Understanding and Overcoming Barren Plateaus in Variational Quantum Algorithms: A Guide for Biomedical Research

Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) offer a promising paradigm for tackling complex problems in drug development and biomedical research on near-term quantum devices.

Understanding and Overcoming Barren Plateaus in Variational Quantum Algorithms: A Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

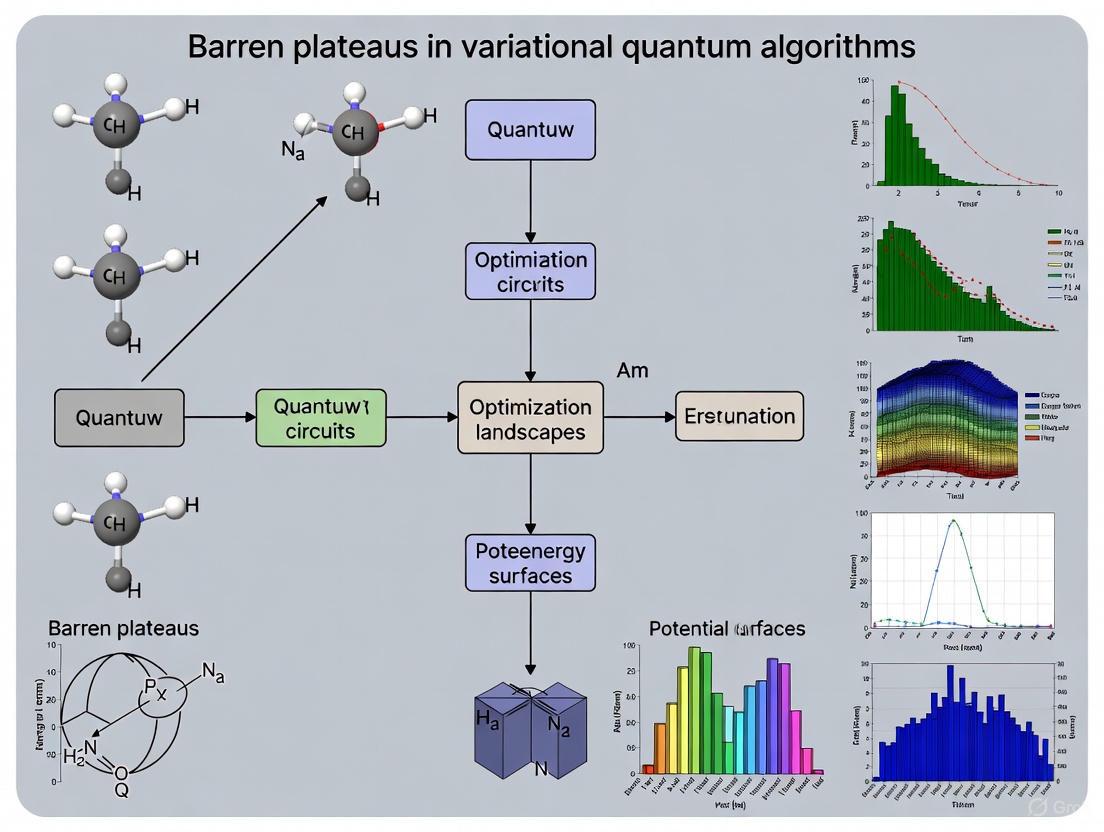

Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) offer a promising paradigm for tackling complex problems in drug development and biomedical research on near-term quantum devices. However, their potential is hindered by the Barren Plateau (BP) phenomenon, where optimization landscapes become exponentially flat, rendering training impossible. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and scientists, exploring the foundational causes of BPs, from the curse of dimensionality to hardware noise. It details methodological approaches for implementing VQAs, systematic troubleshooting and mitigation strategies to overcome trainability issues, and a critical validation framework for assessing quantum advantage against classical simulability. The insights herein are crucial for developing robust, scalable quantum computing applications in clinical and pharmaceutical settings.

What Are Barren Plateaus? Diagnosing the Core Challenge in Quantum Optimization

The advent of variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) promised to leverage near-term quantum devices for practical computational tasks, notably in simulating molecular systems for drug development. However, the phenomenon of barren plateaus (BPs) has emerged as a fundamental obstacle, characterized by exponentially vanishing gradients that preclude the training of these algorithms. This whitepaper delineates the BP problem through the powerful analogy of an optimization landscape, providing a technical guide to its causes, characteristics, and the current research aimed at its mitigation.

The Optimization Landscape of Variational Quantum Algorithms

A VQA optimizes a parameterized quantum circuit (PQC) by minimizing a cost function, C(θ), analogous to the energy of a molecular system. The parameters θ define a high-dimensional landscape. A fertile landscape features steep slopes and clear minima, guiding optimization. A BP, in contrast, is a vast, flat region where the gradient ∇θC(θ) vanishes exponentially with the number of qubits, n.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Optimization Landscapes

| Feature | Fertile Landscape | Barren Plateau |

|---|---|---|

| Average Gradient Magnitude | O(1/poly(n)) | O(exp(-n)) |

| Variance of Cost Function | O(1) | O(exp(-n)) |

| Optimization Feasibility | Efficiently trainable | Untrainable for large n |

| Visual Analogy | Rugged mountains with valleys | Featureless, flat desert |

The Genesis of Barren Plateaus

BPs are not a singular phenomenon but arise from specific conditions within the circuit and cost function.

2.1. Deep, Random Quantum Circuits The foundational work of McClean et al. (2018) demonstrated that for sufficiently deep, randomly initialized PQCs, the probability of encountering a non-zero gradient is exponentially small. This is a consequence of the unitary group's Haar measure, where the circuit becomes an approximate unitary 2-design, leading to cost function concentration around its average value.

2.2. Global Cost Functions Cost functions that measure correlations between distant qubits or compare the output state to a global target are highly susceptible to BPs. The locality of the noise in the gradient estimation is incompatible with the global nature of the cost.

2.3. Noise-Induced Barren Plateaus Recent research has shown that local, non-unital noise channels in hardware can themselves induce BPs, even in shallow circuits. The noise randomizes the state, effectively erasing the coherent information needed for training.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Barren Plateaus

Protocol 1: Gradient Magnitude Scaling Analysis

- Objective: Empirically verify the presence of a BP by measuring how the gradient magnitude scales with qubit count.

- Methodology:

- Circuit Setup: Choose a PQC ansatz (e.g., Hardware Efficient, Tensor Network).

- Parameter Initialization: Initialize parameters θ from a uniform random distribution.

- Gradient Calculation: For multiple random parameter instances, compute the gradient of the cost function with respect to a target parameter, θᵢ, using the parameter-shift rule: ∂C/∂θᵢ = [C(θᵢ + π/2) - C(θᵢ - π/2)] / 2.

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate the statistical mean (|⟨∂C/∂θᵢ⟩|) and variance (Var[∂C/∂θᵢ]) over the random instances.

- Scaling: Repeat steps 1-4 for increasing numbers of qubits (n). Plot the average gradient magnitude versus n. An exponential decay is indicative of a BP.

Protocol 2: Cost Function Concentration Measurement

- Objective: Demonstrate that the cost function concentrates around its mean value for large systems.

- Methodology:

- Ensemble Creation: Generate a large ensemble (e.g., 1000) of random circuit parameter vectors {θ}.

- Cost Evaluation: For each vector, execute the quantum circuit and estimate the cost function C(θ).

- Distribution Analysis: Plot a histogram of the calculated cost values.

- Variance Scaling: Calculate the variance of the cost function distribution, Var[C(θ)], and analyze its scaling with the number of qubits, n. Exponential decay of variance confirms a BP.

Visualizing the Barren Plateau Phenomenon

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for Barren Plateau Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Parameterized Quantum Circuit (PQC) Ansatz | The quantum program whose parameters are optimized. Different ansatzes (e.g., hardware-efficient, QAOA) have varying susceptibilities to BPs. |

| Cost Function | The objective to be minimized (e.g., molecular energy, classification error). Defining local instead of global cost functions is a key mitigation strategy. |

| Classical Optimizer | The algorithm (e.g., Adam, SPSA) that updates PQC parameters based on gradient or function evaluations. Its performance degrades severely on BPs. |

| Quantum Simulator / Hardware | The platform for executing the PQC and estimating the cost function. Used to measure gradient statistics and validate theoretical predictions. |

| Gradient Estimation Tool | A method like the parameter-shift rule or linear combination of unitaries to compute the analytical gradient, which is central to BP analysis. |

| Bis(2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl) succinate | Bis(2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl) succinate, CAS:30364-60-4, MF:C12H12N2O8, MW:312.23 g/mol |

| Temocillin | Temocillin|C16H18N2O7S2|For Research |

Mitigation Strategies and Future Directions

The research community is actively developing strategies to navigate BPs, including:

- Identity Block Initialization: Initializing circuit parameters to construct identity gates, breaking the randomness that leads to BPs.

- Local Cost Functions: Designing cost functions that are sums of local observables, which have been proven to avoid BPs for shallow circuits.

- Pre-training with Classical Surrogates: Using classical machine learning models to find a promising region in the parameter space before quantum optimization.

- Layerwise Training: Training the circuit one layer at a time to prevent the system from entering a BP prematurely.

Within the broader thesis of VQA research, the barren plateau represents a critical challenge rooted in the fundamental geometry of high-dimensional quantum spaces. The optimization landscape analogy provides an intuitive yet rigorous framework for understanding this phenomenon. For researchers in drug development relying on VQAs for molecular simulation, recognizing and mitigating BPs is not merely an academic exercise but a prerequisite for achieving quantum utility. The ongoing development of strategic ansatzes, cost functions, and training protocols offers a path forward through this computationally barren terrain.

The curse of dimensionality describes a set of phenomena that arise when analyzing and organizing data in high-dimensional spaces, which do not occur in low-dimensional settings like our everyday three-dimensional physical space [1]. This concept, coined by Richard E. Bellman, fundamentally represents the dramatic increase in problem complexity and resource requirements as dimensionality grows [1]. When framed within variational quantum algorithm (VQA) research, the curse of dimensionality manifests as barren plateaus—regions in the optimization landscape where gradients vanish exponentially with increasing qubit count, effectively stalling training and preventing quantum advantage [2] [3].

This technical guide explores the intrinsic relationship between the curse of dimensionality and expressivity in quantum circuit ansätze, examining how their interplay creates fundamental bottlenecks in VQA performance. We dissect the mathematical foundations of these phenomena, present experimental evidence of their effects across different quantum algorithms, and synthesize current mitigation strategies that offer promising paths forward for researchers, particularly those in computationally intensive fields like drug development where quantum computing promises potential breakthroughs.

Mathematical Foundations of the Dimensionality Problem

The Curse of Dimensionality in Classical and Quantum Contexts

In classical machine learning, the curse of dimensionality presents several specific challenges that directly parallel issues in quantum computing:

Data Sparsity: As dimensionality increases, the volume of space grows exponentially, causing available data to become sparse and dissimilar [1]. In high-dimensional space, "all objects appear to be sparse and dissimilar in many ways," preventing common data organization strategies from being efficient [1].

Exponential Data Requirements: To obtain reliable results, "the amount of data needed often grows exponentially with the dimensionality" [1]. For example, while 100 evenly-spaced points suffice to sample a unit interval with no more than 0.01 distance between points, sampling a 10-dimensional unit hypercube with equivalent spacing would require 10²Ⱐsample points [1].

Distance Function Degradation: In high dimensions, Euclidean distance measures become less meaningful as "there is little difference in the distances between different pairs of points" [1]. The ratio of hypersphere volume to hypercube volume approaches zero as dimensionality increases, and the distance between center and corners grows as (r\sqrt{d}) [1].

Expressivity and Barren Plateaus in Quantum Systems

In variational quantum algorithms, parameterized quantum circuits (U(\theta)) are optimized to minimize cost functions, typically the expectation value of a Hamiltonian: (E(\theta) = \langle \psi(\theta) | H | \psi(\theta) \rangle) [4]. The expressivity of an ansatz refers to the breadth of quantum states it can represent, with highly expressive ansätze potentially capturing more complex solutions but also being more prone to barren plateaus [5] [3].

Barren plateaus emerge when the gradient of the cost function vanishes exponentially with increasing qubit count, making optimization practically impossible [3]. Two primary mechanisms drive this phenomenon:

- Expressivity-Induced Barren Plateaus: Highly expressive, random parameterized quantum circuits exhibit gradients that vanish exponentially with qubit count [3].

- Noise-Induced Barren Plateaus (NIBPs): Quantum hardware noise causes training landscapes to flatten, with the gradient vanishing exponentially in both qubit count and circuit depth [3].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Barren Plateau Types

| Feature | Expressivity-Induced BP | Noise-Induced BP (NIBP) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cause | High ansatz expressivity, random parameter initialization [3] | Hardware noise accumulating with circuit depth [3] |

| Gradient Scaling | Vanishes exponentially with qubit count n [3] | Vanishes exponentially with circuit depth L and n [3] |

| Dependence | Linked to ansatz design and parameter initialization [4] | Scales as (2^{-\kappa}) with (\kappa = -L\log_2(q)) for noise parameter q [3] |

| Potential Mitigations | Local cost functions, correlated parameters [3] | Circuit depth reduction, error mitigation [3] |

Experimental Evidence and Analytical Proofs

Quantum Kernel Methods and High-Dimensional Data

Quantum kernel methods (QKMs) leverage quantum computers to map input data into high-dimensional Hilbert spaces, creating kernel functions (k(xi, xj) = |\langle \phi(xi)|\phi(xj)\rangle|^2) that could be challenging to compute classically [6]. Experimental implementation on Google's Sycamore processor demonstrated classification of 67-dimensional supernova data using 17 qubits, achieving test accuracy comparable to noiseless simulation [6].

A critical challenge identified was maintaining kernel matrix elements large enough to resolve above statistical error, as the "likelihood of large relative statistical error grows with decreasing magnitude" of kernel values [6]. This directly relates to the curse of dimensionality, where high-dimensional projections can map data points too far apart, losing information about class relationships [6].

The Barren Plateau Phenomenon in VQEs

Variational Quantum Eigensolvers (VQEs) face significant challenges due to barren plateaus, particularly for problems involving strongly correlated systems [5]. Key limitations include:

Expressivity Limits: Fixed, single-reference ansätze like Unitary Coupled Cluster with Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) fail to capture strong correlation or multi-reference character essential for problems like molecular bond breaking [5].

Optimization Difficulties: "Barren plateaus and rugged landscapes stall parameter updates, particularly as the number of variational parameters increases" [5].

Resource Overhead: Achieving chemical accuracy often requires large circuits, extensive measurements, and long coherence times, straining current NISQ hardware [5].

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of Barren Plateaus on VQE Performance

| Metric | Impact of Barren Plateaus | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Gradient Magnitude | Vanishes exponentially with qubit count [3] | Proof for local Pauli noise with depth linear in qubit count [3] |

| Training Samples | Required shots grow exponentially to resolve gradients [3] | Resource burden prevents quantum advantage [3] |

| Circuit Depth | NIBPs worsen with increasing depth [3] | Superconducting hardware implementations show significant impact [3] |

| Convergence Reliability | Random initialization likely lands in barren regions [4] | ADAPT-VQE provides better initialization [4] |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Barren Plateaus in VQEs

To empirically characterize barren plateaus in variational quantum algorithms, researchers can implement the following protocol:

Circuit Preparation: Implement a parameterized quantum circuit (U(\theta)) with the chosen ansatz (e.g., Hardware Efficient, UCCSD, or QAOA) on the target quantum processor or simulator [3].

Parameter Initialization: Randomly sample parameter vectors (\theta) from a uniform distribution across the parameter space. For comprehensive analysis, include both random initialization and problem-informed initialization (e.g., Hartree-Fock reference for quantum chemistry problems) [4].

Gradient Measurement: For each parameter configuration, estimate the gradient of the cost function (C(\theta) = \langle 0| U^\dagger(\theta) H U(\theta) |0\rangle) with respect to each parameter using the parameter-shift rule or finite differences: [ \frac{\partial C}{\partial \thetai} \approx \frac{C(\thetai + \delta) - C(\theta_i - \delta)}{2\delta} ]

Statistical Analysis: Compute the variance of the gradient components across different parameter initializations: (\text{Var}[\partial{\thetai} C]). Exponential decay of this variance with qubit count indicates a barren plateau [3].

Noise Characterization: For NIBP analysis, repeat measurements under different noise conditions and error mitigation techniques to isolate the noise contribution to gradient vanishing [3].

This protocol was implemented in studies of the Quantum Alternating Operator Ansatz (QAOA) for MaxCut problems, clearly demonstrating the NIBP phenomenon [3].

Mitigation Strategies and Algorithmic Solutions

Adaptive and Problem-Tailored Ansätze

Adaptive VQE approaches like ADAPT-VQE dynamically construct ansätze to avoid barren plateaus [4]. Rather than using fixed ansätze, ADAPT-VQE grows the circuit iteratively by selecting operators from a pool based on gradient criteria [4]. This approach provides two key advantages:

Improved Initialization: "It provides an initialization strategy that can yield solutions with over an order of magnitude smaller error compared to random initialization" [4].

Barren Plateau Avoidance: "It should not suffer optimization problems due to barren plateaus and random initialization" because it avoids exploring problematic regions of the parameter landscape [4].

Even when ADAPT-VQE converges to a local minimum, it can "burrow" toward the exact solution by adding more operators, which preferentially deepens the occupied trap [4].

Cyclic Variational Framework with Measurement Feedback

The Cyclic Variational Quantum Eigensolver (CVQE) introduces a hardware-efficient framework that escapes barren plateaus through a distinctive "staircase descent" pattern [5]. The methodology works through:

Measurement-Driven Feedback: After each optimization cycle, Slater determinants with high sampling probability are incorporated into the reference superposition [5].

Fixed Entangling Structure: Unlike approaches that expand the ansatz circuit, CVQE maintains a fixed entangler (e.g., single-layer UCCSD) while adaptively growing the reference state [5].

Staircase Descent: Extended energy plateaus are punctuated by sharp downward steps when new determinants are incorporated, creating fresh optimization directions [5].

This approach "systematically enlarges the variational space in the most promising directions without manual ansatz or operator pool design, while preserving compile-once, hardware-friendly circuits" [5].

CVQE Workflow: Cyclic variational quantum eigensolver with measurement feedback [5]

Quantum Kernel Design and Expressivity Control

Quantum kernel methods face careful trade-offs between expressivity and trainability [6] [7]. Research on breast cancer subtype classification using quantum kernels demonstrated that:

Expressivity Modulation: "Less expressive encodings showed a higher resilience to noise, indicating that the computational pipeline can be reliably implemented on NISQ devices" [7].

Data Efficiency: Quantum kernels achieved "comparable clustering results with classical methods while using fewer data points" [7].

Granular Stratification: Quantum approaches enabled better fitting of data with higher cluster counts, suggesting enhanced capability to capture complex patterns in multi-omics data [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Experimental Components for Barren Plateau Research

| Research Component | Function & Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz | Parameterized circuit respecting device connectivity; reduces implementation overhead [6] | Google Sycamore processor with 17 qubits for quantum kernel methods [6] |

| Adaptive Operator Pool | Dynamic ansatz growth; avoids barren plateaus by constructive circuit building [4] | ADAPT-VQE with UCCSD pool for molecular ground states [4] |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Counteracts noise-induced barren plateaus; improves signal-to-noise in gradient measurements [6] [3] | Zero-noise extrapolation, probabilistic error cancellation [6] |

| Cyclic Optimizer (CAD) | Momentum-based optimization with periodic resets; adapts to changing landscape [5] | CVQE with Cyclic Adamax optimizer for staircase descent pattern [5] |

| Quantum Kernel Feature Map | Encodes classical data into quantum state; controls expressivity for specific datasets [6] [7] | Parameterized local rotations for 67-dimensional supernova data [6] |

| Girinimbine | Girinimbine|Carbazole Alkaloid|For Research Use | |

| 3-Hydroxy-3-methyl-2-oxopentanoic acid | 3-Hydroxy-3-methyl-2-oxopentanoic Acid|C6H10O4 | Research-use 3-Hydroxy-3-methyl-2-oxopentanoic acid (C6H10O4) for studying branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The intricate relationship between the curse of dimensionality and expressivity in variational quantum algorithms presents both a fundamental challenge and opportunity for quantum computing research. As the field progresses, several promising research directions emerge:

First, the development of problem-inspired ansätze that incorporate domain knowledge—whether from quantum chemistry, optimization, or machine learning—offers a path to constraining expressivity to relevant subspaces, potentially avoiding the exponential scaling of barren plateaus [4]. Second, advanced initialization strategies that move beyond random parameter selection show considerable promise in navigating the optimization landscape more effectively [5] [4].

Third, co-design approaches that jointly optimize algorithmic structure and hardware implementation may help balance expressivity requirements with practical device constraints [6]. Finally, the exploration of quantum-specific mitigation techniques like the cyclic variational framework with measurement feedback suggests that fundamentally quantum mechanical solutions may ultimately overcome these classically-inspired limitations [5].

For researchers in drug development and related fields, these advances in understanding and mitigating barren plateaus are particularly significant. The ability to reliably simulate molecular systems with strong electron correlation—essential for accurate prediction of drug-receptor interactions—depends on overcoming these optimization challenges. As variational quantum algorithms continue to mature, they offer the potential to transform computational approaches to drug discovery, provided the fundamental issues of dimensionality and expressivity can be effectively managed through the integrated strategies outlined in this technical guide.

In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, hardware noise presents a formidable challenge to the practical implementation of quantum algorithms. Particularly for Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs)—a leading candidate for achieving quantum advantage—the presence of noise can induce vanishing gradients during training, a phenomenon known as Noise-Induced Barren Plateaus (NIBPs). Understanding the distinct roles played by different categories of noise, specifically unital and non-unital noise models, is crucial for diagnosing these scalability issues and developing effective mitigation strategies. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of how these noise types impact VQA performance, framed within the critical context of barren plateau research.

Theoretical Foundations: Unital vs. Non-Unital Noise

Mathematical Definitions and Properties

In quantum computing, the evolution of a state Ï under noise is described by a quantum channel, a completely positive, trace-preserving (CPTP) map, often expressed in the Kraus operator sum representation: ε(Ï) = ∑ₖ Eâ‚– Ï Eₖ†, where the Kraus operators Eâ‚– satisfy ∑ₖ Eₖ†Eâ‚– = I [8] [9].

The critical distinction between unital and non-unital noise lies in their action on the identity operator:

- Unital Noise: A quantum channel ε is unital if it preserves the identity operator: ε(I) = I. This implies that the maximally mixed state (I/d) is a fixed point of the channel. For the Kraus operators, this is equivalent to satisfying ∑ₖ Eₖ Eₖ†= I in addition to the trace-preserving condition [9].

- Non-Unital Noise: A channel is non-unital if ε(I) ≠I. These channels do not preserve the maximally mixed state and typically drive the system towards a specific state in the Hilbert space [9] [10].

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Unital and Non-Unital Noise

| Property | Unital Noise | Non-Unital Noise | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | ε(I) = I | ε(I) ≠I | |

| Maximally Mixed State | Fixed point | Not a fixed point | |

| Average Purity | Can decrease or increase | Can decrease or increase | |

| Asymptotic State | Maximally mixed state (for some) | Preferential pure state (e.g., | 0⟩) |

| Entropy | Can increase entropy | Can decrease entropy |

Common Physical Noise Models

The following diagram illustrates the classification of common noise models encountered in quantum hardware:

Figure 1: A classification of common quantum noise models.

Unital Noise Examples:

- Depolarizing Noise: Represents a complete randomization of the quantum state with probability p, replacing the state with the maximally mixed state. Its Kraus operators are E₀ = √(1-p) I, E₠= √(p/3) X, E₂ = √(p/3) Y, E₃ = √(p/3) Z [8] [10].

- Dephasing Noise (Phase Damping): Causes loss of phase coherence without energy loss. It is a dominant noise source in many physical systems and is characterized by the Tâ‚‚ coherence time [10] [11].

Non-Unital Noise Examples:

- Amplitude Damping: Models the energy dissipation of a qubit, asymptotically driving it from the excited |1⟩ state to the ground |0⟩ state. This is a primary model for T₠relaxation processes [10] [12].

- Thermal Relaxation: A generalized amplitude damping channel that models energy exchange with a thermal environment at finite temperature, not necessarily the ground state [13].

The Barren Plateau Landscape and Noise-Induced Effects

Barren Plateaus: From Random Initialization to Noise-Induced

A Barren Plateau (BP) is characterized by the exponential decay of the cost function gradient's magnitude with respect to the number of qubits. This makes training VQAs intractable. Initially, BPs were linked to the random initialization of parameters in deep, unstructured ansatzes [3] [14].

Noise-Induced Barren Plateaus (NIBPs) represent a distinct, more pernicious phenomenon. Here, it is the hardware noise itself—not the parameter initialization—that causes the gradient to vanish. Rigorous studies have proven that for local Pauli noise, the gradient vanishes exponentially in the number of qubits n if the ansatz depth L grows linearly with n [3] [14] [15]. The mechanism behind an NIBP is the concentration of the output state of the noisy quantum circuit towards a fixed state. For unital noise, this is typically the maximally mixed state, which contains no information about the variational parameters, leading to a flat landscape [3].

Differential Impact of Unital vs. Non-Unital Noise

Recent research has delineated the distinct impacts of these noise classes on VQA trainability.

Unital Noise and NIBPs: Unital noise is a primary driver of NIBPs. As the circuit depth increases, the cumulative effect of unital noise channels drives the quantum state toward the maximally mixed state. The gradient norm upper bound decays as ∼ q^L, where q < 1 is a noise parameter and L is the circuit depth. For L ∠n, this translates to an exponential decay in n [3] [14] [15].

Non-Unital Noise and NILSs: The behavior of non-unital, HS-contractive noise (like amplitude damping) is more nuanced. While it can also lead to trainability issues, it does not always induce a barren plateau in the same way. Instead, it can give rise to a Noise-Induced Limit Set (NILS). Here, the cost function does not concentrate at a single value (like the maximally mixed state's energy) but rather converges to a set of limiting values determined by the fixed points of the non-unital noise process, which is not necessarily the maximally mixed state [15].

Table 2: Comparative Impact on VQA Trainability

| Feature | Unital Noise (e.g., Depolarizing) | Non-Unital Noise (e.g., Amplitude Damping) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Threat | Noise-Induced Barren Plateau (NIBP) | Noise-Induced Limit Set (NILS) & NIBP | |

| Asymptotic State | Maximally Mixed State | Preferential Pure State (e.g., | 0⟩) |

| Gradient Scaling | Vanishes exponentially in n and L | Can vanish exponentially, but not guaranteed for all types [15] | |

| Effect on Entropy | Increases, erasing information | Can decrease, driving towards a pure state | |

| Path to Mitigation | Error mitigation, shallow circuits | Leveraging noise as a feature, dynamical decoupling |

Experimental Protocols and Empirical Evidence

Protocol for Quantifying NIBPs

To empirically verify the presence and severity of an NIBP, researchers can follow this protocol:

- Circuit Selection: Choose a VQA ansatz, such as the Hardware-Efficient Ansatz or the Quantum Alternating Operator Ansatz (QAOA) [3].

- Noise Injection: Simulate the circuit using a density matrix simulator (e.g., Amazon Braket's DM1) [8]. Introduce a specific noise model (unital or non-unital) with a tunable error probability p after each gate.

- Gradient Calculation: For a randomly selected parameter θᵢ, compute the partial derivative of the cost function, ∂C/∂θᵢ, using a method like the parameter-shift rule, extended for noisy circuits [15].

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate the expectation value of the gradient magnitude, E[|∂C/∂θᵢ|], over many random parameter initializations.

- Scaling Analysis: Plot E[|∂C/∂θᵢ|] as a function of the number of qubits n (for a fixed depth-to-qubit ratio) or the circuit depth L. An exponential decay confirmed by a linear fit on a log-linear plot is indicative of a barren plateau.

The following workflow visualizes this experimental process:

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for characterizing NIBPs.

Key Findings from Literature

- Unital Noise Inevitably Causes NIBPs: Studies have consistently shown that under unital noise, the gradient vanishes exponentially with circuit depth and qubit count. For example, a 2021 study proved that for a generic ansatz with local Pauli noise, the gradient upper bound is ~2^(-κ) with κ = -L log₂(q), establishing the NIBP phenomenon [3] [14].

- Non-Unital Noise Can Be Beneficial: Counterintuitively, non-unital noise can sometimes enhance performance in specific quantum machine learning algorithms. In Quantum Reservoir Computing (QRC), amplitude damping noise has been shown to improve performance on tasks like predicting the excited energy of molecules, unlike depolarizing or phase damping noise [10] [12]. The non-unitality provides a "fading memory" crucial for processing temporal data.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Resources for Noise and NIBP Research

| Tool / Resource | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Density Matrix Simulator | Simulates mixed quantum states, enabling realistic noise modeling. | Amazon Braket DM1 [8] to simulate amplitude damping channels. |

| Noise Model Libraries | Predefined quantum channels (Kraus operators) for common noise types. | Injecting depolarizing or phase damping noise into a VQA circuit [8]. |

| Parameter-Shift Rule | A method for exact gradient calculation on quantum hardware, extendable to noisy circuits. | Computing ∂C/∂θᵢ for a VQA cost function in the presence of noise [15]. |

| Quantum Process Tomography | Full experimental characterization of a quantum channel acting on a small system. | Extracting the exact Kraus operators of a noisy gate on a real processor [13]. |

| Randomized Benchmarking | Efficiently estimates the average fidelity of a set of quantum gates. | Characterizing the overall error rate p of a quantum device [13]. |

| Eseramine | Eseramine, CAS:6091-57-2, MF:C16H22N4O3, MW:318.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 20-Deoxysalinomycin | 20-Deoxysalinomycin|For Research Use | 20-Deoxysalinomycin for research into cancer therapeutics and trypanocidal mechanisms. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The dichotomy between unital and non-unital noise models is fundamental to understanding the scalability of VQAs in the NISQ era. Unital noise presents a clear and proven path to NIBPs, fundamentally limiting the trainability of deep quantum circuits. In contrast, non-unital noise, while still a source of error and potential NIBPs, exhibits a richer and more complex behavior, sometimes even being harnessed as a computational resource. Future research must continue to refine our understanding of NILSs under non-unital noise and develop noise-aware ansatzes and error mitigation strategies tailored to the specific noise profiles of quantum hardware. Overcoming the challenge of NIBPs is not merely a technical hurdle but a prerequisite for achieving practical quantum advantage with variational algorithms.

Barren Plateaus (BPs) represent one of the most significant obstacles to the practical deployment of variational quantum algorithms (VQAs). A BP is a phenomenon where the gradient of the cost function used to train a parameterized quantum circuit (PQC) vanishes exponentially with the number of qubits, rendering optimization practically impossible [16] [17]. The term describes an exponentially flat landscape where the probability of obtaining a non-zero gradient is vanishingly small, causing classical optimizers to stagnate [2].

The susceptibility of a variational quantum algorithm to BPs is not arbitrary; it is profoundly influenced by the design of its ansatz—the parameterized quantum circuit whose structure defines the search space for the solution. This review systematically analyzes the specific architectural features of ansätze that correlate with high BP susceptibility, providing a guide for researchers, particularly in fields like drug development where VQAs are applied to molecular simulation, to make informed design choices that enhance trainability.

Core Mechanisms Linking Ansatz Design to Barren Plateaus

The emergence of a Barren Plateau is fundamentally tied to the expressibility and entanglement properties of an ansatz. When a circuit is too expressive, it can act as a random circuit, leading to the cost function concentration that causes gradients to vanish [18].

The Haar Measure and Unitary t-Designs

A key theoretical concept is the Haar measure, which describes a uniform distribution over unitary matrices. An ansatz that forms a unitary 2-design mimics the Haar measure up to its second moment, a property that has been proven to lead to BPs [16] [18]. For an ansatz to be a t-design, its ensemble of unitaries {p_i, V_i} must satisfy:

where μ(U) is the Haar measure [18]. When this condition is met for t=2, the variance of the gradient vanishes exponentially.

Entanglement and Trainability

Excessive entanglement between visible and hidden units in a circuit can also hinder learning capacity and contribute to BPs [18] [19]. The Lie algebraic theory connecting expressibility, state entanglement, and observable non-locality provides a precise characterization of when BPs emerge [19].

Table 1: Key Mechanisms Leading to Barren Plateaus in Ansätze

| Mechanism | Description | Impact on Gradient |

|---|---|---|

| Unitary 2-Design | Ansatz approximates the properties of Haar-random unitaries. | Variance of gradient decays exponentially with qubit count [16]. |

| Global Cost Functions | Cost function depends on measurements across many qubits. | Induces BP independently of ansatz depth due to shot noise [20]. |

| Excessive Entanglement | High entanglement between circuit subsystems. | Scrambles information and leads to gradient vanishing [18]. |

| Hardware Noise | Realistic noise in NISQ devices (e.g., depolarizing noise). | Can exponentially concentrate the cost function [18]. |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosing Barren Plateaus

To determine an ansatz's susceptibility to BPs, specific experimental protocols are employed to measure gradient statistics and cost function landscapes.

Gradient Variance Measurement

The primary method for diagnosing a BP is to statistically analyze the variance of the cost function gradient.

- Protocol: For a given ansatz

U(θ)with parametersθ, initializes parameters randomly from a uniform distribution. The gradient with respect to each parameterθ_kis computed using the parameter-shift rule [16]. The empirical variance of these gradients across many random parameter initializations is then calculated. - BP Identification: A BP is identified if the variance

Var[∂_k C]scales asO(1/2^n)orO(1/σ^n)for someσ > 1, wherenis the number of qubits [21] [18]. This exponential decay is the hallmark of a BP.

Statistical Analysis of Loss Landscapes

A statistical approach can classify BPs into different types, offering a more nuanced diagnosis [21].

- Everywhere-Flat BPs: The entire landscape is uniformly flat, making optimization most difficult. This is commonly observed in hardware-efficient and random Pauli ansätze.

- Localized-Dip/Gorge BPs: The landscape is mostly flat but contains a small region (a dip or gorge) where the gradient is large. While theoretically possible, these are less commonly found in practice for standard VQE ansätze [21].

Expressibility and Entanglement Measures

Quantitative metrics help predict BP susceptibility without full gradient analysis.

- Expressibility: Measures how well the ansatz can explore the Hilbert space. It can be quantified by comparing the distribution of states generated by the ansatz to the Haar measure [18]. Higher expressibility often correlates with higher BP risk.

- Entanglement Entropy: Measures the amount of entanglement generated by the ansatz. Sudden changes in entropy scaling can signal BP regions.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing an ansatz's susceptibility to Barren Plateaus.

High-Risk Ansatz Architectures

Research has identified several ansatz architectures that are particularly prone to BPs.

Hardware-Efficient Ansätze

Hardware-Efficient Ansätze (HEA) are constructed from gates native to a specific quantum processor to minimize depth and reduce noise. Despite this practical advantage, they are highly susceptible to BPs.

- Architecture: Typically composed of alternating layers of single-qubit rotation gates (e.g.,

R_x,R_y,R_z) and blocks of entangling gates (e.g.,CNOTorCZ) [16] [18]. - BP Susceptibility: Even at shallow depths, these circuits can quickly approximate 2-designs and exhibit BPs as the number of qubits increases. Numerical studies have shown that HEAs with random Pauli entanglers exhibit "everywhere-flat" BPs, making optimization exceptionally difficult [21].

Unstructured Random Circuits

Any ansatz that is sufficiently random and lacks problem-specific inductive bias is a prime candidate for BPs.

- Architecture: Circuits where the choice and arrangement of gates are random. This includes the Random Parameterized Quantum Circuits (RPQCs) studied in the original BP paper [16].

- BP Susceptibility: These circuits rapidly converge to unitary 2-designs. The probability that the gradient along any direction is non-zero to a fixed precision is exponentially small in the number of qubits [16].

Deep Alternating Ansätze

While depth is not the sole factor, it significantly contributes to BP formation in certain architectures.

- Architecture: Ansätze with a large number of layers

L, where each layer contains parameterized gates and entanglers. - BP Susceptibility: As depth increases, the circuit becomes more expressive. For a wide range of architectures, there exists a critical depth

L*beyond which the circuit becomes a 2-design and BPs are unavoidable [18]. For example, modifying a standard PQC for thermal-state preparation revealed that the original ansatz suffered from severe gradient vanishing at up to 2400 layers and 100 qubits, whereas the modified version did not [22].

Table 2: Summary of High-Risk Ansatz Architectures and Their Properties

| Ansatz Type | Key Architectural Features | BP Risk Level | Primary Cause of BP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA) | Alternating layers of single-qubit rotations and entangling gates. | Very High | Rapid convergence to a 2-design on a local connectivity graph [16] [21]. |

| Unstructured Random Circuits | Random selection and arrangement of quantum gates. | Very High | Inherent randomness directly approximates Haar measure [16]. |

| Deep Alternating Ansätze | Many layered structures (L >> 1) with repeated entangling blocks. |

High | High expressibility and entanglement generation at large L [18] [22]. |

| Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs) | Models inspired by classical NNs, often with global operations. | High | Global cost functions and excessive expressibility [16] [20]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Solutions

This section details key methodological tools and concepts used in BP research, functioning as the essential "reagents" for conducting studies in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Barren Plateau Analysis

| Tool / Concept | Function in BP Research |

|---|---|

| Parameter-Shift Rule | A precise method for calculating analytical gradients of quantum circuits by evaluating the circuit at shifted parameters [16]. |

| Unitary t-Designs | A theoretical framework for assessing how closely a given ansatz approximates the Haar measure, which predicts BP occurrence [16] [18]. |

| Local vs. Global Cost Functions | A design choice; local cost functions (measuring few qubits) help mitigate BPs, while global ones (measuring all qubits) induce them [20]. |

| Genetic Algorithms (GAs) | A gradient-free optimization method used to reshape the cost landscape and enhance trainability in BP-prone environments [21]. |

| Lie Algebraic Theory | Provides a mathematical foundation connecting circuit generators, expressibility, and the variance of gradients, guiding both diagnosis and mitigation [19]. |

| Sequential Testing (e.g., SPARTA) | An algorithmic approach that uses statistical tests to distinguish barren plateaus from informative regions in the optimization landscape, enabling risk-controlled exploration [19]. |

| Tilomisole | Tilomisole, CAS:58433-11-7, MF:C17H11ClN2O2S, MW:342.8 g/mol |

| Cervinomycin A2 | Cervinomycin A2, CAS:82658-22-8, MF:C29H21NO9, MW:527.5 g/mol |

The architectural choice of an ansatz is a critical determinant of whether a variational quantum algorithm will be trainable at scale. Ansätze that are highly expressive, unstructured, and generate extensive entanglement—such as hardware-efficient ansätze and random circuits—are most prone to devastating barren plateaus. The common thread is their tendency to approximate a unitary 2-design, leading to an exponential concentration of the cost function landscape.

For researchers in drug development and other applied fields, this implies that carefully tailoring the ansatz to the problem Hamiltonian, rather than defaulting to a generic hardware-efficient structure, is paramount. Promising paths forward include employing local cost functions, constraining circuit expressibility, and using classical pre-training or advanced optimizers like the NPID controller [23] and SPARTA algorithm [19] that are specifically designed to navigate flat landscapes. As the field moves beyond simply copying classical neural network architectures, a deeper understanding of these quantum-specific vulnerabilities will be essential for building scalable and practical quantum algorithms.

Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) and Quantum Machine Learning (QML) models represent a promising paradigm for leveraging near-term quantum computers by combining quantum circuits with classical optimization [24]. In this framework, a parameterized quantum circuit (PQC) transforms an initial state, and the expectation value of an observable is measured to define a loss function. The classical optimizer then adjusts the circuit parameters to minimize this loss. Despite their potential, these algorithms face a significant challenge known as the Barren Plateau (BP) phenomenon, where the optimization landscape becomes exponentially flat as the problem size increases [24] [25]. This concentration of the loss function and the vanishing of its gradients pose a fundamental obstacle to the trainability of variational quantum models, making it essential to understand the mathematical formalisms underlying gradient variance and loss function concentration.

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

The Variational Quantum Computing Framework

The core components of a variational quantum computation are as follows [24]:

- Initial state: An n-qubit state Ï, which can be a simple fiducial state or a data-encoded state.

- Parameterized Quantum Circuit (PQC): A sequence of parametrized unitaries, U(θ) = âˆâ‚—â‚Œâ‚á´¸ Uâ‚—(θₗ), where θ = (θâ‚, θ₂, ..., θ_L) are trainable parameters.

- Observable: A Hermitian operator O measured at the circuit output.

- Loss function: Defined as â„“_θ(Ï, O) = Tr[U(θ)ÏU†(θ)O], which is optimized classically.

In the presence of hardware noise, the loss function may be modified to account for SPAM (State Preparation and Measurement) errors and coherent errors [25].

Barren Plateaus: Formal Definitions

A Barren Plateau is formally characterized by the exponential decay of the variance of the loss function or its gradients with increasing system size (number of qubits, n) [24] [25]. Specifically:

- Loss variance: Varθ[ℓθ(Ï, O)] ∈ O(1/bâ¿) for some b > 1.

- Gradient variance: Varθ[∂ℓθ(Ï, O)/∂θμ] ∈ O(1/bâ¿) for parameter θμ.

This concentration implies that an exponentially precise measurement resolution is needed to determine a minimizing direction, making optimization practically infeasible for large systems [24].

Table 1: Key Mathematical Definitions in Barren Plateau Analysis

| Term | Mathematical Formulation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Loss Function [24] | $\ell_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\rho, O) = \text{Tr}[U(\boldsymbol{\theta})\rho U^\dagger(\boldsymbol{\theta})O]$ | Expectation value of observable O after evolution. |

| Loss Variance [25] | $\text{Var}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}[\ell{\boldsymbol{\theta}}] = \mathbb{E}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}[\ell{\boldsymbol{\theta}}^2] - (\mathbb{E}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}[\ell{\boldsymbol{\theta}}])^2$ | Measure of fluctuation of the loss over the parameter space. |

| Noisy Loss [25] | $\widetilde{\ell}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\rho, O) = \text{Tr}[\mathcal{N}A(\widetilde{U}(\boldsymbol{\theta})\mathcal{N}_B(\rho)\widetilde{U}^\dagger(\boldsymbol{\theta}))O]$ | Loss function incorporating SPAM and coherent errors. |

Mathematical Foundations of Gradient Variance

Analytical Frameworks for Variance Calculation

The calculation of gradient variances has evolved through several analytical frameworks. Early studies often relied on the Weingarten calculus to compute expectations over Haar-random unitaries, typically concluding that gradient expectations are zero and their variance decays exponentially [26]. However, recent research has identified potential inaccuracies in this approach. Yao and Hasegawa (2025) demonstrated that direct exact calculation for circuits composed of rotation gates reveals non-zero gradient expectations, challenging previous results derived from the Weingarten formula [26].

A groundbreaking unified framework is provided by the Lie algebraic theory of barren plateaus [25]. This theory connects the variance of the loss function to the structure of the Dynamical Lie Algebra (DLA) generated by the circuit's generators:

$\mathfrak{g} = \langle i\mathcal{G} \rangle_{\text{Lie}}$

where $\mathcal{G}$ is the set of Hermitian generators of the parametrized quantum circuit. The DLA decomposes into simple and abelian components: $\mathfrak{g} = \mathfrak{g}1 \oplus \cdots \oplus \mathfrak{g}k$, providing a mathematical structure to analyze loss concentration [25].

Exact Gradient Expectation and Variance

For a PQC structured as $U(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \prod{i=1}^d Ui(\boldsymbol{\theta}i)Wi$, where $Ui$ are parameterized gates and $Wi$ are fixed entangling gates, the exact expectation for gradient computations can be performed without relying on the Weingarten formula [26]. This approach yields:

$\mathbb{E}[U(\boldsymbol{\theta})^\dagger A U(\boldsymbol{\theta})] = \sumi \mathbb{E}[Ui(\thetai)^\dagger \cdot A \cdot Ui(\theta_i)]$

This formulation avoids the cross-terms ($i \neq j$) that appear in the Weingarten approach, leading to more accurate variance calculations [26]. The gradient variance has been shown to follow a fundamental scaling law: it is proportional to the ratio of effective parameters in the circuit, highlighting the critical role of parameter efficiency in mitigating BPs [26].

Table 2: Scaling Behavior of Gradient Variances Under Different Conditions

| Condition | Gradient Expectation | Gradient Variance Scaling | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haar-Random Unitary | Zero (per Weingarten calculus) | Exponential decay with qubit count | [26] |

| Deep Hardware-Efficient Ansatz | Zero | Exponential decay with qubit count | [24] |

| Circuit with Rotation Gates | Non-zero | Dependent on effective parameter ratio | [26] |

| Lie Algebraic Framework | Determined by DLA structure | $\text{Var}[\ell_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}] \propto \frac{1}{\dim(\mathfrak{g})}$ for deep circuits | [25] |

Lie Algebraic Theory of Barren Plateaus

The Lie algebraic theory provides a unifying framework that connects all known sources of barren plateaus under a single mathematical structure [25]. This theory offers an exact expression for the variance of the loss function in sufficiently deep parametrized quantum circuits, even in the presence of certain noise models. The key insight is that the dimensionality of the dynamical Lie algebra fundamentally determines the presence and severity of a BP.

Specifically, for a deep circuit that forms an approximate design over the dynamical Lie group, the variance of the loss function can be expressed as [25]:

$\text{Var}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}[\ell{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\rho, O)] = \frac{1}{\dim(\mathfrak{g})} \left( \text{Terms depending on } \rho, O, \mathfrak{g} \right)$

This formulation reveals that when the DLA $\mathfrak{g}$ has exponentially large dimension (as in most practical circuits), the variance decays exponentially, resulting in a BP.

The Lie algebraic framework encapsulates four primary sources of BPs [25]:

- Circuit Expressiveness: When the circuit generates a dense set of unitaries (large DLA dimension).

- Entanglement of Initial State: Highly entangled states can lead to BPs when measured with local observables.

- Locality of Observable: Global observables acting on many qubits exacerbate BPs.

- Hardware Noise: Noise channels can effectively increase the DLA dimension, accelerating loss concentration.

This unified perspective resolves the longstanding conjecture connecting loss concentration to the dimension of the Lie algebra generated by the circuit's generators [25].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Variance Calculation Methodology

To empirically investigate barren plateaus, researchers employ the following protocol for calculating gradient variances [26]:

- Circuit Initialization: Prepare a parameterized quantum circuit with a specific architecture (e.g., hardware-efficient ansatz).

- Parameter Sampling: Randomly sample parameter vectors θ from a uniform distribution over [0, 2π).

- Gradient Computation: Calculate the partial derivative of the loss function with respect to each parameter using the parameter-shift rule or analytical methods.

- Statistical Analysis: Compute the sample variance of the gradients across multiple parameter samples.

- Scaling Analysis: Repeat the process for increasing system sizes (number of qubits) to determine the scaling behavior of the variance.

Lie Algebraic Dimension Analysis

For theoretical analysis of BPs using the Lie algebraic framework, the following methodology is employed [25]:

- Generator Identification: Identify the set of Hermitian generators $\mathcal{G}$ = {Hâ‚, Hâ‚‚, ...} that define the parametrized gates in the circuit.

- DLA Construction: Compute the Lie closure $\mathfrak{g} = \langle i\mathcal{G} \rangle_{\text{Lie}}$ by repeatedly taking commutators of the generators until no new linearly independent operators are found.

- DLA Decomposition: Decompose the DLA into simple and abelian components: $\mathfrak{g} = \mathfrak{g}1 \oplus \cdots \oplus \mathfrak{g}k$.

- Dimension Calculation: Compute the dimension of the DLA and its components.

- Variance Bound Derivation: Use the DLA dimension to derive bounds on the variance of the loss function.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Mathematical Tools for Barren Plateau Research

| Tool/Technique | Function | Application in BP Research |

|---|---|---|

| Weingarten Calculus | Computes integrals over Haar measure on unitary groups | Initial approach for gradient variance calculation in random circuits [26] |

| Parameter-Shift Rule | Exactly computes gradients of quantum circuits | Empirical measurement of gradient variances [26] |

| Lie Algebra Theory | Studies structure of generated Lie algebras | Unified framework for understanding all BP sources [25] |

| Tensor Networks | Efficiently represents quantum states and operations | Classical simulation of quantum circuits to verify BPs [27] |

| Dynamical Lie Algebra (DLA) | Captures expressivity of parametrized circuits | Predicting variance scaling based on algebra dimension [25] |

| Gunacin | Gunacin | Gunacin is a quinone antibiotic for research on bacteria, mycoplasma, and protozoa. Inhibits DNA synthesis. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

| Mazaticol | Mazaticol, MF:C21H27NO3S2, MW:405.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Mitigation Strategies and Theoretical Implications

Strategies for Avoiding Barren Plateaus

While a comprehensive discussion of mitigation strategies is beyond the scope of this formalisms guide, several approaches have been proposed based on the mathematical understanding of gradient variance [24]:

- Local Loss Functions: Using local observables instead of global ones to reduce BP effects [24] [25].

- Structured Ansätze: Designing circuit architectures with constrained DLAs to prevent exponential growth of the algebra dimension [25].

- Parameter Correlation: Leveraging circuits where gradient expectations are non-zero due to parameter relationships [26].

- Pre-training Strategies: Initializing parameters in favorable regions of the landscape before optimization.

Connection to Classical Simulability

An important theoretical implication emerging from BP research is the intriguing connection between the absence of barren plateaus and classical simulability [24]. Circuits that lack BPs often have structures that make them efficiently simulable classically, suggesting a fundamental trade-off between trainability and quantum advantage [24] [25]. This connection is precisely characterized by the Lie algebraic framework: circuits with small DLAs avoid BPs but are often classically simulable [25].

The mathematical formalisms of gradient variance and loss function concentration provide essential insights into the barren plateau phenomenon that plagues variational quantum algorithms. The Lie algebraic theory unifies our understanding of various BP sources and offers exact expressions for variance scaling based on the structure of the dynamical Lie algebra generated by quantum circuit components. While significant progress has been made in formalizing these concepts, ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of gradient expectations and develop architectural strategies to mitigate trainability issues without sacrificing quantum advantage.

Building Robust VQAs: Architectural Choices and Implementation Strategies

Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) represent a promising paradigm for leveraging near-term quantum computers by hybridizing quantum and classical computational resources [28]. These algorithms are designed to function on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, which are characterized by limited qubit counts and significant error rates [29]. The core operational principle of a VQA involves optimizing the parameters of a parameterized quantum circuit (PQC), or ansatz, to minimize a cost function that encodes a specific problem, such as finding the ground state energy of a molecule or solving a combinatorial optimization problem [30].

However, the practical deployment of VQAs faces a significant obstacle: the barren plateau (BP) phenomenon. In a barren plateau, the gradients of the cost function vanish exponentially as the problem size increases, rendering optimization practically impossible [28] [31]. This phenomenon can arise from various factors, including the expressivity of the ansatz, the entanglement in the initial state, the nature of the observable being measured, and the impact of quantum noise, leading to so-called noise-induced barren plateaus (NIBPs) [15] [31]. Understanding the core components of a VQA is thus crucial not only for algorithm design but also for mitigating trainability issues and unlocking the potential of quantum computing for applications like drug development [32] [33].

Core Component 1: Data Encoding and Input State Preparation

The initial step in any VQA is the preparation of the input quantum state, which effectively encodes classical data into a quantum system. For many computational tasks, such as those in quantum chemistry, the input state is a fixed reference state, like the Hartree-Fock state in molecular simulations. In Quantum Machine Learning (QML) applications, the input state ( \rho_j ) is used to encode classical data points into qubits [34].

Data Encoding Techniques

Several methods exist for loading classical data into a quantum state. The simplest example is angle encoding, where classical data points are represented as rotation angles of individual qubits [33]. For instance, two classical data points can be encoded onto a single qubit using its two rotational angles on the Bloch sphere. For more complex, high-dimensional data, multi-qubit systems are employed, though the implementation presents a significant practical challenge [33].

Core Component 2: The Parameterized Quantum Circuit (Ansatz)

The parameterized quantum circuit (PQC), or ansatz, ( U(\theta) ), is the heart of a VQA. It applies a series of parameterized quantum gates to the input state, transforming it into an output state ( \rhoj'(\theta) = U(\theta) \rhoj U^\dagger(\theta) ) [34]. The design of the ansatz is a critical determinant of the algorithm's performance, creating a fundamental trade-off.

The Expressivity vs. Trainability Trade-off and Barren Plateaus

A central challenge in designing an effective ansatz is balancing expressivity and trainability [30].

- Expressivity: An ansatz with a larger number of trainable gates and greater circuit depth can represent a broader hypothesis space, increasing the probability that it contains the solution to the target problem [30].

- Trainability: As circuit depth and qubit count increase, the algorithm becomes more susceptible to the barren plateau phenomenon, where the cost landscape becomes exponentially flat [30] [31]. Furthermore, deep circuits on NISQ devices accumulate noise, which can also induce barren plateaus (NIBPs) and lead to divergent optimization [30] [15].

This trade-off makes the choice of ansatz architecture paramount.

Ansatz Architectures and the Barren Plateau Problem

Table 1: Common Ansatz Architectures and Their Relation to Barren Plateaus

| Ansatz Type | Description | Advantages | Challenges & Relation to BPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware-Efficient | Uses native gate sets and connectivity of specific quantum hardware [30]. | Reduces circuit depth and execution time; complies with physical constraints. | Highly expressive, random structure often leads to barren plateaus [31]. |

| Problem-Inspired | Leverages domain knowledge (e.g., molecular excitations for quantum chemistry) [29]. | More efficient for specific problems; can have fewer parameters. | Design requires expert knowledge; may still face BPs with increasing system size. |

| Quantum Architecture Search (QAS) | Automatically seeks a near-optimal ansatz to balance expressivity and noise/sampling overhead [29] [30]. | Actively mitigates BPs and noise effects; can adapt to hardware constraints. | Introduces a meta-optimization problem; requires additional classical computation. |

Mitigation Strategies: Quantum Architecture Search (QAS)

To navigate the expressivity-trainability trade-off, Quantum Architecture Search (QAS) has been developed. QAS formulates the search for an optimal ansatz as a learning task itself [30]. Instead of testing all possible circuit architectures from scratch—a computationally prohibitive process—QAS uses a one-stage optimization strategy with a supernet and a weight sharing strategy [30]. The supernet indexes all possible ansatze in the search space, and parameters are shared among different architectures. This allows for efficient co-optimization of the circuit architecture ( \mathbf{a} ) and its parameters ( \theta ) to find a pair ( (\theta^, \mathbf{a}^) ) that minimizes the cost function while managing the effects of noise and Barren Plateaus [30].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of a Quantum Architecture Search (QAS) framework designed to mitigate barren plateaus by finding an ansatz that balances expressivity and trainability.

Core Component 3: Measurement and Cost Function

After the ansatz has been executed, measurements are performed to extract classical information used to evaluate the algorithm's performance.

The Cost Function

The measurement outcomes are used to compute the cost function, ( C(\theta) ), which encodes the problem objective. A typical form of the cost function is: [ C(\theta) = \sumj cj \text{Tr}( Oj \rhoj'(\theta) ) ] where ( { Oj } ) is a set of observables, and ( cj ) is a set of functions determined by the specific problem [34]. The goal of the VQA is to find the parameters ( \theta^* ) that minimize this cost.

Cost Function Design and Barren Plateaus

The choice of cost function itself is a critical factor for trainability. Cost functions defined by global observables, which act non-trivially on all qubits, are particularly prone to barren plateaus [34]. Research has shown that a key strategy for mitigating BPs is to design local cost functions, where the observables ( O_j ) act on a small number of qubits [34]. This locality in the cost function can prevent the exponential vanishing of gradients and make the optimization landscape more navigable.

Table 2: Types of Cost Functions and Their Impact on Barren Plateaus

| Cost Function Type | Mathematical Description | Impact on Barren Plateaus | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Cost Function | ( C^{global}(\theta) = \sumj cj \text{Tr} \langle Oj^{global} \rhoj'(\theta) \rangle ) e.g., ( Oj^{global} = Ij - | 0\rangle\langle 0 | _j ) [34] | Highly susceptible to barren plateaus; gradients vanish exponentially with qubit count. |

| Local Cost Function | ( C^{local}(\theta) = \sumj cj \text{Tr} \langle Oj^{local} \rhoj'(\theta) \rangle ) (Observables ( O_j^{local} ) act on few qubits) [34] | Mitigates barren plateaus; preserves gradient signals and enhances trainability. |

Core Component 4: Classical Processing and Optimization

The final core component is the classical optimizer, which closes the hybrid quantum-classical loop.

The Role of the Classical Optimizer

The classical processor receives the computed value of the cost function ( C(\theta) ) and uses it to update the parameters ( \theta ) of the quantum ansatz. This involves employing classical optimization techniques, such as gradient descent or more advanced gradient-based optimizers, to find the parameter set ( \theta^* ) that minimizes the cost [30] [34].

Optimization in the Presence of Barren Plateaus

When the algorithm encounters a barren plateau, the gradients received by the classical optimizer are not just small but exponentially close to zero, making it impossible to determine a direction for parameter updates [28] [31]. This halts meaningful progress. Furthermore, noise from the quantum hardware can distort the cost landscape and introduce noise-induced limit sets (NILS), where the cost function converges to a range of values instead of a single minimum, further complicating the optimization process [15].

Advanced Strategies: Circuit Knitting and Initialization

To enhance scalability and mitigate BPs, advanced strategies are being developed:

- Circuit Knitting (CK): This technique partitions a large quantum circuit into smaller, executable subcircuits, enabling VQAs to tackle problems beyond the qubit count of current hardware. However, it introduces an exponential sampling overhead. The CKVQA framework co-optimizes ansatz design and circuit knitting to balance this overhead with algorithmic performance [29].

- Classical Initialization: Inspired by classical deep learning, researchers are exploring advanced parameter initialization strategies (e.g., Xavier, He) to help VQAs avoid barren plateaus at the start of training. While initial results show modest improvements, this remains an active area of research [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key experimental components and software tools essential for conducting research on VQAs and barren plateaus.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for VQA and Barren Plateau Investigation

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz | Algorithmic Component | Provides a baseline ansatz for testing on specific NISQ hardware; often used to study noise-induced BPs [30]. |

| Quantum Architecture Search (QAS) | Algorithmic Framework | Automates the discovery of BP-resilient ansatz architectures by balancing expressivity and trainability [30]. |

| Local Cost Function | Algorithmic Component | Replaces global cost functions to mitigate barren plateaus and make gradient-based optimization feasible [34]. |

| Circuit Knitting (CK) | Scalability Technique | Allows for the execution of large circuits on limited hardware; studied to understand its interplay with BPs and sampling overhead [29]. |

| Amazon Braket | Cloud Platform | Provides managed access to quantum simulators and hardware (e.g., from Rigetti, IonQ) for running VQA experiments [32]. |

| Q-CTRL Fire Opal | Software Tool | Improves algorithm performance on quantum hardware via error suppression and performance optimization, relevant for NIBP studies [32]. |

| (R)-2-Methylimino-1-phenylpropan-1-ol | (R)-2-Methylimino-1-phenylpropan-1-ol, MF:C10H13NO, MW:163.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Imidazolidinyl Urea | Imidazolidinyl Urea, CAS:39236-46-9, MF:C11H16N8O8, MW:388.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The four core components of a VQA—data encoding, ansatz, measurement, and classical processing—are deeply interconnected, and choices in each directly influence the susceptibility of the algorithm to the barren plateau phenomenon. The ansatz architecture and the design of the cost function are particularly critical levers. Navigating the expressivity-trainability trade-off requires sophisticated strategies like Quantum Architecture Search and the use of local cost functions. As the field moves forward, overcoming the barren plateau challenge will not come from simply adapting classical methods but from innovating quantum-native approaches that are tailored to the unique properties and constraints of quantum information processing [31]. The continued research and development of these core components are essential for realizing the potential of variational quantum algorithms in scientific discovery and industrial application, including the demanding field of drug development.

The pursuit of practical quantum advantage using variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) hinges on effectively navigating the barren plateau (BP) phenomenon, where the optimization landscape becomes exponentially flat as problem size increases [17]. At the heart of every VQA lies the ansatz—a parameterized quantum circuit that defines the algorithm's expressibility and trainability. Ansatz design represents a critical frontier where theoretical quantum advantage meets practical implementability, particularly for applications in drug development and quantum chemistry [36].

The BP phenomenon presents a fundamental challenge to the trainability of VQAs, as exponentially small gradients render parameter optimization intractable for large problem sizes [17] [15]. All components of a VQA—including ansatz architecture, initial state preparation, observable measurement, and loss function construction—can induce BPs when ill-suited to the problem structure [28]. This review examines ansatz design strategies through the lens of BP mitigation, analyzing the transition from hardware-efficient general-purpose circuits to chemically-inspired problem-specific architectures.

Recent theoretical advances have established deep connections between the BP phenomenon and classical simulability, suggesting that provable absence of BPs may imply efficient classical simulation of the quantum circuit [17]. This revelation necessitates a fundamental rethinking of variational quantum computing and underscores the importance of problem-informed ansatz design that strategically navigates the trade-off between expressibility and trainability.

Barren Plateaus: Theoretical Foundation and Impact on Ansatz Design

Barren plateaus manifest as the exponential decay of cost function gradients with increasing qubit count, making optimization practically impossible for large-scale problems. The BP phenomenon is now understood as a form of curse of dimensionality arising from unstructured operation in exponentially large Hilbert spaces [17]. Theoretical work has established equivalences between BPs and other challenging landscape features, including cost concentration and narrow gorges [17].

The impact of BPs extends beyond mere trainability concerns. Recent research suggests that provable absence of barren plateaus may imply classical simulability of the quantum circuit [17] [17]. This profound connection places ansatz design at the center of a fundamental trade-off: circuits that are too expressive suffer from BPs, while those that are too constrained may be efficiently simulated classically, negating any potential quantum advantage.

Classification of Barren Plateaus

| BP Type | Primary Cause | Impact on Ansatz Design |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithm-induced | Unstructured random parameterized circuits [17] | Requires structured, problem-informed ansatz design |

| Noise-induced (NIBP) | Unital and non-unital noise channels [15] | Demands shallow circuits and error-resilient architectures |

| Cost function-induced | Global observables and measurements [17] | Favors local measurements and problem-tailored cost functions |

| Initial state-induced | High entanglement in input states [37] | Necessitates compatibility between ansatz and input state entanglement |

The table above categorizes different types of barren plateaus and their implications for ansatz design. Particularly insidious are noise-induced barren plateaus (NIBPs), which have been demonstrated for both unital noise maps and a class of non-unital maps called Hilbert-Schmidt-contractive maps, which include amplitude damping [15]. This generalization beyond unital noise reveals that NIBPs are more pervasive than previously thought, significantly constraining the viable depth of practical ansatze on near-term devices.

Ansatz Architectures: Taxonomy and Characteristics

Hardware-Efficient Ansatzes (HEA)

Hardware-efficient ansatzes prioritize implementability on near-term quantum hardware by utilizing native gates and connectivity [37]. HEAs employ shallow circuits to minimize the impact of decoherence and gate errors, but this practical advantage comes with significant theoretical limitations regarding trainability.

Research has revealed that the trainability of HEAs crucially depends on the entanglement properties of input data [37]. Shallow HEAs suffer from BPs for quantum machine learning tasks with input data satisfying a volume law of entanglement, but can remain trainable for tasks with data following an area law of entanglement [37]. This dichotomy establishes a "Goldilocks scenario" for HEA application: they are most appropriate for problems with inherent locality and limited entanglement scaling.

The ambivalence toward HEAs arises from their dual nature: while offering practical implementability, they frequently encounter trainability limitations. Theoretical analysis demonstrates that shallow HEAs can avoid barren plateaus in specific contexts, particularly when the problem structure aligns with the hardware constraints [37]. This has important implications for drug development applications, where molecular systems often exhibit localized entanglement patterns that may be compatible with HEA architectures.

Chemically-Inspired Ansatzes

Chemically-inspired ansatzes embed domain knowledge from quantum chemistry into circuit design, offering a problem-specific approach that can potentially mitigate BPs while maintaining expressibility for target applications. Unlike hardware-efficient approaches, chemically-inspired circuits prioritize physical relevance over hardware compatibility.

The most prominent chemically-inspired ansatzes include:

- Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC): Inspired by classical computational chemistry, UCC constructs ansatzes through exponentiated excitation operators, preserving physical symmetries and offering systematic improvability [36]

- Qubit Coupled Cluster: A resource-efficient adaptation of UCC for qubit architectures

- Hamiltonian Variational Ansatz: Incorporates symmetries and conservation laws of the target Hamiltonian

These chemically-informed approaches offer potential BP mitigation through structured circuit design that respects the physical constraints of the problem, avoiding the uncontrolled entanglement generation that plagues random circuits.

Problem-Inspired Ansatzes

Problem-inspired ansatzes occupy a middle ground between hardware efficiency and chemical inspiration, incorporating high-level problem structure without strict adherence to physical symmetries. Examples include the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) ansatz for combinatorial optimization, which encodes problem structure through driver and mixer Hamiltonians [36].

Recent advances in adaptive ansatzes like ADAPT-VQE dynamically construct circuits based on problem-specific criteria, offering a promising approach to navigate the expressibility-trainability tradeoff [36]. These methods grow the circuit architecture iteratively, selecting operators that maximally reduce the energy at each step, potentially avoiding both BPs and excessive resource requirements.

Comparative Analysis of Ansatz Strategies

The table below provides a systematic comparison of ansatz design strategies for quantum chemistry applications, highlighting their respective advantages and limitations in the context of barren plateaus.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Ansatz Design Strategies for Quantum Chemistry

| Ansatz Type | BP Resilience | Hardware Compatibility | Chemical Accuracy | Scalability | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware-Efficient (HEA) | Context-dependent [37] | High | Limited | Moderate | Quantum machine learning with area law entanglement [37] |

| Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) | Moderate (structure-dependent) | Low (requires deep circuits) | High | Challenging for large systems | Molecular ground state energy calculation [36] |

| Adaptive VQE | High (through iterative construction) | Moderate | High | Promising | Strongly correlated molecular systems [36] |

| Hamiltonian Variational | High (preserves symmetries) | Moderate | High | Good for lattice models | Quantum simulation of materials [36] |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The search for quantum advantage in chemistry applications has yielded concrete benchmarks demonstrating the progressive improvement of ansatz designs:

- Error Suppression: Recent hardware advances have pushed error rates to record lows of 0.000015% per operation [38]

- Algorithmic Efficiency: Algorithmic fault tolerance techniques have reduced quantum error correction overhead by up to 100 times [38]

- Chemical Accuracy: VQE simulations have achieved chemical accuracy (1.6 kcal/mol) for small molecules like LiH and BeHâ‚‚ using problem-inspired ansatzes [36]

- Runtime Performance: Google's Willow quantum chip completed a benchmark calculation in approximately five minutes that would require a classical supercomputer 10²ⵠyears to perform [38]

These metrics underscore the rapid progress in hardware capabilities that increasingly enables the implementation of more sophisticated ansatz designs previously limited by hardware constraints.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Ansatz Selection and Validation

The following workflow provides a systematic methodology for selecting and validating ansatz designs for specific chemical applications while monitoring for barren plateaus.

Gradient Measurement Protocol for Barren Plateau Detection