Density Functional Theory in Modern Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide for Molecular Modeling

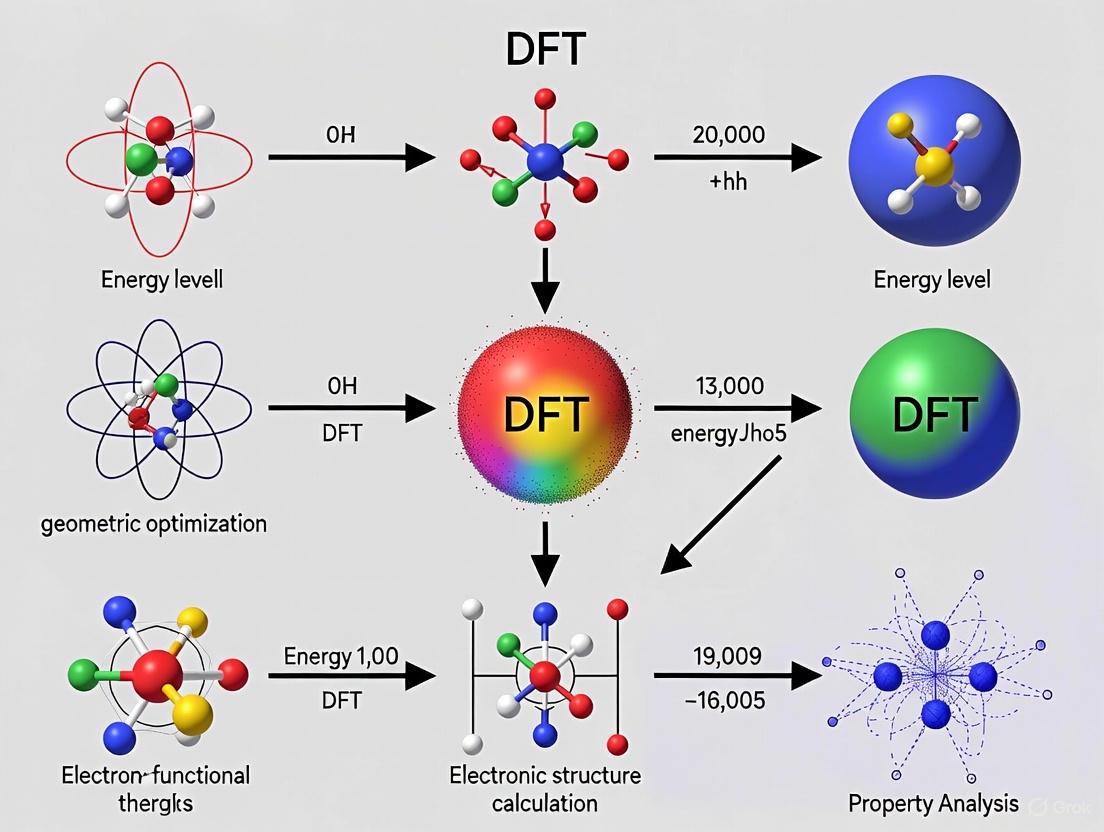

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Density Functional Theory (DFT) and its powerful applications in molecular modeling for drug discovery.

Density Functional Theory in Modern Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide for Molecular Modeling

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Density Functional Theory (DFT) and its powerful applications in molecular modeling for drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and pharmaceutical development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of DFT, from the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems to the Kohn-Sham equations. It details practical methodological protocols for calculating key molecular properties, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and validates DFT's performance against experimental data and other computational methods. By integrating conceptual DFT with molecular docking and QSAR modeling, this guide serves as a vital resource for enhancing the efficiency and predictive accuracy of rational drug design.

The Theoretical Bedrock: Understanding DFT's Core Principles

Density Functional Theory (DFT) represents a revolutionary approach in computational quantum mechanics that has transformed the study of many-body systems in physics, chemistry, and materials science. Unlike traditional wavefunction-based methods that struggle with the computational complexity of tracking 3N variables for N electrons, DFT dramatically simplifies the problem by utilizing the electron density—a function of only three spatial coordinates—as its fundamental variable [1]. This paradigm shift originated from the seminal work of Pierre Hohenberg and Walter Kohn, whose 1964 paper established the theoretical foundation for DFT [2] [3]. Their pioneering work, which earned Walter Kohn the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1998, demonstrated that all ground-state properties of a many-electron system are uniquely determined by its electron density distribution [2] [1]. This core insight has enabled researchers to investigate complex molecular systems with computational efficiency previously thought impossible, making DFT one of the most popular and versatile methods in condensed-matter physics and computational chemistry today [1].

The significance of DFT extends far beyond theoretical interest, particularly in molecular modeling research where it provides practical solutions to previously intractable problems. In modern pharmaceutical formulation development, for instance, precision design at the molecular level is increasingly replacing traditional empirical trial-and-error approaches [4] [5]. For drug development professionals, DFT offers transformative theoretical insights by elucidating the electronic nature of molecular interactions, enabling systematic understanding of complex behaviors in drug-excipient composite systems [5]. With more than 60% of formulation failures for certain drug classes attributed to unforeseen molecular interactions between active pharmaceutical ingredients and excipients, DFT's ability to resolve electronic structures with quantum mechanical precision addresses critical challenges that traditional characterization techniques cannot adequately overcome [4] [5].

Theoretical Foundation: The Hohenberg-Kohn Theorems

The First Hohenberg-Kohn Theorem

The first Hohenberg-Kohn theorem establishes the fundamental principle that the ground-state electron density uniquely determines the external potential (and thus all properties of the system, including the full wavefunction) [6] [3] [1]. Mathematically, this theorem states that there exists a one-to-one mapping between the ground-state electron density nâ‚€(r) and the external potential V_ext(r):

[ n0(\mathbf{r}) \longleftrightarrow V{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) ]

This represents a massive simplification of the many-body problem because it reduces the variable space from 3N coordinates (for N electrons) to just three spatial coordinates [1]. The theorem proves that the electron density uniquely determines the Hamiltonian operator, and therefore all electronic properties of the system can be considered functionals of the electron density [6] [1]. For researchers working with complex molecular systems, this means that instead of dealing with the intractable many-electron wavefunction, they can focus on the much simpler electron density while still accessing complete information about the ground state [3].

The Second Hohenberg-Kohn Theorem

The second Hohenberg-Kohn theorem provides the variational principle for DFT [3]. It states that the electron density that minimizes the total energy functional E[n] corresponds to the true ground-state density [2] [1]. This theorem defines an energy functional for the system and proves that the ground-state electron density minimizes this energy functional [1]. The total energy functional can be written as:

[ E[n] = F{\text{HK}}[n] + \int V{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) n(\mathbf{r}) d^3\mathbf{r} ]

where F_HK[n] is a universal functional (the same for all systems) of the electron density that contains the kinetic energy and electron-electron interaction terms [1]. For practical applications, this variational principle enables researchers to optimize molecular structures and predict properties by minimizing the energy with respect to the electron density [3].

The Kohn-Sham Equations: From Theory to Practical Computation

The Kohn-Sham Scheme

While the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems established the theoretical foundation, the practical implementation of DFT became feasible through the Kohn-Sham scheme introduced in 1965 [2] [1]. The key insight of Kohn and Sham was to replace the original interacting system with an auxiliary system of non-interacting electrons that has the same ground-state density [1]. This approach decomposes the universal functional F[n] into computable components:

[ F[n] = Ts[n] + EH[n] + E_{xc}[n] ]

where Ts[n] is the kinetic energy of the non-interacting system, EH[n] is the classical Hartree electrostatic energy, and E_xc[n] is the exchange-correlation functional that captures all the quantum mechanical many-body effects [4] [1].

The Kohn-Sham equations form a self-consistent system:

[ \left[-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\nabla^2 + V{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r})\right] \psii(\mathbf{r}) = \varepsiloni \psii(\mathbf{r}) ]

where the effective potential V_eff(r) is given by:

[ V{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r}) = V{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) + VH(\mathbf{r}) + V{xc}(\mathbf{r}) ]

These equations must be solved iteratively until self-consistency is achieved [2], as illustrated in the following workflow:

Exchange-Correlation Functionals: The Key Challenge

The accuracy of DFT calculations critically depends on the approximation used for the exchange-correlation functional E_xc[n] [4] [1]. Since the exact form of this functional remains unknown, various approximations have been developed, each with different levels of accuracy and computational cost [4] [5]. The following table summarizes the main classes of functionals used in contemporary research:

Table 1: Classification of Exchange-Correlation Functionals in DFT

| Functional Class | Key Features | Typical Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Density Approximation (LDA) | Uses local electron density; exact for uniform electron gas [4] [1] | Metallic systems, crystal structures [4] [5] | Poor description of weak interactions (van der Waals) [4] |

| Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) | Includes density gradient corrections [4] [1] | Molecular properties, hydrogen bonding, surfaces [4] [5] [7] | Underestimates reaction barriers [4] |

| Meta-GGA | Incorporates kinetic energy density [4] | Atomization energies, chemical bonds [4] | Limited accuracy for excited states [4] |

| Hybrid Functionals | Mixes Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange-correlation [4] [1] | Reaction mechanisms, molecular spectroscopy [4] [5] | Higher computational cost [4] |

| Double Hybrid Functionals | Includes second-order perturbation theory corrections [4] [8] | Excited-state energies, reaction barriers [4] | Significantly higher computational cost [8] |

For drug development professionals, the selection of appropriate functionals depends on the specific application. Hybrid functionals like B3LYP and PBE0 are widely employed for studying reaction mechanisms and molecular spectroscopy, while GGA functionals offer a good balance between accuracy and computational efficiency for many molecular property calculations [4] [5].

Computational Protocols for Molecular Systems

Standard DFT Calculation Workflow

The following protocol outlines a standard DFT calculation for molecular systems, particularly relevant for pharmaceutical applications:

Protocol 1: Ground-State Electronic Structure Calculation

System Preparation

- Obtain initial molecular geometry from experimental data (X-ray crystallography) or molecular mechanics optimization

- For drug molecules, ensure proper protonation states corresponding to physiological pH

Functional and Basis Set Selection

- Select appropriate exchange-correlation functional based on system properties and accuracy requirements (see Table 1)

- Choose basis set compatible with selected functional (e.g., 6-31G*, def2-TZVP, cc-pVDZ)

- For solid-state systems, employ plane-wave basis sets with pseudopotentials [7]

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Procedure

- Initialize calculation with superposition of atomic densities

- Solve Kohn-Sham equations iteratively until convergence criteria met

- Typical convergence thresholds: energy change < 10â»âµ Ha, density change < 10â»â¶ electrons/bohr³

Property Analysis

Advanced Protocol: Drug-Excipient Interaction Study

Protocol 2: Pharmaceutical Formulation Optimization

Molecular System Setup

- Construct API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient) molecule using quantum chemistry software

- Model excipient molecules (e.g., polymers, surfactants, co-crystal formers)

- Generate initial complex geometries through molecular docking or manual placement

Interaction Energy Calculation

- Perform geometry optimization of isolated components and complex

- Calculate binding energy using counterpoise correction to address basis set superposition error: [ \Delta E{\text{bind}} = E{\text{complex}} - (E{\text{API}} + E{\text{excipient}}) ]

- Include dispersion corrections (e.g., D3, D4) for van der Waals interactions [4]

Solvation Effects

Stability and Reactivity Analysis

- Perform Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis to characterize intermolecular interactions [7]

- Calculate HOMO-LUMO gaps for stability assessment

- Map electrostatic potential surfaces for interaction hot-spot identification

The following decision framework guides functional selection for pharmaceutical applications:

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for DFT

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for DFT in Molecular Modeling Research

| Tool Category | Specific Software | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem | Molecular DFT calculations with localized basis sets | Drug molecule optimization, reaction mechanism studies [4] [5] |

| Solid-State Codes | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, ABINIT | Periodic DFT calculations with plane-wave basis sets | Nanomaterial characterization, crystal structure prediction [2] [7] |

| Multiscale Frameworks | ONIOM | Combined QM/MM calculations | Protein-ligand interactions, large system modeling [4] [5] |

| Visualization & Analysis | VMD, ChemCraft, Jmol | Molecular structure and property visualization | Analysis of electron density, molecular orbitals, electrostatic potentials [4] |

| Machine Learning-Augmented DFT | DeePHF, NeuralXC | High-accuracy calculations with DFT efficiency | Reaction energy prediction with CCSD(T)-level accuracy [9] [8] |

Applications in Molecular Modeling and Drug Development

Pharmaceutical Formulation Design

DFT has become an indispensable tool in modern pharmaceutical formulation development, enabling precision design at the molecular level that replaces traditional empirical trial-and-error approaches [4] [5]. By solving the Kohn-Sham equations with precision up to 0.1 kcal/mol, DFT enables accurate electronic structure reconstruction, providing theoretical guidance for optimizing drug-excipient composite systems [5]. Specific applications include:

API-Excipient Co-crystallization: DFT clarifies the electronic driving forces governing active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)-excipient co-crystallization, leveraging Fukui functions to predict reactive sites and guide stability-oriented co-crystal design [4] [5]. This approach has substantially reduced experimental validation cycles in formulation development.

Nanodelivery Systems: DFT optimizes carrier surface charge distribution through van der Waals interactions and π-π stacking energy calculations, thereby enhancing targeting efficiency [5]. For nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems, DFT simulations predict how surface modifications affect drug loading and release profiles [7].

Solvation and Release Kinetics: DFT combined with solvation models (e.g., COSMO) quantitatively evaluates polar environmental effects on drug release kinetics, delivering critical thermodynamic parameters (e.g., ΔG) for controlled-release formulation development [4] [5]. This enables researchers to predict how formulation factors influence dissolution rates and bioavailability.

Reaction Mechanism Studies in Drug Metabolism

DFT provides crucial insights into drug metabolism and reactivity by accurately predicting reaction pathways and energy barriers [4] [8]:

Reaction Site Identification: Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) maps and Average Local Ionization Energy (ALIE) are critical parameters for predicting drug-target binding sites [4]. MEP maps depict the distribution of molecular surface charges by calculating electrostatic potentials, thereby identifying regions that are electron-rich (nucleophilic) and electron-deficient (electrophilic).

Barrier Height Prediction: Accurate prediction of activation energies (Eâ‚) for metabolic reactions using advanced functionals or machine learning-augmented approaches like DeePHF, which achieves CCSD(T)-level precision while retaining DFT efficiency [8]. This allows researchers to identify potential metabolic hotspots and design drugs with improved metabolic stability.

Solid-State Properties: DFT studies accurately predict crystalline stability, polymorphism, and hydration states of pharmaceutical compounds [4] [5]. These predictions guide the selection of optimal solid forms for development, avoiding stability issues during manufacturing and storage.

Table 3: Quantitative Performance of DFT Methods for Reaction Energy Prediction

| Computational Method | Mean Absolute Error (kcal/mol) Reaction Energies | Mean Absolute Error (kcal/mol) Barrier Heights | Computational Scaling | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP-D3 | 5.26 | 4.22 | O(N³) | Initial screening, geometry optimization |

| M06-2X | 2.76 | 2.27 | O(N³) | Main-group thermochemistry, noncovalent interactions |

| ωB97M-V | 1.26 | 1.50 | O(Nâ´) | High-accuracy single-point energies |

| Double Hybrid Functionals | ~1.0 | ~1.0 | O(Nâµ) | Benchmark-quality results |

| DeePHF (ML-DFT) | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | O(N³) | CCSD(T)-level accuracy for reactions [8] |

Nanomaterial Design for Drug Delivery

DFT simulations enable rational design of nanomaterials for biomedical applications by predicting their structural, electronic, and optical properties [7]:

Surface Functionalization: DFT calculations guide the selection of surface modifications to optimize drug loading, targeting, and release from nanocarriers [7]. Studies examine how different functional groups affect interaction energies with drug molecules.

Band Gap Engineering: For semiconductor nanoparticles used in photodynamic therapy or bioimaging, DFT predicts how size, shape, and doping influence band gaps and optical properties [7]. This enables tailored design of nanoparticles with specific absorption and emission characteristics.

Catalytic Activity Prediction: In the context of prodrug activation or reactive oxygen species generation, DFT calculations identify catalytic hotspots on nanoparticle surfaces and predict reaction mechanisms [7]. This facilitates the design of more efficient catalytic nanomedicines.

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

Machine Learning-Augmented DFT

The integration of machine learning with DFT represents the cutting edge of computational molecular modeling [9] [8]. Recent advances include:

Improved Exchange-Correlation Functionals: Machine learning models trained on high-quality quantum chemistry data can discover more universal XC functionals, creating a bridge between DFT accuracy and computational efficiency [9]. For instance, models incorporating both energies and potentials as training data demonstrate enhanced accuracy while maintaining reasonable computational costs [9].

Delta-Learning Approaches: Frameworks like DeePHF establish direct mappings between the eigenvalues of local density matrices and high-level correlation energies, achieving CCSD(T)-level precision while retaining O(N³) scaling [8]. These methods have demonstrated superior performance across multiple benchmark datasets, exhibiting exceptional transferability beyond their training sets [8].

Neural Network Potentials: Machine learning potentials trained on DFT data enable molecular dynamics simulations of large systems at quantum mechanical accuracy, bridging the time and length scale gap between DFT simulations and biological processes [8].

Multiscale Modeling Frameworks

Combining DFT with molecular mechanics and coarse-grained methods addresses the challenge of simulating complex biological environments [4] [5]:

QM/MM Approaches: The ONIOM multiscale framework employs DFT for high-precision calculations of drug molecule core regions while using molecular mechanics force fields to model protein environments [4]. This approach, combined with machine learning potentials, substantially enhances computational efficiency for studying protein-ligand interactions.

Embedding Techniques: DFT embedding methods enable high-accuracy calculations on active sites while treating the surrounding environment with lower-level methods, providing a balanced approach for studying enzymatic reactions and solvent effects [4] [5].

Challenges and Limitations

Despite remarkable progress, DFT still faces several challenges in molecular modeling applications:

Van der Waals Interactions: Conventional functionals often fail to accurately describe dispersion forces, though empirical corrections and nonlocal functionals have significantly improved this situation [1].

Charge Transfer Excitations: TDDFT calculations for excited states involving charge transfer can be inaccurate with standard functionals, requiring range-separated hybrids for reliable results [4] [1].

Strong Correlation Systems: Systems with strong electron correlation (e.g., transition metal complexes with near-degenerate states) remain challenging for standard DFT approximations [1].

Solvation Models: While implicit solvation models have improved considerably, explicit treatment of solvent molecules and dynamic effects still presents computational challenges [4] [5].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these limitations highlight the importance of method validation and the selective use of advanced DFT approaches tailored to specific scientific questions. As functional development and machine learning integration continue to advance, DFT is poised to become an even more powerful tool for molecular design and optimization in pharmaceutical research.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) represents a monumental shift in computational quantum chemistry, enabling the study of many-electron systems by using the electron density—a function of only three spatial variables—as the fundamental variable instead of the complex many-body wavefunction. The theoretical foundation of DFT is built upon the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, which establish that all ground-state properties of a many-electron system are uniquely determined by its electron density [10]. This revolutionary principle reduces the computational complexity from 3N variables for N electrons to just three spatial variables, making accurate calculations on complex systems feasible [1]. However, the practical implementation of DFT remained challenging until the seminal 1965 work of Walter Kohn and Lu Jeu Sham, who introduced the Kohn-Sham equations [11] [12]. This ingenious approach created a workable framework for electronic structure calculations by introducing a fictitious system of non-interacting particles that generates the same density as the real, interacting system [13] [11]. For this breakthrough, Walter Kohn was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1998, cementing DFT's role as a cornerstone of modern computational materials science and quantum chemistry [11].

The Kohn-Sham formalism effectively sidesteps the primary difficulty in traditional orbital-free DFT: finding an accurate expression for the kinetic energy functional. By introducing a non-interacting reference system with the same density as the real system, Kohn and Sham enabled the calculation of the kinetic energy exactly for the non-interacting system, leaving only a relatively small portion of the total energy—the exchange-correlation energy—to be approximated [14]. This clever theoretical construct has made Kohn-Sham DFT an indispensable tool across numerous scientific fields, with at least 30,000 scientific papers utilizing the method annually to solve electronic structure problems [15]. In pharmaceutical research specifically, DFT calculations solving the Kohn-Sham equations with precision up to 0.1 kcal/mol enable accurate electronic structure reconstruction, providing critical theoretical guidance for optimizing drug-excipient composite systems [4] [5].

Theoretical Foundation

The Hohenberg-Kohn Theorems

The theoretical edifice of Density Functional Theory rests firmly on two fundamental propositions known as the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems. The first Hohenberg-Kohn theorem establishes a one-to-one correspondence between the external potential acting on a many-electron system and its ground-state electron density [1] [10]. This profound result demonstrates that the electron density uniquely determines all ground-state properties, including the total energy, wavefunction, and any other observable of the system. The theorem provides the formal justification for using electron density—which depends on only three spatial coordinates—as the fundamental variable, thereby reducing the complexity of the many-body problem from 3N dimensions to just three [10]. The second Hohenberg-Kohn theorem defines an energy functional for the system and proves that the ground-state electron density minimizes this energy functional [1]. This variational principle provides the theoretical foundation for finding the ground-state density through energy minimization, analogous to the approach used in wavefunction-based quantum chemistry methods.

The Hohenberg-Kohn theorems collectively establish that the ground-state energy E₀ of a many-electron system can be expressed as a functional of the electron density n(r): [ E0 = E[n0] = \langle \Psi[n0] | \hat{T} + \hat{V} + \hat{U} | \Psi[n0] \rangle ] where Ψ[n₀] is the ground-state wavefunction functional, T̂ represents the kinetic energy operator, V̂ is the external potential operator, and Û denotes the electron-electron interaction operator [1]. The contribution of the external potential can be further simplified to: [ V[n] = \int V(\mathbf{r}) n(\mathbf{r}) \mathrm{d}^3\mathbf{r} ] This formulation dramatically simplifies the electronic structure problem but leaves the practical challenge of constructing accurate approximations for the universal functionals T[n] and U[n] [1].

The Kohn-Sham Formalism

The Kohn-Sham approach addresses the central challenge in practical DFT implementations through an ingenious indirect method. Rather than attempting to compute the kinetic energy directly from the density (the "orbital-free" approach), Kohn and Sham introduced a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons that exactly reproduces the electron density of the real, interacting system [11] [14]. This theoretical construct allows the kinetic energy to be computed exactly for the non-interacting system, while all the complexities of electron-electron interactions are absorbed into the exchange-correlation functional.

Within the Kohn-Sham formalism, the ground-state electronic energy E can be decomposed as: [ E = ET + EV + EJ + E{XC} ] where ET is the kinetic energy of the non-interacting system, EV is the electron-nuclear interaction energy, EJ is the classical Coulomb self-interaction of the electron density, and EXC is the exchange-correlation energy [14]. The total electron density Ï(r) is constructed from the Kohn-Sham orbitals: [ \rho(\mathbf{r}) = \rho^\alpha(\mathbf{r}) + \rho^\beta(\mathbf{r}) = \sum{i=1}^{n^\alpha} |\psii^\alpha|^2 + \sum{i=1}^{n^\beta} |\psii^\beta|^2 ] where ψi^α and ψi^β are the Kohn-Sham orbitals for alpha and beta spins, respectively [14]. In a finite basis set representation, the density is expressed as: [ \rho(\mathbf{r}) = \sum{\mu\nu} P{\mu\nu} \phi\mu(\mathbf{r}) \phi\nu(\mathbf{r}) ] where Pμν are the elements of the one-electron density matrix and φμ are the basis functions [14].

Table 1: Components of the Kohn-Sham Energy Functional

| Energy Component | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Energy (E_T) | (\sum{i=1}^{n^\alpha} \langle \psii^\alpha \vert -\frac{1}{2}\nabla^2 \vert \psii^\alpha \rangle + \sum{i=1}^{n^\beta} \langle \psii^\beta \vert -\frac{1}{2}\nabla^2 \vert \psii^\beta \rangle) | Kinetic energy of non-interacting electrons | ||

| Electron-Nuclear Interaction (E_V) | (-\sum{A=1}^{M} ZA \int \frac{\rho(\mathbf{r})}{ | \mathbf{r}-\mathbf{R}_A | } d\mathbf{r}) | Coulomb attraction between electrons and nuclei |

| Hartree Energy (E_J) | (\frac{1}{2} \langle \rho(\mathbf{r}_1) \vert \frac{1}{ | \mathbf{r}1-\mathbf{r}2 | } \vert \rho(\mathbf{r}_2) \rangle) | Classical electron-electron repulsion |

| Exchange-Correlation Energy (E_XC) | (\int f[\rho(\mathbf{r}), \nabla\rho(\mathbf{r}), \ldots] \rho(\mathbf{r}) d\mathbf{r}) | Quantum mechanical effects beyond Hartree term |

The brilliance of the Kohn-Sham approach lies in its separation of the computationally challenging many-body problem into manageable components. The non-interacting kinetic energy ET can be computed accurately using the Kohn-Sham orbitals, while the exchange-correlation energy EXC encapsulates all the quantum mechanical complexities, including electron exchange, correlation effects, and the correction for the self-interaction error in the Hartree term [14]. Although the exact form of EXC remains unknown, this separation ensures that even simple approximations to EXC can yield remarkably accurate results for many systems of practical interest.

The Kohn-Sham Equations

Mathematical Formulation

The Kohn-Sham equations form a set of one-electron Schrödinger-like equations for the non-interacting reference system. Through the variational principle applied to the Kohn-Sham energy functional, we arrive at the canonical form of the Kohn-Sham equations [13] [11]: [ \left[-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\nabla^2 + V{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r})\right] \phii(\mathbf{r}) = \varepsiloni \phii(\mathbf{r}) ] where φi(r) are the Kohn-Sham orbitals, εi are the orbital energies, and Veff(r) is the effective potential experienced by the electrons [11]. The effective potential is composed of three distinct components: [ V{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r}) = V{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) + VH(\mathbf{r}) + V{XC}(\mathbf{r}) ] Here, Vext(r) represents the external potential (typically the electron-nucleus attraction), VH(r) is the Hartree or Coulomb potential describing the classical electron-electron repulsion, and VXC(r) is the exchange-correlation potential [13] [10].

The Hartree potential is obtained from the electron density through the Poisson equation: [ \nabla^2 VH(\mathbf{r}) = -4\pi e \rho(\mathbf{r}) ] while the exchange-correlation potential is defined as the functional derivative of the exchange-correlation energy with respect to the density: [ V{XC}(\mathbf{r}) \equiv \frac{\delta E{XC}[\rho]}{\delta \rho(\mathbf{r})} ] The electron density is constructed from the occupied Kohn-Sham orbitals: [ \rho(\mathbf{r}) = -e \sum{i, \text{occup}} |\phi_i(\mathbf{r})|^2 ] where the summation is over all occupied states [13]. For systems employing pseudopotentials, these states correspond to the valence states, with core electrons being treated within the pseudopotential approximation.

The Self-Consistent Field Procedure

The solution of the Kohn-Sham equations requires an iterative self-consistent field (SCF) procedure because the effective potential itself depends on the electron density, which in turn depends on the Kohn-Sham orbitals. This recursive relationship necessitates an iterative approach until self-consistency is achieved [13] [10].

The SCF procedure follows these key steps:

Initial Guess: An initial approximation for the electron density Ï(r) is generated, typically using superposition of atomic densities or from a previous calculation [13].

Potential Construction: The exchange-correlation potential VXC(r) is estimated from the current density, and the Hartree potential VH(r) is computed by solving the Poisson equation [13].

Kohn-Sham Solution: The Kohn-Sham equations are solved with the constructed effective potential to obtain a new set of orbitals φi(r) and eigenvalues εi [13].

Density Update: A new electron density is computed from the obtained orbitals according to Ï(r) = -eΣ|φ_i(r)|² [13].

Convergence Check: The process is repeated until the input and output charge densities or potentials are identical within a prescribed tolerance, typically requiring 10-100 iterations for most systems [13] [10].

The following diagram illustrates this iterative SCF procedure:

Diagram 1: The Kohn-Sham self-consistent field procedure

Once self-consistency is achieved, the total energy ET can be computed using the expression: [ ET = \sum{i}^{M} Ei - \frac{1}{2} \int \rho(\mathbf{r}) VH(\mathbf{r}) d^3r + \int \rho(\mathbf{r}) (E{XC}[\rho(\mathbf{r})] - V_{XC}[\rho(\mathbf{r})]) d^3r ] where the summation is over the M occupied states [13]. This total electronic energy must be added to the ion-ion interaction energy to obtain the structural energy of the system.

Computational Implementation

Basis Sets and Numerical Methods

The practical implementation of Kohn-Sham DFT requires the expansion of the Kohn-Sham orbitals in a set of basis functions. Several methodological approaches have been developed for this purpose, including the full-potential linear muffin-tin orbital (FP-LMTO) method, linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO), and plane-wave basis sets [13]. In the FP-LMTO method, for example, the Kohn-Sham wavefunction ψi,k(r) is expanded as: [ \psi{i,k}(\mathbf{r}) = \sum{l}^{l{\text{max}}} c{li}^k \chil^k(\mathbf{r}) ] where χl^k(r) are the known basis functions (linear muffin-tin orbitals), c{li}^k are the expansion coefficients to be determined, and the sum is truncated after including sufficiently many basis functions [13].

The expansion coefficients are determined by solving the secular equation: [ \sum{l=0}^{l{\text{max}}} [H{ll'} - E{ik} O{ll'}] c{li}^k = 0 ] where Hll' are the Hamiltonian matrix elements and Oll' are the overlap matrix elements [13]. The eigenvalues Eik are then obtained by solving: [ \text{det} | H{ll'} - E{lk} O{ll'} | = 0 ] which constitutes a standard numerical linear algebra problem [13].

For periodic systems, the Bloch theorem is employed to account for the translational symmetry: [ \psi{i,k}(\mathbf{r} + \mathbf{R}) = e^{i\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{R}} \psi{i,k}(\mathbf{r}) ] where k is a vector in the first Brillouin zone and R is a Bravais lattice vector [13]. This approach requires integration over the Brillouin zone, with the electron density computed as: [ \rho^{\text{op}}(\mathbf{r}) = \sum{i} \sum{\mathbf{k}} |\psi{i,k}(\mathbf{r})|^2 ] and the eigenvalue sum given by: [ E{\text{sum}} = \sum{i} \sum{\mathbf{k}} E_{i,k} ] [13].

Exchange-Correlation Functionals

The accuracy of Kohn-Sham DFT calculations critically depends on the approximation used for the exchange-correlation functional E_XC[n]. Several classes of functionals have been developed, with varying levels of accuracy and computational cost:

Table 2: Hierarchy of Exchange-Correlation Functionals

| Functional Class | Description | Strengths | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Density Approximation (LDA) | Uses local electron density as only input; based on uniform electron gas | Computationally efficient; good for metallic systems | Poor description of weak interactions (van der Waals); tends to overbind | Simple metallic systems; crystal structures [4] [5] |

| Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) | Incorporates density gradient in addition to local density | Improved accuracy for molecular properties; describes hydrogen bonding | Still limited for dispersion interactions | Molecular property calculations; surface/interface studies [13] [4] |

| Meta-GGA | Includes kinetic energy density in addition to density and gradient | Better description of atomization energies and chemical bonds | Higher computational cost | Complex molecular systems; chemical bond properties [4] [5] |

| Hybrid Functionals | Mixes Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange-correlation | Improved accuracy for reaction barriers and molecular spectroscopy | Significantly higher computational cost | Reaction mechanisms; molecular spectroscopy [4] [5] |

| Double Hybrid Functionals | Incorporates second-order perturbation theory corrections | High accuracy for excited states and reaction barriers | Very computationally expensive | Excited-state energies; high-accuracy barrier calculations [4] [5] |

The continued development of improved exchange-correlation functionals remains an active area of research in computational chemistry and materials science. Recent advances include the incorporation of machine learning techniques to develop more accurate functionals and the creation of range-separated functionals that better describe long-range interactions [4] [15].

Practical Protocols for Kohn-Sham Calculations

Standard Calculation Workflow

A typical Kohn-Sham DFT calculation follows a systematic protocol to ensure reliable and converged results. The workflow can be divided into three main phases: pre-processing, self-consistent field calculation, and post-processing. The pre-processing phase involves system preparation, including geometry construction, atomic coordinate specification, and selection of appropriate computational parameters. The core SCF calculation then iteratively solves the Kohn-Sham equations until convergence criteria are met. Finally, the post-processing phase involves analysis of the electronic structure, computation of desired properties, and verification of results.

Table 3: Kohn-Sham DFT Calculation Protocol

| Step | Procedure | Key Parameters | Convergence Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Preparation | Define atomic coordinates and cell parameters; select pseudopotentials | Atomic positions; lattice vectors; pseudopotential type | N/A |

| Basis Set Selection | Choose appropriate basis set for system | Basis set type and size; cutoff energy (for plane waves) | Energy difference < 1 meV/atom with larger basis |

| Initialization | Generate initial electron density and wavefunctions | Initial guess method (atomic, superposition, etc.) | N/A |

| SCF Iteration | Solve Kohn-Sham equations iteratively | Mixing parameters; SCF convergence threshold | Density change < 10â»â¶ e/ų or energy change < 10â»â¶ eV/atom |

| Property Calculation | Compute energies, forces, stresses, band structures | k-point mesh for Brillouin zone integration | Property-specific tolerances |

| Analysis | Analyze results: density of states, population analysis, etc. | Projection methods; visualization parameters | N/A |

For molecular dynamics simulations using DFT, an additional outer loop is implemented where the SCF calculation is performed at each time step to compute forces, followed by nuclear position updates according to classical equations of motion. This approach, known as Born-Oppenheimer molecular dynamics, allows for the study of finite-temperature properties and dynamical processes while maintaining quantum mechanical accuracy for the electronic structure.

Successful implementation of Kohn-Sham calculations requires careful selection of computational tools and methods. The following table outlines key components of the computational scientist's toolkit for DFT calculations:

Table 4: Essential Computational Resources for Kohn-Sham Calculations

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Options | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Software Packages | Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP, GPAW, ABINIT, CASTEP | Implement Kohn-Sham formalism with various numerical approaches |

| Basis Set Types | Plane waves, Gaussian-type orbitals, numerical atomic orbitals, augmented plane waves | Expand Kohn-Sham orbitals in computationally tractable basis |

| Pseudopotentials | Norm-conserving, ultrasoft, PAW (Projector Augmented Wave) | Replace core electrons with effective potential to reduce computational cost |

| Exchange-Correlation Functionals | LDA (PZ, PW), GGA (PBE, BLYP), Hybrid (B3LYP, PBE0), Meta-GGA (SCAN) | Approximate quantum mechanical exchange and correlation effects |

| Geometry Optimization Algorithms | BFGS, conjugate gradient, damped molecular dynamics | Locate minimum energy structures |

| Solvation Models | COSMO, PCM, explicit solvation | Simulate environmental effects in solution-phase systems |

When planning Kohn-Sham calculations, researchers must consider the trade-offs between computational cost and accuracy. Plane-wave basis sets with pseudopotentials typically offer good convergence behavior and systematic improvability, while localized basis sets can be more computationally efficient for molecular systems. The choice of exchange-correlation functional should be guided by the system under investigation and the properties of interest, with hybrid functionals generally providing higher accuracy but at significantly increased computational cost.

Applications in Molecular Modeling Research

Pharmaceutical Formulation Design

Kohn-Sham DFT has emerged as a powerful tool in pharmaceutical formulation design, enabling precise understanding of molecular interactions at the electronic level. By solving the Kohn-Sham equations with quantum mechanical precision, DFT provides insights into the electronic driving forces governing drug-excipient compatibility, stability, and release kinetics [4] [5]. Specifically, in solid dosage forms, DFT clarifies the electronic factors controlling active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)-excipient co-crystallization, allowing researchers to predict reactive sites and guide stability-oriented co-crystal design [4]. For nanodelivery systems, DFT enables precise calculation of van der Waals interactions and π-π stacking energies to engineer carriers with tailored surface charge distributions, thereby enhancing targeting efficiency [4] [5].

The application of Kohn-Sham equations in pharmaceutical sciences extends to quantitative evaluation of environmental effects on drug release kinetics. When combined with solvation models such as COSMO (Conductor-like Screening Model), DFT provides critical thermodynamic parameters (e.g., ΔG) for controlled-release formulation development [5]. Notably, DFT-driven co-crystal thermodynamic analysis and pH-responsive release mechanism modeling have demonstrated substantial reductions in experimental validation cycles, accelerating the formulation development process [4]. More than 60% of formulation failures in the development of Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) II/IV drugs are attributed to unforeseen molecular interactions between APIs and excipients, a challenge that DFT directly addresses through its ability to resolve electronic structures and predict interaction energies [4] [5].

Material Science and Catalysis

Beyond pharmaceutical applications, Kohn-Sham DFT serves as an indispensable tool in materials science and catalysis research. The method enables accurate prediction of material properties, including band structures, elastic constants, magnetic properties, and surface reactivities. In heterogeneous catalysis, Kohn-Sham calculations provide insights into reaction mechanisms on catalyst surfaces, allowing for the computation of activation barriers and reaction energies that guide catalyst design [13]. The local density approximation (LDA) and its generalized gradient correction (GGA) have proven particularly useful for calculating accurate cohesive energies in materials [13].

For surface science applications, Kohn-Sham DFT facilitates the study of adsorption energies, surface reconstruction, and catalytic activity trends across different materials. Recent advances including time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) have further extended the applicability of the Kohn-Sham approach to excited-state properties, enabling investigations of photocatalytic processes, optical properties, and excited-state reactivity [4] [5]. The integration of DFT with multiscale modeling approaches, such as the ONIOM method, allows for high-precision calculations of reactive core regions while using molecular mechanics force fields to model extended environments, substantially enhancing computational efficiency for complex systems [4].

Advanced Methodologies and Future Directions

Machine Learning Enhancements

The integration of machine learning (ML) with Kohn-Sham DFT represents one of the most promising frontiers in computational materials science and quantum chemistry. Traditional Kohn-Sham calculations require iterative solution of the Kohn-Sham equations until self-consistency is achieved, a computationally demanding process particularly for large systems or long molecular dynamics simulations. Machine learning approaches offer the potential to bypass this iterative cycle by learning the mapping from atomic structure directly to the electron density or total energy [15].

Recent research has demonstrated that machine learning can approximate the Hohenberg-Kohn map—the mapping from external potential to electron density—directly, circumventing the need to solve the Kohn-Sham equations through the self-consistent field procedure [15]. This ML-HK map approach can be expressed as: [ n^{\text{ML}}v = \sum{i=1}^M \betai(\mathbf{x}) k(v, vi) ] where βi(x) are model weights and k(v, vi) is a kernel function measuring similarity between potentials [15]. For practical implementation in three-dimensional systems, a basis function representation is employed: [ n^{\text{ML}}v = \sum{l=1}^L u^{(l)}[v] \phil(\mathbf{x}) ] where φl(x) are basis functions and u^(l)[v] are the basis coefficients predicted by the machine learning model [15].

This machine learning approach has been successfully applied to molecular dynamics simulations, capturing complex processes such as intramolecular proton transfer in malonaldehyde with accuracy comparable to traditional Kohn-Sham calculations but at substantially reduced computational cost [15]. The continued development of machine-learned density functionals holds the promise of enabling larger-scale and longer-time simulations that are currently prohibitive with conventional Kohn-Sham implementations.

Multiscale Modeling Frameworks

The integration of Kohn-Sham DFT within multiscale modeling frameworks represents another significant advancement in computational methodology. Such frameworks combine the accuracy of quantum mechanical methods for describing bond breaking and formation with the efficiency of classical approaches for treating large systems and long-range interactions. The ONIOM (Our own N-layered Integrated molecular Orbital and molecular Mechanics) method, for instance, employs DFT for high-precision calculations of drug molecule core regions while using molecular mechanics force fields to model protein environments, resulting in substantial enhancement of computational efficiency without sacrificing accuracy in the critical regions [4].

Similarly, the integration of DFT with continuum solvation models enables realistic simulation of solution-phase environments, providing more accurate predictions for systems in biological or electrochemical contexts. The Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) method further extends the applicability of DFT to very large systems by decomposing the system into fragments and solving the Kohn-Sham equations for each fragment in the field of all others [4]. These multiscale approaches are particularly valuable in pharmaceutical applications where drug-receptor interactions involve localized chemical changes in large biomolecular environments.

The error in approximate DFT calculations can be separated into functional-driven error (due to approximations in the exchange-correlation functional) and density-driven error (due to inaccuracies in the self-consistent density) [15]. This distinction provides valuable insights for method development and allows for targeted improvements in functional design. Machine learning-enhanced functionals and multiscale approaches collectively address both sources of error, paving the way for more accurate and efficient Kohn-Sham calculations across diverse scientific domains.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has become a cornerstone computational method for investigating electronic structures in physics, chemistry, and materials science [1]. In the Kohn-Sham formulation of DFT, the intractable many-body problem of interacting electrons is reduced to a tractable single-body problem where the key challenge becomes accurately describing the exchange-correlation (XC) energy functional, which represents the quantum mechanical effects of electron-electron interactions beyond the classical electrostatic repulsion [16]. The accuracy of DFT calculations depends almost entirely on the approximations used for this XC functional, leading to the development of various classes of functionals with different levels of accuracy and computational cost [16].

This application note focuses on three fundamental classes of exchange-correlation functionals—Local Density Approximation (LDA), Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA), and Hybrid functionals—within the context of molecular modeling research for drug development. We provide a comprehensive comparison of these functional types, detailed protocols for their application in biological systems, and practical guidance for researchers seeking to employ DFT in computer-aided drug design (CADD).

Theoretical Foundations of Density Functional Theory

In the Kohn-Sham formulation of DFT, the total electronic energy is expressed as [16]:

[E{\rm tot}^{\rm DFT} = Ts + E{\rm ext} + E{\rm Hartree} + E{\rm xc} + E{\rm ion-ion}]

where (Ts) represents the kinetic energy of non-interacting electrons, (E{\rm ext}) is the electron-nuclear attraction energy, (E{\rm Hartree}) accounts for the classical electron-electron repulsion, (E{\rm xc}) is the exchange-correlation energy, and (E_{\rm ion-ion}) describes the nuclear repulsion. The Kohn-Sham equations are derived by minimizing this total energy functional, resulting in a set of single-particle equations:

[ \left(-\frac{1}{2}\nabla^{2} + V{\rm ext}({\bf r}) + V{\rm Hartree}({\bf r}) + V{\rm xc}({\bf r})\right)\psii({\bf r}) = \epsiloni\psii({\bf r}) ]

where (V{\rm xc} = \delta E{\rm xc}/\delta n({\bf r})) is the exchange-correlation potential [16]. The exact form of (E_{\rm xc}) remains unknown, and different approximation schemes have been developed, forming the hierarchy of functionals discussed in this application note.

Classes of Exchange-Correlation Functionals

Local Density Approximation (LDA)

The Local Density Approximation represents the simplest approach to approximating the exchange-correlation functional. LDA assumes that the exchange-correlation energy per electron at a point r in space equals that of a homogeneous electron gas with the same density [17]:

[ E{\rm xc}^{\rm LDA}[n] = \int n({\bf r}) \epsilon{\rm xc}^{\rm hom}(n({\bf r})) d^3r ]

where (\epsilon_{\rm xc}^{\rm hom}(n)) is the exchange-correlation energy per particle of a homogeneous electron gas of density (n). For the exchange part, this takes a simple analytical form proportional to (n^{1/3}), while the correlation part uses parameterizations based on quantum Monte Carlo simulations [17] [18].

Despite its simplicity, LDA suffers from several limitations. The approximation decays exponentially rather than with the correct Coulombic behavior, which affects the description of negative ions and the accuracy of ionization potential predictions via Koopmans' theorem [17]. While historically significant, LDA is rarely used nowadays for molecular systems due to its systematic errors, though it remains important as a component in more sophisticated functionals [17] [16].

Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA)

Generalized Gradient Approximations improve upon LDA by including the gradient of the electron density (\nabla n({\bf r})), thereby accounting for the non-uniformity of the true electron density [19]. The general form of the GGA functional is:

[ E{\rm xc}^{\rm GGA}[n] = \int \epsilon{\rm xc}^{\rm GGA}(n({\bf r}), \nabla n({\bf r})) d^3r ]

This inclusion of density gradients allows GGAs to better describe real systems with inhomogeneous electron distributions. GGAs are typically separated into exchange and correlation components, which can be mixed and matched. Popular GGA functionals include the PBE (Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof) functional, widely used in solid-state physics, and BLYP (Becke exchange with Lee-Yang-Parr correlation), commonly applied in quantum chemistry [20] [19].

The development of GGAs represented a significant advancement over LDA, with improved accuracy for molecular geometries and energetics while maintaining relatively low computational cost. However, the implementation of gradient corrections must carefully maintain the sum rule for the exchange-correlation hole to ensure physical meaningfulness [18].

Hybrid Functionals

Hybrid functionals incorporate a portion of exact Hartree-Fock (HF) exchange energy into the DFT exchange-correlation functional [16]. The general form for a hybrid functional is:

[ E{\rm xc}^{\rm hybrid} = \alpha E{\rm x}^{\rm HF} + (1-\alpha) E{\rm x}^{\rm SL} + E{\rm c}^{\rm SL} ]

where (\alpha) determines the fraction of HF exchange mixed with semilocal (SL) exchange, and (E_{\rm c}^{\rm SL}) represents the semilocal correlation functional. The inclusion of nonlocal HF exchange helps to reduce self-interaction error and improves the description of molecular properties such as reaction barriers and band gaps [16].

For periodic systems, range-separated hybrids like HSE06 are particularly valuable as they apply HF exchange only at short range, making them more computationally efficient for solids [16]. However, hybrid functionals are significantly more computationally expensive than semilocal functionals due to the need to calculate the nonlocal HF exchange.

Table 1: Comparison of Main Classes of Exchange-Correlation Functionals

| Functional Class | Dependence | Computational Cost | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDA | Local density (n({\bf r})) | Low | Simple, robust for metals | Overbinding, poor for molecules |

| GGA | Density and gradient (n({\bf r})), (\nabla n({\bf r})) | Low to Moderate | Improved geometries and energies | Underestimated band gaps |

| Hybrid | Orbitals (HF exchange) | High to Very High | Better reaction energies, band gaps | Computationally expensive |

| Meta-GGA | Density, gradient, kinetic energy density | Moderate | Better for diverse systems | Still underestimates weak interactions |

Performance Comparison and Selection Guidelines

Quantitative Comparison of Functional Performance

The performance of different XC functionals varies significantly across different chemical properties and systems. The table below summarizes typical performance characteristics for key molecular properties relevant to drug discovery applications.

Table 2: Functional Performance for Key Molecular Properties (Typical Error Trends)

| Property | LDA | GGA (PBE) | GGA (BLYP) | Hybrid (B3LYP) | Hybrid (HSE06) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Lengths | Too short by ~1-2% | Slightly long (~0.5-1%) | Slightly long (~0.5-1%) | Good (~0.5%) | Good for solids |

| Vibrational Frequencies | Too high (~5-10%) | Slightly low (~1-3%) | Slightly low (~1-3%) | Good (~1-2%) | Good for solids |

| Reaction Barriers | Poor | Underestimated (~10-15%) | Underestimated (~10-15%) | Good (~5-8%) | Good for solids |

| Band Gaps | Severely underestimated | Underestimated (~40%) | Underestimated (~40%) | Better but still low (~30%) | Good for semiconductors |

| Binding Energies | Overestimated | Variable | Underestimation of weak interactions | Improved but not perfect | Good for surface adsorption |

| Computational Cost | 1x | 1-2x | 1-2x | 10-100x | 5-50x |

Selection Guidelines for Drug Development Applications

Choosing an appropriate XC functional requires consideration of the target system and property of interest [16]:

For geometry optimizations of organic molecules: GGA functionals (particularly PBE or BLYP) often provide a good balance between accuracy and computational efficiency.

For reaction energies and barrier heights: Hybrid functionals (such as B3LYP or PBE0) typically yield more reliable results due to improved treatment of exchange.

For periodic systems and solids: PBE (GGA) remains widely used, while HSE06 (screened hybrid) provides improved band gaps and reaction energies for semiconductors.

For non-covalent interactions (critical in drug-receptor binding): Specialized functionals with empirical dispersion corrections (e.g., DFT-D3) are essential, as standard semilocal functionals poorly describe van der Waals forces [1].

For large systems (e.g., protein-ligand complexes): Semiempirical methods or GGA functionals may be the only practical choice, though QM/MM approaches can enable higher accuracy for the region of interest [21].

Computational resources also heavily influence functional selection. Hybrid functionals can be orders of magnitude more expensive than GGAs, making them prohibitive for large systems without specialized computational resources [16].

Experimental Protocols for Drug Development Applications

Protocol 1: Quantum Mechanical Scoring in Molecular Docking

Purpose: To improve binding affinity predictions in molecular docking through more accurate quantum mechanical scoring [21].

Workflow:

Initial Docking: Perform conventional molecular docking using force-field based scoring functions to generate candidate ligand poses.

Cluster Selection: Select representative structures from docking poses, focusing on diverse binding modes and high-scoring candidates.

QM Preparation:

- Extract the ligand and key receptor residues (typically within 5-8Ã… of the ligand)

- Cap terminal residues with methyl groups or hydrogen atoms

- Ensure proper protonation states for ionizable residues

Geometry Optimization:

- Method: GGA functional (PBE or BLYP) with dispersion correction (D3)

- Basis Set: Double-zeta plus polarization (DZP) quality

- Convergence: Energy tolerance of 10^-6 eV, force tolerance of 0.002 eV/Ã…

Single-Point Energy Calculation:

- Method: Hybrid functional (B3LYP or PBE0) with dispersion correction

- Basis Set: Triple-zeta quality with polarization functions

- Calculate absolute binding energies for rank-ordering candidates

Validation: Compare predictions with experimental binding data where available.

Applications: This protocol has been successfully applied to rank-order diverse ligands for SARS-CoV-2 main protease using DFT calculations on models with nearly 3000 atoms [21].

Protocol 2: pKa Prediction for Ionizable Groups

Purpose: To predict pKa values of ionizable groups in drug-like molecules using QM-based workflows [21].

Workflow:

System Preparation:

- Generate optimized geometries for both protonated and deprotonated forms

- Include explicit solvation shells for critical hydrogen bonds

- Employ implicit solvation model (e.g., COSMO-RS) for bulk solvent effects

Energy Calculations:

- Method: GGA or hybrid functional (depending on system size)

- Basis Set: Augmented double-zeta or triple-zeta basis sets

- Calculate free energy differences between protonated and deprotonated states

Reference Data:

- Use experimental pKa values for similar compounds

- Establish linear relationship between computed properties (e.g., atomic charges) and experimental pKa values

Prediction:

- Apply established correlation to predict pKa for novel compounds

- Account for statistical uncertainties in the correlation

Applications: Recent workflows by Grimme's group enable widely applicable pKa prediction based on a new cubic free energy relationship equation [21].

Diagram 1: DFT Calculation Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the general workflow for DFT calculations, highlighting key decision points in functional selection and the iterative nature of the self-consistent field (SCF) convergence process.

Advanced Methods and Emerging Trends

Meta-GGA Functionals

Meta-GGAs represent the next rung in Jacob's Ladder of DFT functionals, incorporating additional dependence on the kinetic energy density (\tau) or the Laplacian of the electron density (\nabla^2 n) [20] [16]:

[ E{\rm xc}^{\rm MGGA} = \int \epsilon{\rm xc}^{\rm MGGA}(n({\bf r}), \nabla n({\bf r}), \nabla^2 n({\bf r}), \tau({\bf r})) d^3r ]

This additional information allows meta-GGAs to detect the local bonding character and reduce self-interaction errors. Functionals like SCAN (Strongly Constrained and Appropriately Normed) provide improved accuracy for diverse systems including molecules and solids [16]. Meta-GGAs remain computationally efficient compared to hybrid functionals while often outperforming GGAs for reaction energies and structural properties.

Dispersion Corrections

Standard semilocal DFT functionals poorly describe dispersion (van der Waals) interactions, which are crucial for biological systems and drug-receptor binding [1]. Empirical dispersion corrections, such as the Grimme D3 method, add a simple pair-wise correction term to account for these missing interactions:

[ E{\rm disp} = -\frac{1}{2}\sum{A\neq B}\sum{n=6,8,\ldots}sn\frac{Cn^{AB}}{R{AB}^n}f{d,n}(R{AB}) ]

where (Cn^{AB}) are dispersion coefficients for atom pairs, (sn) are scaling factors, and (f_{d,n}) are damping functions [20]. These corrections significantly improve the description of non-covalent interactions with minimal computational overhead.

Machine-Learned Functionals

Recent advances include the development of machine-learned exchange-correlation functionals, such as the MCML (multi-purpose, constrained, and machine-learned) functional [18]. These functionals are trained on high-level quantum chemical data and experimental benchmarks, potentially offering improved accuracy across diverse chemical systems. However, challenges remain in ensuring transferability and satisfying important physical constraints.

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Resources for DFT in Drug Development

| Resource | Type | Key Features | Application in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP | DFT Software | Comprehensive materials science focus, efficient periodic calculations | Solid-formulation studies, enzyme active site modeling |

| ADF | DFT Software | Molecular DFT focus, advanced functionals | Ligand property prediction, spectroscopic modeling |

| Gaussian | Quantum Chemistry | Extensive method library, user-friendly | Ligand parameterization, QSAR descriptor calculation |

| Q-Chem | Quantum Chemistry | Advanced functionals, efficient algorithms | Large-scale biological system calculations |

| GFN2-xTB | Semiempirical Method | Fast, applicable across periodic table | Conformer generation, high-throughput screening |

| CREST | Conformer Sampling | GFN2-xTB based, iterative conformational search | Ligand conformer ensemble generation |

| DLPNO-CCSD(T) | Wavefunction Method | Highly accurate, linear scaling | Benchmark calculations for binding energies |

Exchange-correlation functionals form the fundamental approximation in DFT calculations and must be carefully selected based on the target application in drug development. LDA provides a historical foundation but limited accuracy for molecular systems. GGA functionals offer a practical balance of efficiency and accuracy for many applications, while hybrid functionals deliver improved performance for reaction energies and electronic properties at significantly higher computational cost. Emerging approaches, including meta-GGAs and machine-learned functionals, show promise for further improving the accuracy and applicability of DFT in pharmaceutical research.

As computational resources continue to grow and methods evolve, DFT approaches are increasingly integrated into drug discovery pipelines, providing valuable insights into ligand properties, binding interactions, and reaction mechanisms that complement experimental approaches in modern drug development.

Conceptual Density Functional Theory (CDFT) has emerged as a valuable complementary approach in modern drug discovery, providing a robust theoretical framework for understanding and predicting chemical reactivity at the molecular level. As a development from Density Functional Theory, CDFT employs both global and local chemical reactivity descriptors that facilitate the study of chemical reactions and how drugs affect their targets [22]. This methodology enables researchers to predict electronic properties of drug candidates, which simplifies the optimization of critical characteristics such as binding affinity and selectivity [22]. The fundamental principle of CDFT lies in its ability to describe the chemical reactivity of systems through response functions derived from the electron density, making it particularly valuable for pharmaceutical applications where understanding molecular interactions is crucial for rational drug design [23].

The significance of CDFT in drug development stems from its capacity to bridge theoretical calculations with practical pharmaceutical applications. By providing insights into the electronic driving forces governing molecular interactions, CDFT aids in exploring and analyzing specific inhibitors while predicting potential negative effects these inhibitors may exert [22]. When integrated with other computational approaches such as molecular docking and QSAR modeling, CDFT significantly strengthens the entire drug discovery pipeline, potentially reducing development cycles and improving success rates in identifying viable drug candidates [22] [4].

Theoretical Framework and Key Reactivity Descriptors

Global Reactivity Descriptors

Global descriptors within the CDFT framework provide overarching information about a molecule's intrinsic reactivity tendencies, serving as fundamental indicators for initial drug candidate assessment. These descriptors are derived from the electronic structure of molecules and have demonstrated significant predictive power in pharmaceutical applications [22] [23].

Table 1: Key Global Reactivity Descriptors in CDFT-Based Drug Design

| Descriptor | Mathematical Definition | Chemical Interpretation | Role in Drug Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronegativity (χ) | χ = - (EHOMO + ELUMO)/2 | Measures the tendency of a chemical species to attract electrons | Predicts charge transfer capabilities in drug-target interactions [24] |

| Global Hardness (η) | η = (ELUMO - EHOMO)/2 | Quantifies resistance to electron charge transfer | Indicates molecular stability; harder molecules are more stable [24] |

| Electrophilicity (ω) | ω = μ²/(2η) where μ = -χ | Measures the energy lowering due to electron acquisition | Assesses binding propensity; higher ω suggests stronger electrophilic character [24] |

| Electrodonating Power (ωâ») | ω⻠= (3EHOMO + ELUMO)²/(16η) | Quantifies the ability to donate electrons | Predicts nucleophilic behavior in biological environments [24] |

| Electroaccepting Power (ωâº) | ω⺠= (EHOMO + 3ELUMO)²/(16η) | Quantifies the ability to accept electrons | Predicts electrophilic behavior in biological environments [24] |

| Net Electrophilicity (Δω±) | Δω± = ω⺠+ ω⻠| Comprehensive electrophilicity measure | Provides overall reactivity profile for drug-target interactions [24] |

The application of these global descriptors in drug discovery is exemplified in the study of Taltobulin, an anticancer peptide, where calculated values provided crucial insights into its chemical behavior. For this molecule, electronegativity (χ) was determined to be 3.986 eV, global hardness (η) was 4.507 eV, electrophilicity (ω) was 1.763 eV, electrodonating power (ωâ») was 5.800 eV, electroaccepting power (ωâº) was 1.814 eV, and net electrophilicity (Δω±) was 7.614 eV [24]. The significantly higher electrodonating power compared to electroaccepting power indicated this molecule's stronger tendency to donate electrons in biological interactions, a crucial factor in understanding its mechanism of action as a microtubule disruptor [24].

Local Reactivity Descriptors

While global descriptors provide overall molecular reactivity trends, local reactivity descriptors offer site-specific information essential for understanding precise interaction mechanisms between drugs and their biological targets. These descriptors identify specific atoms or regions within a molecule that are most susceptible to nucleophilic or electrophilic attacks, providing critical insights for rational drug design [22] [24].

Table 2: Local Reactivity Descriptors in CDFT-Based Drug Design

| Descriptor | Mathematical Definition | Chemical Interpretation | Application in Drug Design | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrophilic Fukui Function (fâ»(r)) | fâ»(r) = ÏN(r) - ÏN-1(r) | Measures sensitivity to nucleophilic attack | Identifies sites susceptible to oxidation or electrophilic modification [24] | ||||

| Nucleophilic Fukui Function (fâº(r)) | fâº(r) = ÏN+1(r) - ÏN(r) | Measures sensitivity to electrophilic attack | Identifies sites susceptible to reduction or nucleophilic modification [24] | ||||

| Dual Descriptor (Δf(r)) | Δf(r) = fâº(r) - fâ»(r) | Distinguishes nucleophilic/electrophilic regions | Reveals sites with ambiphilic character; positive values indicate nucleophilic sites, negative values electrophilic sites [24] | ||||

| Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) | V(r) = Σ[ZA/ | RA - r | ] - ∫[Ï(r')/ | r - r' | ]dr' | Maps electrostatic potential around molecule | Predicts drug-target binding sites through electrostatic complementarity [4] |

The practical implementation of local descriptors is powerfully illustrated in the Taltobulin study, where the electrophilic and nucleophilic Fukui functions were calculated and visualized, clearly identifying the molecular active sites associated with nucleophilic and electrophilic regions [24]. This analysis provides critical information for understanding how this anticancer peptide interacts with its biological target, tubulin, and offers insights for designing more effective analogs through targeted molecular modifications.

Computational Protocols and Methodologies

Workflow for CDFT-Based Drug Reactivity Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive protocol for applying CDFT in drug reactivity studies, integrating both global and local descriptor calculations:

CDFT Reactivity Analysis Workflow

Step-by-Step Computational Protocol

Phase 1: Molecular Structure Preparation

- Input Generation: Begin with Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry Specification (SMILES) strings of the drug candidate [24].

- 3D Structure Generation: Utilize ChemAxon Calculator Plugins (e.g., Marvin View 17.15.0) to generate initial 3D structures from SMILES strings [24].

- Conformer Search: Employ conformer search algorithms to propose low-energy conformers for structure property prediction and calculation. Select the five lowest energy conformers for further analysis [24].

Phase 2: Geometry Optimization

- Preliminary Optimization: Optimize geometries of selected conformers using the Density Functional Tight Binding Model A (DFTBA) program as implemented in Gaussian 09 [24].

- Advanced Optimization: Reoptimize molecular structures using the MN12SX density functional with the Def2TZVP basis set, incorporating solvation effects (e.g., Hâ‚‚O via appropriate solvation models) [24].

- Stationary Point Verification: Perform vibrational frequency analysis to confirm optimized structures represent real minima (no imaginary frequencies) [24].

Phase 3: Electronic Structure Calculation

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: Conduct ground-state calculation with the MN12SX/Def2TZVP/H2O model chemistry to obtain molecular orbital energies [24].

- HOMO-LUMO Gap Determination: Calculate the energy difference between frontier molecular orbitals as an estimation of the lowest excitation energy [24].

Phase 4: Reactivity Descriptor Computation

Global Descriptor Calculation: Compute global reactivity descriptors using Koopmans in DFT (KID) procedure:

- Electronegativity: χ = - (EHOMO + ELUMO)/2

- Global Hardness: η = (ELUMO - EHOMO)/2

- Electrophilicity: ω = μ²/(2η) where μ = -χ

- Electrodonating and Electroaccepting Powers [24]

Local Descriptor Calculation: Calculate local reactivity descriptors:

- Fukui functions (nucleophilic and electrophilic)

- Dual descriptor

- Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) maps [24]

Phase 5: Bioactivity Assessment

Drug-likeness Evaluation: Assess compliance with Lipinski's Rule of Five using Molinspiration software or similar tools, calculating:

- miLogP (octanol/water partition coefficient)

- TPSA (topological polar surface area)

- Hydrogen bond donors/acceptors

- Molecular weight

- Rotatable bonds [24]

Bioactivity Score Prediction: Determine bioactivity scores for various drug targets including GPCR ligands, ion channel modulators, kinase inhibitors, nuclear receptor ligands, protease inhibitors, and enzyme inhibitors [24].

Application Notes: Case Studies in Drug Design

Case Study 1: Taltobulin Anticancer Peptide

The application of CDFT to Taltobulin (HTI-286), a synthetic analogue of hemiasterlin and potent tumor growth inhibitor, demonstrates the practical utility of this methodology in anticancer drug development [24].

Experimental Results and Interpretation:

The CDFT analysis of Taltobulin revealed a HOMO energy of -6.240 eV and LUMO energy of -1.733 eV, resulting in a HOMO-LUMO gap of 4.507 eV, which corresponds to an absorption wavelength maximum (λ_max) of 275 nm [24]. The global descriptor calculations indicated significantly higher electrodonating power (5.800 eV) compared to electroaccepting power (1.814 eV), suggesting this molecule's primary reactivity involves electron donation in biological systems [24].

Drug-likeness assessment using Lipinski's Rule of Five demonstrated zero violations, with key parameters including miLogP = 4.43, TPSA = 98.73, 7 hydrogen bond acceptors, 3 hydrogen bond donors, 11 rotatable bonds, molecular volume of 479.94, and molecular weight of 473.66 [24]. Bioactivity scores predicted particularly strong protease inhibitor activity (0.68), along with potential as a GPCR ligand (0.43) and enzyme inhibitor (0.42) [24].

Case Study 2: COVID-19 Drug Discovery

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the application of CDFT and DFT methodologies in antiviral drug discovery, particularly targeting SARS-CoV-2 proteins [25].

Key Targets and Methodological Approaches:

Main Protease (Mpro) Inhibition: CDFT studies focused on understanding inhibition mechanisms of compounds targeting the Cys-His catalytic dyad of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7) [25]. Researchers applied CDFT to study electronic properties of natural products (embelin, hypericin, naringin), repurposed pharmaceuticals (lopinavir, galidesivir, amodiaquine), and newly synthesized compounds [25].

RdRp Inhibitor Analysis: For RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (PDB ID: 6XEZ), CDFT helped elucidate the inhibition mechanisms of nucleotide analogs like remdesivir, the first FDA-approved COVID-19 antiviral drug [25]. Studies examined how structural modifications affect electronic properties and binding capabilities.

Nanocarrier Design: DFT calculations assessed the properties of drug delivery systems such as C60 fullerene and metallofullerenes as potential carriers for COVID-19 pharmaceuticals [25].

Integration with Multiscale Modeling

Advanced applications combine CDFT with multiscale computational paradigms to enhance both accuracy and efficiency:

- QM/MM Approaches: The ONIOM framework employs DFT for high-precision calculations of drug molecule core regions while using molecular mechanics force fields to model protein environments [4].

- Machine Learning Integration: Deep learning-augmented DFT frameworks, such as Deep post-Hartree-Fock (DeePHF), integrate neural networks with quantum mechanical descriptors to achieve coupled-cluster level precision while maintaining DFT efficiency [8]. These models establish mappings between eigenvalues of local density matrices and high-level correlation energies, significantly improving reaction energy and barrier height predictions [8].

- Reaction Yield Prediction: Atomic charges derived from DFT calculations train geometric deep learning models that successfully predict reaction yields and regioselectivity of drug molecules, with demonstrated applications in pharmaceutical industry settings [4].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for CDFT in Drug Design

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Package | Key Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Gaussian 09 [24] | Geometry optimization, frequency analysis, electronic structure calculation | Primary CDFT descriptor computation |

| VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO [7] | Solid-state calculations, periodic systems | Nanomaterial-based drug delivery systems | |

| Structure Generation & Visualization | ChemAxon Marvin View [24] | 3D structure generation from SMILES, conformer search | Initial molecular model preparation |

| Drug-likeness Prediction | Molinspiration Software [24] | Calculation of Ro5 parameters, bioactivity scores | Drug candidate prioritization |

| Multiscale Simulation | ONIOM [4] | Combined QM/MM calculations | Drug-target interaction studies |

| Machine Learning Integration | DeePHF [8] | ML-corrected DFT calculations | High-accuracy reaction modeling |

| Solvation Models | COSMO [4] | Implicit solvation treatment | Physiological environment simulation |

Conceptual DFT has established itself as an indispensable tool in modern drug discovery, providing crucial insights into chemical reactivity that guide rational drug design. The integration of CDFT with experimental validation and complementary computational approaches creates a powerful framework for accelerating pharmaceutical development. As methodological advances continue to emerge, particularly in machine learning-augmented DFT and multiscale modeling, the accuracy, efficiency, and applicability of CDFT in drug design are expected to expand further [4] [8].

Future developments will likely focus on overcoming current challenges in modeling complex biological environments, dynamic non-equilibrium processes, and achieving optimal balance between computational cost and accuracy in multicomponent systems [4]. The ongoing refinement of exchange-correlation functionals, coupled with increasingly sophisticated machine learning approaches, promises to enhance the predictive power of CDFT calculations, making them even more valuable tools in the pharmaceutical researcher's arsenal [9] [8].

From Theory to Therapy: DFT Protocols in Drug Discovery Workflows

Best-Practice Computational Protocols for Robust DFT Calculations

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has firmly consolidated its position as a fundamental workhorse in computational chemistry, providing an outstanding effort-to-insight and cost-to-accuracy ratio for investigating molecular structures, reaction energies, barrier heights, and spectroscopic properties [26]. Its application enables rational design of molecules and materials in areas ranging from drug development to new catalyst systems. However, the vast number of available methodological combinations presents a significant challenge for researchers seeking robust computational protocols. This Application Note establishes best-practice methodologies for DFT calculations, focusing on achieving an optimal balance between accuracy, robustness, and computational efficiency, particularly within molecular modeling research for drug development applications.

Decision Framework for Computational Protocol Selection