidelity > 0.99).

- Solution Quality: Compare the average and best final loss values achieved by each optimizer.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Noise-Adaptive Optimization (NAQA) Workflow

This protocol outlines the steps for a noise-adaptive workflow that can be layered on top of a base quantum optimization algorithm like QAOA [25].

- Objective: Improve solution quality for a combinatorial optimization problem on noisy hardware by exploiting information from multiple noisy samples.

- Setup:

- Base Algorithm: Choose a base quantum algorithm, such as the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA).

- Problem: Define the problem, for instance, a Max-Cut problem on a graph.

- Execution:

- Sample Generation: Run the base quantum program to obtain a sample set of bitstrings (potential solutions).

- Problem Adaptation: Analyze the sample set to adjust the original optimization problem. Two common techniques are:

- Attractor State Identification: Find a frequently occurring "attractor" state and apply a bit-flip gauge transformation to the cost Hamiltonian to make this state the new ground state [25] [22].

- Variable Fixing: Analyze correlations across samples to identify variables (qubits) that have a strong consensus value, and fix their values to reduce the problem size [25] [23].

- Re-optimization: Run the base quantum algorithm again on the newly adapted (transformed or reduced) optimization problem.

- Analysis: Iterate the process (Sample-Adapt-Re-optimize) until solution quality stops improving. Compare the final approximation ratio or best solution found against a single run of the base algorithm.

Workflow and Algorithm Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Algorithmic Tools

| Tool / Solution | Type | Function in Experiment | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qiskit SDK | Quantum Software Development Kit | Used for building, simulating, and running quantum circuits; includes noise models and built-in optimizers [27]. | IBM's open-source SDK; high-performing for advantage workloads. |

| CMA-ES Implementation | Optimization Algorithm | A gradient-free, metaheuristic optimizer for robust global optimization on noisy, high-dimensional landscapes [21]. | Recommended for automated calibration of quantum devices. |

| ConFIG Method | Gradient-Based Multi-Loss Optimizer | Resolves conflicts between multiple loss terms (e.g., different physical constraints) during neural network training [28]. | Useful for Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) in quantum chemistry. |

| Noise-Adaptive Quantum Algorithms (NAQAs) | Algorithmic Framework | A modular framework that exploits noisy quantum outputs to steer the optimization toward better solutions [25]. | For improving QAOA and other algorithms on near-term hardware. |

| Cooperative Metaheuristic Algorithm (CMA) | Hybrid Optimization Algorithm | Balances exploration and exploitation by dividing the population into cooperative subpopulations using a Search-Escape-Synchronize technique [22]. | For complex global optimization problems in engineering and design. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Premature Convergence in Noisy VQE Optimization

Problem: The classical optimizer converges to a parameter set that yields an energy below the theoretically possible ground state (violating the variational principle) or gets trapped in a local minimum.

Explanation: This is a classic symptom of the "winner's curse" or stochastic variational bound violation [10] [11]. In noisy environments, the finite number of measurement shots (N_shots) leads to statistical fluctuations in the energy estimation. The optimizer can be misled by a randomly low energy reading, mistaking a spurious minimum for the true global optimum [10].

Solution:

- Switch to a Resilient Optimizer: Replace standard optimizers (like basic PSO or GA) with adaptive metaheuristics like CMA-ES or iL-SHADE [5] [10].

- Implement Population Mean Tracking: For population-based optimizers, do not trust the single "best" individual in a generation. Instead, track the population mean of the cost function over iterations. This approach averages out noise and provides a less biased estimate of true performance, correcting for the "winner's curse" [10] [11].

- Re-evaluate Elite Parameters: Periodically re-measure the energy of the current best parameters with a very large number of shots to get a more accurate estimate and confirm if the improvement is genuine or noise-induced [11].

Guide 2: Addressing Barren Plateaus and Rugged Landscapes

Problem: Optimizer performance degrades sharply as the number of qubits or parameters increases. The algorithm appears to stall, making no progress despite numerous iterations.

Explanation: This is likely the barren plateau phenomenon [5] [10]. In high-dimensional parameter spaces, gradients of the cost function can vanish exponentially with the number of qubits. Furthermore, the smooth, convex landscape present in noiseless simulations becomes a distorted and rugged surface under finite-shot sampling noise, creating many local minima that trap local optimizers [5].

Solution:

- Employ Global Metaheuristics: Abandon local, gradient-based methods (like BFGS or SLSQP) which fail in this regime [5] [10]. Use global search strategies like CMA-ES and iL-SHADE, which are less reliant on local gradient information and are better at navigating multimodal landscapes [5].

- Leverage Landscape-Aware Grouping (LAG): For very high-dimensional problems (e.g., >100 parameters), consider a Cooperative Coevolutionary approach with a LAG method. This technique groups interacting variables by analyzing their convergence behavior, enabling more effective problem decomposition even in noisy environments [29].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are CMA-ES and iL-SHADE particularly recommended for noisy VQE landscapes?

A: Extensive benchmarking of over fifty metaheuristics identified CMA-ES and iL-SHADE as consistently top performers [5]. Their resilience stems from adaptive mechanisms that implicitly average out noise. CMA-ES dynamically adjusts its search distribution and step size based on the success of past generations, making it robust to noisy fitness evaluations [10] [29]. iL-SHADE, an advanced Differential Evolution variant, similarly adapts its parameters and uses a linear population size reduction, which helps to refine the search as optimization progresses [5] [10].

Q2: My gradient-based optimizer (SLSQP, BFGS) worked well in noiseless simulation. Why does it fail on real quantum hardware?

A: Gradient-based methods rely on accurate estimates of the cost function's curvature to find descent directions [10]. Under finite-shot noise, the landscape becomes rugged, and the signal of the true gradient can become comparable to or smaller than the amplitude of the noise [5] [11]. This distorts the gradient information, causing these methods to diverge or stagnate. Metaheuristics do not compute gradients and are therefore less susceptible to this issue.

Q3: Besides optimizer choice, what other strategies can improve VQE reliability under noise?

A: A co-design of the optimization strategy and the quantum circuit is crucial.

- Ansatz Selection: Use physically motivated, problem-inspired ansatze (like tVHA) where possible, as they can have more favorable landscape properties than generic hardware-efficient ansatze (HEA) [10].

- Error Mitigation: Incorporate techniques like Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) or symmetry verification to reduce the impact of hardware noise on the measured expectation values [3].

- Ensemble Methods: Running multiple optimization trajectories with different initializations can improve accuracy and robustness [11].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Benchmarking Methodology for Optimizer Performance

The superior performance of CMA-ES and iL-SHADE was established through a rigorous, multi-phase benchmarking procedure [5]:

- Initial Screening: Over fifty metaheuristic algorithms were tested on a tractable model (1D Ising chain) to identify the most promising candidates.

- Scaling Analysis: The shortlisted algorithms were tested on problems scaling up to 9 qubits to evaluate performance as problem size increased.

- Convergence Testing: Finalists were evaluated on a large-scale, 192-parameter Fermi-Hubbard model to assess convergence on a complex, clinically relevant problem.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes the relative performance of various optimizer classes based on the benchmark results described in the research [5] [10].

| Optimizer Class | Specific Algorithms | Performance in Noisy VQE Landscapes | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most Resilient | CMA-ES, iL-SHADE | Consistently best performance; robust to noise and barren plateaus [5] [10] | Adaptive, population-based, global search [29] |

| Robust Performers | Simulated Annealing (Cauchy), Harmony Search, Symbiotic Organisms Search | Good performance and robustness [5] | Global search strategies, less adaptive than top tier |

| Variable Performance | PSO, GA, standard DE variants | Performance degrades sharply with noise and problem scale [5] | Population-based but can be misled by noise without specific adaptations |

| Not Recommended | Gradient-based (BFGS, SLSQP) | Divergence or stagnation in noisy regimes [10] | Rely on accurate gradients, fail when noise dominates curvature |

Research Reagent Solutions

The table lists essential computational "reagents" for conducting VQE experiments on noisy chemical landscapes.

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Benchmark Models | Provides the test landscape. Examples: 1D Ising model (multimodal), Fermi-Hubbard model (strongly correlated systems) [5]. |

| Molecular Hamiltonians | The target quantum system for chemistry applications. Examples: H₂, H₄ chain, LiH [10]. |

| Parameterized Quantum Circuit (Ansatz) | Generates trial quantum states. Examples: tVHA (problem-inspired), TwoLocal (hardware-efficient) [10]. |

| Finite-Shot Noise Simulator | Emulates the statistical uncertainty (sampling noise) of real quantum hardware measurements [5] [10]. |

| Classical Optimizer Library | Provides the algorithms for parameter tuning. Should include CMA-ES, iL-SHADE, and other metaheuristics for comparison [5] [11]. |

Workflow Visualization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the key challenges when using optimizers on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices? NISQ devices are characterized by qubit counts ranging from tens to a few hundred, short coherence times, and significant operational noise without full error correction. This noise leads to error accumulation in quantum circuits, limiting their depth and causing inconsistent results. When running variational algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), this manifests as noisy energy expectation values, which can trap classical optimizers in local minima or on barren plateaus [30] [31].

2. Which classical optimizers are most robust for VQE in the presence of noise? The choice of optimizer depends on the noise landscape and computational cost. For general robustness, adaptive methods like ADAM (which uses momentum and adaptive learning rates) often perform well. For specifically noisy measurements, gradient-free methods like Simultaneous Perturbation Stochastic Approximation (SPSA) are highly effective, as they approximate gradients with far fewer function evaluations than standard gradient descent [31]. Bayesian Optimization (BO) is another powerful strategy for noisy, expensive-to-evaluate functions, as it constructs a probabilistic model of the objective function to guide the search efficiently [32] [33].

3. How does parameter initialization influence the convergence of VQE? Parameter initialization is decisive for VQE's performance. Poor initialization can lead to prolonged optimization or convergence to a high-energy local minimum. Research on systems like the silicon atom shows that initializing parameters to zero can lead to faster and more stable convergence. Furthermore, using chemically informed initial parameters (e.g., from a Hartree-Fock calculation) can provide a better starting point and improve overall performance [31].

4. What is a "barren plateau" and how can its impact be mitigated? Barren plateaus are regions in the parameterized quantum circuit's optimization landscape where the gradients of the cost function vanish exponentially with the number of qubits. This makes it incredibly difficult for optimizers to find a direction to improve. Mitigation strategies include using identity block initialization, designing problem-informed ansatzes with less randomness, and employing local cost functions instead of global ones [31].

5. When should Bayesian Optimization be considered over gradient-based methods? Bayesian Optimization (BO) should be considered when the optimization objective is a black-box function that is expensive to evaluate and noisy. This is typical for real-world experimental setups where each data point (e.g., from a spectroscopy measurement) takes considerable time or resources. BO is particularly advantageous when the number of function evaluations is severely limited, as it intelligently selects the most informative points to sample next [32] [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Convergence or Slow Optimization

| Possible Cause | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Noisy cost function evaluations on NISQ hardware [30] | - Use optimizers designed for noise, such as SPSA or Bayesian Optimization [31] [33].- Increase the number of measurement shots to reduce statistical noise, if computationally feasible. |

| Suboptimal parameter initialization [31] | - Initialize all parameters to zero as a baseline strategy.- Use a classically computed, chemically informed initial state (e.g., from Hartree-Fock orbitals). |

| Choice of classical optimizer [31] | - Switch to a more robust optimizer. ADAM often performs well for many systems.- For high-noise situations, try a gradient-free method like SPSA. |

| Encountering a Barren Plateau [31] | - Review the design of your parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz).- Employ strategies like identity block initialization to create a more favorable starting landscape. |

Problem 2: Inaccurate Final Energy (Failure to Achieve Chemical Precision)

| Possible Cause | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Limitations of the ansatz [31] | - For molecular systems, use a chemically inspired ansatz like UCCSD (Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles).- For larger systems, consider more efficient ansatzes like k-UpCCGSD to balance accuracy and computational cost. |

| Insufficient optimizer iterations | - Increase the maximum number of iterations allowed for the classical optimizer.- Monitor convergence history to ensure the energy has truly plateaued. |

| Hardware noise overwhelming the signal [30] | - If using a simulator, incorporate a noise model for a more realistic assessment.- On real hardware, use error mitigation techniques to improve the quality of expectation value measurements. |

Problem 3: Optimizer Instability or Erratic Behavior

| Possible Cause | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Gradients are too large or too small | - Tune the optimizer's learning rate or step size. A learning rate that is too high causes instability, while one that is too low leads to slow convergence.- For gradient-based optimizers, consider implementing gradient clipping. |

| Stochastic noise in the objective function [31] [32] | - When using stochastic optimizers like SPSA, ensure the algorithm's hyperparameters (e.g., the attenuation coefficients) are set appropriately for your problem.- Utilize a Bayesian Optimization framework that explicitly models and accounts for noise in its acquisition function [32]. |

Optimizer Performance & Selection Guide

The table below summarizes key optimizers and their characteristics based on performance across various quantum chemistry simulations. H₂, LiH, and H₄ are common benchmark systems.

| Optimizer | Type | Key Features | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADAM | Gradient-based | Adaptive learning rates, momentum; often shows superior convergence [31] | General-purpose use on simulators or low-noise scenarios. |

| SPSA | Gradient-free | Approximates gradient with only two measurements, very noise-resilient [31] | Noisy hardware experiments and high-dimensional parameter spaces. |

| L-BFGS | Gradient-based | Quasi-Newton method; uses an approximate Hessian for faster convergence [34] | Classical geometry optimizations and quantum simulations with precise gradients. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | Derivative-free | Builds a surrogate model; very sample-efficient [32] [33] | Expensive, noisy experiments (real hardware) and low evaluation budgets. |

Experimental Protocol: VQE for a Molecular System

This protocol outlines the general steps for running a VQE calculation to find the ground-state energy of a molecule like H₂, LiH, or H₄.

1. Problem Formulation:

- Define the Molecule: Specify the molecular geometry (atomic coordinates and charge).

- Choose a Basis Set: Select a suitable atomic orbital basis set (e.g., STO-3G, 6-31G).

- Generate the Qubit Hamiltonian:

- Compute the electronic Hamiltonian in a second-quantized form.

- Map the fermionic operators to qubit operators using a transformation like Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev [31].

- The result is a Hamiltonian expressed as a sum of Pauli strings.

2. Algorithm Setup:

- Select an Ansatz: Choose a parameterized quantum circuit. For molecular systems, UCCSD is a common, chemically inspired choice [31].

- Choose a Classical Optimizer: Select an optimizer based on your computational resources and noise considerations (see the Optimizer Performance table above).

- Initialize Parameters: Set the initial parameters for the ansatz. A simple and often effective strategy is to initialize all parameters to zero [31].

3. Execution:

- Hybrid Loop: For each iteration of the classical optimizer:

- The quantum computer (or simulator) prepares the trial state

|ψ(θ)⟩using the current parametersθ. - It measures the expectation values for each Pauli term in the Hamiltonian.

- The classical computer aggregates these values to compute the total energy expectation value

E(θ) = ⟨ψ(θ)|H|ψ(θ)⟩. - The classical optimizer uses this energy (and potentially gradient information) to propose a new set of parameters

θ_new.

- The quantum computer (or simulator) prepares the trial state

- Convergence: The loop continues until the energy converges within a specified tolerance or a maximum number of iterations is reached.

The following diagram illustrates this iterative workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational "reagents" and tools used in quantum computational chemistry.

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Parameterized Quantum Circuit (Ansatz) | A circuit with tunable parameters used to prepare trial quantum states (wavefunctions) for the molecule [31]. Examples include UCCSD and k-UpCCGSD. |

| Classical Optimizer | A numerical algorithm that minimizes the energy by iteratively updating the parameters of the ansatz [31]. Examples: ADAM, SPSA, L-BFGS. |

| Qubit Hamiltonian | The molecular electronic Hamiltonian transformed into an operator composed of Pauli matrices (X, Y, Z), which is the measurable cost function in VQE [31]. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) Framework | A machine-learning-guided optimization method that is highly sample-efficient and robust to noise, ideal for expensive experimental cycles [32] [33]. |

| Geometry Optimizer (e.g., LIBOPT3) | A classical computational driver used to find the stable molecular geometry (ground-state minimum) by minimizing the total energy with respect to atomic coordinates [34]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why does my genetic algorithm consistently converge to a suboptimal solution in my quantum chemistry simulation?

This is a classic sign that your algorithm is trapped in a local minimum, a point in the parameter space where the solution is good only in its immediate vicinity, but not the best possible (global minimum) [35]. In the context of noisy variational quantum algorithms (VQAs), the landscape is particularly rugged due to quantum hardware imperfections and sampling noise, making it easy for optimizers to get stuck [36] [37].

FAQ 2: What specific techniques can help my algorithm escape these local minima?

You can employ several strategies, often used in combination:

- Increase Mutation Rate: Introduce more random changes to individuals to explore a wider area of the search space [38].

- Introduce Fresh Random Individuals: Periodically adding new, random members to the population can inject diversity and help the population escape a stagnant region [38].

- Modify Selection Pressure: Keeping a larger percentage of the population (e.g., 80% instead of 50%) for the next generation, while creating a portion of new individuals, has proven effective in overcoming local traps [38].

- Use Diversity-Preserving Mechanisms: Techniques like fitness sharing can help maintain population diversity over many generations [38].

FAQ 3: How does the performance of Genetic Algorithms compare to traditional optimizers for noisy quantum problems?

Systematic benchmarking on problems like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) shows a clear trade-off. Traditional gradient-based methods like BFGS can be fast and accurate under moderate noise but may lack robustness. Genetic Algorithms and other global strategies like iSOMA demonstrate a strong potential to navigate complex, noisy landscapes, though they typically require more computational resources (function evaluations) [37]. The table below summarizes key findings.

Table 1: Benchmarking Optimizers for Noisy Quantum Landscapes (e.g., VQE) [37]

| Optimizer | Type | Performance under Noise | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| BFGS | Gradient-based | Accurate, minimal evaluations, robust under moderate noise | Fast but can be unstable in highly noisy regimes. |

| COBYLA | Gradient-free | Good for low-cost approximations | A balance of cost and performance. |

| iSOMA | Global (Swarm-based) | Good potential for noisy, multimodal landscapes | Computationally expensive, effective but slower. |

| SLSQP | Gradient-based | Can exhibit instability under noise | Can be fast but lacks robustness. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Premature Convergence and Loss of Population Diversity

Problem: Your algorithm's population becomes genetically similar within a few generations (10-20), stalling progress towards a better solution [38].

Diagnosis: This is often caused by excessive selection pressure (e.g., only selecting the top 1-2% of individuals) or insufficient genetic diversity from weak mutation and crossover [38].

Solution: Implement a multi-pronged strategy to maintain diversity.

- Adaptively Tune Mutation Rate: Start with a standard mutation rate (e.g., 5-10%). If the population's fitness stagnates for a set number of generations, progressively increase the mutation rate to "shake" the population out of the local minimum. Reduce it again once progress resumes [38].

- Implement Elitism with Random Immigrants: Protect a small number of the best individuals (elitism), but also replace a portion of the worst individuals (e.g., 20%) with completely new random ones each generation [38].

- Adjust Selection and Crossover: Experiment with keeping a larger portion of the population for reproduction and ensure your crossover operator is effectively combining genetic material without being overly destructive [38].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Parameters for Local Minima

| Parameter | Typical Symptom | Corrective Action | Experimental Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation Rate | Population homogenization | Increase rate adaptively during stagnation | Encourage exploration of new search areas. |

| Population Size | Consistent convergence to the same poor solution | Increase the size of the population | Provide a larger genetic pool for selection. |

| Selection Pressure | Rapid loss of diversity in early generations | Keep a larger percentage of the population; use fitness sharing | Balance exploitation of good traits with exploration. |

| Random Immigrants | The entire population is stuck in a single region | Introduce a percentage of new, random individuals each generation | Inject fresh genetic material to escape local minima. |

Experimental Protocol: Comparing Optimizers for a Noisy VQE Task

This protocol provides a methodology to empirically test the resilience of GAs against other optimizers, directly relevant to research on quantum optimizer selection.

1. Objective: To evaluate the robustness and convergence performance of a Genetic Algorithm compared to BFGS, COBYLA, and iSOMA on a VQE problem simulating the H₂ molecule under noisy conditions [37].

2. System Preparation:

- Molecule: H₂ at equilibrium bond length (0.74279 Å) [37].

- Method: State-Averaged Orbital-Optimized VQE (SA-OO-VQE) to target ground and first-excited states [37].

- Ansatz: Use a parameterized quantum circuit, such as the Unitary Coupled Cluster with Singlets and Doubles (UCCSD), with a limited number of trainable parameters [37].

3. Noise Emulation: Configure the quantum estimator to emulate real hardware noise models [37]:

- Phase Damping: Models loss of quantum phase information.

- Depolarizing: Introduces random Pauli errors.

- Thermal Relaxation: Simulates energy dissipation and dephasing over time.

4. Experimental Procedure:

- Run each optimizer (GA, BFGS, COBYLA, iSOMA) multiple times (e.g., 50 runs) from different random initializations.

- For each run, record:

- The final energy error (vs. known ground truth).

- The number of function evaluations (quantum circuit executions) required for convergence.

- The number of successful convergences to the global minimum.

- Statistically analyze the results to compare mean performance, variance, and reliability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for a GA-based Quantum Optimization Experiment

| Item / Concept | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | The main global optimization engine, mimicking natural selection to navigate complex, noisy cost landscapes [39]. |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | The hybrid quantum-classical algorithm used to find the ground-state energy of a molecular system (e.g., H₂) [36] [37]. |

| Parameterized Quantum Circuit (PQC) | The quantum circuit whose parameters are tuned by the classical optimizer. It prepares the trial quantum state [36]. |

| Fitness Function | The function to be minimized (e.g., the energy expectation value from the VQE). It guides the GA's selection process [39]. |

| Noise Models (Depolarizing, Thermal) | Software models that emulate real quantum hardware imperfections, crucial for testing optimizer robustness in the NISQ era [37]. |

| Mutation & Crossover Operators | The genetic operators that introduce novelty and combine traits, essential for escaping local minima and exploring the parameter space [39] [38]. |

Advanced Strategies for Robust Optimization in Noisy Realms