Overcoming ADAPT-VQE Scaling Challenges: From Quantum Hardware Limits to Real-World Drug Discovery

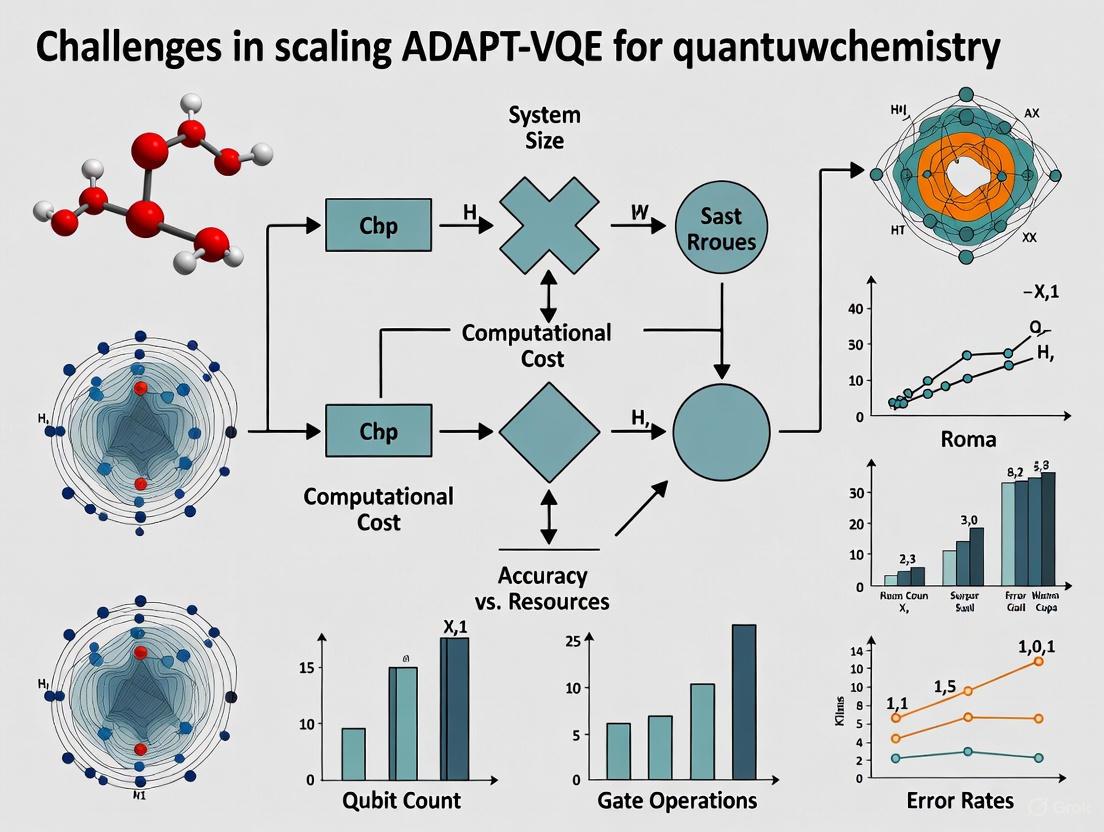

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the primary challenges in scaling the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) for practical quantum chemistry applications, particularly in drug discovery.

Overcoming ADAPT-VQE Scaling Challenges: From Quantum Hardware Limits to Real-World Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the primary challenges in scaling the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) for practical quantum chemistry applications, particularly in drug discovery. It explores the foundational limitations of current quantum hardware, including the wiring problem and measurement overhead. The piece details methodological innovations like novel operator pools and algorithmic improvements, examines advanced optimization strategies such as circuit pruning and shot-efficient techniques, and validates these approaches through comparative analysis and real-world biomedical case studies. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes the current state of ADAPT-VQE and its pathway toward enabling quantum advantage in molecular simulation.

The Fundamental Scaling Bottlenecks: Why ADAPT-VQE Hits a Wall in Quantum Chemistry

For researchers in quantum chemistry, the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and its adaptive variant, ADAPT-VQE, represent promising pathways for simulating molecular electronic systems and predicting chemical properties with accuracy potentially surpassing classical computational methods [1]. These algorithms are particularly valuable for modeling systems where electrons are strongly correlated—a scenario where classical approaches often fail but which is common in many materials with useful electronic and magnetic properties [1].

However, the practical application of these algorithms faces a fundamental constraint: they must be executed on quantum hardware that is itself in a transitional phase of development. Current quantum devices remain constrained by significant hardware limitations that directly impact their ability to run meaningful quantum chemistry simulations. The fidelity of qubit operations, control complexity, and architectural bottlenecks collectively form a critical roadblock that researchers must navigate to advance quantum computational chemistry [2]. This whitepaper examines these hardware limitations within the specific context of scaling ADAPT-VQE applications for drug discovery and materials science research.

Hardware Limitations in the NISQ Era

The Qubit Quality Challenge

The current landscape of quantum hardware is dominated by Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, which operate under an inherent and limiting constraint: an unfavorable trade-off between circuit depth and fidelity [2]. While physical qubit counts have steadily increased across all hardware platforms, this growth has not been matched by equivalent improvements in qubit quality and stability. Quantum processors face constant environmental interference from stray photons, flux noise, and charge fluctuations that collectively randomize fragile quantum states [2].

The table below summarizes current state-of-the-art performance metrics across different qubit modalities:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Leading Qubit Platforms

| Platform | Single-Qubit Gate Error | Two-Qubit Gate Error | Coherence Time | Record Holder/Institution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trapped Ions | 0.000015% [3] [4] | ~0.05% (1 in 2000) [4] | Not Specified | University of Oxford |

| Superconducting | Not Specified | <0.1% (1 in 1000) [5] | 0.6 milliseconds [6] | IBM / Google |

| Neutral Atoms | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | Atom Computing / QuEra |

The dramatically higher error rates for two-qubit gates compared to single-qubit operations highlight a critical challenge for quantum chemistry simulations. ADAPT-VQE circuits typically require entangling operations between multiple qubits to model molecular interactions, making these two-qubit gate errors particularly detrimental to calculation accuracy [1].

The Wiring Problem

As quantum processors scale, the "wiring problem" emerges as a fundamental constraint. Traditional quantum computing architectures require numerous control signals—typically one dedicated control line per qubit—creating immense physical complexity when scaling to hundreds or thousands of qubits [7]. This interconnect challenge is particularly acute for superconducting quantum processors, which operate at cryogenic temperatures where thermal management and physical space for wiring become increasingly problematic.

Quantinuum has addressed this challenge in their trapped-ion systems through a novel approach that utilizes a fixed number of analog signals combined with a single digital input per qubit, significantly minimizing control complexity [7]. This method, implemented with a uniquely designed 2D trap chip, enables more efficient qubit movement and interaction while overcoming the limitations of traditional linear or looped configurations [7].

The Sorting Problem

Closely related to the wiring problem is the "sorting problem"—the challenge of efficiently moving and interacting qubits within a processor architecture. In trapped-ion systems, this involves physically rearranging ions to perform specific gate operations; in superconducting systems, it relates to the qubit connectivity and the need for SWAP gates to facilitate interactions between non-adjacent qubits [7].

The sorting problem directly impacts the quantum volume of a device and its efficiency in executing complex quantum circuits like those required for ADAPT-VQE simulations. Solutions that enable efficient qubit routing and interaction management are therefore essential for practical quantum chemistry applications [7].

Impact on ADAPT-VQE for Quantum Chemistry

Algorithmic Performance Limitations

The hardware constraints described above directly impact the performance and scalability of ADAPT-VQE algorithms for quantum chemistry research. The algorithm's iterative nature requires numerous measurements and circuit adjustments, making it particularly vulnerable to hardware imperfections [1] [8].

Recent research highlights promising approaches to mitigate these limitations. Scientists at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory have combined double unitary coupled cluster (DUCC) theory with ADAPT-VQE to improve the accuracy of quantum simulations of chemistry without increasing the computational load on the quantum processor [1]. This approach simplifies the construction of Hamiltonian representations, enabling more accurate simulations while working within the constraints of quantum processors with limited qubit counts [1].

Resource Requirements and Error Propagation

The resource overhead for meaningful quantum chemistry calculations remains substantial. Current state-of-the-art approaches still require significant error mitigation and resource optimization to produce chemically accurate results. The table below quantifies key resource requirements and their implications for ADAPT-VQE simulations:

Table 2: Resource Requirements and Implications for ADAPT-VQE Simulations

| Resource Category | Current State | Impact on ADAPT-VQE |

|---|---|---|

| Qubit Count | 100-500 physical qubits in leading systems [6] | Limits active space size for molecular simulations |

| Circuit Depth | 5,000-15,000 quantum gates in near-term roadmaps [5] | Constrains complexity of achievable ansätze |

| Error Correction Overhead | 100-1,000 physical qubits per logical qubit [2] | Limits near-term feasibility of fault-tolerant quantum chemistry |

| Coherence Time | ~0.6 ms for best-performing superconducting qubits [6] | Limits maximum executable circuit depth before decoherence |

For drug discovery researchers, these constraints directly impact the size and complexity of molecules that can be practically simulated. While small molecule simulations are becoming increasingly feasible, simulating biologically relevant systems like protein-ligand interactions or complex enzymatic processes remains beyond current capabilities.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Advanced Error Mitigation Techniques

To address hardware limitations, researchers have developed sophisticated error mitigation protocols specifically tailored for variational quantum algorithms. The following experimental workflow represents current best practices for executing ADAPT-VQE simulations on NISQ hardware:

Key components of this workflow include:

Classical Pre-optimization: Using methods like DUCC (double unitary coupled cluster) to reduce quantum resource requirements by identifying optimal active spaces and effective Hamiltonians before quantum execution [1].

Dynamical Decoupling (DD): Applying sequences of pulses to idle qubits to protect against decoherence, recently demonstrated to provide up to 25% improvement in result accuracy [5].

Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC): Advanced error mitigation that removes bias from noisy quantum circuits but comes with substantial sampling overhead. Recent improvements using samplomatic techniques have decreased this overhead by 100x [5].

Hardware-Aware Algorithm Compilation

Optimizing quantum circuits for specific hardware architectures is essential for maximizing performance. The following protocol details the compilation process:

Topology-Aware Qubit Mapping: Mapping logical qubits from the quantum chemistry problem to physical qubits with the highest connectivity and lowest error rates, particularly important for IBM's square qubit topology in Nighthawk processors [5].

Dynamic Circuit Implementation: Incorporating classical operations mid-circuit using measurement and feedforward, demonstrated to reduce two-qubit gate requirements by 58% while improving accuracy [5].

Gate Decomposition Optimization: Decomposing complex chemical unitary operations into native gate sets with minimal overhead, leveraging tools like Qiskit's Samplomatic package for advanced circuit transformations [5].

Emerging Solutions and Research Directions

Quantum Error Correction Pathways

While current quantum error correction (QEC) demonstrations remain resource-intensive, they provide a crucial pathway toward fault-tolerant quantum chemistry simulations. Google's Willow quantum chip, featuring 105 superconducting qubits, has demonstrated exponential error reduction as qubit counts increase—a critical milestone known as going "below threshold" [6] [2]. This achievement validates that large, error-corrected quantum computers can potentially be constructed to run complex chemistry simulations.

The implementation of the surface code across growing qubit arrays (from 3×3 to 7×7) has shown systematic error suppression, with a 2.14-fold reduction in error rates with each scaling stage [2]. For research chemists, this progress suggests a potential timeline when quantitatively accurate molecular simulations become feasible.

Hybrid Quantum-Classical Architectures

A promising near-term approach involves tighter integration between quantum and classical resources. The sparse wave function circuit solver (SWCS) represents one such innovation, enabling more efficient ADAPT-VQE simulations for larger molecules by offloading computationally intensive work to classical supercomputers [8]. This hybrid approach acknowledges the complementary strengths of both paradigms while mitigating current quantum hardware limitations.

IBM's development of a C++ interface for Qiskit represents another significant advancement, enabling deeper integration with high-performance computing (HPC) systems and allowing quantum-classical workloads to run more efficiently in integrated environments [5].

Control System Innovations

Advanced control systems are addressing the wiring and sorting problems through technological innovations. Companies like Qblox have developed modular control stacks that scale to hundreds of qubits while maintaining low noise and precise control [2]. These systems feature deterministic feedback networks capable of sharing measurement outcomes within ≈400 ns across modules, enabling real-time error correction and active reset capabilities essential for complex algorithms like ADAPT-VQE [2].

The following diagram illustrates the architecture of a modern quantum control system capable of supporting advanced error correction:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For research teams implementing ADAPT-VQE experiments, the following tools and platforms constitute essential components of the experimental workflow:

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for ADAPT-VQE Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Hardware | IBM Heron/IBM Nighthawk [5], Quantinuum H-Series [7], Google Willow [6] | Execution platform for quantum circuits |

| Error Mitigation | Qiskit Samplomatic [5], PEC (Probabilistic Error Cancellation) [5], DUCC Theory [1] | Improving result accuracy despite hardware noise |

| Algorithm Implementation | Qiskit Functions [5], ADAPT-VQE with SWCS [8] | Quantum chemistry algorithm deployment |

| Quantum Control | Qblox Cluster [2], Zurich Instruments QC Stack | Hardware control and measurement |

| Classical Co-Processing | HPC Integration via Qiskit C++ API [5], Sparse Wave Function Circuit Solver [8] | Hybrid quantum-classical computation |

| 6-Hydroxyluteolin | 6-Hydroxyluteolin | Research-grade 6-Hydroxyluteolin, a bioactive flavone with neuroprotective and antioxidant properties. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Isoapetalic acid | Isoapetalic acid, MF:C22H28O6, MW:388.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The quantum hardware roadblock—encompassing wiring challenges, qubit control limitations, and sorting problems—represents a significant but surmountable barrier to practical quantum computational chemistry. For researchers in drug discovery and materials science, current hardware limitations necessitate careful experimental design and sophisticated error mitigation strategies when implementing ADAPT-VQE algorithms.

The rapid progress in quantum error correction, control systems, and hybrid algorithms suggests a promising trajectory toward solving increasingly complex chemical problems. As hardware continues to mature, with error rates decreasing and qubit counts increasing, the practical application of quantum computing to real-world chemistry challenges appears increasingly feasible within a 5-10 year horizon [6]. Research institutions and pharmaceutical companies investing in quantum capabilities today will be well-positioned to leverage these advancements as they emerge, potentially revolutionizing the landscape of computational chemistry and drug discovery.

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a significant advancement in quantum algorithms for the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, offering substantial improvements over traditional VQE methods by systematically constructing problem-specific ansätze [9]. Unlike fixed ansatz approaches such as Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCCSD) or hardware-efficient designs, ADAPT-VQE grows the ansatz iteratively, adding operators one at a time based on their potential to reduce energy [10]. This adaptive construction enables shallower quantum circuits, mitigates optimization challenges like barren plateaus, and maintains high accuracy—theoretically making it an ideal algorithm for current quantum devices [10] [9].

However, this algorithmic superiority comes at a significant cost: dramatically increased quantum measurement overhead. The very adaptive nature that gives ADAPT-VQE its advantages requires extensive quantum measurements for both operator selection and parameter optimization at each iteration [10]. This measurement overhead presents a fundamental bottleneck to practical scaling, as the number of measurements (shots) required grows rapidly with system size. For quantum chemistry applications where exact simulation of strongly correlated systems is the goal, this shot requirement can quickly exceed what is feasible on current quantum hardware, creating what this paper terms the "measurement overhead crisis" [11] [12].

The Technical Roots of the Measurement Crisis

ADAPT-VQE's Twofold Measurement Demands

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm creates measurement overhead through two distinct mechanisms that compound at each iteration. In the operator selection step (Step 1), the algorithm must identify the most promising operator to add to the growing ansatz from a predefined pool of operators [12]. This requires evaluating gradients for every operator in the pool according to the selection criterion:

$$\mathscr{U}^* = \underset{\mathscr{U} \in \mathbb{U}}{\text{argmax}} \left| \frac{d}{d\theta} \Big\langle \Psi^{(m-1)} \left| \mathscr{U}(\theta)^\dagger \widehat{A} \mathscr{U}(\theta) \right| \Psi^{(m-1)} \Big\rangle \Big\vert_{\theta=0} \right|$$

where $\mathbb{U}$ is the operator pool and $\widehat{A}$ is the Hamiltonian [12]. Each gradient evaluation requires substantial quantum measurements, and this process must be repeated for all operators in the pool at every iteration.

In the parameter optimization step (Step 2), after selecting and adding an operator, ADAPT-VQE performs a global optimization overall parameters in the now-expanded ansatz [12]:

$$(\theta1^{(m)}, \ldots, \theta{m-1}^{(m)}, \thetam^{(m)}) := \underset{\theta1, \ldots, \theta{m-1}, \theta{m}}{\operatorname{argmin}} \Big\langle {\Psi}^{(m)} \left| \widehat{A} \right| {\Psi}^{(m)} \Big\rangle$$

This optimization requires numerous evaluations of the Hamiltonian expectation value, each itself composed of many individual measurements of Pauli terms [10]. As the ansatz grows with each iteration, both the measurement costs for operator selection and parameter optimization increase substantially, creating a compounding measurement overhead that limits practical application to larger molecular systems [11].

The Impact of Noise on Measurement Requirements

The challenge of measurement overhead is further exacerbated by hardware noise present in NISQ devices. Statistical noise from finite sampling (shots) introduces inaccuracies in both gradient calculations for operator selection and energy evaluations for parameter optimization [12]. This noise can significantly degrade algorithm performance, as demonstrated in Figure 1 of the GGA-VQE study, where ADAPT-VQE simulations with 10,000 shots per measurement stagnated well above chemical accuracy for Hâ‚‚O and LiH molecules [12]. The presence of noise effectively increases the number of shots required to achieve chemical accuracy, as more samples are needed to average out statistical fluctuations and obtain reliable results for the iterative adaptive process.

Emerging Solutions: Methodologies for Shot Reduction

Pauli Measurement Reuse Strategy

One promising approach to reducing measurement overhead involves reusing Pauli measurement outcomes obtained during VQE parameter optimization in subsequent operator selection steps [11] [10]. The key insight is that the operator selection step requires calculating gradients of the form:

$$\frac{d}{d\theta} \langle \Psi^{(m-1)} | \mathscr{U}(\theta)^\dagger \widehat{A} \mathscr{U}(\theta) | \Psi^{(m-1)} \rangle \Big\vert_{\theta=0}$$

which often involves measuring Pauli strings that have substantial overlap with those in the Hamiltonian itself [10]. By caching and reusing measurement results of these Pauli strings from the VQE optimization (which already required measuring the Hamiltonian terms), the algorithm can avoid redundant measurements in the gradient evaluation for operator selection.

This approach differs fundamentally from previous methods like adaptive informationally complete (IC) generalized measurements [10], as it retains measurements in the standard computational basis rather than requiring specialized POVMs. This makes it more practical for current hardware while still achieving significant shot reduction. Critically, this reuse strategy introduces minimal classical overhead, as the Pauli string analysis can be performed once during initial setup [10].

Variance-Based Shot Allocation

A complementary strategy applies optimal shot allocation techniques based on variance considerations to both Hamiltonian and gradient measurements [11] [10]. Rather than distributing measurement shots uniformly across all Pauli terms—which is statistically suboptimal—variance-based allocation assigns more shots to terms with higher estimated variance and fewer shots to terms with lower variance.

The theoretical foundation for this approach comes from the optimal shot allocation framework [10], which minimizes the total number of shots required to achieve a target precision for a sum of observables. For a Hamiltonian $H = \sumi gi Oi$ composed of Pauli terms $Oi$ with coefficients $gi$, the optimal number of shots for each term is proportional to $|gi|\sqrt{\text{Var}(Oi)}$, where $\text{Var}(Oi)$ is the variance of the observable [10].

This principle can be extended to the gradient measurements required for operator selection in ADAPT-VQE. By grouping commuting terms from both the Hamiltonian and the commutators arising in gradient calculations, and then applying variance-based shot allocation to these groups, the overall measurement cost can be significantly reduced [10]. The grouping can be based on qubit-wise commutativity or more sophisticated commutativity relationships [10].

Integrated Shot-Optimized ADAPT-VQE Protocol

Combining these approaches yields a comprehensive shot-optimized ADAPT-VQE protocol:

- Initialization: Prepare the reference state (typically Hartree-Fock) and define the operator pool [9].

- Iteration Loop:

- Parameter Optimization: Optimize current ansatz parameters using VQE with variance-based shot allocation for Hamiltonian measurement.

- Measurement Caching: Store Pauli measurement results with sufficient statistics for reuse.

- Operator Selection: Evaluate gradients for all pool operators using cached measurements where possible, supplemented with new measurements using variance-based allocation.

- Ansatz Growth: Append the selected operator to the circuit.

- Convergence Check: Repeat until energy convergence or other stopping criteria are met.

This integrated approach addresses both major sources of measurement overhead in ADAPT-VQE while maintaining the algorithm's accuracy and convergence properties.

Quantitative Analysis of Shot Reduction Techniques

Performance of Pauli Measurement Reuse

Experimental results demonstrate significant shot reduction through Pauli measurement reuse and commutativity-based grouping. The following table summarizes the performance gains observed across molecular systems:

Table 1: Shot Reduction via Pauli Measurement Reuse and Grouping

| Strategy | Average Shot Usage | Reduction vs. Naive | Test Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naive full measurement | 100% | Baseline | Hâ‚‚ to BeHâ‚‚ (4-14 qubits), Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„ (16 qubits) |

| QWC grouping only | 38.59% | 61.41% | Hâ‚‚ to BeHâ‚‚ (4-14 qubits), Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„ (16 qubits) |

| Grouping + reuse | 32.29% | 67.71% | Hâ‚‚ to BeHâ‚‚ (4-14 qubits), Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„ (16 qubits) |

The results show that qubit-wise commutativity (QWC) grouping alone reduces shot requirements to 38.59% of naive measurement, while combining grouping with Pauli measurement reuse further reduces usage to 32.29% on average [10]. This represents nearly a 70% reduction in measurement overhead while maintaining chemical accuracy across all tested molecular systems.

Efficacy of Variance-Based Shot Allocation

Variance-based shot allocation techniques show complementary benefits for reducing measurement costs:

Table 2: Shot Reduction via Variance-Based Allocation Methods

| Molecule | Shot Allocation Method | Shot Reduction | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | VMSA (Variance-Minimizing Shot Allocation) | 6.71% | Versus uniform shot distribution |

| Hâ‚‚ | VPSR (Variance-Proportional Shot Reduction) | 43.21% | Versus uniform shot distribution |

| LiH | VMSA | 5.77% | Versus uniform shot distribution |

| LiH | VPSR | 51.23% | Versus uniform shot distribution |

The VPSR method shows particularly strong performance, reducing shot requirements by over 50% for LiH compared to uniform shot distribution [10]. This demonstrates that adaptive, variance-aware shot allocation can dramatically improve measurement efficiency without sacrificing accuracy.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methods for Measurement-Efficient ADAPT-VQE

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Shot-Efficient ADAPT-VQE

| Method/Technique | Function | Key Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Pauli Measurement Reuse | Reduces redundant measurements by caching and reusing Pauli string results | Requires identifying overlap between Hamiltonian terms and gradient commutators; minimal classical overhead |

| Variance-Based Shot Allocation | Optimizes shot distribution across terms to minimize total measurements | Requires variance estimation for observables; compatible with various grouping strategies |

| Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC) Grouping | Groups simultaneously measurable Pauli terms to reduce circuit executions | Straightforward implementation; can be combined with more sophisticated grouping |

| Commutator Grouping [38] | Groups commutators of Hamiltonian terms with pool operators | Creates ~2N or fewer mutually commuting sets; more efficient than naive approaches |

| Gradient Estimation via 3-RDM | Reduces measurement overhead through approximate reconstruction | Can lead to longer ansatz circuits; trades measurement depth for circuit depth |

| Adaptive IC-POVM Measurements | Uses informationally complete measurements for simultaneous cost and gradient estimation | Faces scalability challenges for large systems due to 4^N measurement requirement |

| Benzoctamine | Benzoctamine, CAS:17243-39-9, MF:C18H19N, MW:249.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-(Trimethylsilyl)butanenitrile | 4-(Trimethylsilyl)butanenitrile, CAS:18301-86-5, MF:C7H15NSi, MW:141.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing Shot-Efficient ADAPT-VQE Workflows

Diagram 1: Integrated shot-optimized ADAPT-VQE workflow incorporating both measurement reuse and variance-based allocation strategies at each iterative step.

Diagram 2: Pauli measurement reuse mechanism showing how cached results from Hamiltonian measurements are identified and reused in gradient computations for operator selection.

The measurement overhead crisis represents a fundamental challenge in scaling ADAPT-VQE for practical quantum chemistry applications on NISQ devices. However, integrated strategies combining Pauli measurement reuse and variance-based shot allocation demonstrate that significant reductions in shot requirements—up to 70% in some cases—are achievable while maintaining chemical accuracy [11] [10]. These approaches address both major sources of measurement overhead in ADAPT-VQE: the operator selection step and the parameter optimization step.

Future research directions should focus on developing more sophisticated shot allocation strategies that dynamically adapt to both circuit and noise characteristics, as well as exploring additional measurement reuse opportunities throughout the ADAPT-VQE iterative process. Combining these measurement-efficient strategies with ansatz compactification techniques and error mitigation methods will be essential for bridging the gap between current quantum hardware capabilities and the resource requirements for practical quantum chemistry simulations. As quantum hardware continues to improve, these measurement reduction strategies will play a crucial role in enabling the simulation of increasingly complex molecular systems, ultimately fulfilling the promise of quantum computing for advancing computational chemistry and drug discovery.

Variational Quantum Eigensolvers (VQEs) represent a promising pathway for simulating molecular systems on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. Among these, adaptive algorithms like ADAPT-VQE have emerged as particularly powerful approaches, constructing system-tailored ansätze dynamically rather than relying on predetermined circuit structures [12]. However, as researchers attempt to scale these methods for chemically relevant problems, a fundamental dilemma intensifies: how to balance the expressibility of an ansatz—its ability to represent complex quantum states—against practical constraints on circuit depth and measurement overhead [13]. This balancing act presents significant challenges for researchers aiming to apply quantum computing to drug development and materials science, where simulating molecules of industrially relevant sizes requires navigating the competing demands of accuracy and feasibility.

The ADAPT-VQE framework iteratively constructs ansätze by selecting operators from a predefined pool based on their potential to lower the energy [14]. While this approach generates more compact circuits than fixed ansätze like unitary coupled cluster (UCC), its practical implementation faces multiple bottlenecks. Measurement requirements for operator selection grow substantially with system size, classical optimization becomes increasingly challenging, and hardware noise limits the feasible circuit depth [12] [15]. This technical whitpaper examines the core dilemmas in ansatz construction for scalable quantum chemistry simulations, analyzes recent methodological advances, and provides practical guidance for researchers navigating these trade-offs.

Core Technical Dilemmas in Ansatz Construction

The Expressibility vs. Trainability Trade-off

A fundamental tension exists between designing highly expressive ansätze capable of representing complex molecular wavefunctions and maintaining trainability on current quantum hardware. Expressibility, often quantified through the dimension of the dynamical Lie algebra (DLA), determines which unitaries a quantum neural network (QNN) can represent in the overparameterized regime [13]. However, recent theoretical work has rigorously established that more expressive QNNs require higher measurement costs per parameter for gradient estimation, creating a direct trade-off between expressibility and measurement efficiency [13].

This trade-off manifests practically in ADAPT-VQE implementations through the phenomenon of barren plateaus—regions in the optimization landscape where gradients become exponentially small—and through the computational resources required for parameter optimization. Theoretically, gradient measurement efficiency (({\mathcal{F}}{\rm{eff}})) and expressibility (({\mathcal{X}}{\exp})) are linked by the inequality ({\mathcal{F}}{\rm{eff}} \cdot {\mathcal{X}}{\exp} \leq \alpha \cdot 4^n), where (n) is the number of qubits and (\alpha) is a constant [13]. This mathematical relationship confirms that increasing expressibility necessarily reduces gradient measurement efficiency, forcing algorithm designers to make deliberate choices about ansatz complexity.

Measurement Overhead in Adaptive Algorithms

The adaptive nature of ADAPT-VQE that enables its compact circuit construction simultaneously creates substantial measurement overhead. Each iteration requires evaluating gradients for all operators in the selection pool to identify the most promising candidate, typically requiring tens of thousands of extremely noisy measurements on quantum devices [12]. As system size increases, both the operator pool and the number of iterations grow, creating a scalability barrier.

Table 1: Measurement Overhead Sources in ADAPT-VQE

| Component | Measurement Requirements | Scaling Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Selection | Gradient calculations for entire operator pool | Grows with pool size ((O(N^2n^2)) for UCCSD) |

| Parameter Optimization | Energy evaluations during classical optimization | Increases with ansatz length and parameter count |

| Energy Estimation | Hamiltonian expectation value measurement | Grows with number of Hamiltonian terms |

The impact of this overhead is evident in practical implementations. For example, hardware noise and statistical sampling noise can cause ADAPT-VQE to stagnate well above chemical accuracy thresholds, as demonstrated in simulations of Hâ‚‚O and LiH molecules where results diverged significantly from noiseless simulations [12].

Circuit Depth versus Accuracy Requirements

As ADAPT-VQE iterations progress, circuit depth increases linearly with each added operator. While this gradual construction helps avoid unnecessarily deep circuits, the final depth may still exceed the coherence times of current quantum processors, especially for strongly correlated systems requiring many operators [14]. This creates a fundamental tension between achieving sufficient accuracy (which may require many operators) and maintaining executable circuits (which demands depth constraints).

The circuit depth challenge is particularly acute for chemically inspired ansätze like UCC, where direct encoding of fermionic excitations produces "deep circuits with a large number of two-qubit gates" [14]. Even adaptive approaches face this issue, as each added operator increases both circuit depth and the number of variational parameters to be optimized [12].

Emerging Solutions and Methodological Advances

Gradient-Free and Quantum-Aware Optimization

Recent advances in optimization techniques specifically designed for variational quantum algorithms offer promising pathways to reduce measurement requirements and improve convergence. The ExcitationSolve algorithm exemplifies this trend, extending Rotosolve-type optimizers to handle excitation operators whose generators satisfy (Gj^3 = Gj) rather than the simpler (G_j^2 = I) condition [16]. This quantum-aware approach leverages the analytical form of the energy landscape—a second-order Fourier series—to perform global optimization along each parameter direction using only five energy evaluations per parameter [16].

Table 2: Comparison of Optimization Approaches for VQE

| Optimizer | Key Mechanism | Resource Requirements | Compatible Ansätze |

|---|---|---|---|

| ExcitationSolve | Analytical energy landscape reconstruction | 5 energy evaluations per parameter | UCC, ADAPT-VQE, other excitation-based ansätze |

| Rotosolve | Closed-form minimization for parameterized gates | 3 energy evaluations per parameter | Pauli rotation gates ((G^2 = I)) |

| GGA-VQE | Greedy gradient-free adaptive optimization | Reduced sensitivity to statistical noise | General adaptive ansätze |

| BFGS/COBYLA | Black-box numerical optimization | High number of energy evaluations | General parameterized circuits |

Similarly, the Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE) demonstrates improved resilience to statistical sampling noise by eliminating the need for precise gradient calculations during operator selection [12]. This approach has been successfully demonstrated on a 25-qubit error-mitigated quantum processing unit for computing the ground state of a 25-body Ising model [12].

Ansatz Compaction and Pruning Strategies

Rather than solely focusing on construction methods, researchers have developed complementary approaches to identify and remove redundant operators from adaptive ansätze. The Pruned-ADAPT-VQE method automatically eliminates operators with negligible contributions by evaluating both amplitude magnitude and positional significance within the ansatz [14]. This approach identifies three primary mechanisms generating superfluous operators: (1) poor operator selection, (2) operator reordering effects, and (3) fading operators whose contributions diminish during optimization [14].

In practice, Pruned-ADAPT-VQE applies a dynamic threshold based on recent operator amplitudes to remove unnecessary operators without disrupting convergence. Application to molecular systems like stretched Hâ‚„ has demonstrated significant reductions in ansatz size while maintaining accuracy, particularly in cases with flat energy landscapes where redundant operators commonly accumulate [14].

Measurement Efficiency Improvements

Reducing the quantum measurement overhead represents another active area of innovation. Two complementary strategies show particular promise:

Shot-optimized ADAPT-VQE integrates measurement reuse and variance-aware allocation [10]. By reusing Pauli measurement outcomes from VQE parameter optimization in subsequent gradient calculations, and applying variance-based shot allocation to both Hamiltonian and gradient measurements, this approach reduces average shot usage to approximately 32% of naive measurement schemes [10].

The Stabilizer-Logical Product Ansatz (SLPA) represents a more fundamental redesign, exploiting symmetric circuit structures to enhance gradient measurement efficiency [13]. This approach reaches the theoretical upper bound of the trade-off between gradient measurement efficiency and expressibility, enabling gradient estimation with the fewest measurement types for a given expressivity level [13].

Alternative Construction Approaches

Beyond improving standard ADAPT-VQE, researchers have developed alternative ansatz construction paradigms that fundamentally reconsider the balance between expressibility and efficiency. Genetic algorithm-based approaches automatically evolve circuit designs through iterative mutation and selection, prioritizing both expressibility and shallow depth [17]. This method generates circuits that achieve high expressibility metrics while maintaining trainability, performing competitively with ADAPT-VQE and UCCSD on molecular systems like Hâ‚‚, LiH, BeHâ‚‚, and Hâ‚‚O [17].

Batched ADAPT-VQE addresses measurement overhead by adding multiple operators with the largest gradients simultaneously rather than one per iteration [18]. This strategy significantly reduces the number of gradient computation cycles while maintaining ansatz compactness, though it may slightly increase circuit depth per iteration [18].

The FAST-VQE algorithm represents another scalable approach, maintaining a constant circuit count regardless of system size unlike ADAPT-VQE's steeply increasing requirements [15]. Implemented on 50-qubit quantum hardware, FAST-VQE has demonstrated the ability to handle active spaces that challenge classical computational methods, though classical optimization emerges as the primary bottleneck at this scale [15].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Guidelines

Practical Implementation Considerations

Implementing adaptive VQE algorithms for meaningful quantum chemistry calculations requires careful attention to several practical aspects:

Operator Pool Design: The choice of operator pool significantly influences algorithm performance. Fermionic ADAPT-VQE uses UCCSD-type pools scaling as (O(N^2n^2)), while qubit ADAPT-VQE employs Pauli string pools [18]. For tapered qubit spaces after symmetry reduction, complete pools with linear scaling in system size can be automatically constructed, though overly aggressive pool reduction may increase measurement requirements [18].

Classical Optimization Strategy: As system scale increases, classical optimization becomes the dominant bottleneck. On 50-qubit demonstrations, greedy optimization strategies that adjust one parameter at a time allowed 120 iterations per hardware slot compared to just 30 for full-parameter methods [15]. This approach delivered energy improvements of approximately 30 kcal/mol over all-parameter optimization [15].

Hardware-Aware Execution: Real hardware implementations must account for noise characteristics and connectivity constraints. For example, in a 25-qubit Ising model demonstration on error-mitigated hardware, the parameterized circuit calculated on quantum hardware was subsequently evaluated via noiseless emulation to obtain accurate energies, demonstrating a pragmatic hybrid approach [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Components

Table 3: Key Experimental Components for ADAPT-VQE Research

| Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pools | Define candidate operators for ansatz construction | UCCSD pool (fermionic), Pauli strings (qubit), chemically-inspired pools |

| Gradient Estimators | Evaluate operator importance for selection | Exact gradient measurements, approximate classical estimators, commutator-based approaches |

| Quantum-Aware Optimizers | Efficient parameter tuning | ExcitationSolve, Rotosolve, GGA-VQE, gradient-free optimizers |

| Measurement Strategies | Reduce quantum resource requirements | Variance-based allocation, Pauli reuse, qubit-wise commutativity grouping |

| Pruning Mechanisms | Eliminate redundant operators | Amplitude-threshold approaches, positional significance evaluation |

| Ophiobolin C | Ophiobolin C, MF:C25H38O3, MW:386.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hexahydro-1-lauroyl-1H-azepine | Hexahydro-1-lauroyl-1H-azepine, CAS:18494-60-5, MF:C18H35NO, MW:281.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The development of effective ansatz construction strategies remains a central challenge in scaling quantum chemistry simulations on near-term quantum hardware. The fundamental dilemma between expressibility and circuit depth manifests through multiple technical dimensions: measurement overhead, optimization difficulty, and hardware limitations. While no single approach has fully resolved these tensions, the emerging toolkit of gradient-free optimizers, compaction strategies, and measurement-efficient implementations provides promising pathways forward.

For researchers targeting drug development applications, hybrid strategies that combine the physical intuition of chemically inspired ansätze with hardware-aware implementation are likely to yield the most practical near-term results. The Pruned-ADAPT-VQE approach offers a balanced solution for maintaining compact circuits, while ExcitationSolve and related quantum-aware optimizers address the challenging parameter optimization problem. As hardware continues to improve, with demonstrations now reaching 50-qubit scales [15], the emphasis is shifting from pure quantum resource constraints to classical-quantum co-design challenges.

The future of quantum chemistry simulations will likely involve problem-tailored ansätze rather than universal approaches, where understanding molecular symmetries and physical constraints informs circuit design. By strategically limiting expressibility to physically relevant subspaces, researchers can achieve the measurement efficiencies needed for practical applications while maintaining sufficient accuracy for predictive simulations. As the field progresses, the delicate balance between expressibility and efficiency will continue to shape algorithm development, determining how quickly quantum computing can impact real-world chemical discovery and drug development.

The Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era is defined by quantum processors containing up to a few thousand qubits that operate without full fault tolerance, making them inherently susceptible to environmental noise, gate errors, and decoherence [19]. For quantum chemistry research, which holds the promise of revolutionizing drug development and materials science, the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithmic approach. However, practical implementations face significant challenges, particularly with adaptive variants like ADAPT-VQE, where noise fundamentally limits scalability and accuracy [19] [20]. This technical guide examines the impact of noise on algorithmic performance, focusing on the specific challenges in scaling ADAPT-VQE for quantum chemistry applications. It further explores emerging error mitigation and algorithmic strategies designed to extract chemically meaningful results from current-generation quantum hardware, providing researchers with a roadmap for navigating the constraints of the NISQ landscape.

The NISQ Landscape and Fundamental Noise Challenges

Characteristics of NISQ Hardware

NISQ computing is characterized by quantum processors containing up to 1,000 qubits which are not yet advanced enough for fault-tolerance or large enough to achieve unambiguous quantum advantage [19]. These devices are sensitive to their environment, prone to quantum decoherence, and incapable of continuous quantum error correction. Current NISQ devices typically contain between 50 and 1,000 physical qubits, with leading systems from IBM, Google, and other companies continually pushing these boundaries [19]. The fundamental challenge lies in the exponential scaling of quantum noise, where error rates above 0.1% per gate limit quantum circuits to approximately 1,000 gates before noise overwhelms the signal [19].

Table 1: Primary Noise Sources in NISQ Devices and Their Impact on Algorithms

| Noise Source | Physical Origin | Impact on Quantum Algorithms |

|---|---|---|

| Decoherence | Qubit interaction with environment | Loss of quantum superposition and entanglement, limiting computation time |

| Gate Errors | Imperfect control pulses | Accumulation of operational errors, particularly in multi-qubit gates |

| Measurement Errors | Qubit state misidentification | Inaccurate readout of computational results |

| Crosstalk | Inter-qubit interference | Unintended operations on neighboring qubits |

Hardware Performance Specifications

Gate fidelities in current NISQ devices hover around 99-99.5% for single-qubit operations and 95–99% for two-qubit gates [19]. While impressive, these figures still introduce significant errors in circuits with thousands of operations. The limited coherence times of qubits mean that quantum computations must be executed rapidly, restricting both the depth and complexity of executable algorithms [21]. These constraints severely limit the practical implementation of quantum algorithms for drug development applications, where accurate simulation of molecular systems requires substantial quantum resources.

Algorithmic Frameworks: ADAPT-VQE and Its Limitations

Core Methodology of ADAPT-VQE

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm represents a significant advancement over fixed-ansatz approaches for quantum chemistry simulations. Its iterative process systematically constructs problem-specific ansätze by appending unitary operators selected from a predefined pool based on gradient criteria [20] [12]. At iteration m, given a parameterized ansatz wavefunction |Ψ^(m-1)⟩, the algorithm identifies the optimal unitary operator Ʋ* from pool 𕌠that satisfies:

Ʋ* = argmax{Ʋ∈ð•Œ} |d/dθ ⟨Ψ^(m-1)|Ʋ(θ)†ĤƲ(θ)|Ψ^(m-1)⟩|{θ=0}

This results in a new ansatz |Ψ^(m)⟩ = Ʋ*(θ_m)|Ψ^(m-1)⟩, after which a classical optimizer performs a global optimization over all parameters [12]. This adaptive approach has demonstrated significant reductions in redundant terms in ansatz circuits for various molecules, enhancing both accuracy and efficiency compared to fixed-ansatz methods [12].

Specific Noise-Induced Challenges in Scaling ADAPT-VQE

The practical implementation of ADAPT-VQE on NISQ hardware encounters multiple noise-induced bottlenecks that limit its application to chemically relevant systems for drug development:

Measurement Overhead: The operator selection procedure requires computing gradients of the Hamiltonian expectation value for every operator in the pool, typically requiring tens of thousands of extremely noisy measurements on quantum devices [12]. This overhead grows polynomially with system size, creating a fundamental scalability barrier.

Optimization Challenges: The classical optimization of a high-dimensional, noisy cost function often becomes computationally intractable, with algorithms stagnating well above chemical accuracy thresholds due to measurement noise [12]. For larger active spaces, classical optimization of operator parameters emerges as the primary bottleneck rather than quantum execution itself [15].

Circuit Depth Limitations: Practical implementations of ADAPT-VQE are sensitive to local energy minima, leading to over-parameterized ansätze [20]. For strongly correlated systems like stretched H₆ linear chains, achieving chemical accuracy can require more than a thousand CNOT gates [20], far exceeding the capabilities of current NISQ devices where state-of-the-art simulations typically involve maximal circuit depths of less than 100 CNOT gates [20].

Barren Plateaus: The optimization landscape suffers from the barren plateau phenomenon, where gradients vanish exponentially with problem size, making parameter optimization increasingly difficult [22].

Diagram 1: ADAPT-VQE workflow with noise impacts

Advanced Methodologies and Error Mitigation Strategies

Algorithmic Improvements for Noise Resilience

Recent research has produced several adaptive variants of VQE that address specific noise limitations:

Overlap-ADAPT-VQE: This approach grows wave-functions by maximizing their overlap with intermediate target wave-functions that capture electronic correlation, avoiding construction in the energy landscape strewn with local minima [20]. This method produces ultra-compact ansätze suitable for high-accuracy initialization, achieving substantial savings in circuit depth—particularly valuable for strongly correlated systems where standard ADAPT-VQE struggles [20].

Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE): This algorithm utilizes analytic, gradient-free optimization to improve resilience to statistical sampling noise [12]. By eliminating the need for noisy gradient measurements during operator selection, GGA-VQE reduces measurement overhead while maintaining performance for simple molecular ground states.

FAST-VQE: Designed specifically for scalability, FAST-VQE maintains a constant circuit count as systems grow, unlike ADAPT-VQE which requires a steep increase in circuits [15]. Its hybrid approach performs adaptive operator selection on the quantum device while handling energy estimation via classical approximation, enabling exploration of problems that neither side could handle alone [15].

Experimental Error Mitigation Protocols

Since NISQ devices lack full quantum error correction, error mitigation techniques become essential for extracting meaningful results:

Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE): This widely used technique artificially amplifies circuit noise and extrapolates results to the zero-noise limit [19]. The method assumes errors scale predictably with noise levels, allowing researchers to fit polynomial or exponential functions to noisy data to infer noise-free results. Recent implementations of purity-assisted ZNE have shown improved performance by incorporating additional information about quantum state degradation [19].

Symmetry Verification: This technique exploits conservation laws inherent in quantum systems to detect and correct errors [19]. For quantum chemistry calculations, symmetries such as particle number conservation or spin conservation provide powerful error detection mechanisms. When measurement results violate these symmetries, they can be discarded or corrected through post-selection.

Probabilistic Error Cancellation: This approach reconstructs ideal quantum operations as linear combinations of noisy operations that can be implemented on hardware [19]. While theoretically capable of achieving zero bias, the sampling overhead typically scales exponentially with error rates, limiting practical applications to relatively low-noise scenarios.

Machine Learning-Assisted Mitigation: Supervised machine learning on intermediate parameter and measurement data can predict optimal final parameters, requiring significantly fewer iterations while simultaneously showing resilience to coherent errors when trained on noisy devices [22].

Table 2: Error Mitigation Techniques and Their Performance Characteristics

| Technique | Methodology | Overhead | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation | Artificial noise amplification and extrapolation | Moderate (2-5x circuit evaluations) | General optimization problems |

| Symmetry Verification | Post-selection based on conserved quantities | Variable (depends on error rate) | Quantum chemistry simulations |

| Probabilistic Error Cancellation | Linear combination of noisy operations | High (exponential in error rate) | Low-noise scenarios |

| Measurement Error Mitigation | Calibration and statistical correction | Low (single calibration) | All measurement-intensive tasks |

| Machine Learning Mitigation | Training on noisy device data | High initial training cost | Repetitive calculations on same hardware |

Experimental Protocols for Noise Characterization

Implementing effective error mitigation requires rigorous noise characterization protocols:

Protocol 1: Measurement Error Calibration

- Prepare each computational basis state |i⟩ individually.

- Perform measurement and record outcome statistics.

- Construct a calibration matrix M where M_ji = P(measure j | prepared i).

- Apply the inverse of M to subsequent experimental data to correct readout errors.

Protocol 2: Zero-Noise Extrapolation Implementation

- Execute the target quantum circuit at multiple increased noise levels (e.g., 1x, 2x, 3x base noise).

- Increase noise levels by stretching pulse durations or inserting identity operations.

- Measure observables of interest at each noise level.

- Fit extrapolation function (linear, exponential, or Richardson) to the data.

- Extract zero-noise estimate from the fitted function.

Diagram 2: Zero-noise extrapolation protocol

Performance Benchmarks and Scaling Data

Quantitative Performance Comparisons

Recent experimental studies provide critical data on algorithmic performance under NISQ constraints:

Resource Requirements: For the BeHâ‚‚ molecule at equilibrium distance, ADAPT-VQE achieves accuracy of ~2×10â»â¸ Hartree using approximately 2,400 CNOT gates, significantly more efficient than the k-UpCCGSD algorithm which requires more than 7,000 CNOT gates for lower accuracy (10â»â¶ Hartree) [20].

Scaling Limitations: Implementation of FAST-VQE on 50-qubit IQM Emerald hardware for butyronitrile dissociation revealed that classical optimization of operator parameters became the primary bottleneck at scale [15]. A greedy optimization strategy adjusting one parameter at a time allowed 120 iterations in a daily hardware slot compared to just 30 for the full-parameter method, delivering an energy improvement of ~30 kcal/mol [15].

Noise Resilience: Machine learning-assisted parameter optimization demonstrated the ability to achieve chemical accuracy for H₂, H₃, and HeH+ molecules with significantly fewer iterations while compensating for coherent noise on real IBM superconducting devices [22].

Table 3: Algorithm Performance Comparison on Quantum Hardware

| Algorithm | System Tested | Qubit Count | Circuit Depth (CNOT count) | Accuracy Achieved | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADAPT-VQE | BeHâ‚‚ (equilibrium) | 6-8 | ~2,400 | 2×10â»â¸ Hartree | Measurement overhead |

| ADAPT-VQE | Stretched H₆ | 12 | >1,000 | Chemical accuracy | Depth exceeds NISQ limits |

| Overlap-ADAPT-VQE | Stretched H₆ | 12 | Significantly reduced | Chemical accuracy | Requires target wavefunction |

| FAST-VQE | Butyronitrile | 50 | Constant scaling | ~30 kcal/mol improvement | Classical optimization bottleneck |

| GGA-VQE | 25-body Ising | 25 | N/A | Favorable approximation | Hardware noise affects energy accuracy |

Hardware-Specific Performance Data

Experimental results from real quantum processing units highlight the current state of algorithmic performance:

25-Qubit Implementation: Execution of GGA-VQE on a 25-qubit error-mitigated QPU for a 25-body Ising model demonstrated that while hardware noise produced inaccurate energies, the implementation successfully output parameterized quantum circuits yielding favorable ground-state approximations [12].

50-Qubit Scaling: On IQM Emerald's 50-qubit processor, Kvantify's FAST-VQE algorithm demonstrated measurable benefits compared to random baselines, with quantum hardware achieving faster convergence despite noise and deep circuits [15]. This shows that current devices can capture structure and patterns that randomness cannot, though noise impedes optimal operator selection in larger circuits at later stages.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Chemistry Experiments

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Hardware Platforms | IBM Quantum, IQM Resonance, Ion-trap systems | Provide physical qubit implementations for algorithm execution |

| Software Frameworks | Qiskit, PennyLane, Cirq, OpenFermion | Quantum circuit design, simulation, and execution management |

| Classical Optimizers | COBYLA, L-BFGS-B, Genetic Algorithms | Hybrid classical parameter optimization with noise resilience |

| Error Mitigation Tools | M3, ZNE, PEC, Symmetry Verification | Reduce noise impact without full quantum error correction |

| Chemistry-Specific Modules | PySCF, OpenFermion-PySCF, QChem | Molecular Hamiltonian generation and integral computation |

| Operator Pools | Qubit-Excitation-Based (QEB), Fermionic excitations | Predefined operator sets for adaptive ansatz construction |

| Measurement Tools | Quantum volume, Gate fidelity benchmarks, Process tomography | Hardware performance characterization and validation |

The NISQ era presents a complex landscape for quantum chemistry research, where noise fundamentally constrains algorithmic performance, particularly for adaptive approaches like ADAPT-VQE. While significant challenges remain in measurement overhead, optimization under noise, and circuit depth limitations, ongoing advancements in error mitigation, algorithmic innovation, and hardware development provide a promising path forward. The transition from small-scale proof-of-concept studies to chemically relevant simulations on 50+ qubit devices demonstrates tangible progress, though classical optimization bottlenecks now emerge as the next frontier. For researchers in drug development and materials science, a careful integration of problem-specific algorithms, robust error mitigation, and hardware-aware design will be essential to extract meaningful chemical insights from current-generation quantum processors as we advance toward fault-tolerant quantum computation.

Methodological Breakthroughs: Novel Architectures and Algorithms for Scalable ADAPT-VQE

Adaptive variational quantum algorithms, particularly the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE), represent a promising pathway toward quantum advantage in computational chemistry in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era [23]. Unlike fixed-structure ansätze such as Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC), ADAPT-VQE iteratively constructs a problem-tailored ansatz by dynamically appending parameterized unitaries selected from an operator pool based on their estimated gradient contribution to the energy [23] [12]. This adaptive nature has demonstrated remarkable improvements in circuit efficiency, accuracy, and trainability compared to static ansätze [23].

However, scaling ADAPT-VQE to larger, chemically relevant systems presents significant challenges. The most critical bottleneck is the high quantum measurement (shot) overhead required for both the operator selection and parameter optimization steps [12] [10]. Furthermore, the ansatz circuit depth and the number of entangling gates (CNOTs) can grow substantially, making the algorithm susceptible to decoherence and gate errors on current hardware [23]. The choice of the operator pool—the set of generators from which the ansatz is built—is a fundamental factor influencing all these resource requirements. Early ADAPT-VQE implementations used fermionic pools of generalized single and double (GSD) excitations, which can lead to deep circuits and high measurement costs [23]. The development of more sophisticated, compact operator pools is therefore a crucial research frontier for making ADAPT-VQE practical.

Coupled Exchange Operators (CEO): A Novel Pool Design

The Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool is a novel ansatz construction strategy designed to dramatically reduce the quantum resource requirements of ADAPT-VQE [23] [24]. It moves beyond traditional fermionic excitation operators to a qubit-efficient formulation.

Theoretical Foundation and Design Principles

The CEO pool is inspired by the structure of qubit excitations. The design focuses on creating a minimal yet expressive set of operators that efficiently capture the essential physics of electron correlation, particularly the coupled dynamics of electron pairs [23]. By moving to a qubit-based representation, the CEO pool generates more compact quantum circuits compared to fermionic pools. The operators are constructed to preserve relevant physical symmetries, which helps in maintaining the physicality of the wavefunction throughout the optimization process and can improve convergence [23]. The pool is designed to be complete, meaning it can, in principle, converge to the full configuration interaction (FCI) solution, while simultaneously minimizing the number of operators required per iteration [23].

Comparative Analysis of Operator Pools

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the CEO pool compared to other commonly used pools in ADAPT-VQE.

Table 1: Comparison of ADAPT-VQE Operator Pools

| Operator Pool | Operator Type | Key Features | Known Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fermionic (GSD) [23] | Generalized Single & Double Excitations | Chemistry-inspired; Fermionic operators. | Can lead to deep circuits with high CNOT counts. |

| Qubit (Pauli Strings) [24] | Pauli string generators | Hardware-friendly; Qubit representation. | May require more iterations to converge. |

| QEB [24] | Qubit Excitation-Based | A middle ground between fermionic and qubit pools. | Balanced performance. |

| CEO (This work) [23] | Coupled Exchange Operators | Compact; Qubit-efficient; Designed for reduced gate count. | Dramatic reduction in CNOT count, depth, and measurement costs. |

Experimental Validation and Performance Benchmarks

Quantitative Resource Reduction

The performance of CEO-ADAPT-VQE was rigorously tested on molecules such as LiH, H6, and BeH2, represented by 12 to 14 qubits [23]. The results demonstrate a dramatic reduction in key quantum resource metrics compared to the original fermionic (GSD-based) ADAPT-VQE.

Table 2: Resource Reduction of CEO-ADAPT-VQE vs. Fermionic ADAPT-VQE (at chemical accuracy) [23]

| Molecule (Qubits) | CNOT Count Reduction | CNOT Depth Reduction | Measurement Cost Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| LiH (12) | Up to 88% | Up to 96% | Up to 99.6% |

| H6 (12) | Up to 88% | Up to 96% | Up to 99.6% |

| BeH2 (14) | Up to 88% | Up to 96% | Up to 99.6% |

Beyond these direct comparisons, CEO-ADAPT-VQE also outperforms the standard unitary coupled cluster singles and doubles (UCCSD) ansatz, a widely used static VQE ansatz, in all relevant metrics [23]. Notably, it offers a five-order-of-magnitude decrease in measurement costs compared to other static ansätze with similar CNOT counts [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

To replicate the benchmark results for CEO-ADAPT-VQE, the following methodology can be employed.

- Step 1: Molecular System Setup. Select a benchmark molecule (e.g., LiH, BeH2). Define the molecular geometry (bond lengths and angles) and choose a basis set (e.g., STO-3G, 6-31G). The Hamiltonian is then generated in the second quantization formalism under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation [10].

- Step 2: Qubit Hamiltonian Generation. The fermionic Hamiltonian is mapped to a qubit Hamiltonian using a transformation such as the Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation [23].

- Step 3: Algorithm Initialization. Prepare the initial reference state, typically the Hartree-Fock state. Initialize the ansatz circuit as empty. Define the CEO operator pool as detailed in the original literature [23].

- Step 4: ADAPT-VQE Iteration Loop. The core adaptive loop proceeds as follows [23] [12]:

- Gradient Evaluation: For each operator in the CEO pool, compute the energy gradient. This involves measuring the expectation value of the commutator

[H, A_i]on the current quantum state, whereHis the Hamiltonian andA_iis the pool operator. - Operator Selection: Identify the operator with the largest gradient magnitude.

- Ansatz Appending: Append the corresponding parameterized unitary,

exp(θ_i * A_i), to the quantum circuit. - Parameter Optimization: Execute a classical optimization routine (e.g., BFGS, L-BFGS-B, gradient descent) to minimize the energy expectation value with respect to all parameters in the current ansatz. This requires repeated energy evaluations on the quantum processor or simulator.

- Gradient Evaluation: For each operator in the CEO pool, compute the energy gradient. This involves measuring the expectation value of the commutator

- Step 5: Convergence Check. The algorithm terminates when the norm of the gradient vector falls below a predefined threshold (e.g., 10â»Â³ a.u.), indicating that a variational minimum has been reached, or when chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa or 1 kcal/mol) is achieved [23].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this iterative protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing and experimenting with CEO-ADAPT-VQE requires a combination of classical and quantum software tools, as well as an understanding of key algorithmic components.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for CEO-ADAPT-VQE Implementation

| Tool / Component | Category | Function and Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| CEO Operator Pool | Algorithmic Component | The pre-defined set of coupled exchange operators that serve as generators for the adaptive ansatz. Its compact nature is the source of resource reduction [23]. |

| Quantum Circuit Simulator | Software Tool | High-performance classical emulators (e.g., MPS-based simulators) are essential for algorithm development, debugging, and small-scale benchmarking before running on quantum hardware [25]. |

| Measurement Optimization | Algorithmic Subroutine | Techniques like reused Pauli measurements and variance-based shot allocation are critical for reducing the immense shot overhead of ADAPT-VQE, making CEO-ADAPT-VQE more practical [10]. |

| Classical Optimizer | Software Tool | A robust classical optimization library (e.g., SciPy) is needed to solve the nonlinear parameter optimization problem in the VQE loop. The choice of optimizer impacts convergence [12]. |

| Quantum Hardware/API | Hardware/Platform | Access to a quantum processing unit (QPU) or its API (e.g., via cloud services) is required for final experimental validation and scaling studies [15]. |

| DIETHYL(TRIMETHYLSILYLMETHYL)MALONATE | DIETHYL(TRIMETHYLSILYLMETHYL)MALONATE, CAS:17962-38-8, MF:C11H22O4Si, MW:246.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Nitroxazepine hydrochloride | Sintamil (Nitroxazepine) | Sintamil (Nitroxazepine) is a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) used to treat depression and nocturnal enuresis. For prescription use only. Not for personal or research use. |

Integration with Broader Algorithmic Advancements

The CEO pool is not a standalone solution but is most powerful when combined with other recent advances in measurement and algorithmic design. Two key synergistic strategies are:

- Reused Pauli Measurements: This strategy reduces shot overhead by recycling measurement outcomes obtained during the VQE parameter optimization for the gradient evaluation in the subsequent operator selection step [10]. This avoids redundant measurements of the same Pauli strings.

- Variance-Based Shot Allocation: This technique optimizes the distribution of a finite shot budget by allocating more shots to Hamiltonian terms (or gradient observables) with higher estimated variance, thereby maximizing the accuracy of the energy (or gradient) estimation for a given number of total shots [10].

The integration of these methods with the CEO pool creates a state-of-the-art variant, termed CEO-ADAPT-VQE*, which combines frugal measurement costs with shallow, compact ansätze [23]. The following diagram illustrates this powerful synergy.

The introduction of the Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool marks a significant leap forward in the quest to scale ADAPT-VQE for practical quantum chemistry applications. By fundamentally redesigning the operator pool to be more qubit-efficient and compact, it directly addresses the critical bottlenecks of circuit depth and measurement cost that have hindered the algorithm's application to larger molecules. The demonstrated reductions in CNOT counts and measurement overhead by up to 88% and 99.6%, respectively, are not merely incremental improvements but represent a transformative change in resource requirements [23]. When integrated with other advanced techniques like measurement reuse and optimized shot allocation, the CEO pool forms the core of a next-generation adaptive algorithm [23] [10]. This paves the way for more accurate and scalable quantum simulations of molecular systems on both near-term and future quantum hardware, bringing the field closer to demonstrating a true quantum advantage in computational chemistry and drug development.

The pursuit of quantum utility in computational chemistry is fundamentally linked to the development of efficient, scalable wavefunction ansätze. The Unitary Coupled Cluster with Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) ansatz, while a cornerstone of quantum computational chemistry, faces significant practical limitations on current noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) hardware due to its considerable circuit depth and parameter count [26] [23]. These limitations are particularly acute within the context of the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) framework, where the iterative construction of ansätze promises enhanced efficiency but introduces substantial quantum measurement overhead and optimization challenges [12] [23].

This technical guide examines advanced ansatz strategies that move beyond UCCSD to create system-tailored wavefunctions, specifically addressing the critical challenges in scaling ADAPT-VQE for quantum chemistry research. As highlighted in recent research, "the large number of measurements associated with VQEs" constitutes a primary concern for practical implementations [23]. The following sections provide a comprehensive analysis of emerging approaches, their experimental validation, and resource requirements, equipping researchers with the methodologies needed to advance quantum chemistry simulations on near-term hardware.

Beyond UCCSD: Next-Generation Ansatz Paradigms

Adaptive Ansatz Construction: ADAPT-VQE and Its Evolution

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm represents a fundamental shift from fixed-ansatz approaches like UCCSD toward dynamically constructed, system-specific wavefunctions. Unlike fixed ansätze that are "by definition system-agnostic" and often "contain superfluous operators," ADAPT-VQE iteratively builds an ansatz by selecting operators from a predefined pool based on their potential to reduce energy [12]. Each iteration consists of two critical steps: (1) identifying the most promising operator from a pool by computing energy derivatives (gradients), and (2) globally optimizing all parameters in the newly expanded ansatz [12].

Recent advancements have dramatically improved ADAPT-VQE's practicality. As shown in Table 1, modern implementations have reduced quantum resource requirements by up to 99.6% compared to early versions [23]. These improvements stem from innovations in operator pools, measurement strategies, and optimization techniques, which collectively address the primary bottlenecks in scaling ADAPT-VQE for complex chemical systems.

Table 1: Evolution of ADAPT-VQE Resource Requirements for Selected Molecules

| Molecule | Qubits | Algorithm Version | CNOT Count | CNOT Depth | Measurement Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH | 12 | Original ADAPT-VQE | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| LiH | 12 | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | Reduced by 88% | Reduced by 96% | Reduced by 99.6% |

| H6 | 12 | Original ADAPT-VQE | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| H6 | 12 | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | Reduced by 73% | Reduced by 92% | Reduced by 98% |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | Original ADAPT-VQE | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | Reduced by 83% | Reduced by 96% | Reduced by 99.4% |

The Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) Pool

The introduction of the Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool represents a significant advancement in ADAPT-VQE efficiency. This novel operator pool leverages coupled cluster-type operators specifically designed for hardware efficiency, dramatically reducing both circuit depth and measurement requirements [23]. The CEO pool operates on the principle of exchanging excitations between coupled qubits or orbitals, capturing essential correlation effects with minimal quantum gates.

Numerical simulations demonstrate that CEO-ADAPT-VQE* "outperforms the Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles ansatz, the most widely used static VQE ansatz, in all relevant metrics" [23]. Specifically, it offers "a five order of magnitude decrease in measurement costs as compared to other static ansätze with competitive CNOT counts" [23], making it particularly suitable for scaling to larger molecular systems where measurement overhead constitutes a critical bottleneck.

Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunctions

The hybrid quantum-neural approach represents a paradigm shift in wavefunction representation, combining the strengths of parameterized quantum circuits and neural networks. The pUNN (paired Unitary Coupled-Cluster with Neural Networks) method employs "a combination of an efficient quantum circuit and a neural network" to achieve near-chemical accuracy in molecular energy calculations [26]. In this framework, the quantum circuit learns the quantum phase structure of the target state—a challenging task for neural networks alone—while the neural network accurately describes the amplitude [26].

This division of labor creates a synergistic effect: the quantum circuit component (pUCCD) maintains low qubit count (N qubits) and shallow circuit depth, while the neural network accounts for contributions from unpaired configurations outside the seniority-zero subspace [26]. The method has been experimentally validated on superconducting quantum hardware for the isomerization reaction of cyclobutadiene, demonstrating "high accuracy and significant resilience to noise" [26], a critical advantage for NISQ-era implementations.

Unitary Cluster Jastrow (uCJ) Ansätze

The k-fold Unitary Cluster Jastrow (uCJ) ansätze offer an alternative pathway to resource efficiency by building wavefunctions from simpler one-body terms rather than the two-body operators characteristic of UCCSD [27]. These ansätze provide O(kN²) circuit scaling and favorable linear depth circuit implementation, significantly reducing gate counts compared to UCCSD [27].

Recent extensions to the uCJ framework include Im-uCJ and g-uCJ variants, which incorporate imaginary and fully complex orbital rotation operators, respectively [27]. These variants demonstrate enhanced expressibility and accuracy compared to the original real-orbital-rotation (Re-uCJ) version, frequently maintaining "energy errors within chemical accuracy (∼1 kcal molâ»Â¹)" [27]. Importantly, both Im-uCJ and g-uCJ circuits can be implemented exactly without Trotter decomposition, preserving their suitability for near-term hardware.

Algorithmic Cooling-Inspired Ansätze

Inspired by algorithmic cooling principles, the Heat Exchange (HE) ansatz facilitates efficient population redistribution without requiring bath resets, simplifying implementation on NISQ devices [28]. This approach leverages structured quantum operations to drive entropy transfer within the system, creating a novel ansatz design strategy for variational algorithms. When applied to impurity systems and the MaxCut problem, the HE ansatz has demonstrated "superior approximation ratios" compared to conventional hardware-efficient and QAOA ansätze [28], highlighting its potential for addressing challenging quantum many-body problems.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CEO-ADAPT-VQE Implementation Protocol

Implementing the CEO-ADAPT-VQE algorithm requires careful attention to both quantum circuit design and classical optimization components. The following protocol outlines the key steps for molecular ground state energy calculation:

Molecular System Specification: Define the molecular system, including atomic coordinates, basis set, and active space selection. For benchmarking purposes, start with small molecules like LiH or Hâ‚‚O before progressing to larger systems.

Hamiltonian Preparation: Generate the electronic Hamiltonian in second quantization using classical electronic structure packages. Apply fermion-to-qubit transformation (Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev) to obtain the qubit Hamiltonian.

CEO Pool Initialization: Construct the coupled exchange operator pool containing parameterized unitary operators generated from coupled cluster-type operators optimized for hardware efficiency.

ADAPT-VQE Iteration Loop: