Qubit-ADAPT-VQE vs. Fermionic ADAPT-VQE: A Comparative Guide for Quantum-Enhanced Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of two leading adaptive variational quantum eigensolvers (VQEs)—Qubit-ADAPT-VQE and Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE—tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE vs. Fermionic ADAPT-VQE: A Comparative Guide for Quantum-Enhanced Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of two leading adaptive variational quantum eigensolvers (VQEs)—Qubit-ADAPT-VQE and Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE—tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. We explore their foundational principles in electronic structure theory, detail their methodological differences in ansatz construction and operator pools, and analyze their performance in terms of circuit efficiency, convergence speed, and measurement costs. Practical troubleshooting advice and optimization strategies for noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) hardware are discussed, alongside rigorous validation through molecular benchmarks like LiH and BeH2. The review concludes by synthesizing key trade-offs and future directions, highlighting the potential of these algorithms to revolutionize molecular simulation in biomedical research.

Foundations of Adaptive VQE: From Fermionic Operators to Qubit Excitations

The Electronic Structure Problem and the VQE Solution

The electronic structure problem, centered on solving the electronic Schrödinger equation to determine the energy and properties of molecules, is a fundamental challenge in quantum chemistry and materials science [1]. The complexity of this problem grows exponentially with system size, making it intractable for classical computers for all but the smallest molecules [2]. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed to address this challenge on near-term quantum hardware [2] [1].

VQE operates on the variational principle, using a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) to prepare trial wavefunctions whose energy is minimized via a classical optimization loop [3] [4]. Its adaptability to noisy hardware makes it particularly promising for the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era [5]. Among various VQE formulations, adaptive versions like ADAPT-VQE dynamically construct the circuit ansatz, offering significant advantages in accuracy, circuit depth, and trainability over fixed-structure approaches [2].

ADAPT-VQE: A Comparative Framework

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a significant advancement over standard VQE. Unlike fixed ansätze, ADAPT-VQE iteratively constructs a problem-tailored circuit by dynamically adding unitary operations from a predefined "operator pool" [2] [3]. At each iteration, the algorithm selects the operator with the largest energy gradient, adds it to the circuit with a new variational parameter, and re-optimizes all parameters [3]. This process continues until a convergence criterion is met [3].

Two major variants have emerged, distinguished by their operator pools:

- Fermionic ADAPT-VQE: Uses pools of fermionic excitation operators (e.g., singles and doubles), closely related to traditional unitary coupled cluster (UCC) theory [3] [4].

- Qubit ADAPT-VQE: Employs pools of purely qubit operators, such as Pauli strings, offering potential hardware efficiency [2].

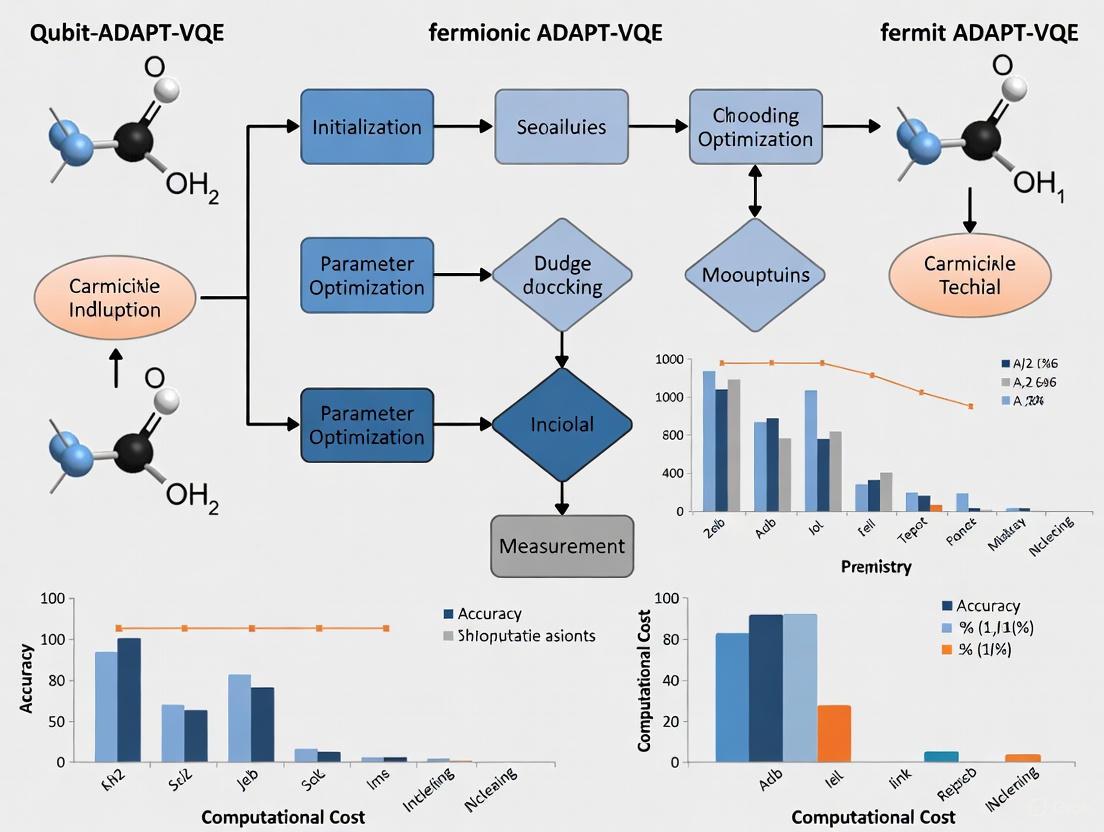

The following workflow diagram illustrates the iterative structure of the ADAPT-VQE algorithm:

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Extensive numerical simulations reveal significant performance differences between ADAPT-VQE variants. The table below summarizes key metrics for the CEO-ADAPT-VQE* (a state-of-the-art qubit-based method) compared to GSD-ADAPT-VQE (a fermionic approach) for molecular systems of 12-14 qubits [2].

Table 1: Resource Comparison for Achieving Chemical Accuracy

| Molecule | Qubits | Algorithm | CNOT Count | CNOT Depth | Measurement Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH | 12 | GSD-ADAPT-VQE | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| LiH | 12 | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | Reduced by 88% | Reduced by 96% | Reduced by 99.6% |

| H6 | 12 | GSD-ADAPT-VQE | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| H6 | 12 | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | Reduced by 85% | Reduced by 96% | Reduced by 99.4% |

| BeH2 | 14 | GSD-ADAPT-VQE | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| BeH2 | 14 | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | Reduced by 73% | Reduced by 92% | Reduced by 98.6% |

Beyond direct ADAPT-VQE comparisons, qubit-based CEO-ADAPT-VQE* also outperforms the traditional unitary coupled cluster singles and doubles (UCCSD) ansatz—the most widely used static VQE approach—across all relevant metrics [2]. It achieves a five-order-of-magnitude decrease in measurement costs compared to other static ansätze with similar CNOT counts [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Ansatz Construction Protocols

The core experimental difference between qubit and fermionic ADAPT-VQE lies in their operator pools and implementation:

Fermionic ADAPT-VQE Protocol [3]:

- Operator Pool Generation: Construct single (

a^p†a_q) and double (a^p†a_q†a_r a_s) fermionic excitation operators from a reference state (typically Hartree-Fock). - Gradient Calculation: Compute gradients

∂E/∂θ_ifor all pool operatorsA_iusing∂E/∂θ_i = <ψ|[H, A_i]|ψ>. - Operator Selection: Identify the operator with the largest gradient magnitude.

- Ansatz Update: Append the selected operator

exp(θ_i A_i)to the circuit. - Parameter Optimization: Re-optimize all parameters in the expanded ansatz using VQE.

- Convergence Check: Repeat until gradient norms fall below threshold (e.g., 10â»Â³).

Qubit ADAPT-VQE Protocol [2]:

- Qubit Operator Pool: Define pool using native qubit operators, such as the novel Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool.

- Commutator-Based Selection: Calculate gradients through qubit operator commutators with the Hamiltonian.

- Hardware-Efficient Implementation: Exploit qubit-wise commutativity for measurement reduction.

- Circuit Construction: Build circuits directly optimized for quantum hardware connectivity.

Measurement Optimization Techniques

Advanced measurement strategies are crucial for practical implementation:

Reused Pauli Measurements [5]: Pauli measurement outcomes from VQE parameter optimization are reused in subsequent operator selection steps, reducing shot requirements by approximately 60-70%.

Variance-Based Shot Allocation [5]: Shots are distributed among Hamiltonian terms based on their variance, achieving 6-51% reduction in shot requirements compared to uniform allocation.

Qubit-Wise Commutativity Grouping [5]: Operators are grouped by commutation properties to enable simultaneous measurement, further reducing circuit executions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Components

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Component | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pool | Defines search space for ansatz construction | Fermionic: UCCSD excitations; Qubit: CEO pool [2] |

| Qubit Hamiltonian | Encodes molecular electronic structure in qubit space | Jordan-Wigner/Bravyi-Kitaev transformation of electronic Hamiltonian [1] [3] |

| Variational Minimizer | Optimizes ansatz parameters | Classical optimizers (L-BFGS-B, COBYLA) [1] [3] |

| Quantum Simulator/Device | Executes quantum circuits and measurements | Statevector simulators (Qulacs) or IBM quantum processors [1] [3] |

| Measurement Protocol | Manages shot allocation and term grouping | Variance-based allocation, qubit-wise commutativity grouping [5] |

| 4-Hydroxyhippuric acid | 4-Hydroxyhippuric Acid|High-Purity Reference Standard | |

| Complanatoside A | Complanatoside A, MF:C27H30O18, MW:642.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative analysis between qubit and fermionic ADAPT-VQE reveals a clear trajectory toward hardware-efficient algorithm design. Qubit-based approaches, particularly those employing novel operator pools like the Coupled Exchange Operator pool, demonstrate substantial advantages in reducing quantum resource requirements—achieving up to 96% reduction in CNOT depth and 99.6% reduction in measurement costs compared to fermionic counterparts [2].

These advancements are critical for practical quantum advantage in electronic structure calculations, particularly as molecular system size increases. The integration of measurement reuse protocols and variance-based shot allocation further enhances the feasibility of these methods on current NISQ devices [5]. While fermionic ADAPT-VQE maintains stronger connections to traditional quantum chemistry frameworks, the resource efficiencies of qubit-based approaches position them as promising candidates for scaling quantum computational chemistry to clinically and industrially relevant molecular systems.

For researchers in drug development and materials science, these developments signal a important maturation of quantum computational tools, potentially enabling more accurate modeling of molecular interactions and reaction mechanisms that are currently beyond classical computational reach.

Core Principles of the ADAPT-VQE Algorithm and Ansatz Construction

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a significant advancement in quantum computational chemistry, specifically designed to address the limitations of pre-defined variational ansätze in the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) framework. Unlike standard VQE that uses a fixed circuit structure, ADAPT-VQE dynamically constructs a problem-tailored ansatz by iteratively selecting operators from a predefined pool, leading to enhanced performance, faster convergence, and reduced quantum resource requirements [3] [2]. This adaptive construction is particularly valuable for simulating molecular systems on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, where circuit depth and gate count are critical constraints.

The algorithm's core innovation lies in its iterative, greedy approach to ansatz development. Beginning typically with a Hartree-Fock reference state, ADAPT-VQE grows the ansatz circuit by appending parametrized unitary gates generated by operators selected from an operator pool based on the magnitude of their energy gradient contribution [3] [6]. This method ensures that the circuit structure is specifically adapted to the molecular Hamiltonian of interest, often resulting in shallower circuits and improved trainability compared to static ansätze like the Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) [2] [7].

Core Algorithmic Principles and Workflow

Fundamental Mechanism of ADAPT-VQE

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm functions through a structured, iterative process that bridges quantum measurements and classical optimization. Its effectiveness stems from a closed-loop feedback mechanism between the quantum processor and a classical computer [3] [2]:

- Initialization: The algorithm starts with a simple reference state, usually the Hartree-Fock state, which can be prepared using a constant-depth quantum circuit.

- Gradient Evaluation: For the current variational state, the energy gradient with respect to each operator in a predefined pool is computed or estimated. This gradient reflects the potential energy reduction achievable by adding each corresponding gate to the circuit.

- Operator Selection: The operator with the largest gradient magnitude is identified and selected. This greedy selection ensures the most significant improvement per iteration.

- Ansatz Growth and Optimization: A new parameterized gate, generated by exponentiating the selected operator, is appended to the quantum circuit. The entire set of parameters in the newly expanded ansatz is then optimized classically to minimize the expectation value of the Hamiltonian.

- Convergence Check: The process repeats from step 2 until the norm of the gradient vector falls below a predefined tolerance threshold, indicating that the ansatz has sufficiently approximated the ground state [3].

A key conceptual strength of ADAPT-VQE is its "problem-tailed" nature. Unlike fixed ansätze that maintain the same structure regardless of the target molecule, ADAPT-VQE grows an ansatz specifically adapted to the problem's Hamiltonian, which often avoids redundant parameters and gates that contribute minimally to the accuracy of the final state [2] [6].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the iterative workflow of the ADAPT-VQE algorithm:

Comparative Analysis: Qubit-ADAPT-VQE vs. Fermionic ADAPT-VQE

The performance and resource efficiency of ADAPT-VQE are heavily influenced by the choice of operator pool. The primary distinction lies between Fermionic ADAPT-VQE and its variant, Qubit-ADAPT-VQE.

Fermionic ADAPT-VQE employs a pool composed of fermionic excitation operators, typically the single and double excitations found in UCCSD. These operators (e.g., ( \hat{a}p^\dagger \hat{a}q ) and ( \hat{a}p^\dagger \hat{a}q^\dagger \hat{a}r \hat{a}s )) are physically motivated and directly related to the electronic excitations of the system [3] [7]. The resulting ansatz is constructed by exponentiating these fermionic operators, which then need to be mapped to quantum gates using techniques like the Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation.

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE utilizes a pool built directly from qubit operators, such as Pauli strings or "qubit excitation evolutions" [8] [9]. These operators obey qubit commutation relations rather than fermionic anti-commutation relations. While they may lack the direct physical interpretation of fermionic excitations, they are naturally more hardware-efficient. The ansatz is grown by appending the exponentials of these qubit operators, which often require asymptotically fewer gates to implement on a quantum device compared to their fermionic counterparts [8].

Performance and Resource Comparison

The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison of key performance metrics between Qubit- and Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE, based on data from numerical simulations for small molecules [2] [7].

| Performance Metric | Qubit-ADAPT-VQE | Fermionic ADAPT-VQE (GSD Pool) |

|---|---|---|

| Circuit Depth / CNOT Count | Order of magnitude reduction (e.g., ~88% lower for LiH) [9] | Significantly higher due to complex fermionic mappings [2] |

| Convergence Speed (Iterations) | Comparable or faster in some cases [8] | Generally requires more iterations to achieve similar accuracy [2] |

| Measurement Overhead | Favorable, scales linearly with qubit count for operator selection [9] | High, due to large pool size and complex measurements [2] |

| Expressivity & Accuracy | Capable of achieving chemical accuracy [8] [7] | Capable of achieving high, systematic accuracy [3] [8] |

| Hardware Efficiency | High; designed for NISQ devices with low gate overhead [9] | Lower; circuits can be too deep for current devices [9] |

Advanced Pool Designs and Recent Enhancements

Research into more efficient operator pools has led to significant resource reductions. The Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool is a novel design that has demonstrated dramatic improvements. When combined with other enhancements (an algorithm termed CEO-ADAPT-VQE*), simulations for molecules like LiH, H₆, and BeH₂ showed reductions in CNOT count by up to 88%, CNOT depth by up to 96%, and measurement costs by up to 99.6% compared to the original fermionic ADAPT-VQE [2].

Another strategy to manage resource requirements focuses on reducing the quantum measurement (shot) overhead. A 2025 proposal integrates two key techniques: reusing Pauli measurement outcomes from the VQE optimization in the subsequent operator selection step, and applying variance-based shot allocation to both Hamiltonian and gradient measurements. This combined approach significantly reduces the number of shots needed to achieve chemical accuracy while maintaining fidelity [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Protocol for ADAPT-VQE Simulation

A typical experimental workflow for conducting an ADAPT-VQE simulation, as implemented in software frameworks like InQuanto or PennyLane, involves several well-defined stages [3] [6]:

- System Definition: Define the molecular system by specifying atomic symbols and coordinates. Compute the electronic Hamiltonian in a chosen basis set (e.g., STO-3G) and active space approximation to reduce the qubit count.

- Operator Pool Preparation: Construct the operator pool. For Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE, this involves generating all unique single and double fermionic excitation operators from the reference state [3]. For Qubit-ADAPT-VQE, the pool is built from Pauli strings or qubit-excitation operators [9].

- Algorithm Configuration: Initialize the ADAPT-VQE algorithm by specifying the pool, initial state (e.g., Hartree-Fock), the qubit Hamiltonian, a classical minimizer (e.g., L-BFGS-B), and a convergence tolerance (e.g., 1e-3) [3].

- Iterative Ansatz Construction: Run the adaptive loop. In each iteration, the algorithm calculates the gradients for all operators in the pool, selects the operator with the largest gradient, adds its corresponding gate to the circuit with a new variational parameter, and optimizes all parameters [6].

- Result Analysis: Upon convergence, the final energy, optimized parameters, and the constructed ansatz circuit are retrieved for analysis [3].

Protocol for Comparative Studies

To objectively compare the performance of different ADAPT-VQE variants, such as Qubit-ADAPT versus Fermionic-ADAPT, the following controlled methodology is employed [2] [7]:

- Molecular Test Set: A set of small molecules (e.g., LiH, H₆, BeH₂) at various bond lengths, including both equilibrium and dissociated geometries, is selected to assess performance across different correlation regimes.

- Resource Metrics Tracking: For each algorithm variant, key metrics are recorded at the iteration where chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa error) is first achieved. These metrics include the number of variational parameters, the total number of CNOT gates, the CNOT depth of the circuit, and the estimated measurement cost (often proxied by the number of energy evaluations or required shots) [2].

- Classical Simulation: The experiments are typically performed using state-vector simulators to isolate algorithm performance from hardware noise. The energy error relative to the full configuration interaction (FCI) or exact diagonalization value is tracked throughout the optimization to monitor convergence [7].

Essential Research Toolkit

The table below catalogs the key computational "reagents" and tools essential for implementing and experimenting with ADAPT-VQE algorithms.

| Tool / Component | Function in ADAPT-VQE Protocol |

|---|---|

| Qubit Hamiltonian | The target operator whose ground state energy is being computed; derived from the electronic Hamiltonian of the molecule [3]. |

| Operator Pool | A predefined set of operators (e.g., fermionic excitations, Pauli strings) from which the ansatz is adaptively constructed [3] [9]. |

| Classical Optimizer | A classical algorithm (e.g., L-BFGS-B, SLSQP) used to minimize the energy by varying the parameters of the quantum circuit [3]. |

| State-Vector Simulator | A noise-free quantum simulator used for algorithm development, benchmarking, and validation of the ADAPT-VQE workflow [3] [7]. |

| Quantum Chemistry Package | Software (e.g., PennyLane, InQuanto) that provides functionalities for molecular Hamiltonian generation, Hartree-Fock state preparation, and excitation operator construction [3] [6]. |

| Convergence Tolerance | A numerical threshold (e.g., 1e-3) for the gradient norm that determines when the iterative ansatz-building process terminates [3]. |

| Acetyldihydromicromelin A | Acetyldihydromicromelin A, MF:C17H16O7, MW:332.3 g/mol |

| Rivulobirin B | Rivulobirin B, MF:C23H12O9, MW:432.3 g/mol |

ADAPT-VQE represents a powerful and flexible framework for quantum chemistry simulations on NISQ-era quantum hardware. Its core principle of iterative, adaptive ansatz construction offers a compelling advantage over static variational forms by systematically building compact, problem-tailored circuits. The choice between Fermionic and Qubit-based variants presents a clear trade-off: Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE is grounded in the well-established framework of quantum chemistry, while Qubit-ADAPT-VQE and its modern descendants like CEO-ADAPT-VQE demonstrate superior hardware efficiency, with orders-of-magnitude reduction in critical resources like CNOT gate count and measurement overhead [2] [9].

The ongoing development of more sophisticated operator pools and measurement strategies continues to push the boundaries of what is possible with these hybrid algorithms [10] [2]. As such, ADAPT-VQE and its variants remain at the forefront of the quest for practical quantum advantage in electronic structure calculations, providing researchers with a versatile and increasingly efficient toolkit for exploring complex molecular systems.

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a significant advancement in quantum computational chemistry, designed to construct problem-tailored ansätze for molecular simulations on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. Unlike fixed-structure ansätze, ADAPT-VQE grows its ansatz iteratively by selecting operators from a predefined pool based on an energy-gradient hierarchy [2] [11]. Within this framework, a fundamental distinction exists between Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE and its qubit-based counterparts, chiefly in the composition of the operator pool and the underlying physical motivation. The fermionic variant utilizes an operator pool composed of fermionic excitation evolutions—specifically, anti-Hermitian generators of the form ( \hat{\tau}i = \hat{T}i - \hat{T}i^\dagger ), where ( \hat{T}i ) are fermionic excitation operators [12] [13]. This approach is directly inspired by unitary coupled cluster (UCC) theory, ensuring that the constructed ansatz respects the physical symmetries of electronic wavefunctions, such as particle number conservation and fermionic anti-symmetry [12]. This paper delineates the comparative performance, resource requirements, and practical applications of Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE against other adaptive protocols, situating its value within the broader research context of Qubit-ADAPT-VQE comparisons.

Performance and Resource Comparison

The following tables synthesize key performance metrics from recent studies, comparing Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE against Qubit-ADAPT-VQE and the more recent Qubit-Excitation-Based (QEB)-ADAPT-VQE.

Table 1: Algorithm Resource Comparison for Selected Molecules (at chemical accuracy)

| Molecule (Qubits) | Algorithm | CNOT Count | Circuit Depth | Number of Parameters | Number of Iterations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH (12 qubits) | Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE [2] [12] | ~880 (Baseline) | Deep | Fewer | Fewer |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE [9] [12] | ~100 (↓88%) | Shallower | Higher | Higher | |

| QEB-ADAPT-VQE [12] | Low | Very Shallow | Moderate | Moderate | |

| H₆ (12 qubits) | Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE [2] [12] | ~750 (Baseline) | Deep | Fewer | Fewer |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE [9] [2] | ~90 (↓88%) | Shallower (↓96% depth) | Higher | Higher | |

| QEB-ADAPT-VQE [12] | Low | Very Shallow | Moderate | Moderate | |

| BeHâ‚‚ (14 qubits) | Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE [2] | ~1200 (Baseline) | Deep | Fewer | - |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE [9] [2] | ~140 (↓88%) | Shallower (↓92% depth) | Higher | - |

Table 2: Qualitative Algorithm Comparison

| Feature | Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE | Qubit-ADAPT-VQE | QEB-ADAPT-VQE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operator Pool | Fermionic excitation evolutions [12] | Pauli string exponentials [9] [12] | Qubit excitation evolutions [12] |

| Physical Motivation | High (direct from UCC) [12] [13] | Low (hardware-efficient) [9] | Moderate (inspired by fermionic structure) [12] |

| Circuit Efficiency | Lower (deeper circuits) [2] [12] | High (shallower circuits) [9] [2] | Highest (very shallow circuits) [12] |

| Convergence Speed | Faster (fewer iterations) [12] | Slower (more iterations) [12] | Intermediate [12] |

| Optimization Landscape | Smoother, fewer parameters [12] | More parameters, potential barren plateaus [2] | - |

| Measurement Cost | High (for fermionic gradients) [2] | Lower [9] | - |

The data reveals a clear trade-off: while Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE converges in fewer iterations due to its physically motivated operator selection [12], the resulting quantum circuits are significantly deeper than those produced by qubit-based protocols [2] [12]. For example, Qubit-ADAPT-VQE can reduce CNOT counts by up to 88% and circuit depth by up to 96% compared to the fermionic original [2]. The more recent QEB-ADAPT-VQE aims to bridge this gap, offering circuit efficiency competitive with Qubit-ADAPT-VQE while requiring fewer iterations and parameters to converge [12].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core Workflow of ADAPT-VQE

The fundamental adaptive workflow is consistent across different variants [11] [13]. The primary differences lie in the composition of the operator pool and the implementation of the ansatz elements.

Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE Specifics

- Operator Pool: The standard pool consists of generalized single and double (GSD) fermionic excitations [2] [12]. The anti-Hermitian generators are of the form ( \hat{\tau}i^{pq} = \hat{a}p^\dagger \hat{a}q - \hat{a}q^\dagger \hat{a}p ) for singles and ( \hat{\tau}i^{pqrs} = \hat{a}p^\dagger \hat{a}q^\dagger \hat{a}r \hat{a}s - \text{h.c.} ) for doubles, where ( \hat{a}^\dagger ) and ( \hat{a} ) are fermionic creation and annihilation operators [12] [13].

- Ansatz Element Implementation: Each selected operator is exponentiated to form a unitary gate: ( e^{\thetai \hat{\tau}i} ) [11]. On a quantum computer, these fermionic operators must be mapped to qubit gates using a transformation like the Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev encoding [12] [13]. The Jordan-Wigner transformation, while straightforward, often leads to long strings of Pauli operators, resulting in deeper circuits compared to more direct qubit ansatz elements [12].

Comparative Studies Methodology

Performance benchmarks are typically conducted using classical simulators for small molecules like LiH, H₆, and BeH₂ [2] [12]. Key methodological steps include:

- Molecular Hamiltonian Preparation: The electronic Hamiltonian is generated for a specific molecular geometry and then mapped to a qubit Hamiltonian using a chosen encoding (e.g., Jordan-Wigner) [12].

- Algorithm Execution: Each ADAPT-VQE variant is run independently, growing its ansatz until a convergence criterion (e.g., chemical accuracy of 1.0 mHa) is met [2] [12].

- Metrics Collection: For each iteration, researchers track the energy error, the number of CNOT gates, the circuit depth, and the number of variational parameters [9] [2] [12]. The total quantum resource cost, especially the number of measurements required for gradient estimation, is also a critical metric [2].

Technical Implementation and Physical Motivations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for ADAPT-VQE Experiments

| Item | Function & Description | Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Initial State | A reference wavefunction (e.g., Hartree-Fock) to initialize the quantum circuit [11] [14]. | Can be improved using Unrestricted HF (UHF) natural orbitals for better initial overlap with the true ground state [11] [14]. |

| Operator Pool | A predefined set of operators from which the ansatz is built [2] [12]. | Composed of fermionic excitation operators (e.g., GSD), ensuring physicality [2] [12]. |

| Qubit Mapping | A method to encode fermionic operators into qubit (Pauli) operators [12] [13]. | Jordan-Wigner is commonly used, but its overhead contributes to deeper circuits [12]. |

| Measurement Strategy | Techniques to estimate energy expectation values and gradients [2]. | Requires measuring fermionic gradient terms, which can be costly [2]. |

| Classical Optimizer | An algorithm to variationally update the parameters {θ} to minimize energy [13]. |

Gradient-based optimizers are often more efficient than gradient-free methods [13]. |

| 2-Hydroxydiplopterol | 2-Hydroxydiplopterol|RUO | 2-Hydroxydiplopterol is a hopanoid triterpenoid for membrane research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Angustin B | Angustin B, CAS:1415795-51-5, MF:C17H16O7, MW:332.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Logical Pathway of Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual and technical pathway that defines the Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE protocol, highlighting its strong connection to electronic structure theory.

Discussion: Trade-offs and Application Domains

The choice between Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE and qubit-based variants is not a matter of superiority but of aligning the algorithm's strengths with the problem's requirements.

Strengths of Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE:

- Physical Interpretability: The ansatz elements correspond directly to electronic excitations, providing a clear and chemically intuitive picture of electron correlation effects [12]. The resulting wavefunction is inherently N-representable, meaning it consistently corresponds to a physical fermionic system [12].

- Robust Optimization: The ansatz grows in a physically structured space, which may help mitigate issues like barren plateaus and lead to a smoother optimization landscape compared to hardware-efficient ansätze [2] [14].

- Proven Formal Grounding: The method is rooted in the well-established UCC theory, providing a strong formal connection to classical quantum chemistry [13].

Weaknesses and Trade-offs:

- Circuit Inefficiency: The primary drawback is the high CNOT count and circuit depth resulting from the implementation of fermionic operators via transformations like Jordan-Wigner [2] [12]. This makes it more susceptible to noise on current hardware.

- Measurement Overhead: The fermionic pool can lead to a larger measurement overhead for gradient calculations compared to some qubit-adapted pools [2].

Application Domains: Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE is particularly well-suited for strongly correlated systems where classical methods like restricted UCCSD often fail [11]. Its physical nature makes it an excellent tool for algorithm development and conceptual studies where interpretation is key. In contrast, qubit-based ADAPT-VQEs (Qubit- and QEB-) are likely more practical for near-term hardware execution due to their dramatically lower circuit depths and gate counts, which is a critical advantage in the NISQ era [9] [2] [12].

Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE remains a cornerstone algorithm in quantum computational chemistry due to its strong physical motivations and robust convergence properties. It leverages the well-understood framework of fermionic excitation evolutions to build chemically meaningful ansätze. However, empirical data consistently shows that qubit-based adaptive algorithms, such as Qubit-ADAPT-VQE and QEB-ADAPT-VQE, generate significantly more hardware-friendly circuits with orders-of-magnitude reduction in CNOT counts and depths [9] [2]. The ongoing research and development, including the creation of novel operator pools like the Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool, continue to push the boundaries of resource efficiency [2]. Therefore, while Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE provides an essential conceptual bridge from classical quantum chemistry, its qubit-based descendants currently hold a practical advantage for the implementation of non-trivial molecular simulations on existing and near-future quantum devices.

The simulation of molecular quantum systems is a promising application for noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) computers. On these devices, the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for solving the electronic structure problem. A critical determinant of VQE's success is the ansatz—the parameterized quantum circuit that prepares the trial wavefunction. The adaptive derivative-assembled problem-tailored VQE (ADAPT-VQE) represents a significant advancement by iteratively constructing a problem-tailored ansatz, offering superior accuracy and efficiency compared to fixed-structure ansätze like unitary coupled-cluster singles and doubles (UCCSD) [2].

Two principal variants have been developed: the physically motivated fermionic-ADAPT-VQE and the hardware-efficient qubit-ADAPT-VQE. The latter utilizes rudimentary Pauli string exponentials as its ansatz elements, prioritizing operational simplicity and device compatibility over physical intuition [12] [2]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these protocols, analyzing their performance, resource requirements, and applicability to real-world problems such as drug discovery.

Methodological Comparison: Fermionic vs. Qubit-Based Protocols

Core Algorithmic Framework

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm iteratively grows an ansatz by appending parameterized unitary operators selected from a predefined pool. At each iteration, the algorithm chooses the operator with the largest energy gradient and optimizes its parameter [2]. The fundamental difference between the fermionic and qubit variants lies in the composition of this operator pool.

- Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE: Employs a pool of fermionic excitation operators of the form ( e^{\theta (\tau - \tau^\dagger)} ), where ( \tau ) is a fermionic excitation operator (e.g., single ( a^\daggeri aa ) or double ( a^\daggeri a^\daggerj aa ab ) excitations). These operators inherently preserve the physical symmetries of electronic wavefunctions but require deep circuits for implementation [12] [2].

- Qubit-ADAPT-VQE: Utilizes a pool of simple Pauli string exponentials (e.g., ( e^{i \theta P} ), where ( P ) is a tensor product of Pauli matrices). These "rudimentary" operators are more hardware-native, requiring shallower circuits, but they lack the physical motivation of fermionic operators and may require more parameters and iterations to converge [12].

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 1: Essential Components for ADAPT-VQE Simulations

| Component Name | Type/Class | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner Encoding [12] | Qubit Mapping | Transforms the fermionic electronic Hamiltonian into a qubit Hamiltonian expressed as a sum of Pauli strings. |

| Generalized Single & Double (GSD) Pool [2] | Operator Pool (Fermionic) | Provides the set of fermionic excitation evolution operators from which the fermionic-ADAPT-VQE selects. |

| Pauli String Exponential Pool [12] | Operator Pool (Qubit) | Provides the set of simple Pauli string evolutions from which the qubit-ADAPT-VQE selects. |

| Classical Optimizer (e.g., BFGS) [15] | Classical Software | Adjusts the parameters of the quantum ansatz to minimize the energy expectation value measured from the quantum computer. |

| Measurement Scheme (e.g., Grouping) [16] | Quantum Routine | Efficiently estimates the expectation values of the qubit Hamiltonian's Pauli terms, a major source of computational cost. |

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparisons

Resource Efficiency and Convergence

The primary advantage of qubit-ADAPT-VQE is its superior circuit efficiency. However, this can come at the cost of increased variational parameters and measurement overhead.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of ADAPT-VQE Variants for Representative Molecules

| Molecule (Qubits) | Protocol | Iterations to Chemical Accuracy | CNOT Count | Measurement Cost (Energy Evaluations) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH (12 qubits) | Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE [2] | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE [12] | Higher | Lower | Not Specified | |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* [2] | Lower | ~88% reduction | ~99.6% reduction | |

| H₆ (12 qubits) | Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE [2] | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE [12] | Higher | Lower | Not Specified | |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* [2] | Lower | ~88% reduction | ~99.6% reduction | |

| BeHâ‚‚ (14 qubits) | Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE [2] | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE [12] | Higher | Lower | Not Specified | |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* [2] | Lower | ~88% reduction | ~99.6% reduction |

The data shows that while qubit-ADAPT-VQE reduces CNOT counts, subsequent algorithms like QEB-ADAPT-VQE (which uses qubit excitation evolutions) and CEO-ADAPT-VQE (which uses coupled exchange operators) have been developed to bridge the gap, offering the circuit efficiency of qubit-based approaches without the same overhead in iterations and parameters [12] [2].

Comparative Analysis Against Static Ansätze

When compared to the widely used UCCSD ansatz, adaptive methods consistently demonstrate superior resource management.

Table 3: ADAPT-VQE vs. UCCSD Performance

| Metric | UCCSD-VQE | Qubit-ADAPT-VQE | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ansatz Flexibility | Fixed, general-purpose | Adaptive, problem-tailored | Adaptive, problem-tailored |

| Circuit Depth | High [2] | Lower [12] | Dramatically Lower [2] |

| Parameter Count | High, with redundancies [12] | Optimized, fewer redundancies | Highly Optimized [2] |

| Measurement Cost | Very High [2] | Lower | ~5 orders of magnitude lower [2] |

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE and its successors outperform UCCSD by constructing a system-specific ansatz, eliminating redundant operators and focusing on the most chemically relevant Hilbert space regions [12] [2].

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Energy Convergence

This protocol classically simulates ADAPT-VQE algorithms to compare their convergence toward the exact ground-state energy.

- System Preparation: Select a test molecule (e.g., LiH, H₆, BeH₂) and compute its electronic Hamiltonian in a minimal basis set (e.g., STO-3G) using a classical quantum chemistry package [12] [2].

- Qubit Encoding: Map the fermionic Hamiltonian to a qubit Hamiltonian using the Jordan-Wigner transformation [12].

- ADAPT-VQE Simulation: a. Initialize a reference state (e.g., Hartree-Fock) on the quantum simulator. b. For each iteration: i. For all operators in the pool (fermionic or Pauli strings), calculate the energy gradient ( \frac{\partial E}{\partial \thetai} ). ii. Select the operator with the largest gradient magnitude. iii. Append its unitary ( e^{\thetai A_i} ) to the ansatz circuit. iv. Re-optimize all parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) to minimize the total energy.

- Data Collection: Record the energy and quantum resource counts (CNOT gates, circuit depth) at each iteration. The simulation stops when chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa or 1 kcal/mol) is achieved [2].

Protocol 2: Simulating Bond Dissociation

This protocol evaluates the performance of algorithms for simulating strongly correlated systems, such as molecules at stretched bond geometries.

- Geometry Generation: Calculate the ground-state energy of a molecule (e.g., LiH) across a range of internuclear distances, including the equilibrium geometry and the dissociation limit [12] [2].

- Parallel Simulation: For each geometry, run the fermionic-ADAPT-VQE, qubit-ADAPT-VQE, and UCCSD protocols as described in Protocol 1.

- Accuracy Analysis: Plot the energy dissociation curves for each method and compute the absolute error relative to the exact full configuration interaction (FCI) energy. This tests the ability of each ansatz to capture strong electron correlation effects [12].

Workflow Visualization

The core differentiator between qubit and fermionic ADAPT-VQE is the content of the "Select Operator Pool" node. All subsequent steps in the iterative loop are algorithmically identical, though the choice of pool profoundly impacts the number of iterations required, the final circuit structure, and the measurement costs [12] [2].

Application in Drug Discovery

Quantum computing holds potential to revolutionize drug discovery by enabling more accurate molecular simulations [17] [15] [18]. VQE algorithms can model key quantum chemical properties that are computationally prohibitive for classical methods.

- Gibbs Free Energy Profiles: Calculating the energy barrier of chemical reactions, such as covalent bond cleavage in prodrug activation, is crucial for predicting drug efficacy. Hybrid quantum-classical pipelines have been developed to compute these profiles using VQE [15].

- Drug-Target Interactions: Understanding covalent inhibition, like the binding of Sotorasib to the KRAS G12C protein target in cancer, can be enhanced through quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) simulations where the QM region is handled by a VQE [15].

- Lead Compound Screening: Hybrid frameworks combining quantum graph neural networks (QGNNs) with VQE have been proposed to predict molecular properties and screen large compound libraries for drug candidates, such as serine neutralizers [19].

In these applications, the hardware efficiency of qubit-ADAPT-VQE is a significant advantage for feasibility on near-term devices, though the accuracy of the generated wavefunction remains paramount [15] [19].

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE represents a critical step toward practical quantum chemistry simulations on NISQ hardware. Its use of rudimentary Pauli string exponentials provides a hardware-efficient pathway, demonstrably reducing circuit depth and gate counts compared to fermionic-ADAPT-VQE and UCCSD [12] [2].

However, the field is rapidly evolving. Newer algorithms like QEB-ADAPT-VQE and CEO-ADAPT-VQE have emerged, building upon the qubit-ADAPT philosophy while seeking to mitigate its drawbacks, such as increased parameter counts [12] [2]. CEO-ADAPT-VQE, in particular, showcases the potential for drastic reductions in both circuit depth and measurement costs, which are critical bottlenecks [2].

Future research will focus on further refining operator pools, improving measurement strategies, and integrating these algorithms with classical quantum chemistry methods to tackle larger, biologically relevant systems. The continuous improvement of the ADAPT-VQE family underscores its viability as a leading candidate for achieving quantum utility in molecular simulation and drug discovery.

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a paradigm shift in quantum computational chemistry, moving beyond static, pre-defined ansätze to a dynamic, problem-tailored approach. Its core innovation lies in constructing quantum circuits iteratively by selecting and adding operators from a predefined "pool" based on their potential to lower the energy expectation value, typically assessed by a gradient criterion [20]. This methodology aims to generate more compact, less noisy circuits suitable for the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era.

The original formulation, Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE, utilized a pool of fermionic excitation operators, maintaining a direct connection to classical quantum chemistry methods but often resulting in deep circuits [12]. The subsequent development of Qubit-ADAPT-VQE marked a significant step by employing a pool of elementary Pauli string exponentials, which dramatically improved circuit efficiency at the cost of increased parameters and iterations [12] [16]. This evolution sets the stage for the hybrid approaches of QEB-ADAPT-VQE and CEO-ADAPT-VQE, which seek to balance physical motivation with hardware efficiency, offering a promising path toward practical quantum advantage on near-term devices.

QEB-ADAPT-VQE: Bridging Qubit Efficiency and Physical Intuition

Core Concept and Algorithm

The Qubit-Excitation-Based ADAPT-VQE (QEB-ADAPT-VQE) was introduced as a modification to the ADAPT-VQE protocol that utilizes "qubit excitation evolutions" as its operator pool [12]. Unlike fermionic excitation operators, which obey fermionic anti-commutation relations, qubit excitation operators are defined by their adherence to qubit commutation relations [12]. This fundamental shift in the building blocks of the ansatz allows the algorithm to construct quantum states with high accuracy while requiring asymptotically fewer quantum gates than its fermionic counterpart. The operators themselves are less rudimentary than the Pauli strings used in Qubit-ADAPT-VQE, striking a balance that enables more rapid and circuit-efficient ansatz construction.

Experimental Performance and Analysis

Classical numerical simulations for small molecules like LiH, H₆, and BeH₂ have demonstrated that QEB-ADAPT-VQE successfully bridges the performance gap between Fermionic- and Qubit-ADAPT-VQE.

The algorithm's performance can be summarized as follows:

- Convergence Speed: QEB-ADAPT-VQE requires fewer iterations to reach chemical accuracy compared to Qubit-ADAPT-VQE, as the higher complexity of its operators allows it to make more significant progress per iteration [12].

- Circuit Efficiency: It constructs ansätze with shallower circuits than Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE, making it more suitable for NISQ hardware. It was noted as a significant improvement in circuit efficiency over previous scalable VQE protocols [12].

- Accuracy: Despite lacking some physical features of fermionic excitations, the ansätze built with qubit excitation evolutions can approximate electronic wavefunctions with accuracy nearly on par with those built from fermionic excitations [12].

CEO-ADAPT-VQE: A Novel Pool for Maximal Resource Reduction

Core Concept and Algorithm

The Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool represents a further advancement in the design of efficient operator pools for ADAPT-VQE. The CEO-ADAPT-VQE algorithm integrates this novel pool with other recent improvements in measurement strategies and hardware-efficient ansatz construction [2]. The defining feature of the CEO pool is its specific design, which aims to maximize the reduction of quantum computational resources—including two-qubit gate counts, circuit depth, and the number of measurements required—without sacrificing the accuracy of the final result.

Experimental Performance and Analysis

Numerical simulations for molecules such as LiH, H₆, and BeH₂ (represented by 12 to 14 qubits) have shown that CEO-ADAPT-VQE achieves dramatic resource reductions compared to earlier versions of the algorithm, representing the state of the art in adaptive VQE methods [2].

The table below summarizes the profound resource reductions achieved by the state-of-the-art CEO-ADAPT-VQE* variant compared to the early fermionic (GSD-ADAPT-VQE) algorithm:

| Molecule | Qubit Count | Reduction in CNOT Count | Reduction in CNOT Depth | Reduction in Measurement Costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH | 12 | Up to 88% | Up to 96% | Up to 99.6% |

| H₆ | 12 | Up to 88% | Up to 96% | Up to 99.6% |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | Up to 88% | Up to 96% | Up to 99.6% |

Table 1: Resource reduction of CEO-ADAPT-VQE compared to early ADAPT-VQE versions [2].*

Furthermore, CEO-ADAPT-VQE was found to outperform the standard Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) ansatz—a widely used static ansatz in VQE—across all relevant metrics. It also offers a five-order-of-magnitude decrease in measurement costs compared to other static ansätze with similar CNOT counts [2].

Direct Comparison: QEB-ADAPT-VQE vs. CEO-ADAPT-VQE

The following table provides a consolidated comparison of the two hybrid approaches against their predecessors, based on the data from the search results.

| Algorithm | Operator Pool Type | Key Innovation | Convergence Speed | Circuit Efficiency | Primary Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fermionic-ADAPT | Fermionic Excitations | Original physically-motivated pool | Baseline | Deeper circuits | Direct chemical intuition |

| Qubit-ADAPT | Pauli Strings | Elementary, hardware-efficient operations | Slower | High | Minimal gate complexity |

| QEB-ADAPT | Qubit Excitations | Obeys qubit commutation relations | Faster than Qubit-ADAPT | High | Balance of speed and efficiency |

| CEO-ADAPT | Coupled Exchange Operators | Optimized for maximal resource reduction | Not Explicitly Stated | Very High | Lowest CNOT count & measurement overhead |

Table 2: Comparative analysis of ADAPT-VQE variants. Convergence speed and circuit efficiency are rated relative to other algorithms in the family [2] [12] [16].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard ADAPT-VQE Workflow

The core experimental protocol for all ADAPT-VQE variants follows a recursive, iterative loop. The diagram below illustrates this general workflow, which is shared by QEB- and CEO-ADAPT-VQE, with the key difference lying in the composition of the operator pool.

Key Methodological Variations

The critical methodological differences between the algorithms are rooted in their operator pools:

- QEB-ADAPT-VQE Protocol: The operator pool consists of unitary evolutions of qubit excitation operators. The ansatz is grown by iteratively appending the operator from this pool that shows the largest gradient magnitude. A modified growing strategy is sometimes employed, which trades a constant-factor increase in measurements for more efficient ansatz construction [12].

- CEO-ADAPT-VQE Protocol: The algorithm uses the novel Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool. This is combined with "improved subroutines," which refer to advanced techniques for reducing measurement overhead, such as reusing Pauli measurements and employing variance-based shot allocation across both the Hamiltonian and the gradient measurements [2] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below details key components and their functions in a typical ADAPT-VQE simulation study, as inferred from the cited research.

| Research Reagent / Component | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Molecular Hamiltonian | Defines the quantum chemistry problem; the target operator whose ground state is being sought [12]. |

| Operator Pool | A pre-defined set of operators (e.g., Fermionic, Pauli, Qubit Excitation, CEO) from which the ansatz is built [2] [12]. |

| Reference State | The initial quantum state, often the Hartree-Fock state, from which the adaptive ansatz construction begins [12]. |

| Jordan-Wigner Transform | A common encoding method that maps fermionic operators from the Hamiltonian to Pauli strings operable on a quantum computer [12]. |

| Gradient Criterion | The metric (often the energy gradient ∂E/∂θᵢ) used to rank and select the next operator from the pool [20]. |

| Classical Optimizer | The algorithm (e.g., gradient-based or gradient-free) that variationally updates all parameters in the ansatz circuit to minimize energy [13]. |

| Variance-Based Shot Allocation | A technique to reduce measurement overhead by strategically allocating more "shots" to noisier observables [5]. |

| Sulfocostunolide A | Sulfocostunolide A, CAS:1016983-51-9, MF:C15H20O5S, MW:312.4 g/mol |

| Pterisolic acid C | Pterisolic acid C, CAS:1401419-87-1, MF:C20H26O4, MW:330.4 g/mol |

The emergence of hybrid approaches like QEB-ADAPT-VQE and CEO-ADAPT-VQE marks a significant maturation of adaptive variational quantum algorithms. While QEB-ADAPT-VQE successfully established a middle ground between the physical intuition of fermionic operators and the hardware efficiency of Pauli strings, CEO-ADAPT-VQE represents a leap forward by explicitly designing an operator pool for minimal quantum resource consumption. The experimental data demonstrates a clear trend: through strategic innovation in the operator pool, it is possible to achieve orders-of-magnitude reduction in critical resources like CNOT gate counts and measurement costs. This progress is vital for making quantum simulations of molecules such as LiH and BeHâ‚‚ feasible on current hardware. As the field advances, the integration of these efficient algorithms with other strategies like effective Hamiltonians and advanced error mitigation will be crucial for tackling more complex chemical systems and moving closer to demonstrating a practical quantum advantage.

Algorithmic Mechanics and Real-World Application in Drug Discovery

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithm for molecular simulations on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. A critical component determining its performance is the operator pool—the set of operators used to build the quantum circuit ansatz. This guide provides an objective comparison of the three primary operator pool types: Fermionic, Pauli Strings (Qubit), and Qubit Exitations (QEB), within the adaptive derivative-assembled pseudo-Trotter (ADAPT-VQE) framework. Understanding their trade-offs is essential for researchers aiming to simulate molecular systems, such as in drug development, where predicting chemical properties accurately is paramount.

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Fermionic Pools: Constructed from fermionic excitation operators (e.g., single and double excitations from UCCSD), these pools generate ansätze that respect the physical symmetries of electronic wavefunctions, such as fermionic antisymmetry [12]. This makes them interpretable and easy to optimize, though they can lead to computationally expensive circuits.

Pauli String (Qubit) Pools: These are built by decomposing fermionic excitations into their constituent Pauli strings (tensor products of Pauli operators) [21]. This results in very rudimentary, hardware-efficient operations, significantly reducing circuit depth at the cost of losing the physical fermionic structure and potentially increasing the number of variational parameters required [12].

Qubit Excitation (QEB) Pools: A middle-ground approach, QEB pools use "qubit excitation evolutions" that obey qubit, rather than fermionic, commutation relations [12]. These operators are less physically intuitive than fermionic ones but are more complex than simple Pauli strings. They aim to achieve accuracy close to fermionic pools while maintaining hardware efficiency superior to both other approaches [12] [22].

Table 1: Core Theoretical Characteristics of Operator Pools

| Feature | Fermionic Pool | Pauli String (Qubit) Pool | Qubit Excitation (QEB) Pool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Fermionic commutation relations [12] | Decomposed Pauli strings [21] | Qubit commutation relations [12] |

| Physical Intuition | High (respects wavefunction symmetries) [12] | Low (lacks fermionic structure) [12] | Moderate (modified fermionic operations) [12] |

| Ansatz Element Complexity | High | Low (rudimentary operations) [12] | Intermediate |

| Typical Pool Size Scaling | ( \mathcal{O}(N^2 n^2) ) [21] | Larger than fermionic pool [21] | Not Explicitly Stated |

Methodological Approaches and Workflows

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm iteratively constructs a problem-tailored ansatz. It starts from a reference state (e.g., Hartree-Fock) and, in each iteration, selects operators from a predefined pool to append to the circuit based on a gradient criterion [12] [13].

Figure 1: The generalized workflow for the ADAPT-VQE algorithm, applicable to any operator pool.

To mitigate the significant measurement overhead of computing gradients for the entire pool each iteration, the batched ADAPT-VQE strategy has been proposed. This variant adds multiple operators with the largest gradients simultaneously, reducing the number of required gradient measurement cycles [21].

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data

Classical numerical simulations for small molecules like LiH, H(6), and BeH(2) provide key performance metrics for comparing the pools.

Table 2: Empirical Performance Comparison Across Molecules

| Performance Metric | Fermionic-ADAPT | Pauli String (Qubit)-ADAPT | Qubit Excitation (QEB)-ADAPT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit Efficiency (CNOT Count) | Higher | Lower than Fermionic [12] | Best (Outperforms Qubit-ADAPT) [12] |

| Convergence Speed (Number of Iterations/Parameters) | Moderate | Slower (requires more iterations/parameters) [12] | Faster than Qubit-ADAPT [12] |

| Accuracy Attainment | Chemically accurate [12] | Chemically accurate [12] | Chemically accurate [12] |

| Measurement Overhead | High (large pool, ( \mathcal{O}(N^2 n^2) )) [21] | Very High (larger pool size) [21] | Potentially Lower (faster convergence) |

CNOT Gate Efficiency

The QEB-ADAPT-VQE protocol demonstrates a superior balance of circuit efficiency and convergence speed. For instance, when preparing molecular ground states, the CNOT count for QEB-ADAPT can be reduced by up to 74% compared to other methods on fully-connected quantum computer models [22]. This efficiency is critical on NISQ devices where two-qubit gate errors are a dominant source of noise.

Convergence and Parameter Efficiency

The qubit-ADAPT-VQE, while generating shallow circuits, often requires more variational parameters and iterations to converge to a given accuracy compared to the QEB approach [12]. The QEB pool's operators have higher complexity than Pauli strings, allowing them to recover correlation energy more rapidly per iteration, leading to faster overall convergence [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Methods for ADAPT-VQE Experiments

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Relevance to Pool Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner Transformation | Encodes fermionic operators into qubit (Pauli) operators [12]. | Standard first step for Fermionic and QEB pools; defines qubit Hamiltonian. |

| Qubit Tapering | Exploits symmetries to reduce the number of active qubits [21]. | Reduces computational cost for all pools; enables simulation of larger molecules. |

| Classical Optimizer (e.g., COBYLA) | Variationally optimizes parameters of the quantum circuit [13] [1]. | Crucial for convergence; gradient-based optimizers are often more economical [13]. |

| Active Space Approximation | Restricts simulation to a subset of chemically relevant molecular orbitals [1]. | Makes problem tractable on current hardware; necessary for benchmarking all methods. |

| Batched Operator Selection | Adds multiple high-gradient operators to the ansatz per iteration [21]. | Reduces measurement overhead, a significant bottleneck for all adaptive protocols. |

| Sulfocostunolide B | Sulfocostunolide B, CAS:1059671-65-6, MF:C15H20O5S, MW:312.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ilicol | Ilicol, CAS:72715-02-7, MF:C15H26O2, MW:238.371 | Chemical Reagent |

Hardware Considerations and Advanced Optimizations

The performance gaps between pools are accentuated on real quantum hardware with limited qubit connectivity. The "Treespilation" technique optimizes the fermion-to-qubit mapping by tailoring it to both the quantum device's connectivity graph and the specific state being prepared. This advanced compilation method can reduce CNOT counts by up to 74% for full connectivity and yield even greater relative reductions on devices with limited connectivity like IBM Eagle and Google Sycamore [22]. This demonstrates that the choice of mapping is as crucial as the choice of operator pool for practical implementations.

This comparative analysis reveals a clear trade-off between physical intuition, circuit efficiency, and convergence speed. The Fermionic pool offers high physical intuition but lower circuit efficiency. The Pauli String (Qubit) pool provides the shallowest circuits but at the cost of slower convergence and more parameters. The Qubit Excitation (QEB) pool strikes a favorable balance, delivering high circuit efficiency and faster convergence without sacrificing final accuracy [12] [22].

For researchers targeting industrially relevant molecules (e.g., in drug development or catalysis studies like carbon monoxide oxidation [21]), the QEB-ADAPT-VQE protocol, possibly combined with batched operator selection and advanced compilation like Treespilation, currently presents the most promising path forward on NISQ hardware. Future work should focus on further reducing measurement overhead and developing even more compact, chemically-aware operator pools.

The quest for simulating quantum systems on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices has catalyzed the development of adaptive variational quantum eigensolvers (ADAPT-VQE). These algorithms dynamically construct problem-tailored ansätze through an iterative process of operator selection and parameter optimization, offering a promising path toward quantum advantage in quantum chemistry [12] [2]. Unlike fixed-structure ansätze such as unitary coupled cluster singles and doubles (UCCSD), which may contain redundant operators, ADAPT-VQE grows an ansatz specific to the molecular Hamiltonian of interest [23]. This guide focuses on the ansatz growth dynamics of two principal variants: the fermionic-ADAPT-VQE (F-ADAPT) and the qubit-ADAPT-VQE (Q-ADAPT), objectively comparing their performance, resource requirements, and implementation protocols.

Algorithmic Fundamentals and Comparative Structure

Core Iterative Mechanism

Both F-ADAPT and Q-ADAPT share a fundamental iterative structure for ansatz construction [12] [2] [23]. The algorithm begins with a simple reference state, typically the Hartree-Fock state. At each iteration ( m ), the algorithm:

- Evaluates Gradients: For each operator ( Ai ) in a predefined pool, compute the energy gradient (with respect to its parameter) given the current ansatz state ( |\Psi^{(m-1)}\rangle ): ( gi = \frac{d}{d\theta} \langle \Psi^{(m-1)} | e^{\theta Ai} H e^{-\theta Ai} | \Psi^{(m-1)} \rangle \big|_{\theta=0} ).

- Selects Optimal Operator: Identifies the operator ( A^* ) with the largest gradient magnitude: ( A^* = \arg \max{Ai} |g_i| ).

- Appends and Optimizes: Appends the unitary ( e^{\theta A^*} ) to the ansatz and performs a global optimization of all parameters.

This gradient-based selection ensures that each added operator provides the greatest potential energy descent, leading to an efficient, system-tailored ansatz [23].

Operator Pool Divergence

The critical distinction between F-ADAPT and Q-ADAPT lies in the composition of their operator pools, which directly influences ansatz growth dynamics and hardware efficiency [12].

- Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE: Utilizes a pool of fermionic excitation operators of the form ( \tau\mu - \tau\mu^\dagger ), where ( \tau\mu ) is a fermionic excitation operator (e.g., singles ( aa^\dagger ai ) and doubles ( aa^\dagger ab^\dagger ai aj )). These operators preserve physical symmetries like particle number and spin but generate quantum circuits whose depth scales at least as ( O(\log2 N{\text{MO}}) ) with the number of molecular orbitals ( N{\text{MO}} ) [12].

- Qubit-ADAPT-VQE: Employs a pool of Pauli string exponentials, which are more rudimentary and hardware-native. While more circuit-efficient, this pool's operators are less physically motivated, often requiring more iterations and parameters to achieve a comparable accuracy [12].

A intermediate approach, the Qubit-Excitation-Based ADAPT-VQE (QEB-ADAPT), uses operators that obey qubit commutation relations. These offer a favorable balance, requiring asymptotically fewer gates than fermionic excitations while being more complex than simple Pauli strings, thus accelerating ansatz convergence [12].

Performance and Resource Comparison

The following tables consolidate quantitative performance data from classical numerical simulations for small molecules such as LiH, H(6), and BeH(2) [12] [2].

Table 1: Performance Comparison for Achieving Chemical Accuracy

| Metric | Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE | Qubit-ADAPT-VQE | QEB-ADAPT-VQE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ansatz Circuit Depth | Higher (Baseline) | Significantly Lower | Lower than Qubit-ADAPT [12] |

| Convergence Speed (Iterations) | Lower (Baseline) | Higher [12] | Intermediate (Outperforms Qubit-ADAPT) [12] |

| Number of Parameters | Fewer (Baseline) | More [12] | Intermediate |

| CNOT Gate Reduction | Baseline | Up to 88% reduction reported in enhanced variants [2] | -- |

| Measurement Cost Reduction | Baseline | -- | Up to 99.6% in enhanced variants [2] |

Table 2: Computational Resource Analysis (Representative 12-14 Qubit Systems)

| Resource Type | Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE | State-of-the-Art ADAPT-VQE | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNOT Count | Baseline | 12-27% of baseline [2] | Up to 88% |

| CNOT Depth | Baseline | 4-8% of baseline [2] | Up to 96% |

| Measurement Costs | Baseline | 0.4-2% of baseline [2] | Up to 99.6% |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Molecular Systems

Comparative studies typically evaluate algorithm performance across a set of small molecules, including LiH, H(6), and BeH(2), often examining potential energy surfaces across bond dissociation curves [12] [2]. These systems are chosen to represent varying degrees of electron correlation. The primary metric is the number of ADAPT iterations and the final CNOT gate count required to achieve chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa or 1 kcal/mol error) relative to the full configuration interaction (FCI) energy.

Key Experimental Components

- Hamiltonian Preparation: The electronic Hamiltonian is derived in second quantization under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation and mapped to qubit operators using encoding techniques like Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev [12] [5].

- Active Space Approximation: To reduce qubit requirements, the molecular Hamiltonian is often projected into an active space of chemically important orbitals, integrating out core and high-energy virtual orbitals [1].

- Gradient Evaluation: The critical and resource-intensive step. For a pool operator ( Ai ), the gradient is proportional to the expectation value of the commutator ( \langle \Psi | [H, Ai] | \Psi \rangle ). This requires measuring a set of Pauli observables on the quantum computer [5] [23].

- Parameter Optimization: After appending a new operator, all parameters of the ansatz are optimized to minimize the energy. This can be done using classical optimizers (COBYLA, BFGS) or quantum-aware methods like ExcitationSolve, which is specifically designed for efficient optimization of excitation operators [24].

Workflow Visualization and Algorithmic Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the core iterative workflow of the ADAPT-VQE algorithm and the divergent paths taken by its fermionic and qubit variants.

ADAPT-VQE Workflow and Pool Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Methods

| Tool / Method | Function / Purpose | Relevance to Ansatz Dynamics |

|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner Transform | Maps fermionic operators to qubit (Pauli) operators [12]. | Enables implementation of fermionic excitations on qubit hardware; impacts circuit connectivity and length. |

| Active Space Selection | Reduces qubit count by restricting to chemically relevant orbitals [1]. | Defines the size of the problem Hamiltonian and limits the operator pool, crucial for NISQ implementations. |

| Commutator Grouping | Groups mutually commuting Pauli terms for simultaneous measurement [5]. | Dramatically reduces quantum shot requirements for gradient evaluation during operator selection. |

| ExcitationSolve Optimizer | Quantum-aware, gradient-free optimizer for excitation operators [24]. | Efficiently optimizes parameters in physically-motivated ansätze, reducing required energy evaluations. |

| Double Unitary CC (DUCC) | Creates effective Hamiltonians via downfolding [16]. | Incorporates dynamical correlation into smaller active spaces, improving accuracy without increasing qubit count. |

| Deoxyshikonofuran | Deoxyshikonofuran, MF:C16H18O3, MW:258.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Erythrocentauric acid | Erythrocentauric acid, MF:C10H8O4, MW:192.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The ansatz growth dynamics in ADAPT-VQE protocols present a fundamental trade-off between physical motivation and hardware efficiency. Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE generates more physically intuitive and compact ansätze in terms of the number of operators, respecting molecular symmetries. In contrast, Qubit-ADAPT-VQE produces shallower quantum circuits, a critical advantage on noisy hardware, albeit at the cost of increased variational parameters and slower convergence [12]. Intermediate approaches like QEB-ADAPT and the more recent CEO-ADAPT [2] suggest that the optimal path lies in operator pools that balance physical structure with gate efficiency. The choice between these variants ultimately depends on the specific constraints of the target hardware and the molecular system, with ongoing research continuously improving the resource efficiency of both pathways.

The Adaptive Derivative-assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a class of iterative, problem-tailored algorithms for solving electronic structure problems on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. Unlike fixed-ansatz approaches, ADAPT-VQE protocols dynamically construct a circuit ansatz by iteratively appending operators selected from a predefined pool based on a specific criterion, typically the energy gradient. This methodology aims to create more compact and hardware-efficient quantum circuits than general-purpose ansätze. The core differentiator between various ADAPT-VQE flavors lies in the type of operators used in the ansatz pool—a choice that fundamentally impacts the resulting circuit's gate count, depth, and hardware performance [12] [11].

The fermionic-ADAPT-VQE utilizes a pool of spin-complement single and double-fermionic-excitation evolutions. These operators are motivated by classical quantum chemistry and respect the physical symmetries of electronic wavefunctions. In contrast, the qubit-ADAPT-VQE employs a pool of more rudimentary and variationally flexible Pauli string exponentials, which can be implemented with simpler quantum circuits but may lack the physical intuition of fermionic operators [12]. A more recent variant, the Qubit-Excitation-Based ADAPT-VQE (QEB-ADAPT-VQE), uses "qubit excitation evolutions" which obey qubit commutation relations rather than fermionic anti-commutation relations. This approach aims to balance the physical motivation of fermionic operators with the hardware efficiency of Pauli-based operators [12].

Comparative Analysis of Circuit Efficiency

The choice of operator pool in ADAPT-VQE protocols directly determines the quantum circuit's complexity, which is crucial for implementation on depth-limited NISQ devices. The following analysis compares the gate count and circuit depth characteristics of the fermionic, qubit, and qubit-excitation-based ADAPT-VQE variants.

Table 1: Circuit Efficiency Comparison of ADAPT-VQE Protocols

| Protocol | Ansatz Element Type | Circuit Implementation Characteristics | Asymptotic Gate Requirements | Performance Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE [12] | Fermionic excitation evolutions | Respects physical symmetries; higher gate count per operator | Higher | Accurate but less circuit-efficient; contains redundant terms |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE [12] | Pauli string exponentials | Rudimentary, hardware-efficient gates; shallower circuits | Lower | Most circuit-efficient scalable VQE prior to QEB-ADAPT; requires more parameters/iterations |

| Qubit-Excitation-Based (QEB-ADAPT-VQE) [12] | Qubit excitation evolutions | Obeys qubit commutation relations; acts on fixed qubit numbers | Fewer gates than fermionic | Outperforms Qubit-ADAPT in convergence speed and circuit efficiency |

The key advantage of the QEB-ADAPT-VQE protocol is its ability to construct accurate ansätze while requiring asymptotically fewer gates than the fermionic approach. Although qubit excitation evolutions lack some physical features of fermionic excitation evolutions, they can approximate electronic wavefunctions with similar accuracy while being more amenable to implementation with shallow circuits [12]. Compared to the qubit-ADAPT-VQE, the QEB-ADAPT-VQE demonstrates superior convergence speed, meaning it requires fewer iterations and variational parameters to achieve a given accuracy level for molecular simulations [12].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Methodologies for Benchmarking ADAPT-VQE Variants

Performance comparisons between ADAPT-VQE protocols are typically conducted through classical numerical simulations of small molecules, which provide controlled benchmarks for evaluating circuit efficiency and convergence properties. Standard experimental methodology involves:

- Molecular Selection: Small molecules like LiH, H₆, and BeH₂ are commonly used for benchmarking [12]. These systems are computationally tractable for classical simulation while exhibiting relevant electronic correlation effects.

- Hamiltonian Encoding: The electronic Hamiltonian from Eq. (1) is mapped to quantum gate operators using encoding methods such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev [12]. The Jordan-Wigner transformation is often assumed for simplicity.

- Ansatz Construction: Each ADAPT-VQE variant grows its ansatz iteratively. At each iteration N, the algorithm:

- Computes the energy gradient ∂E(N)/∂θᵢ for all operators in its pool [11].

- Selects the operator with the largest gradient magnitude.

- Appends its parametrized exponential to the circuit: |ψ(N)⟩ = e^{θᵢÂᵢ}|ψ(N-1)⟩ [11].

- Re-optimizes all parameters {θᵢ} classically, recycling previous parameters to avoid local minima [11].

- Convergence Criterion: The iterative process continues until the energy gradient norm falls below a predefined threshold (e.g., 10â»Â³ Hartree) [12].

- Metric Tracking: Researchers track the number of iterations, number of quantum gates (specifically two-qubit gates like CNOTs which contribute most to noise), circuit depth, and energy error relative to the full configuration interaction (FCI) benchmark.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Numerical simulations across different molecular systems reveal distinct performance patterns for each ADAPT-VQE protocol. The data below summarizes key findings from these comparative studies.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data from Molecular Simulations

| Molecule | Protocol | Key Metric | Result | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecules (LiH, H₆, BeH₂) [12] | QEB-ADAPT-VQE | Convergence Speed & Circuit Efficiency | Outperforms Qubit-ADAPT-VQE | Achieves chemical accuracy with shallower circuits and fewer iterations |

| Small Molecules [12] | QEB-ADAPT-VQE | Gate Count vs Fermionic-ADAPT | Asymptotically fewer gates than Fermionic-ADAPT | More feasible on NISQ devices with limited coherence times |

| Hâ‚„ Models [11] | Improved ADAPT-VQE | Circuit Depth | Shallower circuits via optimized initial states and growth guidance | Reduced quantum depth and measurement requirements |

| General Performance [12] | Fermionic-ADAPT-VQE | Parameter Efficiency vs UCCSD | Several times fewer parameters than UCCSD | Redundant excitation terms are eliminated |

The convergence speed advantage of QEB-ADAPT-VQE over qubit-ADAPT-VQE is particularly significant. While the qubit-ADAPT-VQE constructs shallower ansatz circuits than the fermionic-ADAPT-VQE, it requires additional variational parameters and iterations to construct an ansatz for a given accuracy [12]. The QEB-ADAPT-VQE mitigates this trade-off by utilizing operators with higher complexity than Pauli strings but greater hardware efficiency than fermionic operators.

Figure 1: ADAPT-VQE Iterative Workflow. The algorithm builds a problem-tailored ansatz by sequentially adding operators based on an energy gradient criterion.

Hardware-Specific Considerations

Impact on NISQ Device Implementation

The practical implementation of ADAPT-VQE protocols on current quantum hardware necessitates careful consideration of device-specific constraints, including qubit connectivity, gate fidelity, and coherence times.

- Qubit Connectivity: The QEB-ADAPT-VQE and qubit-ADAPT-VQE often demonstrate advantages over fermionic-ADAPT-VQE on devices with limited connectivity. Fermionic excitation evolutions, when transformed into qubit gates via Jordan-Wigner encoding, may require long chains of gates that span many qubits, leading to increased SWAP overhead on devices with non-fully-connected architectures [12].

- Gate Decomposition: The fundamental building blocks of each protocol significantly impact circuit depth. Qubit excitation evolutions and Pauli string exponentials generally require fewer native gates to implement compared to fermionic excitation evolutions, which may need extensive decomposition into one- and two-qubit gates [12].

- Error Propagation: Deeper circuits compound errors from noisy gates and decoherence. Protocols that achieve faster convergence (like QEB-ADAPT-VQE) inherently produce shallower circuits for a given accuracy threshold, thereby reducing the accumulation of errors during computation [12].

- Measurement Optimization: Recent improvements to ADAPT-VQE focus on guiding ansatz growth to produce more compact wavefunctions, which directly translates to reduced measurement requirements—a critical bottleneck in VQE simulations [11].

Enhancing Hardware Performance

Several strategies have been developed to improve the hardware performance of ADAPT-VQE protocols:

- Initial State Preparation: Using natural orbitals from unrestricted Hartree-Fock (UHF) calculations as the initial state can enhance the overlap with the true ground state, particularly for strongly correlated systems. This improvement comes at mean-field computational cost and can lead to more rapid convergence and shallower circuits [11].