DFT vs Post-Hartree-Fock: A Comprehensive Accuracy Assessment for Computational Chemistry and Drug Discovery

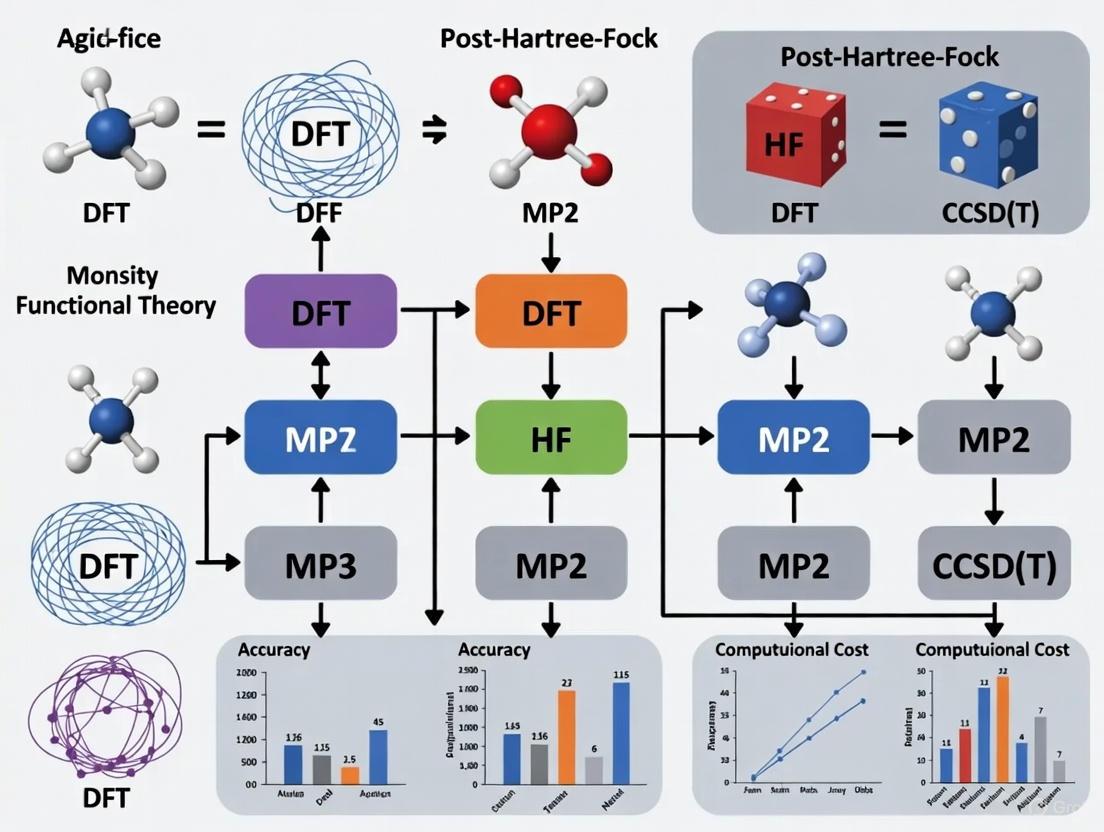

This article provides a systematic assessment of the accuracy of Density Functional Theory (DFT) versus post-Hartree-Fock (post-HF) methods, crucial for reliable predictions in drug development and materials science.

DFT vs Post-Hartree-Fock: A Comprehensive Accuracy Assessment for Computational Chemistry and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a systematic assessment of the accuracy of Density Functional Theory (DFT) versus post-Hartree-Fock (post-HF) methods, crucial for reliable predictions in drug development and materials science. We explore the foundational principles behind the accuracy-efficiency trade-off, detail advanced methodologies including machine learning corrections like DeePHF, address common troubleshooting scenarios and systematic errors, and present rigorous validation through benchmark studies and specific case examples, such as zwitterionic systems where HF can outperform DFT. The synthesis offers clear guidance for selecting appropriate computational strategies and highlights emerging trends that promise to bridge the accuracy gap for biomedical applications.

The Quantum Chemistry Landscape: Unpacking the Accuracy-Efficiency Trade-off between DFT and Post-HF

The Hartree-Fock (HF) method is a foundational approximation technique in computational physics and chemistry for determining the wave function and energy of a quantum many-body system in a stationary state [1]. It simplifies the intractable many-electron Schrödinger equation by treating each electron as moving independently within an average field, or mean-field, created by all other electrons [2]. This self-consistent field approach provides a workable solution for multi-electron systems [1]. Despite its historical importance and utility, the HF method possesses a fundamental limitation: its incomplete description of electron correlation. This article explores the core principles of the HF method, details its electron correlation problem, and objectively compares its performance against post-Hartree-Fock and Density Functional Theory (DFT) methods, providing researchers with a clear understanding of their respective accuracies and trade-offs.

Core Principles of the Hartree-Fock Method

Theoretical Foundation and Key Approximations

The HF method rests on several key simplifications to make the many-body problem computationally feasible [1]:

- The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation: It assumes the nuclei are fixed in space, separating electronic and nuclear motion.

- The Single-Determinant Wave Function: For fermions, the many-electron wave function is approximated by a single Slater determinant of one-electron spin-orbitals. This form ensures the wave function is antisymmetric, satisfying the Pauli exclusion principle [1].

- The Mean-Field Approximation: The complex, instantaneous repulsive interactions between electrons are replaced with an average effective field. This means each electron feels a static field from the smoothed-out charge distribution of all other electrons [1] [2].

The variational principle is applied to this Slater determinant, leading to the Hartree-Fock equations. These equations are solved iteratively in a procedure known as the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) method, where the equations are solved repeatedly until the solutions no longer change, indicating a self-consistent solution has been found [1].

The Self-Consistent Field Algorithm

The practical implementation of the HF method follows a systematic algorithm [1]:

Table 1: The Hartree-Fock Self-Consistent Field Algorithm

| Step | Action | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initial Guess | Choose an initial set of approximate one-electron spin-orbitals. |

| 2 | Construct Fock Operator | Build the effective one-electron Hamiltonian (Fock operator) using the current orbitals. |

| 3 | Solve HF Equations | Solve the eigenvalue problem to obtain a new set of orbitals and energies. |

| 4 | Check Convergence | Determine if the orbitals or total energy have converged within a specified threshold. |

| 5 | Iterate | If not converged, use the new orbitals to construct a new Fock operator and repeat from Step 2. |

Diagram 1: The Hartree-Fock self-consistent field procedure.

The Electron Correlation Problem

Defining Electron Correlation

The central failure of the HF method is its neglect of electron correlation. Electron correlation is defined as the energy difference between the exact solution of the non-relativistic Schrödinger equation and the Hartree-Fock result in the complete basis set limit [3] [4]. The HF mean-field approach accounts for exchange interactions (Fermi correlation) but fails to describe the Coulomb correlation—the tendency of electrons to avoid each other due to their mutual repulsion. In HF theory, an electron only feels the average position of others, not their instantaneous, correlated motions.

Consequences and Systematic Failures

This lack of electron correlation leads to predictable and sometimes qualitative failures [4]:

- Overestimation of Total Energy: The HF energy is always higher than the true ground-state energy.

- Poor Description of Bond Breaking: Restricted HF (RHF) fails dramatically when chemical bonds are stretched. For example, in Hâ‚‚ dissociation, RHF incorrectly predicts a mixture of H and Hâ»/Hâº, yielding a severely inaccurate dissociation energy [4].

- Inability to Describe Dispersion Forces: The HF method completely fails to capture London dispersion, a weak attraction entirely arising from electron correlation [1] [5]. This makes it unsuitable for modeling non-covalent interactions like van der Waals forces.

- Failure in Strongly Correlated Systems: Systems with near-degenerate electronic states (e.g., singlet Oâ‚‚, transition metal oxides, and some radicals) are poorly described by a single Slater determinant, leading to incorrect electronic structures and energies [4].

Beyond Hartree-Fock: Post-HF and DFT Methods

To address the electron correlation problem, two major families of methods have been developed: post-Hartree-Fock methods and Density Functional Theory.

Post-Hartree-Fock Methods

Post-Hartree-Fock (post-HF) methods build upon the HF wavefunction to incorporate electron correlation [3]. They systematically improve accuracy at a significantly increased computational cost.

Table 2: Key Post-Hartree-Fock Methods for Electron Correlation

| Method | Description | Accounts for Correlation | Typical Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (MP2) | Treats correlation as a perturbation to the HF Hamiltonian. | Dynamical | Nⵠ|

| Coupled Cluster (CCSD(T)) | Forms a wavefunction using an exponential ansatz; "gold standard" for molecular energies. | Dynamical | Nâ· |

| Configuration Interaction (CISD) | Constructs wavefunction as a linear combination of Slater determinants. | Dynamical (limited) | Nⶠ|

| Complete Active Space SCF (CASSCF) | Uses a multi-determinant wavefunction for a selected set of orbitals; good for degenerate states. | Static & Dynamical | Exponential |

Density Functional Theory

Density Functional Theory (DFT) takes a different approach by using the electron density, rather than a wave function, as the fundamental variable [6]. Its accuracy depends critically on the approximation used for the exchange-correlation (XC) functional, a universal but unknown term that must be approximated. Traditional functionals like GGAs often fail for dispersion interactions and systems with localized electrons, but modern hybrids and dispersion-corrected functionals have broadened DFT's applicability [5] [6].

Performance Comparison: Accuracy Assessment

Quantitative Benchmarking of Methodologies

The performance of quantum chemical methods is typically assessed by benchmarking computed properties—such as interaction energies, bond lengths, and spectroscopic constants—against highly accurate experimental data or results from high-level wavefunction methods like CCSD(T).

Table 3: Performance Comparison for Aurophilic Interaction [ClAuPH₃]₂ [5]

| Computational Method | Au-Au Distance (Ã…) | Interaction Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| HF | 4.180 (No binding) | ~0 (Fails to bind) |

| MP2 | 3.050 | -54.8 |

| SCS-MP2 | 3.231 | -43.5 |

| CCSD(T) | 3.241 | -42.3 |

| PBE DFT (without dispersion) | 3.841 (No binding) | ~0 (Fails to bind) |

| PBE DFT with D3 dispersion | 3.120 | -52.3 |

| Experimental Reference | ~3.00 - 3.40 | ~30 - 50 |

Table 4: Performance for Zwitterion Dipole Moment (Debye) [7]

| Method | Dipole Moment (D) | Error vs. Experiment (10.33 D) |

|---|---|---|

| HF | 10.37 | 0.04 |

| B3LYP (DFT) | 12.95 | 2.62 |

| CAM-B3LYP (DFT) | 11.64 | 1.31 |

| MP2 (post-HF) | 10.29 | -0.04 |

| CCSD (post-HF) | 10.30 | -0.03 |

Table 5: General Performance and Resource Profile

| Method | Typical Energy Error (kcal/mol) | Computational Cost | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF | 10 - 100+ | Nâ´ (Low) | Good structures; foundational for post-HF. | No dispersion; fails for bond breaking. |

| MP2 | 5 - 10 | Nâµ (Medium) | Good for non-covalent interactions. | Over-binds; sensitive to system type. |

| CCSD(T) | < 1 | Nâ· (Very High) | "Gold standard" for energy. | Prohibitively expensive for large systems. |

| GGA DFT (e.g., PBE) | 5 - 15 | N³ (Low) | Fast; good for solids and geometries. | Poor band gaps; fails for dispersion. |

| Hybrid DFT (e.g., B3LYP) | 2 - 10 | Nâ´ (Medium) | Versatile; workhorse for molecular properties. | Costlier than GGA; accuracy not guaranteed. |

Case Study: Noncovalent Interactions and Dispersion

Noncovalent interactions starkly reveal the limitations of HF and basic DFT. As shown in Table 3, HF fails to bind the [ClAuPH₃]₂ dimer, showing no aurophilic attraction because the interaction is dominated by dispersion [5]. MP2 captures the interaction but tends to overbind, while SCS-MP2 and CCSD(T) provide results closer to experiment. DFT with an empirical dispersion correction (D3) performs remarkably well in this case, rivaling MP2 accuracy at a lower cost.

Case Study: Zwitterions and Self-Interaction Error

In a study on zwitterionic molecules, HF unexpectedly outperformed many DFT functionals in reproducing the experimental dipole moment (Table 4) [7]. This was attributed to the localization issue of HF being advantageous for these specific systems, countering the delocalization error common in many DFT functionals. This highlights that HF can still be the preferred method for certain chemical problems, and that modern DFT is not universally superior.

Experimental Protocols for Method Benchmarking

To objectively compare the performance of different quantum chemical methods, rigorous benchmarking protocols are essential.

High-Accuracy Wavefunction Benchmarks

For generating reference data, high-accuracy wavefunction methods are employed [6] [8]:

- Reference Dataset Curation: A set of molecules with well-established experimental or high-level theoretical properties is selected. Examples include the W4-17 dataset for thermochemistry.

- High-Level Computation: Methods like CCSD(T) are run with very large basis sets (approaching the complete basis set limit) to generate highly accurate reference energies and geometries.

- Error Statistical Analysis: The performance of lower-level methods (HF, DFT, MP2) is assessed by calculating the mean absolute error (MAE), root-mean-square error (RMSE), and maximum deviations from the reference dataset.

Geometry Optimization and Single-Point Energy Protocols

A common workflow for assessing methods is [5]:

- Geometry Optimization: Molecular structures are fully optimized using the method under investigation (e.g., B3LYP, MP2, HF).

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: At the optimized geometry, a more accurate but computationally expensive method (e.g., CCSD(T)) is used to compute the final energy. This separates the error in the geometry from the error in the energy evaluation.

- Intermolecular Distance Analysis: For noncovalent complexes, dissociation curves are calculated, and the equilibrium intermolecular distance is compared to reference data to evaluate a method's geometric accuracy [8].

Diagram 2: Standard workflow for benchmarking computational chemistry methods.

Table 6: Key Software and Computational Resources

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian 09/16 | Software Suite | General-purpose quantum chemistry package for HF, post-HF, and DFT. | Industry standard for molecular quantum chemistry calculations [7]. |

| FHI-aims | Software Suite | All-electron DFT code with high accuracy for materials science. | Used for generating high-accuracy databases with hybrid functionals [9]. |

| ORCA | Software Suite | Powerful and versatile quantum chemistry package. | Widely used for DFT and wavefunction-based calculations in academia [10]. |

| Psi4 | Software Suite | Open-source quantum chemistry package for HF, DFT, and post-HF. | Enables accessible, high-performance computational chemistry [10]. |

| CCSD(T)/CBS | Method/Basis Set | Coupled-Cluster with large basis sets; the benchmark "truth". | Provides the reference data for training ML models and benchmarking [6] [8]. |

| HSE06 | DFT Functional | Range-separated hybrid functional. | Provides more accurate electronic properties (e.g., band gaps) than GGA [9]. |

| def2-TZVPP | Basis Set | Triple-zeta quality Gaussian-type basis set. | Common choice for accurate molecular calculations balancing cost and accuracy [10]. |

| RIJCOSX | Computational Approximation | Accelerates evaluation of Coulomb and exchange integrals. | Can introduce numerical errors if not used carefully [10]. |

The Hartree-Fock method remains a cornerstone of quantum chemistry, providing the conceptual and computational foundation for more advanced post-HF and DFT methods. Its principal limitation is the neglect of electron correlation, leading to systematic inaccuracies in energies and failure for dispersion interactions and bond dissociation. Performance comparisons show a clear trade-off: post-HF methods like CCSD(T) offer high accuracy but at extreme computational cost, while DFT provides a versatile and efficient alternative whose accuracy is highly dependent on the chosen functional. As computational power increases and new machine-learned functionals emerge, the gap between efficiency and high accuracy continues to narrow, promising a future with more reliable predictive power in computational drug design and materials science [6].

Defining Electron Correlation and Its Central Challenge

Electron correlation is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics that describes the interaction between electrons within a quantum system. It quantifies how the movement of one electron is influenced by the positions of all other electrons, a phenomenon not fully captured by the Hartree-Fock (HF) method [11]. In HF theory, each electron is assumed to move independently within a mean field created by all other electrons, neglecting their instantaneous Coulomb repulsion [11] [12]. The correlation energy is formally defined as the difference between the exact, non-relativistic energy of a system and its Hartree-Fock energy calculated with a complete basis set [11] [12].

This missing correlation energy is a major source of error in quantum chemical calculations and is traditionally categorized into two distinct types: dynamic correlation and static (nondynamical) correlation. Understanding the nature of, and difference between, these two types is crucial for selecting the appropriate computational method to accurately predict molecular properties, a key consideration in fields ranging from drug development to materials science [7] [13].

Static vs. Dynamic Correlation: A Comparative Analysis

While both static and dynamic correlations arise from the same physical origin—the Coulomb repulsion between electrons—they manifest in different ways and require different theoretical approaches for their correction. The table below summarizes their core distinctions.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Static and Dynamic Electron Correlation

| Feature | Static (Nondynamical) Correlation | Dynamic Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cause | Inability of a single Slater determinant to describe the wavefunction, often due to (near-)degenerate states [11] [12]. | Failure to describe the instantaneous, correlated motion of electrons avoiding each other due to Coulomb repulsion [11] [12]. |

| Physical Nature | Not related to electron dynamics; a qualitative error in the reference wavefunction [12]. | Directly related to the dynamic avoidance of electrons [12]. |

| Typical Situations | Bond breaking, diradicals, transition metal complexes, anti-ferromagnetic states [11]. | Accurate description of bond energies, dispersion forces, and electron affinities in stable molecules [11]. |

| Key Treatment Methods | Multi-configurational self-consistent field (MCSCF), Complete Active Space SCF (CASSCF) [11] [12]. | Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (e.g., MP2), Coupled-Cluster (e.g., CCSD), Configuration Interaction (CI) [11] [12]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the deficiencies of the Hartree-Fock method and the two types of electron correlation, along with the primary computational strategies used to address them.

Diagram 1: Correlation Types and Correction Methods.

Performance Assessment: DFT versus Post-Hartree-Fock Methods

The critical choice for a computational chemist is selecting a method that adequately captures the required correlation effects. Density Functional Theory (DFT) includes correlation effects via approximate functionals and scales favorably for larger systems, while post-Hartree-Fock (post-HF) methods add correlation systematically but at a higher computational cost [13]. Their performance is not universal and depends heavily on the chemical system and property of interest.

The Case of Zwitterionic Systems

A 2023 study provides a compelling example where traditional DFT functionals failed, while HF and advanced post-HF methods succeeded. The research investigated the structure and dipole moment of pyridinium benzimidazolate zwitterions [7].

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Zwitterion Dipole Moment (Experimental value: ~10.33 D)

| Method Category | Example Methods | Performance on Zwitterion |

|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | HF | Accurately reproduced experimental dipole moment; results were consistent with high-level post-HF methods [7]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | B3LYP, CAM-B3LYP, M06-2X, ωB97xD | Systematically overestimated the dipole moment; the delocalization error of DFT was detrimental [7]. |

| Post-Hartree-Fock | CCSD, CASSCF, CISD, QCISD | Showed very similar results to HF, confirming its reliability for this specific system [7]. |

The study concluded that the localization issue inherent to HF was advantageous for correctly describing the electronic structure of these charge-separated zwitterions, whereas the delocalization issue of DFT functionals led to poor performance [7].

Broad Benchmarking Studies

Large-scale assessments provide a broader view of method performance across diverse molecular properties. A critical survey evaluated 37 DFT methods, HF, and MP2 on properties including bond lengths, angles, vibrational frequencies, and reaction energies [13].

Table 3: Generalized Performance Across Common Molecular Properties

| Method | Typical Performance & Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Often underestimates bond lengths and overestimates vibrational frequencies and reaction barrier heights due to lack of electron correlation [13]. |

| DFT (Hybrid-meta-GGA) | Functionals like VSXC and TPSS were often among the most accurate for a wide range of properties, offering a good balance of accuracy and cost [13]. |

| MP2 | Generally provides good results for many properties but can be computationally expensive for large systems and fails for cases with strong static correlation [13]. |

This benchmarking highlights that hybrid-meta-GGA functionals often rank among the most accurate for a wide range of properties, offering a good balance between computational cost and accuracy for many biological and organic systems [13].

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Validating computational methods against experimental data is a cornerstone of computational chemistry. The following are generalized protocols based on the cited studies.

Protocol for Validating Molecular Properties

This protocol is modeled after the zwitterion study and benchmarking work [7] [13].

- System Selection: Choose molecules with well-established experimental data (e.g., crystal structures, dipole moments, thermodynamic properties). The test set should be chemically relevant to the intended application (e.g., drug-like molecules for pharmaceutical research).

- Computational Setup:

- Software: Use a standard quantum chemistry package (e.g., Gaussian 09, ORCA).

- Geometry Optimization: Perform a full geometry optimization for the target molecule(s) without symmetry constraints.

- Methodology: Employ a wide range of methods on the same molecular geometry. This typically includes:

- HF.

- Multiple DFT functionals (e.g., B3LYP, M06-2X, ωB97xD).

- Post-HF methods (e.g., MP2, CCSD, CASSCF) for benchmark-quality reference.

- Basis Set: Select an appropriate basis set (e.g., 6-31G*, cc-pVDZ) that balances accuracy and computational cost.

- Frequency Calculation: Perform a vibrational frequency calculation on the optimized geometry to confirm it is a true minimum (no imaginary frequencies) and to obtain vibrational properties.

- Property Calculation: Calculate the target properties (e.g., dipole moment, bond lengths, angles, energy) using the optimized geometry.

- Data Analysis: Compare computed results directly with experimental data. Statistical measures like mean absolute error (MAE) are used to assess the performance of each method across a test set.

Protocol for Testing Electron Correlation Models in Condensed Matter

Recent research on warm dense matter demonstrates validation in extreme conditions [14].

- Sample Preparation: Create a sample of the material under controlled conditions (e.g., warm dense aluminium at specific densities and temperatures using a high-power laser).

- Experimental Probe: Use high-resolution X-ray Thomson scattering to probe the plasmon dispersion across a range of momentum transfers.

- Theoretical Calculations: Simulate the same scattering spectra using different theoretical models, such as:

- Time-Dependent DFT (TDDFT).

- Random Phase Approximation (RPA).

- Static local-field-correction (LFC) models.

- Validation: Compare the simulated spectra (e.g., plasmon energies and line shapes) with the experimental measurements. A method is validated if it reproduces the experimental data across the full range of measured parameters [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

The table below details key "research reagents"—the computational methods and basis sets—essential for investigations in this field.

Table 4: Key Computational Tools for Electron Correlation Studies

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function & Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Wavefunction Theory | Provides a starting point, or reference, for post-HF methods. It includes exchange correlation but neglects all Coulomb correlation, making it a "reagent" for testing the need for correlation corrections [11]. |

| B3LYP | DFT (Hybrid-GGA) | A highly popular functional that mixes HF exchange with DFT exchange-correlation. It is a general-purpose "reagent" for systems where dynamic correlation dominates and computational cost is a concern [7] [13]. |

| MP2 | Post-HF | A "reagent" for adding a baseline level of dynamic correlation at a relatively low computational cost. It is often used for geometry optimizations and calculating interaction energies [13]. |

| CASSCF | Post-HF | The primary "reagent" for treating static correlation. It is used for multi-reference systems like diradicals or during bond cleavage where a single determinant is insufficient [11] [15]. |

| CCSD | Post-HF | A high-accuracy "reagent" for capturing dynamic correlation. It is often considered a "gold standard" for single-reference systems and is used for benchmark-quality energy calculations [7] [11]. |

| Pople-style Basis Sets | Basis Set | A family of basis sets (e.g., 6-31G*) that offer a good balance of accuracy and speed, making them a common "reagent" for calculations on medium-to-large organic molecules [13]. |

| Dunning-style Basis Sets | Basis Set | The correlation-consistent (cc-pVXZ) series. These are "reagents" designed for high-accuracy post-HF calculations, systematically approaching the complete basis set limit [13]. |

| 3-Quinoxalin-2-yl-1H-indole-5-carbonitrile | 3-Quinoxalin-2-yl-1H-indole-5-carbonitrile|High Purity | 3-Quinoxalin-2-yl-1H-indole-5-carbonitrile is a versatile research chemical for drug discovery. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| [(2,2-Difluoroethyl)carbamoyl]formic acid | [(2,2-Difluoroethyl)carbamoyl]formic acid, CAS:1461706-89-7, MF:C4H5F2NO3, MW:153.08 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Hartree-Fock (HF) method serves as the foundational starting point in computational quantum chemistry, providing an approximate solution to the many-electron Schrödinger equation. However, its critical limitation lies in the neglect of electron correlation—the instantaneous repulsive interactions between electrons—beyond the average field approximation. This simplification leads to systematically inaccurate predictions of molecular properties, including overestimation of bond energies and incorrect descriptions of reaction pathways and excited states. To overcome these limitations, a family of more sophisticated computational techniques known as post-Hartree-Fock methods has been developed, with Configuration Interaction (CI), Moller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (MP), and Coupled-Cluster (CC) theories representing the core hierarchy of these advanced approaches.

These post-HF methods share a common goal: to recover the electron correlation energy missing in Hartree-Fock calculations. Their development has been largely motivated by the need for systematically improvable computational methods that can approach the exact solution of the non-relativistic Schrödinger equation, limited only by computational resources. In the context of drug discovery and materials science, where accurate prediction of molecular interactions is paramount, understanding the capabilities and limitations of each method becomes essential for selecting the appropriate tool for a given chemical problem. As we assess these methods against the backdrop of Density Functional Theory (DFT), it is crucial to recognize that while DFT often provides an excellent cost-to-accuracy ratio, its approximations are not systematically improvable, creating a distinct niche for post-HF methods where high precision is required.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodologies

Configuration Interaction (CI) Theory

The Configuration Interaction method is based on a conceptually straightforward approach: expanding the many-electron wavefunction as a linear combination of Slater determinants constructed from the Hartree-Fock reference wavefunction.

[

\Psi{\text{CI}} = c0 \Phi0 + \sum{i,a} ci^a \Phii^a + \sum{i

In this expansion, ( \Phi0 ) represents the Hartree-Fock reference determinant, while ( \Phii^a ), ( \Phi_{ij}^{ab} ), etc., represent singly, doubly, etc. excited determinants where electrons have been promoted from occupied to virtual orbitals. The coefficients ( c ) are determined by diagonalizing the Hamiltonian matrix in the basis of these determinants, yielding a variational solution where the CI energy represents an upper bound to the exact energy [16].

In practical implementations, the full CI expansion—which includes all possible excitations—is computationally prohibitive for all but the smallest systems. The number of determinants grows factorially with both the number of electrons and the size of the basis set. Consequently, the CI expansion is typically truncated at specific excitation levels:

- CISD: Includes all single and double excitations. While computationally manageable for medium-sized systems, this truncation suffers from lack of size-extensivity, meaning the energy does not scale correctly with system size.

- CISDTQ: Includes single, double, triple, and quadruple excitations. This offers improved accuracy but at substantially increased computational cost.

- Full CI: Represents the exact solution within the given basis set, serving as a benchmark for other methods but remaining computationally feasible only for very small systems [16].

The lack of size-extensivity in truncated CI methods represents a significant limitation when studying molecular processes where energy differences between systems of different sizes are important, such as in binding energies or reaction energies.

Moller-Plesset Perturbation Theory

Moller-Plesset Perturbation Theory approaches the electron correlation problem from a different perspective, treating the correlation as a small perturbation to the Hartree-Fock Hamiltonian. Based on Rayleigh-Schrödinger perturbation theory, MP methods partition the Hamiltonian such that the zero-order wavefunction is the Hartree-Fock solution and the correlation energy is recovered through successive orders of correction [3].

The MP2 method represents the second-order correction and has become one of the most widely used post-HF methods due to its favorable balance between cost and accuracy. The MP2 correlation energy is given by:

[ E{\text{MP2}} = \frac{1}{4} \sum{ijab} \frac{|\langle ij || ab \rangle|^2}{\epsiloni + \epsilonj - \epsilona - \epsilonb} ]

where ( i,j ) and ( a,b ) index occupied and virtual molecular orbitals, respectively, ( \langle ij || ab \rangle ) represents the antisymmetrized two-electron integrals, and ( \epsilon ) are the orbital energies [3].

Higher-order corrections (MP3, MP4) provide progressively more accurate results but at significantly increased computational expense. Unlike truncated CI, the MP approach is size-extensive at every order, making it particularly valuable for comparing systems of different sizes. However, MP methods are not variational, meaning the calculated energy may fall below the exact energy, and the perturbation series does not always converge monotonically.

Coupled-Cluster Theory

Coupled-Cluster theory represents perhaps the most sophisticated and accurate among the commonly applied post-HF methods. It employs an exponential ansatz for the wavefunction:

[ \Psi{\text{CC}} = e^{T} \Phi0 ]

where ( T = T1 + T2 + T3 + \cdots ) is the cluster operator composed of single (( T1 )), double (( T2 )), triple (( T3 )), etc. excitation operators. This exponential form ensures size-extensivity even when the expansion is truncated [16].

The most common truncation levels in Coupled-Cluster calculations are:

- CCD: Includes only double excitations.

- CCSD: Includes single and double excitations.

- CCSD(T): Includes a perturbative treatment of triple excitations and is often referred to as the "gold standard" of quantum chemistry for single-reference systems due to its exceptional accuracy [17].

The computational cost of CC methods scales steeply with system size: CCSD formal scaling is ( O(N^6) ), while CCSD(T) scales as ( O(N^7) ), where N represents the number of basis functions. This limits their application to small and medium-sized molecular systems, though recent developments in periodic CC theory show promise for extending these methods to solid-state systems [18].

Table 1: Computational Scaling and Key Characteristics of Post-HF Methods

| Method | Computational Scaling | Size-Extensive? | Variational? | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF | ( O(N^3)-O(N^4) ) | Yes | Yes | Inexpensive, physically interpretable orbitals |

| MP2 | ( O(N^5) ) | Yes | No | Good balance of cost and accuracy for non-covalent interactions |

| MP4 | ( O(N^7) ) | Yes | No | More accurate than MP2 but more expensive |

| CISD | ( O(N^6) ) | No | Yes | Systematic improvement over HF |

| CCSD | ( O(N^6) ) | Yes | No | High accuracy for single-reference systems |

| CCSD(T) | ( O(N^7) ) | Yes | No | "Gold standard" for molecular energies |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Accuracy Assessment for Molecular Properties

The performance of post-HF methods can be quantitatively assessed by their ability to reproduce experimental molecular properties, particularly equilibrium bond lengths and energies. A comprehensive study comparing CO bond lengths across multiple organic molecules provides valuable insights into the relative accuracy of these methods [19].

In this benchmark study, researchers evaluated various quantum chemical methods against experimental gas-phase equilibrium CO bond lengths (râ‚‘ values). The results demonstrated clear hierarchies in predictive accuracy:

- Hartree-Fock typically underestimates bond lengths (produces bonds that are too short) due to incomplete accounting of electron correlation.

- MP2 generally provides good agreement with experimental values but can be sensitive to the basis set used, with larger basis sets required for quantitative accuracy.

- MP4(SDQ) shows improved performance over MP2, often yielding suitable results, though at significantly higher computational cost.

- CCSD(T) delivers excellent agreement with experimental values when paired with high-quality basis sets, justifying its "gold standard" reputation [19].

The study also highlighted the critical importance of basis set selection, finding that even sophisticated correlation methods like CCSD(T) require sufficiently flexible basis sets (typically triple-zeta or higher with polarization functions) to achieve their potential accuracy. This creates a practical constraint where the computational cost increases not only with the level of theory but also with the quality of the basis set employed.

Table 2: Performance Comparison for CO Bond Length Prediction [19]

| Method | Mean Absolute Error (Ã…) | Computational Cost | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| HF | 0.020-0.030 | Low | Qualitative trends, initial geometry scans |

| MP2 | 0.005-0.015 | Medium | Non-covalent interactions, moderate-sized systems |

| MP4 | 0.004-0.010 | High | Small system accuracy where CC is prohibitive |

| CCSD(T) | 0.001-0.005 | Very High | Benchmark quality for small molecules |

Comparison with Density Functional Theory

When evaluating post-HF methods within the broader context of quantum chemistry, comparison with Density Functional Theory is inevitable. Each approach presents distinct advantages and limitations:

Systematic Improvability: Post-HF methods offer a clear path toward higher accuracy through increased expansion levels (higher excitation levels in CI/CC, higher orders in MP) or improved basis sets. In contrast, DFT lacks this systematic improvability—there is no guaranteed way to improve a functional toward exactness [20] [7].

Computational Cost: DFT methods, particularly pure GGAs, typically scale formally as ( O(N^3)-O(N^4) ), making them applicable to much larger systems (hundreds to thousands of atoms) than most post-HF methods. Hybrid DFT functionals with exact exchange have higher computational costs but generally remain less expensive than correlated post-HF methods [21].

Accuracy Patterns: A notable study comparing HF and DFT for zwitterionic systems found that HF sometimes outperformed DFT methodologies in reproducing experimental dipole moments and structural parameters, with CCSD, CASSCF, CISD, and QCISD providing very similar results that validated the HF predictions. This demonstrates that system-specific factors can significantly influence method performance [7].

Strongly Correlated Systems: Post-HF methods typically excel in describing systems with strong electron correlation, such as bond breaking, transition metal complexes, and open-shell systems, where many DFT functionals struggle. Multi-reference methods like CASSCF, while computationally demanding, provide the most robust approach for these challenging cases [20].

Experimental Protocols and Computational Workflows

Standard Computational Procedure for Post-HF Calculations

Implementing post-HF calculations follows a systematic workflow to ensure numerically stable and physically meaningful results:

Geometry Pre-optimization: Initial molecular structures are typically optimized at the HF or DFT level to provide a reasonable starting geometry for higher-level calculations.

Basis Set Selection: Appropriate basis sets must be selected based on the target accuracy and computational resources:

- Pople-style basis sets (e.g., 6-31G, 6-311+G*): Provide good cost-to-performance ratio for initial calculations.

- Dunning's correlation-consistent basis sets (e.g., cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ, cc-pVQZ): Designed for systematic convergence to the complete basis set limit with post-HF methods.

- Diffuse functions: Essential for describing anions, weak interactions, and property calculations [19].

Hartree-Fock Calculation: A well-converged HF calculation provides the reference wavefunction and molecular orbitals for subsequent correlation treatments.

Electron Correlation Treatment: The selected post-HF method (CI, MP, or CC) is applied to the HF reference, with careful attention to:

- Reference stability: Checking for Hartree-Fock instability that might indicate the need for multi-reference methods.

- * Convergence thresholds*: Setting appropriate criteria for energy and wavefunction convergence.

- Integral storage: Managing disk/memory requirements for two-electron integrals [16].

Property Evaluation: Once the correlated wavefunction is obtained, molecular properties (geometries, frequencies, energies, etc.) can be calculated.

Basis Set Extrapolation: For highest accuracy, complete basis set (CBS) limits can be estimated using calculations with increasingly larger basis sets.

Table 3: Key Software Packages for Post-HF Calculations

| Software Package | Supported Methods | Special Features | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | HF, MP2, MP4, CISD, CCSD, QCISD | User-friendly interface, extensive method range | General purpose quantum chemistry |

| ORCA | MP2, CCSD(T), DLPNO-CCSD(T) | Efficient approximations for large systems | Large system correlation energy |

| PySCF | HF, MP2, CCSD, CASSCF | Python-based, customizable | Method development, education |

| NWChem | MP2, CCSD(T), CCSDT | Parallel implementation, periodic boundary conditions | Materials science, spectroscopy |

| MOLPRO | MP2, CCSD(T), MRCI | High-accuracy multi-reference methods | Spectroscopic accuracy, diatomic molecules |

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Materials Research

The high accuracy of post-HF methods finds critical applications in pharmaceutical research and materials science, particularly in scenarios where quantitative predictions of molecular interactions are essential.

In drug discovery, post-HF methods provide benchmark-quality data for:

- Non-covalent interactions: MP2 and CCSD(T) provide superior description of dispersion forces, π-π stacking, and hydrogen bonding, which are crucial for protein-ligand binding [20].

- Reaction barrier heights: Accurate prediction of activation energies for enzymatic reactions and drug metabolism pathways.

- Spectroscopic properties: Prediction of NMR chemical shifts and vibrational frequencies with quantitative accuracy.

- Covalent inhibitor design: Understanding the electronic structure of warhead groups and their reactivity with biological nucleophiles [20].

For metalloenzyme systems like cytochrome P450s, which play crucial roles in drug metabolism, the complex electronic structure of the heme iron center presents challenges for DFT. Recent research indicates that active spaces of approximately 50 orbitals are needed for accurate description of these systems, creating a crossover point where quantum computing and classical post-HF methods may soon provide advantages over traditional approaches [20].

In materials science, periodic implementations of MP2 and CC theories enable the study of:

- Surface adsorption processes

- Defect energies in semiconductors

- Electronic band structures

- Phonon dispersion relations

The development of periodic coupled-cluster theory with atom-centered, localized basis functions represents a significant advancement in applying these high-accuracy methods to extended systems [18].

Method Selection Guide and Future Perspectives

Decision Framework for Method Selection

Selecting the appropriate electronic structure method requires balancing computational cost, required accuracy, and system characteristics:

- For qualitative trends and initial screening: HF or inexpensive DFT functionals often suffice.

- For non-covalent interactions in medium systems: MP2 with triple-zeta basis sets provides good accuracy.

- For quantitative thermochemistry: CCSD(T)/CBS represents the gold standard when computationally feasible.

- For strongly correlated systems: Multi-reference methods (CASSCF, MRCI) are necessary despite their high cost.

- For large systems (>100 atoms): DFT with appropriate dispersion corrections or localized MP2/CC implementations are practical choices.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting among electronic structure methods:

Emerging Trends and Future Developments

The field of electronic structure theory continues to evolve, with several promising directions enhancing the applicability of post-HF methods:

- Local correlation techniques: Methods like DLPNO-CCSD(T) achieve near-CCSD(T) accuracy with reduced computational scaling, extending these methods to larger systems.

- Embedding schemes: Combining high-level post-HF methods for a chemically active region with lower-level methods for the environment enables accurate treatment of large systems.

- Periodic post-HF methods: Development of MP2 and CC theory for periodic systems brings high-accuracy quantum chemistry to materials science [18].

- Quantum computing algorithms: Quantum phase estimation and variational quantum eigensolvers promise to extend exact diagonalization beyond the limits of classical computers, particularly for strongly correlated systems [20].

- Machine learning acceleration: Neural network potentials trained on post-HF reference data enable molecular dynamics simulations with correlated quantum chemistry accuracy.

As these advancements mature, the accessible application domain of post-HF methods will continue to expand, potentially transforming their role from specialized benchmark tools to routine methods for challenging chemical problems in pharmaceutical research and materials design.

In conclusion, the post-HF hierarchy of CI, MP, and CC theories provides a systematically improvable pathway to accurate solutions of the electronic Schrödinger equation. While computational cost remains a limiting factor, their precision and reliability establish them as essential methods for benchmarking, understanding complex electronic phenomena, and providing reference data for parameterizing more approximate methods. The ongoing development of more efficient algorithms and implementations ensures that these methods will continue to play a crucial role at the forefront of computational chemistry and molecular design.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as one of the most widely used computational methods in quantum chemistry and materials science, prized for its favorable balance between computational cost and accuracy. However, its reliability is fundamentally constrained by the approximation of the exchange-correlation functional, which encapsulates complex electron-electron interactions. In principle, DFT is an exact theory; the failures commonly attributed to it are more accurately described as failures of specific Density Functional Approximations (DFAs) [22]. The development of increasingly sophisticated functionals represents attempts to better approximate this unknown, exact functional, with each new generation aiming to expand the theory's applicability while maintaining computational tractability.

This guide provides an objective comparison of DFT performance against post-Hartree-Fock methods across diverse chemical systems, presenting quantitative benchmarking data to inform method selection for research applications, particularly in drug development where accurate prediction of molecular properties is crucial.

Theoretical Framework: Exchange-Correlation Functionals in Context

In the Kohn-Sham DFT approach, the total electronic energy is expressed as:

[ E\textrm{electronic} = T\textrm{non-int.} + E\textrm{estat} + E\textrm{xc} ]

where (T\textrm{non-int.}) represents the kinetic energy of a fictitious non-interacting system, (E\textrm{estat}) accounts for electrostatic interactions, and (E_\textrm{xc}) is the exchange-correlation energy [23]. This last term must capture everything not included in the first two terms—primarily exchange energy (related to the Pauli exclusion principle) and correlation energy (arising from electron-electron repulsions).

The hierarchy of functionals, often called "Jacob's Ladder," ascends from basic local approximations to increasingly complex forms:

- Local Density Approximation (LDA): Depends only on the local electron density (\rho(\mathbf{r})).

- Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA): Incorporates both (\rho(\mathbf{r})) and its gradient (|\nabla\rho(\mathbf{r})|).

- meta-GGA: Adds further dependence on the kinetic energy density or other local information.

- Hybrid Functionals: Mix in a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange.

- Double Hybrids: Include both Hartree-Fock exchange and a perturbative correlation contribution.

Unlike wavefunction-based methods that are systematically improvable (e.g., CCSD(T) is typically more accurate than MP2), DFAs lack this systematic improvability [22]. A functional higher on the ladder may not yield more accurate results for all properties, making benchmarking against reliable reference data essential.

Figure 1: The functional hierarchy in electronic structure theory. While complexity generally increases upward, performance does not always systematically improve across all chemical systems.

Comparative Performance Assessment: Quantitative Benchmarks

Performance on Transition Metal Complexes and Porphyrins

Transition metal systems present particular challenges due to complex electronic structures with nearly degenerate states and strong correlation effects. A comprehensive benchmark of 250 electronic structure methods (including 240 DFAs) on iron, manganese, and cobalt porphyrins revealed significant functional-dependent performance [24].

Table 1: Performance of Select Functionals on Por21 Benchmark Database (spin states and binding energies of metalloporphyrins)

| Functional | Type | Grade | Mean Unsigned Error (kcal/mol) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAM | GGA | A | <15.0 | Best overall performer |

| revM06-L | meta-GGA | A | <15.0 | Recommended for transition metals |

| r2SCAN | meta-GGA | A | <15.0 | Improved SCAN revision |

| HCTH | GGA | A | <15.0 | Multiple parameterizations |

| B3LYP | Hybrid | C | ~23.0 | Most widely used functional |

| B2PLYP | Double Hybrid | F | >>23.0 | Catastrophic failure |

| M06-2X | Hybrid | F | >>23.0 | High exact exchange failure |

The best-performing functionals achieved mean unsigned errors (MUEs) below 15.0 kcal/mol, but this remains far from the "chemical accuracy" target of 1.0 kcal/mol [24]. Local functionals (GGAs and meta-GGAs) generally outperformed hybrid functionals for these systems, with global hybrids containing low percentages of exact exchange being least problematic. Functionals with high percentages of exact exchange, including range-separated and double-hybrid functionals, often showed catastrophic failures for transition metal spin states [24].

Aurophilic Interactions and Dispersion Challenges

Closed-shell metallophilic interactions (such as aurophilic Au(I)···Au(I) attractions) present another challenging case study, with interaction energies similar to hydrogen bonds (20–50 kJ molâ»Â¹) [5].

Table 2: Method Performance for Aurophilic Interactions in [ClAuPH₃]₂ Model System

| Method | Type | Au-Au Distance (Ã…) | Interaction Energy | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T) | Post-HF | ~3.20 | Accurate | Considered most reliable |

| SCS-MP2 | Post-HF | ~3.20 | Accurate | Comparable to CCSD(T) |

| MP2 | Post-HF | ~3.10 | Overestimated | Known to overbind |

| PBE-D3 | DFT-D | ~3.25 | Reasonable | With dispersion correction |

| Traditional DFT | DFT | Variable | Unreliable | Severe dispersion description issues |

Post-Hartree-Fock methods (particularly SCS-MP2 and CCSD(T)) provide results in better agreement with experimental values compared to DFT-based methods [5]. Traditional functionals like B3LYP, PBE, and TPSS fail to reliably describe the predominantly dispersion-type interactions unless specifically augmented with dispersion corrections (e.g., Grimme's D3 correction) [5].

Organic Systems and Zwitterions

Unexpected performance patterns can emerge even for organic systems. In studies of pyridinium benzimidazolate zwitterions, Hartree-Fock method unexpectedly outperformed various DFT functionals for reproducing experimental dipole moments and structural parameters [7]. The localization issue inherent in HF proved advantageous over the delocalization problem common in DFAs for these specific zwitterionic systems. This performance was further validated by similar results from high-level methods including CCSD, CASSCF, CISD, and QCISD [7].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Benchmarking DFT for Metalloporphyrins

The Por21 benchmarking protocol [24] employed the following methodology:

- Reference Data: CASPT2 reference energies for spin state energy differences and binding energies of iron, manganese, and cobalt porphyrins from literature.

- Systems: 250 electronic structure methods (240 density functional approximations) implemented in various quantum chemistry packages.

- Assessment Metric: Mean unsigned error (MUE) relative to reference data, with grading based on percentile ranking (A: top 10%, B: next 20%, C: next 20%, D: next 10%, F: bottom 40%).

- Chemical Space: Focus on biologically relevant metalloporphyrins with challenging nearly degenerate spin states.

Assessing Aurophilic Interactions

The protocol for assessing metallophilic interactions [5] involved:

- Model Systems: [ClAuPH₃]₂ dimer (intermolecular), [S(AuPH₃)₂] A-frame complex (intramolecular), and [AuPH₃]₄²⺠tetrahedral cluster.

- Method Levels: Comparison across HF, MP2, SCS-MP2, CCSD(T), and various DFT functionals with/without dispersion corrections.

- Key Properties: Interaction energies and equilibrium distances, compared against experimental data where available.

- Relativistic Effects: Inclusion where necessary, as they contribute approximately 27% to intermolecular interaction energies in gold systems.

Active Learning for Improved Benchmarking

Recent advances address chemical bias in traditional benchmarking through active learning approaches [25]:

- Initial Dataset: BH9 benchmarking set for pericyclic reactions.

- Chemical Space Design: Combinatorial combination of reaction templates and substituents.

- Surrogate Model: Predicts standard deviation of activation energies across 20 DFT functionals.

- Active Learning: Identifies regions with large functional divergence for targeted data acquisition.

- Convergence: Achieved with fewer than 100 additional reactions, yielding more challenging and representative benchmarks.

Figure 2: Active learning workflow for improved DFT functional benchmarking. This approach systematically identifies chemically challenging regions to create more representative benchmark sets.

Emerging Directions and Functional Development

Machine-Learned Functionals

Machine learning techniques are being employed to develop next-generation functionals [23]. The MCML (multi-purpose, constrained, and machine-learned) functional focuses on training the semi-local exchange part in a meta-GGA while keeping correlation in GGA form. For dispersion-dominated interactions, the VCML-rVV10 functional simultaneously optimizes semi-local exchange and a non-local van der Waals part, showing improved performance for systems like graphene adsorption on Ni(111) [23].

A significant challenge is creating functionals that perform well for both molecules and extended solids. While Google DeepMind's DM21 functional was trained on molecular quantum chemistry data, it performed poorly for solid-state band structures until modified to include the homogeneous electron gas as a physical constraint (DM21mu) [23].

New Correlation Functional Formulations

Recent work introduces new correlation functionals incorporating ionization energy dependence [26]. By employing the density's dependence on ionization energy, the new functional aims to improve accuracy for total energy, bond energy, dipole moment, and zero-point energy calculations. When tested on 62 molecules, this approach demonstrated minimal mean absolute error compared to established functionals like QMC, PBE, B3LYP, and Chachiyo [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for DFT and Post-HF Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Software Package | Perform electronic structure calculations | Gaussian, Turbomole [5] |

| Benchmark Databases | Reference Data | Validate method performance | Por21 (metalloporphyrins) [24], BH9 (pericyclic reactions) [25] |

| Dispersion Corrections | Add-on Correction | Improve van der Waals interaction description | Grimme's D3, D4 [5] |

| Plane-Wave Codes | Software Package | Periodic boundary condition calculations | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO |

| Wavefunction Analysis Tools | Analysis Utility | Interpret electronic structure results | Multiwfn, Bader Analysis |

| 1-Chloro-2-(1-methylethoxy)benzene | 1-Chloro-2-(1-methylethoxy)benzene, CAS:42489-57-6, MF:C9H11ClO, MW:170.63 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 6-Acetylpyrimidine-2,4(1h,3h)-dione | 6-Acetylpyrimidine-2,4(1h,3h)-dione, CAS:6341-93-1, MF:C6H6N2O3, MW:154.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The exchange-correlation functional remains the core challenge in Density Functional Theory, with performance highly dependent on the chemical system and properties of interest. For transition metal complexes like porphyrins, local meta-GGA functionals (revM06-L, r2SCAN) currently offer the best compromise between accuracy and reliability [24]. For non-covalent interactions including metallophilic attractions, dispersion-corrected functionals or specialized post-HF methods (SCS-MP2) are necessary [5].

While DFT continues to dominate applications for medium to large systems due to its favorable computational scaling, the lack of systematic improvability necessitates careful method selection and validation against reliable benchmark data. Emerging approaches incorporating machine learning and active learning promise more robust benchmarking and functional development [23] [25], potentially expanding the reach of DFT while providing better uncertainty quantification for predictive materials design and drug development applications.

In computational chemistry, the ability to predict reaction energies and binding affinities is fundamental to advancing fields like drug discovery and materials science. The benchmark for this predictive power is "chemical accuracy," a term synonymous with an error margin of 1 kilocalorie per mole (kcal/mol). This standard is not arbitrary; it stems from the practical requirements of experimental science and the theoretical limits of the most trusted computational methods. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance of various computational approaches, with a specific focus on how Density Functional Theory (DFT) and post-Hartree-Fock methods measure up to this critical threshold.

Section 1: The Significance of 1 kcal/mol in Chemistry and Drug Design

In practical terms, 1 kcal/mol represents a level of precision that allows computational results to be directly relevant to experimental outcomes.

- Biological Binding Affinity: A key part of drug design and development is the optimization of molecular interactions between an engineered drug candidate and its binding target. A binding affinity difference of 1.4 kcal/mol corresponds to an order of magnitude (10-fold) change in binding constant [27]. Achieving chemical accuracy is therefore essential for meaningful predictions in lead optimization.

- Experimental Reproducibility: The 1 kcal/mol benchmark also aligns with the practical limits of experimental reproducibility. Observations indicate that the root-mean-squared error (RMSE) associated with experimental reproducibility is approximately 1 kcal/mol, which sets a natural limit for the achievable accuracy for any affinity prediction method [28]. Computational methods aiming to surpass this experimental uncertainty must first achieve chemical accuracy.

Section 2: Methodological Comparison: Pathways to Chemical Accuracy

Different computational strategies are employed to reach chemical accuracy, each with its own trade-offs between computational cost, system size, and reliability. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Methods for Achieving Chemical Accuracy

| Method Category | Representative Methods | Typical Target Accuracy (kcal/mol) | Relative Computational Cost | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold-Standard | CCSD(T)/CBS [29] | ~0.3 (for well-behaved systems) | Extremely High | Small-system benchmarks & training data |

| Composite Methods | Gaussian-n (G2, G3, G4) [30] | ~1.0 (by design) | High | Thermochemical properties of organic molecules |

| Robust DFT Protocols | B97M-V, r2SCAN-3c, double-hybrid functionals [31] | 1-2 (with careful validation) | Medium | Larger systems (50-100 atoms), reaction mechanisms |

| Classical Force Fields | OPLS_2005 [29] | Often >2 (varies widely) | Low | Very large systems (proteins, viruses) |

| Machine Learning Force Fields | FeNNix-Bio1, SNS-MP2 [32] [29] | ~1 (as demonstrated on benchmarks) | Low (after training) | Drug discovery, biomolecular simulation at scale |

The following workflow illustrates how a researcher might navigate the choice of method based on their system and accuracy requirements:

Diagram 1: A decision workflow for selecting computational methods based on system size and accuracy needs.

Section 3: Experimental Protocols for Method Benchmarking

To objectively compare the accuracy of different computational methods, standardized benchmarking against reliable datasets is crucial. The following protocol outlines this process.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Against Gold-Standard Dimer Interaction Energies

This protocol uses the DES370K and related databases [29], which provide over 370,000 dimer interaction energies computed at the CCSD(T)/CBS level, a recognized gold-standard [29].

- Data Set Selection: Select a representative subset of dimer complexes from a benchmark database like DES370K or its core subset DES15K. These dimers should cover diverse interaction types (e.g., hydrogen bonding, van der Waals, π-π stacking).

- Structure Preparation: Extract the Cartesian coordinates for the dimer geometries. For the method being tested (e.g., a DFT functional), perform a geometry optimization if assessing energy at optimized geometries, or use the provided CCSD(T)-optimized structures directly for single-point energy calculations.

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: Calculate the interaction energy for each dimer using the method under investigation. The interaction energy (ΔE) is typically computed as: ΔE = Edimer - (Emolecule_A + Emolecule_B). Basis set superposition error (BSSE) should be corrected for, using a method such as the counterpoise correction.

- Statistical Analysis: Compare the calculated interaction energies against the CCSD(T)/CBS benchmark values. Key metrics include:

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE): The average of the absolute differences between calculated and benchmark values.

- Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE): Gives a greater weight to larger errors.

- Percentage within 1 kcal/mol: The fraction of predictions that meet the chemical accuracy standard.

Table 2 provides a hypothetical comparison of different methods benchmarked against such a dataset.

Table 2: Hypothetical Benchmarking Results for Interaction Energies (based on DES370K-type data)

| Computational Method | Mean Absolute Error (MAE, kcal/mol) | Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE, kcal/mol) | Calculations within 1 kcal/mol of Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T)/CBS (Benchmark) | 0.00 (by definition) | 0.00 (by definition) | 100% |

| SNS-MP2 (ML-enhanced) | ~0.3 [29] | ~0.4 [29] | >95% |

| G4 Composite Method | ~0.9 [30] | ~1.2 | ~85% |

| B3LYP-D3/def2-TZVP | ~1.5 | ~2.0 | ~65% |

| B3LYP/6-31G* | >2.0 [31] | >3.0 | <40% |

Section 4: Performance Analysis in Drug Discovery Applications

The true test of chemical accuracy is its impact on real-world applications like drug discovery.

Case Study: Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) Calculations

RBFE calculations are a powerful tool in drug discovery for predicting how small chemical changes affect a molecule's binding affinity to a target. The gold standard for these calculations is an accuracy that matches experimental results within 1 kcal/mol [28].

- Protocol: The accuracy of RBFE calculations is highly sensitive to the initial structure modeling. A robust protocol involves using high-resolution crystal structures (< 2.0 Ã…), carefully assigning protonation states of residues and ligands, and explicitly modeling key water molecules in the binding pocket. Tools like SOLVATE can accurately predict crystallographic water locations, which enhances RBFE accuracy [28].

- Performance Data: Studies on "activity cliff" pairs (structurally similar ligands with large potency differences) show that modern RBFE protocols can achieve average unsigned errors (AUE) close to 1.4 kcal/mol. Outliers are often attributed to differences in water placement and amino acid conformations, underscoring the importance of structure quality [28]. AI-predicted structures from AlphaFold2/3 show potential for RBFE when experimental structures are unavailable [28].

Case Study: AI/ML Force Fields in Biomolecular Simulation

Emerging AI models are challenging the traditional speed-versus-accuracy trade-off.

- Protocol: Models like FeNNix-Bio1 are trained on large datasets of quantum chemical calculations, learning to predict energy and forces on atoms without manual parameter tuning [32]. They can then be used in molecular dynamics simulations of proteins, protein-ligand binding, and even chemical reactions.

- Performance Data: In rigorous tests, FeNNix-Bio1 has demonstrated quantum-level accuracy at speeds comparable to classical force fields [32].

- Hydration Free Energy: Predicted value of –6.49 kcal/mol for water, nearly matching the experimental –6.32 kcal/mol [32].

- Protein-Ligand Binding: Calculated an absolute binding free energy of –5.5 kcal/mol, within 0.1 kcal/mol of the experimental value of –5.44 kcal/mol [32].

- Speed: Achieved 10× to 100× faster performance than some state-of-the-art models under the same conditions, enabling simulation of systems with millions of atoms [32].

Table 3: Key Software and Databases for High-Accuracy Computational Chemistry

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Chemical Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| DES370K / DES15K [29] | Benchmark Database | Provides gold-standard CCSD(T)/CBS interaction energies for thousands of dimers. | Essential for validating and parameterizing new DFT functionals, force fields, and ML models. |

| Gaussian, MOLPRO | Quantum Chemistry Software | Suites for running ab initio, DFT, and composite method calculations. | Implements methods like G4, CCSD(T), and others needed for high-accuracy thermochemistry. |

| FeNNix-Bio1 [32] | AI/ML Force Field | A foundation model for molecular simulation that learns from quantum data. | Aims to provide quantum accuracy at speeds sufficient for drug discovery on large biomolecules. |

| SOLVATE [28] | Solvation Tool | Predicts the location of crystallographic water molecules. | Critical for improving the accuracy of RBFE calculations in drug design by modeling solvation. |

| GMTKN55 [31] | Benchmark Database | A diverse set of 55 benchmark sets for general main-group thermochemistry and kinetics. | Used for the comprehensive testing and development of new DFT methods and basis sets. |

The pursuit of chemical accuracy, defined as 1 kcal/mol, remains a central driving force in computational chemistry. As the comparisons show, no single method universally dominates. Gold-standard post-Hartree-Fock methods like CCSD(T) provide the benchmark but are computationally prohibitive for most drug-sized systems. Well-validated DFT protocols offer a practical balance for many applications, though their performance must be critically assessed. The most transformative development is the rise of AI/ML-based force fields like FeNNix-Bio1, which promise to break the traditional cost-accuracy trade-off, offering a path to achieve quantum accuracy at the scale required for real-world drug discovery. The choice of method ultimately depends on the specific problem, but the 1 kcal/mol standard provides the common goal against which all are measured.

Advanced Computational Methodologies: From Traditional Post-HF to Machine Learning Hybrids

In the rigorous assessment of quantum chemical methods, a hierarchy of accuracy exists, with the coupled-cluster singles, doubles, and perturbative triples (CCSD(T)) method positioned at the apex for single-reference systems [33]. Widely regarded as the "gold standard" of quantum chemistry, its exceptional accuracy is indispensable for generating benchmark-quality data to evaluate the performance of more approximate methods, including various Density Functional Theory (DFT) functionals and other post-Hartree-Fock approaches [34] [33]. The foundational role of CCSD(T) is particularly critical in the context of drug discovery, where the accurate prediction of molecular properties and interaction energies can significantly streamline the development pipeline [35] [36].

However, the unadulterated CCSD(T) method comes with a prohibitive computational cost, scaling as the seventh power of the system size (O(Nâ·)) [34]. This severe scaling limits its practical application to molecules comprising only tens of atoms. To bridge this gap between accuracy and feasibility, local correlation approximations such as Domain-Based Local Pair Natural Orbital (DLPNO) and Pair Natural Orbital (PNO) methods have been developed [34]. These approximations ingeniously leverage the physical nature of electron correlation, which decays rapidly with distance, to dramatically reduce computational overhead while striving to retain the coveted accuracy of their parent method. This guide provides a objective comparison of these methods, detailing their performance, underlying protocols, and practical utility for researchers.

The Benchmark: CCSD(T)

CCSD(T) (Coupled-Cluster Singles, Doubles with perturbative Triples) starts from a Hartree-Fock reference wavefunction and systematically accounts for electron correlation through an exponential wave operator that generates all possible excitations (singles, doubles, triples, etc.) from the reference [33]. The connected triple excitations are included via a perturbative correction, which makes the method more affordable than a full inclusion of triples, while capturing the majority of the correlation energy [33]. Its principal strength lies in providing near-exact solutions for the electronic energy of systems where a single Slater determinant is a good starting point. Its most significant drawback is its steep computational scaling (O(Nâ·)), which confines its application to small or medium-sized molecules [34] [33].

The Efficient Approximation: DLPNO-CCSD(T)

The DLPNO-CCSD(T) (Domain-Based Local Pair Natural Orbital Coupled Cluster Singles, Doubles and perturbative Triples) method is designed to replicate CCSD(T) accuracy at a fraction of the cost, making it applicable to large systems, including those with hundreds of atoms [34]. Its operation is based on a three-step process:

- Domain Construction: The molecular system is divided into local domains, operating on the principle that electron correlation is a short-range phenomenon.

- Pair Natural Orbitals (PNOs): For each pair of electrons, a compact set of localized virtual orbitals (PNOs) is constructed, which are tailored to describe the correlation of that specific pair efficiently.

- Truncation via Thresholds: The accuracy and cost are controlled by "PNO thresholds" (e.g.,

TightPNO,NormalPNO). Tighter thresholds yield higher accuracy but increase computational cost [34].

The key advantage of DLPNO-CCSD(T) is its much lower computational scaling, effectively reducing it to near linear scaling for large systems. The primary compromise is the introduction of a small, controllable error due to the local approximations.

Table 1: Core Methodological Comparison of CCSD(T) and DLPNO-CCSD(T)

| Feature | CCSD(T) | DLPNO-CCSD(T) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Foundation | Coupled-Cluster with perturbative Triples | Local approximation to CCSD(T) |

| Key Approximation | None (canonical) | Local domains and Pair Natural Orbitals (PNOs) |

| Computational Scaling | O(Nâ·) [34] | Near-linear for large systems [34] |

| System Size | Small to medium molecules | Medium to very large molecules (e.g., proteins, nanomaterials) |

| Accuracy | Gold standard, benchmark quality | Near CCSD(T) accuracy with controlled error |

| Primary Control | Basis set | PNO thresholds (e.g., TightPNO, NormalPNO) and basis set |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

The true test of any approximate method is its performance against the gold standard across a diverse set of chemical properties. Quantitative benchmarking against CCSD(T) is essential for establishing the reliability of DLPNO approximations.

Quantitative Accuracy Assessment

Studies systematically comparing DLPNO-CCSD(T) to canonical CCSD(T) reveal its remarkable performance. In one investigation focused on hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) reactions—a challenging test case due to the critical role of electron correlation—the DLPNO method demonstrated excellent agreement with CCSD(T) [34].

Table 2: Performance of DLPNO-CCSD(T) vs. CCSD(T) for HAT Reaction Energetics Data sourced from a comparative study of reaction energies and barrier heights using aug-cc-pVnZ (n=D,T,Q) basis sets [34].

| System Type | Chemical Example | Mean Absolute Error (TightPNO) | Maximum Deviation (TightPNO) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-Shell Unimolecular | Decomposition of carbonic acid | < 0.1 kcal/mol | ~0.2 kcal/mol |

| Closed-Shell Bimolecular | Hydrolysis of sulfur trioxide | < 0.1 kcal/mol | ~0.1 kcal/mol |

| Open-Shell Bimolecular | OH + HCl reaction | ~0.2 kcal/mol | ~0.3 kcal/mol |

| Overall Performance | Multiple HAT reactions | Standard Deviation: 0.15 kcal/mol | -- |

The data in Table 2 shows that with TightPNO settings, DLPNO-CCSD(T) can achieve chemical accuracy (typically defined as ~1 kcal/mol error) for both reaction energies and barrier heights, with deviations from CCSD(T) often falling below 0.3 kcal/mol [34]. This makes it highly suitable for calculating reliable thermodynamic and kinetic parameters.

Comparative Performance Against Other Methods

To place the performance of CCSD(T) and its approximations in context, it is valuable to see how they compare to other common quantum chemical approaches for a specific property. The following table summarizes a comparison for calculating dipole moments, a critical property influencing molecular interactions in drug discovery.

Table 3: Method Performance Comparison for Dipole Moment Calculation of a Zwitterionic Molecule Adapted from a study comparing computed dipole moments against an experimental value of 10.33 Debye [7].

| Computational Method | Category | Calculated Dipole Moment (Debye) | Deviation from Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment [7] | -- | 10.33 | -- |

| HF [7] | Post-HF (Reference) | ~10.3 | ~0.03 |

| CCSD [7] | High-Level Post-HF | Very close to HF | Very small |

| B3LYP [7] | DFT (Hybrid GGA) | ~13 | ~2.7 |

| M06-2X [7] | DFT (Meta-GGA) | ~12 | ~1.7 |

| ωB97xD [7] | DFT (Long-range corrected) | ~11.5 | ~1.2 |

This comparison highlights a key point: while CCSD(T) itself is the gold standard for energy, even the simpler HF method can sometimes outperform certain DFT functionals for specific molecular properties, particularly those sensitive to electron delocalization [7]. High-level post-HF methods like CCSD often validate the HF result in these cases, reinforcing the need for careful method selection based on the property of interest.

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

To ensure the reliability of computational data, especially when using approximate methods like DLPNO-CCSD(T), adherence to rigorous validation protocols is paramount. Below is a detailed methodology for benchmarking and applying these methods.

Benchmarking DLPNO Against CCSD(T)

Objective: To quantify the accuracy of the DLPNO-CCSD(T) method for a specific class of chemical reactions or molecular systems. Reference Method: Canonical CCSD(T) at the complete basis set (CBS) limit is the preferred benchmark [34]. Procedure:

- System Selection: Choose a diverse set of small to medium-sized molecules and reaction pathways relevant to your research (e.g., HAT reactions, non-covalent interactions, bond dissociation) [34].

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the molecular geometries (reactants, products, transition states) using a reliable but cost-effective method, such as DFT with a medium-sized basis set.

- Reference Energy Calculation: Perform single-point energy calculations at the optimized geometries using the canonical CCSD(T) method with a high-quality basis set (e.g., aug-cc-pVTZ or aug-cc-pVQZ). Extrapolation to the CBS limit is ideal [34].

- DLPNO Energy Calculation: On the same set of geometries, perform DLPNO-CCSD(T) single-point calculations using a range of PNO cutoff thresholds (e.g.,

NormalPNO,TightPNO) and the same basis set as in step 3. - Data Analysis: For each species and reaction energy/barrier, calculate the difference (error) between the DLPNO-CCSD(T) result and the canonical CCSD(T) benchmark. Statistical analysis (Mean Absolute Error, Standard Deviation) should be performed across the test set [34].

Practical Application Protocol for Large Systems

Objective: To apply the validated DLPNO-CCSD(T) method for high-accuracy energy calculations on large molecular systems where canonical CCSD(T) is not feasible. Procedure:

- Method Selection: Based on the benchmarking results from Protocol 4.1, select the appropriate PNO setting (

TightPNOis recommended for publication-quality results unless system size demands otherwise) [34]. - Geometry Preparation: Obtain the geometry of the large system through classical molecular mechanics, molecular dynamics, or DFT optimization.

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: Execute a DLPNO-CCSD(T) single-point energy calculation on the prepared geometry using the selected settings and the largest feasible basis set (often a double or triple-zeta basis like def2-TZVP).

- Result Interpretation: Report the final energy and any derived properties (e.g., binding energies, reaction energies). It is good practice to report the PNO settings used and, if available, the estimated error based on prior benchmarking.

The logical workflow for selecting and validating these electronic structure methods is summarized in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

To effectively implement the methodologies discussed, researchers require access to specific software tools and computational resources. The following table details key "research reagents" in the computational chemist's toolkit.

Table 4: Essential Software and Resources for High-Accuracy Quantum Chemistry

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to CCSD(T)/DLPNO |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORCA [34] | Quantum Chemistry Software | A specialized program for post-HF methods. | The primary platform for running DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculations, featuring highly optimized implementations [34]. |