Error Mitigation Techniques for ADAPT-VQE: A 2025 Guide for Quantum Chemistry and Drug Discovery

Accurately simulating molecular systems on noisy quantum hardware is a critical challenge for fields like drug discovery.

Error Mitigation Techniques for ADAPT-VQE: A 2025 Guide for Quantum Chemistry and Drug Discovery

Abstract

Accurately simulating molecular systems on noisy quantum hardware is a critical challenge for fields like drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced error mitigation techniques specifically for the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE). We explore the foundational noise sources that plague near-term devices, detail practical methodological advances from readout correction to algorithm-specific optimizations, and present troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls. Finally, we validate these techniques through comparative analyses of real hardware demonstrations and simulations, offering a clear roadmap for researchers and scientists in biomedical fields to harness quantum computing for molecular energy estimation.

Understanding the Noise Challenge: Why ADAPT-VQE is Vulnerable on NISQ Hardware

Core Challenges & Quantitative Benchmarks

Understanding the specific thresholds for hardware error is crucial for planning feasible ADAPT-VQE experiments. The table below summarizes key performance-limiting factors and their quantitative impacts, as established by recent research.

| Challenge | Key Finding / Impact | System Studied | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depolarizing Gate Errors | Tolerable error probability (p_c) for chemical accuracy is between 10â»â¶ and 10â»â´ (10â»â´ to 10â»Â² with error mitigation). | Small molecules (4-14 orbitals) | [1] |

| Scaling with System Size | Maximally allowed gate-error probability p_c decreases with the number of noisy two-qubit gates NII as pc ∠~1/N_II. |

Various molecules | [1] |

| Algorithm Comparison | ADAPT-VQEs consistently tolerate higher gate-error probabilities than fixed-ansatz VQEs (e.g., UCCSD, k-UpCCGSD). | Various molecules | [1] |

| Ansatz Element Choice | ADAPT-VQEs perform better and are more noise-resilient when circuits are built from gate-efficient elements rather than physically-motivated ones. | Various molecules | [1] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My ADAPT-VQE algorithm is not converging, or the energy is far from the true ground state. What could be wrong?

This is a common symptom of hardware noise overwhelming the quantum computation. The primary cause is likely that the gate-error probability on your hardware exceeds the tolerable threshold for your target molecule. The required precision for "chemical accuracy" is 1.6 × 10â»Â³ Hartree. If your hardware's native gate errors are on the order of 10â»Â³ or higher, achieving this accuracy, even with a compact ADAPT-VQE ansatz, is challenging [1]. Furthermore, your problem might be too large; the tolerable error level becomes more stringent as the number of qubits and gates increases [1].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Benchmark Your Hardware: Characterize the fidelity of single- and two-qubit gates on your target device.

- Estimate Circuit Demands: Calculate the expected number of two-qubit gates (NII) your ADAPT-VQE circuit will require. Use the scaling relation ( pc \propto N_{II}^{-1} ) to estimate the maximum gate error your experiment can tolerate [1].

- Implement Error Mitigation: Integrate an error mitigation technique like Reference-state Error Mitigation (REM) or the more advanced Multireference-state Error Mitigation (MREM) to significantly improve your results [2].

Q2: I am getting zero gradients for many operators in my operator pool during the ADAPT-VQE process, which should not be happening. Why?

This issue can stem from a combination of algorithmic and hardware-related problems.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Noise-Induced Barren Plateaus: While ADAPT-VQE is designed to mitigate rough parameter landscapes, severe noise can still cause gradients to vanish, a phenomenon known as noise-induced barren plateaus [1]. This is consistent with the gate error issues described in the core challenges.

- Simulator/Hardware Inconsistencies: This problem has been reported by users running seemingly identical code, suggesting potential underlying instability in the classical optimizer or simulator-specific behavior [3].

- Actionable Steps:

- Verify in a Noiseless Setting: First, run your algorithm on a noiseless statevector simulator to ensure the code and ansatz are correct.

- Check Operator Pool: Ensure your chosen operator pool (e.g., UCCGSD) is appropriate for your molecule and has the necessary expressibility.

- Inspect Measurement: Review how the gradients

[H, A_m]are being measured to rule out implementation errors.

Q3: What are the most promising error mitigation techniques specifically for ADAPT-VQE in quantum chemistry?

Given the high sensitivity to noise, error mitigation is not optional but a core component of the algorithm. The following techniques show particular promise:

- Multireference-state Error Mitigation (MREM): This is an advanced extension of Reference-state Error Mitigation (REM). While REM uses a single, classically-solvable reference state (like Hartree-Fock) to calibrate hardware noise, its effectiveness drops for strongly correlated systems. MREM uses a linear combination of Slater determinants (a multireference state) engineered to have substantial overlap with the true ground state, leading to much more accurate error mitigation for molecules like Fâ‚‚ or Nâ‚‚ in bond-stretching regimes [2].

- Deep-Learned Error Mitigation (DL-EM): This technique uses artificial neural networks trained to predict ideal expectation values from noisy quantum outputs. The training is integrated into the VQE process, and the classical computational cost is reduced by using circuit knitting techniques to generate training data. This method has been shown to recover accuracy below 1% where unmitigated VQE fails completely [4].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Implementing Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM)

This protocol enhances the standard ADAPT-VQE workflow by adding a robust error mitigation step [2].

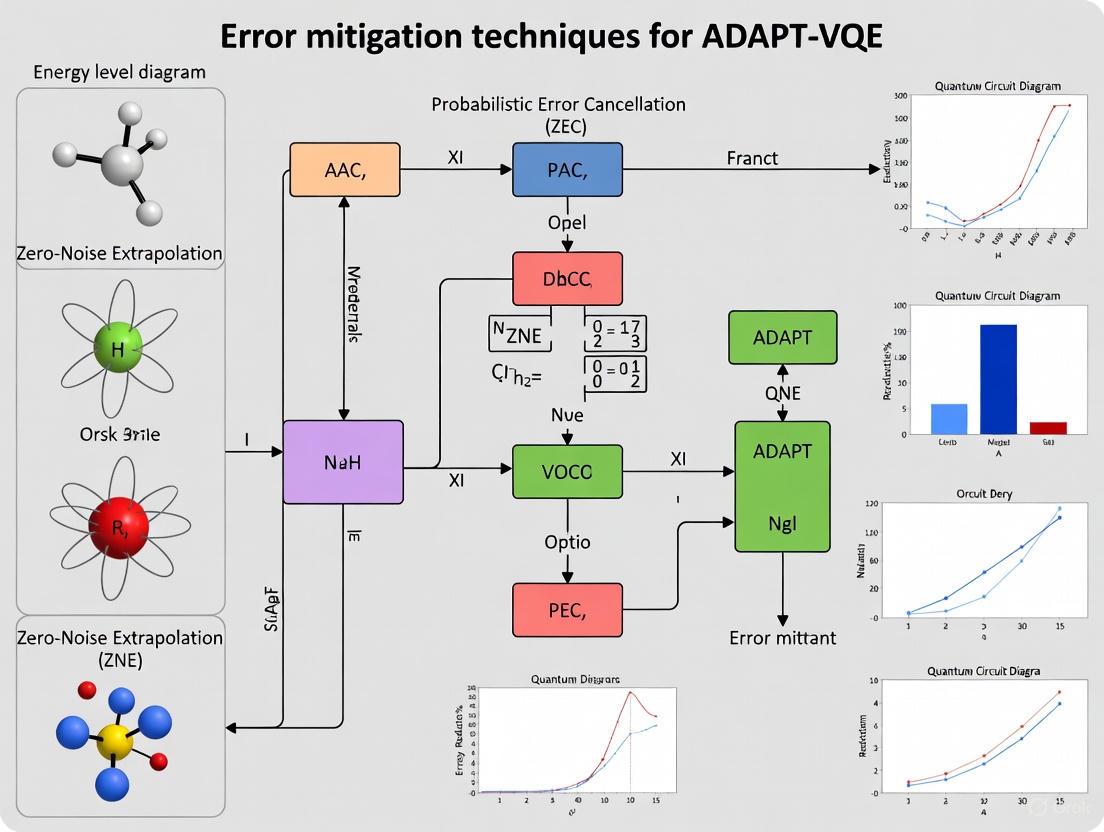

Workflow Diagram: ADAPT-VQE with MREM

Step-by-Step Guide:

- Run Standard ADAPT-VQE: Execute the ADAPT-VQE algorithm on your quantum hardware. This will produce a final, noisy parameterized ansatz state

|ψ(θ_noisy)>and its unmitigated energyE_noisy[5]. - Classically Generate MR State: Using an inexpensive classical method (e.g., selected CI, CASSCF), generate a compact multireference wavefunction composed of a few dominant Slater determinants that has good overlap with the true ground state.

- Prepare MR State on Quantum Hardware: Construct a quantum circuit to prepare the MR state from Step 2. A hardware-efficient method is to use Givens rotations, which can systematically build a linear combination of determinants from an initial reference state while preserving physical symmetries like particle number [2].

- Execute and Measure on QPU: Run the MR state preparation circuit on the same noisy quantum hardware. Measure its energy, yielding

E_MR_noisy. - Classical Computation: On a classical computer, calculate the exact, noiseless energy

E_MR_exactfor the same MR state. This is computationally cheap because the MR state is a truncated wavefunction. - Apply MREM Correction: Compute the mitigated energy for your ADAPT-VQE result using the formula:

E_mitigated = E_noisy - (E_MR_noisy - E_MR_exact)This subtracts the measured error on the known MR state from your target state's energy [2].

Protocol: Integrating Deep-Learned Error Mitigation (DL-EM)

This protocol uses machine learning to learn a mapping from noisy outputs to clean results [4].

Workflow Diagram: DL-EM Integrated VQE

Step-by-Step Guide:

- Smart Initialization: Begin with a parameter initialization strategy, such as using "patch circuits." These are simplified, classically simulable versions of the full ansatz where gates connecting different patches of qubits are removed [4].

- Generate Training Data: Use circuit knitting (specifically, partial knitting) to generate a dataset. This involves cutting the full circuit into smaller, classically simulable sub-circuits to compute ideal (noiseless) expectation values, while simultaneously running the full circuit on noisy hardware/simulators to get noisy expectation values [4].

- Train Neural Network: Train a multilayer perceptron (MLP) on the generated dataset. The inputs are hybrid: noisy quantum expectation values and classical descriptors of the quantum circuit (e.g., parameters, circuit structure). The target output is the ideal expectation value [4].

- Integrate into VQE Loop: Run the standard VQE optimization. However, at each function call for the energy expectation value, the noisy quantum outputs are passed through the trained DL-EM model to obtain a corrected, mitigated value.

- Re-training Check: Periodically, if the circuit parameters have deviated significantly from those used in the initial training, the DL-EM model should be re-trained on new data generated around the current parameter set to maintain accuracy [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key "research reagents" — software, algorithms, and methodological components — essential for conducting robust ADAPT-VQE research in the NISQ era.

| Research Reagent | Function / Explanation | Relevance to ADAPT-VQE |

|---|---|---|

Operator Pools (e.g., 'spin_complement_gsd') |

A predefined set of fermionic or qubit excitation operators from which the ADAPT-VQE algorithm selects the most energetically favorable one to grow the ansatz in each iteration [5]. | Defines the search space and expressive power of the adaptive ansatz. The choice of pool impacts convergence and circuit compactness. |

| Givens Rotations | Quantum circuits used to prepare multireference states, which are linear combinations of Slater determinants. They are universal for state preparation and preserve particle number and spin [2]. | Critical for implementing advanced error mitigation techniques like MREM, enabling the study of strongly correlated systems. |

| Circuit Knitting | A class of techniques that cut a large quantum circuit into smaller sub-circuits for classical simulation, then knit the results back together. "Partial knitting" strikes a balance between classical cost and accuracy [4]. | Drastically reduces the classical computational cost of generating training data for machine learning-based error mitigation like DL-EM. |

| Reference States (HF, MR) | Classically computable states (e.g., Hartree-Fock or a truncated multireference state) with high overlap to the true ground state. Their exact energy is known [2]. | Serves as the foundation for cost-effective error mitigation protocols (REM, MREM) by providing a calibrated benchmark for hardware noise. |

| Patch Circuits | A circuit ansatz where entangling gates connecting distinct "patches" of qubits are removed, making the circuit classically simulable [4]. | Used for smart parameter initialization, providing a good starting point for the full VQE optimization and reducing the number of expensive quantum evaluations. |

| Samioside | Samioside, MF:C34H44O19, MW:756.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Licoarylcoumarin | Licoarylcoumarin, CAS:125709-31-1, MF:C21H20O6, MW:368.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Item/Technique Function in Quantum Experiments Trapped-Ion Qubits ( [6] [7]) Serves as a highly stable physical qubit platform; known for long coherence times and high-fidelity gate operations. Microwave-Driven Gates ( [6] [7]) Provides a cheaper, more robust, and more scalable alternative to laser-based control for trapped ions, enabling higher fidelity. Randomized Benchmarking ( [6]) A rigorous technique used to characterize and extract the average error rate of quantum gates, filtering out State Preparation and Measurement (SPAM) errors. Gate Set Tomography (GST) ( [8]) Provides a complete, precise quantum description of all gates in a set, enabling detailed identification and optimization of error sources. Circuit Knitting ( [4]) A technique to cut a large quantum circuit into smaller, classically simulatable sub-circuits, reducing the cost of generating training data for error mitigation. Ultrapure Diamond ( [8]) A material host for spin qubits with a lower concentration of C-13 isotopes to minimize environmental magnetic noise. AV-412 free base AV-412 free base, CAS:451492-95-8, MF:C27H28ClFN6O, MW:507.0 g/mol Himalomycin B Himalomycin B, MF:C43H56O16, MW:828.9 g/mol

FAQs: Understanding Gate Errors and System Limitations

What is a quantum gate error rate, and how is it measured?

A quantum gate error rate (often quantified as infidelity or error probability) is a measure of the probability that a quantum logic operation will fail to produce the correct output state. It is a critical metric for assessing the quality of a quantum hardware component.

The most common method for measuring this is Randomized Benchmarking (RB) [6]. This technique involves applying long, random sequences of quantum gates (specifically Clifford gates) to a qubit and measuring the decay in the output state's fidelity as the sequence length increases. By fitting this decay curve, researchers can extract an average error per gate, effectively isolating the gate error from other error sources like state preparation and measurement (SPAM) [6]. For even more detailed characterization, Gate Set Tomography (GST) can be used to build a complete model of all gate operations, providing precise information on specific imperfections [8].

Why are my algorithm results inaccurate even with high single-qubit gate fidelities?

This is a common issue because the overall accuracy of a quantum algorithm is a chain of operations that is only as strong as its weakest link. Your high-fidelity single-qubit gates are likely being undermined by other, noisier processes in the system. The primary bottlenecks are typically:

- Two-Qubit Gate Errors: Entangling operations are inherently more complex and susceptible to noise. While single-qubit gate errors have reached the 10â»â· level (99.99999% fidelity), the best two-qubit gates currently have error rates on the order of 10â»Â³ to 10â»â´ (99.9% to 99.99% fidelity)—several orders of magnitude higher [6] [7]. In a deep algorithm, these errors accumulate rapidly.

- State Preparation and Measurement (SPAM) Errors: Initializing a qubit in a precise state and then reading it out accurately is challenging. SPAM errors are often around 10â»Â³ (0.1%), which can dominate the total error budget in experiments with very high gate fidelities [6].

- Decoherence: Even when gates are perfect, a qubit's quantum state can be lost over time due to interactions with its environment. This finite coherence time (Tâ‚‚) limits the total number of operations that can be performed within a computation [6].

What are the current state-of-the-art gate fidelities across different qubit platforms?

Performance varies significantly between different quantum computing hardware platforms. The table below summarizes recent benchmark achievements.

Table 1: State-of-the-Art Quantum Gate Error Rates (c. 2025)

Qubit Platform Single-Qubit Gate Error Two-Qubit Gate Error Key Achievements and Notes Trapped Ions (Oxford) ( 1.5 \times 10^{-7} ) [6] ~( 5 \times 10^{-4} ) (best demonstrations) [6] [7] World record for single-qubit accuracy; microwave control at room temperature [6] [7]. Diamond Spins (QuTech) As low as ( 1 \times 10^{-5} ) [8] Below ( 1 \times 10^{-3} ) (0.1%) [8] Full universal gate set with errors <0.1%; operation at elevated temperatures (up to 10K) [8]. Superconducting (Fluxonium) ~( 2 \times 10^{-5} ) [6] Information Missing Advanced superconducting qubit with improved coherence. Superconducting (Industry Leaders) ~( 1 \times 10^{-3} ) [6] Information Missing Typical performance in leading commercial processors. Neutral Atoms ~( 5 \times 10^{-3} ) [6] Information Missing Promising for scalability; single-site operations.

How do gate error rates relate to the feasibility of quantum error correction (QEC)?

Quantum gate error rates directly determine the practical overhead of building a fault-tolerant quantum computer.

QEC theory establishes an accuracy threshold: if the physical error rate of qubits and gates is below this threshold (typically estimated between 10â»Â² and 10â»Â³ for common codes like the surface code), then logical qubits with arbitrarily low error rates can be created by encoding information across many physical qubits [6] [4]. The lower the physical error rate is below this threshold, the more efficient the process becomes.

For example, achieving a logical error rate of 10â»Â¹âµ with a physical error rate of 10â»Â³ might require thousands of physical qubits per logical qubit. However, if the physical error rate is 10â»â·, the same logical error rate could be achieved with far fewer physical qubits and operations, drastically reducing the resource overhead and bringing practical quantum computation closer to reality [6].

Troubleshooting Guides: Error Mitigation and Characterization

My VQE energy estimation is noisy. How can I mitigate gate errors without full QEC?

For near-term algorithms like VQE on NISQ devices, full-scale QEC is not yet feasible. Instead, you can employ error mitigation (EM) techniques that reduce the impact of noise at the cost of increased circuit repetitions or classical post-processing. Below is a workflow for integrating a deep-learned error mitigation (DL-EM) strategy tailored for VQE [4].

Protocol: Deep-Learned Error Mitigation (DL-EM) for VQE [4]

- Objective: To train a classical neural network to learn the complex mapping between noisy quantum measurement outcomes and their ideal, noiseless counterparts, specifically within the VQE optimization loop.

- Materials/Methods:

- Quantum Hardware/Simulator: A quantum device or noisy simulator to execute parameterized circuits.

- Classical Computer: For running the neural network and optimizer.

- Neural Network Model: A multilayer perceptron (MLP).

- Input Features: The input to the network is a hybrid of noisy expectation values (from the quantum device) and classical descriptors of the quantum circuit (e.g., parameter values).

- Training Data Generation: The key challenge is generating accurate training data (noisy input / ideal output pairs). This is addressed using partial circuit knitting: the full circuit is "knitted" into smaller sub-circuits that are classically simulable, drastically reducing the computational cost of generating the ideal expectation values for training.

- Procedure:

- Smart Initialization: Begin VQE with a "patch circuit" ansatz, where gates connecting different patches of qubits are removed. This allows for efficient classical optimization to find a good starting point for the parameters [4].

- Initial Training: Generate the initial training set by applying partial knitting to a set of circuits relevant to the early stages of VQE. Train the DL-EM network on this data.

- VQE Loop with DL-EM: For each VQE iteration:

- Execute the parameterized circuit on the noisy quantum device.

- Feed the noisy results and circuit descriptors into the DL-EM network to obtain a mitigated expectation value for the energy.

- The classical optimizer (e.g., ADAM or COBYLA) uses this mitigated energy to update the circuit parameters [4].

- Adaptive Retraining: Monitor the circuit parameters during optimization. If they deviate significantly from the set used in the previous training phase, trigger a retraining of the DL-EM network using a new set of knitted circuits reflective of the current parameter region. This ensures the mitigation remains accurate throughout the optimization [4].

How can I accurately characterize the error profile of my gates?

Beyond a single error rate, understanding the detailed error profile of your gates is essential for targeted improvement. The protocol below outlines this process.

Table 2: Protocol for Comprehensive Gate Error Characterization

Step Procedure Purpose & Outcome 1. Error Budgeting Systematically identify and quantify all potential error sources (e.g., control amplitude noise, phase noise, decoherence, crosstalk). Creates a model to pinpoint the dominant contributions to the total error, guiding hardware improvements [6]. 2. Randomized Benchmarking (RB) Apply long sequences of random Clifford gates and measure fidelity decay. Use interleaved RB to isolate the error of a specific gate. Provides a robust, SPAM-resistant estimate of the average gate fidelity for single- and two-qubit gates [6]. 3. Gate Set Tomography (GST) Execute a comprehensive set of specially designed circuits that form a complete basis for characterizing the quantum process. Constructs a detailed model of the actual quantum process for each gate, identifying specific non-Markovian or coherent errors [8]. 4. Coherence Measurement Perform Tâ‚ (energy relaxation) and Tâ‚‚ (dephasing time) measurements on the qubits. Quantifies the fundamental limits imposed by the qubit's environment, separate from control-related errors [6]. 5. Model Validation Use the characterized error models from GST and RB to predict the outcome of a complex, multi-gate circuit (e.g., an artificial algorithm). Validates the accuracy and completeness of the characterization; a passed check indicates the gates are both precise and well-understood [8].

Frequently Asked Questions

| Question | Answer & Technical Guidance |

|---|---|

| Why does my ADAPT-VQE energy accuracy degrade significantly when studying larger molecules or using more qubits? | This is a classic scaling issue. As qubit count increases, the number of Pauli terms in the molecular Hamiltonian grows as O(N^4), requiring more measurements (shots) [9]. Deeper circuits for complex molecules also accumulate more gate errors. Combine error suppression (e.g., DRAG pulses) to reduce error rates at the hardware level with error mitigation (e.g., ZNE, REM) in post-processing [10] [11]. |

| How do I choose between error suppression, mitigation, and correction for my experiment? | Use them in combination for the best results. Error Suppression (e.g., dynamic decoupling) proactively reduces error rates on every circuit run. Error Mitigation (e.g., probabilistic error cancellation) uses post-processing to infer noiseless results from multiple noisy runs. Error Correction (QEC) uses many physical qubits to create one fault-tolerant logical qubit and is not yet viable for large-scale algorithms on current hardware [10] [11]. |

| My strongly correlated molecule (e.g., near bond dissociation) gives poor results with standard error mitigation. What can I do? | Standard Reference-State Error Mitigation (REM) uses a single Hartree-Fock reference, which fails when the true ground state is a multireference configuration. Implement Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM), which uses a linear combination of Slater determinants (e.g., prepared via Givens rotations on the quantum circuit) to capture strong correlation and provide a more effective reference for error mitigation [2]. |

| The measurement (readout) error is my primary bottleneck. How can I reduce it to achieve chemical precision? | For high-precision energy estimation, employ Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) to characterize and correct readout errors. Combine this with informationally complete (IC) measurements and locally biased random measurements to minimize the shot overhead required to achieve chemical precision, even with high initial readout errors [9]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Implementing Multireference Error Mitigation (MREM) for Strongly Correlated Systems

This protocol extends the standard REM method to handle molecules where a single reference state is insufficient.

- Objective: To mitigate errors in the energy calculation of a strongly correlated molecular ground state on a NISQ device.

- Background: Standard REM uses a classically computable, single-reference state (like Hartree-Fock) to estimate and cancel hardware noise. MREM generalizes this by using a multireference state, which is a truncated linear combination of Slater determinants with substantial overlap to the true ground state [2].

- Procedure:

- Classical Pre-processing: Use an inexpensive classical method (e.g., CASSCF, DMRG) to generate a compact multireference wavefunction composed of a few dominant Slater determinants.

- State Preparation Circuit: Construct the quantum circuit to prepare this multireference state from the initial |0⟩ state. A primary method is to use Givens rotations, which are efficient and preserve physical symmetries like particle number and spin [2].

- Noisy Energy Estimation: Run the circuit on the quantum hardware to measure the energy of this multireference state,

E_MR(noisy). - Classical Energy Calculation: Compute the exact energy of the multireference state on a classical computer,

E_MR(exact). - Error Mitigation: Let

E_target(noisy)be the noisy energy of your target ADAPT-VQE state. The mitigated energy is calculated as:E_target(mitigated) = E_target(noisy) - [E_MR(noisy) - E_MR(exact)][2].

Protocol: High-Precision Measurement with Readout Error Mitigation

This protocol details a measurement strategy to achieve chemical precision for molecular energy estimation despite high readout errors.

- Objective: Reduce measurement errors to the order of 0.1% for precise molecular energy estimation [9].

- Background: Readout errors and finite sampling (shots) are major barriers to accurate observable estimation. This method leverages informationally complete (IC) measurements and detector characterization.

- Procedure:

- Perform Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): Execute a set of calibration circuits to fully characterize the noisy readout process of the device. This builds a model of the measurement noise [9].

- Execute Blended Scheduling: Instead of running all circuits for one task consecutively, interleave (blend) the execution of QDT circuits with the main algorithm circuits (e.g., those for measuring the Hamiltonian). This helps mitigate the impact of slow, time-dependent drifts in the device's noise profile [9].

- Use Locally Biased Random Measurements: When sampling from the IC set, bias the selection towards measurement settings that have a larger impact on the final energy estimation. This optimizes the use of each shot, reducing the total shot overhead required to reach a desired precision [9].

- Post-Process with Inverted Noise Model: Use the noise model from QDT to construct an unbiased estimator for the energy during classical post-processing, effectively canceling out the systematic readout error [9].

Data Presentation: Scaling of Molecular Complexity and Error

Table 1: Scaling of Hamiltonian Complexity with Qubit Count

This table illustrates how the number of terms in a molecular Hamiltonian grows with system size, directly impacting measurement requirements. Data is based on a study of the BODIPY molecule [9].

| Number of Qubits | Number of Pauli Strings in Hamiltonian |

|---|---|

| 8 | 361 |

| 12 | 1,819 |

| 16 | 5,785 |

| 20 | 14,243 |

| 24 | 29,693 |

| 28 | 55,323 |

Table 2: Overhead and Robustness of Different Error Management Techniques

This table compares the key characteristics of the primary error management strategies relevant for NISQ-era algorithms like ADAPT-VQE [10] [2] [11].

| Technique | Key Mechanism | Typical Overhead | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error Suppression | Proactive noise reduction via control pulses (e.g., DRAG, dynamical decoupling). | Low (deterministic, no extra shots). | Reducing error rates per gate/idling; applied to all circuits. |

| Error Mitigation (e.g., ZNE, REM) | Post-processing of results from multiple noisy circuit runs. | High (exponential in worst case), but REM is low-cost. | Extracting more accurate expectation values (like energy) on small-to-medium problems. |

| Multireference EM (MREM) | Uses a classically-derived multi-determinant state for better noise capture. | Moderate (circuit for state prep + classical computation). | Strongly correlated systems where single-reference REM fails. |

| Readout Mitigation (QDT) | Characterizes and inverts the measurement noise model. | Moderate (calibration shots + post-processing). | Achieving high-precision measurements, essential for chemical precision. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Givens Rotation Circuits | A quantum circuit component used to efficiently prepare multireference states, which are superpositions of Slater determinants, from a single reference state [2]. |

| Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements | A set of measurement bases that fully characterize the quantum state, allowing for the estimation of multiple observables and facilitating advanced error mitigation like QDT [9]. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | A calibration procedure that characterizes the actual measurement process of a quantum device, enabling the construction of a noise model that can be inverted to correct readout errors [9]. |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | A hybrid quantum-classical algorithm used to find the ground state energy of a molecular system, forming the backbone for many advanced algorithms like ADAPT-VQE [2]. |

| Reference-State Error Mitigation (REM) | A low-overhead error mitigation technique that uses the known, classically-computable energy of a reference state (e.g., Hartree-Fock) to estimate and cancel hardware noise from the target state's energy [2]. |

| XJB-5-131 | XJB-5-131, MF:C53H80N7O9, MW:959.2 g/mol |

| Macranthoside B | Macranthoside B|Natural Hederagenin Saponin|For Research |

Error Mitigation Strategy Selection and Scaling Workflow

This technical support center provides specialized guidance for researchers employing the ADAPT-VQE algorithm to simulate complex molecules like BODIPY (4,4-difluoro-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene) on quantum hardware. As simulations scale from small models (~8 qubits) to more chemically accurate ones (~28 qubits), managing errors and computational resources becomes paramount. This resource addresses frequent challenges through troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and detailed protocols, framed within the context of error mitigation for ADAPT-VQE research [12] [13].

BODIPY dyes are a class of versatile fluorophores with strong absorption and emission in the visible and near-infrared regions, making them valuable for biomedical applications like sensing, imaging, and photodynamic therapy [14]. Their unique photophysical properties, such as high fluorescence quantum yields and excellent photostability, necessitate precise quantum chemical simulations to guide their development [15] [16]. The ADAPT-VQE algorithm is a promising tool for this task, but its practical application is hindered by significant quantum measurement overhead and circuit depth challenges [12] [13].

# Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our ADAPT-VQE simulation for a BODIPY derivative is not converging to the expected ground state energy. What could be wrong?

A1: Non-convergence can stem from several sources. First, verify the operator pool used. For complex systems like BODIPY, the novel Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool has been shown to outperform traditional fermionic pools, offering faster convergence and reduced circuit depths [12]. Second, check the gradient calculation. Inaccurate gradients, often due to insufficient quantum measurements (shots), can lead the algorithm to select suboptimal operators. Implementing variance-based shot allocation and reusing Pauli measurements can significantly improve gradient fidelity and restore convergence [13]. Finally, ensure your initial state (e.g., Hartree-Fock) is correctly prepared on the quantum register.

Q2: The measurement costs (shot overhead) for our BODIPY simulation are prohibitively high. How can we reduce them?

A2: Shot overhead is a major bottleneck. We recommend two integrated strategies:

- Reuse Pauli Measurements: Pauli strings measured during the VQE parameter optimization in one iteration can be reused for the gradient evaluation in the next ADAPT-VQE iteration. This avoids redundant measurements [13].

- Variance-Based Shot Allocation: Instead of distributing shots uniformly, allocate more shots to Hamiltonian and gradient terms with higher variance. This optimizes the shot budget, focusing resources on the most uncertain measurements [13]. Combining these methods has demonstrated shot reductions of over 99.6% for some molecular systems compared to early ADAPT-VQE versions [12].

Q3: Why is the circuit depth for our BODIPY simulation so high, and how can we mitigate it?

A3: High circuit depth is typical for chemistry-inspired ansätze like UCCSD. ADAPT-VQE inherently helps by building compact, problem-tailored circuits. To further reduce depth:

- Use Hardware-Efficient Pools: Consider pools like the CEO pool or qubit-ADAPT, which are designed for lower CNOT counts [12].

- Monitor CNOT Count: Track the number of CNOT gates, a primary contributor to depth. State-of-the-art ADAPT-VQE improvements have reported CNOT count reductions of up to 88% [12].

- Employ Error Mitigation: For high-depth circuits, use techniques like zero-noise extrapolation to mitigate errors that accumulate with depth.

Q4: We are encountering 'barren plateaus' during the classical optimization. Is ADAPT-VQE susceptible to this?

A4: While hardware-efficient ansätze are highly susceptible to barren plateaus, ADAPT-VQE is empirically and theoretically argued to be more resilient. Its problem-specific, adaptive construction avoids the random parameter initialization that leads to flat energy landscapes. If you suspect a barren plateau, double-check that you are not using a hardware-efficient ansatz by mistake and ensure your operator pool is chemically relevant [12].

Q5: How do we map the specific structure of the BODIPY core to a qubit Hamiltonian?

A5: The process involves several defined steps:

- Define Molecular Geometry: Obtain the Cartesian coordinates for the BODIPY core (C₉H₇BF₂N₂) or its derivative [15].

- Choose a Basis Set: Select a suitable basis set (e.g., 6-31G, cc-pVDZ) for the electronic structure calculation.

- Generate Fermionic Hamiltonian: Use a classical electronic structure package (e.g., PySCF, OpenFermion) to compute the second-quantized Hamiltonian in terms of fermionic creation and annihilation operators [5].

- Qubit Mapping: Transform the fermionic Hamiltonian into a qubit Hamiltonian using a mapping such as Jordan-Wigner or parity encoding [5]. The complexity of the BODIPY molecule means that a minimal basis set simulation will require fewer qubits, while a more accurate calculation with a larger basis set and active space can easily approach 28 qubits or more.

# Troubleshooting Guides

# Guide 1: Resolving Incorrect Gradient Calculations

Incorrect gradients can derail the entire ADAPT-VQE algorithm by selecting the wrong operators [3].

Symptoms:

- Algorithm selects operators with zero gradient that should be non-zero.

- Slow or failed convergence.

- Different results across multiple runs with the same parameters.

Debugging Steps:

- Classical Verification: For a small test system (e.g., Hâ‚‚), compute the gradients classically (e.g., with finite difference) and compare them to your quantum-computed values.

- Check Measurement Statistics: Implement the reused Pauli measurement and variance-based shot allocation protocols to reduce uncertainty in gradient estimates [13].

- Review Operator Pool: Ensure your operator pool is complete and appropriate for the system. For BODIPY, the CEO pool is recommended [12].

- Inspect Commutator Grouping: Verify the grouping of commutators

[H, A_n]for the gradient calculation. Proper grouping (e.g., by Qubit-Wise Commutativity) reduces measurement overhead [13].

Preventative Measures:

- Integrate shot-optimized strategies from the start of your project.

- Use established, well-tested software libraries like OpenVQE for initial setup [5].

# Guide 2: Managing Resource Scaling from 8 to 28 Qubits

Simulating BODIPY across this qubit range presents steeply increasing classical and quantum resource demands [12].

Symptoms:

- Exponentially long simulation times.

- Inability to complete a full ADAPT-VQE cycle within a reasonable timeframe.

- Quantum hardware limitations (noise, decoherence) dominate results.

Mitigation Strategies:

- Leverage Advanced Algorithms: Use the most recent ADAPT-VQE variants like CEO-ADAPT-VQE*, which drastically reduces CNOT counts and measurement costs [12].

- Active Space Approximation: For the 28-qubit simulation, carefully select an active space comprising the most chemically relevant molecular orbitals to reduce the qubit count without sacrificing accuracy.

- Hierarchical Modeling: Start with a smaller model of the BODIPY fluorophore (e.g., the core structure without side chains) at 8 qubits to refine your methodology before scaling up.

- Resource Estimation: Before running on hardware, use classical simulations to estimate the required number of CNOT gates, circuit depth, and shots. Refer to the table below for benchmarks.

Table 1: ADAPT-VQE Resource Evolution for Molecular Systems (at chemical accuracy)

| Molecule | Qubits | Algorithm Variant | CNOT Count | CNOT Depth | Measurement Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH | 12 | Original ADAPT-VQE [12] | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| LiH | 12 | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* [12] | 27% of Baseline | 8% of Baseline | 2% of Baseline |

| H₆ | 12 | Original ADAPT-VQE [12] | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| H₆ | 12 | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* [12] | 12% of Baseline | 4% of Baseline | 0.4% of Baseline |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | Original ADAPT-VQE [12] | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | CEO-ADAPT-VQE* [12] | 21% of Baseline | 7% of Baseline | 1.2% of Baseline |

# Guide 3: Mitigating Noise and Errors on NISQ Hardware

Real quantum devices are noisy, and these errors can corrupt simulation results.

Symptoms:

- Energy estimates are significantly higher than the true ground state energy.

- High variance in measurement outcomes.

- The optimization trajectory is unstable.

Error Mitigation Techniques:

- Readout Error Mitigation: Characterize and correct for bit-flip errors during qubit measurement.

- Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE): Run the same circuit at different noise levels (e.g., by stretching gate times or inserting identities) and extrapolate the result to the zero-noise limit.

- Use Shallow Circuits: The compact circuits produced by state-of-the-art ADAPT-VQE are inherently more resilient to noise [12].

- Validate with Classical Methods: For small active spaces, compare your VQE results with Full CI or DMRG calculations to gauge accuracy.

# Experimental Protocols & Workflows

# Protocol 1: Setting Up a BODIPY Simulation in OpenVQE

This protocol outlines the steps to initiate a fermionic-ADAPT-VQE calculation for a BODIPY molecule using the OpenVQE framework [5].

Materials:

- Classical computer with OpenVQE installed.

- Access to a quantum simulator or hardware.

Methodology:

- System Definition:

- Generate Hamiltonian and Reference State:

- The code automatically generates the qubit Hamiltonian, Hartree-Fock state, and the number of qubits based on the molecular geometry and basis set [5].

- Configure the ADAPT-VQE Algorithm:

- Execution:

- Execute the algorithm and monitor the energy convergence and the gradient norm at each step [5].

Troubleshooting Tip: If the calculation fails to start, verify the molecular geometry input format and that all required Python dependencies are correctly installed.

# Protocol 2: Implementing Shot-Efficient ADAPT-VQE

This protocol details the implementation of shot-reduction techniques from [13].

Objective: To reduce the total number of quantum measurements required for ADAPT-VQE convergence.

Workflow:

- Initial Setup: Perform commutativity grouping (e.g., Qubit-Wise Commutativity) for the Hamiltonian

Hand all gradient observables[H, A_n]once at the beginning. - VQE Optimization Loop: In each ADAPT iteration, during the VQE parameter optimization:

- For each grouped term, perform measurements using variance-based shot allocation.

- Store all the resulting Pauli measurement outcomes.

- Gradient Evaluation for Operator Selection: When calculating gradients for the operator pool:

- Reuse the stored Pauli measurements from step 2 where possible.

- For any remaining terms, apply variance-based shot allocation to new measurements.

- Iterate: Repeat steps 2 and 3 until convergence.

The following diagram visualizes this integrated shot-optimized workflow.

# The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BODIPY Experiments & Simulations

| Item Name | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| BODIPY Core (C₉H₇BF₂N₂) [15] | The fundamental fluorophore structure for simulation and experimental derivation. | Electrically neutral and relatively nonpolar chromophore; starting point for all derivatives. |

| BODIPY FL-X Succinimidyl Ester [16] | Amine-reactive derivative for creating fluorescent conjugates with proteins, peptides, etc. | Contains a spacer to reduce fluorophore-biomolecule interaction. Excitation/Emission: ~503/512 nm. |

| BODIPY TMR-X Succinimidyl Ester [16] | Red-shifted amine-reactive dye for multicolor applications and fluorescence polarization assays. | Spectrally similar to tetramethylrhodamine. Excitation/Emission: ~543/569 nm. |

| BODIPY 630/650-X Succinimidyl Ester [16] | Long-wavelength reactive dye for assays with near-infrared excitation. | Useful for conjugating to nucleotides and oligonucleotides. |

| OpenVQE Software Framework [5] | Open-source Python library for running VQE and ADAPT-VQE simulations. | Supports various operator pools, transformations, and classical optimizers. |

| CEO Operator Pool [12] | A novel, hardware-efficient operator pool for ADAPT-VQE. | Dramatically reduces CNOT count and circuit depth compared to fermionic pools. |

| Shot-Optimization Routines [13] | Custom code for implementing reused Pauli measurements and variance-based shot allocation. | Critical for making ADAPT-VQE simulations of larger molecules like BODIPY feasible. |

| Macranthoside A | Macranthoside A | |

| Ochracenomicin C | Ochracenomicin C, MF:C19H20O5, MW:328.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

# Visualizing the ADAPT-VQE Algorithm Logic

The following diagram illustrates the core iterative logic of the ADAPT-VQE algorithm, highlighting key decision points and error-prone steps discussed in the troubleshooting guides.

A Toolkit for Precision: Practical Error Mitigation Methods for ADAPT-VQE

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the key differences between Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) and Twirled Readout Error Extinction (TREX), and when should I choose one over the other for my ADAPT-VQE experiment?

The choice depends on your experiment's specific requirements for precision, available quantum resources, and the need for a calibrated noise model.

- Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) is an informationally complete (IC) measurement method that fully characterizes the noisy measurement process by constructing a positive operator-valued measure (POVM) for the device [9]. It is ideal for experiments requiring the highest possible precision and where the same measurement data is reused to estimate multiple observables [9]. For example, in algorithms like ADAPT-VQE or qEOM, QDT allows you to mitigate readout errors and use the same data for energy estimation and other observable calculations [9]. However, QDT requires an initial tomography step, which adds to the circuit overhead.

- Twirled Readout Error Extinction (TREX), also known as SPAM Twirling, works by diagonalizing the readout noise channel through random bit flips [17]. It is less resource-intensive than QDT as it does not require full detector characterization. TREX is an excellent choice for near-term devices where you need a robust and simpler-to-implement method to reduce bias in expectation values, such as in the final measurement phase of a variational algorithm [17].

The following table summarizes the core differences:

| Feature | Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | Twirled Readout Error Extinction (TREX) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Characterizes the measurement detector via tomography to build an error model [9] [18]. | Diagonalizes noise by applying random bit flips before measurement [17]. |

| Informationally Complete | Yes [9]. | No. |

| Primary Use Case | High-precision estimation of multiple observables from the same data set [9]. | Efficient mitigation for expectation value estimation [17]. |

| Key Advantage | Enables unbiased estimation via the noisy POVM; allows for advanced post-processing [9] [19]. | Simpler implementation; no need for a detailed noise model [17]. |

| Resource Overhead | Higher (requires initial calibration circuits) [9]. | Lower (can be integrated into the main experiment) [17]. |

| Dictyopanine A | Dictyopanine A, MF:C25H34O5, MW:414.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Apicularen B | Apicularen B, MF:C33H44N2O11, MW:644.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Q2: My molecular energy calculations on a real device are consistently outside chemical precision. How can I determine if readout error is the primary culprit, and which mitigation technique is most effective?

A systematic approach can help you diagnose and address this issue. First, run a simple test: prepare and immediately measure the Hartree-Fock state (which requires no two-qubit gates) and compute the energy expectation value [9]. Since this circuit is dominated by readout errors and not gate errors, a large deviation from the theoretical value indicates significant readout noise. Research has shown that with techniques like QDT, it is possible to reduce the measurement error on a Hartree-Fock state from 1-5% down to 0.16% on current hardware, bringing it close to chemical precision [9].

For a more granular diagnosis, you can use a separate quantification protocol to distinguish State Preparation and Measurement (SPAM) errors [19]. This helps you understand whether the inaccuracy originates more from initializing the state or from the final measurement.

The most effective technique depends on your goal. For the highest precision in complex molecules, QDT combined with advanced scheduling has demonstrated the ability to achieve errors as low as 0.16% [9]. For a more general-purpose and lightweight method, TREX can significantly improve expectation values without the need for full detector characterization [17].

Q3: The hardware's readout error characteristics seem to change over time. How can I account for this temporal drift in my protracted ADAPT-VQE optimization runs?

Temporal drift is a significant challenge for long-running experiments like ADAPT-VQE. Two practical strategies can mitigate this:

- Blended Scheduling: This technique involves interleaving the execution of your main experiment circuits (e.g., energy estimation for the ansatz state) with calibration circuits (e.g., for QDT) in the same job queue [9]. By blending these circuits, you ensure that the calibration data used for mitigation is collected under nearly identical conditions as the experiment data, accounting for short-term drift.

- Frequent Recalibration: For TREX, this means regularly updating the calibration factors. For QDT, it requires periodically re-running the detector tomography, which can be done in a blended manner [9]. The frequency of recalibration should be determined based on the observed stability of the quantum processor you are using.

Q4: How does the performance of readout error mitigation scale with the number of qubits in my active space?

The mitigation performance and its resource overhead are highly dependent on the number of qubits. The core challenge is that the number of Pauli strings in a molecular Hamiltonian grows as ( \mathcal{O}(N^4) ) with the number of spin-orbitals (qubits) N [9]. The following table illustrates this rapid growth:

| Qubits (Active Space) | Number of Pauli Strings |

|---|---|

| 8 (4e4o) | 361 |

| 12 (6e6o) | 1,819 |

| 16 (8e8o) | 5,785 |

| 20 (10e10o) | 14,243 |

| 24 (12e12o) | 29,693 |

| 28 (14e14o) | 55,323 |

Both QDT and TREX must contend with this scaling. While the fundamental characterization for TREX may be simpler, techniques like Locally Biased Random Measurements for QDT are designed to reduce the "shot overhead" (number of measurements) for large systems by prioritizing the most informative measurement settings [9].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Quantum Detector Tomography for Molecular Energy Estimation

This protocol outlines the steps for using QDT to mitigate readout errors in the estimation of a molecular energy, such as in an ADAPT-VQE simulation [9].

- State Preparation: Prepare the quantum state of interest on the processor. For isolating measurement errors, start with a simple state like the Hartree-Fock state [9].

- Perform Informationally Complete Measurements: Instead of measuring only in the computational basis, execute a set of measurements that form an informationally complete basis. In practice, this is often achieved by applying a random Clifford rotation to the state before a computational basis measurement [9].

- Quantum Detector Tomography: Characterize the noisy detector. This involves preparing a complete set of basis states (e.g., |0⟩, |1⟩ for each qubit) and measuring them to construct the POVM that describes the real measurement process [9] [18].

- Construct the Mitigated Estimator: Use the POVM obtained from QDT to create an unbiased estimator for the expectation values of the Pauli operators that constitute the molecular Hamiltonian [9] [19].

- Blended Execution: To mitigate time-dependent noise, use a blended scheduler that interleaves the circuits from steps 2 and 3 on the hardware [9].

- Post-Processing: Classically compute the energy expectation value using the mitigated estimator and the measurement data from the IC measurements [9].

The workflow for this protocol, including its integration with a broader VQE loop, is shown below.

Protocol 2: Applying TREX (SPAM Twirling) for Error Mitigation

This protocol details the steps for implementing the TREX technique to mitigate readout errors [17].

Obtain Calibration Data (Bit-Flip Averaging - BFA):

- Initialize all qubits in the |0...0⟩ state.

- Divide the total number of shots into

nbatches. - For each batch, randomly select a subset of qubits to apply an X-gate (bit-flip) immediately before measurement.

- For each shot in the batch, apply the classical NOT operation to the corresponding bits in the output bitstring.

- Aggregate the results from all batches to form a calibration dataset [17].

Run the Quantum Experiment under BFA:

- Prepare your desired parameterized circuit (e.g., the ADAPT-VQE ansatz).

- Repeat the same BFA subroutine used in step 1: divide shots, apply random X-gates before measurement, and flip bits classically after measurement [17].

Correct Expectation Values:

- Use the calibration data to compute corrected expectation values for each term in the Hamiltonian.

- Combine all corrected terms to obtain the final, mitigated energy expectation value [17].

The following diagram illustrates the core TREX workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This section lists key computational "reagents" and resources essential for implementing the readout error mitigation techniques discussed.

| Item | Function in Experiment | |

|---|---|---|

| Informationally Complete (IC) Measurement Data | The set of measurement outcomes from a basis that fully characterizes the quantum state, enabling the estimation of multiple observables and the application of QDT [9]. | |

| Calibrated POVM (from QDT) | The mathematical description of the noisy measurement detector, used to construct an unbiased estimator for mitigating readout errors in expectation value calculations [9] [18] [19]. | |

| Bit-Flip Averaging (BFA) Calibration Data | The calibration results obtained by measuring the | 0⟩ state with random bit-flips, used in TREX to correct for readout noise in subsequent experiments [17]. |

| Molecular Hamiltonian (Pauli Decomposition) | The target observable, expressed as a weighted sum of Pauli strings. The complexity of this decomposition (number of terms) is a major factor in measurement scaling [9] [1]. | |

| Hartree-Fock State Preparation Circuit | A simple, noiseless circuit to prepare a separable reference state. Crucial for benchmarking and isolating measurement errors from gate errors [9]. | |

| Prinomastat hydrochloride | Prinomastat hydrochloride, CAS:1435779-45-5, MF:C18H22ClN3O5S2, MW:460.0 g/mol | |

| Haematocin | Haematocin |

This technical support guide provides essential methodologies and troubleshooting for researchers implementing Zero-Noise Extrapolation in quantum chemistry simulations, particularly within ADAPT-VQE research for drug development.

Core Principles and Common Issues

What is the fundamental principle behind Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE)?

ZNE is an error mitigation technique that extrapolates the noiseless expectation value of an observable from multiple expectation values computed at different intentionally increased noise levels. The method operates in two key stages: first, systematically scaling the noise in the quantum circuit, and second, extrapolating the results back to the zero-noise limit [20]. This approach is particularly valuable for ADAPT-VQE research where accurate ground state energy calculations are essential for molecular simulation in drug development.

What are the most common ZNE implementation failures in ADAPT-VQE workflows?

The most frequent issues include: (1) Inaccurate extrapolation due to poor choice of scaling factors or extrapolation model, (2) Excessive circuit depth from noise scaling that leads to unmanageable noise, and (3) Statistical uncertainty amplification from propagating measurement errors through the extrapolation process [21]. These problems are particularly pronounced in ADAPT-VQE where circuits are deep and measurements numerous.

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem 1: Poor extrapolation accuracy

Symptoms: Large variance in mitigated results, inconsistent improvement across circuit executions, or physically impossible energy values (e.g., violating variational principle).

Solutions:

- Validate extrapolation model choice: Test multiple models (linear, polynomial, exponential) against known benchmark systems. Research indicates polynomial models often outperform others for depolarizing noise [22] [23].

- Optimize scale factors: Use at least three scale factors (e.g., [1, 2, 3]) and ensure they provide sufficient leverage for extrapolation without excessive noise [22] [24].

- Increase measurement shots: Compensate for error amplification by increasing shots proportionally to the square of the scale factors to maintain constant uncertainty [21].

Verification protocol: Run ZNE on a simple molecular system (like Hâ‚‚) with known theoretical energy values. Compare mitigated and unmitigated results across 10 iterations - successful mitigation should show consistent improvement toward the theoretical value.

Problem 2: Circuit depth explosion after folding

Symptoms: Quantum circuits become too deep to execute reliably, resulting in complete noise domination or hardware execution failures.

Solutions:

- Implement local folding: Instead of global circuit folding, apply folding selectively to shorter gate sequences to better manage depth increase [20] [24].

- Circuit compression pre-processing: Optimize circuits using compiler techniques before applying ZNE to minimize initial gate count [25].

- Hybrid mitigation: Combine ZNE with other techniques like measurement error mitigation or Pauli twirling to reduce the required scale factors [21] [26].

Depth management check: Calculate the predicted depth after folding: final_depth = original_depth × (1 + 2 × n_folds). If this exceeds your hardware's coherence time limits, reduce the maximum scale factor.

Problem 3: Incompatibility with parameter-shift rules in ADAPT-VQE

Symptoms: Gradient calculations become unreliable when ZNE is applied, causing ADAPT-VQE's operator selection to fail or converge poorly.

Solutions:

- Apply consistent folding patterns: Ensure identical folding is applied across all circuit evaluations for gradient calculations to maintain consistent noise scaling [27].

- Use ZNE only for energy evaluation: Implement ZNE solely for the final energy measurement in each ADAPT-VQE iteration, not during the operator selection phase where gradients are computed [25] [27].

- Leverage JIT compilation: Use frameworks like PennyLane with Catalyst to ensure reproducible noise scaling across all circuit executions [24].

Implementation Protocols

Standardized ZNE Protocol for ADAPT-VQE

For researchers implementing ZNE within ADAPT-VQE workflows, follow this standardized procedure:

Circuit Preparation [25]

- Pre-compress quantum circuits using compiler optimizations

- Transpile to basis gates compatible with your noise model

- Set initial parameters using pre-training or classical simulations

Noise Scaling Configuration [20] [23]

- Select scaling method: unitary folding (global or local) or pulse stretching

- Choose scale factors: recommended [1.0, 2.0, 3.0] for initial experiments

- Implement folding using:

U → U(U†U)^nwhere n determines the scale factor

-

- Select extrapolation model: Richardson, polynomial, or exponential

- For polynomial model: set order to

number_of_scale_factors - 1 - Configure measurement shots: scale as

shots_base × (scale_factor)²to maintain statistical precision

Execution and Validation

- Execute noise-scaled circuits on target device or simulator

- Perform extrapolation to zero-noise limit

- Validate against classical benchmarks where available

The workflow can be visualized as follows:

Experimental Validation Protocol

When implementing ZNE for ADAPT-VQE research, include these validation steps:

- Benchmark with known systems: Test on diatomic molecules (Hâ‚‚, LiH) with classically computable ground truths [25]

- Statistical significance testing: Run multiple iterations (minimum 10) to establish error bar improvements

- Control experiments: Compare against unmitigated results and theoretical values

- Convergence monitoring: Track ADAPT-VQE convergence with and without ZNE applied

Technical Reference Tables

Comparison of Noise Scaling Methods

| Method | Implementation | Advantages | Limitations | Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unitary Folding | Map G → GG†G [20] | No device access required, digital implementation | Increases circuit depth significantly | Gate-based models, NISQ devices |

| Global Folding | Apply to entire circuit: U → U(U†U)^n [24] | Uniform scaling, simple implementation | Can dramatically increase circuit depth | Small to medium circuits |

| Local Folding | Apply to individual gates [24] | Finer control over depth increase | More complex implementation | Large circuits, specific noise regions |

| Pulse Stretching | Increase pulse duration [20] | More physical noise scaling | Requires pulse-level access | High-control hardware platforms |

Extrapolation Techniques Comparison

| Method | Function Form | Parameters | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | f(λ) = a + bλ [20] | 2 parameters | Mild noise dependence | Simplest, requires minimal data points |

| Polynomial | f(λ) = pâ‚€ + pâ‚λ + ... + pₙλ⿠[20] [23] | Order n, n+1 parameters | Various noise types | Can overfit with high order |

| Exponential | f(λ) = a + be^(-cλ) [22] [24] | 3 parameters | Decoherence noise | More parameters require more scale factors |

| Richardson | Polynomial with order = points-1 [20] | n points, order n-1 | Exact fitting at points | Sensitive to measurement noise |

ZNE Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool/Platform | Function | Implementation Example | Use in ADAPT-VQE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitiq | ZNE library | mitigate_with_zne(circuit, scale_factors=[1,2,3]) [20] [21] |

Error mitigation in energy evaluation |

| Qiskit ZNE | Prototype implementation | zne.execute_with_zne(circuit, executor) [28] |

IBM hardware deployments |

| PennyLane-Catalyst | JIT-compiled ZNE | @qml.qjit decorator with ZNE [24] |

Gradient-based optimizations |

| OpenQAOA | Quantum optimization | q.set_error_mitigation_properties(factory='Richardson') [22] |

QAOA and optimization problems |

Frequently Asked Questions

How does ZNE specifically benefit ADAPT-VQE compared to other error mitigation techniques?

ZNE is particularly suitable for ADAPT-VQE because it doesn't require detailed noise model characterization, works with existing circuit executions, and directly improves energy estimation - the core objective of VQE algorithms. Unlike techniques requiring specific noise models, ZNE's model-agnostic approach makes it adaptable across different quantum hardware platforms used in research environments [25] [27].

What is the typical overhead cost of implementing ZNE, and how does it scale with problem size?

The primary overhead is circuit execution time, which scales linearly with the number of scale factors. For example, using three scale factors requires approximately 3× the execution time. Circuit depth increases with folding method - global folding can triple depth at scale factor 3, while local folding may have more moderate increases. The extrapolation computational overhead is negligible compared to quantum execution times [20] [23].

Can ZNE be combined with other error mitigation techniques for enhanced results in molecular simulations?

Yes, research demonstrates successful combination with other techniques. For example, ZNE can be applied after measurement error mitigation to address different noise sources, or combined with symmetry verification to exploit molecular symmetries. Recent work shows neural-network-enhanced ZNE providing improved accuracy for molecular ground state calculations [25] [26].

What are the fundamental limitations of ZNE that researchers should recognize?

ZNE cannot completely eliminate errors and is susceptible to extrapolation errors if the noise scaling doesn't match the assumed model. The method also amplifies statistical uncertainty, as errors in measured expectation values propagate to the extrapolated result. For complex noise channels or highly noisy circuits, ZNE may provide limited improvement [21].

How do I select optimal scale factors for a completely new molecular system or hardware platform?

Start with a characterization experiment using a simple circuit on your target hardware. Measure expectation values at multiple scale factors (e.g., [1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3]) and observe the trend. If the relationship appears linear, fewer scale factors may suffice. For curved trends, use more scale factors with polynomial extrapolation. The optimal choice often depends on the specific noise characteristics of your hardware [22] [23].

FAQs: Core Concepts and Applications

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between REM and MREM?

REM (Reference-state Error Mitigation) is a cost-effective, chemistry-inspired method that uses a single, classically-solvable reference state (typically the Hartree-Fock state) to estimate and correct noise-induced errors in variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) experiments. Its effectiveness is high for weakly correlated systems where a single Slater determinant provides a good approximation of the ground state. However, for strongly correlated systems, where the true wavefunction is a linear combination of multiple determinants with similar weights, the single-reference assumption breaks down, limiting REM's utility. MREM (Multireference-state Error Mitigation) directly addresses this limitation by systematically incorporating multireference states, which are linear combinations of dominant Slater determinants, thereby extending robust error mitigation to a wider variety of molecular systems, including those with pronounced electron correlation [2] [29].

Q2: When should I consider using MREM in my ADAPT-VQE experiments?

You should consider implementing MREM in the following scenarios [2]:

- When simulating molecules in bond-dissociation or bond-stretching regions, where strong electron correlation is significant.

- When the energy error from your noisy ADAPT-VQE calculation remains unacceptably high even after applying single-reference REM.

- When you have access to a classically inexpensive method (e.g., CASSCF, CID) to generate a compact multireference wavefunction with substantial overlap with the true ground state.

Q3: My ADAPT-VQE algorithm is not converging as expected. What could be wrong?

Unexpected convergence behavior in ADAPT-VQE can stem from several issues. As evidenced by one user's experience, you might encounter gradients that are zero when they should not be, and slower convergence requiring more iterations than anticipated [3]. Potential causes and checks include:

- Operator Pool: Verify that your operator pool is complete and appropriate for the molecule. An insufficient pool can lead to stalled convergence.

- Initial State: Ensure the initial Hartree-Fock state is correctly prepared.

- Gradient Calculation: Confirm the method used to compute the gradients ( \frac{\partial E}{\partial \thetam} = \langle \Psi | [\hat{H}, \hat{A}m] | \Psi \rangle ) is implemented correctly, as errors here directly impact operator selection [5] [30].

- Classical Optimizer: The choice of classical optimizer (e.g., COBYLA, L-BFGS-B) and its parameters (tolerance, maximum iterations) can significantly affect convergence performance [5] [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Ineffective Error Mitigation with Single-Reference REM

Problem: The application of REM does not sufficiently reduce the energy error, likely due to the system being strongly correlated.

Solution: Implement the MREM protocol.

- Diagnose: Check the overlap between your Hartree-Fock reference state and the target ground state. A small overlap suggests strong correlation and the need for MREM.

- Generate MR State: Use an inexpensive classical method (e.g., selected CI, DMRG, or CASSCF) to generate a compact multireference wavefunction composed of a few dominant Slater determinants.

- Prepare Circuit: Construct a quantum circuit to prepare this MR state. A highly effective method is using Givens rotations, which are universal for state preparation and preserve physical symmetries like particle number and spin [2].

- Apply MREM: Use this MR state as your new, more sophisticated reference within the established REM framework to achieve a more accurate noise estimation and mitigation [2].

Issue: Incorrect Gradients in ADAPT-VQE

Problem: The gradients for operators in the pool are computed as zero or near-zero, preventing the algorithm from selecting the correct operators to grow the ansatz [3].

Resolution Steps:

- Verification: Double-check the generation of your operator pool. Ensure all relevant single and double (or other) excitations are included.

- Hamiltonian Mapping: Confirm the fermion-to-qubit mapping (e.g., Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev) is applied consistently to both the Hamiltonian and all operators in the pool [30].

- Wavefunction Evaluation: Verify that the current ansatz state ( |\Psi^{(n)}{\text{ADAPT}} \rangle ) is being evaluated correctly for the gradient calculation ( \langle \Psi | [\hat{H}, \hat{A}m] | \Psi \rangle ) [30].

- Protocol Check: If using a software framework like InQuanto, ensure that the correct protocol (e.g.,

SparseStatevectorProtocol) is being used to calculate the required gradients [30].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Protocol: Implementing MREM with Givens Rotations

This protocol outlines the steps to mitigate errors in a VQE calculation for a strongly correlated molecule using the MREM method.

Objective: To improve the accuracy of the ground state energy estimation for a strongly correlated molecule (e.g., Fâ‚‚) by leveraging a multireference state for error mitigation.

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for implementing MREM.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- System Identification: Identify that your molecule (e.g., Fâ‚‚ at a stretched bond length) exhibits strong electron correlation, making it a suitable candidate for MREM [2].

- Classical MR Calculation: Run an inexpensive classical multireference calculation, such as Complete Active Space Configuration Interaction (CASCI) or Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG), to obtain an approximate wavefunction for the target state.

- State Truncation: From the full wavefunction, select the Slater determinants with the largest weights (e.g., the top 3-5 determinants) to form a compact, truncated multireference state ( |\Psi_{MR}\rangle ). This balances expressivity and noise sensitivity [2].

- Quantum Circuit Construction:

- Use Givens rotations to efficiently construct a quantum circuit that prepares ( |\Psi_{MR}\rangle ) from an initial computational basis state.

- Givens rotations are preferred for their symmetry preservation (particle number, spin) and structured, efficient hardware implementation [2].

- Hardware Execution:

- Prepare the MR state on the noisy quantum device using the constructed circuit.

- Measure the energy of this state on the hardware, ( E_{noisy}^{MR} ).

- Classical Reference Calculation: Classically compute the exact energy ( E{exact}^{MR} ) for the same multireference state ( |\Psi{MR}\rangle ). This is feasible because the state is composed of only a few determinants.

- Noise Estimation: The hardware noise bias for the MR state is calculated as ( \Delta{MR} = E{noisy}^{MR} - E_{exact}^{MR} ).

- Error Mitigation: Run your target VQE algorithm to obtain a noisy energy ( E{noisy}^{VQE} ). The mitigated energy is then given by: ( E{mitigated}^{VQE} = E{noisy}^{VQE} - \Delta{MR} ) This correction assumes the noise affecting the MR state is representative of the noise affecting the target VQE state [2].

The following tables summarize key performance data from the research on MREM and related methods.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Error Mitigation Methods on Test Molecules [2]

| Molecule | Correlation Strength | Unmitigated VQE Error (Ha) | REM Error (Ha) | MREM Error (Ha) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚O | Weak | - | High Reduction | Comparable to REM | REM is sufficient for weak correlation. |

| Nâ‚‚ | Moderate | - | Significant Residual Error | Further Reduction | MREM shows improvement over REM. |

| Fâ‚‚ | Strong | - | Limited Effectiveness | Highest Improvement | MREM is crucial for strong correlation. |

Table 2: ADAPT-VQE Convergence Benchmarks (Hâ‚‚ Molecule in 6-31G basis) [5]

| Metric | Value / Observation |

|---|---|

| Qubits | 8 |

| Converged Energy | -1.1516 Ha |

| Fidelity with FCI | 0.999 |

| Fermionic ADAPT Iterations | 5 |

| Total CNOT Gate Count | 368 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational "Reagents" for MREM and ADAPT-VQE Experiments

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example in Protocol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical MR Solver | Generates the initial multireference wavefunction. | CASCI, DMRG, or selected CI calculation [2]. | |

| Givens Rotation Circuits | Efficiently prepares multireference states on quantum hardware while preserving symmetries [2]. | Circuit for preparing ( | \Psi_{MR}\rangle ) from a reference determinant. |

| Operator Pool | The set of operators from which the ADAPT-VQE algorithm builds the ansatz. | Pool of spin-complemented anti-Hermitian UCCSD operators [30] [32]. | |

| Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping | Transforms the electronic Hamiltonian and operators into a form executable on a qubit-based quantum computer. | Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation [2] [30]. | |

| Classical Optimizer | Adjusts the parameters of the quantum circuit to minimize the energy expectation value. | COBYLA, L-BFGS-B, or ADAM [5] [4]. | |

| Fluvirucin B2 | Fluvirucin B2 | Fluvirucin B2 is a macrolactam antibiotic for research use only (RUO). It is not for human, veterinary, or household use. Explore its potential applications. | |

| Ombuoside | Ombuoside, MF:C29H34O16, MW:638.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

## Troubleshooting Guides

### Guide 1: Resolving High Shot Overhead in ADAPT-VQE

Problem: The ADAPT-VQE algorithm requires an impractically high number of quantum measurement shots to achieve chemical accuracy, making experiments on real hardware too costly and time-consuming [33] [13].

Explanation: The high shot overhead originates from two main sources: the measurements needed for the classical parameter optimization of the variational ansatz and the additional measurements required for the operator selection step in each adaptive iteration. Each of these requires evaluating the expectation values of numerous Pauli operators [13].

Solution: Implement an integrated strategy combining Pauli measurement reuse and variance-based shot allocation [33] [13].

- Step 1: Reuse Pauli Measurements. In the standard ADAPT-VQE workflow, the Pauli terms measured for energy estimation during the VQE parameter optimization are often similar or identical to those needed for calculating the gradients in the subsequent operator selection step. Systematically cache these measurement outcomes and reuse them in the next ADAPT iteration to avoid redundant measurements [13].

- Step 2: Apply Variance-Based Shot Allocation. Instead of distributing measurement shots uniformly across all Pauli terms, allocate more shots to terms with higher estimated variance. This strategy minimizes the overall statistical error in the energy and gradient estimations for a given total shot budget [33] [34] [13].

- Variance-Preserved Shot Reduction (VPSR): This dynamic method aims to minimize the total number of shots while preserving the variance of measurements throughout the VQE optimization process [34].

- Verification: After implementation, monitor the shot count required to reach chemical accuracy for test molecules like Hâ‚‚ or LiH. Successful application should result in a significant reduction (e.g., 30-50%) in total shots used without compromising the fidelity of the final result [13].

### Guide 2: Addressing Inefficient Operator Pool Evaluation

Problem: The process of evaluating the entire operator pool to select the one with the largest gradient is a major bottleneck, contributing significantly to the measurement cost of each ADAPT-VQE iteration [12] [13].

Explanation: The operator pool can be large, and measuring the commutator (gradient) for each operator with the Hamiltonian is expensive. A naive sequential measurement approach is highly inefficient.

Solution: Use commutativity-based grouping for simultaneous measurement of multiple operators [13].

- Step 1: Group Commuting Terms. Analyze the Pauli terms that make up the gradients for all operators in your pool. Group those that commute (e.g., via qubit-wise commutativity) into the same set.

- Step 2: Measure Groups Simultaneously. Each group of commuting operators can be measured in a single quantum circuit, drastically reducing the number of distinct circuit executions required per iteration.

- Verification: The number of unique circuits required to evaluate the entire operator pool should decrease substantially. This method is compatible with the shot reuse and allocation strategies from Guide 1 [13].

## Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the core components of a shot-efficient ADAPT-VQE protocol?

The essential methodological components for reducing measurement overhead are summarized in the table below.

| Component | Description | Key Function |

|---|---|---|

| Pauli Measurement Reuse [13] | Caching and reusing measurement outcomes from the VQE optimization step in the subsequent operator selection step. | Eliminates redundant measurements of identical Pauli strings across different stages of the algorithm. |

| Variance-Based Shot Allocation [33] [34] [13] | Dynamically allocating more measurement shots to Pauli terms with higher variance. | Optimizes the shot budget to minimize the overall statistical error in energy and gradient estimates. |

| Commutativity-Based Grouping [13] | Grouping Hamiltonian and gradient terms into mutually commuting sets for simultaneous measurement. | Reduces the number of unique quantum circuits that need to be executed. |