Noise-Resilient Quantum Machine Learning: Predicting Chemical Properties in the NISQ Era

This article explores the emerging paradigm of Quantum Machine Learning (QML) for predicting chemical properties, with a specific focus on overcoming the pervasive challenge of quantum hardware noise.

Noise-Resilient Quantum Machine Learning: Predicting Chemical Properties in the NISQ Era

Abstract

This article explores the emerging paradigm of Quantum Machine Learning (QML) for predicting chemical properties, with a specific focus on overcoming the pervasive challenge of quantum hardware noise. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview from foundational principles to practical applications. We detail how QML leverages quantum mechanics to process chemical data in exponentially large feature spaces, survey current noise-resilient algorithms and data encoding methods, and present optimization strategies for realistic, noisy quantum processors. The discussion is grounded in validation benchmarks and comparative analyses with classical machine learning, highlighting both the immediate potential and the path toward reliable, quantum-accelerated discovery in chemistry and biomedicine.

Quantum Foundations and the NISQ Challenge for Chemical Data

Core Concepts of Quantum Machine Learning in Chemistry

Quantum Machine Learning (QML) represents a transformative convergence of quantum computing and artificial intelligence, offering new paradigms for solving complex problems in chemistry. In computational chemistry, QML aims to leverage the inherent properties of quantum systems—such as superposition, entanglement, and interference—to model molecular systems and predict chemical properties with potentially greater efficiency than classical computers [1] [2] [3]. This quantum-chemical synergy is particularly valuable for simulating quantum mechanical phenomena that are computationally expensive for classical computers, such as electron interactions and molecular reactivity [4].

The operational framework of QML in chemistry typically follows a hybrid quantum-classical approach, especially on current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices [3]. In this model, quantum computers handle specific tasks like data encoding and quantum state preparation, while classical computers manage optimization and parameter updates [5] [3]. This division of labor allows researchers to harness quantum advantages while mitigating the limitations of current quantum hardware, including limited qubit counts, short coherence times, and inherent operational noise [3].

Key Applications and Performance Benchmarks

Quantum machine learning demonstrates significant potential across multiple chemistry domains, from molecular property prediction to materials discovery. The table below summarizes key applications and their reported performance benchmarks.

Table 1: QML Applications in Chemistry and Performance Benchmarks

| Application Area | Specific Task | QML Approach | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Property Prediction | HOMO-LUMO Gap Prediction [6] | Uni-Mol+ (3D Deep Learning) | MAE = 0.0914 on PCQM4MV2 validation set [6] |

| Polymer Informatics | Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) Prediction [5] | Quantum Circuit Learning (QCL) | Coefficient of Determination (R²) improved equally on actual quantum hardware and simulator [5] |

| Materials Discovery | Battery Material Screening [1] | Quantum Chemistry + ML | 32 million options narrowed to 1 top lithium-reducing material in less than a week [1] |

| Molecular Representation | Stereoelectronic Effect Encoding [7] | Stereoelectronics-Infused Molecular Graphs (SIMGs) | Better performance than standard molecular graphs with less data [7] |

Beyond these specific applications, QML approaches are being explored in quantum chemical property prediction [6], catalyst optimization [7], and drug discovery [1], where they can potentially reduce discovery timelines from years to significantly shorter periods by providing more accurate molecular simulations and property predictions.

Noise Challenges in NISQ-Era Quantum Hardware

Current quantum computers operate in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, characterized by hardware limitations that significantly impact QML algorithm performance [3]. These constraints include:

- Limited Qubit Count: Current devices typically have 50-100 qubits, restricting algorithm complexity [3].

- Short Coherence Times: Qubits rapidly lose quantum properties due to environmental interference, limiting computation duration [3].

- Operational Noise: Various noise sources including decoherence, gate errors, and measurement errors introduce inaccuracies in computations [3].

These noise sources collectively degrade QML model performance by introducing errors in predictions, hindering optimization convergence, and potentially eliminating any quantum advantage for practical chemical applications [8] [3]. As quantum computations scale for complex chemical systems, these noise effects become increasingly problematic, necessitating robust mitigation strategies.

Noise-Resilient QML Methodologies and Protocols

Quantum Circuit Learning with Robust Optimization

For predicting polymer properties like glass transition temperature (Tg), a robust Quantum Circuit Learning protocol has been demonstrated effectively on both simulators and actual quantum hardware [5].

Table 2: Key Components of Noise-Resilient Quantum Circuit Learning

| Component | Description | Function in Noise Resilience |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Scale Entanglement Renormalization Ansatz (MERA) | A specific quantum circuit architecture [5] | Improves prediction accuracy without increasing parameter count, reducing susceptibility to noise [5] |

| Stochastic Gradient Descent with Parameter-Shift Rule | Optimization method for training [5] | Demonstrates robustness to stochastic variations in expected values due to finite sampling [5] |

| Data Preprocessing | Principal Component Analysis + Min-Max Normalization [5] | Reduces computational complexity and adapts data for quantum circuit constraints [5] |

| Objective Function | Mean Square Error [5] | Standard loss function for regression tasks, optimized with noise-resistant techniques [5] |

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Preparation: Utilize 86 monomer-polymer property datasets generated by computational tools. Calculate 10 monomer features as explanatory variables and glass transition temperature as the target variable [5].

- Feature Engineering: Apply Principal Component Analysis to explanatory variables, retaining first four principal components. Apply min-max normalization to adapted features for quantum encoding [5].

- Quantum Encoding: Encode preprocessed features into quantum states using parameterized quantum circuits with rotation gates [5].

- Model Training: Implement stochastic gradient descent with parameter-shift rule for gradient calculation. Use MERA circuit architecture to balance expressibility and noise resilience [5].

- Validation: Evaluate model performance using coefficient of determination (R²) on both quantum simulator and actual IonQ quantum computer to verify noise resilience [5].

Learning Robust Observables

A novel approach to noise resilience focuses on learning custom observables that remain stable under noisy conditions rather than using fixed observables like Pauli matrices [8].

Experimental Protocol:

- Problem Formulation: Define the learning objective as minimizing the difference in expectation values of observables before and after noise introduction: min‖⟨O⟩−⟨O⟩̃‖², where O is the learned observable [8].

- Noise Simulation: Subject quantum states to various noise channels including depolarization, amplitude damping, phase damping, bit flip, and phase flip channels [8].

- Model Training: Train machine learning models to identify observables that demonstrate minimal deviation in expectation values across different noise conditions [8].

- Validation: Test learned observables on diverse quantum circuits including Bell state circuits, Quantum Fourier Transform circuits, and highly entangled random circuits [8].

Advanced 3D Conformation-Based Prediction

For accurate quantum chemical property prediction, the Uni-Mol+ framework leverages 3D molecular conformations with specialized noise-resilient techniques [6].

Experimental Protocol:

- Conformation Generation: Generate initial 3D conformations from molecular structures using RDKit with ETKDG method, at a cost of approximately 0.01 seconds per molecule [6].

- Conformation Refinement: Implement iterative updates of 3D coordinates toward DFT equilibrium conformation using a two-track transformer model with atom and pair representation tracks [6].

- Trajectory Sampling: During training, sample conformations from pseudo trajectories between RDKit-generated conformations and DFT equilibrium conformations using a mixture of Bernoulli and Uniform distributions [6].

- Property Prediction: Predict quantum chemical properties from the refined conformations, demonstrating significant improvements over 1D/2D molecular representation approaches [6].

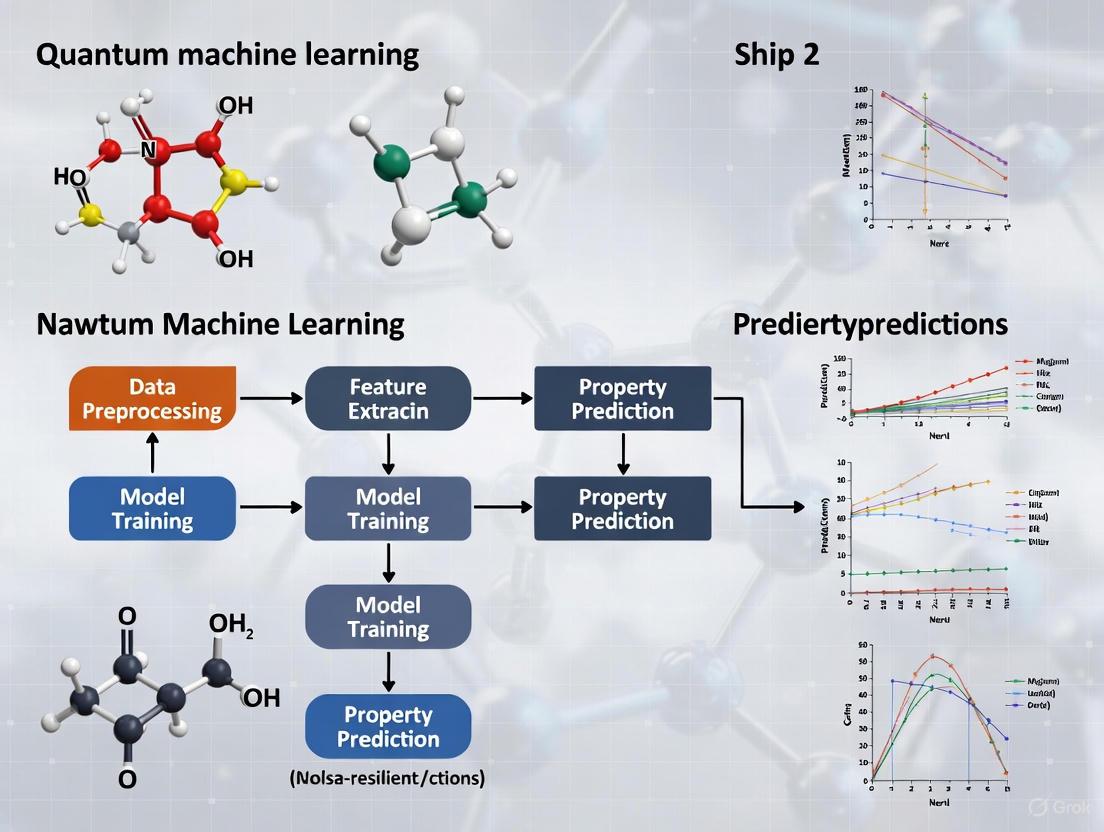

Diagram 1: Hybrid quantum-classical workflow for chemical property prediction

Table 3: Essential Resources for QML in Chemistry Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Frameworks | Application in QML Chemistry Research |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Programming Frameworks | Qiskit (IBM), PennyLane (Xanadu), Cirq (Google) [3] | Provide tools for building, simulating, and running QML algorithms on real hardware and simulators [3] |

| Quantum Hardware Providers | IonQ, IBM Quantum Systems [5] | Enable real-world testing and validation of QML algorithms on actual quantum processors [5] |

| Computational Chemistry Tools | RDKit, Synthia (Materials Studio) [5] [6] | Generate molecular descriptors, 3D conformations, and reference property data for model training [5] [6] |

| Specialized Representations | Stereoelectronics-Infused Molecular Graphs (SIMGs) [7] | Incorporate quantum-chemical orbital interactions into machine learning representations [7] |

| Noise Mitigation Techniques | Zero-Noise Extrapolation, Measurement Error Mitigation, Dynamic Decoupling [3] | Improve result accuracy from noisy quantum computations without full error correction [3] |

Diagram 2: 3D conformation refinement workflow for accurate property prediction

The integration of quantum machine learning into chemical research represents a paradigm shift in molecular discovery and property prediction. Current research demonstrates that QML approaches can already provide tangible benefits in specific chemical applications, particularly when designed with noise resilience as a fundamental principle [5] [6]. The continued development of hybrid quantum-classical algorithms, advanced noise mitigation techniques, and quantum-native chemical representations will further enhance the capabilities of QML in chemistry [7] [3].

As quantum hardware continues to evolve with increasing qubit counts, longer coherence times, and improved gate fidelities, the applications of QML in chemistry will expand accordingly [2] [3]. Future directions include extending these methods to broader regions of the periodic table, applying them to complex spectroscopic characterization, and scaling to larger molecular systems such as peptides and proteins [7]. For researchers in chemistry and drug development, engaging with QML technologies now provides a pathway to develop domain-specific expertise that will become increasingly valuable as quantum computing continues to mature.

The advent of the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era marks a critical phase in the development of quantum computing. Coined by John Preskill, this term describes the current generation of quantum hardware, characterized by processors containing from approximately 50 to several hundred qubits that operate without full error correction [9] [10] [11]. For researchers in computational chemistry and drug development, these devices present both unprecedented opportunities and significant challenges for predicting chemical properties.

The fundamental challenge in the NISQ era lies in the delicate balance between scale and reliability. While current devices possess sufficient qubit counts to encode meaningful molecular problems, their computational fidelity is severely constrained by intrinsic physical limitations. Quantum information is exceptionally fragile, and the slightest environmental interference can disrupt calculations, leading to decoherence and operational errors that accumulate throughout quantum circuits [9] [11]. This noise sensitivity presents particular difficulties for quantum machine learning (QML) applications in chemical property prediction, where accurate energy landscape calculations require sustained quantum coherence through deep circuit structures.

Understanding these hardware limitations is not merely an engineering concern but a fundamental prerequisite for designing effective quantum computational chemistry protocols. The exponential resource requirements for error correction illustrate the magnitude of the challenge: estimates suggest that a modest 1,000 logical-qubit processor suitable for complex chemical simulations could require approximately one million physical qubits given current error rates [9]. This overhead renders full fault-tolerance impractical with contemporary technology, necessitating alternative strategies for extracting useful chemical insights from imperfect quantum computations.

Quantitative Analysis of NISQ Hardware Limitations

The performance constraints of NISQ devices can be systematically categorized and quantified across several physical and operational parameters. For chemical property prediction research, understanding these specific limitations is crucial for designing feasible experiments and setting realistic expectations for computational accuracy.

Table 1: Key NISQ Hardware Limitations and Their Impact on Chemical Computations

| Parameter | Current NISQ Specifications | Impact on Chemical Computations |

|---|---|---|

| Qubit Count | 20-5000+ physical qubits (vendor-dependent) [9] [12] | Limits molecular system size; insufficient for full error correction |

| Gate Fidelity | 99.9% for best superconducting devices; slightly lower for ions/atoms [9] | Accumulated errors limit maximum circuit depth for accurate simulation |

| Coherence Times (T1/T2) | Typically microseconds to milliseconds [13] | Constrains total algorithm execution time before quantum information decays |

| Two-Qubit Gate Error Rates | ~0.1% on best superconducting devices [9] | Critical for entanglement operations essential for molecular orbital simulations |

| Error Correction Overhead | ~1000 physical qubits per logical qubit estimated [9] [11] | Makes fault-tolerant chemical calculations impractical with current technology |

These hardware constraints directly impact the feasibility of quantum computational chemistry applications. For instance, while a quantum computer might theoretically excel at simulating molecular systems like the FeMo-cofactor of nitrogenase (a computation believed to require around 4 million qubits), current NISQ devices cannot support this scale of computation with sufficient accuracy [12]. Similarly, the limited coherence times restrict the depth of quantum circuits that can be executed before decoherence degrades the results, creating a fundamental trade-off between computational complexity and accuracy [13].

The hardware-specific error profiles further complicate algorithm design. Different qubit technologies (superconducting, trapped ions, neutral atoms) exhibit distinct error characteristics, with varying ratios of coherence limits to gate fidelities [9]. This technological diversity means that chemical computations optimized for one hardware platform may perform poorly on another, necessitating hardware-aware algorithm design tailored to specific device capabilities and limitations.

Noise and Decoherence: Fundamental Challenges for Quantum Computations

Physical Origins and Manifestations

In quantum computing for chemical applications, noise refers to any unwanted interaction that disrupts the ideal evolution of a quantum state, while decoherence specifically describes the loss of quantum coherence through environmental interactions. These phenomena represent the most significant barriers to reliable quantum computation in the NISQ era [11].

The physical origins of these limitations are rooted in the extreme sensitivity of qubits to their environment. For superconducting qubits, which operate at cryogenic temperatures, even minute thermal fluctuations or stray electromagnetic fields can cause decoherence. As noted in one analysis, "a microwave operating across the street can disrupt the quantum states, resulting in a loss of these states due to quantum decoherence" [11]. This environmental sensitivity means that maintaining qubit integrity requires extraordinary isolation measures that remain imperfect in current implementations.

The primary manifestations of these limitations include:

Gate Errors: Each fundamental quantum operation has a probability of incorrect execution. With current fidelity rates of 99.9%, a quantum circuit with thousands of gates—as required for meaningful chemical simulations—accumulates significant errors [9].

Decoherence Times (T1 and T2): The T1 time represents energy relaxation, while T2 represents phase coherence loss. Both typically range from microseconds to milliseconds in current devices, creating strict windows for computation [13].

Measurement Errors: The process of reading qubit states introduces additional inaccuracies, with error rates typically below 1% but contributing significantly to overall result uncertainty [9].

Crosstalk: Unwanted interactions between adjacent qubits during gate operations can corrupt computations, particularly in densely connected qubit architectures [10].

For chemical property prediction, these error sources manifest as inaccuracies in calculated molecular energies, incorrect geometric configurations, and unreliable reaction barrier predictions. The challenge is particularly acute for transition states and weakly-bound complexes where energy differences are small relative to computational error margins.

Impact on Quantum Machine Learning for Chemical Prediction

Quantum machine learning approaches for chemical property prediction face specific vulnerabilities to NISQ-era limitations. The barren plateaus phenomenon, where gradients in parameterized quantum circuits vanish exponentially with system size, renders many QML models untrainable under noise conditions [14] [15]. Additionally, the winner's curse statistical bias—where the lowest observed energy in variational algorithms appears better than the true value due to noise—can mislead optimization and produce incorrect chemical predictions [14].

These challenges necessitate specialized approaches for chemical applications. As demonstrated in recent research, "hybrid quantum-neural wavefunction" methods that combine quantum circuits with classical neural networks can achieve "near-chemical accuracy" while maintaining "significant resilience to noise" on superconducting quantum computers [16]. This resilience stems from distributing the computational burden across quantum and classical subsystems, leveraging the strengths of each while mitigating their respective limitations.

Hardware-Aware Algorithmic Strategies for Chemical Applications

Hybrid Quantum-Classical Approaches

The most successful strategy for practical quantum computational chemistry in the NISQ era involves hybrid quantum-classical algorithms that partition computations between quantum and classical processors. In these frameworks, the quantum computer handles specific subroutines that potentially provide quantum advantage, while classical computers manage optimization, control, and error mitigation [16] [17] [3].

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) exemplifies this approach for chemical applications. In VQE, a parameterized quantum circuit prepares trial wavefunctions for molecular systems, while a classical optimizer adjusts parameters to minimize the energy expectation value [16] [14]. This division of labor accommodates NISQ constraints by allowing relatively short quantum circuit executions while leveraging robust classical optimization techniques.

Recent advances have demonstrated sophisticated hybrids specifically designed for chemical accuracy under noise constraints. The pUNN (paired unitary coupled-cluster with neural networks) approach employs "an efficient quantum circuit and a neural network" to learn molecular wavefunctions, achieving "near-chemical accuracy, comparable to advanced quantum and classical techniques" while demonstrating "high accuracy and significant resilience to noise" on superconducting quantum hardware [16]. This hybrid design uses quantum circuits to capture quantum phase structures—challenging for classical networks—while neural networks correct amplitudes, creating a synergistic combination that enhances noise resilience.

Table 2: Hybrid Algorithm Strategies for Chemical Property Prediction

| Algorithm Type | Key Mechanism | Advantages for NISQ Chemistry | Proven Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| VQE (Variational Quantum Eigensolver) | Parameterized quantum circuit with classical optimization [14] | Short quantum executions; noise resilience through classical outer loop | Molecular ground state energy calculations [14] |

| Quantum Echo-State Networks (QESN) | Reservoir computing approach using quantum dynamics [13] | Naturally handles noise as part of computational model; persistent memory | Chaotic system prediction; running "100 times longer than median T1/T2 times" [13] |

| Quantum-Neural Hybrid (pUNN) | Quantum circuit for phase structure + neural network for amplitudes [16] | Complementary strengths; enhanced expressivity with noise resistance | Molecular energy computation; isomerization reaction barriers [16] |

| QAOA (Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm) | Alternating operator sequences for combinatorial problems [15] | Handles discrete optimization problems relevant to molecular conformation | Molecular structure optimization; portfolio optimization [15] |

Error Mitigation Techniques

Beyond algorithmic strategies, specific error mitigation techniques have been developed to extract more accurate results from noisy quantum computations without the overhead of full error correction. These techniques are particularly valuable for chemical property prediction, where small energy differences have significant chemical implications.

Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE): This method involves deliberately running quantum circuits at increased noise levels (through stretched gates or identity insertions) and extrapolating results back to the zero-noise limit [9] [3]. For chemical applications, ZNE can improve energy estimates, though the sampling overhead grows with circuit size.

Measurement Error Mitigation: By characterizing the measurement error matrices for individual qubits through calibration experiments, researchers can apply classical post-processing to correct readout errors in chemical computations [3]. This is particularly effective for expectation value estimation in molecular energy calculations.

Probabilistic Error Cancellation: This advanced technique constructs quasi-probability distributions to invert specific error channels, effectively canceling out systematic errors in quantum computations [9]. While resource-intensive, it can significantly improve accuracy for critical chemical predictions.

Dynamic Decoupling: Applying carefully timed sequences of pulses to idle qubits can decouple them from environmental noise, effectively extending coherence times during quantum computations [3]. This is especially valuable for chemical simulations with inherent latency between operations.

The implementation of these techniques in chemical applications demonstrates measurable improvements. As noted in one study, error mitigation has enabled "valuable experiments" including "random circuit sampling tasks on a 103-qubit processor with 40 layers of two-qubit gates" [9], representing significant progress toward chemically relevant circuit depths.

Experimental Protocols for Noise-Characterization in Chemical Computations

Quantum Hardware Benchmarking Protocol

Before executing chemical computations on NISQ hardware, comprehensive characterization of device-specific noise profiles is essential. The following protocol provides a standardized approach for assessing hardware suitability for chemical property prediction tasks:

Basic Parameter Verification

- Confirm qubit count exceeds molecular orbital count for target chemical system

- Verify T1 and T2 coherence times exceed estimated circuit execution time

- Check native gate set compatibility with chosen quantum chemistry algorithm

Gate Fidelity Assessment

- Execute randomized benchmarking for single-qubit gate error rates

- Perform interleaved randomized benchmarking for two-qubit gate fidelities

- Characterize spatial variations in gate performance across qubit array

Connectivity and Crosstalk Evaluation

- Map hardware qubit connectivity graph against algorithm requirements

- Measure simultaneous gate operation crosstalk errors

- Identify optimal qubit subsets for chemical computation

Measurement Error Characterization

- Prepare and measure all computational basis states for error matrix construction

- Determine readout fidelity for each qubit

- Establish measurement error correlations between adjacent qubits

This characterization protocol typically requires 4-8 hours of dedicated hardware access and provides essential data for algorithm selection and parameter tuning specific to chemical applications.

Noise-Resilient VQE Implementation for Molecular Energy Calculations

For calculating molecular energies on NISQ hardware, the following protocol implements a noise-resilient Variational Quantum Eigensolver:

Diagram 1: Noise-resilient VQE workflow for molecular energy calculation

Protocol Steps:

Molecular Hamiltonian Preparation

- Perform classical Hartree-Fock calculation for molecular system

- Transform electronic Hamiltonian to qubit representation using Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation

- Apply qubit reduction techniques (parity, tapering) to minimize qubit requirements

Ansatz Selection and Parameter Initialization

- Choose hardware-efficient ansatz compatible with device connectivity

- Initialize parameters using chemical intuition or classical approximations

- Implement parameter shift rules for gradient calculation if using gradient-based optimization

Iterative Optimization Loop

- Execute quantum circuit with current parameters (minimum 10,000 shots for statistical significance)

- Apply measurement error mitigation to expectation values

- Use robust classical optimizers (CMA-ES or iL-SHADE recommended for noisy environments) [14]

- Monitor for barren plateaus through gradient magnitude checks

Result Validation and Error Analysis

- Compare with classical methods (CCSD, DMRG) where feasible

- Estimate systematic errors through multiple protocol executions

- Report final energy with statistical confidence intervals

This protocol typically converges in 50-200 iterations depending on molecular complexity and noise conditions, with the quantum subroutine requiring 1-5 minutes per iteration on current hardware.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Computational Chemistry

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Chemical Research |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Programming Frameworks | Qiskit (IBM), PennyLane (Xanadu), Cirq (Google) [3] | Circuit design, noise simulation, and hardware interface for chemical algorithms |

| Classical Computational Chemistry Packages | PySCF, FermiNet, PauliNet [16] | Provide benchmarks, initial parameters, and hybrid computation components |

| Error Mitigation Modules | M3 (measurement mitigation), ZNE (zero-noise extrapolation) [3] | Improve accuracy of quantum computations without full error correction |

| Quantum Chemistry Ansätze | UCCSD, pUCCD, hardware-efficient ansätze [16] [14] | Encode molecular wavefunctions into parameterized quantum circuits |

| Classical Optimizers | CMA-ES, iL-SHADE, SPSA [14] | Robust parameter optimization resistant to noise-induced false minima |

| Molecular Datasets | PubChem Quantum Chemistry Dataset [16] | Provide benchmark systems for method validation and development |

This toolkit represents the essential software and methodological components for conducting chemical property prediction research on current NISQ devices. The integration across these domains enables the hybrid approaches necessary for extracting chemically meaningful results from noisy quantum computations.

Particularly noteworthy is the evolving synergy between classical computational chemistry methods and quantum approaches. As demonstrated in recent research, neural network quantum states (such as FermiNet and PauliNet) "demonstrate accuracy comparable to Coupled Cluster with Single and Double excitations (CCSD) but with significantly lower computational scaling" [16], making them valuable both as standalone methods and as components in hybrid quantum-classical frameworks. This interdisciplinary integration characterizes the most promising directions for NISQ-era quantum computational chemistry.

The NISQ era presents a complex landscape for quantum computational chemistry, defined by the tension between substantial theoretical potential and persistent hardware limitations. Current devices, while continuously improving, face fundamental constraints in qubit counts, coherence times, and gate fidelities that restrict their application to chemical discovery. However, through carefully designed hybrid algorithms, specialized error mitigation techniques, and hardware-aware experimental protocols, researchers can already extract chemically relevant insights from these imperfect devices.

The path forward involves continued co-design of algorithmic and hardware solutions, with particular emphasis on error-resilient approaches that can bridge the gap between current capabilities and future fault-tolerant systems. As hardware progresses through what researchers term the "megaquop, gigaquop, and teraquop eras" [9], each stage will unlock new opportunities for chemical prediction. The most immediate applications will likely focus on specific subproblems where quantum approaches offer clear advantages, such as strongly correlated electron systems and reaction dynamics involving conical intersections.

For researchers in drug development and chemical design, engagement with NISQ-era quantum computing requires realistic assessment of both capabilities and limitations. While transformative applications remain years away, the current period offers valuable opportunities for methodology development, benchmark establishment, and preliminary exploration of quantum advantage in specific chemical contexts. By understanding and working within current hardware constraints, the chemical research community can position itself to fully leverage quantum computational power as hardware capabilities continue their steady advancement toward fault-tolerant quantum computing.

The emerging field of quantum machine learning (QML) holds significant promise for advancing computational chemistry, potentially revolutionizing areas such as drug discovery and materials science by providing accelerated and more accurate predictions of molecular properties [18] [19]. A central challenge in this domain, often termed "The Data Problem," is the effective encoding of classical molecular information into quantum states that can be processed by quantum algorithms. The chosen encoding scheme directly impacts the resource requirements on near-term intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) hardware, the model's resilience to noise, and its ultimate predictive performance [18] [19]. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for prevalent molecular encoding strategies, contextualized within research aimed at achieving noise-resilient chemical property prediction.

Molecular Encoding Schemes: A Comparative Analysis

Molecular encoding, or featurization, transforms a molecule's structure into a fixed-dimensional representation suitable for computational models. The following table summarizes the core characteristics of major encoding approaches relevant to QML.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Molecular Encoding Methods for QML

| Encoding Method | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Notable Implementations/Frameworks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Molecular Structure Encoding (QMSE) [18] [19] | Encodes a hybrid Coulomb-adjacency matrix directly as parameterized one- and two-qubit rotation gates. | High interpretability; Improved state separability; Shallow, hardware-efficient circuits; Scalable via chain contraction. | Requires classical pre-computation of matrix; Circuit structure depends on molecular size. | Custom implementation based on literature specifications. |

| Fingerprint / Angle Encoding [19] | Maps a fixed-length molecular fingerprint (e.g., RDKit fingerprint) to qubit rotation angles. | Simple and widely applicable; Low qubit requirement with amplitude encoding. | Poor state separation; High circuit depth for amplitude encoding; Can lead to barren plateaus. | Built into most QML software stacks (Qiskit, Pennylane). |

| Classical Learnable Representations [20] | Uses neural networks (e.g., Graph Neural Networks) to learn optimal molecular representations from data. | Powerful performance on many benchmarks; Automates feature engineering. | Struggles with data scarcity; Can be a "black box"; High computational cost for training. | DeepChem [20], MoleculeNet [20]. |

| 3D Conformation-Aware Encoding [21] | Utilizes the 3D equilibrium geometry of a molecule as input, often refined towards DFT-quality structures. | High accuracy for quantum chemical properties; Physically grounded. | Computationally expensive to generate 3D conformations; Sensitive to conformational noise. | Uni-Mol+ [21]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Quantum Molecular Structure Encoding (QMSE)

This protocol details the steps to implement the QMSE scheme, which has demonstrated superior state separability and noise resilience for molecular classification and regression tasks [18] [19].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for QMSE Implementation

| Item | Function/Description | Example Source/Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure File | Input data; typically a SMILES string or .mol file. | PubChem Database, RDKit |

| RDKit Chemistry Library | Open-source toolkit for generating molecular graphs, bond orders, and initial 3D conformations. | https://www.rdkit.org |

| Hybrid Coulomb-Adjacency Matrix | A custom matrix combining topological and electronic structure information for encoding. | Calculated via custom script (see Step II.2). |

| Quantum Simulator/Hardware | Platform to execute the parameterized quantum circuit. | IBM Qiskit, Google Cirq, Amazon Braket |

| Parameterized Quantum Circuit (PQC) | A quantum circuit with tunable parameters for the machine learning task. | Custom ansatz using QMSE feature map. |

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

Molecular Input and Pre-processing:

- Begin with a SMILES string representation of the target molecule (e.g., Ethanol: "CCO").

- Use the RDKit library to parse the SMILES string, generate a 2D molecular graph, and assign bond orders. Generate an initial 3D conformation using RDKit's ETKDG method.

Construct the Hybrid Coulomb-Adjacency Matrix (H):

- The matrix H is defined for a molecule with N atoms.

- The diagonal elements Hᵢᵢ represent the atomic number or other atomic property of the i-th atom.

- The off-diagonal elements Hᵢⱼ for i ≠j are a function of the bond order BOᵢⱼ and the interatomic Coulomb potential: Hᵢⱼ = BOᵢⱼ / |rᵢ - rⱼ|, where |rᵢ - rⱼ| is the Euclidean distance between atoms i and j in the generated 3D conformation.

- This matrix directly encapsulates the molecule's unique chemical identity.

Map Matrix to Quantum Circuit:

- The elements of H are normalized and used as parameters for rotation gates.

- Single-qubit rotations: The normalized diagonal elements of H are used as angles for R_y or R_z rotations on qubits representing each atom.

- Two-qubit entangling gates: The normalized off-diagonal elements Hᵢⱼ are used as angles for parameterized two-qubit interaction gates (e.g., R_{XX} or R_{ZZ}) between qubits i and j, creating entanglement that reflects molecular connectivity.

Integrate into a QML Workflow:

- The resulting parameterized circuit serves as the data-encoding layer (feature map) for a downstream QML model, such as a Variational Quantum Classifier or a Quantum Neural Network.

- Train the model by adjusting the parameters of a subsequent variational ansatz to minimize a loss function (e.g., mean-squared error for property prediction).

Diagram 1: QMSE encoding workflow.

Protocol 2: Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunction for Molecular Energy Calculation

This protocol outlines the procedure for using a hybrid quantum-neural network, specifically the pUNN method, to achieve noise-resilient and accurate prediction of molecular energies [16].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for pUNN Implementation

| Item | Function/Description | Example Source/Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Hamiltonian | The quantum mechanical operator representing the system's energy; defines the problem. | Generated via PySCF or OpenFermion. |

| pUCCD Ansatz Circuit | A shallow, paired unitary coupled-cluster ansatz that captures correlation in the seniority-zero subspace. | Custom circuit built with quantum computing framework. |

| Classical Neural Network | A feed-forward network that corrects amplitudes for configurations outside the seniority-zero subspace. | PyTorch, TensorFlow with ~2KN neurons/layer. |

| Quantum Computer/Simulator | To execute the pUCCD circuit and measure expectations. | Noisy quantum simulator or real NISQ hardware. |

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

System Setup and Hamiltonian Generation:

- Define the molecular geometry (e.g., Nâ‚‚ or cyclobutadiene) and basis set.

- Use a classical quantum chemistry package (e.g., PySCF) to generate the second-quantized electronic Hamiltonian in terms of Pauli operators via the Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation.

Prepare the Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunction (pUNN):

- Quantum Circuit (pUCCD): Construct and initialize the pUCCD ansatz on N qubits. This circuit is responsible for learning the phase structure within the seniority-zero subspace.

- Hilbert Space Expansion: Add N ancilla qubits, initialized to |0⟩. Apply a shallow perturbation circuit (e.g., small-angle R_y rotations) to these ancillas.

- Entanglement: Apply a layer of CNOT gates, entangling each original qubit with its corresponding ancilla. This creates a state in a 2N-qubit Hilbert space.

- Neural Network Operator: Apply a classical neural network as a non-unitary post-processing operator. The NN takes the bitstring |k⟩ ⊗ |j⟩ (from the original and ancilla registers) as input and outputs a coefficient b_{kj}, modulated by a particle-number-conserving mask.

Compute the Energy Expectation Value:

- The energy is calculated as E = ⟨Ψ|Ĥ|Ψ⟩ / ⟨Ψ|Ψ⟩, where |Ψ⟩ is the full hybrid wavefunction.

- The measurement protocol is designed to compute these expectations efficiently without full quantum state tomography, by leveraging the structure of the pUCCD ansatz and the classical NN [16].

Joint Optimization:

- The parameters of both the quantum circuit (pUCCD) and the classical neural network are optimized simultaneously using a classical optimizer (e.g., Adam or L-BFGS) to minimize the energy expectation value E.

Diagram 2: Hybrid pUNN architecture.

Benchmarking and Validation

To ensure the validity and performance of any encoding scheme or QML model, rigorous benchmarking on standardized datasets is essential.

Recommended Benchmark Datasets:

- MoleculeNet: A large-scale benchmark collection encompassing multiple public datasets for molecular machine learning, including quantum mechanics (e.g., QM9), physical chemistry (e.g., ESOL), and biophysics tasks [20]. It provides standardized data splits and metrics.

- PubChemQCR: A large-scale dataset of molecular relaxation trajectories, useful for benchmarking methods that predict energies and forces on non-equilibrium geometries [22].

- PCQM4MV2: A dataset of ~4 million molecules for HOMO-LUMO gap prediction, commonly used to benchmark 3D conformation-aware models [21].

Evaluation Metrics:

- Regression Tasks (Energy Prediction): Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE).

- Classification Tasks (Phase Prediction): Accuracy, AUC-ROC.

- Quantum-Specific Metrics: Circuit depth, number of qubits, susceptibility to noise (e.g., performance drop under noise simulation).

The application of quantum machine learning (QML) to chemical property prediction represents a paradigm shift in computational chemistry and drug discovery. At the core of this transformation lie two fundamental quantum mechanical properties: superposition and entanglement. These properties enable quantum computers to map chemical data into feature spaces that are computationally intractable for classical systems. In the context of noise-resilient chemical property prediction, understanding and harnessing these advantages is crucial for developing next-generation QML models that can operate effectively on current noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. This application note details the theoretical foundations, practical implementations, and experimental protocols for leveraging superposition and entanglement in chemical feature mapping, with specific emphasis on creating robust models for predicting molecular properties despite hardware limitations.

Quantum feature mapping refers to the process of encoding classical chemical data (such as molecular structures or electronic properties) into quantum states through carefully designed quantum circuits. Unlike classical encoding methods, quantum feature maps can exploit the exponentially large Hilbert space available to quantum systems, enabling the detection of complex, non-linear relationships in chemical data that often challenge classical machine learning approaches. The unique advantage of quantum feature mapping stems from the inherent parallel processing capabilities of superposition states and the rich correlation structures enabled by entanglement, which together facilitate more expressive representations of chemical systems.

Theoretical Framework: Superposition and Entanglement in Feature Mapping

The Superposition Advantage in Chemical Space Exploration

Quantum superposition allows a qubit to exist in multiple states simultaneously, unlike classical bits that are confined to definite 0 or 1 states. This property provides quantum systems with innate parallel processing capabilities that are particularly advantageous for exploring complex chemical spaces. When applied to chemical feature mapping, superposition enables the simultaneous representation of multiple molecular configurations, structural features, or electronic states within a single quantum state.

Mathematically, a single qubit in superposition can be represented as (|\psi\rangle = \alpha|0\rangle + \beta|1\rangle), where (\alpha) and (\beta) are complex probability amplitudes satisfying (|\alpha|^2 + |\beta|^2 = 1). For a system of (n) qubits, this generalizes to a superposition of (2^n) basis states, creating an exponentially large state space for representing chemical information. This exponential scaling provides a theoretical foundation for efficiently handling the vast complexity of chemical space, which is estimated to contain approximately (10^{60}) drug-like molecules [23].

In practical chemical applications, superposition enables quantum models to evaluate multiple molecular configurations or reaction pathways simultaneously. For instance, when predicting molecular properties, a quantum feature map can encode numerous structural motifs or electronic configurations in parallel, allowing the model to capture complex structure-property relationships that might be obscured in classical feature representations. This capability is particularly valuable for exploring undruggable protein targets, where conventional methods have failed to identify viable molecular binders [23].

The Entanglement Advantage in Capturing Molecular Correlations

Quantum entanglement creates non-classical correlations between qubits, where the quantum state of each qubit cannot be described independently of the others. This property enables the representation of complex, multi-body interactions that are ubiquitous in chemical systems, such as electron correlations in molecular bonds, non-covalent interactions in protein-ligand complexes, and collective motions in molecular dynamics.

For feature mapping, entanglement creates distributed representations of chemical features that capture intrinsic dependencies within molecular systems. For example, entangled states can simultaneously encode information about a molecule's electronic structure, steric constraints, and pharmacophoric features in a correlated manner that reflects their physical interdependence. This stands in contrast to classical feature representations that often struggle to capture such multi-scale, correlated relationships without explicit engineering.

The enhancement provided by entanglement can be quantified through precision gains in sensing applications. Research has demonstrated that compared to a single qubit in superposition, 100 unentangled qubits would be 10 times more sensitive, while 100 entangled qubits would be 100 times as sensitive [24]. This order-of-magnitude improvement directly translates to enhanced capability in detecting subtle patterns in chemical data, such as minor structural modifications that significantly alter biological activity or molecular properties.

Table 1: Quantitative Advantages of Quantum Feature Mapping

| Quantum Property | Classical Challenge | Quantum Advantage | Impact on Chemical Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superposition | Limited parallel processing for chemical space exploration | Simultaneous evaluation of ~$2^n$ molecular states | Enables comprehensive exploration of ~$10^{60}$ molecule chemical space [23] |

| Entanglement | Difficulty capturing multi-body correlations in molecular systems | Creates non-classical correlations between molecular features | Enhances sensitivity 10x over unentangled systems for 100 qubits [24] |

| Coherent Interference | Manual feature engineering for complex structure-property relationships | Constructive/destructive interference amplifies relevant features | Improves prediction accuracy for experimental chemical properties [25] |

Quantum Feature Mapping in Chemical Applications

Implementation Architectures for Chemical Property Prediction

Multiple quantum computing architectures have been developed to implement feature mapping for chemical property prediction, each with distinct advantages for handling molecular data:

Parametrized Quantum Circuits (PQCs) combine fixed encoding layers with tunable variational layers to transform classical chemical representations into quantum feature spaces. These hybrid quantum-classical models have demonstrated promising results for predicting bond separation energies (BSE49 dataset) and reconstructing coupled-cluster wavefunctions for water conformers [26]. The encoding layers map classical feature vectors (such as molecular fingerprints or quantum chemical descriptors) onto quantum states, while the variational layers with optimized parameters perform the actual feature transformation tailored to specific prediction tasks.

Quantum Convolutional Neural Networks (QCNNs) implement a hierarchical structure inspired by classical CNNs but leverage quantum entanglement for feature detection. Unlike classical convolution that operates on spatial neighborhoods, QCNNs perform convolution through entangling operations between qubits, followed by pooling operations that reduce qubit count while preserving essential features [27]. This architecture is particularly suited for detecting multi-scale patterns in molecular data, such as hierarchical structural motifs that influence compound properties.

Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs) with error mitigation techniques address the critical challenge of noise in NISQ devices. Approaches such as Zero-Noise Knowledge Distillation (ZNKD) use a teacher-student framework where a noise-resistant teacher model (enhanced with zero-noise extrapolation) trains a compact student model for deployment [28]. This methodology has demonstrated robust performance across various datasets while maintaining hardware efficiency, making it particularly valuable for chemical property prediction where training data may be limited.

Application-Specific Feature Mapping Strategies

Different chemical prediction tasks require specialized feature mapping approaches to effectively capture relevant aspects of molecular systems:

For electronic property prediction, quantum feature maps often encode electron correlation patterns directly into entangled states. This approach has shown promise for predicting ground state energies of complex molecules like cytochrome P450 enzymes and FeMoco, with recent resource estimates suggesting that fault-tolerant quantum computers could require as few as 99,000 physical qubits for such simulations [29]. The feature mapping in these applications explicitly represents electron interactions through carefully designed entanglement structures that mirror the correlation patterns in molecular systems.

For molecular generative design, hybrid quantum-classical models combine quantum circuit Born machines (QCBM) with classical long short-term memory (LSTM) networks to explore chemical space for drug discovery. In one implementation targeting the previously undruggable KRAS protein for cancer therapy, the QCBM generates initial molecular fragments that serve as starting points for the classical LSTM model to build upon [23]. The quantum component provides diverse, novel molecular foundations that enhance the exploration capabilities of the overall generative system.

For small dataset learning, quantum circuit learning (QCL) leverages the inherent expressivity of quantum systems to achieve accurate predictions from limited chemical data. Research has demonstrated that QCL can process both linear and smooth non-linear functions from small datasets (<100 records) while outperforming conventional algorithms like random forest, support vector machine, and linear regressions for certain chemical prediction tasks [25]. This capability is particularly valuable in chemical domains where experimental data is scarce or expensive to acquire.

Table 2: Quantum Feature Mapping Methods for Chemical Applications

| Method | Key Mechanism | Chemical Application Examples | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parametrized Quantum Circuits (PQCs) [26] | Combination of encoding and variational layers | Bond separation energy prediction, Wavefunction reconstruction | Comprehensive evaluation of 168 PQC variants on chemical datasets |

| Quantum Circuit Learning (QCL) [25] | Regression via quantum circuit sampling | Toxicity prediction, Experimental property estimation | Superior prediction from small datasets (<100 records) vs. classical models |

| Hybrid Quantum-Classical Generative Models [23] | Quantum circuit Born machine with classical LSTM | Molecular generation for undruggable targets (KRAS protein) | Exploration of vast chemical space (~$10^{60}$ molecules) |

| Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs) with ZNKD [28] | Teacher-student distillation with noise mitigation | Noise-resilient chemical property prediction | Maintains within 2-4% accuracy of teacher model with 6:2-8:3 compression |

Experimental Protocols: Implementing Quantum Feature Mapping

Protocol: Quantum Feature Mapping for Molecular Property Prediction

This protocol details the implementation of a parametrized quantum circuit for predicting experimental chemical properties from molecular structure data, based on established methodologies [25] [26].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Quantum Feature Mapping

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Quantum Feature Mapping |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Programming Frameworks | PennyLane [26], Qiskit [26] | Construct and simulate parametrized quantum circuits |

| Chemical Informatics Tools | RDKit (for MACCS, Morgan fingerprints) [26] | Generate classical molecular representations for encoding |

| Quantum Simulators | State-vector simulators, "Fake" backends [26] | Test circuits in ideal and noisy conditions before hardware deployment |

| Optimization Libraries | Classical optimizers (e.g., Adam, SPSA) | Optimize variational parameters in hybrid quantum-classical models |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Molecular Data Preparation and Feature Engineering

- Select a chemical dataset with associated experimental properties (e.g., toxicity, solubility, energy values)

- Generate molecular representations using classical chemical informatics methods:

- Normalize all feature values to the range [-1, 1] for compatibility with quantum encoding schemes

Quantum Circuit Design and Feature Encoding

- Select an appropriate number of qubits based on feature dimensionality and hardware constraints

- Choose a feature encoding strategy from established approaches:

- Implement the encoding unitary operation (U{\Phi(\mathbf{x})}) that maps classical feature vector (\mathbf{x}) to quantum state (U{\Phi(\mathbf{x})}|0\rangle^{\otimes n})

Variational Circuit Optimization

- Design a variational ansatz (U(\theta)) with parameterized gates following the encoding layer

- Select an entanglement structure that matches the correlation patterns expected in the chemical data:

- Linear entanglement: Sequential entanglement between adjacent qubits

- Full entanglement: All-to-all connectivity for maximum correlation capacity

- Initialize parameters (\theta) randomly or using strategic initialization schemes

Measurement and Objective Definition

- Select a subset of qubits for measurement (typically 1-2 qubits for regression tasks)

- Define the measurement observable (M) (often Pauli-Z operator on target qubits)

- Calculate the expectation value (\langle M \rangle = \langle 0|U^{\dagger}(\theta)U{\Phi(\mathbf{x})}^{\dagger} M U{\Phi(\mathbf{x})}U(\theta)|0\rangle)

- Establish the loss function between predicted and actual chemical properties (typically mean squared error)

Hybrid Optimization Loop

- Execute the quantum circuit to obtain property predictions

- Compute the loss function comparing predictions to experimental values

- Use classical optimization to update variational parameters (\theta)

- Iterate until convergence or predetermined stopping criteria

Protocol: Noise Resilience Enhancement for Quantum Feature Maps

This protocol addresses the critical challenge of noise in NISQ devices by implementing error mitigation strategies specifically tailored for chemical property prediction tasks [24] [27] [28].

Step-by-Step Procedure

Noise Characterization and Modeling

- Profile target quantum hardware or simulator to identify dominant noise channels:

- Phase damping and amplitude damping noise

- Depolarizing noise

- Bit-flip and phase-flip errors

- Quantify error rates for single and two-qubit gates

- Establish baseline performance without error mitigation

- Profile target quantum hardware or simulator to identify dominant noise channels:

Partial Quantum Error Correction Implementation

- Design entanglement-based sensors with inherent noise tolerance

- Apply quantum error correction codes selectively rather than comprehensively

- Balance error correction intensity against sensitivity preservation

- Configure systems to correct only dominant error patterns rather than all possible errors [24]

Zero-Noise Knowledge Distillation (ZNKD)

- Implement teacher-student framework with ZNKD [28]

- Construct teacher model enhanced with zero-noise extrapolation (ZNE)

- Run circuits at scaled noise levels (1x, 3x, 5x base noise through unitary folding)

- Extrapolate to zero-noise limit to generate training labels

- Train compact student model to replicate teacher's noise-free predictions

- Deploy student model for inference without runtime extrapolation overhead

Noise-Aware Circuit Architecture Selection

- Evaluate different quantum neural network architectures for noise robustness:

- Quantum Convolutional Neural Networks (QCNN)

- Quanvolutional Neural Networks (QuanNN)

- Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL)

- Select architecture demonstrating optimal noise resilience for specific chemical prediction task [27]

- Optimize circuit depth to balance expressivity and noise susceptibility

- Evaluate different quantum neural network architectures for noise robustness:

Robustness Validation and Performance Benchmarking

- Test optimized model under simulated noise conditions matching target hardware

- Compare performance against classical baselines and unmitigated quantum models

- Validate on held-out chemical datasets to ensure generalization

- Quantize robustness improvement through metrics like noise-induced accuracy degradation

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

Quantum feature mapping using superposition and entanglement continues to evolve with several promising directions for chemical property prediction. Hardware-efficient feature maps tailored to specific qubit technologies (such as cat qubits [29]) show potential for reducing physical resource requirements while maintaining expressivity. Multi-modal feature encoding strategies that combine different types of molecular representations (structural, electronic, and physicochemical) through specialized quantum circuits may enhance model performance for complex prediction tasks. Federated quantum learning approaches that distribute feature mapping across multiple quantum processors while preserving data privacy represent an emerging paradigm for collaborative drug discovery efforts.

The integration of quantum feature mapping with classical machine learning architectures continues to yield practical benefits even within the constraints of NISQ devices. As quantum hardware advances toward fault tolerance, the unique advantages of superposition and entanglement for chemical feature representation are expected to play an increasingly central role in accelerating drug discovery and materials design.

The pursuit of practical quantum machine learning (QML) for chemical property prediction is currently constrained by a formidable obstacle: quantum noise. In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, quantum processing units are inherently affected by various sources of noise that fundamentally limit their computational utility [30] [31]. These limitations are particularly acute for applications in chemical and drug discovery, where predicting molecular properties with high accuracy could potentially revolutionize materials design and pharmaceutical development [32] [33]. While classical machine learning has demonstrated effectiveness in molecular property prediction, the theoretical promise of QML offers the prospect of exponential speed-ups and enhanced pattern recognition capabilities for navigating complex chemical spaces [34] [33]. However, current quantum hardware suffers from gate errors, decoherence, and imprecise readouts that drastically restrict the circuit depth and qubit count that can be reliably executed [30]. As quantum circuits become deeper to handle complex chemical structures, the cumulative noise often overwhelms the signal, creating a critical barrier that must be understood and addressed before practical applications can be realized.

Quantum noise in NISQ devices manifests through several distinct physical mechanisms, each with characteristic effects on quantum information processing. Understanding these fundamental sources is essential for developing effective mitigation strategies for chemical property prediction.

Primary Quantum Noise Channels

Table 1: Fundamental Noise Channels in NISQ Devices and Their Effects

| Noise Channel | Physical Cause | Effect on Quantum State | Impact on Chemical Prediction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude Damping | Energy dissipation to environment | Loss of excited state population | Incorrect molecular energy calculations | ||

| Phase Damping | Elastic scattering without energy loss | Loss of quantum phase information | Destruction of interference patterns crucial for quantum algorithms | ||

| Depolarizing Noise | Randomizing interactions with environment | Complete mixing of state with maximally mixed state | General loss of quantum features in molecular simulations | ||

| Bit Flip | Classical bit errors in computation basis | Interchange of | 0⟩ and | 1⟩ states | Corruption of encoded molecular descriptor data |

| Phase Flip | Classical phase errors | Introduction of relative phase of -1 | Disruption of coherent superpositions in quantum feature maps |

Hardware Limitations and Coherence Constraints

The practical execution of QML algorithms is constrained by fundamental hardware limitations. Current NISQ devices typically have limited qubit counts (50-100) and suffer from decoherence processes characterized by T1 (energy relaxation time) and T2 (dephasing time) parameters [30] [35]. These limitations drastically restrict the circuit depth that can be reliably executed before quantum information is lost. For chemical property prediction, this translates to an inability to simulate complex molecular systems with sufficient accuracy, as the cumulative noise across deep quantum circuits required for complex chemical transformations often overwhelms the signal of interest [30]. The thermal relaxation channel â„°thermal, which models T1 and T2 processes during gate operations, combines with depolarizing noise â„°depol in comprehensive noise models, where the depolarizing error probability is calibrated to match experimentally characterized gate error rates [35].

Quantitative Analysis of Noise Impact on QML Performance

Rigorous evaluation of noise effects on quantum neural networks reveals significant performance degradation across various architectures and tasks. The following comparative analysis quantifies these impacts specifically for classification tasks relevant to chemical property prediction.

Performance Degradation Across QML Architectures

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Quantum Neural Network Architectures Under Various Noise Conditions

| QML Architecture | Noise-Free Accuracy | Depolarizing Noise (p=0.05) | Amplitude Damping | Phase Damping | Best Noise Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quanvolutional Neural Network | 85.2% | 72.1% | 68.3% | 70.5% | Phase Damping |

| Quantum Convolutional Neural Network | 78.5% | 55.3% | 51.2% | 53.7% | Phase Damping |

| Quantum Transfer Learning | 82.7% | 65.8% | 62.1% | 64.2% | Phase Damping |

| Variational Quantum Circuit | 80.3% | 58.7% | 54.9% | 57.1% | Phase Damping |

Recent comprehensive studies evaluating hybrid quantum-classical neural networks (HQNNs) for image classification tasks provide crucial insights into noise resilience that directly inform chemical prediction applications [27]. The research reveals that Quanvolutional Neural Networks (QuanNN) demonstrate superior robustness across multiple quantum noise channels compared to other architectures, maintaining approximately 72% of their original accuracy under depolarizing noise conditions (p=0.05), while Quantum Convolutional Neural Networks (QCNN) retain only about 70% of their performance [27]. This resilience differential becomes critically important when processing complex molecular descriptors where faithful feature extraction is essential for accurate property prediction.

Resource Overhead and Scalability Challenges

The impact of noise escalates dramatically with increasing circuit complexity and qubit count. Theoretical bounds indicate that the generalization error of a QML model scales approximately as √(T/N), where T is the number of trainable gates and N is the number of training examples [30]. In the presence of noise, the number of samples required for successful optimization may grow super-exponentially, creating fundamental scalability barriers for practical applications in chemical discovery [30]. Error mitigation strategies necessary to counteract these effects typically impose significant resource overhead, with some methods requiring up to 2×10^5 shots to obtain a factor of 10 improvement over unmitigated results [36]. For large-scale chemical space exploration involving thousands of candidate molecules, this overhead becomes prohibitive, particularly when compared to classical graph neural networks that can efficiently handle multi-task molecular property prediction even with limited data [34].

Experimental Protocols for Noise Characterization and Mitigation

Protocol 1: Quantum Noise Modeling via Machine Learning

Accurate noise modeling is a prerequisite for effective mitigation in chemical property prediction pipelines. The following protocol enables data-efficient characterization of device-specific noise parameters:

Initialization: Construct a parameterized noise model ð’©(ðœ½) that incorporates amplitude damping, phase damping, and depolarizing channels with learnable parameters 𜽠[35].

Data Collection: Execute a diverse set of benchmark circuits (4-6 qubits) on the target quantum processor, focusing on circuit structures relevant to chemical feature mapping, such as those encoding molecular descriptors [35].

Classical Optimization: Employ machine learning techniques to optimize parameters ðœ½* by minimizing the Hellinger distance between simulated and experimental output distributions using classical computing resources [35].

Validation: Test the refined noise model on larger validation circuits (7-9 qubits) to verify predictive accuracy for scalable chemical applications [35].

Integration: Incorporate the validated noise model into noise-aware compilers to optimize qubit mapping, gate decomposition, and error mitigation strategies specifically for molecular property prediction circuits.

This approach has demonstrated up to 65% improvement in model fidelity compared to standard noise models derived from basic device properties, enabling more accurate simulation of quantum circuits for chemical prediction tasks [35].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for data-efficient quantum noise modeling using machine learning techniques.

Protocol 2: Noise Resilience Evaluation for Quantum Neural Networks

Systematic evaluation of QML architecture resilience is essential for selecting appropriate models for chemical prediction tasks:

Baseline Establishment: Train target QML architectures (QuanNN, QCNN, QTL) on molecular descriptor datasets under ideal (noise-free) simulation conditions to establish baseline performance metrics [27].

Controlled Noise Injection: Introduce specific quantum noise channels (Phase Flip, Bit Flip, Phase Damping, Amplitude Damping, Depolarization) at progressively increasing probability levels (0.01-0.20) during inference [27].

Performance Monitoring: Track accuracy, fidelity, and convergence metrics across 10 independent runs for each noise condition to ensure statistical significance [27].

Architecture Comparison: Compute relative performance degradation for each architecture and identify optimal models for specific noise environments encountered in target quantum hardware [27].

Hyperparameter Optimization: Fine-tune circuit depth, entanglement patterns, and error mitigation strategies to maximize noise resilience while maintaining expressibility for chemical feature extraction.

This protocol has revealed that QuanNN architectures generally exhibit superior robustness across multiple quantum noise channels, making them promising candidates for noisy chemical prediction applications on current quantum hardware [27].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Noise-Resilient Quantum Chemical Prediction

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Techniques | Function in Noise Resilience | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error Mitigation Frameworks | Clifford Data Regression (CDR), Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | Reduce algorithmic errors without physical qubit overhead | Post-processing of quantum chemical computations |

| Noise Characterization Tools | Process Tomography, Gate Set Tomography, Randomized Benchmarking | Quantify and characterize specific noise channels | Device calibration and noise model parameterization |

| Hybrid Quantum-Classical Algorithms | Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), Quantum Natural Language Processing (QNLP) | Distribute computational load, leverage classical resilience | Molecular energy calculation, Structure-property mapping |

| Quantum Neural Network Architectures | Quanvolutional Neural Networks (QuanNN), Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL) | Intrinsic architectural resistance to specific noise types | Pattern recognition in chemical space, Molecular classification |

| Software Development Kits | Qiskit, TKET, Munich Quantum Toolkit | Noise-aware compilation, Circuit optimization | Algorithm design and implementation |

Emerging Strategies: Turning Noise from Obstacle to Opportunity

Recent research has revealed that quantum noise, while generally detrimental, may be harnessed under specific conditions to enhance learning dynamics. The phenomenon of Noise-Induced Equalization (NIE) demonstrates that modest noise levels can increase the relevance of less influential parameters in quantum neural networks, creating a more uniform optimization landscape that potentially improves generalization capabilities [31]. This effect can be quantified through spectral analysis of the Quantum Fisher Information Matrix (QFIM), where optimal noise levels p* induce the strongest equalization without triggering noise-induced barren plateaus [31]. Similarly, studies on quantum reinforcement learning have demonstrated that carefully tuned amplitude and phase damping noise can sometimes improve algorithm performance rather than purely degrading it [37]. These counterintuitive findings suggest a paradigm shift from unconditional noise suppression to strategic noise management, particularly relevant for chemical property prediction where optimal generalization to novel molecular structures is paramount.

Figure 2: Conceptual relationship between quantum noise levels and model generalization performance, highlighting the optimal zone for noise-enhanced learning.

The critical barrier posed by quantum noise in practical chemical property prediction necessitates a multifaceted approach combining noise-aware algorithms, advanced error mitigation, and strategic hardware utilization. While significant challenges remain in achieving quantum advantage for real-world chemical discovery applications, recent advances in noise characterization, model resilience, and error mitigation provide promising pathways forward. The research community must continue to develop specialized quantum architectures like QuanNN that demonstrate inherent noise resilience, refine resource-efficient error mitigation techniques like enhanced Clifford data regression that reduces shot requirements by an order of magnitude [36], and explore novel paradigms that strategically leverage noise phenomena to enhance learning. For researchers and drug development professionals, the current landscape suggests a pragmatic approach of targeting specific chemical prediction tasks where current NISQ devices offer complementary capabilities rather than outright superiority over classical methods, while steadily building the foundational knowledge and technical capabilities needed for more transformative impacts as quantum hardware continues to evolve.

Building Noise-Aware QML Models for Chemical Property Prediction

The accurate prediction of chemical properties is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and materials science. Traditional computational methods, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT), provide high accuracy but are computationally expensive, hindering large-scale screening efforts [21]. Quantum Machine Learning (QML) emerges as a transformative approach, potentially offering quantum advantages for these complex tasks. A critical factor determining the success of QML models is the strategy used to encode classical molecular data into quantum states [38] [26].

Early QML approaches often relied on classical molecular fingerprints, which compress molecular structures into fixed-length bit vectors. However, these methods can suffer from information loss, high qubit requirements, and poor model trainability on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices [18]. This application note details advanced encoding strategies, focusing on a novel method that directly translates molecular structure into parameterized quantum circuits, enhancing performance for noise-resilient chemical property prediction.

Molecular Data Encoding Schemes

Classical Fingerprints and Their Limitations

Classical molecular fingerprints, such as MACCS keys or Morgan fingerprints, have been widely used as input features for QML models [26]. They function by hashing specific molecular substructures or paths into a bit vector, creating a fixed-dimensional representation.

While simple to generate, these encodings present significant challenges for QML:

- High Resource Demands: Large fingerprints require a substantial number of qubits for direct embedding.

- Circuit Complexity: Preparing these states often necessitates deep quantum circuits, which are prone to errors on NISQ devices.

- Poor Representation: The compression process can lose crucial stereochemical and topological information, hindering the model's ability to distinguish similar molecules [18].

- Trainability Issues: These methods can lead to "barren plateaus" in the optimization landscape, where the cost function gradient vanishes, preventing effective training [18].

Quantum Molecular Structure Encoding (QMSE)

The Quantum Molecular Structure Encoding (QMSE) scheme is a breakthrough designed to overcome these limitations. Instead of using a compressed fingerprint, QMSE directly encodes the molecular graph and its chemical features into a quantum circuit [38] [39].

The core innovation of QMSE is its use of a hybrid Coulomb-adjacency matrix. This matrix integrates:

- Bond Order Information: Representing the strength and type of chemical bonds.

- Interatomic Couplings: Captured through Coulomb interactions, providing a richer physical description than simple connectivity [38] [18].

This matrix is directly mapped onto parameterized quantum circuits as one- and two-qubit rotation gates. This approach is inherently more interpretable, as each quantum gate corresponds to a specific atomic or bonding feature [18]. A key enabling theory behind QMSE is the fidelity-preserving chain-contraction theorem, which allows the algorithm to reuse common molecular substructures (e.g., methylene groups in long-chain fatty acids). This dramatically reduces the qubit count required to represent large molecules while maintaining the accuracy of the quantum state [38].

Performance Comparison of Encoding Schemes

The following table summarizes the performance of QMSE against traditional fingerprint encoding in key chemical tasks, demonstrating its significant advantages.

Table 1: Performance Benchmark of QMSE vs. Fingerprint Encoding

| Task Type | QMSE Performance | Fingerprint Encoding Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Classification | Achieved near 100% accuracy on test datasets [18] | Less than 70% accuracy, even with optimized circuits [18] |

| Regression | Attained an R² > 0.95 (e.g., boiling point prediction) [18] | Lower accuracy with significant information loss [18] |

| Generalization | Better quantum state separation, improving kernel methods [18] | Difficulties in capturing structural similarities [18] |

| Scalability | Enabled by chain contraction for large molecules [38] | Becomes increasingly qubit-intensive [18] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing QMSE for Property Prediction

This protocol details the steps for encoding a molecule using the QMSE scheme to train a Variational Quantum Circuit (VQC) for property prediction.

1. Molecular Input and Preprocessing

- Input: Obtain the molecular structure as a SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) string.

- Canonicalization: Convert the SMILES string into a canonical form using a toolkit like RDKit to ensure a standardized representation [40] [39].

- Conformation Generation: Use a cheap method (e.g., RDKit's ETKDG) to generate an initial 3D molecular conformation. This serves as the geometric input for constructing the hybrid matrix [21].

2. Construct the Hybrid Coulomb-Adjacency Matrix