Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Techniques: A Comparative Analysis for Quantum Simulation in Drug Discovery and Materials Science

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of advanced fermion-to-qubit mapping techniques, crucial for simulating molecular and materials systems on quantum computers.

Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Techniques: A Comparative Analysis for Quantum Simulation in Drug Discovery and Materials Science

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of advanced fermion-to-qubit mapping techniques, crucial for simulating molecular and materials systems on quantum computers. We explore foundational concepts, from fundamental fermion statistics to the core principles of popular encodings like Jordan-Wigner and Bravyi-Kitaev. The analysis then delves into cutting-edge methodological frameworks, including Hamiltonian-adaptive and SAT-based compilers, and addresses critical troubleshooting aspects like qubit overhead and Pauli weight optimization. Finally, we validate these techniques through real-world applications in drug discovery and materials simulation, highlighting performance metrics and offering guidance for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to leverage quantum computation.

The Quantum Bridge: Understanding Fermions, Qubits, and Why Mapping Matters

Simulating fermionic systems is one of the most promising applications of quantum computing, with profound implications for drug development, materials science, and quantum chemistry [1] [2]. However, a fundamental challenge arises from the disparate statistical properties governing fermions and qubits. Fermionic systems, composed of electrons, protons, and neutrons, exhibit wavefunction antisymmetry under particle exchange, requiring anticommutation relations for their creation and annihilation operators [2]. In contrast, quantum computers are built from qubits that obey bosonic commutation relations. This statistical mismatch means that local fermionic operators translate to non-local qubit operators with high Pauli weight (acting on many qubits), creating significant implementation overhead on digital quantum devices [2] [3].

This article provides a comparative analysis of fermion-to-qubit mapping techniques, examining their theoretical foundations, experimental performance, and practical implications for research applications. We focus specifically on the crucial metrics of Pauli weight, circuit depth, and implementation costs that directly impact simulation accuracy and efficiency on near-term quantum hardware.

Mapping Fundamentals: From Fermionic Modes to Qubit Operators

The Core Challenge

Fermion-to-qubit encoding is an isometry that maps the Fock space of â„‹ð‘“ to the Hilbert space of ð‘ð‘ž qubits â„‹ð‘ž [4]. The central difficulty lies in preserving the fermionic anticommutation relations {ð‘Žð‘—,ð‘Žð‘˜} = 0 and {ð‘Žð‘—,ð‘Žð‘˜â€ } = ð›¿ð‘—𑘠within the qubit framework where Pauli operators typically commute [4] [2]. This requirement forces the mapping to introduce non-local dependencies, fundamentally constraining the potential locality of any encoding scheme [3].

Theoretical work has established that fully local mappings are only possible if the locality graph of the fermionic system is a tree [3]. For complex systems with cyclic connectivity (such as regular 2D lattices common in chemical systems), any exact encoding must introduce non-locality, meaning even simple fermionic computations translate to more complex qubit circuits with overhead that can scale with system size [3].

Established Mapping Techniques

Several theoretically-derived mappings form the foundation of fermionic simulation:

- Jordan-Wigner Transformation (JWT): The historically first mapping that encodes occupation information locally but requires ð‘‚(ð‘) non-local string operators for interactions [2].

- Bravyi-Kitaev Transformation (BKT): Balances locality of occupation and parity information, achieving ð‘‚(logð‘) Pauli weight for single creation/annihilation operators [2].

- Ternary-Tree Mappings: A more recent formalism that encompasses and generalizes conventional mappings, providing a framework for understanding asymptotic optimality with Pauli weight of ð‘‚(√ð‘) [1] [2].

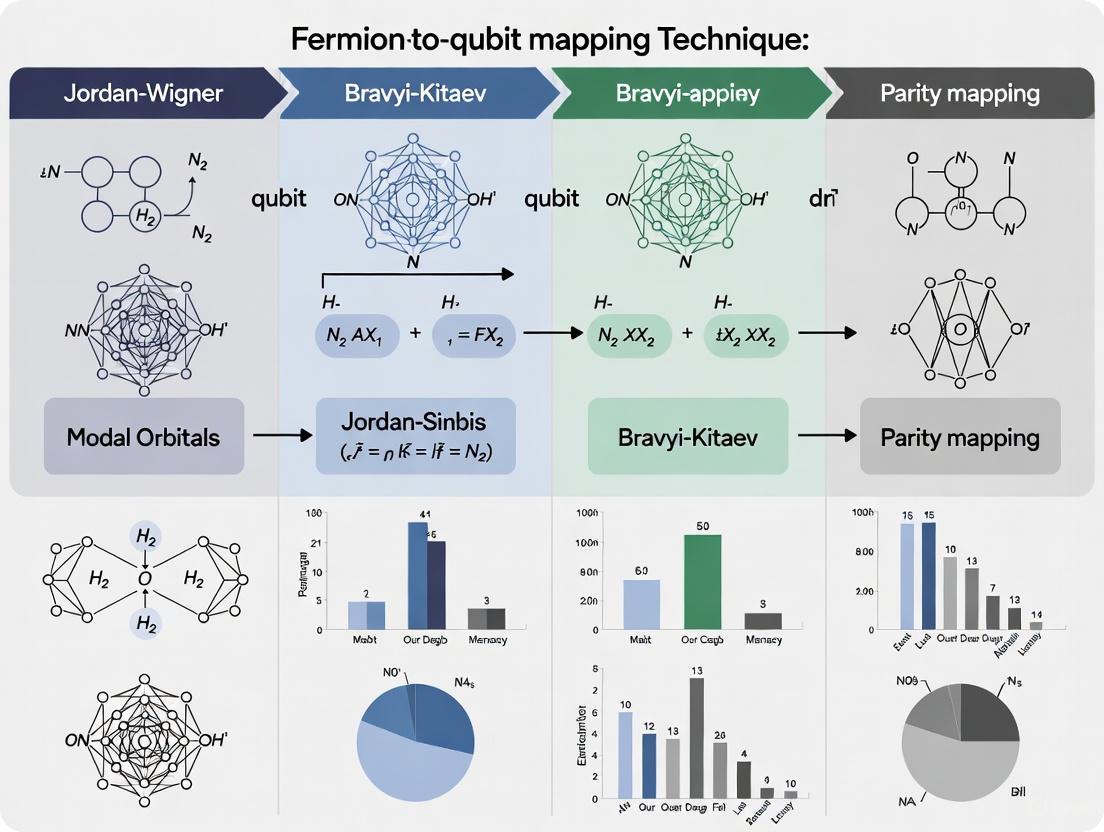

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow and challenge of fermion-to-qubit mapping:

Comparative Analysis of Mapping Approaches

Hamiltonian-Tailored Optimization Methods

Recent approaches have moved beyond one-size-fits-all mappings to develop techniques tailored to specific problem Hamiltonians:

Clifford Circuit-Based Heuristic Optimization: This approach reformulates the mapping problem as a Clifford circuit optimization task, using simulated annealing to minimize the average Pauli weight of the problem Hamiltonian [1] [2]. The method generates new mappings by applying Clifford circuits to existing ternary-tree mappings, preserving the fermionic algebra while exploring a broader space of possible encodings [2].

Fermihedral SAT Framework: This compiler-based approach formalizes all encoding constraints (anticommutivity, algebraic independence, vacuum state preservation) as a Boolean Satisfiability problem solvable with high-performance SAT solvers [5]. For larger-scale problems, it employs approximation techniques to manage the exponentially large clause space while maintaining near-optimal solutions [5].

Fermion Routing Advancements: Focused on the overhead from permuting fermionic modes, recent work has demonstrated that fermion routing can be performed in ð‘‚(log²ð‘) depth without ancillas, measurements, or feedforward, and in ð‘‚(logð‘) depth when these resources are available [4]. Efficient mappings between product-preserving ternary-tree encodings further reduce this overhead [4].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes key performance metrics across different mapping techniques:

| Mapping Approach | Pauli Weight Reduction | Key Advantages | Implementation Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner (JWT) | Baseline (Reference) | Simple implementation; Minimal qubit count [2] | ð‘‚(ð‘) string operators; High circuit depth |

| Bravyi-Kitaev (BKT) | Moderate improvement | ð‘‚(logð‘) weight for single operators [2] | Moderate implementation complexity |

| Ternary-Tree Mappings | Asymptotically optimal | Unified framework; Optimal for single operators [1] | Complex compilation; Not Hamiltonian-specific |

| Clifford-Based Optimization | 15-40% improvement [1] | Hamiltonian-tailored; Maintains term count [2] | 3-day optimization on single CPU [2] |

| Fermihedral SAT | 10-60% lower cost [5] | Formal guarantees; Potentially optimal | Exponential clauses; Requires approximations |

For specific model systems, optimized mappings demonstrate substantial improvements:

- 6×6 2D Nearest-Neighbor Hopping: >40% reduction in average Pauli weight compared to ternary-tree mappings [1] [2]

- 6×6 2D Hubbard Model: >20% reduction in average Pauli weight [1] [2]

- Hydrogen Chain (6-site): 10-20% improvement over conventional mappings [2]

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Methodological Tools

The table below details key computational tools and their functions in mapping research:

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Clifford Circuits | Generate symmetry-preserving mapping transformations [1] [2] | Heuristic mapping optimization |

| SAT Solvers | Solve constrained optimization for optimal encoding [5] | Fermihedral compilation framework |

| Simulated Annealing | Heuristic search over Clifford circuit space [1] | Numerical mapping optimization |

| Ternary-Tree Framework | Theoretical construct for understanding mapping optimality [1] [4] | Mapping classification and analysis |

| fSWAP Networks | Permute fermionic modes while maintaining statistics [4] | Fermion routing in Jordan-Wigner encoding |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Clifford-Based Optimization Workflow

The heuristic optimization approach follows a structured protocol:

- Initialization: Begin with a ternary-tree based mapping as the starting point [2]

- Circuit Parameterization: Represent the mapping transformation as a Clifford circuit with parametrized gates [1] [2]

- Cost Function Evaluation: Calculate the average Pauli weight of the problem Hamiltonian under the current mapping [2]

- Simulated Annealing: Iteratively propose random Clifford circuit modifications, accepting those that reduce cost according to annealing schedule [1] [2]

- Validation: Verify that the optimized mapping maintains all fermionic anticommutation relations [2]

This process typically runs for up to 3 days on a single CPU for systems with over 1,500 Hamiltonian terms [2]. The following diagram illustrates this optimization workflow:

SAT-Based Formal Verification

The Fermihedral framework employs a distinct methodological approach:

- Constraint Encoding: Translate fermionic constraints (anticommutivity, algebraic independence) into Boolean expressions [5]

- Cost Integration: Incorporate Hamiltonian implementation cost into the SAT problem [5]

- Clause Reduction: Apply techniques to manage exponential clause growth while maintaining solution quality [5]

- Solver Execution: Utilize high-performance SAT solvers to find the optimal encoding [5]

This approach provides formal guarantees of optimality for feasible problem sizes, with approximation techniques extending its reach to larger systems [5].

Implications for Quantum Simulation in Research

Impact on Practical Applications

The advancements in fermion-to-qubit mapping have direct implications for research applications:

- Quantum Chemistry: For a 6-site hydrogen chain (≈1,500 terms), optimized mappings reduce Pauli weight by 10-20%, directly translating to shallower circuits and improved simulation accuracy on noisy devices [2]

- Materials Science: For Hubbard models relevant to high-temperature superconductivity and catalyst design, 20-25% reductions in Pauli weight significantly enhance simulation feasibility [1] [2]

- Drug Development: More efficient mappings enable larger molecular simulations, potentially improving binding affinity calculations and reaction pathway analysis [5]

Experimental validation on IonQ's ion-trap device demonstrates that optimized encodings significantly increase simulation accuracy compared to conventional approaches [5].

Future Directions

The field continues to evolve along several research vectors:

- Hardware-Aware Mappings: Developing encodings that optimize for specific qubit connectivity and noise characteristics [6]

- Larger-Scale Optimization: Improving heuristic and exact methods to handle systems with thousands of fermionic modes [5]

- Specialized Encodings: Creating mappings optimized for specific computational tasks like Trotterization or variational algorithms [2]

- Machine Learning Approaches: Exploring data-driven techniques for mapping discovery and optimization [7]

The fundamental challenge of bridging fermionic and qubit statistics continues to drive innovation in quantum computation. While theoretical results establish fundamental limits on encoding locality, heuristic optimization methods demonstrate remarkable practical improvements, reducing Pauli weight by 15-40% for specific problem Hamiltonians [1] [2]. The emerging toolkit of Clifford-based optimization, SAT formalization, and efficient fermion routing provides researchers with powerful methods to tailor encodings to their specific systems of interest.

For drug development professionals and research scientists, these advancements translate to tangible benefits: reduced quantum resource requirements, improved simulation accuracy on current hardware, and expanded scope of simulatable systems. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, the co-design of algorithms, encodings, and device architectures promises to further narrow the gap between fermionic systems and their qubit representations, potentially unlocking new frontiers in computational chemistry and materials discovery.

Core Principles of Fermion-to-Qubit Encoding

Quantum simulation of fermionic systems is a leading application of quantum computing, with profound implications for quantum chemistry, materials science, and drug development [8] [9]. Unlike classical bits or distinguishable particles, fermions obey the Pauli exclusion principle and exhibit anticommutation relations. These fundamental properties must be preserved when mapping fermionic systems to qubit-based quantum processors [10] [11]. Fermion-to-qubit encodings provide the mathematical framework for this mapping, transforming fermionic creation ((ci^\dagger)) and annihilation ((ci)) operators into Pauli operators acting on qubits [11].

The need for these encodings stems from a fundamental incompatibility: qubits are distinguishable quantum systems, while fermions are indistinguishable particles with specific exchange statistics. Without proper encoding, the simulated dynamics would not capture the essential quantum behavior of fermionic systems. Research in this field has experienced a renaissance in recent decades, driven by advances in both classical simulation methods and the development of quantum hardware [11]. The choice of encoding significantly impacts simulation performance, affecting circuit depth, qubit count, gate complexity, and error susceptibility [8] [12].

Core Principles and Fundamental Challenges

The Anticommutation Problem

At the heart of fermion-to-qubit mapping lies the challenge of preserving the canonical anticommutation relations. For fermionic operators, these relations are:

[ {ci, cj^\dagger} = \delta{ij}, \quad {ci, cj} = 0, \quad {ci^\dagger, c_j^\dagger} = 0 ]

where ({A, B} = AB + BA) denotes the anticommutator [10]. In qubit space, where operators commute by default, preserving these relations requires careful construction. The most straightforward solution, the Jordan-Wigner transformation, achieves this by introducing non-local string operators whose weight scales with system size [8] [12].

Key Design Trade-offs

The development of fermion-to-qubit encodings involves navigating several fundamental trade-offs:

- Locality vs. Qubit Overhead: Local fermionic interactions should ideally map to local qubit operations. Achieving this often requires additional ancilla qubits, creating a trade-off between circuit complexity and qubit count [9] [12].

- Parallelization vs. Operator Structure: Efficient quantum algorithms require parallel gate execution. However, the structure of encoded operators can restrict which operations can be performed simultaneously [12].

- Code Distance vs. Stabilizer Weight: For error-corrected simulations, increasing the code distance provides better protection but typically increases stabilizer weights, complicating their measurement [13] [11].

These trade-offs have driven the development of diverse encoding strategies, each optimized for different hardware capabilities and simulation targets.

Comparative Analysis of Major Encoding Techniques

Established Encoding Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Major Fermion-to-Qubit Encodings

| Encoding Method | Qubit Overhead | Operator Locality | Parallelization Potential | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner (JW) [8] [12] | 1:1 (minimal) | Non-local in 2D/3D ((O(N)) weight) | Limited by string collisions | Small systems, 1D chains |

| Compact Encoding (CE) [8] | Moderate (ancillas) | Local | High with optimized compilation | 2D Fermi-Hubbard model |

| Bravyi-Kitaev (BK) [12] | 1:1 (minimal) | (O(\log N)) weight | Limited by common qubits | Moderate-sized systems |

| Ladder Encodings (LE) [13] [11] | Varies with distance | Local, tunable distance | High with topological defects | Fault-tolerant simulations |

| High-Distance Stabilizer Codes [9] | Significant | Local, high distance | Architecture-dependent | Error-corrected simulations |

Performance Metrics and Quantitative Comparison

Recent experimental and theoretical studies have provided quantitative comparisons between encoding strategies:

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison for 6×6 Fermi-Hubbard Model

| Encoding Method | Physical Qubits | Gate Reduction | Error Mitigation Efficiency | Experimental Platform |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner | 36 | Baseline (0%) | Limited by global constraints | Trapped ions (Quantinuum H2) |

| Compact Encoding | 48 | 42% with corner hopping | Enhanced with local postselection | Trapped ions (Quantinuum H2) |

| Fermihedral [14] | System-dependent | Substantial reductions reported | Improved simulation accuracy | IonQ devices |

The Compact Encoding demonstrated a 42% reduction in gate cost for simulating fermionic hopping on a square lattice compared to Jordan-Wigner, enabled by a "corner hopping" compilation scheme [8]. This efficiency gain translated to experimental improvements in adiabatic ground state preparation of a spinless Fermi-Hubbard model.

Theoretical Scaling Behavior

Table 3: Asymptotic Scaling of Different Encodings

| Encoding Method | Depth Overhead | Ancilla Requirements | Gate Complexity | Recent Improvements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Jordan-Wigner | (O(N)) | None | (O(N)) per term | - |

| Optimized JW [12] | (O(\log^2 N)) (ancilla-free) | None | (O(\log^2 N)) | Fermionic permutation circuits |

| Ancilla-assisted JW [12] | (O(\log N)) | (O(N)) | (O(\log N)) | Measurement and feedforward |

| Compact Encoding [8] | Constant for 2D local models | Moderate | Constant for local terms | Topological defect embedding |

Recent theoretical breakthroughs have shown that the Jordan-Wigner encoding can achieve (O(\log^2 N)) depth overhead for arbitrary fermionic models without ancillas, exponentially improving the previously believed (O(N)) overhead [12]. This is achieved through sophisticated fermionic swap networks that effectively rearrange the fermionic mode ordering between Trotter steps.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Benchmarking Fermionic Encodings

Experimental validation of fermion-to-qubit encodings requires standardized benchmarking protocols. A representative methodology used in recent studies involves:

Protocol 1: Adiabatic Ground State Preparation [8]

- System Initialization: Prepare the system in a checkerboard product state corresponding to a classical fermionic configuration.

- Adiabatic Evolution: Implement time evolution under the Fermi-Hubbard Hamiltonian with linearly ramped parameters:

- Initial parameters: (Vi = 8.0), (ti = 0)

- Final parameters: (Vf = 2.3), (tf = 1)

- Evolution path: (V(s) = Vi - s(Vi - V_f)), (t(s) = s), where (s \in [0,1])

- Trotter Decomposition: Split evolution into (T) first-order Trotter steps: [ U = U(1)U\left(\frac{T-1}{T}\right) \cdots U\left(\frac{1}{T}\right) ] where (U(s) = U{\text{int}}(s)U{\text{hop}}(s)) separates interaction and hopping terms.

- Observable Measurement: Measure local fermionic observables and compare with classical benchmarks.

This protocol was used to demonstrate the superiority of Compact Encoding over Jordan-Wigner for a 6×6 Fermi-Hubbard model on a trapped-ion quantum computer [8].

Error Mitigation Techniques

Specialized error mitigation methods have been developed for fermionic encodings:

Local Postselection: Leverages conserved quantities (stabilizers) inherent to certain encodings to identify and discard erroneous measurement outcomes while retaining more data than global postselection [8].

Observable Extrapolation: Extrapolates local observables based on their sensitivity to errors, particularly effective in encodings where local fermionic operators map to local qubit operators [8].

Compilation Optimization Strategies

Advanced compilation techniques significantly impact encoding performance:

Corner Hopping: A compilation scheme specific to the Compact Encoding that reduces the gate cost of simulating fermionic hopping on a square lattice by 42% by optimizing the order of fermionic operations [8].

Fermihedral Framework: A compiler that reformulates fermion-to-qubit encoding as a Boolean satisfiability problem, discovering optimal encodings for specific Hamiltonians that substantially reduce implementation costs, gate counts, and circuit depth [14].

Fermionic Permutation Circuits: A recent technique that achieves (O(\log^2 N)) depth overhead in Jordan-Wigner encoding by implementing arbitrary fermionic permutations between Trotter layers [12].

Advanced Encoding Frameworks and Future Directions

High-Distance and Fault-Tolerant Encodings

Recent research has developed encoding families with arbitrarily scalable code distances:

Ladder Encodings (LE): A family of one-dimensional encodings that can be embedded into surface codes with topological defects, allowing systematic increase of code distance without growing stabilizer weights [13] [11].

Perforated Encodings: Encode two fermionic spin modes within the same surface code structure, optimizing for fermionic Hamiltonians with spin degrees of freedom [11].

3D High-Distance Codes: The first constructions simultaneously achieving high distance, constant stabilizer weights, and locality preservation for 3D fermionic systems [9].

These encoding families bridge the gap between near-term noisy quantum simulations and fully fault-tolerant quantum computation by providing a smooth path toward error-corrected fermionic simulation.

Fermion-Qubit Fault-Tolerant Computing

A emerging paradigm combines native fermionic operations with qubit-based error correction:

Fermionic Repetition Codes: Correct phase errors using native fermionic operations before mapping to qubits [15].

Fermionic Color Codes: Extend protection to both phase and loss errors while maintaining a universal fermionic gate set [15].

Qubit-Fermion Interfaces: Enable qubit-controlled fermionic operations, crucial for advanced quantum algorithms while maintaining the efficiency of native fermionic operations [15].

This approach demonstrates exponential improvements for key subroutines like the fermionic fast Fourier transform, reducing circuit depth from (O(N)) to (O(\log N)) [15].

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Fermionic Encoding Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fermihedral [14] | Compiler Framework | Discovers optimal encodings via Boolean satisfiability | Customized encoding for specific Hamiltonians |

| Surface Code Patches [13] [11] | Quantum Hardware Primitive | Provides topological protection for encoded fermions | Fault-tolerant fermionic simulation |

| Trapped-Ion Quantum Computers [8] | Experimental Platform | High-fidelity gate operations for encoding validation | Experimental benchmarking of encodings |

| fSWAP Networks [12] | Circuit Compilation Technique | Implements fermionic permutations with low overhead | Depth optimization for Jordan-Wigner |

| Corner Hopping [8] | Compilation Scheme | Reduces gate cost for 2D hopping terms | Compact Encoding optimization |

| Edge-Vertex Formalism [11] | Mathematical Framework | Intermediate representation between Dirac and Majorana operators | Encoding design and analysis |

The field of fermion-to-qubit encodings has progressed from fundamental mappings to sophisticated, optimized frameworks that preserve fermionic statistics while minimizing quantum resource overhead. The choice of encoding significantly impacts simulation performance, with different encodings optimizing for distinct hardware capabilities and simulation targets.

Recent advances demonstrate promising directions: exponentially reduced overhead through advanced compilation techniques, encoding families with scalable code distances for fault tolerance, and hybrid approaches that leverage native fermionic operations where available. As quantum hardware continues to advance, the development of specialized encodings tailored to specific physical systems and hardware architectures will play a crucial role in enabling practical quantum simulations of fermionic systems for drug development and materials discovery.

The optimal encoding choice remains context-dependent, balancing factors including target Hamiltonian structure, available qubit count, gate fidelities, and error correction capabilities. Future research will likely focus on adaptive encodings that optimize this balance for specific applications and hardware platforms.

Quantum simulation of fermionic systems is a cornerstone application of quantum computing, spanning the fields of quantum chemistry, condensed matter physics, and high-energy physics [16] [17]. Since quantum computers inherently operate on qubits, representing fermionic systems requires a mathematical transformation that maps fermionic creation and annihilation operators to Pauli operators acting on qubits [18]. This translation is highly non-trivial due to the need to preserve the fundamental anticommutation relations of fermionic operators, which ensures the antisymmetry of the fermionic wavefunction in accordance with the Pauli exclusion principle [18] [19].

The development of efficient fermion-to-qubit mappings represents an active area of research, balancing the competing demands of qubit count, gate complexity, and operator locality [17]. The two most fundamental transformations in this domain are the Jordan-Wigner transformation (JWT) and the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation (BKT), which form the foundation for more advanced mapping techniques [16] [18]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these foundational approaches, examining their mathematical formulations, resource requirements, and performance characteristics to inform researchers and development professionals working at the intersection of quantum computation and molecular simulation.

Mathematical Foundations

Jordan-Wigner Transformation

The Jordan-Wigner transformation (JWT) provides an intuitive approach to mapping fermionic operators to qubit operators by directly storing the occupation number of each fermionic mode in a corresponding qubit [18] [19]. Under this transformation, the fermionic annihilation and creation operators are mapped to qubit operators as follows:

[ap \mapsto \frac{1}{2} (Xp + iYp) \otimes{k

k \quad \text{and} \quad ap^\dagger \mapsto \frac{1}{2} (Xp - iYp) \otimes{k k]

where (Xp), (Yp), and (Zp) are Pauli operators acting on qubit (p) [19]. The key feature of this mapping is the string of (Z) operators (\otimes{k

[18].="" [19].

}>The JWT establishes a direct correspondence between fermionic basis states and computational basis states of the qubits, where the fermionic state (|n0, n1, ..., n{N-1}\rangle) is represented by the computational basis state (|z0, z1, ..., z{N-1}\rangle) with (zp = np) for all (p) [19]. While conceptually straightforward, this mapping results in non-local qubit operators, with the Pauli weight (number of non-identity Pauli operators in a term) of a single fermionic operator scaling as (O(N)) for a system with (N) modes [17] [19].

Bravyi-Kitaev Transformation

The Bravyi-Kitaev transformation (BKT) represents a more sophisticated approach that stores fermionic information non-locally across qubits to achieve better asymptotic scaling [17] [20]. In this mapping, even-labeled qubits store the occupation number of orbitals, while odd-labeled qubits store the parity of preceding orbitals through partial sums of occupation numbers [18]. This hybrid scheme results in a more efficient representation where the Pauli weight of a single fermionic operator scales as (O(\log N)), offering significant advantages for larger systems [20].

The Bravyi-Kitaev transformation defines creation and annihilation operators with a combination of Pauli (X), (Y), and (Z) operators that depends on the binary representation of the mode index [18]. For a given mode (j), the transformation involves:

- Update set: Qubits whose occupation number needs to be updated when a fermion is created or annihilated at mode (j)

- Parity set: Qubits whose parity determines the phase factor when acting on mode (j)

- Flip set: Qubits that need to be flipped when the occupation of mode (j) changes [20]

The mathematical formulation of the BKT is more complex than the JWT, but it substantially reduces the locality of the resulting qubit operators, particularly for systems with a large number of modes [18] [20].

Performance Comparison

Theoretical and Empirical Resource Requirements

The theoretical scaling differences between the JWT and BKT translate to concrete practical implications for quantum simulation. Empirical studies across diverse molecular systems confirm the superior efficiency of the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation in terms of gate counts and operator weights [16] [20].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Performance Metrics

| Metric | Jordan-Wigner Transformation | Bravyi-Kitaev Transformation |

|---|---|---|

| Qubit count | (N) (minimum required) [17] | (N) (minimum required) [17] |

| Pauli weight of single operator | (O(N)) [17] [19] | (O(\log N)) [17] [20] |

| Gate count for single fermionic operation | (O(N)) [20] | (O(\log N)) [20] |

| Typical gate count reduction | Reference | ~50% or more for larger systems [16] |

| Experimental realization complexity | Higher due to long Pauli strings [18] | Lower due to more local operators [18] |

A comprehensive study comparing these transformations across 86 molecular systems demonstrated that the BKT is typically at least as efficient as the canonical JWT, with substantially reduced gate counts when performing limited circuit optimizations [16]. For the specific case of molecular hydrogen in a minimal basis, the quantum circuit for simulating a single Trotter time-step of the BKT-derived Hamiltonian required fewer gate applications than the equivalent circuit derived from the JWT [20].

Table 2: Empirical Data from Comparative Studies

| System Characteristics | Jordan-Wigner Gate Count | Bravyi-Kitaev Gate Count | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ in minimal basis | Reference value | Lower than JWT [20] | Significant [20] |

| Small molecules (near-term devices) | High | Moderate [16] | Approximately 50% or better [16] |

| Large systems (classically intractable) | Prohibitively high | Substantially lower [16] | Increases with system size [16] |

Parity-Based Mapping as an Intermediate Approach

It is worth noting the parity mapping as an alternative approach that stores the parity of orbitals instead of occupation numbers [18]. In this scheme, the (j)-th qubit stores the parity (sum modulo 2 of occupation numbers) of all orbitals up to (j) [18]. While this approach doesn't improve the (O(N)) scaling of operator weights, it enables the tapering off of two qubits by leveraging symmetries in molecular Hamiltonians, effectively reducing the qubit count required for simulation [18].

The transformation rules for the parity mapping are given by:

[aj^\dagger = \frac{1}{2}(Z{j-1} \otimes Xj - iYj) \otimes{k>j} Xk \quad \text{and} \quad aj = \frac{1}{2}(Z{j-1} \otimes Xj + iYj) \otimes{k>j} Xk]

where the long (Z) strings of the JWT are replaced by (X) strings [18]. Although this doesn't improve locality, the ability to remove two qubits through symmetry arguments makes the parity mapping practically useful for near-term quantum simulations where qubit count is severely constrained [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Comparative Analysis Framework

Rigorous comparison of fermion-to-qubit mapping techniques requires a standardized experimental framework. The methodology employed in foundational studies typically involves multiple steps from Hamiltonian generation to resource quantification [16] [18]:

Molecular System Selection: Studies typically examine a diverse set of molecular systems spanning different geometries and electron counts. For example, the comprehensive analysis by Tranter et al. evaluated 86 molecular systems to ensure statistical significance [16].

Hamiltonian Generation: The electronic structure problem is first solved classically to obtain the second-quantized fermionic Hamiltonian in the form:

[H = \sum{pq} h{pq} ap^\dagger aq + \frac{1}{2} \sum{pqrs} h{pqrs} ap^\dagger aq^\dagger ar as]

where (h{pq}) and (h{pqrs}) are one- and two-electron integrals computed in a chosen basis set [16] [18].

Qubit Hamiltonian Generation: The fermionic Hamiltonian is mapped to a qubit Hamiltonian using each transformation technique (JWT, BKT, etc.). This involves substituting each fermionic operator with its qubit representation [18].

Circuit Construction: Quantum circuits for time evolution or ground state estimation are constructed using approaches such as Trotter-Suzuki decomposition or variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) ansatze [18].

Resource Quantification: The number of quantum gates (particularly non-Clifford gates like T gates), total Pauli weight, circuit depth, and qubit count are measured for each mapping [16] [18].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for comparing fermion-to-qubit mapping techniques

Key Experimental Considerations

When designing experiments to evaluate mapping techniques, researchers should control for several critical factors:

Basis set selection: The choice of molecular orbital basis significantly impacts the efficiency of quantum simulation. Common approaches include minimal basis sets (STO-3G) for initial testing and larger basis sets for more accurate results [16] [18].

Active space selection: For larger molecules, restricting the simulation to an active space of chemically relevant orbitals reduces computational requirements while maintaining accuracy [16].

Term ordering: The order in which fermionic modes are assigned to qubits can impact the efficiency of both JWT and BKT. Recent research has framed optimal ordering as a quadratic assignment problem to minimize Pauli weights [17].

Measurement strategies: The choice of mapping affects the measurement overhead for variational algorithms, as different mappings produce Hamiltonians with varying numbers of Pauli terms and weights [16].

Implementation and Practical Guidance

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum SDKs | PennyLane [18], OpenFermion [19] | Provides built-in functions for applying JWT, BKT, and other mappings to fermionic operators |

| Electronic Structure Packages | PySCF, Psi4, OpenMolcas | Compute one- and two-electron integrals for molecular Hamiltonians |

| Visualization Tools | Custom DOT scripts (Graphviz) | Diagram transformation workflows and operator relationships |

| Classical Simulators | Qiskit Aer, PennyLane DefaultQubit | Test and validate quantum circuits before hardware deployment |

| Resource Estimation Tools | Custom scripts, Qiskit ResourceEstimator | Quantify gate counts, qubit requirements, and circuit depth |

Implementation Workflow

The practical implementation of fermion-to-qubit mappings follows a systematic process that can be implemented across various software frameworks. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and decision points when selecting and applying these transformations:

Diagram 2: Implementation decision workflow for selecting mapping techniques

Code Examples

Practical implementation of these transformations is facilitated by modern quantum software development kits. The following examples illustrate basic usage:

Jordan-Wigner in PennyLane:

Bravyi-Kitaev in PennyLane:

Jordan-Wigner in OpenFermion:

The dramatic reduction in operator complexity between JWT and BKT is evident even in these simple examples, with the BKT version involving fewer qubits and more localized operations [18].

The comparative analysis of Jordan-Wigner and Bravyi-Kitaev transformations reveals a fundamental trade-off between conceptual simplicity and operational efficiency in fermion-to-qubit mappings. While the Jordan-Wigner transformation offers an intuitive approach that directly mirrors the occupation number basis, its (O(N)) scaling of operator weights presents significant practical limitations for quantum simulation of all but the smallest molecular systems.

The Bravyi-Kitaev transformation, with its (O(\log N)) scaling, provides a theoretically superior approach that substantially reduces gate counts and improves locality [16] [20]. Empirical studies across diverse molecular systems confirm that BKT typically outperforms JWT, particularly as system size increases toward classically intractable regimes [16].

For researchers and development professionals implementing quantum simulations of fermionic systems, the choice of mapping technique depends critically on the target system size, available quantum hardware, and specific application requirements. Small-scale simulations may benefit from the conceptual clarity of JWT, while larger systems will increasingly require the efficiency of BKT. Emerging techniques that optimize over fermionic orderings or incorporate limited numbers of ancilla qubits promise further improvements, potentially offering a favorable balance between qubit count and gate complexity for the constrained quantum devices of the near future [17].

The Critical Role of Pauli Operators and Strings in Hamiltonian Representation

In the pursuit of simulating quantum systems on quantum computers, the representation of fermionic Hamiltonians using Pauli operators emerges as both a fundamental necessity and a significant bottleneck. When simulating electrons in molecules or materials, the fermionic creation and annihilation operators that naturally describe these systems must be translated into operations that quantum hardware can understand—specifically, tensor products of Pauli operators (X, Y, Z) and the identity. These tensor products, known as Pauli strings, carry the algebraic structure of fermionic anticommutation relations but introduce substantial computational overhead through their non-locality.

The length of these Pauli strings, often referred to as their Pauli weight, directly determines the complexity of quantum circuits required for simulation. Higher-weight terms require more complex entangling operations and deeper circuits, which is particularly problematic for today's noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. This challenge has catalyzed the development of various fermion-to-qubit mapping techniques, each attempting to balance circuit depth, qubit count, and architectural constraints while faithfully preserving the underlying fermionic physics. This article provides a comparative analysis of these mapping techniques, examining their theoretical foundations, practical performance, and suitability for different applications in quantum chemistry and materials science.

Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Techniques: A Comparative Framework

Multiple mapping strategies have been developed to transform fermionic Hamiltonians into qubit representations, each with distinct trade-offs between Pauli weight, qubit requirements, and implementation complexity. The three most established techniques—Jordan-Wigner, Parity, and Bravyi-Kitaev—form the core of this comparison, alongside newer optimized approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Techniques

| Mapping Technique | Key Principle | Typical Pauli Weight | Qubit Requirements | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner | Maps occupation number directly to qubit state; uses Z-strings to track parity | O(N) [12] [18] | N qubits for N modes | Simple, intuitive implementation; minimal qubit count [18] | High Pauli weight; non-local interactions [18] |

| Parity | Stores parity information locally in qubit state | O(N) [18] | N qubits for N modes | Simplifies parity constraints; enables qubit tapering [18] | Still requires long operator strings (X-strings instead of Z-strings) [18] |

| Bravyi-Kitaev | Hybrid approach storing both occupation and parity information non-locally | O(log N) [12] | N qubits for N modes | Lower asymptotic Pauli weight; more local interactions [18] | More complex transformation logic [18] |

| Optimal Enumeration | Optimizes fermionic mode ordering to minimize string length | 13.9-37.9% reduction vs. standard JW [21] | N qubits (or N+2 with ancillas) | Significant improvement without ancilla qubits; polynomial reductions possible [21] | Optimization problem dependent on lattice geometry [21] |

| Slater Determinant Mapping | Maps entire Slater determinants to individual qubits | Lower circuit depth but higher qubit count [22] | Scales with number of important determinants [22] | Simpler circuits; NISQ-compatible; demonstrated for 22-29 qubit systems [22] | Exponential qubit scaling in worst case [22] |

The following workflow illustrates how these different mapping approaches transform fermionic operators into qubit representations:

Diagram 1: Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Workflow. This diagram illustrates how different mapping techniques transform fermionic operators into Pauli string representations with varying Pauli weights.

Technical Deep Dive: Mapping Methodologies

The Jordan-Wigner transformation establishes a direct correspondence between fermionic occupation states and computational basis states of qubits. It represents fermionic creation and annihilation operators as:

[

a{j}^{\dagger} = \frac{1}{2}(Xj - iYj) \otimes{k

The Bravyi-Kitaev transformation employs a more sophisticated approach that stores both parity and occupation information in a non-local pattern across qubits. This mapping uses a binary tree structure to encode relationships between fermionic modes, resulting in Pauli strings of logarithmic length—a significant asymptotic improvement [12] [18]. For example, in this mapping, a creation operator might be represented as: [ a{5}^{\dagger} = \frac{1}{2}(Z4 \otimes Z3 \otimes X5 \otimes X{7}) - \frac{i}{2}(Z3 \otimes Y5 \otimes X{7}) ] which demonstrates the reduced locality compared to Jordan-Wigner [18].

Optimal enumeration techniques represent a different approach, focusing not on changing the fundamental mapping but on optimizing the ordering of fermionic modes to minimize Pauli weight. For square lattice systems, Mitchison and Durbin's enumeration pattern can reduce the average Pauli weight of Hamiltonian terms by 13.9% compared to standard Jordan-Wigner, and with two ancilla qubits, reductions of 37.9% are achievable [21].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Benchmarks

Nuclear Shell Model Case Study

A 2025 study implemented a novel Slater determinant (SD) mapping approach for nuclear shell model calculations, where each qubit represents an entire Slater determinant rather than individual single-particle states [22]. This method traded increased qubit count for significantly reduced circuit depth, making it particularly suitable for NISQ devices.

Table 2: Experimental Results for SD Mapping on Nuclear Systems [22]

| Nucleus | Qubit Count | Circuit Depth | Error (Before Mitigation) | Error (After ZNE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| â¶Li | 4 | Shallow | Not reported | < 4% |

| â·Li | 6 | Shallow | Not reported | < 4% |

| â¸Li | 6 | Shallow | Not reported | < 4% |

| â¹Li | 8 | Shallow | Not reported | < 4% |

| ¹â¸F | 13 | Shallow | Not reported | < 4% |

| ²¹â°Po | 22 | Shallow | Not reported | < 4% |

| ²¹â°Pb | 29 | Shallow | Not reported | < 4% |

Experimental Protocol: The research employed the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm with the following methodology [22]:

- Hamiltonian Encoding: Nuclear shell model Hamiltonians were encoded using the SD mapping approach

- Circuit Implementation: Quantum circuits were designed with minimal depth compared to traditional mappings

- Hardware Execution: Circuits were run on IBM's

ibm_pittsburghprocessor and noisy simulator (FakeFez backend) - Error Mitigation: Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) via two-qubit gate folding was applied to mitigate errors

- Validation: Results were compared to classical shell model predictions for accuracy assessment

The study demonstrated that despite increased qubit requirements (up to 29 qubits for heavier nuclei), the reduced circuit complexity enabled successful implementation on current hardware with less than 4% deviation from theoretical predictions after error mitigation [22].

Advanced Algorithmic Approaches

Recent theoretical work has dramatically improved the asymptotic overhead of fermionic simulation. A 2025 breakthrough demonstrated that fermionic permutations in the Jordan-Wigner encoding can be implemented in circuit depth O(log²N) without ancillas, exponentially improving the previous O(N) overhead [12]. With O(N) ancillas and mid-circuit measurement, this can be further reduced to O(logN) depth [12].

Experimental Implications: These algorithmic advances enable more efficient implementation of key quantum chemistry subroutines. For example, the fermionic fast Fourier transform (FFFT) can now be implemented with:

- O(log²N) depth overhead without ancillas (exponential improvement)

- O(1) depth overhead with ancillas [12]

This has profound implications for simulating quantum chemistry Hamiltonians in the plane-wave basis, where a single Trotter step can now be implemented in polylog depth with O~(N) qubits [12].

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Solutions for Mapping Experiments

| Tool/Resource | Function | Example Applications | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner Transform | Maps fermionic operators to Pauli strings with Z-based parity tracking | Small systems; pedagogical applications; 1D chains [18] | Linear Pauli weight; suitable for systems with natural 1D ordering |

| Bravyi-Kitaev Transform | Reduces Pauli weight via hybrid occupation/parity encoding | Medium-sized molecules; NISQ applications [18] | Logarithmic Pauli weight; more complex implementation |

| Optimal Enumeration Algorithms | Minimizes Pauli weight through mode ordering optimization | Lattice systems; material science simulations [21] | Geometry-dependent; can reduce weight by 13.9-37.9% |

| Slater Determinant Mapping | Maps configurations rather than individual states | Nuclear physics; systems with manageable determinant spaces [22] | Trading qubit count for circuit depth; NISQ-compatible |

| Joint Measurement Strategies | Efficiently estimates fermionic observables | Quantum chemistry Hamiltonians; variational algorithms [23] | Reduces measurement overhead; compatible with error mitigation |

| fSWAP Networks | Enables efficient fermionic permutation | Fully connected models; all-to-all interactions [12] | O(log²N) depth for arbitrary permutations |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of fermion-to-qubit mapping is rapidly evolving, with several promising research directions emerging. Measurement strategies tailored specifically for fermionic observables are achieving reduced measurement overhead, with one recent approach estimating all quadratic and quartic Majorana terms using only O(N²log(N)/ε²) measurement rounds [23]. When implemented on rectangular qubit lattices, this strategy requires only O(N¹á§âµ) two-qubit gates and O(√N) depth, substantially improving on previous approaches [23].

The Hamiltonian simulation-based quantum-selected configuration interaction (HSB-QSCI) method represents another innovative approach, sampling important Slater determinants from quantum states generated by real-time evolution rather than variational optimization [24]. This technique has demonstrated remarkable efficiency, capturing over 99.18% of correlation energies while considering only about 1% of all Slater determinants in 36-qubit systems [24].

These advances, combined with new theoretical insights about the fundamental overhead of fermionic simulation, suggest that we are approaching a threshold where quantum computers can meaningfully outperform classical methods for specific fermionic simulation problems. The optimal choice of mapping technique increasingly depends on the specific problem structure, available hardware, and target precision, necessitating careful comparative analysis for each application domain.

The critical role of Pauli operators and strings in Hamiltonian representation underscores a fundamental challenge in quantum simulation: bridging the gap between fermionic physics and qubit-based computation. Our comparative analysis reveals that no single mapping technique dominates across all applications; rather, researchers must strategically select approaches based on their specific requirements.

For NISQ-era applications with limited qubit counts and significant noise constraints, the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation offers a balanced compromise between qubit efficiency and Pauli weight reduction. When simulating specific lattice geometries, optimal enumeration techniques provide significant improvements without additional qubit overhead. For problems where the important Hilbert space sector is manageable, the Slater determinant mapping approach demonstrates promising results by trading qubit count for circuit depth.

As quantum hardware continues to evolve, the interplay between algorithmic advances and device capabilities will likely yield further innovations in fermion-to-qubit mapping. The exponential reductions in overhead recently demonstrated theoretically [12] suggest that even more efficient representations may be forthcoming, potentially enabling practical quantum advantage for fermionic simulation in the near future.

Fermion-to-qubit mappings are foundational to quantum simulation, enabling the study of molecular and materials science on quantum computers. These mappings translate the anti-commuting operators of fermionic systems into the Pauli operators of qubits. The efficiency of this translation directly impacts the feasibility of quantum simulations. This guide provides a comparative analysis of mapping techniques, focusing on three critical properties: locality (how non-local the resulting qubit operators are), qubit count (the number of physical qubits required), and circuit complexity (the depth and number of gates needed for simulation). The optimal choice of mapping is not universal but depends on the specific fermionic Hamiltonian and the constraints of the target quantum hardware.

Comparative Analysis of Mapping Techniques

The following tables summarize the key characteristics and performance metrics of major fermion-to-qubit mappings.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Fermion-to-Qubit Mappings

| Mapping Name | Type | Key Idea | Locality (Pauli Weight) | Qubit Count | Ancilla Qubits Required? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner (JW) [12] [10] | Non-local | Encodes modes along a 1D chain with non-local parity strings. | $O(N)$ [12] | $N$ [10] | No |

| Bravyi-Kitaev (BK) [12] [25] | Non-local | Uses a binary tree structure to reduce operator weight. | $O(\log N)$ [12] | $N$ [25] | No |

| Ternary Tree [25] | Non-local | Uses a ternary tree structure for optimal Pauli weight. | $\lceil \log_3(2n+1)\rceil$ [25] | $N$ | No |

| Ancilla-Assisted Local [12] [26] | Local | Uses auxiliary qubits to store parity information, removing non-local strings. | $O(1)$ (constant) [26] | $>N$ [12] | Yes ($O(N)$) [12] |

| Qudit-Based [26] | Local | Uses multi-level quantum systems (qudits) to internalize parity information. | Fully local [26] | Fewer physical systems (but higher-dimensional) [26] | No (encoded in levels) |

| Hybrid [27] | Hybrid | Parametrized family that interpolates between JW and BK properties. | Intermediate | $N$ [27] | No |

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Key Simulation Tasks

| Mapping / Property | Theoretical Worst-Case Depth Overhead (vs. Fermionic Computer) | Performance in Specific Models | Key Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner (JW) | $O(N)$ [12] | Poor parallelization for non-1D models [12]. | Simple but suffers from non-locality; no ancilla cost. |

| Bravyi-Kitaev (BK) | $O(N)$ (due to parallelization issues) [12] | Better gate count than JW for some models, but similar depth overhead [12]. | Reduced weight per operator, but limited parallelization. |

| Ancilla-Assisted | $O(1)$ for geometrically local models [12] | Enables constant-depth simulation of geometrically local interactions [12]. | Exchanges circuit depth for a linear space (qubit) overhead. |

| Advanced JW (with fSWAP) | $O(\log^2 N)$ (ancilla-free) [12] | Enables Fermionic Fast Fourier Transform in $O(\log^2 N)$ depth [12]. | Maintains low qubit count while exponentially improving depth. |

| Heuristically Optimized | Varies (tailored to Hamiltonian) | 15-40% improvement in average Pauli weight for intermediate Hamiltonians [1]. | Offers custom performance but requires an optimization step. |

Experimental Protocols for Mapping Evaluation

To objectively compare mappings, researchers employ standardized evaluation protocols focusing on concrete metrics.

Protocol 1: Average Pauli Weight Measurement

This protocol quantifies the locality of a mapping by measuring the average number of qubits on which the mapped Hamiltonian terms act.

- Input: A target fermionic Hamiltonian, ( H = \sum\alpha h\alpha P\alpha ), where ( P\alpha ) are fermionic terms.

- Mapping: Apply the fermion-to-qubit mapping ( \mathcal{E} ) to transform each ( P\alpha ) into a Pauli string ( \mathcal{E}(P\alpha) ) on qubits.

- Measurement: For each Pauli string ( \mathcal{E}(P_\alpha) ), calculate its weight (number of non-identity Pauli operators).

- Calculation: Compute the average Pauli weight across all terms, ( \frac{1}{L} \sum{\alpha=1}^L \text{weight}(\mathcal{E}(P\alpha)) ), where ( L ) is the total number of terms.

- Output: A single number representing the average Pauli weight. A lower value indicates better locality [1].

Protocol 2: Trotterized Time Evolution Gate Count

This protocol evaluates the practical circuit complexity of implementing a time-evolution step for a specific model.

- System Selection: Choose a benchmark model (e.g., the 2D Fermi-Hubbard model on an ( N \times N ) lattice).

- Trotterization: Decompose the time-evolution operator ( e^{-iHt} ) into a product of exponentials of individual Hamiltonian terms (a Trotter step).

- Circuit Compilation: For each mapping, compile the circuit for a single Trotter step.

- Metric Collection: Tally the total number of two-qubit gates (typically the most expensive operations) and the overall circuit depth.

- Comparison: Compare the gate counts and depths across different mappings for the same model and lattice size [26] [27].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for evaluating and comparing fermion-to-qubit mappings, from Hamiltonian input to performance metrics.

Visualization of Mapping Relationships and Trade-offs

The landscape of fermion-to-qubit mappings can be understood as a spectrum trading off qubit count against circuit complexity (locality).

Figure 2: A conceptual map showing the relationships and evolution between different families of fermion-to-qubit mappings.

Table 3: Key "Research Reagent" Solutions for Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Studies

| Tool / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| ZX-Calculus Framework [28] | A graphical language to unify and reason about different mappings, proving equivalences. | Translating a ternary tree mapping into an encoder circuit. |

| Heuristic Numerical Optimizer [1] | An algorithm (e.g., simulated annealing) to find low-Pauli-weight mappings for a specific Hamiltonian. | Designing a custom mapping for a complex molecular Hamiltonian. |

| Fermionic SWAP (fSWAP) Gate [12] [26] | A gate that exchanges the states of two fermionic modes while preserving anti-symmetry. | Routing fermions in the JW encoding to improve operator locality in a circuit. |

| Stabilizer Formalism [10] | A method to describe and work with the constraints of local fermion-to-qubit encodings. | Identifying and enforcing the gauge constraints in an ancilla-assisted mapping. |

| Ternary Tree Data Structure [25] | An optimal tree structure for constructing mappings with minimal Pauli weight. | Implementing a mapping for efficiently learning k-fermion reduced density matrices. |

The choice of a fermion-to-qubit mapping is a critical decision that balances the competing resources of a quantum computer. Non-local mappings like Jordan-Wigner are simple and ancilla-free but incur high circuit depth overhead. Ancilla-assisted local mappings solve the locality problem, enabling constant-depth simulation for local Hamiltonians, at the cost of a larger qubit footprint. Hybrid and heuristically optimized mappings offer a middle ground, tailoring the encoding to the problem.

Current research demonstrates that significant improvements are possible. Advanced compilation of the Jordan-Wigner encoding with fSWAP networks can exponentially reduce its worst-case overhead [12], while qudit-based approaches present a novel path to full locality without ancillas [26]. There is no single "best" mapping; the optimal choice is dictated by the problem Hamiltonian, the available number of qubits, and the error budget of the hardware. Future work will likely involve further hybridization and hardware-aware co-design to push the boundaries of feasible quantum simulation.

Advanced Encoding Frameworks: From Ternary Trees to SAT Solvers and Real-World Pipelines

Simulating fermionic systems is a cornerstone application of quantum computing, with profound implications for quantum chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery. However, quantum computers operate on qubits, not fermions, necessitating a critical translation step known as fermion-to-qubit mapping. The efficiency of this mapping directly determines the feasibility and resource requirements of quantum simulations. Traditional mappings like Jordan-Wigner (JW) and Bravyi-Kitaev (BK) have provided foundational approaches but incur significant overheads, particularly for large systems. The Hamiltonian-Adaptive Ternary Tree (HATT) framework represents a targeted optimization approach that generates fermion-to-qubit mappings specifically adapted to the problem Hamiltonian, achieving substantial reductions in simulation overhead.

This comparative analysis examines the HATT framework against alternative state-of-the-art mapping techniques, evaluating their performance characteristics, resource requirements, and implementation considerations. We present quantitative experimental data and detailed methodologies to provide researchers with a comprehensive understanding of the current landscape in fermion-to-qubit mapping optimization.

The HATT Framework: Core Architecture and Methodology

Conceptual Foundation and Algorithmic Structure

The Hamiltonian-Adaptive Ternary Tree (HATT) framework introduces a systematic approach for compiling optimized fermion-to-qubit mappings tailored to specific fermionic Hamiltonians. Unlike static mappings that apply uniformly to all problems, HATT utilizes a ternary tree structure and a bottom-up construction procedure to generate Hamiltonian-aware mappings that minimize the Pauli weight of the resulting qubit Hamiltonian [29]. This reduction in Pauli weight directly translates to lower quantum simulation circuit overhead, a critical bottleneck in near-term quantum devices.

The framework operates through several key mechanisms. First, it analyzes the specific interaction terms within the target fermionic Hamiltonian. Using this structural information, it constructs a ternary tree mapping that minimizes the non-locality of the resulting qubit operators. Importantly, HATT retains the vacuum state preservation property essential for physical simulations while reducing algorithmic complexity from O(Nâ´) to O(N³) through optimized implementation [29]. This balance of performance and correctness makes it particularly valuable for practical quantum simulations.

Experimental Protocol and Implementation Details

Implementing HATT for comparative analysis involves a structured workflow:

Hamiltonian Analysis: The target fermionic Hamiltonian is decomposed into its constituent interaction terms, identifying the connectivity pattern between fermionic modes.

Tree Construction: A ternary tree structure is built from the bottom up, with fermionic modes positioned to minimize the distance between interacting modes in the mapping.

Mapping Generation: The framework generates the complete fermion-to-qubit mapping by traversing the optimized tree structure and applying the transformation rules.

Circuit Compilation: The resulting qubit Hamiltonian is compiled into quantum gates using standard compilation techniques, with circuit depth and gate count recorded for comparison.

Validation: The mapping is validated by verifying preservation of anti-commutation relations and vacuum state properties.

Evaluation experiments typically involve applying this protocol to benchmark Hamiltonians from quantum chemistry and condensed matter physics, with performance metrics compared against alternative mappings under controlled conditions.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The following tables summarize comprehensive performance comparisons between HATT and alternative fermion-to-qubit mapping approaches across multiple benchmark problems and system sizes.

Table 1: Circuit Overhead Comparison for Different Fermion-to-Qubit Mappings

| Mapping Approach | Ancilla Qubits | Worst-case Depth Overhead | Average Pauli Weight Reduction | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HATT Framework [29] | 0 | O(N³) algorithmic complexity | 5-20% | Hamiltonian-specific optimization required |

| Jordan-Wigner [12] | 0 | O(N) | Baseline | High non-locality for non-linear geometries |

| Bravyi-Kitaev [12] | 0 | O(N) | Moderate improvement | Limited parallelization due to common qubits |

| Log-overhead Ancilla Scheme [12] | O(N) | O(log²N) without ancillas, O(logN) with ancillas | Not specified | High qubit overhead |

| Dynamic Encoding [30] | O(N) | O(logN) | Not specified | Requires mid-circuit measurement and feedforward |

| Qudit Mapping [26] | 0 (uses qudits) | Varies with architecture | Significant for specific systems | Requires qudit hardware |

Table 2: Application-Specific Performance Metrics for N-mode Systems

| Application Domain | HATT Performance | Best Alternative | Performance Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Fermionic Systems [29] | 5-20% reduction in Pauli weight, gate count, and circuit depth | BK: Moderate improvement | Significant for structured Hamiltonians |

| Fermionic Fast Fourier Transform [12] | Not specified | Log-overhead: O(log²N) without ancillas, O(1) with ancillas | HATT not specialized for FFFT |

| Geometrically Local Models [12] | Not specified | Ancilla-based: O(1) overhead | Specialized approaches superior for specific geometries |

| Noise Resistance [29] | Excellent demonstrated on IonQ quantum computer | Varies by implementation | Competitive noise resilience |

Resource Requirement Analysis

The practical implementation of fermion-to-qubit mappings requires careful consideration of resource constraints, particularly for near-term devices with limited qubit counts and coherence times.

Qubit Overhead: HATT requires zero ancilla qubits, operating within the same qubit count as Jordan-Wigner (N qubits for N modes) [29]. This provides a significant advantage over ancilla-based approaches that require O(N) additional qubits [12] [30], which may be prohibitive for early fault-tolerant devices where qubit count is often more expensive than circuit depth due to exponential error suppression [12].

Gate Complexity: Evaluations demonstrate that HATT reduces gate counts by 5-20% compared to standard mappings [29]. While this improvement is modest compared to the asymptotic advantages of recently proposed logarithmic-overhead schemes [12], it provides consistent benefits across various fermionic systems without introducing algorithmic complexity or specialized hardware requirements.

Scalability: HATT demonstrates excellent scalability to larger systems [29], making it suitable for problems of practical interest in drug development and materials science. The O(N³) algorithmic complexity represents a significant reduction from the original O(Nâ´) implementation while remaining higher than the O(N log N) gate complexity of the most advanced dynamic encoding schemes [30].

Alternative Mapping Approaches

Asymptotically Superior Schemes

Recent breakthroughs have demonstrated fermion-to-qubit mappings with exponentially better asymptotic overhead than traditional approaches. These schemes achieve O(log²N) depth overhead without ancillas and O(logN) with O(N) ancillas, dramatically improving on the O(N) overhead of JW and BK mappings [12]. This represents a fundamental advancement in the asymptotic scaling of fermionic simulation complexity.

The key innovation enabling these improvements involves reformulating time evolution using fSWAP networks with efficient compilation techniques inspired by neutral-atom qubit routing [12]. This approach allows arbitrary permutation of fermionic modes between Trotter layers with circuit depth of only O(log²N), effectively rearranging modes to maintain locality of interactions throughout the simulation.

Dynamical and Hardware-Aware Mappings

Alternative approaches leverage dynamical fermion-to-qubit mappings, where the encoding is modified during computation to maintain locality of operations [30]. These methods typically require O(N) ancilla qubits, mid-circuit measurements, and classical feedforward, but achieve O(logN) overhead while maintaining full parallelism [30].

Hardware-specific mappings have also demonstrated practical success, such as the implementation of Kitaev's honeycomb model as a fermion-to-qubit mapping on neutral-atom quantum computers [31]. This approach utilizes long-range entangled states to encode fermionic statistics, effectively leveraging the topological order native to the hardware platform.

Qudit-Based Approaches

Beyond qubit-based mappings, recent work has explored fermion-to-qudit mappings that leverage multi-level quantum systems to reduce operator non-locality [26]. These approaches can naturally address the locality problem for electron-like fermions by exploiting increased dimensionality to host ancilla-like degrees of freedom within each qudit, avoiding non-local parity strings entirely.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Methodological Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Implementation

| Research Tool | Function/Purpose | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Ternary Tree Structures | Organizes fermionic modes to minimize operator weight | HATT framework [29] |

| fSWAP Networks | Enables reordering of fermionic modes between operations | Logarithmic-overhead scheme [12] |

| Mid-circuit Measurement & Feedforward | Dynamically updates encoding during computation | Dynamic encoding approaches [30] |

| Plaquette Operators | Verifies preservation of fermionic anticommutation relations | Kitaev honeycomb implementation [31] |

| Qudit Gate Sets | Implements operations on multi-level quantum systems | Local fermion-to-qudit mappings [26] |

| Classical Feedforward Control | Applies conditional operations based on measurement outcomes | Dynamic encoding [30], Kitaev model [31] |

Visualization of Key Framework Components

HATT Ternary Tree Structure

HATT Ternary Tree Organization - The ternary tree structure in HATT groups fermionic modes to minimize operator weight in the resulting qubit Hamiltonian through bottom-up construction.

Fermionic Permutation Circuit

Dynamic Encoding via Permutations - Fermionic permutation circuits enable dynamic reencoding between gate layers to maintain operator locality, achievable in O(log²N) depth.

Performance Scaling Comparison

Performance Scaling Relationships - Comparative asymptotic scaling of different fermion-to-qubit mapping approaches, showing HATT's position between traditional and cutting-edge schemes.

The HATT framework represents a significant advancement in Hamiltonian-adaptive fermion-to-qubit mappings, providing consistent 5-20% improvements across diverse fermionic systems without ancillary resource requirements. While newer approaches offer superior asymptotic scaling, HATT maintains practical advantages for current-generation quantum devices and specific Hamiltonian structures.

For researchers and drug development professionals, selection of fermion-to-qubit mapping strategies should consider:

- Problem Size: HATT provides excellent performance for intermediate-scale problems where constant-factor improvements are significant

- Hamiltonian Structure: Strongly structured Hamiltonians benefit most from HATT's adaptive approach

- Hardware Constraints: Qubit-limited scenarios favor HATT's zero-ancilla requirement

- Implementation Complexity: HATT offers favorable tradeoffs between performance and implementation effort

Future research directions include combining HATT's Hamiltonian adaptivity with the asymptotic advantages of logarithmic-overhead schemes, potentially yielding mappings that excel in both constant factors and scaling behavior. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, the optimal fermion-to-qubit mapping strategy will likely remain context-dependent, with HATT occupying an important niche in the growing ecosystem of quantum simulation tools.

The simulation of fermionic systems, fundamental to understanding molecular structures and materials in drug development, is a promising application for quantum computers. A significant challenge in this endeavor is the fermion-to-qubit mapping problem, where the non-local anti-commutation relations of fermionic operators must be encoded onto the local degrees of freedom of qubits. The efficiency of this encoding directly impacts the feasibility and resource requirements of quantum simulations. This guide provides a comparative analysis of advanced compiler frameworks, with a focused examination of Fermihedral—a novel method leveraging Boolean Satisfiability (SAT) solvers for optimal encoding—against other contemporary techniques like heuristic Clifford circuit optimization. We objectively compare their performance, supported by experimental data on gate counts, circuit depth, and simulation accuracy, providing researchers with a clear understanding of the current state-of-the-art.

Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping: Core Concepts and Challenges

Fermion-to-qubit encoding is a crucial step in harnessing quantum computing for the efficient simulation of Fermionic quantum systems, such as those encountered in molecular electronics and drug discovery research [14]. The core challenge stems from the fundamental difference between fermions, which obey anti-commutation relations, and qubits, which are distinguishable quantum bits. A successful mapping must preserve the algebraic structure of the original fermionic Hamiltonian while being efficiently executable on a quantum device.

The performance of a mapping is typically gauged by the properties of the resulting qubit Hamiltonian, particularly the Pauli weight—the number of non-identity Pauli matrices in a term. Lower Pauli weights generally lead to quantum circuits with fewer entangling gates, which are often the most error-prone and expensive operations on near-term quantum hardware [32]. Key mapping strategies have included the Jordan-Wigner transformation, which can lead to non-local operators with high Pauli weight, and the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation, which offers a balance between locality and operator weight [33]. More recent approaches focus on designing problem-tailored mappings that optimize for the specific Hamiltonian of interest, rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all transformation [1].

Methodology: Comparative Analysis Framework

To ensure an objective and scientifically rigorous comparison, we established a framework for evaluating the different compiler methodologies based on the following experimental protocols and metrics.

Experimental Protocols and Metrics

Benchmarking Hamiltonians: The methodologies were tested on a suite of fermionic Hamiltonians representative of problems in quantum chemistry and condensed matter physics. This includes small-molecule electronic structure Hamiltonians [32] and lattice models like the Fermi-Hubbard model with both nearest-neighbor hopping and on-site interactions [1]. These systems are directly relevant for simulating molecular structures in pharmaceutical research.

Performance Metrics: The primary quantitative metrics for comparison are:

- Average Pauli Weight: The average number of non-identity Pauli matrices per term in the mapped Hamiltonian. This directly influences simulation costs.

- Entangling Gate Count: The total number of two-qubit gates (e.g., CNOT gates) required to implement a single Trotter step or variational ansatz. This is a critical resource metric on near-term devices.

- Circuit Depth: The length of the critical path in the compiled quantum circuit, affecting execution time and fidelity.

- Simulation Accuracy: For studies involving real hardware, the accuracy is measured by comparing the computed expectation values or energies to exact classical results or experimental data [14].

Implementation Details:

- Fermihedral translates the mapping problem into a SAT problem using Pauli algebra to encode the constraints of a valid fermion-to-qubit mapping. It employs high-performance SAT solvers to find the optimal mapping and uses strategies to handle larger-scale systems where an exact solution is computationally prohibitive [14].

- Clifford-based Heuristic frames the problem as an optimization over Clifford circuits. It uses simulated annealing to minimize the average Pauli weight of the problem Hamiltonian, exploring the space of Clifford transformations to find efficient mappings [1].

- Conventional Mappings include established, non-tailored encodings like Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev, and ternary-tree-based mappings, which serve as a baseline for performance improvement [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key computational "reagents" and tools essential for work in this field.

Table 1: Key Research Tools and Resources for Fermion-to-Qubit Encoding

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Performance SAT Solver | Software that solves Boolean Satisfiability problems; used by Fermihedral to find optimal encodings by exploring exponentially large search spaces of possible mappings [14]. |

| Clifford Circuit Simulator | A tool to simulate and manipulate Clifford circuits, which are used by the heuristic method to generate and test potential mappings. Clifford circuits are classically simulable, enabling efficient exploration [1]. |

| Pauli Algebra Library | A software library that handles the multiplication, commutation, and anti-commutation relations of Pauli operators. This is fundamental for formulating the constraints in both SAT and heuristic approaches [14]. |

| Quantum Chemistry Package (e.g., PySCF) | Used to generate the second-quantized electronic structure Hamiltonians of small molecules, which serve as primary benchmark problems for evaluating mapping techniques [32]. |

| Variational Quantum Algorithm (VQA) Framework | A software framework (e.g., Pennylane, Cirq) used to implement and test the compiled circuits on simulators and real quantum hardware, measuring performance metrics like gate count and accuracy [14]. |

| 3-Phenyl-1-propylmagnesium bromide | 3-Phenyl-1-propylmagnesium bromide | Grignard Reagent |

| Metopon hydrochloride | Metopon Hydrochloride | High-Purity Opioid Research Chemical |

Comparative Performance Analysis

This section presents a detailed, data-driven comparison of the performance of Fermihedral and the Clifford-based heuristic against conventional encoding methods.

Quantitative Performance Data

The following tables summarize the experimental results reported for the different compilation strategies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Molecular and Lattice Simulations

| Mapping Method | Test System | Reduction in Avg. Pauli Weight | Reduction in Gate Count/Depth | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fermihedral | Diverse Fermionic Systems | Not Explicitly Quantified | "Substantial reductions" in gate counts and circuit depth [14] | Showcased superior implementation costs; real-device experiments on IonQ's quantum processor demonstrated enhanced simulation accuracy [14]. |

| Clifford-based Heuristic | 6x6 Nearest-Neighbor Hopping Model | >40% improvement [1] | Not Explicitly Quantified | Outperformed all ternary-tree mappings, which are considered optimal for single operators, for specific interaction Hamiltonians [1]. |

| Clifford-based Heuristic | 6x6 Hubbard Model | >20% improvement [1] | Not Explicitly Quantified | For Hamiltonians with intermediate complexity, optimized mappings yielded 15% to 40% improvements in average Pauli weight [1]. |

| Other Optimized Compilation | Small-Molecule Simulations | Not Applicable | Up to 24% savings in entangling-gate counts [32] | Achieved savings with no loss of accuracy, demonstrating the impact of non-quantum optimization algorithms applied to quantum circuit compilation [32]. |

Table 3: Characteristics of Compilation Strategies