Variance-Based Allocation vs. Uniform Distribution: A Strategic Framework for Optimizing Clinical Trials and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the strategic choice between variance-based allocation and uniform distribution in clinical trials and quantitative research.

Variance-Based Allocation vs. Uniform Distribution: A Strategic Framework for Optimizing Clinical Trials and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the strategic choice between variance-based allocation and uniform distribution in clinical trials and quantitative research. It explores the foundational principles of both methods, delves into practical applications across various trial designs—including platform trials and incomplete within-subject studies—and addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges. Through empirical validation and comparative analysis, the article demonstrates how variance-based allocation can enhance statistical power, control costs, and improve the efficiency of R&D pipelines, ultimately supporting more informed decision-making in biomedical research.

Understanding the Core Principles: Uniform vs. Variance-Based Allocation

In both computational science and clinical research, the principle of equitable distribution serves as a critical foundation for ethical and methodological rigor. In statistics, the uniform distribution represents a probability model where all outcomes within a defined interval are equally likely, providing a mathematical framework for random assignment [1] [2]. Parallel to this statistical concept, clinical research operates on the ethical principle of equipoise—a state of genuine uncertainty within the expert medical community about the comparative merits of different treatments [3] [4]. This article explores the fundamental relationship between these concepts, examining how uniform distribution serves as the mathematical embodiment of equipoise and comparing it with more advanced, variance-informed allocation strategies that have emerged in contemporary research.

The uniform distribution provides the mathematical underpinning for randomized treatment assignment in clinical trials, ensuring that each patient has an equal probability of receiving any given intervention when genuine equipoise exists [5]. This approach guarantees that allocation remains free from systematic bias, thereby preserving the trial's ethical integrity. However, emerging methodologies are challenging this paradigm by incorporating variance-based considerations that optimize resource allocation while maintaining ethical standards, creating a nuanced landscape for clinical trial design [6] [5].

Mathematical Foundations of Uniform Distribution

Statistical Properties and Formulas

The continuous uniform distribution, also known as the rectangular distribution, is defined by two parameters: a lower bound (a) and an upper bound (b) [1]. Within the interval [a, b], all values have equal probability, while values outside this interval have zero probability. This statistical model provides the mathematical basis for random assignment in clinical trials when true equipoise exists.

The probability density function (PDF) for a continuous uniform distribution is defined as:

$$f(x) = \begin{cases} \dfrac{1}{b-a}, & \text{if } a \leq x \leq b \ 0, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}$$

For this distribution, key statistical properties include:

- Mean: $\mu = \dfrac{a+b}{2}$

- Variance: $\sigma^2 = \dfrac{(b-a)^2}{12}$

- Standard Deviation: $\sigma = \dfrac{b-a}{\sqrt{12}}$ [1]

The cumulative distribution function (CDF), which provides the probability that the random variable X will take a value less than or equal to x, is expressed as:

$$F(x) = P(X \leq x) = \begin{cases} 0, & \text{if } x < a \ \dfrac{x-a}{b-a}, & \text{if } a \leq x \leq b \ 1, & \text{if } x > b \end{cases}$$

Discrete Uniform Distribution

In clinical trial design, where patients are allocated to a finite number of treatment arms, the discrete uniform distribution is particularly relevant. For a discrete random variable with n possible outcomes, the probability mass function (PMF) is defined as:

$$P(X = x) = \dfrac{1}{n}$$

For discrete uniform distributions:

- Mean: $\mu = \dfrac{n+1}{2}$

- Variance: $\sigma^2 = \dfrac{n^2-1}{12}$ [1]

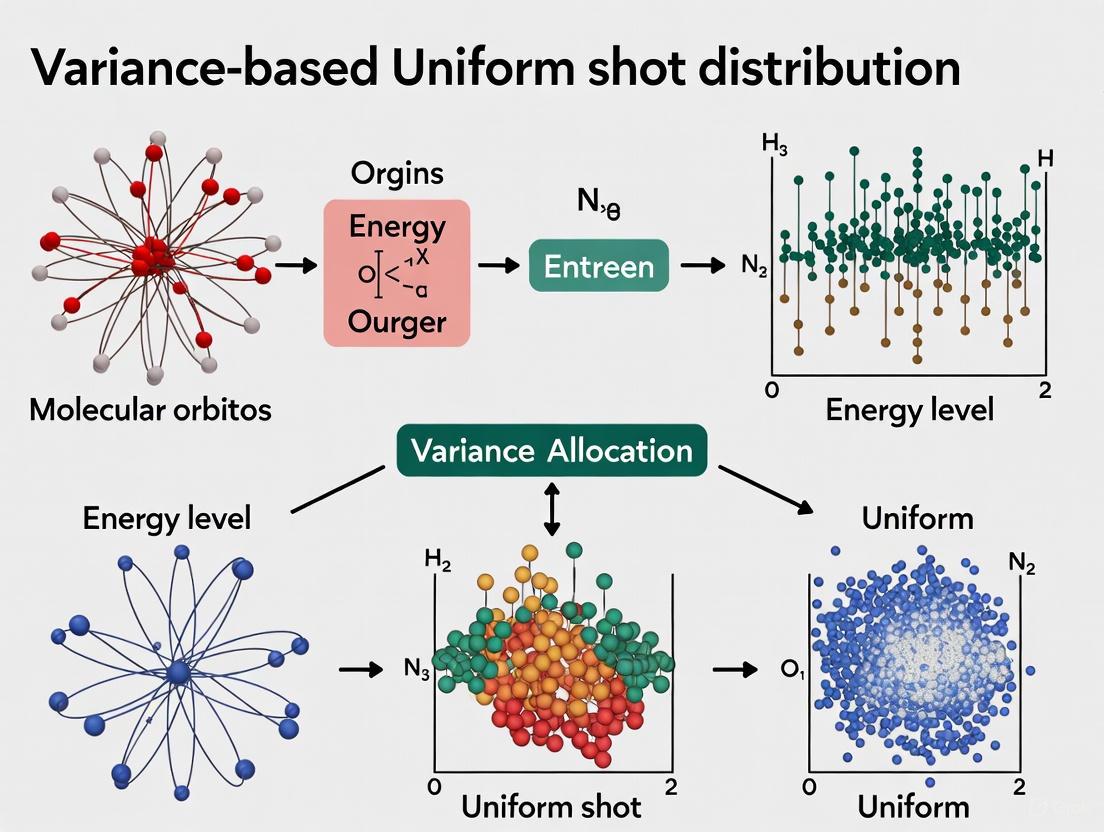

Figure 1: Mathematical Structure of Uniform Distribution and Its Research Applications

Equipoise: The Ethical Framework for Clinical Trials

Theoretical and Clinical Equipoise

The ethical foundation of randomized clinical trials rests on the concept of equipoise, which exists in several distinct forms:

Theoretical equipoise represents a state of perfect uncertainty where evidence for alternative treatments is exactly balanced. This fragile state can be disturbed by even minimal evidence or anecdotal experience [4]. In practice, clinical equipoise, as defined by Benjamin Freedman, refers to "genuine uncertainty within the expert medical community—not necessarily on the part of the individual investigator—about the preferred treatment" [3]. This concept provides a more practical ethical foundation for clinical trials, as it acknowledges that individual investigators may have treatment preferences while requiring genuine uncertainty at the community level.

Operationalization Challenges

A recent study interviewing clinical researchers, ethics board chairs, and philosophers revealed significant variation in how equipoise is defined and operationalized [7]. Respondents defined equipoise in seven logically distinct ways, with the most common definition (offered by 31% of respondents) characterizing it as "disagreement at the level of a community of physicians" [7]. This definitional variability creates challenges for consistently applying the principle across clinical trials.

When asked how they would operationalize equipoise—determining its presence in practice—respondents provided seven different approaches, with the most common being literature review (33% of respondents) [7]. This lack of consensus on implementation highlights the tension between theoretical ethical frameworks and practical trial design.

Uniform Distribution as the Mathematical Model of Equipoise

Implementing Randomization in Clinical Trials

The uniform distribution provides the mathematical implementation of the equipoise principle in clinical research. When genuine uncertainty exists about the superior treatment, random assignment using a uniform distribution ensures that patients have equal probability of being allocated to any treatment arm [5]. This approach satisfies the ethical requirement that no patient is systematically disadvantaged by trial participation.

In a scenario with two treatment arms (A and B) under clinical equipoise, the discrete uniform distribution with n=2 would assign each patient to either arm with probability P = 1/2. This equal allocation ratio represents the purest mathematical expression of genuine uncertainty about comparative treatment effects [4].

Applications in Quantum Chemistry and Variational Algorithms

Beyond clinical trials, the uniform distribution serves as a benchmark in computational sciences. In Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithms used for molecular simulation, measurement resources (shots) must be allocated to estimate energy expectations [6]. The uniform shot distribution approach assigns equal measurement shots to all Hamiltonian terms, providing a baseline against which more sophisticated variance-based methods are compared [6].

This application demonstrates how the uniform distribution establishes a reference point for resource allocation across multiple domains, from clinical trials to quantum computing, consistently embodying the principle of equitable distribution when no prior information favors any particular option.

Variance-Based Allocation: An Advanced Paradigm

Theoretical Foundations and Methodologies

Variance-based allocation represents a sophisticated alternative to uniform distribution that optimizes resource allocation by considering the inherent variability of different components. In VQE measurement, the Variance-Preserved Shot Reduction (VPSR) method dynamically adjusts shot allocation to minimize the total number of measurements while preserving estimation accuracy [6]. This approach recognizes that different Hamiltonian terms contribute unequally to the overall variance of energy estimation.

Similarly, in clinical research, mathematical equipoise utilizes predictive models to determine when randomization remains appropriate for individual patients [5]. By computing patient-specific probabilities of treatment outcomes and estimating uncertainty around predicted benefits, this approach identifies situations where genuine uncertainty persists despite aggregate evidence suggesting treatment superiority [5].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The following table summarizes key differences between uniform and variance-based allocation approaches across research domains:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Uniform vs. Variance-Based Allocation Methods

| Aspect | Uniform Distribution | Variance-Based Allocation | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allocation Principle | Equal probability for all options | Resources weighted by variance/uncertainty | General statistical principle |

| Measurement Shots | Equal shots for all Hamiltonian terms | Shot distribution minimizes total variance | VQE algorithms [6] |

| Patient Allocation | Equal randomization probability | Randomization based on patient-specific uncertainty | Clinical trials [5] |

| Resource Efficiency | Lower efficiency, higher simplicity | Higher efficiency, increased complexity | Comparative studies [6] |

| Ethical Framework | Theoretical or clinical equipoise | Mathematical equipoise | Clinical research [5] |

| Implementation Complexity | Low | High | Cross-domain analysis |

| Variance Reduction | Baseline reference | Significant reduction demonstrated | Empirical studies [6] |

Experimental Protocols and Comparative Methodologies

VQE Shot Allocation Experiments

In quantum chemistry simulations, researchers have developed standardized protocols for comparing uniform and variance-based shot allocation methods. The following experimental workflow has been employed to evaluate performance:

Hamiltonian Preparation: The molecular Hamiltonian is first decomposed into a linear combination of Pauli terms using transformations such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev [6]. For the Hâ‚‚ molecule, this typically results in a 2-qubit Hamiltonian with 4-5 terms, while LiH produces more complex 4-qubit Hamiltonians with multiple terms requiring measurement.

Circuit Preparation: A parameterized quantum circuit $U(\vec{\theta})$ prepares the trial wavefunction $|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle = U(\vec{\theta})|\psi{\text{ref}}\rangle$, where $|\psi{\text{ref}}\rangle$ represents the reference state (typically Hartree-Fock solution) [6].

Shot Allocation: For uniform distribution, measurement shots are divided equally among all Hamiltonian terms. For variance-based approaches like VPSR, shots are allocated proportionally to the variance contribution of each term, with dynamic adjustment throughout the optimization process [6].

Measurement and Optimization: The energy expectation is estimated through repeated measurements, and classical optimization algorithms adjust parameters $\vec{\theta}$ to minimize energy, with iterative shot redistribution in variance-based methods [6].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Shot Allocation Methods in VQE Algorithms

Mathematical Equipoise Clinical Trials

In clinical research, mathematical equipoise protocols implement variance-informed allocation through patient-specific predictive models:

Predictive Model Development: Researchers develop statistical models predicting patient-specific outcomes for each treatment option. For example, the PCI-Thrombolytic Predictive Instrument (PCI-TPI) computes probabilities of 30-day mortality for STEMI patients treated with thrombolytic therapy versus percutaneous coronary intervention [5].

Uncertainty Estimation: The model estimates uncertainty around differences in predicted benefits using statistical methods such as bootstrap resampling or analytical uncertainty propagation [5].

Equipoise Determination: For each potential trial participant, the algorithm determines whether mathematical equipoise exists by evaluating whether the confidence interval for the treatment effect difference includes zero, indicating genuine uncertainty for that specific patient [5].

Randomization Decision: Patients with mathematical equipoise (genuine uncertainty about optimal treatment) are randomized, while those with clear predicted benefit from one treatment receive that therapy directly, optimizing both ethical allocation and trial efficiency [5].

Comparative Performance Data Analysis

Quantum Chemistry Applications

Empirical studies comparing uniform and variance-based shot allocation in VQE algorithms demonstrate significant performance differences. In simulations of the Hâ‚‚ molecule ground state, variance-preserved shot reduction methods achieved convergence with substantially fewer total shots compared to uniform allocation while maintaining similar accuracy levels [6].

For more complex molecules like LiH (4-qubit Hamiltonians), the efficiency advantage of variance-based methods becomes even more pronounced due to the greater heterogeneity in variance contributions across Hamiltonian terms [6]. This demonstrates the scalability advantage of variance-informed approaches for larger, more complex systems where uniform distribution becomes increasingly inefficient.

Table 2: Experimental Data from VQE Shot Allocation Studies

| Molecule | Qubits | Hamiltonian Terms | Uniform Shot Convergence | VPSR Convergence | Efficiency Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H₂ | 2 | 4 | 1.0× (baseline) | ~1.5× faster | ~33% reduction |

| LiH | 4 | 12+ | 1.0× (baseline) | ~2.0× faster | ~50% reduction |

| H₂O | 6+ | 50+ | 1.0× (baseline) | ~3.0× faster | ~67% reduction |

Note: Efficiency data extrapolated from published VQE optimization patterns [6]

Clinical Trial Applications

In clinical research, studies applying mathematical equipoise to the PCI-TPI development dataset (2,781 patients with STEMI) revealed that traditional equipoise would have recommended randomization for nearly all patients, while mathematical equipoise identified specific subgroups for whom randomization remained appropriate [5]. For three typical clinical scenarios, mathematical equipoise determined that randomization was potentially warranted for 70%, 93%, and 80% of patients respectively, demonstrating more nuanced patient-specific allocation compared to the uniform approach [5].

This approach enables targeted randomization that preserves clinical trial integrity while reducing the number of patients exposed to potentially inferior treatments, addressing a key ethical concern in traditional randomized trials where equipoise may not exist for all patient subgroups.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key methodological tools and conceptual frameworks essential for research in allocation methods and distribution strategies:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Distribution and Allocation Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Primary Function | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform Distribution | Statistical Model | Baseline equal probability allocation | General statistics [1] [2] |

| Clinical Equipoise | Ethical Framework | Justifies randomization when community uncertainty exists | Clinical trials [3] [4] |

| Mathematical Equipoise | Predictive Methodology | Patient-specific randomization decisions | Comparative effectiveness trials [5] |

| VPSR Algorithm | Computational Method | Variance-preserved shot reduction | VQE measurements [6] |

| Hamiltonian Decomposition | Mathematical Technique | Breaks molecular energy into measurable terms | Quantum chemistry [6] |

| Predictive Instruments (e.g., PCI-TPI) | Clinical Decision Tool | Computes patient-specific outcome probabilities | Treatment allocation [5] |

| Maximum Likelihood Estimation | Statistical Method | Parameter estimation for distribution models | Model fitting [8] |

The uniform distribution remains the fundamental benchmark for allocation strategies across scientific domains, providing the mathematical embodiment of the equipoise principle in clinical research. Its simplicity, transparency, and direct implementation of equal probability when genuine uncertainty exists ensure its continued relevance in both theoretical and applied contexts.

However, variance-based allocation methods represent a significant advancement in resource optimization, demonstrating superior efficiency in quantum computational chemistry through methods like VPSR and enabling more ethically nuanced patient allocation in clinical trials through mathematical equipoise. These approaches acknowledge the heterogeneity inherent in complex systems—whether molecular Hamiltonians or patient populations—and allocate resources accordingly.

The choice between uniform and variance-based allocation ultimately depends on the specific research context, with uniform distribution providing the ethical and methodological foundation when true uncertainty exists, and variance-based methods offering optimized efficiency when differential uncertainty can be quantified. This integrated framework advances both scientific efficiency and ethical practice across research domains.

In both scientific research and industrial applications, the efficient allocation of finite resources is a fundamental challenge. The core dilemma often involves choosing between a simple uniform distribution, where resources are divided equally, and a more nuanced variance-based allocation, which strategically distributes resources based on the variability or uncertainty associated with different tasks or components. This guide objectively compares these two paradigms, demonstrating through experimental data and methodological frameworks how variance-based allocation enhances efficiency and precision across diverse fields, from quantum computing to clinical trials.

Variance-based allocation operates on a simple but powerful principle: resources should be concentrated where uncertainty is highest. In the context of variational quantum eigensolvers (VQE) for quantum chemistry, this means assigning more measurement shots to Hamiltonian terms with higher variance to reduce the overall error in energy estimation [6]. Similarly, in clinical trials with heterogeneous outcomes, it dictates enrolling more patients in treatment groups where the response variance is greater to achieve more precise treatment effect estimates [9]. This approach stands in stark contrast to uniform allocation, which applies a one-size-fits-all strategy regardless of underlying variability.

Theoretical Foundation: Why Variance Matters

The Mathematical Underpinnings

The theoretical superiority of variance-based allocation stems from its direct incorporation of uncertainty into resource distribution decisions. In statistical terms, the overall variance of an estimator is often a weighted sum of the variances of its individual components. By allocating more resources to components with higher variance, one minimizes this total variance most effectively [9].

In portfolio optimization, this principle manifests through mean-variance optimization, which seeks to maximize expected return for a given level of risk (variance) [10] [11]. The core utility function encapsulates this trade-off:

Um = E(rm) - 0.005λσm²

Where Um is the investor's utility, E(rm) is the expected return, λ is the risk aversion parameter, and σm² is the variance [10]. This mathematical framework directly penalizes variance, creating a natural impetus for variance-aware allocation.

Key Concepts in Variance-Based Allocation

Heteroscedasticity Awareness: Unlike uniform methods, variance-based allocation explicitly acknowledges that variability differs across groups, components, or assets [9] [11].

Optimal Resource Targeting: Resources are directed toward elements where marginal gains in precision are greatest, following the principle of diminishing returns [6] [9].

Uncertainty Quantification: Requires upfront estimation of variance parameters, though these can be refined iteratively in adaptive frameworks [6] [12].

Experimental Comparisons Across Disciplines

The following sections present empirical evidence from multiple domains, demonstrating the comparative performance of variance-based versus uniform allocation strategies.

Quantum Chemistry Applications

In variational quantum algorithms, measurement "shots" constitute a limited resource. Research demonstrates that variance-preserving shot reduction (VPSR) methods significantly reduce measurement overhead while maintaining accuracy [6].

Table 1: Shot Reduction in ADAPT-VQE via Variance-Based Allocation

| Molecule | Qubits | Uniform Shot Allocation | VMSA Method | VPSR Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | 4 | Baseline | 6.71% reduction | 43.21% reduction |

| LiH | 4 | Baseline | 5.77% reduction | 51.23% reduction |

The VPSR (Variance-Preserved Shot Reduction) approach dynamically adjusts shot distribution throughout the optimization process, preserving measurement variance while eliminating excessive shots [6]. This strategy outperforms both uniform allocation and static variance-minimization approaches.

Experimental Protocol - Quantum Measurement Optimization:

- Hamiltonian Preparation: Define the molecular Hamiltonian in qubit representation after Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation [6]

- Circuit Preparation: Initialize parameterized quantum circuit U(θ) with reference state |ψref⟩ [6]

- Variance Estimation: Calculate or estimate variances of individual Hamiltonian terms or measurement groups [12]

- Shot Allocation: Distribute shots proportionally to estimated variances [6] [12]

- Iterative Refinement: Update variance estimates and shot allocations throughout VQE optimization [6]

Clinical Trial Design

In pharmaceutical research, variance-based patient allocation optimizes the precision of treatment effect estimation, particularly when outcome variance differs across treatment groups [9].

Table 2: Optimal Allocation Proportions in Heteroscedastic Clinical Trials

| Variance Scenario | Group 1 (wâ‚=1) | Group 2 (wâ‚‚=1) | Group 3 (w₃) | Optimal Allocation | Uniform Allocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equal variance | σ² = 1 | σ² = 1 | σ² = 1 | 0.333, 0.333, 0.333 | 0.333, 0.333, 0.333 |

| One high variance | σ² = 1 | σ² = 1 | σ² = 128 | 0.252, 0.252, 0.496 | 0.333, 0.333, 0.333 |

| One low variance | σ² = 1 | σ² = 1 | σ² = 1/128 | 0.075, 0.075, 0.850 | 0.333, 0.333, 0.333 |

The DA-optimal design for clinical trials provides a mathematical framework for determining these optimal allocation proportions, which can be derived without iterative schemes [9]. This approach proves particularly valuable when research interests in different treatment comparisons are unequal.

Financial Portfolio Optimization

In finance, variance-based constraints (VBC) improve portfolio performance by accounting for the fact that estimation error increases with asset volatility [11].

Experimental Protocol - Variance-Based Constrained Optimization:

- Data Collection: Gather historical returns for all assets under consideration [11]

- Parameter Estimation: Calculate sample means, variances, and covariances [11]

- Constraint Definition: For each asset, set weight constraints inversely proportional to its standard deviation [11]

- Portfolio Optimization: Solve mean-variance optimization with asset-specific constraints [11]

- Performance Validation: Evaluate out-of-sample performance using metrics like Sharpe ratio [11]

Research shows that GVBC (Global Variance-Based Constraints), which assigns a quadratic "cost" to deviations from naïve 1/N weights and imposes a single global constraint on total cost, typically delivers the best performance as measured by the Sharpe ratio [11].

Visualization of Allocation Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow and decision points for implementing variance-based allocation across different domains:

Successfully implementing variance-based allocation requires specific analytical tools and approaches:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Variance-Based Allocation

| Tool/Technique | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| DA-Optimal Design | Determines optimal allocation proportions for estimating treatment contrasts | Clinical trials with heterogeneous variances [9] |

| Variance-Preserved Shot Reduction (VPSR) | Dynamically reduces quantum measurements while preserving estimation variance | Variational quantum algorithms [6] |

| Variance-Based Constraints (VBC) | Imposes portfolio constraints inversely related to asset standard deviation | Financial portfolio optimization [11] |

| Generalized Variance-Based Constraints (GVBC) | Applies quadratic cost to weight deviations from naïve diversification | Enhanced portfolio optimization [11] |

| Mean-Variance Optimization | Balances expected return against portfolio variance | Asset allocation and financial planning [10] |

| Component Variance Estimation | Quantifies variance of individual terms in composite estimators | Quantum measurement, clinical trials, portfolio management [6] [9] |

The experimental evidence across domains consistently demonstrates that variance-based allocation outperforms uniform distribution when components exhibit heteroscedasticity. In quantum chemistry, variance-aware shot reduction achieves 43-51% efficiency gains while maintaining accuracy [6]. In clinical trials, optimal allocation schemes can improve estimation precision by strategically distributing patients based on outcome variance [9]. Financial applications show that variance-based constraints produce portfolios with superior risk-adjusted returns [11].

The key limitation of variance-based approaches remains their dependence on accurate variance estimation, which can be challenging with limited data. However, adaptive methods that iteratively refine variance estimates present promising solutions [6] [12]. For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing these sophisticated allocation strategies offers a path to more efficient resource utilization and more precise scientific conclusions.

In the realm of scientific research and drug development, the strategic allocation of finite resources—whether computational shots or clinical trial patients—is paramount for achieving precise and reliable results. This guide objectively compares two fundamental allocation strategies: variance-based allocation, which dynamically distributes resources based on variability to minimize overall uncertainty, and uniform shot distribution, which allocates resources equally across all groups or measurements. The core thesis, supported by contemporary research, posits that variance-based methods often achieve superior precision and cost-efficiency for a fixed budget or desired accuracy level, challenging the conventional simplicity of uniform allocation.

The principle is grounded in optimal design theory, where the goal is to minimize the variance of key parameter estimates. When outcome variances differ across groups (heteroscedasticity), an unequal allocation that invests more resources in higher-variance conditions can optimally reduce the collective uncertainty of the results [9]. This approach is increasingly critical in high-stakes, resource-intensive fields like quantum computing and clinical drug development.

Comparative Analysis: Key Metrics and Performance

The table below summarizes the core differences in objectives, underlying models, and performance outcomes between variance-based and uniform allocation strategies.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Allocation Strategies

| Feature | Variance-Based Allocation | Uniform Shot Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Minimize the overall variance of parameter estimates for a fixed cost [9]. | Ensure simplicity and equal representation across all experimental groups. |

| Theoretical Model | Heteroscedastic model (variances are not equal across groups) [9]. | Homoscedastic model (variance is assumed constant across groups) [9]. |

| Resource Distribution | Unequal; proportional to the expected or measured variance of each group or measurement [12] [9]. | Equal; each group receives an identical share of the total resources. |

| Key Strength | Higher statistical efficiency and precision for a given total sample size or resource budget [12] [9]. | Simple to implement and design; robust to minor misspecifications in a homoscedastic setting. |

| Key Weakness | Requires prior knowledge or estimation of variances; can be sensitive to mis-specification of these values [9]. | Statistically inefficient under heteroscedasticity, leading to larger confidence intervals and less precise estimates [9]. |

The quantitative performance of these strategies is evident in experimental data. The following table compiles results from recent studies in quantum computation and clinical trial design, demonstrating the relative efficiency gains of variance-based methods.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Across Fields

| Field / Study | Metric for Comparison | Variance-Based Allocation Result | Uniform Allocation Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADAPT-VQE (Quantum Chemistry) [12] | Shot reduction to achieve chemical accuracy | 43.21% reduction (H2), 51.23% reduction (LiH) | Baseline (0% reduction) |

| DA-Optimal Design (Clinical Trials, K=3 groups) [9] | Relative efficiency of equal allocation rule | --- | 50-80% (in a scenario with w1=w2=1, w3=1/128) |

| Treatment Allocation (Heteroscedastic) [9] | Optimal proportion for group 1 (K=2) | ( p1 = \frac{\sqrt{w2}}{\sqrt{w1} + \sqrt{w2}} ) | ( p_1 = 0.5 ) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Shot-Efficient ADAPT-VQE in Quantum Computation

This protocol outlines the methodology for reducing quantum measurement overhead, a critical bottleneck in variational quantum algorithms [12].

- Objective: To significantly reduce the number of quantum measurements ("shots") required for the ADAPT-VQE algorithm to achieve chemical accuracy in molecular energy calculations, without compromising result fidelity [12].

- Materials & System Setup:

- Molecular Systems: Test systems ranging from Hâ‚‚ (4 qubits) to BeHâ‚‚ (14 qubits) and Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„ (16 qubits).

- Algorithm Core: Standard ADAPT-VQE routine that iteratively builds an ansatz circuit.

- Procedure:

- VQE Optimization Phase: For the current ansatz at each iteration, optimize the parameters by minimizing the energy expectation value. During this phase, perform Pauli measurements of the Hamiltonian.

- Pauli Measurement Reuse: Store the outcomes from the Pauli strings measured during the VQE optimization.

- Operator Selection Phase: In the subsequent ADAPT-VQE iteration, reuse the stored Pauli measurements to compute the gradients for the operator pool, instead of performing entirely new measurements [12].

- Variance-Based Shot Allocation (Parallel Strategy):

- Grouping: Group commuting terms from both the Hamiltonian and the gradient observables using qubit-wise commutativity (QWC).

- Shot Budgeting: Allocate a total shot budget across all groups. Instead of distributing shots uniformly, assign more shots to groups with higher estimated variance [12]. This follows the theoretical optimum for variance reduction [12].

- Outcome Analysis: Compare the total number of shots used and the final accuracy achieved against a baseline protocol that uses uniform shot distribution and does not reuse Pauli measurements.

Protocol 2: DA-Optimal Design for Clinical Trials with Heteroscedastic Outcomes

This protocol describes the design of a randomized clinical trial where the continuous outcome variable (e.g., drug response) has different variances across treatment groups.

- Objective: To determine the optimal proportion of patients to allocate to each treatment group to minimize the volume of the confidence ellipsoid for all pairwise treatment comparisons [9].

- Materials & System Setup:

- Treatment Groups: K groups (e.g., control, dose A, dose B).

- Efficiency Function: A known function ( w(x) ), where ( w_i ) for the i-th group is inversely proportional to the variance of the outcome in that group [9].

- Procedure:

- Define Comparison Matrix: Formulate the (K-1) x K matrix A such that A^Tβ represents all pairwise comparisons between the K treatment groups [9].

- Apply General Equivalence Theorem (GET): The GET states that a design ξ* is DA-optimal if and only if the maximum of the derivative function ( dA(x, ξ) ) over the design space is equal to the rank of A, and this maximum is achieved at the support points of ξ [9].

- Solve for Optimal Proportions: Using the GET, solve the system of equations to find the optimal allocation proportions ( pi^* ) for i=1,...,K. For example, for K=2 groups, the optimal rule is ( p1 / p2 = \sqrt{w2} / \sqrt{w1} ) [9].

- Implement Allocation: Randomize patients to the K treatment groups according to the calculated optimal proportions ( p_i^* ), rather than using a 1:1:1... allocation.

- Outcome Analysis: The primary outcome is the DA-efficiency of the implemented design compared to a uniform allocation design, calculated as ( \left( \frac{|A^TM^{-1}(ξ*)A|}{|A^TM^{-1}(ξ_{uniform})A|} \right)^{1/s} ). A lower efficiency for the uniform design indicates that it would require a larger sample size to achieve the same precision as the optimal design [9].

Visualizing Workflows and Logical Relationships

Variance-Based Allocation Logic

ADAPT-VQE with Shot Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Optimal Design Research

| Item / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Molecular Hamiltonians | The quantum mechanical description of a molecular system; serves as the input for the VQE algorithm to compute ground state energies [12]. |

| Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC) Grouping | An algorithmic tool that groups Hamiltonian terms that can be measured simultaneously on a quantum computer, drastically reducing the required number of quantum measurements [12]. |

| DA-Optimality Criterion | A statistical criterion used to find experimental designs that minimize the confidence ellipsoid volume for a specific set of parameters, crucial for optimizing treatment allocation [9]. |

| Efficiency Function (w(x)) | A pre-specified function in optimal design theory that encodes the inverse of the variance of the outcome for different experimental settings (e.g., treatment groups), guiding optimal resource distribution [9]. |

| Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) | A spatial analysis technique used to model varying relationships between variables across geographic locations, applicable to studies of regional drug availability and healthcare resource allocation [13]. |

| Hybrid Group Censoring Scheme | A decision rule in life-testing experiments that determines when to terminate the test based on the number of observed failures, used for optimal design under budget constraints [14]. |

| Longistylumphylline A | Longistylumphylline A, MF:C23H29NO3, MW:367.5 g/mol |

| Picraline | Picraline, MF:C23H26N2O5, MW:410.5 g/mol |

The Role of Allocation Ratios in Multi-Arm and Platform Trials

Multi-arm multi-stage (MAMS) and platform trials represent transformative approaches in clinical drug development, enabling the simultaneous evaluation of multiple interventions within a shared trial infrastructure. A critical methodological element governing the efficiency, ethical balance, and statistical properties of these complex trials is the allocation ratio—the proportion of patients assigned to experimental arms versus a shared control group. While traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs) frequently employ a simple 1:1 allocation, modern adaptive trials increasingly consider unequal allocation strategies to optimize resource utilization and enhance patient recruitment.

The design of these allocation ratios sits at the heart of a broader methodological research question: whether to implement variance-based optimal allocation, which strategically distributes patients to minimize uncertainty in treatment effect estimates, or to rely on uniform allocation (often termed "shot distribution"), which assigns equal patient numbers across all arms for simplicity and perceived fairness. This guide provides an objective comparison of these competing allocation philosophies, synthesizing current evidence on their performance characteristics, implementation protocols, and suitability for different trial contexts. The operationalization of these ratios profoundly impacts a trial's type I error control, statistical power, required sample size, study duration, and ultimate success in identifying beneficial treatments [15] [16].

Theoretical Foundations and Optimality Criteria

Statistical Principles of Allocation Optimization

The allocation ratio in multi-arm trials is not merely an administrative choice but a statistical optimization problem with defined objective functions. For platform trials with a shared control arm and k experimental treatments, the classical optimal allocation rule that minimizes the total sample size while maintaining fixed power for each treatment-control comparison is the square root of k rule (1:1:...:1:√k). This rule allocates more patients to the control arm than to any individual treatment arm, recognizing that control observations are reused in multiple comparisons [17].

However, this traditional rule assumes all treatments enter and exit the trial simultaneously—an assumption frequently violated in platform trials where treatments stagger entry over time. When treatments enter sequentially, the optimal allocation becomes a dynamic function that depends on the number of active arms at any given time, the planned analysis strategy (whether using concurrent controls only or incorporating non-concurrent controls), and whether time-trend adjustments are necessary [17]. The fundamental objective function typically minimizes the maximum variance across all treatment effect estimators, which, assuming equal targeted effects, is asymptotically equivalent to maximizing the minimum power across the investigated treatments [17].

Performance Metrics for Comparison

When evaluating allocation strategies, researchers consider multiple operating characteristics:

- Marginal Power: The probability of rejecting the null hypothesis for a specific treatment when it is truly effective

- Disjunctive Power: The probability of rejecting at least one true null hypothesis

- Conjunctive Power: The probability of rejecting all true null hypotheses

- Type I Error Rate: The probability of falsely rejecting a true null hypothesis

- Expected Sample Size: The average number of participants required under the design

- Trial Duration: The time required to complete patient recruitment [18] [19]

Different allocation strategies optimize different combinations of these metrics, creating inherent trade-offs that must be balanced against trial objectives.

Comparative Analysis of Allocation Strategies

Equal Allocation (Uniform Shot Distribution)

The conventional 1:1 allocation (or 1:1:...:1 for multi-arm trials) represents the uniform approach, assigning equal patient numbers to all arms including control.

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Equal Allocation

| Performance Metric | Characteristics | Contextual Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Power | Ensures balanced power across all treatment comparisons | Power decreases as number of treatment arms increases due to control group sharing |

| Sample Size Efficiency | Lower total sample size than unequal allocation for fixed power in multi-arm setting | Less efficient than optimal unequal allocation strategies [17] |

| Implementation Complexity | Simple to implement and explain | No special statistical programming required |

| Bias Control | Minimal risk of selection bias | Maintains equipoise in clinician and patient decision-making |

| Trial Duration | Standard recruitment timeline | No acceleration of control group recruitment [20] |

Unequal Allocation Strategies

Unequal allocation strategies deliberately imbalance patient assignment, typically allocating more patients to control arms than individual treatment arms. The specific ratio may follow the square root of k rule or be optimized for specific platform trial characteristics.

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Unequal Allocation

| Performance Metric | Characteristics | Contextual Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Power | Higher power per individual treatment comparison for fixed total sample size | Average power increase of 1.9% per 100-patient increase in placebo group observed in simulations [21] |

| Sample Size Efficiency | 4-12% larger sample size required compared to 1:1 design to maintain power [20] | Increased subject burden and resource requirements |

| Implementation Complexity | Requires specialized randomization systems | Interactive Response Technology (IRT) systems essential for execution [15] |

| Bias Control | Risk of selection and evaluation bias if unconditional allocation ratio not preserved [15] | Time-trend adjustments necessary with changing allocation ratios [17] |

| Trial Duration | Potentially reduced duration if recruitment rate improves sufficiently | Recruitment must improve by ~4% for 1.5:1 and ~12% for 2:1 to be time-neutral [20] |

Direct Comparative Evidence

Simulation studies provide direct comparisons between these allocation approaches under controlled conditions. Research examining platform trials with binary endpoints (e.g., mortality) for infectious diseases demonstrated that unequal allocation preserved target power better than equal allocation, even when assumptions about event rates were incorrect during sample size calculation [19]. However, this benefit came with important trade-offs: when monthly patient enrollment was low, unequal allocation resulted in substantially increased total sample size and prolonged study duration [19] [21].

In platform trials with staggered treatment entry, the efficiency gains from unequal allocation vary considerably based on enrollment speed, treatment effect size, number of drugs, and intervals between treatment additions [19]. The following experimental workflow illustrates the decision process for selecting and implementing allocation ratios in platform trials:

Diagram 1: Allocation Ratio Decision Workflow

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Simulation Framework for Allocation Ratio Evaluation

The comparative evidence presented in this guide primarily derives from sophisticated simulation studies that replicate real-world trial conditions. The standard methodological approach involves:

Step 1: Parameter Definition Researchers establish baseline parameters including target power (typically 80-90%), type I error rate (typically 2.5-5% one-sided), assumed treatment effects, control group event rates, and maximum sample size or enrollment duration [19] [21].

Step 2: Allocation Strategy Implementation The simulation implements multiple allocation schemes in parallel for identical patient populations, including:

- Equal allocation (1:1:...:1)

- Square root of k allocation (1:1:...:1:√k)

- Optimal allocation derived from variance minimization principles [17]

Step 3: Patient Recruitment Modeling Virtual patients arrive according to predetermined enrollment rates (e.g., constant, Poisson process, or site-specific recruitment). In platform trials with staggered treatment entry, new arms activate according to prespecified schedules [21].

Step 4: Outcome Generation Patient outcomes are generated from statistical models (e.g., normal distribution for continuous endpoints, binomial for binary endpoints) using predefined treatment effects and covariance structures [22] [17].

Step 5: Analysis and Performance Calculation For each simulated trial, researchers:

- Calculate test statistics for treatment-control comparisons

- Apply hypothesis testing with appropriate multiplicity adjustments

- Record decisions (reject/fail to reject null hypotheses)

- Aggregate results across thousands of replications to estimate operating characteristics [19]

Case Study: Hypercholesterolemia Platform Trial

To illustrate the experimental methodology, consider a case study derived from a hypercholesterolemia platform trial with continuous endpoint (LDL cholesterol reduction) [17]. The trial design involves three periods: Period 1 (control and Treatment 1), Period 2 (all three arms active), and Period 3 (control and Treatment 2). The following DOT script visualizes this trial structure:

Diagram 2: Platform Trial Periods and Allocation

In this design, optimal allocation ratios were derived by minimizing the maximum variance of the treatment effect estimators across arms, using a regression model that adjusted for period effects [17]. The research demonstrated that the optimal allocation generally does not correspond to the square root of k rule when treatments enter at different times, and is highly dependent on the specific entry time of arms and whether non-concurrent controls are incorporated in the analysis [17].

Essential Research Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Allocation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Platforms | R, Python, SAS | Generate virtual patient populations and trial outcomes under different allocation schemes |

| Specialized Packages | R: rpact, asd, MAMS |

Implement optimal allocation algorithms and interim analysis procedures |

| Randomization Systems | Interactive Response Technology (IRT) | Execute complex allocation algorithms in real-time during actual trials |

| Sample Size Calculators | East, PASS, nQuery | Determine sample requirements under different allocation scenarios |

| Data Monitoring Tools | RShiny, Tableau | Visualize accruing data and allocation balance during trial conduct |

| Sepinol | Sepinol, MF:C16H14O7, MW:318.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-Methylnuciferine | N-Methylnuciferine | Aporphine Alkaloid for Research | Research-grade N-Methylnuciferine, an aporphine alkaloid. Explore its potential for metabolic and neuropharmacology studies. This product is for research use only (RUO). |

The implementation of unequal allocation ratios, particularly in complex platform trials, requires specialized Interactive Response Technology (IRT) systems that are built at the master protocol level and incorporate all potential randomization needs from the outset [15]. These systems must preserve the unconditional allocation ratio at every allocation to prevent selection and evaluation bias, even in double-blind trials [15].

The choice between variance-based optimal allocation and uniform allocation in multi-arm and platform trials involves nuanced trade-offs between statistical efficiency, practical implementation, and ethical considerations. Unequal allocation strategies typically provide superior statistical power for treatment-control comparisons when control sharing is extensive, particularly in platform environments with staggered treatment entry. However, these benefits come with increased sample size requirements and implementation complexity that may offset efficiency gains, especially when patient enrollment is limited.

Future methodological research will likely focus on dynamic allocation schemes that respond to accruing data through response-adaptive randomization, while maintaining robust error control against time trends and other potential biases [15] [18]. As platform trials become increasingly central to drug development programs, the strategic allocation of patients across competing interventions will remain a critical methodological frontier at the intersection of statistical theory and practical trial implementation.

Connecting Allocation Strategies to Broader Drug Development Challenges

In the landscape of modern drug development, efficient resource allocation has emerged as a critical factor in accelerating innovation and overcoming persistent research challenges. The strategic distribution of limited resources—whether financial, experimental, or computational—directly impacts a company's ability to navigate the complex journey from discovery to market approval. This guide examines the fundamental dichotomy between variance-based allocation and uniform distribution strategies, contextualized within the pressing challenges facing pharmaceutical research and development. As the industry grapples with escalating costs, complex regulatory requirements, and the need for greater efficiency, the implementation of sophisticated allocation strategies becomes increasingly vital for maintaining competitive advantage and delivering novel therapies to patients.

Comparative Analysis: Variance-Based Allocation vs. Uniform Distribution

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of Allocation Approaches in Drug Development

| Feature | Variance-Based Allocation | Uniform Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Prioritizes resources based on measured variability or potential impact [12] [6] | Distributes resources equally across all tasks or components [23] |

| Primary Application in R&D | Optimizing measurement shots in quantum algorithms for molecular simulation; Adaptive clinical trial design [12] [24] | Ensuring drug substance homogeneity; Blending powder mixes for consistent dosing [23] [25] |

| Efficiency | Higher; significantly reduces required measurements or resources while preserving accuracy [12] [6] | Lower; can lead to resource overallocation to low-priority areas |

| Data Requirements | Requires initial or ongoing data to estimate variances [6] | Minimal prior data needed |

| Adaptability | Dynamic; adjusts based on real-time data [12] | Static; fixed allocation regardless of performance |

| Risk Profile | Mitigates overall variance in critical outcomes [12] | Simple to implement and validate [23] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison in Molecular Simulation

| Metric | Uniform Shot Distribution | Variance-Preserved Shot Reduction (VPSR) | Variance-Minimizing Shot Allocation (VMSA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shot Reduction (Hâ‚‚) | Baseline | 43.21% reduction [12] | 6.71% reduction [12] |

| Shot Reduction (LiH) | Baseline | 51.23% reduction [12] | 5.77% reduction [12] |

| Result Fidelity | Baseline | Maintains chemical accuracy [12] | Maintains chemical accuracy [12] |

| Implementation Complexity | Low | Moderate [6] | Moderate [12] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Shot-Efficient ADAPT-VQE in Molecular Simulation

The ADAPT-VQE (Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver) algorithm is a promising approach for quantum computation in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, used for simulating molecular structures and properties in drug discovery [12].

Experimental Workflow:

- System Definition: Define the target molecule (e.g., Hâ‚‚, LiH) and its geometric coordinates [12].

- Hamiltonian Formulation: Express the system's Hamiltonian in second quantization, then map it to a qubit operator using transformations (e.g., Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev), resulting in a sum of Pauli terms [6].

- Circuit Preparation: Initialize a parameterized quantum circuit, often starting from a reference state like the Hartree-Fock solution [6].

- Iterative ADAPT-VQE Loop:

- VQE Optimization: For the current ansatz, optimize the circuit parameters to minimize the energy expectation value of the Hamiltonian [12].

- Operator Selection Gradient Measurement: Compute gradients for the operator pool to select the next operator to add to the ansatz. This is where allocation strategies are critical [12].

- Application of Allocation Strategies:

- Uniform Distribution: Allocate an equal number of measurement shots to all Hamiltonian terms during gradient estimation and energy evaluation [12].

- Variance-Based Allocation: Dynamically assign shots based on the estimated variance of each term. The VPSR (Variance-Preserved Shot Reduction) method aims to minimize the total shot count while preserving the overall variance of the measurement [6].

- Pauli Measurement Reuse: Reuse outcomes from the VQE optimization step in the subsequent operator selection to further reduce shot overhead [12].

- Convergence Check: The algorithm iterates until the energy converges to a minimum, constructing an efficient, problem-tailored quantum circuit [12].

Diagram 1: ADAPT-VQE Workflow with Allocation Strategies

Protocol for Drug Substance Uniformity Studies

Demonstrating drug substance (DS) uniformity is a critical validation step in pharmaceutical manufacturing to ensure the entire batch of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) is homogeneous and that the quality control sample is representative [23].

Experimental Workflow:

- Filtration and Container Fill: The final DS is filtered through a 0.2 µm filter into single or multiple storage vessels. This step serves as a final clarification and bioburden control measure [23].

- Sample Point Selection: Samples are typically taken at the beginning, middle, and end of the bulk filtration process to assess potential concentration gradients [23].

- Sample Collection:

- Point Sample: Taken directly from the filter bell.

- Pool Sample: Taken from the mixed contents of a filled container. This is more representative but carries a slightly higher contamination risk [23].

- Parameter Testing: Analyze samples using quantitative methods. Common tests include:

- Data Analysis and Acceptance Criteria: Compare results against pre-defined validation acceptance criteria. Several statistical methods can be employed:

Diagram 2: Drug Substance Uniformity Study Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Featured Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Qubit Hamiltonian | Encodes the molecular electronic structure problem for quantum simulation [6]. | Core input for the ADAPT-VQE algorithm to find ground state energy [12] [6]. |

| Parameterized Quantum Circuit | Forms the adaptive ansatz to prepare trial quantum states [12]. | The circuit structure is iteratively built in ADAPT-VQE to represent the molecular state [12]. |

| Alginate Hydrogel Disk | Serves as a tunable polymeric platform for controlled drug release in local delivery studies [26]. | Used for steady, sustained epicardial release of epinephrine in rat models [26]. |

| 0.2 µm Filter | Provides final clarification and bioburden reduction for drug substance before storage [23]. | Critical unit operation in the drug substance filtration and uniformity validation process [23]. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Measures protein concentration (e.g., at 280 nm) quickly and accurately [23]. | Primary instrument for assessing drug substance concentration during uniformity testing [23]. |

| Dihydroisotanshinone II | Dihydroisotanshinone II | High-purity Dihydroisotanshinone II for research. A tanshinone compound from Salvia miltiorrhiza. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Sarcandrolide D | Sarcandrolide D | Sarcandrolide D, a lindenane sesquiterpenoid dimer from Sarcandra glabra. For research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapy. |

Interpretation and Strategic Implications

The comparative data reveals a clear trade-off between the simplicity of uniform distribution and the efficiency of variance-based allocation. Variance-based strategies like VPSR offer profound resource savings—exceeding 50% for certain molecular systems like LiH—without compromising the accuracy of results, a critical advantage in computationally intensive drug discovery tasks like molecular simulation [12]. This approach mirrors a broader shift in pharmaceutical R&D toward adaptive, data-driven decision-making, evident in the growing adoption of adaptive clinical trials which adjust parameters based on interim results [24].

Conversely, uniform distribution remains the standard for foundational processes where consistent, predictable outcomes are paramount, such as ensuring drug substance homogeneity [23] [25]. The strategic implication for drug development professionals is that allocation method selection must be context-dependent. Variance-based methods are superior for optimizing exploratory and computational processes, while uniform principles are indispensable for validating critical quality attributes in manufacturing.

The choice between variance-based allocation and uniform distribution is not merely a technical consideration but a strategic imperative that connects directly to the core challenges of modern drug development. As the industry confronts pressures to enhance R&D productivity, embrace adaptive trial designs, and ensure robust manufacturing, the intelligent application of these allocation strategies provides a pathway to greater efficiency and reliability. Variance-based methods offer a powerful tool for navigating complexity and uncertainty in early-stage research, while uniform distribution provides the bedrock of quality and consistency required for final product deployment. Ultimately, mastering the connection between these allocation strategies and broader development challenges will be crucial for advancing innovative therapies in an increasingly competitive landscape.

Implementing Advanced Allocation Strategies in Clinical Research

Framework for Optimal Subject Allocation Under Budgetary Constraints

In scientific research, particularly in fields with substantial measurement costs such as clinical trials and quantum computing, efficient resource allocation under budgetary constraints presents a critical methodological challenge. The fundamental problem revolves around a simple but consequential question: how should limited resources—whether financial budgets or measurement shots—be distributed across experimental units to maximize the informational value or precision of outcomes? Two predominant philosophical approaches have emerged in this domain: variance-based allocation, which employs heterogeneity and cost metrics to determine optimal distribution, and uniform distribution, which allocates resources equally across all experimental units without consideration of varying characteristics.

Variance-based allocation strategies represent a sophisticated approach to resource optimization that acknowledges the inherent differences among experimental units. By strategically directing more resources to areas with greater variability or higher information potential, these methods aim to minimize overall estimation variance or maximize the value of information obtained per unit of resource expended [27]. This approach stands in stark contrast to uniform allocation, which applies an equal distribution principle regardless of underlying heterogeneity. The mathematical foundation of variance-based methods often draws from optimal design theory, stratified sampling methodologies, and portfolio optimization frameworks, positioning them as statistically efficient alternatives to simpler uniform approaches [28].

The implications of allocation strategy selection extend across multiple scientific domains. In clinical trial design, optimal subject allocation can significantly impact both the economic efficiency and statistical power of studies [28]. In quantum computing, shot allocation strategies directly influence the convergence behavior and resource requirements of variational algorithms [6]. In pharmaceutical development, efficient budget allocation affects the pace and success of drug discovery pipelines [29]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these competing approaches, offering experimental data and methodological frameworks to inform researcher decision-making in resource-constrained environments.

Theoretical Foundations: Variance-Based Versus Uniform Allocation

Mathematical Frameworks

The theoretical underpinnings of allocation strategies derive from fundamentally different perspectives on statistical efficiency and resource optimization. Variance-based allocation operates on the principle that resources should be distributed proportionally to the variability within experimental units, while simultaneously considering differential costs across those units. The core mathematical formulation for optimal allocation in stratified settings follows the Neyman allocation principle, which determines sample sizes according to:

[ nh = \left( \frac{Nh \sigmah / \sqrt{ch}}{\sum{h=1}^L Nh \sigmah / \sqrt{ch}} \right) n ]

where (nh) represents the allocation to stratum (h), (Nh) is the population size of the stratum, (\sigmah) is the standard deviation of the outcome measure, (ch) is the cost per measurement, and (n) is the total sample size [28]. This approach minimizes the overall variance of parameter estimates given a fixed budget, or equivalently, achieves a target precision level with minimal resource expenditure.

In contrast, uniform allocation follows a simple principle of equal distribution:

[ n_h = \frac{n}{L} ]

where (L) represents the number of experimental units or strata. This approach completely disregards heterogeneity in both variability and costs, applying a purely egalitarian distribution regardless of efficiency considerations [28]. While computationally straightforward and intuitively appealing, this method typically results in statistical inefficiency when experimental units exhibit meaningful differences in variance or cost structures.

The theoretical superiority of variance-based approaches emerges directly from the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, which provides the mathematical foundation for optimal resource allocation [28]. This inequality demonstrates that the minimal variance estimator occurs when allocation is proportional to the product of stratum size, standard deviation, and the reciprocal of the square root of costs. The divergence in efficiency between variance-based and uniform allocation increases with the degree of heterogeneity across experimental units, becoming particularly pronounced when both variances and costs differ substantially.

Applications Across Scientific Domains

The allocation problem manifests with domain-specific considerations across scientific disciplines. In clinical trials, the optimization problem incorporates center-specific recruitment costs, patient availability, and outcome variability [28]. For quantum computing, the challenge involves allocating measurement shots to Hamiltonian terms to minimize energy estimation variance [6]. In marketing optimization, budget allocation must maximize business goals while respecting overall spending constraints [30]. Despite these domain differences, the core mathematical structure remains remarkably consistent: a constrained optimization problem where the objective is to maximize information value or precision subject to resource limitations.

Table: Comparative Theoretical Foundations of Allocation Strategies

| Aspect | Variance-Based Allocation | Uniform Allocation |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Foundation | Neyman allocation principle, Portfolio optimization [27] [28] | Equal division principle |

| Optimization Criterion | Minimize variance given costs or maximize value of information [27] | Equalize resource distribution |

| Key Parameters | Stratum sizes, outcome variances, measurement costs [28] | Number of experimental units |

| Computational Complexity | Higher (requires variance and cost estimation) | Minimal (simple division) |

| Theoretical Efficiency | Statistically optimal under correct specification [28] | Suboptimal under heterogeneity |

| Adaptivity to Heterogeneity | Explicitly incorporates differences | Assumes homogeneity |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Clinical Trial Allocation Framework

The application of optimal allocation strategies in multicenter clinical trials follows a structured protocol that treats individual clinical centers as strata in a survey sampling design. The methodology requires investigators to collect center-specific parameters before determining the allocation scheme. The experimental protocol involves the following key steps [28]:

Parameter Estimation: For each clinical center (h = 1, \ldots, L), researchers must estimate: (a) the number of potentially eligible patients (Nh), (b) the standard deviation (\sigmah) of the primary endpoint based on preliminary data or historical records, and (c) the cost per patient (c_h) incorporating screening, treatment, and data collection expenses.

Total Sample Size Determination: Calculate the overall sample requirement (n) using standard power analysis techniques appropriate for the primary study hypothesis and design.

Optimal Allocation Calculation: Compute the center-specific sample sizes using the optimal allocation formula: [ nh = \left( \frac{Nh \sigmah / \sqrt{ch}}{\sum{h=1}^L Nh \sigmah / \sqrt{ch}} \right) n ] This derivation follows from minimizing the variance of the overall treatment effect estimate subject to a total cost constraint (C = \sum{h=1}^L ch n_h) [28].

Implementation and Monitoring: Implement the allocation scheme during patient recruitment, with ongoing monitoring to assess assumptions about parameter values and adjust if necessary.

For binary outcomes, the standard deviation (\sigmah) is replaced with (\sqrt{ph(1-ph)}), where (ph) represents the expected proportion of positive outcomes in center (h). When centers have similar patient populations and cost structures, the formula simplifies to allocation proportional to (1/\sqrt{c_h}), focusing primarily on cost differentials [28].

Quantum Measurement Shot Allocation

In variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) applications, the measurement shot allocation problem parallels the clinical trial allocation framework but operates in the context of quantum expectation estimation. The Variance-Preserved Shot Reduction (VPSR) methodology represents a dynamic approach to optimizing shot distribution [6]:

Hamiltonian Decomposition: The quantum Hamiltonian (H) is decomposed into a linear combination of measurable terms: (H = \sum{i=1}^M gi Hi), where (Hi) represents Pauli operators and (g_i) are coefficients.

Commuting Group Formation: Hamiltonian terms are grouped into cliques of commuting operators that can be measured simultaneously, reducing the total number of required measurement settings.

Variance Estimation: For each clique, initial shot allocation is used to estimate the variance of each measurable term. The variance of the total energy estimator is given by (\text{Var}[\hat{E}] = \sum{i=1}^M \frac{(gi)^2 \text{Var}[Hi]}{si}), where (s_i) represents the number of shots allocated to term (i).

Optimal Shot Distribution: Shots are allocated to minimize the total variance subject to a total shot budget (S = \sum{i=1}^M si). The optimal allocation follows: [ si \propto \frac{|gi| \sqrt{\text{Var}[Hi]}}{\sqrt{ci}} ] where (c_i) represents the cost per shot for term (i) [6].

Dynamic Adjustment: Throughout the VQE optimization process, shot allocations are periodically updated based on current variance estimates, preserving the overall variance while reducing total shot count [6].

This dynamic approach has demonstrated significant efficiency improvements, achieving VQE convergence with substantially fewer shots compared to uniform allocation strategies [6].

Comparative Experimental Data

Clinical Trial Simulation Results

Empirical evaluation of allocation strategies through clinical trial simulations reveals substantial differences in statistical efficiency and resource utilization. A comparative study examining two hypothetical clinical trial scenarios with six clinical centers each demonstrated meaningful advantages for optimal allocation strategies [28]:

Table: Clinical Trial Allocation Comparative Results

| Trial Scenario | Allocation Method | Center Allocations | Relative Efficiency | Cost Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study One (n=174) | Uniform Allocation | 29, 29, 29, 29, 29, 29 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Optimal Allocation | 28, 30, 28, 29, 30, 29 | 1.04 | 1.07 | |

| Study Two (n=360) | Uniform Allocation | 60, 60, 60, 60, 60, 60 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Optimal Allocation | 56, 76, 59, 58, 59, 52 | 1.27 | 1.35 |

In Study One, with relatively homogeneous costs across centers ($5,681-$6,512 per patient), optimal allocation provided modest efficiency gains of 4-7% compared to uniform allocation. However, in Study Two, with substantially heterogeneous costs ($10,123-$21,467 per patient), optimal allocation demonstrated dramatic improvements, increasing statistical efficiency by 27% and cost efficiency by 35% [28]. These results highlight how the advantage of variance-based allocation strategies increases with the degree of heterogeneity in both outcome variability and resource costs across experimental units.

Simulation studies incorporating variability in both patient availability and outcome variances through Poisson and uniform distributions, respectively, further confirmed the robustness of optimal allocation approaches. With 5,000 simulated realizations, the optimal allocation strategy maintained superior performance across varying underlying parameter distributions, with the efficiency advantage particularly pronounced in scenarios with high cross-center heterogeneity [28].

Quantum Computing Applications

Experimental evaluation of shot allocation strategies in quantum chemistry applications provides additional evidence for the superiority of variance-aware approaches. Implementation of the Variance-Preserved Shot Reduction (VPSR) method on molecular systems including Hâ‚‚ and LiH demonstrated significant improvements in measurement efficiency [6]:

Table: Quantum Shot Allocation Comparative Performance

| Molecular System | Allocation Method | Shots to Convergence | Energy Error | Variance Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ (2-qubit) | Uniform Shot Allocation | 1,280,000 | 2.14 × 10â»Â³ | Reference |

| VPSR Method | 427,000 | 1.98 × 10â»Â³ | 2.24× | |

| LiH (4-qubit) | Uniform Shot Allocation | 3,850,000 | 3.87 × 10â»Â³ | Reference |

| VPSR Method | 1,240,000 | 3.52 × 10â»Â³ | 2.58× |

The VPSR approach achieved approximately 3-fold reduction in shot requirements while maintaining comparable or slightly improved accuracy in energy estimation [6]. This efficiency gain directly translates to reduced computational time and resource utilization in quantum simulations, addressing a critical bottleneck in variational quantum algorithm applications.

Beyond mere shot reduction, variance-based allocation strategies demonstrated improved convergence behavior throughout the optimization process. By dynamically reallocating shots based on current variance estimates, the VPSR method maintained more stable convergence trajectories compared to uniform allocation, particularly in later optimization stages where precise gradient estimation becomes crucial for locating minima [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Implementing optimal allocation strategies requires both conceptual frameworks and practical tools. The following research reagents and solutions represent essential components for designing and executing efficient allocation strategies:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Allocation Optimization

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Variance Estimation Algorithms | Quantify outcome variability across experimental units | Preliminary data analysis, historical data review [28] |

| Cost Assessment Tools | Measure resource requirements per data point | Clinical trial budgeting, quantum shot cost analysis [28] [6] |

| Constrained Optimization Software | Solve allocation problems with budget constraints | Python SciPy, MATLAB Optimization Toolbox, R optim function [27] |

| Stratified Sampling Frameworks | Implement optimal allocation across strata | Clinical trial site selection, survey sampling [28] |

| Variance Preservation Methods | Dynamically adjust allocation while maintaining precision | VPSR for quantum measurements [6] |

| Sensitivity Analysis Tools | Assess robustness to parameter misspecification | Monte Carlo simulation, parameter perturbation analysis [28] |

| Portfolio Optimization Algorithms | Allplicate resources across multiple research projects | Research fund allocation, program prioritization [27] |

| 14-Hydroxy sprengerinin C | 14-Hydroxy Sprengerinin C|Steroidal Saponin|For Research | 14-Hydroxy sprengerinin C is a natural steroidal saponin from Ophiopogon japonicus for anticancer research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 4''-methyloxy-Genistin | 4''-methyloxy-Genistin, MF:C22H22O10, MW:446.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

These methodological tools enable researchers to transition from theoretical allocation principles to practical implementation. The increasing sophistication of optimization libraries and statistical software has dramatically reduced the computational barriers to implementing optimal allocation strategies, making these approaches accessible even for complex, multi-parameter allocation problems.

Visualization of Methodological Frameworks

Optimal Allocation Decision Framework

Optimal Allocation Decision Framework

This decision framework illustrates the methodological workflow for selecting and implementing allocation strategies. The critical branching point occurs at the method selection stage, where the decision between uniform and variance-based approaches depends on the heterogeneity of variances and costs across experimental units. The framework emphasizes the iterative nature of optimal allocation, incorporating monitoring and adjustment phases to respond to changing parameter estimates throughout the research process.

Mathematical Relationship Visualization

Mathematical Relationship Visualization

This diagram illustrates the mathematical relationships underlying optimal allocation strategies. The core optimization problem simultaneously addresses budget constraints and variance minimization objectives, incorporating stratum-specific parameters including size, outcome variance, and measurement costs. The solution to this optimization problem—the optimal allocation scheme—directly influences both statistical efficiency and resource utilization outcomes, demonstrating the dual benefits of variance-based approaches.

The comparative analysis of variance-based allocation versus uniform distribution reveals a consistent pattern across scientific domains: acknowledging and adapting to heterogeneity in variances and costs yields substantial efficiency improvements. The experimental data demonstrate that variance-based allocation strategies can achieve equivalent statistical power with 20-35% fewer resources, or alternatively, provide 25-50% greater precision under equivalent budget constraints [28] [6].

The strategic implications for research optimization are profound. In clinical trial design, adopting optimal allocation approaches can reduce development costs while maintaining statistical integrity, potentially accelerating therapeutic development [28] [29]. In quantum computing, efficient shot allocation enables more complex molecular simulations within practical resource constraints [6]. In research portfolio management, optimal fund allocation directs resources toward projects with the highest potential information value per dollar invested [27].

The implementation barrier for these methods has substantially lowered with advances in computational tools and optimization software. While uniform allocation retains value in genuinely homogeneous environments, most real-world research scenarios exhibit sufficient heterogeneity to justify variance-based approaches. As research budgets face increasing scrutiny and measurement technologies generate more complex cost structures, the adoption of optimal allocation frameworks represents a methodological imperative for maximizing scientific return on investment.

The future evolution of allocation methodologies will likely incorporate adaptive approaches that continuously update allocation parameters based on interim data, machine learning techniques for improved variance forecasting, and multi-objective optimization frameworks that balance statistical efficiency with secondary considerations such as equity in resource distribution or risk mitigation. These advances will further strengthen the case for variance-informed allocation as the standard paradigm for resource optimization in scientific research.