Operator Pool Performance in Biomedical Research: A Comparative Analysis for Robust and Reproducible Results

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to compare and select operator pools in computational and experimental workflows.

Operator Pool Performance in Biomedical Research: A Comparative Analysis for Robust and Reproducible Results

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to compare and select operator pools in computational and experimental workflows. It addresses the full lifecycle of performance analysis, from foundational definitions and methodological implementation to troubleshooting common pitfalls and rigorous validation. By synthesizing current best practices and validation regimens, this review aims to enhance the robustness, reproducibility, and efficiency of biomedical research reliant on complex operator-driven systems.

Defining Operator Pools: Core Concepts and Performance Metrics for Biomedical Applications

What is an Operator Pool? Foundational Terminology and Classification

The term "Operator Pool" is not a singular, universally defined concept but rather a container term that varies significantly across scientific and engineering disciplines. In the context of performance comparison research, an operator pool generally refers to a collection of resources, components, or entities managed by an operator to achieve system-level objectives such as efficiency, robustness, or predictive accuracy. This guide establishes a foundational terminology and classifies the distinct manifestations of operator pools, focusing on their performance characteristics and the experimental methodologies used for their evaluation.

The core function of an operator pool is to provide a managed set of options from which a system can draw, often involving a selection or fusion mechanism to optimize performance. Research in this domain is critical because the design and management of the pool directly impact the scalability, adaptability, and ultimate success of the system. This guide objectively compares different conceptualizations of operator pools, with a specific focus on their performance in industrial and computational applications.

Foundational Terminology and Classification

Based on their application domain and core function, operator pools can be classified into several distinct categories. The following table outlines the primary types identified in current research.

Table 1: Classification of Operator Pools in Research

| Category | Core Function | Typical Application Context | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Analysis Operator Pool [1] | A group of human operators whose behaviors (movements, postures, task execution) are analyzed and compared across different environments. | Comparing operator performance in real versus immersive virtual reality (VR) manufacturing workstations [1]. | Task completion time, joint angle amplitude, posture scores (RULA/OWAS), error rates, subjective workload (NASA-TLX) [1]. |

| Computational Search Operator Pool [2] | A set of different retrieval algorithms or "paths" (e.g., lexical, semantic) that are combined to improve information retrieval. | Hybrid search architectures in modern database systems and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) [2]. | Retrieval accuracy (nDCG, Recall), query latency, memory consumption, computational cost [2]. |

| Neural Network Pooling Operator Pool [3] | A set of mathematical operations (e.g., max, average) used within a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to reduce spatial dimensions of feature maps. | Feature extraction and dimensionality reduction in image recognition and classification tasks [3]. | Classification accuracy, computational efficiency (speed), model robustness, information loss minimization [3]. |

Performance Comparison of Operator Pools

The performance of an operator pool is highly dependent on its design and the context in which it is deployed. Below, we compare the performance of different pool types and their internal strategies using quantitative data from experimental studies.

Performance of Hybrid Search Operator Pools

Research on hybrid search systems reveals critical trade-offs. A multi-path architecture that combines Full-Text Search (FTS), Sparse Vector Search (SVS), and Dense Vector Search (DVS) can improve accuracy but at a significant cost. Studies identify a "weakest link" phenomenon, where the inclusion of a low-quality retrieval path can substantially degrade the overall performance of the fused system [2]. The choice of fusion method is equally critical; for instance, Tensor-based Re-ranking Fusion (TRF) has been shown to consistently outperform mainstream methods like Reciprocal Rank Fusion (RRF) by offering superior semantic power with lower computational overhead [2].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Retrieval Paradigms in a Hybrid Search Operator Pool [2]

| Retrieval Paradigm | Key Strength | Key Weakness | Impact on System Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-Text Search (FTS) | High efficiency and interpretability; excels at exact keyword matching [2]. | Fails to capture contextual meaning (vocabulary mismatch problem) [2]. | Provides a strong lexical baseline but cannot resolve semantic queries alone. |

| Dense Vector Search (DVS) | Excellent at capturing contextual nuance and meaning using neural models [2]. | Can lack precision for keyword-specific queries [2]. | Dramatically increases memory consumption and query latency [2]. |

| Sparse Vector Search (SVS) | Bridges lexical and semantic approaches [2]. | Performance is intermediate between FTS and DVS [2]. | Useful for balancing the trade-offs between accuracy and system cost. |

Performance of Neural Network Pooling Operators

The choice of pooling operator within a CNN's pool directly influences the model's accuracy and computational efficiency. Standard operators like max pooling and average pooling are computationally efficient but come with well-documented trade-offs: max pooling can discard critical feature information, while average pooling can blur important details [3]. Novel, adaptive pooling operators have been developed to mitigate these issues.

Experimental results on benchmark datasets like CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and MNIST demonstrate that advanced pooling methods can achieve higher classification accuracy. For example, the T-Max-Avg pooling method, which incorporates a learnable threshold parameter to select the K highest interacting pixels, was shown to outperform both standard max pooling and average pooling, as well as the earlier Avg-TopK method [3]. This highlights that a more sophisticated pooling operator can enhance feature extraction and improve model performance without imposing significant additional computational overhead.

Table 3: Classification Accuracy of Different Pooling Operators on Benchmark Datasets [3]

| Pooling Method | Core Principle | Reported Accuracy (CIFAR-10) | Reported Accuracy (CIFAR-100) | Reported Accuracy (MNIST) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max Pooling | Selects the maximum value in each pooling region. | Lower than T-Max-Avg | Lower than T-Max-Avg | Lower than T-Max-Avg |

| Average Pooling | Calculates the average value in each pooling region. | Lower than T-Max-Avg | Lower than T-Max-Avg | Lower than T-Max-Avg |

| Avg-TopK Method | Calculates the average of the K highest values. | Lower than T-Max-Avg | Lower than T-Max-Avg | Lower than T-Max-Avg |

| T-Max-Avg Method | Uses a parameter T to blend max and average of top-K values. | Highest accuracy | Highest accuracy | Highest accuracy |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Comparison

Robust experimental design is the cornerstone of meaningful performance comparison. This section details established methodologies for evaluating different types of operator pools.

Protocol for Comparing Behavioral Operator Pools in VR vs. Real Environments

A rigorous methodology for quantifying differences in operator behavior between immersive (VR) and real manufacturing workstations involves a structured, multi-stage experimental design [1].

1. Objective and Hypothesis Definition: The primary goal is to measure and evaluate the differences in operators' assembly behavior, such as posture, execution time, and movement patterns, between the two environments. A typical hypothesis might be that behavioral fidelity is high, meaning no significant difference exists [1].

2. Participant Selection and Grouping: Researchers select a pool of operators that represent the target user population. To control for learning effects, a common approach is to use a counterbalanced design, where one group performs the task first in the real environment and then in VR, while the other group does the reverse [1].

3. Task Design: Participants perform a standardized manual assembly task that is representative of actual production operations. The task must be complex enough to elicit meaningful behaviors but controlled enough for reliable measurement [1].

4. Data Collection and Parameters Measured: The experiment captures both objective behavioral metrics and subjective feedback.

- Objective Metrics: Motion capture systems are used to record kinematic data (e.g., joint angle amplitudes, trunk inclination). Task completion time and error rates are also logged [1].

- Subjective Metrics: Participants complete standardized questionnaires like the NASA-TLX to assess perceived workload and the System Usability Scale (SUS) to evaluate the VR system itself [1].

5. Data Analysis: The collected data is analyzed to identify statistically significant differences in the measured parameters between the two environments. The analysis also investigates the influence of contextual factors such as task complexity and user familiarity with VR [1].

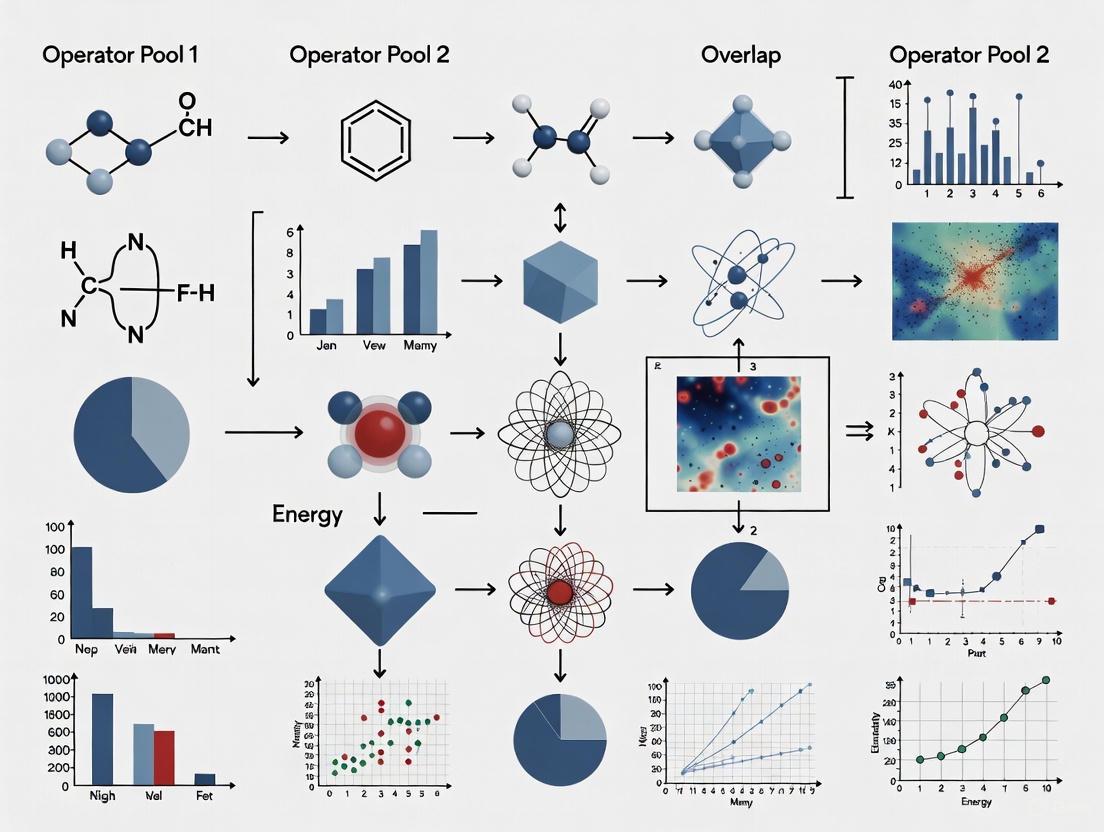

The workflow for this experimental protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol for Evaluating Hybrid Search Operator Pools

The evaluation of hybrid search architectures, which manage a pool of retrieval paradigms, follows a systematic framework to map performance trade-offs [2].

1. Framework Setup: A modular evaluation framework is built that supports the flexible integration of different retrieval paradigms (e.g., FTS, SVS, DVS) [2].

2. Dataset and Query Selection: Experiments are run across multiple real-world datasets to ensure generalizability. A diverse set of test queries is used to evaluate performance [2].

3. Combination and Re-ranking: Different schemes for combining the results from each retrieval path (operator) in the pool are tested. This includes early fusion (e.g., merging result lists) and late fusion (e.g., re-ranking with methods like RRF or TRF) [2].

4. Multi-dimensional Metric Evaluation: System performance is evaluated against a suite of metrics that capture different aspects of quality and cost.

- Accuracy Metrics: nDCG (Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain), Recall [2].

- Efficiency Metrics: Query latency (response time) [2].

- Resource Metrics: Memory consumption and computational cost [2].

The logical relationship and trade-offs in this evaluation are as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details essential materials and tools used in the experimental research concerning behavioral operator pools, as this area requires specific physical and measurement apparatus [1].

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Behavioral Operator Pool Experiments

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Immersive VR Workstation | A high-fidelity virtual reality system used to simulate the real manufacturing environment. It typically includes a head-mounted display, motion tracking, and interaction devices (controllers/gloves) [1]. |

| Real Manufacturing Workstation | The physical, real-world counterpart to the VR simulation. Serves as the baseline for measuring behavioral fidelity and benchmarking VR system performance [1]. |

| Motion Capture System | A camera-based or inertial sensor-based system used to capture high-precision kinematic data of the operator's movements (e.g., joint angles, posture) in both real and virtual environments [1]. |

| NASA-TLX Questionnaire | A validated subjective assessment tool to measure an operator's perceived workload across multiple dimensions, including mental demand, physical demand, and frustration [1]. |

| System Usability Scale (SUS) | A standardized questionnaire for quickly assessing the perceived usability of the VR system from the operator's perspective [1]. |

| Ergonomic Analysis Software | Software that uses motion capture data to compute standardized ergonomic scores (e.g., RULA, REBA, OWAS) to assess the physical strain and injury risk of postures observed during tasks [1]. |

| Carabrolactone B | Carabrolactone B, MF:C15H22O4, MW:266.33 g/mol |

| 7-Xylosyltaxol B | 7-Xylosyltaxol B, MF:C50H61NO18, MW:964.0 g/mol |

The concept of an "Operator Pool" is multifaceted, encompassing human operators in behavioral studies, computational algorithms in search systems, and mathematical functions in neural networks. Performance comparisons consistently show that there is no one-size-fits-all solution; the optimal configuration of an operator pool is dictated by the specific constraints and objectives of the system, be they accuracy, latency, cost, or usability.

Critical to advancing this field is the adoption of rigorous, standardized experimental protocols. Whether comparing behavioral fidelity in VR or benchmarking hybrid search architectures, a methodical approach to design, measurement, and analysis is paramount. Future research will likely focus on developing more adaptive and intelligent operator pools that can self-optimize their selection and fusion strategies in real-time to meet dynamic performance demands.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are quantifiable measures used to monitor, evaluate, and improve performance against strategic goals. Within the context of performance comparison research for operator pools, KPIs provide the essential metrics that enable objective assessment of efficiency, accuracy, and robustness across different operational models or systems. These indicators serve as vital tools for identifying performance gaps, optimizing resource allocation, and driving data-informed decision-making [4]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, a well-defined KPI framework transforms subjective assessments into quantitative, actionable insights that can systematically compare competing methodologies or operational approaches.

The fundamental importance of KPIs lies in their ability to provide strategic alignment between operational activities and broader research objectives, establish objective measurement and accountability for performance claims, and identify specific areas for improvement through comparative analysis [4]. In the high-stakes environment of drug development, where operational efficiency directly impacts both time-to-market and research costs, robust KPI frameworks enable organizations to move from intuition-based decisions to evidence-driven strategies. This is particularly crucial when comparing different operator pools, as standardized metrics allow for direct performance benchmarking and more reliable conclusions about relative strengths and limitations.

Essential KPI Frameworks for Comprehensive Performance Assessment

Core Performance Dimensions and Their Associated Metrics

A comprehensive performance comparison requires evaluating multiple dimensions of operational effectiveness. The most impactful KPIs typically span categories that measure efficiency (how well resources are utilized), accuracy (how correctly the system performs), and robustness (how reliably it performs under varying conditions) [4] [5]. Different operational models may excel in different dimensions, making a multi-faceted assessment crucial for meaningful comparisons.

Table 1: Core KPI Categories for Performance Comparison

| Performance Dimension | Specific KPI Examples | Comparative Application |

|---|---|---|

| Efficiency Metrics | Time-to-insight [4], Query performance [4], Throughput [5], Resource utilization (CPU/Memory) [5] | Measures how quickly and resource-efficiently different operator pools complete tasks under identical workloads. |

| Accuracy Metrics | Model accuracy [4], Data quality score [4], Error rates [5], Right-First-Time Rate [6] | Quantifies output quality and precision across different operational approaches. |

| Robustness Metrics | Uptime [5], Peak response time [5], Concurrent users supported [5], Failure recovery time | Evaluates stability and performance under stress or suboptimal conditions. |

| Business Impact Metrics | Stakeholder satisfaction [4], Return on investment [4] [6], Operational costs [4] | Connects technical performance to organizational outcomes for value comparison. |

Industry-Specific KPI Frameworks: Clinical Trials Example

In drug development research, performance comparison often focuses on clinical trial operations, where selecting high-performing investigator pools significantly impacts trial success and cost. Benchmark data from nearly 100,000 global sites reveals several critical KPIs for this context [7].

Table 2: Clinical Trial Investigator Pool Performance KPIs

| KPI Category | Specific Metric | Performance Benchmark | Comparative Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site Activation Efficiency | Site Activation to First Participant First Visit (FPFV) | Shorter duration correlates with higher enrollment and lower protocol deviation rates [7] | Differentiates pools by startup agility and initial operational competence. |

| Enrollment Performance | Participant enrollment rate, Screen failure rate | Only 17% of sites fail to enroll a patient, but 42% of failing sites screen zero patients [7] | Measures effectiveness at identifying and recruiting eligible participants. |

| Operational Quality | Protocol deviation rate, Discontinuation rate | Quality indicators beyond enrollment provide holistic site assessment [7] | Assesses adherence to protocols and ability to maintain trial integrity. |

| Geographic Variability | Site start-up times by country | Can range from relatively fast (US) to 6+ months (China) [7] | Enables cross-regional operator pool comparisons with appropriate benchmarks. |

Experimental Protocols for KPI-Based Performance Comparison

Deep Learning Approach for Investigator Performance Prediction

Recent research has demonstrated innovative methodologies for comparing and predicting the performance of different clinical investigator pools. The DeepMatch (DM) protocol represents a sophisticated experimental approach that uses deep learning to rank investigators by expected enrollment performance on new clinical trials [8].

Experimental Objective: To develop and validate a model that accurately ranks investigators for new clinical trials based on their predicted enrollment performance, thereby enabling optimized site selection [8].

Data Collection and Integration:

- Investigator performance data: Historical data linking investigators to their clinical study participation, including specialty areas and actual enrollment numbers [8].

- EHR data: Electronic Health Records covering patient diagnoses, procedures, and medications, representing the patient population available to each investigator [8].

- Public study data: Detailed protocol descriptions from clinicaltrials.gov to characterize trial requirements and complexity [8].

Methodology:

- Investigator Representation: Each investigator is encoded as a vector of their most frequent diagnoses, procedures, and medications (50 diagnoses + 50 procedures + 30 prescriptions = 130-dimensional input) [8].

- Study Representation: Each trial is represented by its primary indication, therapeutic area, and free-text description [8].

- Model Architecture: The DeepMatch model employs embedding layers to create distributed representations of medical concepts, followed by fully connected layers with ReLU nonlinearities to learn higher-order interactions [8].

- Matching Layer: A dedicated architecture component matches investigator and trial representations to predict enrollment potential [8].

Performance Comparison Metrics: The model was evaluated on its ability to rank investigators correctly (19% improvement over state-of-the-art) and detect top/bottom performers (10% improvement) [8].

KPI Validation and Benchmarking Methodology

Establishing reliable performance comparisons requires rigorous validation protocols. The AIRE (Appraisal of Indicators through Research and Evaluation) instrument provides a standardized methodology for assessing KPI quality in pharmaceutical and clinical research contexts [9].

Validation Framework:

- Purpose and Relevance: Assessment of whether KPIs align with strategic research objectives and operational realities [9].

- Stakeholder Involvement: Evaluation of how well the KPI framework incorporates input from all relevant parties, including researchers, clinicians, and operational staff [9].

- Scientific Evidence: Critical appraisal of the evidence base supporting each KPI's formulation and interpretation [9].

- Formulation and Usage: Assessment of the clarity of KPI definitions, including detailed numerator/denominator specifications and feasibility of implementation [9].

Experimental Implementation:

- Baseline Establishment: All KPIs require baseline measurements before comparative analysis begins [10].

- Data Analysis Protocol: Regular trending, analysis, and correlation of KPI data to identify meaningful patterns rather than random fluctuations [10].

- Threshold Setting: Defining appropriate performance thresholds based on historical data from nearly 100,000 global sites to contextualize comparison results [7].

- Actionable Insight Generation: Ensuring that KPI comparisons directly inform operational decisions and resource allocation [10].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for KPI Implementation

Implementing a robust KPI framework for performance comparison requires specific methodological tools and data resources. The following table details essential components for experimental execution in this domain.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for KPI Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Data Integration Platforms | Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems, Clinical Trial Management Systems (CTMS) | Aggregates performance data from multiple sources for comprehensive comparison [8] [7]. |

| Analytical Frameworks | Deep learning architectures (e.g., DeepMatch), Statistical process control charts | Enables predictive ranking and identifies statistically significant performance differences [8] [10]. |

| Benchmarking Databases | Historical performance data from 100,000+ global sites, Industry consortium data | Provides context for interpreting comparative results against industry standards [7]. |

| Quality Assessment Tools | AIRE (Appraisal of Indicators through Research and Evaluation) instrument | Systematically evaluates the methodological quality of KPIs used in comparisons [9]. |

| Visualization Systems | Business Intelligence dashboards, Automated reporting platforms | Communplicates comparative findings to stakeholders and supports decision-making [4]. |

| 2,7-Dideacetoxytaxinine J | 2,7-Dideacetoxytaxinine J, CAS:115810-14-5, MF:C35H44O8, MW:592.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| cis-Methylkhellactone | cis-Methylkhellactone, MF:C15H16O5, MW:276.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Comparative Performance Data: Quantitative Results from Experimental Studies

Rigorous performance comparison requires quantitative results from controlled experiments. The following table synthesizes key findings from published studies that directly compare different operational approaches using standardized KPIs.

Table 4: Experimental Performance Comparison Data

| Experimental Context | Compared Approaches | Efficiency KPIs | Accuracy KPIs | Robustness KPIs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Trial Site Selection | DeepMatch (DM) vs. Traditional Methods | 19% improvement in ranking investigators [8] | 10% better detection of top/bottom performers [8] | Maintained performance across diverse trial types and geographies [8] |

| Pharmaceutical Manufacturing | Automated vs. Manual Quality Control | Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE) increased by 22% [6] | Right-First-Time Rate improved to >99.5% [6] | Defect Rate reduced by 35% [6] |

| Data Team Operations | KPI-Driven vs. Ad-Hoc Management | Time-to-insight reduced from 7 days to 48 hours [4] | Data quality score improved from 87% to 96% [4] | Stakeholder satisfaction increased by 30% [4] |

| Clinical Trial Oversight | Proactive vs. Retrospective Monitoring | Site activation to FPFV cycle time reduced by 40% [7] | Protocol deviation rate decreased by 25% [7] | Early identification of 85% of underperforming sites [7] |

The systematic comparison of operator pools through rigorously defined KPIs provides invaluable insights for research optimization and resource allocation. Experimental evidence demonstrates that approaches leveraging advanced computational methods (such as deep learning) and comprehensive data integration consistently outperform traditional selection and evaluation methods across critical performance dimensions [8]. The most successful implementations share common characteristics: they track a balanced set of efficiency, accuracy, and robustness metrics; they establish clear benchmarking data for contextualizing results; and they maintain dynamic KPI frameworks that evolve with changing research priorities [7] [11].

For drug development professionals, these comparative findings highlight the substantial opportunity cost associated with subjective operator pool selection. The documented 19% improvement in investigator ranking and 40% reduction in site activation cycles demonstrate the tangible benefits of data-driven performance comparison [8] [7]. As research environments grow increasingly complex and resource-constrained, the organizations that implement systematic KPI frameworks for performance comparison will gain significant competitive advantages in both operational efficiency and research outcomes.

The Role of Operator Pools in Specific Biomedical Contexts (e.g., High-Throughput Screening, Image Analysis)

In the realm of biomedical research, "operator pools" refer to sophisticated sample multiplexing strategies where multiple biological entities—such as genetic perturbations, antibodies, or chemical compounds—are combined and tested simultaneously within a single experimental unit. This approach stands in stark contrast to traditional one-sample-one-test methodologies, offering unprecedented scalability and efficiency [12] [13]. The fundamental principle underpinning operator pools is the ability to deconvolute collective experimental outcomes to extract individual-level data, thereby dramatically accelerating the pace of scientific discovery. In high-throughput screening (HTS) and image analysis, operator pools have emerged as transformative tools, enabling researchers to interrogate complex biological systems with remarkable speed and resolution [14] [13]. Their application spans critical areas including drug discovery, functional genomics, and systems biology, where they facilitate the systematic mapping of genotype-to-phenotype relationships and the identification of novel therapeutic candidates [15] [13].

This guide provides a performance comparison of different operator pool methodologies, focusing on their implementation in contemporary biomedical research. By examining experimental data and technical specifications, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge needed to select optimal pooling strategies for their specific applications.

Comparative Analysis of Operator Pool Methodologies

Performance Comparison Table

The following table summarizes the key characteristics and performance metrics of three predominant operator pool methodologies:

| Methodology | Screening Format | Theoretical Maximum Plexity | Error Correction | Primary Applications | Implementation Complexity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shifted Transversal Design (STD) [12] | Non-adaptive pooling | Highly flexible; can be tailored to specific experimental parameters | Built-in redundancy allows identification/correction of false positives/negatives | Identification of low-frequency events in binary HTS projects (e.g., protein interactome mapping) | Moderate (requires arithmetic design) | Minimizes pool co-occurrence; maintains constant-sized intersections; compares favorably to earlier designs in efficiency |

| Optical Pooled Profiling [13] | Pooled profiling | Limited by sequencing depth and imaging resolution | Not explicitly discussed; relies on single-cell resolution for deconvolution | Mapping genotype-phenotype relationships with microscopy-based phenotypes (e.g., synapse formation regulators) | High (requires perturbation barcodes, high-content imaging, and computational deconvolution) | Compatible with CRISPR-based perturbations; enables high-dimensional phenotypic capture at single-cell resolution |

| Arrayed Screening [13] | Arrayed | One perturbation per well (e.g., multiwell plate) | Achieved through technical replicates | Flexible, including use of non-DNA perturbants (siRNA, chemicals); bulk or single-cell readouts | Low to Moderate (simpler design but challenging at large scales) | Simple perturbation association by position; susceptible to plate-based biases at large scales; requires significant infrastructure for genome-wide screens |

Experimental Data and Efficiency Metrics

Shifted Transversal Design (STD) demonstrates particular efficiency in scenarios where the target events are rare. The design's flexibility allows it to be tailored to expected positivity rates and error tolerance, requiring significantly fewer tests than individual screening while providing built-in noise correction [12]. For example, in a theoretical screen of 10,000 objects with an expected positive rate of 1%, STD can identify positives with high confidence using only a fraction of the tests that would be required for individual verification, while simultaneously correcting for experimental errors.

Optical Pooled Screening technologies have enabled genome-scale screens with high-content readouts. One study profiling over two million single cells identified 102 candidate regulators of neuroligin-1-mediated synaptogenesis from a targeted screen of 644 synaptic genes [14]. This demonstrates the power of pooled approaches to generate massive datasets from a single experiment. The transition from arrayed to pooled formats for image-based screens is driven by the significant reduction in experimental processing time and the elimination of plate-based batch effects [13].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Visual Opsono-Phagocytosis Assay (vOPA) Using Image-Based Pooled Screening

This protocol details a method for screening monoclonal antibodies for their ability to promote phagocytosis of bacteria by macrophages, leveraging pooled screening and deep learning-based image analysis [15].

- Bacterial Strain Preparation: Engineer Neisseria gonorrhoeae (or other target bacterium) to constitutively express Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) for visualization.

- Antibody Pooling: Combine multiple monoclonal antibody candidates into pools. The pooling strategy (e.g., STD) can be applied to minimize the number of tests required.

- Opsonization and Infection: Incubate the GFP-expressing bacteria with the antibody pools. Use this mixture to infect differentiated THP-1 macrophage cells (dTHP-1) plated in a 96-well microplate. The assay conditions are critical; for N. gonorrhoeae, a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 40 with a 30-minute incubation provided an optimal signal-to-noise ratio of 3.4 [15].

- Staining and Imaging:

- Fix the cells.

- Perform immunostaining with a primary anti-bacterial antibody and a fluorescently-labeled secondary antibody. This step labels only the external (non-engulfed) bacteria, as the antibodies cannot penetrate the cell membrane.

- Counterstain cell nuclei with DAPI and cell membranes with a dye such as CellMask Deep Red.

- Acquire high-content images using a confocal microscope (e.g., Opera Phenix High-Content Screening System).

- Image Analysis with Deep Learning:

- Process the images using a fine-tuned Dense Convolutional Network (DenseNet) pre-trained to classify positive and negative control images.

- Extract feature vectors from the images and use a linear Support Vector Machine (SVM) to compute a "Phagocytic Score" that quantifies the level of antibody-mediated phagocytosis.

- Hit Deconvolution: Identify which specific antibody within a positive pool is responsible for the phagocytosis signal through subsequent validation tests.

Protocol 2: High-Content Single-Cell Optical Pooled Screen for Synapse Formation

This protocol outlines an optical pooled screening approach to identify genetic regulators of synaptogenesis, focusing on cell-cell interactions [14].

- Perturbation Library Design: Design a pooled CRISPR guide RNA (gRNA) library targeting genes of interest (e.g., a synaptic gene library). Each gRNA acts as a unique perturbation barcode.

- Cell Pool Generation:

- Create a stable cell line expressing a synaptic organizer protein (e.g., neuroligin-1) tagged with a fluorescent reporter.

- Lentivirally transduce this cell line at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) with the pooled gRNA library to ensure most cells receive a single perturbation. Also introduce Cas9 (if not stably expressed).

- Culture the transduced cells as a single, mixed population.

- Co-culture and Synapse Induction: Co-culture the perturbed cell pool with a second cell line expressing a corresponding pre-synaptic marker (e.g., GFP-tagged PSD-95).

- Fixation and Staining: Fix the co-culture and perform immunostaining to mark pre-synaptic and post-synaptic components, as well as other relevant cellular structures.

- High-Throughput Imaging and Barcode Sequencing:

- Use an automated microscope to capture high-resolution images of millions of single cells in situ.

- Following imaging, harvest the cells and use next-generation sequencing (NGS) to read out the gRNA barcodes, maintaining the link between each cell's phenotype (image) and genotype (barcode).

- Image Processing and Phenotypic Profiling: Extract high-dimensional morphological features from the images for each cell (e.g., synapse number, size, intensity).

- Data Integration and Analysis: Correlate the extracted image-based phenotypes with the sequenced gRNA barcodes to identify genetic perturbations that significantly alter the synaptogenesis phenotype.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow for the optical pooled screening method:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key reagents and materials essential for implementing operator pool screens, as derived from the featured experimental contexts.

| Item Name | Function/Purpose | Example from Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR gRNA Library | Delivers targeted genetic perturbations to cells in a pooled format; each guide serves as a barcode. | Pooled library targeting 644 synaptic genes [14]. |

| Lentiviral Vector System | Enables efficient, stable delivery of genetic perturbation tools (e.g., gRNAs) into a wide range of cell types. | Used to generate a stable cell pool for optical screening [13]. |

| Fluorescent Reporters/Tags | Allows visualization and quantification of biological processes, protein localization, and cellular structures. | GFP-expressing N. gonorrhoeae; fluorescently tagged neuroligin-1 and PSD-95 [15] [14]. |

| High-Content Imaging System | Automated microscope for acquiring high-resolution, multi-channel images from multi-well plates. | Opera Phenix High-Content Screening System [15]. |

| Differentiated THP-1 Cells | A human monocyte cell line differentiated into macrophage-like cells, used as a model for phagocytosis. | dTHP-1 cells infected with antibody-opsonized bacteria in vOPA [15]. |

| Deep Learning Model (e.g., DenseNet) | Automated, high-dimensional analysis of complex image data to extract quantitative phenotypic scores. | DenseNet fine-tuned to compute a "Phagocytic Score" from microscopy images [15]. |

| Perturbation Barcodes | Unique nucleotide sequences that identify the perturbation in each cell, enabling deconvolution post-assay. | gRNA sequences sequenced via NGS to link phenotype to genotype [13]. |

| Spathulatol | Spathulatol, MF:C30H34O9, MW:538.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Abiesadine N | Abiesadine N, MF:C21H30O3, MW:330.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Systematic Review of Common Operator Pool Architectures and Their Theoretical Strengths

In computational sciences, an "operator pool" describes a function or layer that aggregates information from a local region into a single representative value. This process is fundamental to creating more robust, efficient, and invariant representations within hierarchical processing systems. The architecture of the pooling operator—the specific rules governing this aggregation—profoundly impacts system performance by determining which information is preserved and which is discarded. This systematic review objectively compares common operator pool architectures, focusing on their theoretical strengths, performance characteristics, and applicability in domains such as biomedical data processing and drug development. As deep learning and complex data analysis become integral to modern science, understanding the nuances of these foundational components is critical for researchers and scientists designing new methodologies for tasks like drug-drug interaction (DDI) extraction, genomic analysis, and molecular property prediction [16] [17].

Methodology

Literature Search and Selection

This review synthesizes findings from peer-reviewed scientific literature, conference proceedings, and authoritative textbooks. The selection process prioritized studies that provided quantitative comparisons of different pooling operator architectures, detailed descriptions of experimental methodologies, and applications relevant to bioinformatics and pharmaceutical research. Key search terms included "pooling operations," "operator pooling," "max-pooling," "average pooling," "attention pooling," and "graph pooling," combined with domain-specific terms such as "drug-drug interaction," "genomic," and "neural network."

Scope and Definitions

For this review, "operator pool architecture" is defined as the computational strategy for down-sampling or aggregating feature information from a structured input. The review focuses on three primary contexts:

- Spatial Pooling in Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): Aggregating features across local regions of a feature map [18] [19].

- Graph Pooling in Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Coarsening graph structures by grouping nodes and aggregating their features [20].

- Pooling in Biological Modeling: Simulating cortical aggregation, such as in the primary visual cortex (V1), to understand functional organization [21].

Comparison of Common Operator Pool Architectures

The following section details the operational principles, theoretical strengths, and inherent weaknesses of the most prevalent operator pool architectures.

Max Pooling

- Operational Principle: This function selects the maximum value from the set of inputs within a predefined pooling region [18] [19]. In a 2x2 pooling window, it outputs

max(xâ‚â‚, xâ‚â‚‚, xâ‚‚â‚, xâ‚‚â‚‚). - Theoretical Strengths: Its primary strength is translation invariance; it can detect whether a feature is present in a region, regardless of its precise location [18]. It also preserves the most salient features (e.g., the strongest activated neuron) and is highly effective in practice, often outperforming other methods. For instance, in DDI extraction from biomedical texts, max-pooling achieved a superior F1-score of 64.56% compared to 59.92% for attentive pooling and 58.35% for average-pooling [16]. A key reason for its robustness is its invariance to padding tokens, which are often appended to shorter sentences in NLP tasks, making it particularly suitable for processing biomedical literature with variable sentence structures [16].

- Weaknesses: A significant drawback is its all-or-nothing approach, which discards all non-maximal information. This can lead to the loss of valuable contextual data, especially if multiple elements in the pool have high magnitudes [19].

Average Pooling

- Operational Principle: This function calculates the arithmetic mean of all values within the pooling region [18] [19].

- Theoretical Strengths: It performs smoothing and down-sampling by representing the average activation within a region. This can improve the signal-to-noise ratio by combining information from multiple adjacent data points, making it akin to traditional signal down-sampling techniques [18] [19].

- Weaknesses: Its main weakness is that it can dilute strong features. By averaging over the entire region, a single, highly salient feature may be overwhelmed by many low-activation neighbors, reducing the distinctiveness of the resulting representation [19].

Attentive Pooling

- Operational Principle: This is a more recent, data-driven approach where a learnable attention mechanism assigns a weighted importance to each element in the pool. The output is a weighted sum of the inputs based on these learned scores [16].

- Theoretical Strengths: Its main advantage is adaptive selection. Instead of using a fixed rule like max or average, it learns to emphasize features that are most relevant for the specific task. This can lead to more informative and context-aware representations [16].

- Weaknesses: It introduces additional computational complexity and parameters to the model, increasing the risk of overfitting, particularly with small datasets. In some tasks, such as the DDI extraction study, its performance did not surpass that of the simpler max-pooling, and combining it with max-pooling did not yield further improvements [16].

Geometric Graph Pooling (ORC-Pool)

- Operational Principle: This advanced graph pooling method uses Ollivier's discrete Ricci curvature and an associated geometric flow to coarsen attributed graphs. It groups nodes into "supernodes" by considering both the graph's topology (connections) and the attributes of the nodes [20].

- Theoretical Strengths: It integrates multiple data types by simultaneously considering geometric structure and node feature information. This allows for the identification of meaningful multi-scale structures in complex graphs, such as biological or social networks. It has been shown to match or outperform other state-of-the-art graph pooling methods in tasks like node clustering and graph classification [20].

- Weaknesses: The computation of graph curvature and the associated flow is computationally intensive, which may limit its application to very large-scale graphs without further optimization [20].

Energy Pooling (Biological Models)

- Operational Principle: In computational neuroscience models, this function is used to simulate the behavior of complex cells in the primary visual cortex (V1). It often involves summing the squared responses of simple cell units to achieve phase invariance [21].

- Theoretical Strengths: It is designed to build invariance to phase while retaining selectivity to other stimulus properties, which is a hallmark of biological visual processing. Research suggests that spatial pooling is responsible for the emergence of complex cell-like behavior in neural models [21].

- Weaknesses: Its application is mostly specialized to computational neuroscience models of vision and is less commonly used in general-purpose deep learning architectures for other domains.

Table 1: Qualitative Comparison of Operator Pool Architectures

| Architecture | Primary Mechanism | Key Theoretical Strength | Primary Weakness | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max Pooling | Selects maximum value | Translation invariance, preserves salient features | Discards all non-maximal information | CNNs, DDI extraction [16] [19] |

| Average Pooling | Calculates mean value | Smoothing, noise reduction | Dilutes strong features | CNNs, signal processing [18] [19] |

| Attentive Pooling | Learns weighted sum | Adaptive, task-specific feature selection | Higher computational cost, overfitting risk | CNNs, advanced NLP tasks [16] |

| Geometric (ORC-Pool) | Node grouping via curvature | Integrates topology and node attributes | Computationally intensive | Graph Neural Networks [20] |

| Energy Pooling | Sum of squared responses | Phase invariance in stimulus processing | Domain-specific | Computational neuroscience [21] |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Benchmarking

Experimental Protocol for Comparing Pooling in DDI Extraction

A clear experimental methodology was used to benchmark pooling methods for Drug-Drug Interaction (DDI) extraction, a critical task in pharmacovigilance and drug development [16].

- Dataset: The benchmark DDI corpus was used, containing 1,025 documents (233 Medline abstracts and 792 DrugBank texts) manually annotated with 18,502 drugs and 5,028 DDIs [16].

- Model Architecture: A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) was employed. The input sentences were transformed into a matrix using word embeddings and position embeddings. This was processed by a convolutional layer with multiple filter sizes (e.g., 2, 4, 6) to generate feature maps [16].

- Pooling Layer Variants: The output of the convolutional layer was fed into different pooling layers for comparison: max-pooling, average-pooling, and attentive pooling.

- Evaluation Metric: The primary metric for comparing the performance of the pooled features fed into a classifier was the F1-score, which balances precision and recall.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance in DDI Extraction Experiment

| Pooling Method | Reported F1-Score (%) | Key Experimental Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Max Pooling | 64.56% | Superior performance, attributed to its invariance to padding tokens. |

| Attentive Pooling | 59.92% | Learned weighting was less effective than the fixed max rule in this context. |

| Average Pooling | 58.35% | Smoothing effect likely diluted key features needed for relation extraction. |

The workflow for this experiment is summarized in the diagram below:

Experimental Protocol for Graph Pooling Evaluation

The evaluation of geometric graph pooling (ORC-Pool) involved a different set of standard benchmarks in graph learning [20].

- Datasets: Experiments were conducted on multiple standard graph datasets, which typically include attributed graphs from various domains (e.g., biological molecules, social networks).

- Tasks: The pooling operator was evaluated on two primary tasks:

- Node Clustering: Grouping similar nodes together based on their features and connections.

- Graph Classification: Predicting the label of an entire graph structure.

- Comparison: The performance of ORC-Pool was benchmarked against other state-of-the-art graph pooling methods.

- Evaluation Metrics: For classification tasks, prediction accuracy is a common metric. The computational efficiency and the ability to preserve important structural properties of the graph (e.g., permutation invariance) were also analyzed.

Table 3: Analysis of Operator Pool Performance Across Domains

| Domain | Top Performing Architectures | Key Influencing Factor on Performance |

|---|---|---|

| DDI Text Extraction [16] | Max Pooling | Invariance to syntactic variations and padding. |

| Image Classification [19] | Max Pooling (typically) | Preservation of the most salient local features. |

| Graph Classification [20] | Geometric Pooling (ORC-Pool) | Effective integration of node attributes and graph structure. |

| Genomic SNP Calling [17] | Bayesian (SNAPE-pooled), ML (MAPGD) | Accurate distinction of rare variants from sequencing errors. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key computational tools and data resources essential for research involving operator pools, particularly in bioinformatics and biomedical applications.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Pooling Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to Operator Pool Research |

|---|---|---|

| DDI Corpus [16] | A benchmark dataset of biomedical texts annotated with drug-drug interactions. | Standard resource for training and evaluating models (e.g., CNNs with pooling) for DDI extraction. |

| Pool-seq Data [17] | Genomic sequencing data from pooled individual samples. | Input data for benchmarking SNP callers that use statistical pooling (Bayesian, ML) to estimate allele frequencies. |

| SNP Callers (SNAPE-pooled, MAPGD) [17] | Software for identifying single nucleotide polymorphisms from pooled sequencing data. | Examples of statistical "pooling" operators at the population genomics level. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Libraries | Software frameworks (e.g., PyTorch Geometric, DGL) for building GNNs. | Provide implementations of modern graph pooling layers, including advanced methods like ORC-Pool. |

| Sparse Deep Predictive Coding (SDPC) [21] | A convolutional network model used in computational neuroscience. | Used to study the effect of different pooling strategies (spatial vs. feature) on the emergence of functional and structural properties in V1. |

| Tebufenozide-d9 | Tebufenozide-d9, CAS:1246815-86-0, MF:C22H28N2O2, MW:361.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-Hydroxycanthin-6-one | 1-Hydroxycanthin-6-one|High-Purity Reference Standard |

This review systematically compared the architectures of common operator pools, highlighting that their performance is highly dependent on the specific application domain and data modality. Max-pooling remains a robust and often superior choice for tasks like feature extraction from text and images due to its simplicity, translation invariance, and effectiveness in preserving salient information. In contrast, more complex and adaptive methods like attentive pooling have not consistently demonstrated superior performance, sometimes adding complexity without commensurate gains. For structured data represented as graphs, geometric pooling methods that leverage mathematical concepts like curvature show great promise by effectively integrating topological and feature information.

For researchers in drug development and bioinformatics, the selection of a pooling operator should be guided by the nature of the data and the primary objective of the model. When detecting the presence of specific, high-level features (e.g., a drug interaction phrase, a specific molecular substructure) is key, max-pooling is an excellent starting point. When the goal is to characterize a more global, smoothed property of the data, or to coarsen a graph while preserving its community structure, average or geometric pooling may be more appropriate. Future research will likely focus on developing more efficient and expressive pooling operators, particularly for non-Euclidean data, and on creating standardized benchmarking frameworks to facilitate clearer comparisons across diverse scientific domains.

Implementing and Testing Operator Pools: A Methodological Guide for Experimental Design

Designing Robust Experiments for Operator Pool Comparison

In the field of drug discovery, an "operator pool" refers to the diverse set of methods, algorithms, or computational models available for predicting compound activity during early research and development stages. Comparing the performance of these different operator pools is crucial for identifying the most effective strategies to improve the likelihood of success in clinical development. This guide provides a structured framework for designing robust experiments to objectively compare operator pools, drawing on empirical data and established methodological principles.

The Critical Role of Benchmarking in Drug Development

Benchmarking operator performance against historical data allows pharmaceutical companies to assess the likelihood of a drug candidate succeeding through clinical development stages. This process enables informed decision-making for risk management and resource allocation [22]. Historical analysis of clinical development success rates reveals significant variation in performance across different approaches, with leading pharmaceutical companies demonstrating Likelihood of Approval (LOA) rates ranging broadly from 8% to 23% according to recent empirical analyses [23].

Academic drug discovery initiatives have shown particular promise, with success rates comparable to industry benchmarks: 75% at Phase I, 50% at Phase II, 59% at Phase III, and 88% at the New Drug Application/Biologics License Application (NDA/BLA) stage [24]. These benchmarks provide essential context for evaluating the relative performance of different operator pools in real-world drug discovery applications.

Table 1: Historical Drug Development Success Rates (2006-2022)

| Development Phase | Industry Success Rate | Academic Success Rate | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I to Approval | 14.3% (average) | 19% (LOA from Phase I) | Modality, mechanism of action, disease area |

| Phase I | N/A | 75% | Target selection, compound screening |

| Phase II | N/A | 50% | Efficacy signals, toxicity profiles |

| Phase III | N/A | 59% | Trial design, patient recruitment |

| NDA/BLA | N/A | 88% | Regulatory strategy, data completeness |

Experimental Design Methodology for Operator Comparison

Core Principles of Robust Experimental Design

Designing experiments to compare operator performance requires systematic approaches that capture both quantitative performance metrics and qualitative behavioral characteristics. The fundamental question addressed is how to measure and evaluate differences in operator behavior or performance across different environments or conditions [1]. This necessitates defining specific behavioral characteristics and measurement parameters that enable meaningful comparisons.

Effective experimental design must address several critical challenges:

- Behavioral fidelity: Ensuring operator behavior in experimental conditions accurately reflects real-world performance

- Objective parameter capture: Systematically capturing behavioral parameters beyond subjective feedback

- Contextual variable control: Accounting for external factors that influence performance, including task complexity and user familiarity

- Interaction mechanism differences: Recognizing how different interfaces affect operator performance

Defining Operator Behavior Characteristics

For comparison purposes, operator behavior can be defined as "the ordered list of tasks and activities performed by the operator and the manner to carry them out to accomplish production objectives" [1]. This definition encompasses two crucial dimensions for experimental design:

- Process dimension: The sequence of tasks and activities operators follow

- Execution dimension: The manner in which each task is performed

Experimental designs should incorporate both dimensions to enable comprehensive comparison of operator pool effectiveness.

Protocol for Comparative Operator Pool Experiments

Experimental Setup and Parameter Selection

The experimental procedure involves creating controlled conditions where different operator pools can be evaluated using consistent metrics and benchmarks. For drug discovery applications, this typically involves using carefully curated benchmark datasets that reflect real-world scenarios, such as the Compound Activity benchmark for Real-world Applications (CARA) [25].

Key parameters for evaluation include:

- Performance indicators: Success rates, prediction accuracy, computational efficiency

- Workload assessments: NASA-TLX for subjective workload measurement

- Usability metrics: System Usability Scale (SUS) ratings

- Ergonomic evaluations: Established scores like RULA or REBA where applicable

Test-and-Apply Structure for Operator Selection

A robust methodological approach for operator comparison involves implementing a test-and-apply structure that achieves appropriate balance between exploration of different operators and exploitation of the best-performing ones [26]. This structure divides the evaluation process into continuous segments, each containing:

- Test phase: All operators in the pool are evaluated under controlled conditions with equal resources

- Apply phase: The best-performing operator is selected for the remainder of the segment

This approach ensures fair evaluation of all operators while facilitating selection of optimal performers for specific contexts.

Data Analysis and Visualization Framework

Quantitative Data Analysis Methods

Effective comparison of operator pools requires appropriate quantitative data analysis methods to uncover patterns, test hypotheses, and support decision-making [27]. These methods can be categorized into:

Descriptive Statistics

- Measures of central tendency (mean, median, mode)

- Measures of dispersion (range, variance, standard deviation)

- Percentages and frequencies for distribution patterns

Inferential Statistics

- Hypothesis testing to assess population assumptions

- T-Tests and ANOVA for group differences

- Regression analysis for relationship examination

- Correlation analysis for variable relationships

- Cross-tabulation for categorical variable analysis

Data Presentation Principles

When presenting comparative data for operator pools, tables serve as efficient formats for categorical analysis [28]. Effective table design follows these principles:

- Place compared items in columns and categorical objects in rows

- Include quantitative values at row-column intersections

- Avoid arbitrary ordering in the first column

- Minimize excessive grid lines to enhance readability

- Use conditional formatting to highlight significant differences

Table 2: Operator Performance Comparison Framework

| Evaluation Metric | Operator A | Operator B | Operator C | Benchmark | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success Rate (%) | 75.2 | 68.7 | 81.3 | 71.5 | p < 0.05 |

| False Positive Rate (%) | 12.4 | 18.3 | 9.7 | 14.2 | p < 0.01 |

| Computational Efficiency (ops/sec) | 1,243 | 987 | 1,562 | 1,100 | p < 0.001 |

| Resource Utilization (%) | 78.3 | 85.6 | 72.1 | 80.0 | p < 0.05 |

| Scalability Index | 8.7 | 6.2 | 9.3 | 7.5 | p < 0.01 |

Research Reagent Solutions for Operator Comparison

Implementing robust operator comparison experiments requires specific methodological tools and frameworks. The following table details essential "research reagents" for this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Operator Comparison

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Context | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | Provides standardized data for fair operator comparison | Virtual screening, lead optimization | CARA benchmark, ChEMBL data, FS-Mol |

| Performance Metrics | Quantifies operator effectiveness across dimensions | All comparison studies | Success rates, predictive accuracy, computational efficiency |

| Statistical Frameworks | Determines significance of performance differences | Data analysis phase | Hypothesis testing, ANOVA, regression analysis |

| Experimental Protocols | Standardizes testing procedures across operators | Experimental design | Test-and-apply structure, A/B testing frameworks |

| Visualization Tools | Enables clear presentation of comparative results | Results communication | Data tables, bar charts, performance radars |

Application to Drug Discovery Contexts

Real-World Considerations for Operator Pool Evaluation

When applying operator comparison experiments to drug discovery, several real-world data characteristics must be considered [25]:

- Multiple data sources: Compound activity data often comes from diverse sources with different experimental protocols

- Existence of congeneric compounds: Lead optimization stages involve structurally similar compounds versus diverse screening libraries

- Biased protein exposure: Certain protein targets are overrepresented in existing data

These factors necessitate careful experimental design that accounts for potential biases and ensures generalizable results across different drug discovery contexts.

Dynamic Benchmarking for Enhanced Accuracy

Traditional benchmarking approaches often suffer from limitations including infrequent updates, insufficient data granularity, and overly simplistic success rate calculations [22]. Modern dynamic benchmarking addresses these issues through:

- Real-time data incorporation from new drug development projects

- Expertly curated, rich data extending back decades

- Advanced aggregation methods accounting for non-standard development paths

- Flexible filtering based on modality, mechanism of action, and disease characteristics

- Refined methodologies that consider different development paths without assuming typical progression

Designing robust experiments for operator pool comparison requires systematic methodologies that address both theoretical and practical challenges. By implementing structured experimental designs, appropriate performance metrics, and rigorous statistical analysis frameworks, researchers can generate reliable comparative data to guide selection of optimal operators for specific drug discovery applications. The test-and-apply structure, combined with dynamic benchmarking approaches, provides a comprehensive framework for fair and informative operator evaluation that reflects real-world complexities and constraints.

Selecting and Quantifying Relevant Input Parameters and Environmental Conditions

In the pursuit of sustainable drug development, the early and quantitative assessment of a compound's environmental impact is paramount. The pharmaceutical industry faces increasing pressure to balance therapeutic efficacy with ecological responsibility, particularly as residues of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and their transformation products continue to be detected in various environmental compartments [29]. This comparative analysis examines the experimental frameworks and operator pools—defined here as the collective parameters, models, and assessment methodologies used to predict environmental fate—within the context of environmental risk assessment (ERA) for pharmaceuticals.

The concept of "operator pools" in this context refers to the integrated set of tools, models, and assessment criteria that researchers employ to quantify and predict the environmental behavior of pharmaceutical compounds. Different regulatory frameworks and research institutions utilize distinct operator pools, each with unique strengths and limitations in predicting environmental outcomes. This guide objectively compares these methodological approaches, providing researchers with a structured analysis of their performance characteristics based on current scientific literature and regulatory practices.

Experimental Protocols for Environmental Risk Assessment

Standardized ERA Protocols for Veterinary Medicinal Products

The environmental risk assessment for veterinary medicinal products (VMPs) follows a tiered approach as outlined in VICH guidelines 6 and 38, adopted by the European Medicines Agency [29]. This protocol provides a standardized methodology for quantifying environmental parameters.

Phase I - Initial Exposure Assessment: The protocol begins with a comprehensive evaluation of the product's environmental exposure potential. Researchers must collect data on physiochemical characteristics, usage patterns, dosing regimens, and excretion pathways. Key quantitative parameters include predicted environmental concentrations (PECs) in soil and water compartments. Products with PECsoil values below 100 μg/kg typically conclude the assessment at this phase, while those exceeding thresholds proceed to Phase II [29].

Phase II - Tiered Ecotoxicity Testing: This phase employs a hierarchical testing strategy:

- Tier A: Laboratory-based ecotoxicity testing using model organisms to determine the predicted no-effect concentration (PNEC). Standard test organisms include Daphnia magna (water flea), Aliivibrio fischeri (bacteria for luminescence inhibition tests), and Lemna minor (aquatic plant).

- Tier B: Refined assessment using more complex fate and effect studies when PEC/PNEC ratios exceed 1. This includes investigating environmental fate processes such as hydrolysis, photolysis, and biodegradation.

- Tier C: Field studies or implementation of risk mitigation measures for compounds identified as high-risk in previous tiers [29].

Novel Assessment Methodologies

Emerging protocols incorporate New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) that utilize non-animal testing and predictive tools during early drug development stages. These methodologies include:

- In vitro bioassays targeting specific molecular pathways conserved across species

- In silico prediction models using quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR)

- High-throughput screening approaches for rapid assessment of multiple environmental endpoints [29]

A recent interview study with pharmaceutical industry representatives highlighted the development of protocols that "incorporate environmental fate assessment into early phases of drug design and development" to create "pharmaceuticals intrinsically less harmful for the environment" [30].

Comparative Analysis of Operator Pool Methodologies

Quantitative Comparison of ERA Approaches

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Environmental Assessment Operator Pools

| Assessment Method | Key Input Parameters | Environmental Compartments Assessed | Testing Duration | Regulatory Acceptance | Cost Index (Relative) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VICH Tiered ERA | PEC, PNEC, biodegradation half-life, bioaccumulation factor | Soil, water, sediment | 6-24 months | Full (EU, US) | High (100) |

| NAMs (Early Screening) | Molecular weight, logP, chemical structure, target conservation | Aquatic ecosystems | 2-4 weeks | Limited | Low (20) |

| Life Cycle Assessment | Manufacturing energy use, waste generation, transportation emissions | Air, water, soil (broad environmental impact) | 3-12 months | Growing | Medium-High (70) |

| Legacy Drug Assessment | Consumption data, chemical stability, detected environmental concentrations | Water systems (primary) | Variable | Retrospective | Medium (50) |

Analysis of Operator Pool Performance

The comparative data reveals significant trade-offs between regulatory acceptance, comprehensiveness, and resource requirements across different operator pools. The standardized VICH protocol offers regulatory acceptance but requires substantial time and financial investment [29]. New Approach Methodologies provide rapid screening capabilities at early development stages but currently lack broad regulatory acceptance [29] [30].

Life Cycle Assessment methodologies expand the evaluation beyond ecological impact to include broader sustainability metrics but require extensive data collection across the entire pharmaceutical supply chain [30]. For legacy drugs approved before 2006 implementation of comprehensive ERA requirements, assessment protocols primarily rely on post-market environmental monitoring and consumption-based exposure modeling [29].

Research Reagent Solutions for Environmental Testing

Essential Materials for Ecotoxicity Assessment

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Environmental Risk Assessment

| Reagent/Test System | Function in Assessment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Daphnia magna | Freshwater crustacean used for acute and chronic toxicity testing | Standardized aquatic ecotoxicity testing (OECD 202) |

| Aliivibrio fischeri | Marine bacteria for luminescence inhibition assays | Rapid toxicity screening (ISO 11348) |

| Lemna minor | Aquatic plant for growth inhibition studies | Assessment of phytotoxicity in freshwater systems |

| Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata | Green algae for growth inhibition tests | Evaluation of effects on primary producers |

| QSAR Software Tools | In silico prediction of environmental fate parameters | Early screening of compound libraries |

| Soil Microcosms | Complex microbial communities for degradation studies | Assessment of biodegradation in terrestrial environments |

| HPLC-MS/MS Systems | Quantification of API concentrations in environmental matrices | Analytical verification in fate studies |

Visualization of Assessment Workflows

Tiered Environmental Risk Assessment Pathway

Tiered ERA Workflow

Early-Stage Environmental Assessment Integration

Early-Stage Screening Process

Discussion

The comparative analysis of operator pools for environmental assessment reveals a evolving methodology landscape. Traditional standardized approaches like the VICH protocol provide regulatory certainty but may benefit from integration with emerging methodologies that offer earlier intervention points in the drug development pipeline [29] [30].

A significant challenge across all operator pools remains the assessment of compounds that target evolutionarily conserved pathways. As noted in recent research, "the higher the degree of interspecies conservation, the higher the risk of eliciting unintended pharmacological effects in nontarget organisms" [29]. This underscores the need for operator pools that can accurately predict cross-species reactivity, particularly for antiparasitic drugs where target proteins like β-tubulin are highly conserved among eukaryotes [29].

The pharmaceutical industry has demonstrated growing commitment to environmental considerations, with company representatives in interview studies highlighting ongoing efforts to "reduce waste and emissions arising from their own operations" [30]. However, significant challenges remain in addressing "environmental impacts arising from drug consumption" and managing "centralized drug manufacturing in countries with lax environmental regulation" [30].

Future development of operator pools will likely focus on enhancing predictive capabilities through improved computational models, expanding the scope of assessment to include transformation products, and developing standardized methodologies for evaluating complex environmental interactions. The integration of environmental criteria early in the drug development process represents the most promising approach for achieving truly sustainable pharmaceuticals while maintaining therapeutic efficacy.

In drug discovery, high-throughput screening (HTS) serves as a critical methodology for evaluating vast chemical libraries to identify potential therapeutic compounds. The fundamental challenge lies in accurately detecting active molecules amidst predominantly inactive substances while managing substantial experimental constraints. Pooling strategies present a sophisticated solution to this challenge by testing mixtures of compounds rather than individual entities, thereby optimizing resource utilization and enhancing screening efficiency [31]. These methodologies are particularly valuable in modern drug development where libraries often contain millions to billions of compounds, making individual testing prohibitively expensive and time-consuming.

The core rationale behind pooling rests on statistical principles: since most compound libraries contain only a small fraction of active compounds, testing mixtures can rapidly eliminate large numbers of inactive compounds through negative results. This approach simultaneously addresses the persistent issue of experimental error rates in HTS by incorporating internal replicate measurements that help identify both false positives and false negatives [31] [32]. As the field progresses toward increasingly large screening libraries, the implementation of robust, well-designed pooling protocols becomes essential for maintaining both consistency in data collection and reduction of systematic bias in hit identification.

Comparative Analysis of Pooling Methodologies

Fundamental Pooling Design Frameworks

Pooling designs can be broadly categorized into adaptive and nonadaptive strategies, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Adaptive pooling employs a multi-stage approach where information from initial tests informs subsequent pooling designs, while nonadaptive pooling conducts all tests in a single stage with compounds appearing in multiple overlapping pools [31]. A third category, orthogonal pooling or self-deconvoluting matrix strategy, represents an intermediate approach where each compound is tested twice in different combinations [31].

The Shifted Transversal Design (STD) algorithm represents a more advanced nonadaptive approach that minimizes the number of times any two compounds appear together while maintaining roughly equal pool sizes. This methodology, implemented in tools like poolHiTS, specifically addresses key constraints in drug screening, including limits on compounds per assay and the need for error-correction capabilities [32]. The mathematical foundation of STD ensures that the pooling design can correctly identify up to a specified number of active compounds even in the presence of predetermined experimental error rates.

Performance Comparison of Pooling Strategies

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Pooling Strategies in High-Throughput Screening

| Pooling Method | Key Principle | Tests Required | Error Resilience | Implementation Complexity | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One Compound, One Well | Each compound tested individually in separate wells | n (library size) | Low - no error correction | Simple | Small libraries, high hit-rate screens |

| Adaptive Pooling | Sequential testing with iterative refinement based on previous results | d logâ‚‚ n (where d = actives) | Moderate - vulnerable to early-stage errors | Moderate | Libraries with very low hit rates |

| Orthogonal Pooling | Each compound tested twice in different combinations | 2√n | Low - no error correction, false positives occur | Moderate | Moderate-sized libraries with predictable hit distribution |

| STD-Based Pooling (poolHiTS) | Nonadaptive design minimizing compound co-occurrence | Varies by parameters (n, d, E) | High - designed to correct E errors | High | Large libraries requiring robust error correction |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Advanced Screening Platforms

| Screening Platform/Method | Docking Power (RMSD ≤ 2Å) | Screening Power (EF1%) | Target Flexibility | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RosettaVS | 91.2% | 16.72 | High - models sidechain and limited backbone flexibility | Moderate (accelerated with active learning) |

| Traditional Physics-Based Docking | 75-85% | 8-12 | Limited - often rigid receptor | Low to moderate |

| Deep Learning Methods | 70-80% | Varies widely | Limited generalizability to unseen complexes | High once trained |

Recent advances in virtual screening have demonstrated significant improvements in performance metrics. The RosettaVS platform, which incorporates an improved forcefield (RosettaGenFF-VS) and allows for substantial receptor flexibility, has shown state-of-the-art performance on standard benchmarks [33]. On the CASF-2016 benchmark, RosettaVS achieved a top 1% enrichment factor of 16.72, significantly outperforming other methods, and demonstrated superior performance in accurately distinguishing native binding poses from decoy structures [33].

Experimental Protocols for Pooling Strategies

poolHiTS STD-Based Pooling Protocol

The poolHiTS protocol implements a practical version of the STD algorithm specifically optimized for drug screening constraints. The experimental workflow begins with parameter specification: compound library size (n), maximum expected active compounds (d), and maximum expected errors (E) [32]. The protocol proceeds through the following methodological stages:

Algorithm 1: STD Pooling Design

- Parameter Selection: Choose a prime number q (starting with 2) where q < n

- Compression Power Calculation: Find Γ = min{γ|q^(γ+1) ≥ n}, then set k = dΓ + 2E + 1

- Guarantee Verification: Check if k ≤ q + 1; if not, choose next prime and repeat

- Optimization: Cycle through values of Γ to find optimal q satisfying q ≥ n^(1/Γ+1)

- Test Calculation: Determine number of tests needed from t = q × k

- Matrix Construction: Design the pooling matrix M = STD(n; q; k)

The decoding algorithm for results follows a logical sequence: first, compounds present in at least E+1 negative tests are tagged inactive; second, compounds present in at least E+1 positive tests where all other compounds are inactive are tagged active [32]. This structured approach guarantees correct identification of active compounds within the specified error tolerance.