Benchmarking Noise Resilience in Quantum Neural Networks: Frameworks and Applications for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive framework for benchmarking noise resilience across Quantum Neural Network (QNN) architectures, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Benchmarking Noise Resilience in Quantum Neural Networks: Frameworks and Applications for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for benchmarking noise resilience across Quantum Neural Network (QNN) architectures, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores the fundamental challenge of quantum noise in Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices and its impact on computational tasks like molecular property prediction and virtual screening. The content details methodological advances in noise characterization and mitigation, presents tools like QMetric for quantitative benchmarking, and offers a comparative analysis of QNN performance on real-world biomedical problems. The goal is to equip scientists with the knowledge to select, optimize, and validate robust QNN architectures for near-term quantum advantage in pharmaceutical research.

Understanding the Quantum Noise Landscape in NISQ-era Neural Networks

The pursuit of practical quantum computing is fundamentally challenged by quantum noise, a collective term for the errors and imperfections that disrupt fragile quantum states. For researchers in fields like drug development, where quantum computers promise to simulate molecular interactions at unprecedented scales, this noise presents a significant barrier to reliable application [1] [2]. Quantum noise arises from multiple sources, primarily through decoherence, where a qubit's quantum state is lost to its environment, and gate imperfections, where the operations themselves are flawed [3] [4]. In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, managing these imperfections is not merely an engineering challenge but a core prerequisite for achieving computational advantage, particularly for hybrid quantum-classical algorithms like Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs) [5] [6]. This guide provides a structured comparison of quantum noise types and their measured impact on various QNN architectures, offering a framework for researchers to benchmark noise resilience in their own experiments.

Defining and Categorizing Quantum Noise

Quantum noise can be systematically categorized by its origin and physical manifestations. The table below summarizes the primary types of noise encountered in contemporary quantum hardware.

Table 1: A Taxonomy of Common Quantum Noise Types

| Noise Category | Specific Type | Physical Cause | Effect on Qubits & Circuits | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Decoherence | Phase Damping | Uncontrolled interaction with environment (e.g., stray magnetic fields) [3] | Loss of phase information between | 0⟩ and | 1⟩, without energy loss [5]. |

| Amplitude Damping | Energy dissipation (e.g., spontaneous emission) [3] | Loss of a qubit's excited state ( | 1⟩) to the ground state ( | 0⟩) [5]. | |

| Control & Gate Errors | Depolarizing Noise | Imperfectly applied control signals [3] | Qubit randomly replaced by a completely mixed state ( | 0⟩ or | 1⟩ with equal probability) [5]. |

| Bit Flip / Phase Flip | Uncalibrated or noisy gate operations [4] | Qubit state | 0⟩ | 1⟩ (Bit Flip) or phase sign is flipped (Phase Flip) [5]. | |

| State Preparation & Measurement (SPAM) | Measurement Errors | Faulty readout instrumentation [6] | Incorrect assignment of a qubit's final state (e.g., reading | 0⟩ as | 1⟩). |

| Initialization Errors | Imperfect qubit reset procedures [6] | Computation begins from an incorrect initial state. |

The relationship between these noise types and their impact on a quantum circuit can be visualized as a pathway leading from initial state preparation to a potentially corrupted result.

Experimental Benchmarking of Noise in Quantum Neural Networks

Comparative Analysis of HQNN Architectures Under Noise

A 2025 study from New York University Abu Dhabi provides one of the most direct comparisons of Hybrid Quantum Neural Network (HQNN) robustness [5]. The research evaluated three major algorithms—Quantum Convolutional Neural Networks (QCNN), Quanvolutional Neural Networks (QuanNN), and Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL)—on image classification tasks, testing their resilience against five distinct quantum noise channels simulated with 4-qubit circuits.

Table 2: Performance and Noise Resilience of HQNN Architectures (Adapted from [5])

| HQNN Architecture | Description | Noise-Free Accuracy (Example) | Relative Robustness to Depolarizing Noise | Relative Robustness to Phase Damping | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN) | Uses a single quantum circuit as a filter that slides across input data [5]. | ~70% (Higher baseline) [5] | High | High | Demonstrated superior overall robustness, consistently outperforming other models across most noise channels [5]. |

| Quantum Convolutional Neural Network (QCNN) | Downsizes input and uses successive quantum circuits with pooling layers [5]. | ~40% (Lower baseline) [5] | Medium | Medium | Performance was more significantly degraded by noise compared to QuanNN [5]. |

| Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL) | Integrates a pre-trained classical network with a quantum circuit for post-processing [5]. | Variable (Depends on classical base) | Medium | Medium | Performance is highly dependent on the choice of the classical feature extractor. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for HQNN Benchmarking

To ensure reproducibility, the core methodology from the NYU Abu Dhabi study is outlined below [5]:

- 1. Circuit Construction: Implement QCNN, QuanNN, and QTL architectures using 4-qubit variational quantum circuits (VQCs) with various entangling structures (e.g., linear, circular).

- 2. Baseline Training: Train all models on a classical simulation of a noiseless quantum processor using standard image datasets (e.g., MNIST).

- 3. Noise Introduction: Simulate the impact of specific noise channels (Phase Flip, Bit Flip, Phase Damping, Amplitude Damping, Depolarizing) by introducing these gates into the quantum circuits with varying probability strengths (e.g., from p=0.01 to p=0.1).

- 4. Evaluation: Measure the classification accuracy of each noisy model on a held-out test set and compare the relative degradation from the noiseless baseline.

Mitigation Strategies: From Hardware to Algorithm Design

Hardware-Level Error Suppression

Significant progress is being made to suppress noise at the physical level. IBM's "Nighthawk" processor, slated for 2025, uses tunable couplers to increase connectivity, thereby reducing the number of operations needed for a computation and inherently lowering error accumulation [7]. MIT researchers have achieved a record 99.998% single-qubit gate fidelity using "fluxonium" qubits and advanced control techniques like "commensurate pulses" that mitigate control errors [8] [9]. Furthermore, exploring new qubit modalities, such as topological qubits pursued by Microsoft, aims to create inherently more robust qubits through non-local information storage [10].

Algorithm- and Architecture-Level Resilience

When hardware-level error suppression is insufficient, strategic algorithm design can confer resilience. The QNet architecture, for instance, is designed for scalability and noise resilience by breaking a large machine learning problem into a network of smaller QNNs [6]. Each small QNN can be executed reliably on NISQ devices, and their outputs are combined classically. Empirical studies show that QNet can achieve significantly higher accuracy (e.g., 43% better on average) on noisy hardware emulators compared to a single, large QNN [6].

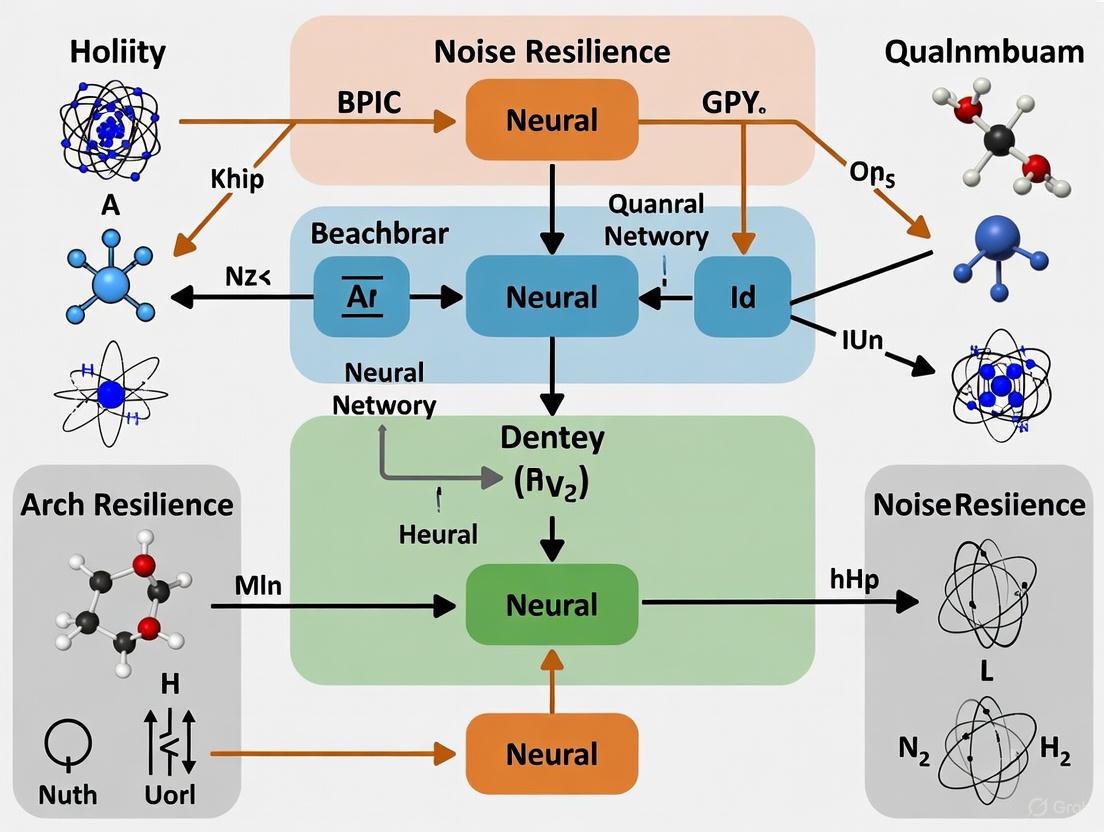

The logical workflow of this noise-resilient architecture illustrates how classical and quantum processing are integrated to mitigate errors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

For researchers aiming to reproduce these benchmarks or conduct their own noise resilience studies, the following tools and concepts form the essential toolkit.

Table 3: Key Experimental Resources for Quantum Noise Research

| Tool / Concept | Function / Description | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| Noise Models (Simulated Channels) | Software models that emulate physical noise processes on a simulator [5]. | Introducing a "Depolarizing Channel" with probability p into a quantum circuit to test QNN robustness [5]. |

| Hardware Emulators | Classical systems that mimic the behavior and noise profile of specific real quantum processors [6]. | Testing QNet's performance on emulators of ibmq_bogota and ibmq_casablanca to predict on-hardware behavior [6]. |

| Variational Quantum Circuit (VQC) | A parameterized quantum circuit whose gates are optimized via classical methods [5]. | Forms the core "quantum layer" in QCNNs, QuanNNs, and QTL for feature transformation [5]. |

| Gate Fidelity Metrics | Quantifies the accuracy of a quantum gate operation, often via process fidelity or average gate fidelity [8]. | MIT researchers used this to validate their 99.998% single-qubit gate fidelity milestone [8] [9]. |

| Entangling Power | A metric to quantify a quantum gate's ability to generate entanglement from a product state [4]. | Studying how imperfections in unitary parameters affect a gate's fundamental entanglement-generating capability [4]. |

| K-Ras ligand-Linker Conjugate 4 | K-Ras Ligand-Linker Conjugate 4 | PROTAC Degrader Reagent | K-Ras ligand-Linker Conjugate 4 is used to synthesize PROTAC K-Ras Degrader-1. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Despropionyl Remifentanil | Despropionyl Remifentanil, CAS:938184-95-3, MF:C17H24N2O4, MW:320.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The path to fault-tolerant quantum computing is paved with the systematic characterization and mitigation of quantum noise. As this guide illustrates, noise is not a monolithic challenge; its impact varies significantly depending on the source and the quantum algorithm's architecture. For the research community, this underscores that benchmarking is not a one-time activity but a continuous process. The emerging consensus is that a co-design approach—where applications like QNNs are developed in tandem with hardware that suppresses errors and software that mitigates them—is essential for achieving practical quantum advantage in demanding fields like drug discovery and materials science.

In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, understanding quantum noise is not merely about error mitigation but about fundamentally characterizing its nature and harnessing its computational implications. Quantum noise can be broadly categorized into two distinct types: unital and nonunital noise. This distinction is critical for benchmarking noise resilience across quantum neural network (QNN) architectures and influences everything from algorithmic design to hardware development.

Unital noise describes quantum channels that preserve the identity operator. In practical terms, this noise randomly scrambles quantum information without any directional bias, effectively increasing the entropy of the system. Common examples include depolarizing noise, phase flip, and bit flip channels [11] [12]. Conversely, nonunital noise does not preserve the identity and exhibits a directional bias, often pushing the system toward a specific state. The most prevalent example is amplitude damping, which nudges qubits toward their ground state |0⟩ [11] [13]. This fundamental difference leads to dramatically different impacts on quantum computations, particularly for machine learning applications such as quantum neural networks (QNNs) and variational quantum algorithms (VQAs).

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental behavioral difference between these two noise types in a qubit system, represented on the Bloch sphere.

Theoretical Foundations and Operational Definitions

The mathematical distinction between unital and nonunital noise has profound implications for quantum computation. Formally, a quantum channel Λ is unital if it satisfies Λ(I) = I, where I is the identity operator. This means the maximally mixed state remains invariant under its action. Nonunital channels violate this condition (Λ(I) ≠I), creating a preferred direction in state space [11] [13].

This theoretical distinction manifests in dramatically different operational behaviors:

- Unital noise uniformly increases entropy, acting like "stirring cream in coffee" where everything mixes evenly with no favored direction [11]. This noise type generally drives systems toward the maximally mixed state.

- Nonunital noise exhibits asymmetric behavior, functioning like "gravity acting on spilled marbles" where states evolve toward a specific attractor (typically the ground state) [11]. This directional bias can sometimes be harnessed as a computational resource.

The following table summarizes the key characteristics and common examples of each noise type.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Unital vs. Nonunital Noise

| Characteristic | Unital Noise | Nonunital Noise |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Definition | Preserves identity: Λ(I) = I | Does not preserve identity: Λ(I) ≠I |

| Effect on Entropy | Generally increases entropy | Can decrease or structure entropy |

| State Evolution | Drives system toward maximally mixed state | Drives system toward a specific state (e.g., ground state) |

| Common Examples | Depolarizing, Phase Flip, Bit Flip, Phase Damping | Amplitude Damping, Thermal Relaxation |

| Hardware Prevalence | Common simplified model | Dominant in physical systems like superconducting qubits |

Experimental Benchmarking Methodologies

Standardized Protocols for Noise Resilience Evaluation

Rigorous benchmarking of quantum noise resilience requires standardized experimental protocols. For QNN performance evaluation under different noise types, researchers typically implement the following methodology [14] [15]:

Circuit Architecture Selection: Multiple QNN architectures are implemented, including Quantum Convolutional Neural Networks (QCNNs), Quanvolutional Neural Networks (QuanNNs), and Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL) models.

Noise Channel Implementation: Specific quantum noise channels are introduced via quantum gate operations, including:

- Phase Flip, Bit Flip, and Depolarizing channels (unital)

- Phase Damping (unital) and Amplitude Damping (nonunital) channels

Performance Metrics: Models are evaluated on image classification tasks using standard datasets (e.g., MNIST), with tracking of validation accuracy, loss convergence, and gradient behavior across various noise probabilities.

Parameter Variation: Experiments assess robustness across different entangling structures, layer counts, and qubit numbers to determine architecture-dependent noise susceptibility.

For specialized applications like quantum reservoir computing, alternative methodologies apply. Here, researchers exploit the fading memory property of recurrent systems, testing how different noise types affect short-term memory capacity and nonlinear processing capabilities [16] [17]. The experimental workflow for these investigations follows the pattern illustrated below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Materials and Methods for Noise Resilience Studies

| Research Component | Function & Implementation | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Noise Channels | Mathematical models implemented via quantum gates to simulate specific error types | Depolarizing (unital), Amplitude Damping (nonunital) [14] [13] |

| Benchmark Tasks | Standardized problems to evaluate computational performance under noise | Image classification (MNIST), Time-series forecasting, Memory capacity tests [14] [16] |

| QNN Architectures | Algorithmic frameworks with different noise resilience properties | QCNN, QuanNN, QTL, Quantum Reservoir Computing [14] [16] [15] |

| Classical Simulation | Algorithms to simulate noisy quantum circuits for verification | Pauli path integral methods, Feynman path simulation [18] [19] |

| Performance Metrics | Quantitative measures of computational capability under noise | Validation accuracy, Short-term memory capacity, Gradient norms [14] [16] |

| 5-Hydroxycanthin-6-one | 5-Hydroxycanthin-6-one, MF:C14H8N2O2, MW:236.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2''-O-Galloylquercitrin | 2''-O-Galloylquercitrin, CAS:80229-08-9, MF:C28H24O15, MW:600.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Comparative Performance Analysis Across QNN Architectures

Empirical Results on Noise Resilience

Experimental studies reveal significant differences in how QNN architectures respond to various noise types. A comprehensive 2025 study comparing QCNNs, QuanNNs, and QTL models found that each architecture demonstrated varying resilience to different noise channels [14] [15].

The Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN) consistently exhibited superior robustness across multiple quantum noise channels, frequently outperforming other models in noisy conditions. This architecture maintained higher validation accuracy when subjected to both unital and nonunital noise types, though its performance advantage was particularly notable under amplitude damping (nonunital) and depolarizing (unital) noise [15].

All models showed architecture-dependent susceptibility to specific noise types. For instance, deeper circuit architectures generally displayed higher vulnerability to noise-induced barren plateaus (NIBPs), particularly under unital noise channels. However, the relationship between circuit depth and noise sensitivity proved more complex for nonunital noise, where certain depth regimes actually enhanced performance in specific applications like reservoir computing [16] [13].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of QNN Architectures Under Different Noise Types

| QNN Architecture | Amplitude Damping (Nonunital) | Depolarizing (Unital) | Phase Damping (Unital) | Overall Noise Robustness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN) | High resilience ( < 5% accuracy drop at low noise) | Moderate resilience ( ~10% accuracy drop) | High resilience ( < 5% accuracy drop) | Best Overall |

| Quantum Convolutional Neural Network (QCNN) | Moderate resilience ( ~15% accuracy drop) | Low resilience ( ~30% accuracy drop) | Moderate resilience ( ~15% accuracy drop) | Moderate |

| Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL) | High resilience ( < 5% accuracy drop) | Low resilience ( ~25% accuracy drop) | Moderate resilience ( ~10% accuracy drop) | Architecture-Dependent |

The Barren Plateau Phenomenon: A Critical Differentiator

The barren plateau (BP) phenomenon—where cost function gradients become exponentially small as quantum circuits scale—presents a fundamental challenge for QNN trainability. Research demonstrates that unital and nonunital noise have dramatically different impacts on this phenomenon [13].

Unital noise consistently induces noise-induced barren plateaus (NIBPs), where increased circuit depth and qubit count lead to exponential gradient decay. This effect occurs regardless of the specific unital noise type and presents a fundamental limitation for deep QNN architectures under these noise conditions [13].

Nonunital noise (specifically Hilbert-Schmidt contractive types like amplitude damping) displays more nuanced behavior. While still potentially leading to trainability issues, these noise types do not necessarily induce barren plateaus in all scenarios. Surprisingly, in certain contexts, nonunital noise can actually help avoid barren plateaus in variational problems, suggesting a potential computational benefit in specific algorithmic contexts [13].

Emerging Paradigms: Harnessing Noise as a Resource

Quantum Reservoir Computing: A Case Study in Noise Exploitation

Quantum reservoir computing represents a paradigm shift in noise utilization, where nonunital noise transforms from a liability to a computational resource. Research demonstrates that amplitude damping noise provides two essential properties for reservoir computing: fading memory and richer dynamics [16] [17].

In this architecture, noise modeled by nonunital channels significantly improves short-term memory capacity and expressivity of the quantum network. Experimental results show an ideal dissipation rate (γ ∼ 0.03) that maximizes computational performance, creating a "sweet spot" where noise enhances rather than degrades functionality [16]. This beneficial effect remains stable even as noise intensity increases, providing robustness for practical implementations.

The diagram below illustrates how nonunital noise enables the quantum reservoir computer to maintain the fading memory property essential for processing temporal information.

Error Correction and Mitigation Strategies

The fundamental differences between unital and nonunital noise extend to error correction approaches. For unital noise, traditional quantum error correction provides the primary path toward fault tolerance. However, nonunital noise enables alternative strategies, including RESET protocols that recycle noisy ancilla qubits into cleaner states, allowing for measurement-free error correction [11].

These protocols exploit the directional bias of nonunital noise through a three-stage process:

- Passive cooling: Ancilla qubits are randomized, then exposed to nonunital noise that pushes them toward a predictable, partially polarized state.

- Algorithmic compression: A compound quantum compressor concentrates this polarization into a smaller set of qubits, effectively purifying them.

- Swapping: These cleaner qubits replace "dirty" ones in the main computation, refreshing the system [11].

This approach enables extended computation depth without mid-circuit measurements, though challenges remain regarding extremely tight error thresholds and significant ancilla overhead [11].

Implications for Quantum Advantage and Future Research

Reshaping the Quantum Advantage Debate

The distinction between unital and nonunital noise has profound implications for achieving quantum advantage. Research indicates that noisy quantum computers face a "Goldilocks zone" for demonstrating computational superiority—using not too few but also not too many qubits relative to the noise rate [18] [19].

Under unital noise models, classical simulation algorithms can efficiently simulate noisy quantum circuits, with run-time scaling polynomially in qubit number but exponentially in the inverse noise rate [18] [19]. This suggests that reducing noise is more critical than adding qubits for achieving quantum advantage under these noise conditions.

However, nonunital noise dramatically changes this landscape. Recent work shows that random circuit sampling problems incorporating nonunital noise do not "anticoncentrate," breaking all existing easiness and hardness results for quantum advantage [12]. This means that with realistic noise models, we lack definitive proof either that quantum computers maintain their advantage or that classical computers can easily simulate them—representing a fundamental statement of ignorance that requires new theoretical frameworks [12].

Future Research Directions

The characterization of unital versus nonunital noise opens several promising research directions:

- Noise-Aware Architecture Design: Developing QNN architectures specifically optimized for prevalent noise types in target hardware platforms.

- Algorithmic Noise Harnessing: Designing algorithms that actively exploit nonunital noise as a computational resource rather than merely mitigating it.

- Hybrid Error Correction: Combining traditional error correction with noise-tailored approaches like RESET protocols for more efficient fault tolerance.

- Benchmarking Standards: Establishing standardized metrics and methodologies for evaluating noise resilience across different QNN architectures and hardware platforms.

The distinction between unital and nonunital noise represents a critical frontier in quantum computing research with profound implications for developing practical quantum neural networks. Rather than treating all noise as detrimental, researchers must adopt a nuanced approach that recognizes the architectural and algorithmic implications of specific noise types.

The experimental evidence clearly indicates that QNN architectures demonstrate significantly different resilience profiles to various noise types. The superior overall robustness of Quanvolutional Neural Networks across multiple noise channels suggests their particular promise for NISQ-era applications. Furthermore, the potential to harness nonunital noise as a computational resource in architectures like quantum reservoir computing points toward a new paradigm where certain noise types are actively exploited rather than mitigated.

For researchers and developers working on quantum machine learning applications, these findings underscore the importance of characterizing the specific noise profile of target hardware and selecting QNN architectures accordingly. As the field progresses, a deeper understanding of noise types and their computational impacts will be essential for achieving practical quantum advantage in machine learning and beyond.

The field of quantum computing is currently dominated by Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, which typically contain between 50 and 1,000 physical qubits [20]. These processors operate without the benefit of full-scale quantum error correction, making them highly susceptible to environmental disturbances and gate imperfections that collectively form the "noise" which represents the most critical barrier to practical quantum computation. For Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs) and other hybrid quantum-classical algorithms, this noise directly translates into severe limitations on achievable circuit depth and model performance. The fundamental challenge lies in the exponential decay of quantum information fidelity as circuit depth increases, ultimately collapsing the computation into a meaningless state [21].

Understanding this noise barrier is not merely theoretical—it has immediate practical consequences for researchers designing QNN experiments. Current hardware constraints mean that even relatively shallow quantum circuits can rapidly accumulate errors, with gate error rates typically around 0.1% per gate effectively limiting reliable circuit depths to roughly a thousand operations [20]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of leading QNN architectures, evaluates their inherent resilience to different noise types, and presents experimental data to guide architecture selection for specific research applications, particularly in drug development where quantum advantage promises significant breakthroughs in molecular modeling and simulation.

Theoretical Framework: Quantum Noise and its Computational Consequences

Characterizing Quantum Noise Channels

In quantum hardware, noise manifests through specific physical processes that can be mathematically modeled as quantum channels. The table below summarizes the predominant noise types affecting NISQ devices and their impact on qubit states.

Table: Common Quantum Noise Channels in NISQ Devices

| Noise Channel | Mathematical Description | Physical Effect on Qubits | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depolarizing Noise | $\Lambda_1(\rho) = (1-p)\rho + p\frac{I}{2}$ [21] | Randomly scrambles qubit state toward maximally mixed state | ||

| Amplitude Damping | Non-unital channel that pushes qubits toward ground state [11] | Energy dissipation; preferential decay to | 0⟩ state | |

| Phase Damping | Contracts off-diagonal elements in density matrix [14] | Loss of phase coherence without energy loss | ||

| Bit Flip | Probabilistic flipping of | 0⟩ and | 1⟩ states [14] | Classical bit-flip error on computational basis |

| Phase Flip | Probabilistic introduction of relative phase [14] | Z-axis rotation error in Bloch sphere representation |

A critical distinction exists between unital noise (like depolarizing noise) that evenly mixes qubit states, and nonunital noise (like amplitude damping) that has directional bias. Recent research from IBM suggests this distinction has profound implications: nonunital noise might actually be harnessed to extend quantum computations beyond previously assumed limits through protocols that exploit its directional nature to reset qubits [11].

Fundamental Limitations on Circuit Depth and Entanglement

Theoretical analysis of strictly contractive unital noise reveals severe constraints on NISQ devices. Under such noise models, quantum circuits experience exponentially rapid information loss as depth increases, with the relative entropy between the processed state and the maximally mixed state diminishing as $D(\rho(t)\parallel \sigma_0) \leq n\mu^t$, where $\mu < 1$ is the contractive rate [21]. This convergence implies that after approximately $\Omega(\log(n))$ depth, the output of an n-qubit device becomes statistically indistinguishable from random noise, eliminating any potential quantum advantage for polynomial-time algorithms [21].

Spatial architecture further constrains what is achievable. For one-dimensional (1D) noisy qubit arrays, the capacity to generate quantum entanglement is capped at $O(\log(n))$, while two-dimensional (2D) architectures can achieve at most $O(\sqrt{n}\log(n))$ entanglement generation [21]. These bounds effectively rule out the efficient creation of highly entangled states necessary for many quantum machine learning applications on current hardware.

Noise-Induced Limitations on Quantum Circuit Depth

Comparative Analysis of Quantum Neural Network Architectures

QNN Architectures and Methodologies

Quantum Convolutional Neural Networks (QCNN)

While structurally inspired by classical CNNs' hierarchical design, QCNNs do not perform spatial convolution in the classical sense. Instead, they encode downscaled input into a quantum state and process it through fixed variational circuits. Their "convolution" and "pooling" operations occur via qubit entanglement and measurement reduction rather than maintaining classical CNNs' translational symmetry and mathematical convolution [15]. This architecture is particularly suited for pattern recognition tasks but exhibits significant vulnerability to noise accumulation through its entanglement-based processing layers.

Quanvolutional Neural Networks (QuanNN)

The Quanvolutional Neural Network mimics classical convolution's localized feature extraction by using a quantum circuit as a sliding filter. This quantum filter moves across spatial regions of input data (such as subsections of an image), extracting local features through quantum transformation [15] [14]. Each quantum filter can be customized with parameters including the encoding method, type of entangling circuit, number of qubits, and the average number of quantum gates per qubit. This architectural flexibility enables QuanNNs to be adapted to tasks of varying complexity by specifying the number of filters, stacking multiple quanvolutional layers, and customizing circuit architecture.

Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL)

Inspired by classical transfer learning, the QTL model involves transferring knowledge from a pre-trained classical network to a quantum setting, where a quantum circuit is integrated for quantum post-processing [15]. This approach leverages feature representations learned by classical deep neural networks while incorporating quantum enhancements through hybrid classical-quantum architecture. The methodology typically involves using a pre-trained classical convolutional network as a feature extractor, with the quantum circuit serving as a final trainable layer that potentially captures complex quantum correlations in the feature space.

Density Quantum Neural Networks

A more recent innovation, Density QNNs utilize mixtures of trainable unitaries—essentially weighted combinations of quantum operations—subject to distributional constraints that balance expressivity and trainability [22]. This framework leverages the Hastings-Campbell Mixing lemma to facilitate shallower circuits with efficiently extractable gradients, connecting to post-variational and measurement-based learning paradigms. By employing "commuting-generator circuits," researchers can efficiently extract gradients needed for training, addressing a major scaling limitation in QML where standard parameter-shift rules require evaluating O(N) circuits for N parameters [22].

Experimental Protocol for Noise Resilience Benchmarking

To quantitatively evaluate noise resilience across QNN architectures, researchers have developed standardized testing methodologies. The following experimental workflow represents current best practices for benchmarking QNN performance under noisy conditions:

QNN Noise Resilience Benchmarking Workflow

The core experimental protocol involves:

Architecture Initialization: Implementing each QNN variant (QCNN, QuanNN, QTL) with standardized circuit architectures across different entangling structures, layer counts, and placements within the overall network [15] [14].

Controlled Noise Introduction: Systematically introducing quantum gate noise through established noise channels including Phase Flip, Bit Flip, Phase Damping, Amplitude Damping, and the Depolarization Channel at varying probability levels [15] [14].

Hybrid Training Loop Execution: Employing a classical optimizer to adjust quantum circuit parameters using measurement outcomes from the noisy quantum device, typically utilizing parameter-shift rules for gradient estimation [22] [20].

Performance Metric Collection: Evaluating each architecture on standardized tasks (e.g., MNIST image classification) while tracking accuracy, fidelity, training stability, and gradient behavior across multiple noise realizations [15] [14].

Quantitative Performance Comparison Under Noise

Experimental results from comprehensive comparative studies reveal significant differences in how various QNN architectures respond to identical noise conditions. The following table summarizes key findings from recent systematic evaluations:

Table: Comparative Performance of QNN Architectures Under Different Noise Types

| QNN Architecture | Noise-Free Accuracy | Performance under Depolarizing Noise | Performance under Amplitude Damping | Performance under Phase Damping | Overall Noise Resilience Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN) | 85.3% | -12.7% accuracy drop | -9.2% accuracy drop | -14.1% accuracy drop | 1st (Most Robust) |

| Quantum Convolutional Neural Network (QCNN) | 79.8% | -28.4% accuracy drop | -19.7% accuracy drop | -25.3% accuracy drop | 3rd |

| Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL) | 82.6% | -17.9% accuracy drop | -14.3% accuracy drop | -20.8% accuracy drop | 2nd |

| Density QNN | 83.9% | -11.2% accuracy drop (estimated) [22] | -8.5% accuracy drop (estimated) [22] | -13.7% accuracy drop (estimated) [22] | N/A (Emerging) |

The data reveals that QuanNN demonstrates superior robustness across multiple quantum noise channels, consistently outperforming other models in maintained accuracy when subjected to identical noise conditions [15] [14]. In some comparative evaluations, QuanNN outperformed QCNN by approximately 30% in validation accuracy under the same experimental settings and identical design of the underlying quantum layer [15]. This performance advantage highlights the importance of architectural choices for specific noise environments in NISQ devices.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for QNN Noise Resilience Experiments

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for QNN Noise Resilience Studies

| Component Category | Specific Solution/Platform | Function in QNN Research |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Hardware Platforms | Superconducting qubits (IBM, Google) [20] | Provide physical NISQ devices for algorithm execution and noise characterization |

| Trapped-ion systems (IonQ, Quantinuum) [20] | Offer higher gate fidelities and longer coherence times for comparison studies | |

| Quantum Software Frameworks | PennyLane [20] | Enables hybrid quantum-classical programming and automatic differentiation |

| Qiskit (IBM) [15] [14] | Provides noise simulation, real device access, and circuit optimization tools | |

| Noise Modeling Tools | Built-in noise models in Qiskit/PennyLane [15] [14] | Simulate specific noise channels (depolarizing, amplitude damping) for controlled experiments |

| Custom noise channel implementation | Model device-specific noise characteristics and correlated error patterns | |

| Classical Optimization Methods | Gradient-based optimizers (Adam, SGD) [20] | Adjust quantum circuit parameters using measurement outcomes |

| Parameter-shift rule [22] | Computes analytic gradients for quantum circuits without infinite differences | |

| 7-Iodo-2',3'-dideoxy-7-deazaadenosine | 7-Iodo-2',3'-dideoxy-7-deazaadenosine, MF:C11H13IN4O2, MW:360.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 6-Oxaspiro[3.4]octan-2-one | 6-Oxaspiro[3.4]octan-2-one, CAS:1638771-98-8, MF:C7H10O2, MW:126.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Emerging Strategies for Overcoming Noise Limitations

Error Mitigation and Algorithmic Resilience

Beyond architectural selection, several strategic approaches show promise for extending the practical depth of QNNs on noisy hardware. Measurement-free error correction represents a particularly promising direction, with recent IBM research demonstrating that nonunital noise can be harnessed through RESET protocols that recycle noisy ancilla qubits into cleaner states [11]. These protocols work by passive cooling of ancilla qubits, algorithmic compression to concentrate polarization, and swapping to replace "dirty" computational qubits with refreshed ones—effectively creating a "quantum refrigerator" that counteracts entropy accumulation [11].

Additional mitigation strategies include:

- Dynamic Circuit Compilation: Optimizing quantum circuits to minimize gate count and reduce exposure to noise through better qubit mapping and gate sequencing [20].

- Error-Aware Training: Incorporating noise models directly into the training process to find parameters that are inherently more robust to specific error channels [15].

- Entanglement Purification: Using quantum error-correcting codes specifically designed for sensing and learning tasks that protect entangled states while maintaining metrological advantage [23].

Advanced Sensing and Noise Characterization

Recent breakthroughs in quantum sensing directly impact our ability to characterize and combat noise in QNNs. Princeton researchers have developed diamond-based quantum sensors employing entangled nitrogen vacancy centers that provide roughly 40-times greater sensitivity than previous techniques [24]. By engineering two defects extremely close together (approximately 10 nanometers apart), these sensors can interact through quantum entanglement, enabling them to triangulate signatures in noisy fluctuations and effectively identify noise sources that were previously undetectable [24]. This enhanced sensing capability provides critical insights for developing targeted error mitigation strategies specific to individual quantum processing units.

The critical barrier imposed by noise on QNN depth and performance remains the foremost challenge in quantum machine learning. However, systematic benchmarking reveals that strategic architectural choices—particularly the inherent robustness of Quanvolutional Neural Networks against diverse noise channels—can significantly extend the practical capabilities of current NISQ devices. The experimental data clearly demonstrates that no single QNN architecture performs optimally across all noise environments, emphasizing the need for noise-aware model selection tailored to specific hardware characteristics and application domains.

For drug development professionals and research scientists, these findings suggest a pragmatic path forward: prioritizing QuanNN architectures for initial experimentation on current hardware, while monitoring emerging approaches like Density QNNs that show promise for addressing the pervasive trainability challenges in quantum machine learning. As noise characterization techniques continue to advance through innovations in quantum sensing, and error mitigation strategies grow more sophisticated, the depth barrier will progressively recede—ultimately enabling QNNs to fulfill their potential in revolutionizing complex scientific domains from molecular simulation to drug discovery.

In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, quantum computational advantage remains constrained by decoherence and gate errors that disrupt fragile quantum states. The strategic management of this inherent noise presents a critical path toward fault-tolerant quantum computation. This guide objectively compares two principal methodological approaches for characterizing and mitigating quantum noise: a novel symmetry-based framework for foundational noise characterization and contemporary architectural strategies for enhancing noise resilience in Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs).

The symmetry-driven approach, a breakthrough from Johns Hopkins University, leverages mathematical structure to simplify the exponentially complex problem of modeling noise across space and time in quantum processors [25]. In parallel, extensive empirical research evaluates the inherent robustness of various QNN architectures—Quanvolutional Neural Networks (QuanNN), Quantum Convolutional Neural Networks (QCNN), and Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL)—when subjected to specific quantum noise channels [15] [14]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these paradigms, detailing their experimental protocols, performance data, and practical applications to equip researchers with the tools for advancing quantum computing resilience.

Comparative Analysis of Methodologies

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the two primary noise characterization and mitigation strategies discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Comparison of Noise Characterization and Mitigation Methodologies

| Feature | Symmetry-Based Framework | QNN Architectural Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Uses root space decomposition and symmetry to classify noise [25] [26]. | Empirically tests the innate robustness of different QNN models to various noise channels [15] [14]. |

| Primary Application | Fundamental noise characterization and error correction code design [25]. | Selecting the most suitable algorithm for machine learning tasks on specific NISQ hardware [15]. |

| Key Advantage | Provides a foundational model for understanding and categorizing noise, informing mitigation [25]. | Delivers practical, immediate guidance for algorithm selection based on real-world noise conditions [15]. |

| Experimental Output | Noise classification (e.g., rung-changing vs. non-rung-changing) [25]. | Classification accuracy and performance metrics under defined noise [15]. |

| Limitation | Is a theoretical framework; requires integration into practical error correction [25]. | Results are comparative and may not provide a fundamental model of the noise itself [15]. |

Symmetry-Based Noise Characterization Framework

Core Protocol and Workflow

The protocol developed by researchers at Johns Hopkins APL and Johns Hopkins University exploits mathematical symmetry to simplify the complex dynamics of quantum noise [25] [26]. The methodology can be broken down into the following steps:

- System Representation: The quantum system is represented using a mathematical technique called root space decomposition. This structures the system's state space into a "ladder," where each rung corresponds to a discrete state of the system [25].

- Noise Introduction: Various noise models (e.g., spin, magnetic field fluctuations, thermal noise) are applied to the system [25].

- Noise Classification: The impact of each noise type is observed and classified based on its effect on the system's state:

- Rung-changing: Noise that causes the system to jump from one rung of the ladder to another.

- Non-rung-changing: Noise that disturbs the system without causing a transition between rungs [25].

- Mitigation Strategy Selection: The classification directly informs the mitigation technique. Rung-changing noise requires one strategy, while non-rung-changing requires another, simplifying the error correction process [25].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of this foundational framework:

Experimental Data and Validation

This framework represents a theoretical advance published in Physical Review Letters [25]. Its primary "result" is a new, more accurate model for understanding noise. The key validation lies in its ability to successfully classify complex, spatio-temporal noise phenomena that are intractable for simpler models, thereby providing a structured path toward more effective error-correcting codes [25] [26].

Noise Resilience in Quantum Neural Network Architectures

Experimental Protocol for QNN Comparison

In contrast to the foundational approach, empirical studies conduct comparative analyses of hybrid QNN architectures to evaluate their innate robustness. A standard protocol for such a comparison is detailed below [15]:

- Algorithm Selection: Three major HQNN algorithms are selected for testing:

- Quantum Convolutional Neural Network (QCNN): Inspired by classical CNNs, it uses entanglement and measurement reduction for feature extraction [15].

- Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN): Uses a quantum circuit as a sliding filter over input data for localized feature extraction [15].

- Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL): Integrates a pre-trained classical network with a quantum circuit for post-processing [15].

- Performance Baseline: The algorithms are first evaluated and compared under ideal, noise-free conditions across different circuit depths, entangling structures, and architectural placements to establish a performance baseline [15] [14].

- Noise Introduction: The highest-performing architectures from the baseline phase are subjected to systematic noise injection. Standard quantum noise channels simulated include:

- Phase Flip

- Bit Flip

- Phase Damping

- Amplitude Damping

- Depolarizing Channel [15]

- Robustness Evaluation: The models' performance (e.g., classification accuracy on a task like MNIST digits) is measured and compared across the different noise types and error probabilities [15].

Comparative Performance Data

The following table synthesizes quantitative results from a large-scale comparative analysis, highlighting the relative performance and robustness of the different QNN models [15].

Table 2: Experimental Results for QNN Robustness Under Quantum Noise

| QNN Model | Noise-Free Accuracy (Baseline) | Relative Robustness (Across Noise Channels) | Key Noise Resilience Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN) | High (e.g., ~30% higher than QCNN in one test [15]) | Highest | Demonstrated superior and consistent robustness across most quantum noise channels, including Phase Flip, Bit Flip, and Depolarizing noise [15] [14]. |

| Quantum Convolutional Neural Network (QCNN) | Lower than QuanNN [15] | Intermediate | Performance was significantly more affected by noise compared to QuanNN, showing varying resilience to different noise types [15]. |

| Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL) | Information Not Specified | Varies | Performance is highly dependent on the specific noise environment, with no consistent leading performance across all channels [15]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Researchers in this field rely on a combination of software development kits (SDKs), benchmarking tools, and theoretical frameworks to conduct noise characterization and resilience experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Quantum Noise Characterization

| Tool Name / Concept | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Root Space Decomposition | Mathematical Framework | Simplifies and structures the analysis of noise in quantum systems, enabling noise classification [25]. |

| QuantumACES.jl | Software Package | A Julia package designed to programmatically design and run noise characterization experiments on quantum computers [27]. |

| Benchpress | Benchmarking Suite | An open-source framework for evaluating the performance of quantum computing software (e.g., Qiskit, Cirq) in circuit creation, manipulation, and compilation, which affects overall noise resilience [28]. |

| Hybrid Quantum-Classical Neural Networks (HQNNs) | Algorithmic Paradigm | A NISQ-compatible architecture that combines classical neural networks with parameterized quantum circuits to harness quantum processing while mitigating errors [15]. |

| Standard Performance Evaluation Corp. (SPEC) | Conceptual Model | A proposed model for creating standardized performance evaluation benchmarks for quantum computers, ensuring fair and relevant comparisons [29]. |

| Hematoporphyrin IX dimethyl ester | Hematoporphyrin IX dimethyl ester, CAS:32562-61-1, MF:C36H42N4O6, MW:626.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Methyl cis-9,10-methylenehexadecanoate | Methyl cis-9,10-methylenehexadecanoate, MF:C18H34O2, MW:282.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The journey toward fault-tolerant quantum computing necessitates a multi-pronged attack on the problem of quantum noise. The symmetry-based characterization framework offers a profound theoretical advancement, providing a structured, mathematical language to model and classify the complex behavior of noise itself. This foundational work is a critical long-term investment for developing robust quantum error-correcting codes [25].

Concurrently, the empirical comparison of QNN architectures delivers immediate, actionable insights for practitioners operating on today's hardware. The consistent outperformance of the Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN) in noisy environments makes it a compelling choice for applied research in machine learning and drug development on NISQ devices [15] [14].

Ultimately, these approaches are complementary. A deeper foundational understanding of noise will inform the design of next-generation quantum algorithms, while empirical benchmarking provides the necessary feedback loop to test theories and guide practical application. The integration of rigorous characterization frameworks, like the one leveraging symmetry, with standardized benchmarking suites, such as Benchpress, will be instrumental in building the error-resilient quantum systems of the future [25] [29] [28].

Linking Noise Profiles to Algorithmic Failure in Biomedical Simulations

The integration of advanced computational models, including Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs), into biomedical simulation pipelines promises to accelerate breakthroughs in drug development and diagnostic systems. However, the performance and reliability of these models are highly sensitive to data corruption and inherent computational noise. In the context of a broader thesis benchmarking noise resilience across quantum neural network architectures, this guide provides a comparative analysis of how different algorithmic families fail under specific noise profiles relevant to biomedical data. Understanding the linkage between noise type and algorithmic failure mode is critical for researchers and scientists to select appropriate, resilient tools for tasks such as automated diagnosis, molecular simulation, and patient data analysis.

Comparative Analysis of Algorithmic Performance Under Noise

Classical Machine Learning: The Tsetlin Machine

Experimental Protocol: A study evaluated the resilience of a Tsetlin Machine (TM), a logic-based machine learning algorithm, on three medical datasets: Breast Cancer, Pima Indians Diabetes, and Parkinson's disease [30]. Noise was injected directly into the datasets by reducing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The research compared two feature extraction methods in conjunction with the TM: a standard "Fixed Thresholding" approach and a novel discretization and rule mining method designed to filter noise during data encoding [30]. Performance was measured through sensitivity, specificity, and model parameter stability (Nash equilibrium) at SNRs as low as -15 dB [30].

Key Findings: The TM demonstrated remarkable robustness to noise injection, maintaining effective classification even at very low SNRs [30]. The proposed discretization and rule mining encoding method was particularly effective, allowing high testing data sensitivity by balancing feature distribution and filtering noise. This method also reduced model complexity and memory footprint by up to 6x fewer training parameters while retaining performance [30].

Table 1: Performance Summary of Classical Tsetlin Machine under Noise

| Dataset | Performance Metric | High SNR | Low SNR (-15 dB) | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | Sensitivity | Effective | Effective | Parameters remain stable (Nash equilibrium) [30] |

| Pima Indians Diabetes | Specificity | Effective | Effective | Model maintains performance [30] |

| Parkinson's Disease | Model Complexity | Standard | Up to 6x reduction | With novel encoding method [30] |

Hybrid Quantum Neural Networks (HQNNs)

Experimental Protocol: A comprehensive comparative analysis evaluated three HQNN algorithms—Quantum Convolutional Neural Network (QCNN), Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN), and Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL)—on image classification tasks (e.g., MNIST) [5] [15]. The highest-performing architectures from noise-free conditions were selected and subjected to systematic noise robustness testing. Five quantum gate noise models were introduced: Bit Flip, Phase Flip, Phase Damping, Amplitude Damping, and the Depolarizing Channel [5] [15]. The performance and resilience of each model were measured against these noise channels.

Key Findings: The study revealed that QuanNN generally exhibited greater robustness across various quantum noise channels, consistently outperforming QCNN and QTL in most scenarios [5] [15]. This highlights that noise resilience is architecture-dependent in the NISQ era.

Table 2: Noise Resilience of Hybrid Quantum Neural Networks [5] [15]

| HQNN Architecture | Overall Noise Resilience | Resilience to Bit/Phase Flip | Resilience to Amplitude/Phase Damping | Resilience to Depolarizing Noise |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN) | Highest | High | High | High |

| Quantum Convolutional Network (QCNN) | Lower than QuanNN | Moderate | Moderate | Low-Moderate |

| Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL) | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies |

Advanced Quantum Error Mitigation: Zero-Noise Knowledge Distillation

Experimental Protocol: To address two-qubit gate noise, a training-time technique called Zero-Noise Knowledge Distillation (ZNKD) was proposed [31]. This method uses a teacher-student framework. A teacher QNN employs Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE), running circuits at scaled noise levels to extrapolate zero-noise outputs. A compact student QNN is then trained using variational learning to mimic the teacher's extrapolated, noise-free outputs, thus incorporating robustness directly into its parameters without needing costly inference-time extrapolation [31]. Performance was evaluated in dynamic-noise simulations (IBM-style (T1/T2), depolarizing, readout) on datasets like Fashion-MNIST and UrbanSound8K [31].

Key Findings: ZNKD successfully distilled robustness from the teacher to the student QNN. The student's Mean Squared Error (MSE) was reduced by 0.06–0.12 (≈10-20%), keeping its accuracy within 2%–4% of the teacher's while maintaining a compact size (6:2 to 8:3 teacher-to-student qubit ratio) [31]. This demonstrates the potential of advanced training techniques to amortize error mitigation costs.

Experimental Protocols for Noise Robustness Evaluation

Protocol 1: Injecting Classical Noise into Biomedical Data

This protocol is designed for benchmarking classical and hybrid models on noisy biomedical datasets [30].

- Data Selection: Choose curated biomedical datasets (e.g., Breast Cancer, Pima Indians Diabetes) where ground truth is known.

- Noise Injection: Corrupt the dataset features by adding Gaussian or other relevant noise to achieve a target Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR). The study in [30] tested a range down to -15 dB.

- Feature Engineering: Apply feature extraction and encoding methods. Compare standard techniques (e.g., Fixed Thresholding) against noise-resilient methods (e.g., the proposed discretization and rule mining algorithm) [30].

- Model Training & Evaluation: Train the ML models (e.g., Tsetlin Machine, neural networks) on the noise-injected data. Evaluate performance based on sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy on a held-out test set. Monitor model parameter stability as an indicator of robustness [30].

Protocol 2: Evaluating HQNNs under Quantum Gate Noise

This protocol assesses the inherent resilience of quantum algorithms to NISQ-era hardware noise [5] [15].

- Architecture Selection: Identify candidate HQNN architectures (e.g., QuanNN, QCNN, QTL) and optimize their circuit designs (entangling structures, layer count) in a noise-free setting.

- Noise Channel Definition: Define the quantum noise channels to test. Standard channels include [5] [15]:

- Bit Flip: ( X ) gate error with probability ( p ).

- Phase Flip: ( Z ) gate error with probability ( p ).

- Amplitude Damping: Models energy dissipation.

- Phase Damping: Models loss of quantum information without energy loss.

- Depolarizing Channel: Replaces the qubit state with a maximally mixed state with probability ( p ).

- Simulation & Metrics: Run the selected HQNN architectures on classical simulators that emulate these noise models. Measure performance degradation in terms of validation accuracy and loss across different noise probabilities.

Protocol 3: Zero-Noise Knowledge Distillation

This protocol is for building noise resilience directly into a model during training [31].

- Teacher Model Preparation: Construct a teacher QNN that utilizes Zero-Noise Extrapolation. This involves running the quantum circuit at amplified noise levels (e.g., via unitary folding) and extrapolating the results to the zero-noise limit.

- Student Model Training: Design a more compact student QNN (fewer qubits or shallower circuits). Train the student not on the original noisy data, but to replicate the teacher's extrapolated, noise-free outputs.

- Robustness Validation: Evaluate the final student model on a test set under dynamic, unseen noise conditions. Compare its performance and resource requirements against the teacher and a baseline model trained without distillation.

Visualizing Algorithmic Failure and Resilience

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows discussed in this guide.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Noise-Resilient Biomedical Simulation Research

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation | Exemplar Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Tsetlin Machine (TM) | A logic-based ML algorithm that forms conjunctive clauses in Boolean input, offering high interpretability and inherent robustness to noisy data [30]. | Classifying noisy biomedical records (e.g., diabetic diagnosis) with high sensitivity at low SNRs [30]. |

| Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN) | An HQNN that uses a quantum circuit as a sliding filter over input data, demonstrating superior inherent resilience to a variety of quantum gate noises compared to other QNNs [5] [15]. | Image-based diagnostic tasks (e.g., mammogram analysis) on noisy intermediate-scale quantum hardware. |

| Zero-Noise Knowledge Distillation (ZNKD) | A training-time technique that distills robustness from a noise-aware "teacher" QNN to a compact "student" QNN, amortizing the cost of error mitigation [31]. | Deploying robust, smaller QNNs for molecular property prediction in drug discovery, mitigating NISQ hardware errors. |

| Variational Quantum Circuit (VQC) | The fundamental parameterized quantum circuit in HQNNs, optimized using classical methods. It is the core "building block" for quantum machine learning [5] [15]. | Serving as the quantum layer in hybrid models for solving differential equations relevant to pharmacokinetics [32]. |

| Discretization & Rule Mining Encoding | A preprocessing method that converts continuous features into discrete symbols and mines logical rules, filtering noise and reducing problem space complexity [30]. | Preparing noisy clinical data for interpretable ML models, enhancing resilience while reducing model size. |

| Hydroxy-PEG12-t-butyl ester | Hydroxy-PEG12-t-butyl ester, MF:C31H62O15, MW:674.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (3-Aminopropyl)glycine | (3-Aminopropyl)glycine, CAS:2875-41-4, MF:C5H12N2O2, MW:132.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Strategies for Noise-Resilient QNN Design and Implementation in Biomedical Tasks

In the pursuit of practical quantum computing in the noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) era, characterizing and understanding quantum noise has emerged as a prerequisite for developing robust quantum algorithms. This guide provides a systematic comparison of two critical strands of noise characterization research: Pauli error estimation for modeling computational noise and the decomposition of State Preparation and Measurement (SPAM) errors for diagnosing initialization and readout imperfections. Framed within broader research on benchmarking the noise resilience of quantum neural network (QNN) architectures, this analysis equips researchers with the methodologies and metrics needed to objectively evaluate the performance of quantum characterization techniques under realistic laboratory conditions.

Experimental Protocols for Noise Characterization

Pauli Error Estimation

Pauli error estimation aims to reconstruct the Pauli channel, a fundamental model of noise in quantum systems characterized by error rates on individual Pauli operators. A significant challenge has been making these estimations robust to State Preparation and Measurement (SPAM) errors, which traditionally corrupt the results.

SPAM-Tolerant Protocol: Recent work by O'Donnell et al. introduces an algorithm that addresses the open problem of SPAM tolerance in Pauli error estimation [33]. The method builds upon a reduction to the Population Recovery problem and is capable of tolerating even severe SPAM errors. The key innovation involves analyzing population recovery on a combined erasure/bit-flip channel, which requires extensions of complex analysis techniques.

- Scalability: The algorithm requires only exp(ð‘›Â¹/³) unentangled state preparations and measurements for an ð‘›-qubit channel. This represents a significant improvement over previous SPAM-tolerant algorithms, which exhibited 2â¿-dependence even for restricted families of Pauli channels [33].

- Theoretical Limit: Evidence suggests that no SPAM-tolerant method can make asymptotically fewer than exp(ð‘›Â¹/³) uses of the channel, indicating this approach operates near the theoretical efficiency limit [33].

SPAM Error Tomography and Decomposition

Unlike gate errors, SPAM errors impact the initial and terminal stages of quantum algorithms, undermining the accuracy of quantum tomography, fidelity estimation, and error correction schemes [34]. Standard SPAM tomography does not assume prior knowledge of either the prepared states or the measurement apparatus.

Gauge-Invariant Protocol: A fundamental challenge in SPAM tomography is gauge freedom—the existence of intrinsic ambiguities where multiple solutions for state and measurement parameters are consistent with the same experimental data. For a ð‘‘-dimensional system, there are ð‘‘²(ð‘‘²−1) undetermined gauge parameters (e.g., 12 parameters for a qubit) [34]. To circumvent this, the protocol uses gauge-invariant quantities derived directly from the measurement data matrix ð‘†.

- Detection of Correlated Errors: For qubits, the data matrix 𑆠is partitioned into four submatrices (e.g., ð‘„â‚â‚, ð‘„â‚â‚‚, ð‘„â‚‚â‚, ð‘„â‚‚â‚‚). A key gauge-invariant relation is defined as Δ(ð‘†) ≡ ð‘„â‚â‚â»Â¹ð‘„â‚â‚‚ð‘„â‚‚â‚‚â»Â¹ð‘„â‚‚â‚. A violation of Δ(ð‘†) = 🙠serves as a gauge-invariant indicator of correlated SPAM error between state preparation and measurement [34].

- Experimental Workflow: The protocol involves preparing multiple (at least five) different states and performing measurements with multiple (five or more) detector settings to form a sufficiently large data matrix ð‘†. By partitioning 𑆠and evaluating Δ(ð‘†), experimenters can diagnose correlated SPAM errors without fixing a gauge.

Performance Comparison of Characterization Methods

The following table summarizes the performance and characteristics of various noise characterization methods, including Pauli error estimation and SPAM tomography, based on benchmarking studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Quantum Characterization Methods

| Characterization Method | Key Objective | Information Obtained | Scalability | Key Findings from Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPAM-Tolerant Pauli Estimation [33] | Reconstruct Pauli channel noise model | Pauli error rates | exp(ð‘›Â¹/³) scaling | Robust to severe SPAM errors; near-optimal resource usage. |

| SPAM Tomography [34] | Diagnose correlated state prep & measurement errors | Gauge-invariant indicators of correlated SPAM | Model-independent protocols | Detects correlations that undermine standard tomography. |

| Gate Set Tomography (GST) [35] | Develop detailed noise models for gate sets | Comprehensive gate error models | High resource requirements | Accuracy of model does not always correlate with information gained [35]. |

| Pauli Channel Noise Reconstruction [35] | Reconstruct Pauli noise channel | Pauli error channel | Varies | Underlying circuit strongly influences best choice of method [35]. |

| Empirical Direct Characterization [35] | Model noisy circuit performance | Predictive noise models for circuits | Scales best among tested methods | Produced the most accurate characterizations in benchmarks [35]. |

Implications for Quantum Neural Network Benchmarking

The fidelity of characterization methods directly impacts the assessment of QNN robustness. Research shows that different QNN architectures—Quantum Convolutional Neural Networks (QCNN), Quanvolutional Neural Networks (QuanNN), and Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL)—exhibit varying resilience to different types of quantum noise [14]. Furthermore, adversarial robustness in QML introduces unique challenges; unlike classical adversarial examples in â„ð‘‘, perturbations can occur in Hilbert space (state perturbations), variational parameter space, or even the measurement process itself [36]. Reliable noise profiling is therefore the foundation for accurately benchmarking and comparing the inherent noise resilience of different QNN architectures.

Table 2: Noise Resilience of Quantum Neural Network Architectures

| QNN Architecture | Noise Robustness Profile | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN) | Greater robustness across various quantum noise channels [14]. | Consistently outperformed other models in noisy conditions; highlights importance of model selection for noise environment [14]. |

| Quantum Convolutional Neural Network (QCNN) | Varying resilience to different noise gates [14]. | Performance is highly dependent on the specific noise channel and circuit structure [14]. |

| Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL) | Varying resilience to different noise gates [14]. | Performance is highly dependent on the specific noise channel and circuit structure [14]. |

Visualization of Characterization Workflows

SPAM Error Tomography and Detection

SPAM-Tolerant Pauli Error Estimation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Solutions for Quantum Noise Profiling

| Item / Protocol | Function in Noise Characterization |

|---|---|

| Gauge-Invariant Metric Δ(ð‘†) | Diagnoses correlated SPAM errors without gauge-fixing, using only experimental data [34]. |

| SPAM-Tolerant Population Recovery Algorithm | Enables robust Pauli error estimation independent of state preparation and measurement infidelities [33]. |

| Root Space Decomposition | A mathematical technique that exploits symmetry to simplify the analysis of spatially and temporally correlated quantum noise [37]. |

| Parameterized Quantum Circuits (PQCs) | Serve as the testbed for evaluating adversarial robustness and uncertainty quantification in QML systems [36]. |

| Multiple State Preparations & Detector Settings | Creates the data matrix necessary for SPAM tomography and detecting correlated errors [34]. |

| Randomized Benchmarking Circuits | Used to probe high-level performance and validate noise models derived from characterization data [35] [38]. |

| 3-Methyl-1-tosyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine | 3-Methyl-1-tosyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine, MF:C11H13N3O2S, MW:251.31 g/mol |

| Difelikefalin acetate | Difelikefalin acetate, CAS:1024829-44-4, MF:C38H57N7O8, MW:739.9 g/mol |

In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, quantum neural networks (QNNs) are significantly hampered by environmental noise, gate errors, and decoherence. For researchers in fields like drug development, where quantum computing promises accelerated molecular simulations, the choice of QNN architecture is not merely a theoretical concern but a practical necessity for obtaining reliable results. This guide provides an objective comparison of mainstream hybrid quantum neural network (HQNN) architectures, focusing on their intrinsic resilience to various quantum noise channels. By synthesizing recent benchmarking studies, we present a data-driven framework to inform the selection and design of QNN circuits tailored for robust performance on today’s imperfect hardware.

Comparative Analysis of QNN Architectures

- Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN): This architecture uses a quantum circuit as a sliding filter over input data, mimicking classical convolutional layers to extract local features through quantum transformation [39] [40]. Its hybrid design typically processes quantum-filtered features with a subsequent classical neural network.

- Quantum Convolutional Neural Network (QCNN): Inspired by the hierarchical structure of classical CNNs, this architecture encodes a downsized input into a quantum state. Its "convolutional" and "pooling" layers are implemented through fixed variational circuits, qubit entanglement, and measurement reduction [39].

- Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL): This approach integrates a pre-trained classical neural network with a quantum circuit for post-processing, transferring knowledge from a classical to a quantum setting [14] [39].

Experimental Framework and Benchmarking Protocol

Recent comparative studies have established a rigorous methodology for evaluating noise robustness. The following table summarizes the core experimental setup common to these benchmarks.

Table 1: Standardized Experimental Protocol for Noise Robustness Evaluation

| Protocol Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary Tasks | Image classification on standardized datasets (e.g., MNIST, Fashion-MNIST) [40] [41]. |

| Circuit Scale | Typically 4-qubit variational quantum circuits (VQCs) [40]. |

| Noise Channels | Phase Flip, Bit Flip, Phase Damping, Amplitude Damping, Depolarizing Channel [14] [39] [40]. |

| Noise Injection | Systematic introduction after each parametric gate and entanglement block [40]. |

| Noise Probability (p) | Varied from 0.0 (noise-free) to 1.0 (maximum noise) in increments of 0.1 [41]. |

| Evaluation Metric | Classification accuracy on a held-out test set [14] [40]. |

The logical workflow for these benchmarking experiments, which facilitates reproducible and vendor-neutral assessment, is outlined below.

Quantitative Performance and Noise Resilience

Comparative Performance Data

The following table synthesizes key findings from recent studies, comparing the performance of QuanNN, QCNN, and QTL architectures under various noise conditions.

Table 2: Comparative Performance and Noise Resilience of HQNN Architectures

| Architecture | Noise-Free Performance | Robustness to Low Noise (p=0.1-0.4) | Robustness to High Noise (p=0.5-1.0) | Notable Noise-Specific Behaviors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN) | High validation accuracy [39] | Robust across most noise channels [40] [41] | Performance degradation with Depolarizing and Amplitude Damping noise [40] [41] | Exhibits robustness to Bit Flip noise even at p=0.9-1.0 [40] [41] |

| Quantum Convolutional Neural Network (QCNN) | Lower than QuanNN (≈30% gap in one study) [39] | Gradual performance degradation for some noise types [41] | Can benefit from noise; outperforms noise-free model for Bit Flip, Phase Flip, Phase Damping at high p [40] [41] | Performance is more task-dependent; degrades more on complex tasks (e.g., Fashion-MNIST) [40] |

| Quantum Transfer Learning (QTL) | Evaluated in comparative analysis [14] [39] | Specific resilience profile varies | Specific resilience profile varies | QuanNN generally demonstrated greater robustness across various channels [14] [39] |

Visualizing the Noise Robustness Framework

The process of evaluating a QNN's intrinsic resilience to different types of quantum noise involves a structured framework, from noise injection to performance analysis, as depicted in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit

For researchers aiming to replicate these benchmarking studies or develop new noise-resilient QNN circuits, the following tools and resources are essential.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for QNN Noise Resilience Research

| Tool / Resource | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| QUARK Framework | An application-oriented benchmarking framework for quantum computing [42]. | Orchestrates the entire benchmarking pipeline, from hardware selection to algorithmic design and data collection, ensuring reproducibility [42]. |

| Quantum SDKs | Software development kits for quantum circuit design and simulation (e.g., Qiskit, PennyLane) [42]. | Provides the interface for defining parameterized quantum circuits (PQCs), mapping them to simulators or real hardware, and configuring noise models [42]. |

| Noise Model Simulators | Backends that simulate quantum noise using defined error channels and probabilities [40] [42]. | Allows for the injection of specific noise types (e.g., Phase Damping, Depolarizing) into quantum circuits to test robustness before running on physical QPUs [42]. |

| Classical Datasets | Standardized image datasets for machine learning (e.g., MNIST, Fashion-MNIST) [40] [41]. | Serves as a benchmark task for evaluating and comparing the performance of different QNN architectures on a well-understood problem [40]. |

| Optimizers | Classical algorithms for optimizing the parameters of the VQC (e.g., gradient-based methods, CMA-ES) [42]. | Trains the hybrid quantum-classical model by minimizing a cost function, such as classification error or statistical divergence [42]. |

| DL-threo-2-methylisocitrate | DL-threo-2-methylisocitrate, CAS:71183-66-9, MF:C7H10O7, MW:206.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Treprostinil Palmitil | Treprostinil Palmitil, CAS:1706528-83-7, MF:C39H66O5, MW:614.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The quest for intrinsic noise robustness in QNNs does not yield a single universal solution. Instead, the optimal architectural choice is contingent on the specific noise profile of the target quantum processing unit (QPU) and the complexity of the task. Evidence consistently positions the Quanvolutional Neural Network (QuanNN) as a robust general-purpose architecture, demonstrating resilience across a wide range of low-to-medium noise levels and even against high-probability Bit Flip errors. Conversely, the Quantum Convolutional Neural Network (QCNN), while sometimes outperforming its noise-free version under specific high-noise conditions, exhibits greater performance volatility and task dependence. For researchers in applied fields like drug development, this underscores the critical importance of characterizing the noise environment of their chosen quantum hardware and aligning it with the known robustness profile of a QNN architecture, using the experimental protocols and data outlined in this guide to inform their design decisions.

Active and Passive Error Mitigation Protocols for Quantum Machine Learning

Quantum Machine Learning (QML) represents a promising intersection of quantum computing and classical machine learning, aiming to leverage quantum resources to enhance computational tasks [43]. However, the practical utility of QML on current noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices is severely constrained by quantum errors arising from decoherence and imperfect gate operations [44] [45]. These errors necessitate robust strategies for error mitigation to achieve reliable computation.