Overcoming the Quantum Measurement Bottleneck: Strategies for Hybrid Algorithms in Drug Discovery

Hybrid quantum-classical algorithms represent a promising path to practical quantum advantage in drug discovery, but their performance is often constrained by a critical quantum measurement bottleneck.

Overcoming the Quantum Measurement Bottleneck: Strategies for Hybrid Algorithms in Drug Discovery

Abstract

Hybrid quantum-classical algorithms represent a promising path to practical quantum advantage in drug discovery, but their performance is often constrained by a critical quantum measurement bottleneck. This article explores the foundational causes of this bottleneck, rooted in the probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics and the need for repeated circuit executions. It details current methodological approaches for mitigation, including advanced error correction and circuit compilation techniques. The content further provides a troubleshooting and optimization framework for researchers, and presents a validation landscape comparing the performance of various strategies. By synthesizing insights from recent breakthroughs and industry applications, this article equips scientific professionals with a comprehensive roadmap for integrating quantum intelligence into pharmaceutical R&D while navigating current hardware limitations.

The Quantum Bottleneck: Defining the Fundamental Challenge in Hybrid Algorithms

The quantum measurement bottleneck represents a fundamental constraint in harnessing the computational power of near-term quantum devices. This whitepaper examines the theoretical underpinnings and practical manifestations of this bottleneck within hybrid quantum-classical algorithms, particularly focusing on implications for drug discovery and quantum chemistry. We analyze how the exponential scaling of required measurements impacts computational feasibility and review emerging mitigation strategies including symmetry exploitation, Bayesian inference, and advanced measurement protocols. Through detailed experimental methodologies and quantitative analysis, we demonstrate that overcoming this bottleneck is essential for achieving practical quantum advantage in real-world applications such as clinical trial optimization and molecular simulation.

In quantum computing, the measurement bottleneck arises from the fundamental nature of quantum mechanics, where extracting classical information from quantum states requires repeated measurements of observables. Unlike classical bits that can be read directly, quantum states collapse upon measurement, yielding probabilistic outcomes. Each observable typically requires a distinct measurement basis and circuit configuration, creating a fundamental scaling challenge [1]. For hybrid quantum-classical algorithms, which combine quantum and classical processing, this bottleneck manifests as a critical runtime constraint that often negates potential quantum advantages.

The severity of this bottleneck becomes apparent in practical applications such as drug discovery, where quantum computers promise to revolutionize molecular modeling and predictive analytics [2]. In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, devices suffer from gate errors, decoherence, and imprecise readouts that further exacerbate measurement challenges [3]. As quantum circuits become deeper to accommodate more complex computations, the cumulative noise often overwhelms the signal, requiring even more measurements for statistically significant results. This creates a vicious cycle where the measurement overhead grows exponentially with system size, potentially rendering quantum approaches less efficient than classical alternatives for practical problem sizes.

Theoretical Foundations and Scaling Challenges

Fundamental Scaling Laws

The quantum measurement bottleneck originates from the statistical nature of quantum measurement. To estimate the expectation value of an observable with precision ε, the number of required measurements scales as O(1/ε²) for a single observable. However, for molecular systems and quantum chemistry applications, the Hamiltonian often comprises a sum of numerous Pauli terms. The standard quantum computing approach requires measuring each term separately, and the number of these terms grows polynomially with system size [2] [4].

For a system with N qubits, the number of terms in typical electronic structure Hamiltonians scales as O(Nâ´), creating an overwhelming measurement burden for practical applications [2]. This scaling presents a fundamental barrier to quantum advantage in hybrid algorithms for drug discovery, where accurate energy calculations are essential for predicting molecular interactions and reaction pathways.

Table 1: Measurement Scaling in Quantum Chemical Calculations

| System Size (Qubits) | Hamiltonian Terms | Standard Measurements | Optimized Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | ~50-100 | ~10â´-10âµ | ~10³ |

| 10 | ~500-2000 | ~10âµ-10ⶠ| ~10â´ |

| 20 | ~10â´-10âµ | ~10â¶-10â· | ~10âµ |

| 50 | ~10â¶-10â· | ~10â¸-10â¹ | ~10â· |

Impact on Hybrid Algorithm Performance

Hybrid quantum-classical algorithms, particularly the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Machine Learning (QML) models, are severely impacted by the measurement bottleneck. In these iterative algorithms, the quantum processor computes expectation values that a classical optimizer uses to update parameters [2] [3]. Each iteration requires fresh measurements, and the convergence may require hundreds or thousands of iterations.

The combined effect of numerous Hamiltonian terms and iterative optimization creates a multiplicative measurement overhead that often dominates the total computational time. For drug discovery applications involving molecules like β-lapachone prodrug activation or KRAS protein interactions, this bottleneck can render quantum approaches impractical despite their theoretical potential [2]. Furthermore, the presence of hardware noise necessitates additional measurements for error mitigation, further exacerbating the problem.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Measurement Approaches

Traditional quantum measurement protocols for electronic structure calculations employ one of several strategies: (1) Direct measurement of each Pauli term in the Hamiltonian requires O(Nâ´) distinct measurement settings, each implemented with unique circuit configurations [1]. (2) Grouping techniques attempt to measure commuting operators simultaneously, reducing the number of distinct measurements by approximately a constant factor, though the scaling remains polynomial. (3) Random sampling methods select subsets of terms for measurement, introducing additional statistical uncertainty.

The standard experimental workflow begins with Hamiltonian construction from molecular data, followed by qubit mapping using transformations such as Jordan-Wigner or parity encoding. For each measurement setting, researchers prepare the quantum state through parameterized circuits, execute the measurement operation, and collect statistical samples. This process repeats for all measurement settings, after which classical post-processing aggregates the results to compute molecular properties such as ground state energy or reaction barriers [2].

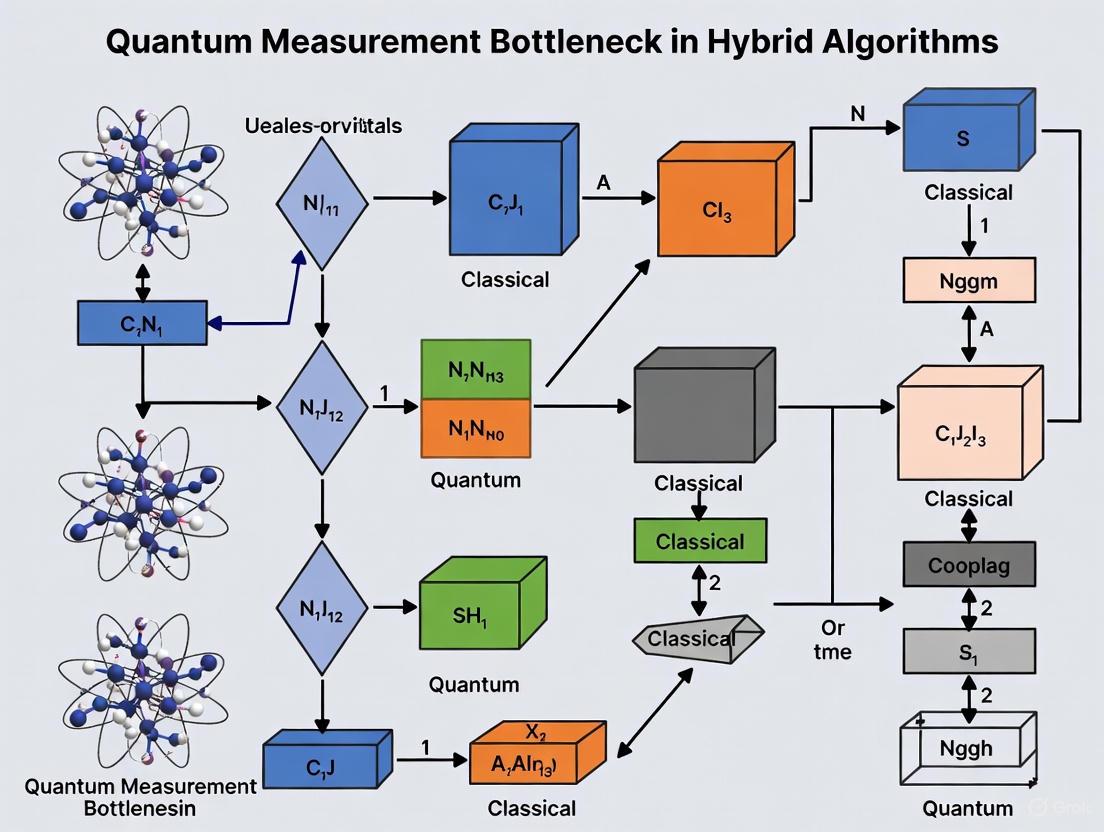

Figure 1: Standard Quantum Measurement Workflow for Molecular Systems

Advanced Measurement Reduction Protocol

Recent research has demonstrated that exploiting symmetries in target systems can dramatically reduce measurement requirements. For crystalline materials with high symmetry, a novel protocol requires only three fixed measurement settings to determine electronic band structure, regardless of system size [1]. This approach was validated on a two-dimensional CuOâ‚‚ square lattice (3 qubits) and bilayer graphene (4 qubits) using the Variational Quantum Deflation (VQD) algorithm.

The experimental methodology follows this sequence:

- Symmetry Analysis: Identify the symmetry group of the target Hamiltonian, focusing on crystalline materials with translational invariance.

- Measurement Derivation: Construct a minimal set of measurement settings that comprehensively captures all symmetry-distinct matrix elements.

- Circuit Implementation: Design quantum circuits that implement these fixed measurement settings, typically requiring simple basis rotations.

- Data Collection: Execute each measurement setting repeatedly to gather sufficient statistical samples.

- Reconstruction: Use symmetry relations to reconstruct full Hamiltonian expectation values from the limited measurement data.

This protocol reduces the scaling of measurements from O(Nâ´) to a constant value, representing a potential breakthrough for quantum simulations of materials [1].

Case Studies in Drug Discovery and Quantum Chemistry

Quantum Computing in Prodrug Activation Studies

In pharmaceutical research, a hybrid quantum computing pipeline was developed to study prodrug activation involving carbon-carbon bond cleavage in β-lapachone, a natural product with anticancer activity [2]. Researchers employed the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) with a hardware-efficient ansatz to compute Gibbs free energy profiles for the bond cleavage process.

The experimental protocol involved:

- Active Space Selection: Reducing the quantum chemistry problem to a manageable two electron/two orbital system representable by 2 qubits

- Ansatz Design: Implementing a hardware-efficient R𑦠ansatz with a single layer as the parameterized quantum circuit for VQE

- Error Mitigation: Applying standard readout error mitigation to enhance measurement accuracy

- Solvation Effects: Incorporating water solvation effects using the ddCOSMO model with 6-311G(d,p) basis set

This approach demonstrated the viability of quantum computations for simulating covalent bond cleavage, achieving results consistent with classical computational methods like Hartree-Fock (HF) and Complete Active Space Configuration Interaction (CASCI) [2].

Clinical Trial Optimization

Quantum computing shows promise for optimizing clinical trials, which frequently face delays due to poor site selection strategies and incorrect patient identification [5]. Quantum machine learning and optimization approaches can transform key steps in clinical trial simulation, site selection, and cohort identification strategies.

Hybrid algorithms leverage quantum processing for specific challenging subproblems while maintaining classical control over the overall optimization process. This approach mitigates the measurement bottleneck by focusing quantum resources only on tasks where they provide maximum benefit, such as:

- Generating complex trial simulations that capture patient heterogeneity

- Optimizing site selection across multiple geographic and demographic constraints

- Identifying patient cohorts with optimal response characteristics while minimizing recruitment challenges

Table 2: Quantum Approaches to Clinical Trial Challenges

| Clinical Trial Challenge | Classical Approach | Quantum-Enhanced Approach | Measurement Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site Selection | Statistical modeling | Quantum optimization | Quadratic unconstrained binary optimization (QUBO) formulations |

| Cohort Identification | Machine learning | Quantum kernel methods | Quantum feature mapping with repeated measurements |

| Trial Simulation | Monte Carlo methods | Quantum amplitude estimation | Reduced measurement needs through quantum speedup |

| Biomarker Discovery | Pattern recognition | Quantum neural networks | Variational circuits with measurement optimization |

Emerging Solutions and Mitigation Strategies

Algorithmic Approaches

Several algorithmic strategies have emerged to address the quantum measurement bottleneck:

Bayesian Inference: A quantum-assisted Monte Carlo method incorporates Bayesian inference to dramatically reduce the number of quantum measurements required [4]. Instead of taking simple empirical averages of quantum measurements, this approach continually updates a probability distribution for the quantity of interest, refining the estimate with each new data point. This strategy achieves desired bias reduction with significantly fewer quantum samples than traditional methods.

Quantum-Assisted Monte Carlo: This approach uses a small quantum processor to boost the accuracy of classical simulations, addressing the notorious sign problem in quantum Monte Carlo calculations [4]. By incorporating quantum data into the Monte Carlo sampling process, the algorithm sharply reduces the bias and error that plague fully classical methods. The quantum computer serves as a co-processor for specific tasks, requiring only relatively small numbers of qubits and gate operations to gain quantum advantage.

Measurement Symmetry Exploitation: As demonstrated in the fixed-measurement protocol for crystalline materials, identifying and leveraging symmetries in the target system can dramatically reduce measurement requirements [1]. This approach changes the scaling relationship from polynomial in system size to constant for sufficiently symmetric systems.

Hardware and Architectural Innovations

Beyond algorithmic improvements, hardware and architectural developments show promise for mitigating the measurement bottleneck:

Qudit-Based Processing: Research from NTT Corporation has proposed using high-dimensional "quantum dits" (qudits) instead of conventional two-level quantum bits [6]. For photonic quantum information processing, this approach enables implementation of fusion gates with significantly higher success rates than the theoretical limit for qubit-based systems. This indirectly addresses measurement challenges by improving the quality of quantum states before measurement occurs.

Machine Learning Decoders: For quantum error correction, recurrent transformer-based neural networks can learn to decode error syndromes more accurately than human-designed algorithms [7]. By learning directly from data, these decoders can adapt to complex noise patterns including cross-talk and leakage, improving the reliability of each measurement and reducing the need for repetition due to errors.

Dynamic Circuit Capabilities: Advanced quantum processors increasingly support dynamic circuits that enable mid-circuit measurements and feed-forward operations. These capabilities allow for more efficient measurement strategies that adapt based on previous results, potentially reducing the total number of required measurements.

Figure 2: Solutions for the Quantum Measurement Bottleneck

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Quantum Measurement Optimization

| Tool/Technique | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | Hybrid algorithm for quantum chemistry | Molecular energy calculations in drug design [2] |

| Quantum-Assisted Monte Carlo | Reduces sign problem in fermionic simulations | Molecular property prediction with reduced bias [4] |

| Symmetry-Adapted Measurement Protocol | Minimizes measurement settings via symmetry | Crystalline materials simulation [1] |

| Bayesian Amplitude Estimation | Reduces quantum measurements via inference | Efficient expectation value estimation [4] |

| Transformer-Based Neural Decoders | Improves error correction accuracy | Syndrome processing in fault-tolerant schemes [7] |

| Qudit-Based Fusion Gates | Increases quantum operation success rates | Photonic quantum processing [6] |

| TenCirChem Package | Python library for quantum computational chemistry | Implementing quantum chemistry workflows [2] |

| Feruloylputrescine | Feruloylputrescine, CAS:501-13-3, MF:C14H20N2O3, MW:264.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lactobionic Acid | Lactobionic Acid Reagent|C12H22O12|96-82-2 | High-purity Lactobionic Acid for research. Explore applications in biochemistry, cell culture, and preservative science. For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

The quantum measurement bottleneck represents a critical challenge that must be addressed to realize the potential of quantum computing in practical applications like drug discovery and clinical trial optimization. While theoretical scaling laws present formidable barriers, emerging strategies including symmetry exploitation, Bayesian methods, and novel hardware approaches show significant promise for mitigating these limitations. The progression from theoretical models to tangible applications in pharmaceutical research demonstrates that hybrid quantum-classical algorithms can deliver value despite current constraints. As research continues to develop more efficient measurement protocols and error-resilient approaches, the quantum measurement bottleneck may gradually transform from a fundamental limitation to an engineering challenge, ultimately enabling quantum advantage in real-world drug design workflows.

In the rapidly evolving field of quantum computing, hybrid quantum-classical algorithms have emerged as a promising approach for leveraging current-generation noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) hardware. These algorithms, including the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA), distribute computational workloads between quantum and classical processors. However, their practical implementation faces a fundamental constraint: the quantum measurement bottleneck. This bottleneck arises from the statistical nature of quantum mechanics, where extracting meaningful information from quantum states requires repeated, destructive measurements to estimate expectation values with sufficient precision.

The core challenge is that the number of measurements required for accurate results scales polynomially with system size and inversely with the desired precision. For complex problems in fields such as quantum chemistry and drug discovery, this creates a significant scalability barrier. As researchers attempt to solve larger, more realistic problems, the measurement overhead dominates computational time and costs, potentially negating the quantum advantage offered by these hybrid approaches. This technical guide examines the origins, implications, and emerging solutions to this critical bottleneck within the broader context of hybrid algorithms research.

The Fundamental Scaling Challenge of Quantum Measurements

Statistical Nature of Quantum Measurements

In quantum computing, the process of measurement fundamentally differs from classical computation. While classical bits can be read without disturbance, quantum bits (qubits) exist in superpositions of states |0⟩ and |1⟩. When measured, a qubit's wavefunction collapses to a definite state, yielding a probabilistic outcome. This intrinsic probabilistic nature means that determining the expectation value of a quantum operator requires numerous repetitions of the same quantum circuit to build statistically significant estimates.

For a quantum circuit preparing state |ψ(θ)⟩ and an observable O, the expectation value ⟨O⟩ = ⟨ψ(θ)|O|ψ(θ)⟩ is estimated by running the circuit multiple times and averaging the measurement outcomes. The statistical error in this estimate decreases with the square root of the number of measurements (N), following the standard deviation of a binomial distribution. Consequently, achieving higher precision requires disproportionately more measurements—to halve the error, one must quadruple the measurement count.

Quantitative Scaling Relationships

The following table summarizes key scaling relationships that define the quantum measurement bottleneck in hybrid algorithms:

Table 1: Scaling Relationships in Quantum Measurement Bottlenecks

| Factor | Scaling Relationship | Impact on Measurements |

|---|---|---|

| Precision (ε) | N ∠1/ε² | 10x precision increase requires 100x more measurements |

| System Size (Qubits) | N ∠poly(n) for n-qubit systems | Measurement count grows polynomially with problem size |

| Observable Terms | N ∠M² for M Pauli terms in Hamiltonian | Measurements scale quadratically with Hamiltonian complexity |

| Algorithm Depth | N ∠D for D circuit depth | Deeper circuits may require more measurement shots per run |

For complex problems such as molecular energy calculations in drug discovery, the number of measurement terms can grow exponentially with system size. For instance, calculating the ground state energy of the [4Fe-4S] molecular cluster—an important component in biological systems like the nitrogenase enzyme—requires handling Hamiltonians with an enormous number of terms [8]. Classical heuristics have traditionally been used to approximate which components of the Hamiltonian matrix are most important, but these approximations can lack rigor and reliability.

Experimental Evidence and Case Studies

Quantum-Centric Supercomputing for Chemical Systems

Recent research from Caltech, IBM, and RIKEN demonstrates both the challenges and potential solutions to the measurement bottleneck. In their groundbreaking work published in Science Advances, the team employed a hybrid approach to study the [4Fe-4S] molecular cluster using up to 77 qubits on an IBM quantum device powered by a Heron quantum processor [8].

The experimental protocol followed these key steps:

- Quantum Pre-processing: The quantum computer identified the most important components in the Hamiltonian matrix, replacing classical heuristics with a more rigorous quantum-based selection

- Measurement and Data Extraction: Repeated measurements were performed on the quantum processor to identify critical matrix elements

- Classical Post-processing: The reduced Hamiltonian was fed to RIKEN's Fugaku supercomputer to solve for the exact wave function

This quantum-centric supercomputing approach demonstrated that quantum computers could effectively prune down the exponentially large Hamiltonian matrices to more manageable subsets. However, the requirement for extensive measurements to achieve chemical accuracy remained a significant computational cost factor.

Measurement-Induced Scaling in Quantum Dynamics

Cutting-edge research from June 2025 provides crucial insights into how measurement strategies fundamentally impact quantum information lifetime. The study "Scaling Laws of Quantum Information Lifetime in Monitored Quantum Dynamics" established that continuous monitoring of quantum systems via mid-circuit measurements can extend quantum information lifetime exponentially with system size [9].

The key experimental findings from this research include:

Table 2: Scaling Laws of Quantum Information Lifetime Under Different Measurement Regimes

| Measurement Regime | Scaling with System Size | Scaling with Bath Size | Practical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Monitoring with Mid-circuit Measurements | Exponential improvement | Independent of bath size | Enables scalable quantum algorithms with longer coherence |

| No Bath Monitoring | Linear improvement at best | Decays inversely with bath size | Severely limits scalability of hybrid algorithms |

| Traditional Measurement Approaches | Constant or linear scaling | Significant degradation with larger baths | Creates fundamental bottleneck for practical applications |

The researchers confirmed these scaling relationships through numerical simulations in both Haar-random and chaotic Hamiltonian systems. Their work suggests that strategic measurement protocols could potentially overcome the traditional bottlenecks in hybrid quantum algorithms.

Methodologies for Mitigating Measurement Overhead

Advanced Measurement Strategies

Several innovative measurement strategies have emerged to address the scalability challenges:

1. Operator Grouping and Commutation Techniques

- Identify sets of commuting operators that can be measured simultaneously

- Implement efficient measurement circuits that maximize information per shot

- Use graph coloring algorithms to minimize the number of distinct measurement bases

2. Adaptive Measurement Protocols

- Employ Bayesian and machine learning approaches to prioritize measurements based on expected information gain

- Dynamically allocate measurement shots across different operators based on variance estimates

- Implement iterative refinement of expectation values

3. Shadow Tomography and Classical Shadows

- Use randomized measurements to construct classical representations of quantum states

- Enable estimation of multiple observables from a single set of measurements

- Provide provable guarantees on measurement complexity for certain classes of observables

Quantum Error Correction and Mitigation

Error mitigation techniques play a crucial role in reducing the effective measurement overhead:

1. Zero-Noise Extrapolation

- Run circuits at different noise levels

- Extrapolate to the zero-noise limit to estimate ideal results

- Requires additional measurements at scaled error rates

2. Probabilistic Error Cancellation

- Characterize noise models of quantum device

- Apply quasi-probability distributions to mitigate errors in post-processing

- Increases measurement overhead but improves result accuracy

3. Measurement Error Mitigation

- Construct measurement confusion matrices

- Invert the confusion matrix to correct readout errors

- Requires additional calibration measurements but improves data quality

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Measurement Challenges

| Category | Specific Tool/Technique | Function/Purpose | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Hardware | Mid-circuit measurement capability | Enables strategic monitoring without full circuit repetition | IBM Heron processor, Quantinuum H2 system [8] [10] |

| Classical Integration | Hybrid quantum-classical platforms | Manages measurement distribution and classical post-processing | NVIDIA CUDA-Q, IBM Qiskit Runtime [10] [11] |

| Error Mitigation | Quantum error correction decoders | Reduces measurement noise through real-time correction | GPU-based decoders, Surface codes [10] [12] |

| Algorithmic Frameworks | Variational Quantum Algorithms | Optimizes parameterized quantum circuits with minimal measurements | VQE, QAOA, QCNN [13] [14] |

| Computational Resources | High-performance classical computing | Handles measurement data processing and Hamiltonian analysis | Fugaku supercomputer, NVIDIA Grace Hopper systems [8] [11] |

Visualization of Measurement Workflows and Scaling Relationships

Quantum Measurement Bottleneck in Hybrid Algorithms

Impact of Strategic Monitoring on Quantum Information Lifetime

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The measurement bottleneck represents both a challenge and an opportunity for innovation in hybrid quantum algorithms. Several promising research directions are emerging:

1. Measurement-Efficient Algorithm Design Developing algorithms that specifically minimize measurement overhead through clever mathematical structures, such as the use of shallow circuits, measurement recycling, and advanced observable grouping techniques.

2. Co-Design of Hardware and Algorithms Creating quantum processors with specialized measurement capabilities, such as parallel readout, mid-circuit measurements, and dynamic qubit reset, which can significantly reduce the temporal overhead of repeated measurements.

3. Machine Learning for Measurement Optimization Leveraging classical machine learning, particularly deep neural networks, to predict optimal measurement strategies and reduce the number of required shots through intelligent shot allocation [14].

4. Quantum Memory and Error Correction Advances Implementing quantum error correction codes that protect against measurement errors, enabling more reliable results from fewer shots. Recent collaborations, such as that between Quantinuum and NVIDIA, have demonstrated improved logical fidelity through GPU-based decoders integrated directly with quantum control systems [10].

As quantum hardware continues to improve, with companies like Quantinuum promising systems that are "a trillion times more powerful" than current generation processors [10], the relative impact of the measurement bottleneck may shift. However, fundamental quantum mechanics ensures that measurement efficiency will remain a critical consideration in hybrid algorithm design for the foreseeable future.

The international research community's focus on this challenge—evidenced by major investments from governments and private industry—suggests that innovative solutions will continue to emerge, potentially unlocking the full potential of quantum computing for practical applications in drug discovery, materials science, and optimization.

The advent of hybrid quantum-classical algorithms promises to revolutionize computational fields, particularly drug discovery, by leveraging quantum mechanical principles to solve problems intractable for classical computers. However, the potential of these algorithms is severely constrained by a fundamental quantum measurement bottleneck, where the statistical uncertainty inherent in quantum sampling leads to prolonged mixing times for classical optimizers. This whitepaper examines this bottleneck through the lens of quantum information theory, providing a technical guide to its manifestations in real-world applications like molecular energy calculations and protein-ligand interaction studies. We summarize quantitative performance data across hardware platforms, detail experimental protocols for benchmarking, and propose pathways toward mitigating these critical inefficiencies. As hybrid algorithms form the backbone of near-term quantum applications in pharmaceutical research, addressing this bottleneck is paramount for achieving practical quantum advantage.

Hybrid quantum-classical algorithms, such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA), represent the leading paradigm for leveraging current noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. These algorithms delegate a specific, quantum-native sub-task—often the preparation and measurement of a parameterized quantum state—to a quantum processor, while a classical optimizer adjusts the parameters to minimize a cost function [15] [16]. This framework is particularly relevant for drug discovery, where the cost function could be the ground state energy of a molecule, a critical factor in predicting drug-target interactions [2] [17].

The central challenge, which we term the quantum measurement bottleneck, arises from the fundamental nature of quantum mechanics. The output of a quantum circuit is a statistical sample from the measurement of a quantum state. To estimate an expectation value, such as the molecular energy ⟨H⟩, one must repeatedly prepare and measure the quantum state, with the precision of the estimate scaling as 1/√N, where N is the number of measurement shots or samples [15]. This statistical noise propagates into the cost function, creating a noisy landscape for the classical optimizer.

This noise directly impacts the mixing time of the optimization process—the number of iterations required for the classical algorithm to converge to a solution of a desired quality. High-precision energy estimations require an impractically large number of shots, while fewer shots inject noise that slows, and can even prevent, convergence [18]. This creates a critical trade-off between computational resource expenditure (quantum sampling time) and algorithmic efficiency (classical mixing time). For pharmaceutical researchers, this bottleneck manifests directly in prolonged wait times for reliable results in tasks like Gibbs free energy profiling for prodrug activation or covalent inhibitor simulation [2], ultimately limiting the integration of quantum computing into real-world drug design workflows.

Quantitative Analysis of Bottlenecks and Performance

The quantum measurement bottleneck and its impact on mixing times can be quantitatively analyzed across several dimensions, including the resources required for sampling and the resulting solution quality. The following tables consolidate key metrics from recent experimental studies and algorithmic demonstrations.

Table 1: Quantum Resource Requirements for Selected Algorithms and Applications

| Algorithm / Application | Problem Size | Quantum Resources Required | Key Metric & Impact on Mixing Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Picasso Algorithm (Quantum Data Prep) [19] | 2 million Pauli strings (∼50x previous tools) | Graph coloring & clique partitioning on HPC; reduces data for quantum processing. | 85% reduction in Pauli strings. Cuts classical pre-processing, indirectly improving total workflow mixing time. |

| VQE for Prodrug Activation [2] | 2 electrons, 2 orbitals (active space) | 2-qubit superconducting device; hardware-efficient $R_y$ ansatz; readout error mitigation. | Reduced active space enables fewer shots; error mitigation improves quality per shot, directly reducing noise and optimizer iterations. |

| Multilevel QAOA for QUBO [18] | Sherrington-Kirkpatrick graphs up to ~27k nodes | Rigetti Ankaa-2 (82 qubits); TB-QAOA depth p=1; up to 600k samples/sub-problem. | High sample count per sub-problem (~10 sec QPU time x 20-60 sub-problems) necessary to achieve >95% approximation ratio, indicating severe sampling bottleneck. |

| BF-DCQO for HUBO [18] | Problems up to 156 qubits | IBM 156-qubit device; non-variational algorithm. | Sub-quadratic gate scaling and decreasing gates/iteration reduces noise per shot, enabling shorter mixing times and a claimed ≥10x speedup. |

Table 2: Benchmarking Solution Quality and Convergence

| Study Focus | Reported Solution Quality | Classical Baseline Comparison | Implication for Mixing Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Picasso Algorithm [19] | Solved problem with 2M Pauli strings in 15 minutes. | Outperformed tools limited to tens of thousands of Pauli strings. | Dramatically reduced pre-processing time for quantum input, a major bottleneck in hybrid workflows. |

| Gate-Model Optimization [18] | >99.5% approximation ratio for spin-glass problems. | Compared to D-Wave annealers (1,500x improvement); but vs. simple classical heuristics. | High quality per iteration suggests efficient mixing, but wall-clock time was high (~20 min), potentially due to sampling overhead. |

| Multilevel QAOA [18] | >95% approximation ratio after ~3 NDAR iterations. | Quality was competitive with the classical analog of the same algorithm. | Similar quality to classical analog suggests quantum sampling did not introduce detrimental noise, allowing for comparable mixing times. |

| Trapped-Ion Optimization [18] | Poor average approximation ratio (< 10^-3) after 40 iterations. |

Compared only to vanilla QAOA, not state-of-the-art classical solvers. | Suggests failure to converge (very long mixing time) due to noise or insufficient shots, highlighting the sensitivity of optimizers to the measurement bottleneck. |

Experimental Protocols for Bottleneck Characterization

To systematically characterize the measurement bottleneck and its link to mixing times, researchers must adopt rigorous experimental protocols. The following methodologies are essential for benchmarking and advancing hybrid quantum-classical algorithms.

Protocol 1: VQE for Molecular Energy Estimation

This protocol is foundational for quantum chemistry problems in drug discovery, such as calculating Gibbs free energy profiles for drug candidates [2].

Problem Formulation:

- Molecular System: Select a target molecule (e.g., a segment of $\beta$-lapachone for prodrug activation studies).

- Active Space Approximation: Reduce the full molecular Hamiltonian to a manageable size by selecting a active space of frontier electrons and orbitals (e.g., 2 electrons in 2 orbitals).

- Qubit Hamiltonian: Map the fermionic Hamiltonian to a qubit Hamiltonian using a transformation such as Jordan-Wigner or parity.

Algorithm Implementation:

- Ansatz Selection: Choose a parameterized quantum circuit, such as a hardware-efficient $R_y$ ansatz with entangling gates, suitable for NISQ devices.

- Measurement: Define the set of observables (Pauli strings) to be measured. The number of unique terms directly impacts the total shot requirement.

Parameter Optimization Loop:

- The classical optimizer (e.g., COBYLA, SPSA) proposes parameters $\theta$.

- The quantum computer prepares the state $|\psi(\theta)\rangle$ and collects $N$ measurement shots for each observable.

- The energy expectation $\langle H \rangle$ is estimated statistically from the samples.

- The optimizer receives the noisy energy estimate and calculates new parameters.

Bottleneck Analysis Metrics:

- Convergence Profile: Track the estimated energy vs. optimizer iteration for different fixed values of $N$.

- Shot-VS-Accuracy: For a converged state, analyze the error in the final energy estimate as a function of the total number of shots used.

- Wall-clock Time Decomposition: Report the total time, breaking down QPU sampling time, classical processing time, and queueing/compilation time [18].

Protocol 2: QAOA for Combinatorial Optimization

This protocol is relevant for problems like protein-ligand docking or clinical trial optimization framed as combinatorial searches [17] [15].

Problem Encoding:

- QUBO Formulation: Define the problem of interest (e.g., Max-Cut) as a Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) problem.

- Hamiltonian Mapping: Encode the QUBO into a problem Hamiltonian $H_C$.

Algorithm Execution:

- Circuit Depth: Implement a QAOA circuit with depth $p$, alternating between cost ($HC$) and mixer ($HB$) unitaries.

- Sampling Strategy: Execute the final circuit and collect $N$ samples from the output distribution.

Classical Optimization:

- The classical optimizer adjusts the $2p$ parameters ($\gamma$, $\beta$) to minimize the expectation value $\langle H_C \rangle$.

- The quality of the solution is often measured by the approximation ratio.

Bottleneck Analysis Metrics:

- Approximation Ratio vs. Iterations: Plot the best-found approximation ratio as a function of the number of optimizer iterations for different shot counts $N$ [18].

- Success Probability: Measure the likelihood of the algorithm returning the exact optimal solution in a single run, which is highly sensitive to shot noise.

- Comparison to Classical Analog: Replace the quantum sampling step with a classical probabilistic sampler (e.g., simulated annealing) within the same hybrid framework. This isolates the quantum hardware's contribution and tests if it provides a speedup or quality improvement [18].

Visualizing Workflows and Bottlenecks

The following diagrams, defined in the DOT language, illustrate the core hybrid algorithm workflow and the specific point where the measurement bottleneck occurs.

Diagram 1: Core hybrid algorithm feedback loop. The bottleneck arises when statistical noise from quantum measurement samples propagates into the cost function evaluation, leading the classical optimizer to require more iterations (longer mixing time) to converge.

Diagram 2: Quantum measurement and estimation process. The fundamental uncertainty (ε/√N) in the final expectation value is the source of noise that creates the optimization bottleneck.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Beyond abstract algorithms, practical research in this domain relies on a suite of specialized "reagents" – computational tools, hardware platforms, and software packages.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Quantum Hybrid Algorithm Development

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Research | Relevance to Bottleneck |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Space Approximation [2] | Computational Method | Reduces the effective problem size of a chemical system to a manageable number of electrons and orbitals. | Directly reduces the number of qubits and circuit complexity, mitigating noise and the number of observables to measure. |

| Error Mitigation (e.g., Readout) [2] | Quantum Software Technique | Post-processes raw measurement data to correct for predictable device errors. | Improves the quality of information extracted per shot, effectively reducing the shot burden for a target precision. |

| Variational Quantum Circuit (VQC) [20] | Algorithmic Core | The parameterized quantum circuit that prepares the trial state; the quantum analog of a neural network layer. | Its depth and structure determine the quantum resource requirements and susceptibility to noise, influencing optimizer performance. |

| Graph Coloring / Clique Partitioning [19] | Classical Pre-Processing Algorithm | Groups commuting Pauli terms in a Hamiltonian to minimize the number of distinct quantum measurements required. | Directly reduces the multiplicative constant in the total shot budget, a critical optimization for reducing runtime. |

| TenCirChem Package [2] | Software Library | A Python library for quantum computational chemistry that implements VQE workflows. | Provides a standardized environment for benchmarking algorithms and studying the measurement bottleneck across different molecules. |

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz [2] | Circuit Design Strategy | Constructs parameterized circuits using native gates of a specific quantum processor to minimize circuit depth. | Reduces exposure to decoherence and gate errors, leading to cleaner signals and less noise in the measurement outcomes. |

| 3-Decyl-5,5'-diphenyl-2-thioxo-4-imidazolidinone | 3-Decyl-5,5'-diphenyl-2-thioxo-4-imidazolidinone, CAS:875014-22-5, MF:C25H32N2OS, MW:408.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 7-Hydroxyguanine | 7-Hydroxyguanine, CAS:16870-91-0, MF:C5H5N5O2, MW:167.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, quantum hardware is characterized by a precarious balance between growing qubit counts and persistent, significant noise. Current devices typically feature between 50 to 1000+ physical qubits but remain hampered by high error rates, short coherence times, and limited qubit connectivity [21]. These hardware realities fundamentally constrain the computational potential of near-term devices and create a critical measurement bottleneck in hybrid quantum-classical algorithms. This bottleneck is particularly acute in application domains like drug discovery and materials science, where high-precision measurement is a prerequisite for obtaining scientifically useful results [22] [23]. The core challenge lies in the interplay between inherent quantum noise and the statistical limitations of quantum measurement, where extracting precise expectation values—the fundamental data unit for variational algorithms—requires extensive sampling that itself is corrupted by device imperfections. This article analyzes how NISQ device noise specifically exacerbates the quantum measurement problem, surveys current mitigation strategies, and provides a detailed experimental framework for researchers navigating these constraints in practical applications, particularly within pharmaceutical research and development.

The Anatomy of NISQ Noise and Its Impact on Measurement

Physical and Logical Resource Constraints

Quantum resources in the NISQ era can be categorized into physical and logical layers. Physical resources reflect the fundamental hardware constraints: the number of qubits, error rates (gate, readout, and decoherence), coherence time, and qubit connectivity [21]. Logical resources are the software-visible abstractions built atop this physical substrate: supported gate sets, maximum circuit depth, and available error mitigation techniques. The measurement problem sits at the interface of these layers, where the physical imperfections of the hardware directly manifest as errors in the logical data produced.

Table: Key NISQ Resource Limitations and Their Impact on Measurement

| Resource Type | Specific Limitation | Direct Impact on Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Qubits | Limited count (50-1000+) | Restricts problem size (qubit number) and measurement circuit complexity |

| Gate Fidelity | Imperfect operations (typically 99-99.9%) | Introduces state preparation errors before measurement |

| Readout Fidelity | High readout errors (1-5% per qubit) | Directly corrupts measurement outcomes |

| Coherence Time | Short (microseconds to milliseconds) | Limits total circuit depth, including measurement circuits |

| Qubit Connectivity | Limited topology (linear, 2D grid) | Increases circuit depth for measurement, compounding error |

How Noise Corrupts the Measurement Process

The process of measuring a quantum state to estimate an observable's expectation value is vulnerable to multiple noise channels. State preparation and measurement (SPAM) errors occur when the initial state is incorrect or the final measurement misidentifies the qubit state. For example, readout errors on the order of (10^{-2}) are common, making high-precision measurements particularly challenging [23]. Gate errors throughout the circuit accumulate, ensuring that the state being measured is not the intended target state. Decoherence causes the quantum state to lose its phase information over time, which is critical for algorithms that rely on quantum interference. These noise sources transform the ideal probability distribution of measurement outcomes into a distorted one, biasing the estimated expectation values that are the foundation of hybrid algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) [24].

Quantitative Analysis: Error Magnitudes and Resource Overheads

Achieving chemical precision (approximately (1.6 × 10^{-3}) Hartree) in molecular energy calculations is a common requirement for quantum chemistry applications. Recent experimental work highlights the severe resource overheads imposed by NISQ noise. Without advanced mitigation, raw measurement errors on current hardware can reach 1-5%, far above the required precision [23]. This gap necessitates sophisticated error mitigation and measurement strategies that dramatically increase the required resources.

Table: Measurement Error and Mitigation Performance Data from Recent Experiments

| Experiment / Technique | Raw Readout Error | Post-Mitigation Error | Key Resource Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Energy (BODIPY) [23] | 1-5% | 0.16% (1 order of magnitude reduction) | Shot overhead reduction via locally biased random measurements |

| Leakage Benchmarking [24] | Not Applicable | Protocol insensitive to SPAM errors | Additional characterization circuits (iLRB) |

| Quantum Detector Tomography [23] | Mitigates time-dependent drift | Enables unbiased estimation | Circuit overhead from repeated calibration settings |

| Dynamical Decoupling [24] | Reduces decoherence during idle periods | Enhanced algorithm performance | Additional pulses during circuit idle times |

The data demonstrates that while mitigation techniques are effective, they introduce their own overheads in terms of additional quantum circuits, classical post-processing, and the number of measurement shots required. This creates a complex trade-off space where researchers must balance measurement precision against total computational cost.

Experimental Protocols for Noise-Resilient Measurement

Protocol 1: Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements with Quantum Detector Tomography

This protocol leverages informationally complete POVMs (Positive Operator-Valued Measures) to enable robust estimation of multiple observables and mitigate readout noise.

Detailed Methodology:

- Measurement Setup Selection: Choose a set of measurement bases that are informationally complete. For n qubits, this typically requires (4^n - 1) different measurement settings, though symmetries can reduce this number.

- Parallel Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): Before running the main experiment, characterize the noisy measurement apparatus. This involves preparing a complete set of probe states (e.g., (|0\rangle), (|1\rangle), (|+\rangle), (|-\rangle), (|+i\rangle), (|-i\rangle) for each qubit) and measuring them to construct a calibration matrix, (\Lambda), which describes the probability of an ideal outcome given an actual physical outcome.

- Data Acquisition (Blended Scheduling): Execute the main experiment's quantum circuits interleaved with periodic QDT calibration circuits. This "blended" scheduling accounts for temporal drift in detector noise over the timescale of a long experiment.

- Classical Post-Processing: Use the calibration matrix (\Lambda) to correct the raw measurement statistics from the main experiment. An unbiased estimator for the molecular energy (or other observable) is then constructed from the corrected statistics, significantly reducing the bias introduced by readout noise [23].

Protocol 2: Locally Biased Random Measurements for Shot Reduction

This technique reduces the number of measurement shots (samples) required, which is a critical resource when noise necessitates large sample sizes for precise estimation.

Detailed Methodology:

- Hamiltonian Analysis: Decompose the target molecular Hamiltonian, (H), into a linear combination of Pauli strings: (H = \sumi ci P_i).

- Setting Prioritization: Instead of measuring all Pauli terms uniformly, assign a higher sampling probability to terms with larger (|c_i|) (larger magnitude coefficients). This "local bias" focuses shots on the measurements that contribute most significantly to the total energy.

- Random Sampling: For each measurement shot, randomly select a Pauli term (Pi) with probability proportional to (|ci|).

- Estimation: Calculate the energy estimate from the weighted average of the outcomes. This biased sampling strategy maintains the informational completeness of the measurement while reducing the variance of the estimator, thereby lowering the shot overhead required to achieve a target precision [23].

Diagram: Integrated Workflow for Noise-Resilient Measurement. The protocol combines Informationally Complete (IC) measurements with locally biased sampling to mitigate noise and reduce resource overhead.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Robust NISQ Experimentation

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NISQ Measurement Challenges

| Tool / Technique | Primary Function | Application in Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) [23] | Characterizes the noisy measurement apparatus | Builds a calibration model to correct readout errors in subsequent experiments. |

| Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements [23] | Enables estimation of multiple observables from a single dataset | Allows reconstruction of the quantum state or specific observables, maximizing data utility. |

| Locally Biased Random Measurements [23] | Optimizes the allocation of measurement shots | Reduces the number of shots (samples) required to achieve a desired precision for complex observables. |

| Dynamical Decoupling (DD) [24] | Protects idle qubits from decoherence | Applied during periods of inactivity in a circuit to extend effective coherence time for measurement. |

| Leakage Randomized Benchmarking (LRB) [24] | Characterizes leakage errors outside the computational subspace | Diagnoses a specific type of error that can corrupt measurement outcomes, insensitive to SPAM errors. |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) [24] | Estimates the noiseless value of an observable | Intentionally increases circuit noise (e.g., by stretching gates) and extrapolates back to a zero-noise value. |

| Dioxo(sulphato(2-)-O)uranium | Dioxo(sulphato(2-)-O)uranium, CAS:16984-59-1, MF:C2H2O6U, MW:362.08 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-Ethyl-3-methyl-3-phospholene 1-oxide | 1-Ethyl-3-methyl-3-phospholene 1-oxide, CAS:7529-24-0, MF:C7H13OP, MW:144.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Case Study: Molecular Energy Estimation of BODIPY on NISQ Hardware

A recent experiment estimating the energy of the BODIPY molecule provides a concrete example of these protocols in action. The study used an 8-qubit IBM Eagle r3 processor to measure the energy of the Hartree-Fock state for a BODIPY-4 molecule in a 4e4o active space, a Hamiltonian comprising 361 Pauli strings [23].

Experimental Workflow:

- State Preparation: The Hartree-Fock state was prepared, which, being a separable state, required no two-qubit gates, thus isolating measurement errors from gate errors.

- Integrated Measurement Protocol: The researchers implemented a combined strategy using:

- Informationally complete measurements to enable Quantum Detector Tomography.

- Locally biased random measurements to reduce shot overhead.

- Blended scheduling of main circuits and QDT circuits to mitigate time-dependent noise.

- Results: The raw readout error on the device was on the order of (10^{-2}). By applying the full protocol, the team reduced the measurement error to 0.16%, an order-of-magnitude improvement, bringing it close to the threshold of chemical precision ((1.6 × 10^{-3}) Hartree) [23]. This demonstrates that even with noisy hardware, sophisticated measurement strategies can extract high-precision data relevant to drug discovery applications.

Diagram: NISQ Noise and the Measurement Bottleneck. The diagram illustrates the causal relationship where NISQ hardware noise exacerbates the fundamental quantum measurement problem, creating a critical bottleneck for hybrid algorithms. This, in turn, impacts high-precision application domains like drug discovery, driving the need for the mitigation strategies shown.

The measurement problem on NISQ devices is a multi-faceted challenge arising from the confluence of statistical sampling and persistent hardware noise. However, as demonstrated by the experimental protocols and case studies presented, a new toolkit of hardware-aware error mitigation and advanced measurement strategies is emerging. These techniques, including informationally complete measurements, quantum detector tomography, and biased sampling, enable researchers to extract high-precision data from noisy devices, pushing the boundaries of what is possible in the NISQ era. For drug development professionals, this translates to a rapidly evolving capability to perform more accurate molecular simulations, such as protein-ligand binding and hydration analysis, with tangible potential to reduce the time and cost associated with bringing new therapies to patients [22] [25]. The path forward relies on continued hardware-algorithm co-design, where application-driven benchmarks guide the development of both quantum hardware and the software tools needed to tame the noise and overcome the measurement bottleneck.

This whitepaper presents a technical analysis of the primary bottlenecks hindering the application of Quantum Machine Learning (QML) to molecular property prediction, with a specific focus on the quantum measurement bottleneck within hybrid quantum-classical algorithms. While QML holds promise for accelerating drug discovery and materials science, its practical implementation faces significant constraints [3] [26]. Current research indicates that the process of extracting classical information from quantum systems—the measurement phase—is a critical limiting factor in hybrid workflows [3]. This case study examines a recent, large-scale experiment in Quantum Reservoir Computing (QRC) to dissect these challenges and outline potential pathways for mitigation.

Experimental Background: A QRC Case Study

A collaborative March 2025 study by researchers from Merck, Amgen, Deloitte, and QuEra investigated the use of QRC for predicting molecular properties, a common task in drug discovery pipelines [27]. This research provides a concrete, up-to-date context for analyzing QML bottlenecks.

- Motivation and Problem Scope: The study targeted the "small-data problem" prevalent in domains like biopharma and oncology, where datasets are often limited to 100-300 samples. In such scenarios, classical machine learning models are prone to overfitting and high performance variability [27].

- Technical Approach: The team employed QuEra's neutral-atom quantum hardware as a physical reservoir. In this framework, the quantum system itself is not trained; instead, its inherent dynamics are used to transform input data into a richer, higher-dimensional feature space [27].

Detailed Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The methodology from the QRC study offers a template for how QML is applied to molecular data and where bottlenecks emerge. The end-to-end workflow is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Quantum Reservoir Computing Workflow for Molecular Property Prediction

Step-by-Step Protocol

- Data Preprocessing and Encoding: Small, high-value molecular datasets were cleaned and classical feature engineering was applied. The resulting numerical features were encoded into the neutral-atom quantum processor by adjusting local parameters such as atom positions and pulse strengths [27].

- Quantum Evolution: The encoded data naturally evolved under the rich, analog dynamics of the quantum hardware. This evolution non-linearly transformed the input data without requiring heavily parameterized quantum circuits [27].

- Quantum Measurement and Embedding Extraction: The quantum states were measured multiple times. The collective outcomes from these repeated measurements formed a new set of "quantum-processed" classical features, termed embeddings [27].

- Classical Post-Processing: A classical machine learning model (a random forest) was trained exclusively on these quantum-derived embeddings to perform the final molecular property prediction. This approach isolates the training to the classical side, avoiding challenges like vanishing gradients in hybrid training [27].

Analysis of the Quantum Measurement Bottleneck

The QRC workflow explicitly reveals the quantum measurement bottleneck as a primary constraint. This bottleneck arises from the fundamental nature of quantum mechanics and is exacerbated by current hardware limitations.

- The Core Problem: In quantum computing, the state of a qubit is probabilistic. A single measurement of a quantum state yields a single, probabilistic classical outcome (a "shot"). To accurately estimate the expectation value of a quantum observable—which is the useful classical data point for machine learning—the same quantum circuit must be executed and measured a large number of times [3] [27]. This process is computationally expensive and time-consuming.

- Impact on Hybrid Algorithms: The requirement for repeated measurements (often thousands or millions of shots) to achieve statistically significant results creates a major throughput bottleneck in hybrid quantum-classical loops [3]. This is particularly critical in algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA), where the classical optimizer requires a reliable cost-function value from the quantum computer, necessitating extensive sampling in each iteration [3] [28].

- Compounding Effect of Noise: On current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, gate errors and decoherence further corrupt the quantum state [3]. This noise often necessitates even more measurement shots to average out errors, intensifying the bottleneck. Techniques like zero-noise extrapolation and probabilistic error cancellation exist but further increase the sampling overhead [3].

Quantitative Performance and Bottlenecks

The QRC study provided quantitative results that highlight both the potential of QML and the context in which bottlenecks become most apparent. The table below summarizes key performance metrics compared to classical methods.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of QRC vs. Classical Methods on Molecular Property Prediction

| Dataset Size (Samples) | QRC Approach (Accuracy/Performance) | Classical Methods (Accuracy/Performance) | Key Bottleneck Manifestation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100-200 | Consistently higher accuracy and lower variability [27] | Lower accuracy, higher performance variability [27] | Justified Overhead: Measurement cost is acceptable given the significant performance gain on small data. |

| ~800+ | Performance gap narrows; convergence with classical methods [27] | Competitive performance [27] | Diminishing Returns: High measurement cost is not justified by a marginal performance gain. |

| Scalability Test | Successfully scaled to over 100 qubits [27] | N/A | Throughput Limit: The system scales, but the measurement bottleneck limits training and inference speed. |

The data shows that the quantum advantage is most pronounced for small datasets, where the resource overhead of extensive quantum measurement can be tolerated due to the lack of classical alternatives. As datasets grow, the computational burden of this bottleneck becomes harder to justify.

The Researcher's Toolkit

The following table details key components and their roles in conducting QML experiments for molecular property prediction, as exemplified by the featured QRC study.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for QML in Molecular Property Prediction

| Item / Solution | Function / Role in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Neutral-Atom Quantum Hardware (e.g., QuEra) | Serves as the physical QPU; provides a scalable platform with natural quantum dynamics for data transformation [27]. |

| Classical Machine Learning Library (e.g., for Random Forest) | Performs the final model training on quantum-derived embeddings, circumventing the need to train the quantum system directly [27]. |

| Data Encoding Scheme | Translates classical molecular feature vectors into parameters (e.g., laser pulses, atom positions) that control the quantum system [27]. |

| Error Mitigation Software (e.g., Fire Opal) | Applies advanced techniques to suppress errors in quantum circuit executions, reducing the number of shots required for accurate results and mitigating the measurement bottleneck [28]. |

| Tribenuron-methyl | Tribenuron-methyl|CAS 101200-48-0|Research Compound |

| cudraflavone B | Cudraflavone B - Premium PF|CAS 19275-49-1 |

The quantum measurement bottleneck represents a fundamental challenge that must be addressed to unlock the full potential of QML for enterprise applications like drug discovery. The analyzed QRC case study demonstrates that while quantum methods can already provide value in specific, small-data contexts, their broader utility is gated by this throughput constraint.

Future research must focus on co-designing algorithms and hardware to alleviate this bottleneck. Promising directions include developing more efficient measurement strategies, advancing error mitigation techniques to reduce shot requirements [28], and creating new algorithm classes that extract more information per measurement. Progress in these areas will be essential for QML to transition from a promising research topic to a standard tool in the computational scientist's arsenal.

Mitigation in Practice: Algorithmic and Hardware Strategies for Drug Discovery

The development of hybrid quantum-classical algorithms is critically constrained by the quantum measurement bottleneck, a fundamental challenge where the extraction of information from a quantum system is inherently slow, noisy, and destructive. This bottleneck severely limits the feedback speed and data throughput necessary for real-time quantum error correction (QEC), creating a dependency between quantum and classical subsystems. Effective QEC requires classical processors to decode error syndromes and apply corrections within qubit coherence times, a task growing exponentially more demanding as quantum processors scale. This technical guide examines cutting-edge advances in quantum error correction, focusing on two transformative approaches: resource-efficient Quantum Low-Density Parity-Check (qLDPC) codes and the application of AI-powered decoders. These innovations collectively address the measurement bottleneck by improving encoding efficiency and accelerating classical decoding components, thereby advancing the feasibility of fault-tolerant quantum computing.

Quantum Error Correction Codes: From Surface Codes to qLDPC

Quantum error correction codes protect logical qubits by encoding information redundantly across multiple physical qubits. The choice of encoding scheme directly impacts the qubit overhead, error threshold, and the complexity of the required classical decoder.

Surface Codes: The Established Approach

Surface codes have been the leading QEC approach due to their planar connectivity and relatively high error thresholds. In a surface code, a logical qubit is formed by a d × d grid of physical data qubits, with d²-1 additional stabilizer qubits performing parity checks [7]. The code's distance d represents the number of errors required to cause a logical error without detection. While surface codes have demonstrated sub-threshold operation in experimental settings, their poor encoding rate necessitates large qubit counts—potentially millions of physical qubits per thousand logical qubits—creating massive overheads for practical quantum applications [29].

qLDPC Codes: A Resource-Efficient Alternative

Quantum Low-Density Parity-Check (qLDPC) codes represent a promising alternative with significantly improved qubit efficiency. These codes are defined by sparse parity-check matrices where each qubit participates in a small number of checks and vice versa. Recent breakthroughs have demonstrated qLDPC codes achieving 10-100x reduction in physical qubit requirements compared to surface codes for the same level of error protection [29].

Recent qLDPC Variants and Breakthroughs:

- Bivariate Bicycle Codes: A class of qLDPC codes with favorable properties for implementation, including the [[144,12,12]] code which encodes 12 logical qubits in 144 physical qubits with distance 12 [30]. Numerical simulations suggest these codes require approximately 10x fewer qubits compared to equivalent surface code architectures [31].

- SHYPS Codes: Photonic's recently announced qLDPC family demonstrates the ability to perform both computation and error correction using up to 20x fewer physical qubits than traditional surface code approaches [29]. This code family specifically addresses the historical challenge of implementing quantum logic gates within qLDPC frameworks.

- Concatenated Symplectic Double Codes: Quantinuum's approach combines symplectic double codes with the [[4,2,2]] Iceberg code through code concatenation, creating codes with high encoding rates and "SWAP-transversal" gates well-suited for their QCCD architecture [32].

Table 1: Comparison of Quantum Error Correction Codes

| Code Type | Physical Qubits per Logical Qubit | Error Threshold | Connectivity Requirements | Logical Gate Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Code | ~1000 for 10â»Â¹Â² error rate [7] | ~1% [31] | Nearest-neighbor (planar) | Well-established through lattice surgery |

| qLDPC Codes | ~50-100 for similar performance [29] | ~0.1%-1% [31] | High (non-local) | Recently demonstrated (e.g., SHYPS) [29] |

| Concatenated Codes | Varies by implementation | ~0.1%-1% | Moderate | Efficient for specific architectures [32] |

Classical Decoding Algorithms: The Computational Challenge

Decoding represents the computational core of quantum error correction, where classical algorithms process syndrome data to identify and correct errors. The performance of these decoders directly impacts the effectiveness of the entire QEC system.

Belief Propagation and Enhanced Variants

Belief Propagation (BP) decoders leverage message-passing algorithms on the Tanner graph representation of QEC codes. While standard BP achieves linear time complexity ð’ª(n) in the code length n, it often fails to converge for degenerate quantum errors due to short cycles in the Tanner graph [31].

Advanced BP-Based Decoders:

- BP+OSD (Ordered Statistics Decoding): A two-stage algorithm where BP is followed by a post-processing step that performs matrix factorizations to rank the most likely errors. While highly accurate, BP+OSD increases worst-case runtime complexity to ð’ª(n³) [30].

- BP+OTF (Ordered Tanner Forest): Introduces a post-processing stage that constructs a loop-free Tanner forest using a modified Kruskal's algorithm with ð’ª(n log n) complexity, maintaining near-linear runtime while achieving accuracy comparable to state-of-the-art decoders [31].

- BP+BP+OTF: A three-stage decoder optimized for circuit-level noise that applies BP to the full detector graph, maps soft information to a sparsified graph, then applies BP+OTF post-processing, demonstrating similar error suppression to BP+OSD with significantly faster runtime [31].

AI-Powered Decoding Approaches

Machine learning decoders represent a paradigm shift from algorithm-based to data-driven decoding, potentially surpassing human-designed algorithms by learning directly from experimental data.

Neural Decoder Architectures:

- AlphaQubit: A recurrent-transformer-based neural network that outperformed other decoders on real-world data from Google's Sycamore processor for distance-3 and distance-5 surface codes. The decoder maintains its advantage on simulated data with realistic noise including cross-talk and leakage up to distance 11 [7].

- Transformer-Based NVIDIA Decoder: Developed in collaboration with QuEra, this decoder outperformed the Most-Likely Error (MLE) decoder for magic state distillation circuits while offering significantly better scalability. The attention mechanism enables it to dynamically model dependencies between different syndrome inputs [33].

- Training Methodologies: These AI decoders employ a two-stage training process—pretraining on massive synthetic data (billions of samples) generated through simulation, followed by fine-tuning with limited experimental data. This approach reduces the need for costly quantum hardware time while adapting to real-world noise characteristics [7].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Quantum Error Correction Decoders

| Decoder Type | Time Complexity | Accuracy | Scalability | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum-Weight Perfect Matching (MWPM) | ð’ª(n³) | Moderate | Good for surface codes | Well-established for topological codes |

| BP+OSD | ð’ª(n³) | High [31] | Limited by cubic scaling | High accuracy for qLDPC codes [30] |

| BP+OTF | ð’ª(n log n) [31] | High [31] | Excellent | Near-linear scaling with high accuracy |

| Neural (AlphaQubit) | ð’ª(1) during inference | State-of-the-art [7] | Promising | Adapts to complex noise patterns |

| Transformer (NVIDIA) | ð’ª(1) during inference | Better than MLE [33] | Promising | Captures complex syndrome interactions |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Methodology for BP+OTF Decoder Benchmarking

The BP+OTF decoder was evaluated through Monte Carlo simulations under depolarizing circuit-level noise for bivariate bicycle codes and surface codes [31]. The experimental protocol followed these stages:

- Circuit-Level Noise Modeling: Implemented a comprehensive noise model accounting for gate errors, measurement errors, and idle errors during syndrome extraction circuits.

- Detector Graph Construction: Represented the error syndromes using a detector graph that maps error mechanisms in the QEC circuit to measured syndromes.

- Sparsification Procedure: Applied a novel transfer matrix technique to map soft information from the full detector graph to a sparsified graph with fewer short-length loops, enhancing OTF effectiveness.

- Three-Stage Decoding:

- Stage 1: Standard BP on the full detector graph

- Stage 2: BP on the sparsified detector graph using transferred soft information as priors

- Stage 3: OTF post-processing on the sparsified graph guided by BP soft information

- Termination Condition: The decoder terminated at the first successful decoding stage, optimizing runtime efficiency.

This implementation demonstrated comparable error suppression to BP+OSD and minimum-weight perfect matching while maintaining almost-linear runtime complexity [31].

Neural Decoder Training Protocol

The training of AI-powered decoders like AlphaQubit followed a meticulous two-stage process [7]:

Pretraining Phase:

- Utilized synthetic data from detector error models (DEMs) fitted to experimental detection event correlations

- Alternative pretraining used weights derived from Pauli noise models based on device calibration data

- Training scale: Up to 2 billion samples for DEMs or 500 million samples for superconducting-inspired circuit depolarizing noise (SI1000)

Fine-Tuning Phase:

- Partitioned experimental samples (325,000 for Sycamore experiment) into training and validation sets

- Employed cross-validation with even samples for training and odd samples for testing

- Ensembling: Combined 20 independently trained models to enhance performance

Performance Metrics:

- Primary metric: Logical Error per Round (LER) - the fraction of experiments where the decoder fails for each additional error-correction round

- Calculated error-suppression ratio Λ to compare different code distances

This protocol enabled the decoder to adapt to the complex, unknown underlying error distribution while working within practical experimental data budgets.

Implementing advanced QEC requires specialized tools spanning quantum hardware control, classical processing, and software infrastructure. Below are essential resources for experimental research in this domain.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Advanced Quantum Error Correction

| Tool/Platform | Function | Key Features | Representative Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| CUDA-Q QEC [30] | Accelerated decoding libraries | BP+OSD decoder with order-of-magnitude speedup, qLDPC code generation | Evaluating [[144,12,12]] code performance on NVIDIA Grace Hopper |

| DGX Quantum [30] | QPU-GPU integration | Ultra-low latency (≤4μs) link between quantum and classical processors | Real-time decoding for systems requiring microsecond feedback |

| Tesseract [34] | Search-based decoder | High-performance decoding for broad QEC code classes under circuit-level noise | Google Quantum AI's surface code experiments |

| Stim [33] | Stabilizer circuit simulator | Fast simulation of Clifford circuits for synthetic data generation | Training data for AI decoders (integrated with CUDA-Q) |

| PhysicsNeMo [33] | AI framework for physics | Transformer-based architectures for quantum decoding | NVIDIA's decoder for QuEra's magic state distillation |

| QEC25 Tutorial Resources [34] | Educational framework | Comprehensive tutorials on BP, OSD, and circuit-level noise modeling | Yale Quantum Institute's preparation for QEC experiments |

System Integration and Hardware Considerations

The quantum measurement bottleneck necessitates tight integration between quantum and classical subsystems, with stringent requirements on latency, bandwidth, and processing capability.

Latency and Bandwidth Requirements

Real-time QEC imposes extreme constraints on classical processing systems. The decoding cycle must complete within the qubit coherence time, typically requiring sub-microsecond latencies for many qubit platforms [35]. This challenge is compounded by massive data rates—syndrome extraction can generate hundreds of terabytes per second from large-scale quantum processors, comparable to "processing the streaming load of a global video platform every second" [35].

Hardware solutions addressing these challenges include:

- NVIDIA DGX Quantum: Enables GPUs to connect to quantum hardware with round-trip latencies under 4μs through integration with Quantum Machines' OPX control system [30].

- SEEQC's Digital Link: Replaces analog-to-digital conversion bottlenecks with entirely digital protocols, reducing bandwidth requirements from TB/s to GB/s while achieving 6μs round-trip latency [30].

- Distributed Decoding Architectures: Partition decoding workloads across multiple GPUs or specialized ASICs to meet throughput demands for large code distances.

Resource Scaling Projections

The resource requirements for fault-tolerant quantum computing create complex engineering trade-offs. While qLDPC codes dramatically reduce physical qubit counts, they impose higher connectivity requirements and more complex decoding workloads. Industry projections indicate major hardware providers targeting fault-tolerant operation by 2028-2029 [36]:

- IBM: Plans error correction decoder with 120 physical qubits in 2026, predicting fault tolerance by 2029

- Oxford Quantum Circuits (OQC): Targets MegaQuOp system with 200 logical qubits in 2028

- IQM: Transition from NISQ to QEC processors planned for 2027 using initial 300 physical qubits

These roadmaps reflect a broader industry shift from noisy intermediate-scale quantum devices to error-corrected systems, with government initiatives like DARPA's Quantum Benchmarking Initiative providing funding structures oriented toward utility-scale systems by 2033 [36].

The integration of qLDPC codes with AI-powered decoders represents a transformative approach to overcoming the quantum measurement bottleneck in hybrid algorithms. qLDPC codes address the resource overhead challenge through dramatically improved encoding rates, while AI decoders enhance decoding accuracy and adaptability to realistic noise patterns. Together, these technologies reduce both the physical resource requirements and the classical computational burden of quantum error correction.

Future research directions will focus on several critical areas: