Benchmarking CEO-ADAPT-VQE: A Performance Analysis for Quantum-Accelerated Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive performance benchmark of the CEO-ADAPT-VQE algorithm, a hybrid quantum-classical method for molecular simulation in drug development.

Benchmarking CEO-ADAPT-VQE: A Performance Analysis for Quantum-Accelerated Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive performance benchmark of the CEO-ADAPT-VQE algorithm, a hybrid quantum-classical method for molecular simulation in drug development. Targeting researchers and pharmaceutical professionals, we explore its foundational principles, methodological applications for simulating complex molecular systems like silicon and aluminum clusters, and strategies for optimizing ansatz selection and parameter initialization to mitigate noise and convergence issues. The analysis validates CEO-ADAPT-VQE against classical computational chemistry benchmarks and competing quantum algorithms, synthesizing key findings to outline a path toward quantum advantage in preclinical research and precision medicine.

Understanding CEO-ADAPT-VQE: The Foundation for Quantum Chemical Simulation

The Role of VQE in the NISQ Era for Pharmaceutical Research

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a cornerstone algorithm for pharmaceutical research in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era. As a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm, VQE is uniquely suited to current quantum hardware limitations, offering a practical pathway for molecular simulations critical to drug discovery. The algorithm's design mitigates some effects of noise through its variational approach, making it a leading candidate for calculating molecular properties like ground state energies on today's imperfect quantum devices [1] [2].

In pharmaceutical contexts, VQE enables researchers to tackle problems that are computationally intractable for classical computers, particularly the precise simulation of molecular systems and quantum chemical calculations involved in drug design [3]. Its hybrid nature delegates the preparation and measurement of quantum states to the quantum processor while leveraging classical computers for optimization tasks, creating a synergistic framework that maximizes the utility of limited quantum resources [2]. This capability positions VQE as a transformative tool for applications ranging from covalent inhibitor design to prodrug activation profiling, potentially accelerating drug development pipelines and improving prediction accuracy for molecular interactions [3].

VQE in Action: Key Pharmaceutical Applications

Real-World Drug Design Problems

VQE is transitioning from theoretical proof-of-concept to addressing genuine drug development challenges. Researchers have developed hybrid quantum computing pipelines specifically tailored for critical tasks in pharmaceutical research:

Gibbs Free Energy Profiling for Prodrug Activation: A pivotal application involves calculating Gibbs free energy profiles for prodrug activation, particularly for covalent bond cleavage. In one case study focusing on β-lapachone—a natural product with anticancer activity—researchers employed VQE to model the carbon-carbon bond cleavage process. This simulation required precise modeling of solvation effects in the human body using the polarizable continuum model (PCM). The quantum computation successfully determined the energy barrier for C–C bond cleavage, a crucial parameter for predicting whether the reaction proceeds spontaneously under physiological conditions, thereby validating the prodrug design strategy [3].

Covalent Inhibition Simulations: VQE has been applied to study covalent inhibition mechanisms, exemplified by research on KRAS G12C inhibitors like Sotorasib (AMG 510). These investigations utilize hybrid quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) workflows where VQE enhances the understanding of drug-target interactions through detailed simulation of covalent bonding interactions, a vital component in the development of targeted cancer therapies [3].

Molecular Ground State Energy Calculations

The fundamental strength of VQE lies in calculating molecular ground state energies, a cornerstone for predicting molecular stability and reactivity:

Silicon Atom Simulations: Systematic benchmarking of VQE for calculating the ground-state energy of the silicon atom revealed that combining a chemically inspired ansatz (UCCSD) with the ADAM optimizer and zero parameter initialization yielded the most stable and precise results. The ParticleConservingU2 ansatz also demonstrated remarkable robustness across different optimizers [4].

Small Molecule Simulations: Studies on molecules like BeHâ‚‚ (Beryllium Hydride) show that even older-generation 5-qubit quantum processors, when enhanced with error mitigation techniques like Twirled Readout Error Extinction (T-REx), can achieve ground-state energy estimations an order of magnitude more accurate than those from more advanced 156-qubit devices without error mitigation [2].

VQE Performance Benchmarking and Comparison

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The evaluation of VQE performance in pharmaceutical research follows rigorous experimental protocols:

Active Space Approximation: To accommodate NISQ device limitations, researchers often employ active space approximation, simplifying the quantum chemistry region into a manageable system (e.g., two electrons/two orbitals) while maintaining computational accuracy for the targeted molecular properties [3].

Ansatz Selection and Optimization: Benchmarking studies systematically evaluate various ansatzes (UCCSD, k-UpCCGSD, Hardware-Efficient, ParticleConservingU2) combined with classical optimizers (ADAM, SPSA). The performance is assessed based on convergence stability, precision in energy estimation, and resource efficiency [4] [2].

Error Mitigation Integration: Protocols incorporate quantum error mitigation (QEM) strategies, particularly readout error mitigation techniques like T-REx, to enhance result accuracy. The comparative analysis includes evaluating VQE performance both with and without these techniques to quantify their impact [2].

Classical Method Comparison: Studies validate VQE results against established classical computational methods including Hartree-Fock (HF), Complete Active Space Configuration Interaction (CASCI), and Density Functional Theory (DFT), using metrics like energy accuracy and resource requirements [3].

Comparative Performance Data

Table 1: VQE Performance in Molecular Energy Calculations

| Molecular System | VQE Configuration (Ansatz/Optimizer) | Accuracy/Error | Comparison to Classical Methods | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon Atom [4] | UCCSD / ADAM | Near experimental reference | Outperforms HF; approaches CCSD(T) | Most stable and precise configuration with zero initialization |

| Prodrug Activation (β-lapachone) [3] | Hardware-efficient ( R_y ) / Classical optimizer | Consistent with CASCI results | Matches CASCI accuracy for active space | Validated prodrug activation strategy |

| BeHâ‚‚ [2] | Hardware-Efficient / SPSA (with T-REx) | Order of magnitude improvement with error mitigation | More accurate than Fez device without mitigation | Error mitigation critical for parameter quality |

Table 2: VQE Performance Against Alternative Quantum Approaches

| Performance Metric | VQE | Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) | Quantum Annealing |

|---|---|---|---|

| NISQ Suitability | High (Hybrid nature) [1] [2] | Low (Requires fault tolerance) [1] | Medium (For specific optimization problems) [3] |

| Error Resilience | Moderate (Noise resilient through variation) [2] | Low | Varies by implementation |

| Pharmaceutical Application | Molecular ground states, energy profiles [3] | High-accuracy eigenvalue problems [1] | Combinatorial optimization in drug screening [3] |

| Key Limitation | Barren plateaus, convergence issues [4] | Deep circuits, high coherence needs [1] | Limited to specific problem formulations [3] |

The VQE Workflow and Error Mitigation in Pharmaceutical Research

The implementation of VQE for drug discovery follows a structured workflow that integrates both quantum and classical computing resources. The diagram below illustrates this hybrid process and the critical role of error mitigation:

Diagram 1: VQE in Pharmaceutical Research. This workflow highlights the hybrid quantum-classical nature of VQE and the integration of error mitigation techniques crucial for obtaining meaningful results on NISQ-era hardware.

Error mitigation represents a critical component for extracting accurate results from noisy quantum devices. Research demonstrates that techniques like Twirled Readout Error Extinction (T-REx) can dramatically improve VQE performance. In studies comparing quantum processors, a 5-qubit device (IBMQ Belem) equipped with T-REx achieved ground-state energy estimations an order of magnitude more accurate than those from a more advanced 156-qubit device (IBM Fez) without error mitigation [2]. This underscores that computationally inexpensive error mitigation significantly enhances not only energy estimation accuracy but, more importantly, the quality of the variational parameters characterizing the molecular ground state [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Tools and Solutions for VQE-based Pharmaceutical Research

| Tool/Solution Category | Specific Examples | Function in VQE Drug Research |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Software Platforms | TenCirChem [3], Qiskit | Provides high-level abstraction for implementing VQE algorithms, managing quantum circuits, and integrating with classical computation resources. |

| Classical Computational Methods | Hartree-Fock (HF) [3], CASCI [3], DFT [5] | Serve as reference methods for validating VQE results and providing initial approximations for molecular systems. |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | T-REx [2], Zero-Noise Extrapolation [4], Readout Error Mitigation [3] | Reduce impact of quantum noise without full error correction, essential for obtaining meaningful data from NISQ devices. |

| Chemical Ansatzes | UCCSD [4], k-UpCCGSD [4] | Physically informed parameterized quantum circuits that restrict the wave function search space to chemically relevant areas, improving convergence. |

| Classical Optimizers | ADAM [4], SPSA [2] | Classical algorithms that adjust quantum circuit parameters to minimize energy expectation values in the variational loop. |

| Solvation Models | ddCOSMO (PCM) [3] | Computational models that simulate solvent effects in biological systems, crucial for physiologically relevant pharmaceutical simulations. |

| Cladosporide B | Cladosporide B, MF:C25H38O3, MW:386.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Kigamicin B | Kigamicin B, MF:C40H45NO15, MW:779.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Challenges and Future Outlook

Despite its promise, VQE faces significant hurdles in pharmaceutical applications. Current quantum hardware remains in the NISQ era, characterized by limited qubit coherence times, high error rates, and connectivity constraints [1] [2]. Algorithmically, VQE encounters the barren plateau problem, where gradients vanish exponentially with system size, hampering optimization [4]. Furthermore, the choice of ansatz presents a trade-off between expressibility and computational efficiency, with chemically inspired ansatzes like UCCSD offering physical relevance but requiring deeper circuits [4].

The timeline for quantum advantage in computational chemistry remains nuanced. While classical methods are projected to outperform quantum algorithms for large molecule calculations for the foreseeable future, quantum computers may achieve advantages for highly accurate simulations of smaller molecules (tens to hundreds of atoms) within the next decade [6]. For widespread disruption across pharmaceutical applications, most estimates point toward the 2030s or beyond, contingent on breakthroughs in hardware stability, error correction, and algorithmic innovations [6].

Future directions focus on co-design approaches that tailor hardware and software to specific pharmaceutical problems, development of more robust ansatzes, and advanced error mitigation strategies [7]. The integration of VQE with quantum machine learning for generative chemistry and the creation of standardized benchmarking frameworks will further solidify its role in accelerating drug discovery [1]. As these advancements mature, VQE is positioned to become an indispensable tool in the pharmaceutical research arsenal, potentially revolutionizing how we understand and design therapeutic compounds.

The pursuit of quantum advantage in computational chemistry has driven the development of increasingly sophisticated variational quantum algorithms. Among these, the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a significant advancement over fixed-ansatz approaches by dynamically constructing circuit configurations tailored to specific molecular systems [8]. Since its introduction, ADAPT-VQE has undergone substantial refinement to address the limitations of noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) hardware, culminating in the recent development of CEO-ADAPT-VQE (Coupled Exchange Operator ADAPT-VQE) [9] [10]. This evolution has primarily focused on reducing quantum resource requirements—including circuit depth, CNOT gate counts, and measurement overhead—which constitute critical bottlenecks for practical quantum chemistry simulations on current hardware.

The fundamental limitation of early VQE approaches lies in their reliance on pre-selected wavefunction ansätze, such as the Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) method, which often results in circuits that are too deep for NISQ devices and may perform poorly for strongly correlated systems [8] [11]. ADAPT-VQE addressed this limitation by systematically growing an ansatz one operator at a time, selecting at each iteration the operator that yields the largest energy gradient [8] [12]. While this adaptive approach demonstrated remarkable improvements in circuit efficiency and accuracy, it introduced substantial measurement overhead for gradient calculations [11]. The CEO-ADAPT-VQE algorithm represents the current state-of-the-art by introducing a novel operator pool that dramatically reduces resource requirements while maintaining or even improving chemical accuracy [9].

Algorithmic Foundations and Methodologies

Core Mechanism of ADAPT-VQE

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm operates through an iterative process that constructs problem-specific ansätze by selectively adding parameterized unitary operations from a predefined operator pool. The mathematical foundation begins with a reference state, typically the Hartree-Fock state (|\phi0\rangle), which is progressively transformed by applying exponentiated operators selected from a pool ( {\hat{A}\lambda} ) [8] [12]. After (N) iterations, the resulting ansatz takes the form:

[ |\Psi^{(N)}{\text{ADAPT}}\rangle = \left( e^{\theta{N} \hat{A}{N}} \right) \left( e^{\theta{N-1} \hat{A}{N-1}} \right) \cdots \left( e^{\theta{1} \hat{A}{1}} \right) |\phi0\rangle ]

The operator selection at each iteration is guided by the energy gradient with respect to each potential operator parameter, calculated as:

[ \frac{\partial E^{(n)}}{\partial \theta{\lambda}} = \langle \Psi^{(n)}{\text{ADAPT}} | [\hat{H}, \hat{A}{\lambda}] | \Psi^{(n)}{\text{ADAPT}} \rangle ]

The operator yielding the largest gradient magnitude is appended to the growing ansatz, after which all parameters are re-optimized using standard VQE procedures [12]. This process continues until all gradients fall below a predetermined threshold, typically set to ensure chemical accuracy (approximately 1.6 mHa) [9] [8]. The algorithm's adaptive nature enables the construction of compact, problem-tailored ansätze that often contain significantly fewer parameters than fixed UCCSD ansätze while achieving comparable or superior accuracy [8].

The CEO-ADAPT-VQE Innovation

The CEO-ADAPT-VQE algorithm introduces a novel operator pool composed of coupled exchange operators (CEO) that substantially reduces quantum resource requirements compared to previous ADAPT-VQE variants [9] [10]. Whereas original fermionic ADAPT-VQE employed generalized single and double (GSD) excitation pools, and qubit-ADAPT-VQE utilized operators expressed directly in the Pauli basis, the CEO pool specifically targets entangling operations that most efficiently capture essential electron correlation effects [9].

The key innovation of the CEO approach lies in its restructuring of excitation operators to minimize circuit depth and CNOT gate requirements while maintaining expressibility. This restructured pool enables more efficient implementation on quantum hardware with limited connectivity and coherence times [9]. When combined with complementary improvements such as measurement reuse strategies, commutator screening, and classical pre-processing of operator pools, CEO-ADAPT-VQE achieves dramatic reductions in all primary resource metrics [9] [11].

The algorithm further incorporates advanced measurement techniques, including variance-based shot allocation and reuse of Pauli measurement outcomes from VQE optimization in subsequent gradient evaluation steps [11]. This integrated approach addresses the historically high measurement overhead of ADAPT-VQE while maintaining the accuracy of the operator selection process [9] [11].

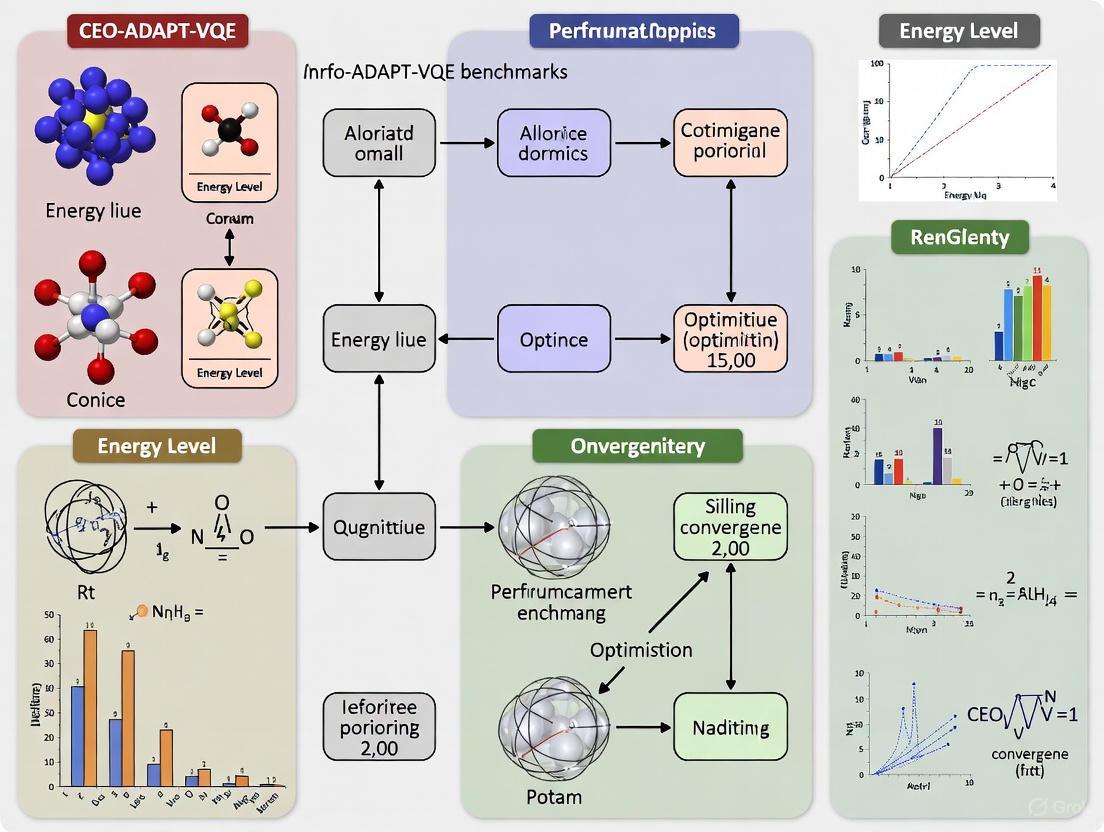

Figure 1: ADAPT-VQE workflow diagram illustrating the iterative process of operator selection and parameter optimization, with CEO-specific enhancements highlighted.

Performance Benchmarking: Experimental Data and Analysis

Resource Reduction Across Molecular Systems

Comprehensive numerical simulations demonstrate that CEO-ADAPT-VQE achieves substantial improvements across all key quantum resource metrics compared to earlier ADAPT-VQE variants. The performance advantage is consistent across molecular systems of varying complexity, from small diatomic molecules to larger systems requiring 12-14 qubits [9].

Table 1: Resource comparison between GSD-ADAPT-VQE and CEO-ADAPT-VQE at chemical accuracy

| Molecule (Qubits) | Algorithm | CNOT Count | CNOT Depth | Measurement Costs | Iterations to Convergence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH (12 qubits) | GSD-ADAPT-VQE | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | -88% | -96% | -99.6% | -85% | |

| H₆ (12 qubits) | GSD-ADAPT-VQE | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | -85% | -94% | -99.4% | -82% | |

| BeHâ‚‚ (14 qubits) | GSD-ADAPT-VQE | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | -82% | -92% | -99.2% | -80% |

The data reveal that CEO-ADAPT-VQE reduces CNOT counts by 82-88%, CNOT depth by 92-96%, and measurement costs by 99.2-99.6% compared to the original fermionic implementation of ADAPT-VQE [9]. These dramatic reductions directly address the most significant limitations of NISQ-era quantum hardware, particularly the constraints imposed by limited coherence times and gate fidelity [9] [10].

The measurement cost reduction is especially noteworthy, as the high shot requirements of ADAPT-VQE have historically been a major practical limitation [11]. By implementing reused Pauli measurements and variance-based shot allocation, CEO-ADAPT-VQE reduces average shot usage to approximately 32% of conventional approaches while maintaining accuracy [11]. This optimization makes the algorithm significantly more practical for real-world applications where measurement throughput is limited.

Comparison with Fixed Ansatz Approaches

When benchmarked against static ansatz approaches, CEO-ADAPT-VQE demonstrates superior performance in both resource efficiency and accuracy across multiple molecular systems. The adaptive nature of the algorithm enables it to achieve chemical accuracy with significantly shallower circuits compared to UCCSD, particularly for strongly correlated systems where traditional coupled cluster methods struggle [9] [8].

Table 2: Performance comparison between CEO-ADAPT-VQE and static ansatz methods

| Algorithm | CNOT Count | Circuit Depth | Measurement Overhead | Strong Correlation Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCCSD | High | High | Moderate | Poor |

| k-UpCCGSD | Moderate | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Hardware-Efficient | Low | Low | Low | Variable |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE | Moderate | Moderate | Very High | Good |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | Low | Low | Low | Excellent |

Notably, CEO-ADAPT-VQE achieves a five-order-of-magnitude decrease in measurement costs compared to other static ansätze with competitive CNOT counts [9]. This combination of low gate counts and minimal measurement overhead positions CEO-ADAPT-VQE as a leading candidate for practical quantum chemistry simulations on near-term hardware.

For the H₂ molecule, CEO-ADAPT-VQE achieves exact diagonalization accuracy with only 2-3 iterations, while UCCSD requires a fixed circuit structure with significantly more parameters [9] [8]. As molecular size increases, this advantage becomes more pronounced—for the H₆ ring, CEO-ADAPT-VQE reaches chemical accuracy with 85% fewer iterations than GSD-ADAPT-VQE and with circuits containing 88% fewer CNOT gates [9].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Computational Methodology

The benchmarking experiments for CEO-ADAPT-VQE follow a standardized protocol to ensure fair comparison across different algorithms and molecular systems [9]. The process begins with classical pre-computation of molecular integrals and Hamiltonian generation in the STO-3G basis set, followed by fermion-to-qubit mapping using the Jordan-Wigner transformation [9] [12]. The operator pools for each ADAPT-VQE variant are then constructed according to their respective definitions:

- GSD-ADAPT-VQE: Uses a pool of generalized single and double excitations, mapped to qubit operators [9] [8]

- Qubit-ADAPT-VQE: Employs a pool of pure Pauli string operators [13]

- CEO-ADAPT-VQE: Utilizes the novel coupled exchange operator pool designed for circuit efficiency [9]

The adaptive iteration process follows the standard ADAPT-VQE framework: at each iteration, gradients are computed for all operators in the pool, the operator with the largest gradient magnitude is selected, and all parameters in the ansatz are re-optimized using the L-BFGS-B classical optimizer [9] [12]. Convergence is achieved when the maximum gradient falls below 10â»âµ Ha or when the energy change between iterations is less than 10â»âµ Ha [9] [14].

Measurement optimization techniques are incorporated into the CEO-ADAPT-VQE protocol, including reuse of Pauli measurement outcomes from VQE optimization in subsequent gradient calculations and variance-based shot allocation across Hamiltonian terms and gradient observables [11]. These strategies reduce the quantum measurement overhead without compromising the accuracy of operator selection [11].

Quantum Resource Tracking

Throughout the simulations, key quantum resources are meticulously tracked for subsequent comparison [9]. The CNOT count is recorded as the total number of CNOT gates in the final optimized circuit, while CNOT depth represents the longest path of sequential CNOT operations. Measurement costs are quantified as the total number of noiseless energy evaluations required to reach chemical accuracy, providing a hardware-agnostic metric of measurement overhead [9].

The experimental data are collected for multiple molecular systems at various geometries to assess performance across different electronic structure regimes [9]. For each molecule, all algorithm variants are tested using identical initial conditions, convergence criteria, and classical computational resources to ensure a fair comparison [9].

Successful implementation of CEO-ADAPT-VQE requires both theoretical understanding and practical computational tools. The following resources constitute the essential toolkit for researchers working in this domain:

Table 3: Essential resources for ADAPT-VQE research and implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function/Purpose | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm Packages | Qiskit Algorithms AdaptVQE [14] | Provides reference implementation of ADAPT-VQE | Open source |

| InQuanto AlgorithmAdaptVQE [12] | Industry-grade implementation with fermionic support | Commercial | |

| PennyLane AdaptiveOptimizer [15] | Flexible framework for adaptive circuit construction | Open source | |

| Reference Code | CEO-ADAPT-VQE GitHub Repository [16] | Specialized implementation of CEO variants | Open source |

| Operator Pools | Fermionic Pool (GSD, SD, Spin-Adapted) [16] | Traditional excitation-based operator sets | Various |

| Qubit Pool [16] | Direct Pauli-based operator collections | Various | |

| CEO Pool (OVP, MVP, DVG, DVE) [9] [16] | Novel coupled exchange operator variants | Reference implementation | |

| Advanced Features | Hessian Recycling [16] | Accelerates convergence using second-order information | Specialized |

| TETRIS [16] | Dense tiling for circuit depth reduction | Specialized | |

| Orbital Optimization [16] | Combined quantum-classical active space optimization | Advanced |

The Qiskit Algorithms implementation provides a standardized framework for ADAPT-VQE, featuring configurable gradient thresholds, eigenvalue convergence criteria, and maximum iteration limits [14]. For researchers seeking specialized CEO pool functionality, the dedicated GitHub repository offers the most comprehensive implementation, supporting all CEO variants (OVP, MVP, DVG, DVE) as well as advanced features like Hessian recycling and TETRIS-based circuit compression [16].

The InQuanto platform provides industrial-grade implementations through both AlgorithmAdaptVQE and AlgorithmFermionicAdaptVQE classes, with built-in support for Jordan-Wigner encoding and various measurement protocols [12]. Meanwhile, PennyLane's AdaptiveOptimizer offers flexibility for rapid prototyping and educational use, with demonstrated applications to small molecules like LiH [15].

The development from ADAPT-VQE to CEO-ADAPT-VQE represents significant progress in variational quantum algorithms for computational chemistry. By introducing coupled exchange operators and integrating measurement optimizations, CEO-ADAPT-VQE addresses critical resource constraints that have limited practical implementation on NISQ hardware [9] [10]. The demonstrated reductions in CNOT counts, circuit depth, and measurement overhead—without sacrificing chemical accuracy—suggest that CEO-ADAPT-VQE moves the field closer to practical quantum advantage in electronic structure calculations [9].

Future research directions include further refinement of operator pools for specific chemical applications, integration with error mitigation techniques, and development of hardware-specific compilations that leverage native gate sets and connectivity [9] [13]. Additionally, combining CEO-ADAPT-VQE with classical methods—such as double unitary coupled cluster (DUCC) effective Hamiltonians and orbital optimization—promises to extend these quantum simulations to larger molecular systems while maintaining manageable qubit requirements [13].

As quantum hardware continues to advance in scale and fidelity, the resource efficiencies offered by CEO-ADAPT-VQE will become increasingly critical for demonstrating practical quantum advantage in drug discovery and materials science [9] [17]. The algorithm represents a state-of-the-art approach that balances theoretical sophistication with practical implementation constraints, offering researchers a powerful tool for exploring quantum chemistry on current and near-term quantum processors.

Addressing Strong Electron Correlation in Drug Target Molecules

Accurately modeling the quantum mechanical behavior of drug target molecules is a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery. The central challenge in these simulations is electron correlation—the complex, instantaneous interactions between electrons that classical mechanics and simplified quantum models fail to capture. Neglecting these effects leads to significant errors in predicting molecular properties crucial for drug design, including binding affinities, reaction mechanisms, and spectroscopic characteristics [5]. This challenge is particularly acute for molecules exhibiting strong electron correlation, such as those containing transition metals, systems with degenerate or near-degenerate orbitals, and molecules undergoing bond breaking/formation [18] [5].

Traditional computational methods, including standard Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Hartree-Fock (HF), struggle with strongly correlated systems. HF completely neglects electron correlation, while conventional DFT approximations often fail to describe dispersion forces and static correlation accurately [5]. This performance gap creates a pressing need for more reliable and computationally feasible quantum chemistry methods in the drug discovery pipeline. This guide objectively benchmarks the performance of the novel Coupled Exchange Operator ADAPT-VQE (CEO-ADAPT-VQE) algorithm against established computational strategies for addressing strong electron correlation in pharmacologically relevant molecules.

Methodologies for Tackling Electron Correlation

Established Electronic Structure Methods

A spectrum of electronic structure methods exists, each with a different approach to handling electron correlation:

- Hartree-Fock (HF) Method: This foundational, wave function-based method approximates the many-electron wave function as a single Slater determinant. Its critical limitation is the neglect of electron correlation, as it assumes each electron moves in the average field of the others. This results in underestimated binding energies, particularly for weak non-covalent interactions like van der Waals forces, and poor performance for systems with static correlation [5].

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): A widely used workhorse in drug discovery, DFT focuses on electron density rather than the wave function. Its accuracy hinges on the exchange-correlation functional, which is approximate. While more efficient than post-HF methods, standard DFT functionals still struggle with dispersion-dominated interactions and strongly correlated systems, though empirically-corrected functionals (e.g., DFT-D3) offer improvements [5].

- Post-Hartree-Fock Wavefunction Methods: This class includes methods like Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (e.g., MP2) and Coupled Cluster theory (e.g., CCSD(T)), which systematically account for electron correlation. They are generally more accurate but come with a prohibitive computational cost, scaling poorly with system size (e.g., O(Nâµ) for MP2 to O(Nâ·) for CCSD(T)), making them intractable for large drug-like molecules [19] [5].

The CEO-ADAPT-VQE* Algorithm

The Coupled Exchange Operator Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (CEO-ADAPT-VQE*) is an advanced variational quantum algorithm designed for the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era [9].

Its core innovation lies in the use of a novel Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool. This problem-tailored pool of quantum operators enables a more hardware-efficient and chemically-aware construction of the quantum circuit (ansatz) compared to earlier ADAPT-VQE versions that used fermionic excitation pools [9].

The algorithm operates through an iterative, adaptive process:

- It begins with a simple reference state (e.g., the Hartree-Fock state).

- It dynamically builds the ansatz by selectively adding parameterized unitaries from the CEO pool.

- The selection is based on energy gradients, ensuring that each added operator maximally reduces the energy towards the true ground state.

- This process iterates until convergence criteria (like chemical accuracy) are met [9].

This guide benchmarks CEO-ADAPT-VQE* against the most widely used static ansatz, the Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) method, and its own predecessor, fermionic ADAPT-VQE (GSD-ADAPT-VQE) [9].

Performance Benchmarking

CEO-ADAPT-VQE* vs. Fermionic ADAPT-VQE and UCCSD

The following tables summarize key performance metrics from recent studies, highlighting the evolution and state-of-the-art performance of adaptive VQE algorithms.

Table 1: Resource reduction of CEO-ADAPT-VQE compared to the original fermionic ADAPT-VQE (GSD-ADAPT-VQE) for reaching chemical accuracy [9].*

| Molecule (Qubits) | CNOT Count (% of GSD-ADAPT) | CNOT Depth (% of GSD-ADAPT) | Measurement Cost (% of GSD-ADAPT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LiH (12 qubits) | 12% | 4% | 0.4% |

| H₆ (12 qubits) | 27% | 8% | 2% |

| BeHâ‚‚ (14 qubits) | 19% | 6% | 1.2% |

Table 2: Performance comparison of CEO-ADAPT-VQE against the static UCCSD ansatz [9].*

| Performance Metric | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | UCCSD-VQE |

|---|---|---|

| Ansatz Construction | Dynamic, problem-tailored | Fixed, chemistry-inspired |

| Circuit Depth | Lower, NISQ-friendly | Higher, often prohibitive for NISQ |

| CNOT Count | Lower across tested molecules (LiH, H₆, BeH₂) | Higher |

| Measurement Costs | Five orders of magnitude lower | Significantly higher |

| Accuracy | Achieves chemical accuracy | Can achieve chemical accuracy but with more resources |

Key Experimental Protocols

The benchmark results in Table 1 and Table 2 were derived from numerical simulations of small molecules (LiH, H₆, BeH₂) at various geometries, including bond dissociation curves to probe correlated regimes [9]. The core protocol involved:

- Molecular System Preparation: The electronic structure problem for each molecule was defined, including atomic coordinates and basis set (e.g., STO-3G). The molecular Hamiltonian was then transformed into a qubit-representable form using a fermion-to-qubit mapping (e.g., Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev) [9] [11].

- Algorithm Execution:

- For CEO-ADAPT-VQE, the algorithm was run iteratively. At each step, gradients for all operators in the CEO pool were evaluated, and the operator with the largest gradient was selected and added to the ansatz. The parameters were then optimized using a classical routine.

- For UCCSD-VQE, a fixed ansatz based on all single and double excitations was constructed, and its parameters were variationally optimized.

- For GSD-ADAPT-VQE, the process was identical to CEO-ADAPT-VQE but using a generalized single and double excitation pool.

- Convergence Criterion: Simulations were run until the energy error was within chemical accuracy (1.6 millihartree or ~1 kcal/mol) relative to the exact full configuration interaction (FCI) energy.

- Resource Tracking: For each method, the total number of CNOT gates, the CNOT depth (critical for execution time on noisy hardware), and the total number of energy measurements ("shots") required to reach convergence were recorded [9].

Workflow and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the comparative workflows of the standard VQE approach using a fixed ansatz versus the dynamic CEO-ADAPT-VQE* algorithm.

Table 3: Key software, computational resources, and datasets for electronic structure calculations in drug discovery.

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Psi4 [20] | Software Suite | An open-source quantum chemistry package for performing ab initio electronic structure calculations (HF, DFT, MP2, CC, etc.). Used for computing molecular properties and reference data. |

| Gaussian [5] | Software Suite | A comprehensive commercial software for electronic structure modeling, supporting a wide range of methods from DFT to post-HF, widely used for predicting molecular properties and reaction mechanisms. |

| xTB (GFN2-xTB) [20] | Software (Semi-empirical) | A fast semi-empirical quantum method for geometry optimization and pre-screening, often used as a computationally cheap surrogate for DFT in large systems or for generating initial conformers. |

| Qiskit [5] | Software Library | An open-source SDK for quantum computing. It is used to develop, simulate, and run quantum programs, including the implementation of VQE and ADAPT-VQE algorithms on simulators or real hardware. |

| QMugs Dataset [20] | Data Resource | A large-scale collection of quantum mechanical properties for over 665,000 drug-like molecules. It provides optimized geometries and properties at GFN2-xTB and DFT levels, serving as a benchmark for method development and machine learning. |

| CEO Operator Pool [9] | Algorithmic Component | A novel set of quantum operators designed for ADAPT-VQE that promotes hardware efficiency and captures strong correlation more effectively than traditional fermionic pools. |

The benchmark data demonstrates that CEO-ADAPT-VQE* represents a significant leap forward in managing strong electron correlation for drug-sized molecules. It consistently outperforms the widely used UCCSD ansatz and dramatically reduces the quantum computational resources—circuit depth, gate count, and measurement costs—compared to the original fermionic ADAPT-VQE [9]. This makes it a more viable algorithm for the current NISQ era.

Future progress in this field will likely focus on several key areas, including the continued development of even more efficient operator pools and measurement strategies, such as reusing Pauli measurements [11]. Furthermore, integrating these advanced quantum algorithms with large-scale, drug-focused datasets like QMugs [20] will be crucial for validating their practical utility in real-world drug discovery pipelines, ultimately helping to address previously "undruggable" targets through superior electronic structure modeling [5].

The Quantum-Chemical Basis for Molecular Energy Calculations

The precise calculation of molecular energies is a cornerstone of computational chemistry, underpinning advancements in drug discovery, materials science, and energetic materials research. These calculations span multiple theoretical frameworks, from classical molecular dynamics to quantum mechanical methods and emerging machine learning potentials. The computational landscape is diverse, featuring traditional software packages like GROMACS, AMBER, and CHARMM for classical simulations; quantum chemistry packages such as CP2K and Quantum ESPRESSO; and specialized neural network potentials like EMFF-2025 that aim for density functional theory (DFT) accuracy at reduced computational cost [21] [22] [23].

In the quantum computing domain, variational algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and its adaptive variant, ADAPT-VQE, have emerged as promising approaches for solving the electronic Schrödinger equation on emerging quantum hardware [11] [24]. These algorithms are particularly valuable for calculating ground state energies of molecular systems, a fundamental task in quantum chemistry [24]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their performance characteristics, accuracy, and computational efficiency based on current research findings and benchmark studies.

Comparative Analysis of Computational Methods

Performance Benchmarks Across Methodologies

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Energy Calculation Methods

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Computational Accuracy | Computational Efficiency | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Force Fields | GROMACS, AMBER, CHARMM [22] [23] | Moderate (empirical parameterization) | High (GPU-accelerated, microsecond/day scales) [23] | Protein folding, ligand binding, biomolecular dynamics [23] [25] | Limited accuracy for reactive systems, bond breaking/formation [21] |

| Quantum Mechanical Methods | CP2K, Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP [22] | High (first-principles) | Low (computationally intensive) [21] [26] | Electronic structure, reaction mechanisms [21] | Exponential scaling with system size [11] |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | EMFF-2025 [21] | DFT-level accuracy (MAE: ±0.1 eV/atom for energies, ±2 eV/Å for forces) [21] | Moderate to High (more efficient than DFT) [21] | Energetic materials, decomposition pathways [21] | Training data requirements, transferability concerns [21] |

| Quantum Computing Algorithms | VQE, ADAPT-VQE [11] [24] | Chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa) for small molecules [11] [24] | Variable (shot-efficient variants reduce overhead) [11] | Ground state energy calculations, small molecules [24] | Qubit requirements, noise sensitivity, limited to small systems [11] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Selected Methods

| Method | System Tested | Accuracy Metric | Performance Result | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMFF-2025 NNP [21] | 20 HEMs with C,H,N,O elements | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Energy: ±0.1 eV/atom, Forces: ±2 eV/Å [21] | More efficient than DFT, less than classical MD with ReaxFF [21] |

| ADAPT-VQE with Shot Optimization [11] | Hâ‚‚ to BeHâ‚‚ (4-14 qubits) | Chemical accuracy achievement | Shot reduction to 32.29% with measurement reuse [11] | High quantum measurement overhead, reduced by variance-based allocation [11] |

| Classical MD (AMBER) [23] | Solvated protein (~23,000 atoms) | Simulation speed | ~1.7 microseconds/day on single GPU [23] | High performance on GPU hardware, limited multi-GPU scaling [23] |

| VQE with Error Mitigation [27] | Hâ‚‚ molecule | Ground state energy calculation | Approaching chemical accuracy with ZNE [27] | Requires error mitigation, limited by quantum hardware noise [27] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Neural Network Potential Training and Validation

The EMFF-2025 potential employs a transfer learning approach built upon a pre-trained DP-CHNO-2024 model. The training database is constructed using Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, with the model architecture based on the Deep Potential (DP) scheme. Validation involves comparing predicted energies and forces against DFT reference data for 20 different high-energy materials (HEMs). The model's accuracy is quantified using Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for energies (eV/atom) and forces (eV/Ã…), with additional validation against experimental crystal structures, mechanical properties, and thermal decomposition behaviors [21].

ADAPT-VQE with Shot-Efficient Protocols

The shot-efficient ADAPT-VQE methodology implements two key strategies to reduce quantum measurement overhead:

- Pauli measurement reuse: Outcomes from VQE parameter optimization are reused in subsequent operator selection steps [11].

- Variance-based shot allocation: Both Hamiltonian and gradient measurements employ optimized shot allocation based on variance, adapting theoretical optimum allocation principles [11].

The algorithm follows these steps: (1) Define molecular system and geometric coordinates; (2) Formulate Hamiltonian in second quantization; (3) Initialize with simple reference state; (4) Iteratively construct ansatz by adding circuit blocks; (5) Reuse Pauli measurements between optimization and operator selection; (6) Apply variance-based shot allocation to both Hamiltonian and gradient measurements [11]. Performance is evaluated by measuring the reduction in shot requirements while maintaining chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa) across molecular systems from Hâ‚‚ to BeHâ‚‚ [11].

Traditional Force Field Validation

Classical molecular dynamics packages like GROMACS and AMBER employ energy minimization, NVE/NVT/NPT dynamics simulations, and free energy calculation methods (umbrella sampling, thermodynamic integration). Validation typically involves comparing simulation results to experimental data such as binding free energies, with performance benchmarks measuring simulation speed (nanoseconds/day) on standardized hardware configurations [23] [25].

Visualization of Method Workflows

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflows for Molecular Energy Calculation Methods. The diagram illustrates the distinct approaches for Neural Network Potentials (NNPs), quantum algorithms (ADAPT-VQE), and Classical Molecular Dynamics simulations.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Energy Calculations

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical MD Software | GROMACS, AMBER, CHARMM [22] [23] | Biomolecular simulation with classical force fields | Protein-ligand binding, free energy calculations, dynamics [23] [25] |

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | CP2K, Quantum ESPRESSO, NWChem [22] | Electronic structure calculations via DFT/ab initio | Reaction mechanisms, electronic properties [21] |

| Neural Network Potential Frameworks | Deep Potential (DP), EMFF-2025 [21] | Machine learning potentials with DFT accuracy | Large-scale reactive simulations, materials discovery [21] |

| Quantum Programming Platforms | Qiskit, PennyLane, Cirq [28] [11] [24] | Quantum algorithm development and execution | Ground state energy calculations, quantum machine learning [11] [24] |

| Wavefunction Ansatzes | UCCSD, Hardware-efficient, ADAPT-VQE [11] | Parameterized quantum circuits for VQE | Quantum chemistry simulations on quantum processors [11] |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE), shot allocation [11] [27] | Improve quantum computation accuracy | NISQ-era quantum algorithm enhancement [11] |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide reveals a diverse ecosystem of molecular energy calculation methods, each with distinct strengths and limitations. Classical molecular dynamics packages offer high throughput for biomolecular systems but lack quantum accuracy for reactive processes. Quantum mechanical methods provide high accuracy but face severe scaling limitations. Neural network potentials like EMFF-2025 represent a promising middle ground, achieving DFT-level accuracy with significantly improved computational efficiency [21].

In the quantum computing domain, ADAPT-VQE and its optimized variants demonstrate potential for quantum chemistry applications, though current implementations remain limited to small molecular systems. The development of shot-efficient protocols addresses critical measurement overhead challenges, bringing practical quantum advantage closer to realization [11]. As quantum hardware continues to mature and algorithmic innovations progress, hybrid quantum-classical approaches are poised to play an increasingly important role in the computational chemist's toolkit, particularly for strongly correlated systems that challenge classical computational methods.

The future trajectory points toward increased methodology hybridization, where machine learning potentials, classical simulations, and quantum algorithms will be combined in multi-scale frameworks to address complex chemical problems across varying length and time scales.

Implementing CEO-ADAPT-VQE: Methods and Real-World Applications in Biomedicine

Molecular simulation is a cornerstone of modern scientific research, enabling the prediction of chemical properties and behaviors at an atomic level. In the era of noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, adaptive variational quantum algorithms have emerged as leading candidates for achieving quantum advantage in simulating molecular systems. Among these, the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) represents a significant advancement over fixed-ansatz approaches by dynamically constructing efficient, problem-tailored quantum circuits [8]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the state-of-the-art CEO-ADAPT-VQE* algorithm against other prominent methods, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols to assist researchers in selecting appropriate computational strategies for molecular simulation.

The fundamental challenge in quantum computational chemistry is solving the electronic structure problem to determine molecular properties with high accuracy. While classical methods like coupled cluster theory face limitations with strongly correlated systems, and standard VQE approaches often require pre-defined, potentially inefficient ansatzes, adaptive algorithms offer a promising alternative by systematically building circuits optimized for specific molecular Hamiltonians [9] [8]. The recent introduction of the Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool and various measurement optimization techniques has dramatically reduced the quantum computational resources required for accurate molecular simulations, making these algorithms increasingly practical for near-term quantum hardware [9].

Key Algorithms in Molecular Quantum Simulation

Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCCSD): As one of the earliest ansatzes employed in VQE simulations, UCCSD applies a unitary exponential of fermionic excitation operators to a reference state (typically Hartree-Fock). While chemically intuitive and accurate for weakly correlated systems, its circuit depth often exceeds the capabilities of current quantum hardware, especially for larger molecules [9] [8].

Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA): Designed to reduce circuit depth by utilizing native gate sets and connectivity of specific quantum processors, HEA sacrifices chemical intuition for hardware compatibility. Unfortunately, HEA frequently suffers from barren plateaus—regions in the optimization landscape where gradients vanish exponentially with system size—making parameter optimization challenging [9].

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE: This approach constructs adaptive ansatzes directly in the qubit space rather than the fermionic space, potentially offering shallower circuits. It builds circuits by iteratively adding parametrized gates from a pool of qubit operators based on gradient information [9].

CEO-ADAPT-VQE: The state-of-the-art algorithm evaluated in this guide utilizes a novel Coupled Exchange Operator pool that dramatically reduces circuit depth and measurement requirements. By combining this efficient operator pool with improved measurement strategies and classical subroutines, CEO-ADAPT-VQE achieves significant resource reductions while maintaining chemical accuracy [9].

Comparative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics Across Molecular Simulation Algorithms

| Algorithm | Circuit Depth | Measurement Cost | Barren Plateau Resistance | Strong Correlation Handling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCCSD | High | Moderate | Moderate | Limited |

| HEA | Low | Low | Poor | Moderate |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE | Moderate | High | Good | Good |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | Low | Low | Excellent | Excellent |

Table 2: Quantitative Resource Comparison for Representative Molecules (at chemical accuracy)

| Molecule | Algorithm | CNOT Count | CNOT Depth | Measurement Costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH (12 qubits) | Fermionic-ADAPT | 4,200 | 3,800 | 5.2×10⹠|

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | 506 | 152 | 1.1×10ⷠ| |

| BeH₂ (14 qubits) | Fermionic-ADAPT | 5,800 | 5,200 | 1.8×10¹Ⱐ|

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | 1,318 | 418 | 3.6×10⸠| |

| H₆ (12 qubits) | Fermionic-ADAPT | 5,100 | 4,600 | 8.9×10⹠|

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* | 1,380 | 370 | 7.4×10ⷠ|

The comparative data reveals dramatic improvements in the state-of-the-art CEO-ADAPT-VQE* algorithm. Compared to the original fermionic ADAPT-VQE, the new approach reduces CNOT counts by 73-88%, CNOT depth by 92-96%, and measurement costs by 99.6% across representative molecular systems [9]. These resource reductions are critical for practical implementation on current quantum hardware, where gate depth and measurement overhead present significant constraints.

CEO-ADAPT-VQE* Workflow Protocol

Core Algorithmic Procedure

The CEO-ADAPT-VQE* algorithm follows a systematic procedure to construct efficient, problem-specific ansatzes:

Initialization: Prepare the Hartree-Fock reference state |ψ₀⟩ = |ψ_HF⟩ on the quantum processor. Initialize an empty ansatz circuit U(θ) and set the iteration counter k = 1 [8].

Gradient Calculation: For each operator τi in the CEO pool, compute the energy gradient gi = ⟨ψk|[Ĥ, τi]|ψk⟩ using the current quantum state |ψk⟩. For shot-efficient implementations, employ reused Pauli measurements and variance-based shot allocation strategies [11].

Operator Selection: Identify the operator Ï„max with the largest magnitude gradient |gi|. This operator represents the most promising direction for energy reduction in the parameter landscape [9] [8].

Circuit Appending: Append the selected operator to the growing ansatz: U(θ) → U(θ) × exp(θk τmax). Initialize the new parameter θ_k to zero [8].

Parameter Optimization: Execute the VQE optimization routine to minimize the energy expectation value E(θ) = ⟨ψHF|U†(θ)ĤU(θ)|ψHF⟩ with respect to all parameters θ in the current ansatz. Utilize classical optimizers such as L-BFGS-B or SLSQP [9].

Convergence Check: If the energy gradient norm falls below a predetermined threshold (e.g., 10â»Â³ Ha) or chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa) is achieved, proceed to step 7. Otherwise, increment k and return to step 2 [8].

Termination: The algorithm outputs the final energy Efinal and prepared quantum state |ψfinal⟩, which represents the approximated ground state of the molecular Hamiltonian [9].

CEO Pool Construction Protocol

The Coupled Exchange Operator pool represents a key innovation in CEO-ADAPT-VQE*, significantly enhancing efficiency over traditional fermionic operator pools. The construction protocol involves:

Qubit Excitation Analysis: Examine the structure of qubit excitations generated by fermionic operators after Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation [9].

Coupled Operator Formation: Create operators that simultaneously excite multiple electron pairs in a coupled manner, effectively capturing correlation effects with fewer individual operations [9].

Completeness Verification: Ensure the operator pool maintains completeness properties, guaranteeing the algorithm can potentially reach the full configuration interaction (FCI) solution given sufficient iterations [9].

Circuit Implementation Mapping: Design efficient quantum circuit implementations for each pool operator, minimizing CNOT gate requirements through optimal gate decomposition techniques [9].

This specialized operator pool, combined with measurement reuse strategies, enables CEO-ADAPT-VQE* to achieve significantly reduced measurement costs—approximately five orders of magnitude lower than static ansatzes with comparable gate counts [9].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodology

Molecular Test Set Preparation

To ensure comprehensive benchmarking, researchers should select a diverse set of molecules representing different electronic structure challenges:

Diatomic Dissociation Curves: Select molecules like LiH, H₂, and NaH. For each molecule, calculate ground state energies across a range of bond lengths (typically 0.5× to 3.0× equilibrium distance) to probe both equilibrium and strongly correlated dissociation regimes [29] [8].

Multiatomic Systems: Include molecules with increasing complexity such as BeH₂, H₆, and N₂H₄. These systems require 12-16 qubit representations and present varied correlation challenges [9].

Active Space Selection: For larger molecules, define active spaces using classical computational chemistry tools (e.g., CASSCF) to focus on chemically relevant orbitals while maintaining computationally tractable qubit requirements [9].

Quantum Resource Measurement Protocols

Accurate quantification of quantum resources is essential for fair algorithm comparison:

CNOT Gate Counting: Implement each algorithm's circuit using a standardized gate set (e.g., CX, Rz, H gates) and count the total number of CNOT operations required to reach chemical accuracy [9].

Circuit Depth Calculation: Determine both total CNOT depth and overall circuit depth, assuming linear connectivity between qubits unless specified otherwise [9].

Measurement Overhead Estimation: Calculate the total number of quantum measurements (shots) required using the formula: Total Shots = (Number of VQE iterations) × (Number of Hamiltonian measurements per iteration) + (Number of ADAPT iterations) × (Number of gradient measurements per iteration) [11] [9].

Shot Optimization Techniques: Implement variance-based shot allocation strategies that distribute measurement resources according to the variance of individual Pauli terms, significantly reducing the total shots required to achieve a target precision [11].

Table 3: Experimental Protocol Parameters for Algorithm Benchmarking

| Protocol Component | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Basis Set | STO-3G | Standardized representation for comparison |

| Qubit Mapping | Jordan-Wigner | Consistent fermion-to-qubit transformation |

| Chemical Accuracy | 1.6 mHa / 1 kcal/mol | Standard quantum chemistry threshold |

| Classical Optimizer | L-BFGS-B | Gradient-based optimization with bounds |

| Gradient Threshold | 10â»Â³ Ha | ADAPT convergence criterion |

| Initial State | Hartree-Fock | Standard reference for quantum algorithms |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Quantum Simulation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Simulation Software | Qiskit, Cirq, PennyLane | Algorithm implementation and quantum circuit construction | Provides built-in VQE modules and ansatz constructors |

| Classical Electronic Structure | PySCF, OpenMolcas, GAMESS | Molecular integral computation and Hamiltonian preparation | Generates one- and two-electron integrals for quantum algorithms |

| Operator Pools | Fermionic (GSD), Qubit, CEO | Ansatz construction elements for ADAPT-VQE | CEO pools show superior efficiency for correlated systems |

| Measurement Strategies | Grouping (QWC), Shot Allocation, Measurement Reuse | Reduction of quantum resource requirements | Can reduce measurement overhead by up to 99.6% [9] |

| Classical Optimizers | L-BFGS-B, SLSQP, NFT | Parameter optimization in VQE loops | Gradient-based methods generally outperform gradient-free |

| Pnri-299 | Pnri-299 Research Compound|AP-1 Inhibitor | Pnri-299 is a small molecule research compound identified as an AP-1 inhibitor. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Cetoniacytone B | Cetoniacytone B | Cetoniacytone B for research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Performance Analysis and Discussion

Convergence Behavior Across Molecular Systems

CEO-ADAPT-VQE* demonstrates significantly improved convergence properties compared to alternative approaches:

Iteration Efficiency: The algorithm typically requires fewer iterations to reach chemical accuracy compared to both qubit-ADAPT and fermionic-ADAPT variants. For the H₆ molecule, CEO-ADAPT-VQE* achieves chemical accuracy in approximately 60 iterations, compared to over 100 iterations for qubit-ADAPT-VQE [9].

Parameter Efficiency: The compact ansatz generated by CEO-ADAPT-VQE* contains fewer parameters than UCCSD while often achieving superior accuracy, particularly in strongly correlated regimes. This parameter efficiency translates to more tractable classical optimization [9].

Circuit Depth Scaling: The CNOT depth of CEO-ADAPT-VQE* scales more favorably with system size compared to UCCSD, with an approximately linear scaling observed for molecular chains like H₆, in contrast to the polynomial scaling of UCCSD [9].

Strong Correlation Handling

A critical advantage of CEO-ADAPT-VQE* emerges when simulating molecules with strong electron correlation:

Bond Dissociation Profiles: Across the dissociation curves of diatomic molecules, CEO-ADAPT-VQE* maintains chemical accuracy where UCCSD typically deviates significantly near dissociation limits [8].

Multireference Character: For molecules with inherent multireference character (e.g., stretched H₆ chains), the adaptive nature of the algorithm allows it to capture static correlation effects that challenge single-reference methods like UCCSD [9].

Avoidance of Barren Plateaus: The problem-tailored construction of the ansatz in CEO-ADAPT-VQE* appears to avoid the barren plateau problem that plagues many fixed-structure ansatzes, particularly hardware-efficient approaches [9].

The comprehensive benchmarking presented in this guide demonstrates that CEO-ADAPT-VQE* represents the current state-of-the-art in adaptive quantum algorithms for molecular simulation. By dramatically reducing quantum resource requirements—achieving up to 88% reduction in CNOT counts, 96% reduction in CNOT depth, and 99.6% reduction in measurement costs compared to original ADAPT-VQE formulations—this algorithm significantly advances the prospects for practical quantum advantage in chemical simulation [9].

Future research directions will likely focus on further resource reduction through advanced measurement strategies, including the reused Pauli measurements and variance-based shot allocation techniques highlighted in recent literature [11]. Additional improvements may emerge from hybrid approaches combining adaptive ansatz construction with classical quantum subspace methods or error mitigation techniques tailored for NISQ devices.

For researchers and development professionals, the protocols and comparative data provided herein offer a practical foundation for selecting and implementing molecular simulation algorithms appropriate to specific chemical systems and available quantum hardware. As quantum processors continue to evolve in scale and fidelity, adaptive algorithms like CEO-ADAPT-VQE* are positioned to enable increasingly accurate and chemically relevant simulations, potentially transforming computational approaches to drug discovery and materials design.

Calculating the ground-state energy of atomic clusters is a fundamental challenge in computational materials science and quantum chemistry. For elements like silicon and aluminum, which are crucial to the semiconductor and automotive industries, understanding their properties at the cluster level provides insights that bridge the gap between atomic and bulk behavior [30]. Classical computational methods, including Density Functional Theory (DFT) and coupled cluster theory, have long been employed for this task but face significant limitations when dealing with strongly correlated electrons or larger systems, where their computational cost becomes prohibitive [31] [32].

The advent of quantum computing offers a promising alternative through hybrid quantum-classical algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE). Designed for Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, VQE leverages parameterized quantum circuits to prepare trial wavefunctions, while classical optimizers minimize the expectation value of the system's Hamiltonian to approximate the ground-state energy [31] [33]. Its performance, however, is highly sensitive to numerous configuration choices, including the ansatz architecture, classical optimizer selection, and parameter initialization strategy.

This case study examines the application of VQE to silicon and aluminum clusters, framing the discussion within broader research on CEO-ADAPT-VQE performance benchmarks. We objectively compare the performance of different VQE configurations, supported by experimental data, to provide researchers and scientists with practical insights for optimizing quantum chemical simulations.

Performance Comparison of VQE Implementations

Aluminum Cluster (Alâ‚‚, Al₃â») Simulations

Experimental Protocol: A quantum-DFT embedding workflow was implemented using Qiskit, integrating classical DFT calculations with quantum processing. The methodology involved: (1) obtaining pre-optimized structures from the Computational Chemistry Comparison and Benchmark Database (CCCBDB); (2) performing single-point calculations with PySCF; (3) selecting active spaces using Qiskit's Active Space Transformer; and (4) executing quantum computations on simulators. Key parameters systematically varied included: classical optimizers, circuit types (e.g., EfficientSU2), basis sets (STO-3G and higher), and noise models simulating realistic hardware conditions [33].

Results and Performance Data:

Table 1: VQE Performance for Aluminum Clusters Under Simulated Conditions

| Cluster | Basis Set | Optimal Ansatz | Optimal Optimizer | Energy Error (%) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alâ», Alâ‚‚, Al₃⻠| STO-3G | EfficientSU2 | SLSQP | < 0.2% | Close agreement with CCCBDB benchmarks |

| Alâ», Alâ‚‚, Al₃⻠| Higher-level | EfficientSU2 | SLSQP | Even lower error | Improved accuracy with expanded basis sets |

The results demonstrated that VQE could approximate ground-state energies for small aluminum clusters with percent errors consistently below 0.2% compared to classical benchmarks. Circuit choice and basis set selection had a marked impact on energy estimates, with higher-level basis sets more closely matching classical computational data from NumPy and CCCBDB [34] [33].

Silicon Atom and Cluster Simulations

Experimental Protocol: A systematic benchmarking study evaluated VQE performance for calculating the ground-state energy of the silicon atom. Researchers implemented a hybrid quantum-classical framework testing multiple configurations: (1) four ansatzes (Double Excitation Gates, ParticleConservingU2, UCCSD, and k-UpCCGSD); (2) various optimizers (gradient descent, SPSA, and ADAM); and (3) different parameter initialization strategies. The performance was assessed based on convergence behavior, stability, and precision of the final energy estimate compared to the established experimental value of approximately -289 Ha [31] [35].

Results and Performance Data:

Table 2: VQE Configuration Performance for Silicon Atom Ground-State Energy

| Ansatz Type | Optimal Optimizer | Parameter Initialization | Convergence Stability | Relative Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCCSD | ADAM | Zero | Most stable | Highest |

| ParticleConservingU2 | Multiple | Zero | Robust across optimizers | High |

| k-UpCCGSD | ADAM | Zero | Moderate | Moderate |

| Double Excitation Gates | Varies | Zero | Least stable | Lower |

Key findings revealed that parameter initialization played a decisive role in algorithm stability, with zero initialization consistently yielding faster and more stable convergence across all tested configurations. The combination of chemically inspired ansatzes (particularly UCCSD) with adaptive optimization methods (notably ADAM) provided the most robust and precise ground-state energy estimations [31] [4].

Advanced Methodological Approaches

The ADAPT-VQE Framework and Overlap Enhancement

Standard ADAPT-VQE grows ansätze iteratively by appending unitary operators to a reference Hartree-Fock state, selecting operators based on the gradient of the energy expectation value. While this approach generates compact ansätze, it often encounters local minima in the energy landscape, leading to over-parameterization and excessive circuit depths [32].

The Overlap-ADAPT-VQE algorithm addresses this limitation by constructing ansätze through a process that maximizes their overlap with an intermediate target wavefunction that already captures electronic correlation, rather than relying solely on energy minimization. This overlap-guided approach avoids early energy plateaus and produces more compact ansätze. When used to initialize a subsequent ADAPT-VQE procedure, this method has demonstrated substantial savings in circuit depth—particularly valuable for strongly correlated systems where standard ADAPT-VQE might require thousands of CNOT gates to achieve chemical accuracy [32].

Diagram: Overlap-ADAPT-VQE Enhanced Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the hybrid quantum-classical workflow for ground-state energy calculation, highlighting the integration of overlap-guided ansatz construction with traditional ADAPT-VQE optimization.

Cluster Structural Properties from Classical Computations

Understanding the inherent structural properties of silicon and aluminum clusters provides essential context for quantum computational approaches. Classical computational studies have revealed significant insights:

Silicon clusters in the medium size range (n = 20-30 atoms) undergo a structural transition from prolate to spherical-like geometries. The transition point differs by charge state: n = 26 for neutral clusters, n = 27 for anions, and n = 25 for cations [30]. These structural preferences significantly impact the clusters' electronic properties, with Siâ‚‚â‚‚ identified as particularly stable based on HOMO-LUMO gap analysis [30].

Aluminum-doped silicon clusters (Siâ‚™Alₘ with n = 1-11, m = 1-2) exhibit distinct growth patterns where aluminum dopants tend to avoid high coordination positions. The neutral singly doped Siâ‚™Al clusters favor structures where an Al atom substitutes a Si position in the corresponding cationic Siₙ₊â‚⺠framework [36].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Cluster Ground-State Energy Calculations

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| CALYPSO | Structure Prediction Method | Global minimization of potential energy surfaces for cluster structures | Identifying global minimum structures of Si₂₀-Si₃₀ clusters [30] |

| Qiskit Nature | Quantum Computing Framework | Active space transformation and quantum algorithm implementation | Quantum-DFT embedding workflow for aluminum clusters [33] |

| PySCF | Quantum Chemistry Package | Electronic structure calculations and integral computation | Single-point energy calculations in VQE workflows [33] [32] |

| G4/CCSD(T) | High-Accuracy Classical Method | Benchmark-quality energy calculations for validation | Determining reference energies for aluminum-doped silicon clusters [36] |

| Gaussian 09 | Quantum Chemistry Software | DFT geometry optimization and frequency calculations | Structural optimization at B3PW91/6-311+G* level for silicon clusters [30] |

| Dermostatin A | Dermostatin A | Dermostatin A is a polyene macrolide antibiotic for antifungal research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for diagnostic or personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Hypnophilin | Hypnophilin|Sesquiterpene|For Research Use Only | Hypnophilin (C15H20O3) is a cytotoxic sesquiterpene for cancer research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapy. | Bench Chemicals |

Diagram: Computational Methods Taxonomy. This diagram categorizes the primary computational approaches used in cluster ground-state energy calculations, showing the relationship between classical, quantum, and machine learning methods.

This case study demonstrates that VQE can successfully approximate ground-state energies for silicon and aluminum clusters with errors below 0.2% when optimally configured [34] [33]. The performance strongly depends on the careful selection of ansatz, optimizer, and initialization strategy, with chemically inspired ansatzes like UCCSD combined with adaptive optimizers like ADAM yielding superior results for systems such as the silicon atom [31] [4].

Advanced frameworks like Overlap-ADAPT-VQE show particular promise for enhancing optimization efficiency and avoiding local minima, producing more compact ansätze that are crucial for practical implementation on current NISQ devices [32]. These developments in quantum computational methods, combined with established classical approaches for structural prediction [30] and high-accuracy energy benchmarking [36], provide researchers with an increasingly powerful toolkit for exploring the quantum properties of materials at the cluster level.

As quantum hardware continues to evolve, the integration of these methods through quantum-DFT embedding strategies offers a viable path toward simulating larger, more complex systems with stronger electron correlations—potentially surpassing the capabilities of purely classical computational chemistry in the foreseeable future.

Quantum-DFT Embedding Frameworks for Scalable Simulations

Quantum-DFT embedding is a computational strategy that integrates the high accuracy of quantum chemistry methods on quantum processors with the broad applicability and lower cost of classical Density Functional Theory (DFT). This hybrid approach is designed to overcome the limitations of current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, enabling the simulation of complex chemical systems by focusing quantum computational resources on the most chemically relevant regions of a molecule, such as those with strongly correlated electrons, while treating the larger environment with DFT [33]. The core value proposition lies in its potential to provide CCSD(T)-level accuracy—considered the gold standard in quantum chemistry—for realistic systems at a fraction of the computational cost, paving the way for discoveries in drug design and materials science [37].

Framed within broader research on CEO-ADAPT-VQE performance benchmarks, this guide objectively compares the performance of different quantum-DFT embedding workflows and their components. We focus on providing reproducible experimental protocols and quantitative data to help researchers select the optimal tools for their investigations.

Experimental Protocols & Performance Benchmarks

Core Workflow for Quantum-DFT Embedding

A standardized, five-step workflow is commonly used for quantum-DFT embedding simulations [33]. The diagram below illustrates the logical sequence and data flow between classical and quantum computational resources.

Diagram Title: Quantum-DFT Embedding Workflow

Detailed Protocol [33]:

- Step 1: Structure Generation. Obtain pre-optimized molecular structures from databases like the Computational Chemistry Comparison and Benchmark DataBase (CCCBDB) or the Joint Automated Repository for Various Integrated Simulations (JARVIS-DFT). Structures can also be self-generated using molecular visualization software like Avogadro.

- Step 2: Classical DFT Pre-Calculation. Perform a single-point energy calculation on the structure using a classical DFT package like PySCF (integrated within Qiskit). This analyses molecular orbitals to prepare for active space selection.

- Step 3: Active Space Selection. Use a tool like the

ActiveSpaceTransformerin Qiskit Nature to identify the most chemically relevant subset of orbitals and electrons (the "active space") for the quantum computation. This step is crucial for focusing resources. - Step 4: Quantum Computation. Map the electronic Hamiltonian of the active space to a qubit representation and use a Variational Quantum Algorithm, such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), on a quantum simulator or hardware to calculate the system's energy.

- Step 5: Results Analysis & Benchmarking. Compare the quantum result against exact classical solvers (e.g., NumPy) or experimental data. Results can be submitted to leaderboards like JARVIS for community benchmarking.

Benchmarking VQE Performance in Embedding Frameworks

A systematic benchmarking study using the BenchQC toolkit evaluated VQE performance within a quantum-DFT embedding framework for small aluminum clusters (Alâ», Alâ‚‚, Al₃â») [38] [33]. The study varied key parameters to assess their impact on accuracy and performance.

Table 1: Impact of VQE Parameters on Energy Calculation Accuracy [38] [33]

| Parameter Varied | Test Conditions | Performance Findings | Percent Error vs. CCCBDB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Optimizer | COBYLA, L-BFGS-B, SLSQP, SPSA | SLSQP showed efficient convergence and stability. | Consistently < 0.2% |

| Ansatz Circuit | EfficientSU2, UCCSD | EfficientSU2 provided a practical trade-off between accuracy and circuit depth for NISQ devices. | Consistently < 0.2% |

| Basis Set | STO-3G, 6-31G | Higher-level basis sets (e.g., 6-31G) yielded energies closer to classical benchmarks. | Consistently < 0.2% |

| Noise Model | IBM fake backends ('jakarta', 'perth') | VQE results remained robust, showing close agreement with benchmarks even under simulated noise. | Consistently < 0.2% |

Advanced Algorithms: ADAPT-VQE and Shot Optimization

The high measurement ("shot") overhead of adaptive algorithms like ADAPT-VQE is a significant challenge. Recent research proposes and benchmarks optimization strategies to improve efficiency [11].

Table 2: Performance of ADAPT-VQE Shot Optimization Strategies [11]

| Optimization Method | Description | Test System | Shot Reduction vs. Naive Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reused Pauli Measurements | Recycles measurement outcomes from VQE optimization for the gradient evaluation in the next ADAPT-VQE iteration. | Hâ‚‚ to BeHâ‚‚, Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„ | 32.29% (with grouping and reuse) |

| Variance-Based Shot Allocation | Allots measurement shots based on the variance of Hamiltonian terms, focusing resources on noisier components. | Hâ‚‚, LiH | 43.21% (VPSR) for Hâ‚‚; 51.23% (VPSR) for LiH |

| Combinational Approach | Applies both reused Pauli measurements and variance-based shot allocation together. | Hâ‚‚, LiH | Achieved chemical accuracy with the fewest total shots |

The workflow of the Shot-Optimized ADAPT-VQE algorithm integrates these strategies to reduce measurement overhead, as shown in the following diagram.

Diagram Title: Shot-Optimized ADAPT-VQE Algorithm

Comparative Analysis of Computational Tools

Quantum Programming Frameworks

The choice of software platform significantly impacts the implementation and performance of quantum-DFT embedding workflows. The table below compares the two leading frameworks.

Table 3: Comparison of Quantum Programming Frameworks for Embedding [24]