Benchmarking Quantum Optimization Algorithms: Performance, Applications, and Path to Quantum Advantage

This comparative study provides a comprehensive analysis of the current performance landscape of quantum optimization algorithms, addressing a critical need for researchers and professionals in fields like drug development.

Benchmarking Quantum Optimization Algorithms: Performance, Applications, and Path to Quantum Advantage

Abstract

This comparative study provides a comprehensive analysis of the current performance landscape of quantum optimization algorithms, addressing a critical need for researchers and professionals in fields like drug development. We explore the foundational principles of quantum optimization, detail the methodologies of leading algorithms such as QAOA and VQE, and examine practical troubleshooting for near-term hardware limitations. Crucially, the article synthesizes results from recent, rigorous benchmarking initiatives—including the 'Intractable Decathlon' and the Quantum Optimization Benchmarking Library (QOBLIB)—to validate performance against state-of-the-art classical solvers. By outlining clear paths for optimization and future development, this work serves as a guide for understanding the real-world potential and current limitations of quantum-enhanced optimization.

Quantum Optimization Foundations: From Core Principles to the Quest for Advantage

Quantum optimization represents a frontier in computational science, promising to tackle complex problems that are intractable for classical computers. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the current performance of quantum optimization algorithms, categorizing them into exact, approximate, and heuristic approaches. As quantum hardware undergoes rapid advancement, with quantum processor performance improving and error rates declining, understanding the capabilities and limitations of each algorithmic paradigm becomes crucial for researchers and drug development professionals [1] [2]. The field is transitioning from theoretical research to practical applications, evidenced by commercial deployments in industries including pharmaceuticals, finance, and logistics [3]. This analysis synthesizes recent experimental data, theoretical developments, and performance benchmarks to inform strategic algorithm selection for scientific and industrial applications.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Quantum Optimization Approaches

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and performance metrics of the primary quantum optimization approaches based on current implementations and research.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Quantum Optimization Approaches

| Approach | Representative Algorithms | Theoretical Speedup | Current Feasibility | Solution Quality | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exact | Grover-based Search [4] | Quadratic (Proven) | Near-term for specific problems | Optimal | Continuous optimization, spectral analysis [4] |

| Approximate | Decoded Quantum Interferometry (DQI) [5], Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) [6] | Super-polynomial to Quadratic (Proven for specific problems) | Emerging utility-scale | Near-optimal | Polynomial regression (OPI), Test Case Optimization (TCO) [5] [6] |

| Heuristic | Quantum Annealing (QA) [7], Variational Algorithms | Unproven general speedup; potential from tunneling | Commercially available on specialized hardware | High-quality feasible | Wireless network scheduling, logistics, material simulation [3] [7] |

Detailed Examination of Algorithmic Approaches

Exact Quantum Optimization Algorithms

Exact algorithms are designed to find the optimal solution to an optimization problem with a proven quantum speedup.

- Grover-based Continuous Search: Recent research has extended Grover's quadratic speedup from discrete to continuous optimization problems. A 2025 algorithm from the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China can search uncountably infinite solution spaces, with rigorous proof of a quadratic query speedup and established optimality [4]. This is a significant theoretical advance for high-dimensional optimization and infinite-dimensional spectral analysis.

Approximate Quantum Optimization Algorithms

Approximate algorithms sacrifice guaranteed optimality for computationally tractable, high-quality solutions.

- Decoded Quantum Interferometry (DQI): This algorithm, introduced by Google Quantum AI and collaborators, uses quantum interference to find near-optimal solutions. Its performance depends on converting an optimization problem into a structured decoding problem. For the Optimal Polynomial Intersection (OPI) problem, DQI can find solutions using millions of quantum operations, a task estimated to require over 100 sextillion operations on a classical computer [5].

- Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA): Applied to industrial Test Case Optimization (TCO), an approach called IGDec-QAOA has been evaluated on simulators and real quantum hardware. On an ideal simulator, it matched the effectiveness of a Genetic Algorithm (GA) and outperformed it in two out of five problems. It also demonstrated feasibility on noisy quantum devices [6].

Heuristic Quantum Optimization Algorithms

Heuristic algorithms leverage physical quantum processes to search for good solutions without theoretical speedup guarantees.

- Quantum Annealing (QA): This approach, used by companies like D-Wave, is applied to Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) problems. It is theorized to leverage quantum tunneling to escape local minima more effectively than classical simulated annealing (SA). A study on wireless network scheduling showed that a "gap expansion" technique to reduce errors benefited QA more than SA, leading to performance improvements in metrics like network queue occupancy [7]. Commercial applications include Ford Otosan using D-Wave's annealers to reduce scheduling times from 30 minutes to less than five minutes in a production environment [3].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Protocol: Quantum Annealing for Network Scheduling

This experiment benchmarks Quantum Annealing (QA) against Simulated Annealing (SA) on a real-world problem [7].

- Objective: Solve a K-hop wireless network scheduling problem, formulated as a Weighted Maximum Independent Set (WMIS) problem on a conflict graph, to maximize network throughput.

Methodology:

- Problem Mapping: The network scheduling problem is mapped to a QUBO/Ising model. A "gap expansion" technique adjusts penalty weights in the Hamiltonian to reduce errors from hardware imperfections.

- Hardware Execution: The problem is minor-embedded into the D-Wave Chimera quantum annealer. Multiple annealing runs are performed.

- Classical Comparison: The same problem is solved using a highly-optimized SA algorithm (

an_ss_ge_fi_vdeg). - Metrics: Performance is compared using

ST99speedup (time for SA to reach a solution quality achieved by QA 99% of the time) and network queue occupancy.

Results: The study on 15-node and 20-node random networks found that the gap expansion process disproportionately benefited QA over SA. QA showed better performance in both

ST99speedup and lower network queue occupancy, suggesting a potential performance advantage in this application niche [7].

Protocol: QAOA for Test Case Optimization

This experiment evaluates the practical performance of QAOA on a software engineering task [6].

- Objective: Reduce software testing cost via Test Case Optimization (TCO) using a hybrid quantum-classical approach.

- Methodology:

- Algorithm Design: The TCO problem is formulated for QAOA. A problem decomposition strategy (IGDec-QAOA) is integrated to handle large datasets on limited qubits.

- Evaluation Platforms: The algorithm is run on ideal simulators, noisy simulators, and a real quantum computer.

- Classical Comparison: Performance is compared against a Genetic Algorithm (GA) and Random Search using industrial datasets from ABB, Google, and Orona.

- Results: On an ideal simulator, IGDec-QAOA reached the same effectiveness as GA and outperformed it in two out of five problems. The algorithm maintained similar performance on a noisy simulator and was demonstrated to be feasible on real quantum hardware [6].

Visualizing the Quantum Optimization Workflow

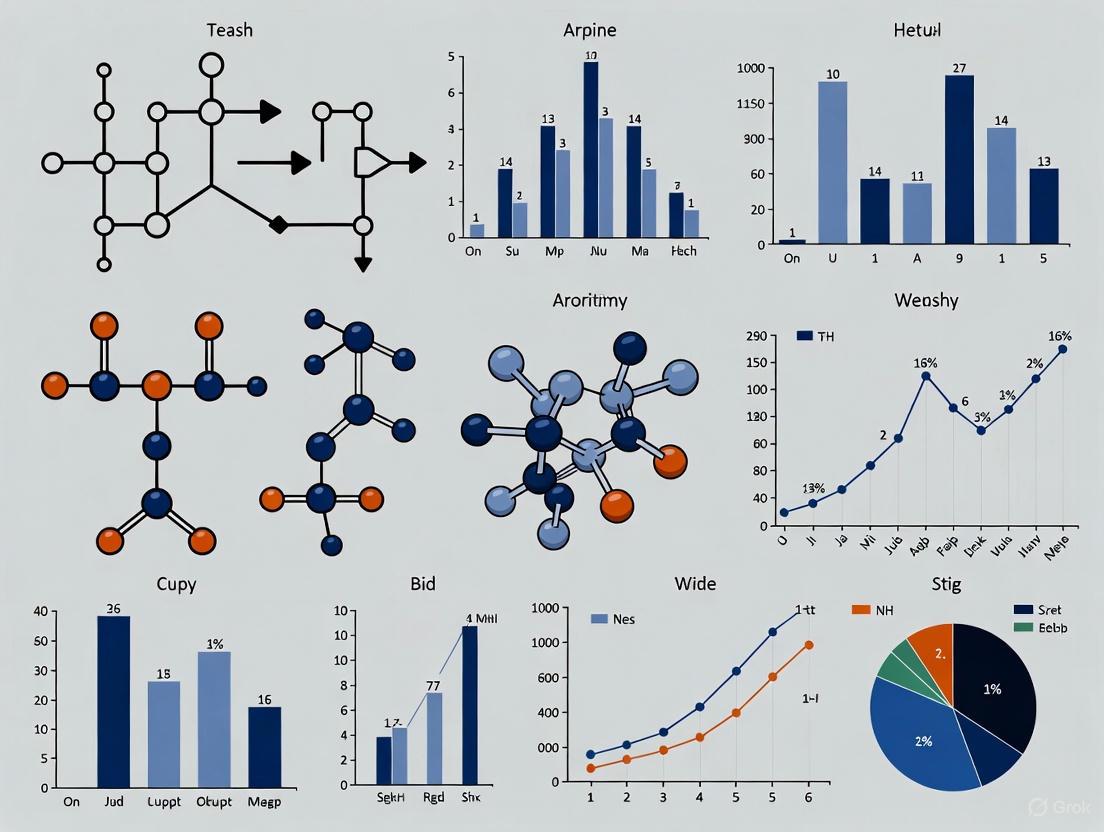

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and high-level workflows for the primary quantum optimization approaches discussed.

Diagram 1: Quantum optimization algorithm selection workflow.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Quantum Optimization Reagents

Table 2: Essential Resources for Quantum Optimization Research

| Resource / 'Reagent' | Function / Purpose | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Processing Units (QPUs) | Provides the physical hardware for executing quantum circuits or annealing schedules. | Over 40 QPUs are commercially available (e.g., IonQ Tempo, IBM Heron, D-Wave Annealers). Performance varies by qubit count, connectivity, and fidelity [1] [3]. |

| Software Development Kits (SDKs) | Enables the design, simulation, and compilation of quantum algorithms. | Qiskit (IBM): High-performing, open-source SDK with C++ API for HPC integration [8]. CUDA-Q (Nvidia): For hybrid quantum-classical computing and AI [3]. |

| Error Mitigation & Correction Tools | Suppresses, mitigates, or corrects hardware errors to improve result accuracy. | Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC): Software technique to remove bias from noisy circuits [8]. qLDPC Codes: Advanced error correction codes being developed for fault tolerance [8]. |

| Cloud Access Platforms | Provides remote access to quantum hardware and simulators. | AWS Braket, Microsoft Azure Quantum, Google Cloud Platform. Essential for algorithm testing and benchmarking across different hardware types [3] [9]. |

| Classical Optimizers | A critical component in hybrid algorithms (e.g., QAOA, VQE) that tunes parameters. | Includes optimizers like COBYLA, SPSA, and BFGS. Their performance directly impacts the convergence and quality of hybrid quantum algorithms. |

| 4-Methoxy-2,3,5,6-tetramethylphenol | 4-Methoxy-2,3,5,6-tetramethylphenol|CAS 19587-93-0 | |

| 3-(Pyridin-4-yl)-1,2-oxazol-5-amine | 3-(Pyridin-4-yl)-1,2-oxazol-5-amine | High-purity 3-(Pyridin-4-yl)-1,2-oxazol-5-amine (CAS 186960-06-5) for research. This compound is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. |

The quantum optimization landscape is diversifying, with exact, approximate, and heuristic approaches finding their respective niches. Exact methods offer proven speedups but are currently limited to specific problem classes. Approximate algorithms like DQI and QAOA are showing promising, provable advantages for structured problems and are becoming feasible on utility-scale systems. Heuristic methods, particularly quantum annealing, are already tackling commercially relevant optimization problems, with demonstrated performance benefits in some cases over classical heuristics. For researchers in fields like drug development, the choice of algorithm depends critically on the problem structure and the requirement for proven optimality versus a high-quality feasible solution. As hardware continues to improve, with roadmaps targeting fault-tolerant systems by 2029-2030, the practical applicability and performance advantages of these quantum approaches are expected to expand significantly [3] [8].

Quantum computing represents a fundamental shift in computational paradigms, leveraging the core phenomena of superposition and entanglement to tackle combinatorial optimization problems that remain intractable for classical computers. Unlike classical bits that exist in definite states of 0 or 1, quantum bits (qubits) can exist in superposition of both states simultaneously, enabling quantum computers to explore multiple solution paths in parallel [10]. Furthermore, entanglement creates profound correlations between qubits such that the state of one qubit cannot be described independently of the others, enabling complex computational relationships that have no classical equivalent [11].

In the context of combinatorial optimization—which encompasses critical domains from drug discovery to logistics—these quantum phenomena enable novel approaches to searching vast solution spaces. The translation of real-world problems into quantum frameworks typically utilizes mathematical formulations such as the Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) formalism or the equivalent Ising model, where the solution corresponds to finding the ground state of a quantum Hamiltonian [11] [10]. This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of leading quantum optimization approaches, examining their experimental performance, resource requirements, and practical implementation methodologies to guide researchers in selecting appropriate quantum strategies for combinatorial problems.

Core Quantum Optimization Algorithms: A Comparative Framework

Quantum optimization has evolved along several algorithmic pathways, each with distinct mechanisms, hardware requirements, and application profiles. The leading approaches include quantum annealing, the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA), and the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), which form the primary frameworks for current near-term quantum optimization research.

Algorithmic Mechanisms and Hardware Foundations

Quantum Annealing operates on analog quantum processors and is inspired by the physical process of annealing. The system is initialized in a simple ground state and evolves according to the principles of adiabatic quantum computation, gradually introducing problem constraints until the system reaches a low-energy state representing the optimal solution [10]. This approach is particularly implemented in D-Wave's quantum annealers, which currently lead in qubit count with 5,000+ qubits in the Advantage model [11].

The Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) employs a hybrid quantum-classical approach on gate-model quantum computers. It alternates between two quantum operators: a problem Hamiltonian encoding the objective function and a mixer Hamiltonian that facilitates exploration of the solution space [12] [10]. Through iterative execution on quantum hardware and parameter optimization on classical computers, QAOA converges toward approximate solutions. Experimental implementations have demonstrated this approach on IBM's gate-model quantum systems utilizing up to 127 qubits [12].

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) shares the hybrid structure of QAOA but focuses primarily on continuous optimization problems, making it particularly valuable for quantum chemistry and molecular simulations [10]. Unlike QAOA's discrete optimization focus, VQE excels at estimating ground state energies of quantum systems, which is fundamental for studying molecular behavior in drug development applications.

Table 1: Core Quantum Optimization Algorithms Comparison

| Algorithm | Computational Paradigm | Hardware Type | Problem Focus | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Annealing | Analog | Quantum Annealers (e.g., D-Wave) | Combinatorial Optimization | Adiabatic evolution to ground state |

| QAOA | Digital (Hybrid) | Gate-model (e.g., IBM, Rigetti) | Combinatorial Optimization | Parameterized unitary rotations |

| VQE | Digital (Hybrid) | Gate-model (e.g., IBM, Rigetti) | Continuous Optimization, Quantum Chemistry | Variational principle for ground state energy |

Quantum Phenomena in Algorithmic Operation

The computational advantage of these algorithms stems from their exploitation of fundamental quantum phenomena. Superposition enables the simultaneous evaluation of exponentially many potential solutions, while entanglement creates complex correlations between different parts of the solution space that guide the optimization process toward high-quality solutions [11] [10]. In quantum annealing, these phenomena facilitate quantum tunneling through energy barriers rather than classical thermal excitation, potentially providing more efficient exploration of complex energy landscapes. In QAOA and VQE, carefully designed quantum circuits leverage interference effects to amplify probability amplitudes corresponding to high-quality solutions while suppressing poor solutions.

Performance Benchmarks: Experimental Data and Comparative Analysis

Rigorous evaluation of quantum optimization performance requires multiple metrics including solution quality, computational resource requirements, and scalability. Recent experimental studies across various hardware platforms provide insightful comparisons between quantum and classical approaches, as well as between different quantum algorithms.

Large-Scale Experimental Comparisons

A comprehensive analysis of six representative quantum optimization studies reveals significant variations in performance across different approaches and problem domains [12]. The benchmarking criteria for these comparisons include classical baselines (comparing against state-of-the-art classical solvers), quantum versus classical analog comparisons, wall-clock time reporting, solution quality versus computational effort, and quantum processing unit (QPU) resource usage [12].

Table 2: Experimental Performance of Quantum Optimization Approaches

| Implementation | Problem Type | Problem Size | Quantum Resources | Solution Quality | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBM QAOA [12] | Spin-glass, Max-Cut | 127 qubits | IBM 127-qubit system, modified QAOA ansatz | >99.5% approximation ratio for spin-glass | 1,500× improvement over quantum annealers for specific problems |

| Rigetti Multilevel QAOA [12] | Sherrington-Kirkpatrick graphs | 27,000 nodes via decomposition | Rigetti Ankaa-2 (82 qubits per subproblem) | >95% approximation ratio | Solves extremely large graphs via multilevel decomposition |

| Trapped-Ion Variational [12] | MAXCUT | 20 qubits | Trapped-ion quantum computer (32 qubits) | Approximation ratio < 10^-3 after 40 iterations | Resource-efficient with lower gate counts vs. QAOA |

| Neutral-Atom Hybrid [12] | Max k-Cut, Maximum Independent Set | 16 nodes | Neutral-atom quantum computer | Comparable to classical at low depths, exceeds at p=5 | Solves non-native combinatorial problems effectively |

Performance Analysis and Interpretation

The experimental data reveals several critical patterns in current quantum optimization capabilities. First, approximation ratios exceeding 95% demonstrate that quantum approaches can produce high-quality solutions for challenging combinatorial problems [12]. Second, problem size remains a limiting factor, with the most impressive scaling achieved through classical-quantum hybrid approaches that decompose massive problems (up to 27,000 nodes) into smaller subproblems solvable on current quantum devices [12]. Third, hardware constraints significantly impact performance, with two-qubit gate fidelity emerging as a particularly critical factor [13].

Recent hardware advances suggest rapid improvement across these dimensions. For instance, IonQ has achieved 99.99% two-qubit gate fidelity—considered a watershed milestone that dramatically reduces error correction overhead and brings fault-tolerant systems closer to realization [13]. Such improvements in baseline hardware performance directly enhance the practical utility of quantum optimization algorithms by increasing circuit depth and complexity that can be reliably executed.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Quantum Optimization

Standardized experimental methodologies are essential for rigorous evaluation and comparison of quantum optimization algorithms. This section outlines protocol frameworks for implementing and benchmarking quantum optimization approaches, with specific examples from recent experimental studies.

Quantum Optimization Workflow

The generalized workflow for quantum optimization experiments follows a structured pathway from problem formulation to solution refinement, incorporating both quantum and classical computational resources. The following Graphviz diagram illustrates this experimental workflow:

Implementation Protocols by Algorithm Type

Quantum Annealing Protocol: The experimental implementation of quantum annealing begins with problem encoding into a Hamiltonian whose ground state corresponds to the optimal solution. The system is initialized in the ground state of a simple initial Hamiltonian, followed by adiabatic evolution toward the problem Hamiltonian [10]. Critical parameters include annealing time, temperature, and spin-bath polarization. Success is measured by the probability of finding the ground state or by the approximation ratio achieved across multiple runs. Experimental implementations on D-Wave systems have demonstrated performance advantages for specific problem classes, with one study claiming "the world's first and only demonstration of quantum computational supremacy on a useful, real-world problem" in magnetic materials simulation [3].

QAOA Experimental Protocol: QAOA implementation follows a hybrid quantum-classical pattern with distinct stages [12] [10]. First, the combinatorial problem is encoded into a cost Hamiltonian. The quantum circuit is then constructed with parameterized layers alternating between the cost Hamiltonian and a mixer Hamiltonian. Each layer depth (parameter p) increases the solution quality at the cost of circuit complexity. The protocol involves iterative execution where: (1) the quantum processor samples from the parameterized circuit; (2) a classical optimizer adjusts parameters to minimize expected cost; and (3) the updated parameters are fed back into the quantum circuit. Experimental studies have implemented this protocol with p ranging from 1 to 16, with higher p values generally producing better solutions but requiring longer coherence times and higher gate fidelities [12].

VQE Implementation Framework: VQE focuses on estimating the ground state energy of molecular systems for drug development applications [10]. The protocol involves preparing a parameterized quantum state (ansatz) that represents the molecular wavefunction, measuring the expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian, and using classical optimization to minimize this expectation value. The algorithm is particularly suited to noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices as it can accommodate relatively shallow circuit depths and is inherently resilient to certain types of noise. Pharmaceutical researchers have utilized VQE for studying molecular interactions, with IonQ reporting a 20x speed-up in quantum-accelerated drug development and achievement of quantum advantage in specific chemistry simulations [13] [3].

Implementing quantum optimization experiments requires specialized hardware, software, and methodological resources. This section catalogues essential components for researchers designing quantum optimization studies in drug development and related fields.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Quantum Optimization Experiments

| Resource Category | Specific Solutions | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware Platforms | IBM Gate-based Systems (127-156 qubits) [12] | Digital quantum computation for QAOA and VQE algorithms |

| D-Wave Quantum Annealers (5,000+ qubits) [11] | Analog quantum optimization via adiabatic evolution | |

| Rigetti Ankaa-2 (82 qubits) [12] | Gate-based quantum processing with specialized ISWAP gates | |

| Trapped-Ion Systems (IonQ, 32+ qubits) [12] [13] | High-fidelity qubits with 99.99% gate fidelity for complex circuits | |

| Software Development Kits | Qiskit [14] | Quantum circuit construction, manipulation, and optimization |

| Tket [14] | Quantum compilation with efficient gate decomposition | |

| Braket [14] | Quantum computing service across multiple hardware providers | |

| Cirq [14] | Quantum circuit simulation and optimization for research | |

| Benchmarking Tools | Benchpress [14] | Comprehensive testing suite for quantum software performance |

| Quantum Volume [15] | Holistic metric for quantum computer performance | |

| Random Circuit Sampling [15] | Stress-test for quantum supremacy demonstrations | |

| Methodological Frameworks | Multilevel Decomposition [12] | Solving large problems by breaking into smaller subproblems |

| Error Mitigation Techniques [12] | Reducing noise impact on NISQ device outputs | |

| Hybrid Quantum-Classical Workflows [10] | Integrating quantum and classical resources for optimal performance |

Algorithm Selection Framework: Matching Problems to Quantum Solutions

Selecting the appropriate quantum optimization approach requires careful consideration of problem characteristics, hardware accessibility, and performance requirements. The following decision framework visualizes the algorithm selection process:

Application Guidelines for Drug Development

For drug development professionals, algorithm selection should align with specific molecular simulation and optimization tasks:

Molecular Configuration Optimization: VQE excels at determining ground state energies of molecular systems, crucial for understanding drug-target interactions and binding affinities [10]. Recent implementations have demonstrated practical advantages, with IonQ reporting quantum advantage in specific chemistry simulations relevant to pharmaceutical research [3].

Drug Compound Screening: QAOA can optimize the selection of compound combinations from large chemical libraries by formulating the screening process as a combinatorial selection problem. The parallel evaluation capability of superposition enables efficient searching of compound combinations based on multiple optimization criteria.

Clinical Trial Optimization: Quantum annealing approaches on D-Wave systems have demonstrated effectiveness for complex scheduling and logistics problems, which can be adapted to optimize patient grouping, treatment scheduling, and resource allocation in clinical trials [3].

Quantum optimization represents a rapidly advancing frontier in computational science with demonstrated potential to transform approaches to combinatorial problems in drug development and related fields. Current experimental data shows that quantum algorithms can achieve high approximation ratios (>95%) for challenging problem instances and tackle extremely large problem sizes (up to 27,000 nodes) through multilevel decomposition approaches [12].

The most successful implementations employ hybrid quantum-classical frameworks that leverage the respective strengths of both computational paradigms [12] [10] [16]. As hardware continues to improve—with two-qubit gate fidelities now exceeding 99.99% in leading systems [13]—the scope and scale of tractable problems will expand significantly.

For drug development researchers entering this field, the strategic approach involves: (1) identifying problem classes with clear potential for quantum advantage; (2) developing expertise in QUBO and Ising model formulation; (3) establishing partnerships with quantum hardware providers; and (4) implementing robust benchmarking against state-of-the-art classical approaches. As the field progresses toward fault-tolerant quantum systems capable of unlocking the full potential of quantum optimization, building methodological expertise and practical experience today positions research organizations at the forefront of this computational transformation.

Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) has emerged as a pivotal framework for quantum computing, particularly in the realm of combinatorial optimization. It serves as a common language, allowing complex real-world problems to be expressed in a form that is native to many quantum algorithms and hardware platforms, including quantum annealers and gate-model quantum computers. The QUBO model is defined by an objective function that is a quadratic polynomial over binary variables. Formally, the problem is to minimize the function ( f(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{x}^T Q \mathbf{x} ) for a given matrix ( Q ), where ( \mathbf{x} ) is a vector of binary decision variables [7]. This article provides a comparative guide to QUBO formulations and problem encoding techniques, detailing their performance against classical alternatives and outlining the experimental protocols used to benchmark them, with a special focus on applications relevant to drug development and life sciences research.

Understanding QUBO and Alternative Formulations

The process of transforming a complex problem into a QUBO is a critical first step. For quantum computers based on qubits, QUBO is the standard formulation. However, alternative models like Quadratic Unconstrained Integer Optimization (QUIO) have been developed for hardware that natively supports a larger domain of values, such as qudit-based quantum computers [17].

The Standard QUBO Formulation

In a QUBO problem, the goal is to find the binary vector ( \mathbf{x} ) that minimizes the cost function ( \mathbf{x}^T Q \mathbf{x} ), where the matrix ( Q ) is a square, upper-triangular matrix of real numbers that defines the problem's linear (diagonal) and quadratic (off-diagonal) terms. This model is equivalent to the Ising model used in physics, which operates on spin variables ( si \in {-1, +1} ), via a simple change of variable ( xi = (s_i + 1)/2 ) [7]. Many NP-hard problems, including all of Karp's 21 NP-complete problems, can be written in this form, making it exceptionally powerful [7].

QUIO: An Alternative for Qudit-Based Hardware

Quadratic Unconstrained Integer Optimization (QUIO) formulations represent an evolution of the QUBO model. While QUBO variables are binary, QUIO variables can represent integer values from zero up to a machine-dependent maximum [17]. A key advantage of this approach is that it often requires fewer decision variables to encode a given problem compared to a QUBO. This efficiency in representation can help preserve potential quantum advantage by minimizing the classical pre-processing overhead and more efficiently utilizing the capabilities of emerging qudit-based hardware [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Problem Formulations for Quantum Optimization

| Formulation | Variable Domain | Primary Hardware Target | Key Advantage | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QUBO | Binary {0, 1} |

Qubit-based (e.g., superconducting, trapped ions) | Universal model for NP-hard problems; well-studied [7]. | Can require many variables for complex problems. |

| QUIO | Integer {0, 1, ..., M} |

Qudit-based | Uses fewer variables for many problems; more direct encoding [17]. | Less mature hardware and software ecosystem. |

| Ising Model | Spin {-1, +1} |

Quantum Annealers (e.g., D-Wave) | Natural for physics-based applications [7]. | Requires transformation for many optimization problems. |

Performance Comparison: Quantum vs. Classical Solvers

Recent studies have directly benchmarked quantum algorithms solving QUBO formulations against state-of-the-art classical optimizers, providing tangible evidence of progress in the field.

Quantum Algorithm Outpaces Classical Solvers

A 2025 study by Kipu Quantum and IBM demonstrated that a tailored quantum algorithm could solve specific hard optimization problems faster than classical solvers like CPLEX and simulated annealing [18]. The experiments used IBM’s 156-qubit quantum processors and a algorithm called bias-field digitized counterdiabatic quantum optimization (BF-DCQO) to tackle higher-order unconstrained binary optimization (HUBO) problems, which can be rephrased as QUBOs [18].

The methodology involved:

- Problem Instances: 250 randomly generated hard instances of HUBO problems, designed with heavy-tailed distributions (Cauchy and Pareto) to create rugged optimization landscapes that are challenging for classical methods [18].

- Quantum Hardware: Runs on IBM’s Marrakesh and Kingston 156-qubit processors, which are noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices [18].

- Algorithmic Technique: The BF-DCQO algorithm uses counterdiabatic driving, which adds an extra term to the system's energy function to help the quantum state evolve more directly toward the optimal solution, avoiding high-energy barriers. The process also employed Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) filtering to focus only on the best 5% of measurement outcomes in each iteration [18].

- Classical Benchmarks: Compared against IBM's CPLEX solver (with 10 CPU threads) and a simulated annealing approach running on powerful classical hardware [18].

The results, summarized in the table below, showed a consistent quantum runtime advantage for these specific problem types, which model real-world tasks like portfolio selection and network routing [18].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of BF-DCQO vs. Classical Solvers on a Representative 156-Variable Problem

| Solver | Time to High-Quality Solution | Solution Quality (Approximation Ratio) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| BF-DCQO (Quantum) | ~0.5 seconds | High | Achieved comparable or better solution quality significantly faster [18]. |

| CPLEX (Classical) | 30 - 50 seconds | High (matched quantum quality) | Required substantially more time to match the quantum solution's quality [18]. |

| Simulated Annealing (Classical) | > ~1.5 seconds | High (matched quantum quality) | Also outperformed by the quantum method in runtime [18]. |

The Role of Benchmarking and "The Intractable Decathlon"

To objectively assess progress, the research community has developed standardized benchmarking frameworks. The Quantum Optimization Working Group, which includes members from IBM, Zuse Institute Berlin, and multiple universities, introduced the Quantum Optimization Benchmarking Library (QOBLIB) [19].

This "intractable decathlon" consists of ten optimization problem classes designed to be difficult for state-of-the-art solvers at relatively small problem sizes. The library provides:

- Model-Agnostic Benchmarks: Problems are presented in a way that allows any classical or quantum method to attempt a solution, not just those based on QUBO [19].

- Standardized Metrics: Researchers are encouraged to report achieved solution quality, total wall-clock time, and all computational resources used to enable fair comparisons [19].

- Reference Models: The library includes both Mixed-Integer Programming (MIP) and QUBO formulations of the problems, allowing researchers to study the overhead and complexity introduced by the encoding process itself [19].

This initiative underscores the importance of rigorous, model-independent benchmarking in the pursuit of demonstrable quantum advantage [19].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To ensure reproducible and meaningful results, experimental protocols in quantum optimization must be meticulously designed. The following workflow visualizes the general process of encoding and solving a problem on a quantum device, integrating elements from the cited studies [18] [19] [7].

Diagram 1: Quantum Optimization Workflow

Detailed Methodology for Key Experiments

The following table outlines the key components of a robust experimental protocol, as used in recent studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Components

| Item / Component | Function / Description | Example in Kipu/IBM Study [18] |

|---|---|---|

| Problem Instance Generator | Creates benchmark problems with known properties and difficulty. | Used heavy-tailed (Cauchy, Pareto) distributions to generate 250 hard HUBO instances. |

| Classical Pre-processor | Finds a good initial state for the quantum algorithm to refine. | Used fast simulated annealing runs to initialize the quantum system. |

| Quantum Algorithm | The core routine executed on the quantum processing unit (QPU). | Bias-field digitized counterdiabatic quantum optimization (BF-DCQO). |

| Error Mitigation Strategy | Techniques to combat noise in NISQ-era hardware. | Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) filtering retained only the best 5% of measurement results. |

| Classical Post-processor | Improves the raw solution from the QPU. | Applied simple local searches to clean up the final results. |

| Classical Benchmark Solver | Provides a performance baseline for comparison. | IBM CPLEX (with 10 threads) and a simulated annealing implementation. |

The Benchmarking Protocol

The QOBLIB proposes a rigorous protocol for comparative studies [19]:

- Problem Selection: Choose one or more problem classes from the "intractable decathlon" that are relevant to the target application (e.g., drug discovery).

- Formulation: Encode the problem using any desired model (MIP, QUBO, QUIO, or another novel formulation).

- Execution: Run the chosen algorithm (quantum or classical) on the problem instance, tracking all resources.

- Reporting: Submit the results using the QOBLIB template, which mandates reporting solution quality, wall-clock time, and computational resources used for both classical and quantum components [19].

This protocol ensures that claims of performance or advantage are based on a complete and transparent accounting of the computational effort.

For researchers in drug development and life sciences, engaging with quantum optimization requires familiarity with a set of core tools and resources.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools and Platforms

| Tool / Resource | Type | Purpose & Relevance | Key Features / Offerings |

|---|---|---|---|

| IBM Quantum Systems | Hardware Platform | Access to superconducting qubit processors for running optimization algorithms [18] [19]. | Processors like the 156-qubit "Marrakesh"; cloud access; Qiskit software framework. |

| Quantum Optimization Benchmarking Library (QOBLIB) | Software / Database | Provides standardized problems and a platform for comparing algorithm performance [19]. | The "intractable decathlon" of 10 problem classes; submission portal for results. |

| CPLEX Optimizer | Classical Software | A top-tier classical solver used as a performance benchmark for quantum algorithms [18]. | Efficient MIP and QUBO solver; used to establish classical baselines. |

| D-Wave Quantum Annealers | Hardware Platform | Specialized quantum hardware for solving optimization problems posed as QUBOs/Ising models [7]. | Native quantum annealing; used in applications like wireless network scheduling [7]. |

The following diagram maps the logical relationships between the key components in the quantum optimization research ecosystem, showing how different elements interact from problem definition to solution validation.

Diagram 2: Quantum Optimization Research Ecosystem

Application in Life Sciences: A Path to Quantum Value

In life sciences, the path to harnessing quantum computing involves a strategic approach [20]:

- Pinpoint the Value: Identify high-impact challenges like target discovery or clinical trial efficiency where quantum optimization could offer the greatest benefit.

- Build Strategic Alliances: Partner with quantum technology leaders to access cutting-edge hardware and expertise, as seen with collaborations between AstraZeneca and IonQ, and Boehringer Ingelheim and PsiQuantum [20].

- Invest in Human Capital: Cultivate multidisciplinary teams with expertise in computational biology, chemistry, and quantum computing.

- Future-proof Data Strategy: Establish a secure and scalable data infrastructure capable of handling the outputs of quantum simulations [20].

QUBO formulations and their alternatives, such as QUIO, represent fundamental building blocks for the future of quantum optimization. While recent experiments show promising runtime advantages for specific problems on current hardware, the field is maturing toward rigorous, standardized benchmarking through community-wide initiatives like the QOBLIB. For researchers in drug development and life sciences, engaging with these tools and methodologies now provides a pathway to leverage the evolving quantum computing landscape for tackling computationally intractable problems, from molecular simulation to clinical trial optimization.

In the rapidly evolving field of computational science, the quest for quantum advantage—the point where quantum computers outperform their classical counterparts on practical problems—represents a central focus of modern research. While classical optimization algorithms, powered by sophisticated hardware and decades of refinement, continue to excel across numerous domains, specific problem classes persistently resist efficient classical solution. These computationally intractable problems, characterized by exponential scaling of possible solutions and complex, rugged optimization landscapes, represent both a fundamental challenge to classical computing and a promising frontier for emerging quantum approaches [19] [21].

This guide systematically identifies and analyzes the problem classes where state-of-the-art classical methods encounter significant limitations, providing researchers with a structured framework for understanding where quantum optimization algorithms may offer complementary or superior capabilities. By examining problem characteristics, established classical performance boundaries, and emerging quantum strategies, we aim to inform strategic algorithm selection and highlight promising research directions at the quantum-classical frontier.

The Benchmarking Imperative in Optimization Research

Rigorous, model-independent benchmarking provides the essential foundation for comparing computational approaches across different paradigms. Traditional benchmarking efforts have often been algorithm- or model-dependent, limiting their utility for assessing potential quantum advantages. The recently introduced Quantum Optimization Benchmarking Library (QOBLIB) addresses this gap by establishing ten carefully selected problem classes, termed the "intractable decathlon," designed specifically to facilitate fair comparisons between quantum and classical optimization methods [19] [22].

This benchmarking initiative emphasizes problems that become challenging for classical solvers at relatively small instance sizes (from under 100 to approximately 100,000 variables), making them accessible to current and near-term quantum hardware while retaining real-world relevance [22]. The framework provides both Mixed-Integer Programming (MIP) and Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) formulations, standardized performance metrics, and classical baseline results, creating a vital infrastructure for objectively evaluating where classical methods struggle and quantum approaches may offer advantages [19].

Problem Classes Challenging Classical Methods

Higher-Order Unconstrained Binary Optimization (HUBO)

Problem Characteristics: HUBO problems extend beyond quadratic interactions to include higher-order relationships among variables, making them suitable for modeling complex real-world scenarios in portfolio selection, network routing, and molecule design [18].

Classical Limitations: The computational resources required to solve HUBO problems scale exponentially with problem size. For a representative 156-variable instance, IBM's CPLEX software required 30-50 seconds to achieve solution quality comparable to what a quantum method achieved in half a second, even while utilizing 10 CPU threads in parallel [18].

Quantum Approach: The Bias-Field Digitized Counterdiabatic Quantum Optimization (BF-DCQO) algorithm has demonstrated particular promise on these problems. By evolving a quantum system under special guiding fields that help maintain progress toward optimal states, this approach can circumvent local minima that trap classical solvers [18].

Table 1: Performance Comparison on HUBO Problems

| Solution Method | Problem Size (Variables) | Time to Solution | Approximation Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| BF-DCQO (Quantum) | 156 | 0.5 seconds | High |

| CPLEX (Classical) | 156 | 30-50 seconds | High |

| Simulated Annealing | 156 | >30 seconds | High |

Low Autocorrelation Binary Sequences (LABS)

Problem Characteristics: The LABS problem involves finding binary sequences with minimal autocorrelation, with applications in radar communications and cryptography [22].

Classical Limitations: Despite its simple formulation, the LABS problem becomes exceptionally difficult for classical solvers at relatively small scales. Instances with fewer than 100 variables in their MIP formulation can require disproportionately large computational resources, with the QUBO formulation often requiring over 800 variables due to increased complexity during transformation [22].

Quantum Approach: Quantum heuristics like the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) and variational approaches can navigate the complex energy landscape of LABS problems more efficiently by leveraging quantum tunneling effects to escape local minima [22].

Quadratic Assignment Problem (QAP)

Problem Characteristics: QAP represents a class of facility location problems where the goal is to assign facilities to locations to minimize total connection costs [21].

Classical Limitations: QAP is considered among the "hardest of the hard" combinatorial optimization problems. Finding even an ε-approximate solution has been proven to be NP-complete, and the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) is a special case of QAP [21]. Classical exact methods become computationally infeasible even for moderate-sized instances.

Quantum Approach: Quantum approaches using qubit-efficient encodings like Pauli Correlation Encoding (PCE) have shown promise on QAP instances. Recent research has enhanced PCE with QUBO-based loss functions and multi-step bit-swap operations to improve solution quality [21].

Molecular Simulation for Drug Discovery

Problem Characteristics: Predicting molecular properties, protein folding, and drug-target binding affinities requires simulating quantum mechanical systems with high accuracy [23] [20].

Classical Limitations: Classical computers struggle with the exponential scaling of quantum system simulation. Density Functional Theory (DFT) and other classical computational chemistry methods often lack the accuracy needed for modeling complex, dynamic molecular interactions, particularly for orphan proteins with limited experimental data [20].

Quantum Approach: Quantum computers naturally simulate quantum systems, offering potentially exponential speedups. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm has emerged as a leading method for estimating molecular ground states on near-term quantum hardware [23] [24].

Table 2: Molecular Simulation Challenge Scale

| Computational Challenge | Classical Method | Key Limitation | Quantum Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Calculation | Density Functional Theory | Accuracy trade-offs | Variational Quantum Eigensolver |

| Protein Folding Prediction | Molecular Dynamics | Timescale limitations | Quantum-enhanced sampling |

| Binding Affinity Prediction | Docking Simulations | Imprecise quantum effects | Quantum phase estimation |

| Molecular Property Prediction | QSAR Models | Limited training data | Quantum machine learning |

Diagram 1: Problem class characteristics and computational approaches

Multi-Dimensional Knapsack Problem (MDKP)

Problem Characteristics: MDKP extends the classical knapsack problem to multiple constraints, with applications in resource allocation, project selection, and logistics [21].

Classical Limitations: As the number of dimensions (constraints) increases, classical exact methods like branch-and-bound face exponential worst-case complexity. Approximation algorithms struggle to maintain solution quality while respecting all constraints [21].

Quantum Approach: Quantum annealing and gate-based approaches like QAOA can natively handle the complex constraint structure of MDKP through penalty terms in the objective function, potentially finding higher-quality solutions than classical heuristics for sufficiently large instances [21].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

Standardized Performance Metrics

To ensure fair comparisons between classical and quantum optimization methods, the research community has established standardized performance metrics:

- Time-to-Solution: Wall-clock time required to reach a target solution quality, carefully defined for quantum processors to exclude queueing time and include only circuit preparation, execution, and measurement phases [22].

- Approximation Ratio: The ratio between the solution quality found by the algorithm and the optimal (or best-known) solution [18].

- Success Probability: For stochastic algorithms (including most quantum approaches), the probability of finding a solution meeting quality thresholds across multiple runs [22].

- Resource Utilization: Comprehensive accounting of both classical and quantum resources consumed during computation [19].

Quantum Algorithm Experimental Design

Experimental protocols for evaluating quantum optimization algorithms must account for the unique characteristics of quantum hardware:

Circuit Compilation and Optimization: Quantum circuits must be compiled to respect the native gate set and connectivity constraints of target hardware. For example, IBM's heavy-hexagonal lattice requires careful qubit placement and swap network insertion to enable necessary interactions [18].

Error Mitigation Strategies: Given the noisy nature of current quantum processors, advanced error mitigation techniques are essential. These include Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE), dynamical decoupling, and measurement error mitigation [24].

Hybrid Quantum-Classical Workflows: Most practical quantum optimization approaches employ hybrid workflows where quantum processors evaluate candidate solutions while classical processors handle parameter optimization, as seen in VQE and QAOA implementations [10] [24].

Diagram 2: Hybrid quantum-classical optimization workflow

Table 3: Key Resources for Quantum Optimization Research

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| IBM Quantum Processors | Hardware | 156+ qubit superconducting quantum processors | Execution of quantum circuits for optimization algorithms [18] |

| QOBLIB Benchmark Suite | Software | Standardized problem instances across 10 optimization classes | Fair performance comparison between quantum and classical solvers [19] [22] |

| BF-DCQO Algorithm | Algorithm | Bias-field digitized counterdiabatic quantum optimization | Solving HUBO problems with enhanced convergence [18] |

| CVaR Filtering | Technique | Conditional Value-at-Risk filtering of quantum measurements | Focusing on best measurement outcomes to improve solution quality [18] |

| Pauli Correlation Encoding | Method | Qubit-efficient encoding for combinatorial problems | Solving larger problems with limited quantum resources [21] |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation | Error Mitigation | Extrapolating results to zero-noise limit | Improving accuracy on noisy quantum hardware [24] |

Classical optimization methods face fundamental limitations on specific problem classes characterized by exponential solution spaces, rugged optimization landscapes, and inherent quantum mechanical properties. The systematic identification and characterization of these challenging problem classes—including HUBO problems, LABS, QAP, molecular simulations, and MDKP—provides a crucial roadmap for targeting quantum optimization research efforts.

While classical solvers continue to excel across broad problem domains, the emerging evidence suggests that quantum approaches offer complementary capabilities on carefully selected problem instances. The development of standardized benchmarking frameworks like QOBLIB, coupled with advanced quantum algorithms and error mitigation strategies, enables researchers to precisely quantify both current performance gaps and potential quantum advantages.

For researchers and practitioners, this analysis underscores the importance of problem-aware algorithm selection and continued investigation of hybrid quantum-classical approaches. As quantum hardware continues to mature, the strategic targeting of classically challenging problem classes represents the most promising path toward practical quantum advantage in optimization.

The drug discovery and development process is characterized by significant financial investment, with costs ranging from $1-$3 billion and a typical timeline of 10 years alongside a 10% success rate [25]. This landscape creates a critical need for innovative computational approaches to enhance efficiency. Quantum optimization algorithms represent an emerging technological frontier with potential to revolutionize two fundamental aspects of pharmaceutical research: molecular docking and clinical trial design.

While classical computational methods, including artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), have made notable strides in these domains, they face inherent limitations. Classical approaches to molecular docking struggle with accurately simulating quantum effects in molecular interactions and navigating the vast complexity of biomolecular systems [26]. Similarly, in clinical trials, traditional methods often prove inadequate for optimizing complex logistical and analytical challenges such as site selection and cohort identification [27] [28].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of quantum algorithm performance against classical alternatives, presenting experimental data and detailed methodologies to offer researchers a comprehensive overview of current capabilities and future potential in this rapidly evolving field.

Quantum-Enhanced Molecular Docking

Performance Comparison Table

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies applying quantum and classical algorithms to molecular docking problems.

| Algorithm/Model | Problem Instance (Nodes) | Key Performance Metric | Experimental Setup | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digitized-Counterdiabatic QAOA (DC-QAOA) | 14 & 17 nodes (Largest published: 12-node) | Successfully found binding interactions representing anticipated exact solution; Computational times increased significantly with instance size. | Simulated quantum runs on a GPU cluster; Applied to the Max-Clique problem for molecular docking. | [29] |

| Hybrid QCBM–LSTM (Quantum–Classical) | N/A | 21.5% improvement in passing synthesizability and stability filters vs. classical LSTM; Success rate correlated ~linearly with qubit count. | 16-qubit processor for QCBM; Used to generate KRAS inhibitors; Validated with surface plasmon resonance & cell-based assays. | [30] |

| Quantum–Classical Generative Model | N/A | Two novel molecules (ISM061-018-2, ISM061-022) showed binding affinity to KRAS (1.4 μM) and inhibitory activity in cell-based assays. | Combined QCBM (16-qubit) with classical LSTM; 1.1M data point training set; 15 candidates synthesized & tested. | [30] |

| Classical AI/ML Models (Baseline) | N/A | Accelerates docking but struggles with precise energy calculations, quantum effects, and complex protein conformations. | Classical graph neural networks and transformer-based architectures. | [26] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) for Docking Researchers at Pfizer implemented a Digitized-Counterdiabatic QAOA (DC-QAOA) to frame molecular docking as a combinatorial optimization problem, specifically mapping it to the Max-Clique problem [29].

- Molecular Representation: The binding pose prediction between a drug (ligand) and a target protein was mapped onto a graph structure. The goal was to find the largest set of mutually compatible contact points (the maximum clique) between the molecules.

- Algorithm Execution: The DC-QAOA, a hybrid classical-quantum algorithm, was used to solve this Max-Clique problem. It leverages quantum superposition to explore multiple possible solutions simultaneously.

- Hardware & Simulation: The algorithm was executed via simulated quantum runs on a GPU cluster, handling instances of 14 and 17 nodes—reportedly larger than previously published instances [29].

- Warm-Starting: A "warm-starting" technique was employed, initializing the quantum algorithm with a solution from a classical preprocessor to reduce quantum operations and mitigate noise [29].

Protocol 2: Hybrid Quantum–Classical Generative Model for Inhibitor Design A separate study developed a hybrid quantum–classical model to design novel KRAS inhibitors, a historically challenging cancer target [30].

- Data Curation: A training set of ~1.1 million data points was compiled from known KRAS inhibitors, virtual screening of 100 million molecules, and algorithmically generated similar compounds [30].

- Model Architecture:

- Quantum Component: A 16-qubit Quantum Circuit Born Machine (QCBM) generated a prior distribution, leveraging quantum effects like entanglement.

- Classical Component: A classical Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network.

- Active Learning Cycle: The QCBM generated samples in every training epoch. These samples were validated and scored (e.g., for synthesizability or docking score) by a classical tool (Chemistry42). The reward value from this validation was used to continuously retrain and improve the QCBM [30].

- Experimental Validation: The top 15 generated candidates were synthesized and tested experimentally using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to measure binding affinity and cell-based assays to gauge biological efficacy [30].

Diagram 1: QAOA workflow for molecular docking. The process involves mapping the problem to a quantum circuit and using a classical optimizer in a hybrid loop [29].

Diagram 2: Hybrid quantum-classical generative model workflow. The model uses a quantum prior and classical validation in an active learning cycle [30].

Quantum Computing in Clinical Trial Design

Performance Comparison Table

The application of quantum computing to clinical trials is more nascent than molecular docking. The table below summarizes potential and early demonstrated impacts.

| Application Area | Quantum Algorithm | Proposed/Potential Advantage | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial Site Selection | Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) | Can analyze vast datasets (infrastructure, demographics, regulations) to identify optimal sites by considering multiple factors and constraints simultaneously. | Proof-of-concept analysis; outperforms manual or rule-based classical systems [28] [31]. |

| Cohort Identification | Quantum Feature Maps, Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs), Quantum GANs | Processes complex, high-dimensional patient data (EHRs, genomics) for better cohort identification; QGANs can generate high-quality synthetic data for control arms with less training. | Theoretical and early research stage [28] [31]. |

| Clinical Trial Predictions (Small Data) | Quantum Reservoir Computing (QRC) | Outperformed classical models (raw features & classical embeddings) in predictive accuracy and lower variability with small datasets (100-200 samples). | Proof-of-concept case study by Merck, Amgen, Deloitte, and QuEra [32]. |

| Drug Effect Simulation (PBPK/PD) | Quantum Machine Learning (QML) | Potential to more accurately simulate drug pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics by handling complex biological data and differential equations beyond classical capabilities. | Theoretical modeling stage [28] [31]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Quantum Reservoir Computing (QRC) for Small-Data Predictions A consortium including Merck, Amgen, and QuEra conducted a proof-of-concept case study using QRC to address a common pain point in clinical R&D: making reliable predictions from small datasets, common in early-stage trials or rare diseases [32].

- Data Preparation: Deloitte orchestrated a data pipeline to simulate small-data scenarios. Starting from a larger molecular dataset, they created subsets of varying sizes (e.g., 100, 200, 800 samples) using clustering to preserve the underlying data distribution [32].

- Quantum Embeddings: Molecular features were encoded into control parameters (e.g., atomic detunings) and loaded into QuEra's neutral-atom quantum processing unit (QPU). The system evolved under Rydberg interactions, and the measurements produced high-dimensional "quantum embeddings" [32].

- Classical Readout: A key feature of QRC is that only the classical readout layer (e.g., a random forest model) was trained on these quantum embeddings, avoiding the challenges of training the quantum system itself [32].

- Comparison: The pipeline's performance was compared against classical models using raw features and classical models using kernel-transformed embeddings (e.g., Gaussian RBF) [32].

Protocol 2: Quantum Optimization for Trial Site Selection While detailed experimental protocols for site selection are less common, proposed methodologies involve using quantum optimization algorithms like QAOA [28] [31].

- Problem Formulation: The challenge of selecting the best clinical trial sites is framed as a complex optimization problem. Factors include site infrastructure, staff resources, local patient demographics, disease incidence, environmental factors, and regulatory requirements [28] [31].

- Constraint Modeling: These diverse factors are translated into a set of constraints and objectives for an optimization algorithm.

- Algorithm Execution: A quantum optimization algorithm, such as QAOA, is used to find the best combination of sites that satisfies the most constraints and optimizes the objectives (e.g., maximizing potential recruitment rate). This process can explore the solution space of possible site combinations more efficiently than classical solvers for certain problem types [28] [31].

Diagram 3: Quantum reservoir computing workflow for small data predictions. The quantum system creates enriched data representations for a classical model [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Platforms

The table below details essential software, hardware, and platforms used in the featured experiments, forming a foundational toolkit for researchers in this domain.

| Tool/Platform Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| QuEra Neutral-Atom QPU | Quantum Hardware | Provides the physical quantum system for running quantum algorithms or, as in QRC, generating complex data embeddings. | Used in the QRC case study for creating quantum embeddings from molecular data [32]. |

| GPU Clusters | Classical Hardware | Simulates quantum algorithms and processes results; critical for hybrid quantum-classical workflows in the NISQ era. | Used to simulate the DC-QAOA runs for molecular docking [29]. |

| Chemistry42 | Classical Software | A classical AI-powered platform for computer-aided drug design; validates molecules for synthesizability, stability, and docking score. | Used as a reward function and validator in the hybrid QCBM-LSTM model for KRAS inhibitors [30]. |

| VirtualFlow 2.0 | Classical Software | An open-source platform for virtual drug screening; enables ultra-large-scale docking against protein targets. | Used to screen 100 million molecules from the Enamine REAL library to enrich the training set for the generative model [30]. |

| STONED/SELFIES | Classical Algorithm | Generates structurally similar molecular analogs; helps expand chemical space for training generative models. | Used to generate 850,000 similar compounds from known KRAS inhibitors for training data [30]. |

| QCBM (Quantum Circuit Born Machine) | Quantum Algorithm | A quantum generative model that learns complex probability distributions to generate new, valid molecular structures. | Served as the quantum prior in the hybrid model to propose novel KRAS inhibitor candidates [30]. |

| QAOA/DC-QAOA | Quantum Algorithm | A hybrid algorithm designed to find approximate solutions to combinatorial optimization problems, such as the Max-Clique problem in docking. | Applied to molecular docking to find optimal binding configurations [29]. |

| NDSB-201 | NDSB-201, CAS:15471-17-7, MF:C8H11NO3S, MW:201.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 5-Amino-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxamide | 5-Amino-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxamide|CAS 50427-77-5 | High-purity 5-Amino-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxamide for cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Comparative Analysis & Future Directions

The experimental data indicates that quantum algorithms show promise in specific, well-defined niches within drug development. In molecular docking, hybrid quantum-classical models have demonstrated an ability to generate novel, experimentally validated drug candidates [30] and handle problem instances of increasing size [29]. The 21.5% improvement in passing synthesizability filters and the generation of two promising KRAS inhibitors provide tangible, early evidence of potential value [30].

In clinical trial design, the advantages are more prospective but equally compelling. Quantum Reservoir Computing has shown a clear, demonstrated advantage over classical methods in low-data regimes, a common challenge in clinical development [32]. Furthermore, quantum optimization offers a theoretically more efficient path to solving complex logistical problems like site selection that are currently managed with suboptimal classical tools [27] [28].

The primary limitations remain hardware-related. Current quantum devices operate in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, characterized by qubits that are prone to error [29] [28]. This makes hybrid approaches, which leverage the strengths of both classical and quantum computing, the most viable and practical strategy today. Future research will focus on scaling qubit counts, improving error correction, and further refining these hybrid algorithms to unlock more substantial quantum advantages.

Quantum Optimization in Practice: Algorithms, Techniques, and Real-World Problem Solving

In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, variational quantum algorithms have emerged as promising candidates for achieving practical quantum advantage. Gate-based quantum optimization techniques, particularly the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) and the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), represent hybrid quantum-classical approaches designed to leverage current quantum hardware despite its limitations. A comprehensive benchmarking framework evaluating these techniques reveals they face significant challenges in solution quality, computational speed, and scalability when applied to well-established NP-hard combinatorial problems [33].

Recent research has focused on enhancing these algorithms' performance and reliability. The integration of Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) as an aggregation function, replacing the traditional expectation value, has demonstrated substantial improvements in convergence speed and solution quality for combinatorial optimization problems [34]. This advancement is particularly relevant for applied fields such as drug discovery, where quantum optimization promises to revolutionize molecular simulations and complex process optimization [20].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of QAOA, VQE, and their CVaR-enhanced variants, examining their methodological foundations, performance characteristics, and practical applications with emphasis on experimental protocols and empirical results.

Algorithm Fundamentals and Methodologies

Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA)

QAOA is a hybrid algorithm designed for combinatorial optimization problems on gate-based quantum computers. The algorithm operates through a parameterized quantum circuit that alternates between two unitary evolution operators:

- Phase Separation Operator: Encodes the problem's cost function through a unitary operator ( UP(\alphaj) = e^{-i\alphaj HP} ), where ( H_P ) is the problem Hamiltonian.

- Mixing Operator: Facilitates exploration of the solution space through ( UM(\betaj) = e^{-i\betaj HM} ), where ( H_M ) is a mixing Hamiltonian [35] [36].

The quantum circuit consists of multiple layers (( p )), with the number of layers determining the algorithm's approximation quality. For a combinatorial optimization problem formulated as a Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO), the goal is to find the binary variable assignment that minimizes the cost function ( C(x) = x^T Q x ). This classical cost function is mapped to a quantum Hamiltonian via the Ising model, whose ground state corresponds to the optimal solution [36].

The algorithm begins by initializing qubits in a uniform superposition state. The parameterized quantum circuit applies sequences of phase separation and mixing operators, generating a trial state ( |\Psi(\vec{\alpha}, \vec{\beta})| ). Measurements of this state produce candidate solutions, while a classical optimizer adjusts parameters ( \vec{\alpha} ) and ( \vec{\beta} ) to minimize the expectation value ( \langle \Psi(\vec{\alpha}, \vec{\beta}) | H_P | \Psi(\vec{\alpha}, \vec{\beta}) \rangle ) [35].

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE)

VQE is a hybrid algorithm primarily employed for ground state energy calculations in quantum systems, with significant applications in quantum chemistry and material science. The method combines a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) with classical optimization to find the lowest eigenvalue of a given Hamiltonian:

- Cost Function: ( C(\theta) = \langle \Psi(\theta) | O | \Psi(\theta) \rangle ), where ( O ) is the observable of interest, typically a molecular Hamiltonian.

- Ansatz Selection: The choice of parameterized quantum circuit ( |\Psi(\theta)| ) is crucial, with common approaches including the Unitary Coupled-Cluster (UCC) ansatz for chemistry applications [36].

For quantum chemistry problems like molecular simulation, the electronic Hamiltonian is transformed via Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev encoding to represent fermionic operations as qubit operations. The classical optimizer then adjusts parameters ( \theta ) to minimize the energy expectation value [36].

Unlike QAOA, which was designed specifically for combinatorial optimization, VQE excels at continuous optimization problems, particularly finding ground states in molecular systems. This makes it especially valuable for drug discovery applications where accurate molecular simulations are critical [10] [23].

CVaR-Enhanced Variants

The CVaR enhancement represents a significant improvement for variational quantum optimization algorithms. Traditional approaches minimize the expectation value of the cost Hamiltonian, which can be inefficient for classical optimization problems with diagonal Hamiltonians [34].

CVaR, or Conditional Value-at-Risk, focuses on the tail of the probability distribution of measurement outcomes. For a parameter ( \alpha \in [0, 1] ), CVaR is the conditional expectation of the lowest ( \alpha )-fraction of outcomes. This approach discards poor measurement results and focuses optimization on the best samples, leading to:

- Faster convergence to better solutions

- Smoother objective functions with fewer local minima

- Improved approximation ratios with the same quantum resources [34] [37]

Empirical studies demonstrate that lower ( \alpha ) values (e.g., ( \alpha = 0.5 )) produce smoother objective functions and better performance compared to the standard expectation value approach (( \alpha = 1.0 )) [37]. This enhancement can be applied to both QAOA and VQE, though it shows particular promise for combinatorial optimization problems addressed by QAOA.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Benchmarking Framework and Problem Sets

A systematic benchmarking framework evaluates quantum optimization techniques against established NP-hard combinatorial problems, including:

- Multi-Dimensional Knapsack Problem (MDKP)

- Maximum Independent Set (MIS)

- Quadratic Assignment Problem (QAP)

- Market Share Problem (MSP) [33]

Experimental results from simulated quantum environments and classical solvers provide insights into feasibility, optimality gaps, and scalability across these problem classes [33].

Table 1: Algorithm Specifications and Resource Requirements

| Algorithm | Primary Application Domain | Key Components | Resource Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| QAOA | Combinatorial Optimization | Phase separation unitary, Mixing unitary | Circuit depth scales with layers (p); performance limited at low depth [35] |

| VQE | Quantum Chemistry, Ground State Problems | Problem-specific ansatz (e.g., UCCSD), Molecular Hamiltonian | Qubit count depends on molecular size and basis set; requires robust parameter optimization [36] |

| CVaR-QAOA | Enhanced Combinatorial Optimization | CVaR aggregation, Traditional QAOA components | Same quantum resources as QAOA; improved performance with optimal α selection [34] [37] |

| CVaR-VQE | Enhanced Ground State Estimation | CVaR aggregation, Traditional VQE components | Focuses optimization on best measurement outcomes; particularly beneficial for noisy hardware [34] |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Across Problem Types

| Algorithm | Problem Type | Key Performance Metrics | Limitations and Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| QAOA | MaxCut on Erdos-Renyi graphs | Approximation ratio improves with circuit depth; outperforms classical at sufficient depth [37] | Requires exponential time for linear functions at low depth; scalability constraints [35] |

| VQE | H2 Molecule Ground State | Accurate ground energy estimation with UCCSD ansatz; viable on current hardware [36] | Accuracy limited by ansatz expressibility; barren plateaus in parameter optimization [36] |

| CVaR-QAOA | Combinatorial Optimization Benchmarks | Faster convergence; better solution quality versus standard QAOA [34] [37] | Optimal α parameter selection problem; performance gain varies by problem instance [37] |

| QAOA | Linear Functions | Exponential measurements required when p < n (number of coefficients) [35] | Practical quantum advantage requires p ≥ n; current hardware limitations [35] |

Recent innovations like CNN-CVaR-QAOA integrate convolutional neural networks with CVaR to optimize QAOA parameters, demonstrating superior performance on Erdos-Renyi random graphs across various configurations [37]. This hybrid machine-learning approach addresses the challenging parameter optimization problem in variational quantum algorithms.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Implementation Workflows

Quantum-Classical Hybrid Algorithm Workflow

The experimental implementation of variational quantum algorithms follows a consistent hybrid workflow as illustrated above. For different algorithm variants, specific components change:

QAOA Experimental Protocol:

- Problem Encoding: Formulate combinatorial problem as QUBO or Ising model

- Circuit Construction: Implement alternating layers of phase separation and mixing unitaries

- Parameter Initialization: Choose initial parameters ( \vec{\alpha}, \vec{\beta} ) (often randomly)

- Quantum Execution: Run parameterized circuit on quantum processor or simulator

- Measurement: Collect multiple measurement outcomes for statistical analysis

- Classical Optimization: Use gradient-based or gradient-free optimizers to update parameters

- Convergence Check: Repeat until parameter convergence or maximum iterations [35] [36]

VQE for Molecular Systems:

- Hamiltonian Formation: Compute molecular Hamiltonian in second quantization using STO-3G basis set

- Qubit Mapping: Transform fermionic operators to qubit operators via Jordan-Wigner transformation

- Ansatz Preparation: Initialize with Hartree-Fock reference state and apply UCCSD ansatz

- Energy Estimation: Measure expectation value of molecular Hamiltonian

- Parameter Optimization: Employ classical optimizers like BFGS to minimize energy [36]

CVaR Enhancement Methodology

The CVaR enhancement modifies the standard workflow by changing how measurement outcomes are aggregated:

- Sample Collection: Run quantum circuit multiple times to obtain a set of measurement outcomes

- Sorting by Energy: Sort outcomes according to their objective function value (energy)

- CVaR Calculation: Select the best α-fraction (e.g., lowest 25%) of outcomes and compute their mean value

- Optimization: Use this CVaR value as the cost function for classical optimization [34]

Experimental studies systematically vary the α parameter to determine optimal values for specific problem classes, with lower α values generally providing better performance despite increased stochasticity [37].

Advanced Enhancement Strategies

Integrated Machine Learning Approaches

Recent research demonstrates that machine learning integration significantly enhances variational quantum algorithms:

- CNN-CVaR-QAOA: Combines convolutional neural networks with CVaR for parameter prediction, reducing optimization overhead [37]

- Parameter Initialization Strategies: Neural networks predict optimal initial parameters, avoiding random initialization and accelerating convergence [37]

- Ansatz Architecture Search: Machine learning methods automatically design efficient parameterized quantum circuits tailored to specific problem instances [37]

These integrated approaches address key bottlenecks in variational quantum algorithms, particularly the challenging parameter optimization problem that often leads to barren plateaus or convergence to local minima.

Resource Optimization Techniques