Qubit-Wise Commutativity: A Practical Guide to Quantum Measurement Optimization for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of qubit-wise commutativity (QWC) and its critical role in optimizing quantum measurements for variational algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE).

Qubit-Wise Commutativity: A Practical Guide to Quantum Measurement Optimization for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of qubit-wise commutativity (QWC) and its critical role in optimizing quantum measurements for variational algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE). Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we cover the foundational theory of QWC versus full commutativity, demonstrate practical implementation using modern quantum libraries, address common troubleshooting scenarios, and present a comparative analysis of grouping strategies. By reducing the number of required quantum measurements by up to 90%, these techniques offer a practical path to overcoming a major bottleneck in applying quantum computing to molecular simulation and drug discovery on near-term hardware.

Understanding the Quantum Measurement Problem and Qubit-Wise Commutativity Fundamentals

The Quantum Measurement Bottleneck in NISQ Algorithms

The Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era is defined by quantum processors containing from approximately 50 to 1000 qubits that operate without the benefit of full quantum error correction [1] [2]. These devices are characterized by high error rates, limited coherence times, and gate fidelities that restrict executable circuit depths to roughly 1,000 operations before noise overwhelms the computational signal [2]. Within this constrained environment, Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) have emerged as a leading algorithmic paradigm, particularly for quantum chemistry and drug discovery applications [1] [3]. However, the efficient estimation of molecular observables—a computational primitive fundamental to these applications—presents a critical bottleneck [4]. The core of this bottleneck lies in the measurement overhead required for Hamiltonian expectation value estimation, which scales as O(Nâ´) to O(Nâ¸) for problems of interest, potentially requiring millions of state preparations to achieve chemical accuracy [4]. This article examines the quantum measurement bottleneck, the recent advances in measurement grouping strategies—with a specific focus on qubit-wise commutativity—and the experimental methodologies enabling progress toward practical quantum advantage in computational chemistry and drug development.

The Fundamental Challenge of Observable Estimation

Mathematical Foundation of the Measurement Problem

In quantum chemistry simulations on NISQ devices, the target observable is typically a molecular Hamiltonian H, which must be decomposed into a linear combination of N-qubit Pauli operators (tensor products of Pauli matrices X, Y, Z, and the identity I) [4]:

[H = \sum{i=1}^{M} ci Pi, \quad \text{where } Pi = \bigotimes{j=1}^{N} \sigma{ij}, \ \sigma{ij} \in {X, Y, Z, I}, \ ci \in \mathbb{R}]

The expectation value (\langle \psi | H | \psi \rangle) for a quantum state (|\psi\rangle) is approximated through quantum measurement. For each Pauli term (Pi), the quantum computer prepares the state and measures it to construct an estimator (\hat{Pi}) [4]. The fundamental challenge arises because each Pauli term may require a different measurement basis, and the number of terms M grows rapidly with system size. Direct sequential measurement of each term would be prohibitively expensive in terms of quantum resources [4].

Impact on Algorithmic Performance

The measurement bottleneck directly impacts the feasibility and efficiency of NISQ algorithms for drug discovery. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), widely used for molecular ground state energy calculations, relies on repeated estimation of the Hamiltonian expectation value during its optimization loop [1] [3]. The excessive measurement overhead can render chemically accurate calculations impractical even for small molecules, limiting the scale of quantum chemistry problems addressable on current hardware [4]. This constraint is particularly acute for pharmaceutical applications where studying complex molecular interactions requires precise energy calculations beyond the capabilities of classical computers.

Measurement Grouping Strategies: From Full Commutation to Qubit-Wise Commutativity

Foundations of Simultaneous Measurement

To reduce measurement overhead, simultaneous measurement strategies group multiple Pauli operators that can be measured using the same quantum circuit and measurement basis [4]. Two primary grouping schemes have been developed:

Fully Commuting (FC) Groups: Operators that commute according to the standard commutation relation ([Pi, Pj] = PiPj - PjPi = 0) can be simultaneously diagonalized and measured [4]. While FC grouping provides the lowest estimator variance, it requires entangling operations for diagonalization that introduce significant noise and potential bias on NISQ devices [4].

Qubit-Wise Commuting (QWC) Groups: A stricter commutativity relation where two Pauli operators commute if their corresponding single-qubit Pauli operators commute at every qubit position [4]. While QWC groups exhibit higher variance than FC groups, they can be measured with single-qubit basis rotations without entangling gates, making them more noise-resilient on NISQ devices [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Pauli Grouping Strategies for Molecular Hamiltonian Measurement

| Grouping Strategy | Commutation Relation | Circuit Requirements | Noise Resilience | Estimator Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Commutation (FC) | ([Pi, Pj] = 0) | Requires entangling gates for diagonalization | Low (high bias from noise) | Lowest |

| Qubit-Wise Commutation (QWC) | Commutes at every qubit position | Single-qubit rotations only | High (minimal bias) | Higher than FC |

| GALIC (Hybrid) | Context-aware interpolation | Selective entangling gates | Adaptive to device noise | 20% lower than QWC |

Qubit-Wise Commutativity: Formal Definition and Significance

Qubit-wise commutativity represents a hardware-efficient alternative to full commutativity that has been widely adopted in quantum software packages [4]. Formally, two N-qubit Pauli operators (P = \bigotimes{k=1}^{N} \sigmak) and (Q = \bigotimes{k=1}^{N} \tauk) are qubit-wise commuting if for every qubit position k, the single-qubit Pauli operators (\sigmak) and (\tauk) commute: (\sigmak \tauk = \tauk \sigmak) for all k = 1, ..., N [4].

This relation is strictly stronger than full commutativity—all QWC operators are fully commuting, but not all fully commuting operators are QWC. The practical significance for NISQ algorithms lies in the measurement circuit simplicity: QWC groups can be diagonalized using only single-qubit gates rather than entangling operations, significantly reducing circuit depth and noise susceptibility [4]. This makes QWC particularly valuable for pharmaceutical applications where measurement reliability may outweigh the additional state preparation cost.

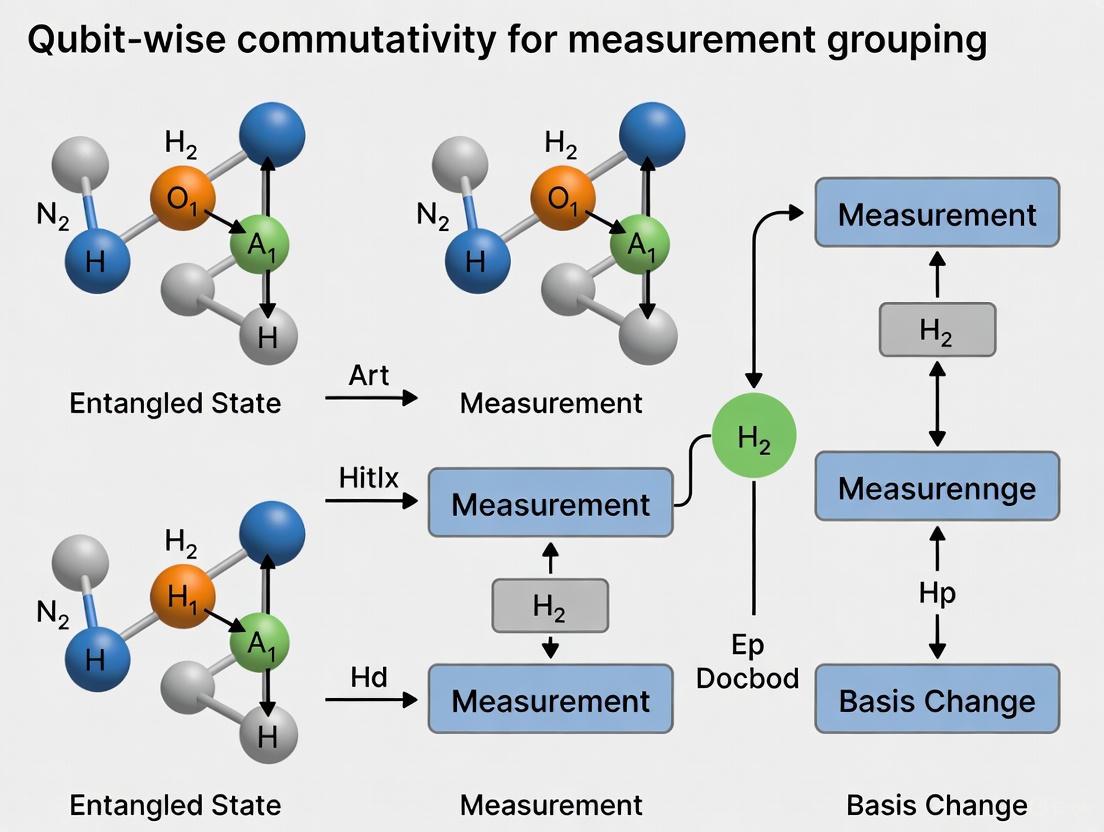

Figure 1: Logical relationships between Pauli measurement grouping strategies, highlighting the trade-offs between different approaches for NISQ algorithms.

Advanced Hybrid Frameworks: Interpolating Between FC and QWC

The GALIC Framework: Generalized Backend-Aware Pauli Commutation

The Generalized backend-Aware pauLI Commutation (GALIC) framework represents a significant advancement by providing a systematic approach to interpolate between FC and QWC grouping strategies [4] [5]. GALIC introduces a context-aware hybrid commutativity relation that dynamically adjusts grouping strategy based on device characteristics including noise levels, connectivity, and gate fidelities [4]. This approach recognizes that the binary choice between FC and QWC is suboptimal—instead, selective introduction of entangling gates in a noise-aware manner can achieve better variance characteristics than QWC while maintaining higher fidelity than FC [4].

Performance Advantages of Hybrid Grouping

Experimental results demonstrate that GALIC achieves a 20% average reduction in estimator variance compared to QWC while maintaining chemical accuracy (error < 1 kcal/mol) [4] [5]. Furthermore, hardware experiments on IBM quantum processors show 1.2× lower GALIC estimator variance compared to QWC, validating numerical simulations [4]. This performance improvement is achieved without introducing excessive bias from noisy entangling operations, striking an optimal balance for NISQ devices.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Grouping Strategies on Molecular Hamiltonians

| Molecule (Qubits) | Grouping Strategy | Estimator Variance | Measurement Overhead | Energy Error (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ (4) | QWC | 1.00 (baseline) | 1.00 (baseline) | 0.45 |

| FC | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.52 | |

| GALIC | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.47 | |

| LiH (12) | QWC | 1.00 (baseline) | 1.00 (baseline) | 0.78 |

| FC | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.85 | |

| GALIC | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.74 | |

| Hâ‚‚O (14) | QWC | 1.00 (baseline) | 1.00 (baseline) | 0.92 |

| FC | 0.65 | 0.69 | 1.12 | |

| GALIC | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.89 |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Framework for Grouping Strategies

Rigorous evaluation of measurement grouping strategies requires a standardized benchmarking approach:

Hamiltonian Selection: Test on a series of molecular Hamiltonians of increasing complexity (from Hâ‚‚ to Hâ‚‚O) generated through classical electronic structure codes [4].

Device Modeling: Implement realistic noise models based on characterized quantum hardware (e.g., IBM and IonQ processors) including gate infidelities, coherence times, and measurement errors [4].

Grouping Algorithm Application: Apply FC, QWC, and hybrid grouping algorithms to the Hamiltonian terms, recording the number of groups and estimated measurement costs [4].

Variance Estimation: For each grouping strategy, compute the estimator variance as (\text{Var}[\hat{H}] = \sum{i=1}^{M} |ci|^2 \text{Var}[\hat{Pi}] / ni), where (n_i) is the number of measurements allocated to group i [4].

Bias Evaluation: Quantify estimator bias introduced by noisy entangling operations in FC groups through comparison with noiseless simulations [4].

Hardware-Aware Optimization Protocol

The GALIC framework implements a specialized experimental protocol for device-aware optimization:

Device Characterization: Profile target quantum processor for qubit-specific error rates, connectivity constraints, and two-qubit gate fidelities [4].

Connectivity-Aware Grouping: Form initial QWC groups, then selectively merge groups using FC relations only when the required entangling operations can be implemented efficiently given device connectivity [4].

Noise-Adaptive Diagonalization: Design measurement circuits that minimize depth and maximize fidelity by exploiting device-specific native gate sets and connectivity [4].

Dynamic Resource Allocation: Allocate measurement shots across groups proportional to both coefficient magnitude (|c_i|) and group variance, with adjustments for device-specific error rates [4].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for hardware-aware measurement grouping, showing the sequence from Hamiltonian decomposition through to energy estimation with device-specific optimizations.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Measurement Optimization Studies

| Resource/Tool | Function | Example Implementation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Generate molecular Hamiltonians as Pauli sums | OpenFermion, PSI4, PySCF | ||

| Grouping Algorithms | Partition Pauli terms into measurable groups | GALIC [4], Sorted Insertion [4] | ||

| Device Noise Models | Simulate realistic hardware behavior | IBM Qiskit Noise Models, Cirq Noise | ||

| Variance Estimation Tools | Predict measurement overhead | Custom estimators based on (\sum | c_i | ^2 \text{Var}[\hat{Pi}]/ni) [4] |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Reduce bias from noisy operations | Zero-noise extrapolation, symmetry verification [1] | ||

| Hardware Benchmarks | Validate grouping strategies on real devices | IBM Quantum, IonQ, Quantinuum [6] |

Implications for Pharmaceutical Research and Beyond

The development of advanced measurement grouping strategies has significant implications for quantum chemistry applications in pharmaceutical research. By reducing the measurement overhead by over 20% compared to standard QWC approaches [4], hybrid frameworks like GALIC bring chemically accurate quantum computations closer to practicality on NISQ devices. This enhancement is particularly valuable for drug discovery pipelines, where efficient calculation of molecular interaction energies and reaction barriers could accelerate screening of candidate compounds.

Furthermore, the research reveals that error suppression has a 13× larger impact on device-aware estimator variance than qubit connectivity [4] [5], suggesting that improving gate fidelity may be more critical than expanding qubit connectivity for near-term quantum advantage in pharmaceutical applications. This insight directs hardware development priorities toward error reduction rather than architectural complexity.

The quantum measurement bottleneck represents a fundamental challenge for practical quantum chemistry on NISQ devices. While qubit-wise commutativity provides a noise-resilient foundation for measurement grouping, emerging hybrid frameworks like GALIC demonstrate that context-aware interpolation between FC and QWC strategies can significantly reduce measurement overhead while maintaining accuracy. For pharmaceutical researchers leveraging quantum computations, these advances in measurement optimization translate directly to expanded problem sizes, improved accuracy, and reduced computational costs. As quantum hardware continues to evolve with improvements in both scale and fidelity, sophisticated measurement strategies will remain essential for extracting maximal computational power from NISQ devices for drug discovery applications.

In quantum mechanics, the concept of commutativity serves as a fundamental indicator of the relationship between physical observables and the mathematical structure of the theory. The commutator of two operators, defined as $[A,B] = AB - BA$, provides a precise mathematical framework for determining whether two observables can be simultaneously measured with arbitrary precision [7] [8]. When $[A,B] = 0$, the operators commute, indicating the existence of a common set of eigenstates and the possibility of simultaneous measurement without mutual disturbance [9] [10]. The physical significance of the commutator extends beyond a mere mathematical construct; it encodes essential information about how the measurement of one observable affects the state of a system when followed by measurement of another observable [11].

In the context of quantum computation and specifically measurement grouping algorithms, understanding commutativity—particularly specialized forms like qubit-wise commutativity—becomes crucial for optimizing resource utilization and reducing measurement overhead [12]. This technical guide explores the mathematical foundations of commutativity, its physical interpretations, and its practical applications in quantum computing, with particular emphasis on its role in measurement reduction techniques for variational quantum algorithms.

Mathematical Foundations of Commutativity

Basic Definitions and Properties

In quantum mechanics, physical observables are represented by self-adjoint operators acting on a Hilbert space [7]. The commutator of two operators $A$ and $B$ is defined as:

$$[A, B] = AB - BA$$

This mathematical object possesses several important algebraic properties [8]:

- Anticommutativity: $[A, B] = -[B, A]$

- Bilinearity: $[aA + bB, C] = a[A, C] + b[B, C]$ for scalars $a, b$

- Product Rule: $[A, BC] = [A, B]C + B[A, C]$

- Jacobi Identity: $[A, [B, C]] + [B, [C, A]] + [C, [A, B]] = 0$

These properties establish the commutator as a fundamental algebraic structure in quantum theory.

Complete Sets of Commuting Observables (CSCO)

A complete set of commuting observables (CSCO) refers to a set of mutually commuting operators whose common eigenvectors can be used as a basis to express any quantum state [9]. For operators with discrete spectra, a CSCO is a set of commuting observables whose simultaneous eigenspaces span the Hilbert space with linearly independent eigenvectors that are uniquely specified by corresponding sets of eigenvalues [9].

The significance of CSCOs lies in their ability to provide a unique labeling of quantum states. When degeneracy exists in the energy spectrum alone, additional commuting observables are needed to distinguish between eigenstates [9]. For instance, in the case of the hydrogen atom, the Hamiltonian exhibits degeneracy, requiring additional quantum numbers ($n$, $l$, $ml$, $ms$) corresponding to commuting observables to fully specify the state.

Table 1: Examples of Commuting and Non-Commuting Observables

| Commuting Observables | Non-Commuting Observables | Commutator Value |

|---|---|---|

| Position components ($x$, $y$, $z$) | Position and momentum in same direction ($x$, $p_x$) | $[\hat{x}, \hat{p}_x] = i\hbar$ |

| Momentum components ($px$, $py$, $p_z$) | Different components of angular momentum ($Lx$, $Ly$) | $[Lx, Ly] = i\hbar L_z$ |

| Hamiltonian and parity in symmetric systems | Position and kinetic energy | Non-zero |

Physical Interpretation of Commutativity

Measurement Compatibility

The physical significance of commutativity becomes apparent when considering quantum measurements. Two observables $A$ and $B$ are compatible (can be measured simultaneously) if and only if their commutator vanishes: $[A, B] = 0$ [11] [10]. This mathematical condition ensures the existence of a common eigenbasis ${|u_n\rangle}$ such that:

$$\hat{A}|u{n}\rangle=an|u{n}\rangle$$ $$\hat{B}|u{n}\rangle=bn|u{n}\rangle$$

When two observables commute, measuring one does not disturb the eigenstate of the other [10]. If a system is prepared in a common eigenstate $|ui\rangle$ of both operators, measuring $A$ yields $ai$ with certainty, and subsequently measuring $B$ yields $bi$ with certainty, with the state remaining unchanged as $|ui\rangle$ throughout the process [10].

Commutativity and Disturbance

For non-commuting observables ($[A, B] \neq 0$), the measurement process introduces fundamental disturbances. The commutator $[A,B]$ quantifies the extent to which the action of $B$ changes the value of the dynamical variable $A$, and vice versa [11]. This relationship is formally captured in generalized uncertainty principles, which establish fundamental limits on the precision with which incompatible observables can be simultaneously known [7].

The most famous example of non-commutativity is the position-momentum uncertainty relation, derived from $[\hat{x}, \hat{p}] = i\hbar$, which leads to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle $\Delta x \Delta p \geq \hbar/2$ [8]. This non-commutativity fundamentally distinguishes quantum mechanics from classical physics.

Figure 1: Measurement outcomes based on commutativity of observables

Commutativity in Quantum Computation

Qubit-Wise Commutativity and Measurement Grouping

In quantum computing, particularly for variational quantum algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), measurement reduction through operator grouping is essential for practical implementation [12]. Two primary grouping schemes have been developed:

- Full commutativity (FC): Operators commute according to the standard definition $[A,B] = 0$

- Qubit-wise commutativity (QWC): A stricter condition where operators commute component-wise on each qubit

Qubit-wise commutativity represents a special case where Pauli operators act on different qubits or identical Pauli operators act on the same qubits [12]. This form of commutativity is particularly valuable in near-term quantum devices as it enables simultaneous measurement with minimal circuit overhead.

Recent research has introduced hybrid approaches, such as the GALIC framework (Generalized backend-Aware pauLI Commutation), which interpolates between FC and QWC to optimize measurement efficiency while accounting for device-specific noise characteristics and connectivity constraints [12]. These advanced commutativity relations can reduce estimator variance by an average of 20% compared to standard QWC approaches [12].

Mathematical Formulation of Qubit-Wise Commutativity

For multi-qubit systems, quantum states are described using tensor product spaces. The general state of an n-qubit system can be expressed as:

$$|\psi\rangle = \sum{i1,i2,...,in \in {0,1}} a{i1i2...in}|i1\rangle \otimes |i2\rangle \otimes \cdots \otimes |i_n\rangle$$

where the complex coefficients satisfy the normalization condition $\sum |a{i1i2...in}|^2 = 1$ [13].

In this context, qubit-wise commutativity imposes that for two operators $A$ and $B$, composed of tensor products of single-qubit operators:

$$A = \bigotimes{k=1}^n Ak, \quad B = \bigotimes{k=1}^n Bk$$

the condition $[Ak, Bk] = 0$ must hold for all qubits $k = 1, \ldots, n$. This ensures that measurements can be performed independently on each qubit without mutual disturbance.

Table 2: Commutativity Types in Quantum Measurement Grouping

| Commutativity Type | Mathematical Condition | Measurement Implications | Resource Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Commutativity (FC) | $[A,B] = AB - BA = 0$ | Can be measured simultaneously | May require entangling gates for measurement |

| Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC) | $[Ak, Bk] = 0$ for all qubits $k$ | Can be measured with single-qubit operations | Minimal overhead, suitable for NISQ devices |

| k-Commutativity | Intermediate between FC and QWC | Balanced trade-off between measurements and circuit depth | Adaptive based on device constraints |

Figure 2: Hierarchy of commutativity relations in quantum measurement

Advanced Commutativity Concepts

Generalized Measurement and POVMs

In generalized quantum measurement theory, projective measurements are extended to Positive Operator-Valued Measures (POVMs) [7]. A POVM is a set of positive semi-definite operators ${F_i}$ that sum to the identity:

$$\sum{i=1}^n Fi = I$$

The probability of obtaining outcome $i$ when measuring state $\rho$ is given by $\text{Prob}(i) = \text{tr}(\rho F_i)$ [7].

POVMs generalize projective measurements and allow for the description of measurement effects on subsystems. The commutativity concepts extend to POVMs, where commuting POVMs represent compatible measurements that can be performed simultaneously without disturbance.

State-Dependent and Return Value Commutativity

Beyond the standard commutativity definitions, more refined concepts have been developed for specific applications:

State-dependent commutativity recognizes that certain operations may commute only when applied to specific quantum states [14]. Formally, two operations $p$ and $q$ on the same object are commutative in object state $\sigma$ if for all possible sequences of operations $\omega$, the return parameters in the concatenated sequence $pq\omega$ applied to state $\sigma$ are identical to those in the sequence $qp\omega$ applied to $\sigma$ [14].

Return value commutativity extends this concept by considering operation executions including their return values, not just their input parameters [14]. This approach enables more nuanced commutativity relations that can enhance concurrency in quantum and classical distributed systems.

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

Methodology for Commutativity Verification

Experimental verification of commutativity relationships in quantum systems follows these key protocols:

- State Preparation: Initialize the system in a known state $|\psi\rangle$

- Sequential Measurement: Measure $A$ followed by $B$ on multiple identical preparations

- Reverse Sequence: Measure $B$ followed by $A$ on a fresh set of preparations

- Comparison: Statistically compare outcome distributions for the two sequences

- Commutation Test: If the measurement statistics are identical within experimental error, the operators commute

For multi-qubit systems, this procedure is extended to verify qubit-wise commutativity by testing component operations on individual qubits.

Research Reagent Solutions for Commutativity Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Commutativity and Measurement Studies

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | Hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for ground state energy estimation | Quantum chemistry simulations [12] |

| Pauli Operator Sets | Tensor products of Pauli matrices ($X, Y, Z, I$) | Observable representation in quantum systems [12] |

| GALIC Framework | Generalized backend-Aware pauLI Commutation | Adaptive measurement grouping [12] |

| Quantum State Tomography | Complete characterization of quantum states | Verification of state preservation under commutative measurements |

| Randomized Measurement Protocols | Efficient estimation of multiple observables | Scalable verification of commutativity relations [12] |

| Tioxaprofen | Tioxaprofen, CAS:40198-53-6, MF:C18H13Cl2NO3S, MW:394.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Talatisamine | Talatisamine, MF:C24H39NO5, MW:421.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Commutativity serves as a fundamental organizing principle in quantum mechanics, with profound implications for both foundational theory and practical applications in quantum computing. From the basic mathematical definition $[A,B] = AB - BA$ to specialized forms like qubit-wise commutativity, this concept enables the classification of observables based on their mutual measurability.

In the context of quantum computation, particularly for measurement grouping in variational algorithms, understanding the hierarchy of commutativity relations—from full commutativity through k-commutativity to qubit-wise commutativity—provides essential tools for optimizing resource utilization on near-term quantum devices. Advanced frameworks like GALIC demonstrate how device-aware commutativity relations can significantly reduce measurement overhead while maintaining estimation accuracy.

As quantum hardware continues to advance, the refinement of commutativity concepts and their application to measurement reduction will play an increasingly important role in enabling practical quantum advantage for computational problems in chemistry, materials science, and optimization.

In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, efficient measurement of observables represents one of the most significant bottlenecks in variational quantum algorithms such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE). The molecular Hamiltonians central to quantum chemistry applications are typically expressed as linear combinations of hundreds or even thousands of Pauli terms, creating a substantial measurement challenge [15]. Within this context, the strategic grouping of compatible observables has emerged as a crucial optimization technique, with qubit-wise commutativity (QWC) and full commutativity (FC) representing two fundamental approaches with distinct trade-offs [12] [16].

This technical guide examines the critical distinction between these commutativity paradigms, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for optimizing quantum measurements. The distinction is not merely theoretical; it directly impacts measurement efficiency, circuit depth, and ultimately the feasibility of quantum simulations on current hardware. We explore the mathematical foundations, practical implementations, and performance characteristics of both approaches, enabling informed selection based on specific research constraints and objectives.

Mathematical Foundations and Definitions

The Measurement Problem in Quantum Algorithms

Quantum algorithms for electronic structure determination, particularly VQE, estimate molecular ground state energies by measuring the expectation value of a qubit Hamiltonian ( H ), expressed as: [ H = \sum{i} ci hi ] where ( hi ) are Pauli strings (tensor products of Pauli operators ({I, \sigmax, \sigmay, \sigmaz})) and ( ci ) are real coefficients [15]. The expectation value ( \langle H \rangle ) is obtained by measuring each term individually: [ \langle H \rangle = \sumi ci \langle h_i \rangle ] For complex molecules, the number of terms can grow dramatically—from 15 for H₂ to 1,086 for H₂O in one example [15]—making naïve measurement approaches prohibitively expensive.

Commutativity in Quantum Mechanics

In quantum mechanics, two observables ( A ) and ( B ) are said to commute if their commutator vanishes: ([A, B] = AB - BA = 0). Commuting operators share a common set of eigenvectors and can be measured simultaneously without disturbing each other's measurement outcomes [7] [17]. This fundamental principle enables the grouping of multiple compatible observables into a single measurement circuit.

Formal Definitions of QWC and FC

Table: Comparison of Commutativity Types for Pauli Strings P and Q

| Commutativity Type | Mathematical Definition | Physical Interpretation | Clifford Circuit Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Commutativity (FC) | ([P, Q] = PQ - QP = 0) | Operators commute as a whole | Multi-qubit entangling Clifford gates ((O(n^2/\log n)) depth) [16] |

| Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC) | ([pi, qi] = 0) for all qubits (i) | Operators commute on every qubit individually | Single-qubit Clifford gates (depth-1 circuit) [16] |

Full Commutativity (FC) represents the standard, mathematical notion of commutativity. Two Pauli strings ( P ) and ( Q ) fully commute if their product commutes regardless of their structure [16]. FC groups can be simultaneously measured using a Clifford unitary ( U ) that diagonalizes the entire set, but this transformation may require substantial quantum circuit depth—up to ( O(n^2/\log n) ) Clifford gates for ( n )-qubit systems [16].

Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC) imposes a stricter condition: Pauli strings ( P = \bigotimes{i=1}^n pi ) and ( Q = \bigotimes{i=1}^n qi ) qubit-wise commute if, for every qubit ( i ), the single-qubit Pauli operators ( pi ) and ( qi ) commute [16]. This stronger condition ensures that measurements can be performed using only single-qubit basis rotations (depth-1 circuits), but typically results in a larger number of measurement groups compared to FC.

The diagram above illustrates the logical relationship between QWC and FC. Critically, QWC implies FC (all qubit-wise commuting operators fully commute), but the converse is not necessarily true [16]. This hierarchy has profound implications for measurement efficiency.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Grouping Algorithms and Strategies

Multiple algorithmic approaches exist for grouping Pauli terms into measurable fragments:

QWC Grouping: Typically implemented using graph coloring algorithms where each Pauli term represents a vertex, with edges connecting non-commuting terms. The resulting graph coloring corresponds to measurement groups [17].

FC Grouping: Leverages the full commutativity relation, often employing more complex grouping algorithms that account for the full commutator structure rather than individual qubit operations [12].

Greedy Grouping: A practical approach that sequentially builds groups by selecting the largest ungrouped terms first, empirically producing fragments with varying variances that can reduce the sum of variance square roots [18].

Overlapping Grouping: An advanced technique allowing Pauli products to appear in multiple groups, exploiting their compatibility with different measurement contexts to further reduce measurement counts [18].

Measurement and Estimation Protocols

The general workflow for efficient Hamiltonian measurement involves:

Hamiltonian Preparation: Generate the qubit Hamiltonian through fermion-to-qubit mapping (e.g., Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformations) [15].

Commutativity Analysis: Identify commuting subsets using either QWC or FC criteria based on hardware constraints and efficiency targets.

Group Formation: Apply grouping algorithms (graph coloring, greedy, or overlapping methods) to partition the Hamiltonian into measurable fragments.

Circuit Implementation: For each group, implement the appropriate diagonalizing circuit:

- QWC: Single-qubit rotations to the Z-basis

- FC: Multi-qubit Clifford circuits potentially requiring entangling gates

Measurement Allocation: Distribute measurement shots optimally across groups, typically proportional to the variance of each fragment [18].

Expectation Value Estimation: Compute ( \langle H \rangle = \sum\alpha \langle A\alpha \rangle ) from the grouped measurements, where ( A_\alpha ) represents each measurable fragment.

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Empirical Comparison of Grouping Strategies

Recent research provides quantitative comparisons of various grouping approaches across molecular systems:

Table: Estimator Variances for Different Molecules and Grouping Strategies (Data from Yen et al. 2023 [18])

| Molecular System | LF Algorithm | Sorted Insertion (SI) | IMA | GMA | ICS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | 0.136 | 0.136 | 0.136 | 0.136 | 0.136 |

| LiH | 5.84 | 2.09 | 1.73 | 1.52 | 0.976 |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14.3 | 6.34 | 5.60 | 5.26 | 4.29 |

| Hâ‚‚O | 116 | 48.2 | - | - | - |

The table demonstrates that advanced grouping strategies (IMA, GMA, ICS) consistently outperform simpler approaches (LF, SI), with the most flexible methods achieving the lowest estimator variances. This variance reduction directly translates to fewer required measurements for a target accuracy.

Resource Requirements and Trade-offs

Table: Resource Comparison Between QWC and FC Grouping Strategies

| Resource Metric | QWC Grouping | FC Grouping | Hybrid Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Groups | Higher | Lower (up to 90% reduction vs. no grouping [15]) | Intermediate |

| Circuit Depth | Shallow (depth-1 [16]) | Deeper ((O(n^2/\log n)) Cliffords [16]) | Configurable |

| Classical Overhead | Moderate | Higher | Variable |

| Hardware Resilience | More resilient to noise | Sensitive to gate errors | Architecture-dependent |

| Variance Reduction | 20% average improvement vs. no grouping [12] | Potentially higher reduction | Superior (e.g., ICS in Table 1) |

The performance advantage of FC grouping diminishes in noisy environments, where deeper circuits exacerbate error accumulation. Studies indicate that error suppression has a more than 10× larger impact on estimator variance than qubit connectivity in practical implementations [12].

Advanced Hybrid Frameworks

Interpolation Between QWC and FC

The fundamental trade-off between QWC and FC has motivated research into hybrid approaches that interpolate between these extremes:

k-Commutativity: A generalized framework that partitions ( n )-qubit systems into blocks of size ( k ), where ( k=1 ) corresponds to QWC and ( k=n ) corresponds to FC [16]. This approach enables a controllable trade-off between measurement group count and circuit depth.

GALIC Framework: A backend-aware grouping strategy that dynamically adapts to device-specific noise characteristics and connectivity constraints, achieving a 20% average reduction in estimator variance compared to standard QWC [12].

Table: Key Experimental Resources for Measurement Grouping Research

| Resource | Type | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grouping Algorithms | Software | Partition Pauli terms into measurable groups | Graph coloring, greedy algorithms, sorted insertion [18] |

| Clifford Compilers | Software | Generate efficient diagonalizing circuits | PyZX [16], graph-based compilers [16] |

| Variance Estimators | Analytical Tool | Optimize measurement allocation | Classical proxies (Hartree-Fock, CISD) [18] |

| Classical Shadows | Protocol | Reduce measurements via randomized tomography | Shadow estimation techniques [18] |

| Quantum Hardware | Physical System | Execute measurement circuits | Superconducting qubits, ion traps [12] |

The critical distinction between qubit-wise commutativity and full commutativity represents a fundamental design consideration in quantum measurement optimization. QWC offers practical advantages through shallow circuits and resilience to noise, while FC provides theoretical efficiency through fewer measurement groups. The emerging paradigm of hybrid, context-aware commutativity frameworks offers the most promising path forward, enabling researchers to tailor measurement strategies to specific molecular systems and hardware capabilities.

For drug development professionals leveraging quantum simulations, these optimization techniques directly impact the feasibility and accuracy of molecular energy calculations. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, the sophisticated application of commutativity principles will remain essential for extracting meaningful scientific insights from quantum computations.

The Impact of Hamiltonian Scaling on Measurement Requirements

Accurately measuring the expectation value of quantum Hamiltonians is a fundamental task in quantum computation, central to algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) which target quantum chemistry and drug discovery applications. However, as Hamiltonians scale to model larger, more complex molecular systems, the required number of quantum measurements grows rapidly, posing a significant bottleneck for near-term quantum devices. This challenge is acutely felt by researchers and drug development professionals seeking to utilize quantum computing for molecular energy estimation. The primary strategy for mitigating this measurement overhead involves grouping Hamiltonian terms into simultaneously measurable fragments. This technical guide examines the impact of Hamiltonian scaling on measurement requirements, with a specific focus on the framework of qubit-wise commutativity and its extensions for efficient measurement grouping. We will explore how the number of terms in a molecular Hamiltonian grows with system size, the resulting measurement complexities, and the experimental protocols that leverage commutativity to achieve measurement efficiency necessary for practical applications like pharmaceutical research.

Hamiltonian Scaling and the Measurement Problem

The Structure of Molecular Hamiltonians

In quantum chemistry, the electronic Hamiltonian of a molecule is expressed in a second-quantized form, which is then mapped to a qubit representation via transformations such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev. The resulting qubit Hamiltonian takes the form of a linear combination of Pauli strings:

[ \hat{H} = \sum_{\alpha} c^{[\alpha]} P^{[\alpha]} ]

where each ( P^{[\alpha]} ) is a tensor product of Pauli operators ((I, X, Y, Z)) acting on (n) qubits, and ( c^{[\alpha]} ) are real coefficients [19]. The number of these Pauli terms, ( N_P ), is a critical parameter determining the measurement complexity. For molecular systems, the number of Pauli terms grows polynomially with the number of qubits (which in turn scales with the size of the molecular active space). Research on the BODIPY-4 molecule demonstrates this scaling, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Growth of Pauli Terms with System Size for the BODIPY-4 Molecule

| Qubits | Number of Pauli Strings |

|---|---|

| 8 | 361 |

| 12 | 1,819 |

| 16 | 5,785 |

| 20 | 14,243 |

| 24 | 29,693 |

| 28 | 55,323 |

Source: Adapted from Korhonen et al. [20]

This growth, approximately ( \mathcal{O}(N^4) ) for a system with (N) spatial orbitals [20], presents a fundamental challenge: directly measuring each term individually would require a number of measurement circuits that also grows polynomially, making large molecules prohibitively expensive to simulate.

The Expectation Value Estimation Problem

The goal in many quantum algorithms is to estimate the expectation value ( \langle \psi | \hat{H} | \psi \rangle ) for a prepared quantum state ( | \psi \rangle ). On current quantum hardware, the standard procedure involves:

- Partitioning the Hamiltonian into measurable fragments: ( \hat{H} = \sum{\alpha} \hat{A}{\alpha} ).

- Rotating each fragment into a measurable basis: ( \hat{A}{\alpha} = \hat{U}{\alpha}^{\dagger} \hat{M}{\alpha} \hat{U}{\alpha} ), where ( \hat{M}_{\alpha} ) is a linear combination of (Z)-Pauli operators.

- Measuring the state ( \hat{U}{\alpha} | \psi \rangle ) in the computational basis to estimate ( \langle \psi | \hat{A}{\alpha} | \psi \rangle ).

The total number of measurements ( M ) required to achieve a precision ( \epsilon ) is governed by the variances of the fragments: [ \epsilon \propto \frac{ \sum{\alpha} \sqrt{\text{Var}{\psi}(\hat{A}{\alpha}) } }{\sqrt{M}} ] where ( \text{Var}{\psi}(\hat{A}{\alpha}) = \langle \psi | \hat{A}{\alpha}^{2} | \psi \rangle - \langle \psi | \hat{A}_{\alpha} | \psi \rangle^{2} ) [19]. Efficient measurement strategies therefore aim to construct fragments that minimize this sum of standard deviations, directly reducing the total measurement cost ( M ).

Commutativity Frameworks for Measurement Grouping

The core strategy for reducing the number of measurement circuits is to group as many Pauli terms as possible into a single fragment ( \hat{A}_{\alpha} ). The ability to measure terms simultaneously is determined by their commutativity. This guide focuses on three key frameworks.

Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC)

Definition: Two Pauli strings ( P ) and ( Q ) are said to qubit-wise commute if, for every qubit ( i ), the single-qubit Pauli operators ( Pi ) and ( Qi ) commute [21] [19]. That is, ( [Pi, Qi] = 0 ) for all ( i ).

Implications for Measurement: QWC is a stronger condition than general commutativity. If all terms in a fragment are pairwise QWC, there exists a unitary ( \hat{U}_{\alpha} ) composed solely of single-qubit Clifford gates that rotates the entire fragment into a linear combination of (Z)-Pauli operators [19]. This results in a measurement circuit with minimal depth (a depth of 1 for the basis change), which is highly desirable on noisy hardware.

Figure 1: Measurement workflow using Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC) grouping.

Full Commutativity (FC)

Definition: Two Pauli strings ( P ) and ( Q ) fully commute if their commutator ( [P, Q] = PQ - QP = 0 ), regardless of whether they commute qubit-wise.

Implications for Measurement: FC is a weaker condition than QWC, allowing for larger and fewer groups. Measuring a fully commuting group requires a unitary ( \hat{U}_{\alpha} ) that can be a multi-qubit Clifford circuit. While this can be compiled efficiently, it results in a deeper circuit than the single-qubit rotations used for QWC groups [19]. This introduces a trade-off: reduced measurement count at the cost of increased circuit depth and potential gate errors.

k-Commutativity: An Interpolating Framework

Definition: A recently introduced framework, k-commutativity, interpolates between QWC ((k=1)) and FC ((k=n)). Two Pauli strings are defined to k-commute if the string can be divided into contiguous blocks of size (k), and the corresponding blocks of the two Paulis commute [21].

Implications for Measurement: This framework provides a smooth trade-off. Grouping by (k)-commutativity allows for a reduced number of groups compared to QWC, while the required unitary ( \hat{U}_{\alpha} ) is less complex and of lower depth than that for a fully commuting group. As ( k ) increases, the number of groups decreases, but the circuit depth required for the basis transformation increases [21]. This offers a tunable parameter for optimizing measurement protocols based on specific hardware capabilities and error profiles.

Figure 2: Workflow for the k-commutativity grouping framework.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

This section details the practical methodologies for implementing the grouping strategies discussed, enabling researchers to replicate and apply these techniques.

Protocol 1: Greedy Grouping with Qubit-Wise Commutativity

This is a widely used heuristic for constructing measurement fragments.

- Objective: To partition the Hamiltonian's Pauli terms into a minimal number of QWC groups.

- Procedure:

- Input: List of Pauli terms ( {P^{[\alpha]}} ) and their coefficients ( {c^{[\alpha]}} ).

- Initialize: Create an empty list of groups ( G ).

- Iterate: While the list of Pauli terms is not empty: a. Select the first term ( P ) in the list as a seed for a new group ( G{\text{new}} ). b. For every remaining term ( Q ) in the list, check if ( Q ) qubit-wise commutes with every term currently in ( G{\text{new}} ). c. If yes, move ( Q ) into ( G{\text{new}} ). d. Add ( G{\text{new}} ) to the list of groups ( G ).

- Considerations: The greedy nature of this algorithm makes it fast and simple to implement. However, the initial ordering of the Pauli terms can influence the final number of groups, and the solution is not guaranteed to be globally optimal. Furthermore, it only utilizes QWC, potentially missing opportunities for larger groups afforded by FC.

Protocol 2: Overlapping Grouping via Covariance Estimation

A more advanced strategy moves beyond disjoint groups, allowing a single Pauli term to be measured in multiple different fragments.

- Objective: Leverage the compatibility of some Pauli terms with multiple groups to create an optimized measurement strategy that minimizes the total estimator variance.

- Procedure:

- Input: A set of candidate measurable groups ( { \hat{A}{\alpha} } ) (which can be generated via QWC, FC, or other methods).

- Identify Overlaps: For each Pauli term ( P^{[\alpha]} ), list all groups in which it can be measured.

- Covariance Estimation: Using a classical proxy (e.g., Hartree-Fock state) or preliminary quantum measurements, estimate the covariance matrix ( \text{Cov}{\psi}(\hat{A}{\alpha}, \hat{A}{\beta}) ) between the fragments.

- Optimize Measurement Allocation: Solve a convex optimization problem to determine the number of measurements ( m{\alpha} ) to allocate to each fragment ( \hat{A}{\alpha} ), minimizing the total variance ( \text{Var}(\sum{\alpha} w{\alpha} \bar{A}{\alpha}) ) for a linear estimator, subject to ( \sum{\alpha} m_{\alpha} = M ) [19].

- Considerations: This framework is general and can lead to a severalfold reduction in the number of measurements compared to non-overlapping methods [19]. It connects traditional grouping approaches with modern techniques from shadow tomography. The primary overhead is the need for a priori variance or covariance estimates.

Table 2: Comparison of Measurement Grouping Frameworks

| Framework | Grouping Condition | Circuit Depth for U_α | Number of Groups | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC) | Commute on every qubit | Low (Single-qubit gates) | Highest | Minimal circuit depth, low error | Largest number of groups |

| Full Commutativity (FC) | Commute as operators | High (Multi-qubit Cliffords) | Lowest | Minimal number of groups | Higher circuit depth and gate errors |

| k-Commutativity | Commute on blocks of k qubits | Medium (Tunable with k) | Medium (Tunable with k) | Provides a smooth trade-off between group count and circuit depth | Requires selection of optimal k |

| Overlapping Groups | Compatible with multiple groups (QWC/FC/k) | Depends on base groups | Depends on base groups | Can achieve lowest total variance | Requires covariance estimation and optimization |

Case Study: High-Precision Measurement on Near-Term Hardware

A 2024 study by Korhonen et al. provides a concrete example of applying advanced measurement techniques to achieve high-precision results relevant to drug development [20].

- System: The Boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY) molecule, a fluorescent dye used in medical imaging and biolabelling, was studied in active spaces ranging from 8 to 28 qubits.

- Objective: Estimate the energy of the Hartree-Fock state for the ( S0 ), ( S1 ), and ( T_1 ) electronic states to chemical precision (1.6 mHa).

- Techniques Applied:

- Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements: Allowed for the estimation of multiple observables from the same data and provided a seamless interface for error mitigation.

- Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): Characterized and mitigated readout errors.

- Locally Biased Random Measurements: A shot-frugal technique that prioritizes measurement settings with a larger impact on the energy estimation.

- Blended Scheduling: Mitigated time-dependent noise by interleaving circuits for different Hamiltonians and QDT.

- Result: The combined techniques reduced the measurement error by an order of magnitude, from 1-5% down to 0.16%, bringing the result close to the target chemical precision despite high native readout errors (~1-2%) [20]. This demonstrates a viable path forward for precise molecular energy estimation on noisy hardware.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key computational and methodological "reagents" essential for conducting research in Hamiltonian measurement reduction.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Measurement Grouping Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Implementation Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pauli String Grouping Library (e.g., in Qiskit) | Implements algorithms (greedy, graph coloring) to group Pauli terms by QWC, FC, or k-commutativity. | Core utility for any measurement reduction protocol. Often integrated into quantum chemistry SDKs. | ||

| Classical Proxy Wavefunction (e.g., Hartree-Fock, CISD) | Provides initial estimates of ( \langle \psi | \hat{A}_{\alpha} | \psi \rangle ) and ( \text{Var}{\psi}(\hat{A}{\alpha}) ) for measurement allocation optimization. | Crucial for overlapping grouping and shot-allocation strategies. Accuracy of the proxy influences efficiency. |

| Clifford Circuit Compiler | Compiles the unitary ( \hat{U}_{\alpha} ) for rotating a group of commuting operators into the Z-basis into native gates. | Required for FC and k-commutativity grouping. Efficiency of compilation affects final circuit depth. | ||

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) Toolbox | Characterizes the noisy readout matrix of the quantum device to build an unbiased estimator for observables. | Essential for high-precision work, as it directly mitigates readout error [20]. | ||

| Variance/Covariance Estimator | Calculates the covariance matrix ( \text{Cov}{\psi}(\hat{A}{\alpha}, \hat{A}_{\beta}) ) for a given state and set of fragments. | Foundational component for the overlapping grouping framework. | ||

| Shot Allocation Optimizer | Solves the convex optimization problem to distribute a fixed number of shots among fragments to minimize total estimator variance. | Turns variance estimates into an actionable measurement plan. | ||

| 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate | 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate, CAS:206440-72-4, MF:C5H13O7P, MW:216.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | ||

| Batatasin Iv | Batatasin Iv, CAS:60347-67-3, MF:C15H16O3, MW:244.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The scaling of molecular Hamiltonians presents a formidable measurement challenge for quantum computing applications in drug development. The number of Pauli terms grows rapidly with system size, necessitating sophisticated strategies to make energy estimation feasible. The framework of qubit-wise commutativity provides a critical foundation for this task, enabling the grouping of terms into simultaneously measurable fragments with low circuit overhead. The development of more advanced concepts, such as k-commutativity and overlapping groups, offers a path to further significant reductions in measurement cost. As demonstrated by experimental implementations on current hardware, the combination of these grouping techniques with robust error mitigation can achieve the high precision required for meaningful molecular simulations. For researchers in the field, mastering these protocols and leveraging the associated "toolkit" of computational reagents is essential for pushing the boundaries of what is possible in quantum-accelerated drug discovery.

In the pursuit of practical quantum computing on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, efficient measurement strategies are paramount. The variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) and the quantum approximate optimization algorithm (QAOA), which are leading algorithms for quantum chemistry and optimization problems, require estimating the expectation value of a Hamiltonian. This Hamiltonian is typically a complex sum of numerous Pauli terms. A naïve approach of measuring each term independently in a separate quantum circuit is prohibitively expensive and wasteful of limited quantum resources.

This technical guide details the core concepts of Pauli Words, Observable Grouping, and Simultaneous Measurement as a unified framework for radically reducing the measurement overhead in quantum algorithms. The process is framed within the critical research context of qubit-wise commutativity (QWC), a specific and practical criterion for measurement grouping. By grouping compatible observables, researchers can measure multiple terms in a single circuit execution, minimizing the number of circuit runs, reducing the impact of noise, and accelerating the path to obtaining meaningful scientific results, such as in computational drug development.

Mathematical Foundations: Pauli Words and Commutativity

Pauli Words and Strings

A Pauli Word (or Pauli String) describes a multi-qubit operator defined as the tensor product of single-qubit Pauli operators. The fundamental Pauli operators are the identity (I) and the three Pauli matrices (X), (Y), and (Z) [22]. A Pauli Word (P) can be written as: [ P = \sigma^{(1)} \otimes \sigma^{(2)} \otimes \cdots \otimes \sigma^{(n)} ] where each (\sigma^{(i)} \in {I, X, Y, Z}) acts on the (i)-th qubit [23].

In software libraries like Cirq and PennyLane, these are implemented as core objects. For example, in PennyLane, a PauliWord is an immutable dictionary that maps wires (qubits) to their respective Pauli operators [23].

Table: Fundamental Single-Qubit Pauli Operators

| Operator | Matrix Representation | Eigenvalues | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| (I) | (\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}) | (+1) | Identity operator |

| (X) | (\begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 \ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}) | (\pm1) | Bit-flip operator |

| (Y) | (\begin{pmatrix} 0 & -i \ i & 0 \end{pmatrix}) | (\pm1) | Phase-bit-flip operator |

| (Z) | (\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & -1 \end{pmatrix}) | (\pm1) | Phase-flip operator |

Commutation and Anti-Commutation

The commutativity of Pauli Words is the cornerstone of simultaneous measurement. The commutator of two operators (A) and (B) is defined as ([A, B] = AB - BA). If ([A, B] = 0), the operators commute; otherwise, they do not.

Pauli operators obey specific commutation and anti-commutation relations [22]:

- Commutation Relation: ([\sigmaj, \sigmak] = 2i\varepsilon{jkl}\sigmal)

- Anti-commutation Relation: ({\sigmaj, \sigmak} = 2\delta_{jk}I)

Here, (\varepsilon{jkl}) is the Levi-Civita symbol and (\delta{jk}) is the Kronecker delta. Two Pauli Words commute if the number of qubits on which their corresponding single-qubit Paulis anti-commute is even. If this count is odd, they anti-commute [24].

The Principle of Simultaneous Measurement

Theoretical Basis

In quantum mechanics, two observables can be measured simultaneously if and only if their corresponding operators commute [24]. Commuting operators share a common set of eigenvectors. Measuring one observable in this shared eigenbasis projects the quantum state into a joint eigenvector of all commuting observables in the group, allowing the outcomes for all of them to be determined from the same measurement data without disturbing the state for the others [25].

For example, measuring the two-qubit Pauli observable (Z \otimes Z) is equivalent to measuring the parity of the two qubits. The measurement distinguishes between states where the qubits are the same ((|00\rangle), (|11\rangle), eigenvalue (+1)) and states where they are different ((|01\rangle), (|10\rangle), eigenvalue (-1)) [26]. This single measurement provides information about the correlation between the qubits, which is non-locally stored and not accessible by measuring individual qubits alone [26].

Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC)

Full commutativity (([A, B] = 0)) is a strict condition. A more relaxed but highly practical criterion is Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC). Two Pauli Words (A) and (B) are said to qubit-wise commute if, for every qubit (i), the single-qubit Pauli operators (\sigma^{(i)}A) and (\sigma^{(i)}B) commute [17].

This means that for each qubit, the corresponding Paulis must be either the same or the identity. Formally, for all (i), ([\sigma^{(i)}A, \sigma^{(i)}B] = 0). For example:

- (X \otimes I) and (Z \otimes I) do not QWC (on the first qubit, (X) and (Z) anti-commute).

- (X \otimes Z) and (X \otimes I) do QWC (same on first qubit, (Z) and (I) commute on the second).

QWC is a stronger condition than general commutativity; all QWC pairs commute, but not all commuting pairs are QWC. Its key advantage is operational simplicity: if observables QWC, they can be measured simultaneously by measuring each qubit individually in a basis determined by its non-identity Pauli operator in the group [17].

Observable Grouping Methodologies and Protocols

The process of observable grouping transforms a Hamiltonian (H = \sumi ci Pi) (where (Pi) are Pauli Words) into a minimal set of groups where all observables within a group can be measured simultaneously.

The Observable Grouping Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for efficient measurement via observable grouping.

Detailed Grouping Protocols

Protocol 1: Greedy Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC) Grouping

This is a common and efficient grouping strategy [17].

- Input: A list of Pauli Words ( {P1, P2, ..., P_k} ) from a Hamiltonian.

- Initialization: Create an empty list

groups. - Iteration: For each Pauli Word (Pi) in the list:

- Check against each existing group in

groups. - If (Pi) qubit-wise commutes with every observable in an existing group, add (Pi) to that group.

- If no such group is found, create a new group containing (Pi

and add it togroups`.

- Check against each existing group in

- Output: The list

groups, where each group is a set of qubit-wise commuting observables.

Protocol 2: Graph-Theoretic Minimum Clique Cover (MCC)

A more advanced method that can find fewer, larger groups, albeit with higher classical computational cost [17].

- Input: A list of Pauli Words ( {P1, P2, ..., P_k} ).

- Graph Construction: Create a graph (G) where:

- Each vertex represents a Pauli Word (P_i).

- An edge connects two vertices (Pi) and (Pj) if they commute (or QWC, depending on the criterion used).

- Clique Cover: Solve the Minimum Clique Cover problem on graph (G`. A clique is a subset of vertices where every two distinct vertices are connected. The clique cover is a set of cliques that covers all vertices.

- Output: Each clique in the cover corresponds to a group of simultaneously measurable observables.

Circuit Construction and Measurement

Once observables are grouped, a single quantum circuit is generated for each group.

- Basis Transformation: For a given group, determine the required single-qubit basis change for each qubit. This is defined by the non-identity Pauli operator(s) acting on that qubit within the group [26]:

- To measure (Z), no change is needed (measure in computational basis).

- To measure (X), apply a Hadamard gate (H) before measurement.

- To measure (Y), apply (S^\dagger) followed by (H) before measurement.

- Execution: Run the transformed circuit on a quantum processor or simulator for a sufficient number of "shots" (repetitions) to gather statistics.

- Post-Processing: From the resulting bitstrings, calculate the expectation value (\langle Pi \rangle) for each Pauli Word in the group. The expectation value of the Hamiltonian is then reconstructed as (\langle H \rangle = \sumi ci \langle Pi \rangle) [17].

Table: Basis Transformations for Pauli Measurement

| Target Pauli | Diagonalizing Gate Sequence | Equivalent Q# Operation |

|---|---|---|

| (Z) | (I) | Measure([PauliZ], [q]) |

| (X) | (H) | Measure([PauliX], [q]) |

| (Y) | (S^\dagger), then (H) | Measure([PauliY], [q]) |

Resource Analysis and Performance Gains

The resource savings from observable grouping are substantial and critical for applying VQE to problems in chemistry and drug development, such as determining molecular energies.

Quantitative Performance Data

The table below summarizes the typical reduction in the number of required measurement circuits achieved through different grouping strategies for various problem types [17].

Table: Measurement Grouping Performance for Quantum Algorithms

| Application | Problem Instance | No Grouping | Wire Grouping | QWC Grouping | Savings vs. Naïve |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QAOA | Max-Cut (QUBO) | ~180 | ~25 | ~1 | ~99% |

| Quantum Chemistry (VQE) | H(_2) Molecule | 15 | 7 | 5 | ~67% |

| Quantum Chemistry (VQE) | LiH Molecule | 637 | 295 | 122 | ~81% |

| Quantum Chemistry (VQE) | H(_6) Molecule | 3873 | 1565 | 599 | ~85% |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Software and Libraries

Several quantum software libraries provide built-in functionalities to automate observable grouping.

Table: Essential Software Tools for Observable Grouping Research

| Tool / Library | Grouping Functionality | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| PennyLane | qml.grouping.group_observables |

Supports both "qwc" and "commuting" (general) grouping strategies directly integrated into its QNode execution pipeline [17]. |

| Qiskit | CircuitSampler with grouping plugins |

Offers observable grouping utilities, often through plugins designed for advanced algorithms like VQE [17]. |

| Divi (Qoro) | High-level API abstraction | Automates the entire workflow from grouping to execution and post-processing, leveraging lower-level engines like PennyLane to simplify the user experience [17]. |

| Cirq | PauliString and PauliSum objects |

Provides the fundamental data structures for representing and manipulating linear combinations of Pauli terms, which are the prerequisites for implementing grouping algorithms [27]. |

| 10-Decarbamoyloxy-9-dehydromitomycin B | Mitomycin H | Research-grade Mitomycin H for laboratory investigation. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Carteolol | Carteolol Hydrochloride | Carteolol is a non-selective beta-adrenergic antagonist for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Experimental Protocol: Applying QWC to a VQE Simulation

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for running a VQE simulation with observable grouping, representative of an experiment to compute the ground state energy of a molecule like H(_2).

Step-by-Step Protocol

Problem Formulation:

- Input: Choose a molecule (e.g., H(_2)) and an interatomic distance.

- Action: Use a quantum chemistry package (e.g., OpenFermion, Pennylane's

qchemmodule) to generate the electronic structure Hamiltonian (H) in the Pauli basis. The output will be a list of coefficients (ci) and corresponding Pauli Words (Pi).

Observable Grouping:

- Input: The list of ({(ci, Pi)}) from Step 1.

- Action: Apply the Greedy QWC Grouping protocol (Section 4.2, Protocol 1) to this list. The output is (M) groups, (G1, G2, ..., G_M).

Ansatz and Parameter Initialization:

- Input: The number of qubits (n) and a chosen parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz), e.g., the Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) ansatz or a hardware-efficient ansatz.

- Action: Initialize the variational parameters (\vec{\theta}) to a starting guess (e.g., zeros, or a random value).

Quantum Circuit Execution Loop (For each optimization step):

- For each group (Gj):

- Construct the parameterized ansatz circuit with the current parameters (\vec{\theta}).

- Append Measurement Circuitry: For each qubit, determine the necessary basis-changing gates (see Table in Section 4.3) based on the non-identity Pauli operators in group (Gj

.</li> <li>Execute the complete circuit on a quantum backend for (S) shots (e.g., (S = 10,000). - Collect the measurement results (bitstrings).

- Classical Post-Processing:

- For each Pauli Word (Pi) in group (Gj), estimate its expectation value (\langle Pi \rangle) from the bitstrings obtained from (Gj)'s circuit.

- Compute the total energy estimate: (E(\vec{\theta}) = \sumi ci \langle P_i \rangle`.

- For each group (Gj):

Classical Optimization:

- Input: The computed energy (E(\vec{\theta})).

- Action: Use a classical optimizer (e.g., Nelder-Mead, BFGS) to propose new parameters (\vec{\theta}_{\text{new}}) with the goal of minimizing (E(\vec{\theta})).

- Loop: Repeat from Step 4 until convergence in energy is achieved.

The following diagram visualizes the iterative quantum-classical loop of the VQE algorithm, highlighting the integration of observable grouping.

Observable grouping, particularly using the qubit-wise commutativity criterion, is not merely an optional optimization but a fundamental technique for enabling practical quantum simulations on near-term hardware. By transforming the measurement problem into a classical problem of graph coloring or clique covering, researchers can achieve order-of-magnitude reductions in the quantum resource requirements for algorithms like VQE and QAOA. As quantum hardware continues to mature, the development of more sophisticated grouping strategies and their seamless integration into high-level quantum software stacks will be crucial for tackling increasingly complex problems in fields such as drug discovery and materials science.

Implementing QWC Grouping: From Theory to Practice in Quantum Chemistry Simulations

Step-by-Step Workflow for Observable Grouping and Measurement

In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, efficiently extracting information from quantum systems represents one of the most significant practical bottlenecks for applications ranging from quantum chemistry to optimization problems. The fundamental challenge stems from the need to measure complex molecular Hamiltonians, which are typically decomposed into sums of Pauli terms. For even modest-sized molecules, this decomposition can yield hundreds or thousands of individual terms requiring measurement. For instance, the water molecule (H₂O) requires measuring 1,086 Hamiltonian terms when mapped to a 14-qubit system [15]. A naïve approach of measuring each term in separate quantum circuits creates prohibitive overhead that scales polynomially with system size, making practical quantum advantage impossible without optimization strategies.

This technical guide addresses this "measurement problem" by providing a comprehensive workflow for observable grouping—a powerful technique that significantly reduces quantum resource requirements. We frame this discussion within ongoing research on qubit-wise commutativity, a specific commutativity relation that enables particularly efficient measurement protocols. By grouping compatible observables that can be measured simultaneously, researchers can reduce measurement overhead by up to 90% in some cases [15], dramatically accelerating variational algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) that are essential for quantum chemistry and drug discovery applications.

Theoretical Foundations: From Commutativity to Practical Grouping

Pauli Decomposition and the Measurement Problem

Quantum algorithms for electronic structure problems, particularly the Variational Quantum Eigensolver, estimate molecular ground state energies by measuring the expectation value of a qubit Hamiltonian ( H ), expressed as: [ H = \sumi ci hi ] where each ( hi ) is a Pauli string (tensor product of Pauli operators ( I, \sigmax, \sigmay, \sigmaz )) and ( ci ) are real coefficients [15]. The expectation value ( \langle H \rangle ) is obtained by measuring each term separately and computing the weighted sum: [ \langle H \rangle = \sumi ci \langle h_i \rangle ]

The measurement problem arises because each term ( \langle h_i \rangle ) typically requires numerous repetitions ("shots") on quantum hardware to achieve statistical precision, with the number of terms growing rapidly with molecular size. This creates a computational bottleneck, especially when quantum hardware access is limited and expensive [15].

Commutativity Relations for Observable Grouping

Observable grouping exploits the fundamental quantum mechanical property of commutativity to reduce measurement overhead. Two observables can be measured simultaneously if they commute, meaning their measurement order does not affect the outcomes. For Pauli strings, several commutativity relations enable practical grouping:

Full Commutativity: Two Pauli strings ( P ) and ( Q ) fully commute if ( [P, Q] = PQ - QP = 0 ). Fully commuting observables share a common eigenbasis and can be measured together using an appropriate basis transformation circuit [16].

Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC): Two Pauli strings ( P = \bigotimes{i=1}^n pi ) and ( Q = \bigotimes{i=1}^n qi ) qubit-wise commute if ( [pi, qi] = 0 ) for all qubits ( i ). This stronger condition implies full commutativity but not vice versa [16]. The significance of QWC is that it enables measurement with minimal circuit depth—typically requiring only single-qubit gates to diagonalize the observables simultaneously.

( k )-Commutativity: A recently introduced generalization that interpolates between qubit-wise commutativity (( k=1 )) and full commutativity (( k=n )). Two Pauli strings ( k )-commute if they commute when restricted to blocks of size ( k ) [16]. This provides a tunable trade-off between measurement circuit depth and the number of measurement groups.

The mathematical relationship between these commutativity concepts creates a hierarchical structure where qubit-wise commutativity implies ( k )-commutativity for all ( k \geq 1 ), which in turn implies full commutativity.

Algorithmic Framework for Grouping Strategies

The core algorithmic challenge in observable grouping is to partition the set of Hamiltonian Pauli terms into the minimum number of groups where all members within each group satisfy a specific commutativity relation. This can be framed as a graph coloring problem where vertices represent Pauli terms and edges connect commuting observables [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Observable Grouping Strategies

| Grouping Strategy | Commutativity Criterion | Circuit Depth | Number of Groups | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC) | Commutation on each qubit | Minimal (single layer of single-qubit gates) | Higher than full commutativity | NISQ devices with severe depth limitations |

| Full Commutativity | Traditional commutator vanishes | Higher (requires entangling gates for diagonalization) | Minimal | Fault-tolerant systems or high-coherence hardware |

| ( k )-Commutativity | Commutation on blocks of size ( k ) | Intermediate (depends on ( k )) | Intermediate, tunable | Balanced performance when moderate depth is acceptable |

| Classical Shadows | Randomized measurements | Varies | Not applicable (different approach) | Measuring many different observables |

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between these grouping strategies and their resource requirements:

Figure 1: Relationship between grouping strategies and their resource trade-offs. Qubit-wise commutativity requires the most groups but minimal circuit depth, while full commutativity requires fewer groups but greater depth. k-commutativity provides a tunable intermediate approach.

Step-by-Step Workflow for Observable Grouping and Measurement

Step 1: Hamiltonian Preparation and Pauli Decomposition

The workflow begins with generating the qubit Hamiltonian for the target molecular system:

Molecular Specification: Define the molecular structure (atomic species, coordinates, charge, spin multiplicity) and select a basis set (e.g., STO-3G, 6-31G) for electronic structure calculation.

Qubit Hamiltonian Generation:

- Perform a classical Hartree-Fock calculation to obtain molecular orbitals

- Select an active space for correlated calculations if necessary

- Transform the electronic Hamiltonian to qubit representation using Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation [15]

- Output the Hamiltonian as a linear combination of Pauli strings: ( H = \sumi ci P_i )

For example, a hydrogen molecule (Hâ‚‚) at bond length 0.7 angstroms yields a 4-qubit Hamiltonian with 15 Pauli terms after Jordan-Wigner transformation [15].

Step 2: Commutativity Analysis and Group Identification

This critical step identifies compatible observables that can be measured together:

Construct Commutativity Graph: Create a graph where each vertex represents a Pauli term, and edges connect terms satisfying the chosen commutativity relation (QWC, full commutativity, or ( k )-commutativity).

Graph Coloring Algorithm: Apply a graph coloring algorithm to partition the vertices into the minimum number of groups where all group members are connected (commuting). While exact graph coloring is NP-hard, efficient heuristic algorithms like largest-first or DSatur provide near-optimal solutions for practical problem sizes [17].

Group Refinement: For large Hamiltonians, consider iterative refinement or specialized algorithms for specific commutativity relations. For QWC, a greedy algorithm that assigns observables to unused qubits is particularly effective [17].

Table 2: Measurement Overhead Reduction Through Grouping for Molecular Systems

| Molecule | Qubit Count | Total Pauli Terms | Groups (No Grouping) | Groups (QWC) | Reduction Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | 4 | 15 | 15 | 8 | ~47% [15] |

| LiH | 10 | 437 | 437 | ~120 | ~73% [28] |

| Hâ‚‚O | 14 | 1,086 | 1,086 | ~250 | ~77% [15] |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | 1,159 | 1,159 | ~260 | ~78% [28] |

Step 3: Diagonalizing Circuit Construction

For each measurement group, construct a quantum circuit that simultaneously diagonalizes all observables in the group:

Qubit-Wise Commutativity Groups: For QWC groups, the diagonalization circuit consists only of single-qubit gates. For each qubit, if the Pauli operators across the group include non-Z operators, apply the appropriate basis rotation:

- X measurement: Apply H gate

- Y measurement: Apply S†followed by H gate

- Z measurement: No gate needed (already in computational basis)

Full Commutativity Groups: For fully commuting groups that don't satisfy QWC, construct a Clifford circuit ( U ) such that ( UPiU^\dagger ) is a diagonal Pauli string for all ( Pi ) in the group. This can be implemented using ( O(n^2/\log n) ) Clifford gates [16], though more efficient compilations exist for smaller groups.

( k )-Commutativity Groups: For ( k )-commuting groups, the diagonalization circuit has a block structure, with each block of size ( k ) diagonalized independently. This typically requires fewer entangling gates than full diagonalization while achieving better group consolidation than QWC.

The following diagram illustrates the circuit construction process for a QWC group:

Figure 2: Quantum circuit construction workflow for a qubit-wise commuting (QWC) group. After state preparation, compatibility analysis identifies simultaneously measurable observables, single-qubit rotations diagonalize the group, and measurement in the computational basis enables classical post-processing to extract individual expectation values.

Step 4: Quantum Execution and Shot Allocation

Execute the measurement circuits on quantum hardware or simulator:

Circuit Execution: For each measurement group, run the state preparation circuit followed by the diagonalization circuit, then measure in the computational basis.

Shot Allocation: Distribute the total measurement budget (shots) across groups optimally. Uniform allocation is simple but suboptimal. Variance-based shot allocation assigns more shots to groups with higher estimated variance, significantly reducing the total shots needed for a target precision [28]. For a total shot budget ( N ), allocate to group ( i ) proportionally to ( \frac{|ci|\sigmai}{\sumj |cj|\sigmaj} ), where ( \sigmai ) is the standard deviation of the measurement outcomes for group ( i ).

Iterative Refinement: For adaptive algorithms like ADAPT-VQE, reuse measurement outcomes from previous iterations when possible. Recent research shows that reusing Pauli measurement results from VQE optimization in subsequent gradient evaluations can reduce average shot usage to 32.29% compared to naïve approaches [28].

Step 5: Classical Post-Processing and Expectation Value Reconstruction