Noise-Aware Quantum Circuit Learning: Advancing Molecular Energy Calculations for Drug Discovery

Accurately calculating molecular energies is crucial for advancing drug discovery, yet remains a significant challenge for classical computers.

Noise-Aware Quantum Circuit Learning: Advancing Molecular Energy Calculations for Drug Discovery

Abstract

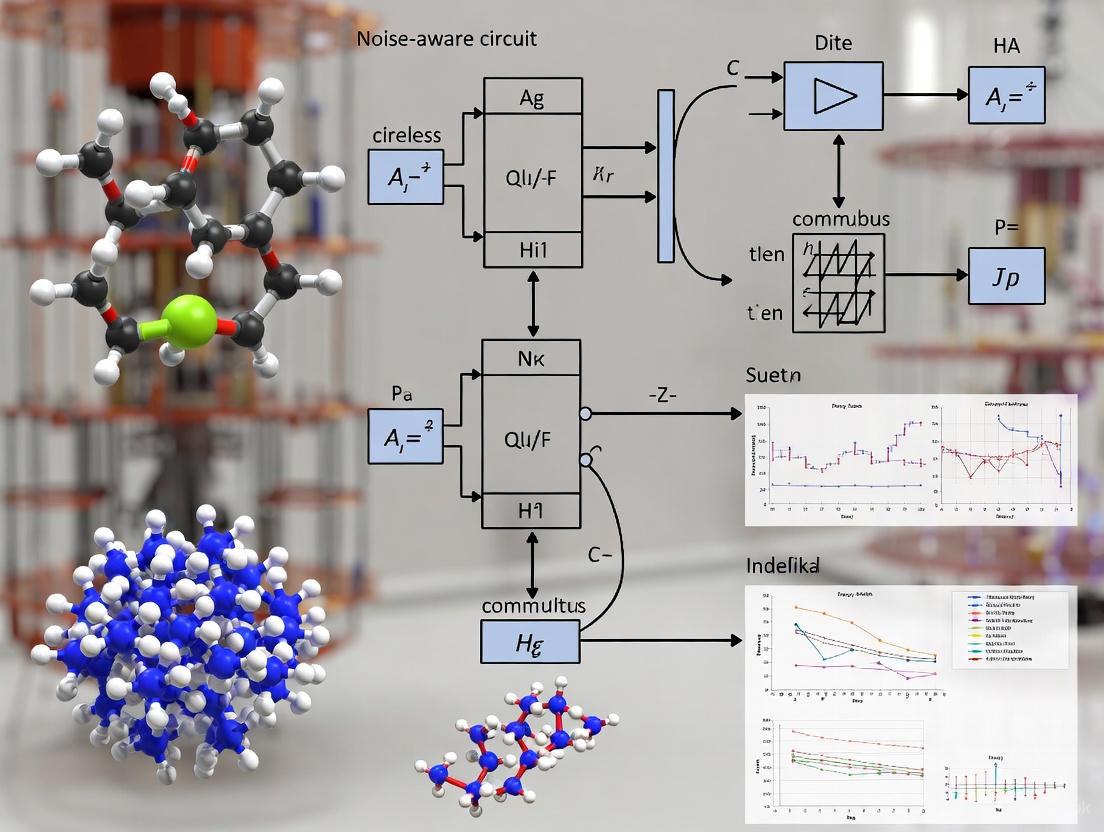

Accurately calculating molecular energies is crucial for advancing drug discovery, yet remains a significant challenge for classical computers. This article explores the transformative potential of noise-aware quantum circuit learning to overcome the limitations of current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware. We provide a comprehensive overview of foundational principles, including the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm and the impact of quantum noise. The article details cutting-edge methodological approaches like hybrid quantum-neural frameworks and machine learning-enhanced optimizers that improve accuracy and resilience. We examine practical troubleshooting strategies and optimization techniques for error mitigation and resource management. Finally, we present validation case studies across various molecular systems and comparative analyses with classical computational chemistry methods, highlighting both current capabilities and future pathways for practical quantum computing applications in biomedical research.

Quantum Computing Meets Molecular Simulation: Foundations of Noise-Aware Algorithms

The pursuit of understanding and predicting chemical behavior through the computation of molecular energies—the electronic structure problem—is a cornerstone of modern chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery. At its heart lies the fundamental challenge of solving the Schrödinger equation for systems with many interacting electrons. The dimension of the Hilbert space for an active space of 50 electrons in 36 orbitals is approximately 3.61 × 10¹â·, making exact diagonalization impossible for all but the smallest systems [1]. This combinatorial explosion of quantum states is the primary reason molecular energy calculation is classically hard. While classical methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) have become workhorses, they often become computationally prohibitive for large systems or fail for problems with strong electronic correlation, such as the simulation of iron-sulfur clusters in proteins [1].

Framed within research on noise-aware circuit learning, this article details how emerging hybrid quantum-classical and machine learning (ML) approaches are creating new paradigms for overcoming these classical bottlenecks. By leveraging physical insights and innovative algorithms, these methods aim to achieve chemical accuracy with resilience to the inherent noise in modern quantum devices.

Current Research Frontiers: Bridging Accuracy and Efficiency

Recent advances are breaking new ground by integrating classical high-performance computing (HPC), quantum processing, and machine learning. The table below summarizes key quantitative results from cutting-edge studies, highlighting the progress in tackling the electronic structure problem.

Table 1: Recent Quantitative Benchmarks in Electronic Structure Calculation

| Method / Model | System Studied | Key Result / Accuracy | Computational Advantage / Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-loop Quantum-HPC [1] | [4Fe-4S] cluster (54eâ», 36 orbitals) | Energy: -326.635 Eh(Between RHF and CISD) | Largest quantum-classical computation; 72 qubits + 152,064 classical nodes. |

| NextHAM (Deep Learning) [2] | Materials-HAM-SOC (17k structures, 68 elements) | Hamiltonian error: 1.417 meV; SOC blocks: sub-μeV scale. | Achieves DFT-level precision with dramatically improved computational efficiency. |

| pUNN (Hybrid Quantum-Neural) [3] [4] | Nâ‚‚, CHâ‚„, cyclobutadiene isomerization | "Near-chemical accuracy" | Noise resilience demonstrated on a superconducting quantum processor. |

| OMol25-Trained UMA-S (ML Potential) [5] | Organometallic Reduction Potentials (OMROP set) | MAE: 0.262 V | Accurate for charge-related properties of organometallics without explicit Coulombic physics. |

| Noise-aware ML-VQE Optimizer [6] | H₂ (1-2 qubits), H₃ (3 qubits), HeH⺠(4 qubits) | Reaches chemical accuracy "much faster" than conventional optimizers. | Resilient to coherent errors; uses intermediate VQE data for training. |

Analysis of Research Directions

The data in Table 1 reveals three distinct but complementary research trajectories:

- Scalable Quantum-Classical Integration: The work on iron-sulfur clusters demonstrates a pathway to scale quantum-classical workflows to problems of real-world biological relevance, orchestrating a massive number of classical nodes to complement quantum sampling [1].

- Generalizable Machine Learning Potentials: The NextHAM model and OMol25-trained potentials show that ML models, when trained on extensive and diverse datasets, can achieve high accuracy across a wide range of elements and properties, offering a massive speedup over traditional DFT [7] [2] [5].

- Noise-Resilient Hybrid Algorithms: The pUNN and noise-aware VQE optimizer represent a class of algorithms specifically designed for the current era of noisy quantum devices. They incorporate neural networks to enhance expressiveness or use ML to correct for device-specific noise, thereby improving accuracy and convergence [6] [3].

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for two key experiments cited, illustrating the workflow for a hybrid quantum-neural algorithm and a large-scale ML Hamiltonian prediction.

Protocol 1: Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunction (pUNN) Energy Calculation

This protocol describes the procedure for computing molecular energies using the paired Unitary Coupled-Cluster with Neural Networks (pUNN) method, which combines a quantum circuit with a classical neural network for noise-resilient calculations [3] [4].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for pUNN Experiment

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| pUCCD Ansatz | A parameterized quantum circuit that learns the molecular wavefunction within the seniority-zero subspace. Requires N qubits for a system with N electron pairs. |

| Ancilla Qubits (N) | N classically simulated ancilla qubits used to expand the Hilbert space, allowing the neural network to describe configurations outside the seniority-zero subspace. |

| Perturbation Circuit (R_y(0.2)) | A low-depth circuit of single-qubit rotation gates applied to ancilla qubits to divert the state from the initial reference, facilitating exploration of a broader Hilbert space. |

| Entanglement Circuit (Ê) | A circuit of N parallel CNOT gates, each entangling an original qubit with a corresponding ancilla qubit, creating necessary correlations in the expanded 2N-qubit space. |

| Neural Network Operator | A non-unitary, post-processing operator that modulates the quantum state. It is a classical neural network that takes bitstrings as input and outputs coefficients bâ‚–â±¼. |

Procedure:

State Preparation:

- Prepare the initial quantum state |ψ⟩ using the pUCCD ansatz on N qubits.

- Expand the Hilbert space by entangling the N system qubits with N ancilla qubits (initialized to |0⟩) using the entanglement circuit Ê, which consists of N parallel CNOT gates. The resulting state is |Φ⟩ = Ê(|ψ⟩ ⊗ |0⟩).

- Apply the shallow perturbation circuit, composed of single-qubit Ry gates with a small angle (e.g., 0.2 radians), to the ancilla qubits. This produces a state |ϕ⟩ that is a slight deviation from |0⟩.

Neural Network Processing:

- For each computational basis state |k⟩ ⊗ |j⟩ in the expanded 2N-qubit space, feed the binary representation of the bitstring into the neural network.

- The neural network, comprising L dense layers with ReLU activation and a width proportional to N, outputs a coefficient bâ‚–â±¼.

- Apply a particle number conservation mask m(k,j) to the output bâ‚–â±¼ to eliminate configurations that do not conserve the number of spin-up and spin-down electrons.

Wavefunction Construction:

- The final hybrid wavefunction is constructed as |Ψ⟩ = Σₖⱼ bₖⱼ ⟨k| ⟨j| Ê (|ψ⟩ ⊗ |ϕ⟩) |k⟩|j⟩.

- Note that |Ψ⟩ is not normalized.

Energy Estimation:

- Compute the expectation value of the Hamiltonian Ĥ using the formula E = ⟨Ψ|Ĥ|Ψ⟩ / ⟨Ψ|Ψ⟩.

- The authors designed an efficient algorithm to compute these expectations without resorting to full quantum state tomography, which is a key innovation for scalability. The specific measurement protocol is detailed in the supplementary information of the original paper [3].

Protocol 2: Universal Deep Learning for Hamiltonian Prediction (NextHAM)

This protocol outlines the steps for training the NextHAM model, a deep learning framework designed to predict electronic-structure Hamiltonians with high accuracy and generalization across the periodic table [2].

Procedure:

Dataset Curation (Materials-HAM-SOC):

- Generate a diverse set of material structures (e.g., 17,000 as in the benchmark).

- Employ DFT software to perform high-quality calculations for each structure. This includes using high-fidelity pseudopotentials with many valence electrons and atomic orbital basis sets (e.g., up to 4s2p2d1f orbitals).

- Explicitly incorporate spin-orbit coupling (SOC) effects in the DFT calculations.

- Extract and store the final converged Hamiltonian, H^(T), for each structure.

Input Feature Engineering:

- For each material structure, efficiently construct the zeroth-step Hamiltonian, H^(0), from the initial electron density (e.g., the sum of isolated atomic charge densities) without performing matrix diagonalization.

- Use H^(0) as a physically informed input descriptor for the neural network. This provides a rich prior of the system's electronic structure.

Model Training with a Correction Approach:

- Define the regression target for the neural network as the correction term, ΔH = H^(T) - H^(0), rather than the full Hamiltonian H^(T). This simplifies the learning task.

- Implement a neural Transformer architecture that strictly enforces E(3)-symmetry (invariance to translation, rotation, and inversion) while maintaining high non-linear expressiveness.

- Train the model using a joint optimization loss function that ensures accuracy in both real space (R-space) and reciprocal space (k-space). This prevents error amplification and the appearance of unphysical "ghost states" in the resulting band structures.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details key resources that are foundational for research in modern electronic structure calculations, particularly for those leveraging machine learning and quantum computing.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources and Datasets

| Resource | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset [7] [8] [9] | An unprecedented open dataset of over 100 million molecular simulations at the ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD level of theory. It provides extensive, chemically diverse data for training generalizable ML interatomic potentials (MLIPs). |

| OMol25 Electronic Structures [9] | A ~500 TB subset of OMol25 containing raw DFT outputs, electronic densities, wavefunctions, and molecular orbital information from over 4 million calculations. Enables development of physics-informed ML models. |

| Architector Software [8] | A computational tool for predicting the 3D structures of metal complexes, including challenging f-block elements. It was instrumental in generating a significant portion of the metal complexes in the OMol25 dataset. |

| Zeroth-Step Hamiltonian (Hâ½â°â¾) [2] | A physical quantity constructed from the initial electron density of a DFT calculation. It serves as an informative input feature and initial estimate for deep learning models like NextHAM, simplifying the Hamiltonian prediction task. |

| ASSYST Method [10] | A strategy (Automated Small SYmmetric Structure Training) for generating unbiased, systematically extendable training data for MLIPs. It explores the full space of random crystal structures with few atoms, enabling the creation of transferable potentials with minimal human input. |

| Silibinin | Silibinin, CAS:1265089-69-7, MF:C25H22O10, MW:482.4 g/mol |

| DL-alpha-Tocopherol | Alpha-Tocopherol |

The electronic structure problem remains a classically hard challenge due to the exponential scaling of its underlying quantum complexity. However, the protocols and resources detailed herein demonstrate a clear pathway forward. By integrating noise-aware quantum algorithms, physically informed machine learning models, and vast, high-quality datasets, researchers are constructing a robust toolkit to achieve chemical accuracy for increasingly complex and scientifically relevant molecular systems. These hybrid approaches, which leverage the respective strengths of quantum and classical computing, are poised to significantly accelerate discovery in drug development, materials science, and beyond.

Theoretical Foundation and Core Algorithm

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed to approximate the ground state energy of quantum systems, particularly molecular Hamiltonians, which is a fundamental task in quantum computational chemistry and materials science [11] [12]. This algorithm has emerged as a leading approach for leveraging current noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices by combining the quantum computer's ability to prepare and measure complex quantum states with classical computational resources for parameter optimization [12] [13]. The fundamental principle underpinning VQE is the variational principle of quantum mechanics, which states that for any trial wavefunction ( |\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle ), the expectation value of the Hamiltonian ( \hat{H} ) provides an upper bound to the true ground state energy ( E_0 ) [12] [14]:

[ E(\vec{\theta}) = \langle\psi(\vec{\theta})|\hat{H}|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle \ge E_0 ]

The electronic structure Hamiltonian, under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, captures the kinetic energies of electrons and nuclei alongside their Coulombic interactions [14]. To execute this on a quantum computer, the fermionic Hamiltonian is mapped to a qubit operator using transformations such as Jordan-Wigner or parity mapping, expressing it as a weighted sum of Pauli strings [11] [12]:

[ \hat{H} = \sumi hi \hat{P}i, \quad \text{where } \hat{P}i \in {I, X, Y, Z}^{\otimes N} ]

The VQE protocol iteratively minimizes the energy expectation value through a cyclic process between quantum and classical processors [11] [12]:

- Ansatz Preparation: A parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) ( U(\vec{\theta}) ) prepares the trial state ( |\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle ) from an initial state, often the Hartree-Fock state [11].

- Quantum Measurement: The quantum device measures the expectation values of each Pauli term ( \langle \hat{P}_i \rangle ) in the Hamiltonian [11].

- Classical Optimization: A classical optimizer computes the total energy ( E(\vec{\theta}) = \sumi hi \langle \hat{P}_i \rangle ) and updates the parameter vector ( \vec{\theta} ) to minimize the energy [11] [12].

- Iteration and Convergence: Steps 2 and 3 are repeated until the energy converges to a minimum, providing an estimate for the ground state energy [11].

Key Components and Methodological Variations

Variational Ansätze: Balancing Expressivity and Hardware Feasibility

The choice of the parameterized quantum circuit, or ansatz, is critical as it determines the algorithm's expressiveness, convergence behavior, and hardware compatibility [12]. Two primary categories have emerged:

- Chemistry-Inspired Ansätze: The Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) family, particularly UCC with Single and Double excitations (UCCSD), is a predominant choice [11] [12]. It operates on a Hartree-Fock reference state using exponentials of excitation operators derived from classical computational chemistry, ensuring the construction of physically meaningful states [12]. While highly accurate, its circuit depth can be demanding for current hardware [13].

- Hardware-Efficient Ansätze: These are designed with low-depth circuits using a device's native gate set and connectivity, such as the

EfficientSU2ansatz in Qiskit [11] [13]. They prioritize reduced execution time and lower susceptibility to noise but may not conserve physical symmetries and can suffer from barren plateaus—regions where gradients vanish exponentially with system size [12] [13].

Table 1: Comparison of Common VQE Ansätze

| Ansatz Class | Key Features | Typical Limitations | Example Molecules Tested |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemistry-Inspired (e.g., UCCSD) | Exploits physical structure; physically motivated | High circuit depth; scalability | Hâ‚‚, LiH, BeHâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚O [12] [13] |

| Hardware-Efficient (e.g., EfficientSU2) | Low depth; device-tailored | May break symmetries; barren plateaus | Aluminum clusters (Alâ», Alâ‚‚, Al₃â») [13] |

| Adaptive (e.g., ADAPT-VQE, GGA-VQE) | Circuit grown iteratively on demand; resource-efficient | Optimization overhead; measurement intensity | Hâ‚‚O, LiH, 25-spin Ising model [15] [12] |

Classical Optimizers and Noise Resilience

The classical optimizer's role is to navigate the parameter landscape, a task complicated by noise and the barren plateau problem. Commonly used optimizers include COBYLA (gradient-free), SLSQP (gradient-based), and SPSA [6] [11] [13]. A key challenge in the NISQ era is noise resilience. VQE exhibits some inherent resilience to coherent noise, as parameters can often rotate to compensate for such errors [6]. Furthermore, algorithmic innovations like the Greedy Gradient-Free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE) enhance noise tolerance by constructing the ansatz iteratively, determining the optimal angle for each new gate with only a handful of measurements and locking it in, thus avoiding costly global re-optimization loops [15].

Advanced Noise-Aware Algorithmic Frameworks

Machine Learning-Enhanced VQE Optimisation

Recent research focuses on making VQE optimization faster and more robust to noise by integrating machine learning (ML). Karim et al. propose a supervised learning approach where a neural network is trained on intermediate parameter and measurement data from previous VQE runs [6] [16]. The model learns the relationship between circuit parameters, measurement outcomes, and the device's specific noise characteristics [6] [16]. Once trained, it can predict optimal parameters for new, related Hamiltonians, drastically reducing the number of iterative steps required. This method has demonstrated the ability to achieve chemically accurate energies for H₂, H₃, and HeH⺠on IBM quantum devices, showing particular resilience to coherent errors when trained on noisy devices [6] [16].

Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunctions

Another innovative framework combines shallow quantum circuits with classical neural networks to create a powerful, noise-resilient hybrid wavefunction ansatz. The pUNN (paired Unitary Coupled-Cluster with Neural Networks) method uses a low-depth paired UCCD (pUCCD) quantum circuit to capture the quantum phase structure in the seniority-zero subspace, which is augmented by a deep neural network that accounts for contributions from unpaired configurations [3] [4]. This approach retains the low qubit count and shallow circuit depth of pUCCD while achieving accuracy comparable to high-level classical methods like CCSD(T) [3] [4]. It includes an efficient measurement protocol to compute energy expectations without quantum state tomography, and has been validated on a superconducting quantum computer for the isomerization of cyclobutadiene, demonstrating high accuracy and significant noise resilience [3] [4].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Standard VQE Protocol for Molecular Energy Calculation

This protocol outlines the steps to compute the ground state energy of a molecule, such as Hâ‚‚, using the Qiskit ecosystem [11].

- Step 1: Define Molecule and Geometry. Specify the molecular structure. For Hâ‚‚, a common starting geometry places atoms at (0, 0, 0) and (1.623 Ã…, 0, 0) [11].

- Step 2: Generate Electronic Structure Problem. Use a quantum chemistry package like PySCF with a specified basis set (e.g., STO-3G) to compute molecular integrals. The

FreezeCoreTransformercan be applied to simplify the problem by freezing core orbitals [11] [13]. - Step 3: Map to Qubit Hamiltonian. Transform the fermionic Hamiltonian into a qubit operator using a mapper such as

ParityMapperorJordanWignerMapper[11] [14]. - Step 4: Prepare Ansatz Circuit. Initialize the Hartree-Fock state and select an ansatz. The UCCSD ansatz is often chosen for chemical accuracy, while

EfficientSU2provides a hardware-efficient alternative [11]. - Step 5: Configure Optimizer and Estimator. Choose a classical optimizer (e.g.,

SLSQPorCOBYLA) and an estimator to compute expectation values [11]. - Step 6: Run VQE and Compute Energy. Execute the VQE algorithm with the qubit Hamiltonian. The result is the estimated ground state energy [11].

- Step 7: Validate with Exact Solver. Compare the VQE result with the exact ground state energy from a classical solver like

NumPyMinimumEigensolverto assess accuracy [11].

VQE Algorithm Workflow

Protocol for Machine Learning-Enhanced VQE Optimisation

This protocol details the ML-based parameter prediction method from Karim et al. [6] [16].

- Step 1: Initial VQE Data Generation. Run standard VQE optimizations (e.g., using COBYLA) for the target molecule at multiple geometries. Record all intermediate parameters, corresponding expectation values for each Pauli string, and the final optimized parameters [6].

- Step 2: Data Augmentation and Preprocessing. Reuse intermediate measurements to exponentially grow the training set. The input vector for the neural network is the concatenation of the Hamiltonian coefficients (Pauli vector), the ansatz angles, and the measured expectation values. The output vector is the difference between the intermediate angles and the final optimal angles [6].

- Step 3: Neural Network Training. Train a feedforward neural network with ReLU activation functions on the prepared dataset. The network architecture typically starts with the input size and halves the number of neurons in each subsequent layer [6].

- Step 4: Optimal Parameter Prediction. For a new molecular configuration, the trained network takes the Hamiltonian Pauli vector and initial circuit measurements as input and directly predicts the optimal parameters, bypassing the need for many iterative steps [6] [16].

Benchmarking and Performance Analysis

Systematic benchmarking is crucial for evaluating VQE performance under various parameters. Studies on small aluminum clusters (Alâ», Alâ‚‚, Al₃â») have analyzed the impact of optimizers, circuit types, basis sets, and noise models [13]. Results show that VQE can achieve percent errors consistently below 0.2% compared to classical benchmarks when parameters are well-optimized [13].

Table 2: Benchmarking VQE Performance on Molecular Systems

| Molecule | Number of Qubits | Ansatz Type | Key Result / Energy Accuracy | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ [6] [12] | 1-2 | Simplified UCCSD / Hardware-efficient | Chemical accuracy achieved | ML-optimiser reduced iterations [6] |

| HeH⺠[6] | 4 | Simplified UCCSD | Chemically accurate energies predicted | ML-optimiser trained on modelled data [6] |

| Hâ‚‚O [15] | - | GGA-VQE | ~2x more accurate than ADAPT-VQE under shot noise | Simulation under realistic noise conditions [15] |

| Aluminum Clusters [13] | - | EfficientSU2 | Percent errors < 0.2% | Quantum-DFT embedding framework [13] |

| Cyclobutadiene [3] [4] | - | pUNN (Hybrid quantum-neural) | High accuracy for isomerization reaction | Validated on superconducting quantum processor [3] |

| 25-spin Ising Model [15] | 25 | GGA-VQE | >98% state fidelity | Real 25-qubit trapped-ion computer (IonQ Aria) [15] |

Table 3: Key Research Tools for VQE Implementation

| Tool / Resource | Type / Category | Primary Function in VQE Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| PySCF [6] [11] [13] | Classical Computational Chemistry Package | Generates the molecular electronic structure problem and one-/two-electron integrals. |

| Qiskit Nature [11] [13] | Quantum Computing Software Framework | Provides drivers, transformers (e.g., FreezeCoreTransformer), and mappers to convert chemical problems into qubit Hamiltonians. |

| UCCSD Ansatz [11] [12] | Chemistry-Inspired Quantum Circuit | Parameterized circuit that prepares a trial wavefunction strongly correlated with the chemical ground state. |

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (e.g., EfficientSU2) [11] [13] | Hardware-Native Quantum Circuit | Low-depth, parameterized circuit designed for efficient execution on specific NISQ device architectures. |

| COBYLA / SLSQP Optimizers [6] [11] [13] | Classical Optimiser | Iteratively updates variational parameters in the quantum circuit to minimise the energy expectation value. |

| Statevector / Noise Simulators [13] | Quantum Simulator | Mimics an ideal or noisy quantum computer for algorithm development and testing in a controlled environment. |

| NumPyMinimumEigensolver [11] | Exact Diagonalisation Solver | Provides a classical benchmark for the true ground state energy within the active space for performance validation. |

The term Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) was coined by John Preskill to describe the current generation of quantum processors [17]. This era is characterized by quantum devices containing from approximately 50 to 1000 physical qubits that operate without full fault tolerance [18] [17]. These processors are inherently "noisy" – they suffer from significant decoherence, gate errors, and measurement errors that accumulate during computation, severely limiting the depth and complexity of quantum algorithms that can be reliably executed [17].

For researchers focused on noise-aware circuit learning for molecular energy calculations, the NISQ landscape presents a critical challenge: achieving chemically accurate results with quantum hardware that has fundamental limitations. Current NISQ devices typically exhibit gate fidelities around 99-99.5% for single-qubit operations and 95–99% for two-qubit gates [17]. While impressive, these error rates impose severe constraints, with quantum circuits generally limited to approximately 1,000 gates before noise overwhelms the computational signal [17]. This directly impacts the feasibility of variational quantum algorithms for molecular simulations, necessitating specialized error mitigation strategies and noise-resilient algorithmic approaches.

Quantitative Analysis of NISQ Limitations

The table below summarizes the key physical and logical resource constraints that define the NISQ environment, particularly relevant for molecular energy calculation experiments.

Table 1: Key NISQ Resource Constraints and Their Impact on Molecular Simulations

| Resource Type | Current NISQ Limitations | Impact on Molecular Energy Calculations |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Qubits | 50 - 1000+ qubits [17] | Limits system size (number of spin orbitals) that can be simulated. |

| Gate Fidelity | 95-99% for 2-qubit gates [17] | Accumulated errors degrade solution accuracy, especially in deep circuits. |

| Coherence Time | Typically microseconds to milliseconds | Limits maximum circuit depth and number of operations [18]. |

| Connectivity | Limited qubit connectivity (topology-dependent) | Increases circuit depth due to required SWAP operations, raising error rates. |

| Algorithmic Circuit Depth | ~1,000 gates before noise dominates [17] | Constrains complexity of variational ansatz for molecular Hamiltonians. |

Different quantum noise channels affect NISQ hardware uniquely. Understanding these is crucial for developing noise-aware circuit learning protocols. The table below quantifies the impact of various noise channels on different hybrid quantum neural network (HQNN) architectures, providing a benchmark for expected performance degradation in quantum machine learning approaches to molecular simulations.

Table 2: Impact of Quantum Noise Channels on HQNN Performance (Image Classification Task Benchmark) [19]

| Noise Channel | Impact on Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN) | Impact on Quantum Convolutional Neural Network (QCNN) | Impact on Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase Flip | High robustness; minimal performance degradation [19] | Moderate robustness; significant accuracy drop | Low robustness; severe performance loss |

| Bit Flip | High robustness; maintains >80% relative accuracy [19] | Low robustness; <50% relative accuracy | Variable robustness; architecture-dependent |

| Phase Damping | High robustness; most stable across probabilities [19] | Moderate robustness | Low to moderate robustness |

| Amplitude Damping | Moderate to high robustness [19] | Low robustness | Low robustness |

| Depolarization Channel | Greatest overall robustness across various probabilities [19] | Significant performance degradation | Performance degradation comparable to QCNN |

Experimental Protocols for Molecular Energy Calculations

Protocol 1: Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunction (pUNN) Approach

The pUNN (paired Unitary Coupled-Cluster with Neural Networks) method represents a state-of-the-art, noise-aware framework for molecular energy calculations on NISQ devices [3]. This protocol combines a quantum circuit with a classical neural network to achieve high accuracy while maintaining resilience to hardware noise.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

State Preparation (Quantum Circuit):

- Initialize the system using the paired Unitary Coupled-Cluster with double excitations (pUCCD) ansatz to represent the molecular wavefunction in the seniority-zero subspace [3].

- This approach requires only N qubits for the initial state and achieves linear circuit depth, making it NISQ-appropriate [3].

Hilbert Space Expansion:

Neural Network Processing:

- Apply a non-unitary post-processing operator represented by a classical neural network [3].

- The neural network accepts bitstrings |k⟩⊗|j⟩ as input and outputs coefficients bkj through a feedforward architecture with:

- Binary embedding of input bitstrings

- L dense layers with ReLU activation (L = N-3)

- 2KN neurons per hidden layer (K is a tunable integer, typically K=2)

- Particle number conservation mask applied to outputs [3]

Energy Expectation Calculation:

- Compute the energy expectation value using an efficient measurement protocol that avoids quantum state tomography [3].

- The measurement strategy is designed to minimize overhead while maintaining accuracy in the presence of noise.

Noise Resilience Features: This hybrid approach demonstrates significant resilience to noise on superconducting quantum processors, as validated through calculations of the isomerization reaction of cyclobutadiene, a challenging multi-reference system [3].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning Enhanced Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE)

This protocol leverages classical machine learning to accelerate and noise-stabilize the standard VQE algorithm, which is a cornerstone for molecular energy calculations on NISQ devices [6].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Initial Data Generation:

- Perform multiple standard VQE runs for molecular systems at various geometries (e.g., along a potential energy surface) using classical optimizers like COBYLA [6].

- Collect all intermediate circuit parameters, measurement outcomes, and corresponding energies during optimization - data typically discarded in conventional VQE [6].

Neural Network Training:

- Architecture: Feedforward neural network with ReLU activation, 4 layers, descending neuron count (halving each layer) from input to output size [6].

- Input: Concatenated vector of Hamiltonian coefficients (Pauli vector), current circuit angles, and expectation value measurements [6].

- Output: Predicted optimal parameter update or final angles [6].

- Training data is labeled using known optimal angles from converged VQE runs or analytical solutions [6].

Data Augmentation:

Deployment for Molecular Energy Prediction:

Validation: This approach has demonstrated success in predicting ground state energies for H₂ (1-2 qubits), H₃ (3 qubits), and HeH⺠(4 qubits) on IBM quantum devices, achieving chemical accuracy with significantly fewer iterations than conventional VQE [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Noise-Aware Molecular Energy Calculations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Molecular Energy Research |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Computational Chemistry Packages | PySCF [6] | Generate molecular Hamiltonians and reference calculations using classical methods (e.g., HF, CCSD(T)). |

| Quantum Algorithm Frameworks | Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) [6] [17] | Hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for finding molecular ground states on NISQ hardware. |

| Quantum Neural Network Architectures | Quanvolutional Neural Networks (QuanNN) [19] | Provides noise resilience through architectural design; most robust to various quantum noise channels. |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE), Symmetry Verification [17] | Post-processing techniques to infer noiseless results from noisy quantum computations. |

| Classical Machine Learning Models | Feedforward Neural Networks [6], E(3)-equivariant Graph Neural Networks [20] | Accelerate optimization, predict circuit parameters, and enhance wavefunction representations. |

| Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunction Methods | pUNN framework [3] | Combines quantum circuits with neural networks to achieve chemical accuracy with noise resilience. |

| beta-Damascenone | beta-Damascenone, CAS:23726-93-4, MF:C13H18O, MW:190.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Furancarboxylic acid | 2-Furoic Acid|Furan-2-carboxylic Acid Supplier | High-purity 2-Furoic Acid for research. Used in pharmaceutical, flavor, and materials science studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

The Quantum Variational Principle provides the fundamental mathematical basis for determining the ground-state energy of quantum systems, establishing that the expectation value of the Hamiltonian in any trial state will always be greater than or equal to the true ground state energy. This principle enables the development of hybrid quantum-classical algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), which have emerged as promising tools for molecular energy estimation on noisy quantum devices. Within drug development, accurately predicting molecular energies and binding affinities is crucial for rational drug design, yet this remains computationally challenging for classical computers. The current era of noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices necessitates innovative approaches that combine the structural advantages of quantum circuits with noise-resilient classical machine learning techniques to achieve chemically accurate results despite hardware imperfections.

Core Mathematical Principles

Foundational Theory

The quantum variational principle states that for any trial wavefunction (|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle) parameterized by angles (\vec{\theta}), the expectation value of the Hamiltonian (\hat{H}) provides an upper bound to the true ground state energy (E_0):

[ E[\psi(\vec{\theta})] = \frac{\langle\psi(\vec{\theta})|\hat{H}|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle}{\langle\psi(\vec{\theta})|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle} \geq E_0 ]

This inequality enables a variational approach where parameters (\vec{\theta}) are optimized to minimize (E[\psi(\vec{\theta})]), progressively tightening the upper bound on (E_0). For molecular systems, the electronic Hamiltonian is mapped to qubit operators via Jordan-Wigner or parity transformations, expressing (\hat{H}) as a weighted sum of Pauli strings:

[ \hat{H} = \sumi hi \hat{P}_i ]

where (hi) are coefficients and (\hat{P}i) are Pauli operators. The VQE algorithm implements this principle through a parameterized quantum circuit that prepares trial states, with measurement outcomes processed by a classical optimizer in a hybrid loop [6].

Noise Resilience Properties

The variational approach exhibits inherent resilience to certain types of noise, particularly coherent errors that effectively rotate the state within the parameter space. Since the algorithm cares only about finding the correct final state rather than the specific path taken, noise that can be compensated through parameter adjustments is naturally corrected during optimization [6]. This property makes VQE particularly valuable for current noisy quantum devices where gate imperfections and decoherence remain significant challenges.

Table: Types of Noise in Quantum Computation and Variational Mitigation Strategies

| Noise Type | Physical Origin | Impact on VQE | Mitigation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coherent Noise | Calibration errors, systematic gate imperfections | Parameter rotation | Naturally compensated during optimization [6] |

| Incoherent Noise | Decoherence, thermal relaxation | State corruption | Error mitigation, machine learning correction [6] [21] |

| Measurement Noise | Readout errors | Expectation value bias | Measurement error mitigation, repeated sampling |

| Non-unital Noise | Amplitude damping | Distribution concentration | Algorithm-specific resilience [22] |

Implementation Strategies for Molecular Energy Estimation

Machine Learning-Enhanced VQE

Recent advances have demonstrated that machine learning models can significantly accelerate VQE convergence by leveraging intermediate optimization data. Karim et al. developed a noise-aware ML-VQE optimizer that uses a feedforward neural network trained on intermediate parameter and measurement data from previous VQE runs to predict optimal circuit parameters for related Hamiltonians [6]. This approach demonstrates dual advantages: accelerated convergence and inherent noise resilience when trained on noisy devices.

The neural network architecture takes as input the Hamiltonian coefficients, current circuit parameters, and corresponding expectation values, and outputs updates toward optimal parameters. Through data augmentation techniques that reuse intermediate measurements, the training set grows exponentially with each VQE run, enhancing learning efficiency [6]. Implementation results on IBM quantum devices for H₂, H₃, and HeH⺠molecules show this technique achieves chemical accuracy with significantly fewer iterations than conventional optimizers like COBYLA.

Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunctions

Li et al. developed the pUNN (paired Unitary coupled-cluster with Neural Networks) framework that combines efficient quantum circuits with neural networks to represent molecular wavefunctions [3] [4]. This approach employs a paired Unitary Coupled-Cluster with double excitations (pUCCD) circuit to capture the molecular wavefunction in the seniority-zero subspace, while a neural network accounts for contributions from unpaired configurations.

The hybrid wavefunction takes the form:

[ |\Psi\rangle = \hat{\mathcal{N}} \hat{E} (|\psi_{\text{pUCCD}}\rangle \otimes |0\rangle) ]

where (|\psi_{\text{pUCCD}}\rangle) is the quantum circuit state, (\hat{E}) is an entanglement circuit, and (\hat{\mathcal{N}}) is a non-unitary neural network operator. This architecture maintains the low qubit count and shallow circuit depth of pUCCD while achieving accuracy comparable to advanced methods like UCCSD and CCSD(T) [3]. The method demonstrated particular effectiveness for the isomerization reaction of cyclobutadiene, a challenging multi-reference system, maintaining high accuracy on superconducting quantum hardware despite noise.

Dynamic Mode Decomposition for Energy Estimation

Shen et al. introduced the Observable Dynamic Mode Decomposition (ODMD) method, which extracts eigenenergies from real-time measurements of quantum dynamics [23]. This approach formulates energy estimation as a variational method on the function space of observables, providing provably rapid convergence even under significant perturbative noise.

ODMD processes time-series measurement data to construct a Krylov subspace, then performs eigenvalue decomposition to estimate energies. The method establishes an isomorphism to robust matrix factorization techniques, creating a natural bridge between quantum dynamics and established numerical methods. Benchmarks on spin and molecular systems demonstrate accelerated convergence and favorable resource reduction compared to state-of-the-art algorithms [23].

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Convergence Acceleration Data

Table: Performance Comparison of VQE Optimization Strategies

| Method | System | Qubit Count | Iterations to Convergence | Achievable Accuracy (kcal/mol) | Noise Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional COBYLA [6] | Hâ‚‚ (2-qubit) | 2 | ~50 | ~1.0 | Moderate |

| ML-VQE Optimizer [6] | Hâ‚‚ (2-qubit) | 2 | ~10 | ~1.0 | High |

| Conventional COBYLA [6] | HeH⺠| 4 | ~100 | ~2.0 | Moderate |

| ML-VQE Optimizer [6] | HeH⺠| 4 | ~30 | ~2.0 | High |

| pUNN [3] | Nâ‚‚ | 12 | N/A | < 1.0 | High |

| ODMD [23] | CHâ‚„ | 10 | N/A | < 1.0 | High |

Noise Resilience Performance

Quantum metrology integration with quantum computing has demonstrated significant noise suppression capabilities. Wang et al. implemented a quantum principal component analysis (qPCA) protocol on quantum processors to filter noise from quantum sensor data [21]. Experimental implementation with nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond showed a 200-fold improvement in measurement accuracy under strong noise conditions. Simulations of distributed superconducting quantum processors demonstrated a 52.99 dB improvement in quantum Fisher information after qPCA processing, approaching the theoretical Heisenberg limit [21].

Table: Noise Resilience Techniques and Efficacy

| Technique | Implementation Platform | Noise Reduction Efficacy | Resource Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| ML-VQE Training [6] | IBM superconducting processors | High coherent error correction | Moderate (training data collection) |

| Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunction [3] | Superconducting (cyclobutadiene) | High for multi-reference systems | Low (N ancilla qubits) |

| qPCA Filtering [21] | NV centers & superconducting | 200x accuracy improvement | Moderate (multiple state copies) |

| Dynamic Mode Decomposition [23] | Simulated molecular systems | High for perturbative noise | Low (time-series measurements) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Machine Learning-Enhanced VQE for Molecular Ground States

This protocol describes the implementation of a noise-aware ML-VQE optimizer for molecular energy estimation, based on the method developed by Karim et al. [6]

Materials and Setup

- Quantum Processor: IBM superconducting quantum device (or simulator)

- Classical Processor: High-performance CPU/GPU for neural network training

- Software Stack: Qiskit or equivalent quantum programming framework, PyTorch/TensorFlow for machine learning

- Chemical Computation: PySCF for molecular Hamiltonian generation with STO-3G basis set

Procedure

Step 1: Initial Data Generation

- Generate molecular Hamiltonian using PySCF at fixed bond distance

- Map to qubit operators via Jordan-Wigner or parity mapping with symmetry reduction

- Implement hardware-efficient or simplified UCCSD ansatz quantum circuit

- Run conventional VQE with COBYLA optimizer, collecting all intermediate parameters, measurements, and final optimal parameters

- Repeat for multiple molecular configurations to build diverse training set

Step 2: Neural Network Training

- Construct feedforward neural network with ReLU activation, 4 layers, decreasing neurons per layer

- Format input vector as: Hamiltonian coefficients ⊕ circuit parameters ⊕ expectation values

- Set output vector as difference between current and optimal parameters

- Apply data augmentation by reusing intermediate measurements with different Hamiltonian inputs

- Train using mean squared error loss between predicted and actual parameter differences

Step 3: ML-VQE Deployment

- Initialize new molecular system with unknown optimal parameters

- Feed initial random parameters and Hamiltonian to trained neural network

- Obtain predicted optimal parameters in single forward pass

- Prepare quantum state with predicted parameters and measure expectation values

- Iterate if necessary with additional neural network predictions

Validation

- Compare final energy accuracy to full configuration interaction (FCI) or experimental values

- Verify chemical accuracy threshold (1.6 kcal/mol or ~0.0016 Ha) achieved

- Benchmark iteration count and time savings against conventional optimizers

Protocol 2: Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunction (pUNN)

This protocol implements the pUNN framework for molecular energy calculation with enhanced noise resilience [3] [4].

Materials and Setup

- Quantum Processor: Superconducting quantum computer with nearest-neighbor connectivity

- Ancilla Qubits: N additional qubits for Hilbert space expansion

- Neural Network: Custom architecture with binary input encoding and particle number conservation mask

Procedure

Step 1: Quantum Circuit Preparation

- Prepare pUCCD ansatz on N qubits representing seniority-zero subspace

- Expand Hilbert space by adding N ancilla qubits initialized to |0⟩

- Apply entanglement circuit Ê using parallel CNOT gates between original and ancilla qubits

- Implement perturbation circuit using single-qubit R_y(0.2) rotations on ancilla qubits

Step 2: Neural Network Configuration

- Design neural network with binary input layer (size 2N), L = N-3 hidden layers with 2KN neurons (K=2)

- Implement ReLU activation functions in hidden layers

- Apply particle number conservation mask to final layer output

- Initialize weights using standard deep learning initialization schemes

Step 3: Expectation Value Measurement

- For each Pauli string in Hamiltonian, compute 〈Ψ|P|Ψ〉 and 〈Ψ|Ψ〉 using efficient measurement protocol

- Avoid quantum state tomography through careful circuit design

- Combine results from multiple Pauli strings to compute total energy expectation

Step 4: Variational Optimization

- Employ classical optimizer (e.g., Adam, BFGS) to minimize energy with respect to neural network and circuit parameters

- Use gradient-based optimization with parameter shift rules for quantum circuit gradients

- Iterate until energy convergence criterion met (typically ΔE < 10^-6 Ha)

Validation

- Test on multi-reference systems like cyclobutadiene isomerization

- Compare energy accuracy to CCSD(T) and full CI benchmarks

- Verify noise resilience by comparing performance on simulator vs. real hardware

- Assess convergence behavior across different molecular systems

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Processing Units | Execution of parameterized quantum circuits | IBM superconducting processors, trapped ion devices |

| Classical Optimizers | Optimization of circuit parameters | COBYLA, L-BFGS, Rotosolve |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Neural network training and inference | PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX |

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Molecular Hamiltonian generation | PySCF, Psi4, OpenMolcas |

| Quantum Programming SDKs | Circuit design and execution | Qiskit, Cirq, PennyLane |

| Hybrid Quantum-Neural Models | Joint representation of wavefunctions | pUNN architecture, VQNHE |

| Error Mitigation Tools | Noise suppression and correction | Zero-noise extrapolation, probabilistic error cancellation |

| Dynamic Mode Decomposition | Energy estimation from time dynamics | ODMD algorithms, Krylov subspace methods |

| L-Cysteine hydrochloride hydrate | L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate | High-purity L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate for research. Used in food, feed, and plant studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Metoprolol | Metoprolol | High-purity Metoprolol, a selective β1-adrenergic receptor antagonist. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic, therapeutic, or personal use. |

The integration of the quantum variational principle with noise-aware circuit learning represents a significant advancement in molecular energy estimation for drug development. Machine learning-enhanced VQE optimizers demonstrate substantial convergence acceleration, while hybrid quantum-neural wavefunctions achieve near-chemical accuracy on current noisy hardware. These approaches maintain the theoretical foundation of the variational principle while addressing practical limitations of NISQ devices through strategic classical assistance. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, these noise-resilient algorithmic frameworks provide a promising pathway toward practical quantum advantage in computational chemistry and drug discovery applications.

The precise identification of molecular targets and accurate calculation of molecular energies are foundational to advances in drug discovery and materials science. In contemporary research, key molecular targets encompass a broad spectrum, from simple diatomic molecules used as model systems to complex organic compounds like pharmaceutical leads. The accurate computation of their energies, particularly within the emerging paradigm of quantum computational chemistry, presents significant challenges due to hardware noise and algorithmic constraints. This article provides application notes and protocols for noise-aware computational methods that bridge the gap between target identification and precise energy calculation, enabling more reliable predictions of molecular behavior and interactions.

Key Molecular Targets in Drug Discovery

Molecular target identification is a crucial stage in the drug discovery pipeline, enabling researchers to understand the mode of action of bioactive compounds and optimize their therapeutic potential [24]. Targets can include various biomolecules such as enzymes, cellular receptors, ion channels, DNA, and transcription factors [24].

Table 1: Experimental Approaches for Molecular Target Identification

| Approach | Core Principle | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity-Based Pull-Down [25] [24] | Uses tag-conjugated small molecules to isolate target proteins from complex mixtures. | Target identification for compounds with known binding. | High specificity; direct binding partner identification. | Requires chemical modification of the molecule, which may alter its activity. |

| Label-Free Methods [24] | Utilizes small molecules in their natural state without tags to identify targets. | Mode-of-action studies for unmodified compounds. | No chemical modification needed; preserves natural compound behavior. | Can be less specific; may require more complex downstream analysis. |

| Photoaffinity Tagging [24] | Incorporates a photoreactive group that forms a permanent covalent bond with the target upon light exposure. | Identifying transient or low-affinity interactions. | "Locks" the interaction in place, enabling study of difficult-to-capture targets. | Probe design is complex; potential for non-specific binding. |

| Phenotypic Screening [26] | Observes compound effects in cells or whole organisms without a pre-defined target. | Discovering novel therapeutic mechanisms and targets. | Target-agnostic; identifies functional outcomes in biologically relevant systems. | Target deconvolution can be challenging and time-consuming. |

The development of Affinity-based Probes (AfBPs), a subset of Activity-based Protein Profiling (ABPP), has proven particularly powerful. AfBPs bind to target proteins through reversible non-covalent interactions, thus minimizing the impact on the protein's natural biological functions compared to covalent activity-based probes (AcBPs) [25]. These probes, including biotin probes, FITC probes, and BRET probes, are instrumental in studying drug targets, optimizing drugs, and improving therapeutic efficacy [25].

Quantum Computational Chemistry for Molecular Energy Estimation

Quantum computational chemistry holds great promise for simulating molecular systems more efficiently than classical methods by leveraging quantum bits to represent molecular wavefunctions [3]. The accurate calculation of molecular energies, such as the ground state energy, is a central challenge. The commonly accepted precision required for predicting chemically relevant properties is chemical accuracy, typically defined as 1.6 × 10â»Â³ Hartree [27].

The Challenge of Noise in Quantum Hardware

Current quantum implementations face significant limitations due to hardware noise, readout errors, and algorithmic constraints [3] [27]. These factors degrade the quality of quantum computations, making high-precision measurements particularly challenging for near-term quantum devices [27].

Table 2: Techniques for High-Precision Measurement on Quantum Hardware

| Technique | Description | Addresses | Reported Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements [27] | A measurement strategy that allows estimation of multiple observables from the same data set. | Measurement efficiency, Error mitigation. | Enables mitigation of detector noise via quantum detector tomography. |

| Locally Biased Random Measurements [27] | Prioritizes measurement settings that have a larger impact on the energy estimation. | Shot overhead (number of measurements required). | Reduces the number of shots needed while maintaining estimation accuracy. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) [27] | Characterizes the actual noisy measurement process of the quantum device to build an unbiased estimator. | Readout errors, Measurement bias. | Reduced estimation bias; demonstrated order of magnitude error reduction (to 0.16%). |

| Blended Scheduling [27] | Interleaves execution of different quantum circuits to average out time-dependent noise. | Time-dependent noise, System drift. | Ensures homogeneous noise impact across different energy estimations, crucial for calculating energy gaps. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Target Identification Using a Biotin-Tagged Affinity-Based Probe

This protocol outlines the procedure for identifying protein targets of a small molecule using a biotin-tagged affinity-based pull-down approach [24].

Principle: A biotin-tagged small molecule is used as a probe to selectively isolate its target proteins from a complex biological mixture via the high-affinity biotin-streptavidin interaction.

Materials:

- Biotin-tagged small molecule probe

- Cell lysate containing the target protein(s)

- Streptavidin-coated beads (e.g., agarose or magnetic beads)

- Lysis Buffer (e.g., PBS with 1% NP-40 and protease inhibitors)

- Wash Buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.1% Tween-20)

- Elution Buffer (e.g., SDS-PAGE loading buffer with 2% SDS)

- Equipment: Centrifuge, rotator, SDS-PAGE gel, mass spectrometer

Procedure:

- Preparation of Affinity Matrix: Incubate the biotin-tagged probe with streptavidin-coated beads in a suitable buffer for 1-2 hours at 4°C to allow immobilization.

- Binding: Incubate the prepared affinity matrix with the pre-cleared cell lysate for 2-4 hours at 4°C with gentle rotation to allow the probe to interact with its target proteins.

- Washing: Pellet the beads by gentle centrifugation and carefully remove the supernatant. Wash the beads 3-5 times with Wash Buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Elute the bound target proteins by adding Elution Buffer and heating the beads to 95°C for 10 minutes. This denatures the proteins and disrupts the biotin-streptavidin interaction.

- Analysis: Separate the eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE. Excise protein bands of interest and identify them using tryptic digest and mass spectrometry.

Notes: A key limitation is that the harsh elution conditions may denature the purified proteins. The use of a competitive elution (e.g., with excess free biotin) is often not feasible due to the extremely high affinity of the biotin-streptavidin interaction [24].

Diagram 1: Biotin-Tagged Affinity Pull-Down Workflow

Protocol 2: Molecular Energy Estimation using a Hybrid Quantum-Neural Approach (pUNN)

This protocol describes the procedure for computing molecular energies with high accuracy and noise resilience using the pUNN (paired Unitary Coupled-Cluster with Neural Networks) framework [3].

Principle: A hybrid wavefunction is learned by combining an efficient quantum circuit (pUCCD) to capture the quantum phase structure in the seniority-zero subspace, and a neural network to account for contributions from unpaired configurations.

Materials:

- Classical computer with neural network training capabilities (e.g., PyTorch/TensorFlow)

- Access to a quantum computer or simulator

- Molecular geometry and Hamiltonian in a second-quantized form

Procedure:

- Circuit Initialization:

- Map the electronic structure problem to N qubits using a suitable encoding (e.g., Jordan-Wigner).

- Prepare the paired Unitary Coupled-Cluster with double excitations (pUCCD) ansatz

|ψ〉on the quantum processor [3].

- Hilbert Space Expansion:

- Add N ancilla qubits, initialized to

|0〉. - Apply an entanglement circuit

Ê, composed of N parallel CNOT gates, to create correlations between original and ancilla qubits, resulting in state|Φ〉 = Ê(|ψ〉 ⊗ |0〉)[3].

- Add N ancilla qubits, initialized to

- Neural Network Processing:

- Apply a non-unitary post-processing operator

e^Brepresented by a classical neural network. The network inputs a bitstring|k〉 ⊗ |j〉and outputs coefficientsb_kj[3]. - The final, unnormalized hybrid wavefunction is

|Ψ〉 = e^B Ê(|ψ〉 ⊗ |0〉).

- Apply a non-unitary post-processing operator

- Measurement and Expectation Calculation:

- Measure the quantum circuit. The pUNN framework is designed to allow efficient computation of expectation values like energy

E = 〈Ψ|Ĥ|Ψ〉 / 〈Ψ|Ψ〉without requiring quantum state tomography [3].

- Measure the quantum circuit. The pUNN framework is designed to allow efficient computation of expectation values like energy

- Joint Optimization:

- The parameters of both the quantum circuit (pUCCD) and the classical neural network are jointly optimized to minimize the energy expectation value.

Notes: This hybrid approach retains the low qubit count and shallow circuit depth of pUCCD while achieving accuracy comparable to advanced methods like CCSD(T). It has been validated on superconducting quantum computers for complex reactions like the isomerization of cyclobutadiene, showing high accuracy and significant resilience to noise [3].

Diagram 2: pUNN Hybrid Quantum-Neural Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Target ID and Energy Calculation

| Category / Item | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Tags [25] [24] | Enable purification and isolation of target proteins. | Biotin: Strong affinity to streptavidin/avidin. Photoaffinity Groups (e.g., Aryldiazirines): Form covalent bonds with targets upon UV light exposure for capturing transient interactions. |

| Detection Systems [25] [26] | Generate a measurable signal for detecting molecular interactions. | HTRF & ALPHAscreen: Homogeneous assays detecting energy transfer between close probes. FRET/BRET: Measure protein-protein interactions in cells via energy transfer. |

| Quantum Algorithmic Components [3] | Building blocks for variational quantum algorithms. | pUCCD Ansatz: Efficient, low-depth quantum circuit for capturing electron correlation. Separable Pair Ansatz (SPA): A robust, transferable quantum circuit design for electronic structure problems [28]. |

| Noise Mitigation Tools [27] | Techniques to enhance precision on noisy quantum hardware. | Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): Characterizes and corrects for readout errors. Locally Biased Measurements: Reduces the number of experimental "shots" needed. |

| Glycerides, C14-26 | 1-Heptadecanoyl-rac-glycerol|MG(17:0)|CAS 5638-14-2 | Research-grade 1-Heptadecanoyl-rac-glycerol, a bioactive monoacylglycerol with demonstrated antimicrobial properties. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Hordenine | Hordenine, CAS:62493-39-4, MF:C10H15NO, MW:165.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of advanced target identification techniques with noise-resilient quantum computational methods represents a powerful synergy for modern molecular science. Affinity-based probes provide a direct, experimental path to understanding small molecule interactions, while hybrid quantum-neural algorithms like pUNN offer a promising computational route to achieving high-accuracy molecular energy estimates on current quantum hardware. By leveraging the protocols and techniques detailed in these application notes—ranging from wet-lab biochemistry to cutting-edge quantum measurement strategies—researchers are equipped to navigate the challenges from target identification to precise energy calculation, accelerating discovery in drug development and materials science.

Advanced Algorithmic Strategies: Implementing Noise-Resilient Quantum Calculations

Hybrid quantum-classical computing has emerged as a pivotal paradigm for leveraging the complementary strengths of quantum and classical processors, particularly for solving complex problems in computational chemistry and drug discovery on current noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) hardware. These frameworks strategically partition computational workloads: quantum processors handle tasks benefiting from quantum superposition and entanglement, such as preparing complex wavefunctions, while classical processors manage data-intensive preprocessing, optimization loops, and result analysis [29] [30]. This synergy is especially crucial for molecular energy calculations, where achieving chemical accuracy (1.6 mHartree) requires sophisticated error mitigation and resource optimization strategies to overcome hardware limitations such as gate noise, decoherence, and readout errors [31] [27].

Within the specific context of noise-aware circuit learning for molecular energy calculations, hybrid frameworks enable the development of robust, hardware-aware algorithms. By integrating quantum circuit executions with classical machine learning and error mitigation techniques, researchers can create noise-resilient computational pipelines capable of delivering precise molecular energy estimations, which are fundamental for predicting chemical properties and biochemical interactions in drug development [31] [32] [27].

Application Notes: Frameworks for Molecular Energy Calculations

pUCCD-DNN for Molecular Wavefunctions

The pUCCD-DNN (paired Unitary Coupled Cluster with Double excitations - Deep Neural Network) framework addresses a critical limitation of standalone quantum chemistry ansatzes. While the pUCCD quantum circuit efficiently describes the seniority-zero subspace of molecular wavefunctions using only N qubits for N spatial orbitals, it neglects contributions from singly occupied configurations, leading to errors exceeding 100 mHartree [31]. The hybrid framework overcomes this by augmenting the quantum circuit with a deep neural network that specifically corrects for these missing contributions.

This architecture retains the hardware efficiency of the linear-depth pUCCD circuit while achieving accuracy comparable to advanced methods like UCCSD and CCSD(T). Numerical benchmarking on molecules such as Nâ‚‚ and CHâ‚„ demonstrates the approach achieves near-chemical accuracy. Experimental validation on a superconducting quantum computer for the isomerization reaction of cyclobutadiene further confirmed its practical applicability, showing high accuracy in energy estimation and significant resilience to noise [31]. The hybrid design effectively distributes the computational burden: the quantum circuit learns the quantum phase structure, while the neural network provides corrective terms, resulting in a more powerful composite model than either component alone.

High-Precision Measurement Protocol for Molecular Energies

Accurate energy estimation on NISQ devices requires sophisticated measurement strategies to overcome significant readout errors and shot noise limitations. A comprehensive framework integrating multiple techniques has demonstrated order-of-magnitude improvements in measurement precision for molecular energy calculations [27].

The implementation of this protocol for the BODIPY molecule on IBM quantum hardware achieved a remarkable reduction in measurement errors from 1-5% to 0.16%, approaching the threshold for chemical precision (1.6 × 10â»Â³ Hartree) [27]. This precision is essential for reliable molecular energy comparisons in drug design applications, where small energy differences determine binding affinity and reaction rates.

Table 1: High-Precision Measurement Techniques for Molecular Energy Estimation

| Technique | Function | Impact on Precision |

|---|---|---|

| Locally Biased Random Measurements [27] | Prioritizes measurement settings with greater impact on energy estimation | Reduces shot overhead (number of required measurements) |

| Repeated Settings with Parallel QDT [27] | Characterizes and mitigates readout errors using quantum detector tomography | Reduces circuit overhead and measurement bias |

| Blended Scheduling [27] | Interleaves execution of different circuit types | Mitigates time-dependent noise fluctuations |

Hybrid Quantum-Classical Convolutional Neural Networks for Drug Discovery

In pharmaceutical applications, predicting protein-ligand binding affinity is a critical but computationally intensive task. Hybrid quantum-classical convolutional neural networks (QCCNNs) demonstrate how quantum components can enhance classical machine learning models for drug discovery [32].

A recent implementation for binding affinity prediction achieved a 20% reduction in model complexity compared to a purely classical 3D CNN, while maintaining equivalent performance. This architectural efficiency translated into a 20-40% reduction in training time, substantially accelerating the drug discovery pipeline [32]. The quantum layer, designed with approximately 300 gates, was optimized for execution on GPUs and shown to be robust to noise levels up to error probability p=0.01 when combined with error mitigation techniques.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Molecular Energy Estimation with pUCCD-DNN

Application: Computing molecular ground state energies with chemical accuracy. Objective: Leverage hybrid quantum-neural wavefunction to achieve precision comparable to CCSD(T) while maintaining hardware efficiency.

Materials and Reagents:

- Quantum Processing Unit (QPU): Superconducting quantum computer or simulator.

- Classical Computing Resources: High-performance CPU/GPU for neural network training.

- Software Stack: Quantum circuit framework (e.g., Qiskit, PennyLane), deep learning library (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow).

- Molecular System Input: Atomic coordinates and basis set for target molecule.

Procedure:

- Classical Preprocessing:

- Compute molecular orbitals and one-/two-electron integrals using Hartree-Fock method.

- Generate the pUCCD ansatz circuit

U(θ)with parametersθfor the N-orbital system.

Quantum Circuit Execution:

- Prepare the reference state

|ψ_ref>on the quantum processor. - Apply the pUCCD circuit:

|ψ(θ)> = U(θ)|ψ_ref>. - Introduce N ancilla qubits and apply entanglement circuit

Êcomprising N parallel CNOT gates:|Φ> = Ê(|ψ(θ)> ⊗ |0>). - Measure expectation values of the molecular Hamiltonian terms.

- Prepare the reference state

Neural Network Correction:

- Input measured quantum expectations into a deep neural network.

- Train the DNN to predict corrections for singly occupied configurations neglected by pUCCD.

- Optimize hybrid model parameters (both quantum circuit

θand DNN weights) to minimize energy loss function.

Energy Calculation:

- Compute final molecular energy as sum of quantum-measured energy and neural network correction.

- Validate against known molecular energies or classical benchmark methods.

Validation: The protocol was validated on the isomerization reaction of cyclobutadiene, demonstrating high accuracy and noise resilience on superconducting quantum hardware [31].

Protocol: Precision Measurement for Molecular Hamiltonians

Application: High-accuracy energy estimation of molecular states on NISQ devices. Objective: Reduce measurement shot overhead, circuit overhead, and mitigate readout errors to achieve chemical precision.

Materials and Reagents:

- NISQ Device: Programmable quantum processor (e.g., IBM Eagle series).

- Measurement Framework: Informationally complete (IC) measurement infrastructure.

- Software Tools: Libraries for implementing classical shadows, quantum detector tomography, and blended scheduling.

Procedure:

- Hamiltonian and State Preparation:

- Generate the molecular Hamiltonian for the target system (e.g., BODIPY in various active spaces).

- Prepare the desired quantum state (e.g., Hartree-Fock state) on the quantum processor.

Implementation of Locally Biased Measurements:

- Construct a measurement strategy biased toward Hamiltonian terms with significant contributions.

- This reduces the number of unique measurement bases (shots) required for precise estimation.

Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT):

- Execute parallel QDT circuits alongside main experiment to characterize readout errors.

- Use tomographic results to build an unbiased estimator for the energy expectation value.

Blended Scheduling:

- Interleave execution of different quantum circuits (e.g., for Sâ‚€, Sâ‚, Tâ‚ energies) and QDT circuits.

- This averages out temporal noise fluctuations across all measurements.

Data Processing and Error Mitigation:

- Process measurement outcomes using the unbiased estimator derived from QDT.

- Compute final energy estimates with statistical error bars.

Validation: Application to the 8-qubit BODIPY molecule on ibm_cleveland demonstrated an estimation error of 0.16%, significantly closer to chemical precision than standard methods [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Tool/Resource | Function in Hybrid Workflow | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PennyLane Python Library [30] | Unified interface for building & optimizing hybrid quantum-classical models; enables automatic differentiation of quantum circuits. | Variational Quantum Algorithms, Quantum Machine Learning |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) [27] | Characterizes and mitigates readout errors on quantum hardware, enabling unbiased estimation. | High-precision measurement of molecular energies |

| pUCCD Quantum Circuit [31] | Hardware-efficient ansatz for molecular wavefunctions; reduces qubit requirement from 2N to N for N orbitals. | Quantum computational chemistry |

| Locally Biased Classical Shadows [27] | Reduces measurement shot overhead by prioritizing informative measurement settings. | Efficient estimation of complex observables |

| Reconfigurable FPGA Co-Processors [33] | Accelerates classical optimization loops in hybrid algorithms, reducing system bottlenecks. | Near-real-time parameter optimization in VQAs |

| Nonanoic Acid | Nonanoic Acid, CAS:68937-75-7, MF:C9H18O2, MW:158.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Spermine | Spermine, CAS:68956-56-9, MF:C10H26N4, MW:202.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualization

The workflow illustrates the tight integration between quantum and classical resources. The loop between the classical optimizer and quantum circuit execution is characteristic of variational algorithms, requiring efficient data exchange. Contemporary frameworks address this bottleneck through hardware-level solutions like FPGA co-processors [33] and algorithmic improvements like measurement optimizations [27].

Hybrid quantum-classical frameworks represent a pragmatic and powerful approach for leveraging current quantum computing capabilities to solve real-world problems in computational chemistry and drug discovery. By strategically balancing computational tasks between quantum and classical processors, these frameworks mitigate the limitations of NISQ-era hardware while harnessing quantum advantages. The protocols and applications detailed herein provide researchers with practical methodologies for implementing noise-aware circuit learning specifically for molecular energy calculations. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, these hybrid paradigms will remain essential for achieving the precision required for pharmaceutical applications, ultimately accelerating the drug development process and enabling more accurate prediction of molecular behavior.

Within the rapidly evolving field of quantum computational chemistry, the design of the wavefunction ansatz—a trial wavefunction for variational algorithms—presents a critical challenge. This challenge is particularly acute for noise-aware circuit learning applied to molecular energy calculations on Near-Term Intermediate Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware. The ideal ansatz must balance expressiveness to accurately represent complex molecular wavefunctions with hardware practicality to withstand significant device noise and coherence time limitations. This document details application notes and protocols for two complementary strategies: hardware-efficient ansatze that are inherently tailored to a quantum processor's physical architecture and noise profile, and chemistry-inspired ansatze that incorporate fundamental physical principles of molecular systems. Framed within a broader research thesis on noise-aware circuit learning, these guidelines are intended to enable researchers to perform more accurate and reliable molecular simulations on current quantum devices.

Hardware-Efficient Ansatz Design

Hardware-efficient ansatze prioritize the constraints of the physical quantum hardware to maximize circuit fidelity under noisy conditions. The primary goal is to minimize circuit depth and the number of two-qubit gates, which are major sources of error, while maintaining sufficient expressive power for the problem at hand.

Core Principles and Protocols

- Principle 1: Leverage Native Gate Sets. Ansatz circuits should be constructed primarily from the continuously parameterized one- and two-qubit gates natively available on the target hardware. For example, trapped-ion processors often natively support parameterized

ZZ(θ)gates, allowing for the direct compilation of entangling operations without decomposition into a fixed library of gates, thus reducing depth and potential error [34]. - Principle 2: Noise-Aware Compilation. Circuit compilation should not be agnostic to the device's noise properties. Techniques such as swap mirroring can be employed to reduce the total entangling interaction time. Furthermore, the most computationally demanding operations (e.g., the largest

ZZrotation angles) should be strategically mapped to the best-performing qubit pairs on the device to mitigate the impact of coherent and stochastic errors [34]. - Principle 3: Circuit Approximation. In the context of significant noise, a shorter, approximate circuit can yield a more accurate final result than a perfect, longer one. For instance, in randomized benchmarking circuits, removing the least impactful entangling gates has been shown to enable the execution of larger effective quantum volumes [34].

Protocol: Noise-Aware Compilation for Hardware-Efficient Ansatze

Objective: To map a variational ansatz onto a specific quantum processor while minimizing the accumulation of error.

Materials: Quantum processor characterization data (gate fidelities, coherence times, readout errors); classical compiler with hardware-aware capabilities (e.g., Superstaq [34]).

Workflow:

- Device Characterization: Input the device's calibration data, including native gateset (e.g.,

RZ,RY,ZZ(θ)) and a performance map of qubits and links. - Topology-Aware Qubit Mapping: Use the device performance map to assign virtual qubits of the molecule to the most robust physical qubits, prioritizing the placement of highly connected logical qubits onto high-fidelity physical links.

- Gate Decomposition: Decompose all entangling operations directly into the native

ZZ(θ)gates or their equivalents, avoiding the overhead of further decomposition into fixed gates like CNOT. - Dynamic Circuit Optimization: Apply noise-aware compiler optimizations:

- Swap Mirroring: Analyze and optimize communication pathways to minimize total

ZZangle accumulation. - Gate Pruning: Identify and remove parameterized gates that contribute minimally to the ansatz's expressiveness, based on pre-characterization or initial VQE runs.

- Swap Mirroring: Analyze and optimize communication pathways to minimize total

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points in this protocol: