Navigating the Noise: Understanding Thresholds for Quantum Advantage in Chemical Computation

This article explores the critical challenge of quantum noise in achieving computational advantage for chemical and pharmaceutical applications.

Navigating the Noise: Understanding Thresholds for Quantum Advantage in Chemical Computation

Abstract

This article explores the critical challenge of quantum noise in achieving computational advantage for chemical and pharmaceutical applications. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive analysis of the current NISQ era, detailing how noise impacts established algorithms like VQE and the existence of thresholds beyond which quantum advantage is lost. The scope extends from foundational concepts of noise and its impact on qubits to methodological advances in hybrid algorithms, error mitigation strategies, and the rigorous benchmarking required to validate claims of quantum utility. The article synthesizes insights to outline a pragmatic path forward for leveraging near-term quantum devices in molecular simulation and drug discovery.

The Quantum Noise Problem: Defining the NISQ Era and Its Impact on Chemical Simulation

What is Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) Computing?

Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) computing refers to the current stage of quantum computing technology, characterized by quantum processors containing from roughly 50 to several hundred qubits that operate without full quantum error correction [1] [2]. The term, coined by John Preskill in 2018, encapsulates two key limitations of contemporary hardware [1] [3]. "Intermediate-Scale" denotes processors with a qubit count sufficient to perform computations beyond the practical simulation capabilities of classical supercomputers, yet insufficient for implementing large-scale, fault-tolerant quantum algorithms. "Noisy" emphasizes that these qubits and their gate operations are highly susceptible to errors from environmental decoherence, control inaccuracies, and other sources of noise, limiting the depth and complexity of feasible quantum circuits [1] [4].

In the context of chemical computation research, the NISQ era presents both a significant challenge and a unique opportunity. The challenge lies in the high noise levels that obscure the precise quantum states necessary for accurate molecular simulation. The opportunity is that the field is actively developing methods to extract useful, albeit imperfect, scientific data from these imperfect devices, pushing towards the noise thresholds where quantum computations for specific chemical problems might first demonstrate a tangible advantage over classical methods [1] [4] [5].

Technical Characteristics of the NISQ Era

Hardware Landscape and Performance Metrics

The performance of NISQ hardware is defined by a set of interconnected quantitative metrics, not merely the raw qubit count. Leading quantum computing modalities, including superconducting circuits, trapped ions, and neutral atoms, are all operating within the NISQ regime, each with distinct performance characteristics [4].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Leading NISQ Hardware Modalities (c. 2024-2025)

| Hardware Modality | Typical Qubit Count (Physical) | Two-Qubit Gate Fidelity | Single-Qubit Gate Fidelity | Measurement Fidelity | Key Distinguishing Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superconducting Circuits [4] | 100+ | 95–99.9% | >99.9% | ~99% | Fast gate operations (nanoseconds) |

| Trapped Ions [4] | 50+ | 99–99.5% | >99.9% | ~99% | Long coherence times, high connectivity |

| Neutral Atoms (Tweezers) [4] [5] | Hundreds | ~99.5% | >99.9% | ~98% | Reconfigurable qubit connectivity |

The fundamental constraint of NISQ computing is the exponential scaling of quantum noise. With per-gate error rates typically between 0.1% and 1%, a quantum circuit can only execute approximately 1,000 to 10,000 operations before noise overwhelms the computational signal [1]. This severely limits the "quantum volume" – a holistic metric incorporating qubit number, connectivity, and gate fidelity – of current devices and defines the boundary for feasible algorithms [1].

The Path Beyond NISQ: Error Correction and Fault Tolerance

The NISQ era is a transitional phase. The ultimate goal is Fault-Tolerant Application-Scale Quantum (FASQ) computing, where logical qubits encoded in many physical qubits are protected by quantum error correction (QEC) [6] [4]. This allows for arbitrarily long computations. However, the resource overhead is immense; a modest 1,000-logical-qubit processor could require around one million physical qubits given current error rates [6].

The transition is envisioned as a progression through computational power levels [4]:

- Megaquop Era: ~10ⶠquantum operations. This is the realm of advanced NISQ and early error correction.

- Gigaquop Era: ~10â¹ quantum operations. This requires more robust error correction.

- Teraquop Era: ~10¹² quantum operations. This is the domain of full FASQ machines capable of running complex algorithms like Shor's for large-number factoring.

Recent experimental progress is promising. In 2025, QuEra demonstrated magic state distillation on logical qubits, a critical component for universal fault-tolerant computing, reporting an 8.7x reduction in qubit overhead compared to traditional approaches [5]. Furthermore, Microsoft has announced significant error rate reductions, suggesting that scalable quantum computing could be "years away instead of decades" [1].

Key NISQ Algorithms for Chemical Computation

NISQ algorithms are specifically designed to work within the constraints of noisy, non-error-corrected hardware. They typically adopt a hybrid quantum-classical structure, where a quantum co-processor handles specific, quantum-native tasks (like preparing entangled states and measuring expectation values), while a classical computer handles optimization and control [1].

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE)

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is arguably the most successful NISQ algorithm for quantum chemistry applications, designed to find the ground-state energy of molecular systems [1].

Mathematical Foundation

VQE operates on the variational principle of quantum mechanics, which states that the expectation value of the energy for any trial wavefunction will always be greater than or equal to the true ground state energy. The algorithm aims to find the parameters for a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) that minimizes this expectation value [1].

The workflow is as follows:

- Problem Mapping: The molecular Hamiltonian (Ĥ) of interest is mapped to a qubit Hamiltonian via a transformation such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev.

- Ansatz Preparation: A parameterized quantum circuit, the ansatz |ψ(θ)⟩, is chosen to prepare a trial wavefunction on the quantum processor.

- Measurement: The quantum processor measures the expectation value of the Hamiltonian: E(θ) = ⟨ψ(θ)|Ĥ|ψ(θ)⟩.

- Classical Optimization: A classical optimizer (e.g., gradient descent, SPSA) adjusts the parameters θ to minimize E(θ). Steps 3 and 4 are repeated iteratively until convergence [1].

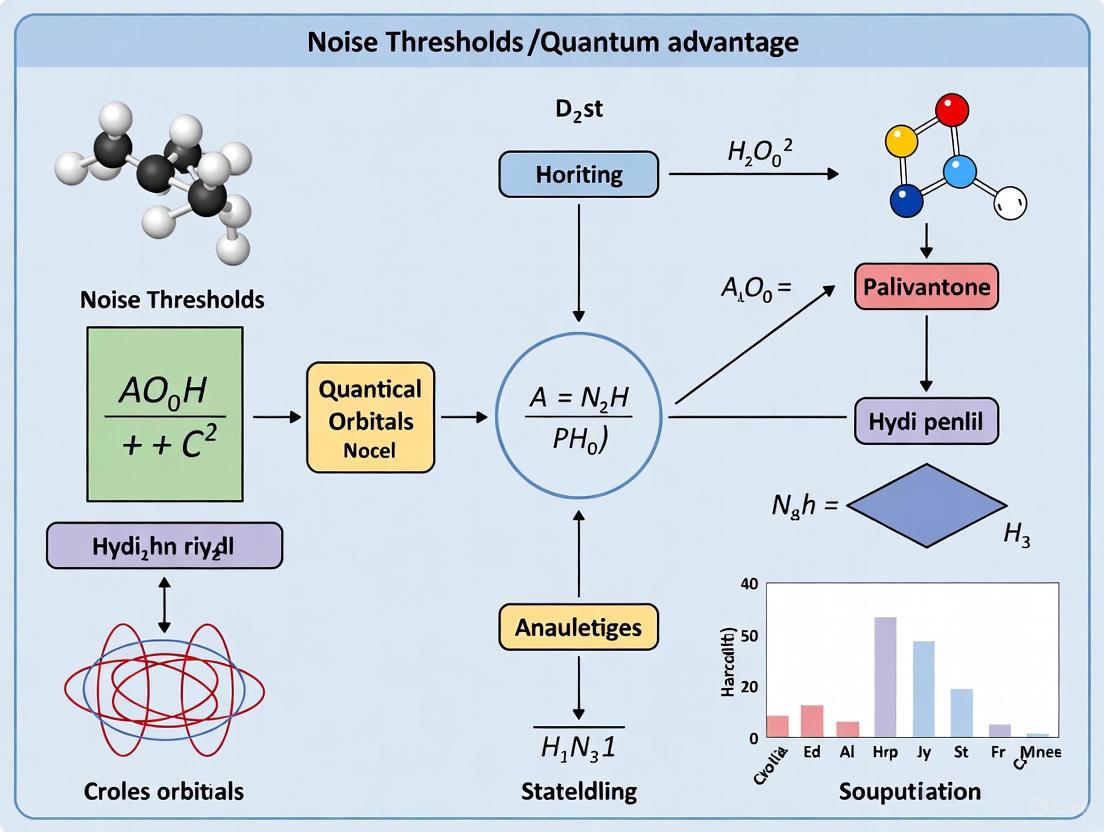

The following diagram illustrates the VQE workflow and its hybrid nature:

Experimental Protocol and Applications

VQE has been successfully demonstrated on various molecular systems, from simple diatomic molecules like Hâ‚‚ and LiH to more complex systems like water, achieving chemical accuracy (within 1 kcal/mol) for small molecules [1]. The protocol for a typical VQE experiment involves:

- Hamiltonian Generation: Classically compute the second-quantized Hamiltonian for the target molecule at a specific geometry using a quantum chemistry package (e.g., PySCF).

- Qubit Mapping: Transform the fermionic Hamiltonian into a Pauli string representation suitable for a quantum computer.

- Ansatz Selection: Choose an ansatz (e.g., Unitary Coupled Cluster, hardware-efficient) that balances expressibility with low gate depth.

- Execution with Error Mitigation: Run the quantum circuit, employing error mitigation techniques like Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) to improve result quality.

- Classical Optimization Loop: Iterate until the classical optimizer converges on a minimum energy value.

To address scalability for larger molecules, the Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) approach combined with VQE has shown promise, allowing efficient simulation by breaking the system into manageable fragments [1].

Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA)

While often applied to combinatorial problems, the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) can also be adapted for quantum chemistry. It encodes an optimization problem (e.g., finding a molecular configuration) into a cost Hamiltonian and uses alternating quantum evolution to search for the solution [1].

The algorithm prepares a state through the repeated application of two unitaries: |ψ(γ,β)⟩ = âˆâ±¼â‚Œâ‚áµ– eâ»â±Î²â±¼á´´â‚˜ eâ»â±Î³â±¼á´´á¶œ |+⟩⊗â¿

Here, ᴴᶜ is the cost Hamiltonian (encoding the problem), ᴴₘ is a mixer Hamiltonian, and p is the number of alternating layers, or "depth." A classical optimizer tunes the parameters {γⱼ, βⱼ} to minimize the expectation value ⟨ψ(γ,β)|ᴴᶜ|ψ(γ,β)⟩ [1].

Error Mitigation: The Essential Toolkit for NISQ Research

Since full quantum error correction is not feasible on NISQ devices, error mitigation techniques are essential for extracting meaningful results. These are post-processing methods applied to the results of many circuit executions, not active in-circuit correction [1] [6].

Table 2: Key Error Mitigation Techniques in the NISQ Era

| Technique | Core Principle | Experimental Overhead | Best-Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) [1] [6] | Artificially increases circuit noise (e.g., by gate folding), runs at multiple noise levels, and extrapolates results back to the zero-noise limit. | Polynomial increase in number of circuit executions. | General-purpose circuits, optimization problems (QAOA). |

| Symmetry Verification [1] | Exploits known symmetries in the problem (e.g., particle number conservation). Measurements violating these symmetries are discarded or corrected. | Moderate overhead; depends on error rate and symmetry. | Quantum chemistry simulations (VQE) with inherent conservation laws. |

| Probabilistic Error Cancellation [1] | Characterizes the device's noise model, then reconstructs the ideal computation by running a linear combination of noisy, implementable operations. | Sampling overhead can scale exponentially with error rates and circuit size. | Low-noise scenarios requiring high accuracy. |

| LY2109761 | LY2109761, CAS:700874-71-1, MF:C26H27N5O2, MW:441.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| LY2183240 | LY2183240, CAS:874902-19-9, MF:C17H17N5O, MW:307.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

These techniques inevitably increase the number of circuit repetitions (shots) required, with overheads ranging from 2x to 10x or more [1]. This creates a fundamental trade-off between accuracy and experimental resources. Recent benchmarking studies suggest that symmetry verification often provides the best performance for chemistry applications, while ZNE excels for optimization problems with fewer inherent symmetries [1].

For researchers embarking on NISQ-based chemical computation, a specific set of "research reagents" and tools is required.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for NISQ Chemical Computation

| Tool / Resource | Category | Function in Experiment | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid Algorithm Framework | Software | Provides the overarching structure for variational algorithms (VQE, QAOA), managing the quantum-classical loop. | Open-source packages like Qiskit, Cirq, PennyLane. |

| Parameterized Ansatz Circuit | Algorithm | The tunable quantum circuit that prepares the trial wavefunction; its design is critical for convergence. | Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC), Hardware-Efficient Ansatz. |

| Classical Optimizer | Software | The algorithm that adjusts the quantum circuit parameters to minimize the cost function (energy). | Gradient-based (BFGS), gradient-free (SPSA, COBYLA). |

| Error Mitigation Module | Software | Implements post-processing techniques (ZNE, symmetry verification) to improve raw results from the quantum hardware. | Built-in modules in Mitiq, Qiskit, TKet. |

| Cloud-Accessed QPU | Hardware | The physical quantum processing unit that executes the quantum circuits. Accessed via cloud platforms. | Processors from IBM, Quantinuum, QuEra, etc. |

| Molecular Hamiltonian Transformer | Software | Converts the classical molecular description into a qubit Hamiltonian operable on the QPU. | Plugins in Qiskit Nature, TEQUILA. |

Quantum Advantage: Current Status and Future Trajectory

The question of whether NISQ devices can achieve a practical quantum advantage for chemical computation remains open and hotly debated [1] [6]. While theoretical work suggests NISQ algorithms occupy a computational class between classical and ideal quantum computing, no experiment has yet demonstrated an unambiguous quantum advantage for a practical chemistry problem [1] [4].

The consensus is that the first truly useful applications will likely emerge in scientific simulation—providing new insights into quantum many-body physics, molecular systems, and materials science—before expanding to commercial applications like drug development [6] [4]. The community is moving towards a strategy of identifying "proof pockets"—small, well-characterized subproblems where quantum methods can be rigorously shown to confer an advantage [6]. The trajectory from NISQ to practical utility will be gradual, marked by incremental improvements in hardware fidelity, error mitigation, and algorithm design [4].

In the pursuit of quantum advantage for chemical computation, understanding and mitigating quantum noise is a fundamental prerequisite. Quantum computers promise to revolutionize computational chemistry and drug development by enabling the precise simulation of molecular systems that are intractable for classical computers [7]. However, the fragile nature of quantum information poses a significant barrier. The path to practical quantum chemistry applications requires navigating a complex landscape of noise sources that degrade computational accuracy, with specific thresholds that must be overcome to achieve reliable results [8] [9].

This technical guide examines the three primary categories of noise that limit current quantum devices: decoherence, gate errors, and environmental interference. We frame these challenges within the context of chemical computation research, where the precision requirement of chemical accuracy (1.6 × 10â»Â³ Hartree) establishes a clear benchmark for evaluating whether noise levels permit scientifically meaningful results [9]. Understanding these noise sources and their mitigation strategies is not merely an engineering concern but a central requirement for researchers aiming to leverage quantum computing for molecular simulation.

Quantum Decoherence

Quantum decoherence represents the process by which a quantum system loses its quantum behavior due to interactions with its environment, causing the irreversible loss of phase coherence in qubit superpositions [10]. This phenomenon fundamentally destroys the quantum correlations essential for quantum computation, effectively causing qubits to behave classically before computations can complete. For chemical computations, this directly translates to inaccurate molecular energy estimations and unreliable simulation results.

The main causes of decoherence include:

- Environmental interactions with photons, phonons, or magnetic fields

- Imperfect isolation from stray electromagnetic signals and thermal noise

- Material defects in qubit substrates that create localized charge fluctuations

- Control signal noise from the electronic systems manipulating qubit states [10]

Table 1: Characterizing Decoherence Sources and Their Impact on Chemical Computations

| Source Type | Physical Origin | Effect on Qubit | Impact on Chemical Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Relaxation | Coupling to thermal bath | Limits maximum circuit depth for quantum phase estimation | |

| Dephasing | Low-frequency noise from material defects | Introduces phase errors in quantum Fourier transforms | |

| Control Noise | Imperfect microwave pulses | Incorrect gate operations | Corrupts ansatz state preparation in VQE |

| Cross-talk | Inter-qubit coupling | Unwanted entanglement | Creates errors in multi-qubit measurement operations |

Gate Errors

Gate errors encompass inaccuracies in the quantum operations performed on qubits, representing a critical bottleneck for achieving fault-tolerant quantum computation. These errors directly impact the fidelity of quantum gates, which must exceed approximately 99.9% for meaningful quantum chemistry applications [8] [10].

For chemical computations, gate errors accumulate throughout circuit execution, particularly problematic for deep algorithms like Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) used in molecular energy calculations. The impact is especially pronounced in multi-qubit gates essential for simulating electron correlations in molecular systems [11] [8].

Recent research has quantified how gate errors impact chemical simulation accuracy. In experiments calculating molecular hydrogen ground-state energy, error correction became essential for circuits involving over 2,000 two-qubit gates, where even small per-gate error rates accumulated to significant deviations from expected results [8].

Environmental Interference

Environmental interference encompasses external noise sources that disrupt quantum computations despite shielding efforts. These include:

- Magnetic field fluctuations from laboratory equipment or urban infrastructure

- Cosmic rays that cause quasiparticle generation and sudden decoherence

- Vibrational noise from mechanical sources affecting trapped-ion systems

- Thermal fluctuations that excite qubits even in cryogenic environments [12] [10]

The impact of environmental interference is particularly significant for quantum sensors being developed to study chemical systems. Novel sensing approaches using nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamonds have revealed magnetic fluctuations at nanometer scales previously invisible to conventional measurement techniques [13]. These same fluctuations can disrupt quantum processors attempting to simulate molecular systems.

Experimental Characterization of Noise in Chemical Computations

Methodologies for Noise Quantification

Precise noise characterization requires specialized experimental protocols that isolate specific error mechanisms while performing chemically relevant computations:

Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) for Readout Error Mitigation

- Objective: Characterize and correct measurement errors that limit energy estimation precision

- Protocol: Execute informationally complete measurement sets alongside parallel QDT circuits

- Implementation: Apply blended scheduling to distribute calibration across temporal noise variations

- Chemical Application: Enabled reduction of measurement errors from 1-5% to 0.16% for BODIPY molecule energy calculations, approaching chemical accuracy thresholds [9]

Mid-Circuit Error Correction with Quantum Chemistry Algorithms

- Objective: Validate error correction benefits for concrete chemical simulations

- Protocol: Implement seven-qubit color codes with mid-circuit correction routines interspersed throughout QPE circuits

- Implementation: Compare circuits with and without error correction using identical chemical Hamiltonians

- Chemical Application: Demonstrated improved molecular hydrogen ground-state energy estimation despite increased circuit complexity [8]

Locally Biased Random Measurements

- Objective: Reduce shot overhead while maintaining measurement precision

- Protocol: Prioritize measurement settings with greater impact on specific molecular energy estimations

- Implementation: Hamiltonian-inspired classical shadows with optimized setting selection

- Chemical Application: Enabled precise measurement of BODIPY-4 molecule across multiple active spaces (8-28 qubits) with reduced resource requirements [9]

Table 2: Noise Characterization Methods and Their Efficacy in Chemical Computations

| Characterization Method | Measured Parameters | Hardware Platforms | Achievable Precision | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Benchmarking | Gate fidelity, Clifford error rates | Superconducting, trapped ions | ~99.9% gate fidelity | Does not capture correlated noise |

| Quantum Detector Tomography | Readout error matrices, assignment fidelity | IBM Eagle, custom sensors | ~0.16% measurement error | Requires significant circuit overhead |

| Entangled Sensor Arrays | Magnetic field correlations, spatial noise profiles | Diamond NV centers | 40x sensitivity improvement | Currently specialized for sensing applications |

| Root Space Decomposition | Noise spreading patterns, symmetry properties | Theoretical framework | Clear noise classification | Requires further experimental validation |

Noise Propagation in Chemical Algorithms

Understanding how specific noise sources affect quantum chemistry algorithms is essential for developing error-aware computational approaches:

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE)

- Decoherence Impact: Limits circuit depth and ansatz complexity

- Gate Error Sensitivity: Affects parameter optimization trajectories

- Mitigation Approaches: Noise-aware optimizers, dynamical decoupling

Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE)

- Decoherence Impact: Phase coherence loss destroys energy resolution

- Gate Error Sensitivity: Cumulative errors across many controlled operations

- Mitigation Approaches: Quantum error correction, partial fault-tolerance [8]

Sample-Based Quantum Diagonalization (SQD)

- Decoherence Impact: Reduces fidelity of prepared configurations

- Gate Error Sensitivity: Affects sampling efficiency

- Mitigation Approaches: Self-consistent correction (S-CORE), implicit solvation models [14]

Noise Propagation in Quantum Chemistry Algorithms

Mitigation Strategies and Error Correction

Quantum Error Correction for Chemical Computations

Quantum Error Correction (QEC) encodes logical qubits across multiple physical qubits to detect and correct errors without collapsing the quantum state. For chemical computations, specific approaches have demonstrated promising results:

Color Codes for Molecular Energy Calculations

- Implementation: Seven-qubit color code protecting logical qubits in QPE circuits

- Chemical Application: Calculation of molecular hydrogen ground-state energy on Quantinuum H2-2 trapped-ion processor

- Performance: Energy estimate within 0.018 hartree of exact value (above chemical accuracy but significant progress)

- Advancement: First complete quantum chemistry simulation using QEC on real hardware [8]

Partial Fault-Tolerance

- Rationale: Balance between error suppression and resource overhead

- Implementation: Lightweight circuits and recursive gate teleportation techniques

- Advantage: Makes error correction feasible on current-generation hardware

- Chemical Application: Enabled quantum chemistry simulations with 22 qubits and >2,000 two-qubit gates [8]

Hardware-Level Noise Mitigation

Cryogenic Systems and Shielding

- Operating quantum processors at temperatures near absolute zero (typically 10-15 mK) reduces thermal noise

- Advanced electromagnetic shielding minimizes environmental interference

- Enables coherence time extension from microseconds to milliseconds in state-of-the-art systems [10]

Decoherence-Free Subspaces (DFS)

- Encoding quantum information in specific combinations immune to collective noise

- Quantinuum's H1 hardware demonstrated 10x extension of quantum memory lifetimes using DFS

- Particularly effective against symmetrical decoherence processes like common-mode phase noise [10]

Dynamical Decoupling

- Applying sequences of control pulses to refocus qubit evolution and mitigate low-frequency noise

- Essential for reducing memory noise identified as dominant error source in chemical computations [8]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Methods for Noise-Resilient Quantum Chemistry Experiments

| Resource | Function | Example Implementation | Relevance to Chemical Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trapped-Ion Quantum Computers | High-fidelity gates, all-to-all connectivity | Quantinuum H2 system | 99.9% 2-qubit gate fidelity enables deeper circuits |

| Superconducting Qubit Arrays | Scalable processor architectures | IBM Eagle r3 | >100 qubits for complex active spaces |

| Quantum Detector Tomography | Readout error characterization and mitigation | Parallel QDT with blended scheduling | Reduces measurement errors to 0.16% |

| Diamond NV Center Sensors | Magnetic noise profiling and characterization | Entangled nitrogen-vacancy pairs | 40x sensitivity improvement for noise mapping |

| Locally Biased Classical Shadows | Efficient measurement for complex observables | Hamiltonian-inspired random measurements | Reduces shot overhead for molecular energy estimation |

| Implicit Solvent Models | Environment inclusion without explicit quantum treatment | IEF-PCM integration with SQD | Enables solution-phase chemistry simulations |

| LY256548 | LY256548, CAS:107889-31-6, MF:C19H27NO2S, MW:333.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| LY-411575 | LY-411575, CAS:209984-57-6, MF:C26H23F2N3O4, MW:479.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Pathways Toward Quantum Advantage in Chemistry

The achievement of quantum advantage for chemical computations requires simultaneous progress across multiple fronts, with noise mitigation at the core:

Hardware Improvements

- Increasing coherence times through material science advances

- Enhancing gate fidelities beyond 99.9% threshold for meaningful computations

- Developing novel qubit designs with inherent noise resistance (topological qubits) [10] [7]

Algorithmic Innovations

- Error-aware compilers that optimize for specific hardware noise profiles

- Resource-efficient error correction tailored to chemical computation requirements

- Hybrid quantum-classical approaches that leverage classical resources for noise resilience [9] [14]

Noise-Tailored Applications

- Identifying chemical problems with inherent noise resistance

- Developing problem-specific error mitigation rather than general-purpose solutions

- Focusing on industrially relevant applications like drug binding and catalyst design [7] [14]

Pathway to Quantum Advantage in Chemical Computations

The noise thresholds for quantum advantage in chemical research are problem-dependent, with current demonstrations showing progress toward but not yet achieving chemical accuracy for industrially relevant molecules. The integration of advanced error mitigation with problem-specific algorithmic optimizations represents the most promising path forward. As hardware continues to improve and noise characterization becomes more sophisticated, the timeline for practical quantum chemistry applications continues to accelerate, with meaningful advancements already being demonstrated on today's noisy quantum devices.

The quest for quantum advantage in chemical computation represents a frontier where quantum computers are poised to outperform their classical counterparts in simulating molecular systems and chemical reactions. This advantage is particularly anticipated for problems involving strongly correlated electrons, where classical methods like density functional theory (DFT) and post-Hartree-Fock approaches often struggle with accuracy and exponential scaling [15]. The field has progressed to a point where researchers are actively demonstrating that quantum computers can serve as useful scientific tools capable of computations beyond the reach of exact classical algorithms [16]. However, the path to achieving and maintaining quantum advantage is far from straightforward, as it is profoundly constrained by a formidable adversary: quantum noise.

Current quantum devices operate in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, characterized by systems with limited qubit counts and coherence times, and more importantly, significant susceptibility to errors [15] [17]. For chemical computation research, this noise presents a critical challenge, as accurate simulation of molecular systems requires precise quantum operations to reliably calculate properties such as ground-state energies, reaction barriers, and spectroscopic characteristics [18]. The fragility of quantum advantage manifests in two distinct patterns: a gradual decline in computational superiority as noise increases, and in some cases, a dramatic phenomenon termed "sudden death" of quantum advantage, where beyond a specific noise threshold, the quantum advantage disappears abruptly [19].

Understanding these noise-induced limitations is particularly crucial for researchers in pharmaceutical development and materials science, where quantum computing promises to accelerate drug discovery and enable the design of novel materials with tailored properties [20]. This technical analysis explores the theoretical foundations, experimental evidence, and mitigation strategies surrounding the fragility of quantum advantage in chemical computation, providing a framework for navigating the transition from NISQ-era devices to fault-tolerant quantum computing.

Theoretical Framework: Noise Thresholds and Quantum Computational Limits

The "Queasy Instance" Paradigm and Instance-Specific Advantage

Traditional complexity theory classifies problems according to their worst-case difficulty, which often obscures the potential for quantum advantage on specific problem instances. A recent theoretical framework introduces the concept of "queasy instances" (quantum-easy), which are problem instances comparatively easy for quantum computers but appear difficult for classical ones [21]. This approach utilizes Kolmogorov complexity to measure the minimal program size required to solve specific problem instances, comparing classical and quantum description lengths for the same problem. When the quantum description is significantly shorter, these queasy instances represent precise locations where quantum computers offer provable advantage—pockets of potential that worst-case analysis would overlook [21].

For chemical computation, this framework is particularly relevant, as different molecular systems and properties may present as queasy instances for quantum simulation. The significant insight is that algorithmic utility emerges when a quantum algorithm solves a queasy instance—the compact program can provably solve an exponentially large set of other instances as well [21]. This property means that identifying these instances in chemical space could unlock quantum advantage for entire classes of molecular simulations, from catalyst design to drug binding affinity calculations.

The Goldilocks Zone for Noisy Quantum Advantage

Recent theoretical work has established that the possibility of noisy quantum computers outperforming classical computers may be restricted to a "Goldilocks zone"—an intermediate region between too few and too many qubits relative to the noise level [22]. This constrained regime emerges from the behavior of classical algorithms that can simulate noisy quantum circuits using Feynman path integrals, where the number of significant paths is dramatically reduced by noise [22].

The mathematical relationship governing this phenomenon reveals that the classical simulation's runtime scales polynomially with the number of qubits but exponentially with the inverse of the noise rate per gate [22]. This scaling has profound implications for chemical computation research: reducing noise in quantum hardware is substantially more important than merely increasing qubit counts for achieving quantum advantage. The theoretical models further demonstrate that excessive noise can eliminate quantum advantage regardless of whether the quantum circuit employs random or carefully structured gates [22].

Table 1: Theoretical Models of Noise-Induced Limitations on Quantum Advantage

| Theoretical Model | Key Insight | Implication for Chemical Computation |

|---|---|---|

| Queasy Instances [21] | Advantage exists for specific problem instances rather than entire problem classes | Targeted approach to molecular simulation; identify quantum-easy chemical systems |

| Goldilocks Zone [22] | Advantage constrained to intermediate qubit counts relative to noise levels | Hardware development must balance scale with error reduction |

| Sudden Death Phenomenon [19] | Advantage can disappear abruptly at specific noise thresholds | Critical need for precise noise characterization in quantum chemistry applications |

| Pauli Path Simulation [22] | Noise reduces complexity of classical simulation of quantum circuits | Higher noise environments diminish quantum computational uniqueness |

The Sudden Death Phenomenon in Quantum Correlation Generation

A particularly striking manifestation of quantum advantage fragility emerges in the domain of correlation generation. Research has rigorously demonstrated that as the strength of quantum noise continuously increases from zero, quantum advantage generally declines gradually [19]. However, in certain cases, researchers have observed the "sudden death" of quantum advantage—when noise strength exceeds a critical threshold, the advantage disappears abruptly from a non-negligible level [19]. This phenomenon reveals the tremendous harm of noise to quantum information processing from a novel viewpoint, suggesting non-linear relationships between error rates and computational advantage that may have significant implications for chemical computation on near-term devices.

Quantitative Analysis of Noise Impacts on Chemical Computations

Error Propagation in Molecular Energy Calculations

In the context of chemical computation, even modest levels of individual gate errors can drastically skew quantum computation results when executing deep quantum circuits required for molecular simulations [23]. Numerical studies implementing the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) for calculating ground-state energies of molecular systems have quantified the sensitive relationship between circuit depth, noise levels, and result accuracy.

For instance, in quantum linear response (qLR) theory calculations for obtaining spectroscopic properties, comprehensive noise studies have revealed the significant impact of shot noise and hardware errors on the accuracy of computed absorption spectra [18]. These analyses have led to the development of novel metrics to predict noise origins in quantum algorithms and have demonstrated that substantial improvements in hardware error rates are necessary to advance quantum computational chemistry from proof of concept to practical application [18].

Table 2: Quantitative Error Rates and Their Impacts on Chemical Computation

| Error Metric | Current State | Target for Chemical Advantage | Impact on Molecular Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gate Error Rates | 0.000015% per operation (best achieved) [20] | <0.0001% for complex molecules | Determines maximum feasible circuit depth for accuracy |

| Coherence Times | 0.6 milliseconds (best-performing qubits) [20] | >100 milliseconds | Limits complexity of executable quantum circuits |

| Two-Qubit Gate Fidelity | ~99.8% (NISQ devices) | >99.99% | Affects accuracy of electron correlation calculations |

| Readout Error | 1-5% (typical NISQ) | <0.1% | Impacts measurement precision in expectation values |

Resource Requirements for Chemical Accuracy

Benchmarking studies of quantum algorithms for chemical systems provide crucial data on the resource requirements for achieving chemical accuracy (typically defined as ~1 kcal/mol error in energy calculations). Research on aluminum clusters (Al-, Al2, and Al3-) using VQE within a quantum-DFT embedding framework demonstrated that circuit choice and basis set selection significantly impact accuracy [15]. While these calculations achieved percent errors consistently below 0.02% compared to classical benchmarks, they required careful optimization of parameters including classical optimizers, circuit types, and repetition counts [15].

The implementation of accurate chemical reaction modeling on NISQ devices further illustrates the resource challenges. Protocols combining correlation energy-based active orbital selection, effective Hamiltonians from the driven similarity renormalization group (DSRG) method, and noise-resilient wavefunction ansatzes have enabled quantum resource-efficient simulations of systems with up to tens of atoms [17]. These approaches represent critical steps toward quantum utility in the NISQ era, yet they also highlight the delicate balance between computational accuracy and noise resilience.

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Noise Vulnerability

Protocol 1: Quantum Linear Response for Spectroscopic Properties

The quantum linear response (qLR) theory provides a framework for obtaining spectroscopic properties on quantum computers, serving as both an application and a diagnostic tool for noise impacts [18]. The experimental workflow involves:

System Preparation: Initialize the quantum computer to represent the molecular ground state using a prepared reference wavefunction.

Operator Application: Apply a set of excitation operators to generate the relevant excited states for spectroscopic characterization.

Response Measurement: Measure the system response to these perturbations through carefully designed quantum circuits.

Signal Processing: Transform raw measurements into spectroscopic properties through classical post-processing.

This protocol introduces specialized metrics to analyze and predict noise origins in the quantum algorithm, including an Ansatz-based error mitigation technique that reveals the significant impact of Pauli saving in reducing measurement costs and noise in subspace methods [18]. Implementation on hardware using up to cc-pVTZ basis sets has demonstrated proof of principle for obtaining absorption spectra, while simultaneously highlighting the substantial improvements needed in hardware error rates for practical impact [18].

Protocol 2: Noise-Resilient Chemical Reaction Modeling

A comprehensive protocol for accurate chemical reaction modeling on NISQ devices combines multiple noise-mitigation strategies into an integrated workflow [17]:

Correlation-Based Orbital Selection: Automatically select active orbitals using orbital correlation information derived from many-body expansion full configuration interaction methods. This focuses quantum resources on the most chemically relevant orbitals.

Effective Hamiltonian Construction: Utilize the driven similarity renormalization group (DSRG) method with selected active orbitals to construct an effective Hamiltonian that reduces quantum resource requirements.

Hardware Adaptable Ansatz (HAA) Implementation: Employ noise-resilient wavefunction ansatzes that adapt to hardware constraints while maintaining expressibility for chemical accuracy.

VQE Execution with Error Mitigation: Run the Variational Quantum Eigensolver algorithm with integrated error suppression techniques, using either simulators or actual quantum hardware.

This protocol has been demonstrated in the simulation of Diels-Alder reactions on cloud-based superconducting quantum computers, representing an important step toward quantum utility in practical chemical applications [17]. The integration of these components provides a systematic pathway for high-precision simulations of complex chemical processes despite hardware limitations.

Protocol 3: Symmetry-Based Noise Characterization

Breakthrough research in noise characterization has exploited mathematical symmetries to simplify the complex problem of understanding noise propagation in quantum systems [24]. This protocol involves:

System Representation: Apply root space decomposition to represent the quantum system as a ladder structure, with each rung serving as a discrete state of the system.

Noise Application: Introduce various noise types to the system to observe whether specific noise causes the system to jump between rungs.

Noise Classification: Categorize noise into distinct classes based on symmetry properties, which determines appropriate mitigation techniques for each class.

Mitigation Implementation: Apply specialized error suppression methods based on the noise classification, contributing to building error-resilient quantum systems.

This approach provides insights not only for designing better quantum systems at the physical level but also for developing algorithms and software that explicitly account for quantum noise [24]. For chemical computation, this method offers a structured framework for understanding how noise impacts complex quantum simulations of molecular systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Noise-Resilient Chemical Computation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Noise-Resilient Quantum Chemical Computation

| Research Reagent | Function | Application in Chemical Computation |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware Adaptable Ansatz (HAA) [17] | Noise-resilient parameterized quantum circuit | Adapts circuit structure to hardware constraints while maintaining chemical accuracy |

| Driven Similarity Renormalization Group (DSRG) [17] | Constructs effective Hamiltonians | Reduces quantum resource requirements for complex molecular systems |

| Noise-Robust Estimation (NRE) [23] | Noise-agnostic error mitigation framework | Suppresses estimation bias in quantum expectation values without explicit noise models |

| Zero Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | Error mitigation through noise scaling | Extrapolates results to zero-noise limit for improved accuracy |

| Quantum Linear Response (qLR) Theory [18] | Computes spectroscopic properties | Enables prediction of absorption spectra and excited state properties |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) [15] | Hybrid quantum-classical algorithm | Calculates molecular ground state energies with polynomial resources |

| Active Space Transformer [15] | Selects chemically relevant orbitals | Focuses quantum resources on most important electronic degrees of freedom |

| Symmetry-Based Noise Characterization [24] | Classifies noise by symmetry properties | Informs targeted error mitigation strategies based on noise type |

| LY456236 | LY456236, CAS:338736-46-2, MF:C16H16ClN3O2, MW:317.77 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lyngbyatoxin B | Lyngbyatoxin B|For Research Use Only | Lyngbyatoxin B is an oxidized derivative of the dermatotoxin Lyngbyatoxin A. This product is for research applications only and is not intended for personal use. |

Error Mitigation Strategies: Bridging NISQ to Fault Tolerance

Advanced Error Mitigation Frameworks

While quantum error correction remains the long-term solution for fault-tolerant quantum computing, near-term and mid-term quantum devices benefit tremendously from error mitigation techniques that improve accuracy without the physical-qubit overhead of full error correction [23]. Multiple strategies have emerged, broadly categorized into noise-aware and noise-agnostic approaches.

Noise-Robust Estimation (NRE) represents a significant advancement in noise-agnostic error mitigation. This framework systematically reduces estimation bias without requiring detailed noise characterization [23]. The key innovation is the discovery of a statistical correlation between the residual bias in quantum expectation value estimations and a measurable quantity called normalized dispersion. This correlation enables bias suppression without explicit noise models or assumptions about noise characteristics, making it particularly valuable for chemical computations where precise noise profiles may be unknown or time-varying [23].

Experimental validation of NRE on superconducting quantum processors has demonstrated its effectiveness for circuits with up to 20 qubits and 240 entangling gates. In applications to quantum chemistry, NRE has accurately recovered the ground-state energy of the H4 molecule despite severe noise degradation from high circuit depths [23]. The technique consistently outperforms standard error mitigation methods, including Zero Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) and Clifford Data Regression (CDR), achieving near bias-free estimations in many cases.

Integration of Error Mitigation in Quantum Chemistry Workflows

For chemical computation, error mitigation must be integrated throughout the computational workflow, from problem formulation to result validation. The quantum-DFT embedding approach exemplifies this integration, combining classical DFT with quantum computation to mitigate hardware constraints of NISQ devices [15]. This hybrid methodology divides the system into a classical region (handled by DFT) and a quantum region (solved on a quantum computer), enabling accurate simulations of larger and more complex systems than possible with pure quantum approaches alone.

Industry leaders are increasingly incorporating error mitigation as a service within quantum computing platforms. For example, IBM's Qiskit Function Catalog provides access to advanced error mitigation techniques like Algorithmiq's Tensor Network Error Mitigation (TEM) and Qedma's Quantum Error Suppression and Error Mitigation (QESEM) [16]. These services demonstrate the use of classical high-performance computing (HPC) to extend the reach of current quantum computers, forming an architecture known as quantum-centric supercomputing [16].

The commercial impact of these advancements is already emerging. Companies like Q-CTRL have benchmarked IBM Quantum systems against classical, quantum annealing, and trapped-ion technologies for optimization, unlocking a more than 4x increase in solvable problem size and outperforming commonly used classical local solvers [16]. In collaboration with Network Rail on a scheduling solution, Q-CTRL's Performance Management circuit function enabled the largest demonstration to date of constrained quantum optimization, accelerating the path to practical quantum advantage [16].

The fragility of quantum advantage presents both a formidable challenge and a clarifying framework for the quantum computing community. The phenomena of gradual decline and sudden death of quantum advantage establish clear boundaries for the computational territory where quantum devices can outperform classical approaches. For chemical computation researchers and pharmaceutical development professionals, these boundaries define a strategic roadmap for integrating quantum technologies into the molecular discovery pipeline.

The theoretical models and experimental protocols outlined in this analysis provide a foundation for navigating the noise landscape in quantum chemical computation. The emergence of sophisticated error mitigation techniques, such as Noise-Robust Estimation and hardware-adaptable ansatzes, creates a bridge between current NISQ devices and future fault-tolerant quantum computers. These advances, combined with hybrid quantum-classical approaches like quantum-DFT embedding, enable researchers to extract tangible value from quantum systems despite their current limitations.

As hardware continues to evolve with breakthroughs in error correction and qubit coherence, the thresholds for maintaining quantum advantage will progressively shift toward more complex chemical problems. The ongoing characterization of noise impacts and development of mitigation strategies will remain essential for leveraging quantum computation in pharmaceutical research, materials design, and fundamental chemical discovery. Through continued refinement of both hardware and algorithmic approaches, the research community moves closer to realizing the full potential of quantum advantage in chemical computation—transforming molecular design and accelerating the development of new therapeutics and materials.

Why Chemistry? The Promise and Challenge of Molecular Simulation

Molecular simulation represents one of the most promising near-term applications for quantum computing, poised to revolutionize how we understand and design molecules for drug discovery and materials science. This field sits at the intersection of computational chemistry and quantum information science, where the exponential complexity of modeling quantum mechanical systems presents both an insurmountable challenge for classical computers and a perfect opportunity for quantum computation. The fundamental thesis framing this research is that achieving practical quantum advantage in molecular simulation is not merely a hardware problem but requires navigating precise noise thresholds and developing robust algorithmic frameworks that can deliver verifiable results under realistic experimental constraints.

Quantum chemistry is inherently difficult because the computational resources required to solve the Schrödinger equation for many-electron systems scale exponentially with system size on classical computers. While approximation methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) have enabled significant progress, their accuracy remains limited for critical applications including catalyst design, photochemical processes, and non-covalent interactions in biological systems. Quantum computers, which naturally emulate quantum phenomena, offer the potential to solve these problems with significantly improved accuracy and scaling. However, as we approach the era of early fault-tolerant quantum computation, understanding the precise conditions under which this potential can be realized—despite noisy hardware—becomes the central scientific challenge [25] [22].

The Quantum Promise: Efficient Molecular Simulation

The Fundamental Scaling Advantage

Quantum computers offer exponential scaling advantages for specific computational tasks in quantum chemistry, primarily through their ability to efficiently represent quantum states that would require prohibitive resources on classical hardware. This capability stems from several key algorithmic approaches:

- Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE): Provides a direct method for calculating molecular energy eigenvalues with guaranteed precision, enabling the determination of ground and excited state energies with complexity scaling polynomially with system size, compared to the exponential scaling of full configuration interaction methods on classical computers.

- Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE): Designed for noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, this hybrid quantum-classical algorithm uses parameterized quantum circuits to prepare trial wavefunctions with classical optimization of parameters. While more noise-resistant, its scaling advantages are more modest than QPE.

- Time Evolution Algorithms: Quantum computers can efficiently simulate the time-dependent Schrödinger equation, enabling studies of reaction dynamics, spectroscopic properties, and non-equilibrium processes that are particularly challenging for classical computational methods [26].

The table below summarizes the comparative scaling of classical and quantum approaches for key electronic structure problems:

Table 1: Computational Scaling Comparison for Molecular Simulation

| Computational Task | Best Classical Scaling | Quantum Algorithm Scaling | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ground State Energy (Exact) | Exponential in system size | Polynomial in system size and precision | Exponential speedup for precise solutions |

| Excited State Calculations | Exponential with limited accuracy | Polynomial with guaranteed precision | Access to dynamics and spectroscopy |

| Active Space Correlation | O(Nâµ)-O(Nâ¸) in active space size | Polynomial in full system size | Larger active spaces feasible |

| Time Evolution | Exponential in simulation time | Polynomial in time and system size | Quantum dynamics tractable |

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Materials Research

The potential applications of quantum-accelerated molecular simulation span multiple high-impact domains:

- Drug Discovery: Accurate prediction of protein-ligand binding affinities remains a fundamental challenge in structure-based drug design. Quantum simulations could provide more reliable binding energy calculations by better describing charge transfer, dispersion interactions, and solvent effects, potentially reducing the empirical optimization cycle in lead compound development.

- Catalyst Design: Transition metal catalysts often involve strongly correlated electrons and multi-configurational wavefunctions that challenge classical computational methods. Quantum simulation could enable accurate prediction of reaction barriers and catalytic cycles for industrially important processes.

- Materials Science: The design of high-temperature superconductors, organic photovoltaics, and battery materials would benefit from more accurate electronic structure calculations that quantum computers might provide, particularly for systems with complex electronic correlations [27] [26].

The Noise Challenge: Thresholds for Quantum Advantage

The Goldilocks Zone of Quantum Advantage

Current quantum hardware operates in what has been termed a "Goldilocks zone" for quantum advantage—a precarious balance between having sufficiently many qubits to perform meaningful computations while maintaining noise levels low enough to preserve quantum coherence throughout the calculation. Recent research has established fundamental constraints on noisy quantum devices:

- Noise-Induced Classical Simulability: As identified in recent work by Schuster et al., highly noisy quantum circuits can be efficiently simulated using classical algorithms based on Feynman path integrals, where noise effectively "kills off" the contribution of most Pauli paths. This places a fundamental constraint on the minimum gate fidelity required to achieve quantum advantage [22].

- The Critical Trade-off: The classical simulation runtime scales polynomially with qubit count but exponentially with the inverse of the noise rate per gate. This implies that reducing noise is substantially more important than increasing qubit count for achieving quantum advantage, establishing a critical threshold relationship between these parameters.

- Anticoncentration Requirement: For sampling-based quantum advantage experiments, the classical simulability results apply primarily to circuits that "anticoncentrate," where the output distribution is not overly concentrated on a few outcomes. Circuits with realistic "nonunital" noise may evade these constraints, suggesting alternative pathways to advantage [22].

The table below quantifies the relationship between key hardware parameters and their implications for achieving quantum advantage in molecular simulation:

Table 2: Noise and Resource Requirements for Quantum Advantage

| Parameter | NISQ Era | Early FTQC | Target for Practical Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gate Error Rate | 10â»Â²-10â»Â³ | 10â»â´-10â»âµ | Below 10â»â¶ (logical qubits) |

| Qubit Count | 50-1000 (physical) | 10³-10ⴠ(physical) | 10²-10³ (logical) |

| Coherence Time | 100-500 μs | >1 ms | Sufficient for 10â¸-10¹Ⱐoperations |

| Error Correction | None or partial | Surface code implementations | Fully fault-tolerant |

| Verification Method | Classical approximations | Cross-device verification | Experimental validation |

Verifiability: A Necessary Condition for Utility

A critical consideration for practical quantum advantage in chemistry is the verifiability of computational results. As emphasized by the Google Quantum AI team, computations lack practical utility unless solution quality can be efficiently checked. For quantum chemistry applications, this presents both a challenge and opportunity:

- Classical Verification: The highest standard involves efficient classical verification of quantum results. For some quantum chemistry problems, this may be possible through comparison with approximate classical methods or known physical constraints.

- Cross-Device Verification: When classical verification is infeasible, agreement between results from different quantum devices provides a lower but still valuable verification standard, effectively treating nature as the ultimate arbiter of correctness.

- Application-Specific Validation: For drug discovery applications, the ultimate validation comes from experimental measurement of predicted molecular properties, creating a feedback loop that improves both computational and experimental approaches [25].

This verification requirement fundamentally constrains which quantum algorithms are likely to yield practical advantages. Algorithms based on sampling from scrambled quantum states, while interesting for demonstrating quantum capability, are unlikely to provide practical utility for chemistry applications unless their outputs can be efficiently verified [25].

Experimental Protocols for Quantum Chemistry

Workflow for Molecular Simulation on Quantum Hardware

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for molecular simulation using quantum computers, integrating both quantum and classical computational resources:

Diagram 1: Quantum Chemistry Workflow

Noise Characterization Protocol

Accurate noise characterization is essential for understanding the potential for quantum advantage in chemical computation. The following experimental protocol provides a methodology for assessing hardware capabilities:

- Randomized Benchmarking: Perform standard Clifford randomized benchmarking on individual qubits and pairs of qubits involved in the simulation to determine baseline gate fidelities. This establishes the fundamental noise floor for the hardware.

- Cycle Benchmarking: For deeper circuits required for molecular simulations, implement cycle benchmarking to measure the fidelity of repeated circuit blocks similar to those used in the quantum chemistry ansatz.

- Cross-Platform Verification: Execute identical molecular simulation problems across different quantum hardware platforms (superconducting, ion trap, photonic) to identify platform-specific error mechanisms and validate results through cross-platform consistency.

- Classical Simulation Comparison: For small instances where classical simulation is feasible, compare quantum results with exact classical calculations to establish accuracy benchmarks and identify systematic error patterns.

- Noise Scaling Analysis: Systematically study how errors accumulate as molecular system size increases by simulating homologous molecular series with progressively larger active spaces [22].

The table below details key experimental parameters and measurement techniques for comprehensive noise characterization:

Table 3: Noise Characterization Protocol

| Characterization Method | Measured Parameters | Target Values for Chemistry | Impact on Simulation Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Benchmarking | Single/two-qubit gate fidelity | >99.9% for critical gates | Directly affects circuit depth limitations |

| State Tomography | Preparation fidelity | >99% | Affects initial state preparation |

| Process Tomography | Complete gate characterization | >99.5% process fidelity | Determines unitary implementation accuracy |

| Tâ‚/Tâ‚‚ Measurements | Qubit coherence times | >100 μs | Limits maximum circuit duration |

| Readout Characterization | Measurement fidelity | >98% | Affects result interpretation |

| Crosstalk Measurement | Simultaneous operation fidelity | >99% | Impacts parallel circuit execution |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful quantum computational chemistry requires both software tools and conceptual frameworks. The following table details essential "research reagents" for the field:

Table 4: Essential Tools for Quantum Computational Chemistry

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum SDKs | Qiskit (IBM), Cirq (Google), QDK (Microsoft) | Quantum circuit design and simulation | Algorithm libraries, noise models, hardware integration |

| Chemistry Packages | OpenFermion, PSI4, PySCF | Molecular Hamiltonian generation | Electronic structure interfaces, basis set transformations |

| Error Mitigation | Zero-noise extrapolation, probabilistic error cancellation | Improving result accuracy without full error correction | Compatible with NISQ hardware, various extrapolation techniques |

| Cloud Platforms | SpinQ Cloud, Azure Quantum, AWS Braket | Hardware access and simulation | Remote quantum computer access, hybrid computation |

| Visualization | Qiskit Metal, Quirk | Circuit design and analysis | Interactive circuit editing, performance analysis |

| Benchmarking | Random circuit sampling, application-oriented benchmarks | Hardware performance assessment | Standardized metrics, cross-platform comparison |

| Educational | SpinQit, Quantum Inspire | Learning and prototyping | User-friendly interfaces, tutorial content |

| MCP110 | MCP110, MF:C33H36N2O3, MW:508.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (+)-Medioresinol | (+)-Medioresinol, CAS:40957-99-1, MF:C21H24O7, MW:388.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Recent innovations like AutoSolvateWeb demonstrate the growing accessibility of advanced computational chemistry tools. This chatbot-assisted platform guides non-experts through complex quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) simulations of explicitly solvated molecules, democratizing access to sophisticated computational research tools that previously required specialized expertise [28].

Future Directions and Research Challenges

The path toward practical quantum advantage in molecular simulation faces several significant research challenges that define the current frontier:

- Identifying Hard Instances: A critical challenge is identifying concrete problem instances that are both verifiable and exhibit genuine quantum advantage. Most current quantum algorithms come with stringent criteria rarely met in commercially relevant problems, creating a gap between theoretical potential and practical application [25].

- Bridging the Knowledge Gap: A persistent sociological challenge is the knowledge gap between quantum algorithm specialists and domain experts in chemistry and pharmacology. Effective collaboration requires rare cross-disciplinary skills to translate abstract algorithmic advances into solutions for real-world problems [25].

- Early Fault-Tolerant Algorithm Design: As we enter the early fault-tolerant quantum computing era, algorithm design must evolve beyond simple metrics like circuit depth and qubit count to incorporate architecture-aware compilation and resource estimation optimized for specific error-correction approaches [25].

- Generative AI Assistance: Emerging approaches leverage generative artificial intelligence to bridge knowledge gaps between fields, potentially accelerating the discovery of quantum applications by identifying connections between quantum primitives and practical chemical problems [25].

Initiatives like the LSQI Challenge 2025 represent concerted efforts to address these challenges through international competitions that apply quantum and quantum-inspired algorithms to pharmaceutical innovation, providing access to supercomputing resources like the Gefion AI Supercomputer and fostering collaboration between quantum computing specialists and life sciences researchers [27].

The convergence of improved algorithmic frameworks, more sophisticated error mitigation techniques, and increasingly capable hardware suggests that quantum computational chemistry may be among the first fields to demonstrate practical quantum advantage. However, this achievement will require continued focus on verifiable results, careful noise characterization, and collaborative efforts that bridge the gap between quantum information science and chemical research.

Quantum computing holds transformative potential for chemical computation research, promising to simulate molecular systems with an accuracy that is fundamentally beyond the reach of classical computers. This potential stems from the core quantum properties of qubits: superposition and entanglement. Unlike classical bits, which are either 0 or 1, qubits can exist in a superposition of both states simultaneously, and entangled qubits share correlated states that can represent complex molecular wavefunctions. However, the current era of quantum computing is defined as the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era. In this context, "noise" refers to environmental disturbances that cause qubits to lose their quantum state, a process known as decoherence. For chemical research, particularly in drug development, this noise is the primary barrier to achieving quantum advantage—the point where a quantum computer outperforms the best classical supercomputers on a practical task like simulating a complex biomolecule. The central thesis of modern quantum chemical research is that understanding and mitigating this noise is not merely an engineering challenge but a prerequisite for unlocking quantum computing's potential to revolutionize the field.

Qubit Fundamentals: From Theory to Physical Reality

Principles of Operation

A qubit, the fundamental unit of quantum information, is a two-level quantum system. Its state is mathematically represented as ∣ψ⟩ = α∣0⟩ + β∣1⟩, where α and β are complex probability amplitudes satisfying |α|² + |β|² = 1 [29]. This superposition allows a qubit to explore multiple states at once, while entanglement creates powerful correlations between qubits such that the state of one cannot be described independently of the others. These properties enable quantum computers to process information in massively parallel ways [7] [29]. When a qubit is measured, its superposition collapses to a single definite state, ∣0⟩ or ∣1⟩, with probabilities |α|² and |β|² respectively. For chemical simulations, this means a quantum computer can, in principle, represent the complex, multi-configurational wavefunction of a molecule's electrons naturally, without the approximations required by classical computational methods like density functional theory [7].

Major Qubit Modalities and Hardware Landscape

Different physical platforms can implement qubits, each with distinct trade-offs in coherence time, gate fidelity, and scalability. The choice of modality directly impacts the feasibility and efficiency of running chemical computation algorithms. The table below summarizes the key qubit types and their performance characteristics as of 2025.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Qubit Modalities for Chemical Computation

| Modality | Key Players | Pros | Cons | Relevance to Chemical Computation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superconducting | IBM, Google [30] | Fast gate speeds, established fabrication [30] | Short coherence times, requires extreme cryogenics (mK temperatures) [30] [29] | Widely accessible via cloud; used for early VQE demonstrations [7] |

| Trapped-Ion | Quantinuum, IonQ [30] | High gate fidelity, long coherence, all-to-all connectivity [30] | Slower gate speeds, challenges in scaling up qubit count [30] | High accuracy beneficial for complex molecule modeling [5] |

| Neutral Atom | QuEra, Atom Computing [30] | Highly scalable, good coherence properties [30] | Complex single-atom control, developing connectivity [30] | Used in landmark 2025 demonstration of magic state distillation [5] |

| Photonic | PsiQuantum, Xanadu [29] | Room-temperature operation [30] [29] | Non-deterministic gates, challenges with photon loss [30] | Potential for large-scale, fault-tolerant systems [30] |

The Noise Threshold: Defining the Barrier to Quantum Advantage in Chemistry

In the context of chemical computation, noise is any unwanted interaction that disrupts the ideal evolution of a quantum state. The primary sources include:

- Decoherence: The loss of quantum state due to interactions with the environment (e.g., thermal vibrations, stray electromagnetic fields), which limits the computation time [29].

- Gate Errors: Imperfections in the application of quantum logic operations [30].

- Readout Errors: Mistakes in measuring the final state of the qubits [30].

For quantum chemistry algorithms, which often require deep, complex circuits to simulate electron correlations, these errors accumulate rapidly. They can corrupt the calculated molecular energy surface, making predictions of reaction pathways or binding affinities unreliable. The quantum advantage for chemistry is only achievable when the error rate per gate is below a critical threshold, allowing the computation to complete with a meaningful result before information is lost [31].

Hardware Performance and Error Metrics

The performance of quantum hardware is quantified by several key metrics beyond the raw qubit count. For chemical simulations, the following are critical:

- Gate Fidelity: The accuracy of a quantum logic operation. For fault-tolerant quantum computation using the Surface Code, gate fidelities must consistently exceed 99.99% [30].

- Coherence Time: The duration a qubit maintains its quantum state. Longer times enable deeper, more complex circuits needed for simulating large molecules [29].

- Quantum Volume (QV): A holistic metric from IBM that combines number of qubits, connectivity, and error rates to gauge a processor's overall capability [30].

Current hardware is progressing but remains below the fault-tolerant threshold. For instance, in 2025, Quantinuum's H2-1 trapped-ion processor used 56 high-fidelity, fully connected qubits to tackle problems challenging for classical supercomputers [30].

Error Mitigation and Correction: Pathways to Reliable Chemical Computation

Quantum Error Correction (QEC) Fundamentals

Quantum Error Correction is the foundational strategy for building a fault-tolerant quantum computer. QEC encodes a single piece of logical information—a logical qubit—across multiple physical qubits, allowing errors to be detected and corrected without collapsing the quantum state. The most-researched approach is the surface code, which arranges physical qubits on a lattice and uses parity checks to identify errors [30]. The overhead, however, is immense; one reliable logical qubit can require hundreds to thousands of error-prone physical qubits [7] [30]. A 2025 study from Alice & Bob on "cat qubits" demonstrated a potential 27x reduction in the physical qubits needed to simulate complex molecules like the nitrogen-fixing FeMoco, bringing the estimated requirement down from 2.7 million to about 99,000 [32]. This highlights how hardware innovations can drastically alter the resource landscape for future chemical simulations.

Exploiting Noise and Advanced Error Mitigation

Beyond traditional QEC, new strategies are emerging that reframe noise from a pure obstacle into a potential resource, or that use sophisticated software techniques to extract accurate results from noisy hardware.

- Harnessing Nonunital Noise: In a landmark 2025 study, IBM scientists demonstrated that a specific type of noise—nonunital noise, which has a directional bias (e.g., amplitude damping that pushes qubits toward their ground state)—can be harnessed to extend computation. They designed "RESET" protocols that use this noise and ancillary qubits to "cool" and recycle noisy qubits, effectively correcting errors without mid-circuit measurements, a significant technical hurdle [31].

- Zero Noise Extrapolation (ZNE): This is a key software error mitigation technique used in hybrid quantum-classical algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE). ZNE involves deliberately running a quantum circuit at multiple elevated noise levels (by scaling the number of gates, for instance) and then extrapolating the results back to the zero-noise limit to estimate what the outcome would have been on an ideal, noiseless processor [5].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of a VQE algorithm incorporating ZNE for mitigating errors in chemical energy calculations.

Diagram: VQE Workflow with ZNE. This hybrid quantum-classical algorithm uses a quantum processing unit (QPU) to estimate molecular energy and a classical optimizer to minimize it. ZNE is applied during QPU execution to mitigate errors.

The IBM RESET protocol, which leverages nonunital noise, can be visualized as a three-stage process for recycling qubits within a computation, as shown below.

Diagram: RESET Protocol Stages. This protocol uses nonunital noise to cool and reset ancillary qubits, refreshing the computational qubits without measurement.

Experimental Protocols for Chemical Computation on Noisy Hardware

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) Protocol

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver is the leading near-term algorithm for quantum chemistry on NISQ devices. Its purpose is to find the ground-state energy of a molecule, a key determinant of its stability and reactivity [30] [33]. The following detailed protocol outlines the steps for a VQE calculation, incorporating error mitigation.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions: Key Components for a VQE Experiment

| Component | Type | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Processing Unit (QPU) | Hardware | Executes the parameterized quantum circuits to prepare trial molecular wavefunctions and measure their energy. |

| Classical Optimizer | Software | Adjusts the parameters of the quantum circuit to minimize the measured energy (e.g., using gradient-based methods). |

| Molecular Hamiltonian | Software | The mathematical representation of the molecule's energy, translated into a form (Pauli strings) the quantum computer can measure. |

| Parameterized Ansatz | Software (Circuit) | A quantum circuit template that prepares a trial state for the molecule. Its structure is crucial for accuracy and trainability. |

| Error Mitigation Toolkit (e.g., ZNE) | Software | A set of protocols applied to the raw QPU results to reduce the impact of noise and improve the accuracy of the energy estimate. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Problem Formulation: Define the target molecule and its geometry. Using a classical computer, generate the molecular Hamiltonian, H, in the second quantized form and map it to a qubit representation using a transformation like Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev.

- Ansatz Selection and Initialization: Choose an appropriate parameterized ansatz circuit. Common choices for chemical problems include the Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) ansatz or hardware-efficient ansatzes. Initialize the parameters, θ, to a starting guess.

- Quantum Execution Loop: a. The quantum processor prepares the trial state ∣ψ(θ)⟩ by executing the ansatz circuit with the current parameters. b. The expectation value ⟨ψ(θ)∣H∣ψ(θ)⟩ is measured. This is done by decomposing H into a sum of Pauli terms and measuring each term separately. To mitigate errors, this step employs techniques like ZNE: the circuit is run at multiple scaled noise levels (e.g., by stretching gate pulses or inserting identity gates), and the results are extrapolated to the zero-noise limit.

- Classical Optimization: The computed energy E(θ) is fed to a classical optimizer. The optimizer evaluates the cost function (the energy) and determines a new set of parameters θ' to lower the energy.

- Iteration and Convergence: Steps 3 and 4 are repeated in a closed loop until the energy E(θ) converges to a minimum, which is reported as the calculated ground-state energy.

A simplified code structure for a VQE experiment with ZNE, as demonstrated in 2025, is shown below [5].

Application to Industry-Relevant Molecules

VQE and related algorithms have progressed from simulating simple diatomic molecules (Hâ‚‚, LiH) to more complex systems, signaling a path toward industrial utility.

- Iron-Sulfur Clusters & Metalloenzymes: IBM applied a hybrid algorithm to estimate the energy of an iron-sulfur cluster, while researchers have set their sights on molecules like cytochrome P450 (crucial for drug metabolism) and the iron-molybdenum cofactor (FeMoco) (central to nitrogen fixation) [7] [32].

- Protein-Ligand Interactions and Folding: A 16-qubit computer aided in finding potential drugs that inhibit the KRAS protein, linked to cancers. In another demonstration, IonQ and Kipu Quantum simulated the folding of a 12-amino-acid chain, the largest such demonstration on quantum hardware to date [7]. These applications, while still not claiming quantum advantage, represent critical stepping stones toward simulating full biological systems.