Validating Quantum Chemistry Methods for Reaction Pathways: From Theory to Drug Discovery Applications

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to validate quantum chemistry methods for modeling reaction pathways.

Validating Quantum Chemistry Methods for Reaction Pathways: From Theory to Drug Discovery Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to validate quantum chemistry methods for modeling reaction pathways. It explores the foundational principles of key methods like ROHF and CASSCF, details their practical application in calculating energy barriers and free energy profiles, and addresses common computational challenges through advanced optimization techniques. A comparative analysis validates the performance of traditional, emerging Riemannian, and hybrid quantum-classical methods against experimental data, offering actionable insights for their reliable integration into biomedical research and drug design workflows.

Core Principles: Understanding Quantum Chemistry Methods for Reaction Pathways

Computational chemistry provides an indispensable toolkit for studying molecular systems, from predicting spectroscopic properties to elucidating complex reaction mechanisms. [1] For many chemical systems, particularly those with degenerate or nearly degenerate electronic states, single-reference methods like Hartree-Fock (HF) or density functional theory (DFT) prove inadequate as they cannot properly describe static (strong) electron correlation. [2] [1] [3] This limitation is particularly pronounced in excited states, bond-breaking processes, and systems containing transition metals, making multireference approaches essential for electronic spectroscopy and photochemistry. [2]

Two foundational methods for treating such challenging systems are the Restricted Open-Shell Hartree-Fock (ROHF) and Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) methods. ROHF provides a single-reference description for open-shell systems while imposing restrictions on spatial orbitals. CASSCF, in contrast, is a multiconfigurational approach that captures static correlation by performing a full configuration interaction calculation within a carefully selected orbital subspace called the active space. [1] The performance of CASSCF critically depends on active space construction, balancing accuracy with computational feasibility—a challenge that has spurred development of various automated selection protocols. [2]

This guide examines these key electronic structure methods within the context of validating quantum chemistry approaches for reaction pathway research, focusing on objective performance comparisons and practical implementation considerations for researchers in computational chemistry and drug development.

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Restricted Open-Shell Hartree-Fock (ROHF)

ROHF extends the standard HF approach to open-shell systems while maintaining restrictions that ensure all molecular orbitals are doubly occupied except for a defined set of singly-occupied orbitals. [4] This method provides a qualitatively correct single-reference description for systems with unpaired electrons, serving as a common starting point for more sophisticated correlation methods. Recent advances have reformulated ROHF optimization as a problem on Riemannian manifolds, demonstrating robust convergence properties without fine-tuning of numerical parameters. [4]

Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF)

The CASSCF method addresses static correlation by dividing molecular orbitals into three distinct subsets: [1]

- Inactive orbitals: Always doubly occupied

- Active orbitals: Occupancy varies (0-2 electrons); site of multireference character

- Virtual orbitals: Always unoccupied

Within the active space, a full configuration interaction calculation is performed, allowing electrons to distribute among active orbitals in all possible ways consistent with spatial and spin symmetry. [1] Both molecular orbitals and configuration interaction expansion coefficients are variationally optimized in an iterative procedure. For studying multiple electronic states simultaneously, the state-averaged (SA-CASSCF) variant employs a weighted sum of energies from several states to obtain a single set of orbitals balanced for all states of interest. [1]

Table 1: CASSCF Orbital Space Organization

| Orbital Type | Occupancy | Role in Calculation | Electron Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inactive | Always doubly occupied | Core electron description | Excluded from correlation treatment |

| Active | Variable (0-2 electrons) | Static correlation description | Fully correlated within active space |

| Virtual | Always unoccupied | High-energy unoccupied orbitals | Excluded from correlation treatment |

Active Spaces: The Core Challenge in CASSCF

The central challenge in CASSCF calculations is selecting appropriate active orbitals, as the method's accuracy and computational cost depend critically on this choice. [2] The number of configuration state functions grows exponentially with active space size, imposing practical limits of approximately 18 electrons in 18 orbitals in conventional implementations. [1] A "good" active space must capture the essential static correlation while remaining computationally feasible—a balance that requires careful consideration of the chemical system and processes under investigation. [2]

For reaction pathway studies, maintaining consistent active spaces across different molecular geometries presents additional challenges, as orbitals must correspond properly along the entire reaction coordinate to avoid inconsistent correlation energy treatment and erratic behavior of relative energies. [5]

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

Methodological Performance for Different Chemical Systems

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Electronic Structure Methods

| Method | Correlation Treatment | Strengths | Limitations | Optimal Application Domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROHF | None (mean-field) | Robust convergence; good initial guess; proper spin symmetry [4] | Lacks electron correlation; quantitative inaccuracy | Open-shell system initial guess; ROHF-CASSCF initialization [4] |

| CASSCF (minimal active space) | Static only | Qualitative multireference description; applicable to excited states [1] [6] | Overestimates Slater-Condon parameters (10-50%); lacks dynamic correlation [6] | Qualitative studies of dn/fn metal complexes; initial reaction path scans [6] |

| CASSCF (extended active space) | Static only | Superior to minimal active space for static correlation | Exponential scaling; manual selection often required [2] | Small molecule excited states; bond breaking |

| NEVPT2/CASPT2 | Static + Dynamic | Quantitative accuracy; systematic error reduction [2] [6] | Computationally demanding; requires prior CASSCF [6] | Quantitative spectroscopy; accurate barrier heights [2] |

Quantitative Benchmarking Data

Recent benchmarking studies provide quantitative performance data for these methods:

Table 3: Quantitative Accuracy Assessment for Minimal Active Space CASSCF

| System Type | Slater-Condon Parameters | Spin-Orbit Coupling Constants | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3d transition metal ions | Overestimated by 1-50% (erratic) [6] | Overestimated by 5-30% [6] | Qualitative only; dynamic correlation essential [6] |

| 4d/5d transition metal ions | Overestimated by ~10-50% [6] | Within ±10% of experimental [6] | Qualitative spectroscopy; semi-quantitative SO coupling |

| Trivalent 4f ions | Overestimated by ~10-50% [6] | Overestimated by 2-10% [6] | Qualitative studies; systematic scaling possible [6] |

For excited state calculations, automatic active space selection combined with NEVPT2 dynamic correlation correction has shown encouraging results across established datasets of small and medium-sized molecules. [2] The strongly-contracted NEVPT2 (SC-NEVPT2) variant systematically delivers reliable vertical transition energies, only marginally inferior to the partially-contracted scheme. [2]

Automated Active Space Selection Protocols

Selection Algorithms and Their Workflows

The challenge of manual active space selection has prompted development of automated protocols, which generally follow similar conceptual workflows while employing different selection criteria:

Comparative Analysis of Automated Selection Methods

Table 4: Automated Active Space Selection Methods

| Method | Selection Criteria | Initial Wavefunction | Strengths | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Space Finder (ASF) | Natural orbital occupation numbers [2] | UHF/MP2 [2] | A priori selection; minimal CASSCF iterations [2] | ASF software [2] |

| autoCAS | Orbital entanglement entropies [5] [3] | DMRG with low bond dimension [5] [3] | Plateau identification; chemical intuition mimic [5] [3] | autoCAS [5] |

| QICAS | Quantum information measures; entropy minimization [3] | DMRG [3] | Optimized orbitals; reduced CASSCF iterations [3] | QICAS [3] |

| DOS+autoCAS | Orbital mapping along reaction paths [5] | Hartree-Fock or Kohn-Sham [5] | Consistent active spaces along coordinates [5] | Direct Orbital Selection + autoCAS [5] |

Performance of Automated Selection

Benchmarking the Active Space Finder with established datasets shows promising results for excitation energy calculations. [2] Key findings include:

- Automatic selection constructs meaningful molecular orbitals suitable for balanced treatment of multiple electronic states

- Selection based on approximate correlated calculations (e.g., MP2 natural orbitals) provides effective starting points

- Multi-step procedures can tackle the key difficulty of choosing active spaces balanced for several electronic states [2]

The QICAS approach demonstrates that for smaller correlated molecules, optimized orbitals can achieve CASCI energies within chemical accuracy of corresponding CASSCF energies, while for challenging systems like the Chromium dimer, it greatly reduces CASSCF convergence iterations. [3]

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 5: Essential Computational Tools for Electronic Structure Research

| Tool Name | Function/Purpose | Methodology | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASF (Active Space Finder) | Automated active space selection [2] | MP2 natural orbitals; a priori selection [2] | Excited state calculations; balanced active spaces [2] |

| autoCAS | Automated active space construction [5] | DMRG orbital entanglement entropy analysis [5] [3] | General multireference systems; reaction pathways [5] |

| QICAS | Quantum information-assisted optimization [3] | Orbital entropy minimization [3] | Challenging strongly correlated systems [3] |

| Dandelion | Reaction pathway exploration [7] | Multi-level workflow (xTB → DFT) [7] | High-throughput reaction discovery [7] |

| ARplorer | Automated reaction pathway exploration [8] | QM + rule-based + LLM-guided logic [8] | Complex organic/organometallic systems [8] |

| OpenMolcas | Multireference electronic structure calculations [6] | CASSCF-SO; (X)MS-CASPT2 [6] | Spectroscopy; magnetic properties [6] |

Application to Reaction Pathway Research

Consistent Active Spaces Along Reaction Coordinates

For accurate reaction energy profiles, maintaining consistent active orbital spaces across different molecular geometries is essential. [5] The Direct Orbital Selection (DOS) approach combined with autoCAS enables fully automated orbital mapping along reaction coordinates without structure interpolation, identifying valence orbitals that change significantly during reactions. [5] Orbitals involved in bond breaking/formation cannot be unambiguously mapped across all structures and must be included in active spaces to ensure consistent correlation energy treatment. [5]

Workflow for Reaction Pathway Studies

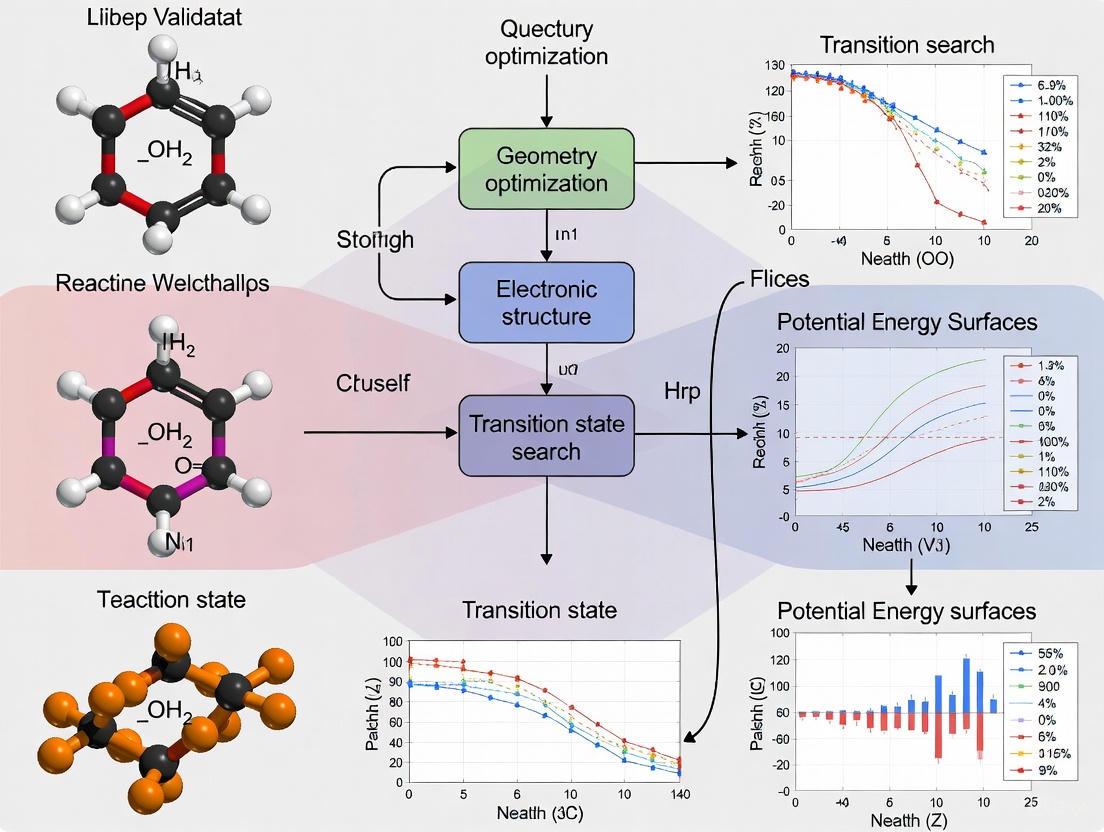

A robust computational workflow for reaction pathway research integrates multiple electronic structure methods:

Case Study: Homolytic Bond Dissociation and Double Bond Rotation

Applying the DOS+autoCAS protocol to 1-pentene demonstrates how automated active space selection handles changing multiconfigurational character along reaction coordinates. [5] For the homolytic carbon-carbon bond dissociation and rotation around the double bond in the electronic ground state, the algorithm successfully identifies and tracks orbitals involved in bond breaking and forming processes, ensuring consistent active spaces across the potential energy profile. [5]

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Automated Active Space Selection with ASF

Based on the Active Space Finder methodology: [2]

- Initial SCF Calculation: Perform spin-unrestricted Hartree-Fock (UHF) calculation with stability analysis and restart if internal instability detected

- Initial Space Selection:

- Compute orbital-unrelaxed MP2 natural orbitals for ground state (density-fitting MP2 recommended)

- Select initial orbital set based on occupation number threshold with upper limit

- Orbital Processing:

- Option A: Propagate MP2 natural orbitals directly

- Option B: Re-canonicalize using projected Fock matrix sub-blocks (QRO-like procedure)

- DMRG Pre-calculation: Perform low-accuracy DMRG calculation with initial active space

- Active Space Determination: Analyze DMRG results to select final active space using implemented algorithms

- Validation: Confirm selection with target CASSCF/NEVPT2 calculation

Protocol: Consistent Active Spaces Along Reaction Paths

Based on the DOS+autoCAS approach: [5]

- Structure Selection: Choose representative molecular structures along reaction coordinate

- Orbital Localization:

- Localize orbitals for one structure (template) using Intrinsic Bond Orbital scheme

- Align all other orbital sets to template by minimizing difference in orbital populations

- Localize all other orbital sets

- Orbital Mapping:

- Calculate orbital kinetic energy and shell-wise IAO populations for all orbitals

- Apply mapping condition (Eq. 1) with similarity threshold Ï„

- Construct orbital set maps between structures

- Orbital Set Classification:

- Identify mappable orbital sets (consistent across all structures)

- Identify nonmatchable orbitals (varying along reaction coordinate)

- Active Space Selection: Include all nonmatchable orbitals in active space; apply autoCAS to select additional orbitals as needed

- Validation: Verify consistent active spaces across reaction path

ROHF and CASSCF represent complementary approaches in the multireference electronic structure toolkit, with ROHF providing robust open-shell reference wavefunctions and CASSCF addressing static correlation through active space selection. The critical importance of appropriate active space choice in CASSCF calculations cannot be overstated, as it fundamentally determines both accuracy and computational feasibility.

Recent advances in automated active space selection protocols show significant promise for black-box application of multireference methods, particularly for reaction pathway studies where consistent orbital spaces across geometries are essential. Performance benchmarks indicate that while minimal active space CASSCF provides valuable qualitative insights, quantitative accuracy requires dynamic correlation correction through methods like NEVPT2 or CASPT2.

For researchers studying reaction mechanisms, particularly in pharmaceutical development where complex molecular transformations involve bond breaking/formation and potentially excited states, the integrated workflow combining automated active space selection with dynamic correlation correction offers a promising path forward. As these methods continue to mature and computational resources grow, their application to increasingly complex chemical systems will further enhance our understanding of reaction pathways and enable more predictive computational chemistry.

The Critical Role of Reaction Pathways in Predicting Chemical Reactivity and Kinetics

Understanding chemical reaction pathways is fundamental to predicting chemical reactivity and kinetics, as these pathways delineate the precise sequence of molecular events from reactants to products, including the formation and breaking of bonds at the transition state. For researchers in pharmaceuticals and materials science, accurately mapping these pathways enables the prediction of reaction rates, selectivity, and yields—critical factors in drug design and material development. Within the context of validating quantum chemistry methods, the accurate computation of reaction pathways serves as a rigorous benchmark for assessing methodological accuracy and transferability. The emergence of large-scale datasets and machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) is now transforming this field, offering new pathways to achieve quantum-level accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, thereby pushing the boundaries of what is computationally feasible in predictive chemistry [9] [10].

This guide provides an objective comparison of contemporary approaches for reaction pathway analysis, focusing on their performance in predicting reactivity and kinetics. We objectively compare emerging methodologies, including high-fidelity datasets, machine learning potentials, and hybrid quantum-classical platforms, by synthesizing current experimental data and detailed protocols to aid researchers in selecting and validating the optimal tools for their investigative workflows.

Comparative Analysis of Modern Reaction Pathway Methods

The performance of different computational approaches can be objectively evaluated based on their accuracy, computational cost, and coverage of chemical space. The table below summarizes key metrics for contemporary datasets and platforms relevant to reaction pathway research.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Quantum Chemistry Datasets and Platforms

| Method / Platform | Chemical Coverage & Specialization | Reported Accuracy (vs. High-Level DFT) | Computational Workflow & Speed | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset & UMA Models [9] | Comprehensive: Biomolecules, electrolytes, metal complexes, organics. 100M+ calculations. | Near-perfect on organic subsets (e.g., WTMAD-2); "Much better energies than affordable DFT" [9]. | Pre-trained Neural Network Potentials (NNPs); enables simulation of "huge systems" [9]. | Large-scale biomolecular modeling, material simulation, catalyst screening. |

| Halo8 Dataset [10] | Specialized in halogen (F, Cl, Br) chemistry. ~20M calculations from 19k pathways. | ωB97X-3c level; 5.2 kcal/mol W-MAE on DIET test set; accurate for halogen interactions [10]. | Multi-level workflow; 110x speedup over pure DFT [10]. | Pharmaceutical discovery (25% of drugs contain F), halogenated materials. |

| QIDO Platform [11] | Hybrid quantum-classical; targets strongly correlated electrons. | InQuanto software claims up to 10x higher accuracy for complex molecules vs. open-source [11]. | Hybrid workflow; classical for most steps, quantum for specific sub-problems. | Reaction pathway analysis, transition-state mapping, battery materials. |

| PESExploration Tool [12] | Automated reaction discovery for molecular and surface systems (e.g., TiO2). | Dependent on underlying quantum method (DFT). | Automated pathway and transition state search; reduces manual effort [12]. | Mechanistic studies, heterogeneous catalysis, surface reactions. |

The data reveals a trend towards specialization and scale. While general-purpose benchmarks like OMol25 provide unprecedented breadth, specialized datasets like Halo8 address critical gaps, such as halogen chemistry, which is prevalent in pharmaceuticals but historically underrepresented in training data [10]. For industrial applications, integrated platforms like QIDO offer a pragmatic hybrid approach, leveraging classical computing for most of the workload while reserving quantum resources for the most challenging electronic structure problems, thus balancing accuracy and practical computational cost [11].

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Multi-Level Reaction Pathway Sampling (Halo8)

The Halo8 dataset employs an efficient, multi-level workflow designed for extensive sampling of reaction pathways, particularly for halogenated systems. The detailed, citable protocol is as follows [10]:

- Reactant Selection and Preparation: Molecules are selected from foundational databases like GDB-13. Halogen diversity is achieved through systematic atom substitution (e.g., Cl replaced with F and Br). Initial 3D structures are generated using RDKit and the MMFF94 force field, followed by geometry optimization using the semi-empirical GFN2-xTB method to ensure chemically reasonable starting conformations [10].

- Product Search and Pathway Exploration: The single-ended growing string method (SE-GSM) is used to explore possible bond rearrangements from the reactant geometry, generating initial guesses for reaction pathways. This step is performed at the GFN2-xTB level to enable rapid screening [10].

- Pathway Refinement with NEB: Promising pathways are refined using Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) calculations with a climbing image to precisely locate transition states. Filtering criteria are applied to ensure chemical validity, including the presence of a single imaginary frequency for the transition state and the exclusion of trivial or repetitious pathways [10].

- High-Accuracy Single-Point Calculations: Finally, selected structures along each validated reaction pathway undergo single-point energy calculations at a higher level of Density Functional Theory (DFT)—specifically ωB97X-3c—to obtain accurate energies, forces, dipole moments, and partial charges for the final dataset [10].

This protocol's key innovation is the separation of low-level sampling and high-level refinement, which achieves a 110-fold speedup compared to a pure DFT workflow, making large-scale reaction pathway exploration computationally feasible [10].

Diagram: Multi-Level Reaction Pathway Workflow

Protocol: Hybrid Quantum-Classical Simulation (QIDO Platform)

For researchers seeking to incorporate quantum computing, the QIDO platform exemplifies a hybrid protocol [11]:

- System Setup and Classical Pre-processing: The reaction system is prepared using QSimulate's QSP Reaction software, which can handle systems involving thousands of atoms with quantum-level accuracy on classical hardware.

- Problem Decomposition: The computational problem is divided, with the majority of the simulation (e.g., geometry optimization, dynamics of the entire system) being executed on powerful classical computers.

- Quantum Subroutine Execution: Specific, computationally intensive sub-problems—such as modeling strongly correlated electrons in an active site—are offloaded to a quantum computer via Quantinuum's InQuanto software. InQuanto interfaces with both quantum simulators and actual H-Series ion-trap quantum hardware.

- Integration and Analysis: The results from the quantum computation are integrated back into the broader classical simulation, enabling reaction pathway analysis, transition-state mapping, and the application of quantum embedding techniques that maintain high accuracy while reducing the overall computational cost.

This hybrid approach allows for the practical application of current quantum computing resources to real-world chemical challenges, providing a pathway to early quantum advantage in industrial discovery pipelines [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details key software tools and computational methods that form the essential "research reagent solutions" for modern reaction pathway studies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Reaction Pathway Studies

| Tool / Method | Function in Reaction Pathway Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) [9] | Provides a fast, accurate surrogate for the quantum mechanical potential energy surface, enabling molecular dynamics and geometry optimizations at quantum-level accuracy. | Used in OMol25-trained models (eSEN, UMA) to simulate large systems like proteins and materials. |

| Dandelion Pipeline [10] | An automated computational workflow for systematic reaction discovery and characterization, integrating SE-GSM and NEB methods. | Core infrastructure for generating the Halo8 dataset; enables high-throughput pathway exploration. |

| PESExploration Module [12] | Automates the discovery of reaction pathways and transition states by systematically mapping the potential energy surface, reducing reliance on chemical intuition. | Applied in mechanistic studies, such as water splitting on TiOâ‚‚ surfaces, within the AMS software suite. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software (ORCA) [10] | Performs the underlying high-accuracy DFT calculations (e.g., at the ωB97X-3c level) to generate reference energies and forces for training MLIPs or final validation. | Used for the single-point calculations in the Halo8 protocol and other benchmark studies. |

| Hybrid Platform (InQuanto) [11] | Software that interfaces with quantum computers, allowing specific electronic structure problems from a larger simulation to be solved with quantum algorithms. | Used within the QIDO platform for tasks like modeling strongly correlated electrons in catalyst active sites. |

| 2-(Benzo[d]oxazol-5-yl)acetic acid | 2-(Benzo[d]oxazol-5-yl)acetic Acid|CAS 153810-37-8 | |

| 2-{[4-(Diethylamino)benzyl]amino}ethanol | 2-{[4-(Diethylamino)benzyl]amino}ethanol Research Chemical | High-purity 2-{[4-(Diethylamino)benzyl]amino}ethanol for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

The critical role of reaction pathways in predicting chemical reactivity and kinetics is being profoundly reshaped by new computational paradigms. The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates a clear trajectory from standalone quantum chemistry calculations towards integrated ecosystems that combine large-scale, high-quality datasets like OMol25 and Halo8 with fast, accurate machine learning potentials and emerging hybrid quantum-classical platforms [9] [10] [11].

For researchers in drug development and materials science, this evolution offers powerful new capabilities. The choice of methodology depends on the specific application: specialized datasets like Halo8 are indispensable for halogen-rich pharmaceutical discovery, while universal models like UMA offer broad applicability across biomolecular and material systems [10] [9]. Meanwhile, hybrid platforms like QIDO provide a strategic pathway to leverage nascent quantum computing for particularly challenging electronic structure problems today [11]. As these tools continue to mature and integrate, they will collectively enhance the predictive power of computational chemistry, accelerating the rational design of new molecules and materials.

Understanding chemical reactivity requires a detailed knowledge of the potential energy surface (PES), which describes the energy of a molecular system as a function of its atomic coordinates [13]. Within this multidimensional landscape, the minimum energy path (MEP) represents the most probable reaction pathway connecting reactants to products, a geodesic that minimizes energy in all directions orthogonal to the path [13]. Critical points along the MEP define the machinery of chemical reactions: transition states (first-order saddle points on the PES) represent energy maxima that dictate reaction kinetics, while intermediates (local minima) represent transient species with finite lifetimes [13] [14].

Accurately characterizing these features remains a fundamental challenge in computational chemistry, with significant implications for pharmaceutical development, where reaction rates and selectivity directly impact synthetic route design and drug candidate optimization. This guide provides a comparative analysis of computational methodologies for MEP exploration, transitioning from established traditional techniques to emerging machine-learning accelerated approaches, with a focus on performance validation within reaction pathway research.

Computational strategies for locating transition states and mapping MEPs have evolved significantly, offering researchers a diverse toolkit ranging from interpolation-based methods to advanced machine-learning potentials.

Traditional Transition State Location Methods

- Synchronous Transit Methods: These approaches use interpolated curves between reactant and product structures as surrogates for the true MEP.

- Linear Synchronous Transit (LST): Naïvely interpolates molecular coordinates between endpoints and identifies the highest energy point. While simple, it often produces poor guesses with unphysical geometries and multiple imaginary frequencies [13].

- Quadratic Synchronous Transit (QST): Uses quadratic interpolation for greater flexibility, then optimizes the geometry normal to the curve at the peak. The QST3 variant, which incorporates an initial TS guess, is robust and can recover from poor initial guesses [13].

- Elastic Band Methods: These methods optimize a series of images (nodes) along a guessed pathway, connected by spring forces to maintain spacing.

- Nudged Elastic Band (NEB): Improves upon early elastic band methods by projecting the spring forces tangentially along the path and the physical forces normally. This "nudging" prevents corner-cutting and pulls the path toward the MEP [13].

- Climbing-Image NEB (CI-NEB): Enhances standard NEB by allowing the highest energy image to climb uphill along the tangent and downhill in all other directions, providing a better estimate of the transition state without interpolation [13].

- Channel Following Methods:

- Dimer Method: This approach estimates the local curvature without calculating the Hessian by using a pair of geometries (a "dimer") separated by a small distance. The dimer is rotated to find the direction of lowest curvature, and steps are taken uphill until a saddle point is reached [13].

The Rise of Machine Learning Potentials

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have emerged as transformative tools, combining quantum mechanical accuracy with the speed of classical force fields [7]. They address the critical bottleneck in PES exploration: computational cost. Universal interatomic potentials (UIPs) like AIQM2 represent a significant advance. AIQM2 employs a Δ-learning approach, using an ensemble of neural networks to correct a semi-empirical (GFN2-xTB) baseline, and achieves accuracy approaching the coupled-cluster gold standard at a fraction of the cost [15]. This enables large-scale reaction dynamics studies, such as propagating thousands of trajectories for a bifurcating pericyclic reaction overnight to revise a mechanism previously studied with DFT [15].

Simultaneously, active learning workflows automate reaction discovery. Programs like ARplorer integrate quantum mechanics with rule-based approaches, guided by large language models (LLMs) that provide chemical logic for filtering unlikely pathways [8]. These methods leverage efficient quantum methods like GFN2-xTB for initial screening and higher-level methods for refinement, dramatically accelerating PES exploration.

Performance Comparison of Computational Methods

The following tables provide a comparative summary of the performance, experimental protocols, and resource requirements for key methodologies discussed.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Select Methodologies for TS and MEP Location

| Method | Computational Cost | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QST3 [13] | Moderate | Robust, can recover from poor initial guesses | Requires reactant, product, and TS guess; struggles with unphysical interpolations | Single, well-defined elementary steps with a plausible TS guess |

| CI-NEB [13] | High (scales with images) | Directly provides MEP and good TS estimate; less prone to corner-cutting | Requires many images for accuracy; spring constant choice can be nuanced | Mapping full reaction pathways, identifying complex TS geometries |

| Dimer Method [13] | Moderate (no Hessian) | Avoids expensive Hessian calculations; follows reaction channels | Can get lost in systems with multiple low-energy modes | Periodic DFT calculations with fixed or stiff vibrational modes |

| AIQM2 [15] | Low (Orders of magnitude faster than DFT) | Gold-standard accuracy; high transferability/robustness; provides uncertainty estimates | Currently limited to organic molecules (CHNO elements) | High-throughput screening, reaction dynamics, TS optimization |

| ARplorer [8] | Variable (efficient with filtering) | Automated, multi-step pathway exploration; LLM-guided chemical logic | Performance depends on quality of rule base and initial setup | High-throughput discovery of complex, multi-step reaction networks |

Table 2: Experimental Protocol and Validation Data for Featured Approaches

| Method | Core Computational Workflow | Key Validation Metrics | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIQM2 [15] | Δ-learning: Energy = GFN2-xTB* + ΔNN(ANI) + D4 dispersion. TS optimizations and MD trajectories performed with this potential. | Reaction energies, barrier heights, TS geometries against CCSD(T) and DFT. | Barrier heights: Accuracy at least at DFT level, often approaching CCSD(T). >1000x speedup vs DFT for dynamics. |

| Halo8 Dataset Generation [7] | Multi-level: GFN2-xTB for initial sampling → NEB/CI-NEB for pathway exploration → ωB97X-3c single-point DFT for accuracy. | Weighted mean absolute error (MAE) on the DIET and HAL59 benchmark sets. | 110x speedup vs pure DFT. ωB97X-3c MAE: 5.2 kcal/mol (vs. 15.2 kcal/mol for ωB97X/6-31G(d))). |

| ARplorer [8] | Active site identification → TS search with active learning → IRC analysis. GFN2-xTB for screening, DFT for refinement. | Successful identification of known multi-step reaction pathways for cycloaddition, Mannich-type, and Pt-catalyzed reactions. | Efficient filtering reduces unnecessary computations; enables automated exploration of complex organometallic systems. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

This section details key software solutions and computational resources that function as essential "reagents" in the modern computational chemist's toolkit for reaction pathway analysis.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Reaction Pathway Studies

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Pathway Research |

|---|---|---|

| GFN2-xTB [7] [8] | Semi-empirical Quantum Method | Provides a fast, reasonably accurate potential for initial pathway sampling, geometry optimization, and high-throughput screening. |

| ORCA [7] | Quantum Chemistry Package | Performs high-level DFT (e.g., ωB97X-3c) single-point energy and force calculations for accurate energetics on structures from sampling workflows. |

| CP2K [16] | Quantum Chemistry Package | Performs ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations, crucial for studying dynamics and entropy effects at electrochemical interfaces. |

| DeePMD-kit [16] | Machine Learning Potential Tool | Trains neural network potentials using data from AIMD simulations, enabling nanosecond-scale ML-driven MD while maintaining ab initio accuracy. |

| MLatom [15] | Software Package | Provides an interface for using AI-enhanced quantum methods like AIQM1 and AIQM2 for energy, force, and property calculations. |

| Halo8 Dataset [7] | Training Data | A comprehensive dataset of ~20 million quantum calculations from 19,000 reaction pathways, including halogens, for training transferable MLIPs. |

| Bicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-2-carbonyl chloride | Bicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-2-carbonyl chloride, CAS:35202-90-5, MF:C8H11ClO, MW:158.62 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Tert-butylbenzenesulfonic acid | 4-Tert-butylbenzenesulfonic Acid|CAS 1133-17-1 |

Workflow Visualization: Computational Pathways in Practice

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow of two dominant paradigms: the established NEB method and a modern, machine-learning-accelerated workflow.

Diagram 1: The Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) Workflow. This iterative process refines an initial guess path by applying nudged forces until the minimum energy path is found. [13]

Diagram 2: Machine Learning-Accelerated Reaction Pathway Discovery. This workflow leverages pre-trained, universal potentials like AIQM2 to enable large-scale screening and simulation, with final validation using high-level quantum chemistry. [7] [15] [8]

The comparative analysis presented in this guide reveals a dynamic field in transition. Established methods like QST and NEB remain valuable for specific, well-defined problems, but the emergence of MLIPs like AIQM2 and automated workflows like ARplorer marks a paradigm shift. The critical performance differentiators are speed (orders of magnitude faster than conventional DFT) and automation (enabling high-throughput exploration of complex chemical spaces).

For researchers in drug development, these advances are particularly significant. The ability to rapidly map multi-step reaction pathways and accurately calculate kinetics for complex organic molecules directly accelerates synthetic route design and optimization. The integration of AI and computational chemistry, powered by robust datasets like Halo8, is validating a new approach to reaction pathway research: one that is more predictive, efficient, and integrated, promising to significantly shorten development cycles from concept to candidate.

In quantum chemistry, the pursuit of accurate simulations of molecular structure and reactivity is fundamentally governed by the choice of basis set—a set of mathematical functions used to represent the electronic wavefunction of a molecule. The incompleteness of this set introduces a completeness error, a systematic deviation from the exact solution of the Schrödinger equation, which directly impacts the reliability of computed energies, forces, and other molecular properties. For researchers investigating chemical reaction pathways, particularly in fields like pharmaceutical design where subtle energy differences of ~1 kcal/mol can determine a project's success, navigating this error is paramount [17]. The core challenge lies in the trade-off between computational cost and accuracy; larger, more complete basis sets reduce completeness error but demand exponentially greater resources [18].

This guide provides an objective comparison of basis set performance, framing the evaluation within the critical context of validating quantum chemistry methods for reaction pathway research. It synthesizes current experimental data and methodologies to empower scientists in making informed decisions that balance accuracy and efficiency in their computational workflows.

Theoretical Foundation: Understanding Basis Sets and Completeness Errors

A basis set approximates molecular orbitals as linear combinations of atomic-centered functions, typically Slater-Type Orbitals (STOs) or Gaussian-Type Orbitals (GTOs). The "completeness" of a set determines how well it can represent the true electron distribution. Key quality indicators include:

- Zeta (ζ) Number: Represents the number of basis functions per atomic orbital. Single zeta (SZ) is minimal, while double (DZ), triple (TZ), and quadruple (QZ) zeta provide successively better resolution of electron distribution.

- Polarization Functions: Angular momentum functions higher than required by the ground state atom (e.g., d-functions on carbon), which allow orbitals to change shape during bond formation or in electric fields. Their addition is denoted by a 'P'.

- Diffuse Functions: Very wide, low-exponent functions that better describe electrons far from the nucleus, such as in anions or non-covalent interactions.

The completeness error arises from the truncation of this infinite expansion. It manifests as inaccuracies in:

- Absolute and relative energies

- Molecular geometries and vibrational frequencies

- Reaction barrier heights

- Properties of non-covalent interactions

Systematic improvement of a basis set, known as hierarchical convergence, is the primary strategy for estimating and reducing this error, often by progressing through tiers such as SZ → DZ → DZP → TZP → TZ2P → QZ4P [18].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Standard Basis Sets

Accuracy and Computational Cost Benchmarking

Quantitative benchmarking against high-level reference data or established test sets is essential for evaluating basis set performance. The following table summarizes the typical accuracy and computational cost of standard basis sets for common quantum chemical calculations, using data derived from studies on organic systems and the DIET benchmark set [10] [18].

Table 1: Performance and Cost Comparison of Standard Basis Sets for a Carbon-Based System (e.g., a (24,24) Carbon Nanotube)

| Basis Set | Full Name | Energy Error (eV/atom) [a] | CPU Time Ratio (Relative to SZ) | Recommended Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SZ | Single Zeta | ~1.8 | 1.0 | Very rapid testing; initial structure pre-optimization. |

| DZ | Double Zeta | ~0.46 | 1.5 | Cost-effective pre-optimization; not recommended for properties involving virtual orbitals. |

| DZP | Double Zeta + Polarization | ~0.16 | 2.5 | Reasonable geometry optimizations for organic systems. |

| TZP | Triple Zeta + Polarization | ~0.048 | 3.8 | Ideal balance for most applications, including reaction pathways [18]. |

| TZ2P | Triple Zeta + Double Polarization | ~0.016 | 6.1 | High accuracy; recommended for properties requiring a good description of the virtual space (e.g., band gaps). |

| QZ4P | Quadruple Zeta + Quadruple Polarization | Reference | 14.3 | Benchmarking; obtaining reference data for smaller sets. |

[a] Absolute error in formation energy per atom, using QZ4P as reference.

It is critical to note that errors in absolute energies are significantly larger than errors in energy differences (such as reaction energies or activation barriers) due to systematic error cancellation. For example, the basis set error for the energy difference between two carbon nanotube variants can be below 1 milli-eV/atom with a DZP basis, far smaller than the absolute energy error [18].

Specialized Basis Sets for Halogen-Containing Systems

The accurate description of halogen atoms, prevalent in ~25% of pharmaceuticals, poses a particular challenge due to their complex electronic structure, polarizability, and significant dispersion contributions [10]. Standard basis sets like 6-31G(d) can be insufficient, sometimes failing even to perform calculations on heavier halogens like bromine [10].

Composite methods with optimized basis sets offer a powerful alternative. The ωB97X-3c method, for instance, is a dispersion-corrected global hybrid functional that employs a specially optimized triple-zeta basis set. Benchmarking on the HAL59 dataset (focused on halogen dimer interactions) and the broader DIET set shows it delivers accuracy comparable to quadruple-zeta quality methods but at a fraction of the computational cost (5.2 kcal/mol weighted MAE vs. 15.2 kcal/mol for ωB97X/6-31G(d)) [10]. This makes it an excellent compromise for generating large-scale datasets for reaction pathways involving halogens, as demonstrated in the Halo8 dataset comprising ~20 million quantum chemical calculations [10].

Table 2: Benchmarking of Methods for Halogenated Systems (DIET & HAL59 test sets)

| Method & Basis Set | Weighted MAE (kcal/mol) on DIET [a] | Computational Cost (Time Relative to ωB97X-3c) | Suitability for Halogen Chemistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| ωB97X / 6-31G(d) | 15.2 | Lower | Poor; fails for many heavier halogens. |

| ωB97X-3c | 5.2 | 1.0 (Reference) | Excellent; consistent accuracy for F, Cl, Br. |

| ωB97X-D4 / def2-QZVPPD | 4.5 | ~5.0 | Best, but often computationally prohibitive for large-scale sampling. |

[a] Weighted Mean Absolute Error on the DIET benchmark set, normalizing errors across molecules of different sizes and energy scales [10].

Experimental Protocols for Basis Set Validation

Workflow for Hierarchical Convergence Testing

A robust validation of a quantum chemistry method for a specific research problem, such as reaction pathway mapping, must include a basis set convergence study. The following workflow diagram outlines a standardized protocol for this process.

Protocol for Reaction Pathway Sampling and Validation

For validating methods for reaction pathway research, the protocol becomes more complex, often involving a multi-level approach to make the sampling computationally feasible [10] [19]. The methodology used to generate the Halo8 dataset is a prime example of an efficient and automated workflow.

Table 3: Key Stages in the Halo8 Reaction Pathway Sampling Protocol [10]

| Stage | Key Tools/Methods | Purpose & Output | Basis Set / Level of Theory |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Reactant Preparation | RDKit [10], OpenBabel/MMFF94 [10], GFN2-xTB [10] | Generate diverse, chemically valid 3D starting geometries from SMILES strings. | GFN2-xTB (Semi-empirical) |

| 2. Product Search | Single-Ended Growing String Method (SE-GSM) [19] | Explore possible bond rearrangements and discover reaction products from the reactant alone. | GFN2-xTB (Semi-empirical) |

| 3. Landscape Search | Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) with Climbing Image [19] | Find minimum energy path and transition state between reactant-product pairs; capture intermediate structures. | GFN2-xTB (Semi-empirical) |

| 4. High-Level Refinement | ORCA 6.0.1 [10] | Perform final single-point energy and property calculations on selected pathway structures. | ωB97X-3c [10] |

This protocol achieved a 110-fold speedup compared to pure DFT workflows, demonstrating the efficiency of using lower-level methods for sampling before high-level refinement [10]. The final dataset's accuracy is anchored by the robust ωB97X-3c level of theory, validated against established benchmarks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

The following table details key software tools and computational methods that function as essential "research reagents" in the field of quantum chemical reaction pathway exploration.

Table 4: Essential Tools for Quantum Chemical Reaction Pathway Research

| Tool / Method Name | Type | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit [10] | Cheminformatics Library | Handles molecule perception, canonical SMILES generation, and stereochemistry enumeration. |

| GFN2-xTB [10] | Semi-empirical Quantum Method | Provides fast and reasonably accurate geometry optimizations, initial pathway sampling, and conformational searching. |

| ORCA [10] | Quantum Chemistry Package | Performs high-accuracy single-point energy and property calculations (e.g., with ωB97X-3c) for final dataset refinement. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) [10] | Python Library | Serves as a flexible framework for setting up, managing, and running computational chemistry simulations. |

| Dandelion [10] | Computational Pipeline | Automates the entire reaction pathway sampling workflow, integrating the tools above. |

| SE-GSM & NEB/CI-NEB [19] | Path Sampling Algorithms | Systematically explores chemical reaction space and locates transition states and minimum energy paths. |

| ωB97X-3c [10] | Composite DFT Method & Basis Set | Offers a high-accuracy, cost-effective level of theory for final energy evaluation, especially good for halogens and non-covalent interactions. |

| 3-Amino-6-phenylpyrazine-2-carbonitrile | 3-Amino-6-phenylpyrazine-2-carbonitrile|CAS 50627-25-3 | 3-Amino-6-phenylpyrazine-2-carbonitrile (95+% purity) is a key pyrazine scaffold for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Ethyl 2-(1-hydroxycyclohexyl)acetate | Ethyl 2-(1-hydroxycyclohexyl)acetate, CAS:5326-50-1, MF:C10H18O3, MW:186.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The critical impact of basis set choice on calculation accuracy necessitates a deliberate and validated approach, especially in reaction pathway research where confidence in energy differences is key. The evidence indicates that while large, quadruple-zeta basis sets remain the gold standard for benchmarking, modern composite methods and triple-zeta plus polarization basis sets like TZP and ωB97X-3c offer an optimal balance, providing high accuracy suitable for drug discovery and materials design at a manageable computational cost [10] [18].

Future progress will be driven by the continued development of efficient, chemically-aware basis sets and their integration into automated, multi-level workflows. These protocols, which synergistically combine the speed of semi-empirical methods and machine-learning potentials with the precision of selectively applied high-level quantum chemistry, are making the comprehensive exploration of complex reaction networks an achievable reality [19] [20]. For researchers, adopting these rigorous validation practices and tools is no longer optional but fundamental to producing reliable, predictive computational results.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Methods for Real-World Reaction Problems

Locating transition states (TSs) and determining reaction pathways is a cornerstone of computational chemistry, vital for accurately characterizing chemical reactions and predicting thermodynamic and kinetic parameters [21]. These TSs exist as first-order saddle points on the Born-Oppenheimer potential energy surface (PES) [21]. The challenge lies in efficiently and reliably finding these points on a complex multidimensional surface. Transition state search algorithms can be broadly categorized into surface-walking methods and interpolation-based methods [21]. Surface-walking algorithms, such as those using the quasi-Newton method, maximize the largest negative eigenvalue of the Hessian matrix to locate the saddle point [21] [22]. Conversely, interpolation-based methods first use a non-local path-finding algorithm to obtain a TS guess structure before refining it [21].

This guide provides a detailed, step-by-step comparison of three pivotal techniques for exploring reaction pathways: the Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method, the String Method, and Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) calculations. We will dissect their theoretical foundations, provide explicit computational protocols, and benchmark their performance using published data, framing this within the broader thesis of validating quantum chemistry methods for reaction pathway research.

Conceptual Foundations and Key Distinctions

- Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC): The IRC is defined as the steepest descent path from a first-order saddle point (the transition state) down to the local minima (reactants and products) [22]. It is considered the true minimum energy path (MEP) on the PES. A critical limitation is that IRC calculations require a pre-optimized transition state structure as a starting point, which is often unknown for new reactions [22].

- Nudged Elastic Band (NEB): NEB is a double-ended interpolation method that finds a reaction path and the transition state between a defined reactant and product state [23]. It works by creating a discrete chain of images (intermediate structures) between the endpoints. These images are optimized simultaneously, with forces perpendicular to the path guiding the images down to the MEP, and artificial spring forces parallel to the path maintaining an even distribution of images [23]. A "climbing image" algorithm can be employed to drive the highest-energy image directly to the saddle point [23].

- String Method: The String method is another double-ended chain-of-states approach similar in spirit to NEB [21]. In its "Growing String" variant, the method begins as two string fragments, one associated with the reactants and the other with the products [24]. Each fragment is grown separately until they converge, at which point the full string moves toward the MEP [24]. This approach can find MEPs and TSs without requiring an initial guess for the entire pathway [24].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each method.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Pathway Calculation Methods

| Method | Starting Point | End Point | Key Feature | Primary Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRC | Transition State | Reactant & Product | Steepest descent path from a known TS [22] | Minimum Energy Path (MEP) |

| NEB | Reactant & Product | Transition State & Path | Chain of images connected by spring forces [23] | Approximate MEP & TS guess |

| String Method | Reactant & Product | Transition State & Path | Path can be grown without a full initial guess [24] | Approximate MEP & TS guess |

Step-by-Step Computational Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the standard computational workflow for each method, highlighting their procedural differences.

IRC Workflow

Diagram 1: IRC calculation steps.

NEB Workflow

Diagram 2: NEB calculation steps. [23]

String Method Workflow

Diagram 3: String Method calculation steps. [24]

Experimental Protocols and Key Reagents

To ensure reproducibility and computational efficiency, follow these detailed protocols. The essential "research reagents" for these calculations are the software, computational models, and datasets.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Reaction Pathway Calculations

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Role | Example Manifestation |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Code | Performs the core quantum mechanical energy and force calculations. | AMS [23], Gaussian [22] |

| Density Functional/Basis Set | The "level of theory" defining the accuracy/cost trade-off of the PES. | B3LYP, M06-2X, ωB97M-V [25] |

| Pre-trained Potential | Machine-learning surrogate for DFT; drastically reduces cost. | SchNet GNN [21], DeePHF [25] |

| Benchmark Dataset | Provides reference data for training and validating methods. | ANI-1 [21], GDB7-20-TS [25], Transition1x [25] |

Protocol for NEB Calculation (AMS)

The following protocol is adapted from the AMS documentation [23].

- System Preparation: Define the reactant and product systems in separate

Systemblocks. The order of atoms must be identical in all systems [23]. - Task and Endpoint Specification: Set the

TasktoNEB. The first system is the initial reactant, and a system namedfinalis the final product. - NEB Block Configuration: In the

NEBinput block, key parameters include:Images: The number of intermediate images (default 8) [23].Climbing: Set toYesto enable the climbing image algorithm [23].Spring: The spring force constant (default 1.0 Hartree/Bohr²) [23].PreOptimizeWithIDPP: (Experimental) Set toYesto use the Image Dependent Pair Potential for an improved initial path [23].

- Path Optimization: The calculation performs a simultaneous optimization of all images. The climbing image will be driven to the transition state.

Protocol for Freezing String Method with ML Potential

This protocol is based on the work integrating a Graph Neural Network (GNN) with FSM [21].

- Potential Pre-training: Pre-train a GNN potential (e.g., SchNet) on a broad dataset of equilibrium molecular structures (e.g., ANI-1) [21].

- Fine-Tuning: Fine-tune the pre-trained model on a smaller, specialized dataset containing reactant, product, and TS structures (e.g., GDB7-20-TS) [21]. This step is critical for accurately describing the reaction barrier region [21].

- FSM Execution: Perform the FSM calculation using the fine-tuned GNN potential as the surrogate for the PES to generate a high-quality TS guess geometry.

- DFT Refinement (Optional): Use the ML-generated TS guess as the starting point for a final, precise optimization using a standard DFT method.

Protocol for IRC Calculation

- Prerequisite: A pre-optimized transition state structure and its associated Hessian matrix.

- IRC Direction: Follow the reaction path in both the forward and reverse directions from the TS using a steepest-descent algorithm [22].

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the geometries at the end of each IRC path to confirm they correspond to the expected reactant and product local minima.

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Data

The efficiency and success of these methods are benchmarked by the number of expensive PES evaluations required and the final accuracy in locating the TS. The following table synthesizes quantitative data from the literature.

Table 3: Performance Benchmarking of Pathway Methods

| Method | Computational Cost (PES Evaluations) | TS Geometry Accuracy | Key Advantages | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEB (DFT) | Hundreds to thousands [23] | Good with climbing image [23] | Robust, provides full path information [23] | Computationally expensive; sensitive to initial path guess [23] [24] |

| NEB (GNN) | ~72% fewer DFT calculations than DFT-NEB [21] | High (with fine-tuned potential) [21] | Dramatically reduced cost; high success rate (100% in benchmark) [21] | Dependent on quality and scope of ML potential training data [21] |

| Growing String | Fewer than NEB for poor initial guesses [24] | Good | Does not require a full initial path guess [24] | --- |

| IRC | Lower cost after TS is found | Exact path from known TS [22] | The definitive MEP [22] | Requires a pre-optimized TS; can fail to expected minima [26] [22] |

Supporting Experimental Data:

- A study on the alanine dipeptide rearrangement showed that the Growing String Method found the saddle point with significantly fewer electronic structure force calculations than the String Method or NEB when the initial linear guess was poor [24].

- Integrating a fine-tuned SchNet GNN potential into the FSM achieved a 100% success rate in locating reference TSs across a benchmark suite, while reducing the number of ab-initio calculations by 72% on average compared to conventional DFT-based FSM searches [21].

Integrated Discussion and Outlook

The choice between NEB, String, and IRC methods is not a matter of identifying a single superior technique, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific research problem based on available starting information and computational resources.

The IRC-NEB/String Symbiosis: In practice, these methods are often used synergistically. NEB or the String Method are first employed as a "TS hunting" tool to generate a reliable guess for the transition state from reactant and product structures. This TS guess is then refined with a surface-walking algorithm, and the final, validated MEP is obtained from an IRC calculation [21] [22]. This hybrid approach mitigates the primary weakness of IRC (requiring a known TS) and the potential inaccuracy of the path from interpolation methods.

The Role of Machine Learning: The integration of ML potentials represents a paradigm shift. As demonstrated, using a GNN potential as a surrogate for DFT in the FSM can reduce the computational cost of the initial path-finding step by nearly three-quarters while maintaining a high success rate [21]. This makes high-level TS searches dramatically more accessible. Furthermore, methods like DeePHF aim to achieve CCSD(T)-level accuracy in reaction energy and barrier height predictions while retaining DFT-like efficiency, potentially bypassing traditional accuracy-scalability tradeoffs [25].

Algorithmic Innovations: Continued development of algorithms is also crucial. Methods like ReactionString automatically adjust the number of intermediate images, densely sampling near the TS for higher accuracy, and can handle complex paths with multiple TSs [26]. Tools like RestScan are invaluable for systematically generating the initial and final structures required for these path searches, especially when the reaction coordinate is not well understood [26].

In conclusion, the validation of quantum chemistry methods for reaction pathway research is increasingly relying on a multi-faceted toolkit. While traditional algorithms like NEB and IRC remain essential, their power is being vastly amplified by machine learning surrogates and sophisticated growing-string algorithms. This synergy between advanced sampling, robust optimization, and high-accuracy ML potentials is rapidly advancing our capacity to explore chemical reactivity with unprecedented efficiency and scale.

In modern drug research, prodrug activation strategies are essential for improving the efficacy and safety of therapeutic agents [27]. These strategies involve designing inactive compounds that convert into active drugs within the body, often through the selective cleavage of specific chemical bonds. Among these, the cleavage of robust carbon-carbon (C-C) bonds presents a particular challenge, requiring precise conditions and sophisticated mechanistic understanding [27]. Accurately calculating the Gibbs free energy profile of this cleavage process is crucial, as it determines whether the reaction proceeds spontaneously under physiological conditions and directly impacts drug design decisions [27].

This case study examines the application of a hybrid quantum computing pipeline to calculate these essential energy profiles, benchmarking its performance against established computational chemistry methods. The work validates this emerging technology within the broader context of verifying quantum chemistry methods for reaction pathway research, demonstrating its potential to address real-world drug discovery challenges that exceed the capabilities of classical computing approaches [27].

Computational Methods for Energy Profiling

Established Classical Methods

Traditional computational chemistry employs several methods for modeling molecular systems and reaction energies:

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): Often the preferred method in pharmacochemical reaction calculations due to its balance between efficiency and accuracy [27]. For the β-lapachone prodrug system, the M06-2X functional has been used to calculate energy barriers [27].

- Hartree-Fock (HF) Method: Provides a fundamental quantum mechanical approach that serves as a starting point for more accurate methods, though it lacks electron correlation effects [27].

- Complete Active Space Configuration Interaction (CASCI): Offers a more accurate reference by accounting for electron correlation within a defined active space, considered an exact solution under active space approximation [27].

Hybrid Quantum Computing Approach

The variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) framework has emerged as a promising hybrid quantum-classical approach suitable for near-term quantum computers [27] [28]. This method combines parameterized quantum circuits with classical optimizers:

- Quantum Processing: Parameterized quantum circuits prepare and measure the energy of target molecular systems [28].

- Classical Optimization: A classical optimizer minimizes the energy expectation value until convergence, resulting in an approximation of the molecular wave function and the variational ground state energy [27] [28].

- Active Space Approximation: To accommodate current hardware limitations, large chemical systems are simplified into manageable active spaces (e.g., two electron/two orbital systems) [27].

- Solvation Effects: Critical for biological relevance, solvation energy calculations implement polarizable continuum models (PCM) such as ddCOSMO to simulate aqueous environments [27].

Hybrid Quantum Computing Workflow: The pipeline integrates quantum and classical resources to compute molecular energies.

Case Study: C-C Bond Cleavage in β-Lapachone Prodrug

Biological Context and Significance

The case study focuses on β-lapachone, a natural product with extensive anticancer activity [27]. Researchers have developed an innovative prodrug design for this compound that utilizes carbon-carbon bond cleavage as an activation mechanism, validated through animal experiments [27]. This approach addresses limitations in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the active drug, representing a valuable supplement to existing prodrug strategies [27].

Computational Setup and Parameters

The research team implemented a specialized computational protocol to model the prodrug activation:

- System Preparation: Five key molecules involved in the C-C bond cleavage were selected as simulation subjects after conformational optimization [27].

- Basis Set: The 6-311G(d,p) basis set was employed for both classical and quantum computations [27].

- Solvation Model: The ddCOSMO solvation model implemented polarizable continuum modeling to simulate physiological aqueous environments [27].

- Active Space: A simplified two electron/two orbital system enabled processing on available quantum devices [27].

- Quantum Hardware: Calculations utilized a 2-qubit superconducting quantum device with a hardware-efficient R_y ansatz and single-layer parameterized quantum circuit for VQE [27].

- Error Mitigation: Standard readout error mitigation techniques enhanced measurement accuracy [27].

Performance Comparison Across Methods

Table 1: Comparison of computational methods for prodrug activation energy profiling

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Hardware Requirements | Active Space Handling | Solvation Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (M06-2X) | Electron density functionals | Classical computing | Full system | Implicit solvation models |

| Hartree-Fock | Approximate molecular orbitals | Classical computing | Full system | Implicit solvation models |

| CASCI | Electron configuration interaction | Classical computing | Defined active space | Implicit solvation models |

| VQE Hybrid | Variational quantum algorithm | Quantum-classical hybrid | Reduced active space | ddCOSMO solvation model |

Table 2: Experimental results for C-C bond cleavage energy calculations

| Method | Calculation Type | System Size | Energy Barrier | Computational Time | Agreement with Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (M06-2X) [27] | Single-point energy | Full molecular system | Compatible with wet lab results | Standard DFT timing | Validated |

| HF [27] | Single-point energy | Full molecular system | Consistent with wet lab results | Standard HF timing | Consistent |

| CASCI [27] | Single-point energy | Active space | Consistent with wet lab results | CASCI computational cost | Consistent |

| VQE Hybrid [27] [28] | Variational energy | Reduced active space | Experimentally consistent | ~60 seconds total quantum kernel | Consistent |

The hybrid quantum computing pipeline demonstrated particular strength in calculating energy barriers that determine spontaneous reaction progression under physiological conditions [27]. The quantum computing kernel required approximately 60 seconds for complete energy expectation calculations, including measurement of one-body reduced density matrices in the active space [27] [28].

Prodrug Activation Energy Profile: The transition state for C-C bond cleavage determines the reaction kinetics.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational resources for prodrug activation studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Chemistry Packages | TenCirChem [27] | Implements entire quantum computing workflow for molecular simulations |

| Solvation Models | ddCOSMO [27] | Models solvent effects in quantum calculations of biological systems |

| Active Space Methods | CASCI [27] | Provides reference values for quantum computation within defined orbital spaces |

| Quantum Algorithms | Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) [27] [28] | Measures molecular energy states on quantum hardware |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Standard readout error mitigation [27] | Enhances accuracy of quantum measurements |

| Biomolecular Simulation | QM/MM [27] | Enables hybrid quantum-mechanical/molecular-mechanical simulations |

This case study demonstrates that hybrid quantum computing pipelines can effectively calculate Gibbs free energy profiles for prodrug activation via covalent bond cleavage, producing results consistent with both traditional computational methods and experimental findings [27]. The successful application to the β-lapachone prodrug system, which involves precise C-C bond cleavage under physiological conditions, validates this emerging approach for studying pharmaceutically relevant reaction pathways [27].

The VQE framework combined with active space approximation and appropriate solvation models represents a viable strategy for current quantum hardware, achieving computation times of approximately 60 seconds for energy profiling tasks [27] [28]. As quantum devices continue to scale in qubit count and fidelity, these approaches are expected to surpass classical methods for increasingly complex molecular systems, potentially revolutionizing computational drug discovery for challenging targets like covalent inhibitors [27].

This work establishes crucial benchmarks for quantum computing applications in pharmaceutical research and provides a versatile pipeline that researchers can adapt to various drug discovery challenges, particularly those involving intricate bonding interactions that prove difficult for classical computational methods [27].

The accurate prediction of binding free energy is often considered the "holy grail" of computational drug discovery, as it directly determines a drug candidate's potency and binding affinity for its biological target [29] [30]. While classical molecular mechanics (MM) force fields have traditionally dominated molecular dynamics and docking studies for their computational efficiency, they possess significant limitations. These limitations occur due to the neglect of electronic contributions that play a substantial role in processes like charge transfer, polarization, and covalent bond formation/cleavage [31] [32].

Quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) hybrid methods have emerged as a powerful alternative that increases computational accuracy while remaining feasible for biologically relevant systems [31] [32]. In this approach, the ligand and key active site residues are treated quantum mechanically, while the remainder of the receptor and solvent environment is treated with classical molecular mechanics [31]. This allows for a more accurate description of electronic effects while maintaining computational tractability for large biomolecular systems. The total energy function in a QM/MM approach is expressed as:

Etotal = EQM + EMM + EQM/MM

Where EQM and EMM are the energies for the QM and MM regions, respectively, and EQM/MM describes the interaction between the QM and MM parts, typically containing terms for electrostatic, van der Waals, and bonding interactions across the region [31].

This case study examines the implementation, validation, and comparative performance of QM/MM methods for predicting drug-target interactions across multiple biological systems, with a particular focus on binding free energy calculations and their importance in rational drug design.

QM/MM Methodologies and Protocols

Fundamental Theoretical Frameworks

QM/MM binding free energy calculations combine the accuracy of quantum mechanical treatment for electronic effects with the efficiency of molecular mechanics for the biomolecular environment. Several methodological frameworks have been developed to implement this hybrid approach:

The QM/MM-PB/SA method calculates binding free energy by combining QM and MM principles where the ligand is treated quantum mechanically and the receptor by classical molecular mechanics [31]. The free energy is computed separately for ligand (L), protein (P), and ligand/protein complex (C), with the binding free energy expressed as:

ΔGbind = ΔEint + ΔEQM/MM + ΔGsolv - TΔS

Here, ΔEint represents the change in protein intramolecular energy, ΔEQM/MM is the interaction energy between receptor and ligand obtained using QM/MM, ΔGsolv is the solvation free energy change, and -TΔS represents entropic contributions [31].

The indirect approach to QM/MM free energies reduces computational expense by performing most calculations at a classical level and applying QM/MM "corrections" at the endpoints [33]. This strategy avoids the need for expensive QM/MM simulations throughout the calculation while still incorporating electronic effects at critical stages. The correction uses the Zwanzig equation:

ΔAMM→QM/MM = -1/β log⟨exp(-β(UQM/MM - UMM))⟩MM

This allows sampling to be performed classically with QM/MM energetics processed post-simulation [33].

Recent advances have also introduced multi-protocol frameworks that combine QM/MM with mining minima approaches. These protocols involve replacing force field atomic charges with charges obtained from QM/MM calculations for selected conformers, followed by free energy processing with or without additional conformational search [29].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A standardized workflow has emerged for QM/MM binding free energy calculations, though specific implementations vary across studies:

System Preparation: The process begins with obtaining the crystal structure of the protein-ligand complex from sources like the Protein Data Bank. Missing residues and hydrogen atoms are added, and the ligand parameters are typically prepared using ab initio methods with basis sets such as 6-31G* [31]. Protonation states are adjusted according to physiological pH, and the system is solvated in an appropriate water model.

Parameterization: For classical MM components, standard force fields like AMBER ff03 or CHARMM are used [31] [33]. For the QM region, various semi-empirical methods (DFTB-SCC, PM3, MNDO), density functional tight binding (DFTB3), or approximate density functional theory methods can be employed [31] [30]. Parameterization via force-matching approaches has shown benefits in improving configurational overlap with target QM/MM Hamiltonians [33].

Dynamics Simulation: MD simulations using hybrid QM/MM methods are performed, with the protein and water modeled classically using force fields while the ligand is treated with semi-empirical QM methods [31]. Multiple simulations are typically carried out to ensure adequate sampling of conformational space.

Free Energy Calculation: Binding free energies are computed using the chosen framework (QM/MM-PB/SA, indirect approaches, etc.). Entropic contributions are estimated using normal mode analysis or quasi-harmonic approximations [31].

Validation: Results are validated against experimental binding affinities (IC50, Ki values) from biochemical assays or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) measurements [34].

The following workflow diagram illustrates a generalized QM/MM binding free energy calculation protocol:

Comparative Performance Analysis

Method Performance Across Diverse Targets

Recent studies have systematically evaluated QM/MM methods across multiple protein targets and ligands, providing robust performance comparisons. The table below summarizes key results from major studies:

Table 1: Performance of QM/MM Methods Across Diverse Protein Targets

| Study & System | Method | Targets | Ligands | Correlation (R) | MAE (kcal/mol) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-target benchmark [29] | QM/MM-MC-FEPr | 9 targets (CDK2, JNK1, BACE, etc.) | 203 | 0.81 | 0.60 | Superior to many existing methods with significantly lower computational cost than FEP |

| c-Abl tyrosine kinase [31] | QM/MM-PB/SA | c-Abl kinase | Imatinib | Strong correlation | N/A | DFTB-SCC semi-empirical Hamiltonian provided better results than other methods |

| SAMPL8 challenge [33] | PM6-D3H4/MM | Host-guest systems | 7 narcotics | 0.78 | ~2.43 | Best QM/MM entry in ranked submissions |

| Influenza NP inhibitors [34] | QM/MM analysis | Nucleoprotein | 16 compounds | Experimental validation | N/A | Complemented MM-GBSA and MD in identifying potent inhibitors |

The high Pearson's correlation coefficient of 0.81 and low mean absolute error of 0.60 kcal/mol achieved by the QM/MM-MC-FEPr protocol across 9 targets and 203 ligands demonstrates that QM/MM methods can achieve accuracy comparable to popular relative binding free energy techniques like FEP+ but at significantly lower computational cost [29]. This performance surpasses many existing methods and highlights the potential for broader application in drug discovery pipelines.

Comparison of QM Methods and Semi-empirical Approximations

The choice of QM method significantly impacts both accuracy and computational efficiency in QM/MM simulations. Different semi-empirical methods and approximations have been systematically compared:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of QM Methods in QM/MM Simulations

| QM Method | Theoretical Basis | Accuracy | Computational Cost | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFTB-SCC [31] | Derived from DFT, self-consistent charge | High (better than other semi-empirical) | Moderate | Systems requiring good accuracy with manageable computational cost |

| PDDG-PM3 [31] | Parameterized, correction to PM3 | Moderate | Low to moderate | Large systems where DFTB remains expensive |

| PM3 [31] | Parametrized Model 3 | Moderate | Low | Initial screening, very large systems |

| MNDO [31] | Modified Neglect of Diatomic Overlap | Lower for some systems | Low | Systems with well-parameterized elements |