Unlocking Quantum Advantage: How Quantum Computing Solves Strongly Correlated Systems in Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative potential of quantum computing in simulating strongly correlated electron systems, a long-standing challenge for classical computational methods.

Unlocking Quantum Advantage: How Quantum Computing Solves Strongly Correlated Systems in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of quantum computing in simulating strongly correlated electron systems, a long-standing challenge for classical computational methods. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive analysis spanning from foundational quantum algorithms to their practical application in real-world drug discovery pipelines. We examine innovative methodological frameworks like VQE and Trotterized MERA, detail optimization strategies for noisy hardware, and validate the technology's progress through comparative benchmarks and case studies in prodrug activation and protein-ligand binding. The synthesis of current research indicates that hybrid quantum-classical approaches are already delivering enhanced efficiency and accuracy, paving the way for a new paradigm in predictive in silico research.

The Strong Correlation Challenge: Why Classical Computing Falls Short

Defining Strongly Correlated Systems and Their Pervasive Role in Molecular Science

Strongly correlated systems represent a fundamental class of materials and molecular structures where electron-electron interactions dominate the physical properties, leading to behaviors that cannot be explained by conventional independent-electron models [1]. In these systems, the motion of one electron is strongly dependent on the positions of other electrons, creating complex quantum phenomena that challenge both theoretical understanding and computational modeling [2]. The term "strong correlation" originates from many-body perturbation theory, where systems are classified as strongly correlated when low-order perturbation theory fails to yield accurate results due to significant near-degeneracy effects [2]. This stands in sharp contrast to weakly correlated systems, where chemical accuracy can typically be achieved with single-reference methods like coupled-cluster theory with single and double excitations [2].

The fundamental challenge in understanding strongly correlated systems lies in their intrinsic multiconfigurational character [2]. Whereas weakly correlated systems can be adequately described by a single Slater determinant or reference function, strongly correlated systems require a linear combination of multiple configuration state functions for qualitatively correct description [2]. This multireference character manifests prominently in key areas of molecular science, including open-shell transition-metal compounds, molecular magnets, biradicals, bond dissociation processes, and electronically excited states [2]. The historical development of this field has roots in the pioneering works of Mott, Friedel, Anderson, and Kondo, with contemporary research expanding to include heavy-fermion systems, high-temperature superconductors, and quantum spin liquids [3] [1].

Fundamental Challenges in Classical Computational Methods

Limitations of Single-Reference Methods

Traditional computational approaches face significant challenges when applied to strongly correlated systems due to their inherent methodological limitations. Kohn-Sham density functional theory (KS-DFT), while revolutionary for its high accuracy-to-cost ratio in weakly correlated systems, demonstrates substantially reduced accuracy for strongly correlated cases when used with available approximate exchange-correlation functionals [2]. The fundamental issue stems from KS-DFT's representation of electron density by a single Slater determinant, which proves qualitatively incorrect for intrinsically multiconfigurational systems [2]. Although unrestricted KS calculations can sometimes improve energetics for strongly correlated systems, they often produce spin densities and spatial symmetry that differ from the physical wave function [2].

Standard wave function methods like configuration interaction (CI) and coupled-cluster (CC) theory also struggle with strong correlation effects [2]. These methods generate excitations from a single reference function, but in strongly correlated systems, low-order excitations from only one reference configuration state function fail to produce all necessary excitations with accurate coefficients for qualitatively correct description [2]. This limitation becomes particularly severe when two or more CSFs are nearly degenerate, a situation common in transition metal compounds with partially filled d or f orbitals, biradicals, and dissociating bonds [2].

The Strong Correlation Regime: Experimental Signatures

Strongly correlated electron systems exhibit distinctive experimental signatures that differentiate them from conventional materials. These include enhanced values of the Sommerfeld coefficient of the specific heat (γ) and the Pauli susceptibility (χ) as temperature approaches zero [1]. The electrical resistivity in these systems follows a characteristic temperature dependence described by Ï(T) = Ïâ‚€ + AT², where A is an enhanced coefficient inversely proportional to a characteristic temperature Tâ‚€ that describes the system [1]. This characteristic temperature may correspond to the Kondo temperature (TK), spin-fluctuation temperature (Tsf), or valence-fluctuation temperature (T_vf), depending on the specific system [1].

The electronic Grüneisen parameter (Ωe) provides another important experimental indicator, with values ranging from 10 to 100 for strongly correlated systems compared to Ωe ∼ 1–2 for simple metals [1]. Additional experimental signatures include scaling behavior of Ï(p, T)/Ï(0, T_0) over extended pressure and temperature ranges, with breakdown of scaling indicating changes in the competition between different types of interactions [1].

Table 1: Experimental Signatures of Strongly Correlated Electron Systems

| Property | Behavior in Strongly Correlated Systems | Comparison with Simple Metals |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Heat Coefficient (γ) | Strongly enhanced as T→0 | Moderate temperature dependence |

| Pauli Susceptibility (χ) | Strongly enhanced as T→0 | Weak temperature dependence |

| Electrical Resistivity | Ï(T) = Ïâ‚€ + AT² with large A | Typically Ï(T) = Ïâ‚€ + ATâµ (Bloch-Grüneisen) |

| Electronic Grüneisen Parameter (Ω_e) | Ranges from 10 to 100 | Typically 1–2 |

| Scaling Behavior | Ï(p, T)/Ï(0, Tâ‚€) scales over extended ranges | No universal scaling behavior |

Quantum Computing Approaches for Strong Correlation

Emerging Quantum Algorithms

Quantum computing offers promising approaches to overcome the limitations of classical methods for strongly correlated systems through several innovative algorithms. The Trotterized Multiscale Entanglement Renormalization Ansatz (TMERA) combines the representational power of tensor networks with variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) approaches, implementing MERA disentanglers and isometries as circuits of two-qubit gates [4]. This approach demonstrates polynomial quantum advantage for critical one-dimensional spin systems, with the advantage increasing for higher spin quantum numbers [4]. The method requires only ð’ª(T) qubits for evaluating energy expectation values and gradients, where T is the number of MERA layers, and employs mid-circuit resets to eliminate T-dependence completely [4].

Multiconfiguration Pair-Density Functional Theory (MC-PDFT) represents another hybrid approach that blends multiconfiguration wave function theory with density functional theory to treat both near-degeneracy correlation and dynamic correlation [2]. This method is more affordable than multireference perturbation theory, multireference configuration interaction, or multireference coupled cluster theory while proving more accurate for many properties than Kohn-Sham DFT [2]. Recent developments include localized-active-space MC-PDFT, generalized active-space MC-PDFT, density-matrix-renormalization-group MC-PDFT, and multistate MC-PDFT for excited states [2].

Quantum embedding methods such as VQE-in-DFT combine the variational quantum eigensolver algorithm with density functional theory, enabling simulation of strongly correlated fragments embedded in larger molecular systems [5]. This approach has been successfully implemented on real quantum devices for challenging processes like triple bond breaking in butyronitrile [5]. Another innovative approach represents complex non-unitary interactions as sums of compact unitary representations that can be efficiently coded into quantum computers, extending beyond ground-state simulations to excited states and thermal states [6].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

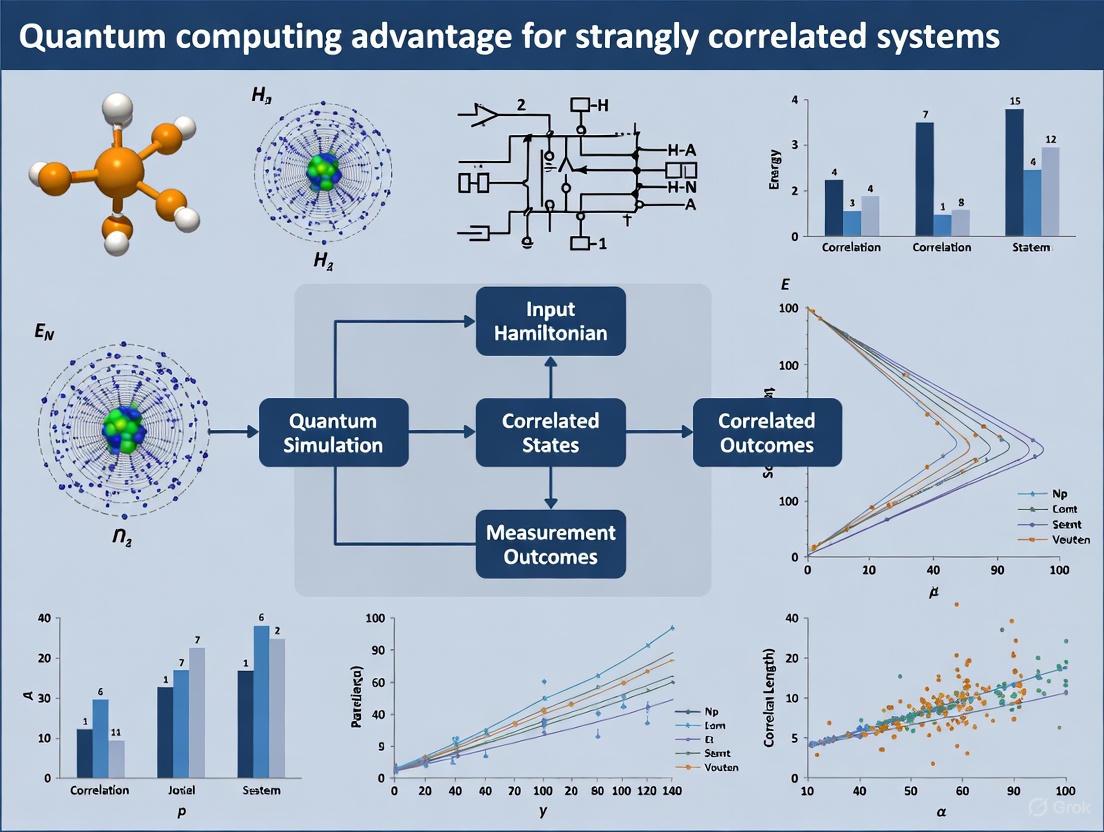

The implementation of quantum algorithms for strongly correlated systems follows specific experimental protocols tailored to leverage quantum hardware capabilities while mitigating current limitations. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for quantum computational approaches to strongly correlated systems:

Figure 1: Quantum Computing Workflow for Strongly Correlated Systems

The TMERA-VQE protocol follows a specific implementation sequence [4]:

- System Disentanglement: Apply hierarchical layers of unitaries to disentangle degrees of freedom

- Renormalization: Use isometries to reduce site count by branching factor b in each layer transition

- Trotterization: Implement disentanglers and isometries as brick-wall or parallel random-pair circuits with two-qubit gates

- Measurement: Evaluate local operator expectation values within causal cones

- Optimization: Employ gradient-based optimization of circuit parameters

For quantum embedding approaches [5]:

- System Partitioning: Divide the complete system into strongly correlated fragment and environment

- DFT Calculation: Perform classical DFT calculation on the full system

- Embedding Potential Construction: Project the environment onto fragment space

- VQE Simulation: Solve the embedded fragment problem using variational quantum eigensolver

- Property Integration: Combine fragment and environment properties for final results

Comparative Performance Analysis

Method Benchmarking and Quantum Advantage

The comparative performance between classical and quantum computational methods for strongly correlated systems reveals distinct advantages and limitations across different regimes. The following table summarizes key quantitative comparisons based on current research:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Computational Methods for Strongly Correlated Systems

| Method | Computational Scaling | Key Advantages | Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kohn-Sham DFT | O(N³) | High accuracy-to-cost ratio for weak correlation; Wide applicability | Poor accuracy for strong correlation; Symmetry breaking issues | Ground states of weakly correlated molecules [2] |

| Multireference CI | O(N!(N−n)!n!) | Systematic improvability; High accuracy for small systems | Exponential scaling; Intractable for large systems | Small multireference systems [2] |

| DMRG | O(χ³) | High accuracy for 1D systems; Controlled bond dimension | Performance degradation in higher dimensions; Memory-intensive | Quasi-1D systems like spin chains [4] |

| TMERA-VQE | O(tT) for quantum; O(χâ¹) for classical MERA | Polynomial quantum advantage; Noise resilience | Current hardware limitations; Circuit depth constraints | Critical quantum magnets [4] |

| MC-PDFT | Between KS-DFT and MRCI | Accurate for static and dynamic correlation; Affordable | Functional development challenges; Active space dependence | Transition metal complexes, biradicals [2] |

| VQE-in-DFT | Fragment-dependent | Enables quantum simulation of large systems; Leverages classical data | Embedding approximation errors; Fragment selection sensitivity | Triple bond breaking in butyronitrile [5] |

The quantum advantage of TMERA-VQE over classical MERA algorithms has been substantiated through benchmarking on critical spin chains, showing polynomial improvement that increases with spin quantum number [4]. Algorithmic phase diagrams suggest considerably larger quantum advantages for systems in spatial dimensions D ≥ 2 [4]. For the concrete example of the TMERA approach applied to critical one-dimensional quantum magnets, researchers have demonstrated that the quantum computational complexity scales polynomially with system parameters, while classical MERA simulations based on exact energy gradients or variational Monte Carlo show higher scaling exponents [4].

Accuracy Metrics and Validation

The accuracy of quantum algorithms for strongly correlated systems is typically validated against established classical methods and experimental data where available. For the TMERA approach, energy accuracy relative to exact solutions provides the primary metric, with studies demonstrating substantial improvement over classical approximations [4]. The quantum embedding VQE-in-DFT method has been validated through accurate simulation of triple bond breaking in butyronitrile, correctly capturing the strong correlation effects during bond dissociation where single-reference methods fail [5].

MC-PDFT has been extensively benchmarked across diverse chemical systems, showing significantly improved performance over KS-DFT for transition metal complexes, biradicals, and excited states while maintaining computational affordability [2]. The method's accuracy typically falls between KS-DFT and high-level multireference methods like MRCI, positioning it as a practical compromise for systems where high-level multireference calculations are prohibitively expensive [2].

Computational Methods and Algorithms

Researchers investigating strongly correlated systems require familiarity with a diverse toolkit of computational methods and algorithms. The following table outlines essential computational resources:

Table 3: Essential Computational Methods for Strongly Correlated Systems Research

| Method Category | Specific Methods | Primary Function | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wave Function Theory | MC-PDFT, MRCI, CASSCF, DMRG | Treat static correlation; Multireference description | [2] |

| Density Functional Theory | Hybrid functionals, meta-GGAs, DFT+U | Balance accuracy and cost; Embedding frameworks | [2] [5] |

| Tensor Networks | MERA, PEPS, Tree Tensor Networks | Represent entanglement; Renormalization group flow | [4] |

| Quantum Algorithms | VQE, QAOA, Quantum Phase Estimation | Quantum advantage; Strong correlation treatment | [4] [6] [7] |

| Embedding Theory | DMFT, Projection-based embedding | Divide-and-conquer strategies; Fragment focusing | [5] |

Experimental and Characterization Techniques

Experimental validation of strongly correlated behavior relies on specialized characterization techniques that probe electronic and magnetic properties:

- Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS): Used to study electronic excitations and phonon harmonics in materials like κ-(BEDT-TTF)₂Cu₂(CN)₃, revealing electron-phonon coupling and spin-liquid behavior [3]

- Polarization-dependent NEXAFS: Provides information about orbital hybridization and electronic structure, as applied to BaVS₃ to study vanadium-sulfur hybridization [3]

- Resonant diffraction: Determines precise magnetic ordering, as implemented for BaVS₃ to identify incommensurate antiferromagnetic order [3]

- Electrical resistivity measurements: Characterize temperature dependence (Ï(T) = Ïâ‚€ + AT²) and scaling behavior under pressure [1]

- Specific heat measurements: Identify enhanced Sommerfeld coefficients and non-Fermi liquid behavior near quantum critical points [1]

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The field of strongly correlated systems research is rapidly evolving, with several promising directions emerging at the intersection of quantum computation, materials design, and algorithmic development. Near-term research priorities include improving the convergence and efficiency of hybrid quantum-classical algorithms, with recent advances demonstrating substantial improvements through layer-by-layer MERA initialization and parameter space path-following techniques [4]. Reducing two-qubit rotation angles in quantum circuits has also shown promise for experimental implementations, with studies indicating that average angle amplitude can be considerably reduced without substantial effect on energy accuracy [4].

The development of more sophisticated quantum embedding frameworks represents another active research direction, aiming to extend the reach of quantum algorithms to larger molecular systems while maintaining computational feasibility on current hardware [5]. These approaches enable the application of quantum methods to specific strongly correlated fragments while treating the remainder of the system with classical methods [5]. Additionally, the exploration of new functional forms in MC-NEFT (multiconfiguration nonclassical-energy functional theory), including density-coherence functionals and machine-learned functionals, provides promising avenues for enhancing accuracy without prohibitive computational cost [2].

The broader timeline for quantum advantage in industrial applications is actively being assessed through workshops and collaborative efforts between academia and industry [7]. These initiatives focus on advancing quantum phase estimation for ground-state energy computations and developing hybrid quantum-classical workflows for practical applications in materials discovery, chemical reaction optimization, and drug design processes [7]. As quantum hardware continues to improve in qubit count, connectivity, and error resilience, the simulation of strongly correlated systems is positioned to be among the first demonstrations of practical quantum advantage in computational chemistry and materials science.

The accurate simulation of quantum mechanical systems stands as a central challenge across chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery. For decades, Density Functional Theory (DFT) has served as the workhorse of computational chemistry, enabling researchers to investigate the electronic structure of atoms, molecules, and solids. Its popularity stems from an favorable accuracy-to-computational cost ratio that makes it applicable to systems containing hundreds or even thousands of atoms. However, DFT suffers from a fundamental limitation: its approximations fail dramatically for strongly correlated electron systems, where electron-electron interactions dominate the physical behavior [8].

This failure arises from the method's treatment of electron correlation. In practice, all practical DFT calculations employ approximate functionals whose errors remain uncontrolled and systematic. As noted in a 2025 assessment, "DFT fails entirely on a broad class of interesting problems," including high-temperature superconductors, complex magnetic materials, and certain catalytic processes [8]. The infamous 2023 LK-99 episode highlighted this limitation, as researchers attempting to characterize the purported room-temperature superconductor found DFT calculations yielded mixed and ultimately unreliable results, forcing a return to experimental synthesis [8].

This article examines the exponential wall facing classical computational methods when addressing strongly correlated systems and explores how quantum computing offers a potential pathway beyond these limitations.

The DFT Breakdown: When Mean-Field Approximations Fail

Theoretical Limitations of DFT

DFT operates within a mean-field framework where complex many-electron interactions are approximated by an effective potential. While this approach works reasonably well for systems with weak electron correlations, it fundamentally misrepresents physics in strongly correlated regimes. The central shortcoming lies in the exchange-correlation functional, which in practice must be approximated, as the exact form remains unknown [8] [9].

The limitations manifest in several key areas:

- Strong correlation regimes: Systems with localized d- and f-electrons, such as transition metal oxides and lanthanide compounds

- Bond breaking reactions: Particularly in transition metal catalysis and reaction pathway analysis

- Van der Waals interactions: Weak dispersion forces crucial in molecular crystals and supramolecular chemistry

- Band gap prediction: Systematic underestimation of semiconductor and insulator band gaps

- Excited states: Charge transfer excitations and strongly correlated excited states

As one assessment noted, "Despite all the intellectual and financial capital expended, we still don't understand why the painkiller acetaminophen works, how type-II superconductors function, or why a simple crystal of iron and nitrogen can produce a magnet with such incredible field strength" [8].

Practical Consequences for Research and Development

The limitations of DFT have tangible consequences across multiple industries. In pharmaceutical research, the inability to accurately model strongly correlated systems hampers drug discovery efforts, particularly for compounds involving transition metals or complex electronic processes. The current paradigm involves "searching for compounds in Amazonian tree bark to cure cancer and other maladies, manually rummaging through a pitifully small subset of a design space encompassing 10^60 small molecules" [8].

In materials science, the failure to predict and explain phenomena in high-temperature superconductors, complex magnetic materials, and certain catalytic processes slows innovation in energy storage, quantum materials, and industrial catalysis. The LK-99 episode of 2023 demonstrated how DFT could not reliably determine whether a material was truly superconducting, forcing researchers to abandon computational methods for traditional synthesis approaches [8].

Table 1: Quantitative Limitations of DFT for Strongly Correlated Systems

| System Type | DFT Performance | Specific Failure Mode | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Oxides | Poor | Incorrect electronic structure, magnetic properties | Hinders development of improved batteries, catalysts |

| Molecular Magnetic Materials | Inadequate | Wrong spin state ordering, magnetic coupling | Limits design of molecular magnets, spintronic materials |

| Enzyme Active Sites | Unreliable | Incorrect redox potentials, reaction barriers | Impairs rational drug design, enzyme engineering |

| High-Tc Superconductors | Fails fundamentally | Cannot describe superconducting mechanism | Prevents computational design of new superconductors |

| Strongly Correlated Catalysts | Variable, often poor | Incorrect reaction energetics, activation barriers | Slows catalyst optimization for industrial processes |

Beyond DFT: Classical Correlated Electron Methods and Their Scaling Limits

Wavefunction-Based Quantum Chemistry Methods

Beyond DFT, computational chemists have developed more sophisticated wavefunction-based methods that systematically account for electron correlation. These include:

- Coupled Cluster Theory (CC): Particularly CCSD(T), considered the "gold standard" for molecular energetics

- Configuration Interaction (CI): Systematic expansion of electron configurations

- Multireference Methods: CASSCF, CASPT2 for strongly correlated systems

- Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC): Stochastic approaches to the many-electron problem

While these methods offer improved accuracy, they come with prohibitive computational costs. Coupled cluster with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations [CCSD(T)] scales as the seventh power of system size (O(Nâ·)), limiting applications to small molecules. Full configuration interaction (FCI), while exact in a given basis set, scales factorially with system size and remains restricted to systems with only a handful of atoms [9].

Density Matrix Renormalization Group and Tensor Networks

For extended systems, the Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG) and related tensor network methods have emerged as powerful tools for strongly correlated one-dimensional systems. These methods exploit the entanglement structure of quantum many-body states to achieve high accuracy with manageable computational resources [10].

However, these methods face their own exponential walls. As noted in recent research, "traditional tensor network methods, particularly those based on matrix product states (MPS) Ansätze, face fundamental limitations due to their limited ability to capture highly entangled states. Specifically, the popular MPS Ansatz suffers from an exponentially increasing demand for computational resources due to the area law scaling of entanglement entropy" [11].

The Multiscale Entanglement Renormalization Ansatz (MERA) offers improved capability for critical systems but remains limited in its application to higher-dimensional systems or those with complex entanglement structures [10].

Table 2: Computational Scaling of Classical Electronic Structure Methods

| Method | Computational Scaling | Maximum Practical System Size | Key Limitations for Strong Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (Hybrid Functionals) | O(N³-Nâ´) | 1000+ atoms | Uncontrolled errors, functional dependence |

| MP2 | O(Nâµ) | ~100 atoms | Poor for strongly correlated systems |

| CCSD(T) | O(Nâ·) | ~20-30 atoms | Prohibitive cost for larger systems |

| DMRG (1D) | Exponential in bond dimension | ~100 orbitals (1D) | Limited by entanglement, primarily 1D |

| AFQMC | O(N³-Nâ´) | ~100 electrons | Fermionic sign problem for real materials |

| FCI | Factorial | ~10 orbitals | Only feasible for very small systems |

The Quantum Computing Pathway for Strongly Correlated Systems

Quantum Algorithms for Electronic Structure

Quantum computers offer a fundamentally different approach to the electronic structure problem, exploiting quantum mechanical principles to represent and simulate quantum systems naturally. Several algorithmic approaches have been developed:

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) uses a hybrid quantum-classical approach to find ground states of molecular systems. Quantum processors prepare and measure parameterized trial states, while classical optimizers adjust parameters to minimize the energy [12]. Recent work has demonstrated VQE simulations pushing "toward practical chemistry applications" [12].

The Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) algorithm provides a direct route to ground and excited state energies with provable performance guarantees, though it requires deeper quantum circuits and greater coherence times.

Trotterized dynamics implements the time evolution operator eâ»â±á´´áµ— through sequential application of quantum gates, enabling simulation of chemical dynamics and access to spectral properties [13] [9].

Recent research has demonstrated that "quantum simulation of exact electron dynamics can be more efficient than classical mean-field methods" [9], with first-quantized quantum algorithms enabling "exact time evolution of electronic systems with exponentially less space and polynomially fewer operations in basis set size than conventional real-time time-dependent Hartree-Fock and density functional theory" [9].

Embedding Methods and Quantum-Classical Hybrid Approaches

Quantum embedding methods represent a promising near-term strategy that combines quantum and classical resources. In the projection-based embedding approach, a strongly correlated fragment is treated using quantum algorithms, while the remainder of the system is handled with classical methods like DFT [14].

This VQE-in-DFT approach "is a promising route for the efficient investigation of strongly-correlated quantum many-body systems on quantum computers" [14]. Implementations have successfully simulated triple bond breaking in butyronitrile, demonstrating the method's potential for chemical applications [14].

For strongly-correlated lattice models, the Trotterized MERA (Multiscale Entanglement Renormalization Ansatz) approach has shown promise. Recent research indicates "a polynomial quantum advantage in comparison to classical MERA simulations" [13] [10], with algorithmic phase diagrams suggesting "an even greater separation for higher-dimensional systems" [10].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Quantum Hardware Advances and Error Correction

Recent advances in quantum hardware have substantially improved prospects for quantum simulation of chemical systems. In 2025, Google's Willow quantum chip, featuring 105 superconducting qubits, demonstrated exponential error reduction as qubit counts increased—a critical milestone known as going "below threshold" [15]. The Willow device completed "a benchmark calculation in approximately five minutes that would require a classical supercomputer 10^25 years to perform" [15].

Error correction has seen dramatic progress, with researchers pushing "error rates to record lows of 0.000015% per operation" [15]. Algorithmic fault tolerance techniques have reduced "quantum error correction overhead by up to 100 times" [15], moving timelines for practical quantum computing substantially forward.

Major hardware roadmaps indicate rapid scaling, with IBM planning "quantum-centric supercomputers with 100,000 qubits by 2033" [15] and PsiQuantum set to build systems "10 thousand times the size of Willow" by the end of the decade [8].

Experimental Demonstrations of Quantum Advantage

Several recent experiments have demonstrated tangible progress toward quantum advantage in chemical simulation:

In March 2025, "IonQ and Ansys achieved a significant milestone by running a medical device simulation on IonQ's 36-qubit computer that outperformed classical high-performance computing by 12 percent—one of the first documented cases of quantum computing delivering practical advantage over classical methods in a real-world application" [15].

Google's Quantum Echoes algorithm demonstrated "the first-ever verifiable quantum advantage running the out-of-order time correlator algorithm, which runs 13,000 times faster on Willow than on classical supercomputers" [15].

Pharmaceutical applications have shown particular promise, with Google's collaboration with Boehringer Ingelheim demonstrating "quantum simulation of Cytochrome P450, a key human enzyme involved in drug metabolism, with greater efficiency and precision than traditional methods" [15].

Table 3: Recent Experimental Demonstrations of Quantum Utility

| Experiment/Organization | System Simulated | Quantum Hardware | Performance vs. Classical | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IonQ & Ansys | Medical device simulation | 36-qubit trapped ion | 12% faster than classical HPC | 2025 |

| Google Quantum AI | Out-of-order time correlator | Willow (105 qubits) | 13,000x faster | 2025 |

| Google & Boehringer Ingelheim | Cytochrome P450 enzyme | N/A (Algorithmic advance) | Greater efficiency and precision | 2025 |

| QuEra | Magic state distillation | Neutral-atom processor | 8.7x reduction in qubit overhead | 2025 |

| PsiQuantum & Phasecraft | Crystal materials simulation | N/A (Algorithmic advance) | 200x algorithm improvement | 2024-2025 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Simulation

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | Hybrid quantum-classical ground state calculation | Quantum chemistry applications, small molecules |

| Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) | High-accuracy energy and property calculation | Requires fault-tolerant quantum computers |

| Quantum Embedding Methods | Combine quantum and classical computational resources | VQE-in-DFT for complex systems |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Improve results from noisy quantum processors | Zero-Noise Extrapolation, Probabilistic Error Cancellation |

| Magic State Distillation | Enable universal fault-tolerant quantum computation | Recent demonstration by QuEra (2025) |

| Trotterized MERA | Simulation of strongly-correlated quantum many-body systems | Critical spin chains, lattice models |

| Quantum-as-a-Service (QaaS) | Cloud access to quantum processing units | IBM Quantum, Amazon Braket, Microsoft Azure Quantum |

| 3-(1,3-Dithian-2-yl)pentane-2,4-dione | 3-(1,3-Dithian-2-yl)pentane-2,4-dione, CAS:100596-16-5, MF:C9H14O2S2, MW:218.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Methoxy-4-propylcyclohexan-1-ol | 2-Methoxy-4-propylcyclohexan-1-ol, CAS:23950-98-3, MF:C10H20O2, MW:172.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The exponential wall facing classical computational methods for strongly correlated systems represents both a fundamental scientific challenge and a compelling opportunity for quantum computing. While DFT and correlated classical methods will continue to serve important roles for weakly correlated systems, their systematic failures in strongly correlated regimes highlight the need for a fundamentally different computational paradigm.

Quantum computing offers a pathway beyond these limitations by directly exploiting quantum mechanical principles to simulate quantum systems. Recent advances in hardware capabilities, error correction, and quantum algorithms have substantially accelerated the timeline for practical quantum advantage in chemical simulation. As one 2025 assessment concluded, "useful quantum computing is inevitable—and increasingly imminent" [8].

The transition from discovery to design in materials science and drug development represents one of the most promising applications of quantum computing. As articulated by Playground Global partner Peter Barrett, "We are living in a world without quantum materials, oblivious to the unrealized potential and abundance that lie just out of sight. With large-scale quantum computers on the horizon and advancements in quantum algorithms, we are poised to shift from discovery to design, entering an era of unprecedented dynamism in chemistry, materials science, and medicine" [8].

For researchers navigating this transition, hybrid quantum-classical approaches and quantum embedding methods offer near-term strategies for exploring quantum advantage, while continued development of error correction and fault-tolerant architectures promises more comprehensive solutions in the coming decade. The exponential wall that has long constrained computational exploration of strongly correlated systems may finally be yielding to a new computational paradigm.

Quantum Mechanics as a Native Framework for Electronic Structure Problems

Quantum mechanics (QM) provides the foundational framework for understanding electronic structure, describing the behavior of electrons in atoms and molecules using principles such as wave-particle duality and quantization [16]. Unlike classical approaches, the quantum mechanical model represents electrons not as particles in fixed orbits but as wave functions occupying three-dimensional probability clouds called orbitals [16]. This native QM framework becomes particularly essential for strongly correlated electron systems, where classical computational methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) often struggle with accurate predictions due to significant electron correlation effects [17] [18]. For quantum chemists and drug development researchers, these strongly correlated systems present formidable challenges in accurately predicting electronic behavior, binding affinities, and reaction pathways—areas where quantum computing promises revolutionary advances [15] [19].

The pursuit of quantum advantage in electronic structure problems represents a paradigm shift in computational chemistry and materials science [15]. As quantum hardware evolves toward practical utility, researchers are developing increasingly sophisticated algorithms to exploit the inherent quantum nature of electronic systems [13] [18]. This guide examines the current landscape of quantum and classical approaches for electronic structure problems, providing detailed experimental protocols and performance comparisons to inform research strategies for investigating strongly correlated systems in pharmaceutical and materials development.

Theoretical Foundations: Quantum vs. Classical Formulations

The Native Quantum Mechanical Framework

The quantum mechanical description of electronic structure originates from the Schrödinger equation, which defines the wave function (ψ) and energy (E) of a system [16]. For electronic structure calculations, the time-independent Schrödinger equation forms the cornerstone:

Ĥψ = Eψ

Where Ĥ represents the Hamiltonian operator corresponding to the total energy of the system [16]. Solving this equation for molecular systems yields atomic orbitals and energy eigenvalues that describe the electronic configuration. The complete quantum framework incorporates several fundamental principles absent from classical descriptions:

- Wave-particle duality: Electrons exhibit both particle-like and wave-like properties [16]

- Quantization: Electronic energy states exist at discrete levels rather than continuous spectra [16]

- Probability distributions: Electron locations are described by probability densities |ψ|² rather than definite trajectories [16]

- Quantum numbers: Four quantum numbers (n, l, mâ‚—, mâ‚›) uniquely define each electron's quantum state [16]

- Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle: Fundamental limitation in simultaneously measuring complementary properties like position and momentum [16]

Classical Computational Approximations

Classical computational methods necessarily introduce approximations to the full quantum mechanical description, with varying degrees of accuracy and computational cost [17]:

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): Replaces the N-electron wave function with electron density as the fundamental variable, incorporating electron correlation through exchange-correlation functionals [17]

- Hartree-Fock (HF) Method: Approximates electrons as independent particles moving in an averaged electrostatic field [17]

- Post-Hartree-Fock Methods: Includes Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2), Configuration Interaction (CI), and Coupled Cluster (CC) theory to address electron correlation more completely [17]

- Hybrid QM/MM Methods: Combines quantum mechanical treatment of reactive regions with molecular mechanics for surrounding environment [17]

Each classical approach represents a trade-off between computational efficiency and accuracy, with the most accurate methods (like CCSD(T)) scaling so steeply with system size that they become prohibitive for large, strongly correlated systems [17].

Table: Comparison of Theoretical Frameworks for Electronic Structure Problems

| Feature | Native Quantum Framework | Classical Computational Approximations |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Description | Wave functions & probability clouds | Wave functions (HF) or electron density (DFT) |

| Electron Correlation | Intrinsically included | Approximated with varying accuracy |

| Computational Scaling | Exponential (exact) | Polynomial to exponential (approximate) |

| Strong Correlation Handling | Theoretically exact | Challenging, requires advanced methods |

| System Size Limitation | Fundamental (hardware-dependent) | Practical (computational resources) |

| Key Strengths | Theoretically rigorous, systematically improvable | Practically implementable, well-established |

| Key Limitations | Resource-intensive, hardware constraints | Approximation-dependent inaccuracies |

Methodological Comparison: Experimental Protocols

Quantum Computing Approaches

Trotterized MERA Variational Quantum Eigensolver (TMERA-VQE)

The TMERA-VQE algorithm represents a hybrid quantum-classical approach specifically designed for strongly correlated quantum many-body systems [13] [10]. The methodology proceeds through these stages:

Problem Mapping: Encode the electronic structure problem into a qubit Hamiltonian using transformations such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev [10]

Ansatz Initialization: Construct the Multiscale Entanglement Renormalization Ansatz (MERA) with tensors constrained to Trotter circuits composed of single-qubit and two-qubit rotations [13]

Layer-by-Layer Building: Systematically build up the MERA layer by layer during initialization to substantially improve convergence [13]

Parameter Optimization: Employ classical optimization routines to minimize the energy expectation value ⟨ψ(θ)|Ĥ|ψ(θ)⟩, where θ represents the variational parameters [10]

Energy Gradient Evaluation: Compute energy gradients using quantum hardware, which is more efficient than classical gradient calculations for MERA structures [13]

The TMERA approach leverages the causal structure of MERA tensor networks, which resemble light cones, enabling efficient evaluation of local observables like energy densities with relatively few qubits [10]. Benchmark simulations indicate that the specific structure of the Trotter circuits (brick-wall vs. parallel random-pair circuits) has minimal impact on energy accuracy [13].

Programmable Quantum Simulation of Spin Hamiltonians

For complex molecular systems with strong electron correlation, an alternative approach maps the electronic structure problem onto model spin Hamiltonians that are more amenable to quantum simulation [18]. The experimental protocol involves:

Hamiltonian Design: Construct effective spin Hamiltonian describing the low-energy physics of the correlated electronic system: H = Σᵢ,α BᵢαŜᵢα + Σᵢⱼ,αβ JᵢⱼαβŜᵢαŜⱼβ + higher-order terms [18]

Cluster Encoding: Encode spin-S variables into the collective spin of 2S qubits: Ŝᵢα = Σâ‚=1²Sáµ¢ Åáµ¢,â‚α [18]

Dynamical Floquet Engineering: Apply a K-step sequential evolution under simpler interaction Hamiltonians Hᵢ = Σg∈Gᵢ hᵢ,g to realize the effective Floquet Hamiltonian H_F that approximates the target Hamiltonian [18]

Symmetry Projection: Alternately apply evolution under the projection Hamiltonian H_P = λΣᵢ(1-P[(Ŝᵢ)]) to maintain the system in the symmetric subspace [18]

Many-Body Spectroscopy: Extract spectral information through time dynamics and snapshot measurements, enabling evaluation of excitation energies and finite-temperature susceptibilities [18]

This approach has been successfully applied to polynuclear transition-metal catalysts and two-dimensional magnetic materials, demonstrating the ability to capture complex quantum correlations that challenge classical methods [18].

Classical Computational Methods

Advanced Quantum Chemistry Protocols

Traditional computational chemistry employs a hierarchy of methods with increasing accuracy and computational cost [17]:

System Preparation:

- Generate molecular geometry from experimental data or preliminary calculations

- Define basis set appropriate for the system (e.g., cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ)

Method Selection:

- Density Functional Theory: Select exchange-correlation functional (e.g., B3LYP, PBE0) with empirical dispersion corrections (DFT-D3, DFT-D4) for non-covalent interactions [17]

- Coupled Cluster Theory: Employ CCSD(T) as the "gold standard" for highest accuracy, when computationally feasible [17]

- Multireference Methods: Use complete active space SCF (CASSCF) and related approaches for strongly correlated systems with near-degeneracies [17]

Property Calculation:

- Solve the electronic Schrödinger equation self-consistently

- Compute electronic energies, molecular orbitals, and other properties

- Perform vibrational frequency analysis to confirm stationary points

Result Validation:

- Compare with experimental data when available

- Perform convergence tests with respect to basis set size

- Apply error estimation techniques for DFT functionals

Quantum-Classical Hybrid Methods

For large biological systems, hybrid QM/MM protocols divide the system [17]:

System Partitioning: Define QM region (active site, reacting molecules) and MM region (protein scaffold, solvent)

Multiscale Simulation:

- Treat QM region with quantum chemical methods (DFT, CASSCF)

- Treat MM region with molecular mechanics force fields

- Implement electrostatic embedding between regions

Dynamics Simulation: Employ molecular dynamics to sample configurations

Property Averaging: Calculate ensemble-averaged properties from trajectory analysis

Performance Comparison: Quantum Advantage Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table: Computational Performance Comparison for Strongly Correlated Systems

| Method | Accuracy (kcal/mol) | Computational Scaling | Strong Correlation Capability | Qubit Requirements | Circuit Depth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMERA-VQE | ~1-3 (estimated) | Polynomial quantum advantage [13] | Excellent [10] | O(100) for meaningful problems [13] | 5,000-15,000 gates (Nighthawk) [20] |

| Programmable Spin Sims | ~2-5 (estimated) | Efficient for specific models [18] | Excellent for spin systems [18] | Varies with spin complexity [18] | Architecture-dependent [18] |

| DFT (Hybrid Functionals) | 3-5 (varies widely) | O(N³)-O(Nâ´) | Poor to moderate [17] | N/A | N/A |

| Coupled Cluster (CCSD(T)) | 0.5-1 (gold standard) | O(Nâ·) | Good but limited by cost [17] | N/A | N/A |

| DMRG (Classical) | 1-2 (for 1D systems) | Exponential in entanglement | Excellent for 1D systems [10] | N/A | N/A |

Demonstrated Quantum Advantages

Recent experimental results demonstrate tangible progress toward practical quantum advantage in electronic structure problems:

Google's Willow Quantum Chip: Demonstrated exponential error reduction with 105 superconducting qubits, completing a benchmark calculation in approximately five minutes that would require a classical supercomputer 10²ⵠyears to perform [15]

IonQ Medical Device Simulation: Executed a medical device simulation on a 36-qubit computer that outperformed classical high-performance computing by 12%—one of the first documented cases of quantum computing delivering practical advantage in a real-world application [15]

IBM Quantum Roadmap: The newly announced IBM Quantum Nighthawk processor, expected by end of 2025, will enable circuits with 30% more complexity, supporting up to 5,000 two-qubit gates—fundamental entangling operations critical for quantum computation of electronic structure [20]

Algorithmic Fault Tolerance: Recent breakthroughs have pushed error rates to record lows of 0.000015% per operation, with algorithmic fault tolerance techniques reducing quantum error correction overhead by up to 100 times [15]

Application-Specific Performance

Table: Performance Across Chemical System Types

| System Type | Best Quantum Method | Best Classical Method | Relative Quantum Performance | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Catalysts | Programmable spin Hamiltonians [18] | CASSCF/NEVPT2 | Superior for strongly correlated active sites [18] | Hamiltonian parameterization |

| Polynuclear Metal Complexes | TMERA-VQE [10] | DMRG/CASPT2 | Polynomial quantum advantage [13] | Qubit connectivity |

| Organic Photoredox Catalysts | Variational Quantum Deflation [19] | TD-DFT/EOM-CCSD | Promising for excited states [19] | Dynamic correlation |

| Enzyme Active Sites | QM/MM with quantum computing [17] | QM/MM with DFT | Early stage but promising [17] | Embedding schemes |

| 2D Materials | Floquet-engineered simulations [18] | Periodic DFT+U | Potential for breakthrough [18] | Long-range interactions |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Quantum Programming Platforms

Table: Essential Software Tools for Quantum Electronic Structure Research

| Tool | Function | Key Features | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qiskit | Quantum algorithm development [19] | Web-based GUI, smaller code size, IBM hardware access [19] | Education, initial algorithm development [19] |

| PennyLane | Quantum machine learning [19] | Automatic differentiation, multiple hardware backends, machine learning integration [19] | Research, parameter optimization [19] |

| OpenFermion | Electronic structure to qubit mapping | Molecular data structures, Jordan-Wigner transformation | Quantum chemistry applications |

| VQE Algorithms | Ground state energy calculation | Variational principle, hybrid quantum-classical approach | Molecular ground states [19] |

| QM/MM Packages | Multiscale simulations | QM region with quantum methods, MM with force fields | Large biological systems [17] |

| 2,4-Bis(bromomethyl)-1,3,5-triethylbenzene | 2,4-Bis(bromomethyl)-1,3,5-triethylbenzene | RUO | High-purity 2,4-Bis(bromomethyl)-1,3,5-triethylbenzene for chemical synthesis & materials science. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Muscone | Muscone, CAS:10403-00-6, MF:C16H30O, MW:238.41 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Hardware Platforms

Experimental Workflow Integration

For researchers integrating quantum methods into electronic structure investigations, the following workflow represents current best practices:

Problem Assessment: Determine whether the system exhibits strong correlation that justifies quantum approaches

Method Selection: Choose between full electronic structure calculation or effective Hamiltonian approaches based on system size and complexity

Resource Allocation: Balance quantum and classical resources based on availability and problem requirements

Validation Strategy: Implement cross-validation with classical methods where possible

Result Interpretation: Translate quantum processor outputs to chemically meaningful information

The quantum mechanical framework provides the most fundamental and native description of electronic structure problems, particularly for strongly correlated systems that challenge classical computational methods. Current evidence demonstrates that quantum computing approaches are rapidly advancing toward practical quantum advantage, with:

Hardware Progress: IBM's Nighthawk processor (2025) and planned developments through 2028 will enable increasingly complex quantum circuits with up to 15,000 gates [20]

Algorithmic Innovations: TMERA-VQE and programmable spin simulations show polynomial quantum advantage for critical systems [13] [18]

Application-Specific Advances: Quantum methods already show superior performance for specific problems like transition metal catalysts and frustrated spin systems [18]

Software Ecosystem: Mature programming platforms like Qiskit and PennyLane continue to lower barriers for researcher adoption [19]

For researchers in pharmaceutical development and materials science, the native quantum mechanical framework offers a promising path forward for tackling electronic structure problems that remain intractable to classical computational methods. While classical approximations will continue to play important roles for weakly correlated systems, quantum computing approaches are positioned to deliver increasing advantages for strongly correlated systems central to catalyst design, functional materials development, and fundamental chemical understanding.

Strongly-correlated quantum many-body systems represent one of the most challenging frontiers in computational physics and chemistry. These systems, where particles interact in complex ways, exhibit remarkable phenomena like high-temperature superconductivity and fractional quantum Hall effects. Classical computers struggle to simulate them because the computational resources required grow exponentially with system size. This same exponential complexity plagues computational drug discovery, particularly in predicting how small molecule drugs interact with biological targets at the quantum mechanical level. Quantum computing offers a promising pathway to overcome these limitations by providing a natural platform for simulating quantum systems. This guide examines how emerging quantum algorithms are tackling both fundamental physics problems and practical pharmaceutical challenges, objectively comparing their performance against established classical methods.

The potential for quantum advantage—where quantum computers solve problems intractable for classical counterparts—is particularly strong for strongly-correlated systems. Research indicates that variational quantum algorithms applied to critical spin chains can achieve polynomial quantum advantage over classical simulations, with this advantage expected to grow substantially for higher-dimensional systems [13]. In drug discovery, quantum kernels have demonstrated significant improvements in predicting drug-target interactions (DTI), achieving accuracies exceeding 94% on benchmark datasets compared to classical machine learning approaches [21]. These advances suggest we are approaching a transformative period where quantum computation could revolutionize how we understand complex quantum matter and design life-saving therapeutics.

Performance Comparison: Quantum vs. Classical Approaches

Quantum Many-Body System Simulations

Table 1: Performance Comparison for Quantum Many-Body Systems

| Method | System Type | Key Metric | Performance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trotterized MERA VQE [13] | Critical Spin Chains | Computational Cost Scaling | Polynomial quantum advantage | Current hardware limitations |

| Classical MERA (Exact Energy Gradients) | Critical Spin Chains | Computational Cost Scaling | Higher classical cost | Exponential scaling for higher dimensions |

| Quantum Embedding Theory [22] | Spin Defects in Solids | Accuracy vs Experiment | Good agreement for diamond & silicon carbide | Requires classical post-processing |

| Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG) | 1D Quantum Systems | Accuracy | High for 1D systems | Struggles with higher dimensions |

Drug-Target Interaction Prediction

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Drug-Target Interaction Prediction

| Method | Dataset | Accuracy | R² Score | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QKDTI (Quantum Kernel) [21] | DAVIS | 94.21% | N/A | Superior generalization |

| QKDTI (Quantum Kernel) [21] | KIBA | 99.99% | N/A | Handles high-dimensional data |

| Classical SVM [21] | DAVIS | Lower than QKDTI | N/A | Limited by manual feature engineering |

| Deep Learning Models [21] | KIBA | Lower than QKDTI | N/A | Requires large labeled datasets |

| Hybrid Quantum-Classical [21] | BindingDB | 89.26% | N/A | Balanced performance & efficiency |

| Classical Random Forest [21] | Various | Moderate | N/A | Struggles with complex biochemical data |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Trotterized MERA for Quantum Many-Body Systems

The Trotterized Multiscale Entanglement Renormalization Ansatz (TMERA) approach represents a significant advancement for simulating strongly-correlated quantum many-body systems on quantum hardware. The methodology involves:

System Preparation: The algorithm begins by initializing a quantum register representing the physical spins of the system. For a critical spin chain, each qubit typically corresponds to a single spin site.

Layer-by-Layer MERA Construction: Unlike classical approaches that optimize the entire network simultaneously, TMERA builds up the MERA structure layer by layer during initialization. This sequential approach substantially improves convergence by providing better initial parameters for the variational optimization [13].

Trotterized Circuit Implementation: The MERA tensors are constrained to Trotter circuits composed of single-qubit rotations (Rx, Ry, Rz) and two-qubit entangling gates. Research indicates that the specific structure of these Trotter circuits (e.g., brick-wall vs. random-pair) is not decisive for final accuracy, providing flexibility in implementation [13].

Variational Optimization: The system employs a variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) approach to minimize the energy of the quantum state. Substantial improvements in convergence are achieved by scanning through the phase diagram during optimization rather than using random initialization [13].

Measurement and Error Mitigation: The quantum system is measured repeatedly to obtain the expectation values of the Hamiltonian. For current noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, error mitigation techniques are crucial for obtaining accurate results, though TMERA demonstrates inherent resilience to certain types of noise [13].

Quantum Kernel Drug-Target Interaction (QKDTI) Prediction

The QKDTI framework implements a sophisticated quantum-enhanced pipeline for predicting drug-target binding affinities:

Data Preprocessing: Molecular structures and protein sequences from benchmark datasets (DAVIS, KIBA, BindingDB) are converted into feature vectors using classical molecular descriptor algorithms. This step ensures compatibility with quantum feature mapping.

Quantum Feature Mapping: Classical features are encoded into quantum states using parameterized quantum circuits with RY and RZ rotation gates. This mapping transforms classical data into a high-dimensional quantum feature space, capturing nonlinear relationships that are challenging for classical kernels [21].

Quantum Kernel Estimation: The framework employs Quantum Support Vector Regression (QSVR) with a kernel matrix computed from the quantum feature states. The kernel values represent the inner products between quantum feature vectors, effectively capturing complex molecular interaction patterns through quantum interference and entanglement [21].

Nyström Approximation: To address computational bottlenecks, the method integrates the Nyström approximation for efficient kernel matrix completion. This technique reduces the quantum computational overhead while maintaining predictive accuracy, making the approach feasible for current quantum hardware [21].

Hybrid Quantum-Classical Optimization: The model parameters are optimized using a classical optimizer that minimizes the difference between predicted and experimental binding affinities. This hybrid approach leverages quantum processing for feature space transformation and classical processing for parameter optimization [21].

Validation and Statistical Testing: The model undergoes rigorous evaluation using train-test splits and statistical tests (e.g., t-tests) to ensure reliability of the reported performance improvements over classical baselines [21].

Visualization of Methodologies

TMERA Workflow for Quantum Many-Body Systems

TMERA Workflow: This diagram illustrates the hybrid quantum-classical workflow for simulating many-body systems using Trotterized MERA, highlighting the interaction between quantum processing and classical optimization.

QKDTI Framework for Drug Discovery

QKDTI Framework: This visualization shows the quantum-enhanced pipeline for drug-target interaction prediction, demonstrating the integration of classical preprocessing with quantum feature mapping and kernel estimation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Quantum Simulation and Drug Discovery

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) [13] | Algorithm | Finds ground states of quantum systems | Quantum many-body systems, molecular simulation |

| Quantum Embedding Theory [22] | Methodological Framework | Couples quantum and classical computation | Simulating spin defects in complex materials |

| Quantum Support Vector Regression (QSVR) [21] | Quantum ML Algorithm | Regression in quantum feature spaces | Drug-target binding affinity prediction |

| Nyström Approximation [21] | Computational Technique | Reduces kernel computation overhead | Scalable quantum kernel methods |

| Hybrid Shadow Estimation [23] | Quantum Measurement | Measures nonlinear functions of quantum states | State moment estimation, quantum error mitigation |

| Quantum Feature Mapping [21] | Data Encoding | Encodes classical data into quantum states | Molecular descriptor transformation for QML |

| Trotterized Circuits [13] | Quantum Circuit Design | Approximates complex unitaries with simpler gates | Efficient implementation of MERA tensors |

| Randomized Measurements [23] | Quantum Protocol | Extracts information from quantum states | Resource-efficient quantum characterization |

| Bis(1,3-dimethylbutyl) maleate | Bis(1,3-dimethylbutyl) maleate|284.39 g/mol|CAS 105-52-2 | Bis(1,3-dimethylbutyl) maleate is a chemical intermediate and plasticizer for polymer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-Chloro-4-methylpyrimidin-5-amine | 2-Chloro-4-methylpyrimidin-5-amine|CAS 20090-69-1 | Bench Chemicals |

Discussion: Performance Analysis and Future Directions

The comparative data reveals distinct performance patterns across problem classes. For quantum many-body systems, the advantage appears in computational scaling rather than immediate accuracy gains. The Trotterized MERA approach demonstrates polynomial quantum advantage for critical spin chains, suggesting that as system size and dimensionality increase, the quantum approach will increasingly outperform classical methods [13]. This scaling advantage is crucial for tackling realistic materials and quantum chemistry problems that remain intractable for classical supercomputers.

In drug-target interaction prediction, quantum methods demonstrate immediate accuracy improvements on benchmark datasets. The QKDTI framework's exceptional performance (94.21% on DAVIS, 99.99% on KIBA) suggests that quantum kernels can capture complex molecular interaction patterns that elude classical machine learning models [21]. This advantage stems from quantum computers' ability to naturally represent high-dimensional feature spaces and capture nonlinear relationships through quantum interference and entanglement.

However, both applications face the challenge of NISQ-era limitations. Current quantum devices suffer from noise, decoherence, and qubit connectivity constraints that restrict problem sizes and circuit depths. Quantum error mitigation techniques and hybrid quantum-classical approaches provide promising pathways to extract value from current hardware while awaiting fully fault-tolerant quantum computers [24] [22]. The development of application-specific hardware, such as neutral-atom quantum computers mentioned in business contexts, may also accelerate practical adoption [25].

The convergence of these fields is particularly promising. Methods developed for quantum many-body systems, such as tensor networks and entanglement renormalization, are informing new approaches to molecular simulation [13]. Conversely, quantum chemistry simulations are serving as testbeds for developing more efficient quantum algorithms. This cross-pollination suggests that future breakthroughs will likely emerge at the intersection of these seemingly disparate problem classes, unified by their shared foundation in quantum mechanics and their computational complexity.

Quantum Algorithmic Toolkit: From VQE to Real-World Drug Pipelines

The simulation of strongly correlated quantum systems represents a grand challenge in computational chemistry and materials science, critical for advancing research in areas such as catalyst and drug development. Classical computational methods, including Density Functional Theory (DFT) and conventional coupled cluster (CC) theory, often struggle with the exponential scaling and accuracy required for these systems [26]. Quantum computing offers a promising pathway, with the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) emerging as a leading algorithm for near-term noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices [27] [28]. VQE operates on a hybrid quantum-classical principle, using a quantum processor to prepare parameterized trial wavefunctions and a classical computer to optimize them [29]. Within the VQE framework, the choice of "ansatz"—the parameterized wavefunction form—is paramount. The Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) ansatz, inspired by classical quantum chemistry, is a standard but computationally expensive choice [27] [30]. The Qubit Coupled Cluster (QCCSD) ansatz is a more recent alternative designed to reduce circuit complexity and improve feasibility on current hardware [31]. This guide provides a objective comparison of the VQE and QCCSD paradigms, focusing on their performance, resource requirements, and applicability to strongly correlated systems.

Algorithmic Fundamentals and Theoretical Frameworks

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) Framework

VQE is a hybrid algorithm designed to find the ground-state energy of a quantum system, such as a molecule, by minimizing the expectation value of its Hamiltonian. The algorithm proceeds as follows [27] [29]:

- Problem Encoding: The electronic Hamiltonian from the Schrödinger equation, typically in its second-quantized form, is mapped to a qubit Hamiltonian using a transformation like Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev. The result is a Hamiltonian expressed as a sum of Pauli strings.

- Ansatz Preparation: A parameterized quantum circuit (the ansatz) prepares a trial wavefunction from an initial reference state, often the Hartree-Fock state.

- Measurement and Classical Optimization: The expectation value of the Hamiltonian is measured on the quantum computer. A classical optimizer adjusts the ansatz's parameters to minimize this expectation value, iterating until convergence.

The standard UCCSD ansatz for VQE uses fermionic excitation operators, but its circuit depth is often prohibitive for NISQ devices, sparking the development of more efficient variants like ADAPT-VQE and unitary Cluster Jastrow (uCJ) [26] [30].

The Qubit Coupled Cluster (QCCSD) Formulation

QCCSD represents a different approach by constructing the ansatz directly at the qubit level. Instead of using fermionic excitation operators that are then mapped to qubits, QCCSD utilizes the particle preserving exchange gate to achieve qubit excitations [31]. This method circumvents the need for extra terms required by fermionic excitations under transformations like Jordan-Wigner. The gate complexity of the QCCSD ansatz is bounded by (O(n^4)), where (n) is the number of qubits, making it a computationally efficient alternative for electronic structure calculations [31].

Performance and Resource Analysis

The table below summarizes a direct comparison of key performance metrics between the standard VQE-UCCSD ansatz and the QCCSD ansatz based on documented studies.

Table 1: Direct performance comparison between VQE-UCCSD and QCCSD ansätze

| Feature | VQE with UCCSD Ansatz | Qubit Coupled Cluster (QCCSD) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Foundation | Fermionic excitations (chemistry-inspired) [27] | Qubit excitations via particle preserving gates [31] |

| Ansatz Construction | Based on single and double excitations from Hartree-Fock reference [27] | Direct qubit-based excitations [31] |

| Gate Complexity | High; scaling challenges for deep circuits [27] | (O(n^4)) [31] |

| Accuracy (in Hartree) | High accuracy but can be limited by approximations [30] | Errors within (\sim 10^{-3}) for small molecules [31] |

| Notable Applications | H₂, LiH, BeH₂, H₂O [30] [28] | BeH₂, H₂O, N₂, H₄, H₆ [31] |

| 1-Nitro-2-(trifluoromethoxy)benzene | 1-Nitro-2-(trifluoromethoxy)benzene CAS 1644-88-8 | |

| 4-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethylbenzonitrile | 4-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethylbenzonitrile, CAS:4198-90-7, MF:C9H9NO, MW:147.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced VQE Variants and Comparative Data

To address UCCSD's limitations, more advanced VQE ansätze have been developed. The following table compares several of these state-of-the-art approaches.

Table 2: Comparison of advanced VQE ansätze for strongly correlated systems

| Ansatz Type | Key Principle | Advantages | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADAPT-VQE [30] | Iteratively builds ansatz from an operator pool using gradient criteria. | More compact circuits, higher accuracy for strong correlation. | Achieves chemical accuracy with fewer parameters than UCCSD [30]. |

| unitary Cluster Jastrow (uCJ) [26] | Uses exponentials of one-electron and number operators (Jastrow factors). | (O(kN^2)) scaling; shallow, exact circuit implementation. | Frequently maintains energy errors within chemical accuracy; more expressive than UCCSD for some systems [26]. |

| Gradient-Based Excitation Filter (GBEF) [32] | Classically pre-filters UCCSD excitations using Hartree-Fock gradients. | Up to 60% circuit depth reduction vs. ADAPT-VQE; avoids quantum measurement overhead. | Up to 46% parameter decrease and (678\times) runtime speedup reported [32]. |

VQE Algorithm Workflow

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard VQE-UCCSD Simulation Protocol

A typical protocol for conducting a molecular simulation using the VQE-UCCSD method involves these key steps [30] [29]:

- Molecular Specification and Hamiltonian Generation:

- Define the molecular geometry (atomic species and positions) and choose a basis set.

- Classically compute the electronic Hamiltonian in second-quantized form using the Hartree-Fock method, which provides the one- and two-electron integrals ((h{pq}) and (h{pqrs})).

- Qubit Encoding and Tapering:

- Transform the fermionic Hamiltonian into a qubit Hamiltonian using a mapping (e.g., Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev).

- Apply qubit tapering to reduce the problem size by exploiting molecular symmetries, which removes qubits associated with conserved quantities.

- Ansatz Preparation and Circuit Execution:

- Prepare the Hartree-Fock state on the quantum processor.

- Apply the UCCSD ansatz circuit, typically using a first-order Trotter decomposition to approximate the exponential of the cluster operator.

- Measure the expectation values of the Pauli terms constituting the Hamiltonian.

- Classical Optimization:

- Use a classical optimizer (e.g., gradient descent, SPSA) to minimize the total energy.

- Iterate until convergence to a minimum energy, which is reported as the ground-state energy.

ADAPT-VQE Protocol for Strong Correlation

The ADAPT-VQE protocol modifies the standard VQE by dynamically growing the ansatz [30] [32]:

- Initialization: Start with a simple initial state, such as the Hartree-Fock state.

- Operator Pool Definition: Define a pool of operators, often the entire set of UCCSD fermionic excitations or a set of Pauli strings (qubit-ADAPT).

- Gradient Evaluation and Operator Selection: At each iteration, compute the energy gradient with respect to every operator in the pool. The operator with the largest gradient magnitude is selected.

- Ansatz Expansion and Optimization: Append the selected operator (as a parameterized gate) to the circuit. Re-optimize all parameters in the now-expanded ansatz.

- Convergence Check: Repeat steps 3 and 4 until the energy converges or the largest gradient falls below a predefined threshold.

A "batched" version of this protocol adds multiple high-gradient operators per iteration to reduce the number of costly gradient measurement rounds [30].

QCCSD Energy Estimation Protocol

The protocol for QCCSD simulations shares the initial steps with VQE but differs in ansatz implementation [31]:

- Hamiltonian Preparation: This step is identical to VQE: generate the qubit Hamiltonian via a chosen mapping.

- Qubit Excitation-Based Ansatz: Instead of deploying a fermionic UCCSD ansatz, the quantum circuit is constructed using the QCCSD formalism, which employs particle-preserving exchange gates to create the entangled trial state.

- Variational Optimization: The energy is measured and optimized classically, similar to the standard VQE procedure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This section details key computational "reagents" and resources essential for conducting research with VQE and QCCSD.

Table 3: Essential research reagents for VQE and QCCSD simulations

| Tool/Resource | Function | Role in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Basis Set [29] | A set of basis functions (e.g., STO-3G, 6-31G*) used to represent molecular orbitals. | Defines the accuracy and size of the Hamiltonian; determines the number of qubits required. |

| Qubit Mapping [27] [29] | A transformation (e.g., Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev, Parity) to map fermionic operators to qubit (Pauli) operators. | Encodes the quantum chemistry problem onto the qubit register of a quantum processor. |

| Operator Pool [30] | A predefined set of operators (e.g., all UCCSD excitations) from which an ansatz is built. | Serves as the "library" of building blocks for adaptive ansätze like ADAPT-VQE. |

| Classical Optimizer [29] | An algorithm (e.g., COBYLA, SPSA, BFGS) for minimizing the energy with respect to ansatz parameters. | The classical "engine" that drives the hybrid loop towards the ground state. |

| Error Mitigation Techniques [28] | Procedures (e.g., zero-noise extrapolation, symmetry verification) to reduce the impact of hardware noise. | Crucial for obtaining physically meaningful results from noisy near-term quantum devices. |

| 3,7-Dipropyl-3,7-diazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane | 3,7-Dipropyl-3,7-diazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane, CAS:909037-18-9, MF:C13H26N2, MW:210.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1,1-Diethyl-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)urea | 1,1-Diethyl-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)urea, CAS:56015-84-0, MF:C12H18N2O2, MW:222.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

For researchers targeting strongly correlated systems, the choice between VQE and QCCSD is not a simple binary. The standard VQE-UCCSD ansatz provides a chemically intuitive framework but faces significant scalability challenges on NISQ hardware. The QCCSD approach offers a promising reduction in circuit complexity and has demonstrated high accuracy for small molecules, making it a compelling candidate for near-term experiments [31]. However, the rapid evolution of VQE has produced more sophisticated ansätze like ADAPT-VQE and uCJ, which show superior performance in capturing strong correlation with shallower circuits [26] [30]. Emerging techniques like GBEF that classically pre-process the ansatz further push the boundaries of feasibility [32].

The future path toward a practical quantum advantage in drug development and materials science will likely involve a co-design of algorithms and hardware. Promising directions include quantum embedding methods like VQE-in-DFT, which simulates only a strongly correlated fragment on the quantum processor while treating the larger environment with classical methods [14], and the use of downfolding techniques to create more efficient effective Hamiltonians [33]. For now, researchers should consider QCCSD and advanced VQE variants like ADAPT-VQE and uCJ as the leading algorithmic paradigms for exploring strongly correlated systems on developing quantum hardware.

The accurate simulation of strongly correlated systems represents one of the most anticipated applications of quantum computing, with profound implications for drug discovery, materials science, and fundamental physics. These systems, where quantum entanglement and electron correlations dominate, often defy accurate description by classical computational methods due to the exponential scaling of their state space. At the heart of variational quantum algorithms lies the ansatz—a parameterized quantum circuit that prepares trial wavefunctions—whose design critically determines both computational efficiency and accuracy. The fundamental challenge in noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) era is crafting ansätze that simultaneously achieve chemical accuracy, hardware efficiency, and noise resilience.

Two innovative approaches have recently emerged to address this challenge: Seniority-informed Unitary Ranking and Guided Evolution (SURGE) and Trotterized Multiscale Entanglement Renormalization Ansatz (TMERA). While SURGE leverages chemical intuition and seniority-zero excitations to build dynamic, resource-efficient ansätze for molecular systems, TMERA adapts classical tensor network structures to quantum hardware through Trotterized circuits for condensed matter applications. This comparison guide examines their respective methodological frameworks, performance characteristics, and implementation requirements, providing researchers with the data needed to select appropriate ansatz strategies for strongly correlated systems across scientific domains.

Methodological Frameworks: A Comparative Analysis

Seniority-Driven Operator Selection (SURGE-VQE)

The SURGE-VQE approach introduces an algorithmic framework that strategically leverages the quantum chemical concept of "seniority"—which counts the number of unpaired electrons in a determinant—to efficiently capture strong correlation in molecular systems [34] [35]. Traditional unitary coupled cluster methods often incorporate numerous unnecessary excitations that inflate circuit depth without meaningfully contributing to correlation energy. SURGE addresses this inefficiency through a fundamental redesign of operator selection and ansatz construction.