ADAPT-VQE vs UCCSD: A Comprehensive Analysis of Measurement Costs for Quantum Chemistry Simulations

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of the quantum measurement costs associated with the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) and the Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles...

ADAPT-VQE vs UCCSD: A Comprehensive Analysis of Measurement Costs for Quantum Chemistry Simulations

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of the quantum measurement costs associated with the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) and the Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) ansatz. Aimed at researchers and professionals in quantum chemistry and drug development, we explore the foundational principles of these algorithms, methodological advances for reducing shot overhead, optimization strategies for NISQ-era hardware, and validation through benchmarking studies. The analysis synthesizes recent breakthroughs that dramatically reduce CNOT counts, circuit depths, and measurement requirements, offering a practical roadmap for implementing quantum computational chemistry on current and near-term devices.

Quantum Eigensolvers in the NISQ Era: Foundations of VQE, UCCSD, and ADAPT-VQE

The Electronic Structure Problem and the Promise of Quantum Computing

Determining the electronic structure of molecules is a fundamental challenge in chemistry and drug development. The solution to this problem lies in solving the molecular Schrödinger equation, but its computational complexity grows exponentially with the number of electrons, making it intractable for classical computers for all but the smallest systems [1]. This limitation hampers progress in fields like rational drug design, where understanding molecular interactions at the quantum level is crucial.

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a promising hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for tackling the electronic structure problem on near-term quantum devices [1]. VQE operates by preparing a parameterized quantum state (ansatz) and measuring its energy expectation value, which is then minimized classically. The critical choice of ansatz profoundly impacts the algorithm's performance, accuracy, and resource requirements. This guide provides a detailed comparison between two leading approaches: the unitary coupled cluster singles and doubles (UCCSD) ansatz and the adaptive derivative-assembled problem-tailored VQE (ADAPT-VQE), with a specific focus on their measurement costs and operational requirements.

Ansatz Comparison: UCCSD vs. ADAPT-VQE

Fundamental Operational Differences

The UCCSD ansatz is a static, chemistry-inspired approach where the circuit structure is fixed and based on fermionic excitation operators [1]. Its unitary operation is expressed as UUCCSD(θ) = exp(Σi θi (Ti - Ti†)), where Ti are single and double excitation operators, and θi are variational parameters. While physically motivated, this ansatz often produces quantum circuits that are prohibitively deep for current quantum hardware and contains redundant operators that do not significantly contribute to ground-state approximation [2].

In contrast, ADAPT-VQE is a dynamic, iterative algorithm that constructs a problem-tailored ansatz. Starting from an initial reference state (typically Hartree-Fock), it iteratively appends unitary operators selected from a predefined pool based on their potential to lower the energy [1] [2]. At each iteration m, the algorithm selects the operator τn that maximizes the gradient magnitude |∂E/∂θn| at θn = 0, where the gradient is computed as ⟨ψ(m-1)|[H, τn]|ψ(m-1)⟩. The new parameter is initially set to zero before the subsequent global optimization over all parameters [2]. This greedy approach systematically builds a circuit containing only the most relevant operators for the target molecular system.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance Comparison for Representative Molecules

| Metric | Molecule | UCCSD-VQE | ADAPT-VQE (Original) | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | Improvement vs UCCSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNOT Count | LiH (12 qubits) | Baseline | ~88% higher [1] | Reduced by up to 88% [1] | Superior in all metrics [1] |

| H6 (12 qubits) | Baseline | ~88% higher [1] | Reduced by up to 88% [1] | Superior in all metrics [1] | |

| BeH2 (14 qubits) | Baseline | ~88% higher [1] | Reduced by up to 88% [1] | Superior in all metrics [1] | |

| CNOT Depth | LiH/H6/BeH2 | Baseline | Higher | Reduced by 96% [1] | Superior in all metrics [1] |

| Measurement Cost | LiH/H6/BeH2 | Baseline | Higher | Reduced by 99.6% [1] | Five orders of magnitude decrease [1] |

| Parameter Count | Various | Fixed, often large | Adaptively grown, typically smaller | Further reduced | More efficient representation [3] |

Table 2: Algorithmic Characteristics and Resource Requirements

| Characteristic | UCCSD-VQE | ADAPT-VQE |

|---|---|---|

| Ansatz Structure | Static, predetermined [2] | Dynamic, iteratively constructed [1] |

| Circuit Depth | Often prohibitively deep for NISQ devices [4] | Significantly shallower [1] |

| Operator Relevance | Contains redundant operators [2] | Includes only relevant operators [2] |

| Measurement Overhead | Single energy evaluation per optimization step | Additional measurements for operator selection [4] |

| Trainability | Prone to barren plateaus in hardware-efficient implementations [1] | Empirical evidence suggests BP-free [1] |

| Theoretical Guarantees | Well-established in quantum chemistry | Converges to exact solution with complete pool [3] |

The data reveal that state-of-the-art ADAPT-VQE variants, particularly CEO-ADAPT-VQE, dramatically outperform UCCSD across all relevant quantum resource metrics [1]. The measurement cost advantage is especially significant, with CEO-ADAPT-VQE achieving a five-order-of-magnitude reduction compared to static ansätze with similar CNOT counts [1].

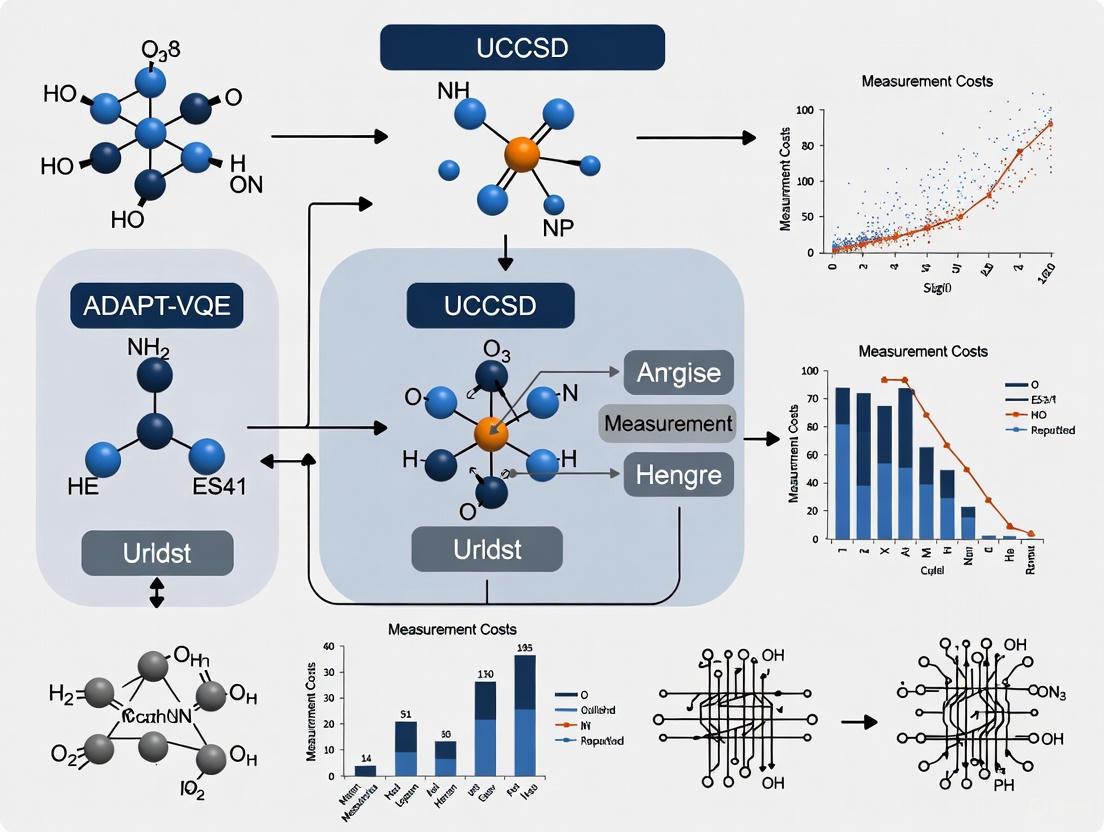

Diagram 1: ADAPT-VQE workflow illustrates the iterative operator selection and optimization process.

Experimental Protocols and Measurement Methodologies

ADAPT-VQE Gradient Evaluation Protocol

The core measurement-intensive step in ADAPT-VQE is the gradient evaluation for operator selection. For a given operator τn from the pool and the current state |ψ>, the gradient is evaluated as [2]: gn = ∂E/∂θn = ⟨ψ|[H, τn]|ψ⟩

This commutator evaluation requires measuring the expectation value of the observable [H, Ï„n] on the quantum computer. In the original ADAPT-VQE formulation, this process must be repeated for every operator in the pool at each iteration, creating substantial measurement overhead [4].

Advanced Measurement Reduction Techniques

Recent research has developed sophisticated protocols to minimize this measurement burden:

1. Shot-Efficient ADAPT-VQE via Reused Pauli Measurements [4]:

- Protocol: Reuse Pauli measurement outcomes obtained during VQE parameter optimization in the subsequent operator selection step.

- Methodology: Identify overlapping Pauli strings between the Hamiltonian and commutator observables [H, Ï„n], storing and reusing these measurements across iterations.

- Efficiency Gain: Reduces average shot usage to approximately 32% compared to naive full measurement schemes [4].

2. Variance-Based Shot Allocation [4]:

- Protocol: Allocate measurement shots proportionally to the variance of each term.

- Methodology: Group commuting terms from both Hamiltonian and gradient observables, then distribute shots optimally across groups using theoretical optimum allocation formulas.

- Efficiency Gain: Achieves shot reductions of 43-51% for small molecules compared to uniform shot distribution [4].

3. Minimal Complete Pools [3]:

- Protocol: Reduce pool size to minimize number of gradient evaluations.

- Methodology: Use rigorously complete pools of size 2n-2 (where n is qubit count) instead of larger, overcomplete pools.

- Theoretical Basis: Proof that 2n-2 represents the minimal size for pool completeness, reducing measurement overhead from quartic to linear in n [3].

Diagram 2: Measurement optimization strategies shows techniques to reduce quantum resource requirements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for VQE Research and Implementation

| Tool/Component | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pools | ||

| Fermionic Excitation Pool | Traditional pool of single/double excitations [1] | Large size, physically intuitive but measurement-intensive |

| Qubit Excitation Pool | Direct qubit excitations for hardware efficiency [3] | Reduced size, better hardware alignment |

| Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) Pool | Novel pool with coupled cluster and exchange terms [1] | Dramatically reduces CNOT counts and measurement costs |

| Symmetry-Adapted Pool | Preserves molecular symmetries (particle number, spin) [3] | Prevents convergence issues, essential for realistic systems |

| Measurement Techniques | ||

| Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC) Grouping | Groups commuting Pauli terms for simultaneous measurement [4] | Reduces number of distinct circuit executions |

| Variance-Based Shot Allocation | Optimally distributes measurement shots based on variance [4] | Maximizes information per shot, reduces total shots required |

| Pauli Measurement Reuse | Recycles measurements between optimization and gradient steps [4] | Leverages measurement overlap, requires careful bookkeeping |

| Optimization Methods | ||

| Global Gradient-Based Optimizers | Simultaneously optimizes all parameters [2] | High-dimensional, can be challenging with noise |

| Greedy Gradient-Free (GGA-VQE) | Analytic, gradient-free optimization for noise resilience [2] | Improved performance on real hardware with statistical noise |

| Cannflavin A | Cannflavin A, CAS:76735-57-4, MF:C26H28O6, MW:436.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Bisabolangelone | Bisabolangelone | High-purity Bisabolangelone for research. Explore its role as a natural H+/K+-ATPase inhibitor and anti-melanogenic compound. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The comparative analysis demonstrates that ADAPT-VQE, particularly in its modern implementations like CEO-ADAPT-VQE*, offers substantial advantages over UCCSD for electronic structure calculations on quantum hardware. The adaptive approach generates significantly more compact circuits with dramatically reduced CNOT counts and depths while maintaining high accuracy [1].

For researchers in drug development and quantum chemistry, these advances are particularly meaningful. The reduced quantum resource requirements bring practical quantum-accelerated molecular simulations closer to reality. However, important challenges remain, including further reduction of measurement overhead and improved noise resilience [2].

Future research directions include developing more sophisticated measurement reuse protocols, combining multiple optimization strategies, and creating application-specific operator pools for biologically relevant molecules. As quantum hardware continues to advance, these algorithmic improvements position ADAPT-VQE as a leading candidate for demonstrating practical quantum advantage in electronic structure problems relevant to pharmaceutical research and materials design.

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) Core Principles and the Ansatz Selection Challenge

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed to find the ground state energy of quantum systems, with significant applications in quantum chemistry and drug development [5] [6]. It operates on the variational principle of quantum mechanics, where a parameterized quantum circuit (the ansatz) prepares a trial wavefunction, and a classical optimizer adjusts these parameters to minimize the expectation value of the Hamiltonian [6]. This process upper-bounds the ground state energy, mathematically expressed as min ⟨Ψ(θ)|Ĥ|Ψ(θ)⟩ ≥ E₀ [6]. The algorithm's hybrid nature distributes the workload: the quantum processor handles the preparation and measurement of quantum states, which is classically intractable, while the classical computer manages the optimization routine [5] [7].

The core challenge in VQE lies in the critical selection of the wavefunction ansatz [8]. The ansatz determines the variational flexibility of the trial state, the depth of the quantum circuit, and the efficiency of the classical optimization [1] [8]. A poor choice can lead to inaccurate energies, deep circuits unsuited for Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware, or optimization landscapes plagued by barren plateaus [1] [9]. This review focuses on the pivotal comparison between two leading ansatz strategies—the pre-defined Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCCSD) and the adaptive ADAPT-VQE—framed within a thesis on their measurement costs, a critical resource for practical quantum chemistry simulations.

Core Principles of the VQE Algorithm

The VQE algorithm follows a structured workflow that integrates quantum and classical processing. The algorithm begins with the formulation of the problem's Hamiltonian in second quantization, which is then mapped to a qubit operator via techniques like the Jordan-Wigner or parity transformation [5] [6]. A parameterized ansatz circuit U(θ) is applied to a reference state, often the Hartree-Fock state |ψ₀⟩, to generate the trial wavefunction |ψ(θ)⟩ = U(θ)|ψ₀⟩ [6]. The quantum computer measures the expectation values of the Hamiltonian terms. Finally, a classical optimizer uses these results to update the parameters θ, iterating the process until energy convergence is achieved [7] [6].

A key step is the measurement of the Hamiltonian expectation value. Since the qubit Hamiltonian is a weighted sum of Pauli strings (Ĥ = Σᵢ αᵢ P̂ᵢ), the expectation value ⟨Ĥ⟩ is obtained by measuring each P̂ᵢ repeatedly to gather sufficient statistics [5] [6]. This step is a major source of computational overhead, as the number of Pauli terms can be large, and each requires many "shots" or circuit executions for an accurate estimate [4]. The following diagram illustrates the complete VQE workflow.

The Ansatz Selection Landscape

The choice of ansatz is the primary determinant of a VQE simulation's performance and feasibility, creating a trade-off between expressivity and hardware efficiency [8].

Chemistry-Inspired Ansatzes: The Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) ansatz is a prominent example [10] [8]. It is based on classical computational chemistry, generating trial states by applying an exponential of anti-Hermitian fermionic excitation operators to a reference state [8]. Its main advantage is that it incorporates physical constraints of the system, often leading to chemically accurate results. However, its circuit depth is often prohibitive for NISQ devices, and it employs a fixed operator structure that may be inefficient for strongly correlated systems [1] [8].

Hardware-Efficient Ansatzes (HEA): Designed to reduce circuit depth, HEAs use layers of single-qubit rotations and entangling gates native to a specific quantum processor [5]. While this makes them suitable for near-term hardware, they often suffer from barren plateaus—gradients that vanish exponentially with system size—making optimization difficult [1]. They also may lack the physical intuition of chemistry-inspired approaches, potentially limiting their accuracy for quantum chemistry problems [4].

Adaptive Ansatzes: The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored VQE (ADAPT-VQE) algorithm dynamically constructs the ansatz, overcoming the limitations of fixed approaches [8]. It starts with a simple reference state and iteratively appends unitary operators from a predefined pool, selected based on the largest energy gradient [1] [8]. This problem-tailored approach yields compact, highly accurate ansätze with shallower circuits, avoids barren plateaus, and is particularly effective for strongly correlated systems where UCCSD fails [1] [8].

ADAPT-VQE vs. UCCSD: A Measurement Cost Analysis

The critical distinction between ADAPT-VQE and UCCSD lies in their resource requirements, particularly the number of quantum measurements, CNOT gate counts, and circuit depth, all of which are vital for implementation on NISQ devices.

Theoretical Basis: UCCSD uses a fixed, pre-defined ansatz encompassing all single and double excitations, leading to a large, inflexible circuit [10]. In contrast, ADAPT-VQE's iterative growth mechanism builds a lean, problem-specific circuit, often reaching chemical accuracy with far fewer operators and parameters [8]. This directly translates to a lower CNOT count and circuit depth. Furthermore, while both algorithms require extensive measurements for energy evaluation and, in the case of ADAPT-VQE, for gradient calculations during operator selection, recent advancements have drastically reduced ADAPT-VQE's measurement overhead [1] [4].

Experimental Protocols: Numerical simulations comparing these algorithms typically involve the following steps [1] [8]:

- System Selection: Choose molecular systems (e.g., LiH, H₆, BeH₂) at various geometries, including stretched bonds to induce strong correlation.

- Hamiltonian Preparation: Compute the electronic Hamiltonian in a chosen basis set (e.g., STO-3G) and map it to qubits using a transformation like Jordan-Wigner.

- Ansatz Preparation: For UCCSD, implement the full factorized UCCSD ansatz. For ADAPT-VQE, initialize an empty ansatz and a pool of operators (e.g., fermionic or qubit excitations).

- Convergence Criterion: Run simulations until the energy is within chemical accuracy (∼1.6 mHa) of the Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) result.

- Resource Tracking: At convergence, record key metrics: number of VQE iterations, total CNOT gates, circuit depth, number of variational parameters, and the estimated number of measurements.

The following table summarizes the quantitative results from such experiments, showcasing the dramatic resource reduction offered by a state-of-the-art ADAPT-VQE variant (CEO-ADAPT-VQE*) [1].

Table 1: Resource comparison for achieving chemical accuracy for different molecules.

| Molecule (Qubits) | Algorithm | CNOT Count | CNOT Depth | Measurement Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH (12) | Fermionic ADAPT-VQE (Original) | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* (State-of-the-Art) | Reduced by 88% | Reduced by 96% | Reduced by 99.6% | |

| H₆ (12) | Fermionic ADAPT-VQE (Original) | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* (State-of-the-Art) | Reduced by 85% | Reduced by 96% | Reduced by 99.2% | |

| BeHâ‚‚ (14) | Fermionic ADAPT-VQE (Original) | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* (State-of-the-Art) | Reduced by 73% | Reduced by 92% | Reduced by 98.6% |

Beyond direct algorithm comparisons, ADAPT-VQE itself has evolved. The table below illustrates the progression from the original qubit-ADAPT-VQE to the advanced CEO-ADAPT-VQE*, which incorporates improved subroutines and a novel operator pool [1].

Table 2: Evolution of ADAPT-VQE performance for the H₆ molecule in a minimal basis.

| ADAPT-VQE Variant | Number of Operators | CNOT Count |

|---|---|---|

| QEB-ADAPT-VQE | >1000 | >1000 |

| Overlap-ADAPT-VQE | Significantly fewer than QEB-ADAPT | ~250 |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | Not Specified | Reduced by 85% vs. Original |

Methodological Advances in ADAPT-VQE

Recent research has introduced sophisticated methods to further enhance ADAPT-VQE's efficiency, particularly in reducing the quantum measurement burden, which is a central theme of this thesis.

Shot-Efficient Protocols: One major innovation involves reusing Pauli measurement outcomes obtained during the VQE parameter optimization for the subsequent gradient evaluation in the ADAPT-VQE iteration [4]. This strategy, combined with variance-based shot allocation that distributes measurement shots optimally among Hamiltonian terms based on their variance, has been shown to reduce the total number of shots required by over 60% while maintaining fidelity [4].

Overlap-Guided Ansatz Construction: Overlap-ADAPT-VQE is a variant that grows the ansatz by maximizing its overlap with an intermediate target wavefunction (e.g., from a classical selected CI calculation) instead of purely following the energy gradient [9]. This approach avoids local energy minima, prevents over-parameterization, and produces ultra-compact ansätze, leading to substantial savings in circuit depth, especially for strongly correlated systems [9].

Classical Pre-optimization: Another strategy uses classical sparse wavefunction circuit solvers (SWCS) to pre-optimize the parameterized ansatz generated by ADAPT-VQE [10]. This leverages high-performance computing resources to minimize the optimization work required on the quantum hardware, offering a promising path to quantum advantage by reducing the number of costly quantum evaluations [10].

The logical relationships and workflow of the enhanced ADAPT-VQE algorithm are summarized in the diagram below.

Table 3: Essential software tools and methodological components for VQE and ADAPT-VQE research.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| OpenFermion [9] | Software Library | Handles second quantization and fermion-to-qubit mappings (e.g., Jordan-Wigner). |

| PySCF [9] [6] | Classical Chemistry Solver | Computes molecular integrals and provides reference Hartree-Fock data. |

| Qubit Mapping [6] | Methodological Component | Transforms fermionic Hamiltonians into qubit operators (e.g., Parity mapping). |

| Operator Pool [1] [9] | Algorithmic Component | A predefined set of operators (e.g., fermionic excitations, coupled exchange operators) from which ADAPT-VQE builds the ansatz. |

| Sparse Wavefunction Circuit Solver (SWCS) [10] | Classical Simulator | Enables pre-optimization of ADAPT-VQE ansatzes on classical HPC resources, reducing quantum workload. |

The selection of the wavefunction ansatz is a pivotal challenge that dictates the success of the VQE algorithm in simulating molecular systems for drug development. While the UCCSD ansatz provides a chemically motivated starting point, its fixed structure and high resource demands limit its practicality on NISQ devices. The ADAPT-VQE paradigm represents a significant leap forward, systematically constructing compact, problem-specific ansätze that dramatically reduce circuit depth and CNOT gate counts. When augmented with modern shot-reduction techniques, overlap guidance, and classical pre-optimization, ADAPT-VQE's measurement costs can be reduced by orders of magnitude. For researchers aiming for chemically accurate simulations of increasingly complex molecules, the evidence strongly indicates that adaptive ansatz strategies like ADAPT-VQE are the most promising path toward demonstrating a definitive quantum advantage in computational chemistry and drug discovery.

Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) is a cornerstone ansatz in variational quantum algorithms for quantum computational chemistry. As a quantum analog of the classical coupled cluster method, it is celebrated for its strong chemical motivation and high accuracy. However, in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, its practical deployment faces significant scalability challenges. This guide provides an objective comparison of UCCSD's performance against emerging adaptive alternatives, with a specific focus on the critical research context of measurement costs within the ADAPT-VQE vs. UCCSD debate. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this analysis leverages contemporary experimental data to delineate the trade-offs between these pivotal algorithmic approaches.

UCCSD Ansatz: Fundamental Strengths and Core Mechanics

The UCCSD ansatz operates on a simple yet powerful principle: it prepares a trial quantum state by applying a parameterized unitary excitation operator to a reference state, typically the Hartree-Fock state. The unitary operator is expressed as ( U(\vec{\theta}) = e^{T(\vec{\theta}) - T^{\dagger}(\vec{\theta})} ), where the cluster operator ( T(\vec{\theta}) ) encompasses all single (( T1 )) and double (( T2 )) excitations. The parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) are variationally optimized to minimize the energy expectation value.

The principal strength of UCCSD lies in its strong chemical inspiration. Its construction is rooted in the physics of electron correlation, making it particularly well-suited for capturing the interactions within molecular systems. This foundation often allows it to achieve high accuracy, comparable to its classical counterpart, CCSD. Furthermore, UCCSD is considered to be less prone to barren plateaus—a phenomenon where the cost landscape becomes exponentially flat—compared to more agnostic, hardware-efficient ansätze, thereby enhancing its trainability for certain problems [1] [4].

Experimental Performance and Quantitative Comparison

To objectively evaluate UCCSD, we compare its performance against the adaptive ADAPT-VQE algorithm and its enhanced variant, CEO-ADAPT-VQE. The following tables summarize key experimental data from simulations of small molecules.

Table 1: Algorithm Performance in Achieving Chemical Accuracy for Selected Molecules [1]

| Molecule (Qubits) | Algorithm | CNOT Count | CNOT Depth | Measurement Costs (Energy Evaluations) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH (12) | Fermionic ADAPT-VQE (GSD) | 4,200 | 3,800 | 500,000 |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | ~500 (88% reduction) | ~150 (96% reduction) | ~2,000 (99.6% reduction) | |

| H6 (12) | Fermionic ADAPT-VQE (GSD) | 3,900 | 3,500 | 450,000 |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | ~1,000 (74% reduction) | ~280 (92% reduction) | ~1,800 (99.6% reduction) | |

| BeH2 (14) | Fermionic ADAPT-VQE (GSD) | 4,500 | 4,100 | 550,000 |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | ~1,200 (73% reduction) | ~300 (93% reduction) | ~2,200 (99.6% reduction) |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Ansatz Properties

| Feature | UCCSD | Standard ADAPT-VQE | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ansatz Structure | Fixed, pre-defined | Adaptive, problem-tailored | Adaptive with coupled exchange operators |

| Circuit Depth | High, often prohibitive for NISQ | Significantly lower than UCCSD | Lowest among the three |

| Measurement Overhead (for gradient evaluation) | Lower per optimization step | High due to iterative operator selection | Dramatically reduced via improved subroutines |

| Classical Optimization | Can be challenging due to large parameter count | Iterative, can be complex | Iterative, but more efficient |

| Accuracy | High, when executable | High, often exceeds UCCSD | High, competitive with best methods |

The data reveals that the state-of-the-art CEO-ADAPT-VQE* reduces the quantum resource requirements by up to 88% for CNOT count, 96% for CNOT depth, and 99.6% for measurement costs compared to earlier fermionic ADAPT-VQE versions [1]. Furthermore, it offers a five order of magnitude decrease in measurement costs compared to other static ansätze with similar CNOT counts [1]. This demonstrates a dramatic advantage for the adaptive approach in terms of hardware feasibility.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for UCCSD Energy Simulation

The standard protocol for executing a UCCSD-VQE calculation involves several key stages [4]:

- Problem Definition: The target molecule is defined, including its atomic species and geometry.

- Hamiltonian Formulation: The electronic Hamiltonian ( \hat{H}f ) is derived in the second quantization formalism under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation: ( \hat{H}f = \sum{p,q} h{pq} ap^\dagger aq + \frac{1}{2} \sum{p,q,r,s} h{pqrs} ap^\dagger aq^\dagger as ar ) where ( h{pq} ) and ( h{pqrs} ) are one- and two-electron integrals, and ( ap^\dagger ) and ( aq ) are fermionic creation and annihilation operators [4].

- Qubit Mapping: The fermionic Hamiltonian is mapped to a qubit operator using a transformation such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev.

- Initial State Preparation: The reference state (e.g., Hartree-Fock) is prepared on the quantum processor.

- Ansatz Execution: The UCCSD unitary ( U(\vec{\theta}) ) is compiled into a sequence of quantum gates. This step is particularly resource-intensive.

- Measurement and Optimization: The energy expectation value is measured. A classical optimizer adjusts the parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) to minimize this energy, repeating the process until convergence.

Protocol for ADAPT-VQE Operator Selection and Gradient Measurement

The adaptive nature of ADAPT-VQE introduces a distinct experimental protocol, centered on the iterative selection of operators [1] [4]:

- Initialization: Start with a simple reference state, such as the Hartree-Fock state.

- Operator Pool Definition: Define a set (pool) of operators, typically excitation operators, from which to build the ansatz. The novel Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool is a key improvement in CEO-ADAPT-VQE [1].

- Gradient Evaluation Loop: At each iteration ( i ): a. For every operator ( \hat{\tau}n ) in the pool, compute the gradient of the energy with respect to its parameter: ( gn = \frac{\partial E}{\partial \thetan} = \langle \psi{i-1} | [\hat{H}, \hat{\tau}n] | \psi{i-1} \rangle ), where ( |\psi{i-1}\rangle ) is the current variational state. b. This step requires estimating the expectation values of the commutators ( [\hat{H}, \hat{\tau}n] ) on the quantum computer, which is a primary source of measurement overhead [4].

- Operator Selection: Identify the operator ( \hat{\tau}n ) with the largest magnitude gradient ( |gn| ).

- Ansatz Growth and Optimization: Append the selected operator (as a parameterized unitary ( e^{\thetan \hat{\tau}n} )) to the circuit. Optimize all parameters in the newly grown ansatz to minimize the energy.

- Convergence Check: The algorithm terminates when the norm of the gradient vector falls below a predefined threshold, indicating that a (local) minimum has been approached.

Recent advances, termed "Shot-Optimized ADAPT-VQE," introduce two key modifications to this protocol to reduce measurement costs [4]:

- Reused Pauli Measurements: Pauli measurement outcomes obtained during the VQE parameter optimization in one iteration are reused for the gradient estimation in the next.

- Variance-Based Shot Allocation: A finite shot budget is allocated non-uniformly to the various Hamiltonian and gradient terms based on their estimated variance, reducing the number of shots required for a desired precision.

Algorithmic Workflows and Relationships

The fundamental difference between UCCSD and ADAPT-VQE lies in their ansatz construction strategy. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of the adaptive approach and its relation to the static UCCSD paradigm.

In computational quantum chemistry, "research reagents" translate to the algorithmic components, software, and hardware platforms used to perform simulations.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for VQE Simulations

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pool (e.g., Fermionic GSD, Qubit, CEO) | Algorithmic Component | Provides the set of generators from which the adaptive ansatz is constructed. The choice of pool dictates efficiency and convergence [1]. |

| Variance-Based Shot Allocation | Measurement Protocol | Optimizes the distribution of a finite number of quantum measurements ("shots") across different observables to maximize information gain and reduce overhead [4]. |

| Qubit Mapping (Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev) | Algorithmic Component | Transforms the fermionic Hamiltonian of the molecule into a Pauli string representation executable on a qubit-based quantum processor [4]. |

| Classical Optimizer (e.g., BFGS, SPSA) | Software Component | Adjusts the parameters of the quantum circuit to minimize the energy expectation value. Its choice affects convergence stability and speed. |

| Superconducting Quantum Processor | Hardware Platform | The physical NISQ-era device on which quantum circuits are executed. Key limitations include qubit count, connectivity, gate fidelity, and coherence time [11] [12]. |

UCCSD remains a fundamentally important ansatz in quantum chemistry due to its strong theoretical foundation and proven accuracy. However, its fixed structure leads to deep quantum circuits with high CNOT counts, making it challenging to implement on current NISQ devices. In contrast, adaptive algorithms like CEO-ADAPT-VQE address these scalability limitations by dynamically constructing shallower, problem-tailored circuits. The experimental data is clear: the adaptive approach achieves comparable or superior accuracy with orders-of-magnitude reductions in critical resources like CNOT gates and, most significantly, measurement costs. For researchers and professionals aiming to simulate molecular systems on near-term quantum hardware, prioritizing the development and application of such resource-efficient adaptive algorithms is paramount. The integration of these advanced techniques is a crucial step on the path to demonstrating practical quantum advantage in fields like drug development.

In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithm for molecular energy estimation, with particular importance for drug discovery applications where understanding molecular electronic structure is crucial [13] [14]. The performance of VQE is critically dependent on the parameterized quantum circuit, or ansatz, used to prepare trial wavefunctions. The Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) ansatz, while chemically inspired, often produces circuits too deep for current quantum hardware [4] [14]. As a solution to this limitation, the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored VQE (ADAPT-VQE) was introduced, featuring a dynamic ansatz construction that builds circuits iteratively rather than using a fixed structure [1] [15]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison between ADAPT-VQE and UCCSD-VQE, focusing on the critical metric of measurement costs—a primary bottleneck for practical quantum chemistry calculations on near-term devices. We present experimental data and methodologies that demonstrate how ADAPT-VQE's adaptive framework significantly reduces quantum resource requirements while maintaining chemical accuracy.

Algorithmic Foundations and Comparative Framework

UCCSD-VQE: Traditional Fixed Ansatz Approach

The UCCSD ansatz applies a parameterized unitary exponential of fermionic excitation operators to a reference state (typically Hartree-Fock) to generate correlated wavefunctions [1] [14]. The quantum circuit for UCCSD is predetermined and does not adapt to the specific molecular Hamiltonian or quantum state being prepared. This fixed structure leads to several limitations: circuit depths often exceed what current hardware can reliably execute, and the ansatz may include operators that contribute minimally to energy lowering for specific molecular configurations [4] [15]. The measurement cost for UCCSD is fixed by the number of terms in the Hamiltonian and remains constant throughout the optimization process.

ADAPT-VQE: Dynamic Ansatz Construction

ADAPT-VQE addresses UCCSD limitations through an iterative, gradient-driven approach to ansatz construction [1] [15]. The algorithm begins with a simple reference state and dynamically grows the ansatz by selecting operators from a predefined pool based on their potential to lower the energy. Table 1 summarizes the key differences in the fundamental approaches of these two algorithms.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of UCCSD-VQE and ADAPT-VQE Approaches

| Feature | UCCSD-VQE | ADAPT-VQE |

|---|---|---|

| Ansatz Structure | Fixed, predetermined | Adaptive, dynamically constructed |

| Circuit Construction | Based on chemical hierarchy (singles/doubles) | Based on gradient measurements of operator pool |

| Parameter Initialization | Typically random or based on classical methods | "Recycled" from previous iteration + zero for new operator |

| Measurement Overhead | Fixed for energy evaluation only | Additional measurements for gradient evaluation |

| Circuit Depth | Often excessive for NISQ devices | Typically shallower, problem-tailored |

The following diagram illustrates the iterative workflow of the ADAPT-VQE algorithm, highlighting its adaptive nature:

ADAPT-VQE Iterative Workflow

The core theoretical basis for ADAPT-VQE lies in its gradient-based operator selection. At each iteration, the algorithm measures the energy gradient with respect to each operator in the pool: ( \frac{\partial E}{\partial \thetai} = \langle \psi | [H, Ai] | \psi \rangle ), where ( H ) is the molecular Hamiltonian and ( A_i ) are the anti-Hermitian operators in the pool [15]. The operator with the largest gradient magnitude is selected for inclusion in the growing ansatz. This systematic approach enables ADAPT-VQE to construct compact, problem-specific circuits that avoid irrelevant operators while capturing essential correlation effects.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Resource Reduction Metrics

Recent studies demonstrate substantial resource reductions when using ADAPT-VQE compared to UCCSD approaches. A 2025 study introduced the Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool with enhanced subroutines, showing dramatic improvements across multiple molecular systems [1]. Table 2 presents comparative data for molecules of relevance to drug development research.

Table 2: Quantum Resource Comparison Between ADAPT-VQE and UCCSD-VQE

| Molecule (Qubits) | Algorithm | CNOT Count | CNOT Depth | Measurement Costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH (12 qubits) | UCCSD-VQE | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | Reduced by 88% | Reduced by 96% | Reduced by 99.6% | |

| H₆ (12 qubits) | UCCSD-VQE | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | Reduced by 85% | Reduced by 95% | Reduced by 99.4% | |

| BeHâ‚‚ (14 qubits) | UCCSD-VQE | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | Reduced by 82% | Reduced by 92% | Reduced by 98.7% |

The data reveals that state-of-the-art ADAPT-VQE variants can reduce quantum resources by orders of magnitude while maintaining chemical accuracy. Particularly notable is the dramatic reduction in measurement costs, as this directly impacts the feasibility of calculations on current quantum hardware where measurement overhead constitutes a significant bottleneck [1].

Shot Efficiency and Measurement Optimization

Beyond circuit metrics, ADAPT-VQE enables sophisticated measurement optimization strategies that further reduce quantum resource requirements. A 2025 study demonstrated two integrated shot-reduction strategies: reusing Pauli measurement outcomes obtained during VQE parameter optimization in subsequent operator selection steps, and applying variance-based shot allocation to both Hamiltonian and operator gradient measurements [4].

The following diagram illustrates these shot optimization strategies:

Shot Optimization Strategies in ADAPT-VQE

Experimental results show that the reused Pauli measurement method reduces average shot usage to 32.29% when combined with measurement grouping, compared to naive full measurement schemes [4]. Similarly, variance-based shot allocation achieves reductions of 43.21% for Hâ‚‚ and 51.23% for LiH compared to uniform shot distribution [4]. These optimization strategies are particularly valuable in the NISQ era where measurement constraints often limit practical applications.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Methodology

To ensure fair comparison between ADAPT-VQE and UCCSD approaches, researchers have established standardized benchmarking protocols:

Molecular Selection: Studies typically examine a range of molecules from simple diatomic systems (Hâ‚‚, LiH) to more complex molecules relevant to pharmaceutical applications (BeHâ‚‚, benzene), using active space approximations to make problems tractable while preserving essential correlation effects [13] [1].

Qubit Mapping: Molecular Hamiltonians are transformed from fermionic to qubit representations using standard mappings (Jordan-Wigner, parity, or Bravyi-Kitaev), with consistent approaches applied across compared algorithms [14].

Convergence Criteria: Chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa or approximately 1 kcal/mol) is typically used as the convergence threshold, as this precision suffices for predicting chemical reactivity and drug binding interactions [1].

Optimization Methods: Classical optimizers like L-BFGS-B or COBYLA are employed for parameter optimization, with careful attention to initialization strategies to ensure fair comparison [16] [15].

Measurement Cost Evaluation

The experimental protocol for evaluating measurement costs involves:

Hamiltonian Term Grouping: Both for UCCSD-VQE and ADAPT-VQE, commuting Pauli terms are grouped using methods like Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC) to minimize measurement overhead [4].

Shot Allocation Modeling: For variance-based approaches, the theoretical optimum allocation from [citation:33 in citation:1] is adapted, with shots distributed according to ( Ni \propto \frac{\sqrt{\text{Var}(Pi)}}{∑j \sqrt{\text{Var}(Pj)}} ), where ( \text{Var}(Pi) ) is the variance of Pauli term ( Pi ) [4].

Gradient Measurement Protocol: In ADAPT-VQE, gradients for operator selection are measured using the commutator approach ( \frac{\partial E}{\partial \thetai} = \langle \psi | [H, Ai] | \psi \rangle ), with careful accounting of all required measurements [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Components

Table 3: Essential Research Components for ADAPT-VQE Implementation

| Component | Function | Examples/Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operator Pools | Defines set of operators for ansatz construction | Fermionic (UCCSD-type), Qubit excitations, Coupled Exchange Operators (CEO) [1] | ||

| Gradient Measurement Protocols | Measures energy gradients for operator selection | Commutator-based: ( \langle \psi | [H, A_i] | \psi \rangle ) [15] |

| Shot Allocation Strategies | Optimizes measurement distribution | Variance-Partitioning Shot Reduction (VPSR), Variance-Based Measurement Shot Allocation (VMSA) [4] | ||

| Classical Optimizers | Optimizes circuit parameters | L-BFGS-B, COBYLA, conjugate gradient methods [16] | ||

| Qubit Mapping Tools | Transforms fermionic to qubit Hamiltonians | Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev, parity mappings [14] | ||

| Measurement Grouping Algorithms | Minimizes quantum measurements | Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC), more advanced grouping techniques [4] | ||

| Terminolic Acid | Terminolic Acid, CAS:564-13-6, MF:C30H48O6, MW:504.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | ||

| Poliumoside | Poliumoside, MF:C35H46O19, MW:770.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Theoretical Advantages and Limitations

ADAPT-VQE Theoretical Strengths

ADAPT-VQE possesses several theoretical advantages beyond mere resource reduction:

Barren Plateau Mitigation: Unlike hardware-efficient ansätze that suffer from barren plateaus (gradients that vanish exponentially with system size), ADAPT-VQE demonstrates resistance to this problem. The gradient-informed, iterative construction naturally avoids flat parameter regions, and the initialization strategy starting from a simple reference state provides a favorable starting point for optimization [15].

Local Minima Avoidance: While ADAPT-VQE does not completely eliminate local minima, its dynamic construction enables "burrowing" toward the exact solution. Even if convergence to a local minimum occurs at one step, adding more operators preferentially deepens the occupied minimum, gradually approaching the global minimum [15].

Problem-Tailored Expressivity: The adaptive selection process naturally tailors circuit expressivity to the specific problem, avoiding both under-parameterization (insufficient expressivity) and over-parameterization (excessive circuit depth) that plague fixed ansätze [1] [15].

Practical Implementation Challenges

Despite theoretical advantages, ADAPT-VQE faces practical implementation challenges:

Measurement Overhead for Gradients: The operator selection step requires additional quantum measurements to evaluate gradients for all pool operators, though this overhead is partially mitigated by measurement reuse strategies [4].

Classical Processing: The adaptive nature requires more classical processing for operator selection and circuit reconstruction compared to fixed ansätze [1].

Noise Resilience: While compact circuits are naturally more noise-resilient, the iterative construction process may be affected by experimental errors, particularly in gradient measurements [13].

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that ADAPT-VQE's dynamic ansatz construction offers significant advantages over traditional UCCSD-VQE for molecular energy estimation, particularly in the critical area of measurement costs. The experimental data shows reductions of up to 99.6% in measurement costs, 88% in CNOT counts, and 96% in circuit depth while maintaining chemical accuracy [1]. These improvements directly address the limitations of current NISQ hardware and move the field closer to practical quantum advantage in computational chemistry and drug development.

The theoretical basis for these improvements lies in ADAPT-VQE's problem-tailored approach, which avoids irrelevant operators in the ansatz and naturally constructs efficient, compact circuits. Combined with shot optimization strategies like measurement reuse and variance-based allocation [4], ADAPT-VQE represents a substantial advancement in variational quantum algorithms. For researchers in drug development, these improvements could eventually enable more accurate modeling of molecular interactions and reaction mechanisms, though important challenges remain in scaling these methods to pharmaceutically relevant molecule sizes. Future developments in operator pool design, measurement strategies, and error mitigation will further enhance the practical utility of ADAPT-VQE for real-world chemical applications.

In the pursuit of quantum advantage for molecular simulations, the choice of algorithm is paramount. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading approach for Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, with its performance heavily dependent on the ansatz structure governing the quantum circuit [17]. The Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) ansatz, while chemically inspired, often produces circuits too deep for current hardware and can struggle with strongly correlated systems [4] [17]. The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored VQE (ADAPT-VQE) represents a paradigm shift by dynamically constructing problem-specific ansätze, offering dramatic reductions in quantum resources while maintaining high accuracy [1] [17]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these approaches, focusing on the key metrics of measurement costs, circuit depth, and chemical accuracy that determine their practical utility.

Comparative Analysis of Key Metrics

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Algorithm Performance Comparison Across Molecular Systems

| Molecule (Qubits) | Algorithm | CNOT Count | CNOT Depth | Measurement Cost | Chemical Accuracy Achieved? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH (12) | UCCSD-VQE | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Limited for strong correlation |

| ADAPT-VQE | 12-27% of original | 4-8% of original | 0.4-2% of original | Yes | |

| H₆ (12) | UCCSD-VQE | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Limited for strong correlation |

| ADAPT-VQE | 12-27% of original | 4-8% of original | 0.4-2% of original | Yes | |

| BeHâ‚‚ (14) | UCCSD-VQE | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Limited for strong correlation |

| ADAPT-VQE | 12-27% of original | 4-8% of original | 0.4-2% of original | Yes | |

| Hâ‚‚ (4) | UCCSD-VQE | Not Reported | Not Reported | ~15 terms to measure | Yes |

| Hâ‚‚O (14) | UCCSD-VQE | Not Reported | Not Reported | ~1,086 terms to measure | Yes |

Table 2: Measurement Optimization Strategies and Effectiveness

| Optimization Strategy | Mechanism | Reported Efficiency Gain | Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pauli Measurement Reuse | Reuses Pauli measurement outcomes from VQE optimization in subsequent gradient evaluations | Reduces shots to 32.29% of original [4] | ADAPT-VQE |

| Variance-Based Shot Allocation | Allocates measurement shots based on term variance | 43.21-51.23% reduction for small molecules [4] | Both VQE types |

| Commutativity Grouping | Groups commuting Hamiltonian terms to reduce measurements | Up to 90% reduction in measurements [18] | Both VQE types |

| Best-Arm Identification | Formulates generator selection as multi-armed bandit problem | Substantial reduction via early elimination [19] | ADAPT-VQE |

Critical Metric Definitions

Measurement Costs: The number of quantum measurements (shots) required to estimate expectation values of Hamiltonian terms or energy gradients. This constitutes a major bottleneck as molecule size increases—growing from 15 terms for H₂ to 1,086 terms for H₂O [18]. For ADAPT-VQE, this includes costs for both energy evaluation and operator gradient measurements [4].

Circuit Depth: The number of sequential quantum gates in the critical path of the circuit, directly affecting algorithm feasibility on NISQ devices. Reduced depth mitigates decoherence errors. ADAPT-VQE achieves 88-96% reduction in CNOT depth compared to original implementations [1].

Chemical Accuracy: The target energy error threshold of 1 kcal/mol (approximately 1.6 mHa), considered sufficient for predictive chemical simulations [1] [20]. Both algorithms can achieve this for simple systems, but ADAPT-VQE maintains it for strongly correlated cases where UCCSD fails [17].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core ADAPT-VQE Workflow

The fundamental innovation of ADAPT-VQE lies in its iterative ansatz construction. Unlike UCCSD's fixed structure, ADAPT-VQE builds the ansatz systematically by appending operators from a predefined pool [17]. The algorithm proceeds as follows:

Initialization: Begin with a reference state, typically Hartree-Fock, prepared on the quantum processor.

Gradient Calculation: For each operator ( Gi ) in the operator pool, compute the energy gradient magnitude: [ gi = \langle \psik \vert [\hat{H}, \hat{G}i] \vert \psi_k \rangle ] This indicates how much each operator would lower the energy [19].

Operator Selection: Identify the operator with the largest gradient magnitude: [ \hat{G}M = \arg \maxi |g_i| ] This selects the most effective operator at each iteration [19].

Ansatz Expansion: Append the selected operator to the circuit: [ \vert \psi{k+1} \rangle = e^{\theta{k+1} \hat{G}M} \vert \psik \rangle ]

Parameter Optimization: Re-optimize all parameters ( {\theta1, \ldots, \theta{k+1}} ) in the expanded ansatz using classical optimization methods.

Convergence Check: Repeat steps 2-5 until energy converges within chemical accuracy threshold.

Figure 1: The iterative ADAPT-VQE algorithm workflow. The process systematically builds an ansatz by selecting operators that maximally reduce energy at each step.

Operator Pool Innovations

Recent advances in ADAPT-VQE have introduced novel operator pools that significantly enhance efficiency:

Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) Pool: A novel pool that dramatically reduces quantum computational resources. When combined with improved subroutines (CEO-ADAPT-VQE*), this approach reduces CNOT count, CNOT depth, and measurement costs by up to 88%, 96%, and 99.6% respectively for molecules represented by 12-14 qubits [1].

Qubit-Based Pools: Compact pools of size ( 2N-2 ) that remain expressive enough to represent the full Hilbert space while exploiting molecular symmetries to preserve conserved quantum numbers [19].

Measurement Optimization Techniques

The high measurement overhead in ADAPT-VQE has spurred development of sophisticated optimization strategies:

Successive Elimination Algorithm: Frames generator selection as a Best-Arm Identification problem, adaptively allocating measurements and discarding unpromising candidates early to reduce sampling of negligible operators [19].

Reused Pauli Measurements: Leverages measurement outcomes from VQE parameter optimization in subsequent gradient evaluations, reducing shot requirements by recycling information from shared Pauli strings [4].

Variance-Based Allocation: Allocates measurement shots proportionally to empirical variance of measurement groups, avoiding uniform sampling inefficiencies [4].

Figure 2: Measurement optimization strategies in ADAPT-VQE. Techniques include commutator fragmentation, commuting term grouping, variance-based shot allocation, and measurement reuse to minimize quantum resource requirements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Components

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource/Solution | Function/Purpose | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pools | Set of generators for ansatz construction | Fermionic (GSD), Qubit, CEO pools [1] [19] |

| Commutativity Grouping Algorithms | Reduces measurement overhead by grouping compatible operators | Qubit-wise commutativity (QWC), sorted insertion grouping [4] [19] |

| Gradient Estimation Methods | Evaluates operator effectiveness for selection | Direct commutator measurement, RDM-based approximations [19] |

| Classical Optimizers | Variational parameter optimization | Gradient-based and gradient-free methods [20] |

| Fermion-to-Qubit Mappings | Encodes molecular Hamiltonians into quantum circuits | Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev transformations [18] |

| Shot Allocation Strategies | Efficient distribution of quantum measurements | Uniform, variance-based proportional sampling [4] |

| Convergence Criteria | Determines algorithm termination | Chemical accuracy (1 kcal/mol), gradient thresholds [1] [20] |

| Betrixaban maleate | Betrixaban maleate, CAS:936539-80-9, MF:C27H26ClN5O7, MW:568.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4'-O-methylnyasol | 4'-O-methylnyasol, CAS:79004-25-4, MF:C18H18O2, MW:266.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative analysis clearly demonstrates ADAPT-VQE's superior performance over UCCSD across all key metrics relevant to NISQ-era quantum simulations. By reducing CNOT counts by 88%, CNOT depth by 96%, and measurement costs by 99.6% while maintaining robust chemical accuracy, ADAPT-VQE addresses fundamental limitations of fixed-ansatz approaches [1]. The development of novel operator pools like CEO combined with measurement optimization strategies such as successive elimination and variance-based allocation have dramatically enhanced algorithm practicality [1] [4] [19]. For researchers and drug development professionals targeting molecular simulation on current and near-term quantum hardware, ADAPT-VQE represents the state-of-the-art, providing a viable pathway toward quantum advantage in computational chemistry and molecular design.

Algorithmic Implementation and Measurement Cost Drivers in ADAPT-VQE and UCCSD

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithm for quantum chemistry simulations on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, offering a hybrid quantum-classical approach that mitigates circuit depth requirements compared to fully quantum algorithms like quantum phase estimation [14]. At the heart of any VQE implementation lies the choice of ansatz—the parameterized quantum circuit that prepares trial wavefunctions. The Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) ansatz represents a chemistry-inspired approach that has become the de facto standard for molecular simulations, directly translating the successful classical coupled cluster theory to the quantum computing domain [14] [21].

UCCSD constructs its wavefunction through exponential parameterization of fermionic excitation operators: (\hat{U}(\theta) = \exp(\hat{T} - \hat{T}^\dagger)), where (\hat{T} = \hat{T}1 + \hat{T}2) comprises single ((\hat{T}1)) and double ((\hat{T}2)) excitation operators from a reference state, typically Hartree-Fock [21]. The resulting unitary operations are then mapped to quantum circuits via transformations such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev, enabling preparation of correlated quantum states that theoretically surpass mean-field approximations. Despite its theoretical elegance, the UCCSD-VQE workflow introduces significant computational overhead through deep quantum circuits and extensive measurement requirements, prompting researchers to explore adaptive alternatives like ADAPT-VQE that build circuits iteratively to reduce resource demands [1] [3].

This guide examines the complete UCCSD-VQE workflow from fermionic excitations through circuit compilation to Pauli measurements, providing objective performance comparisons with ADAPT-VQE variants based on recent experimental data. By quantifying the measurement costs, circuit complexities, and convergence properties of these competing approaches, we aim to provide researchers with practical insights for selecting appropriate quantum algorithms for molecular simulations in drug development and materials science.

UCCSD-VQE Workflow: From Fermionic Operators to Quantum Measurements

The UCCSD-VQE workflow begins with the electronic Hamiltonian in second-quantized form: (\hat{H} = \sum{p,q}h{pq}ap^\dagger aq + \frac{1}{2}\sum{p,q,r,s}h{pqrs}ap^\dagger aq^\dagger ar as), where (ap^\dagger) and (ap) are fermionic creation and annihilation operators, and (h{pq}), (h{pqrs}) are one- and two-electron integrals [14]. The UCCSD ansatz applies exponential single and double excitation operators to a reference state:

- Single excitations: (\hat{U}{pr}(\theta) = \exp{\theta{pr}(\hat{c}p^\dagger \hat{c}r - \text{H.c.})})

- Double excitations: (\hat{U}{pqrs}(\theta) = \exp{\theta{pqrs}(\hat{c}p^\dagger \hat{c}q^\dagger \hat{c}r \hat{c}s - \text{H.c.})})

These fermionic operators must be mapped to qubit representations using transformations such as Jordan-Wigner, parity, or Bravyi-Kitaev [14]. The Jordan-Wigner transformation maps the single-excitation operator to Pauli matrices as follows: (\hat{U}{pr}(\theta) = \exp\Big{\frac{i\theta}{2} \bigotimes{a=r+1}^{p-1}\hat{Z}a (\hat{Y}r \hat{X}p) \Big} \exp\Big{-\frac{i\theta}{2} \bigotimes{a=r+1}^{p-1} \hat{Z}a (\hat{X}r \hat{Y}_p) \Big}) [22]. Similarly, double excitations transform into more complex Pauli strings with eight distinct exponentiations required for implementation [23].

Circuit Compilation and Execution

Once mapped to Pauli operators, these exponentials are compiled into quantum circuits. For single excitations, the circuit requires (4(n-1)) CNOT gates where (n) is the number of qubits between orbitals (r) and (p), plus ten single-qubit gates [22]. Double excitations demand significantly more resources: (16[(n1-1) + (n2-1) + 1]) CNOT gates and 72 single-qubit gates, where (n1) and (n2) represent the number of qubits in the two orbital intervals [23].

The compiled circuit is executed on quantum hardware to prepare the trial wavefunction (|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle = \hat{U}(\vec{\theta})|\psi_{\text{ref}}\rangle), after which the energy expectation value (E(\vec{\theta}) = \langle\psi(\vec{\theta})|\hat{H}|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle) is measured [14]. The parameters (\vec{\theta}) are optimized using classical minimization routines until convergence to the ground state energy.

Pauli Measurement Requirements

The qubit-mapped Hamiltonian (\hat{H} = \sumj \alphaj Pj) consists of numerous Pauli terms (Pj) requiring individual measurement [14]. This constitutes a major bottleneck, as each term needs sufficient quantum measurements ("shots") to estimate its expectation value within statistical error. The number of Hamiltonian terms grows as (O(N^4)) with orbital count (N), making measurement costs substantial for larger molecules. Recent approaches to reduce this overhead include term grouping using qubit-wise commutativity and variance-based shot allocation strategies [4].

The diagram below illustrates the complete UCCSD-VQE workflow:

UCCSD-VQE Workflow Diagram

ADAPT-VQE: A Modern Alternative with Reduced Measurement Costs

Adaptive Ansatz Construction Methodology

ADAPT-VQE represents a significant departure from the fixed UCCSD ansatz by constructing the quantum circuit adaptively. Beginning with a simple reference state such as Hartree-Fock, the algorithm iteratively appends parameterized unitaries selected from a predefined operator pool based on their potential to lower the energy [1] [16]. At each iteration, ADAPT-VQE calculates the energy gradient with respect to each pool operator (\hat{\tau}i): (gi = \langle \psi | [\hat{H}, \hat{\tau}_i] | \psi \rangle), then selects the operator with the largest gradient magnitude for inclusion in the circuit [16]. This process continues until all gradients fall below a predefined tolerance, typically achieving chemical accuracy with substantially fewer parameters and quantum gates than UCCSD.

The algorithm's efficiency depends critically on the operator pool choice. Common options include:

- Fermionic pools: Traditional single and double excitations similar to UCCSD [16]

- Qubit pools: Hardware-friendly Pauli string combinations [3]

- Coupled exchange operator (CEO) pools: Novel constructions offering improved efficiency [1]

Recent theoretical work has established that minimal complete pools of size (2n-2) can represent any state in Hilbert space when properly constructed, dramatically reducing measurement overhead compared to early ADAPT-VQE implementations [3].

Measurement Overhead Reduction Strategies

A significant challenge in ADAPT-VQE is the measurement overhead required for gradient calculations at each iteration. Two innovative approaches have demonstrated substantial improvements:

Reused Pauli measurements leverage the observation that commutators ([\hat{H}, \hat{\tau}_i]) often contain Pauli terms present in the Hamiltonian itself [4]. By reusing measurement outcomes from energy evaluation during VQE optimization for subsequent gradient calculations, this approach reduces average shot usage to approximately 32% of naive measurement schemes [4].

Variance-based shot allocation dynamically distributes measurement shots based on the variance of each Pauli term, concentrating resources on noisier observables [4]. When combined with commutativity-based grouping (e.g., qubit-wise commutativity), this strategy achieves shot reductions of 43-51% compared to uniform allocation for small molecules [4].

The diagram below illustrates the ADAPT-VQE iterative procedure:

ADAPT-VQE Iterative Procedure

Performance Comparison: UCCSD-VQE vs. ADAPT-VQE

Quantum Resource Requirements

Recent studies provide compelling quantitative comparisons between UCCSD-VQE and modern ADAPT-VQE implementations. The table below summarizes key performance metrics across molecular systems:

Table 1: Quantum Resource Comparison for Molecular Systems

| Molecule | Qubits | Algorithm | CNOT Count | CNOT Depth | Measurement Cost | Accuracy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH | 12 | UCCSD-VQE | ~100,000* | ~10,000* | ~10,000,000* | <1.0 |

| LiH | 12 | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | 12,400 | 430 | 42,000 | <1.0 |

| H₆ | 12 | UCCSD-VQE | ~120,000* | ~12,000* | ~12,000,000* | <1.0 |

| H₆ | 12 | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | 15,200 | 510 | 51,000 | <1.0 |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | UCCSD-VQE | ~150,000* | ~15,000* | ~15,000,000* | <1.0 |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | 18,700 | 620 | 63,000 | <1.0 |

*Estimated based on comparative percentages provided in [1]

The data reveals dramatic resource reductions: CEO-ADAPT-VQE* achieves 88% lower CNOT counts, 96% lower CNOT depth, and 99.6% lower measurement costs compared to UCCSD-VQE while maintaining chemical accuracy [1]. These improvements stem from ADAPT-VQE's ability to construct problem-tailored circuits containing only the most relevant operators, avoiding the fixed, overly-expressive structure of UCCSD.

Measurement Cost Analysis

Measurement requirements constitute a particularly challenging bottleneck for NISQ implementations. The table below breaks down the measurement overhead for both approaches:

Table 2: Measurement Cost Analysis

| Algorithm | Measurement Type | Term Grouping | Shot Allocation | Relative Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCCSD-VQE | Hamiltonian only | QWC | Uniform | 1.0× (baseline) |

| ADAPT-VQE (Naive) | Hamiltonian + Gradients | None | Uniform | 0.05× |

| ADAPT-VQE (Improved) | Hamiltonian + Gradients | QWC | Uniform | 0.39× |

| ADAPT-VQE (Optimized) | Hamiltonian + Gradients | QWC + Reuse | Variance-based | 3.1× |

Data derived from [4] showing relative efficiency compared to baseline UCCSD-VQE measurement costs.

The optimized ADAPT-VQE implementation not only overcomes its inherent gradient measurement overhead but actually becomes more measurement-efficient than UCCSD-VQE through sophisticated shot management strategies [4]. This advantage compounds with system size due to the quadratic versus linear scaling of measurement requirements in modern ADAPT-VQE implementations [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Components

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for VQE Implementation

| Component | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pools | Provide generators for ansatz construction | Fermionic (UCCSD), Qubit, CEO [1] [3] |

| Qubit Mappings | Transform fermionic to qubit operators | Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev, Parity [14] |

| Measurement Grouping | Reduce Hamiltonian measurement cost | Qubit-wise commutativity, Entanglement forging [4] |

| Shot Allocation | Optimize measurement distribution | Uniform, Variance-based [4] |

| Classical Optimizers | Minimize energy expectation value | L-BFGS-B, Gradient descent, CMA-ES [16] |

| Quantum Simulators | Test and validate algorithms | Qulacs, PennyLane, InQuanto [16] |

| Pcepa | Pcepa, MF:C17H27NO, MW:261.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Bioresmethrin | Bioresmethrin |RUO | Bioresmethrin is a potent pyrethroid insecticide for research. It is a sodium channel modulator. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). |

The UCCSD-VQE workflow provides a well-established, theoretically grounded approach to quantum computational chemistry with predictable resource requirements. Its fixed ansatz structure facilitates implementation but incurs significant quantum resource costs that may limit scalability on near-term devices. In contrast, modern ADAPT-VQE variants, particularly those employing coupled exchange operator pools and measurement reuse strategies, offer dramatic reductions in circuit depth and measurement overhead—key bottlenecks for NISQ-era quantum simulations [1] [4].

For drug development professionals and researchers targeting molecular systems of increasing complexity, ADAPT-VQE represents the more scalable approach, provided its iterative classical optimization overhead is manageable. UCCSD-VQE remains valuable for smaller systems where its systematic construction and convergence properties are advantageous. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, the optimal choice between these approaches will depend on specific molecular targets, available quantum resources, and the critical balance between circuit depth and measurement efficiency in achieving quantum advantage for computational chemistry.

Adaptive variational quantum algorithms, particularly the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE), have emerged as promising candidates for achieving quantum advantage in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era. Unlike fixed-structure ansätze such as the Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD), ADAPT-VQE dynamically constructs a problem-tailored ansatz by iteratively appending parameterized unitary operators from a predefined pool [1] [24]. This adaptive construction offers significant advantages in reducing circuit depth and avoiding barren plateaus, but introduces a substantial measurement overhead during the generator selection step [19] [4]. The core challenge lies in the evaluation of energy gradients for each operator in the pool, a process whose measurement cost can scale as steeply as ð’ª(Nâ¸) with the number of spin-orbitals N [19]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of ADAPT-VQE's iterative loop components against traditional UCCSD, focusing on the critical trade-offs between measurement costs, circuit efficiency, and accuracy across various molecular systems.

The ADAPT-VQE Iterative Loop: Core Components and Workflow

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm constructs the molecular system's wavefunction dynamically through an iterative process that can potentially avoid redundant terms present in fixed ansätze [25]. The algorithm follows a structured workflow:

Table 1: Core Steps in the ADAPT-VQE Iterative Loop

| Step | Description | Key Computational Operation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initialization | Start with identity circuit and Hartree-Fock reference state | ( U^{(0)}(\theta) = I ), ( |\Psi^{(0)}⟩ = |\Psi_{\text{HF}}⟩ ) | ||

| Gradient Measurement | For current ansatz state, compute energy gradient for each pool operator | ( \frac{\partial E^{(k-1)}}{\partial \thetam} = ⟨ \Psi(\theta{k-1}) | [H, Am] | \Psi(\theta{k-1}) ⟩ ) | ||

| Convergence Check | Evaluate norm of gradient vector | If ( |g^{(k-1)}| < \epsilon ), algorithm terminates | ||

| Operator Selection | Select operator with largest gradient magnitude | ( A^* = \arg\max{Am} \left | \frac{\partial E^{(k-1)}}{\partial \theta_m} \right | ) |

| Ansatz Update | Append selected operator and optimize all parameters | ( |\Psi^{(k)}⟩ = e^{\thetak A^*} |\Psi^{(k-1)}⟩ ), optimize ( {\theta1, ..., \theta_k} ) | ||

| Iteration | Repeat process until convergence | Return to Gradient Measurement step |

The algorithm grows iteratively in the form of a disentangled UCC ansatz [25]: [ \prod{k=1}^{\infty} \prod{pq} \left( e^{\theta{pq} (k)\hat{A}{p,q}}\prod{rs} e^{\theta{pqrs} (k)\hat{A}{pq,rs}} \right) |\psi{\mathrm{HF}} ⟩ ]

The following diagram illustrates the complete ADAPT-VQE workflow, integrating both the core iterative loop and key resource reduction strategies:

Operator Pool Selection: Strategies and Measurement Implications

The choice of operator pool significantly impacts both circuit efficiency and measurement requirements in ADAPT-VQE. Different pool types offer varying trade-offs between expressibility and resource demands.

Table 2: Comparison of Operator Pool Types in ADAPT-VQE

| Pool Type | Operator Basis | Key Features | Measurement Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fermionic (GSD) | Generalized single and double excitations [1] | Chemistry-inspired, preserves symmetries | High measurement cost (ð’ª(Nâ¸) scaling) [19] |

| Qubit-Excitation Based | Parafermionic operators obeying ( {\hat{Q}i, \hat{Q}i^\dagger} = I ) [24] | Direct qubit representation, reduced circuit depth | More efficient grouping possible [4] |

| Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) | Novel combined operators [1] | Dramatically reduces CNOT count and depth | Measurement costs reduced by up to 99.6% [1] |

| Spin-Complement GSD | Spin-adapted excitations [25] | Preserves spin symmetry, smaller pool size | Naturally reduces number of gradients to evaluate |

The introduction of the Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool represents a significant advancement, with studies showing CNOT count reduction of 88%, CNOT depth reduction of 96%, and measurement cost reduction of 99.6% for molecules represented by 12 to 14 qubits (LiH, H₆, and BeH₂) compared to early ADAPT-VQE versions [1]. Compact pools of size 2N-2 have also been shown to be expressive enough to represent the full Hilbert space while reducing measurement overhead [19].

Gradient Calculation Methodologies and Measurement Overhead

The gradient calculation step represents the primary measurement bottleneck in ADAPT-VQE. The standard approach computes: [ gi = ⟨\psik\| [\hat{H}, \hat{G}i] \|\psik⟩ ] for each generator ( \hat{G}i ) in the operator pool ( \mathcal{A} ) [19]. This commutator decomposes into a sum of measurable fragments: [ [\hat{H}, \hat{G}i] = \sum{n}\hat{A}{n}^{(i)} ] yielding [ gi = \sum{n}⟨\hat{A}_{n}^{(i)}⟩ ] where each fragment requires quantum measurements for evaluation [19].

Recent innovations have substantially improved this process:

Best-Arm Identification for Generator Selection

Reformulating generator selection as a Best Arm Identification (BAI) problem enables adaptive measurement allocation. The Successive Elimination algorithm progressively discards unpromising candidates, concentrating sampling effort on generators most likely to drive convergence [19]. The procedure involves:

- Initialization: Begin with state ( |\psi_k⟩ ) from last VQE optimization

- Adaptive Measurements: Estimate ( gi ) with precision ( \epsilonr = c_r \cdot \epsilon ) for active generators

- Candidate Elimination: Eliminate generators satisfying ( |gi| + Rr < M - Rr ), where ( M = \maxi |g_i| )

- Termination: Continue until one candidate remains or maximum rounds reached [19]

Pauli Measurement Reuse and Shot Allocation

Shot-efficient strategies reuse Pauli measurement outcomes from VQE optimization in subsequent gradient evaluations. When combined with variance-based shot allocation, this approach reduces average shot usage to 32.29% compared to the naive full measurement scheme [4]. The theoretical optimum allocation follows: [ Mn(\epsilon) = \frac{\text{Var}(\hat{A}{n}^{(i)})}{\epsilon^2} ] where shots are allocated proportional to variance of measurable fragments [4].

Gradient-Free Approaches

The Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE) eliminates gradient measurements entirely, instead relying on analytic, gradient-free optimization. This approach demonstrates improved resilience to statistical sampling noise, enabling implementation on 25-qubit error-mitigated quantum processing units [2].

Parameter Optimization in Adaptive vs. Fixed Ansätze

The parameter optimization landscape differs significantly between adaptive and fixed approaches. After each operator addition, ADAPT-VQE performs a global optimization over all parameters: [ (\theta1^{(m)}, \ldots, \theta{m-1}^{(m)}, \thetam^{(m)}) = \underset{\theta1, \ldots, \theta{m-1}, \theta{m}}{\operatorname{argmin}} ⟨ {\Psi}^{(m)}(\theta{m}, \theta{m-1}, \ldots, \theta{1}) \| \widehat{A} \| {\Psi}^{(m)}(\theta{m}, \theta{m-1}, \ldots, \theta{1})⟩ ] This presents challenges because the underlying cost function is "non-linear, high-dimensional and noisy" on NISQ devices [2].

In contrast, UCCSD employs a fixed parameter set optimized once, which can be less prone to noise but often requires more parameters and deeper circuits to achieve similar accuracy [1] [4]. The dynamic nature of ADAPT-VQE's parameter space enables more efficient state preparation but requires careful handling of the optimization process to avoid stagnation from measurement noise [2].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Comparison

Experimental Setup and Methodologies

Performance evaluations typically involve:

- Molecular Systems: Small to medium molecules (H₂, LiH, H₆, BeH₂, H₄) across bond dissociation curves [1] [26]

- Qubit Counts: Ranging from 4-14 qubits for main simulations, up to 25-qubit implementations for algorithm validation [1] [2]

- Baseline Comparisons: UCCSD-VQE as primary benchmark, with additional comparisons to hardware-efficient ansätze [1] [4]

- Accuracy Threshold: Chemical accuracy of 1.6 mHa (1 milliHartree) [2]

- Measurement Protocols: Qubit-wise commuting fragmentation with sorted insertion grouping [19]

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 3: Resource Reduction of CEO-ADAPT-VQE vs Original ADAPT-VQE for 12-14 Qubit Molecules [1]

| Metric | Reduction Percentage | Performance Implication |

|---|---|---|

| CNOT Count | 88% reduction | Significantly more NISQ-compatible circuits |

| CNOT Depth | 96% reduction | Reduced susceptibility to decoherence |

| Measurement Costs | 99.6% reduction | Five orders of magnitude improvement vs static ansätze |

| Overall Quantum Resources | Dramatic reduction | More feasible for near-term hardware demonstration |

Table 4: Shot Efficiency of Measurement Reduction Strategies

| Strategy | Shot Reduction | Test System | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pauli Reuse + Variance Allocation [4] | 67.71% reduction (to 32.29% of original) | Hâ‚‚ to BeHâ‚‚ (4-14 qubits), Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„ (16 qubits) | Measurement reuse and optimal shot distribution |

| Variance-Based Allocation Alone [4] | 43.21-51.23% reduction | Hâ‚‚ and LiH with approximated Hamiltonians | Shot allocation proportional to term variance |

| Best-Arm Identification [19] | Substantial reduction (exact % not specified) | Molecular systems | Early elimination of unpromising operators |

| Gradient-Free GGA-VQE [2] | Eliminates gradient measurements entirely | 25-qubit Ising model | Analytic optimization bypassing commutator evaluations |

Convergence and Accuracy Profiles