Optimizing ADAPT-VQE: Strategies for Balancing Measurement Costs and Circuit Depth in Quantum Chemistry Simulations

This article explores the critical trade-off between measurement overhead and circuit depth in the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE), a leading algorithm for molecular simulations on near-term quantum...

Optimizing ADAPT-VQE: Strategies for Balancing Measurement Costs and Circuit Depth in Quantum Chemistry Simulations

Abstract

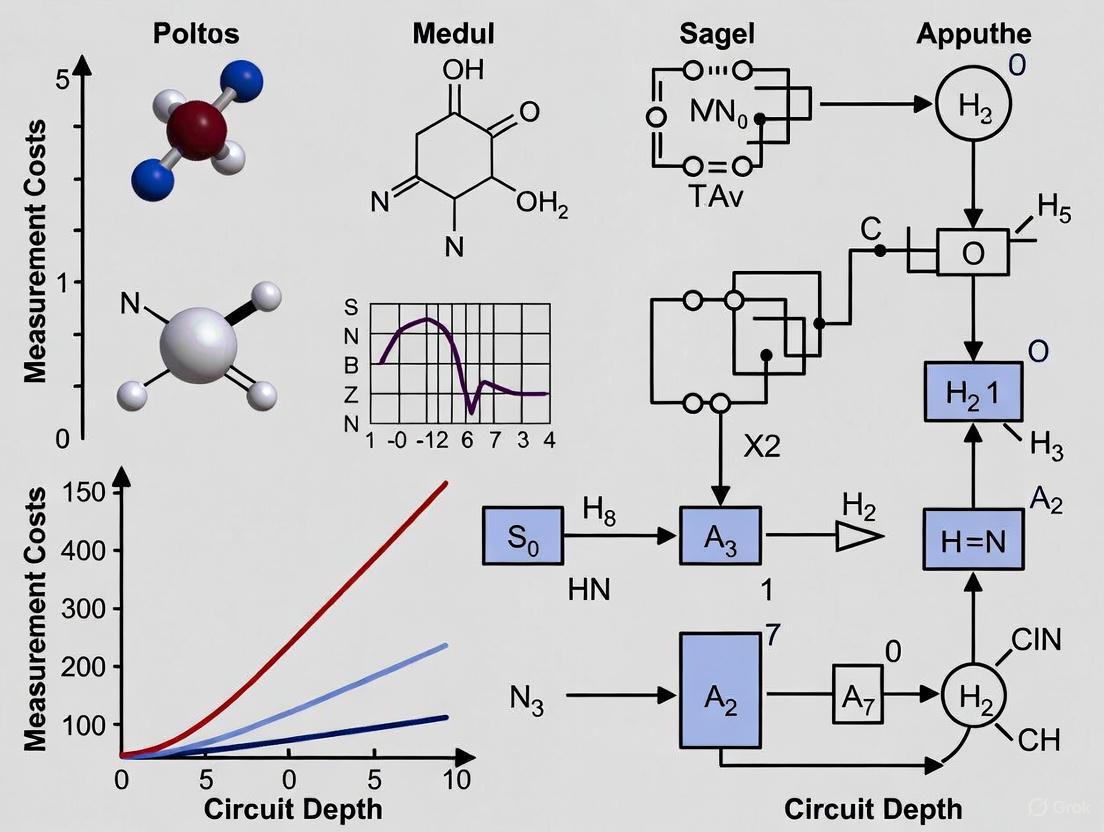

This article explores the critical trade-off between measurement overhead and circuit depth in the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE), a leading algorithm for molecular simulations on near-term quantum hardware. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, we examine foundational principles, advanced methodological improvements like the Coupled Exchange Operator pool and shot-reduction techniques, and optimization strategies that achieve up to 99.6% reduction in measurement costs and 96% reduction in CNOT depth. Through validation against established methods like UCCSD, we demonstrate how these optimizations enhance the feasibility of quantum-accelerated drug discovery by making accurate molecular simulations more practical on current noisy intermediate-scale quantum devices.

Understanding ADAPT-VQE: Foundations of Adaptive Ansätze and the Resource Trade-off

The pursuit of quantum advantage in computational chemistry has catalyzed the development of hybrid quantum-classical algorithms designed for noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. Among these, the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading approach for molecular simulations, leveraging the variational principle to find ground state energies through parameterized quantum circuits [1]. However, the performance of VQE critically depends on the choice of wavefunction ansatz, with traditional fixed ansätze like Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) often resulting in prohibitively deep circuits or insufficient accuracy for strongly correlated systems [1] [2]. This limitation prompted the development of adaptive approaches that systematically construct problem-tailored ansätze.

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a paradigm shift from fixed ansätze to adaptive construction, generating system-specific circuits with minimal resource requirements [1]. By growing the ansatz iteratively through the selective addition of operators from a predefined pool, ADAPT-VQE achieves remarkable efficiency in circuit depth and parameter count. This guide comprehensively compares ADAPT-VQE variants against traditional approaches, analyzing the critical trade-off between measurement overhead and circuit complexity that defines current research frontiers in quantum computational chemistry.

Algorithmic Fundamentals: How ADAPT-VQE Works

Core Mechanism and Adaptive Workflow

ADAPT-VQE operates through an iterative process that constructs ansätze tailored to specific molecular systems. Unlike fixed-structure approaches, it begins with a simple reference state (typically Hartree-Fock) and systematically grows the ansatz by adding parameterized unitary operators from a predefined pool [1] [3]. The algorithm's selection criterion is based on energy gradient calculations: at each iteration, it identifies the operator from the pool that demonstrates the largest magnitude gradient with respect to the energy, then appends this operator to the circuit and optimizes all parameters [3] [4]. This process continues until the gradients of all remaining pool operators fall below a predetermined threshold, indicating convergence to the ground state.

The following diagram illustrates the iterative workflow of the ADAPT-VQE algorithm:

Mathematical Foundation

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm is grounded in the variational principle of quantum mechanics, which establishes that for any normalized trial wavefunction |Ψ〉, the expectation value of the Hamiltonian Ĥ satisfies E ≤ ⟨Ψ|Ĥ|Ψ⟩, with equality only when |Ψ⟩ is the true ground state [5]. The molecular electronic Hamiltonian in second quantization is expressed as:

Ĥ = ∑{p,q} h{pq} ap^†aq + 1/2 ∑{p,q,r,s} h{pqrs} ap^†aq^†as ar

ADAPT-VQE prepares parameterized wavefunctions through unitary operations applied to a reference state |ψref⟩: |Ψ(θ)⟩ = U(θ)|ψref⟩. The unitary operator is constructed iteratively as a product of exponentials of anti-Hermitian operators selected from a pool: U(θ) = âˆk exp[θk (Tk - Tk^†)], where Tk represents excitation operators [5] [1]. The critical selection criterion involves identifying the operator that maximizes the energy gradient magnitude: |∂/∂θ ⟨Ψ|Uk(θ)^†Ĥ Uk(θ)|Ψ⟩| at θ=0, which can be shown to equal |⟨Ψ|[Ĥ, Ï„k]|Ψ⟩|, where Ï„k = Tk - T_k^†[3].

Comparative Analysis: ADAPT-VQE Variants and Traditional Approaches

Performance Metrics Across Molecular Systems

The evolution of ADAPT-VQE has spawned multiple variants optimized for different resource constraints. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for prominent ADAPT-VQE implementations compared to traditional fixed ansätze like UCCSD:

Table 1: Resource Requirements for Quantum Chemistry Simulations

| Algorithm | Molecule (Qubits) | CNOT Count | CNOT Depth | Measurement Costs | Accuracy (Relative to FCI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* [2] | LiH (12) | 427 | 110 | 1.5×10^4 | Chemical accuracy |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* [2] | H6 (12) | 1,102 | 348 | 2.7×10^4 | Chemical accuracy |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* [2] | BeH2 (14) | 1,366 | 302 | 4.3×10^4 | Chemical accuracy |

| GSD-ADAPT-VQE [2] | LiH (12) | 1,698 | 1,374 | 3.8×10^6 | Chemical accuracy |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE [6] | H4 (8) | ~200 | ~50 | - | >99.9% correlation energy |

| UCCSD [1] | H6 (12) | >10,000 | >5,000 | ~10^9 | Varies with correlation |

| Shot-Efficient ADAPT [7] | H2 (4) | - | - | 43.21% reduction | Maintains fidelity |

Operator Pools: The Architectural Foundation

The performance characteristics of different ADAPT-VQE variants are largely determined by their operator pools:

- Fermionic Pool: The original ADAPT-VQE implementation used generalized single and double (GSD) excitations, maintaining a direct connection to quantum chemistry methods but producing relatively deep circuits [2].

- Qubit Pool: This hardware-efficient approach uses Pauli string operators, dramatically reducing circuit depth through measurement of qubit-wise commuting groups and improved hardware compatibility [6].

- Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) Pool: A novel approach that combines the resource efficiency of qubit pools with the chemical intuition of fermionic operators, significantly reducing CNOT counts and measurement requirements while maintaining accuracy [2].

Table 2: Operator Pool Characteristics and Applications

| Pool Type | Circuit Efficiency | Measurement Overhead | Strong Correlation Handling | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fermionic (GSD) | Low | High | Excellent | Low |

| Qubit | High | Medium | Good | Medium |

| CEO | High | Low | Excellent | High |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard ADAPT-VQE Implementation

Implementing ADAPT-VQE requires careful attention to several experimental components. The standard protocol involves:

System Preparation: Molecular geometry is defined, followed by generation of the electronic Hamiltonian in the second quantized form using a chosen basis set (e.g., STO-3G). The Hamiltonian is then mapped to qubit operators via Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation [8] [4].

Operator Pool Generation: For fermionic ADAPT-VQE, the pool typically contains all unique spin-adapted single and double excitations. In a LiH simulation with 4 qubits and 2 active electrons, this results in approximately 24 excitation operators [4]. The pool size scales combinatorially with system size, though this can be mitigated through symmetry considerations.

Iterative Execution: The algorithm proceeds through gradient calculation, operator selection, circuit growth, and parameter optimization cycles. Gradients are computed as |⟨Ψ|[Ĥ, τ_k]|Ψ⟩| for all pool operators. The selected operator is appended to the ansatz with an initial parameter of zero, followed by optimization of all parameters using classical minimizers like L-BFGS-B or BFGS [8].

Convergence Criteria: The algorithm terminates when the largest gradient magnitude falls below a predetermined threshold (typically 10^-3 to 10^-2), indicating that additional operators cannot significantly lower the energy [8].

Measurement Optimization Techniques

Recent research has focused extensively on reducing the measurement overhead in ADAPT-VQE:

Reused Pauli Measurements: This technique leverages the observation that Pauli measurement outcomes from VQE parameter optimization can be reused in subsequent operator selection steps, reducing the required shots by approximately 68% on average [7].

Variance-Based Shot Allocation: By allocating measurement shots proportionally to the variance of Hamiltonian terms and commutators, this approach reduces shot requirements by 43.21% for H2 and 51.23% for LiH compared to uniform allocation [7].

Commutativity-Based Grouping: Grouping Hamiltonian terms and gradient commutators by qubit-wise commutativity minimizes the number of distinct circuit executions required for measurements [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Components

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for ADAPT-VQE Implementation

| Tool Name | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| PennyLane [4] | Quantum machine learning library | Adaptive circuit construction and optimization |

| InQuanto [8] | Quantum chemistry platform | Fermionic ADAPT-VQE implementation |

| Qulacs [8] | Quantum circuit simulator | Statevector simulation for algorithm validation |

| SciPy Minimizers [8] | Classical optimization routines | L-BFGS-B for parameter optimization |

| OpenFermion | Electronic structure package | Hamiltonian and operator pool generation |

| 9-O-Feruloyllariciresinol | 9-O-Feruloyllariciresinol, MF:C30H32O9, MW:536.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-Docosanoyl Taurine | N-Docosanoyl Taurine, MF:C24H49NO4S, MW:447.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Considerations for Different Molecular Systems

The performance of ADAPT-VQE varies significantly across molecular systems, requiring tailored approaches:

Strongly Correlated Systems: For molecules with significant strong correlation effects (e.g., bond dissociation regions), fermionic and CEO pools outperform qubit pools in accuracy but require more resources [2].

System Size Scaling: As molecular size increases, measurement costs become the dominant resource constraint. For systems beyond 12 qubits, shot-efficient variants become essential [7] [2].

Hardware Constraints: On current NISQ devices with limited coherence times, qubit-ADAPT-VQE offers practical advantages despite potential accuracy trade-offs, with demonstrations on up to 25-qubit systems [3] [6].

The evolution from fixed ansätze to adaptive construction represents significant progress in quantum computational chemistry. ADAPT-VQE and its variants demonstrate substantial improvements over traditional approaches like UCCSD, reducing circuit depths by up to 96% and measurement costs by up to 99.6% while maintaining chemical accuracy [2]. The fundamental trade-off between measurement overhead and circuit complexity continues to drive research, with recent innovations like CEO pools and shot-reduction techniques progressively optimizing both dimensions.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the selection of specific ADAPT-VQE implementations should be guided by target molecular properties and available quantum resources. Fermionic variants remain valuable for strongly correlated systems where accuracy is paramount, while qubit-based approaches offer practical advantages on current hardware. CEO-ADAPT-VQE* represents the current state-of-the-art, balancing empirical performance with theoretical guarantees. As measurement techniques continue to improve and hardware capabilities expand, adaptive algorithms are poised to enable quantum simulations of increasingly complex molecular systems relevant to pharmaceutical development and materials design.

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) has emerged as a gold standard among hybrid quantum-classical algorithms for molecular simulation, promising significantly reduced quantum circuit depths compared to traditional approaches like unitary coupled cluster (UCCSD). This circuit depth reduction is critically important for implementation on current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, where excessive gate counts render calculations impossible due to decoherence. However, this advantage comes at a substantial cost: a dramatically increased quantum measurement (shot) overhead required for the algorithm's iterative operator selection process. This creates a fundamental tension—while ADAPT-VQE produces shallower circuits that are more likely to run on existing hardware, the measurement resources needed to identify these efficient circuits may themselves become prohibitive [9] [10]. This article provides a comparative analysis of recently developed strategies that aim to resolve this tension by minimizing ADAPT-VQE's measurement overhead without sacrificing the compactness of the final ansatz.

Comparative Analysis of Measurement-Efficient ADAPT-VQE Strategies

The following table summarizes the core methodologies and experimental findings of key approaches discussed in this review.

Table 1: Comparison of Measurement Overhead Reduction Strategies for ADAPT-VQE

| Strategy | Core Methodology | Test Systems | Reported Measurement Reduction | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shot-Optimized ADAPT-VQE [7] | Reuses Pauli measurements from VQE optimization in subsequent gradient steps; applies variance-based shot allocation. | Hâ‚‚ to BeHâ‚‚ (4-14 qubits), Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„ (16 qubits) | Up to ~68% reduction vs. naive measurement (with grouping + reuse) | Retains computational basis measurements; low classical overhead. |

| AIM-ADAPT-VQE [9] | Uses Adaptive Informationally Complete Generalized Measurements (AIMs); reuses IC-POVM data for gradient estimation. | Hâ‚„, Hâ‚‚O, C₈Hâ‚â‚€ | Near 100% reuse of energy measurement data for gradients | Eliminates dedicated quantum measurements for gradient evaluations. |

| Batched ADAPT-VQE [11] | Adds multiple operators with largest gradients to the ansatz simultaneously in each iteration. | Oâ‚‚, CO, COâ‚‚ (carbon monoxide oxidation reaction) | Significant reduction in number of gradient computation cycles | Directly reduces the number of iterative steps and associated measurements. |

| Overlap-ADAPT-VQE [10] | Grows ansatz by maximizing overlap with an accurate target state (e.g., from classical computation), then refines with ADAPT-VQE. | Stretched BeH₂, linear H₆ chain | Produces ultra-compact ansätze, indirectly reducing measurements needed for optimization. | Avoids local energy minima, leading to shorter circuits and fewer parameters. |

| Complete & Symmetry-Adapted Pools [12] | Uses minimal "complete" operator pools of size 2n-2 (for n qubits), chosen to respect system symmetries. | Strongly correlated molecules | Reduces operator pool screening cost from O(nâ´) to O(n) | Minimal pool size directly cuts gradient measurement overhead. |

The findings from these studies demonstrate that the measurement overhead is not an immutable feature of ADAPT-VQE but can be aggressively mitigated through strategic innovations. The optimal choice of strategy depends on the specific constraints of a calculation. For instance, AIM-ADAPT-VQE is remarkably effective for smaller systems where its generalized measurements are feasible, virtually eliminating the overhead for gradient evaluations [9]. For larger simulations, the integrated approach of Shot-Optimized ADAPT-VQE, which combines data reuse with smart shot allocation, provides a robust and hardware-friendly path to efficiency [7]. Furthermore, fundamental improvements like using complete pools address the problem at its root by minimizing the number of operators that need to be evaluated in each iteration [12].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To implement and validate the aforementioned strategies, researchers have developed detailed experimental protocols. The workflow for the Shot-Optimized ADAPT-VQE is particularly illustrative of the hybrid quantum-classical nature of these algorithms.

Figure 1: Workflow diagram for Shot-Optimized ADAPT-VQE, highlighting the critical loop of data generation and reuse. The process shows how Pauli measurement data from the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) parameter optimization step is stored and subsequently reused for the gradient evaluations that select the next operator, thereby reducing the required quantum resources.

- Initialization: The algorithm begins with a simple reference state, typically the Hartree-Fock state. A pool of candidate operators (e.g., fermionic or qubit excitations) is defined.

- VQE Optimization Loop: For the current ansatz, the parameters are optimized to minimize the energy expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian,

\langle H \rangle.- Measurement Strategy: The Hamiltonian

His decomposed into a sum of Pauli stringsP_i : H = \sum_i c_i P_i. The expectation value\langle H \rangleis computed by measuring eachP_iin the quantum computer. - Variance-Based Shot Allocation: Instead of distributing shots uniformly, the number of shots for measuring each

P_iis proportional to its coefficient|c_i|and its estimated variance. This allocates more resources to noisier or more significant terms. - Data Storage: All Pauli measurement outcomes are stored for potential reuse.

- Measurement Strategy: The Hamiltonian

- Gradient Evaluation for Operator Selection: The gradient

\frac{d}{d\theta_k}\langle e^{\theta_k A_k} H e^{-\theta_k A_k} \rangleis computed for every operatorA_kin the pool. This gradient is related to the expectation value of the commutatori\langle [H, A_k] \rangle.- Pauli Data Reuse: The commutator

[H, A_k]is expanded into a new set of Pauli strings. If any of these Pauli strings are identical to those already measured in Step 2, the stored outcomes are reused, eliminating the need for fresh quantum measurements.

- Pauli Data Reuse: The commutator

- Ansatz Growth: The operator with the largest gradient magnitude is selected and added to the ansatz circuit.

- Convergence Check: Steps 2-4 are repeated until the energy converges to a pre-defined threshold (e.g., chemical accuracy).

- Informationally Complete (IC) Measurement: Instead of measuring the energy via Pauli decompositions, the system's wavefunction is characterized using an Adaptive Informationally Complete Positive Operator-Valued Measure (IC-POVM). This single set of generalized measurements provides a complete description of the quantum state.

- Classical Post-Processing for Gradients: The rich dataset from the IC-POVM measurement is used to classically compute the expectation values of all commutators

[H, A_k]for the operator pool. This step requires no additional quantum measurements. - Operator Selection and Ansatz Growth: The operator with the largest gradient is selected and added to the circuit, as in the standard ADAPT-VQE algorithm.

- Iteration: The process repeats, with each energy evaluation via AIMs providing the data for the subsequent gradient evaluation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of measurement-efficient ADAPT-VQE requires a suite of conceptual and computational tools. The table below details these essential "research reagents."

Table 2: Essential Components for Implementing Measurement-Efficient ADAPT-VQE

| Component | Function & Role | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pool | A predefined set of unitary operators (e.g., fermionic excitations, Pauli strings) from which the ansatz is built. | Minimal "complete" pools [12] (size 2n-2) maximize efficiency. Pools must be symmetry-adapted to avoid convergence roadblocks. |

| Variance-Based Shot Allocator | A classical subroutine that dynamically distributes a finite shot budget among Hamiltonian terms to minimize total energy variance. | An optimal allocator assigns shots S_i ∠(c_i² Var[P_i]) [7], where c_i is the coefficient and Var[P_i] the variance of Pauli term P_i. |

| Commutator Expansion Table | A classical lookup table mapping each pool operator A_k to the Pauli strings constituting the commutator [H, A_k]. |

Pre-computing this table is crucial for identifying which Pauli measurements from the VQE step can be reused in the gradient step [7]. |

| Informationally Complete POVM | A generalized measurement scheme that fully characterizes the quantum state. | Replaces standard Pauli measurements. Enables gradient estimation via classical post-processing, but scalability to large systems remains a challenge [9]. |

| Overlap-Guided Target State | A classically computed, high-accuracy wavefunction (e.g., from Selected CI) used to guide ansatz growth. | Serves as an intermediate target in Overlap-ADAPT-VQE, steering the algorithm away from local energy minima and toward more compact ansätze [10]. |

| O-Demethylforbexanthone | O-Demethylforbexanthone, CAS:92609-77-3, MF:C18H14O6, MW:326.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Caboxine A | Caboxine A, MF:C22H26N2O5, MW:398.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The tension between circuit depth and measurement overhead in ADAPT-VQE is a central challenge in quantum computational chemistry. The strategies reviewed here—ranging from pragmatic data reuse and shot allocation to fundamentally rethinking measurements and pool design—demonstrate that this challenge is being actively and successfully addressed. The field is moving beyond simply identifying the problem toward developing a versatile toolkit of solutions.

The future path involves the refinement and synergistic combination of these strategies. For instance, integrating variance-based shot allocation with AIM-ADAPT-VQE could further optimize its initial energy measurement step. Furthermore, initializing an overlap-guided ansatz [10] before applying a shot-optimized ADAPT-VQE refinement could yield highly compact circuits with minimal total measurement cost. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, reducing both gate errors and measurement time, these algorithmic advances will be crucial for crossing the threshold into practical quantum advantage for drug development and materials discovery. The resolution of the measurement-depth trade-off is not a single solution but a layered approach, combining clever algorithmic design with principled resource management.

Why Resource Efficiency Matters for Quantum-Accelerated Drug Discovery

The drug discovery process is notoriously resource-intensive, often requiring over a decade and billions of dollars to bring a new therapeutic to market [13]. Quantum computing promises to revolutionize this field by simulating molecular interactions with unprecedented accuracy, potentially accelerating the identification and optimization of drug candidates. However, current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices face significant limitations in qubit coherence times, gate fidelities, and scalability. These constraints make resource efficiency—the optimal trade-off between computational accuracy and required quantum resources—a critical determinant for achieving practical quantum advantage in pharmaceutical research. The core challenge lies in developing algorithms that can deliver chemically accurate results while operating within the strict resource boundaries of today's quantum hardware, making the study of measurement costs versus circuit depth not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental requirement for progress.

Algorithmic Approaches: A Comparative Analysis of VQE and ADAPT-VQE

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for molecular simulations on NISQ devices. VQE operates on the variational principle, using a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) to prepare trial wavefunctions whose energy expectation values are minimized by a classical optimizer [5]. While VQE reduces circuit depth compared to phase estimation algorithms, its performance heavily depends on the ansatz choice. Predefined ansatze, such as Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC), often require deep circuits with many parameters, making them prone to decoherence and noise on current hardware.

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm represents a significant advancement by systematically constructing a problem-specific, compact ansatz. Instead of using a fixed ansatz, ADAPT-VQE grows the wavefunction one operator at a time, selecting the operator that yields the steepest energy gradient at each step [1]. This adaptive approach aims to construct a more efficient ansatz with fewer parameters and shallower circuit depth, directly addressing the resource constraints of NISQ devices.

Table 1: Algorithmic Comparison for Molecular Ground State Energy Calculation

| Feature | Standard VQE (with UCCSD) | ADAPT-VQE |

|---|---|---|

| Ansatz Definition | Fixed, based on pre-selected excitations (e.g., singles and doubles) [1] | Grows systematically, one operator at a time, tailored to the molecule [1] |

| Circuit Depth | Typically high, with a fixed number of parameters [5] | Shallower, with a smaller number of parameters [1] [5] |

| Resource Scaling | Can be prohibitively expensive for larger, correlated systems [1] | More economical, especially for strongly correlated molecules [1] |

| Optimization Robustness | Sensitive to initial parameters and optimizer choice; can get trapped in local minima [5] | More robust to optimizer choice and initial conditions [5] |

| Performance with Gradient-Based Optimizers | Variable performance; can struggle with convergence [5] | Superior performance and more reliable convergence [5] |

Table 2: Benchmarking Performance on Diatomic Molecules (Theoretical Simulation)

| Molecule | Algorithm | Achievable Chemical Accuracy | Relative Circuit Depth | Optimization Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | VQE (UCCSD) | Good | High | Moderate |

| Hâ‚‚ | ADAPT-VQE | Good | Low | High [5] |

| LiH | VQE (UCCSD) | Approximate | High | Low |

| LiH | ADAPT-VQE | High (Exact) | Low | High [1] |

| BeHâ‚‚ | VQE (UCCSD) | Approximate | Very High | Low |

| BeHâ‚‚ | ADAPT-VQE | High (Exact) | Moderate | High [1] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The ADAPT-VQE Methodology

The protocol for executing an ADAPT-VQE calculation involves a precise, iterative sequence of steps designed to build an efficient ansatz. The following diagram outlines the core workflow.

ADAPT-VQE Iterative Workflow

The process begins with the preparation of a reference state, typically the Hartree-Fock state. A pool of fermionic excitation operators is defined. The key iterative loop involves measuring the energy gradient with respect to each operator in the pool. The operator with the largest gradient magnitude is selected, and its corresponding unitary exponential is appended to the growing ansatz circuit. All parameters in the ansatz are then variationally optimized. This loop repeats until the energy gradient falls below a predefined threshold, signaling convergence to the ground state [1]. This method ensures that each added operator contributes maximally to energy lowering, leading to a compact and resource-efficient circuit.

Real-World Hybrid Quantum-Classical Implementation

Recent industrial applications demonstrate the translation of these principles into practical drug discovery workflows. A 2025 collaboration between IonQ, AstraZeneca, AWS, and NVIDIA showcased an end-to-end hybrid quantum-classical workflow for studying a critical Suzuki-Miyaura reaction, a transformation widely used in pharmaceutical synthesis [14].

Hybrid Quantum-Classical Workflow for Drug Discovery

In this workflow, the classical HPC resources (powered by NVIDIA GPUs) handled the bulk of the computation, while the quantum processor (IonQ's Forte QPU) was tasked with accelerating specific, computationally intensive sub-problems. This orchestration, managed by the NVIDIA CUDA-Q platform through Amazon Braket, achieved a more than 20-fold improvement in end-to-end time-to-solution compared to previous implementations, reducing the expected runtime from months to days while maintaining accuracy [14]. This exemplifies the tangible impact of resource-efficient hybrid design in a commercially relevant context.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Executing resource-efficient quantum-accelerated drug discovery requires a suite of specialized software, hardware, and chemical resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum-Accelerated Drug Discovery

| Tool / Platform | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Resource Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA CUDA-Q [14] [15] | Software Platform | An open-source hybrid quantum-classical computing platform. | Orchestrates workflows, enabling efficient use of QPUs alongside GPU-accelerated classical resources. |

| Amazon Braket [14] | Quantum Cloud Service | Provides managed access to various quantum hardware devices (e.g., IonQ Forte). | Democratizes access to different QPUs, allowing researchers to test algorithmic efficiency across architectures. |

| IonQ Forte QPU [14] | Hardware | A trapped-ion quantum processing unit. | Its high-fidelity gates make the execution of shallower circuits (like from ADAPT-VQE) more viable. |

| Operator Pools [1] | Algorithmic Component | A predefined set of fermionic or qubit operators for adaptive ansatz construction. | The composition of the pool directly dictates the convergence speed and final circuit depth of ADAPT-VQE. |

| Molecular Hamiltonian | Problem Input | The second-quantized electronic Hamiltonian of the target molecule or reaction. | Encodes the chemical problem; efficient mapping to qubits (e.g., via Jordan-Wigner) reduces qubit count and gate overhead. |

| 8-Debenzoylpaeoniflorin | 8-Debenzoylpaeoniflorin|High-Purity Reference Standard | 8-Debenzoylpaeoniflorin is a natural paeoniflorin derivative for research. Explore its potential in metabolic and pharmacological studies. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Antiarol rutinoside | Antiarol rutinoside, CAS:261351-23-9, MF:C21H32O13, MW:492.474 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Discussion: Interpreting the Data and Future Directions

The experimental data and case studies presented confirm that resource efficiency is not a secondary concern but a primary enabler for practical quantum applications in drug discovery. The ADAPT-VQE algorithm's ability to achieve chemical accuracy with shallower circuits directly addresses the most pressing constraint of NISQ devices: limited coherence time. The significant reduction in circuit depth, as benchmarked on molecules like LiH and BeHâ‚‚, translates to a higher probability of successful execution on real hardware before decoherence erases quantum information [1] [5].

The trade-off, however, often involves an increased measurement cost. The iterative process of measuring gradients for a large operator pool can require a substantial number of quantum circuit executions. This creates a critical research frontier: optimizing this measurement overhead through advanced techniques like operator grouping, classical shadow tomography, or more intelligent pool selection. The ultimate goal is an algorithm that minimizes both circuit depth and measurement complexity simultaneously.

Looking forward, the trajectory of the field is pointed toward more deeply integrated hybrid quantum-classical workflows, as exemplified by the IonQ-AstraZeneca collaboration [14]. As quantum hardware continues to improve, with error rates declining and qubit counts rising, the definition of "resource efficiency" will evolve. However, the fundamental principle of tailoring algorithmic design to hardware constraints will remain essential for unlocking the full potential of quantum computing to revolutionize drug discovery and development.

The path to quantum advantage in drug discovery is paved with resource-conscious algorithmic innovation. While brute-force approaches are currently infeasible, strategies like ADAPT-VQE, which intelligently manage the trade-off between circuit depth and measurement cost, provide a viable and demonstrably effective pathway. The experimental evidence shows that these methods can achieve the accuracy required for meaningful chemical simulation while operating within the stringent limitations of today's quantum hardware. As the industry moves forward, the continued co-design of efficient algorithms and powerful hardware will be paramount in transforming the quantum computing promise into a pharmaceutical reality.

In the noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) era, variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) have emerged as promising approaches for tackling complex chemical systems, with the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) representing a particularly advanced methodology for molecular simulations. The performance and accuracy of such algorithms are critically dependent on the efficient management of quantum resources, primarily characterized by CNOT gate counts, overall circuit depth, and quantum measurement overhead. These metrics directly determine a circuit's susceptibility to noise and its execution time, thereby influencing the feasibility and accuracy of quantum simulations on current hardware. As quantum computing transitions from theoretical exploration to practical application, understanding the trade-offs between these resource metrics becomes paramount for researchers, particularly in computationally intensive fields like drug development where quantum simulations promise significant advances.

The fundamental challenge in NISQ algorithm implementation lies in the delicate balance between circuit expressiveness and hardware limitations. Deeper circuits with higher CNOT counts inherently introduce more noise due to decoherence and gate errors, while insufficient circuit complexity may fail to capture necessary chemical correlations. Furthermore, the variational nature of algorithms like ADAPT-VQE necessitates extensive measurement campaigns to evaluate the energy expectation value, creating a complex trade-off space between circuit complexity, execution time, and measurement fidelity. This comparison guide objectively analyzes these inter-dependent metrics, providing researchers with a structured framework for evaluating quantum resource optimization strategies within the specific context of ADAPT-VQE implementations for molecular simulations.

Quantum Metric Fundamentals and Experimental Methodology

Defining Core Quantum Circuit Metrics

Circuit Depth measures the number of sequential computational steps required to execute a quantum circuit, corresponding to the critical path length. Traditional depth counts all gates along this path equally, while multi-qubit depth (also called CNOT depth) considers only multi-qubit operations, ignoring single-qubit gates entirely [16] [17]. A more sophisticated approach, gate-aware depth, weights gates according to their actual execution times on target hardware, providing a more accurate runtime estimation [16]. For example, on architectures where single-qubit RZ gates are implemented virtually via phase propagation and contribute zero quantum runtime, gate-aware depth appropriately weights these gates at zero [17].

CNOT Count specifically quantifies the number of two-qubit entangling gates in a circuit. This metric is particularly crucial as CNOT gates typically have error rates 5-10 times higher than single-qubit gates and significantly longer execution times [17]. Consequently, CNOT operations often dominate the error budget and runtime of quantum circuits, making their minimization a primary optimization target.

Measurement Costs encompass the quantum-classical overhead required to evaluate the expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian. Since individual Hamiltonian terms generally do not commute, the state preparation and measurement process must be repeated multiple times to gather sufficient statistics for each term in the Hamiltonian [1]. The total measurement cost scales with the number of Hamiltonian terms and the desired precision, creating significant overhead that must be managed efficiently, particularly for large molecular systems.

Experimental Protocols for Metric Evaluation

The quantitative comparisons presented in this guide are derived from established experimental methodologies in quantum computing research. Standardized benchmarking involves compiling representative quantum circuits (often including chemistry ansatze like UCCSD and ADAPT-VQE) using multiple optimization algorithms and then evaluating the resulting resource metrics against baseline implementations [16] [17].

Circuit Test Suite Protocol: Researchers typically employ a collection of 15-20 real quantum programs from 4 to 64 qubits commonly used for compiler benchmarking [16]. These circuits undergo compilation through different algorithms (e.g., those implemented in Qiskit, TKET, BQSKit) to generate multiple optimized versions for comparison [16] [17].

Metric Calculation Methodology: For each compiled circuit version, researchers calculate:

- Traditional depth by counting gates along the critical path with uniform weighting

- Multi-qubit depth by counting only multi-qubit gates along the critical path

- Gate-aware depth using architecture-specific weights based on average gate times

- Exact CNOT counts through circuit enumeration

- Runtime via circuit scheduling that constructs exact hardware-level execution timelines [16]

Accuracy Assessment Framework: Metric performance is evaluated through two primary tests:

- Relative Difference Prediction: Assessing how accurately relative differences in metrics predict actual runtime differences between compiled circuit versions

- Runtime Order Identification: Determining how accurately metrics identify the compiled version with the shortest actual runtime [16]

Table 1: Experimental Protocol for Quantum Metric Evaluation

| Protocol Phase | Key Components | Implementation Details |

|---|---|---|

| Circuit Compilation | 15-20 benchmark circuits (4-64 qubits) | Multiple compilation algorithms (Qiskit, TKET, BQSKit) |

| Metric Calculation | Traditional depth, Multi-qubit depth, Gate-aware depth, CNOT count | Architecture-specific weights for gate-aware depth |

| Validation | Circuit scheduling for exact runtime | Hardware-level execution timeline construction |

| Accuracy Assessment | Relative difference prediction, Runtime order identification | Comparison between metric predictions and actual runtimes |

Comparative Analysis of Quantum Resource Metrics

Accuracy Comparison of Depth Metrics

Recent research has demonstrated significant limitations in traditional depth metrics for accurately predicting quantum circuit performance. When comparing different compiled versions of the same circuit, traditional depth shows poor correlation with actual runtime because it fails to account for the substantial variations in gate execution times that characterize current quantum hardware [16]. Multi-qubit depth partially addresses this limitation by focusing exclusively on entangling gates but oversimplifies by completely ignoring the potential runtime impact of single-qubit gates, particularly when they appear in large numbers [17].

The introduction of gate-aware depth represents a substantial advancement in quantum circuit benchmarking. By incorporating architecture-specific gate times as weighting factors, this metric bridges the gap between abstract circuit analysis and physical hardware performance. Experimental evaluations on IBM Eagle and Heron architectures reveal that gate-aware depth reduces the average relative error in runtime predictions by 68 times compared to traditional depth and 18 times compared to multi-qubit depth [16]. Furthermore, gate-aware depth increases the accuracy of identifying the circuit version with the shortest runtime by an average of 20 percentage points over traditional depth and 43 percentage points over multi-qubit depth [16]. These improvements demonstrate the critical importance of hardware-aware metrics for accurate quantum performance estimation.

Table 2: Depth Metric Accuracy Comparison on IBM Architectures

| Depth Metric | Relative Error in Runtime Prediction | Runtime Order Identification Accuracy | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Depth | 68× higher vs. gate-aware | 20 percentage points lower vs. gate-aware | All gates have equal execution time |

| Multi-qubit Depth | 18× higher vs. gate-aware | 43 percentage points lower vs. gate-aware | Single-qubit gates contribute zero time |

| Gate-aware Depth | Baseline (lowest error) | Baseline (highest accuracy) | Gates weighted by architecture-specific average times |

CNOT Reduction Techniques and Performance Impacts

CNOT gate optimization represents a particularly effective strategy for enhancing quantum circuit performance due to the disproportionate error rates and execution times associated with two-qubit operations. Advanced synthesis techniques like HOPPS (Hardware-Aware Optimal Phase Polynomial Synthesis) have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in CNOT reduction, achieving up to 50% reduction in CNOT counts and 57.1% reduction in CNOT depth through specialized optimization algorithms [18]. These reductions directly translate to significant improvements in circuit fidelity, as each eliminated CNOT gate removes a substantial source of potential error.

The implementation of blockwise optimization strategies further enhances the scalability of CNOT reduction techniques. By partitioning large circuits into smaller, manageable blocks and applying intensive optimization to each segment iteratively, this approach maintains optimization efficacy while managing computational overhead [18]. For larger circuits mapped to realistic quantum hardware, this iterative blockwise optimization combined with HOPPS achieves substantial reductions in both CNOT count (up to 44.4%) and depth (up to 42.4%) [18]. These optimization strategies are particularly valuable for ADAPT-VQE circuits, which build ansatze iteratively and can benefit from intermediate optimization steps during the ansatz construction process.

ADAPT-VQE Specific Resource Characteristics

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm introduces unique resource characteristics that differentiate it from fixed-ansatz approaches. Unlike unitary coupled cluster (UCCSD) methods that employ a predetermined operator sequence, ADAPT-VQE grows its ansatz systematically by adding operators one at a time based on gradient information specific to the target molecule [1]. This adaptive approach generates ansatze with significantly fewer parameters than UCCSD, resulting in shallower circuit depths and enhanced suitability for NISQ devices [1].

Numerical simulations demonstrate ADAPT-VQE's superior resource efficiency compared to traditional approaches. For prototypical strongly correlated molecules, ADAPT-VQE achieves chemical accuracy with substantially fewer operators and shallower circuits than UCCSD [1]. This resource reduction directly addresses one of the primary limitations of VQE implementations - the compromise between ansatz expressiveness and circuit depth - by dynamically constructing problem-specific ansatze that maximize accuracy per quantum resource unit. However, this advantage comes with increased classical computation for gradient calculations and operator selection, representing a different resource trade-off than fixed-ansatz methods.

Measurement Cost Analysis in Variational Algorithms

Hamiltonian Measurement Overhead

The evaluation of energy expectation values in VQE frameworks requires extensive measurement due to the non-commuting nature of Hamiltonian terms. For a molecular Hamiltonian expressed as Ĥ = Σgᵢôᵢ, each individual operator term must be measured separately, necessitating repeated state preparation and measurement cycles [1]. The number of measurement rounds scales with both the number of Hamiltonian terms (which grows as O(Nâ´) for quantum chemistry problems with N basis functions) and the desired statistical precision, creating a significant computational bottleneck.

Measurement costs are particularly consequential for ADAPT-VQE due to its iterative nature. Each iteration requires calculating energy gradients for multiple candidate operators, potentially multiplying the measurement overhead compared to standard VQE. Research into measurement reduction strategies has identified several effective approaches, including Hamiltonian term grouping (where commuting terms are measured simultaneously), classical shadow techniques, and importance sampling that prioritizes high-weight Hamiltonian terms [5]. These strategies can reduce measurement costs by up to an order of magnitude, making ADAPT-VQE simulations more feasible on near-term devices.

Trade-offs Between Circuit Depth and Measurement Costs

A critical trade-off space exists between circuit depth and measurement requirements in ADAPT-VQE implementations. Deeper, more expressive circuits typically require fewer measurement iterations to achieve chemical accuracy because they better approximate the true ground state, potentially reducing the number of optimization steps needed for convergence. However, these deeper circuits suffer from increased decoherence and gate errors, potentially compromising result fidelity. Conversely, shallower circuits may maintain higher fidelity per execution but often require more measurement iterations and optimization cycles to achieve target accuracy [5].

This trade-off is explicitly managed in the ADAPT-VQE algorithm through its operator selection process. The method prioritizes operators that provide the greatest energy gradient improvement per added circuit depth, effectively optimizing the resource allocation between circuit complexity and measurement requirements [1]. Numerical simulations for molecules like Hâ‚‚, NaH, and KH demonstrate that ADAPT-VQE navigates this trade-off more effectively than fixed-ansatz approaches, achieving superior accuracy with comparable or reduced total resource expenditure [5].

Research Toolkit for Quantum Metric Evaluation

Essential Software and Compilation Tools

Quantum resource optimization requires specialized software tools for circuit compilation, metric evaluation, and hardware integration. The Qiskit (IBM), TKET (Cambridge Quantum), and BQSKit (Berkeley) frameworks provide comprehensive compilation flows that transform high-level algorithm descriptions into hardware-executable circuits while optimizing for metrics like CNOT count and circuit depth [16] [17]. These frameworks implement various optimization techniques, including gate cancellation, commutation rules, and hardware-aware mapping, to enhance circuit performance.

Specialized synthesis tools like HOPPS extend these capabilities with focused optimization algorithms specifically targeting CNOT reduction and depth minimization [18]. HOPPS employs SAT-based solving and phase polynomial representation to generate circuits with provably optimal CNOT counts for specific subcircuits, achieving up to 50% reduction in CNOT gates compared to standard compilation [18]. When integrated as a peephole optimizer within broader compilation workflows, these specialized tools significantly enhance overall circuit quality, particularly for the CNOT-heavy subcircuits common in quantum chemistry simulations.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Quantum Metric Evaluation

| Tool Category | Representative Examples | Primary Function | Application in Metric Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Compilation Frameworks | Qiskit, TKET, BQSKit | Circuit transformation & hardware mapping | Generate optimized circuit variants for comparison |

| Specialized Synthesizers | HOPPS | Phase polynomial synthesis & CNOT optimization | Achieve near-optimal CNOT counts for subcircuits |

| Circuit Scheduling Tools | Qiskit Scheduler, TrueQ | Hardware-level runtime calculation | Validate depth metrics against actual execution time |

| Metric Calculation Libraries | SupermarQ, MQTBench | Standardized metric evaluation | Consistent measurement across different circuit types |

| Architecture Specification | IBM Backend Specifications | Gate time & topology definition | Configure gate-aware depth weights for specific hardware |

| withanoside IV | withanoside IV, CAS:362472-81-9, MF:C40H62O15, MW:782.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Dihydrocephalomannine | Dihydrocephalomannine, CAS:159001-25-9, MF:C45H55NO14, MW:833.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Hardware-Specific Configuration Parameters

Accurate metric evaluation requires careful attention to hardware-specific parameters that significantly influence quantum circuit performance. Gate time characteristics vary substantially across quantum processing architectures, with two-qubit gates typically requiring 2-10 times longer execution times than single-qubit gates [17]. For example, on IBM's superconducting architectures, single-qubit gates may execute in nanoseconds while two-qubit gates require hundreds of nanoseconds. Furthermore, specific gates like the RZ rotation are often implemented virtually through phase propagation on many platforms, contributing zero quantum runtime [17].

These hardware characteristics directly inform the weight configurations for gate-aware depth calculations. For IBM Eagle and Heron architectures, researchers have derived specific weight configurations that reflect the relative execution times of native gates [16] [17]. These configurations typically assign zero weight to virtual RZ gates, fractional weights to other single-qubit gates based on their actual execution times relative to the slowest two-qubit gate, and a weight of 1.0 to the slowest two-qubit gate type [16]. This hardware-aware weighting scheme enables much more accurate runtime predictions than simplified metrics, highlighting the importance of architecture-specific calibration for meaningful quantum resource analysis.

The comprehensive evaluation of CNOT counts, circuit depth, and measurement costs reveals a complex optimization landscape for ADAPT-VQE and similar variational quantum algorithms. Traditional metrics like uniform circuit depth provide inadequate guidance for runtime prediction, while emerging hardware-aware metrics like gate-aware depth offer substantially improved accuracy by incorporating architecture-specific timing information [16]. The demonstrated superiority of gate-aware depth (68× more accurate than traditional depth for runtime prediction) underscores the critical importance of hardware-informed metric design for meaningful quantum performance evaluation [16].

For researchers focusing on drug development applications, these findings highlight several strategic considerations. First, CNOT reduction should remain a primary optimization target due to the disproportionate error contribution of two-qubit gates, with techniques like HOPPS synthesis offering proven effectiveness [18]. Second, measurement costs must be evaluated in conjunction with circuit depth rather than in isolation, recognizing their inherent trade-off in variational algorithms. Finally, the adaptive nature of ADAPT-VQE provides inherent advantages for resource-constrained optimization by constructing problem-specific ansatze that maximize accuracy per quantum resource [1]. As quantum hardware continues evolving with demonstrations of increasing Quantum Volume (reaching 2²³ = 8,388,608 on Quantinuum's H2 system) and enhanced error correction capabilities, the optimal balance between these resource metrics will continue shifting toward more complex circuits with lower error rates [19]. This progression will likely enable more accurate simulation of larger molecular systems, potentially transforming early-stage drug discovery through high-accuracy quantum chemistry calculations.

Advanced Methods for Reducing ADAPT-VQE Resource Requirements

Novel Operator Pools: The Coupled Exchange Operator Approach

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a significant advancement in quantum algorithms for molecular simulations on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. Unlike static ansätze such as Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC), which employ a fixed circuit structure, ADAPT-VQE dynamically constructs an ansatz by iteratively appending parameterized unitaries from a predefined operator pool. This process is guided by a greedy selection of operators based on the magnitude of their energy gradient, ensuring that each new operator provides the maximal possible reduction in energy at that step [1]. The algorithm's efficiency, accuracy, and trainability are profoundly influenced by the choice of this operator pool [2]. The primary challenge in designing these pools lies in balancing competing resource demands: circuit depth (a proxy for how long a computation runs on fragile quantum hardware) and measurement costs (the number of times a quantum state must be prepared and measured to estimate the energy) [2] [20]. Early ADAPT-VQE implementations used fermionic pools of generalized single and double (GSD) excitations, which preserve physical symmetries like particle number but often result in deep quantum circuits with high measurement overhead [2]. This review objectively compares the performance of a novel operator pool—the Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool—against established alternatives, framing the analysis within the critical research context of the measurement-cost versus circuit-depth trade-off.

The Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) Pool: A Paradigm Shift

The Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool is a novel ansatz construction designed specifically to address the resource bottlenecks of earlier ADAPT-VQE variants [2]. Its development was motivated by an analysis of the structure of qubit excitations, aiming to create a hardware-efficient pool that maintains favorable convergence properties while dramatically reducing quantum resource requirements.

Conceptual Foundation and Design

The CEO pool is built upon the principle of coupled exchange processes. Unlike the fermionic GSD pool, which is composed of operators that directly correspond to exciting electrons from occupied to virtual orbitals in a quantum chemistry context, the CEO pool incorporates operators that natively encapsulate the simultaneous exchange of multiple particles [2]. From a quantum information perspective, this approach can be understood as a form of qubit excitation, but with a crucial design constraint: the preservation of essential physical symmetries. While an earlier variant known as qubit-ADAPT broke down fermionic excitations into individual Pauli terms and discarded the anti-commutation Z strings from the Jordan-Wigner transformation—leading to significantly reduced circuit depths but a complete breakdown of particle-number conservation—the CEO pool is engineered to retain this critical symmetry [2] [20]. By conserving the particle number and the total Z spin projection (S₂), the CEO pool ensures that the variational search remains within a physically meaningful subspace of the full Hilbert space, which is a key factor in its improved convergence and accuracy compared to symmetry-breaking pools [20].

Logical Workflow of CEO-ADAPT-VQE

The following diagram illustrates the functional workflow of the ADAPT-VQE algorithm when utilizing the CEO pool, highlighting its iterative and adaptive nature.

Figure 1: The CEO-ADAPT-VQE algorithm iteratively builds an ansatz by selecting operators from the CEO pool based on their energy gradient, optimizing the parameters, and checking for convergence until chemical accuracy is achieved.

Performance Comparison: CEO-ADAPT-VQE vs. Alternative Approaches

A comprehensive performance comparison reveals the significant advantages of the CEO-ADAPT-VQE algorithm over both static ansätze and earlier adaptive variants. The key metrics for evaluation are CNOT gate count (a primary contributor to circuit noise), CNOT depth (determining execution time), and the total number of measurements required.

Quantitative Benchmarking Against Fermionic ADAPT-VQE

The most direct evidence of the CEO pool's efficiency comes from a comparison with the original fermionic (GSD) ADAPT-VQE. Simulations on molecules such as LiH (12 qubits), H₆ (12 qubits), and BeH₂ (14 qubits) demonstrate dramatic resource reductions [2].

Table 1: Resource Reduction of CEO-ADAPT-VQE vs. GSD-ADAPT-VQE at Chemical Accuracy

| Molecule | CNOT Count Reduction | CNOT Depth Reduction | Measurement Cost Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| LiH | 88% | 96% | 99.6% |

| H₆ | 88% | 96% | 99.6% |

| BeHâ‚‚ | Up to 88% | Up to 96% | Up to 99.6% |

These figures indicate that CEO-ADAPT-VQE requires only 12% of the CNOT gates, 4% of the CNOT depth, and a mere 0.4% of the measurement costs compared to the early fermionic ADAPT-VQE algorithm [2]. This represents a monumental leap in algorithm efficiency, bringing practical quantum advantage on NISQ devices substantially closer.

Comparative Analysis with Other Adaptive and Static Ansätze

The CEO pool's performance remains competitive when evaluated against other state-of-the-art adaptive pools and the most widely used static ansatz, UCCSD.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Different Ansätze for Molecular Simulations

| Ansatz / Algorithm | CNOT Count | Circuit Depth | Measurement Cost | Symmetry Preservation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE | Low | Very Shallow | Very Low | Particle Number, Sâ‚‚ |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE | Low | Very Shallow | Low | Breaks Symmetries |

| QEB-ADAPT-VQE | Low | Shallow | Low | Particle Number |

| GSD-ADAPT-VQE (Fermionic) | Very High | Deep | Very High | Particle Number |

| UCCSD (Static) | High | Deep | Extremely High | Particle Number |

The table shows that the CEO pool occupies a unique sweet spot. It matches the hardware efficiency (low CNOT count and shallow depth) of other qubit-based pools like qubit-ADAPT and QEB-ADAPT, while definitively outperforming them in terms of measurement costs [2]. Specifically, CEO-ADAPT-VQE offers a five orders of magnitude decrease in measurement costs compared to other static ansätze with similar CNOT counts [2]. Furthermore, unlike qubit-ADAPT, which breaks physical symmetries, the CEO pool explicitly conserves particle number and S₂, leading to a more physically constrained and often more efficient convergence path [20]. When compared to the UCCSD ansatz, CEO-ADAPT-VQE outperforms it in "all relevant metrics," including faster convergence to the ground state and lower resource requirements across the entire potential energy surface of a molecule [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear basis for the performance data cited, this section details the standard experimental protocols used in benchmarking quantum algorithms like ADAPT-VQE.

Core Computational Workflow

The general methodology for conducting these comparisons involves several standardized steps [2] [1] [5]:

- Molecular System Selection and Hamiltonian Generation: A set of molecules of varying complexity (e.g., LiH, BeH₂, H₆) is selected. Their electronic structure Hamiltonians are generated classically using quantum chemistry packages and then mapped to a qubit representation via a transformation like Jordan-Wigner.

- Algorithm Configuration: Different ADAPT-VQE variants are configured by specifying their operator pools (CEO, GSD, QEB, qubit). The classical optimizer (often a gradient-based method) is also selected.

- Iterative Ansatz Construction and Optimization: For each adaptive algorithm, the iterative process depicted in Figure 1 is followed. The algorithm runs until the energy of the prepared quantum state reaches chemical accuracy (typically defined as an error within 1.6 mHa or 1 kcal/mol relative to the full configuration interaction energy).

- Resource Tallying: Upon convergence, the following resources are tallied for each run:

- CNOT Count: The total number of CNOT gates in the final, optimized quantum circuit.

- CNOT Depth: The longest sequential path of CNOT gates in the circuit, a key metric for execution time on hardware.

- Number of Parameters: The total number of variational parameters in the final ansatz.

- Measurement Costs: Estimated as the total number of noiseless energy evaluations required throughout the entire optimization process. This serves as a lower bound for the actual number of quantum measurements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table details the essential computational "reagents" and their functions in this field of research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for ADAPT-VQE Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function and Role in the Experiment | |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Hamiltonian | The target operator representing the energy of the molecular system; the core object whose ground state is being sought. | |

| Qubit Mapping (e.g., Jordan-Wigner) | Transforms the fermionic Hamiltonian into a sum of Pauli strings operable on a quantum computer. | |

| Reference State (e.g., Hartree-Fock) | The initial, unentangled quantum state (e.g., | 0⟩) from which the adaptive ansatz is built. |

| Operator Pool (CEO, GSD, etc.) | The predefined set of operators (e.g., Âpq = i(âpâq - âqâp)) from which the ansatz is constructed. | |

| Classical Optimizer | The algorithm (e.g., gradient-based BFGS) that adjusts variational parameters to minimize the energy expectation value. | |

| Quantum Circuit Simulator | Software that emulates the execution of quantum circuits to perform noiseless benchmarks and algorithm development. | |

| Boeravinone O | Boeravinone O | |

| Acetylvirolin | Acetylvirolin, MF:C23H28O6, MW:400.5 g/mol |

The Measurement-Cost vs. Circuit-Depth Trade-Off: The CEO Pool's Strategic Position

The central thesis in modern ADAPT-VQE research involves the trade-off between the quantum resources of measurement cost and circuit depth. The CEO pool's design offers a compelling resolution to this tension.

Conceptualizing the Trade-Off

The trade-off arises from two fundamental constraints of NISQ hardware:

- Circuit Depth Limit: Deep circuits (long sequences of gates) are vulnerable to decoherence and cumulative gate errors, which destroy quantum information.

- Measurement Budget: Each evaluation of the energy expectation value requires a large number of measurements (shots) of the quantum state to achieve sufficient statistical precision, especially for complex molecular Hamiltonians with many terms. This process is time-consuming and expensive.

Some strategies, like the hardware-efficient ansatz, prioritize shallow circuits at the expense of a difficult optimization landscape that can require a vast number of measurements (a problem known as "barren plateaus") [2]. Conversely, physically-inspired ansätze like UCCSD may have a smoother landscape but impose prohibitively deep circuits and correspondingly high measurement costs. The CEO pool directly addresses this dilemma. Its compact circuit decomposition leads to very shallow depths, mitigating decoherence concerns. Simultaneously, its preservation of physical symmetries like particle number constrains the variational search to a relevant subspace of the Hilbert space. This leads to faster, more robust convergence, which in turn drastically reduces the number of iterative steps and classical optimization cycles required. Since each optimization cycle requires a fresh set of quantum measurements, this convergence improvement is the direct cause of the up to 99.6% reduction in measurement costs [2]. As one study notes, while circuit depth is the current primary bottleneck, measurement costs (shot counts) are anticipated to be the limiting factor in future, error-corrected quantum devices [20]. The CEO pool's performance makes it a strong candidate for both near-term and future hardware paradigms.

CEO Operator Mechanism

The following diagram conceptualizes how a CEO operator functions within a quantum circuit compared to a more traditional, decomposed approach.

Figure 2: A CEO operator achieves efficiency by acting as a more native, compact quantum gate that preserves symmetry, unlike a traditional fermionic operator which must be decomposed into many fundamental gates, increasing overhead.

In the evolving landscape of adaptive variational quantum algorithms, the Coupled Exchange Operator pool represents a state-of-the-art advancement. By combining a hardware-efficient design with the explicit preservation of physical symmetries, it successfully navigates the critical trade-off between circuit depth and measurement cost. Empirical data demonstrates its superiority over previous fermionic and qubit-ADAPT variants, showing reductions in CNOT counts and depth by up to 88% and 96%, respectively, while slashing measurement costs by up to 99.6%. When framed within the broader research objective of achieving practical quantum advantage in molecular simulation—particularly for applications in drug discovery and materials science—the CEO-ADAPT-VQE algorithm emerges as a leading candidate, offering a pragmatic and powerful pathway toward exact molecular simulations on both near-term and future quantum hardware.

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) has emerged as a promising algorithm for molecular simulations on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. Unlike traditional VQE that uses a predefined ansatz, ADAPT-VQE builds the quantum circuit adaptively, adding operators iteratively to recover maximal correlation energy at each step [1]. This approach generates ansatze with fewer parameters and shallower circuit depths compared to unitary coupled cluster (UCC) methods, making it particularly valuable for devices limited by coherence times [21].

However, this advantage comes with a significant challenge: substantially increased quantum measurement overhead [7]. Each ADAPT-VQE iteration requires extensive measurements for both variational parameter optimization and operator selection for the subsequent iteration, creating a critical trade-off between circuit depth and measurement costs [7]. This article compares two innovative protocols—Pauli measurement reuse and variance-based shot allocation—that address this measurement bottleneck while maintaining chemical accuracy.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Pauli Measurement Reuse Protocol

The Pauli measurement reuse strategy leverages the structural relationship between the Hamiltonian measurement requirements during VQE optimization and the commutator-based gradient measurements used for operator selection in ADAPT-VQE [7].

Workflow Implementation:

- Initial Pauli String Analysis: During setup, identify all Pauli strings required for measuring both the Hamiltonian (

H) and the commutators[H, A_i]for all operatorsA_iin the pool. - VQE Optimization Phase: Perform standard quantum measurements for all Hamiltonian Pauli strings during parameter optimization, storing all results.

- Operator Selection Phase: For gradient calculations in operator selection, instead of performing new measurements, reuse relevant previously obtained Pauli measurement outcomes from the optimization phase.

- Iterative Reuse: Continue this reuse pattern across all ADAPT-VQE iterations, with each VQE optimization providing measurement data for the subsequent operator selection.

This protocol capitalizes on the mathematical relationship that gradients of the energy with respect to operator parameters can be expressed as expectation values of commutators [H, A_i], which often contain Pauli strings in common with the Hamiltonian itself [7].

Variance-Based Shot Allocation Protocol

Variance-based shot allocation optimizes measurement distribution across all required observables based on their statistical properties and contribution to the total variance [7].

Implementation Methodology:

- Commuting Term Grouping: Group Pauli terms from both Hamiltonian and gradient observables using qubit-wise commutativity (QWC) or more advanced grouping techniques.

- Variance Estimation: For each group, estimate the variance of each term through initial sampling or theoretical bounds.

- Optimal Shot Allocation: Distribute the total shot budget

S_totalacross all terms according to the formula:

s_i ∠(σ_i / ε_target)^2

where s_i is the shots allocated to term i, σ_i is its estimated standard deviation, and ε_target is the desired precision.

- Iterative Refinement: Update variance estimates and reallocate shots as the optimization progresses and wavefunction parameters change.

This approach is adapted from theoretical optimum allocation principles [7] and extends beyond Hamiltonian measurement to include gradient measurements specifically for ADAPT-VQE.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Shot Reduction Performance of Pauli Measurement Reuse Protocol

| Molecular System | Qubit Count | Shot Reduction with Grouping Only | Shot Reduction with Grouping + Reuse |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | 4 | 38.59% | 32.29% |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | 38.59% | 32.29% |

| Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„ | 16 | 38.59% | 32.29% |

Table 2: Performance of Variance-Based Shot Allocation in ADAPT-VQE

| Molecular System | Shot Allocation Method | Shot Reduction vs. Uniform | Chemical Accuracy Maintained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | VMSA | 6.71% | Yes |

| Hâ‚‚ | VPSR | 43.21% | Yes |

| LiH | VMSA | 5.77% | Yes |

| LiH | VPSR | 51.23% | Yes |

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Shot-Efficient Protocols

| Protocol | Key Mechanism | Circuit Depth Impact | Classical Overhead | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pauli Measurement Reuse | Leverages measurement overlap between VQE and gradient steps | Neutral | Low (primarily initial setup) | Excellent to ~16 qubits |

| Variance-Based Shot Allocation | Optimizes shot distribution based on term variances | Neutral | Moderate (ongoing variance estimation) | Good for larger systems |

| Combined Approach | Integrates both reuse and variance optimization | Neutral | Moderate | Best overall efficiency |

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Type | Function in ADAPT-VQE Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC) Grouping | Algorithm | Groups commuting Pauli terms to reduce measurement circuits |

| Jordan-Wigner Transformation | Encoding Method | Maps fermionic operators to qubit representations |

| Molecular Hamiltonians (Hâ‚‚, LiH, BeHâ‚‚, Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„) | Test Systems | Provide benchmark systems of increasing complexity |

| Gradient-Based Optimizers | Classical Algorithm | Efficiently adjusts variational parameters |

| Shot Budget Allocation Framework | Resource Manager | Distributes quantum measurements optimally |

| Chemical Accuracy Metric | Benchmark | Target precision of 1.6 mHa or 1 kcal/mol |

The integration of Pauli measurement reuse and variance-based shot allocation presents a promising path forward for practical ADAPT-VQE implementations on NISQ devices. While the Pauli reuse protocol demonstrates significant shot reduction (32.29% on average) across various molecular systems [7], and variance-based methods show even greater potential (up to 51.23% reduction for specific systems) [7], their combination offers the most comprehensive approach to measurement optimization.

These protocols directly address the fundamental trade-off in ADAPT-VQE: shallower circuits come at the cost of increased measurement overhead. By significantly reducing this overhead while maintaining chemical accuracy, these shot-efficient strategies enhance the feasibility of quantum simulations for drug development researchers investigating complex molecular systems. Future work should focus on scaling these approaches to larger molecular systems and integrating them with advanced measurement techniques like derandomization and classical shadows to further push the boundaries of practical quantum computational chemistry.

In the pursuit of quantum advantage using near-term devices, managing circuit depth is a critical challenge due to the limited coherence times of noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) processors. This guide compares two innovative strategies for circuit depth optimization: non-unitary circuits and measurement-based techniques. Both approaches aim to reduce the resource requirements of quantum algorithms, particularly the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and its adaptive variant, ADAPT-VQE, which are pivotal for molecular simulations in fields like drug discovery. The trade-off between circuit depth and measurement overhead forms the core thesis of this analysis, as advancements in one often impact the other. We provide a detailed, data-driven comparison of these methodologies, including experimental protocols and performance benchmarks, to guide researchers in selecting the optimal approach for their specific applications.

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and challenges of the two depth-optimization techniques discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Comparison of Depth Optimization Techniques

| Feature | Non-Unitary Circuits | Measurement-Based Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Use additional qubits and mid-circuit measurements to perform non-unitary operations, collapsing probabilistic outcomes. [22] [23] | Use entanglement (cluster states) and sequential single-qubit measurements to perform computations; the circuit is "measured into existence." [24] |

| Key Enablers | Singular Value Decomposition (SVD), ancillary qubits, classical post-processing of measurement results. [22] [23] | Universal cluster states, adaptive measurement sequences, quantum teleportation for information propagation. [24] |

| Impact on Circuit Depth | Reduces the depth of variational quantum algorithm circuits. [23] | Shifts computational load from gate depth to the preparation of a universal entangled resource state. [24] |

| Primary Overhead | Qubit count (additional ancilla qubits). [22] [23] | Qubit count (large entangled cluster states) and classical coordination for adaptive measurements. [24] |

| Representative Applications | Quantum linear transformations, simulation of fluid dynamics. [22] [23] | Universal quantum computation, single-qubit rotations, two-qubit gates. [24] |

Performance Benchmarks and Experimental Data

The optimization of quantum circuits is ultimately measured by concrete reductions in resource requirements. The table below synthesizes key performance metrics reported for various optimization strategies applied to molecular systems.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics for Optimized Quantum Algorithms

| Molecule (Qubits) | Algorithm / Technique | Key Performance Metric | Reported Improvement/Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ (4) to BeHâ‚‚ (14) | ADAPT-VQE with Reused Pauli Measurements [7] | Shot Reduction | Average shot usage reduced to 32.29% of naive scheme [7] |

| LiH (12), H₆ (12), BeH₂ (14) | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* (State-of-the-art) [2] | CNOT Count | Reduced by 73% to 88% vs. original ADAPT-VQE [2] |

| LiH (12), H₆ (12), BeH₂ (14) | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* (State-of-the-art) [2] | CNOT Depth | Reduced by 92% to 96% vs. original ADAPT-VQE [2] |

| LiH (12), H₆ (12), BeH₂ (14) | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* (State-of-the-art) [2] | Measurement Costs | Reduced by 98% to 99.6% vs. original ADAPT-VQE [2] |

| Various (e.g., Hâ‚„) | AIM-ADAPT-VQE (Using IC measurements) [25] | Measurement Overhead | Energy measurement data can be reused for gradients with no additional overhead for tested systems [25] |

| Generic Workflows | Non-Unitary Circuits [23] | Circuit Depth | Depth reduction achieved by introducing ancillary qubits and mid-circuit measurements [23] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear technical pathway, this section details the core experimental methodologies for the featured techniques.

Protocol 1: Non-Unitary Circuit Implementation via SVD

This protocol enables non-unitary basis transformations on quantum hardware, which is useful for mapping wavefunctions between different bases and reducing circuit depth. [22]

- Problem Formulation: Define the target non-unitary operation ( A ) that needs to be applied to a quantum state ( |\psi\rangle ).

- Singular Value Decomposition (SVD): Decompose the operation as ( A = U S V^\dagger ), where ( U ) and ( V^\dagger ) are unitary matrices, and ( S ) is a diagonal matrix of singular values. [22]

- Ancilla System Introduction: Introduce ( n ) ancillary qubits, where ( n ) is related to the dimension of ( A ). The total system size becomes the sum of the original qubits and the ancilla qubits. [22]

- Unitary Embedding: Construct a larger unitary operation that acts on the combined system of original and ancilla qubits. This unitary is designed such that when the ancilla qubits are prepared in a specific state (e.g., ( |0\rangle )) and later measured, the effect on the original qubits is equivalent to the application of ( A ), probabilistically. [22]