Noise-Resilient Quantum Algorithms: Principles, Applications, and Breakthroughs for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of noise-resilient quantum algorithms, a critical frontier in quantum computing that addresses the pervasive challenge of decoherence and gate imperfections.

Noise-Resilient Quantum Algorithms: Principles, Applications, and Breakthroughs for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of noise-resilient quantum algorithms, a critical frontier in quantum computing that addresses the pervasive challenge of decoherence and gate imperfections. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it delves into the foundational principles that enable algorithms to suppress or exploit noise, moving beyond theoretical constructs to practical methodologies. We examine specific algorithms like VQE and QAOA, their implementation on NISQ hardware, and their transformative applications in molecular simulation and drug discovery. The article further investigates advanced troubleshooting, optimization techniques, and validation frameworks for assessing performance gains, synthesizing key takeaways to outline a future where quantum computing reliably accelerates biomedical innovation.

What Are Noise-Resilient Quantum Algorithms? Defining the Core Principles

The pursuit of quantum computing represents a paradigm shift in computational capability, promising unprecedented advances in drug discovery, materials science, and complex system simulation. This potential stems from harnessing uniquely quantum phenomena—superposition and entanglement—to process information in ways impossible for classical computers. However, the very quantum states that empower these devices are exceptionally fragile, succumbing rapidly to environmental interference. This whitepaper examines the fundamental challenge of quantum noise and decoherence, the primary obstacles to realizing fault-tolerant quantum computation. For researchers in drug development and related fields, understanding these limitations is crucial for assessing the current and near-term viability of quantum computing for molecular simulation and optimization problems. We frame this examination within the critical context of developing noise-resilient quantum algorithms, which aim to function effectively within the constrained, noisy environments of present-day hardware.

Defining the Adversary: Quantum Noise and Decoherence

Quantum Decoherence: The Loss of Quantum Behavior

Quantum decoherence is the physical process by which a quantum system loses its quantum behavior and begins to behave classically [1] [2]. In essence, it is what happens when a qubit's fragile superposition state is disrupted by its environment, causing it to collapse into a definite state (0 or 1) before a computation is complete [1]. This process fundamentally destroys the quantum coherence between states, meaning qubits can no longer exist in a superposition of both 0 and 1 simultaneously [1]. It is crucial to distinguish decoherence from the philosophical concept of wave function collapse; decoherence is a continuous, physical process driven by environmental interaction, not an instantaneous event triggered by observation [2].

Quantum noise refers to the unwanted disturbances that affect quantum systems, leading to errors in quantum computations [3]. Unlike classical noise, which might simply add random bit-flips, quantum noise has more complex and detrimental effects, causing qubits to lose their delicate quantum state [3]. This noise arises from various sources, including thermal fluctuations, electromagnetic interference, imperfections in control signals, and fundamental interactions with the environment [1] [3].

Table: Core Definitions and Distinctions

| Term | Definition | Primary Effect on Qubits | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Decoherence | The process by which a quantum system loses its quantum behavior (superposition/entanglement) due to environmental interaction [1] [2]. | Destroys superposition and entanglement, causing qubits to behave classically. | ||

| Quantum Noise | Unwanted disturbances from various sources (thermal, electromagnetic, control) that lead to errors [3]. | Introduces errors that can lead to decoherence and computational inaccuracies. | ||

| Phase Noise | A type of quantum noise that alters the relative phase between the | 0> and | 1> states of a qubit [3]. | Causes loss of phase information critical for quantum interference. |

| Amplitude Noise | A type of quantum noise that affects the probabilities of measuring the | 0> or | 1> states [3]. | Leads to erroneous population distributions in qubit states. |

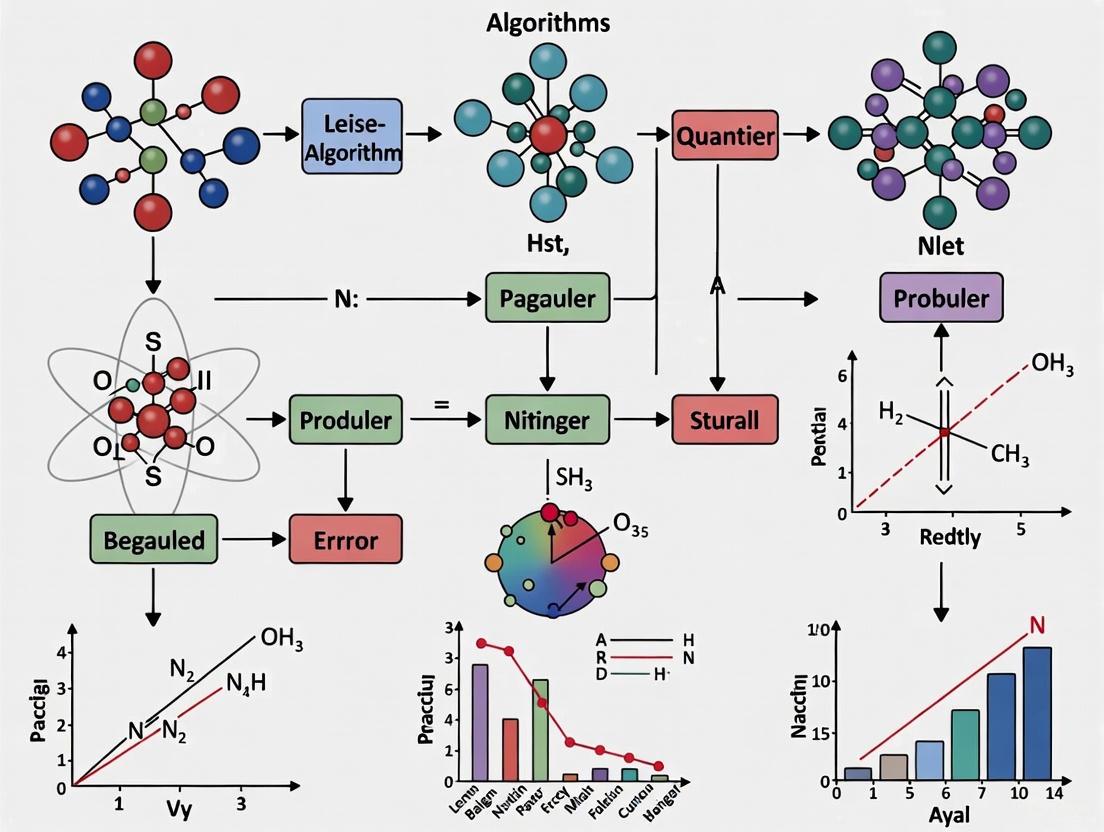

Diagram 1: The process of quantum decoherence, where a quantum state interacts with its environment and loses its quantum properties.

The Physical Mechanisms and Causes of Decoherence

The battle to preserve quantum coherence is fought against multiple, simultaneous fronts. Even minimal interactions can collapse a qubit's fragile state.

Environmental Interaction and Imperfect Isolation

Quantum systems are exquisitely sensitive. Minimal interactions with external particles—such as photons, phonons (lattice vibrations), or magnetic fields—can disturb the quantum state [1]. These interactions effectively "measure" the system, collapsing the wave function and destroying superposition and entanglement [1]. Achieving perfect isolation is virtually impossible; stray electromagnetic signals, thermal noise, and vibrations persistently interfere with quantum systems [1]. The quality of isolation directly dictates coherence time—the duration a qubit remains usable, which is typically on the order of microseconds to milliseconds [2].

Material and Control-Level Imperfections

At the microscopic level, material defects such as atomic vacancies or grain boundaries can create localized charge or magnetic fluctuations that disrupt qubit behavior, leading to reduced coherence times [1]. Furthermore, quantum computers rely on precisely timed control pulses to manipulate qubits. Noise in these control signals, whether from electronic instrumentation or external interference, can distort quantum operations and introduce errors, accelerating decoherence [1].

Quantifying the Impact: Effects on Quantum Computing

Decoherence directly limits the computational potential of quantum systems, imposing strict boundaries on what can be achieved with current hardware.

Limited Circuit Depth and Scalability Challenges

Decoherence significantly limits the depth of quantum circuits—the number of sequential operations that can be performed before the system loses coherence [1]. When decoherence collapses quantum states prematurely, calculations are corrupted, which restricts the time window for accurate quantum computation [1]. This directly impacts the ability to run complex algorithms requiring numerous operations. As the number of qubits increases, the system becomes more vulnerable to environmental noise and crosstalk, making the preservation of coherence across all qubits exponentially harder and posing a major barrier to scaling quantum systems [1].

Table: Comparative Decoherence Characteristics Across Qubit Platforms

| Qubit Platform | Typical Coherence Times | Primary Noise & Decoherence Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Superconducting Qubits | Microseconds to Milliseconds [2] | Residual electromagnetic radiation, thermal vibrations (phonons), material defects [1] [2]. |

| Trapped Ions | Inherently longer than superconducting qubits [2] | Laser imperfections, fluctuating magnetic fields, motional heating [2]. |

| Photonic Qubits | Resistant over long distances [2] | Photon loss and noise from imperfect optical components [2]. |

| Solid-State Qubits | Varies; often suffers from faster decoherence [2] | Complex and noisy atomic-level environments (e.g., spin impurities) [2]. |

Strategic Mitigation: From Hardware to Algorithms

Overcoming decoherence requires a multi-pronged approach, combining physical hardware engineering with innovative algorithmic and logical strategies.

Physical and Hardware-Level Mitigation

- Cryogenic Systems and Shielding: Operating qubits at temperatures near absolute zero using cryogenic systems (e.g., dilution refrigerators) is a foundational technique for reducing thermal noise [1]. This is combined with electromagnetic and vibrational shielding to isolate qubits from environmental interference, thereby prolonging coherence times [1].

- Topological Qubits: An advanced approach involves encoding quantum information in the global, topological properties of a system (e.g., using non-abelian anyons) rather than in local degrees of freedom [1]. This makes the information inherently resistant to local noise sources, paving the way for fault-tolerant quantum computing, though practical implementations remain largely experimental [1].

Quantum Error Correction and Resilient Encoding

- Quantum Error Correction Codes (QECC): QECs, such as the surface code, encode a single logical qubit into multiple physical qubits [1]. This redundancy allows the system to detect and correct errors (e.g., bit-flips, phase-flips) without directly measuring the logical qubit state, thereby protecting the information from decoherence [1] [4].

- Decoherence-Free Subspaces (DFS): This technique involves encoding qubit states into specific combinations that are immune to collective noise, such as common-mode phase noise [1]. By designing the system so the environment cannot distinguish these states, quantum information can be stabilized without constant error correction [1].

Diagram 2: A layered strategy for mitigating quantum noise, combining characterization, correction, and resilient design.

The Path Forward: Noise-Resilient Algorithms and Characterization

For near-term applications, especially on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, designing algorithms that are inherently robust to noise is as critical as improving hardware.

Noise-Resilient Algorithmic Principles

A noise-resilient quantum algorithm is defined as one whose computational advantage or functional correctness is preserved under physically realistic noise models, often up to specific quantitative thresholds [5]. Key strategies include:

- Variational Hybrid Quantum-Classical Algorithms (VHQCAs): Algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) are hybrid models where a classical optimizer tunes parameters for a quantum circuit [5] [6]. These algorithms demonstrate "optimal parameter resilience," meaning the location of the global minimum in the parameter landscape is often unchanged under certain incoherent noise models, even if the absolute value of the cost function is affected [5].

- Dynamical Decoupling: This technique employs engineered sequences of fast control pulses applied to qubits to effectively "echo out" low-frequency environmental noise, thereby extending their coherence times [5]. In some implementations, these sequences can simultaneously perform non-trivial quantum gates with high fidelity [5].

- Noise-Aware Circuit Learning (NACL): Machine learning frameworks can be used to produce quantum circuit structures inherently adapted to a specific device's native gates and noise processes, minimizing idle periods and parallelizing noisy gates to reduce infidelity [5].

Advanced Characterization and Error Correction

Recent research breakthroughs are providing new tools to manage noise. A team from Johns Hopkins APL and University has developed a novel framework for quantum noise characterization that exploits mathematical symmetry to simplify the complex problem of understanding how noise propagates in space and time across a quantum processor [7]. This allows noise to be classified into specific categories, informing the selection of the most effective mitigation technique [7]. Furthermore, theoretical work from NIST has identified a family of covariant quantum error-correcting codes that protect entangled sensors, enabling them to outperform unentangled ones even when some qubits are corrupted [8]. This approach prioritizes robust operation over perfect error correction, a valuable trade-off for practical sensing and computation [8].

Table: Experimental Protocols for Noise Characterization and Mitigation

| Protocol/Method | Primary Objective | Key Steps & Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Symmetry-Based Noise Characterization [7] | To accurately capture how spatially and temporally correlated noise impacts quantum computation. | 1. Exploit system symmetry (e.g., via root space decomposition) to create a simplified model.2. Apply noise to see if it causes state transitions.3. Classify noise into categories to determine the appropriate mitigation technique. |

| Tailored Quench Spectroscopy (TQS) [9] | To compute Green's functions (for probing quantum systems) without ancilla qubits, enhancing noise resilience. | 1. Prepare symmetrized thermal states.2. Apply a tailored quench operator (a sudden perturbation).3. Let the system evolve under its own Hamiltonian.4. Measure an observable over time and analyze the signal to reconstruct the correlator. |

| Circuit-Noise-Resilient Virtual Distillation (CNR-VD) [5] | To mitigate errors in observable estimation while accounting for noise in the mitigation circuit itself. | 1. Run calibration circuits on easy-to-prepare states.2. Use the ratio of observable estimates from calibration to cancel circuit noise to first order.3. Apply the calibrated mitigation to the target state. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table: Essential "Research Reagent Solutions" for Quantum Noise and Decoherence Research

| Item / Technique | Function / Role in Research |

|---|---|

| Dilution Refrigerator | Cools quantum processors to near absolute zero (mK range), drastically reducing thermal noise and prolonging coherence times, especially for superconducting qubits [1]. |

| Parameterized Quantum Circuits (PQCs) | The core "ansatz" or structure in Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs). They are tuned by classical optimizers to find solutions resilient to noise [5] [6]. |

| Quantum Error Correction Codes (e.g., Surface Code) | A software-level "reagent" that provides redundancy. It encodes logical qubits into many physical qubits to detect and correct errors without collapsing the quantum state [1] [4]. |

| Decoherence-Free Subspaces (DFS) | A mathematical framework for encoding quantum information into a special subspace of the total Hilbert space that is inherently immune to certain types of collective noise [1]. |

| Dynamical Decoupling Pulse Sequences | A control technique involving precisely timed electromagnetic pulses applied to qubits to refocus and cancel out the effects of low-frequency environmental noise [5]. |

| IMD-0354 | IMD-0354, CAS:978-62-1, MF:C15H8ClF6NO2, MW:383.67 g/mol |

| lacto-N-fucopentaose II | lacto-N-fucopentaose II, CAS:21973-23-9, MF:C32H55NO25, MW:853.8 g/mol |

Quantum noise and decoherence present a formidable but not insurmountable barrier to practical quantum computing. For researchers in drug development and other applied fields, the current landscape is one of constrained potential. While the hardware is too noisy for directly running complex algorithms like Shor's, promising pathways exist through noise-resilient algorithmic strategies such as VQEs and QAOA, which are designed for the NISQ era. The progress in quantum error correction and advanced noise characterization provides a clear trajectory toward fault tolerance. The future of quantum computing in scientific discovery therefore depends on a co-evolution of hardware stability and algorithmic intelligence, where understanding and mitigating decoherence remains the central, defining challenge.

Quantum computing holds transformative potential, but its practical realization is challenged by quantum noise—unwanted disturbances that cause qubits to lose their delicate quantum states, a phenomenon known as decoherence [3]. Unlike classical bit-flip errors, quantum errors are far more complex, affecting not just the binary value (0 or 1) of a qubit but also its phase, which is crucial for quantum interference and entanglement [10]. This noise arises from various sources including thermal fluctuations, electromagnetic interference, imperfections in quantum gate operations, and broader environmental interactions [3]. If left unmanaged, these errors rapidly accumulate, rendering quantum computations meaningless and presenting a fundamental barrier to building large-scale, fault-tolerant quantum computers [3].

To address this challenge, the field has developed a multi-layered defense strategy, often conceptualized as a hierarchy comprising error suppression, error mitigation, and error correction [10]. This spectrum of techniques represents different trade-offs between immediate feasibility and long-term fault tolerance, each playing a distinct role in the broader ecosystem of noise-resilient quantum computation. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these strategies, their theoretical foundations, experimental protocols, and integration within modern quantum algorithms, providing researchers and scientists with a comprehensive framework for navigating the complex landscape of quantum noise resilience.

Foundational Concepts and Noise Models

Mathematical Frameworks for Quantum Noise

Quantum noise is mathematically described via trace-preserving completely positive (CPTP) maps. The evolution of a quantum state Ï under a noisy channel is given by: ( \rho \rightarrow \Phi(\rho) = \sumk Ek \rho Ek^\dagger ) where ({Ek}) are the Kraus operators satisfying (\sumk Ek^\dagger E_k = I) [5]. This formalism captures a wide variety of noise processes affecting quantum systems.

Commonly used canonical noise models include [5]:

- Depolarizing channel: With probability (α), the qubit is replaced by a completely mixed state (I/2), effectively randomizing the qubit state. Its Kraus operators are ({\sqrt{1-α} I, \sqrt{α/3} σx, \sqrt{α/3} σy, \sqrt{α/3} σ_z}).

- Amplitude damping: Models energy dissipation, with Kraus operators (E0 = \begin{bmatrix}1 & 0\ 0 & \sqrt{1-α}\end{bmatrix}) and (E1 = \begin{bmatrix}0 & \sqrt{α}\ 0 & 0\end{bmatrix}), representing population transfer from (|1\rangle) to (|0\rangle).

- Phase damping: Describes loss of quantum phase coherence without energy loss, with Kraus operators (E0 = \begin{bmatrix}1 & 0\ 0 & \sqrt{1-α}\end{bmatrix}) and (E1 = \begin{bmatrix}0 & 0\ 0 & \sqrt{α}\end{bmatrix}).

In multi-qubit systems, these single-qubit channels are extended through tensor products: ({Ek} = {e{i1} \otimes e{i2} \otimes ... \otimes e{i_N}}), capturing both local and correlated noise effects across multiple qubits [5].

Quantitative Resilience and Error Thresholds

The resilience of quantum algorithms can be quantified using metrics based on the Bures distance or fidelity of the output state as a function of noise parameters and gate sequences [5]. Computational complexity analysis under noisy conditions reveals that quantum advantage typically persists only if per-iteration noise remains below model- and size-dependent thresholds [5].

Table 1: Noise Thresholds for Preserving Quantum Advantage (C=0.95)

| Noise Model | Number of Qubits | Maximum Tolerable Error Rate (α) |

|---|---|---|

| Depolarizing | 4 | ~0.025 |

| Amplitude damping | 4 | ~0.069 |

| Phase damping | 4 | ~0.177 |

For algorithms like quantum search, maintaining a computational advantage over classical approaches requires per-iteration error rates typically between 0.01–0.2, with stricter requirements as system size increases [5]. A general tradeoff exists between circuit complexity and noise sensitivity, where minimizing gate count or circuit depth can paradoxically increase susceptibility to errors [5].

The Error Resilience Spectrum: Principles and Techniques

Error Suppression: Hardware-Level Control

Error suppression encompasses techniques that use knowledge of undesirable noise effects to introduce hardware-level customization that anticipates and avoids potential impacts [10]. These methods operate closest to the physical qubits and often remain transparent to the end user.

Key error suppression techniques include [10]:

- Dynamic decoupling: Inspired by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques, this method applies carefully timed pulse sequences to "refocus" idle qubits, effectively undoing the effects of environmental noise. A prominent example is the spin echo technique, which can extend qubit coherence times by refocusing dephasing noise.

- Derivative Removal by Adiabatic Gate (DRAG): This technique adds a customized component to standard control pulses to reduce the probability of qubits leaking to higher energy states beyond the computational basis states (|0\rangle) and (|1\rangle).

- Advanced pulse shaping: Beyond DRAG, numerous other pulse-shaping techniques developed over decades of quantum control research are now being implemented in quantum processors to minimize gate errors from the ground up.

These suppression methods primarily target the physical sources of noise before they can manifest as computational errors, effectively improving the raw performance of quantum hardware without requiring additional circuit-level interventions.

Error Mitigation: Post-Processing and Statistical Methods

Error mitigation comprises statistical techniques that use the outputs of ensembles of quantum circuits to reduce or eliminate the effect of noise when estimating expectation values [10]. Unlike suppression, mitigation does not prevent errors from occurring but instead corrects for them in classical post-processing, making these methods particularly valuable for near-term quantum devices.

Table 2: Quantum Error Mitigation Techniques and Their Overheads

| Technique | Core Principle | Key Applications | Resource Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | Extrapolates measurements at different noise strengths to infer zero-noise value | Expectation value estimation | Polynomial in circuit depth |

| Probabilistic Error Cancellation | Applies noise-inverting circuits to cancel out average error effects | High-accuracy observable measurement | Exponential in number of qubits |

| Virtual Distillation (VD) | Uses multiple circuit copies to suppress errors in eigenstate preparation | State purification, error suppression | Linear in copy number |

| Twirled Readout Error eXtinction (TREX) | Specifically reduces noise in quantum measurement | Readout error mitigation | Moderate measurement overhead |

These techniques enable the calculation of nearly noise-free (unbiased) expectation values, which can encode crucial properties such as magnetization of spin systems, molecular energies, or cost functions [10]. However, this comes at the cost of significant computational overhead, which typically increases exponentially with problem size for the most powerful methods [10]. For problems involving hundreds of qubits with equivalent circuit depth, error mitigation may still offer practical utility, bridging the gap between current devices and future fault-tolerant systems [10].

Quantum Error Correction: Path to Fault Tolerance

Quantum error correction (QEC) represents the ultimate goal for handling quantum errors, aiming to achieve fault-tolerant quantum computation through strategic redundancy [10]. In QEC, information from single logical qubits is encoded across multiple physical qubits, with specialized operations and measurements deployed to detect and correct errors without collapsing the quantum state [10].

According to the threshold theorem, there exists a hardware-dependent error rate below which quantum error correction can effectively suppress errors, provided sufficient qubit resources are available [10]. The surface code, one of the most promising QEC approaches, requires (O(d^2)) physical qubits per logical qubit, where the code distance (d) determines how many errors can be corrected [10]. With current quantum devices exhibiting relatively high error rates, the physical qubit requirements for practical QEC remain prohibitive.

Emerging codes like the gross code offer potential for storing quantum information in an error-resilient manner with significantly reduced hardware overhead, though these may require substantial redesigns of current quantum hardware architectures [10]. Active research continues to explore new codes and layouts that balance hardware requirements with error correction capabilities.

Advanced Characterization and Noise-Aware Algorithms

Advanced Noise Characterization Frameworks

Recent breakthroughs in noise characterization are enabling more effective error suppression and mitigation strategies. Researchers from Johns Hopkins APL and Johns Hopkins University have developed an innovative framework that addresses a critical limitation of existing models: their inability to capture how noise propagates across both space and time in quantum processors [7].

By applying root space decomposition—a mathematical technique that organizes how actions take place in a quantum system—the team achieved radical simplifications in system representation and analysis [7]. This approach allows quantum systems to be modeled as ladders, where each rung represents a discrete system state. Applying noise to this model reveals whether specific noise types cause state transitions, enabling classification into distinct categories that inform appropriate mitigation techniques [7]. This structured understanding of noise propagation is particularly valuable for implementing quantum error-correcting codes fault-tolerantly, as capturing spatiotemporal noise correlations is essential for large-scale quantum computation [7].

Noise-Resilient Algorithmic Design

Beyond generic error handling techniques, specific quantum algorithms demonstrate inherent resilience to noise through their structural design:

Variational Hybrid Quantum-Classical Algorithms (VHQCAs): Algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) exhibit "optimal parameter resilience"—the global minimum of their cost functions remains unchanged under wide classes of incoherent noise models (depolarizing, Pauli, readout), even though absolute cost values may shift or scale [5]. Mathematically, a noisy cost function ( \widetilde{C}(V) = p C(V) + (1-p)/2^n ) preserves the same minima as the noiseless ( C(V) ) [5].

Noise-Aware Circuit Learning (NACL): Machine learning frameworks can optimize circuit structures specifically for noisy hardware by minimizing task-specific cost functions informed by device noise models [5]. These approaches yield circuits with reduced idle periods, strategic parallelization of noisy gates, and empirically demonstrate 2–3× reductions in state preparation and unitary compilation infidelities compared to standard textbook decompositions [5].

Intrinsic Algorithmic Fault Tolerance: Some algorithms naturally resist certain error types. In Shor's algorithm, for instance, modular exponentiation circuits show significantly higher fault-tolerant position densities against phase noise compared to bit-flip errors—a direct consequence of the algorithm's mathematical structure [5].

Table 3: Noise Resilience in Quantum Algorithm Families

| Algorithm Family | Resilience Mechanism | Noise Type Addressed | Demonstrated Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variational Algorithms (VQE, QAOA) | Optimal parameter resilience | Depolarizing, Pauli, readout | Identical minima location in parameter space |

| Lackadaisical Quantum Walks | Self-loop amplitude protection | Decoherence, broken links | Maintains marked vertex probability under noise |

| Bucket-Brigade QRAM | Limited active components per query | Arbitrary CPTP channels | Polylogarithmic infidelity scaling |

| Dynamical Decoupling Gates | Built-in error suppression | General decoherence | 0.91–0.88 fidelity, >30× coherence extension |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Noise-Resilient Quantum Metrology Protocol

Recent experimental work demonstrates a practical framework for noise-resilient quantum metrology that directly addresses the classical data loading bottleneck in quantum computing [11]. The protocol shifts focus from classical data encoding to directly processing quantum data, optimizing information acquisition from quantum metrology tasks even under realistic noise conditions [11].

Experimental Components and Setup:

- Quantum Processing Unit: Implementation using nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers in diamond or distributed superconducting quantum processors [11].

- Control System: Precision pulse sequencing for dynamic decoupling and quantum gate operations.

- Measurement Apparatus: High-fidelity readout capabilities for quantum state measurement.

- Classical Co-Processor: Optimization routines for parameter tuning and error mitigation.

Methodology:

- Quantum State Preparation: Initialize the quantum sensor (e.g., NV center) in a known quantum state.

- Parameter Encoding: Expose the sensor to the physical parameter of interest (e.g., magnetic field), encoding information through phase accumulation.

- Noise Characterization: Apply quantum noise spectroscopy techniques to characterize the environmental noise spectrum.

- Dynamic Decoupling: Implement optimized pulse sequences (e.g., CPMG, XY8) to suppress decoherence while preserving signal sensitivity.

- Quantum Processing: Apply optimized quantum circuits on the quantum computer to process the quantum data, enhancing signal extraction.

- Measurement and Mitigation: Perform final measurements with error mitigation techniques (e.g., zero-noise extrapolation) to improve accuracy.

Key Metrics:

- Quantum Fisher Information: Quantifies the ultimate sensitivity limit of the metrological process.

- Estimation Accuracy: Measures deviation from true parameter values.

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio: assesses practical sensitivity improvements.

This approach has demonstrated significant improvements in both estimation accuracy and quantum Fisher information, offering a viable pathway for harnessing near-term quantum computers for practical quantum metrology applications [11].

Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Error Characterization

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Quantum Noise Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen-Vacancy (NV) Centers in Diamond | Solid-state qubit platform with long coherence times | Quantum metrology, sensing implementations [11] |

| Superconducting Qubit Processors | Scalable quantum processing units | Multi-qubit error mitigation protocols [11] |

| Dynamic Decoupling Pulse Sequences | Refocuses environmental noise | Coherence preservation in idle qubits [10] |

| DRAG Pulse Generators | Suppresses qubit leakage to non-computational states | High-fidelity gate operations [10] |

| Surface Code Kit | Implementation of topological quantum error correction | Fault tolerance demonstrations [10] |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation Software | Infers zero-noise values from noisy measurements | Error mitigation in expectation values [10] |

| Root Space Decomposition Framework | Classifies noise by spatiotemporal properties | Advanced noise characterization [7] |

Integrated Framework and Future Directions

The most powerful applications of quantum error resilience emerge from integrated approaches that combine suppression, mitigation, and correction strategies tailored to specific hardware capabilities and algorithmic requirements. The emerging paradigm of error-centric quantum computing recognizes noise management not as an auxiliary consideration but as a central design principle influencing every level of the quantum computing stack [7].

Future progress will likely focus on several key frontiers:

- Hybrid Error Correction-Mitigation Protocols: Combining partial error correction with sophisticated mitigation techniques to achieve practical fault tolerance with reduced qubit overhead [10].

- Algorithm-Aware Error Suppression: Developing noise models and suppression techniques specifically optimized for dominant algorithmic primitives in quantum simulation, optimization, and machine learning.

- Machine Learning for Error Adaptation: Leveraging classical machine learning to dynamically adapt error management strategies based on real-time noise characterization [5].

- Cross-Layer Optimization: Coordinating error management across hardware, compiler, and application layers to maximize overall computational fidelity within resource constraints.

For researchers in fields like drug development and molecular simulation, where algorithms like VQE and QAOA show immediate promise, the strategic selection and integration of error resilience techniques will be crucial for extracting meaningful results from current-generation quantum processors [6]. As the field progresses, the distinction between "noise-resilient algorithms" and "quantum algorithms" is likely to blur, with resilience becoming an inherent property of practically useful quantum computations rather than a specialized consideration.

The pursuit of practical quantum computing is fundamentally constrained by noise and decoherence, which disrupt fragile quantum states and compromise computational integrity. Within this challenge, however, lies a transformative opportunity: the strategic use of quantum mechanics' core principles—superposition, entanglement, and interference—not merely as computational resources, but as active mechanisms for noise resilience. This whitepaper delineates how these non-classical phenomena can be harnessed to design algorithms and implement experimental protocols that intrinsically counteract decoherence. Framed within a broader thesis on noise-resilient quantum algorithms, this document provides researchers and drug development professionals with a technical guide to principles and methodologies that are pushing the boundaries of what is possible on contemporary noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. By integrating advanced algorithmic strategies with novel hardware control techniques, we can engineer quantum computations that are inherently more robust, bringing us closer to a future of quantum advantage in critical domains like molecular simulation and drug discovery.

Fundamental Quantum Principles and Noise

The Quantum Triad and Their Roles

The computational power of quantum systems arises from the interplay of three core principles:

- Superposition: A quantum bit (qubit) can exist in a state that is a linear combination of the |0⟩ and |1⟩ basis states, described by |ψ⟩ = α|0⟩ + β|1⟩, where α and β are complex probability amplitudes [12]. This allows a quantum computer to simultaneously explore a vast solution space.

- Entanglement: A strong non-local correlation between qubits such that the quantum state of one cannot be described independently of the others [13]. This enables a level of parallelism and correlation that is unattainable in classical systems.

- Interference: The phenomenon where the probability amplitudes of quantum states combine, either constructively to amplify correct solutions or destructively to cancel out incorrect ones [6]. This allows quantum algorithms to steer a computation toward a desired outcome.

Predominant Noise Models in Quantum Hardware

Noise in quantum systems is mathematically described by quantum channels, represented as trace-preserving completely positive (CPTP) maps. The table below summarizes canonical noise models and their impact on the quantum triad [5].

Table 1: Canonical Quantum Noise Models and Their Effects

| Noise Model | Mathematical Description (Kraus Operators) | Physical Effect | Impact on Quantum Triad | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depolarizing | {√(1-α) I, √(α/3) σx, √(α/3) σy, √(α/3) σz} |

With probability α, the qubit is replaced by a completely mixed state; otherwise, it is untouched. | Equally degrades superposition, entanglement, and interference. | ||

| Amplitude Damping | E₀ = [[1, 0], [0, √(1-α)]], E₠= [[0, √α], [0, 0]] |

Models energy dissipation, causing a qubit to decay from | 1⟩ to | 0⟩. | Directly disrupts superposition and reduces entanglement. |

| Phase Damping | E₀ = [[1, 0], [0, √(1-α)]], E₠= [[0, 0], [0, √α]] |

Causes loss of quantum phase information without energy loss. | Primarily disrupts phase relationships, crippling interference and entanglement. |

Advanced Noise-Resilience Strategies and Experimental Protocols

Exploiting Structural Noise: Metastability

A recent groundbreaking strategy involves characterizing and leveraging the inherent structure of hardware noise, particularly metastability—a phenomenon where a dynamical system exhibits long-lived intermediate states before relaxing to equilibrium [14].

Experimental Protocol: Identifying Metastable Noise

- System Preparation: Initialize the quantum processor in a set of linearly independent states, {Ïáµ¢(0)}.

- Noise Probing: Let each state evolve under the native noise of the idle processor for a time Ï„, resulting in states {Ïáµ¢(Ï„)}.

- Tomography and Spectral Analysis: Perform quantum state tomography on the evolved states. Construct and diagonalize the estimated Liouvillian superoperator, â„’, that best describes the evolution: Ï(Ï„) ≈ e^(â„’Ï„)Ï(0).

- Timescale Separation: Identify the eigenvalues {λⱼ} of â„’. A spectral gap, where |Re(λâ‚)| ≫ |Re(λ₂)|, indicates metastability. The slow modes (associated with λ₂, λ₃, ...) define a metastable manifold.

- Algorithm Design: Design quantum circuits (e.g., for VQE) such that the ideal final state lies within or near this metastable manifold, thereby inheriting its protection from rapid decay.

This protocol provides an efficiently computable resilience metric and has been experimentally validated on IBM's superconducting processors and D-Wave's quantum annealers [14].

Dynamical Decoupling and Self-Protected Gates

Dynamical decoupling (DD) employs rapid sequences of control pulses to refocus a quantum system and average out low-frequency noise. Advanced DD protocols can be engineered to perform non-trivial quantum gates simultaneously, creating "self-protected" operations [5].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Self-Protected CNOT Gate

- System: A hybrid spin system (e.g., an NV center electron spin coupled to a ^13C nuclear spin).

- Pulse Sequence Design: Design a 4-pulse DD sequence where the timing and phase of pulses are optimized not just for decoupling but to enact the specific unitary transformation of a CNOT gate.

- Execution & Benchmarking: Execute the sequence on the hardware and use gate set tomography to characterize the achieved fidelity. Experiments have demonstrated fidelities of 0.91–0.88 with this method, extending coherence times by more than 30x compared to free decay [5].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for developing and testing a metastability-aware algorithm:

Diagram 1: Workflow for metastability-aware algorithm design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental advances discussed are enabled by a suite of specialized hardware and software "reagents." The following table details key components essential for research in quantum noise resilience.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Quantum Noise Resilience Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| FPGA-Integrated Quantum Controller | A controller with a Field-Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) enables real-time, low-latency feedback and control, bypassing slower classical computing loops. | Implementing the "Frequency Binary Search" algorithm to track and compensate for qubit frequency drift in real-time [15]. |

| Commercial Quantum Controller (e.g., Quantum Machines) | Provides a high-level programming interface (often Python-like) to leverage FPGA capabilities without requiring specialized electrical engineering expertise. | Enabled researchers from the Niels Bohr Institute and MIT to program complex feedback routines for noise mitigation [15]. |

| Samplomatic Package (Qiskit) | A software package that allows for advanced circuit annotations and the application of composable error mitigation techniques like Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC). | Used to decrease the sampling overhead of PEC by 100x, making advanced error mitigation practical for utility-scale circuits [16]. |

| Dynamic Circuits Capability | Quantum circuits that incorporate classical operations (e.g., mid-circuit measurement and feed-forward) during their execution. | Demonstrated a 25% improvement in accuracy for a 46-site Ising model simulation by applying dynamical decoupling during idle periods [16]. |

| qLDPC Code Decoder (e.g., RelayBP) | A decoding algorithm for quantum Low-Density Parity-Check (qLDPC) error-correcting codes that operates with high speed and accuracy on FPGAs. | Critical for fault-tolerant quantum computing; IBM's RelayBP on an AMD FPGA completes decoding in under 480ns [16]. |

| Lamellarin E | Lamellarin E, CAS:115982-19-9, MF:C29H25NO9, MW:531.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Deoxylapachol |

Quantitative Analysis of Algorithmic Resilience

The performance of noise-resilient strategies can be rigorously quantified. The table below synthesizes key metrics from recent research, providing a benchmark for comparison.

Table 3: Quantitative Performance of Noise-Resilience Techniques

| Resilience Technique | Key Metric | Reported Performance | Context & Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase Stabilization (NIST) | Photon flux for stable phase lock | < 1 million photons/sec | 10,000x fainter than standard techniques; enables long-distance quantum links [17]. |

| Frequency Binary Search | Number of measurements for calibration | < 10 measurements | Exponential precision with measurements; scalable for large qubit arrays [15]. |

| Self-Protected DD Gates | Gate Fidelity & Coherence Extension | Fidelity: 0.91–0.88; Coherence: >30x | Achieved on an NV-center system using a self-protected CNOT gate [5]. |

| Noise Thresholds (Quantum Search) | Max Tolerable Noise (α) for C=0.95 (4 qubits) | Depolarizing: ~0.025Amplitude Damping: ~0.069Phase Damping: ~0.177 | Establishes the noise levels beyond which quantum advantage is lost [5]. |

| Optimizer Performance (VQE) | Performance in Noisy Landscapes | Top Algorithms: CMA-ES, iL-SHADE | Benchmarked on a 192-parameter Hubbard model; outperformed standard optimizers like PSO and GA [18]. |

The interplay between superposition, entanglement, and interference in a noise-resilient algorithm can be visualized as a reinforced structure, where each principle contributes to the overall stability.

Diagram 2: How quantum principles are leveraged against noise sources.

The path to robust quantum computation does not rely solely on suppressing all noise, but increasingly on the sophisticated co-opting of quantum mechanical principles to design intrinsic resilience. As demonstrated by advances in metastability exploitation, real-time frequency calibration, and noise-aware compiler frameworks, the core quantum traits of superposition, entanglement, and interference are powerful allies in this endeavor. For researchers in fields like drug development, where quantum simulation promises transformative breakthroughs, understanding these principles is the key to effectively leveraging near-term quantum devices. The experimental protocols and quantitative benchmarks outlined in this whitepaper provide a foundation for developing and validating the next generation of noise-resilient quantum algorithms, accelerating progress from theoretical advantage to practical utility.

In the rapidly evolving field of quantum computing, the transition from theoretical potential to practical application is primarily constrained by inherent quantum noise, particularly in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era. The performance and reliability of quantum algorithms are fundamentally governed by specific metrics that quantify their effectiveness in the presence of such noise. Among these, accuracy, precision, and Quantum Fisher Information (QFI) have emerged as the three cornerstone metrics for evaluating quantum algorithmic performance, especially for noise-resilient protocols [19] [20]. Accuracy measures the closeness of a computational or metrological result to its true value, while precision quantifies the reproducibility and consistency of repeated measurements [19]. The QFI, a pivotal concept from quantum metrology, quantifies the ultimate precision bound for estimating a parameter encoded in a quantum state, thus defining the maximum extractable information [21]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these metrics, detailing their theoretical foundations, practical measurement methodologies, and interrelationships, with a specific focus on their critical role in advancing noise-resilient quantum algorithms for applications such as drug discovery and materials science.

Theoretical Foundations of Key Metrics

Accuracy and Precision in Quantum Systems

In the context of quantum computation and metrology, accuracy and precision are distinct yet complementary concepts essential for benchmarking performance.

Accuracy is formally defined as the degree of closeness between a measured or computed value and the true value of the parameter being estimated. In quantum metrology, a primary task is to estimate an unknown physical parameter, such as the strength of a magnetic field characterized by its frequency ( \omega ). The accuracy of this estimation is often quantified using the fidelity between the ideal target quantum state ( \rhot ) and the experimentally obtained (and potentially noisy) state ( \tilde{\rho}t ) [19] [20]. A high-fidelity state implies high accuracy in the quantum information processing task.

Precision, conversely, refers to the reproducibility of measurements and the spread of results around their mean value. It is related to the variance of the estimator and indicates how consistent repeated measurements of the same parameter are under the same conditions [19]. In quantum sensing, a highly precise sensor will yield very similar readings upon repeated exposure to the same signal.

The Critical Distinction: A quantum algorithm can be precise but not accurate (e.g., consistently yielding a result that is systematically off from the true value due to a biased noise channel), or accurate but not precise (e.g., yielding a correct result on average, but with high variance across runs). The gold standard for quantum algorithms, particularly in metrology, is to achieve both high accuracy and high precision.

Quantum Fisher Information (QFI)

The Quantum Fisher Information (QFI) is a mathematical formalism that sets a fundamental limit on the precision of estimating an unknown parameter ( \lambda ) encoded in a quantum state ( \rho_\lambda ) [21]. It is the quantum analogue of the classical Fisher Information and provides the cornerstone of quantum metrology.

The QFI with respect to the parameter ( \lambda ) can be expressed using the spectral decomposition of the density matrix ( \rho\lambda = \sum{i=1}^N pi |\psii\rangle\langle\psii| ) as [21]: [ F\lambda = \underbrace{\sum{i=1}^M\frac{1}{pi}\left( \frac{\partial pi}{\partial \lambda} \right)^2}{\text{(I) Classical Contribution}} + \underbrace{\sum{i=1}^M pi F{\lambda,i}}{\text{(II) Pure-State QFI}} - \underbrace{\sum{i\ne j}^M\frac{8pipj}{pi + pj}\left| \langle\psii|\frac{\partial \psij}{\partial \lambda}\rangle \right|^2}{\text{(III) Mixed-State Correction}}. ] Here, ( F{\lambda,i} ) is the QFI for the pure state ( |\psii\rangle ). This formulation elegantly separates the QFI into a part (I) that resembles classical Fisher information, a part (II) from the weighted average of pure-state QFIs, and a part (III) that is a uniquely quantum term arising from the coherence in the state [21].

The paramount importance of the QFI is captured by the Quantum Cramér-Rao Bound (QCRB), which states that the variance ( \text{Var}(\hat{\lambda}) ) of any unbiased estimator ( \hat{\lambda} ) of the parameter ( \lambda ) is lower-bounded by the inverse of the QFI [21]: [ \text{Var}(\hat{\lambda}) \geq \frac{1}{F_\lambda}. ] This inequality confirms that the QFI directly quantifies the maximum achievable precision for parameter estimation—a higher QFI implies a potentially lower estimation error, representing a higher sensitivity in quantum sensing protocols [19] [21].

The Interplay of Metrics and Their Relation to Noise Resilience

Accuracy, precision, and QFI are deeply interconnected in the context of noise resilience. Environmental noise, modeled by quantum channels (e.g., depolarizing, amplitude damping), corrupts the ideal quantum state ( \rhot ) into a noisy state ( \tilde{\rho}t ) [19] [5]. This corruption invariably leads to a reduction in both accuracy (reduced fidelity) and the QFI (reduced potential precision), which in turn degrades the actual precision of the final estimate [19] [21].

Therefore, a noise-resilient quantum algorithm is defined by its ability to mitigate this degradation. Its goal is to preserve the QFI close to its theoretical maximum (e.g., the Heisenberg Limit for entangled states) and maintain high state fidelity, even in the presence of realistic noise, thereby ensuring that both the accuracy and precision of the final result are robust [19] [20]. For example, in variational quantum algorithms, a form of noise resilience can manifest as "optimal parameter resilience," where the location of the optimal parameters in the cost function landscape is unchanged by certain types of noise, even if the absolute value of the cost function is affected [5].

Quantitative Analysis of Metrics in Noisy Environments

The performance of quantum algorithms and metrology protocols under various noise channels can be quantitatively assessed by observing the behavior of accuracy (fidelity) and QFI. The following tables synthesize key experimental and simulation results from recent studies.

Table 1: Impact of Quantum Noise Channels on Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs). Adapted from [22] [23].

| Noise Channel | Key Effect on QNN Performance | Observed Relative Robustness | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depolarizing | Mixes the state with the maximally mixed state; broadly degrades coherence and information [5] [22]. | Low to Moderate | ||

| Amplitude Damping | Represents energy dissipation; transfers population from | 1⟩ to | 0⟩ [5] [21]. | Moderate |

| Phase Damping | Causes loss of quantum phase coherence without energy loss [5]. | High (for some tasks) | ||

| Bit Flip | Flips the state from | 0⟩ to | 1⟩ and vice versa with a certain probability [22] [23]. | Varies with encoding |

| Phase Flip | Introduces a random relative phase of -1 to the | 1⟩ state [22] [23]. | Varies with encoding |

Table 2: Performance Enhancement via Noise-Resilient Protocols in Quantum Metrology. Data from [19] [20].

| Experimental Platform | Noise-Resilient Protocol | Result on Accuracy (Fidelity) | Result on Precision (QFI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NV Centers in Diamond | qPCA on quantum processor | Enhanced by up to 200x under strong noise [19] [20] | Not Specified |

| Superconducting Processor (Simulated) | qPCA on quantum processor | Not Specified | Improved by 52.99 dB (v1) / 13.27 dB (v2), approaching Heisenberg Limit [19] [20] |

Table 3: Impact of Specific Dissipative Channels on QFI for a Dirac System. Data from [21].

| Noise Channel | Effect on QFI for Parameter ( \theta ) | Effect on QFI for Parameter ( \phi ) |

|---|---|---|

| Squeezed Generalized Amplitude Damping (SGAD) | Independent of squeezing variables (r, Φ) [21] | Independent of squeezing variables (r, Φ) [21] |

| Generalized Amplitude Damping (GAD) | Enhances to a constant value with increasing temperature (T) [21] | Surges around T=2 before complete loss [21] |

| Amplitude Damping (AD) | Decoheres initially with increasing ( \lambda ), then restores to initial value [21] | Decoheres with increasing ( \lambda ) [21] |

Experimental Protocols for Metric Evaluation

This section outlines detailed methodologies for key experiments that demonstrate the evaluation and enhancement of accuracy, precision, and QFI in noisy quantum systems.

Protocol 1: Noise-Resilient Quantum Metrology with Quantum Computing

This protocol, demonstrated using nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers and simulated superconducting processors, integrates a quantum sensor with a quantum computer to boost metrological performance [19] [20].

Objective: To enhance the accuracy and precision of estimating a magnetic field parameter under realistic noise conditions.

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of this hybrid quantum metrology and computing protocol.

Detailed Methodology:

System Initialization and Sensing:

- The protocol begins by initializing a quantum probe (e.g., an entangled state of NV center electron spins or superconducting qubits) into a known state ( \rho0 = |\psi0\rangle\langle\psi_0| ). Entangled states like GHZ states are often used to surpass the Standard Quantum Limit (SQL) and approach the Heisenberg Limit (HL) [19] [20].

- The probe evolves under the influence of the unknown parameter to be estimated. For magnetic field sensing, this is described by the unitary ( U\phi = e^{-i\phi} ), where ( \phi = \omega t ) is the phase accumulated over time ( t ) due to the field frequency ( \omega ). The ideal final state is ( \rhot = U\phi \rho0 U_\phi^\dagger ) [19] [20].

Noise Introduction and Modeling:

- The sensing process is subject to a realistic noise channel ( \Lambda ), which models environmental decoherence. The noisy evolution is a superoperator ( \tilde{\mathcal{U}}\phi = \Lambda \circ U\phi ). A simple model for the final noisy state is a mixture: [ \tilde{\rho}t = \Lambda(\rhot) = P0 \rhot + (1-P0) \tilde{N} \rhot \tilde{N}^\dagger, ] where ( P_0 ) is the probability of no error and ( \tilde{N} ) is a unitary noise operator [19].

Quantum State Transfer and Processing:

- Instead of direct classical measurement, the noisy quantum state ( \tilde{\rho}_t ) is transferred to a more stable and powerful quantum processor module. This is achieved via quantum state transfer or teleportation techniques, avoiding the classical data-loading bottleneck [19] [20].

- On the quantum processor, a noise-resilience protocol is applied. The referenced study uses Quantum Principal Component Analysis (qPCA), implemented via a variational quantum algorithm. qPCA acts as a quantum filter, extracting the dominant, information-rich components from the noisy density matrix ( \tilde{\rho}t ) and outputting a purified, noise-resilient state ( \rho{NR} ) [19] [20].

Measurement and Metric Calculation:

- The performance is quantified by comparing the state before and after processing.

- Accuracy: Computed as the fidelity ( F = \langle \psit | \rho{NR} | \psit \rangle ) of the processed state with the ideal target state ( |\psit\rangle ). The improvement is ( \Delta F = F - \tilde{F} ), where ( \tilde{F} ) is the fidelity of the raw noisy state [19].

- Precision (QFI): The Quantum Fisher Information of the state ( \rho_{NR} ) with respect to the parameter ( \phi ) is calculated. This measures the enhancement in the ultimate estimation precision, showing how close the protocol operates to the Heisenberg Limit [19] [20].

Protocol 2: Evaluating QFI Under Dissipative Noisy Channels

This protocol provides a methodology for theoretically and numerically analyzing the behavior of QFI when a quantum system interacts with a dissipative environment [21].

Objective: To scrutinize the impact of specific noise channels (AD, GAD, SGAD) on the QFI of a quantum state.

Workflow Overview: The logical flow for analyzing QFI under a noisy channel is structured as follows.

Detailed Methodology:

Initial State Preparation: The protocol begins with a well-defined initial quantum state ( \rho_0 ). Studies often use entangled states like Bell states or Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger (GHZ) states due to their high initial QFI and sensitivity to noise [21].

Noise Channel Selection and Kraus Operator Formalism: A specific dissipative channel is selected for analysis. The evolution of the initial state under this channel is described using the Kraus operator sum representation: [ \rho\lambda = \Phi(\rho0) = \sumk Ek \rho0 Ek^\dagger, ] where the Kraus operators ( {Ek} ) satisfy ( \sumk Ek^\dagger Ek = I ) and define the specific noise model (e.g., Amplitude Damping, Depolarizing) [5] [21].

Parameter Encoding and QFI Calculation: The noisy channel may itself encode a parameter ( \lambda ) (e.g., the damping parameter ( \lambda ) in an AD channel, or temperature in a GAD channel), or a parameter may be encoded after the noise action. The QFI ( F\lambda ) for estimating ( \lambda ) from the final state ( \rho\lambda ) is then computed. This typically involves the spectral decomposition of ( \rho_\lambda ) as shown in the theoretical section, which can be a non-trivial computational task [21].

Trend Analysis: The calculated QFI is analyzed as a function of the noise channel's parameters, such as the noise strength ( \lambda ) or the bath temperature ( T ). This reveals how different types of dissipation affect the fundamental limit of estimation precision. For instance, research has shown that in an AD channel, the QFI for one parameter can decohere and then recover with increasing noise strength, while for another parameter, it may vanish completely [21].

This section details the key hardware, software, and algorithmic "reagents" required to implement the noise-resilient protocols and evaluations described in this guide.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Noise-Resilient Quantum Algorithm Research.

| Tool / Resource | Category | Function and Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen-Vacancy (NV) Centers | Hardware Platform | A solid-state spin system used as a high-sensitivity quantum sensor for magnetic fields, temperature, and strain. Ideal for demonstrating hybrid metrology-computing protocols [19] [20]. |

| Superconducting Qubits | Hardware Platform | A leading quantum processor technology for building multi-qubit modules. Used as the processing unit in distributed quantum sensing simulations [19] [20]. |

| Parameterized Quantum Circuits (PQCs) | Algorithmic Component | The core of Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs). Used to implement ansätze for qPCA and other learning tasks, allowing for optimization on NISQ devices [19] [22]. |

| Quantum Principal Component Analysis (qPCA) | Algorithmic Protocol | A quantum algorithm used for noise filtering and feature extraction from a density matrix. It is a key subroutine for boosting the QFI and fidelity of noisy quantum states [19] [20]. |

| Kraus Operators | Theoretical Tool | The mathematical representation of a quantum noise channel. Essential for modeling and simulating the effects of decoherence (e.g., AD, GAD, SGAD) on quantum states and for calculating the resulting QFI [5] [21]. |

| Python (Mitiq, Qiskit, Cirq) | Software Framework | The de facto programming environment for quantum computing. Used for designing quantum circuits, simulating noise, and implementing error mitigation techniques like zero-noise extrapolation and probabilistic error cancellation [24]. |

| Fidelity Metric | Analytical Metric | A key measure of accuracy, quantifying the closeness of a processed quantum state to the ideal, noiseless target state [19] [20]. |

| Quantum Fisher Information (QFI) | Analytical Metric | The fundamental metric for evaluating the potential precision of a parameter estimation protocol, providing a bound on sensitivity and guiding the design of noise-resilient strategies [19] [21]. |

The rigorous quantification of quantum algorithmic performance through the triad of accuracy, precision, and Quantum Fisher Information is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for advancing the field into the realm of useful applications. As demonstrated, noise resilience is not an abstract property but one that can be systematically engineered, measured, and optimized using these metrics. Experimental protocols that leverage hybrid quantum-classical approaches and quantum-enhanced filtering like qPCA show a promising path forward, delivering order-of-magnitude improvements in both accuracy (200x fidelity enhancement) and potential precision (>10 dB QFI boost). For researchers in fields like drug development, where quantum simulation promises a significant edge, understanding these metrics is crucial for evaluating and leveraging emerging quantum technologies. The ongoing development of sophisticated error mitigation tools and noise-aware algorithmic design, underpinned by the clear-eyed application of these key metrics, is steadily closing the gap between the noisy reality of today's quantum hardware and their formidable theoretical potential.

The Impact of Noise on Algorithmic Performance in Near-Term Quantum Devices

Quantum computing represents a fundamental shift in computational paradigms, leveraging quantum mechanical phenomena to solve problems intractable for classical computers [25]. However, the practical utility of quantum devices remains constrained by unpredictable performance degradation under real-world noise conditions [25]. As we progress through the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, characterized by devices with 50-100 qubits that are highly susceptible to decoherence and gate errors, understanding and mitigating the impact of noise has become a critical research frontier [22]. This technical guide examines the multifaceted relationship between quantum noise and algorithmic performance, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for developing noise-resilient solutions for near-term quantum devices.

The challenge extends beyond mere error rates. Recent research reveals that algorithmic performance is exquisitely sensitive to problem structure itself, with pattern-dependent performance variations demonstrating a near-perfect correlation (r = 0.972) between pattern density and state fidelity degradation [25]. This structural dependency underscores the limitations of current noise models and highlights the need for problem formulations that minimize entanglement density and avoid symmetric encodings to achieve viable performance on current quantum hardware [25].

Foundations of Quantum Noise

Formal Noise Models and Characterization

Quantum noise is mathematically described via trace-preserving completely positive (CPTP) maps: Ï â†’ Φ(Ï) = ∑k EkÏEk†, where {Ek} are Kraus operators satisfying ∑k Ek†Ek = I [5]. Canonical models include distinct physical effects with varying impacts on algorithmic performance:

- Depolarizing Channel: {√(1-α)I, √(α/3)σx, √(α/3)σy, √(α/3)σz} — mixes the state with the maximally mixed state with probability α [5]

- Amplitude Damping: Operators E0 = [[1,0],[0,√(1-α)]] , E1 = [[0,√α],[0,0]] — transfers population from |1⟩ to |0⟩ [5]

- Phase Damping: Operators E0 = [[1,0],[0,√(1-α)]], E1 = [[0,0],[0,√α]] — damps phase coherence without population transfer [5]

At the physical level, superconducting qubits—a leading qubit technology—face significant noise challenges from material imperfections. Qubits are extremely sensitive to environmental disturbances such as electrical or magnetic fluctuations in surrounding materials [15]. This sensitivity leads to decoherence, where the coherent quantum state required for computation deteriorates. Recent fabrication advances include chemical etching processes that create partially suspended "superinductors" which minimize substrate contact, potentially eliminating a significant noise source and demonstrating an 87% increase in inductance compared to conventional designs [26].

Noise-Adaptive Algorithmic Frameworks

Noise-Adaptive Quantum Algorithms (NAQAs)

A promising approach for near-term devices is the emerging class of Noise-Adaptive Quantum Algorithms (NAQAs) designed to exploit rather than suppress quantum noise [27]. Rather than discarding imperfect samples from noisy quantum processing units (QPUs), NAQAs aggregate information across multiple noisy outputs. Because of quantum correlation, this aggregation can adapt the original optimization problem, guiding the quantum system toward improved solutions [27].

The NAQA framework follows a general pseudocode:

- Sample Generation: Obtain a sample set from a quantum program

- Problem Adaptation: Adjust the optimization problem based on insights from the sampleset

- Re-optimization: Re-solve the modified optimization problem

- Repeat: Iterate until satisfactory solution quality is reached or improvement plateaus [27]

This framework applies to both gate-based and annealing-based quantum computers, with the most subtle aspect lying in Step 2: extracting and aggregating information from many noisy samples to adjust the optimization problem [27].

Algorithmic Resilience Strategies

Multiple strategic approaches have demonstrated enhanced noise resilience:

Optimal Parameter Resilience: In variational hybrid quantum-classical algorithms (VHQCAs), the global minimum of the cost function remains unchanged under a wide class of incoherent noise models (depolarizing, Pauli, readout), even though absolute values may shift or scale [5]

Structural Noise Adaptation: Techniques like Noise-Directed Adaptive Remapping (NDAR) identify attractor states from noisy outputs and apply bit-flip gauge transformations, effectively steering the algorithm toward promising solutions [27]

Noise-Aware Circuit Learning (NACL): Task-driven, device-model-informed machine learning frameworks minimize task-specific noisy evaluation cost functions to produce circuit structures inherently adapted to a device's native gates and noise processes [5]

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Algorithm-Specific Noise Thresholds

The maintenance of quantum advantage requires noise levels to remain below specific thresholds, which vary by algorithm and noise type [5]:

Table: Noise Thresholds for Maintaining Quantum Advantage (C=0.95, 4 Qubits)

| Noise Model | Max. Tolerable α | Key Algorithms Affected |

|---|---|---|

| Depolarizing | ~0.025 | Quantum Search, Shor's Algorithm |

| Amplitude Damping | ~0.069 | VQE, Quantum Metrology |

| Phase Damping | ~0.177 | QFT-based Algorithms |

For quantum search, the advantage over classical O(N) search requires per-iteration noise below a small threshold (typically 0.01–0.2), with stricter requirements as register size grows [5].

Empirical Performance Degradation

Recent benchmarking studies reveal dramatic performance gaps between theoretical expectations and real-world execution:

Table: Bernstein-Vazirani Algorithm Performance Across Environments

| Execution Environment | Average Success Rate | State Fidelity | Performance Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal Simulation | 100.0% | 0.993 | Baseline |

| Noisy Emulation | 85.2% | 0.760 | 14.8% |

| Real Hardware | 26.4% | 0.234 | 58.8% |

Performance degrades dramatically from 75.7% success for sparse patterns to complete failure for high-density 10-qubit patterns, with quantum state tomography revealing a near-perfect correlation (r = 0.972) between pattern density and state fidelity degradation [25].

Hybrid Quantum Neural Networks Under Noise

Comparative analysis of Hybrid Quantum Neural Networks (HQNNs) reveals varying resilience to different noise channels [22]:

Table: HQNN Robustness Across Quantum Noise Channels

| HQNN Architecture | Phase Flip | Bit Flip | Phase Damping | Amplitude Damping | Depolarizing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN) | High | Medium | High | Medium | Medium |

| Quantum Convolutional Neural Network (QCNN) | Medium | Low | Medium | Low | Low |

| Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL) | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | Low |

In most scenarios, QuanNN demonstrates greater robustness across various quantum noise channels, consistently outperforming other models [22].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Pattern-Dependent Performance Benchmarking

Objective: To quantify the impact of problem structure on algorithmic performance under realistic noise conditions [25].

Experimental Setup:

- Platform: 127-qubit superconducting quantum processors [25]

- Benchmark Algorithm: Bernstein-Vazirani algorithm [25]

- Test Patterns: 11 diverse bitstring patterns with varying densities and symmetries [25]

- Comparison Environments: Ideal simulation, noisy emulation, and real hardware execution [25]

Methodology:

- Circuit Implementation: Implement BV algorithm for each test pattern with standard initialization, superposition, oracle application, and interference steps [25]

- Quantum State Tomography: Perform full quantum state tomography to characterize state fidelity degradation mechanisms [25]

- Statistical Analysis: Execute multiple runs (≥1000 shots) to establish statistical significance of success probabilities [25]

- Correlation Analysis: Compute correlation coefficients between pattern density and performance metrics [25]

Key Measurements:

- Algorithm success probability for each pattern [25]

- State fidelity via quantum state tomography [25]

- Pattern density metrics (Hamming weight, symmetry indices) [25]

Protocol: Noise-Adaptive Algorithm Implementation

Objective: To implement and validate noise-adaptive techniques that exploit rather than suppress quantum noise [27].

Experimental Setup:

- Platform: Noisy quantum devices (gate-based or annealing-based) [27]

- Adaptive Techniques: Noise-Directed Adaptive Remapping (NDAR), quantum-assisted greedy algorithms [27]

- Benchmark Problems: Sherrington-Kirkpatrick (SK) Ising models, practical optimization problems with power-law degree distributions [27]

Methodology:

- Sample Generation: Obtain sample set from quantum program under native noise conditions [27]

- Attractor State Identification: Apply statistical analysis to identify consensus states across multiple noisy outputs [27]

- Problem Transformation: Implement bit-flip gauge transformations or variable fixing based on correlation analysis [27]

- Iterative Refinement: Re-solve modified optimization problem and repeat until convergence [27]

Key Measurements:

- Solution quality improvement versus baseline methods (e.g., vanilla QAOA) [27]

- Computational overhead and runtime scaling [27]

- Success rate on practical versus synthetic problem instances [27]

Protocol: HQNN Noise Resilience Evaluation

Objective: To evaluate and compare the robustness of Hybrid Quantum Neural Networks against various quantum noise channels [22].

Experimental Setup:

- HQNN Architectures: Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN), Quantum Convolutional Neural Network (QCNN), Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL) [22]

- Noise Channels: Phase Flip, Bit Flip, Phase Damping, Amplitude Damping, Depolarization Channel [22]

- Task: Multiclass image classification on standardized datasets (e.g., MNIST) [22]

Methodology:

- Architecture Optimization: Identify best-performing circuit architectures for each HQNN type under noise-free conditions [22]

- Noise Injection: Systematically introduce quantum gate noise models at different probability levels [22]

- Performance Monitoring: Track validation accuracy and loss degradation across training epochs [22]

- Comparative Analysis: Evaluate relative performance preservation across noise channels and probabilities [22]

Key Measurements:

- Classification accuracy degradation under each noise channel [22]

- Training stability and convergence behavior [22]

- Relative robustness ranking across HQNN architectures [22]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Components for Noise-Resilient Algorithm Development

| Research Component | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Processors | Physical execution of quantum algorithms | 127-qubit superconducting processors (IBM) [25], Nitrogen-Vacancy centers in diamond [19] |

| Quantum Controllers with FPGA | Real-time noise management | Frequency Binary Search algorithm implementation for qubit frequency tracking [15] |

| Error Mitigation Software | Algorithmic error suppression | Zero-noise extrapolation, probabilistic error cancellation implemented in Python (Mitiq package) [24] |

| Noise Adaptation Frameworks | Exploitation of noise patterns | Noise-Directed Adaptive Remapping (NDAR) [27], Quantum-Assisted Greedy Algorithms [27] |

| Benchmarking Suites | Performance quantification | Pattern-dependent performance tests [25], HQNN comparative analysis frameworks [22] |

| Quantum State Tomography | Experimental state characterization | Full state reconstruction to validate fidelity metrics [25] |

| GANT 61 | GANT 61, CAS:500579-04-4, MF:C27H35N5, MW:429.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| L-NABE | L-NABE, CAS:7672-27-7, MF:C13H19N5O4, MW:309.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The path toward practical quantum advantage on near-term devices requires co-design of algorithms and hardware with noise resilience as a fundamental design principle. Noise-adaptive algorithmic frameworks demonstrate promising approaches to exploit rather than suppress the inherent noise in quantum systems [27]. The dramatic performance gaps between noisy emulation and real hardware execution—averaging 58.8% in recent studies—highlight the critical importance of structural awareness in algorithm design [25].

Future research directions should focus on developing more accurate noise models that capture pattern-dependent degradation effects, optimizing the trade-off between computational overhead and solution quality in adaptive approaches, and establishing comprehensive benchmarking standards that account for problem-structure dependencies. As quantum hardware continues to evolve toward higher-fidelity qubits and logical qubit implementations, the principles of noise resilience will remain essential for transforming theoretical quantum advantage into practical computational utility.

How Noise-Resilient Algorithms Work: Key Techniques and Biomedical Applications

Quantum computing in 2025 is firmly situated in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, characterized by quantum processors containing from tens to over a thousand physical qubits that suffer from environmental noise, short coherence times, and limited gate fidelities [28]. These hardware constraints prevent the execution of deep quantum circuits and purely quantum algorithms that require fault-tolerance. In this context, Hybrid Quantum-Classical Algorithms have emerged as the leading paradigm for extracting practical utility from existing quantum hardware [29] [30]. By strategically distributing computational tasks—delegating specific quantum subroutines to the quantum processor while leveraging classical computers for optimization, control, and error mitigation—these approaches create a synergistic framework that compensates for current hardware limitations [29].

Two of the most prominent hybrid algorithms are the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) for quantum chemistry and the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) for combinatorial optimization [28] [6]. Both operate on a similar principle: a parameterized quantum circuit prepares trial states whose properties are measured, and a classical optimizer adjusts the parameters based on measurement outcomes in an iterative feedback loop [30]. This architectural pattern makes them particularly suitable for NISQ devices because they utilize relatively shallow quantum circuits and inherently integrate strategies for noise resilience [29] [5]. This technical guide examines the core mechanisms, noise challenges, and practical implementations of VQE and QAOA, providing researchers with methodologies for deploying these algorithms effectively on contemporary noisy hardware.

Foundational Principles of Hybrid Quantum-Classical Algorithms

General Algorithmic Structure

Hybrid quantum-classical algorithms feature a well-defined, interactive architecture where quantum and classical computational resources work in concert through a dynamic feedback loop [30]. The quantum processing unit (QPU) handles state preparation, manipulation, and measurement—tasks that inherently benefit from quantum mechanics. Simultaneously, the classical central processing unit (CPU) orchestrates parameter updates, processes measurement statistics, and executes optimization routines [29] [30]. This cyclical process continues until convergence criteria are met, such as parameter stability or achievement of a target solution quality.

The core strength of this hybrid approach lies in its ability to leverage the complementary advantages of each computational paradigm: quantum systems can naturally represent and manipulate high-dimensional quantum states, while classical computers provide sophisticated optimization and error-correction capabilities [30]. This division of labor is particularly effective for current quantum hardware, as it minimizes quantum circuit depth and reduces the resource demands on the quantum processor [29].

Defining Noise Resilience in Quantum Algorithms