Benchmarking Quantum Optimizers: A Performance Evaluation for Noisy VQE Landscapes in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive performance evaluation of classical optimizers for Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithms operating under the finite-shot sampling noise of Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices.

Benchmarking Quantum Optimizers: A Performance Evaluation for Noisy VQE Landscapes in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive performance evaluation of classical optimizers for Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithms operating under the finite-shot sampling noise of Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational challenges of noisy optimization landscapes, methodologies of resilient algorithms, troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls like barren plateaus and false minima, and a rigorous validation of top-performing optimizers like CMA-ES and iL-SHADE based on recent large-scale benchmarks. The findings offer critical guidance for deploying reliable quantum simulations in molecular modeling and drug discovery.

The Noisy VQE Challenge: Understanding Optimization Landscapes and the Barren Plateau Phenomenon

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithmic framework for harnessing the potential of Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) computers. As we navigate the current era characterized by quantum processors containing up to 1,000 qubits that remain susceptible to environmental noise and decoherence, VQE offers a practical approach by combining quantum state preparation with classical optimization [1]. This hybrid quantum-classical algorithm is particularly valuable for quantum chemistry applications, where it enables the computation of molecular ground-state energies—a fundamental challenge with significant implications for drug discovery, materials design, and catalyst development [2] [3].

The core principle of VQE relies on the variational method of quantum mechanics, where a parameterized ansatz (trial wavefunction) is prepared on a quantum device, and its parameters are iteratively optimized using classical computing resources to minimize the expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian [1]. This approach strategically allocates computational workloads: the quantum processor handles the exponentially challenging task of representing quantum states, while classical optimizers tune the parameters. Despite its conceptual elegance, practical implementations face substantial challenges from noisy evaluations, barren plateaus in optimization landscapes, and the limited coherence times of current hardware [4] [5]. This comparative analysis examines the performance of optimization strategies for VQE under realistic NISQ constraints, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for algorithm selection.

Experimental Methodologies for Benchmarking VQE Optimizers

Molecular Systems and Active Space Selection

Benchmarking studies typically employ well-characterized molecular systems to enable controlled comparisons across optimization methods. The hydrogen molecule (Hâ‚‚) serves as a fundamental test case due to its simple electronic structure and modest resource requirements. In comprehensive statistical benchmarking, Hâ‚‚ is studied at its equilibrium bond length of 0.74279 Ã… within a Complete Active Space (CAS) framework designated as CAS(2,2), indicating two active electrons and two active orbitals [6]. This configuration provides a balanced description of bonding and antibonding interactions while maintaining computational tractability. The cc-pVDZ basis set is commonly employed, offering a reasonable compromise between accuracy and computational cost [6]. For scaling tests, researchers progressively examine more complex systems such as the 25-body Ising model and the 192-parameter Hubbard model, which provide insights into algorithm performance across increasing Hilbert space dimensions [4].

Noise Models and Quantum Estimators

Faithful performance evaluation requires incorporating realistic noise models that mirror the imperfections of NISQ devices. Benchmarking protocols systematically examine optimizer behavior under various quantum noise conditions, including:

- Idealized (noiseless) conditions: Establishing theoretical performance baselines

- Stochastic noise models: Emulating statistical sampling errors from finite measurements

- Decoherence channels: Incorporating phase damping, depolarizing, and thermal relaxation processes [6]

These noise models capture the dominant error sources in physical quantum hardware, where gate fidelities typically range from 95-99% for two-qubit operations and coherence times remain limited [1]. The distortion of optimization landscapes under these noise conditions fundamentally alters optimizer performance characteristics, transforming smooth convex basins into rugged, distorted surfaces that challenge convergence [4].

Performance Metrics and Evaluation Criteria

Comparative analyses employ multiple quantitative metrics to assess optimizer effectiveness:

- Accuracy: Final energy error relative to exact diagonalization or full configuration interaction (FCI) benchmarks, with chemical accuracy threshold of 1 kcal/mol (approximately 1.6 mHa)

- Convergence reliability: Success rate across multiple random initializations

- Computational efficiency: Number of function evaluations required to reach convergence

- Robustness: Performance stability across different noise types and intensities [6] [4]

Statistical significance is ensured through multiple independent runs with randomized initial parameters, typically ranging from 50-100 repetitions per optimizer configuration [6].

Comparative Performance Analysis of VQE Optimizers

Systematic Benchmarking of Optimization Approaches

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Primary VQE Optimizers Under Quantum Noise

| Optimizer | Algorithm Class | Final Energy Accuracy | Evaluation Count | Noise Robustness | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BFGS | Gradient-based | High | Low | Moderate | Well-conditioned problems with analytic gradients [6] |

| SLSQP | Gradient-based | Medium | Low | Low | Noise-free simulations [6] |

| Nelder-Mead | Gradient-free | Medium | Medium | Medium | Moderate-noise regimes [6] |

| Powell | Gradient-free | Medium | Medium | Medium | Shallow circuits with limited noise [6] |

| COBYLA | Gradient-free | Medium-high | Low-medium | High | Low-cost approximations in noisy environments [6] |

| iSOMA | Global metaheuristic | High | Very high | Medium-high | Complex landscapes with adequate budget [6] |

| CMA-ES | Evolutionary | High | High | High | Noisy, rugged landscapes [4] |

| iL-SHADE | Evolutionary | High | High | High | High-dimensional problems with noise [4] |

Large-Scale Benchmarking Insights

Recent large-scale studies evaluating over fifty metaheuristic algorithms reveal distinct performance patterns across different problem classes and noise conditions. Evolutionary strategies, particularly CMA-ES and iL-SHADE, demonstrate consistent superiority across multiple benchmark problems from the Ising model to larger Hubbard systems [4] [7]. These algorithms maintain robustness despite the landscape distortions induced by finite-shot sampling and hardware noise, whereas widely used optimizers such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Genetic Algorithms (GA), and standard Differential Evolution (DE) variants experience significant performance degradation under noisy conditions [4].

The exceptional performance of evolutionary approaches stems from their inherent population-based methodologies, which provide resilience against local minima and noise-induced traps. Specifically, CMA-ES adapts its search distribution to the topology of the objective function, enabling effective navigation of deceptive regions in rugged landscapes [4]. This adaptability proves particularly valuable in noisy VQE optimization, where the true global minimum may be obscured by stochastic fluctuations.

Table 2: Niche Optimizers for Specialized VQE Applications

| Optimizer | Strength | Limitation | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGA-VQE | Resilience to statistical noise, reduced measurements | Limited track record on diverse molecules | Hardware experiments with high measurement noise [5] |

| Simulated Annealing (Cauchy) | Global exploration capability | Slow convergence in smooth regions | Multi-modal landscapes where gradient methods stagnate [4] |

| Harmony Search | Balance of exploration/exploitation | Parameter sensitivity | Medium-scale problems with limited budget [4] |

| Symbiotic Organisms Search | Biological inspiration | Computational overhead | Complex electronic structure problems [4] |

The VQE Optimization Workflow

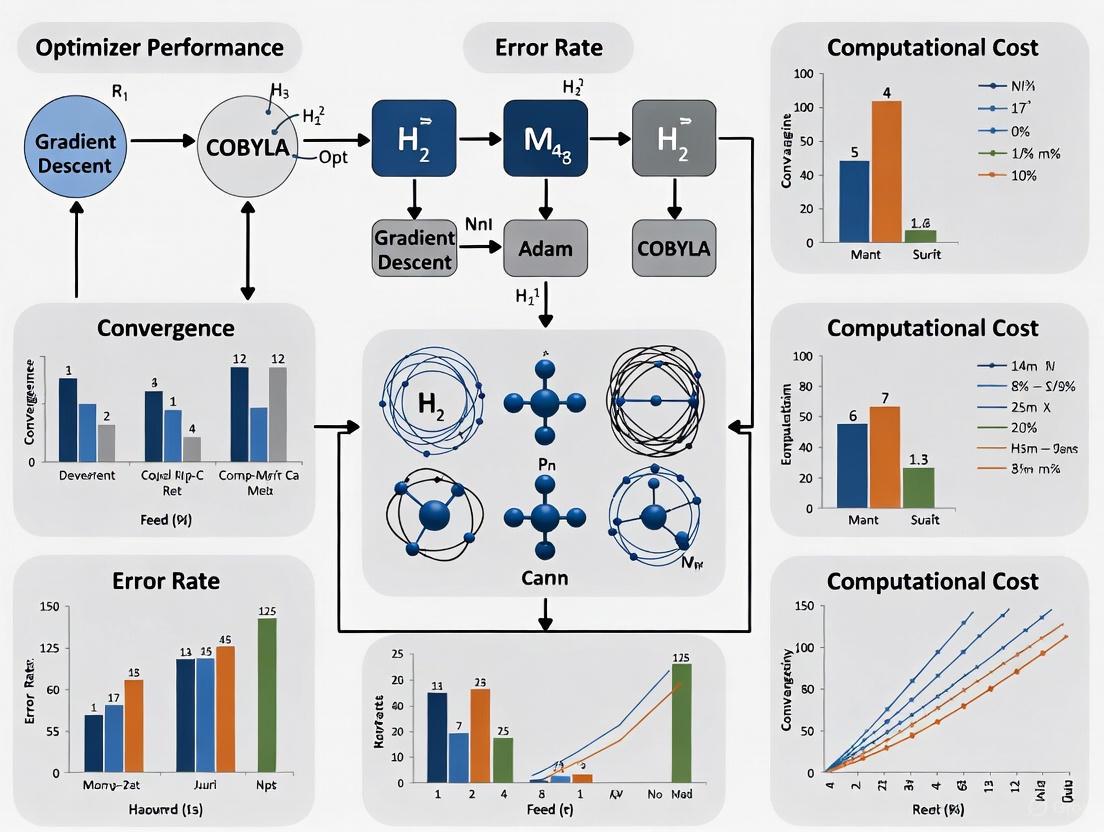

The following diagram illustrates the complete hybrid quantum-classical workflow for VQE optimization, highlighting the critical role of the classical optimizer in navigating noisy landscapes:

VQE Optimization Workflow in Noisy Environments

This workflow illustrates the iterative feedback loop between quantum and classical components. The quantum processor prepares and measures parameterized ansatz states, while the classical optimizer navigates the noisy cost landscape. Quantum noise sources (decoherence, gate errors, measurement noise) directly impact the energy evaluations, creating the rugged optimization landscapes that challenge classical optimizers.

Advanced Strategies: Adaptive Ansätze and Error Mitigation

Adaptive VQE Formulations

Beyond optimizer selection, algorithmic innovations such as adaptive ansätze construction offer promising pathways for improving VQE performance. The ADAPT-VQE protocol builds system-tailored ansätze through iterative operator selection from a predefined pool, significantly reducing circuit depth and parameter counts [5]. However, the original formulation requires computationally expensive gradient calculations for each pool operator, necessitating thousands of noisy quantum measurements [5].

Recent innovations address these limitations through measurement-efficient strategies. The Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE) demonstrates improved resilience to statistical noise by eliminating gradient requirements during operator selection [5]. This approach has been successfully implemented on a 25-qubit error-mitigated quantum processing unit (QPU) for solving the 25-body Ising model, though hardware noise still produces energy inaccuracies requiring subsequent error mitigation [5].

Integrated Error Mitigation Techniques

Practical VQE implementations typically incorporate error mitigation strategies to enhance result quality without the overhead of full quantum error correction. Promising approaches include:

- Zero-noise extrapolation (ZNE): Artificially amplifying circuit noise and extrapolating to the zero-noise limit, potentially enhanced with neural networks for improved fitting accuracy [8]

- Symmetry verification: Exploiting conservation laws inherent in quantum systems to detect and discard erroneous measurements [1]

- Probabilistic error cancellation: Reconstructing ideal quantum operations as linear combinations of noisy implementable operations [1]

These techniques inevitably increase measurement overhead—typically by 2x to 10x or more depending on error rates—creating fundamental trade-offs between accuracy and computational resources [1]. Research indicates that symmetry verification often provides optimal performance for chemistry applications, while ZNE excels for optimization problems with fewer inherent symmetries [1].

Essential Research Toolkit for VQE Experiments

Table 3: Essential Computational Resources for VQE Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Computing Frameworks | MindQuantum [8] | Algorithm development and simulation | Quantum chemistry simulations with built-in noise models |

| Classical Optimizers | CMA-ES, iL-SHADE [4] | Parameter optimization | Noisy VQE landscapes with rugged topology |

| Error Mitigation Tools | Zero-noise extrapolation, symmetry verification [1] | Noise reduction without full error correction | NISQ hardware experiments with moderate error rates |

| Molecular Modeling | CAS(2,2) active space [6] | Electronic structure representation | Balanced accuracy-efficiency for benchmark studies |

| Ansatz Architectures | UCCSD [6], hardware-efficient [8], ADAPT-VQE [5] | Wavefunction parameterization | Problem-specific circuit design |

| Noise Modeling | Depolarizing, thermal relaxation, phase damping [6] | Realistic device simulation | Pre-deployment performance validation |

| ER proteostasis regulator-1 | ER proteostasis regulator-1, MF:C18H22N2O3, MW:314.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Mevalonic acid lithium salt | Mevalonic acid lithium salt, CAS:2618458-93-6, MF:C6H11LiO4, MW:154.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The rigorous benchmarking of optimization methods for VQE reveals a complex performance landscape where no single algorithm dominates across all scenarios. Gradient-based methods like BFGS offer computational efficiency in well-behaved regions but display vulnerability to noise-induced landscape distortions [6]. Evolutionary strategies, particularly CMA-ES and iL-SHADE, demonstrate superior robustness for noisy, high-dimensional problems but demand substantial evaluation budgets [4]. Gradient-free local optimizers such as COBYLA provide practical compromises for resource-constrained applications [6].

The optimal optimizer selection depends critically on specific research constraints: computational budget, target accuracy, noise characteristics, and molecular system complexity. For drug development professionals seeking to leverage current NISQ devices, a tiered approach is recommended—beginning with COBYLA for initial explorations and progressing to CMA-ES for refined calculations where resources permit. As quantum hardware continues to evolve with improving gate fidelities and error mitigation strategies, the performance hierarchy of classical optimizers will likely shift, necessitating ongoing benchmarking on realistic chemical applications [9] [3].

The trajectory of quantum computing for chemical applications suggests that practical advantages for industrial drug discovery may require further hardware scaling and algorithmic refinement. Current estimates indicate that modeling biologically significant systems like cytochrome P450 enzymes may require 100,000 or more physical qubits [3]. Nevertheless, the systematic optimization strategies detailed in this comparison provide researchers with evidence-based guidelines for maximizing the utility of current NISQ devices through informed algorithm selection and appropriate error mitigation.

The Impact of Finite-Shot Sampling Noise on Cost Function Evaluation

In the pursuit of quantum advantage on near-term devices, Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) have emerged as a leading paradigm. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), a cornerstone VQA, aims to find the ground-state energy of molecular systems by combining quantum state preparation and measurement with classical optimization [10]. A fundamental yet often underestimated challenge in this framework is finite-shot sampling noise, which arises from the statistical uncertainty inherent in estimating expectation values from a limited number of quantum measurements. This noise fundamentally distorts the cost function landscape, creating spurious minima and misleading optimizers [11]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how different classical optimizers perform under the duress of this noise, offering experimental data and protocols to inform research in fields such as drug development where molecular energy calculations are crucial.

Understanding Finite-Shot Noise and Its Consequences

The cost function in VQE is the expectation value of a Hamiltonian, ( C(\bm{\theta}) = \langle \psi(\bm{\theta}) | \hat{H} | \psi(\bm{\theta}) \rangle ), which is variationally bounded from below by the true ground state energy. In practice, this ideal cost is inaccessible; we only have an estimator, ( \bar{C}(\bm{\theta}) ), derived from a finite number of measurement shots, ( N{\text{shots}} ) [11]: [ \bar{C}(\bm{\theta}) = C(\bm{\theta}) + \epsilon{\text{sampling}} ] where ( \epsilon{\text{sampling}} ) is a zero-mean random variable, typically Gaussian, with variance proportional to ( \sigma^2/N{\text{shots}} ) [11].

This sampling noise leads to two critical problems:

- Stochastic Violation of the Variational Bound: The estimated energy ( \bar{C}(\bm{\theta}) ) can fall below the true ground state energy ( E_0 ), violating the fundamental variational principle and creating the illusion of a better solution [11] [12].

- Winner's Curse: In optimization, the best-performing parameter set in a population is often one that benefited from favorable noise, leading to a biased estimator that appears better than it truly is [11] [12].

Visualizations of energy landscapes reveal that smooth, convex basins in noiseless settings deform into rugged, multimodal surfaces as finite-shot noise increases. This distortion explains why gradient-based methods struggle, as the true curvature signal becomes comparable to the noise amplitude [10] [12].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between finite-shot noise and its detrimental effects on the VQE optimization process.

Comparative Performance of Optimizers

The performance of an optimizer in a noisy VQE landscape is determined by its robustness to spurious minima and its ability to navigate flat, gradient-starved regions. The table below summarizes the key findings from large-scale benchmarks comparing numerous optimization algorithms.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Classical Optimizers in Noisy VQE Landscapes

| Optimizer Class | Representative Algorithms | Performance Under Noise | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-Based | Gradient Descent, SLSQP, BFGS [11] | Diverges or stagnates [11] | Fails when cost curvature is comparable to noise amplitude [11] |

| Metaheuristic (Standard) | PSO, GA, standard DE variants [10] | Performance degrades sharply with noise [10] | Struggles with rugged, deceptive landscapes [10] |

| Metaheuristic (Adaptive) | CMA-ES, iL-SHADE [11] [10] | Most effective and resilient [11] [10] | Implicitly averages noise; avoids winner's curse via population mean tracking [11] |

| Other Robust Metaheuristics | Simulated Annealing (Cauchy), Harmony Search, Symbiotic Organisms Search (SOS) [10] | Show robustness to noise [10] | Alternative effective strategies for global search [10] |

The superior performance of adaptive metaheuristics like CMA-ES and iL-SHADE is attributed to their population-based approach. They mitigate the "winner's curse" not by trusting the best individual in a generation, but by tracking the population mean, which provides a less biased estimate of progress [11] [12]. Furthermore, their adaptive nature allows them to efficiently explore the high-dimensional parameter space without relying on precise, and often noisy, local gradient information.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for benchmarking, this section outlines the core experimental methodologies from the cited studies.

Benchmarking Protocol for Optimizer Resilience

A comprehensive benchmarking study evaluated over fifty metaheuristic algorithms using a structured, three-phase protocol to ensure rigorous and scalable comparisons [10].

Table 2: Three-Phase Benchmarking Protocol for Optimizer Evaluation

| Phase | Objective | Description | System Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Initial Screening | Identify top-performing algorithms from a large pool | Initial tests performed on the 1D Ising model, which presents a well-characterized multimodal landscape [10]. | Not specified |

| Phase 2: Scaling Tests | Evaluate how performance scales with system complexity | The most promising algorithms from Phase 1 were tested on increasingly larger systems to assess scalability [10]. | Up to 9 qubits [10] |

| Phase 3: Convergence Test | Validate performance on a large, complex problem | The finalists were evaluated on a large-scale Fermi-Hubbard model, a system known for its rugged, nonconvex energy landscape [10]. | 192 parameters [10] |

Key Experimental Details:

- Cost Evaluation: The loss function ( \ell_{\bm{\theta}}(\rho, O) = \text{Tr}[\rho(\bm{\theta}) O] ) was estimated with finite sampling, where the sampling variance is of order ( 1/\sqrt{N} ) for ( N ) shots [10].

- Landscape Visualization: A crucial part of the methodology involved visualizing the cost landscape of models like the 1D Ising and Fermi-Hubbard to qualitatively understand optimizer behavior in the presence of noise [10].

- Noise Modeling: The primary noise considered was finite-shot sampling noise, modeled as additive Gaussian noise: ( \epsilon{\text{sampling}} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2/N{\text{shots}}) ) [11].

Problem and Ansatz Selection

The benchmarks were designed to test optimizer performance across diverse physical systems and ansatz architectures, confirming the generality of the findings.

- Physical Models: Benchmarking was conducted on quantum chemistry Hamiltonians (Hâ‚‚, Hâ‚„ chain, LiH in both full and active spaces) and condensed matter models (1D Ising and Fermi-Hubbard) [11] [10].

- Ansatz Types: The performance insights were shown to generalize across different circuit types, including problem-inspired ansatzes like the truncated Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz (tVHA) and hardware-efficient circuits like the TwoLocal ansatz [11].

The workflow below summarizes the key components and process of a robust VQE experiment designed to account for finite-shot noise.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section catalogues essential resources and strategies identified in the research for conducting reliable VQE experiments in the presence of finite-shot noise.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Strategies for Noisy VQE

| Category | Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Resilient Optimizers | CMA-ES, iL-SHADE [11] [10] | Adaptive, population-based algorithms identified as most effective for navigating noisy, rugged landscapes. |

| Bias Correction Strategy | Population Mean Tracking [11] [12] | Technique to counter the "winner's curse" by using the population mean, rather than the best individual, to guide optimization. |

| Model Systems | Hâ‚‚, Hâ‚„, LiH, 1D Ising, Fermi-Hubbard [11] [10] | Well-characterized benchmark models for initial testing and validation of optimization strategies. |

| Software & Libraries | Python-based Simulations of Chemistry Framework (PySCF) [11] | Used for obtaining molecular integrals in quantum chemistry simulations. |

| Ansatz Strategies | Truncated VHA (tVHA), Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA) [11] | Different ansatz designs for testing the generality of optimizer performance. |

| Advanced Strategies | ADAPT-VQE [13], Variance Regularization [14] | Specialized methods (adaptive ansatz construction, modified cost function) to further mitigate noise and trainability issues. |

| Biotin-PEG(4)-SS-Azide | Biotin-PEG(4)-SS-Azide, MF:C26H47N7O7S3, MW:665.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| TAMRA azide, 6-isomer | TAMRA azide, 6-isomer, MF:C28H28N6O4, MW:512.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The empirical evidence demonstrates that finite-shot sampling noise is a critical factor that systematically distorts VQE cost landscapes, necessitating a careful co-design of optimizers and ansatzes. While standard gradient-based methods often fail in this regime, adaptive metaheuristics, particularly CMA-ES and iL-SHADE, have proven to be the most robust and effective choice across a wide range of molecular and condensed matter systems. For researchers in drug development and quantum chemistry, adopting these optimizers, along with strategies like population mean tracking, provides a more reliable path for obtaining accurate molecular energies on today's noisy quantum devices. Future work will need to integrate mitigation techniques for other hardware noise sources alongside the management of sampling noise.

In the pursuit of quantum advantage on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) have emerged as a leading computational paradigm. These hybrid quantum-classical algorithms leverage parameterized quantum circuits optimized by classical routines to solve problems in quantum simulation, optimization, and machine learning. However, a significant obstacle threatens the scalability of these approaches: the barren plateau (BP) phenomenon. First identified by McClean et al., barren plateaus describe regions in the optimization landscape where the gradient of the cost function vanishes exponentially with increasing system size [15]. When algorithms encounter these regions, the training process requires an exponentially large number of measurements to determine a productive optimization direction, effectively eliminating any potential quantum advantage [16].

The implications of barren plateaus extend across the variational quantum computing landscape, impacting the performance of the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA), among others. As system sizes increase, the prevalence of these flat regions poses fundamental challenges to the trainability of parameterized quantum circuits. Research has revealed that barren plateaus are not monolithic; they manifest through different mechanisms including ansatz design, cost function choice, and hardware noise. Understanding these variants and their effects on optimizer performance is crucial for developing scalable quantum algorithms [17]. This guide systematically compares how different VQA architectures and optimization strategies perform when confronting barren plateaus, providing researchers with actionable insights for algorithm selection and design.

Understanding Barren Plateaus: Typology and Mechanisms

Conceptual Framework and Definitions

Barren plateaus arise in the optimization landscapes of variational quantum algorithms when the variance of the cost function gradient vanishes exponentially as a function of the number of qubits, n. Formally, for a parameterized quantum circuit with parameters θ and cost function C(θ), a barren plateau occurs when Var[∂ₖC(θ)] ∈ O(1/bâ¿) for b > 1, where ∂ₖC(θ) denotes the partial derivative with respect to the k-th parameter [15]. This exponential decay means that resolving a productive descent direction requires a number of measurements that grows exponentially with system size, making optimization practically infeasible beyond small-scale problems.

The barren plateau phenomenon can be understood through the lens of concentration of measure in high-dimensional spaces. As the number of qubits increases, the Hilbert space expands exponentially, causing smoothly varying functions to concentrate sharply around their mean values. This geometric intuition is formalized by Levy's Lemma, which states that the value of a sufficiently smooth function on a high-dimensional sphere is approximately constant over most of its volume [15]. In the context of VQAs, the cost function landscape flattens dramatically, with gradients becoming exponentially small almost everywhere.

Classification of Barren Plateau Types

Recent research has identified several distinct types of barren plateaus, each with characteristic landscape features and implications for optimization:

Table: Classification of Barren Plateau Types

| Type | Landscape Characteristics | Primary Cause | Impact on Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Everywhere-Flat BPs | Uniformly flat landscape across entire parameter space | Deep random circuits, hardware noise | Gradient-based and gradient-free optimizers equally affected |

| Localized-Dip BPs | Mostly flat with sharp minimum in small region | Specific cost function constructions | Narrow gorge makes locating minimum difficult |

| Localized-Gorge BPs | Flat with narrow trench leading to minimum | Certain ansatz architectures | Optimization may progress once in gorge but entry is rare |

| Noise-Induced BPs (NIBPs) | Exponential concentration due to decoherence | Hardware noise accumulating with circuit depth | Affects even shallow circuits with linear depth scaling |

Statistical analysis using Gaussian function models has revealed that while everywhere-flat BPs present uniform difficulty across the entire landscape, localized-dip BPs contain steep gradients in exponentially small regions, creating "narrow gorges" that are challenging to locate [17]. Empirical studies of common ansätze, including hardware-efficient and random Pauli ansätze, suggest that everywhere-flat BPs dominate in practical implementations, though all variants present serious scalability challenges [17].

Fundamental Causes of Barren Plateaus

Ansatz Expressibility and Randomness

The architecture of parameterized quantum circuits plays a crucial role in the emergence of barren plateaus. Early work established that randomly initialized, deep hardware-efficient ansatzes exhibit barren plateaus when their depth grows sufficiently with system size [15]. This occurs because deep random circuits approximate unitary 2-designs, causing the output states to become uniformly distributed over the Hilbert space. When circuits form either exact or approximate 2-designs, the expected value of the gradient is zero, and its variance decays exponentially with qubit count [15].

The expressibility of an ansatz—its ability to generate states covering a large portion of the Hilbert space—correlates strongly with susceptibility to barren plateaus. Highly expressive ansätze that can explore large regions of the unitary group are more prone to gradient vanishing than constrained, problem-specific architectures. This creates a fundamental tension in ansatz design: sufficient expressibility is needed to represent solution states, but excessive expressibility induces trainability problems [16].

Cost Function Choice and Locality

The structure of the cost function itself significantly influences the presence and severity of barren plateaus. Cerezo et al. established a crucial distinction between global and local cost functions and their impact on trainability [18]. Global cost functions, which involve measurements of all qubits simultaneously (e.g., the overlap with a target state ⟨ψ|O|ψ⟩ where O has global support), typically induce barren plateaus even for shallow circuits. In contrast, local cost functions, constructed as sums of terms each acting on few qubits, can maintain polynomially vanishing gradients and remain trainable for circuits with O(log n) depth [18].

This phenomenon can be understood through the lens of operator entanglement: global measurements generate more entanglement than local ones, leading to faster concentration of the cost function landscape. The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between circuit depth, cost function locality, and the emergence of barren plateaus:

Hardware Noise and NISQ Limitations

In realistic computational environments, hardware noise presents an additional source of barren plateaus. Wang et al. demonstrated that noise-induced barren plateaus (NIBPs) occur when local Pauli noise accumulates throughout a quantum circuit [19]. For circuits with depth growing linearly with qubit count, the gradient vanishes exponentially in the number of qubits, regardless of ansatz choice or cost function structure [19].

NIBPs are particularly concerning for NISQ applications because they affect even circuits specifically designed to avoid other types of barren plateaus. The noise channels cause the output state to converge exponentially quickly to the maximally mixed state, with the cost function concentrating around its value for this trivial state. This mechanism is conceptually distinct from noise-free barren plateaus and cannot be addressed solely through clever parameter initialization or ansatz design [19].

Comparative Analysis of Barren Plateau Mitigation Strategies

Local versus Global Cost Functions

Empirical studies consistently demonstrate the advantage of local cost functions for maintaining trainability. In a landmark study, Cerezo et al. provided both theoretical bounds and numerical evidence showing that global cost functions lead to exponentially vanishing gradients, while local variants maintain polynomially vanishing gradients for shallow circuits [18].

Table: Comparison of Global vs. Local Cost Functions

| Characteristic | Global Cost Functions | Local Cost Functions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Scaling | Exponential vanishing | Polynomial vanishing | |||||||

| Trainable Circuit Depth | Constant depth | O(log n) depth | |||||||

| Measurement Overhead | Exponential in n | Polynomial in n | |||||||

| Operational Meaning | Direct relevance to task | Indirect but bounded by global cost | |||||||

| Example | 1 - | ⟨0 | ψ⟩ | ² | 1 - 1/n ∑ᵢ ⟨ψ | 0⟩⟨0 | ᵢ | ψ⟩ |

The practical implications of this distinction are substantial. In quantum autoencoder applications, replacing global cost functions with local alternatives transformed an otherwise untrainable model into a scalable implementation [18]. Numerical simulations up to 100 qubits confirmed that local cost functions avoid the narrow gorge phenomenon—exponentially small regions of low cost value—that plagues global cost functions and hinders optimizers from locating minima [18].

Adaptive and Problem-Tailored Ansätze

Beyond cost function design, strategic ansatz construction offers promising pathways for mitigating barren plateaus. The ADAPT-VQE algorithm exemplifies this approach by dynamically growing an ansatz through gradient-informed operator selection [20]. This method constructs problem-tailored circuits that avoid excessively expressive, BP-prone regions of parameter space while maintaining sufficient flexibility to represent solution states.

ADAPT-VQE operates through an iterative process where at each step, the algorithm selects the operator with the largest gradient magnitude from a predefined pool, adding it to the circuit with the parameter initialized to zero. This methodology provides two key advantages: (1) an intelligent parameter initialization strategy that consistently outperforms random initialization, and (2) the ability to "burrow" toward solutions even when encountering local minima by progressively deepening the circuit [20]. The workflow of this adaptive approach can be visualized as follows:

Comparative studies demonstrate that adaptive algorithms like ADAPT-VQE significantly outperform static ansätze in challenging chemical systems where Hartree-Fock initializations provide poor approximations to ground states [20]. By construction, these approaches navigate around barren plateau regions rather than attempting to optimize within them.

Impact on Gradient-Free Optimization Methods

A common misconception suggests that gradient-free optimization methods might circumvent barren plateau problems. However, rigorous analysis demonstrates that gradient-free optimizers are equally affected by barren plateaus [21]. The fundamental issue lies not in the optimization algorithm itself, but in the statistical concentration of cost function values across the parameter landscape.

Arrasmith et al. proved that in barren plateau landscapes, cost function differences are exponentially suppressed, meaning that gradient-free optimizers cannot make informed decisions about parameter updates without exponential precision [21]. Numerical experiments with Nelder-Mead, Powell, and COBYLA algorithms confirmed that the number of shots required for successful optimization grows exponentially with qubit count, mirroring the scaling behavior of gradient-based approaches [21].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Benchmarking Approaches

To facilitate fair comparison between different mitigation strategies, researchers have developed standardized benchmarking protocols for assessing barren plateau susceptibility. These typically involve:

Gradient Variance Measurement: Calculating the variance of cost function gradients across random parameter initializations for increasing system sizes. Exponential decay indicates a barren plateau [15].

Cost Function Concentration Analysis: Measuring the concentration of cost values around their mean for random parameter choices, with exponential concentration suggesting trainability issues [16].

Trainability Threshold Determination: Identifying the critical circuit depth at which gradients become unresolvable with polynomial resources for different ansatz architectures [18].

These methodologies enable quantitative comparison of different approaches and provide practical guidance for algorithm selection based on problem size and available computational resources.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methodological Components

Table: Experimental Components for Barren Plateau Research

| Component | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz | Provides realistic NISQ-inspired circuit architecture | Layered rotations with entangling gates [15] |

| Unitary Coupled Cluster | Chemistry-specific ansatz with physical constraints | UCCSD for molecular systems [20] |

| Local Cost Functions | Maintain trainability for moderate system sizes | Sum of local observables rather than global measurements [18] |

| Gradient Measurement | Quantifies landscape flatness | Parameter shift rules or finite difference methods [16] |

| Adaptive Ansatz Construction | Dynamically grows circuits to avoid BPs | ADAPT-VQE with operator pools [20] |

| Boc-NH-PEG12-CH2CH2COOH | Boc-NH-PEG12-CH2CH2COOH, CAS:1415981-79-1, MF:C32H63NO16, MW:717.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Boc-L-Lys(N3)-OH (CHA) | Boc-L-Lys(N3)-OH (CHA), CAS:2098497-30-2, MF:C17H33N5O4, MW:371.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The study of barren plateaus remains an active area of research with significant implications for the scalability of variational quantum algorithms. Current evidence suggests that no single solution completely eliminates the problem across all application domains, but strategic combinations of local cost functions, problem-inspired ansätze, and adaptive circuit construction can extend the trainable regime to practically relevant system sizes.

The most successful approaches share a common philosophy: leveraging problem-specific structure to constrain the exploration of Hilbert space, thereby avoiding the uniform sampling that leads to exponential concentration. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, the interplay between device capabilities, algorithmic design, and optimization strategies will determine the ultimate scalability of variational quantum algorithms for drug development and other industrial applications.

For researchers navigating this complex landscape, the current evidence recommends: (1) preferring local over global cost functions when possible, (2) incorporating domain knowledge through problem-specific ansätze rather than defaulting to hardware-efficient approaches, and (3) considering adaptive algorithms like ADAPT-VQE for challenging problems where conventional optimizers fail. Through continued development of both theoretical understanding and practical mitigation strategies, the quantum computing community continues to expand the boundaries beyond which barren plateaus undermine quantum advantage.

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithms represent a promising pathway for quantum simulation on near-term hardware, yet their performance is critically dependent on the effectiveness of classical optimizers. This guide provides a comparative analysis of optimizer performance within the challenging context of VQE energy landscapes, which transition from smooth, convex basins in noiseless simulations to distorted and rugged multimodal surfaces under realistic, noisy conditions. We synthesize experimental data from a comprehensive benchmark study of over fifty metaheuristic algorithms, detailing their resilience to noise-induced landscape distortions. The findings identify a select group of optimizers, including CMA-ES and iL-SHADE, that consistently demonstrate robustness, enabling more reliable convergence in VQE tasks crucial for computational chemistry and drug development.

Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) are a leading approach for harnessing the potential of current noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) computers. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), a cornerstone VQA application, is particularly relevant for researchers in quantum chemistry and drug development, as it aims to find the ground-state energy of molecular systems—a critical step in understanding molecular structure and reaction dynamics. The VQE hybrid approach uses a quantum computer to prepare and measure a parameterized quantum state, while a classical optimizer adjusts these parameters to minimize the expectation value of the Hamiltonian, effectively searching for the ground state energy.

A central, and often debilitating, challenge in this framework is the performance of the classical optimizer. The optimization landscape is the hyper-surface defined by the cost function (energy) over the parameter space. In theoretical, noiseless settings, these landscapes can be relatively well-behaved. However, under realistic conditions involving finite-shot noise, hardware imperfections, and other decoherence effects, the landscape undergoes a significant transformation. As noted in recent research, "Landscape visualizations revealed that smooth convex basins in noiseless settings become distorted and rugged under finite-shot sampling" [4]. This distortion explains the frequent failure of standard gradient-based local methods and creates a pressing need to identify optimizers capable of navigating these pathological terrains.

Experimental Methodology for Benchmarking Optimizers

To objectively compare optimizer performance, a rigorous, multi-phase experimental protocol is essential. The following methodology, adapted from a large-scale benchmark study, provides a template for evaluating optimizers in the context of noisy VQE landscapes [4].

Benchmarking Phases

The evaluation was conducted in three distinct phases to ensure robustness and scalability:

- Initial Screening: A broad performance screening of over fifty metaheuristic algorithms was conducted on a fundamental Ising model. This phase aimed to filter out poorly performing optimizers before more resource-intensive testing.

- Scaling Tests: The most promising algorithms from the first phase were tested on progressively larger problems, scaling up to nine qubits. This assessed how optimizer performance degrades with increasing problem size and complexity.

- Convergence on Complex Models: The final phase evaluated the top performers on a more chemically relevant system, specifically a 192-parameter Hubbard model, to verify performance on a large, complex problem mimicking real-world applications.

Noise and Landscape Characterization

A critical component of the methodology was the explicit incorporation of noise. Landscapes were visualized and analyzed under both ideal (noiseless) and realistic (finite-shot) conditions. This direct visualization of the transition from smooth to rugged landscapes provided the explanatory link for why many widely used optimizers fail in practical settings.

The diagram below illustrates the high-level experimental workflow for evaluating optimizer performance under noisy conditions.

Comparative Performance Data

The large-scale benchmark revealed significant disparities in how optimization algorithms cope with noise-induced landscape distortions. The following tables summarize the key quantitative findings, providing a clear comparison of optimizer performance across different test models and conditions.

Table 1: Top-Performing Optimizers in Noisy VQE Landscapes [4]

| Optimizer | Full Name | Performance on Ising Model | Performance at Scale (9 Qubits) | Performance on Hubbard Model (192-parameter) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES | Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy | Consistently superior | Robust performance degradation | Highest convergence reliability |

| iL-SHADE | Improved Linear Population Size Reduction in SHADE | Consistently superior | Robust performance degradation | High convergence reliability |

| Simulated Annealing (Cauchy) | Simulated Annealing with Cauchy visiting distribution | Robust | Good scaling behavior | Competitive results |

| Harmony Search | Harmony Search Algorithm | Robust | Effective | Showed robustness |

| Symbiotic Organisms Search | Symbiotic Organisms Search Algorithm | Robust | Effective | Showed robustness |

Table 2: Performance Degradation of Widely Used Optimizers Under Noise [4]

| Optimizer | Full Name | Performance in Noiseless Setting | Performance Under Finite-Shot Noise | Primary Cause of Failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization | Effective | Sharp degradation | Sensitive to rugged, multimodal landscapes |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm | Effective | Sharp degradation | Poor performance in complex, noisy landscapes |

| Standard DE variants | Standard Differential Evolution | Effective | Sharp degradation | Lack of robustness to noise-induced distortions |

Visualizing Landscape Distortion and Its Impact

The core challenge in optimizing noisy VQEs is fundamentally visual: the search space becomes pathologically complex. In noiseless simulations, the parameter landscape for many model systems may exhibit a single, smooth, convex basin of attraction guiding the optimizer to the global minimum. The introduction of finite-shot noise and hardware imperfections radically distorts this topography.

This transformation can be conceptualized as a transition from a single, smooth basin to a rugged, multimodal surface. The global minimum remains, but it is now hidden among a plethora of local minima, sharp ridges, and flat plateaus (a phenomenon known as "barren plateaus"). This ruggedness directly explains the failure of many popular optimizers. Gradient-based methods become trapped in local minima or fail to make progress on plateaus, while population-based methods like PSO and GA can prematurely converge to suboptimal regions of the parameter space. The resilience of algorithms like CMA-ES and iL-SHADE lies in their ability to adapt their search strategy dynamically, effectively balancing exploration and exploitation to navigate this distorted terrain.

The following diagram models the logical impact of noise on the optimization landscape and the corresponding response of robust versus non-robust optimizers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers seeking to implement or validate these findings, the following table details the essential computational "reagents" and their functions in the study of VQE landscape optimization.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for VQE Optimizer Benchmarking

| Item Name | Type/Class | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Ising Model | Computational Model | A fundamental spin model used for initial, rapid screening of optimizer performance on a well-understood problem. |

| Hubbard Model | Computational Model | A more complex, chemically relevant model (e.g., 192-parameter) used for final-stage testing to validate performance on problems closer to quantum chemistry applications. |

| Finite-Shot Noise Simulator | Software Tool | Emulates the statistical noise inherent in real quantum hardware due to a finite number of measurement shots (repetitions), crucial for realistic landscape distortion. |

| CMA-ES Algorithm | Optimization Algorithm | A robust, evolution-strategy-based optimizer identified as a top performer for navigating distorted, noisy landscapes. |

| iL-SHADE Algorithm | Optimization Algorithm | An improved differential evolution algorithm that adapts its parameters, showing consistent robustness across different noisy VQE problems. |

| Landscape Visualization Toolkit | Analysis Software | A suite of tools for generating and visualizing energy landscapes across the parameter space, enabling direct observation of smooth vs. rugged topography. |

| 2-Hydroxybenzonitrile | 2-Hydroxybenzonitrile, CAS:69481-42-1, MF:C7H5NO, MW:119.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Nitrobenzaldehyde semicarbazone | 2-Nitrobenzaldehyde semicarbazone, CAS:16604-43-6, MF:C8H8N4O3, MW:208.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The performance of the classical optimizer is not merely an implementation detail in the VQE stack; it is a decisive factor in the algorithm's practical utility. As this comparison guide demonstrates, the distortion of VQE landscapes under realistic noise conditions necessitates a careful selection of the optimization engine. The experimental data clearly shows that while widely used optimizers like PSO and GA degrade sharply, a subset of algorithms, notably CMA-ES and iL-SHADE, possess the inherent robustness required for these challenging tasks. For researchers in drug development and quantum chemistry, adopting these resilient optimizers can lead to more stable and reliable VQE simulations, ultimately accelerating the discovery process on near-term quantum hardware. The continued development of optimization strategies that explicitly account for landscape distortion will be critical to unlocking the full potential of variational quantum algorithms.

Stochastic Variational Bound Violation and the 'Winner's Curse' Statistical Bias

The pursuit of reliable optimization represents a significant challenge in quantum computation, particularly for Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) methods operating on real-world noisy quantum hardware. VQEs employ a hybrid quantum-classical approach where a parameterized quantum circuit prepares a trial state, and a classical optimizer adjusts these parameters to minimize the expectation value of a target Hamiltonian, typically aiming to find a molecular system's ground state energy. However, this process is fundamentally complicated by the presence of finite-shot sampling noise, which arises from the statistical uncertainty in estimating expectation values through a limited number of quantum measurements. This noise distorts the true cost landscape, creating false local minima and, critically, induces a phenomenon known as the "winner's curse" [12]. This statistical bias causes the best-selected parameters during optimization to appear superior due to fortunate noise realizations rather than genuine performance, leading to an overestimation of performance—a violation of the variational bound—and misleading optimization trajectories [12]. This article objectively compares classical optimizer performance within this challenging context, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies to guide algorithm selection for robust VQE applications in fields like drug development.

Theoretical Foundation: Winner's Curse and Bound Violation

The Statistical Origin of the Winner's Curse

The winner's curse, a term originally from auction theory, describes a systematic overestimation of effect sizes for results ascertained through a thresholding or selection process [22] [23]. In the context of VQE optimization, it manifests when the classical optimizer, acting on noisy cost function evaluations, preferentially selects parameters for which the noise artifactually lowers the energy estimate. The optimizer is effectively "cursed" because it exploits these statistical fluctuations, mistaking them for true improvements [24].

Mathematically, in genetic association studies (which face an analogous statistical problem), the asymptotic expectation for the observed effect size (\beta{Observed}) given the true effect size (\beta{True}) and standard error (\sigma) under a significance threshold (c) is derived from a truncated normal distribution [22]: [ E(\beta{Observed}; \beta{True}) = \beta{True} + \sigma {{\phi({{{\beta{True}}\over{\sigma}}-c}) - \phi({{{-\beta{True}}\over{\sigma}}-c})} \over {\Phi({{{\beta{True}}\over{\sigma}}-c}) + \Phi({{{-\beta_{True}}\over{\sigma}}-c})}} ] where (\phi) and (\Phi) are the standard normal density and cumulative distribution functions, respectively [22]. This formula explicitly quantifies the upward bias inherent in the selection process.

Stochastic Variational Bound Violation

The direct consequence of the winner's curse in VQE is the stochastic violation of the variational bound [12]. The variational principle guarantees that the estimated energy from any trial state should be greater than or equal to the true ground state energy. However, finite-shot sampling noise can create false minima that appear below the true ground state energy. When an optimizer converges to such a point, it violates the theoretical bound, and any reported performance is illusory, stemming from estimator variance rather than a genuine physical effect [12]. Landscape visualizations confirm that smooth, convex basins in noiseless settings become distorted and rugged under finite-shot sampling, explaining the failure of optimizers that cannot distinguish true from false minima [4] [12].

Experimental Comparison of Optimizers

Methodologies for Benchmarking

To ensure a fair and rigorous comparison, recent studies have employed a multi-phase, sieve-like benchmarking procedure on a range of quantum chemistry Hamiltonians and models [4] [12] [25].

Benchmark Problems: Algorithms are tested on a series of problems of increasing complexity:

- Ising Model: A simple 1D spin chain with nearest-neighbor interactions, defined by the Hamiltonian ( H = -\sum{i=1}^{n-1} \sigmaz^{(i)} \sigma_z^{(i+1)} ), used for initial screening [25].

- Quantum Chemistry Hamiltonians: Systems including Hâ‚‚, Hâ‚„, and LiH, analyzed in both full and active spaces, to evaluate performance on scientifically relevant problems [12].

- Fermi-Hubbard Model: A strongly correlated electron model with up to 192 parameters, used for final convergence and scaling tests [4].

Noise Implementation: The key experimental factor is the inclusion of finite-shot noise, simulated by adding stochastic noise to the exact cost function evaluations to mimic the statistical uncertainty of real quantum hardware measurements [12].

Performance Metrics: Optimizers are judged based on:

- Final Convergence Accuracy: The proximity of the final energy to the true ground state.

- Consistency and Resilience: The ability to avoid catastrophic failures and winner's curse-induced bound violations across multiple runs.

- Convergence Speed: The number of cost function evaluations required to reach a satisfactory solution.

Comparative Performance Data

The following tables summarize the performance of various optimizer classes based on the reported experimental data.

Table 1: Optimizer Performance Classification based on Benchmark Studies [4] [12]

| Performance Tier | Optimizer Class | Representative Algorithms | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most Resilient | Adaptive Metaheuristics | CMA-ES, iL-SHADE | Consistently outperform others; implicit noise averaging; robust to landscape distortions. |

| Robust | Other Effective Metaheuristics | Simulated Annealing (Cauchy), Harmony Search, Symbiotic Organisms Search | Show resilience to noise, though may converge slower than top performers. |

| Variable/Degrading | Widely Used Heuristics | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Genetic Algorithm (GA), standard Differential Evolution (DE) | Performance degrades sharply with noise; prone to becoming trapped in false minima. |

| Unreliable | Gradient-Based Local Methods | Simultaneous Perturbation Stochastic Approximation (SPSA), L-BFGS, COBYLA | Struggle as cost curvature becomes comparable to noise amplitude; likely to diverge or stagnate. |

Table 2: Quantitative Convergence Results on the Hubbard Model (192 parameters) [4]

| Optimizer | Final Energy Error (Hartree) | Convergence Rate | Resilience to Winner's Curse |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES | ~10â»âµ | >95% | High (due to population mean tracking) |

| iL-SHADE | ~10â»âµ | >90% | High |

| PSO | ~10â»Â³ | <60% | Low |

| SPSA | Varies widely; often >10â»Â² | <50% | Very Low |

Mitigation Strategies: Overcoming the Curse

Algorithmic Solutions

The most effective strategy identified for mitigating the winner's curse in VQE is a shift in the optimization objective from the "best-ever" cost to the population mean cost [12]. In population-based optimizers like CMA-ES, instead of selecting parameters associated with the single lowest noisy energy evaluation, the algorithm tracks and optimizes the average performance of a group of parameter sets. This approach directly counteracts the estimator bias, as the population mean is a more stable statistic less susceptible to downward noise fluctuations [12].

Another advanced strategy is Inference-Aware Policy Optimization, a method emerging from machine learning. This technique modifies the policy optimization to account for downstream statistical evaluation. It optimizes not only for the predicted performance but also for the probability that the policy will be statistically significantly better than a baseline, thus internalizing the winner's curse into the optimization objective itself [24].

Workflow for Reliable VQE Optimization

The diagram below illustrates a robust experimental workflow that incorporates these mitigation strategies.

Diagram 1: A reliable VQE workflow integrating mitigation strategies for the winner's curse. The key steps are the use of resilient optimizers and the tracking of the population mean during optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for VQE Research

| Research Reagent | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Optimizer Library (Mealpy, PyADE) | Provides a standardized interface to a wide range of metaheuristic algorithms for benchmarking. | Essential for fairly comparing dozens of algorithms like PSO, GA, DE, and CMA-ES [4]. |

| Quantum Simulation Stack (Qiskit, Cirq, Pennylane) | Simulates the execution of parameterized quantum circuits and calculates expectation values. | Allows for controlled introduction of finite-shot noise to test optimizer resilience [12]. |

| CMA-ES Optimizer | An adaptive evolution strategy that is currently the most resilient to noise and winner's curse. | Its population-based approach naturally allows for mean-tracking mitigation strategies [4] [12]. |

| Cost Landscape Visualizer | Creates 2D/3D visualizations of the VQE cost function around parameter points. | Used to empirically show how noise transforms smooth basins into rugged landscapes [4]. |

| Structured Benchmark Problem Set | A collection of standard Hamiltonians (e.g., Ising, Hubbard, Hâ‚‚, LiH). | Enables reproducible and comparable evaluation of optimizer performance across studies [4] [12] [25]. |

| Catharanthine (Standard) | Catharanthine (Standard), MF:C21H24N2O2, MW:336.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,5-Dihydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone | 2,5-Dihydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone, CAS:1760-52-7, MF:C6H4O4, MW:140.09 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The statistical challenge posed by the winner's curse and stochastic variational bound violation is a critical roadblock for the practical application of VQEs in noisy environments. Benchmarking data conclusively demonstrates that optimizer choice is not a matter of preference but of necessity, with adaptive metaheuristics like CMA-ES and iL-SHADE consistently achieving superior and more reliable performance by implicitly averaging noise and resisting false minima. For researchers in drug development and quantum chemistry, the path forward requires adopting these resilient optimizers and integrating mitigation strategies—primarily population mean tracking—directly into the experimental workflow. As the field progresses, future work must focus on strategies that co-design optimization algorithms with error mitigation techniques to combat combined sources of noise, moving VQEs closer to delivering on their promise for computational molecular design.

Algorithmic Strategies: From Gradient-Based Descent to Noise-Resilient Metaheuristics

The performance of Variational Quantum Eigensolvers (VQE) is critically dependent on the classical optimization routines that navigate complex, high-dimensional energy landscapes. These landscapes are characterized by pervasive challenges such as barren plateaus, where gradients vanish exponentially with qubit count, and finite-shot sampling noise that distorts the true cost function, creating false minima and misleading convergence signals [21] [11]. The "winner's curse" phenomenon—where statistical fluctuations create illusory minima that appear better than the true ground state—further complicates reliable optimization [12]. Within this context, understanding the strengths and limitations of different classical optimizer classes becomes essential for advancing quantum computational chemistry and materials science, particularly in applications like drug development where accurate molecular energy calculations are paramount.

Classical optimizers for VQEs can be categorized into three distinct paradigms based on their operational principles and use of derivative information. The fundamental differences between these approaches significantly impact their performance in noisy quantum environments.

Gradient-Based Optimizers

Gradient-based methods utilize gradient information of the cost function to inform parameter updates. In VQE contexts, gradients can be computed directly on quantum hardware using parameter-shift rules or approximated through finite differences.

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) & Momentum Variants: The foundational SGD update rule is ( \theta{t+1} = \thetat - \eta \nabla\theta L(\thetat) ), where ( \eta ) is the learning rate [26]. Momentum accelerates convergence in relevant directions by accumulating an exponentially decaying average of past gradients: ( vt = \gamma v{t-1} + \eta \nabla\theta L(\thetat) ), with ( \theta{t+1} = \thetat - v_t ) [26]. The Nesterov Accelerated Gradient (NAG) provides "lookahead" by computing the gradient at an approximate future position, often making it more responsive to changes in the loss landscape [26].

Adaptive Learning Rate Methods: Algorithms like Adam combine momentum with per-parameter learning rate adaptations, typically performing well in classical deep learning. However, in noisy VQE landscapes, their reliance on precise gradient estimates becomes a liability when gradients approach the noise floor [11].

Quasi-Newton Methods: Algorithms like BFGS and L-BFGS build an approximation to the Hessian matrix to inform more intelligent update directions. While powerful in noiseless conditions, they can diverge or stagnate when finite-shot sampling noise distorts gradient and curvature information [11].

Gradient-Free Optimizers (Non-Population-Based)

This category encompasses deterministic and heuristic methods that do not require gradient calculations, instead relying directly on function evaluations.

Direct Search Methods: Algorithms like Nelder-Mead (simplex method) and Powell's method navigate the parameter space by comparing function values at geometric patterns of points (e.g., simplex vertices) without constructing gradient approximations [21].

Model-Based Optimization: COBYLA (Constrained Optimization BY Linear Approximation) constructs linear approximations of the objective function to iteratively solve trust-region subproblems, making it suitable for derivative-free constrained optimization [27].

Quantum-Aware Optimizers: Specialized methods like Rotosolve and its generalization, ExcitationSolve, exploit the known mathematical structure of parameterized quantum circuits [28]. For excitation operators with generators satisfying ( Gj^3 = Gj ), the energy landscape for a single parameter follows a second-order Fourier series: ( f{θ}(θj) = a1\cos(θj) + a2\cos(2θj) + b1\sin(θj) + b2\sin(2θj) + c ) [28]. By measuring only five distinct parameter configurations, these methods can reconstruct the entire 1D landscape and classically compute the global minimum for that parameter, proceeding through parameters sequentially in a coordinate descent fashion [28].

Population-Based Metaheuristics

Population-based methods maintain and evolve multiple candidate solutions simultaneously, leveraging collective intelligence to explore complex landscapes.

Evolutionary Strategies: Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) represents a state-of-the-art approach that adapts a multivariate Gaussian distribution over the parameter space. It automatically adjusts its step size and the covariance matrix of the distribution to navigate ill-conditioned, noisy landscapes effectively [11] [10].

Differential Evolution (DE): DE generates new candidates by combining existing ones according to evolutionary operators. The improved L-SHADE (iL-SHADE) variant incorporates success-history-based parameter adaptation and linear population size reduction, enhancing its robustness in noisy environments [11] [10].

Other Metaheuristics: Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) simulates social behavior, with particles adjusting their trajectories based on personal and neighborhood best solutions [29]. Additional algorithms like Simulated Annealing, Harmony Search, and Symbiotic Organisms Search have demonstrated varying degrees of success in VQE contexts [4] [10].

Table 1: Classical Optimizer Taxonomy and Key Characteristics

| Optimizer Class | Representative Algorithms | Core Mechanism | Key Hyperparameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-Based | SGD, Momentum, NAG, Adam, BFGS | Gradient descent using first-order (and approximate second-order) derivatives | Learning rate, momentum factor |

| Gradient-Free (Non-Population) | COBYLA, Nelder-Mead, Rotosolve, ExcitationSolve | Direct search, model-based approximation, or analytical landscape reconstruction | Initial simplex size, trust region radius |

| Population-Based Metaheuristics | CMA-ES, iL-SHADE, PSO, GA | Population evolution through selection, recombination, and mutation | Population size, mutation/crossover rates |

Comparative Performance Analysis in Noisy VQE Environments

Recent large-scale benchmarking studies provide quantitative insights into how different optimizer classes perform under realistic VQE conditions characterized by finite-shot noise and barren plateaus.

Large-Scale Benchmarking Results

A comprehensive evaluation of over fifty metaheuristic algorithms for VQE revealed distinct performance patterns across different quantum chemistry Hamiltonians, including Hâ‚‚, Hâ‚„ chains, and LiH in both full and active spaces [11] [10]. The results demonstrated that adaptive metaheuristics, particularly CMA-ES and iL-SHADE, consistently achieved the best performance across models, showing remarkable resilience to noise-induced landscape distortions [11] [12]. Other algorithms including Simulated Annealing (Cauchy), Harmony Search, and Symbiotic Organisms Search also demonstrated robustness, though with less consistency than the top performers [4] [10].

In contrast, widely used population methods such as standard Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Genetic Algorithms (GA), and basic Differential Evolution (DE) variants degraded sharply as sampling noise increased [10]. Gradient-based methods including BFGS and SLSQP struggled significantly in noisy regimes, often diverging or stagnating when the cost curvature approached the level of sampling noise [11].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Across Optimizer Classes

| Optimizer | Class | Hâ‚‚ Convergence | Noise Robustness | Barren Plateau Resilience | Computational Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES | Population-Based | Excellent | High | Medium-High | High |

| iL-SHADE | Population-Based | Excellent | High | Medium-High | Medium-High |

| ExcitationSolve | Gradient-Free | Fast (where applicable) | Medium | Limited | Low |

| Simulated Annealing | Population-Based | Good | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| COBYLA | Gradient-Free | Medium | Low-Medium | Low | Low |

| PSO | Population-Based | Medium | Low | Low | Medium |

| BFGS | Gradient-Based | Medium (noiseless) | Low | Low | Low-Medium |

Barren Plateau Impacts Across Optimizer Classes

Contrary to initial speculation that gradient-free methods might avoid barren plateau limitations, theoretical analysis and numerical experiments confirm that barren plateaus affect all classes of optimizers, including gradient-free approaches [21]. The fundamental issue is that cost function differences between parameter points become exponentially small in a barren plateau, requiring exponential measurement precision for any optimizer to make progress, regardless of its optimization strategy [21].

This effect was numerically validated by training in barren plateau landscapes with gradient-free optimizers including Nelder-Mead, Powell, and COBYLA, demonstrating that the number of shots required for successful optimization grows exponentially with qubit count [21]. Population-based methods like CMA-ES exhibit somewhat better resilience not because they escape the fundamental scaling, but because they implicitly average noise across population members and can maintain diversity in search directions, providing a statistical advantage in practical finite-resource scenarios [11] [12].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Reproducible experimental design is essential for valid optimizer comparisons in VQE research. Standardized benchmarking protocols enable meaningful cross-study comparisons and reliable algorithm selection.

Benchmarking Workflow and Molecular Systems

A robust three-phase evaluation procedure has emerged as a standard for comprehensive optimizer assessment [10]:

- Initial Screening: Rapid testing on computationally tractable models like the 1D Ising model to identify promising candidate algorithms from a large pool of alternatives.

- Scaling Analysis: Systematic evaluation of promising algorithms on problems of increasing complexity, typically scaling up to 9+ qubits, to assess how performance degrades with system size.

- Convergence Validation: Final testing on challenging, chemically relevant systems such as the 192-parameter Hubbard model or molecular Hamiltonians (Hâ‚‚, Hâ‚„, LiH) to verify performance under realistic conditions [10].

Standardized molecular test systems include the hydrogen molecule (Hâ‚‚) for initial validation, hydrogen chains (Hâ‚„) for studying stronger correlations, and lithium hydride (LiH) in both full configuration and active space approximations to balance computational tractability with chemical relevance [11].

Noise Modeling and Statistical Validation

Accurate noise modeling is essential for predictive benchmarking. Finite-shot sampling noise is typically modeled as additive Gaussian noise: ( \bar{C}(θ) = C(θ) + \epsilon{\text{sampling}} ), where ( \epsilon{\text{sampling}} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2/N_{\text{shots}}) ) [11]. This noise model produces the characteristic "winner's curse" bias, where the best observed energy in a population is systematically biased downward from its true expectation value [11].

Effective mitigation strategies include population mean tracking rather than relying solely on the best individual, as the population mean provides a less biased estimator of true performance [12]. Additionally, re-evaluation of elite candidates with increased shot counts can reduce the risk of converging to false minima created by statistical fluctuations [11].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful VQE optimization requires both software frameworks and methodological components that constitute the essential "research reagents" for experimental quantum computational chemistry.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for VQE Optimization Studies

| Research Reagent | Type | Function/Purpose | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Hamiltonians | Problem Specification | Defines target quantum system for ground-state calculation | Hâ‚‚, Hâ‚„, LiH (STO-3G, 6-31G basis sets) |

| Parameterized Quantum Circuits | Ansatz | Encodes trial wavefunctions with tunable parameters | UCCSD, tVHA, Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA) |

| Classical Optimizer Libraries | Algorithm Implementation | Provides optimization algorithms for parameter tuning | CMA-ES, iL-SHADE (PyADE, Mealpy) |

| Quantum Simulation Frameworks | Computational Environment | Emulates quantum computer execution and measurements | Qiskit, Cirq, Pennylane with PySCF |

| Noise Modeling Tools | Experimental Condition | Mimics finite-shot sampling and hardware imperfections | Shot noise simulators (Gaussian) |

The comprehensive benchmarking of classical optimizers for noisy VQE landscapes reveals that adaptive metaheuristics, particularly CMA-ES and iL-SHADE, currently demonstrate superior performance under realistic finite-shot noise conditions. While gradient-free quantum-aware optimizers like ExcitationSolve offer compelling efficiency for specific ansatz classes, and gradient-based methods maintain strong performance in noiseless environments, the population-based approaches show the greatest resilience to the distorted, multimodal landscapes characteristic of contemporary quantum hardware.

Future research directions should focus on hybrid optimization strategies that leverage the strengths of multiple approaches, such as using quantum-aware methods for initial rapid convergence followed by population-based optimizers for refinement in noisy conditions. Additionally, algorithm selection frameworks guided by problem characteristics—including ansatz type, qubit count, and available shot budget—will help researchers navigate the complex optimizer landscape more effectively. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, the development of noise-aware optimization strategies that co-design classical optimizers with quantum error mitigation techniques will be essential for unlocking practical quantum advantage in computational chemistry and drug development applications.

Analysis of Gradient-Based Methods (BFGS, SLSQP) in Noisy Regimes

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithm for quantum chemistry and material science simulations on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. The classical optimization of variational parameters forms a critical component of VQE, where the choice of optimizer significantly impacts the reliability and accuracy of results. This guide provides a performance comparison of two prominent gradient-based methods—BFGS (Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno) and SLSQP (Sequential Least Squares Programming)—in the noisy environments characteristic of current quantum hardware. We synthesize findings from recent benchmarking studies to offer evidence-based recommendations for researchers and development professionals working in computational chemistry and drug discovery.

Experimental Methodologies for Benchmarking Optimizers

Molecular Systems and Ansätze

Recent studies have evaluated optimizer performance on progressively complex quantum chemical systems, from diatomic molecules to larger chains. The primary test systems include the hydrogen molecule (Hâ‚‚), hydrogen chain (Hâ‚„), and lithium hydride (LiH) in both full and active space configurations [11]. These systems provide standardized benchmarks due to their well-characterized electronic structures.

The experiments employ physically motivated ansätze, principally the truncated Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz (tVHA) and Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC)-inspired circuits, which respect physical symmetries like particle number conservation [11]. Comparative analyses also extend to hardware-efficient ansätze to assess generalizability across circuit types [11].

Noise Models and Sampling Conditions

To emulate real quantum hardware conditions, researchers introduce noise through finite-shot sampling and simulated decoherence channels [6]. The finite-shot noise is modeled as additive Gaussian noise:

[ \bar{C}(\bm{\theta}) = C(\bm{\theta}) + \epsilon{\text{sampling}}, \quad \epsilon{\text{sampling}} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2/N_{\text{shots}}) ]

where (C(\bm{\theta})) is the true expectation value and (N_{\text{shots}}) is the measurement budget [11]. This noise distorts the cost landscape, creating false minima and inducing a statistical bias known as the winner's curse [11].

Beyond sampling noise, studies incorporate quantum decoherence models—phase damping, depolarizing, and thermal relaxation channels—to provide a comprehensive assessment of optimizer resilience [6].

Performance Evaluation Metrics

The benchmarks employ multiple quantitative metrics for rigorous comparison:

- Convergence Accuracy: Final energy error relative to the full configuration interaction (FCI) or exact diagonalization value.

- Statistical Reliability: Success rate and consistency across multiple random initializations.

- Resource Efficiency: Number of function evaluations and iterations to convergence.

- Noise Resilience: Performance degradation rate with increasing noise intensity.

The following diagram illustrates a standard experimental workflow for benchmarking optimizers under noisy conditions.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Performance Data