Quantum Resource Estimation for Molecular Simulation: A Comparative Analysis of LiH, BeH₂, and H₆ for Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of quantum computational resources required for simulating key molecular systems—Lithium Hydride (LiH), Beryllium Hydride (BeH₂), and the Hydrogen Hexamer (H₆)—with significant relevance to biomedical...

Quantum Resource Estimation for Molecular Simulation: A Comparative Analysis of LiH, BeH₂, and H₆ for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of quantum computational resources required for simulating key molecular systems—Lithium Hydride (LiH), Beryllium Hydride (BeH₂), and the Hydrogen Hexamer (H₆)—with significant relevance to biomedical research and drug development. We explore foundational quantum chemistry concepts, compare methodological approaches including Hamiltonian simulation algorithms and error correction strategies, and present optimization techniques for reducing resource overhead. Through validation and comparative analysis of quantum resource requirements—including qubit counts, gate operations, and algorithmic efficiency—we offer practical insights for researchers seeking to implement these simulations on emerging fault-tolerant quantum hardware. The findings demonstrate that optimal compilation strategies are highly dependent on molecular target and algorithmic choice, with significant implications for accelerating computational drug discovery.

Fundamental Quantum Chemistry and Biomedical Significance of LiH, BeH₂, and H₆ Molecular Systems

The field of drug discovery is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the convergence of quantum mechanics and computational science. Traditional drug discovery is a lengthy and expensive endeavor, often requiring over a decade and billions of dollars to bring a single therapeutic to market, while facing fundamental limitations in exploring the vast chemical space of potential drug compounds—estimated at 10^60 molecules [1]. Quantum computational chemistry emerges as a disruptive solution, leveraging the inherent quantum nature of molecular systems to simulate drug-target interactions with unprecedented accuracy. Unlike classical computers that approximate quantum effects, quantum computers operate using the same fundamental principles—superposition, entanglement, and interference—that govern molecular behavior at the subatomic level [2]. This intrinsic alignment positions quantum computational chemistry to tackle previously "undruggable" targets and accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic compounds, potentially revolutionizing how we address global health challenges.

Fundamental Quantum Methods in Drug Discovery

Quantum computational chemistry employs several core computational methods to model molecular systems, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and applications in drug discovery.

Density Functional Theory (DFT)

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a computational quantum mechanical method that models electronic structures by focusing on electron density Ï(r) rather than wave functions [3]. Grounded in the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, DFT determines that the electron density uniquely determines ground-state properties. The total energy in DFT is expressed as: [E[Ï]=T[Ï]+V{ext}[Ï]+V{ee}[Ï]+E{xc}[Ï]] where (E[Ï]) is the total energy functional, (T[Ï]) is the kinetic energy, (V{ext}[Ï]) is the external potential energy, (V{ee}[Ï]) is electron-electron repulsion, and (E{xc}[Ï]) is the exchange-correlation energy [3]. The Kohn-Sham equations solve this computationally: [-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\nabla^2+V{eff}(r)\phii(r)=\epsiloni\phii(r)] where (\phii(r)) are single-particle orbitals and (V{eff}(r)) is the effective potential [3]. In drug discovery, DFT calculates molecular properties, binding energies, and reaction pathways with efficiency for systems of ~100-500 atoms, though accuracy depends on exchange-correlation function approximations [3].

Hartree-Fock (HF) Method

The Hartree-Fock (HF) method is a foundational wave function-based approach that approximates the many-electron wave function as a single Slater determinant, ensuring antisymmetry per the Pauli exclusion principle [3]. The HF energy is obtained by minimizing: [E{HF}=\langle\Psi{HF}|\hat{H}|\Psi{HF}\rangle] where (E{HF}) is Hartree-Fock energy, (\Psi{HF}) is the HF wave function, and (\hat{H}) is the electronic Hamiltonian [3]. The HF equations, [\hat{f}\varphii=\epsiloni\varphii] where (\hat{f}) is the Fock operator and (\varphi_i) are molecular orbitals, are solved iteratively via the self-consistent field (SCF) method [3]. While HF provides baseline electronic structures for small molecules, it neglects electron correlation, leading to underestimated binding energies—particularly problematic for weak non-covalent interactions crucial to protein-ligand binding [3].

Hybrid Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM)

QM/MM combines quantum mechanical accuracy with molecular mechanics efficiency, enabling simulation of large biomolecular systems by applying QM to the chemically active region (e.g., enzyme active site) and MM to the surrounding environment [3]. This method is particularly valuable for studying enzyme reaction mechanisms and ligand binding in biological contexts.

Post-Hartree-Fock Methods

Post-Hartree-Fock methods systematically improve upon HF approximations by incorporating electron correlation through techniques like Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2), coupled-cluster approaches (e.g., CCSD(T)), and density matrix renormalisation group [4]. These methods provide increasing accuracy at greater computational cost, with full configuration interaction (FCI) solving the Schrödinger equation exactly but at exponential classical computational cost [4].

Table: Comparison of Fundamental Quantum Chemistry Methods

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Computational Scaling | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Primary Drug Discovery Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Wave function, single Slater determinant | O(Nâ´) with basis functions | Foundation for post-HF methods; provides molecular orbitals | Neglects electron correlation; inaccurate for dispersion forces | Baseline electronic structures; molecular geometries; dipole moments [3] |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Electron density via Kohn-Sham equations | O(N³) with basis functions | Good balance of accuracy and efficiency for many systems | Accuracy depends on exchange-correlation functional; not systematically improvable | Electronic structures; binding energies; reaction pathways; ADMET properties [3] [4] |

| QM/MM | Combines QM and MM regions | Varies with QM method and system size | Enables simulation of large biomolecular systems | Boundary region artifacts; computational expense | Enzyme reaction mechanisms; ligand binding in protein environments [3] |

| Coupled Cluster (CCSD(T)) | Wave function with cluster operators | O(Nâ·) | "Gold standard" for high accuracy | Computationally expensive; limited to small systems | High-accuracy reference calculations; small molecule properties [4] |

Quantum Computing Approaches vs. Classical Methods

Quantum computing introduces revolutionary approaches to computational chemistry, potentially overcoming fundamental limitations of classical methods for specific problem classes.

Fundamental Quantum Computing Principles

Quantum computers leverage qubits as their fundamental unit, which differ profoundly from classical bits. While classical bits represent either 0 or 1, a qubit can exist in a superposition state: [|\psi\rangle = c0|0\rangle + c1|1\rangle] where (c0) and (c1) are complex numbers with (|c0|^2 + |c1|^2 = 1) [1]. This state can be visualized as a point on the Bloch sphere, providing continuous representation beyond binary states [1]. For n qubits, the state space grows exponentially: [|\Psi\rangle = \sum{z1,\ldots,zn=0,1} c{z1\ldots zn}|z1\ldots zn\rangle] requiring an exponential number of classical amplitudes to specify [1]. Quantum algorithms exploit superposition, entanglement, and interference to solve problems intractable for classical computers, with particular relevance to molecular simulation.

Key Quantum Algorithms for Chemistry

Several quantum algorithms show promise for computational chemistry applications:

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE): A hybrid quantum-classical algorithm that uses a parameterized quantum circuit to prepare trial wavefunctions and classical optimization to find molecular ground states [5] [6].

Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE): Provides more accurate energy calculations than VQE but requires greater circuit depth and coherence times [4] [6].

Quantum Imaginary Time Evolution (QITE): Simulates imaginary time evolution to find ground states, an alternative to VQE [6].

Current Capabilities and Limitations

While quantum computing holds tremendous promise, current hardware faces significant limitations. Error rates, qubit counts, and coherence times remain constraints, though 2025 has witnessed dramatic progress with error rates reaching record lows of 0.000015% per operation and improved error correction techniques [5]. Research suggests that while classical methods will likely dominate large molecule calculations for the foreseeable future, quantum computers may achieve advantages for highly accurate simulations of smaller molecules (tens to hundreds of atoms) within the next decade [6]. Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) and CCSD(T) methods may be surpassed by quantum algorithms as early as the 2030s [6].

Table: Quantum vs. Classical Computing for Molecular Simulation

| Aspect | Classical Computing | Quantum Computing | Current Status and Projections |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Representation | Discrete bits (0 or 1) | Qubits with superposition and entanglement | Quantum hardware demonstrating basic principles with rapid progress [1] [2] |

| Molecular Representation | Approximations of quantum states | Native representation of quantum states | Quantum systems can inherently represent molecular quantum states [1] |

| Scaling with System Size | Exponential for exact methods | Polynomial for certain problems | Classical methods hit exponential walls for exact simulation [4] |

| Hardware Progress | Mature with incremental gains | Rapid advancement with 100+ qubit systems | 2025 breakthroughs in error correction and qubit counts [5] [7] |

| Error Handling | Deterministic results | Susceptible to decoherence and noise | Error correction milestones achieved in 2025 [5] [7] |

| Projected Advantage Timeline | Currently dominant | Niche advantages possible by 2030; broader impact post-2035 | Economic advantage expected mid-2030s [6] |

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Quantum-Enhanced KRAS Drug Discovery Protocol

A groundbreaking 2025 study from St. Jude and the University of Toronto demonstrated the first experimental validation of quantum computing in drug discovery for the challenging KRAS cancer target [2]. The protocol employed a hybrid quantum-classical approach:

Classical Data Preparation: Researchers input a database of molecules experimentally confirmed to bind KRAS alongside over 100,000 theoretical KRAS binders from ultra-large virtual screening [2].

Classical Model Training: A classical machine learning model was trained on the KRAS binding data, generating initial candidate molecules [2].

Quantum Enhancement: Results were fed into a filter/reward function evaluating molecule quality, then trained a quantum machine-learning model combined with the classical model to improve generated molecule quality [2].

Hybrid Optimization: The system cycled between training classical and quantum models to optimize them in concert [2].

Experimental Validation: The optimized models generated novel ligands predicted to bind KRAS, with two molecules showing real-world potential upon experimental validation [2].

This protocol successfully identified ligands for one of the most important cancer drug targets, demonstrating quantum computing's potential to enhance drug discovery for previously "undruggable" targets [2].

Quantum Resource Estimation for Cytochrome P450

A 2025 study by Goings et al. investigated quantum resource requirements for simulating cytochrome P450 enzymes, crucial in drug metabolism [4]. The protocol:

Active Space Selection: Identified the set of orbitals (active space) needed to describe the physics of iron-containing systems, which challenge standard computational chemistry [4].

Classical Resource Estimation: Used classical algorithms to estimate active space sizes needed for chemical insights and corresponding classical computational resources [4].

Quantum Resource Estimation: Compared classical requirements with quantum resource estimates for quantum phase estimation algorithm [4].

Crossover Identification: Demonstrated a crossover at approximately 50 orbitals where quantum computing may become more advantageous, correctly capturing key physics of a ~40-atom heme-binding site [4].

This study provides a framework for identifying where quantum approaches may surpass classical methods for pharmaceutically relevant systems.

Quantum-Enhanced KRAS Drug Discovery Workflow: This diagram illustrates the hybrid quantum-classical protocol used to identify KRAS inhibitors, demonstrating the iterative integration of quantum and classical computational methods [2].

Quantum Resource Comparison for Specific Molecular Systems

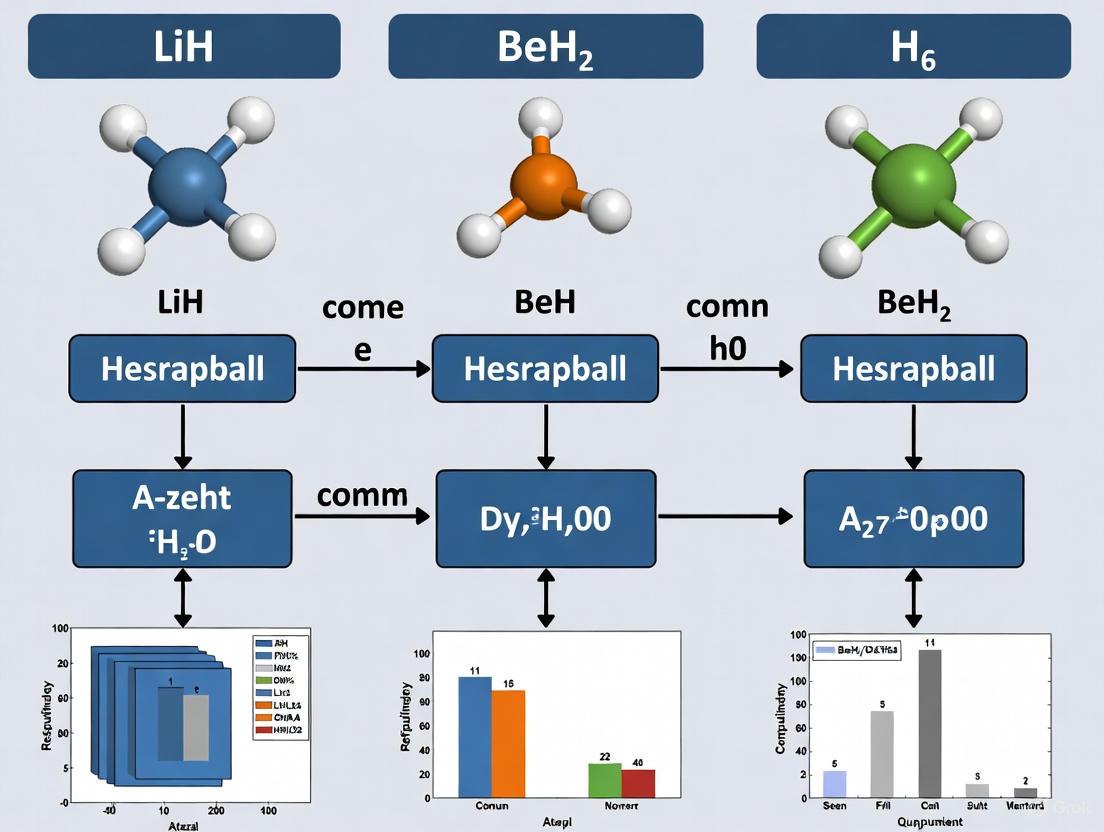

Application to LiH, BeH₂, and H₆ Molecules

While the search results don't provide explicit resource comparisons for LiH, BeH₂, and H₆ molecules specifically, they do offer frameworks for understanding how such comparisons are structured. The fundamental challenge lies in the exponential scaling of exact classical methods with system size, which quantum algorithms aim to address [4].

Resource estimates typically consider:

- Qubit requirements: Number of logical qubits needed to represent the molecular system

- Circuit depth: Number of quantum operations required

- Coherence time: How long quantum states must be maintained

- Error correction overhead: Additional resources needed for fault-tolerant computation

A 2025 research compared resource costs for Hamiltonian simulation using different surface code compilation approaches, finding that optimal schemes depend on whether simulation uses quantum signal processing or Trotter-Suzuki algorithms, with Trotterization benefiting by orders of magnitude from direct Clifford+T compilation for certain applications [8].

Hardware Platform Comparisons

Different quantum hardware platforms offer distinct advantages for chemical simulations:

- Superconducting circuits (e.g., IBM, Google): Feature fast gates and mature control electronics but limited connectivity [1].

- Trapped ions (e.g., Quantinuum, IonQ): Offer long coherence times and all-to-all connectivity within a trap but slower gate speeds [1].

- Neutral atoms (e.g., Atom Computing): Allow flexible geometries and large arrays but face atom loss challenges [1].

Table: Quantum Hardware Platforms for Chemical Simulations

| Platform | Key Advantages | Key Challenges | Relevance to Chemical Simulations | Representative Systems (2025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superconducting Circuits | Fast gates; mature control electronics | Limited connectivity; frequency crowding | Well-suited for hybrid algorithms like VQE due to rapid cycle times [1] | IBM Heron (133 qubits); Google Willow (105 qubits) [5] [7] |

| Trapped Ions | Long coherence times; all-to-all connectivity | Slower gate speeds; modular scaling required | High precision attractive for accurate small molecule simulations [1] | Quantinuum Helios (36 qubits); IonQ (36 qubits) [5] [7] |

| Neutral Atoms | Flexible geometries; large arrays | Atom loss; laser noise | Tunability offers opportunities for mapping molecular structures [1] | Atom Computing (100+ qubits) [5] |

Successful implementation of quantum computational chemistry requires both computational tools and theoretical frameworks.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function/Purpose | Examples/Providers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Programming Frameworks | Software | Develop and simulate quantum algorithms | Qiskit (IBM); CUDA-Q (Nvidia); Cirq (Google) [5] [7] |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Software | Perform classical quantum chemistry calculations | Gaussian; Q-Chem; Psi4 [3] |

| Quantum Processing Units (QPUs) | Hardware | Execute quantum algorithms | IBM Heron; Quantinuum Helios; Google Willow [5] [7] |

| Quantum Cloud Services | Platform | Remote access to quantum hardware | IBM Quantum Platform; Amazon Braket; Microsoft Azure Quantum [5] |

| Molecular Visualization | Software | Visualize molecular structures and interactions | PyMOL; ChimeraX; VMD |

| Active Space Selection Tools | Methodology | Identify crucial orbitals for quantum simulation | DMRG; CASSCF [4] |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Methodology | Reduce impact of noise on quantum results | Zero-Noise Extrapolation; Readout Mitigation [1] |

| Hybrid HPC-QPU Architectures | Infrastructure | Integrate quantum and classical computing | Fugaku Supercomputer + IBM Heron [7] |

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The field of quantum computational chemistry is rapidly evolving, with several key trends and research opportunities emerging:

Hardware and Algorithm Co-Design

The future of quantum computational chemistry lies in co-design approaches where hardware and software are developed collaboratively with specific applications in mind [5]. This approach integrates end-user needs early in the design process, yielding optimized quantum systems that extract maximum utility from current hardware limitations. Research initiatives by companies like QuEra focus on developing error-corrected algorithms that align hardware capabilities with application requirements [5].

Expanding Application Domains

While current applications focus on molecular simulation and drug discovery, future research may expand to:

- Covalent inhibitor design: Using "quantum fingerprints" to understand warhead reactivity and environmental effects [4].

- Drug metabolism prediction: Particularly for complex metalloenzymes like cytochrome P450 [4].

- Protein dynamics: Simulating conformational changes and allosteric mechanisms [3].

Timeline for Practical Quantum Advantage

Research suggests a nuanced timeline for quantum advantage in computational chemistry:

- 2025-2030: Niche advantages for specific problems with high accuracy requirements for smaller molecules (tens of atoms) [6].

- 2030-2035: Potential disruption of FCI and CCSD(T) methods, with economic advantage emerging [6].

- Post-2035: Broader application to larger systems, potentially modeling systems containing up to 10^5 atoms by 2040s [6].

However, this timeline depends on continued algorithmic improvements and hardware developments, with some researchers cautioning that classical methods will likely outperform quantum algorithms for at least the next two decades in many computational chemistry applications [6].

Projected Timeline for Quantum Advantage: This visualization shows the anticipated progression of quantum computational chemistry capabilities, from current hybrid approaches to potential broad advantage in coming decades [6].

Electronic Structure Properties of LiH, BeH₂, and H₆ Molecules

The accurate simulation of molecular electronic structure is a cornerstone of modern chemical and drug development research. For emerging technologies like quantum computing, this challenge represents a promising application area. The variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithm for finding molecular ground-state energies on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) computers. A critical factor influencing the success of these simulations is the choice of the ansatz—a parameterized quantum circuit that prepares trial wavefunctions. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance of three leading adaptive VQE protocols—fermionic-ADAPT-VQE, qubit-ADAPT-VQE, and qubit-excitation-based adaptive (QEB-ADAPT)-VQE—in determining the electronic properties of the small molecules LiH, BeH₂, and H₆. The comparative analysis focuses on key quantum resource metrics, including convergence speed and quantum circuit efficiency, providing researchers with critical data for selecting appropriate computational protocols for their investigations [9].

Theoretical Background and Methodologies

The Electronic Structure Problem

The electronic structure problem involves finding the ground-state electron wavefunction and its corresponding energy for a molecule. Under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, the electronic Hamiltonian of a molecule can be expressed in its second-quantized form as [9]: $$H=\sum{i,k}^{N{\text{MO}}} h{i,k} a{i}^{\dagger} a{k} + \sum{i,j,k,l}^{N{\text{MO}}} h{i,j,k,l} a{i}^{\dagger} a{j}^{\dagger} a{k} a{l}$$ Here, (N{\text{MO}}) is the number of molecular spin orbitals, (a{i}^{\dagger}) and (a{i}) are fermionic creation and annihilation operators, and (h{i,k}) and (h_{i,j,k,l}) are one- and two-electron integrals. This Hamiltonian is then mapped to quantum gate operators using encoding methods such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev to become executable on a quantum processor [9].

Adaptive VQE Protocols

The standard VQE is a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm that estimates the lowest eigenvalue of a Hamiltonian by minimizing the energy expectation value (E(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \langle \psi(\boldsymbol{\theta}) | H | \psi(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \rangle) with respect to a parameterized state (|\psi(\boldsymbol{\theta})\rangle = U(\boldsymbol{\theta}) |\psi_{0}\rangle), where (U(\boldsymbol{\theta})) is the ansatz [9]. Adaptive VQE protocols build a problem-tailored ansatz iteratively, which offers advantages in circuit depth and parameter efficiency compared to fixed, pre-defined ansätze like UCCSD (Unitary Coupled-Cluster Singles and Doubles) [9].

- Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE: This protocol constructs its ansatz from a pool of operators based on fermionic excitation evolutions. These operators are physically motivated and respect the fermionic symmetries of electronic wavefunctions [9].

- Qubit-ADAPT-VQE: This protocol uses a pool of more rudimentary, yet highly flexible, Pauli string exponentials. This leads to shallower quantum circuits but often requires more iterations and parameters to achieve a given accuracy [9].

- QEB-ADAPT-VQE: The QEB-ADAPT-VQE protocol utilizes qubit excitation evolutions as its ansatz elements. These operators satisfy qubit commutation relations rather than fermionic ones. They represent a middle ground, offering the hardware efficiency of Pauli strings while retaining a higher-level structure that accelerates convergence, outperforming Qubit-ADAPT-VQE in both circuit efficiency and convergence speed [9].

The following workflow illustrates the iterative process shared by these adaptive VQE protocols.

Performance Comparison of Adaptive VQE Protocols

This section provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of the three adaptive VQE protocols, highlighting their performance in simulating the LiH, BeH₂, and H₆ molecules.

Quantum Resource Metrics

The performance of adaptive VQE protocols is evaluated based on several key metrics that directly impact their feasibility on near-term quantum hardware [9]:

- Circuit Efficiency: The overall depth and gate count of the final quantum circuit. Shallower circuits are less susceptible to noise on NISQ devices.

- Convergence Speed: The number of iterations required for the energy estimate to reach chemical accuracy (typically 10â»Â³ Hartree). Fewer iterations reduce the number of quantum measurements and classical optimization cycles.

- Parameter Count: The number of variational parameters in the ansatz. A lower count can simplify the classical optimization problem.

Comparative Performance Data

The table below summarizes the comparative performance of the three protocols across the molecules of interest, as demonstrated through classical numerical simulations [9].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Adaptive VQE Protocols for LiH, BeH₂, and H₆

| Molecule | Protocol | Final CNOT Gate Count | Number of Iterations to Convergence | Number of Variational Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH | Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE | Higher than QEB-ADAPT | Moderate | Several times fewer than UCCSD [9] |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE | Lower than Fermionic-ADAPT [9] | Higher than QEB-ADAPT [9] | Higher than QEB-ADAPT [9] | |

| QEB-ADAPT-VQE | Lowest | Lowest [9] | Moderate | |

| BeHâ‚‚ | Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE | Higher than QEB-ADAPT | Moderate | Several times fewer than UCCSD [9] |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE | Lower than Fermionic-ADAPT [9] | Higher than QEB-ADAPT [9] | Higher than QEB-ADAPT [9] | |

| QEB-ADAPT-VQE | Lowest | Lowest [9] | Moderate | |

| H₆ | Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE | Higher than QEB-ADAPT | Moderate | Several times fewer than UCCSD [9] |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE | Lower than Fermionic-ADAPT [9] | Higher than QEB-ADAPT [9] | Higher than QEB-ADAPT [9] | |

| QEB-ADAPT-VQE | Lowest | Lowest [9] | Moderate |

Convergence Behavior Analysis

The convergence profiles of the different protocols reveal distinct characteristics. The QEB-ADAPT-VQE protocol demonstrates a steeper initial energy descent compared to the other two methods, reaching chemical accuracy in fewer iterations for molecules like LiH, BeH₂, and H₆ [9]. This indicates a more efficient ansatz construction process. While the Qubit-ADAPT-VQE can achieve low final circuit depths, it typically requires more iterations and variational parameters to converge than QEB-ADAPT-VQE [9]. The Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE, while physically intuitive, produces deeper circuits than its qubit-based adaptive counterparts [9]. The following diagram visualizes the typical convergence hierarchy of these protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Computational Components

This section details the essential "research reagents"—the core computational components and methods required to implement the VQE protocols discussed in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Computational Components for Molecular VQE Simulations

| Component | Function & Description | Relevance to Protocol Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Qubit Excitation Evolution | Unitary evolution of qubit excitation operators; satisfies qubit commutation relations. Requires asymptotically fewer gates than fermionic excitations [9]. | Core ansatz element of QEB-ADAPT-VQE; provides a balance of physical intuition and hardware efficiency [9]. |

| Fermionic Excitation Evolution | Unitary evolution of fermionic excitation operators; respects the physical symmetries of electronic wavefunctions [9]. | Core ansatz element of Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE and UCCSD. More physically intuitive but leads to deeper circuits [9]. |

| Pauli String Exponential | Evolution of a string of Pauli matrices (X, Y, Z); a fundamental and hardware-native quantum gate operation. | Core ansatz element of Qubit-ADAPT-VQE. Offers circuit efficiency but may lack structured efficiency, requiring more parameters [9]. |

| Jordan-Wigner Encoding | A method for mapping fermionic operators to quantum gate operators by preserving anticommutation relations via qubit entanglement [9]. | A common encoding method used across all protocols. Allows the electronic Hamiltonian to be represented on a quantum processor [9]. |

| Classical Optimizer | An algorithm (e.g., gradient descent) that adjusts the variational parameters θ to minimize the energy expectation value. | Crucial for all VQE protocols. Performance can be affected by the number of parameters and the complexity of the energy landscape introduced by the ansatz. |

| Operator Pool | A predefined set of operators from which the adaptive algorithm selects to grow the ansatz [9]. | The composition of the pool (fermionic, qubit, etc.) defines the protocol and directly impacts convergence and circuit efficiency [9]. |

| [1,1-Biphenyl]-3,3-diol,6,6-dimethyl- | [1,1-Biphenyl]-3,3-diol,6,6-dimethyl-, CAS:116668-39-4, MF:C14H16O2, MW:216.28 | Chemical Reagent |

| triptocallic acid A | triptocallic acid A, CAS:190906-61-7, MF:C30H48O4, MW:472.71 | Chemical Reagent |

The choice of an adaptive VQE protocol directly influences the quantum resource requirements for simulating molecular electronic structures. Based on the comparative data for LiH, BeH₂, and H₆ molecules:

- The QEB-ADAPT-VQE protocol emerges as the most balanced performer, achieving the highest circuit efficiency and fastest convergence, making it a superior candidate for simulations on resource-constrained NISQ hardware [9].

- The Qubit-ADAPT-VQE protocol, while generating shallow circuits, does so at the cost of requiring more iterations and variational parameters [9].

- The Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE protocol offers strong physical intuition and respect for molecular symmetries but results in deeper quantum circuits than its qubit-based adaptive counterparts [9].

For researchers and scientists embarking on quantum computational chemistry projects, this guide recommends the QEB-ADAPT-VQE protocol for applications where minimizing circuit depth and accelerating convergence are the primary objectives. This analysis provides a foundational resource for making informed decisions in the selection and implementation of quantum algorithms for electronic structure research.

Biomedical Relevance and Potential Applications in Pharmaceutical Development

The simulation of molecular systems is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to predict the behavior and interactions of potential therapeutic compounds. For the pharmaceutical industry, the accurate calculation of a molecule's ground-state energy is particularly critical, as it dictates molecular structure, stability, and interaction with biological targets [10]. Classical computing methods often rely on approximations that can compromise accuracy, especially for complex or strongly correlated molecular systems, which are common in drug development pipelines [11] [12].

Quantum computing represents a paradigm shift, offering a path to perform these simulations based on first-principles quantum mechanics. This article provides a comparative analysis of leading variational quantum algorithms—the Hardware-efficient Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), the Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCCSD) ansatz, and the adaptive derivative-assembled pseudo-Trotter VQE (ADAPT-VQE)—for the simulation of small molecules (LiH, BeH2, H6) with direct relevance to biomedical research. We present quantitative performance data, detailed experimental protocols, and essential resource information to guide researchers in selecting appropriate quantum resources for pharmaceutical development.

Comparative Performance of Quantum Algorithms

The pursuit of chemical accuracy with minimal quantum resources is a primary focus for near-term quantum applications in drug discovery. The following table summarizes the performance of different variational quantum eigensolvers for the exact simulation of the test molecules, highlighting key metrics for resource planning.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Quantum Algorithms for Molecular Simulation

| Molecule | Algorithm | Number of Operators/Parameters | Circuit Depth | Achievable Accuracy (vs. FCI) | Key Performance Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH | UCCSD [11] | Fixed ansatz (Pre-selected) | High | Approximate | Standard method; performance is system-dependent and can be inefficient. |

| ADAPT-VQE [11] | Grows systematically (Minimal) | Shallow | Arbitrarily Accurate | Outperforms UCCSD in both circuit depth and chemical accuracy. | |

| BeHâ‚‚ | Hardware-efficient VQE [10] | Not Specified | Shallow (d=1 demonstrated) | Accurate for small models | Designed for minimal gate count on specific hardware; less general than chemistry-inspired ansatzes. |

| UCCSD [11] | Fixed ansatz (Pre-selected) | High | Approximate | Struggles with strongly correlated systems; requires higher-rank excitations for accuracy. | |

| ADAPT-VQE [11] | Grows systematically (Minimal) | Shallow | Arbitrarily Accurate | Generates a compact, quasi-optimal ansatz determined by the molecule itself. | |

| H₆ | UCCSD [11] | Fixed ansatz (Pre-selected) | High | Approximate | Can be prohibitively expensive for both classical subroutines and NISQ devices. |

| ADAPT-VQE [11] | Grows systematically (Minimal) | Shallow | Arbitrarily Accurate | Performs much better than UCCSD for prototypical strongly correlated molecules. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) Workflow

The VQE algorithm is a hybrid quantum-classical approach that leverages both quantum and classical processors to find the ground-state energy of a molecular Hamiltonian [11] [10]. The core workflow is as follows:

- Hamiltonian Formulation: The molecular electronic structure problem is encoded into a qubit Hamiltonian, (\hat{H} = \sumi gi \hat{o}i), where (gi) are coefficients and (\hat{o}_i) are Pauli operators [11] [10]. This involves mapping fermionic creation and annihilation operators to qubit operations via transformations such as the Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev encoding.

- Ansatz Preparation: A parameterized quantum circuit (the "ansatz") (U(\vec{\theta})) is chosen to prepare a trial wavefunction (|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle) from an initial reference state, often the Hartree-Fock state (| \psi^{HF} \rangle) [11] [10].

- Quantum Measurement: The quantum processor prepares the trial state and measures the expectation values of the individual Hamiltonian terms, (\langle \psi(\vec{\theta}) | \hat{o}_i | \psi(\vec{\theta}) \rangle). Because the terms generally do not commute, the state preparation and measurement must be repeated many times to gather sufficient statistics [11].

- Classical Optimization: The measured expectation values are summed on a classical computer to compute the total energy (E(\vec{\theta}) = \sumi gi \langle \hat{o}_i \rangle). A classical optimization algorithm is then used to adjust the parameters (\vec{\theta}) to minimize (E(\vec{\theta})) [11] [10]. Steps 3 and 4 are repeated iteratively until the energy converges to a minimum.

The following diagram illustrates this iterative workflow.

The ADAPT-VQE Algorithm Protocol

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm enhances the standard VQE by building a system-specific ansatz, avoiding the limitations of a pre-selected form like UCCSD [11]. Its protocol is:

- Initialization: Begin with a simple reference state, such as the Hartree-Fock Slater determinant (|\psi_0\rangle = | \psi^{HF} \rangle).

- Operator Pool Definition: Define a pool of elementary fermionic excitation operators, typically consisting of anti-Hermitian operators (\hat{\tau}i^a = \hat{t}i^a - \hat{t}a^i) (for singles) and (\hat{\tau}{ij}^{ab} = \hat{t}{ij}^{ab} - \hat{t}{ab}^{ij}) (for doubles), where (\hat{t}) are standard cluster excitation operators [11].

- Greedy Ansatz Construction: At each step

N: a. Gradient Evaluation: For every operator (An) in the pool, compute the energy gradient (or a proxy like the absolute value of the gradient) with respect to that operator, (|\partial E / \partial An|), using the current state (|\psi{N-1}\rangle). b. Operator Selection: Identify the operator (A{max}) with the largest gradient. c. Ansatz Growth: Append the selected operator to the ansatz: (|\psiN\rangle = e^{\theta{N} A{max}} |\psi{N-1}\rangle). The parameter (\theta_{N}) is initialized to zero. - VQE Optimization: Run a standard VQE optimization to minimize the energy with respect to all parameters (\vec{\theta} = (\theta1, \theta2, ..., \theta_N)) in the current ansatz.

- Convergence Check: Steps 3 and 4 are repeated until the energy converges to a pre-defined accuracy (e.g., chemical accuracy) or the energy gradient falls below a set threshold. This process systematically grows an ansatz with a minimal number of operators [11].

The logical flow of the ADAPT-VQE algorithm is shown below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of quantum simulations for pharmaceutical development requires a suite of computational "reagents." The following table details essential components and their functions in a typical quantum computational chemistry workflow.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Quantum Simulation in Drug Discovery

| Tool Category | Specific Example / Method | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Ansatz Formulation | Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCCSD) [11] | A pre-defined, chemistry-inspired ansatz generating trial states via exponential of fermionic excitation operators. Serves as a standard benchmark. |

| ADAPT-VQE Ansatz [11] | A system-specific, dynamically constructed ansatz grown by iteratively adding the most energetically relevant operators from a pool. | |

| Hardware-efficient Ansatz [10] | An ansatz designed with minimal gate depth using native quantum processor gates, sacrificing chemical intuition for hardware feasibility. | |

| Measurement & Analysis | Hamiltonian Term Measurement [11] | The process of repeatedly preparing a quantum state and measuring the expectation values of the non-commuting Pauli terms that make up the molecular Hamiltonian. |

| Classical Co-Processing | Classical Optimizer (e.g., COBYLA) [11] [10] | A classical numerical algorithm that adjusts the quantum circuit parameters to minimize the computed energy expectation value. |

| Software & Libraries | Quantum Chemistry Packages (e.g., OpenFermion) | Classical software tools used for the initial computation of molecular integrals, generation of the fermionic Hamiltonian, and its mapping to a qubit Hamiltonian. |

| Termitomycamide B | Termitomycamide B|For Research Use Only | Termitomycamide B is a natural product for antimicrobial and anticancer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human, veterinary, or household use. |

| alpha-Isowighteone | alpha-Isowighteone, MF:C20H18O5, MW:338.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Key Quantum Chemical Challenges in Molecular Energy Calculation

Calculating molecular energies with high accuracy remains one of the most promising yet challenging applications for quantum computing in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era. The fundamental challenge centers on developing algorithms that can provide accurate solutions while operating within severe quantum hardware constraints, including limited qubit coherence times, gate fidelity, and circuit depth capabilities. Adaptive variational quantum algorithms have emerged as frontrunners in addressing this challenge by dynamically constructing efficient quantum circuits tailored to specific molecular systems. This comparison guide examines the performance of leading adaptive and static variational algorithms applied to key testbed molecules—LiH, BeH₂, and H₆—providing researchers with critical insights into quantum resource requirements and optimization strategies essential for advancing quantum chemistry simulations.

Table: Key Molecular Systems for Quantum Resource Comparison

| Molecule | Qubit Requirements | Significance in Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| LiH | 12 qubits | Medium-sized system for testing algorithmic efficiency |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 12 qubits | Linear chain structure for evaluating geometric handling |

| H₆ | 14 qubits | Larger multi-center system for scalability assessment |

Algorithm Comparison: ADAPT-VQE and Its Evolution

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a significant advancement over static ansätze approaches by iteratively constructing circuit components based on energy gradient information. Unlike fixed-ansatz methods like Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD), which may include unnecessary operations, ADAPT-VQE builds circuits operator by operator, typically resulting in more compact and targeted structures. Recent innovations have substantially improved ADAPT-VQE's performance through two primary mechanisms: the introduction of Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pools and implementation of amplitude reordering strategies.

The CEO pool approach fundamentally reorganizes how operators are selected and combined, creating more efficient representations of electron interactions within quantum circuits. When combined with improved subroutines, this method demonstrates dramatic quantum resource reductions compared to early ADAPT-VQE implementations [13]. Simultaneously, amplitude reordering accelerates the adaptive process by adding operators in "batched" fashion while maintaining quasi-optimal ordering, significantly reducing the number of iterative steps required for convergence [14]. These developments represent complementary paths toward the same goal: making molecular energy calculations more feasible on current quantum hardware.

Performance Metrics and Quantitative Comparison

Quantum algorithm performance for molecular energy calculations is evaluated through multiple resource metrics, each with direct implications for experimental feasibility. The tables below synthesize quantitative data from recent studies comparing state-of-the-art adaptive approaches against traditional methods.

Table: Quantum Resource Reduction Comparison for 12-14 Qubit Systems [13]

| Algorithm | CNOT Count Reduction | CNOT Depth Reduction | Measurement Cost Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE | Up to 88% | Up to 96% | Up to 99.6% |

| Representative Molecules | LiH, BeH₂ (12 qubits) | H₆ (14 qubits) | All Tested Systems |

Table: Computational Acceleration Through Amplitude Reordering [14]

| Algorithm Variant | Speedup Factor | Iteration Reduction | Accuracy Maintenance |

|---|---|---|---|

| AR-ADAPT-VQE | >10x | Significant | No obvious loss |

| AR-AES-VQE | >10x | Significant | Maintained or improved |

| Test Systems | LiH, BeH₂, H₆ | All dissociation curves | Compared to original |

The data reveals that CEO-ADAPT-VQE not only outperforms the widely used UCCSD ansatz in all relevant metrics but also offers a five-order-of-magnitude decrease in measurement costs compared to other static ansätze with competitive CNOT counts [13]. Meanwhile, amplitude reordering strategies achieve acceleration by significantly reducing the number of iterations required for convergence while maintaining, and sometimes even improving, computational accuracy [14].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CEO-ADAPT-VQE Implementation

The experimental protocol for assessing CEO-ADAPT-VQE begins with molecular system preparation, where the electronic structure of target molecules (LiH, BeH₂, H₆) is encoded into qubit representations using standard transformation techniques such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformations. The core innovation lies in the operator pool construction, where traditional unitary coupled cluster operators are replaced with coupled exchange operators designed to capture the most significant electron correlations more efficiently [13].

The algorithm proceeds iteratively through the following steps: (1) Gradient calculation for all operators in the CEO pool; (2) Selection of the operator with the largest gradient magnitude; (3) Circuit appending and recompilation; (4) Parameter optimization using classical methods; (5) Convergence checking against a predefined threshold. Throughout this process, improved subroutines for measurement and circuit compilation are employed to minimize quantum resource requirements. Performance is quantified by tracking CNOT gate counts, circuit depth, and total measurements required to achieve chemical accuracy across varying bond lengths in dissociation curve calculations [13].

Amplitude Reordering ADAPT-VQE Protocol

The amplitude reordering approach modifies the standard ADAPT-VQE protocol by introducing a batching mechanism for operator selection. Rather than adding a single operator per iteration, the algorithm: (1) Calculates gradients for all operators in the pool; (2) Sorts operators by gradient magnitude; (3) Selects a batch of operators with the largest gradients; (4) Adds the entire batch to the circuit before reoptimization [14].

This batched approach significantly reduces the number of optimization cycles required while maintaining circuit efficiency. The experimental validation involves comparing dissociation curves generated by standard ADAPT-VQE and AR-ADAPT-VQE for LiH, linear BeH₂, and linear H₆ molecules, with specific attention to the number of iterations required to reach convergence and the final accuracy achieved across the potential energy surface [14].

Diagram Title: Adaptive VQE Algorithm Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for Molecular Energy Calculations on Quantum Hardware

| Research Reagent | Function & Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CEO Operator Pool | Provides more efficient representation of electron correlations compared to traditional UCCSD operators | Reduces CNOT counts and circuit depth by up to 88% and 96% respectively [13] |

| Amplitude Reordering Module | Accelerates convergence by batching operator selection based on gradient magnitudes | Reduces iteration count with >10x speedup while maintaining accuracy [14] |

| Gradient Measurement Protocol | Determines which operators to add to the circuit in adaptive approaches | Most computationally expensive step in standard ADAPT-VQE; optimized in new approaches |

| Circuit Compilation Tools | Translates chemical operators into executable quantum gate sequences | Critical for minimizing CNOT counts and overall circuit depth through efficient decompositions |

| Classical Optimizer | Adjusts circuit parameters to minimize energy measurement | Works in hybrid quantum-classical loop; choice affects convergence efficiency |

| Taiwanhomoflavone B | Taiwanhomoflavone B, CAS:509077-91-2, MF:C32H24O10, MW:568.534 | Chemical Reagent |

| Erythorbic Acid | Erythorbic Acid (CAS 89-65-6) - For Research Use Only | Erythorbic Acid is a stereoisomer of ascorbic acid used as an antioxidant in food science research. This product is for laboratory research use only. |

The systematic comparison of quantum algorithms for molecular energy calculations reveals substantial progress in reducing quantum resource requirements while maintaining accuracy. The combined advances of CEO pools and amplitude reordering strategies address complementary challenges—circuit efficiency and convergence speed—that have previously hindered practical implementation of adaptive VQE approaches. For researchers investigating molecular systems like LiH, BeH₂, and H₆, these developments enable more extensive explorations of potential energy surfaces and reaction pathways on currently available quantum hardware.

Looking forward, the integration of these resource-reduction strategies with error mitigation techniques and hardware-specific optimizations represents the next frontier for quantum computational chemistry. As quantum processors continue to evolve, the algorithmic advances documented in this guide provide a foundation for simulating increasingly complex molecular systems, potentially accelerating discoveries in drug development and materials science where accurate energy calculations remain computationally prohibitive for classical approaches.

Introduction This guide compares the quantum computational resources required for simulating the electronic structure of LiH, BeH₂, and H₆ molecules. The analysis focuses on two critical metrics: the number of qubits and the number of Hamiltonian terms under different fermion-to-qubit mapping techniques, providing a direct performance comparison for quantum chemistry simulations.

Experimental Protocols

Molecular Geometry Optimization:

- Method: Geometry optimization is performed using classical electronic structure methods (e.g., Density Functional Theory or Hartree-Fock) with a standard basis set (e.g., STO-3G) to determine the equilibrium bond lengths and angles for each molecule (LiH, BeH₂, H₆).

- Software: Common computational chemistry packages like PySCF or Gaussian are employed.

Electronic Integral Calculation:

- Method: Using the optimized geometry, one- and two-electron integrals are computed in the chosen atomic orbital basis set. These integrals define the second-quantized molecular Hamiltonian.

- Output: The Hamiltonian is expressed in its fermionic form:

H = Σ h_{ij} a_i†a_j + Σ h_{ijkl} a_i†a_j†a_k a_l.

Qubit Hamiltonian Generation:

- Method: The fermionic Hamiltonian is transformed into a qubit Hamiltonian via different mapping techniques.

- Jordan-Wigner (JW): Maps fermionic operators to Pauli strings with a linear overhead, using a chain of Z gates to enforce antisymmetry.

- Bravyi-Kitaev (BK): Uses a more efficient, logarithmically-scaling transformation of the fermionic occupation number space to qubit space.

- Parity Mapping: Represents qubits in the parity basis, where the state of a qubit encodes the parity of occupation numbers up to that orbital.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Qubit Requirements and Hamiltonian Complexity for Minimal Basis (STO-3G)

| Molecule | Spin Orbitals | Qubits (JW) | Qubits (BK) | Qubits (Parity) | Hamiltonian Terms (JW) | Hamiltonian Terms (BK) | Hamiltonian Terms (Parity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 630 | 452 | 518 |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 1,260 | 855 | 1,012 |

| H₆ | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 758 | 521 | 612 |

Mandatory Visualization

Title: Fermion-to-Qubit Hamiltonian Mapping Workflow

Title: Qubit Count Comparison Across Molecules and Mappings

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Item | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|

| PySCF | An open-source quantum chemistry software package used for molecular geometry optimization and electronic integral calculation. |

| OpenFermion | A library for compiling and analyzing quantum algorithms to simulate fermionic systems, used for fermion-to-qubit mapping. |

| Qiskit Nature | A quantum software stack module (from IBM) specifically designed for quantum chemistry simulations, including Hamiltonian generation. |

| Jordan-Wigner Mapping | A standard fermion-to-qubit transformation method. Simple to implement but can lead to Hamiltonian representations with many terms. |

| Bravyi-Kitaev Mapping | A more advanced fermion-to-qubit transformation that often yields Hamiltonians with fewer terms than Jordan-Wigner, improving simulation efficiency. |

Quantum Algorithm Implementation and Error Correction Strategies for Molecular Simulation

Quantum Hamiltonian simulation, the task of determining the energy and properties of a quantum system, is a cornerstone problem with profound implications for chemistry and materials science. For researchers investigating molecules such as LiH, BeH₂, and H₆, selecting the appropriate quantum algorithm is a critical decision that balances computational resources against desired accuracy. Two primary algorithms have emerged: the Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) algorithm, which is both exact and resource-intensive, and the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), a hybrid quantum-classical approach designed for near-term devices.

This guide provides an objective comparison of these algorithms, detailing their theoretical foundations, practical resource requirements, and suitability for different stages of research. The analysis is framed within a broader thesis on quantum resource comparison, supplying the experimental protocols and data necessary for informed algorithmic selection in scientific and pharmaceutical development.

Theoretical Foundations and Algorithmic Mechanisms

Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE)

Quantum Phase Estimation is a deterministic, fault-tolerant algorithm designed for large-scale, error-corrected quantum computers. Its primary objective is to resolve the energy eigenvalues of a Hamiltonian directly. QPE functions by leveraging the quantum Fourier transform to read out the phase imparted by a time-evolution operator, ( e^{-iHt} ), applied to an initial state. This process projects the system into an eigenstate of H and measures its corresponding energy eigenvalue with high precision. The algorithm's precision is inherently linked to the number of qubits in the "energy register"; more qubits enable a more precise estimation of the energy value.

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE)

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver is a hybrid, heuristic algorithm often cited as promising for the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era [15]. It operates on a fundamentally different principle than QPE. VQE uses a parameterized quantum circuit (an "ansatz") to prepare a trial wavefunction, ( |\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle ). The heart of the algorithm is the evaluation of the expectation value of the Hamiltonian, ( \langle H \rangle = \frac{\langle \psi(\vec{\theta}) | H| \psi(\vec{\theta}) \rangle }{\langle \psi(\vec{\theta})|\psi(\vec{\theta}) \rangle } ), which is performed on the quantum computer [15]. This measured energy is then fed to a classical optimizer, which varies the parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) to minimize the energy. The variational principle guarantees that the minimized energy is an upper bound to the true ground state energy. A significant theoretical appeal is that for certain problems, evaluating the expectation value on a quantum computer can offer an exponential speedup over classical computation, which struggles with the exponentially growing dimension of the Hamiltonian [15].

Diagram 1: The VQE hybrid quantum-classical feedback loop. The quantum processor evaluates the cost function, while a classical optimizer adjusts the parameters.

Resource Requirements and Performance Comparison

The choice between QPE and VQE is largely dictated by the available quantum hardware and the required level of accuracy. Their resource profiles are starkly different.

Qubit Count and Circuit Depth

Quantum Phase Estimation requires a significant number of qubits. This includes qubits to encode the molecular wavefunction (system qubits) and an additional "energy register" of ancilla qubits to achieve the desired precision. The circuit depth for QPE is exceptionally high, as it requires long, coherent sequences of controlled time-evolution gates, ( U = e^{-iHt} ).

In contrast, Variational Quantum Eigensolver circuits are relatively shallow and are designed to be executed on a number of qubits equal only to the number required to represent the molecular system (e.g., the number of spin-orbitals). This makes VQE a primary candidate for NISQ devices, albeit with the caveat that the entire circuit must be executed thousands to millions of times to achieve sufficient measurement statistics for the classical optimizer.

Error Resilience and Hardware Demands

QPE is not error-resilient. It demands fault-tolerant quantum computation through quantum error correction, as even small errors in the phase estimation process can lead to incorrect results. Its stringent requirement for long coherence times is a key reason it is considered a long-term algorithm.

VQE is notably more resilient to certain errors. As a variational algorithm, it can potentially find a solution even if the quantum hardware introduces coherent errors, provided the classical optimizer can converge to parameters that compensate for these errors. However, its performance is still degraded by high levels of noise, which can lead to barren plateaus in the optimization landscape or incorrect energy estimations.

Table 1: Comparative Resource Analysis of QPE vs. VQE

| Feature | Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) | Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithmic Type | Deterministic, fault-tolerant | Hybrid, heuristic [15] |

| Theoretical Guarantee | Exact, provable performance | Variational bound, few rigorous guarantees [15] |

| Qubit Count | High (system + ancilla qubits) | Low (system qubits only) |

| Circuit Depth | Very high (long, coherent evolution) | Low to moderate (shallow ansatz circuits) |

| Error Resilience | Requires full error correction | Inherently more resilient to some errors |

| Hardware Era | Fault-tolerant future | NISQ-era [15] |

| Classical Overhead | Low (post-processing) | Very high (optimization loop) |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility and rigorous comparison, the following experimental protocols should be adhered to when benchmarking these algorithms.

Protocol for VQE Energy Estimation

- Problem Formulation: Map the electronic structure problem of the target molecule (e.g., LiH, BeHâ‚‚) to a qubit Hamiltonian using a transformation such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev.

- Ansatz Selection: Choose a parameterized wavefunction ansatz. Common choices include the Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) ansatz or hardware-efficient ansatzes.

- Initial Parameterization: Set initial parameters, which can be random, based on classical methods, or from a previously known good point.

- Quantum Expectation Measurement: Execute the parameterized quantum circuit on the target device or simulator. Measure the expectation values of the Hamiltonian terms. This step must be repeated many times to achieve a statistically precise result.

- Classical Optimization: Feed the computed energy to a classical optimizer (e.g., gradient descent, SPSA). The optimizer proposes new parameters to lower the energy.

- Convergence Check: Iterate steps 4 and 5 until the energy change between iterations falls below a predefined threshold or a maximum number of iterations is reached.

Protocol for QPE Energy Estimation

- Hamiltonian Compilation: Decompose the time-evolution operator ( e^{-iHt} ) into a sequence of native quantum gates. This is a non-trivial step known as Hamiltonian simulation.

- State Preparation: Prepare an initial state that has a high overlap with the true ground state. The success probability of QPE depends on this overlap.

- QPE Circuit Execution: Construct and run the full QPE circuit, which includes the ancilla register and the controlled-( e^{-iHt} ) operations.

- Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT): Apply the inverse QFT to the ancilla register to transform the phase information into a measurable bitstring.

- Readout and Interpretation: Measure the ancilla qubits. The resulting bitstring directly encodes an approximation of the energy eigenvalue.

Diagram 2: The step-by-step workflow of the Quantum Phase Estimation algorithm, highlighting its deterministic structure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential "research reagents"—the algorithmic and physical components—required to conduct experiments with QPE and VQE.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Hamiltonian Simulation Experiments

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Qubit Architecture | Physical platform for computation. | Superconducting qubits, trapped ions. Must meet coherence time and gate fidelity requirements. |

| Classical Optimizer | Finds parameters that minimize VQE energy. | Gradient-based (BFGS, Adam), gradient-free (SPSA, NFT). Critical for VQE convergence [15]. |

| Quantum Ansatz | Parameterized circuit for VQE trial wavefunction. | Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC), Hardware-Efficient Ansatz. Governes expressibility and trainability. |

| Hamiltonian Mapping | Translates molecular Hamiltonian to qubit form. | Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev, Parity transformations. Affects qubit connectivity and gate count. |

| Error Mitigation | Post-processing technique to improve raw results. | Zero-Noise Extrapolation, Readout Error Mitigation. Essential for accurate results on NISQ hardware. |

| Quantum Simulator | Software for algorithm design and validation. | Qiskit, Cirq, PennyLane. Allows for testing protocols without physical hardware access. |

| Junipediol A | Junipediol A | Research-grade Junipediol A, a natural angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or diagnostic use. |

| 8,3'-Diprenylapigenin | 8,3'-Diprenylapigenin | Research-grade 8,3'-Diprenylapigenin, a prenylated flavonoid. Study its potential bioactivities. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

The comparative analysis reveals that VQE and QPE are not direct competitors but are specialized for different technological eras and research objectives. VQE represents a pragmatic, though heuristic, pathway to exploring quantum chemistry on near-term devices, offering the critical advantage of shorter circuits and inherent error resilience at the cost of high classical optimization overhead and a lack of performance guarantees [15]. Its value lies in enabling early experimentation and validation of quantum approaches to chemistry problems like modeling LiH and BeHâ‚‚.

Conversely, QPE remains the long-term, gold-standard for high-precision quantum chemistry simulations, promising exact results with provable efficiency. Its implementation is conditional on the arrival of large-scale, fault-tolerant quantum computers.

For research teams today, the strategic path involves using VQE to build expertise, develop algorithms, and tackle small-scale problems on existing hardware, while simultaneously using classical simulations to refine QPE techniques for the fault-tolerant future. This dual-track approach ensures that the scientific community is prepared to leverage the full power of quantum computation as hardware capabilities continue to mature.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of leading surface code compilation approaches, focusing on their performance in simulating molecular systems such as LiH, BeH₂, and H₆. For researchers in quantum chemistry and drug development, selecting the optimal compilation strategy is crucial for managing the substantial resource requirements of fault-tolerant quantum algorithms.

Surface code quantum computing, particularly through lattice surgery, has emerged as a leading framework for implementing fault-tolerant quantum computations. The compilation process, which translates high-level quantum algorithms into low-level, error-corrected hardware instructions, presents significant trade-offs between physical qubit count (space) and execution time. Two primary families of surface code compilation exist: one based on serializing input circuits by eliminating all Clifford gates, and another involving direct compilation from Clifford+T to lattice surgery operations [8]. The choice between these approaches profoundly impacts the feasibility of quantum simulations on near-term error-corrected hardware, especially for quantum chemistry applications where resource efficiency is paramount.

Core Compilation Methodologies

Serialized Clifford Elimination

This method transforms input circuits by removing all Clifford gates, which are then reincorporated through classical post-processing. The resulting circuits consist primarily of multi-body Pauli measurements and magic state injections for T gates.

- Key Principle: Clifford operations are deferred to the end of the circuit and merged with final measurements [16].

- Hardware Mapping: Optimized for native multi-body measurement instruction sets available in surface code architectures.

- Expected Performance: Traditionally considered optimal for circuits with low degrees of logical parallelism [8].

Direct Clifford+T Compilation

This approach compiles circuits directly to lattice surgery operations without first eliminating Clifford gates, maintaining more of the original circuit's structure.

- Key Principle: Preserves logical parallelism present in the original algorithm [8].

- Hardware Mapping: Requires more sophisticated routing and scheduling of lattice surgery operations.

- Expected Performance: Particularly beneficial for circuits exhibiting high degrees of logical parallelism [8].

Quantum Resource Comparison for Molecular Simulations

The resource requirements for simulating molecular systems vary significantly based on both the compilation strategy and the specific simulation algorithm employed.

Resource Estimates for Hamiltonian Simulation Algorithms

Table 1: Quantum Resource Comparison for Hamiltonian Simulation Approaches

| Simulation Algorithm | Compilation Approach | Optimal Use Case | Key Performance Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Signal Processing | Serialized Clifford Elimination | Circuits with low logical parallelism | Traditional approach for high-precision simulation [8] |

| Trotter-Suzuki | Direct Clifford+T Compilation | Circuits with high logical parallelism | Orders of magnitude improvement for certain applications [8] |

Application-Specific Performance for Molecular Systems

Recent research on Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) has demonstrated dramatic resource reductions for molecular simulations.

Table 2: Resource Reductions for State-of-the-Art ADAPT-VQE on Molecular Systems [17]

| Molecular System | Qubit Count | CNOT Count Reduction | CNOT Depth Reduction | Measurement Cost Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH | 12 qubits | Up to 88% | Up to 96% | Up to 99.6% |

| H₆ | 12-14 qubits | Up to 88% | Up to 96% | Up to 99.6% |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 12-14 qubits | Up to 88% | Up to 96% | Up to 99.6% |

These improvements, achieved through novel operator pools and improved subroutines, make the Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool-based ADAPT-VQE significantly more efficient than both the original ADAPT-VQE and the Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles ansatz, the most widely used static VQE approach [17].

Architectural Considerations: Data Block Designs for Lattice Surgery

The physical layout of logical qubits, known as data blocks, significantly impacts performance in lattice surgery-based architectures. Different designs offer distinct space-time trade-offs.

Table 3: Comparison of Surface Code Data Block Architectures [16]

| Data Block Design | Tile Requirement for n Qubits | Maximum Operation Cost | Key Characteristics | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compact Block | 1.5n + 3 tiles | 9 (code cycles) | Space-efficient but limited operation access | Qubit-constrained computations |

| Intermediate Block | 2n + 4 tiles | 5 (code cycles) | Linear layout with flexible auxiliary regions | Balanced space-time tradeoffs |

| Fast Block | 2 tiles per qubit | Lowest time cost | Direct Y operation access | Time-critical applications |

Figure 1: Surface Code Compilation and Optimization Workflow

Operation Costs in Different Architectures

The cost of performing logical operations varies significantly across data block designs:

- Compact Data Blocks: Require patch rotations (3) to access X measurements and additional resources for Y operations, with worst-case costs reaching 9 [16].

- Intermediate Data Blocks: Eliminate the need for rotating patches back to their original position, reducing maximum operation cost to 5 [16].

- Fast Data Blocks: Enable direct access to both Z and X edges by dedicating 2 tiles per qubit, minimizing time costs for all operations [16].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Resource Estimation Methodology

Standardized approaches for comparing surface code compilation techniques include:

- Circuit Transformation: Converting input circuits to Pauli product measurements via lattice surgery operations [16].

- Space-Time Volume Calculation: Multiplying physical qubit count by execution time (in code cycles) for comprehensive comparison [16].

- Architecture-Aware Scheduling: Modeling magic state production and consumption rates based on distillation block throughput [16].

Key Experimental Considerations

When evaluating compilation approaches for specific applications:

- Algorithm-Specific Optimization: The optimal scheme depends on whether Hamiltonian simulation uses quantum signal processing or Trotter-Suzuki algorithms [8].

- High-Level Circuit Analysis: Smart compilers should predict optimal schemes based on logical circuit properties including average circuit density, logical qubit count, and T fraction [8].

- Ancilla Management: Proper handling of auxiliary qubits is crucial for measuring products of Pauli operators on different qubits, the fundamental operation in lattice surgery [16].

Figure 2: Decision Framework for Selecting Compilation Approaches

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Components for Surface Code Quantum Computing Research

| Component | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Code Patches | Basic units encoding logical qubits | Implemented using tile-based layout with distinct X/Z boundaries [16] |

| Magic State Distillation Blocks | Produce high-fidelity non-Clifford states | Crucial for implementing T gates; layout affects computation speed [16] |

| Lattice Surgery Protocols | Enable logical operations between patches | Based on merging and splitting patches with appropriate measurements [16] |

| Pauli Product Measurement | Fundamental operation in lattice surgery | Measures multi-qubit Pauli operators via patch deformation and ancillas [16] |

| Code Cycle | Basic time unit for error correction | Approximately corresponds to surface code cycle time; measured in [16] |

| Corylifol C | Corylifol C Research Compound|Psoralea corylifolia | Corylifol C is a natural flavonoid with researched radioprotective properties. This product is for research use only (RUO) and not for human consumption. |

| Methyl isodrimeninol | Methyl Isodrimeninol| | Methyl Isodrimeninol is a drimane sesquiterpenoid derivative for antifungal and phytopathological research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The optimal surface code compilation strategy depends heavily on specific application requirements. For molecular simulations using variational algorithms like ADAPT-VQE, recent advances have demonstrated order-of-magnitude improvements in resource requirements [17]. For Hamiltonian simulation, the choice between serialized Clifford elimination and direct Clifford+T compilation depends on the algorithm type, with Trotterization benefiting significantly from direct compilation for certain applications [8].

Future research directions include developing adaptive compilers that automatically select optimal strategies based on high-level circuit characteristics, and exploring hybrid approaches that dynamically switch between compilation methods within a single computation. For researchers targeting molecular systems like LiH, BeH₂, and H₆, leveraging state-of-the-art compilation approaches with optimized operator pools can reduce quantum resource requirements by orders of magnitude, bringing practical quantum advantage in chemical simulation closer to realization.

Quantum Resource Estimation (QRE) has emerged as a critical discipline for evaluating the practical viability of quantum algorithms before the advent of large-scale fault-tolerant quantum computers. By providing forecasts of qubit counts, circuit depth, and execution time, QRE frameworks enable researchers to make strategic decisions about algorithm selection and hardware investments. This guide objectively compares the performance of leading QRE approaches, with a specific focus on their application to the LiH, BeH₂, and H₆ molecules—benchmark systems in quantum computational chemistry.

Quantum Resource Estimation is the process of determining the computational resources required to execute a quantum algorithm on a fault-tolerant quantum computer. This includes estimating the number of physical qubits, quantum gate counts, circuit depth, and total execution time, all while accounting for the substantial overheads introduced by quantum error correction [18] [19]. As quantum computing transitions from theoretical research to practical application, QRE has become indispensable for assessing which problems might be practically solvable on future quantum hardware and for guiding the development of more resource-efficient quantum algorithms.

Comparative Analysis of QRE Frameworks and Performance

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of different resource estimation approaches as applied to molecular simulations.

| Framework/Algorithm | Key Metrics for Target Molecules | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE [13] | LiH, BeH₂, H₆ (12-14 qubit representations): CNOT count, CNOT depth, measurement costs | Reductions vs. earlier versions: CNOT count: ≤88%, CNOT depth: ≤96%, measurement costs: ≤99.6% |

| Graph Transformer-based Prediction [20] | General circuit execution time prediction | Simulation time prediction R² > 95%; Real quantum computer execution time prediction R² > 90% |

| Azure Quantum Resource Estimator [19] | Logical & physical qubits, runtime for fault-tolerant algorithms | Enables space-time tradeoff analysis; Models resources based on specified qubit technologies and QEC schemes |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Algorithm-Specific Resource Reduction

The dramatic resource reductions reported for the CEO-ADAPT-VQE algorithm were achieved through a specific experimental protocol [13]:

- Operator Pool Innovation: A novel "Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool" was introduced, which is more chemically motivated than standard pools.

- Improved Subroutines: Key quantum subroutines within the ADAPT-VQE algorithm were optimized to reduce gate counts and circuit depth.

- Benchmarking: The optimized algorithm was run on simulations of the LiH, BeH₂, and H₆ molecules, and its resource consumption was directly compared against earlier versions of ADAPT-VQE and the standard Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) ansatz.

Execution Time Prediction Model

The graph transformer-based model for predicting quantum circuit execution time was developed and validated as follows [20] [21]:

- Data Collection: Over 1,510 quantum circuits (ranging from 2 to 127 qubits) were executed on both simulators and real quantum computers to gather ground-truth execution time data.

- Feature Extraction: The model utilizes two types of circuit information: 1) Global features (e.g., total qubit count, gate counts) and 2) Graph features (the topological structure of the circuit).

- Active Learning for Real Hardware: Due to limited access to quantum computers, an active learning approach was used to select the most informative 340 circuit samples for building the prediction model for real quantum computer execution times.

- Evaluation: Model accuracy was evaluated using the R-squared metric, comparing predicted execution times against actual measured times.

General Fault-Tolerant Resource Estimation

The Azure Quantum Resource Estimator and similar frameworks operate through a multi-layered process [19] [22]:

- Logical Resource Estimation: The input algorithm (e.g., written in Q#) is analyzed to determine basic resource needs (logical qubits, logical operations) without error correction.

- Physical Resource Mapping: A specific quantum error correction code (e.g., surface code) and target hardware parameters (e.g., gate fidelities, operation speeds) are selected.

- Overhead Accounting: The physical qubits and extra circuit depth required to implement fault-tolerant operations are calculated. This includes estimating the massive resources required for T-state factories.

- Trade-off Analysis: The tool can generate multiple estimates under different assumptions (e.g., different code distances, hardware parameters) to illustrate resource trade-offs.

Visualizing the Quantum Resource Estimation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the multi-stage process of estimating resources for a quantum algorithm, from a high-level problem statement to a detailed physical resource count.

For researchers embarking on quantum resource estimation, the following tools and concepts are indispensable.

| Tool / Concept | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| Azure Quantum Resource Estimator [19] | Estimates logical/physical qubits & runtime for Q# programs on fault-tolerant hardware. |

| Graph Transformer Models [20] | Predicts execution time for quantum circuits on simulators and real quantum computers. |

| T-State Factories / Distillation Units [19] | Produces high-fidelity T-gates, a major contributor to physical resource overhead. |

| Active Learning Sampling [20] | Selects the most informative quantum circuits for training prediction models when access to real quantum hardware is limited. |

| Space-Time Diagrams [19] | Visualizes the trade-off between the number of qubits (space) and the algorithm runtime (time). |

The comparative analysis reveals that no single QRE framework dominates all metrics. The CEO-ADAPT-VQE algorithm demonstrates that innovative algorithm design can reduce quantum computational resources by orders of magnitude for specific molecular simulations like LiH, BeH₂, and H₆ [13]. In parallel, general-purpose estimation tools like the Azure Quantum Resource Estimator provide comprehensive platforms for analyzing a wide range of algorithms under customizable hardware assumptions [19]. Finally, data-driven prediction models offer a promising path for accurately forecasting execution times on current and near-term quantum devices [20].