Advanced Ansatz Optimization Strategies for Variational Quantum Algorithms in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to ansatz optimization strategies for Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs), tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Advanced Ansatz Optimization Strategies for Variational Quantum Algorithms in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to ansatz optimization strategies for Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs), tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, including the critical challenge of barren plateaus and the role of ansatz circuits in algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE). The content explores methodological advances such as depth-optimized and sequentially generated ansatzes, alongside practical applications in molecular simulation and formulation design. The article also details troubleshooting strategies for noisy quantum hardware and complex optimization landscapes, and concludes with validation methodologies and comparative analyses of classical optimizers, synthesizing key takeaways for near-term quantum applications in biomedical research.

Understanding Ansatz Circuits and Core Challenges in Variational Quantum Algorithms

The Role of Parameterized Quantum Circuits in VQAs and the VQE

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my VQE optimization converge to an incorrect energy value or become unstable when using a large number of shots? This is often caused by sampling noise in the cost function landscape [1]. Finite sampling introduces statistical fluctuations that can obscure true energy gradients and create false local minima, disrupting the optimizer [1]. The precision of your energy measurement is limited by the number of shots; there are diminishing returns on accuracy beyond approximately 1000 shots per measurement [1].

Q2: Which classical optimizer should I choose for my VQE experiment to ensure convergence, especially on real hardware? Optimizer choice depends on noise conditions [1]. The table below summarizes optimizer performance:

| Optimizer Class | Example Algorithms | Performance under ideal (noiseless) conditions | Performance under sampling noise conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-based | BFGS, Gradient Descent (GD) | Best performance [1] | Performance degraded [1] |

| Stochastic | SPSA | --- | Good sampling efficiency, resilient to noise [1] [2] |

| Population-based | CMA-ES, PSO | --- | Greater resilience to noise [1] |

| Derivative-free | COBYLA, Nelder-Mead | --- | Performance varies [1] |

Q3: How does the choice of parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) impact my results? The ansatz is critical for VQA performance [3]. Inappropriate ansatz choices can lead to issues like the barren plateau phenomenon (vanishing gradients) or an inability to represent the true ground state [1] [3]. For quantum chemistry problems, physically-inspired ansätze like the Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz (VHA) can preserve molecular symmetries and reduce parameter counts compared to more general architectures like the Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) [1].

Q4: I am getting a qubit index error when using measurement error mitigation with VQE. How can I resolve it? This error occurs when the circuits executed for error mitigation do not use the same set of qubits as the main VQE circuit [4]. Ensure all circuits in your VQE job are configured to use an identical set of qubits. This is a known limitation in some runtime environments [4].

Q5: What is the benefit of using Hartree-Fock initialization for my VQE parameters? Initializing your VQE parameters based on the Hartree-Fock state, a classically precomputed starting point, is a highly effective strategy [1]. This can reduce the number of function evaluations required by 27–60% and consistently yields higher final accuracy compared to random initialization [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Convergence Due to Sampling Noise

- Symptoms: The optimization trajectory is erratic, the final energy is inaccurate, or the optimizer fails to converge.

- Root Cause: Finite sampling (

shots) on quantum hardware introduces a "noise floor" that limits the precision of the energy expectation valueE(θ) = ⟨ψ(θ)| H |ψ(θ)⟩[1]. - Solutions:

- Increase Shot Count: Systematically increase the number of shots until the energy estimate stabilizes. Note that beyond ~1000 shots, the improvements diminish [1].

- Use Resilient Optimizers: Switch to noise-resilient optimizers like CMA-ES or SPSA [1].

- Employ Error Mitigation: Apply Measurement Error Mitigation to reduce bias in readout. Be aware this increases the variance of estimates and requires careful circuit configuration [2] [4].

Problem 2: Inefficient Ansatz Optimization

- Symptoms: The circuit requires an excessive number of parameters, the optimization is slow, or it gets trapped in a poor local minimum.

- Root Cause: The ansatz architecture is not well-suited to the problem, or the parameter space is poorly explored.

- Solutions:

- Use Problem-Informed Ansätze: For quantum chemistry, adopt the truncated VHA (tVHA), which is designed to preserve symmetries and reduce the parameter count [1].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: For algorithms like VQD, carefully tune hyperparameters (e.g., overlap coefficients) to significantly improve the accuracy of higher-energy state calculations [3].

- Advanced Strategy: Ansatz Topology Search: For combinatorial problems, you can use an adaptive strategy where the ansatz itself is optimized. One research approach uses Simulated Annealing (SA) to mutate a "genome" that defines the circuit's rotation and entanglement blocks, seeking topologies that maximize the probability of sampling the correct solution [5].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Classical Optimizers for VQE

This protocol helps you systematically select the best optimizer for your specific VQE problem and hardware conditions [1].

- Problem Setup: Select a molecular system (e.g., Hâ‚‚) and prepare its qubit Hamiltonian.

- Ansatz Selection: Choose a fixed parameterized quantum circuit (e.g., tVHA or

TwoLocal). - Initialization: Initialize parameters using the Hartree-Fock state [1].

- Optimizer Comparison: Run the VQE minimization with a fixed shot count (e.g., 1000 shots) and a maximum iteration limit for each optimizer in your test set (e.g., BFGS, SPSA, COBYLA, CMA-ES).

- Performance Metrics: Record the convergence trajectory (energy vs. iteration) and the total number of function evaluations required.

- Noise Introduction: Repeat the benchmarking under simulated sampling noise to identify the most robust optimizer.

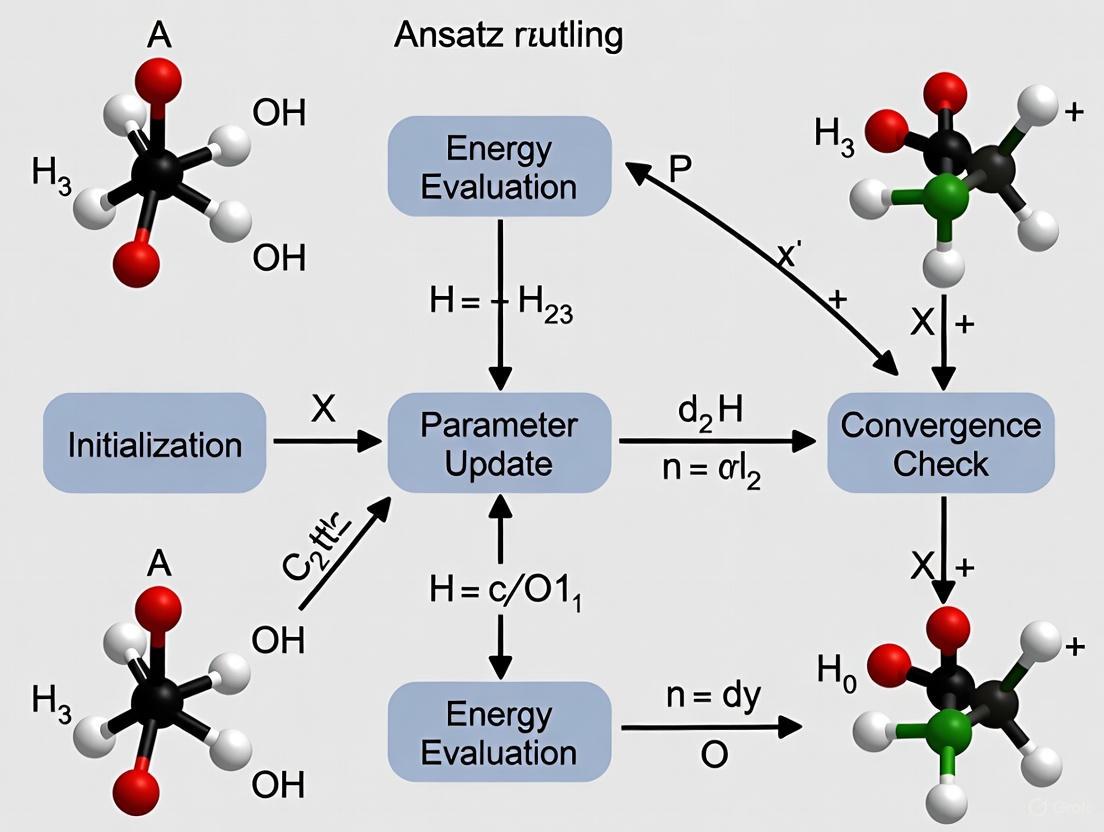

The diagram below illustrates the benchmarking workflow.

Protocol 2: Mitigating Sampling Noise with Robust Estimation

This protocol outlines steps to manage the impact of sampling noise on your VQE results [1] [2].

- Noise Floor Characterization: Run multiple energy estimations at the same parameter set

θwith your target shot count. The standard deviation of these results characterizes the noise floor. - Shot Count Sweep: Perform a short VQE run at different shot counts (e.g., 100, 500, 1000, 5000). Plot the final energy accuracy against the shot count to identify the point of diminishing returns.

- Error Mitigation Integration: Apply a measurement error mitigation technique (e.g., built-in methods in Qiskit or other SDKs). Re-run the VQE and verify that the energy bias is reduced, noting the potential increase in the result's variance [2].

- Optimizer Re-assessment: Re-evaluate your chosen optimizer's performance in the context of the error-mitigated results, as the optimization landscape has been altered.

The Scientist's Toolkit

The table below lists key computational tools and methods used in advanced VQE research.

| Tool / Method | Function in VQE Research |

|---|---|

| Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz (VHA) | A problem-informed PQC designed from the molecular Hamiltonian itself, helping to preserve symmetries and reduce parameters [1]. |

| CMA-ES Optimizer | A population-based, gradient-free optimization algorithm known for its high resilience to the sampling noise present in NISQ devices [1]. |

| SPSA Optimizer | A stochastic optimizer that approximates the gradient using only two measurements, making it efficient and noise-resistant [1]. |

| Hartree-Fock Initialization | A classical computation that provides a high-quality starting point for VQE parameters, significantly speeding up convergence [1]. |

| Measurement Error Mitigation | A suite of techniques used to characterize and correct for readout errors on quantum hardware, reducing bias in expectation values at the cost of increased variance [2]. |

| Simulated Annealing for Ansatz Search | An advanced meta-optimization technique that evolves the structure (topology) of the ansatz circuit itself to improve performance [5]. |

| 5,6,7,8-Tetrahydroisoquinolin-8-ol | 5,6,7,8-Tetrahydroisoquinolin-8-ol, CAS:139484-32-5, MF:C9H11NO, MW:149.19 g/mol |

| 3-(5-Bromopyridin-2-yl)oxetan-3-ol | 3-(5-Bromopyridin-2-yl)oxetan-3-ol, CAS:1207758-80-2, MF:C8H8BrNO2, MW:230.061 |

The following diagram shows how these tools and methods relate in a comprehensive VQE optimization strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a Barren Plateau? A barren plateau is a phenomenon in the training landscape of variational quantum algorithms where the gradient of the cost function vanishes exponentially with the number of qubits [6]. When parameters are randomly initialized in a sufficiently complex, random circuit structure, the optimization landscape becomes overwhelmingly flat. This makes it exceptionally difficult for gradient-based optimization methods to find a direction to improve and locate the global minimum [7].

What causes Barren Plateaus? The primary cause is related to the concentration of measure in high-dimensional spaces. For a wide class of random parameterized quantum circuits (RPQCs), the circuit either in its entirety or in its constituent parts approximates a Haar random unitary or a unitary 2-design [6]. In these cases:

- The average value of the gradient is zero: (\langle \partial_k E \rangle = 0) [6].

- The variance of the gradient vanishes exponentially: (\text{Var}[\partial_k E] \propto 1/2^{2n}), where (n) is the number of qubits [6]. This means that with high probability, any randomly chosen initial point will have an exponentially small gradient, stranding the optimizer.

Are all ansätze equally susceptible to Barren Plateaus? No, the choice of ansatz is critical. Problem-inspired ansätze, such as the Hamiltonian Variational Ansatz (HVA), can exhibit more favorable structural properties. Studies have shown that HVA can display mild or entirely absent barren plateaus and have a restricted state space that makes optimization easier compared to a generic, hardware-efficient ansatz (HEA) [8]. The HVA's structure, derived from the problem's Hamiltonian, avoids the high randomness associated with barren plateaus.

How does sampling noise relate to Barren Plateaus? Sampling noise from a finite number of measurement shots (e.g., 1,000 shots) introduces statistical fluctuations that can further distort the optimization landscape [1]. This noise can obscure true energy gradients and create false local minima, exacerbating the challenges of a flat landscape. The choice of classical optimizer becomes crucial under these conditions, with some population-based algorithms showing greater resilience to this noise compared to gradient-based methods [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Mitigating Barren Plateaus

Symptom: Optimization stalls with minimal improvement; gradients are consistently near zero.

Diagnosis: This is the characteristic sign of a barren plateau. To confirm, you can perform a gradient analysis.

Experimental Protocol for Gradient Analysis [7]:

- Define a Random Circuit Model: Create a parameterized quantum circuit with a structure suspected of causing barren plateaus (e.g., a hardware-efficient ansatz with alternating layers of random single-qubit rotations and entangling gates).

- Sample Initial Points: Generate a large number (e.g., 300) of random initial parameter sets ({\theta^{(i)}}).

- Compute Analytical Gradients: For each parameter set, calculate the partial derivative of the cost function with respect to a specific parameter (e.g., the first parameter, (\theta{1,1})) using the analytic gradient formula: [ \partial \theta{j} \equiv \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \thetaj} = \frac{1}{2} \big[\mathcal{L}(\thetaj + \frac{\pi}{2}) - \mathcal{L}(\theta_j - \frac{\pi}{2})\big] ]

- Analyze Statistics: Compute the mean and variance of the sampled gradients. A mean near zero and an exponentially small variance (decreasing with qubit count) confirm a barren plateau.

Solution Strategies:

- Switch to a Problem-Inspired Ansatz: Instead of a generic hardware-efficient ansatz, use an ansatz that incorporates knowledge of the problem. The Hamiltonian Variational Ansatz (HVA) and the truncated Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz (tVHA) have been shown to mitigate barren plateaus by constraining the search space to a physically relevant subspace [1] [8].

- Use Non-Gradient Optimizers: In noisy environments, gradient-free optimizers can be more robust. Consider using population-based optimizers like the Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES), which has demonstrated greater resilience under sampling noise conditions [1].

- Implement Smart Initialization: Do not initialize parameters randomly. Use a classically computed initial state, such as the Hartree-Fock state for quantum chemistry problems. This can reduce the number of function evaluations by 27–60% and consistently yields higher final accuracy by starting the optimization in a more promising region of the landscape [1].

- Avoid Over-Parameterization: While over-parameterization can sometimes make landscapes more trap-free [8], it is essential to balance this with the expressibility of the circuit. An ansatz that is too expressive and random will likely induce a barren plateau.

The following flowchart summarizes the diagnostic and mitigation process:

Quantitative Analysis of Gradient Concentration

The table below summarizes the core probabilistic and deterministic characteristics of gradient concentration in barren plateaus.

| Aspect | Probabilistic Concentration | Deterministic Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Based on the concentration of measure phenomenon in high-dimensional spaces [6]. | Arises from specific, non-random ansatz structures that inherently limit the explorable state space [8]. |

| Mathematical Foundation | Levy's Lemma; the circuit forms a unitary 2-design [6]. | Restricted state space of the ansatz; mild entanglement growth [8]. |

| Gradient Mean | (\langle \partial_k E \rangle = 0) [6] | Not necessarily zero, but the effective gradient in the constrained space can be small. |

| Gradient Variance | (\text{Var}[\partial_k E] \propto \frac{- \mathrm{Tr}(H^2)}{(2^{2n} - 1)}) (vanishes exponentially with qubit count (n)) [6] | Variance is not subject to the same exponential decay due to the structured ansatz [8]. |

| Ansatz Examples | Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA), deep random circuits [6]. | Hamiltonian Variational Ansatz (HVA) [8]. |

| Mitigation Approach | Avoid unstructured randomness; use local cost functions. | Leverage problem structure to design an ansatz that avoids high entanglement where not needed. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

This table lists key computational and algorithmic "reagents" essential for experimenting with and mitigating barren plateaus.

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Unitary 2-Design Circuit | A circuit ensemble that mimics the Haar measure up to the second moment. Used as a model to rigorously study and demonstrate the barren plateau phenomenon in its most pronounced form [6]. |

| Gradient Analysis Tool | Software (e.g., as found in Paddle Quantum [7]) that calculates the analytical gradients of a parameterized quantum circuit. Essential for diagnosing barren plateaus by sampling and analyzing gradient statistics. |

| Hamiltonian Variational Ansatz (HVA) | A problem-inspired ansatz that constructs the circuit from the terms of the problem's Hamiltonian. Its structured nature avoids the high randomness that leads to barren plateaus, making it a key reagent for mitigation studies [8]. |

| CMA-ES Optimizer | A gradient-free, population-based classical optimization algorithm. It is a crucial tool for optimizing variational algorithms in the presence of noise and flat landscapes, as it is less reliant on precise gradient information [1]. |

| Hartree-Fock Initial State | A classically computed reference state. Using it to initialize the quantum circuit, rather than random parameters, places the optimizer in a more favorable region of the cost landscape, significantly improving convergence and final accuracy [1]. |

| 1,2-DIIODO-4,5-(DIHEXYLOXY)BENZENE | 1,2-Diiodo-4,5-(dihexyloxy)benzene |

| 1-(4-Methoxy-1-naphthyl)ethanone | 1-(4-Methoxy-1-naphthyl)ethanone, CAS:24764-66-7, MF:C13H12O2, MW:200.23 g/mol |

Experimental Protocol: Comparing Optimizer Performance in Noisy Environments

Objective: To evaluate the resilience of different classical optimizers when training a variational quantum algorithm under the influence of sampling noise, a condition that can mimic or worsen the effects of a barren plateau.

Methodology [1]:

- System Selection: Choose a test molecule (e.g., Hâ‚‚, LiH) and map its electronic structure problem to a qubit Hamiltonian.

- Ansatz Preparation: Select two types of ansätze for comparison:

- A hardware-efficient ansatz (as a control known to be susceptible to issues).

- A problem-inspired ansatz like the tVHA.

- Initialization: Initialize one set of parameters randomly and another set using the Hartree-Fock solution.

- Optimizer Setup: Select a suite of optimizers to test, including:

- Gradient-based: BFGS, Gradient Descent (GD), SPSA.

- Gradient-free: COBYLA, Nelder-Mead (NM), CMA-ES, Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO).

- Noise Introduction: Simulate the quantum computer's finite sampling by estimating expectation values with a limited number of shots (e.g., 1000 shots) to introduce sampling noise.

- Execution & Metrics: For each combination (ansatz × initialization × optimizer), run the optimization and record:

- The number of function evaluations to convergence.

- The final accuracy (energy error) achieved.

- The consistency of convergence across multiple runs.

Expected Outcome: The experiment will generate data similar to the following table, illustrating performance trade-offs:

| Optimizer Type | Example Algorithm | Relative Resilience to Sampling Noise | Final Accuracy (Typical) | Computational Cost per Step |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-based | BFGS | Low [1] | High (in noiseless conditions) [1] | Medium-High |

| Gradient-based | SPSA | Medium [1] | Medium | Low (only 2 evaluations) |

| Gradient-free / Population-based | CMA-ES | High [1] | High [1] | High |

| Gradient-free | COBYLA | Low-Medium | Medium | Medium |

This protocol provides a standardized way to benchmark strategies and guide the selection of the most robust optimization pipeline for a given problem and hardware setup.

Impact of Noise on Circuit Depth and Qubit Coherence in NISQ Devices

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary noise sources that limit circuit depth in my VQA experiments?

The main noise sources in NISQ devices are decoherence and gate errors. Decoherence causes qubits to lose their quantum state over time, fundamentally limiting the duration for which computations can run. Gate errors are small inaccuracies introduced with each quantum operation. On current hardware, single-qubit gate fidelities are typically 99-99.5%, while two-qubit gate fidelities range from 95-99% [9]. With error rates around 0.1% per gate, circuits become unreliable after roughly 1,000 gates [10] [9], creating a direct relationship between noise accumulation and maximum achievable circuit depth.

Q2: My VQA optimization is stalling. Could "barren plateaus" be the cause, and how does noise contribute?

Yes, barren plateaus—regions where the cost function gradient vanishes—are a common optimization challenge exacerbated by noise. As circuit depth or qubit count increases, the probability of encountering barren plateaus grows significantly [10]. Noise further degrades the optimization landscape, making gradients harder to estimate and slowing or completely stopping convergence [11]. This problem becomes particularly severe in deeper circuits where noise accumulation is more pronounced.

Q3: What practical error mitigation techniques can I implement without full quantum error correction?

Several effective error mitigation techniques are available for NISQ devices:

- Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE): Artificially amplifies circuit noise and extrapolates results to the zero-noise limit [9] [12].

- Symmetry Verification: Exploits conservation laws inherent in quantum systems to detect and discard erroneous results [9].

- Probabilistic Error Cancellation: Reconstructs ideal quantum operations as linear combinations of noisy operations [9].

- Structure-Preserving Error Mitigation: Uses calibration circuits that mirror your original circuit's structure to characterize noise without architectural modifications [12].

These techniques typically increase measurement requirements by 2x to 10x or more, creating a trade-off between accuracy and experimental resources [9].

Q4: Are there specific ansatz designs that are more robust to noise?

Yes, certain ansatz designs demonstrate better noise resilience:

- Ladder-type ansatz circuits with sparse two-qubit connectivity can be optimized using additional qubits and mid-circuit measurements to significantly reduce depth [13] [14].

- Sequentially Generated (SG) ansatz constructs circuits in layers with lower overall complexity, reducing operation count and error accumulation [15].

- Hard-constrained ansatz for specific problems like QAOA enforces transitions only within feasible subspaces, potentially reducing sensitivity to noise [11].

Q5: How do I choose between making my circuits shallower versus using more qubits?

This decision depends on your hardware's specific error characteristics. Research shows that non-unitary circuits (using extra qubits, mid-circuit measurements, and classical control) outperform traditional unitary circuits when two-qubit gate error rates are relatively low compared to idling error rates [13] [14]. The table below compares these approaches:

Table: Circuit Design Trade-offs for Noise Resilience

| Circuit Type | Key Features | Best-Suited Hardware Profile | Error Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Unitary | Standard quantum gates | Low idling error rates | Quadratic with qubit count [14] |

| Non-Unitary | Additional qubits, mid-circuit measurements | Low two-qubit gate errors | Linear with qubit count [14] |

| SG Ansatz | Sequential layers, polynomial complexity | Various NISQ devices | Lower gate complexity [15] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Rapid Performance Degradation with Increasing Circuit Depth

Symptoms:

- VQA convergence deteriorates when adding more layers to your ansatz

- Measurement outcomes become increasingly random with deeper circuits

- Inconsistent results between runs with identical parameters

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Check Coherence Time Limitations:

- Calculate whether your circuit duration approaches the Tâ‚ or Tâ‚‚ times of your qubits

- Solution: Implement depth optimization techniques like replacing unitary circuits with measurement-based equivalents to reduce latency [13]

Analyze Error Budget:

- Profile your circuit to identify dominant error sources

- Solution: If idling errors dominate, consider non-unitary designs; if gate errors dominate, optimize gate sequences [14]

Implement Error Mitigation:

- Apply ZNE for gradual error reduction

- Use symmetry verification for problems with inherent conservation laws [9]

Problem: Unstable VQA Optimization Landscape

Symptoms:

- Erratic cost function behavior during optimization

- Inability to converge even with increased shot counts

- High sensitivity to initial parameters

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Address Barren Plateaus:

- Solution: Implement parameter-filtered optimization that focuses only on active parameters, reducing the search space [11]

Optimize Classical Optimizer Selection:

- Solution: Benchmark optimizers like COBYLA, Dual Annealing, and Powell Method under your specific noise conditions [11]

Adapt Ansatz Design:

- Solution: For combinatorial problems, consider compact permutation encoding (Lehmer coding) that reduces qubit requirements to O(n log n) [5]

Problem: Inconsistent Results Across Hardware Platforms

Symptoms:

- Same algorithm performs differently on various quantum processors

- Varying optimal parameter sets for different hardware

- Unpredictable performance changes over time

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Characterize Hardware-Specific Noise:

- Solution: Use machine learning approaches to predict noise parameters (laser intensity fluctuation, temperature, measurement error) from output distributions [16]

Develop Hardware-Adaptive Circuits:

- Solution: Use simulated annealing to evolve ansatz topology specifically for your target hardware [5]

Implement Structure-Preserving Calibration:

- Solution: Employ calibration circuits that maintain your original circuit architecture while characterizing noise [12]

Experimental Protocols for Noise Characterization

Protocol 1: Circuit Depth Optimization Using Non-Unitary Design

Purpose: Reduce circuit depth while maintaining functionality through measurement-based techniques.

Methodology:

- Identify Ladder Structures: Locate sequential CX gate patterns in your ansatz that form linear chains [13]

- Substitute with Measurement-Based Equivalents: Replace CX gates with equivalent circuits using auxiliary qubits, mid-circuit measurements, and classically controlled operations

- Commute Measurements: Where possible, move all measurements to the circuit end to simplify execution

- Benchmark Performance: Compare depth reduction and fidelity against original unitary circuit

Table: Key Components for Depth-Optimized Circuit Implementation

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Auxiliary Qubits | Additional qubits initialized to | 0⟩ or | +⟩ states to enable non-unitary gate implementation [13] |

| Mid-Circuit Measurement | Measurements performed during circuit execution (not just at end) to enable classical control [13] [14] | ||

| Classically Controlled Operations | Quantum gates whose application depends on measurement outcomes [13] [14] | ||

| Calibration Matrix | Linear transformation mapping ideal to noisy outputs for error characterization [12] |

Protocol 2: Structure-Preserving Error Mitigation

Purpose: Characterize and mitigate gate errors without modifying circuit architecture.

Methodology:

- Construct Identity Circuit: Create a calibration circuit V^mit that shares identical structure with your target circuit V but implements identity operation [12]

- Measure Calibration Matrix: For all computational basis states |ψᵢ⟩, measure Mᵢ,ⱼ^mit = ⟨ψⱼ|V_noisy^mit|ψᵢ⟩ to construct the full calibration matrix [12]

- Apply Mitigation: Use the calibration matrix to correct results from your target circuit

- Validate with Known Systems: Test the method on systems with known theoretical predictions [12]

Protocol 3: Parameter-Filtered Optimization for VQAs

Purpose: Improve optimization efficiency by reducing parameter space dimensionality.

Methodology:

- Perform Cost Function Landscape Analysis: Visually identify active and inactive parameters in your optimization space [11]

- Filter Inactive Parameters: Fix parameters that show minimal impact on cost function

- Optimize in Reduced Space: Apply classical optimizers to the subset of active parameters only

- Validate Solution Quality: Compare results against full parameter space optimization [11]

Visualization of Key Concepts

In Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs), an ansatz—a parameterized quantum circuit—is the core of the solution. Its design is governed by two fundamental properties: expressibility, the circuit's ability to represent a wide range of quantum states, and trainability, the ease of finding the optimal parameters. These properties are deeply intertwined, often creating a significant trade-off. Highly expressive ansätze can explore more of the solution space but often lead to the barren plateau phenomenon, where gradients vanish exponentially with system size, making optimization intractable [17] [18]. This technical guide addresses common challenges and questions in navigating this trade-off for effective ansatz design.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Vanishing Gradients (Barren Plateaus)

Symptoms: Parameter updates become exceedingly small during optimization, regardless of the initial parameters. The cost function appears flat, and the classical optimizer fails to converge.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Overly Expressive Ansatz | Calculate the variance of the cost function gradient across random parameter initializations. Exponentially small variance indicates a barren plateau [19]. | Switch to a problem-inspired ansatz [17] [18], use a shallow Hardware Efficient Ansatz (HEA) [20], or employ classical metaheuristic optimizers like CMA-ES or iL-SHADE [19] [21]. |

| Noisy Hardware | Run the same circuit on a simulator and compare gradient magnitudes. Significant degradation on hardware suggests noise-induced barren plateaus [19]. | Implement error mitigation techniques (e.g., zero-noise extrapolation) and reduce circuit depth using hardware-efficient designs [22]. |

| Entangled Input Data | Analyze the entanglement entropy of your input states. For QML tasks, input data following a volume law of entanglement can cause barren plateaus in HEAs [20]. | For area-law entangled data, a shallow HEA is suitable. For volume-law data, consider alternative, less expressive ansätze [20]. |

Problem: Poor Convergence or Inaccurate Results

Symptoms: The optimizer converges to a high cost value, gets stuck in a local minimum, or the final solution quality is low.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Mismatched Expressibility | Identify the nature of your problem's solution. Is it a computational basis state (e.g., for QUBO problems) or a complex superposition state (e.g., for quantum chemistry)? [17] | For basis-state solutions (e.g., diagonal Hamiltonians), use low-expressibility circuits. For superposition-state solutions (e.g., non-diagonal Hamiltonians), use high-expressibility circuits [17]. |

| Ineffective Classical Optimizer | Benchmark different optimizers on a small-scale instance of your problem. Gradient-based methods often fail under finite-shot noise [19]. | In noisy conditions, use robust metaheuristics like CMA-ES, iL-SHADE, or Simulated Annealing. Avoid standard PSO and GA, which degrade sharply with noise [19] [21]. |

| Poor Parameter Initialization | Run the VQE multiple times with different random seeds. High variance in final results indicates sensitivity to initial parameters. | For chemistry problems, initializing parameters to zero has been shown to provide stable convergence [22]. Using an educated guess based on problem knowledge can also help [18]. |

Problem: Algorithm Performance Degrades Under Noise

Symptoms: Results are significantly more accurate on a noiseless simulator than on real hardware. Performance does not scale reliably with increased circuit depth.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Deep, Complex Circuits | Compare the circuit depth and number of gates against your hardware's reported coherence times and gate fidelities. | For problems with superposition-state solutions under noise, circuits with intermediate expressibility often outperform highly expressive ones [17]. Prioritize noise-resilient, low-depth ansätze. |

| Lack of Error Mitigation | Check if readout error or gate error mitigation is enabled in your quantum computing stack. | Integrate error mitigation techniques such as zero-noise extrapolation or probabilistic error cancellation into your VQE workflow [22]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I quantitatively measure the expressibility of an ansatz? Expressibility can be quantified by how well the ansatz approximates the full unitary group. One common metric is based on the Kullback-Leibler divergence between the distribution of fidelities generated by the ansatz and the distribution generated by Haar-random unitaries [18]. More recently, Hamiltonian expressibility has been introduced as a problem-specific metric, measuring a circuit's ability to uniformly explore the energy landscape of a target Hamiltonian [17].

Q2: What is the concrete relationship between expressibility and trainability? The relationship is a fundamental trade-off:

- High Expressibility: The ansatz can generate a vast set of states, increasing the chance the true solution is within reach. However, this often leads to a flat optimization landscape (barren plateaus), making it hard to train [17] [18].

- Low Expressibility: The search space is smaller and typically easier to navigate, but it risks not containing a high-quality solution to the problem. The goal is to find an ansatz in the "sweet spot"—expressive enough for the problem but not so expressive that it becomes untrainable [18].

Q3: When should I use a Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA) versus a Problem-Inspired Ansatz? The choice hinges on your problem and the available hardware.

- Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA): Uses native gates and connectivity of a specific device to minimize circuit depth and noise. Use it when you have no strong problem-specific intuition or for QML tasks where the input data follows an area law of entanglement. Avoid it for tasks with volume-law entangled data, as it will be untrainable [20].

- Problem-Inspired Ansatz: Incorporates known symmetries and structure of the problem (e.g., UCCSD for quantum chemistry). Use it when problem knowledge is available, as it typically leads to more accurate results and can avoid barren plateaus by restricting the search to a physically relevant subspace [17] [22].

Q4: How does noise affect the choice of ansatz? Noise significantly alters the expressibility-trainability balance. Under ideal conditions, high expressibility is beneficial for complex problems. However, under noisy conditions:

- For problems with basis-state solutions, low-expressibility circuits remain preferable.

- For some problems with superposition-state solutions, circuits with intermediate expressibility now yield the best performance, as highly expressive circuits are more severely impacted by noise due to their greater depth and complexity [17].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Evaluating Hamiltonian Expressibility

This protocol estimates how uniformly an ansatz explores the energy landscape of a specific Hamiltonian [17].

- Define Target Hamiltonian: Specify the Hamiltonian

Hfor your problem. - Select Ansatz Circuit: Choose the parameterized quantum circuit

U(θ)to be evaluated. - Monte Carlo Sampling: Randomly sample a large set of parameter vectors

{θ}from a uniform distribution. - Compute Energies: For each sampled

θ, prepare the state|ψ(θ)⟩ = U(θ)|0⟩and compute the expectation valueE(θ) = ⟨ψ(θ)|H|ψ(θ)⟩. - Analyze Distribution: The Hamiltonian expressibility is quantified by analyzing the distribution of the computed energies

{E(θ)}. A more expressive ansatz will produce a distribution that more uniformly covers the eigenspectrum ofH.

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Optimizers for Noisy VQE

This protocol identifies the most robust classical optimizer for your VQE problem under realistic noise conditions [19] [21].

- Problem Selection: Choose a benchmark model (e.g., 1D Ising model, Fermi-Hubbard model).

- Ansatz Fixing: Select a single ansatz design for the benchmark.

- Optimizer Pool: Compile a list of candidate optimizers, including gradient-based (e.g., Adam) and metaheuristic (e.g., CMA-ES, iL-SHADE, PSO) methods.

- Run Optimization: For each optimizer, run the VQE to minimize the energy, using a fixed number of shots per measurement to simulate sampling noise.

- Metrics & Comparison: Record the final energy accuracy, convergence speed, and stability across multiple runs. Rank the optimizers based on their consistent performance.

The workflow for a comprehensive ansatz evaluation, integrating the concepts and protocols above, can be summarized as follows:

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Ansatz Experiments

The following table details key "reagents" or components essential for conducting ansatz design and optimization experiments.

| Item Name | Function & Role in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Parameterized Quantum Circuit (PQC) | The core "reagent"; a template for the quantum state, defined by a sequence of parameterized gates. Its structure dictates expressibility [18]. |

| Classical Optimizer (e.g., CMA-ES, Adam) | Acts as the "catalyst" for the reaction. It adjusts the parameters of the PQC to minimize the cost function. Choice is critical for overcoming noise and barren plateaus [19] [22]. |

| Cost Function (e.g., Energy ⟨H⟩) | The "reaction product" being measured. It defines the objective of the VQA, typically the expectation value of a problem-specific Hamiltonian [17] [18]. |

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA) | A specific type of PQC "formulation" designed for low-depth execution on specific hardware, trading off problem-specific information for reduced noise [20]. |

| Problem-Inspired Ansatz (e.g., UCCSD) | A specialized PQC "formulation" that incorporates known physical symmetries of the problem, often leading to better accuracy but potentially higher circuit depth [17] [22]. |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | The "purification agents" for noisy experiments. Methods like zero-noise extrapolation reduce the impact of hardware errors without full error correction [22]. |

Advanced Ansatz Design and Real-World Applications in Drug Development

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How do mid-circuit measurements fundamentally reduce circuit depth? Mid-circuit measurements, combined with feedforward operations, enable constant-depth implementation of quantum sub-routines that would normally scale linearly with qubit count. By measuring qubits at intermediate stages, you can condition subsequent quantum operations on classical outcomes, breaking up long sequential gate sequences into parallelizable operations. This technique can transform operations like quantum fan-out and long-range CNOT gates from O(n) depth to constant depth [23] [24].

2. What are the main sources of error when using mid-circuit measurements? The primary error sources include:

- Dephasing during measurement: Measurement operations are relatively slow (~4μs on current IBM systems), exposing other qubits to decoherence [25]

- Classical processing latency: Slow conditional operations can introduce errors in unmeasured qubits waiting for classical decisions [26]

- Measurement infidelity: Imperfect measurements can lead to incorrect feedforward operations [25] [26]

- Reset errors: Imperfect qubit reset after measurement contaminates subsequent computations [25]

3. When should I prioritize circuit depth reduction over qubit count? Prioritize depth reduction when:

- Your algorithm is limited by qubit coherence times [24]

- You're working on NISQ devices with significant gate error rates [23]

- The depth reduction provides more benefit than the cost of additional qubits [23] For fault-tolerant systems or algorithms with ample coherence time, qubit count may take priority.

4. How does the trade-off between depth and width work in practice? The depth-width trade-off allows you to optimize quantum computation for specific hardware constraints. By introducing auxiliary qubits and mid-circuit measurements, you can achieve substantial depth reduction while increasing the total qubit count (width). Research demonstrates transformations that reduce depth from O(log dn) to O(log d) while increasing width from O(dn/log d) to O(dn) [23].

5. Can I implement these techniques on current quantum hardware? Yes, mid-circuit measurement and conditional reset are currently available on IBM Quantum systems via dynamic circuits [25]. However, you must account for hardware-specific limitations including measurement duration, reset fidelity, and classical processing speed. Real-world implementations have demonstrated 400x fidelity improvements for certain algorithms [25].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Excessive decoherence during mid-circuit measurement sequences

Symptoms: Deteriorating output fidelity, inconsistent results between runs, significant drop in success probability for feedforward operations.

Solutions:

- Minimize measurement duration: Group measurements strategically and use hardware-specific measurement optimizations [25]

- Temporal isolation: Schedule operations on unmeasured qubits during measurement/classical processing periods [26]

- Error mitigation: Use symmetry verification and post-selection to identify and discard corrupted runs [23] [25]

- Reset validation: Implement measurement-and-reset cycles with verification to ensure clean qubit reinitialization [25]

Problem: Incorrect feedforward operations due to measurement errors

Symptoms: Systematic errors in conditional gates, violation of expected symmetry properties, inconsistent algorithmic performance.

Solutions:

- Measurement error mitigation: Use measurement error mitigation techniques like confusion matrix inversion [25]

- Majority voting: Perform repeated measurements for critical decision points [23]

- Error-adaptive design: Design circuits where common measurement errors result in correctable Pauli errors [23]

- Verification layers: Include additional stabilizer measurements to detect and correct feedforward errors [25]

Problem: Insufficient qubits for desired depth reduction techniques

Symptoms: Cannot implement required parallel operations, compromised circuit depth due to qubit limitations.

Solutions:

- Qubit reuse: Strategically reset and reuse qubits after their primary function is complete [25]

- Partial implementation: Apply depth reduction only to most critical circuit sections [23]

- Compact encoding: Use efficient state encodings like compact permutation encoding (O(n log n) qubits instead of O(n²)) [5]

- Hierarchical design: Implement multi-level depth reduction focusing on most beneficial transformations first [23]

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Circuit Depth Reduction Techniques and Their Costs

| Technique | Depth Reduction | Qubit Overhead | Key Applications | Hardware Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement-based fan-out | O(n) → O(1) [24] | O(N) auxiliary qubits [23] | State preparation, logical operations [23] | Mid-circuit measurement, feedforward [25] |

| Constant-depth transformation | O(log dn) → O(log d) [23] | Increases from O(dn/log d) to O(dn) [23] | Sparse state preparation, Slater determinants [23] | Dynamic circuits, reset capability [25] |

| Qubit reset and reuse | Varies by algorithm | Reduces total qubit need [25] | Quantum simulation, arithmetic operations [25] | High-fidelity reset operations [25] |

| Compact encoding | Indirect via reduced operations | O(n log n) vs O(n²) [5] | Combinatorial optimization [5] | Standard gate operations [5] |

Table 2: Error Characteristics and Mitigation Strategies

| Error Type | Typical Magnitude | Impact on Computation | Effective Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement dephasing | Significant on current hardware [25] | Decoherence in unmeasured qubits | Temporal scheduling, error suppression [26] |

| Reset infidelity | ~1% on IBM Falcon processors [25] | Contaminated initial states | Verification measurements, repeated reset [25] |

| Classical latency | Microsecond scale [26] | Increased exposure to decoherence | Parallel classical processing, optimized control [26] |

| Feedforward gate errors | Amplifies base gate errors [23] | Incorrect conditional operations | Measurement repetition, error-adaptive design [23] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Constant-Depth Fan-Out Gates

Purpose: Execute multi-target quantum operations in constant depth using mid-circuit measurements.

Materials:

- Quantum processor with mid-circuit measurement capability

- Classical control system supporting feedforward operations

- Sufficient auxiliary qubits (scale with operation size)

Methodology:

- Initialization: Prepare the control qubit in the desired state and auxiliary qubits in |0⟩

- Entanglement creation: Create maximal entanglement between control and auxiliary qubits using parallel two-qubit gates

- Mid-circuit measurement: Measure auxiliary qubits in appropriate basis

- Classical processing: Process measurement outcomes to determine correction operations

- Feedforward execution: Apply conditional gates based on classical outcomes

- Verification: Validate operation success through tomography or process fidelity measurement

Expected Results: The fan-out operation (copying control state to multiple targets) completes in constant time regardless of system size, with fidelity limited by measurement and gate errors [23] [24].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If fidelity decreases with system size, check measurement cross-talk and timing

- For slow classical processing, optimize feedforward path or use simpler correction rules

- If reset errors accumulate, implement verification measurements before critical operations [25]

Protocol 2: Depth-Reduced State Preparation for Quantum Simulation

Purpose: Prepare complex quantum states relevant to quantum simulation with reduced depth.

Materials:

- Quantum processor supporting dynamic circuits

- Classical optimizer for parameter tuning

- State tomography setup for verification

Methodology:

- Unary encoding bridge: Use intermediate unary encoding to transform between quantum states [23]

- Parallelized operations: Implement transformation using constant-depth logical operations [23]

- Mid-circuit verification: Include symmetry verification measurements to detect errors [23]

- Conditional correction: Apply correction operations based on verification results

- Output validation: Measure target state fidelity using quantum state tomography

Key Operations:

- Constant-depth OR and AND gates using measurements and feedforward [23]

- Parallel application of commuting gates [23]

- Symmetry-based error detection and correction [23]

Expected Results: Preparation of target states (e.g., symmetric states, Slater determinants) with O(log d) depth instead of O(log dn), with success probability dependent on measurement outcomes and error rates [23].

Visualization of Techniques

Mid-Circuit Measurement Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for Depth-Reduced Quantum Circuits

| Component | Function | Implementation Examples | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Circuit Controller | Executes mid-circuit measurements and feedforward | IBM Dynamic Circuits [25], PennyLane MCM [27] | Classical processing speed, measurement latency |

| High-Fidelity Reset | Reinitializes qubits after measurement | Measurement + conditional X gate [25] | Reset fidelity, reset duration |

| Auxiliary Qubit Pool | Provides workspace for parallel operations | Additional qubits beyond algorithm minimum [23] | Coherence time, connectivity to main qubits |

| Measurement Error Mitigation | Corrects measurement inaccuracies | Confusion matrix inversion, repetition codes [25] | Measurement fidelity, overhead cost |

| Classical Feedforward Unit | Processes outcomes and triggers conditional gates | FPGA controllers, real-time classical processing [26] | Decision latency, gate timing precision |

The Sequentially Generated (SG) Ansatz for Quantum Many-Body Problems

Troubleshooting Common SG Ansatz Implementation Issues

This section addresses specific challenges you might encounter when implementing the Sequentially Generated (SG) ansatz in your variational quantum algorithms.

FAQ 1: Why is my SG ansatz failing to converge to the true ground state energy?

- Problem: The variational optimization is stuck in a local minimum or shows slow convergence.

- Diagnosis: This is often due to an insufficient circuit depth (number of layers) in your SG ansatz, which limits its expressiveness. The SG ansatz approximates the target state with a matrix product state (MPS) of a specific bond dimension; an insufficient depth means the bond dimension is too low to represent the true ground state accurately [15].

- Solution:

- Systematically increase the number of layers in your SG ansatz circuit.

- Monitor the convergence of the energy with each increase. The energy should approach a stable value as the depth becomes sufficient [15].

- For 2D systems, ensure your ansatz is configured to generate string-bond states, which are the natural extension for these geometries [28].

FAQ 2: My quantum circuit depth is too high, leading to significant noise on my NISQ device. How can I optimize this with the SG ansatz?

- Problem: The circuit requires more quantum gate operations than your noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) hardware can reliably execute.

- Diagnosis: While the SG ansatz is designed for polynomial complexity, the initial design might not be optimized for your specific problem, leading to redundant operations [15].

- Solution: The SG ansatz has demonstrated lower circuit complexity compared to alternatives like the Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) ansatz. Leverage its inherent efficiency by verifying that your implementation correctly constructs the circuit in layers, which allows it to generate complex states with relatively few operations [15]. Benchmark its performance against other ansatze for your specific molecule or many-body system to confirm its gate efficiency [28].

FAQ 3: How do I use the SG ansatz for reconstructing an unknown quantum state from experimental data?

- Problem: You have measurement data from a quantum system but need to reconstruct the underlying quantum state.

- Diagnosis: The SG ansatz is well-suited for this task if the unknown state can be efficiently represented as a matrix product state (MPS) [15].

- Solution: Use a variational method where the parameters of the SG ansatz are optimized to closely match your experimental measurements.

- Initialization: Prepare an initial guess for the SG ansatz parameters.

- Cost Function: Define a cost function that quantifies the difference between the predictions of your ansatz and the experimental data (e.g., using fidelity).

- Optimization: Employ a classical optimizer to minimize this cost function by adjusting the ansatz parameters. The SG ansatz has shown promising results in accurately reconstructing both pure and mixed states in this context [15].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

This section provides detailed, step-by-step protocols for key experiments involving the SG ansatz.

Protocol: Finding the Ground State of a Quantum Many-Body System

Objective: Use the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm with an SG ansatz to find the ground state energy of a 1D Ising model or a quantum chemistry system like the hydrogen fluoride (HF) molecule [15].

Workflow Diagram: SG Ansatz Ground State Search

Materials & Reagents:

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Quantum Processing Unit (QPU) | Executes the parameterized quantum circuit (the SG ansatz) to prepare trial wavefunctions and measure expectation values [15]. |

| Classical Optimizer | A classical algorithm (e.g., gradient descent) that adjusts the parameters of the SG ansatz to minimize the measured energy [15]. |

| SG Ansatz Circuit | The core variational circuit, built from layered operations on groups of qubits, designed to efficiently generate matrix product states [15] [28]. |

Procedure:

- System Definition: Define the Hamiltonian of the system you are studying (e.g., the 1D Ising model or the electronic structure Hamiltonian for the HF molecule).

- Ansatz Initialization: Initialize the SG ansatz with a chosen number of layers (circuit depth) appropriate for the system's complexity.

- Quantum Execution: Prepare a trial state on the quantum processor by running the SG ansatz circuit with the current set of parameters.

- Energy Measurement: Measure the expectation value of the Hamiltonian with respect to the prepared trial state.

- Classical Optimization: Feed the measured energy value to the classical optimizer. The optimizer then proposes a new set of parameters for the SG ansatz to lower the energy.

- Iteration: Iterate steps 3-5 until the energy converges to a minimum value, which is your calculated ground state energy.

Protocol: Benchmarking SG Ansatz Performance

Objective: Quantitatively compare the performance of the SG ansatz against other common ansatze, such as the Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCCSD) or ADAPT-VQE [29].

Materials & Reagents:

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Testbed Systems | A set of standard molecular (Hâ‚‚, LiH, Hâ‚‚O) and many-body (1D Ising) systems with known ground truths for reliable benchmarking [15] [29]. |

| Performance Metrics | Key metrics for comparison: final energy error, number of quantum gates (circuit complexity), and number of optimization iterations required for convergence [15]. |

Procedure:

- Select Benchmark Systems: Choose a range of benchmark systems of increasing complexity.

- Run Parallel Experiments: For each system, run the VQE algorithm using the SG ansatz and the other ansatze you are comparing against.

- Data Collection: For each run, record the final energy accuracy, the total number of quantum gate operations required, and the number of optimization iterations.

- Analysis: Compile the results into a comparative table. The SG ansatz is expected to achieve comparable or superior accuracy with lower circuit complexity [15].

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from research on the SG ansatz, providing a benchmark for your own experiments.

Table 1: SG Ansatz Performance Across Different Systems

| System/Model | Key Performance Metric | Reported Outcome | Comparison to Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D Ising Model | Accuracy in finding ground state | Effectively determined the ground state [15] | Achieved with a relatively low number of operations [15] |

| Hydrogen Fluoride (HF) | Number of quantum gate operations | Required fewer quantum operations for accurate results [15] | Outperformed traditional methods [15] |

| Water (Hâ‚‚O) | Number of quantum gate operations | Required fewer quantum operations for accurate results [15] | Outperformed traditional methods [15] |

| General Performance | Circuit Complexity | Lower circuit complexity [15] | More efficient than established alternatives [15] |

| Hâ‚‚, LiH, BeHâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚O | Expressibility & Trainability | High expressibility with shallow depth and low parameter count [29] | Performance comparable to UCCSD and ADAPT-VQE, while avoiding barren plateaus [29] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details the essential "research reagents" – the core components and concepts – needed for working with the SG Ansatz.

Table 2: Essential Components for SG Ansatz Research

| Item | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Variational Quantum Algorithm (VQA) | The overarching algorithmic framework. VQAs use a quantum computer to prepare and measure states (like the SG ansatz) and a classical computer to optimize the parameters [15]. |

| Matrix Product State (MPS) | A tensor network representation of a quantum state. The SG ansatz can efficiently generate any MPS with a fixed bond dimension in 1D, making it a powerful tool for simulating 1D quantum systems [15] [28]. |

| String-Bond State | An extension of MPS to higher dimensions. In 2D, the SG ansatz generates string-bond states, which are crucial for tackling more complex, two-dimensional quantum many-body problems [28]. |

| Expressibility Metric | A measure of how many different quantum states a given ansatz can represent. The SG ansatz is designed for high expressibility, meaning it can explore a wide region of the Hilbert space, which is key to finding accurate solutions [29]. |

| Classical Optimizer | A crucial classical algorithm (e.g., gradient-based methods) that adjusts the parameters of the SG ansatz to minimize the cost function (like energy). Its performance is critical for the convergence of the entire VQA [15]. |

| Benzoic acid, 2-(acetyloxy)-5-amino- | Benzoic acid, 2-(acetyloxy)-5-amino- |

| (4-bromophenyl)(1H-indol-7-yl)methanone | (4-bromophenyl)(1H-indol-7-yl)methanone, CAS:91714-50-0, MF:C15H10BrNO, MW:300.15 g/mol |

Ansatz Comparison and Selection Guide

Table 1: Characteristics of Hardware-Efficient and Problem-Inspired Ansatzes

| Feature | Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA) | Hamiltonian Variational Ansatz (HVA) | Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design Principle | Minimizes gate count and uses native device connectivity and gates [20] | Inspired by the problem's Hamiltonian and its adiabatic evolution [30] | Inspired by the trotterized version of adiabatic evolution [31] [32] |

| Key Advantage | Reduces circuit depth and minimizes noise from hardware [20] | Avoids barren plateaus with proper initialization [30] | Directly applicable to combinatorial optimization problems [31] |

| Primary Challenge | Can suffer from barren plateaus; may break Hamiltonian symmetries [33] [20] | Performance depends on the structure of the target Hamiltonian [30] | Performance can be limited by adiabatic bottlenecks, requiring more rounds for some problems [34] |

| Trainability | Trainable for tasks with input data obeying an area law of entanglement; likely untrainable for data with a volume law of entanglement [20] | Does not exhibit exponentially small gradients (barren plateaus) when parameters are appropriately initialized [30] | Trainability can be challenging, with the number of required rounds sometimes increasing with problem size [34] |

| Best Use Cases | Quantum Machine Learning (QML) tasks with area-law entangled data [20] | Solving quantum many-body problems and finding ground states [30] | Combinatorial optimization on graphs, such as MaxCut [31] [34] |

FAQ: How do I choose between a Hardware-Efficient Ansatz and a Problem-Inspired Ansatz like HVA or QAOA?

The choice hinges on your problem type and the primary constraint you are facing:

- For problem-agnostic applications, particularly QML, a shallow HEA can be a good choice if you can verify that your input data has low entanglement (area law). You should avoid HEA if your data is highly entangled (volume law), as this will lead to untrainable barren plateaus [20].

- For physical system simulation, such as finding the ground state of a quantum many-body model, the HVA is highly suitable. It is designed to respect the structure of the problem's Hamiltonian, and it has proven theoretical guarantees against barren plateaus, making it reliably trainable [30].

- For classical combinatorial optimization, QAOA is the natural candidate. It directly encodes the cost function of a problem (like MaxCut) into its circuit. However, be aware that it may face limitations (adiabatic bottlenecks) for larger problems, where newer approaches like the imaginary Hamiltonian variational ansatz (iHVA) might offer performance benefits [34].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Barren Plateaus

Problem: The cost function gradients are exponentially small as a function of the number of qubits, making it impossible to optimize the parameters.

Table 2: Barren Plateau Troubleshooting Guide

| Ansatz | Cause of Barren Plateaus | Solution / Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA) | Deep, randomly initialized circuits; using volume-law entangled input states [20] [30]. | Use shallow circuits; ensure input data follows an area law of entanglement [20]. |

| Hamiltonian Variational Ansatz (HVA) | Generally avoided if the circuit is well-approximated by a local time-evolution operator [30]. | Apply a specific initialization scheme that keeps the state in a low-entanglement regime during training [30]. |

| General VQAs | High expressivity of the ansatz and random parameter initialization [30]. | Use a problem-inspired ansatz (HVA, QAOA) or a parameter-constrained ansatz [30]. |

FAQ: My optimization is stuck in a barren plateau. What can I do?

- Check your ansatz depth and input data: If you are using an HEA, first try to reduce the circuit depth. More importantly, analyze the entanglement of your input state. Barren plateaus are pronounced for HEAs when the input states are highly entangled [20].

- Switch to a problem-inspired ansatz: Consider reformulating your problem to use an HVA or QAOA. The HVA, in particular, has been proven to be free from barren plateaus when its parameters are initialized appropriately, making it a robust choice [30].

- Re-initialize your parameters: Avoid completely random initialization. For HVA, follow the specific initialization strategy proposed in the literature that ensures the circuit mimics a time-evolution operator [30].

Optimization and Convergence Issues

Problem: The classical optimizer fails to find a good solution, or the convergence is unacceptably slow.

FAQ: The classical optimizer for my QAOA experiment isn't converging to a good solution. What might be wrong?

- Cause 1: Inadequate number of rounds (p): The performance of QAOA often improves with a higher number of rounds

p. Ifpis too low, the ansatz might not have enough expressibility to approximate the solution well [34]. - Cause 2: Suboptimal parameter initialization: The optimization landscape of QAOA can contain many local minima. Using better initialization strategies, such as leveraging parameter interpolation from solutions with lower

p, can help [32]. - Cause 3: Objective function evaluation: The expectation value is estimated by measuring the quantum state multiple times. Ensure you are using a sufficient number of measurement shots (repetitions) to get a reliable estimate of the cost function [32].

Hardware Noise and Circuit Depth

Problem: Results from a quantum device are too noisy, likely due to the circuit being too deep.

FAQ: How can I reduce the depth of my variational quantum algorithm circuit?

- Ansatz Selection: Start with the shallowest possible ansatz that is still expressive enough for your problem. HEAs are explicitly designed for this purpose [20].

- Circuit Compression Techniques: For certain "ladder-type" ansatz circuits, you can perform a depth-for-width trade-off. This technique involves replacing some two-qubit gates with a combination of mid-circuit measurements and classically controlled operations, which can significantly reduce the overall circuit depth at the cost of using extra auxiliary qubits [13].

- Use Hardware-Aware Compilation: Compile your circuit to use the native gates and connectivity of the target device to minimize the overhead from gate decompositions and routing [31].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Executing a QAOA for a MaxCut Problem

This protocol outlines the steps for solving a MaxCut problem using the QAOA, as demonstrated in Cirq experiments [31].

Workflow Diagram: QAOA for MaxCut

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- Problem Definition: Encode the MaxCut problem on a graph

Gwithnnodes and weightsw_jkinto a cost Hamiltonian: ( C = \sum{j{jk} Zj Zk ) [31]. }> - Parameter Initialization: Initialize the 2

pparameters (βâ‚...β_p,γâ‚...γ_p) on the classical computer. This can be done randomly or via a heuristic strategy [32]. - State Preparation (Quantum Computer): Prepare the QAOA state on the quantum processor by applying a sequence of unitaries to the initial state

|+⟩^⊗n: ( |\boldsymbol{\gamma}, \boldsymbol{\beta}\rangle = UB(\betap) UC(\gammap) \cdots UB(\beta1) UC(\gamma1) |+\rangle^{\otimes n} ) whereU_C(γ) = exp(-iγC)is the phase (problem) unitary andU_B(β) = exp(-iβ ∑ X_j)is the mixing (driver) unitary [31]. - Measurement (Quantum Computer): Measure the final state

|γ,β⟩in the computational basis to obtain a bitstring|z⟩[32]. - Expectation Calculation (Classical Computer): Calculate the expectation value

⟨C⟩by averaging the costC(z)over many measurement shots (m) from Step 4 [32]. - Classical Optimization: Use a classical optimizer (e.g., from

scipy.optimize) to update the parametersβandγwith the goal of minimizing⟨C⟩[31] [32]. - Iteration: Repeat steps 3-6 until the optimization converges. The bitstring

|z⟩with the highest energy (or found most frequently) at convergence is the proposed solution [32].

Protocol: Implementing an HVA for a Many-Body Ground State

Workflow Diagram: HVA Ground State Search

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- Hamiltonian Decomposition: Decompose the target Hamiltonian

Hinto a sum of local terms, e.g.,H = Hâ‚ + Hâ‚‚ + ...[30]. - Ansatz Construction: Construct the HVA circuit with

players. Each layer typically consists of time-evolution blocks under the different Hamiltonian terms:U(θ) = [e^{-iθ_{1,p} H_1} e^{-iθ_{2,p} H_2} ...] ... [e^{-iθ_{1,1} H_1} e^{-iθ_{2,1} H_2} ...][30]. - Parameter Initialization: This is a critical step. Do not use fully random initialization. Instead, follow a prescribed initialization strategy that ensures the initial state is close to a low-entanglement state, such as the ground state of one of the Hamiltonian terms, to avoid barren plateaus [30].

- State Preparation (Quantum Computer): Prepare the HVA state

|θ⟩on the quantum device. - Energy Measurement (Quantum Computer): Measure the expectation value

⟨H⟩ = ⟨θ|H|θ⟩using techniques like Hamiltonian averaging. - Classical Optimization (Classical Computer): Use a classical optimizer to adjust the parameters

θto minimize the energy⟨H⟩. - Iteration: Repeat steps 4-6 until convergence to the ground state energy is achieved.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Components for Ansatz Experiments

| Item / Concept | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Problem Graph | Defines the problem instance; its structure determines the cost Hamiltonian C. |

MaxCut on a 3-regular graph [31]. |

| Cost Hamiltonian (C) | Encodes the objective function of the problem into a quantum operator. | ( C = \sum{j |

| Mixer Hamiltonian (B) | Drives transitions between computational basis states; typically the sum of Pauli-X operators. | ( UB(\beta) = e^{-i \beta \sumj X_j} ) in QAOA [31]. |

| Parameterized Quantum Circuit (PQC) | The core "ansatz"; a quantum circuit with tunable parameters that prepares the trial state. | The HVA or QAOA circuit structure [30] [31]. |

| Classical Optimizer | An algorithm that adjusts the parameters of the PQC to minimize the cost function. | Gradient-based or gradient-free optimizers from libraries like scipy.optimize [31]. |

| Mid-Circuit Measurement & Classical Control | Enables non-unitary operations, used in advanced techniques for circuit depth compression [13]. | Replacing a sequence of CX gates to reduce overall circuit depth [13]. |

| Terephthalylidene bis(p-butylaniline) | Terephthalylidene bis(p-butylaniline), CAS:29743-21-3, MF:C28H32N2, MW:396.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1,1-Difluoro-3-methylcyclohexane | 1,1-Difluoro-3-methylcyclohexane CAS 74185-73-2 |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Optimization Convergence Issues in Variational Quantum Algorithms

Problem: The classical optimizer fails to converge to an accurate ground state energy when running the Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz (VHA) on a noisy quantum simulator.

Explanation: Sampling noise from finite measurements (shots) fundamentally alters the optimization landscape, creating false minima and obscuring true gradients, which causes optimizers to fail or converge to incorrect parameters [1].

Solution Steps:

- Switch to a Noise-Resilient Optimizer: Replace gradient-based optimizers (like BFGS or Gradient Descent) with population-based algorithms such as the Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES), which shows greater resilience under noisy conditions [1].

- Increase Shot Count: Increase the number of shots to approximately 1000 per energy evaluation to reduce the effect of sampling noise. Be aware that beyond this point, you may experience diminishing returns [1].

- Re-initialize from Hartree-Fock: Use the classically computed Hartree-Fock state as the initial starting point. This can reduce the number of function evaluations by 27–60% and lead to higher final accuracy compared to random initialization [1].

- Verify with a Trust-Region Method: Use a derivative-free trust-region method like COBYLA (Constrained Optimization By Linear Approximations) as a benchmark to check if the problem is noise-related or due to a rugged landscape [1].

Guide 2: Mitigating Data Scarcity for Generative AI Models in Novel Target Discovery

Problem: The Generative AI model cannot generate viable novel drug molecules because of insufficient training data for a new biological target.

Explanation: Generative AI models, such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), require large, high-quality datasets to learn abstract molecular representations and grammar. Performance drops significantly with small or fragmented datasets [35] [36].

Solution Steps:

- Employ a Hybrid Prediction-and-Generation Model: Use an architecture like ReLeaSE, which combines a generative neural network for designing molecules with a predictive neural network that forecasts properties. The predictor guides the generator even with limited data [35].

- Leverage Transfer Learning: Pre-train your model on a large, general chemical dataset (e.g., ChEMBL or ZINC). Then, fine-tune the model on the small, target-specific dataset you possess [35].

- Generate Synthetic Data: Use the generative model itself to create a larger, augmented dataset of plausible molecules for pre-training before fine-tuning on the real, small dataset.

- Implement a Reinforcement Learning (RL) Loop: Integrate a reward function within the RL framework that provides real-time feedback based on predicted properties (e.g., binding affinity, solubility), steering the generation towards desired candidates even from a limited starting set [35].

Guide 3: Managing the Computational Overhead of Quantum Circuit Simulation for Molecular Active Spaces

Problem: Simulation of the full quantum circuit for a drug-sized molecule (e.g., LiH) is computationally intractable on classical hardware.

Explanation: The vector space for an n-qubit system is 2^n-dimensional, making it challenging for a classical computer to simulate [37]. For example, representing a 100-qubit system requires storing 2¹â°â° classical values [37].

Solution Steps:

- Use an Active Space Approximation: Reduce the problem's complexity by selecting a subset of molecular orbitals (the active space) that are crucial for accurately capturing electron correlations, thus reducing the number of required qubits [1].

- Apply the Truncated VHA (tVHA): Utilize the tVHA, which uses a systematic truncation of non-Coulomb two-body terms in the Hamiltonian to minimize the parameter count and circuit depth while retaining accuracy [1].

- Leverage Hybrid Quantum-Classical Simulation: Use a software stack like Qiskit with PySCF, which allows for classical computation of molecular integrals, offloading part of the calculation from the quantum simulator [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the most suitable classical optimizer for a noisy VHA experiment? For ideal, noiseless conditions, gradient-based methods like BFGS can perform best. However, under realistic conditions with sampling noise, population-based algorithms like CMA-ES are recommended due to their greater noise resilience [1].

FAQ 2: How does the Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz (VHA) differ from other common ansatzes like UCCSD? The VHA, particularly its truncated version (tVHA), is constructed by decomposing the electronic Hamiltonian into physically meaningful subcomponents, directly encoding the problem structure. Unlike Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC), it avoids deep circuits from non-commuting Trotter steps and minimizes parameter count, helping to mitigate the barren plateau phenomenon and making it more suitable for NISQ devices [1].

FAQ 3: Our generative model produces invalid molecular structures. How can we fix this? This is often a problem of the model not fully learning the underlying "chemical grammar." To address this:

- Change the Molecular Representation: Switch from a string-based representation (like SMILES) to a graph-based representation using Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), which more naturally encodes molecular structure.

- Incorporate a Validity Checker: Integrate a rule-based or machine learning-based validator into the generative loop to penalize the generation of invalid structures during training.

- Use a VAE with a Structured Latent Space: A Variational Autoencoder can be trained to ensure the latent space is smooth and populated with points that decode to valid molecules.

FAQ 4: What is a practical starting point for the number of shots in VQE energy calculations? Benchmark studies suggest starting with around 1000 shots per energy evaluation. This number typically provides a good balance, reducing sampling noise to a manageable level without incurring excessive computational costs from diminishing returns [1].

FAQ 5: Can Generative AI and Quantum Computing be integrated in drug discovery? Yes, a synergistic integration is possible. Generative AI can be used to design and optimize novel molecular compounds in silico. Subsequently, quantum computing models, particularly variational quantum algorithms like VQE with an ansatz such as VHA, can be employed to perform precise electronic structure calculations on these candidate molecules to predict their properties and reactivity with high accuracy, guiding the selection of the most promising leads.

Data Tables

Table 1: Comparison of Classical Optimizers for VHA under Sampling Noise

| Optimizer | Type | Performance (Noiseless) | Performance (With Noise) | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BFGS | Gradient-based | Best [1] | Poor | Uses approximate second-order information for fast convergence [1]. |

| CMA-ES | Population-based | Good | Best (Most Resilient) [1] | Adapts a multivariate Gaussian to guide search in complex terrains [1]. |

| SPSA | Stochastic Gradient-based | Good | Good | Requires only two function evaluations per iteration, efficient for high-dimensional problems [1]. |

| COBYLA | Derivative-free | Good | Fair | Uses linear approximations for constrained optimization [1]. |

| Nelder-Mead | Derivative-free | Fair | Poor | A simplex-based heuristic exploring through geometric operations [1]. |

| Model | Core Mechanism | Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) | Two neural networks (Generator and Discriminator) compete to produce new data [36]. | Creates novel molecular structures with desired physicochemical properties [35] [36]. |

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Encodes input data into a latent space, then decodes to generate new data [36]. | Generates potential drugs with specific characteristics by sampling from the latent space [35] [36]. |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) | An agent takes actions (e.g., adding a molecular group) to maximize a cumulative reward [35]. | Optimizes multiple molecular properties (e.g., potency, solubility) simultaneously [35] [36]. |

| Large Language Model (LLM) | Trained on vast corpora of text to predict the next token in a sequence. | Can be trained on SMILES strings to generate novel, valid molecular structures [35]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ground State Energy Calculation of a Molecule using tVHA

Objective: To compute the ground state energy of an Hâ‚‚ molecule using the truncated Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz (tVHA) on a noisy quantum simulator.

Materials:

- Software: Python-based simulation stack with Qiskit and PySCF [1].