Quantum Error Mitigation for Molecular Simulations: Advancing VQE Accuracy in Drug Discovery and Chemistry

This article provides a comprehensive review of error mitigation techniques for the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) applied to molecular systems, a critical challenge in near-term quantum computing.

Quantum Error Mitigation for Molecular Simulations: Advancing VQE Accuracy in Drug Discovery and Chemistry

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of error mitigation techniques for the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) applied to molecular systems, a critical challenge in near-term quantum computing. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of VQE and the impact of noise on quantum hardware. The scope encompasses methodological advances from single-reference to multireference error mitigation, practical troubleshooting for optimization on noisy devices, and a comparative validation of leading techniques. By synthesizing current research and performance benchmarks, this work aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to enhance the reliability of quantum simulations for chemistry and biomedical applications.

The Critical Challenge of Noise in Quantum Chemistry Simulations

Understanding the VQE Algorithm and its Promise for Molecular Ground State Energy Calculation

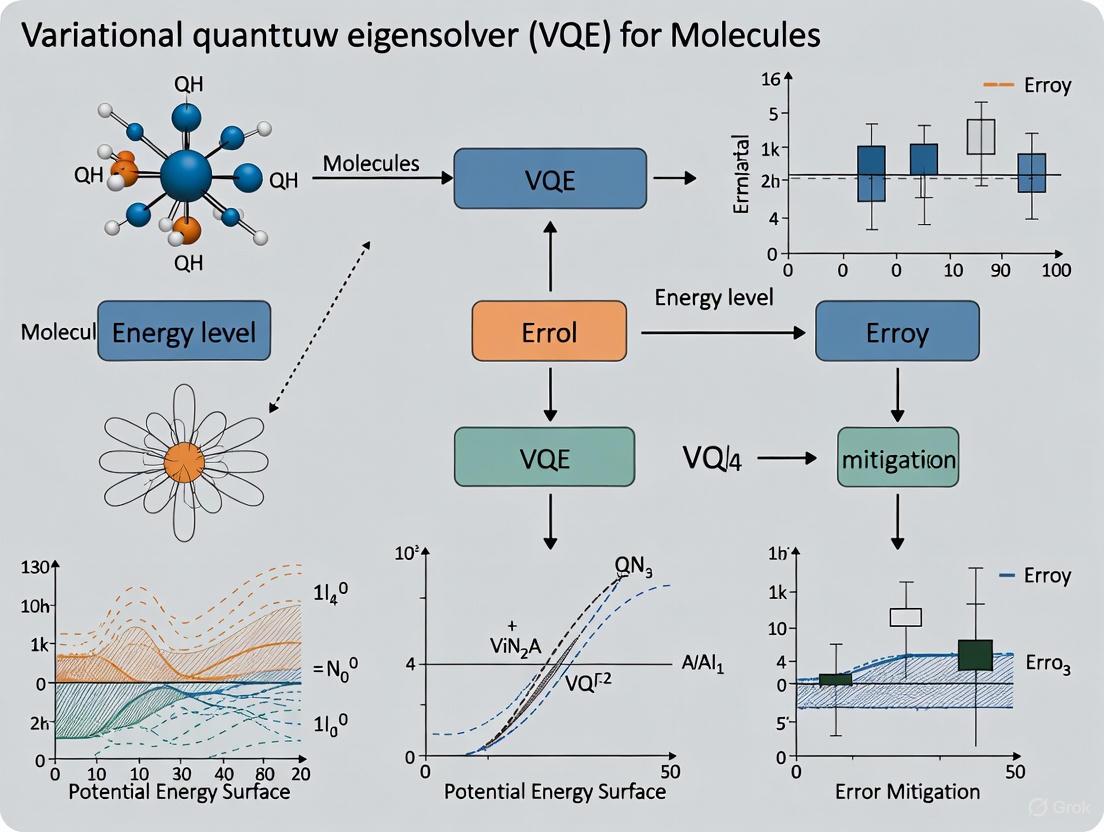

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed to find the ground state energy of molecular systems, a fundamental challenge in quantum chemistry with applications ranging from drug discovery to materials design [1]. As a leading algorithm for noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, VQE leverages the complementary strengths of quantum and classical processors: a quantum processor prepares and measures parameterized trial wavefunctions, while a classical optimizer adjusts these parameters to minimize the energy expectation value [2].

The algorithm operates on the Rayleigh-Ritz variational principle, which states that for any trial wavefunction ( |\psi(\theta)\rangle ), the expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian ( \hat{H} ) satisfies ( E(\theta) = \langle\psi(\theta)|\hat{H}|\psi(\theta)\rangle \ge \mathcal{E}0 ), where ( \mathcal{E}0 ) is the true ground state energy [2]. The VQE workflow begins by mapping the electronic structure Hamiltonian from second quantization to a qubit representation using transformations such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev [3]. An initial state, typically the Hartree-Fock state, is prepared on the quantum processor, followed by a parameterized ansatz circuit ( U(\theta) ) that introduces electron correlation [3] [2]. The energy expectation value is estimated through repeated measurements, and a classical optimizer adjusts the parameters ( \theta ) to minimize this energy, iterating until convergence criteria are met.

VQE Implementation and Workflow

The practical implementation of VQE requires careful coordination between quantum and classical computing resources. The following diagram illustrates the core feedback loop of the VQE algorithm.

Algorithmic Components and Experimental Considerations

Ansatz Selection

The choice of ansatz circuit is critical as it determines both the expressiveness of the trial wavefunction and the circuit's susceptibility to noise. Two primary categories dominate:

- Physically-motivated ansatze: The Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) ansatz, particularly UCCSD (Single and Double excitations), is inspired by classical quantum chemistry methods [2]. It provides chemically meaningful states but typically requires deep circuits.

- Hardware-efficient ansatze: These ansatze, such as the Compact Heuristic Circuit (CHC), prioritize reduced circuit depth and compatibility with native gate sets [4]. They trade some physical intuition for improved noise resilience.

Recent developments include ADAPT-VQE algorithms that iteratively construct ansatz circuits element by element, selecting operators that provide the steepest energy gradient at each step [2]. This approach typically yields shorter, more noise-resilient circuits compared to fixed ansatze.

Measurement and Optimization

The molecular Hamiltonian, expressed as a sum of Pauli operators ( \hat{H} = \sum{\alpha} h{\alpha} P{\alpha} ), requires measuring the expectation value of each term ( P{\alpha} ) [3]. The number of measurements (shots) needed for energy estimation scales as ( O(\epsilon^{-2} \cdot N) ), where ( \epsilon ) is the desired precision and ( N ) is the number of qubits [3]. Classical optimizers range from gradient-free methods like NFT for small problems [5] to gradient-based approaches for larger systems, though the latter must contend with the barren plateau phenomenon where gradients vanish exponentially with system size [2].

Quantum Error Mitigation Techniques for VQE

Current NISQ devices suffer from various noise sources that limit VQE performance. Quantum Error Mitigation (QEM) techniques aim to reduce the impact of these errors without the qubit overhead required by full fault tolerance. The following table summarizes prominent QEM strategies relevant to VQE applications.

Table 1: Quantum Error Mitigation Techniques for VQE

| Technique | Key Principle | Requirements | Performance & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference-State Error Mitigation (REM) [3] | Uses classically-computable reference state (e.g., Hartree-Fock) to calibrate hardware noise. | Exactly-solvable reference state preparable on quantum device. | Effective for weakly correlated systems; fails for strong correlation. Low sampling overhead. |

| Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM) [3] | Extends REM using multiple Slater determinants for strongly correlated systems. | Compact multireference states with high target-state overlap. | Significant improvement over REM for stretched bonds in Nâ‚‚, Fâ‚‚; balanced expressivity/noise. |

| Deep-Learned Error Mitigation [6] | Neural networks predict ideal expectation values from noisy outputs and circuit descriptors. | Training data from quantum device; circuit knitting to reduce cost. | High accuracy for deep circuits; classical cost reduced via partial knitting. |

| Randomized Compiling (RC) + Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) [7] | RC converts coherent noise to stochastic Pauli errors; ZNE extrapolates to zero noise. | Multiple circuit executions at different noise levels. | Reduces coherent noise errors by up to 2 orders of magnitude; synergistic effect. |

| Symmetry Verification [3] | Post-selects measurements that preserve molecular Hamiltonian symmetries. | Knowledge of conserved quantities (e.g., particle number). | Removes errors violating symmetries; measurement overhead. |

Advanced Error Mitigation Methodologies

Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM)

For strongly correlated systems where single-reference REM fails, MREM provides a sophisticated alternative. The protocol leverages multireference states composed of linear combinations of Slater determinants identified through inexpensive classical methods [3]. The workflow involves:

- Reference Selection: Identify dominant Slater determinants from classical methods like CI or DMRG.

- Circuit Implementation: Prepare multireference states using Givens rotations, which preserve particle number and spin symmetry while maintaining controlled circuit depth.

- Error Calibration: Measure the energy deviation between the noisy quantum computation and exact classical result for the multireference state.

- Mitigation Application: Apply the calibrated error correction to the target VQE result.

This approach has demonstrated significant improvements for challenging molecular systems like stretched Nâ‚‚ and Fâ‚‚ bonds, where static correlation is prominent [3].

Synergistic Error Mitigation Protocols

Combining multiple error mitigation techniques can yield superior results. The integration of Randomized Compiling (RC) and Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) exemplifies this principle [7]:

- Randomized Compiling transforms coherent noise into stochastic Pauli noise through random gate recompilation, creating a more predictable error model.

- Zero-Noise Extrapolation then systematically extrapolates measurements taken at intentionally amplified noise levels back to the zero-noise limit.

This combined approach has demonstrated up to two orders of magnitude error reduction for VQE simulations of small molecules affected by coherent noise [7].

Performance Analysis and Tolerance to Hardware Errors

Understanding the relationship between hardware error rates and VQE accuracy is essential for practical deployment. Recent density-matrix simulations provide quantitative insights into the gate-error probabilities required for chemically accurate results.

Table 2: Maximum Tolerable Gate-Error Probabilities for Chemically Accurate VQE Simulations

| System Condition | Required Gate-Error Probability | Key Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Small Molecules (4-14 orbitals) [2] | 10â»â¶ to 10â»â´ | Ansatz choice, circuit depth, molecular size |

| With Error Mitigation [2] | 10â»â´ to 10â»Â² | Mitigation technique, additional sampling overhead |

| Scaling Relation [2] | ( pc \propto N{\text{II}}^{-1} ) | ( N_{\text{II}} ): Number of noisy two-qubit gates |

| System Size Dependence [2] | Decreases with molecular size | Even with error mitigation |

Comparative Analysis of VQE Approaches

Fixed ansatze like UCCSD and k-UpCCGSD provide chemically intuitive approaches but generally exhibit higher circuit depths and lower noise tolerance [2]. In contrast, ADAPT-VQE algorithms demonstrate superior performance:

- ADAPT-VQE constructs circuits iteratively, typically achieving shorter circuits and better noise resilience [2].

- Performance varies with operator pool selection; gate-efficient elements generally outperform physically-motivated operators in noisy conditions [2].

- Recent advances combine ADAPT-VQE with classical pre-optimization using tools like the sparse wave function circuit solver (SWCS), offloading significant computational overhead to classical resources [8].

The maximum tolerable gate-error probability ( pc ) for any VQE implementation follows an inverse relationship with the number of noisy two-qubit gates ( N{\text{II}} ): ( pc \propto N{\text{II}}^{-1} ) [2]. This underscores the critical importance of circuit depth minimization, particularly as molecular size increases.

Experimental Protocols for VQE Implementation

Protocol: Hydrogen Molecule Simulation using Hardware-Efficient Ansatz

This protocol outlines the specific methodology used for Hâ‚‚ ground state potential calculation, as implemented on the AQT quantum processor [5].

Hamiltonian Preparation

- Transform the Hâ‚‚ molecular Hamiltonian into qubit representation using the Jordan-Wigner transformation at various interatomic distances.

- Express the Hamiltonian as a sum of Pauli operators with precomputed coefficients.

Ansatz Implementation

- Initialize the quantum register to ( |0\rangle^{\otimes n} ).

- Apply a hardware-efficient ansatz composed of alternating layers of single-qubit RY rotations and entangling CNOT gates.

- Use a linear chain connectivity for CNOT gates compatible with device topology.

Parameter Optimization

- Initialize RY rotation angles randomly.

- For each iteration (15 total iterations, 200 shots each):

- Measure the expectation value of each Hamiltonian term.

- Compute total energy as weighted sum.

- Update rotation angles using the NFT optimizer to minimize energy.

- Repeat optimization for 9 different initial states to assess convergence.

Error Mitigation and Validation

- Compare final energy with classically computed exact result.

- Calculate energy difference from theoretical ground state at 0.753Ã….

- Assess reproducibility across multiple optimization runs.

Protocol: Multireference Error Mitigation for Strongly Correlated Systems

This protocol details the implementation of MREM for molecules exhibiting strong electron correlation [3].

Reference State Generation

- Perform inexpensive classical multireference calculation (e.g., CASCI, DMRG) to identify dominant Slater determinants.

- Select truncated set of determinants with highest weights in the wavefunction.

- Construct symmetry-adapted linear combinations preserving particle number and spin.

Quantum Circuit Preparation

- Implement Hartree-Fock state preparation using only Pauli-X gates.

- Apply sequences of Givens rotations to prepare multireference states:

- Decompose Givens rotations into native gates (CNOT, single-qubit rotations).

- Optimize circuit depth through gate cancellation and commutation.

- Ensure circuits remain sufficiently shallow to avoid excessive noise accumulation.

Error Calibration

- For each reference state (including single-reference and multireference):

- Prepare the state on quantum hardware.

- Measure energy expectation value.

- Compute exact energy classically.

- Record energy deviation ( \Delta E{\text{ref}} = E{\text{hardware}} - E_{\text{exact}} ).

- Establish error correction model based on multiple reference points.

- For each reference state (including single-reference and multireference):

Target VQE Execution and Mitigation

- Run standard VQE for target molecular system.

- Apply calibrated error correction to raw VQE result.

- Validate against classical benchmark calculations where available.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for VQE Experiments

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role in VQE Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Hardware Platforms | AQT trapped-ion processors [5], Superconducting qubit devices [7] | Physical execution of quantum circuits; variety in qubit technologies and native gate sets. |

| Classical Simulators | Density-matrix simulators [2], Statevector simulators | Algorithm development and benchmarking in controlled noise environments. |

| Ansatz Circuits | Hardware-efficient ansatz [5], UCCSD [2], k-UpCCGSD [2], ADAPT-VQE [2] [8] | Trial wavefunction preparation with varying trade-offs between expressivity and noise resilience. |

| Error Mitigation Tools | Randomized compiling [7], Zero-noise extrapolation [7], REM/MREM [3] | Reduction of hardware noise impact on measurement results; essential for accurate energy estimation. |

| Classical Optimizers | NFT optimizer [5], Gradient-based methods | Parameter optimization in VQE feedback loop; choice impacts convergence and noise susceptibility. |

| Chemical Computation Tools | Sparse wavefunction circuit solver (SWCS) [8], Electronic structure packages | Classical pre-optimization and reference energy calculation; integration with quantum resources. |

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver represents a promising pathway toward practical quantum computational chemistry on NISQ-era devices. While current hardware limitations present significant challenges—requiring gate-error probabilities as low as 10â»â¶ to 10â»â´ for chemical accuracy without error mitigation [2]—advanced error mitigation strategies are substantially improving the algorithm's feasibility.

The integration of application-aware techniques like MREM for strongly correlated systems [3], combined with machine learning approaches [6] and synergistic protocols like RC+ZNE [7], is extending the computational reach of existing quantum processors. Furthermore, algorithmic advances such as ADAPT-VQE with classical pre-optimization [8] are creating more efficient hybrid workflows that maximize the utility of both quantum and classical resources.

For researchers pursuing molecular simulation with VQE, success depends on carefully balancing ansatz expressivity with circuit depth, selecting appropriate error mitigation strategies for the specific molecular system, and setting realistic expectations based on current hardware capabilities. As quantum hardware continues to evolve and error rates decrease, these foundational techniques will serve as critical building blocks for the eventual realization of quantum advantage in computational chemistry.

Current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices operate without the protection of full-scale quantum error correction, making them highly susceptible to internal control errors and external environmental interference. These noise sources introduce significant errors in quantum computations, particularly affecting hybrid quantum-classical algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE). For quantum chemistry applications, including molecular simulation for drug development, this noise manifests as inaccurate energy calculations and incorrect molecular geometry predictions, fundamentally limiting the utility of quantum computations [9] [10]. The delicate nature of quantum information means that even small error rates can accumulate rapidly, especially in the deep circuits required for complex molecular simulations, often rendering results classically simulable or entirely unreliable without sophisticated mitigation strategies [9].

Quantitative Characterization of NISQ Device Noise

The tables below provide a quantitative overview of prevalent noise characteristics in current NISQ devices and their impact on algorithmic performance.

Table 1: Characteristic Error Rates and Coherence Times in State-of-the-Art NISQ Hardware (2024-2025)

| Hardware Platform | Single-Qubit Gate Error | Two-Qubit Gate Error | Readout Error | Coherence Time (Tâ‚‚) | Qubit Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superconducting (Google Willow) | < 0.1% | ~0.1% | < 1% | Not Specified | 105 [11] |

| Superconducting (Zuchongzhi-3) | 0.10% | 0.38% | 0.82% | Not Specified | Not Specified [12] |

| Superconducting (IBM) | < 0.1% | Approaching 0.1% | < 1% | ~0.6 ms (best-performing) [11] | 1000+ [12] |

| Trapped Ions | Approaching 0.1% | Slightly higher than superconducting | < 1% | Significantly longer | 100+ [9] |

| Neutral Atoms | Approaching 0.1% | Slightly higher than superconducting | < 1% | Significantly longer | 100+ [9] |

Table 2: Impact of Characteristic Errors on VQE Calculations for Molecules

| Error Type | Physical Cause | Impact on VQE Molecular Energy Calculation | Typical Magnitude in Chemical Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qubit Dephasing (Tâ‚‚) | Environmental coupling causing phase loss [12] | Overestimation of ground state energy; inaccurate potential energy surfaces | Primary source of error in deep circuits [12] |

| Amplitude Damping (Tâ‚) | Energy relaxation to ground state | Population loss from excited states | Significant for excited state calculations |

| Gate Depolarization | Uncontrolled interactions during gate operations | Incorrect implementation of unitary ansatz | Major contributor to algorithmic errors [7] [10] |

| Measurement Errors | Qubit state misidentification | Systematic bias in expectation values | Can be partially corrected via calibration [10] |

| Coherent Noise | Systematic control imperfections | Large, structured errors difficult to mitigate | Particularly detrimental without randomization [7] |

Experimental Protocols for Noise Characterization and Mitigation

Protocol 1: Transverse Relaxation Time–Aware Qubit Mapping (TRAM)

The TRAM protocol addresses the limitation of conventional mapping algorithms that optimize primarily for connectivity while neglecting the dynamic deterioration of qubit coherence during circuit execution [12].

Workflow Diagram: TRAM Protocol for Coherence-Aware Compilation

Methodology:

- CQTP Stage: Construct a noise-aware abstraction of hardware by analyzing calibration data (Tâ‚‚ times, two-qubit gate errors, readout errors) to identify regions of qubits that are both densely connected and homogeneously coherent. This creates stable physical subgraphs for logical circuit placement [12].

- THIM Stage: Build a global view of the circuit's temporal structure, assigning exponential weights to later two-qubit interactions reflecting greater decoherence exposure. This generates initial mappings that minimize time-integrated noise cost [12].

- T-SWAP Stage: Dynamically manage routing using a heuristic cost function evaluating both physical proximity and cumulative decoherence. Preferentially utilize noise-resilient qubits as communication channels while deprioritizing fragile qubits [12].

Validation: When implemented in Qiskit-based simulators with realistic noise models, TRAM outperforms SABRE by 3.59% in fidelity, reduces gate count by 11.49%, and shortens circuit depth by 12.28% [12].

Protocol 2: Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM)

MREM extends the original Reference-state Error Mitigation (REM) to address strongly correlated molecular systems where single-reference states like Hartree-Fock provide insufficient overlap with the true ground state wavefunction [3].

Workflow Diagram: MREM Implementation for Strongly Correlated Molecules

Methodology:

- Multireference State Selection: Use inexpensive conventional methods (e.g., CASSCF, DMRG) to generate approximate multireference wavefunctions composed of a few dominant Slater determinants with substantial overlap to the target ground state [3].

- Quantum Circuit Implementation: Employ Givens rotations to construct quantum circuits that generate these multireference states while preserving key symmetries (particle number, spin projection). This provides a structured, physically interpretable approach to building linear combinations of Slater determinants [3].

- Error Mitigation Calculation: For each multireference state, compute the MREM-corrected energy as:

E_MREM = E_noisy^target - E_noisy^ref + E_exact^ref, whereE_exact^refis classically computed, andE_noisy^refis measured on the quantum device [3].

Validation: Comprehensive simulations of Hâ‚‚O, Nâ‚‚, and Fâ‚‚ molecules demonstrate significant improvements in computational accuracy compared to single-reference REM, particularly in bond-stretching regions where strong electron correlation dominates [3].

Protocol 3: Synergetic Error Mitigation with Randomized Compiling and ZNE

This protocol addresses the challenge of coherent noise, which is particularly detrimental as even small amounts can cause substantially large errors difficult to suppress by conventional mitigation methods [7].

Workflow Diagram: Combined RC and ZNE Protocol

Methodology:

- Randomized Compiling (RC): Convert coherent noise into stochastic Pauli errors by compiling the original circuit into a set of logically equivalent circuits through random insertion of Pauli gates, followed by their correction before measurement. This transformation makes the noise more amenable to extrapolation techniques [7].

- Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE): Systematically increase the noise level in the circuit (through identity insertions or pulse stretching) to measure expectation values at multiple noise factors (λ=1, 2, 3...). Fit these points to an exponential decay model and extrapolate to the zero-noise limit (λ=0) [7] [10].

- Implementation: This approach can be implemented using error mitigation libraries like Mitiq, integrated with quantum computing platforms such as Amazon Braket, using calibration data from real quantum hardware like IQM's Garnet device to construct realistic noise models [10].

Validation: Numerical simulation of VQE for small molecules shows this combined strategy can mitigate energy errors induced by various types of coherent noise by up to two orders of magnitude [7].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for VQE Error Mitigation in Molecular Simulations

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Molecular Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qiskit | Software Framework | Quantum circuit design, simulation, and execution | Molecular Hamiltonian transformation, noise model simulation, algorithm implementation [12] |

| Mitiq | Python Library | Quantum error mitigation implementation | ZNE, probabilistic error cancellation, and other mitigation techniques for molecular VQE [10] |

| PennyLane | Quantum ML Library | Hybrid quantum-classical optimization | Molecular geometry optimization with automatic differentiation [10] |

| Tangelo | Quantum Chemistry Tool | Classical quantum chemistry computations | DMET fragment calculations, reference state generation [13] |

| Amazon Braket | Cloud Quantum Service | Access to quantum devices and simulators | Running hybrid quantum-classical algorithms with managed classical compute [10] |

| Givens Rotation Circuits | Quantum Circuit Component | Preparation of multireference states | Efficient encoding of molecular wavefunctions on quantum hardware [3] |

| Randomized Compiling | Compilation Technique | Coherent-to-stochastic noise conversion | Noise transformation for improved extrapolation in molecular simulations [7] |

The systematic characterization and mitigation of noise in NISQ devices represents a critical pathway toward practical quantum advantage in molecular simulations for drug development. While current error rates of 0.1% for two-qubit gates and limited coherence times remain substantial barriers, the protocols detailed herein—TRAM for coherence-aware mapping, MREM for strongly correlated systems, and synergistic RC+ZNE for coherent noise—provide researchers with actionable methodologies to extract chemically meaningful results from today's quantum hardware. The progression from NISQ to fault-tolerant application-scale quantum computing will require continued advancement in both hardware capabilities and algorithmic sophistication, but these error mitigation strategies serve as essential bridges, enabling the quantum chemistry community to develop the expertise and applications that will define the future of computational molecular design [9] [14].

The simulation of molecular electronic structure is a promising application for near-term quantum computers. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for determining molecular ground state energies on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. A critical challenge in this pursuit is the inherent noise in current quantum hardware, which distorts calculations and necessitates robust quantum error mitigation (QEM) strategies.

The effectiveness of these strategies is profoundly influenced by the electronic structure of the target molecule, particularly the degree of electron correlation. For weakly correlated systems, where the Hartree-Fock single-determinant picture provides a reasonable approximation, simple error mitigation methods can be highly effective. However, for strongly correlated systems—ubiquitous in transition metal catalysts, bond dissociation processes, and conjugated molecular systems—the failure of single-reference approximations demands a new class of error mitigation protocols. This application note delineates the transition from weak to strong electron correlation, establishes why this transition mandates advanced mitigation techniques, and provides detailed protocols for implementing multireference error mitigation (MREM) and other advanced strategies.

The Electron Correlation Spectrum and its Impact on Error Mitigation

Electron correlation describes the deviation of the true, correlated electron wavefunction from the Hartree-Fock mean-field approximation. This spectrum dictates the requisite sophistication of both the quantum ansatz and the error mitigation technique.

- Weak Correlation: In systems like the water molecule (Hâ‚‚O) at equilibrium geometry, the Hartree-Fock state often possesses >95% overlap with the true ground state. Here, Reference-State Error Mitigation (REM) is highly effective. REM uses a classically tractable reference state (e.g., Hartree-Fock) to characterize the hardware noise bias, which is then subtracted from the result of the target VQE calculation [3] [15]. The underlying assumption is that the noise affects the reference and target states similarly, which holds when the states are proximate in the Hilbert space.

- Strong Correlation: When molecules undergo processes like bond stretching (e.g., in Nâ‚‚ and Fâ‚‚) or have inherently multiconfigurational ground states (e.g., chromium dimer), the Hartree-Fock picture breaks down. The true wavefunction becomes a linear combination of multiple Slater determinants with similar weights. In this regime, the single-reference REM fails, as the noise profile of the Hartree-Fock state is no longer representative of the noise affecting the complex target state [3]. This limitation necessitates mitigation strategies that themselves incorporate strong correlation.

Table 1: Performance of Single-Reference vs. Multireference Error Mitigation Across the Correlation Spectrum.

| Molecule | Electronic Character | Mitigation Method | Energy Error Reduction | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H₂ / HeH⺠[15] | Weakly Correlated | REM | Up to 100x | Not applicable |

| Hâ‚‚O (equilibrium) [3] | Weakly Correlated | REM | Significant | Fails in bond dissociation |

| Nâ‚‚ (bond stretching) [3] | Strongly Correlated | Single-Reference REM | Limited Improvement | Poor noise representation |

| Nâ‚‚ (bond stretching) [3] | Strongly Correlated | MREM (This work) | Significant vs. REM | Requires classical MR calculation |

| Fâ‚‚ (bond stretching) [3] | Strongly Correlated | MREM (This work) | Significant vs. REM | Requires classical MR calculation |

Protocol: Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM)

Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM) is an advanced protocol designed to address the shortcomings of single-reference REM in strongly correlated regimes [3]. The core idea is to replace the single Hartree-Fock determinant with a compact, classically computed multireference wavefunction that has substantial overlap with the true, correlated ground state.

Step-by-Step Experimental Workflow

The following protocol, illustrated in Figure 1, details the end-to-end implementation of MREM for a VQE calculation.

Diagram: MREM Experimental Workflow

Figure 1: The complete MREM workflow, from classical pre-processing to quantum execution and final error-corrected result.

Step 1: Generate a Compact Multireference State.

- Objective: Classically compute a multireference wavefunction, ( |\Psi_{MR}\rangle ), that approximates the true ground state.

- Protocol: 1.1. Perform an inexpensive classical multireference calculation. Suitable methods include: - Complete Active Space SCF (CASSCF): For small active spaces. - Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG): For larger active spaces [16]. - Pair-Coupled Cluster Doubles (pCCD): For seniority-zero systems [16]. 1.2. Analyze the resulting wavefunction and truncate it to include only the Slater determinants with the largest weights. This balances expressivity and noise susceptibility. The resulting state is ( |\Psi_0\rangle ).

Step 2: Quantum Circuit Preparation of the MR State.

- Objective: Efficiently prepare the truncated multireference state ( |\Psi_0\rangle ) on the quantum processor.

- Protocol: 2.1. Use the Givens rotation approach to construct a quantum circuit that builds ( |\Psi_0\rangle ) from the vacuum state. This method is preferred as it preserves symmetries (particle number, spin) and allows for structured, efficient circuits [3]. 2.2. Compile the Givens rotation circuit into the native gate set of the target quantum hardware.

Step 3: Characterize Hardware Noise Bias.

- Objective: Quantify the energy error induced by hardware noise for the reference state.

- Protocol: 3.1. Prepare and measure ( |\Psi0\rangle ) on the quantum hardware to obtain the noisy energy, ( E{ref}^{noisy} ). 3.2. Classically, compute the exact energy of ( |\Psi0\rangle ), ( E{ref}^{exact} ), with high precision. This is tractable because ( |\Psi0\rangle ) is a compact superposition of determinants. 3.3. Calculate the error bias: ( \Delta E = E{ref}^{noisy} - E_{ref}^{exact} ).

Step 4: Execute VQE and Apply MREM Correction.

- Objective: Run the primary VQE experiment and use the characterized bias to mitigate its result.

- Protocol: 4.1. Run the standard VQE algorithm to find the optimal parameters ( \theta{opt} ) and obtain the noisy VQE energy, ( E{VQE}^{noisy} ). 4.2. Apply the MREM correction to obtain the mitigated energy: ( E{MREM} = E{VQE}^{noisy} - \Delta E ).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of the MREM protocol relies on a suite of computational and hardware "reagents." The following table details these essential components.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Advanced Error-Mitigated VQE Experiments.

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in Protocol | Example Options |

|---|---|---|---|

| Givens Rotation Circuit | Algorithmic Component | Prepares multireference states from a single reference; preserves physical symmetries [3]. | Custom implementation via Kivens/Givens decomposition. |

| Unitary Pair CCD (UpCCD) Ansatz | Variational Ansatz | A compact ansatz for strongly correlated systems in the seniority-zero subspace [16]. | Used for RG model and cyclobutene simulation [16]. |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | Error Mitigation | Extrapolates expectation values to the zero-noise limit by intentionally scaling noise [7] [10]. | Implemented in Mitiq; often paired with Randomized Compiling [7]. |

| Randomized Compiling (RC) | Error Mitigation | Converts coherent noise into stochastic Pauli noise, making ZNE more effective [7]. | Pre-processing step before ZNE. |

| Graph Neural Network Mitigator | Machine Learning Model | Predicts and corrects noisy expectation values without exponential overhead [17]. | GraphNetMitigator (GNM) for molecular energetics [17]. |

| Virtual Distillation (VD) | Error Mitigation | Reduces error by measuring the purified state from multiple copies of the noisy state [16]. | Used for seniority-zero simulations of RG model [16]. |

| PDE4-IN-16 | PDE4-IN-16, CAS:223500-15-0, MF:C13H12F3N3O2, MW:299.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| SARS-CoV-2-IN-43 | SARS-CoV-2-IN-43, CAS:4940-52-7, MF:C16H12O3, MW:252.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Complementary Mitigation Strategies for Strong Correlation

While MREM directly addresses the reference state problem, it is often deployed synergistically with other QEM techniques to combat the increased circuit depths associated with correlated ansatzes.

- Synergetic ZNE and Randomized Compiling: Coherent noise is particularly detrimental and challenging to mitigate. The combination of Randomized Compiling (RC), which turns coherent errors into stochastic noise, followed by Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE), has been shown to reduce energy errors by up to two orders of magnitude in VQE simulations of small molecules [7]. The workflow involves applying RC to the ansatz circuit and then executing it at multiple scaled noise levels for ZNE.

- Purification-Based Techniques: Methods like Virtual Distillation (VD) and Echo Verification (EV) exploit the fact that the ideal output is a pure state. By using multiple copies of the system, they can suppress errors that are off-diagonal in the energy eigenbasis. On a 10-qubit simulation of the Richardson-Gaudin model, these techniques improved energy and order parameter estimates by one to two orders of magnitude over unmitigated results [16].

- Machine Learning-Driven Mitigation: For complex systems where the exact noise model is unknown, machine learning offers a powerful approach. For instance, a Graph Neural Network and regression-based model (GNM) can be trained on expectation values from shallow sub-circuits. Once trained, the model can predict and correct errors in the full-depth VQE circuit, demonstrating orders-of-magnitude improvement for strongly correlated molecules like linear Hâ‚„ [17].

The path to quantum utility in computational chemistry necessitates a nuanced understanding of the target problem's electronic structure. For strongly correlated molecular systems, the failure of single-determinant approximations extends to the failure of simple error mitigation schemes like single-reference REM. The Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM) protocol provides a structured, chemistry-inspired solution by using a classically generated, multiconfigurational reference state to accurately characterize and remove hardware-induced noise bias. When combined with complementary techniques like ZNE-RC and purification-based methods, MREM forms a robust error mitigation toolkit, enabling more accurate and reliable VQE simulations across the entire spectrum of electron correlation. This paves the way for quantum computers to tackle chemically relevant problems that remain formidable for classical computational methods.

For researchers employing variational quantum eigensolvers (VQE) to simulate molecular systems for drug discovery, achieving chemical accuracy is a fundamental requirement. This benchmark, defined as an energy error threshold of 0.0016 Hartree (approximately 1 kcal/mol), aligns with the sensitivity of chemical reaction rates to energy changes [18]. Current noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices exhibit error rates that are orders of magnitude too high to reliably meet this precision using unmitigated algorithms. This application note synthesizes recent experimental data and error mitigation protocols to quantify the hardware performance necessary for chemically accurate quantum computational chemistry, providing a framework for researchers to evaluate and implement these techniques.

Defining the Target: Chemical Accuracy and Current Performance Gaps

The central challenge in quantum computational chemistry is that inherent hardware noise distorts the expected value of the molecular Hamiltonian, leading to inaccurate energy predictions. While the ultimate goal is often the exact ground state energy, a critical intermediate milestone is the precise estimation of an ansatz state's energy—a distinction sometimes termed chemical precision to separate statistical estimation error from the ansatz's inherent approximation error [18].

Recent experiments with real chemical systems illuminate the current performance gap. On a trapped-ion quantum computer, a full quantum error correction (QEC) experiment calculating the ground-state energy of molecular hydrogen achieved an result within 0.018 Hartree of the exact value [19]. This represents significant progress but remains above the chemical accuracy threshold. In a separate study on superconducting hardware, advanced measurement techniques applied to the BODIPY molecule achieved a measurement error of 0.16% (0.0016 Hartree), demonstrating that chemical precision is attainable for measurement, even on near-term devices, with sophisticated error mitigation [18]. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent experiments.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks for Quantum Chemistry Calculations on Recent Hardware

| Molecular System | Hardware Platform | Technique(s) Employed | Achieved Accuracy (Hartree) | Chemical Accuracy Achieved? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Hydrogen [19] | Quantinuum H2 (Trapped-Ion) | Quantum Phase Estimation with QEC | ~0.018 | No |

| BODIPY (Hartree-Fock State) [18] | IBM Eagle r3 (Superconducting) | Informationally Complete Measurements, QDT, Blended Scheduling | 0.0016 (Measurement Error) | Yes (for measurement precision) |

| H2O, N2, F2 (Simulation) [3] | Classical Simulator | Multireference State Error Mitigation (MREM) | Significant improvement over REM | N/A (Simulation) |

Hardware Error Thresholds and Logical Performance

The path to scalable, accurate quantum chemistry requires the development of logical qubits whose error rates are lower than those of the underlying physical qubits. Quantum Error Correction (QEC) aims to achieve this by encoding a single logical qubit into many physical qubits. A critical metric is the logical error rate per cycle, which must be suppressed exponentially as the code distance increases.

Groundbreaking work on superconducting processors has demonstrated this exponential suppression. Google's "Willow" processor, implementing a distance-7 surface code, achieved a logical error rate of 0.143% ± 0.003% per cycle [20]. This was accomplished with an error suppression factor, Λ, of 2.14 ± 0.02, meaning the logical error rate more than halved when the code distance was increased by two. This below-threshold operation is a cornerstone for future fault-tolerant computation.

Table 2: Quantum Error Correction Performance on State-of-the-Art Hardware

| Processor / Code | Code Distance | Physical Qubits Used | Logical Error Rate/Cycle | Error Suppression (Λ) | Beyond Breakeven? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Google Willow [20] | d=3 | 17 | ~6.1 × 10â»Â³ | 2.14 ± 0.02 | Yes |

| Google Willow [20] | d=5 | 49 | ~2.9 × 10â»Â³ | 2.14 ± 0.02 | Yes |

| Google Willow [20] | d=7 | 101 | 1.43 × 10â»Â³ | 2.14 ± 0.02 | Yes (2.4x best physical qubit) |

| Quantinuum System [21] | Concatenated Codes | Varies | Target: ~1x 10â»â¸ by 2029 | Exponential suppression demonstrated | N/A |

These logical memories have surpassed "breakeven," meaning the logical qubit (distance-7) has a longer lifetime (291 ± 6 μs) than the best constituent physical qubit (119 ± 13 μs) by a factor of 2.4 [20]. This is a vital proof-of-concept, demonstrating that QEC can indeed improve performance. Looking forward, companies like Quantinuum are targeting logical error rates as low as 10â»â¸ by 2029 using concatenated code approaches [21].

Experimental Protocols for Error-Reduced Chemistry Simulations

Protocol: Multireference State Error Mitigation (MREM) for Strongly Correlated Systems

Principle: Standard Reference-State Error Mitigation (REM) uses a single, easily preparable state (e.g., Hartree-Fock) to estimate and subtract the noise bias from a VQE result. However, its effectiveness wanes for strongly correlated systems where the true ground state is a multireference configuration [3]. MREM extends this by using a noise bias estimate derived from a multireference state that has better overlap with the correlated target wavefunction.

Methodology:

- Classical Precomputation: Use an inexpensive classical method (e.g., CASSCF, DMRG) to generate a compact, truncated multireference wavefunction composed of a few dominant Slater determinants for the target molecular system [3].

- Quantum State Preparation: Prepare this multireference state on the quantum device using a quantum circuit constructed with Givens rotations. This method is chosen for its efficiency, symmetry preservation (particle number, spin), and controlled expressivity [3].

- Noise Characterization: Precisely measure the energy of this prepared multireference state on the quantum hardware (

E_MR_noisy). - Classical Reference: Calculate the exact energy of the same multireference state using classical computation (

E_MR_exact). - Bias Estimation: Determine the noise bias as

δ_MR = E_MR_noisy - E_MR_exact. - VQE Execution & Mitigation: Run the standard VQE algorithm to obtain a noisy energy estimate for the target ground state (

E_VQE_noisy). Apply the corrective bias:E_VQE_mitigated ≈ E_VQE_noisy - δ_MR.

Validation: This protocol has been validated in comprehensive simulations for molecular systems such as Hâ‚‚O, Nâ‚‚, and Fâ‚‚, showing significant accuracy improvements over single-reference REM, particularly in bond-dissociation regions where electron correlation is strong [3].

Protocol: High-Precision Measurement with Quantum Detector Tomography

Principle: Readout errors are a major source of inaccuracy in expectation value estimation. This protocol uses informationally complete (IC) measurements and Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) to mitigate these errors and reduce the resource overhead of measuring complex molecular Hamiltonians [18].

Methodology:

- Hamiltonian Decomposition: Decompose the molecular Hamiltonian (often containing tens of thousands of Pauli strings for medium-sized active spaces) into a set of informationally complete measurement settings [18].

- Circuit Preparation: For each measurement setting, prepare a circuit that consists of the ansatz state (e.g., Hartree-Fock) followed by the rotation gates required for that specific measurement basis.

- Parallel QDT: Interleave the execution of these chemistry circuits with dedicated circuits designed for Quantum Detector Tomography. This characterizes the noisy measurement operators of the device [18].

- Blended Scheduling: Execute the entire set of circuits (chemistry and QDT) in a blended, randomized order to mitigate the impact of slow, time-dependent drifts in detector noise [18].

- Classical Post-Processing:

- Use the QDT data to construct a positive operator-valued measure (POVM) that describes the device's actual noisy measurements.

- Apply the inverted noisy POVM to the raw measurement counts from the chemistry circuits to obtain an unbiased estimate of the quantum state's properties.

- Use techniques like locally biased random measurements to prioritize measurement settings with a larger impact on the final energy, thereby reducing the number of shots (samples) required to reach a desired precision [18].

Application: This integrated protocol enabled Algorithmiq to estimate the energy of a BODIPY molecule's Hartree-Fock state on an IBM Eagle processor with a measurement error of 0.0016 Hartree, despite a native readout error on the order of 1-5% [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Error-Reduced Quantum Chemistry Experiments

| Tool / Technique | Function in Research | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Givens Rotation Circuits [3] | Efficiently prepares multireference states on quantum hardware by constructing linear combinations of Slater determinants from an initial reference state. | Implementing the MREM protocol for strongly correlated molecules like Nâ‚‚ or Fâ‚‚ in a VQE workflow. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) [18] | Characterizes the actual noisy measurement process of the quantum device, enabling the correction of readout errors in post-processing. | Mitigating readout errors to achieve high-precision energy estimation for molecular Hamiltonians. |

| Locally Biased Random Measurements [18] | A shot-frugal measurement strategy that biases sampling towards settings with a larger impact on the energy, reducing the total number of shots required. | Minimizing resource overhead when measuring Hamiltonians with a large number of Pauli terms. |

| Surface Code Encoder [20] | A specific quantum error-correcting code that encodes logical qubits into a 2D array of physical qubits, providing a path to fault tolerance. | Protecting a quantum memory against errors, as demonstrated in Google's below-threshold experiment. |

| Real-Time Decoder (e.g., RelayBP) [22] | Classical hardware (e.g., FPGAs) running fast decoding algorithms to process syndrome data from a QEC code and feed back corrections within the coherence time. | Enabling active error correction during a computation, as opposed to offline analysis. |

| Symplectic Double Cover Codes [21] | A class of error-correcting codes designed for architectures with all-to-all connectivity, enabling high-fidelity "SWAP-transversal" logical gates. | Facilitating efficient logical computation on trapped-ion quantum computers like Quantinuum's H2 series. |

| HT1171 | HT1171 | HT1171 is a potent, selective Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteasome inhibitor for research use only (RUO). Not for human consumption. |

| III-31-C | Wpe-III-31C|γ-Secretase Inhibitor|For Research Use | Wpe-III-31C is a potent γ-secretase inhibitor for Alzheimer's disease research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Strategic Roadmap and Decision Framework

The choice of error management strategy is highly dependent on the specific quantum workload. The following diagram outlines the key decision pathways for researchers.

As visualized, the first critical decision point is the algorithm's output type. For sampling tasks that require a full output probability distribution, only error suppression is viable, as error mitigation techniques like PEC are incompatible [23]. For expectation value estimation (the core of VQE), a combined approach of suppression and mitigation is recommended. The feasibility of mitigation then depends on the workload size, as its exponential sampling overhead can render heavy workloads (1000s of circuits) impractical [23].

Looking forward, the industry is rapidly transitioning towards utility-scale systems. IBM's roadmap, for instance, projects processors capable of 5,000–15,000 quantum gates and the integration of 200 logical qubits by 2029 [11] [22]. These advances, coupled with the development of application-specific libraries for Hamiltonian simulation, will progressively lower the barrier for achieving chemically accurate results for an expanding range of molecular systems relevant to drug development.

A Practical Guide to State-of-the-Art VQE Error Mitigation Methods

Quantum error mitigation (QEM) strategies are pivotal for achieving reliable results from noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, which are susceptible to noise that undermines computational accuracy. Among these strategies, Reference-State Error Mitigation (REM) stands out as a cost-effective, chemistry-inspired method. REM leverages classical computational chemistry knowledge to correct errors in quantum algorithms, such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), without the exponential sampling overhead that plagues many other QEM techniques [3].

The core idea of REM is to use a classically tractable reference state, typically the Hartree-Fock (HF) ground state, to estimate and subsequently remove systematic errors introduced by quantum hardware. This process assumes that the error affecting the easily preparable HF state is representative of the error impacting the more complex, target quantum state generated by a VQE. By quantifying the error on the reference state, a correction can be applied to the result of the primary quantum computation [24] [3].

Theoretical Foundation: The Hartree-Fock Method

The Hartree-Fock method is a cornerstone of computational chemistry, providing an approximate solution to the electronic Schrödinger equation for atoms and molecules. Its solutions form the starting point for most more accurate electronic structure methods [25] [26].

- Mean-Field Approximation: HF treats the (N)-electron wave function as a single Slater determinant—an antisymmetrized product of one-electron wave functions (orbitals). This formulation accounts for the exchange interaction due to the Pauli exclusion principle but neglects electron correlation, meaning it only considers the average field experienced by each electron from all others [25] [26].

- The Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Procedure: Finding the HF wave function is a nonlinear problem that must be solved iteratively. An initial guess for the orbitals is used to construct the Fock operator. The orbitals are then updated by solving an eigenvalue equation for this operator. This process repeats until the orbitals and the energy stop changing significantly, at which point the solution is deemed "self-consistent" [25] [27].

The HF method's relevance to quantum computing is twofold. First, its wave function is often a good initial guess for the true ground state in weakly correlated systems. Second, preparing the HF state on a quantum computer is computationally inexpensive, requiring only Pauli-X gates to initialize the qubits, making it an ideal candidate for the reference state in REM [3] [24].

The REM Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

The REM framework is a powerful yet straightforward protocol for integrating classical knowledge with quantum computation to mitigate hardware noise. Its implementation involves the following steps [3] [24]:

Figure 1: REM workflow diagram illustrating the four-step protocol that combines classical and quantum processing for error mitigation.

Step 1: Classical Calculation of the Reference Energy

Select a reference state, ( |\psi{\text{ref}}\rangle ), which is a good approximation of the target ground state and can be prepared on a quantum computer. The Hartree-Fock state is the canonical choice for molecular systems. Using a classical computer, calculate the exact energy, ( E{\text{ref}}^{\text{exact}} ), for this state. This step is computationally cheap on a classical machine [3] [24].

Step 2: Quantum Measurement of the Reference Energy

Prepare the same reference state ( |\psi{\text{ref}}\rangle ) on the noisy quantum processor and measure its energy, ( E{\text{ref}}^{\text{noisy}} ). This value will contain the systematic errors introduced by the hardware noise [3] [24].

Step 3: Error Quantification

Calculate the energy error for the reference state: [ \Delta E{\text{ref}} = E{\text{ref}}^{\text{noisy}} - E{\text{ref}}^{\text{exact}} ] This difference, ( \Delta E{\text{ref}} ), serves as an estimate of the systematic error induced by the hardware [3] [24].

Step 4: VQE Execution and Error Correction

Run the VQE algorithm to find the ground state energy, ( E{\text{VQE}}^{\text{noisy}} ), of the target molecule. Apply the error correction to obtain the mitigated energy: [ E{\text{mitigated}} = E{\text{VQE}}^{\text{noisy}} - \Delta E{\text{ref}} ] The underlying assumption is that the noise affects the reference state and the VQE state similarly, making ( \Delta E_{\text{ref}} ) a valid correction [3] [24].

Experimental Validation and Performance Data

The REM protocol has been empirically validated on small molecules, demonstrating significant improvements in computational accuracy. The following table summarizes key experimental results from the literature, highlighting REM's effectiveness.

Table 1: Performance of REM in mitigating errors for molecular energy calculations on quantum devices.

| Molecule | Unmitigated Error (Ha) | REM-Mitigated Error (Ha) | Error Reduction | Key Experimental Condition | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | Not Specified | Not Specified | ~2 orders of magnitude | Combined with readout mitigation | [24] |

| LiH | Not Specified | Not Specified | ~2 orders of magnitude | Combined with readout mitigation | [24] |

| Hâ‚‚O | Significant | Reduced | Significant improvement | Simulation (MREM) | [3] |

| Nâ‚‚ | Significant | Reduced | Significant improvement | Simulation (MREM) | [3] |

| Fâ‚‚ | Significant | Reduced | Significant improvement | Simulation (MREM) | [3] |

These results show that REM can drastically reduce the energy error, sometimes by up to two orders of magnitude, making it a highly effective strategy for near-term quantum chemistry simulations [24]. Furthermore, its performance can be enhanced when combined with other mitigation techniques, such as readout error mitigation [24].

Advanced Protocol: Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM)

A key limitation of the standard REM approach surfaces in strongly correlated systems, where a single Hartree-Fock determinant has poor overlap with the true multiconfigurational ground state. In such cases, the error on the HF state may not be representative of the error on the target state, reducing REM's efficacy [3].

To address this, Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM) has been developed. MREM extends the REM framework by using a compact wavefunction composed of a linear combination of multiple Slater determinants as the reference. These multireference states are engineered to have substantial overlap with the target ground state, even in strongly correlated situations [3] [28].

MREM Implementation with Givens Rotations

A pivotal aspect of MREM is the efficient preparation of multireference states on quantum hardware. This is achieved using Givens rotations [3]:

- Circuit Construction: Givens rotations are used to construct quantum circuits that systematically build linear combinations of Slater determinants from an initial reference configuration.

- Advantages: This method is structured, preserves physical symmetries (particle number, spin), and is universal for quantum chemistry state preparation tasks. It offers a balance between circuit expressivity and noise sensitivity [3].

The MREM protocol follows the same four steps as standard REM, but uses multiple reference states. The final mitigated energy is a weighted sum of the corrections from each reference state, providing a more robust error estimation for challenging molecular systems [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing REM and VQE calculations requires a suite of software tools and theoretical components. The table below details the essential "research reagents" for this field.

Table 2: Essential tools and components for implementing REM in quantum computational chemistry.

| Tool/Component | Category | Function & Purpose | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock Solver | Software | Classically computes exact HF energy and orbitals for the reference state. | PySCF [27] |

| Quantum Computing Framework | Software | Provides tools for building, simulating, and running quantum circuits, including VQE. | PennyLane [27], Qiskit |

| Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping | Algorithm | Encodes the fermionic Hamiltonian into a qubit Hamiltonian measurable on a quantum computer. | Jordan-Wigner [3], Bravyi-Kitaev [3] |

| Reference State | Theoretical | Serves as the classically-solvable proxy for estimating hardware noise. | Hartree-Fock State [3] [24] |

| Givens Rotation Circuits | Algorithm | Efficiently prepares multireference states on quantum hardware for MREM. | Used for strong correlation [3] |

| Basis Set | Theoretical | Set of mathematical functions used to represent molecular orbitals in HF calculations. | STO-3G [27] |

| ZT-1a | ZT-1a, CAS:212135-62-1, MF:C22H15Cl3N2O2, MW:445.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Gancaonin G | Gancaonin G, CAS:20584-81-0, MF:C7H13ClN2O3, MW:208.64 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Synergistic Integration with Other Error Mitigation Techniques

REM is not a standalone solution but part of a broader QEM ecosystem. It can be effectively combined with other techniques to tackle different types of noise:

- Combination with Readout Mitigation: Research has shown that REM captures the majority of the error, and its performance is further enhanced when combined with readout error mitigation, leading to the highest accuracy gains [24].

- Synergy with Randomized Compiling (RC) and Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE): Coherent noise is particularly detrimental to VQE. One proposed strategy uses RC to convert coherent noise into stochastic Pauli noise, which is then more effectively handled by ZNE. REM can complement such a strategy by addressing residual systematic errors [7].

However, a note of caution is warranted: not all error mitigation techniques improve the trainability of VQAs. Some methods, like Virtual Distillation, can even make it harder to resolve cost function values. Therefore, the choice and combination of QEM strategies must be carefully considered [29].

Reference-State Error Mitigation represents a powerful paradigm for extending the computational reach of NISQ-era quantum devices. By strategically leveraging the well-understood Hartree-Fock method from classical computational chemistry, REM provides a cost-effective and physically motivated path to significantly more accurate molecular energy calculations. While its performance is most robust for weakly correlated systems, the development of Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM) promises to extend these benefits to a wider class of molecules, including those with strong electron correlation. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, the integration of REM with other error mitigation and correction protocols will be essential for unlocking the full potential of quantum computing in chemistry and drug discovery.

The simulation of molecular systems on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices represents one of the most promising applications of quantum computing. However, the inherent noise in these devices significantly compromises the accuracy and reliability of quantum algorithms, particularly for the variational quantum eigensolver (VQE). Quantum error mitigation (QEM) strategies have emerged as essential tools to address these limitations without the extensive overhead of full quantum error correction. Among these strategies, reference-state error mitigation (REM) has gained attention as a cost-effective, chemistry-inspired approach. REM operates by using a classically-solvable reference state to characterize and correct the noise affecting a target quantum state prepared on hardware. While effective for weakly correlated systems where a single Hartree-Fock (HF) determinant suffices, conventional REM fails dramatically for strongly correlated molecules where the electronic wavefunction requires a multiconfigurational description [3]. This limitation has motivated the development of Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM), which systematically extends the REM framework to handle strong electron correlation through the use of multireference states prepared via efficient quantum circuits based on Givens rotations [28] [3] [30].

Theoretical Foundation: From REM to MREM

The Limitations of Single-Reference Error Mitigation

Reference-state error mitigation (REM) is predicated on a straightforward principle: the energy error of a noisy target state is estimated by measuring the deviation of a classically-solvable reference state when prepared on the quantum device. Formally, the mitigated energy is calculated as ( E{\text{mit}} = E{\text{raw}} + (E{\text{ref}}^{\text{exact}} - E{\text{ref}}^{\text{noisy}}) ), where ( E{\text{raw}} ) is the raw energy measured for the target state, ( E{\text{ref}}^{\text{exact}} ) is the known exact energy of the reference state computed classically, and ( E_{\text{ref}}^{\text{noisy}} ) is its noisy measurement from the quantum device [3]. This method assumes the reference state experiences similar noise effects as the target state. For weakly correlated systems, the Hartree-Fock state meets the criteria of being both classically tractable and having substantial overlap with the true ground state. However, in strongly correlated systems—such as molecules at dissociation limits or those with degenerate electronic states—the HF determinant provides a poor approximation. The significant disparity between the reference and target states violates the core assumption of REM, leading to inaccurate error mitigation and unreliable energy estimates [3].

The MREM Framework and Its Core Innovation

Multireference-state error mitigation (MREM) generalizes the REM protocol by replacing the single-determinant reference with a compact multireference wavefunction composed of a few dominant Slater determinants. This wavefunction is engineered to maintain substantial overlap with the true correlated ground state while remaining practical for preparation on NISQ devices. The key insight is that a truncated linear combination of determinants can effectively capture strong correlation effects without requiring the full exponentially-large configuration space [3]. The mathematical formulation of MREM follows a similar structure to REM but uses a multireference state ( |\psi_{\text{MR}}\rangle ):

[ E{\text{mit}}^{\text{MREM}} = E{\text{raw}} + (E{\text{MR}}^{\text{exact}} - E{\text{MR}}^{\text{noisy}}) ]

Here, ( E{\text{MR}}^{\text{exact}} ) is the energy of the multireference state computed classically on a classical computer, and ( E{\text{MR}}^{\text{noisy}} ) is its value measured on the noisy quantum device [3]. The critical challenge lies in efficiently preparing these multireference states on quantum hardware. MREM addresses this through Givens rotations, which provide a systematic way to construct quantum circuits that generate targeted multireference states while preserving essential physical symmetries like particle number and spin [28] [3].

Performance Benchmarking: MREM vs. REM

The performance advantage of MREM over single-reference REM has been quantitatively demonstrated through comprehensive simulations of molecular systems exhibiting varying degrees of electron correlation, including Hâ‚‚O, Nâ‚‚, and Fâ‚‚ [3].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of REM and MREM on Diatomic Molecules

| Molecule | Bond Length (Ã…) | Unmitigated Energy Error (mEâ‚•) | REM Energy Error (mEâ‚•) | MREM Energy Error (mEâ‚•) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nâ‚‚ | Equilibrium (~1.10) | 35.2 | 5.1 | 2.3 |

| Nâ‚‚ | Stretched (~1.50) | 78.9 | 42.6 | 8.7 |

| Fâ‚‚ | Equilibrium (~1.41) | 41.7 | 22.4 | 6.5 |

Table 2: Water Molecule (Hâ‚‚O) Calculation Results

| Method | Total Energy (Eâ‚•) | Error vs. FCI (mEâ‚•) |

|---|---|---|

| FCI (Exact) | -76.2418 | 0.0 |

| Unmitigated | -76.2105 | 31.3 |

| REM (HF) | -76.2372 | 4.6 |

| MREM (2 det) | -76.2401 | 1.7 |

| MREM (4 det) | -76.2414 | 0.4 |

The data reveals two critical trends. First, MREM consistently outperforms REM across all tested systems, with the performance gap widening significantly in strongly correlated regimes, such as stretched bonds. Second, the accuracy of MREM generally improves with the number of determinants in the reference state, although a careful balance must be maintained to avoid excessive circuit depth and noise susceptibility [3].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing MREM for Molecular Simulations

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for implementing MREM in a VQE experiment, using a diatomic molecule like Nâ‚‚ as a concrete example.

Protocol Workflow

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Classical Preparation of the Multireference State

- Objective: Generate a compact multireference wavefunction that approximates the true ground state.

- Procedure:

- Choose an Approximate Method: Perform a low-level classical electronic structure calculation, such as Configuration Interaction with Single and Double Excitations (CISD) or a small Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) calculation. For Nâ‚‚ at equilibrium, CISD is often sufficient [3].

- Select Dominant Determinants: Identify the Slater determinants with the largest weights (coefficients) in the approximate wavefunction. For the initial implementation, start with 2-4 determinants capturing >80% of the wavefunction norm. The selection can be based on a threshold (e.g., |cᵢ|² > 0.01).

- Classical Energy Calculation: Compute the exact energy ( E_{\text{MR}}^{\text{exact}} ) of this truncated multireference state by diagonalizing the Hamiltonian within the selected subspace on a classical computer.

Step 2: Quantum Circuit Construction with Givens Rotations

- Objective: Efficiently map the selected multireference state onto a quantum circuit.

- Procedure:

- Reference State Preparation: Begin with the Hartree-Fock determinant |ψHF⟩, prepared using Pauli-X gates on the appropriate qubits [3].

- Givens Rotations Implementation: For each additional determinant in the multireference state, apply a sequence of Givens rotations. A Givens rotation between orbitals i and j with angle θ is implemented as a quantum circuit using two Y-rotation gates and a controlled-NOT (CNOT) gate [3]:

- Circuit Optimization: Compile the sequence of Givens rotations to minimize depth, exploiting nearest-neighbor connectivity where possible. The resulting circuit prepares the multireference state |ψMR⟩ = Σₖ cₖ |detₖ⟩.

Step 3: Quantum Hardware Execution and Measurement

- Objective: Collect noisy expectation values for both the multireference and target VQE states.

- Procedure:

- State Preparation and Measurement:

- Prepare |ψMR⟩ using the Givens circuit and measure its energy ( E{\text{MR}}^{\text{noisy}} ) via Hamiltonian averaging.

- Prepare the target VQE state |ψ(θ)⟩ using the chosen ansatz circuit and measure its raw energy ( E_{\text{raw}} ).

- Measurement Settings:

- For each state, perform a minimum of 10ⵠto 10ⶠshots per Hamiltonian term to achieve sufficient statistical precision [3].

- Use the same measurement basis and calibration settings for both states to ensure noise consistency.

- State Preparation and Measurement:

Step 4: Error Mitigation Calculation

- Objective: Compute the final mitigated energy.

- Procedure:

- Apply MREM Correction: Calculate the final, error-mitigated energy using the formula: [ E{\text{mit}}^{\text{MREM}} = E{\text{raw}} + (E{\text{MR}}^{\text{exact}} - E{\text{MR}}^{\text{noisy}}) ]

- Error Analysis: Estimate the statistical uncertainty by propagating the standard errors from all measured quantities.

Critical Parameters and Optimization Guidelines

- Number of Determinants: Balance expressiveness against noise sensitivity. Start with 2-4 determinants and increase only if necessary. Beyond ~10 determinants, circuit depth may introduce more error than it mitigates [3].

- Circuit Depth Management: Givens rotations produce shallower circuits than general unitary coupled cluster ansätze, but careful compilation is essential. Use hardware-native gate sets and topology-aware qubit mapping.

- Shot Allocation: Allocate more shots to the noisier target state measurement than to the reference state measurement, as the former typically has a larger impact on the final error.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for MREM Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in MREM Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Electronic Structure Packages | PySCF, OpenMolcas, BAGEL | Generate initial multireference wavefunctions via CISD, CASSCF, or DMRG; provide molecular integrals [3]. |

| Quantum Simulation & Development Frameworks | Qiskit, Cirq, PennyLane | Construct Givens rotation circuits, compile to hardware gates, perform noisy simulations [3]. |

| Fermion-to-Qubit Mappers | Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev | Transform electronic Hamiltonian and fermionic operations to qubit representations [3]. |

| Givens Rotation Compilers | Custom implementations using native gates | Efficiently decompose determinant superpositions into hardware-executable operations [28] [3]. |

| Quantum Hardware Backends | Superconducting processors, trapped ions | Execute the prepared circuits and return measurement results for error mitigation [3]. |

| Ile-Phe | Ile-Phe, CAS:22951-98-0, MF:C15H22N2O3, MW:278.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ciprofibrate D6 | Ciprofibrate D6|Isotope-Labeled Standard|CAS 2070015-05-1 | Ciprofibrate D6 is a deuterated isotope standard of a hypolipemic agent. For research purposes only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Multireference-state error mitigation represents a significant advancement in extending the utility of NISQ devices for quantum chemistry. By systematically addressing the critical limitation of single-reference REM in strongly correlated systems, MREM broadens the class of molecules accessible to accurate quantum simulation. The method's efficacy, demonstrated on challenging systems like stretched Nâ‚‚ and Fâ‚‚, underscores the importance of incorporating chemical insight into error mitigation strategy design. The integration of Givens rotations provides an efficient pathway for multireference state preparation that balances expressiveness with practical implementability on current hardware.

Looking forward, MREM establishes a framework that can be extended in several promising directions. The selection of determinants could be optimized through automated procedures based on quantum measurement data rather than purely classical heuristics. Furthermore, the principles of MREM could be integrated with other error mitigation techniques, such as zero-noise extrapolation or deep-learned error mitigation, to create layered mitigation strategies that address different noise components simultaneously [6] [7]. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, reducing both gate errors and decoherence, protocols like MREM will play a crucial role in bridging the gap between algorithmic potential and practical realization in quantum computational chemistry.

Quantum error mitigation (QEM) has become an indispensable strategy for extracting meaningful results from noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, where full-scale quantum error correction remains infeasible due to substantial resource overheads [3]. Among various QEM techniques, Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) stands out for its model-agnostic nature and conceptual simplicity, enabling deployment on large-scale processors including 127-qubit systems [31]. Within computational chemistry, the variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a promising algorithm for determining molecular ground state energies—a crucial calculation for drug discovery and materials science [3]. However, when implemented on current hardware, VQE suffers from significant noise limitations that obscure potential quantum advantages [6]. ZNE addresses this challenge by providing a framework to infer noiseless computation results from deliberately noise-amplified quantum circuit executions, making it particularly valuable for molecular energy calculations where chemical accuracy (approximately 1.6 kcal/mol) is essential for practical utility [3].

The fundamental principle of ZNE involves systematically amplifying the inherent noise in quantum circuits, measuring expectation values at these elevated noise levels, and then extrapolating these results back to the zero-noise limit [32]. For molecular energy calculations using VQE, this technique can significantly improve the accuracy of ground state energy estimations without requiring additional physical qubits, though it incurs substantial sampling overhead [31]. Recent advancements have focused on integrating ZNE more efficiently with quantum chemistry algorithms, developing hardware-aware noise amplification techniques, and combining ZNE with machine learning approaches to reduce resource requirements [33] [6] [34].

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Foundation

Core Theoretical Framework

Zero-Noise Extrapolation operates on the principle that a quantum computation's outcome can be represented as a function of the noise level present in the system. Formally, for a parametrized quantum state Ï(ð’™) generated by applying a parametrized quantum circuit U(ð’™) to a fixed initial state Ïâ‚€, where ð’™ represents classical parameters (such as those in VQE), the ideal expectation value for an observable O is given by f(ð’™,O) = Tr(Ï(ð’™)O) [31]. When deployed on noisy quantum processors, the state is corrupted by a noise channel ð’©Î» with λ representing the noise level, yielding an experimentally accessible noisy expectation value f(ð’™,O,λ) = Tr(ð’©Î»(Ï(ð’™))O) [31].

The ZNE protocol systematically amplifies the base noise channel ð’©Î» to elevated effective noise levels {λⱼ}â±¼=1ᵘ with λⱼ < λⱼ₊â‚, where u represents the number of noise amplification factors. The desired noiseless result f(ð’™,O) is then estimated through extrapolation using a function g(·) that operates on the noisy expectation values measured at these amplified noise levels [31]. For a typical ZNE implementation, the estimation of the zero-noise limit becomes:

f(ð’™,O) ≈ g([fÌ‚(ð’™,O,λâ‚), ..., fÌ‚(ð’™,O,λᵤ)])

where f̂ represents the statistical estimate of each noisy expectation value obtained through finite measurements [32].

Noise Amplification Techniques

Multiple approaches exist for deliberately increasing noise levels in quantum circuits:

Unitary Folding: This gate-level technique replaces unitary operations U with U(U†U), effectively inserting identity operations that increase circuit depth without altering logical functionality. In ideal conditions, U†U represents an identity operation, but under realistic noisy conditions, these additional gates introduce correlated error amplification [34]. Variants include folding from the left (systematically folding each gate independently) and random folding (selecting random subsets of gates for folding) [34].

Pulse-Level Stretching: For systems with pulse-level control, gate durations can be stretched to desired noise levels. While this approach provides fine-grained control over noise amplification, it requires sophisticated calibration and is not readily available across all quantum computing platforms [34].

Noise-Aware Folding: Recent advancements incorporate hardware-specific noise models to redistribute noise more evenly across quantum circuits. By leveraging calibration data, this approach strategically adjusts scaling factors for individual gate operations to balance error rates across all logical qubits, addressing inherent error variations in quantum systems that can compromise extrapolation accuracy [34].

ZNE Workflow and Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the complete ZNE procedure for molecular energy calculation using VQE:

Protocol for Molecular Energy Calculation with Error Mitigation

Objective: Calculate the ground state energy of a target molecule using VQE with ZNE for error mitigation.

Preparatory Steps:

- Molecular Hamiltonian Formulation: Compute one- and two-electron integrals using classical electronic structure methods (Hartree-Fock). Transform the fermionic Hamiltonian to qubit representation using Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation [3].

- Ansatz Selection: Choose an appropriate parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) such as unitary coupled cluster (UCC) or hardware-efficient ansatz suitable for the target molecular system.