Introduction: The Secret Language of Shapes

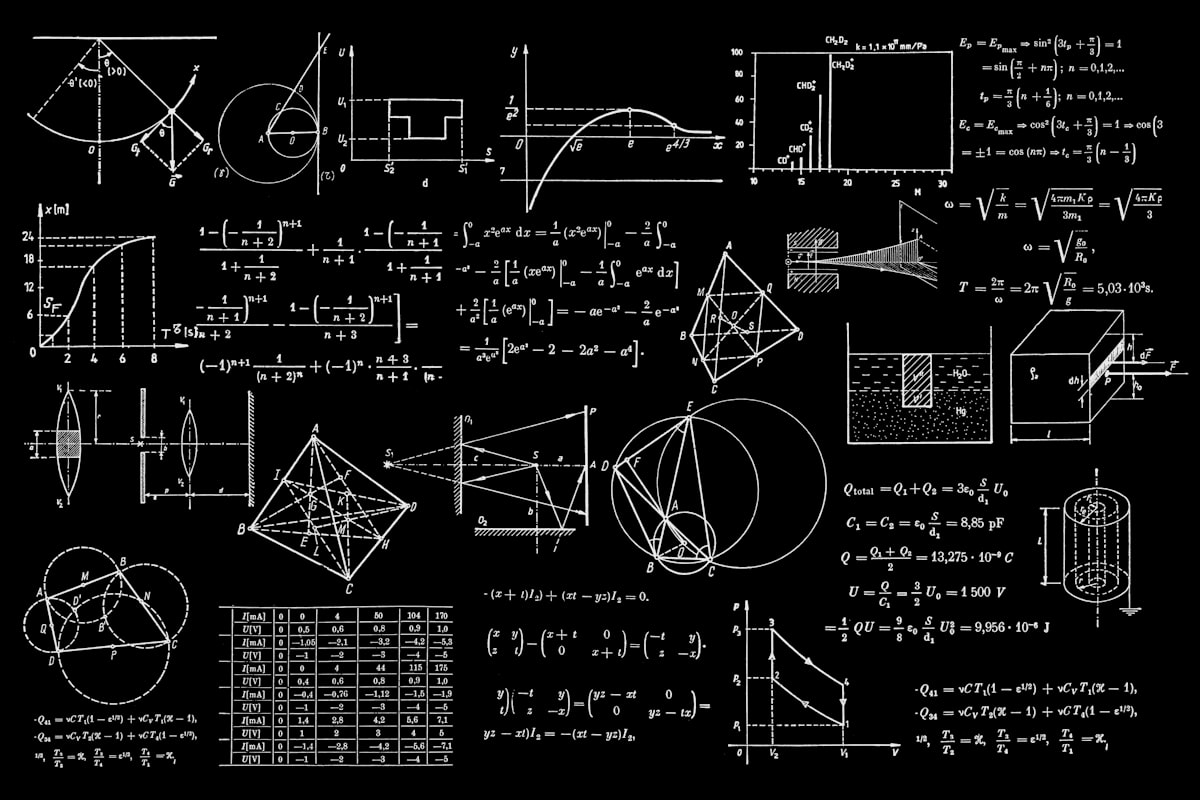

Imagine trying to understand a masterpiece painting while seeing only the colors without recognizing the forms—the curves, angles, and structures that give those colors meaning. This is what chemistry would be like without geometry. From the spiraling double helix of DNA to the soccer-ball-shaped carbon buckyballs, the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms determines everything from how medicines interact with our bodies to why some materials conduct electricity while others don't. Geometry isn't just about mathematical perfection; it's the very framework that gives matter its properties and function.

Recent breakthroughs have revealed that chemistry's geometric principles extend beyond simple molecular shapes to influence quantum behaviors and chemical reactions at the most fundamental level. The emerging field of positive geometry even suggests that strange mathematical shapes may help unify our understanding of everything from subatomic particles to the cosmos itself 6 . In this article, we'll explore how chemists use models—both physical and computational—to decode the geometric secrets of matter, and how this understanding is driving innovation in technology, medicine, and materials science.

Key Concepts and Theories: The Architecture of Matter

Atomic Geometry and Chemical Behavior

At the heart of chemical geometry lies a simple principle: atoms arrange themselves in ways that minimize energy while maximizing stability. This concept forms the basis of Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory, which predicts molecular shapes based on how electron pairs push away from each other.

These geometric arrangements determine molecular properties like polarity and reactivity, which in turn influence how substances behave in chemical reactions. The geometric concept of symmetry is particularly important, as it helps explain everything from how molecules interact with light to why certain crystals exhibit piezoelectric effects 7 .

Beyond Basic Shapes: Orbitals and Electron Behavior

While VSEPR theory explains basic molecular shapes, a more sophisticated model emerges when we consider atomic orbitals—the probability clouds where electrons are most likely to be found. These orbitals (s, p, d, and f) have characteristic shapes that determine how atoms bond and interact:

- s-orbitals: Spherical shapes that allow bonding in any direction

- p-orbitals: Dumbbell shapes that orient along specific axes (x, y, z)

- d and f-orbitals: Complex shapes that enable transition metals to form varied coordination compounds

When atoms bond, their orbitals combine and hybridize, creating new geometric arrangements that explain more complex molecular structures. This orbital geometry becomes particularly important in understanding transition metal complexes and aromatic compounds with their delocalized electron clouds 5 .

The Newest Frontier: Positive Geometry and Quantum Phenomena

Perhaps the most mind-bending development in chemical geometry comes from theoretical physics and mathematics. Researchers are exploring how positive geometry—a mathematical concept involving shapes with positive coordinates—might unify our understanding of particle physics and cosmology 6 . These strange new shapes, with names like "amplituhedron" and "cosmological polytopes," provide geometric representations of how particles interact during high-energy collisions and may even help explain the universe's origins.

"Positive geometry is still a young field, but it has the potential to significantly influence fundamental research in both physics and mathematics."

While highly theoretical, this work demonstrates how geometric concepts continue to revolutionize our understanding of the physical world.

Recent Discoveries: When Chemistry Creates Geometry

Orbital Frustration in Quantum Materials

In a groundbreaking August 2025 study published in Nature Physics, researchers from Columbia University unveiled a remarkable discovery: a two-dimensional material called Pd₅AlI₂ that exhibits what they call "frustration" of electron motion 1 . Unlike traditional frustrated systems where geometric arrangement of atoms creates conflict, this material achieves frustration through its underlying chemistry—specifically, the arrangement of electron orbitals.

"The lattice may be simple, but it's because of the orbitals that it becomes so interesting."

The material's orbitals combine into a checkerboard pattern that mimics the geometry of a Lieb lattice—a theoretical structure composed of squares that physicists had previously studied only in models. This orbital arrangement creates "flat bands"—electronic structures where electrons all share the same energy—which can lead to unusual quantum behaviors like superconductivity and exotic forms of magnetism.

What makes this discovery particularly exciting is that Pd₅AlI₂ is air-stable and can be peeled into atom-thin layers, making it more practical for future applications than previous fragile quantum materials. The research team is now exploring how to strain and manipulate this material to control its quantum properties, potentially paving the way for novel quantum technologies including better superconductors, rare-earth-free magnets, and ultra-sensitive quantum sensors 1 .

Predicting Protein Solubility Through Geometric Topology

In another intersection of geometry and chemistry, researchers developed TopoFormer—a novel computational model that combines geometric and topological approaches to predict protein solubility from 3D structural data 4 . Created in July 2025, this neural network model analyzes both the geometric arrangement of atoms and the overall topological features of protein structures to determine how soluble they will be—a critical factor for pharmaceutical production.

The researchers assembled two specialized datasets (3DProtSolDB and 3DProtSolDB-Expt) to train their model, which achieved state-of-the-art accuracy in predicting solubility. Perhaps most impressively, the model acquired key physical insights into solvation behavior without being explicitly programmed with these rules—it learned them from the geometric and topological data 4 .

In-Depth Look: The Pd₅AlI₂ Experiment

Methodology: How to Frustrate Electrons

The discovery of orbital frustration in Pd₅AlI₂ emerged from collaboration between chemistry and physics research groups at Columbia University. The experimental process unfolded in several key stages:

- Material Synthesis: Chemistry graduate student Christie Koay and postdoctoral researcher Daniel Chica synthesized the Pd₅AlI₂ crystal using solid-state reaction techniques 1 .

- Exfoliation: The team then used mechanical exfoliation to peel thin layers from the crystal down to a single atomic layer 1 .

- Structural Characterization: Using techniques like X-ray diffraction and scanning tunneling microscopy, the researchers confirmed the crystal structure 1 .

- Electronic Measurements: Devarakonda conducted precise measurements of the material's electronic properties using low-temperature transport experiments 1 .

- Theoretical Interpretation: Theoretical physicist Raquel Queiroz made the crucial connection between the experimental observations and the material's orbital chemistry 1 .

Results and Analysis: A New Paradigm for Frustration

The experiments revealed that Pd₅AlI₂ exhibits several remarkable electronic properties:

| Property | Value at 300K | Value at 2K |

|---|---|---|

| Electrical conductivity | 2.3 × 10⁵ S/m | 1.8 × 10⁶ S/m |

| Electron mobility | 420 cm²/V·s | 3,800 cm²/V·s |

| Flat band signature | Not observable | Clearly observable |

| Magnetic susceptibility | Weakly paramagnetic | Anomalous peak at 15K |

The most significant finding was the emergence of a flat band electronic structure at low temperatures, which forced electrons to occupy the same energy level—an inherently unstable situation that can lead to exotic quantum states 1 .

Comparison of Frustration Mechanisms

| Characteristic | Traditional Geometric Frustration | Orbital Frustration in Pd₅AlI₂ |

|---|---|---|

| Lattice structure | Triangular or square arrangements | Simple, non-frustrated lattice |

| Source of frustration | Atomic positions | Orbital orientations and interactions |

| Material examples | Spin ices, kagome lattices | Pd₅AlI₂ and related compounds |

| Tunability | Difficult to modify | Potentially tunable through chemistry |

| Air stability | Often unstable | Highly stable |

This flat band resulted not from the geometric arrangement of atoms but from the orbital chemistry—specifically, how the electron orbitals oriented and interacted with each other. Theoretical analysis confirmed that the orbitals were creating a checkerboard pattern that mimicked the geometry of a Lieb lattice, effectively creating geometric frustration through chemistry rather than atomic structure 1 .

The Scientist's Toolkit: Exploring Molecular Geometry

Research in chemical geometry relies on both physical models and advanced computational tools. Here are some key resources that scientists use to explore and understand the geometric aspects of chemistry:

Molecular Model Kits

Physical representations of molecules using balls (atoms) and sticks (bonds). Essential for understanding stereochemistry and molecular symmetry 5 .

X-ray Crystallography

Determines precise atomic positions in crystals. Crucial for mapping electron densities and bond lengths in molecular structures.

Quantum Chemistry Software

Computes electronic structure and molecular properties. Used for predicting reaction pathways and transition states 3 .

React-OT Machine Learning

Predicts transition state structures of chemical reactions. Enables designing more efficient chemical synthesis pathways 3 .

TopoFormer Neural Network

Combines geometry and topology to predict protein solubility. Valuable for pharmaceutical development and protein engineering 4 .

Angle-Resolved Photoemission Spectroscopy

Measures electronic band structures of materials. Essential for identifying flat bands in quantum materials 1 .

The resurgence of physical molecular models might surprise some in this digital age, but they remain valuable teaching tools and research aids. As one supplier notes: "Molecular models are not just for chemistry: Display, trophies, even organization theory" 5 . These physical representations help researchers and students develop intuitive understanding of molecular shapes that can be difficult to grasp from purely computational representations.

On the computational front, new machine learning approaches are revolutionizing how researchers work with molecular geometry. The React-OT model developed at MIT can predict transition states—the "point of no return" in chemical reactions—in less than a second with high accuracy 3 . This capability could dramatically accelerate the design of new chemical reactions for pharmaceuticals, materials, and energy technologies.

Similarly, geometric graph neural networks are advancing drug discovery by predicting reaction outcomes even when limited training data is available 8 . These AI systems can recognize patterns in molecular geometry that humans might miss, leading to more efficient optimization of potential drug compounds.

Conclusion: The Geometric Future of Chemical Innovation

The study of geometry in chemistry has evolved far beyond simply recognizing molecular shapes. We now understand that geometric principles operate at multiple levels—from the arrangement of atoms in space to the orientation of orbitals and even the mathematical shapes that describe fundamental physical processes.

This geometric perspective is yielding exciting innovations:

- New quantum materials like Pd₅AlI₂, where orbital geometry creates potentially useful quantum behaviors 1

- Advanced prediction tools that combine geometric and topological approaches to solve practical problems like protein solubility 4

- Faster reaction design through machine learning models that accurately predict transition states 3

- Theoretical unification of physical principles through positive geometry and other mathematical approaches 6

As research continues, scientists are increasingly adopting a multidisciplinary approach that combines chemistry, physics, mathematics, and computer science to explore geometric principles. The integration of AI methods is particularly promising, as these systems can detect subtle geometric patterns that might escape human observation.

"We've found an entirely new way to think about frustration, one that combines how chemists think about chemical bonds with how physicists think about crystal lattices."

The geometric perspective reminds us that sometimes, to understand the deepest secrets of matter, we need to step back and appreciate the shapes—from the elegant symmetry of a snowflake to the mysterious mathematical forms that may underpin all physical reality.

Acknowledgments: The author thanks the researchers whose work is cited here for pushing the boundaries of our geometric understanding of chemistry. Their interdisciplinary approach exemplifies how collaboration across traditional scientific boundaries can yield remarkable insights.