Fermion-to-Qubit Mappings: Accelerating Quantum Chemistry Simulations for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of fermion-to-qubit mappings, a critical component for simulating quantum chemistry on quantum computers.

Fermion-to-Qubit Mappings: Accelerating Quantum Chemistry Simulations for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of fermion-to-qubit mappings, a critical component for simulating quantum chemistry on quantum computers. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of popular encodings like Jordan-Wigner and Bravyi-Kitaev, explores groundbreaking methods that exponentially reduce simulation overhead, and discusses practical optimization techniques for real-world applications. Furthermore, it examines the validation of these methods through case studies in drug discovery, such as simulating covalent inhibitors and prodrug activation, and compares the performance of different mappings. The goal is to serve as a guide for leveraging these encodings to tackle classically challenging problems in chemistry and biomedicine.

The Bridge from Molecules to Qubits: Foundational Principles of Fermion Encodings

Why Fermion-to-Qubit Mappings are Essential for Quantum Chemistry

Quantum chemistry, with its promise of revolutionizing drug discovery and materials science, stands as one of the most anticipated applications of quantum computing. The fundamental challenge, however, lies in representing electronic structure problems, which are inherently fermionic, on quantum computers that operate on qubits. Fermion-to-qubit mappings solve this critical encoding problem by translating the antisymmetric commutation relations of fermionic operators into the Pauli algebra of qubits. Without these mappings, quantum computers could not simulate molecular systems, catalytic processes, or the electronic interactions underlying modern pharmaceuticals. The development of efficient mappings has therefore become an essential frontier in computational chemistry and quantum algorithm design, bridging the gap between fermionic systems and their qubit representations to unlock quantum advantages in real-world applications.

Theoretical Foundation: From Fermions to Qubits

The Fundamental Encoding Problem

Quantum chemistry simulations begin with the electronic structure problem, where the behavior of electrons in molecules is described by fermionic creation ((ai^\dagger)) and annihilation ((ai)) operators. These operators obey canonical anticommutation relations (CAR): ({ai^\dagger, aj} = \delta{ij}\mathbb{1}), ({ai, aj} = {ai^\dagger, a_j^\dagger} = 0) [1]. This anticommutation property reflects the Pauli exclusion principle and distinguishes fermions from the qubits that form the basic units of quantum processors. Fermion-to-qubit mappings provide the mathematical framework to faithfully represent this fermionic algebra on qubit-based quantum computers, enabling the simulation of molecular Hamiltonians and quantum chemical processes.

A particularly useful formulation employs Majorana operators ((\gammai)), which serve as Hermitian analogs of the creation and annihilation operators: (\gamma{2i-1} = ai + ai^\dagger) and (\gamma{2i} = i(ai^\dagger - ai)) [2] [1]. These operators satisfy the Clifford algebra ({\gammai, \gammaj} = 2\delta{ij}\mathbb{1}) and provide a symmetric representation that facilitates the construction of efficient encodings, particularly for measuring fermionic observables [3].

Key Mapping Approaches and Their Properties

Several strategic approaches have emerged for implementing fermion-to-qubit mappings, each with distinct advantages and limitations for practical quantum chemistry applications:

Jordan-Wigner Transformation (JWT): As the earliest known mapping, JWT preserves locality for 1D fermionic systems but introduces non-locality in higher dimensions, where local fermionic operators map to Pauli strings whose weight scales with system size [2]. This non-locality imposes significant overhead for scalable implementations and reduces robustness to noise.

Bravyi-Kitaev Transformation: This approach offers a middle ground between locality and operator weight, typically resulting in Pauli strings of weight (O(\log n)) for an n-mode system [4]. While more efficient than JWT for some applications, it still faces challenges in higher dimensions.

Topological and Concatenated Codes: Recent advances have introduced mappings based on topological codes and concatenation approaches that achieve high code distances while preserving locality in 2D and 3D systems [2]. These constructions maintain constant stabilizer weights independent of system size and are particularly valuable for fault-tolerant quantum simulation.

Numerically Optimized Mappings: Heuristic optimization frameworks using simulated annealing and Clifford circuits have demonstrated 15-40% improvements in average Pauli weight for specific problem Hamiltonians compared to conventional mappings [5]. These tailored approaches adjust mappings to Hamiltonian structure but require computational overhead for optimization.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Strategies

| Mapping Approach | Locality Preservation | Typical Pauli Weight | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner | 1D only | (O(n)) | Simple implementation; Minimal qubit overhead | Non-local in higher dimensions; High Pauli weight |

| Bravyi-Kitaev | Moderate | (O(\log n)) | Reduced operator weight | Complex implementation; Limited 2D locality |

| Ternary Tree | Structural | (O(\log_3 n)) | Optimal average Pauli weight [4] | Specific to system structure |

| Topological/Concatenated | 2D/3D | Constant (independent of (n)) [2] | High-distance error correction; Locality preservation | Complex experimental realization |

| Numerically Optimized | Variable | Tailored to Hamiltonian | 15-40% improvement for specific systems [5] | Computational optimization cost |

Practical Applications in Drug Discovery and Quantum Chemistry

Quantum-Enhanced Drug Discovery Pipeline

The integration of fermion-to-qubit mappings into drug discovery pipelines enables quantum computation to address critical challenges in molecular design and optimization. A hybrid quantum computing pipeline has been developed specifically for real-world drug discovery problems, demonstrating practical applications in prodrug activation and covalent inhibitor design [6]. This pipeline employs the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) framework, where parameterized quantum circuits prepare molecular wave functions and classical optimizers minimize energy expectations until convergence. Due to the variational principle, the quantum circuit state becomes a faithful approximation of the molecular wave function, enabling measurement of ground state energies and other physico-chemical properties essential for pharmaceutical development.

Case Study: Prodrug Activation Energy Profiling

In one groundbreaking application, researchers employed fermion-to-qubit mappings to calculate Gibbs free energy profiles for carbon-carbon bond cleavage in a prodrug activation strategy for β-lapachone, an anticancer agent [6]. This prodrug design addresses pharmacokinetic limitations of active drugs, enabling cancer-specific targeting validated through animal experiments. Quantum simulations of the prodrug activation process required precise modeling of the solvation effect in the human body, implemented through a pipeline that enables quantum computing of solvation energy based on the polarizable continuum model (PCM).

The research team employed active space approximation to simplify the quantum chemistry problem into a manageable two-electron/two-orbital system, which was then encoded onto qubits using parity transformation [6]. This reduced the problem to a 2-qubit implementation on superconducting quantum devices using a hardware-efficient (R_y) ansatz with a single layer as the parameterized quantum circuit for VQE. The successful calculation of energy barriers for covalent bond cleavage demonstrated the viability of quantum computations for simulating essential processes in real-world drug design.

Case Study: Covalent Inhibition of KRAS

Another significant application involves simulating the covalent inhibition of KRAS, a protein target prevalent in numerous cancers [6]. KRAS mutations, particularly the G12C variant, are common in lung and pancreatic cancers and associated with uncontrolled cell proliferation. Sotorasib (AMG 510), a covalent inhibitor targeting this mutation, represents a crucial approach in cancer therapy by providing prolonged and specific interaction with the KRAS protein.

Quantum computing enhances understanding of such drug-target interactions through QM/MM (Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics) simulations, which are vital in post-drug-design computational validation [6]. Researchers implemented a hybrid quantum computing workflow for molecular forces during QM/MM simulation, enabling detailed examination of covalent inhibitors like Sotorasib and advancing computational drug development for challenging protein targets.

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Quantum Chemistry Applications

| Application | Encoding Method | Quantum Algorithm | Key Measurements | Classical Integration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prodrug Activation Energy Profiling | Parity transformation with active space approximation | VQE with hardware-efficient (R_y) ansatz | Gibbs free energy, solvation effects, bond cleavage barriers | Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) for solvation |

| Covalent Inhibitor Simulation | Fermion-to-qubit mapping for QM region | VQE for force calculations in QM/MM | Binding energies, molecular forces, interaction profiles | Molecular Mechanics (MM) for environment |

| Molecular Ground State Estimation | Various optimized mappings | VQE or phase estimation | Hamiltonian expectation values, correlation energies | Classical optimization of circuit parameters |

| Reduced Density Matrix Learning | Ternary tree mappings [4] | Joint measurement strategies | k-fermion reduced density matrices | Classical shadow tomography |

Technical Implementation and Experimental Protocols

Workflow for Quantum Chemistry Simulations

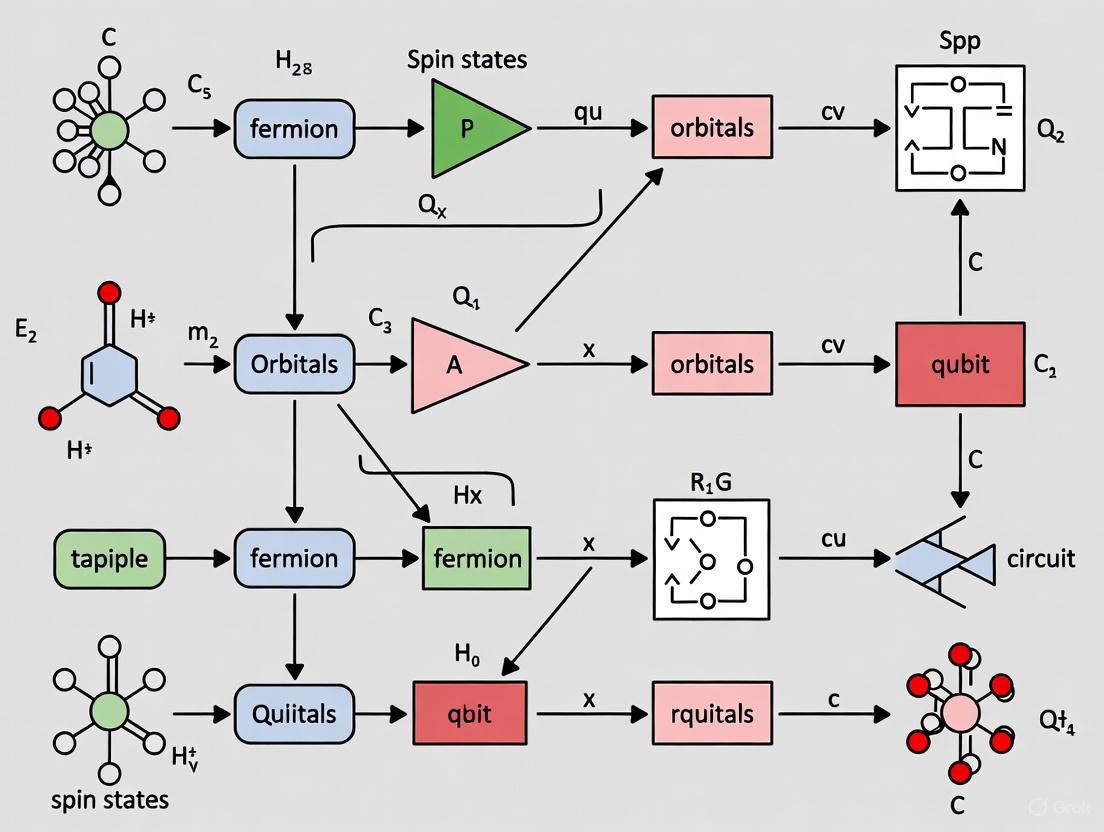

The standard workflow for quantum chemistry simulations using fermion-to-qubit mappings involves multiple systematic steps from molecular specification to result interpretation. The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive process:

Joint Measurement Strategies for Efficient Observables Estimation

A significant advancement in measurement techniques for fermionic systems involves joint measurement strategies that enable efficient estimation of fermionic observables and Hamiltonians. These approaches are particularly valuable in quantum chemistry where the number of measurements can become a performance bottleneck [3]. The following protocol outlines a streamlined joint measurement approach for Majorana operators:

Unitary Randomization: Implement a randomization over a set of unitrices that realize products of Majorana fermion operators.

Gaussian Unitaries Application: Sample a unitary at random from a constant-size set of suitably chosen fermionic Gaussian unitaries.

Occupation Number Measurement: Perform a measurement of fermionic occupation numbers in the rotated basis.

Classical Post-processing: Apply appropriate classical processing to the measurement outcomes to estimate expectation values of interest.

This scheme can estimate expectation values of all quadratic and quartic Majorana monomials to precision ε using (\mathcal{O}(N\log(N)/\epsilon^{2})) and (\mathcal{O}(N^{2}\log(N)/\epsilon^{2})) measurement rounds respectively, matching the performance of fermionic classical shadows while offering advantages in circuit depth and implementation complexity [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Experiments

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Fermionic Gaussian Unitaries | Basis rotation for measurement | Joint measurement strategies [3] |

| Active Space Approximation | Reduces problem size for quantum devices | Focuses on chemically relevant orbitals [6] |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | Hybrid quantum-classical algorithm | Ground state energy calculations [6] |

| Classical Shadows | Efficient state tomography | Estimating multiple observables [3] |

| Parity Transformation | Fermion-to-qubit encoding | Mapping fermionic Hamiltonians to qubits [6] |

| Ternary Tree Mappings | Optimal fermion-to-qubit encoding | Reduced Pauli weight for operators [4] |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Reduces noise impact on results | Improving accuracy on NISQ devices |

| Solvation Models (e.g., PCM) | Incorporates solvent effects | Realistic biological environments [6] |

| phenyl 9H-thioxanthen-9-yl sulfone | Phenyl 9H-Thioxanthen-9-yl Sulfone | Phenyl 9H-thioxanthen-9-yl sulfone is a high-purity chemical for research (RUO). Explore its applications in material science and as a synthetic building block. Not for human use. |

| N,N'-bis(3-acetylphenyl)nonanediamide | N,N'-bis(3-acetylphenyl)nonanediamide, MF:C25H30N2O4, MW:422.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Emerging Advances and Future Directions

Recent Technical Innovations

The field of fermion-to-qubit mappings continues to evolve rapidly with several significant advances enhancing their applicability to quantum chemistry:

Compact Mappings: New encoding methodologies promise to outperform existing methods in both qubit ratio and reduction of encoded Pauli operator weights, potentially impacting near-term simulations in chemistry and materials science [7].

Entanglement-Optimized Mappings: Physically-inspired approaches now enable construction of mappings that significantly simplify entanglement requirements when simulating states of interest, reducing correlations for target states in qubit space [1]. These mappings have demonstrated enhanced performance for ground state simulations of small molecules compared to classical and quantum variational approaches using conventional mappings.

Optimal Mapping Construction: Computational approaches using quadratic assignment problems now enable the construction of general mappings that balance the low-qubit and low-gate demands of present quantum technology [8]. By adding limited ancilla qubits to Jordan-Wigner transformations, these methods have reduced total Pauli weight by as much as 67% for fermionic systems with up to 64 modes.

Implementation Considerations for Hardware Deployment

The practical implementation of fermion-to-qubit mappings on current quantum hardware requires careful consideration of architectural constraints:

Qubit Topology: The physical layout of qubits significantly influences the choice of optimal mapping. For 2D rectangular lattices common in superconducting processors, joint measurement schemes can be implemented with circuit depth (\mathcal{O}(N^{1/2})) using (\mathcal{O}(N^{3/2})) two-qubit gates, offering substantial improvements over alternatives requiring depth (\mathcal{O}(N)) and (\mathcal{O}(N^{2})) two-qubit gates [3].

Error Propagation Characteristics: Different mappings exhibit varying resilience to hardware noise. The non-locality of certain mappings like JWT makes them particularly susceptible to qubit errors, as errors can propagate extensively through the system [2]. Conversely, high-distance codes can detect and correct errors without significantly impacting locality.

Measurement Optimization: Efficient measurement strategies grouping mutually commuting operators reduce the number of distinct circuit executions needed for Hamiltonian expectation value estimation, a critical consideration for near-term devices with limited coherence times.

Fermion-to-qubit mappings represent an indispensable bridge between the fermionic reality of molecular quantum chemistry and the qubit-based architecture of quantum computers. As the field progresses from theoretical constructions to practical applications in drug discovery and materials science, these encodings continue to evolve toward greater efficiency, locality preservation, and error resilience. The integration of optimized mappings with robust measurement strategies and error mitigation techniques is steadily advancing the capabilities of quantum computational chemistry, bringing closer the day when quantum advantage becomes a practical reality for pharmaceutical research and development. As mapping strategies become increasingly tailored to specific problem Hamiltonians and hardware constraints, their role as essential components of the quantum chemistry toolkit will only grow more pronounced, ultimately enabling the simulation of complex molecular systems beyond the reach of classical computation.

The simulation of fermionic systems is a cornerstone application of quantum computing, spanning quantum chemistry, materials science, and drug development. Quantum simulation of molecular Hamiltonians enables the prediction of chemical properties and reaction dynamics that are challenging for classical computers. A fundamental challenge in this endeavor is that qubits, the fundamental units of quantum computers, are inherently bosonic in nature—they commute when acting on different sites. Fermionic particles, particularly electrons, which govern chemical behavior, instead anticommute, making their direct simulation on qubit-based hardware non-trivial [9].

The Jordan-Wigner transformation (JWT) is a foundational mathematical mapping that resolves this fundamental incompatibility. Originally proposed nearly a century ago, this transformation provides a mechanism to represent spin-1/2 fermionic operators using spin operators or, in modern terms, qubit operators [10]. For decades, the JWT was largely a theoretical tool for exactly solving one-dimensional models like the Ising and XY chains. However, with the advent of quantum computing, it has experienced a renaissance as a practical method for enabling quantum chemistry simulations on both near-term and future quantum hardware [9] [11].

This document explores the core concepts of the Jordan-Wigner transformation, with particular emphasis on its linear structure and the significant parallelization challenges that arise in its implementation. Within the broader context of fermion-to-qubit mappings for quantum chemistry simulations, understanding these aspects is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to leverage quantum computing for electronic structure problems.

Fundamental Concepts of the Jordan-Wigner Transformation

Mathematical Foundation

The Jordan-Wigner transformation is essentially a mathematical isomorphism that maps the algebra of fermionic creation and annihilation operators to the algebra of Pauli spin operators. In its core formulation for spinless fermions in one dimension, the transformation is defined as follows [10]:

- Annihilation operator: ( cj = \left( \prod{l

l^z \right) \sigmaj^- ) }> - Creation operator: ( cj^\dagger = \left( \prod{l

l^z \right) \sigmaj^+ ) }> - Number operator: ( nj = cj^\dagger cj = (\sigmaj^z + 1)/2 )

Here, ( \sigmaj^+ = (\sigmaj^x + i\sigmaj^y)/2 ) and ( \sigmaj^- = (\sigmaj^x - i\sigmaj^y)/2 ) are the spin raising and lowering operators, while the product term ( \prod{l

Handling Spin and Higher Dimensions

For quantum chemistry applications involving electrons, the basic transformation must be extended to accommodate spinful fermions. In this case, each spatial orbital requires two distinct operators for spin-up and spin-down states. The transformation maintains the same fundamental structure but with an expanded JW string that includes both spin species [13]:

- ( c{\uparrow,j} \leftrightarrow \left( \prod{l

{\uparrow,l} + n }>{\downarrow,l}} \right) \sigma_{\uparrow,j}^- ) - ( c{\downarrow,j} \leftrightarrow \left( \prod{l

{\uparrow,l} + n{\downarrow,l}} \right) (-1)^{n{\uparrow,j}} \sigma{\downarrow,j}^- ) }>

Note the asymmetry in the treatment of spin-up and spin-down operators, which arises from the ordering convention in the JW string—typically, spin-up orbitals are considered "before" spin-down orbitals within the same spatial site [13].

Extension to two-dimensional systems follows conceptually by imposing a linear ordering on all sites in the higher-dimensional lattice. While physically natural for one-dimensional chains, this ordering must be artificially defined for two-dimensional molecular systems, effectively "folding" the two-dimensional structure into a one-dimensional sequence [14] [13]. Recent research has developed expanded Jordan-Wigner formulations specifically tailored for two-dimensional systems with spinful fermions, enhancing their applicability to realistic quantum chemistry problems [14].

Table 1: Jordan-Wigner Operator Mappings for Different Cases

| Fermionic Operator | Jordan-Wigner Representation | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Spinless ( c_j ) | ( \left( \prod{l |

Basic 1D case with JW string on all left sites |

| Spin-up ( c_{\uparrow,j} ) | ( \left( \prod{l |

JW string includes both spin species |

| Spin-down ( c_{\downarrow,j} ) | ( \left( \prod{l |

Additional phase factor for same-site spin-up occupancy |

| Number operator ( n_j ) | ( (\sigma_j^z + 1)/2 ) | No JW string required |

Linearity of the Jordan-Wigner Transformation

A fundamental characteristic of the Jordan-Wigner transformation is its linearity with respect to fermionic operators. This mathematical property has significant implications for its implementation in quantum simulations of chemical systems.

Mathematical Definition of Linearity

The Jordan-Wigner transformation ( \mathcal{JW} ) acts as a linear map from the vector space of fermionic operators to the vector space of Pauli operators. For any two fermionic operators ( A ) and ( B ), and scalars ( \alpha, \beta \in \mathbb{C} ), the transformation satisfies:

( \mathcal{JW}(\alpha A + \beta B) = \alpha \mathcal{JW}(A) + \beta \mathcal{JW}(B) )

This linearity extends to fermionic Hamiltonians expressed in second quantization. A typical electronic structure Hamiltonian under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation takes the form:

( H = \sum{pq} h{pq} ap^\dagger aq + \frac{1}{2} \sum{pqrs} h{pqrs} ap^\dagger aq^\dagger ar as )

where ( h{pq} ) and ( h{pqrs} ) are one- and two-electron integrals obtained from classical computational chemistry calculations [9]. Through the JWT, this fermionic Hamiltonian is mapped to a qubit Hamiltonian as follows:

( \mathcal{JW}(H) = \sum{pq} h{pq} \mathcal{JW}(ap^\dagger aq) + \frac{1}{2} \sum{pqrs} h{pqrs} \mathcal{JW}(ap^\dagger aq^\dagger ar as) )

The resulting expression is a weighted sum of Pauli strings—tensor products of Pauli operators—that can be directly executed on quantum hardware [9].

Implications for Quantum Simulation

The linearity of the JWT ensures that the mapping process is structure-preserving for the algebraic form of the Hamiltonian. This characteristic simplifies the theoretical analysis of mapped Hamiltonians and guarantees that the spectral properties (eigenvalues and eigenvectors) are preserved, which is crucial for quantum chemistry applications where energy eigenvalues correspond to measurable molecular properties.

However, this linearity comes with computational consequences. While each individual fermionic term maps to a combination of Pauli terms, the non-locality introduced by the JW strings can cause a single fermionic operator to map to a multi-qubit Pauli operator with support on many qubits. For instance, a fermionic hopping term between distant sites ( i ) and ( j ) in the one-dimensional ordering will map to a Pauli string that acts on all qubits between ( i ) and ( j ), resulting in an operator whose weight scales with the distance between the sites [15].

Table 2: Impact of Jordan-Wigner Transformation on Hamiltonian Terms

| Fermionic Term | Qubit Representation | Operator Weight | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| On-site energy ( aj^\dagger aj ) | ( (\sigma_j^z + 1)/2 ) | 1 | Local term, no JW string |

| Nearest-neighbor hopping ( aj^\dagger a{j+1} + \text{h.c.} ) | ( \sigmaj^+ \sigma{j+1}^- + \sigmaj^- \sigma{j+1}^+ ) | 2 | JW string cancels for adjacent sites |

| Long-range hopping ( ai^\dagger aj + \text{h.c.} ) (( i < j )) | ( \sigmai^+ \left( \prod{k=i+1}^{j-1} \sigmak^z \right) \sigmaj^- + \text{h.c.} ) | ( j-i+1 ) | JW string length grows with distance |

| Number operator ( n_j ) | ( (\sigma_j^z + 1)/2 ) | 1 | Always local |

| Coulomb interaction ( ni nj ) | ( (\sigmai^z + 1)(\sigmaj^z + 1)/4 ) | 2 | Remains local after transformation |

Parallelization Challenges

The Root Cause: Non-Locality and Ordering Dependence

A significant challenge in employing the Jordan-Wigner transformation for practical quantum simulations is the restriction on parallelization that arises from the non-local nature of the mapped operators. The core issue stems from the fact that the Jordan-Wigner string creates extensive entanglement between qubits that represent spatially distant fermionic modes [15].

In a fermionic quantum computer (a hypothetical device that natively implements fermionic operations), many fermionic terms in a Hamiltonian could potentially be executed in parallel, particularly those that act on disjoint sets of fermionic modes. However, after the JWT mapping, the resulting Pauli strings frequently overlap in their qubit support, specifically because the JW string for different terms may involve common qubits. This overlap prevents their simultaneous execution on quantum hardware [15].

The problem is particularly acute for the Jordan-Wigner encoding because all Pauli strings resulting from the mapping share a common qubit support pattern. For instance, in systems with all-to-all connectivity, the worst-case circuit depth overhead using JWT was previously thought to scale linearly with the number of fermionic modes, ( O(N) ), despite the fact that individual terms can be implemented with depth ( O(\log N) ) using advanced compilation techniques [15].

Recent Advances and Mitigation Strategies

Recent research has dramatically improved our understanding of these parallelization limitations and has developed innovative approaches to mitigate them:

FSWAP Networks and Qubit Routing: A breakthrough approach reformulates time evolution in the Jordan-Wigner encoding using fermionic swap (fSWAP) networks. This technique enables arbitrary permutation of fermionic modes between Trotter layers with circuit depth of only ( O(\log^2 N) ), exponentially improving the previous ( O(N) ) overhead. After permutation, modes can be rearranged to maximize parallelization opportunities [15].

Ancilla-Assisted Schemes: While ancilla-free mappings minimize qubit count, introducing a limited number of ancilla qubits (e.g., up to 10 ancillas for 64-mode systems) can significantly reduce Pauli weights. One recent study demonstrated Pauli weight reductions of up to 67% in Jordan-Wigner transformations, outperforming state-of-the-art ancilla-free mappings [8].

Optimal Ordering via Quadratic Assignment: The parallelization overhead is highly dependent on the initial ordering of fermionic modes. Researchers have framed the optimal ordering problem as an instance of the quadratic assignment problem to minimize both total and maximum Pauli weights in the mapped Hamiltonian. Computational approaches to this optimization have shown significant improvements in Pauli weights for systems with up to 225 fermionic modes [8].

Geometric Algebra Formulations: Alternative mathematical formulations using Geometric Algebra and Witt bases provide a more natural framework for expressing the JWT, potentially offering more efficient circuit implementations that implicitly address parallelization challenges [9].

These advances collectively demonstrate that the Jordan-Wigner encoding may be closer to optimal in both qubit count and circuit depth than previously recognized, with recent results showing worst-case depth overhead of only ( O(\log^2 N) ) without ancillas and ( O(\log N) ) with ancilla assistance [15].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Standard Protocol: Implementing Electronic Structure Hamiltonians

This protocol details the complete workflow for mapping a quantum chemistry Hamiltonian to qubit operators using the Jordan-Wigner transformation, suitable for implementation on near-term quantum devices.

- Classical Computational Chemistry Software (e.g., PySCF, Psi4, Gaussian): For computing one- and two-electron integrals ( h{pq} ) and ( h{pqrs} ) in a chosen basis set.

- Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Library (e.g., OpenFermion, Qiskit Nature): To handle the symbolic application of the JWT.

- Quantum Computing Framework (e.g., Qiskit, Cirq, PennyLane): For circuit construction and execution.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Molecular Hamiltonian Specification

- Select molecular system and nuclear coordinates.

- Choose appropriate atomic basis set (e.g., STO-3G, 6-31G*).

- Perform Hartree-Fock calculation to obtain molecular orbitals.

- Export one- and two-electron integrals in molecular orbital basis.

Hamiltonian Preparation in Second Quantization

- Construct fermionic Hamiltonian: ( H = \sum{pq} h{pq} ap^\dagger aq + \frac{1}{2} \sum{pqrs} h{pqrs} ap^\dagger aq^\dagger ar as )

- Optionally, freeze core orbitals and define active space for reduced problem size.

Orbital Ordering Optimization

- Apply quadratic assignment algorithms to determine optimal fermionic mode ordering [8].

- Implement ordering that minimizes total Pauli weight or maximum term locality.

- Permute orbital indices in Hamiltonian accordingly.

Jordan-Wigner Transformation

- Apply JWT to each fermionic term in the Hamiltonian:

( aj^\dagger = \left( \prod{l

l^z \right) \sigmaj^+ ) ( aj = \left( \prod{l }>l^z \right) \sigmaj^- ) }> - Expand products and simplify using Pauli algebra rules.

- Apply JWT to each fermionic term in the Hamiltonian:

( aj^\dagger = \left( \prod{l

Hamiltonian Compilation for Quantum Hardware

- Group commuting Pauli terms for simultaneous measurement.

- Apply tensor product basis rotation circuits to diagonalize commuting sets.

- For time evolution, implement Trotterization with optimal ordering of terms.

- For VQE, construct parameterized ansatz circuits inspired by the Hamiltonian structure.

Circuit Optimization and Execution

- Apply gate cancellation and fusion optimizations.

- Transpile to native gate set of target quantum processor.

- Execute circuits with appropriate error mitigation techniques.

Advanced Protocol: Low-Overhead Time Evolution with fSWAP Networks

This protocol implements recent advances that exponentially reduce the circuit depth overhead for fermionic time evolution using the Jordan-Wigner encoding [15].

Specialized Materials

- Quantum Circuit Simulator with support for fermionic operations.

- fSWAP network compilation tools (custom implementation based on recent literature).

- Quantum hardware with nearest-neighbor connectivity or routing tools for virtual connectivity.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Trotterization of Time Evolution

- Divide total evolution time ( t ) into ( r ) Trotter steps: ( e^{-iHt} \approx \left( \prodk e^{-iHk \Delta t} \right)^r )

- For each Trotter step, identify the set of fermionic terms ( {H_k} ) to be implemented.

Term Grouping by Compatibility

- Analyze the fermionic term connectivity graph.

- Identify terms that can be executed in parallel on a fermionic quantum computer.

- Group terms into layers based on their compatibility under the fermionic anticommutation relations.

fSWAP Network Design

- For each Trotter layer, design a fermionic permutation that brings interacting modes into adjacent positions in the JW ordering.

- Implement permutation using depth-optimal fSWAP networks (( O(\log^2 N) ) depth without ancillas).

- The fSWAP gate can be implemented in qubits as: ( \text{fSWAP} = \frac{1}{2}(X \otimes X + Y \otimes Y) + \frac{1}{2}(I \otimes I + Z \otimes Z) )

Term Execution with Local JW Strings

- After permutation, implement each fermionic term using the standard JWT.

- Due to adjacency of interacting modes, JW strings become local, minimizing operator weight.

- Implement time evolution under each term using optimized Pauli gadget compilation.

Reverse Permutation and Iteration

- Apply inverse permutation to restore original mode ordering.

- Proceed to next Trotter layer and repeat steps 3-5.

- For the final step, measure in appropriate basis for observable extraction.

Validation and Benchmarking

- Classical Verification: For small instances (( N \leq 20 )), compare quantum simulation results with exact diagonalization.

- Conservation Laws: Verify preservation of symmetries (particle number, spin) throughout evolution.

- Energy Convergence: Monitor energy convergence with respect to Trotter step size for time evolution.

- Resource Tracking: Quantify circuit depth, gate count, and qubit requirements for scaling analysis.

Visualization of Key Concepts

Jordan-Wigner Transformation Workflow

Diagram 1: Jordan-Wigner transformation workflow for quantum chemistry simulations.

Parallelization Challenge in Jordan-Wigner Mapping

Diagram 2: Parallelization challenge: Independent fermionic terms become overlapping qubit operations after JWT.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Jordan-Wigner Based Quantum Chemistry

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Electronic Structure | PySCF, Psi4, Gaussian | Compute molecular integrals and orbitals | Generate one- and two-electron integrals for fermionic Hamiltonian construction |

| Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping | OpenFermion, Qiskit Nature | Implement JWT and other encodings | Symbolic manipulation of fermionic operators and transformation to qubit operators |

| Quantum Circuit Frameworks | Qiskit, Cirq, PennyLane | Construct and optimize quantum circuits | Provide abstractions for quantum algorithms and hardware-specific compilation |

| fSWAP Network Compilers | Custom implementations | Enable low-overhead fermionic simulations | Implement recent advances in fermionic permutation circuits for parallelization |

| Mode Ordering Optimizers | Quadratic assignment solvers | Minimize Pauli weight in JWT | Find optimal fermionic mode ordering to reduce circuit complexity |

| Quantum Hardware | IBM Quantum, Quantinuum, Pasqal | Execute quantum circuits | Physical devices for running quantum algorithms with increasing qubit counts and fidelities |

| 1-(2-Bromobenzoyl)-4-phenylpiperazine | 1-(2-Bromobenzoyl)-4-phenylpiperazine For Research | Research compound 1-(2-Bromobenzoyl)-4-phenylpiperazine. This product is for research use only (RUO) and not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-Borono-4,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid | 2-Borono-4,5-dimethoxybenzoic Acid|CAS 1256345-91-1 | 2-Borono-4,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid is a versatile reagent for Suzuki cross-coupling in organic synthesis. This product is for research use only and not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Simulating fermionic systems is a cornerstone application of quantum computing, with profound implications for quantum chemistry, materials science, and drug development [15]. The fundamental challenge in this domain stems from the inherent differences between the fundamental units of quantum computers (qubits) and the fermionic particles that constitute molecular systems. Fermionic operators obey canonical anticommutation relations, which must be faithfully preserved when mapping them to qubit operators for quantum simulation [16]. This mapping process introduces computational overhead that can significantly impact the feasibility and efficiency of quantum simulations.

The Bravyi-Kitaev transformation represents a pivotal advancement in fermion-to-qubit mappings, achieving a logarithmic scaling of operator weight—a crucial improvement over previous approaches [4]. This technical breakthrough enables more efficient quantum simulations of electronic structure problems, potentially accelerating research in pharmaceutical development where understanding molecular interactions is paramount. Unlike the Jordan-Wigner transformation, which maps fermionic operators to Pauli strings with weight scaling linearly with the number of fermionic modes, the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation utilizes a sophisticated ternary tree structure to achieve operator weights scaling as O(log N) [4]. This reduction in operator weight directly translates to decreased quantum circuit complexity and reduced resource requirements for simulating molecular Hamiltonians.

For research scientists and drug development professionals, understanding the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation is essential for leveraging quantum computing in investigating molecular properties and reaction mechanisms. The transformation's efficiency makes it particularly valuable for studying complex molecular systems where classical computational methods encounter limitations. By enabling more practical quantum simulations of fermionic systems, the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation opens new avenues for accelerating drug discovery processes and optimizing pharmaceutical compounds.

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Analysis

Mathematical Framework of the Bravyi-Kitaev Transformation

The Bravyi-Kitaev transformation builds upon the mathematical foundation of fermionic algebra and its representation on qubit systems. In a system of N fermionic modes, the transformation maps fermionic creation and annihilation operators to multi-qubit Pauli operators acting nontrivially on approximately ⌈log₃(2N+1)⌉ qubits [4]. This represents an information-theoretic optimality, as it is impossible to construct Pauli operators in any fermion-to-qubit mapping acting nontrivially on less than log₃(2N) qubits on average.

The transformation employs a ternary tree structure to achieve this optimal scaling. In this framework, any single Majorana operator on an N-mode fermionic system is mapped to a multi-qubit Pauli operator with support on O(log N) qubits [4]. This logarithmic scaling is maintained for products of Majorana operators that appear in physical Hamiltonians, making the transformation particularly efficient for quantum simulation applications. The mathematical structure ensures that the canonical anticommutation relations of the original fermionic operators are preserved in their qubit representations, a crucial requirement for accurate simulation of fermionic systems.

Comparative Analysis of Fermion-to-Qubit Mappings

Table 1: Comparison of Key Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Approaches

| Mapping Type | Operator Weight Scaling | Ancilla Qubits Required | Circuit Depth Overhead | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner | O(N) [15] | None [15] | O(N) worst-case [15] | Small system simulations, exact calculations |

| Bravyi-Kitaev | O(log N) [4] | None [4] | O(log² N) with advanced techniques [15] | Quantum chemistry, electronic structure |

| Ternary Tree Variants | O(log N) [4] | None [4] | O(log² N) [15] | Reduced density matrix learning, parallel estimation |

| Ancilla-Assisted Mappings | O(1) for local terms [17] | O(N) [15] [17] | O(log N) to O(1) with measurements [15] [17] | Large-scale simulations, fault-tolerant implementations |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics for Quantum Chemistry Applications

| Parameter | Jordan-Wigner | Standard Bravyi-Kitaev | Advanced Variants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qubit Requirements | N [16] | N [4] | N to O(N) with ancillas [15] [17] |

| Typical Gate Count | O(N²) [18] | O(N²/log N) [18] | O(N log N) to O(N²/log N) [15] [18] |

| Parallelization Potential | Limited [15] | Moderate [15] | High with dynamical mappings [17] |

| Control Precision Requirements | Exponential for some systems [19] | Polynomial [19] | Polynomial with optimized encodings [19] |

The Bravyi-Kitaev transformation's key advantage lies in its balance between operator locality and implementation complexity. While ancilla-assisted mappings can achieve constant operator weight for local terms, they require significant additional qubit resources [17]. The Bravyi-Kitaev transformation achieves improved locality without ancilla qubits, making it particularly valuable for near-term quantum devices where qubit counts are limited. For quantum chemistry applications, this transformation demonstrates superior performance in control precision requirements compared to the Jordan-Wigner transformation, which is crucial for achieving chemical accuracy (typically 0.04 eV) in energy calculations [19].

Recent advancements have further enhanced the Bravyi-Kitaev approach. The development of product-preserving ternary tree fermionic encodings has demonstrated that fermionic time evolution for any encoding in this class can be implemented with depth overhead O(log² N), exponentially improving the best previous bound O(N) on the overhead [15]. These developments maintain the fundamental advantages of the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation while extending its applicability to broader simulation scenarios.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Quantum Circuit Implementation Protocol

Implementing the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation in practical quantum circuits requires careful construction of the mapping between fermionic operators and qubit operators. The following protocol outlines the key steps for implementing the transformation in quantum chemistry simulations:

System Initialization: Begin by preparing N qubits in an initial state corresponding to the fermionic vacuum state |vac⟩, where all occupation numbers are zero. For N fermionic modes, this requires N qubits in the |0⟩ state [4].

Operator Transformation: Apply the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation to map fermionic operators to qubit operators. For each fermionic annihilation operator aâ‚š, the transformation yields a corresponding qubit operator that acts on approximately O(log N) qubits. The exact form of this operator is determined by the ternary tree structure of the mapping [4].

Hamiltonian Construction: Construct the full electronic structure Hamiltonian by summing the transformed operators. For a typical quantum chemistry Hamiltonian in second quantization: H = ∑{p,q} h{pq} aₚ†aq + ∑{p,q,r,s} h{pqrs} aₚ†aq†aras each term must be individually transformed using the Bravyi-Kitaev mapping [19].

Time Evolution Implementation: For dynamics simulations, implement time evolution under the mapped Hamiltonian using Trotter-Suzuki decomposition or more advanced quantum algorithms. The logarithmic operator weight enables more efficient implementation of each Trotter step compared to Jordan-Wigner transformation [15].

Measurement and Readout: Utilize efficient measurement protocols tailored to the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation. Recent advances enable parallel estimation of all k-fermion reduced density matrices (RDMs) by repeating a single quantum circuit for ≲ (2N+1)^k ε^(-2) times, providing significant advantages for quantum chemistry applications [4].

Figure 1: Bravyi-Kitaev Transformation Implementation Workflow

Protocol for Reduced Density Matrix Estimation

A particularly powerful application of the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation is in the efficient estimation of reduced density matrices (RDMs), which are essential for evaluating molecular properties and energies in quantum chemistry simulations. The following specialized protocol leverages the properties of the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation for this task:

State Preparation: Prepare the target quantum state |ψ⟩ on the quantum processor using variational methods, adiabatic state preparation, or other quantum algorithms appropriate for the molecular system of interest.

Parallel Operator Measurement: Implement a measurement scheme that simultaneously estimates expectation values of all k-fermion RDMs. For the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation, this can be achieved by repeating a single quantum circuit for ≲ (2N+1)^k ε^(-2) times to estimate individual elements of all k-fermion RDMs to precision ε [4].

Classical Post-processing: Process the measurement outcomes to reconstruct the elements of the k-fermion RDMs. The Bravyi-Kitaev transformation enables efficient classical processing of these measurement outcomes due to the structured nature of the mapping.

Energy and Property Evaluation: Calculate molecular energies and properties from the estimated RDMs. For the electronic structure Hamiltonian, the energy can be computed as E = ∑{p,q} h{pq} γ{pq} + ∑{p,q,r,s} h{pqrs} Γ{pqrs}, where γ and Γ are the 1- and 2-particle RDMs respectively.

This protocol provides an exponential improvement in the scaling of measurements compared to direct methods, making it particularly valuable for pharmaceutical research where accurate prediction of molecular properties is essential.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Bravyi-Kitaev Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| OpenFermion Package | Provides implementations of fermion-to-qubit transformations [16] | bravyi_kitaev() function for operator transformation |

| Ternary Tree Structures | Reduces operator weight to O(log N) [4] | Custom implementation based on fermionic mode count |

| Measurement Protocols | Enables efficient estimation of observables [3] | Joint measurement of Majorana operators |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Improves accuracy in noisy quantum devices | Zero-noise extrapolation with transformed operators |

| Classical Post-processing | Reconstructs fermionic properties from qubit measurements | Calculation of RDMs from measurement data |

| Quinolinic acid-d3 | Quinolinic acid-d3, CAS:138946-42-6, MF:C7H5NO4, MW:170.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sarubicin A | Sarubicin A, CAS:75533-14-1, MF:C13H14N2O6, MW:294.26 | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Applications and Recent Developments

Applications in Quantum Chemistry and Drug Development

The Bravyi-Kitaev transformation enables several advanced applications with particular relevance to pharmaceutical research and development:

Molecular Energy Calculations: The transformation's efficiency makes practical the computation of ground and excited state energies of drug candidate molecules. The reduced operator weight directly decreases circuit depth and error accumulation, crucial for achieving chemical accuracy on near-term quantum devices [19].

Reaction Pathway Analysis: By enabling more efficient simulation of molecular dynamics, the transformation facilitates investigation of reaction mechanisms and transition states relevant to pharmaceutical synthesis [19].

Molecular Property Prediction: The efficient RDM estimation protocol allows for calculation of molecular properties beyond energies, including dipole moments, polarizabilities, and spectroscopic parameters essential for characterizing drug molecules [4].

Free Energy Landscapes: Advanced implementations combining the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation with quantum phase estimation can potentially map free energy landscapes for molecular systems, providing insights into drug-receptor interactions.

Emerging Methodologies and Hybrid Approaches

Recent research has developed innovative approaches that build upon the foundation of the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation:

Dynamic Fermionic Encodings: Advanced techniques now enable switching between different fermion-to-qubit mappings during computation, achieving depth overhead of O(log N) with O(N) ancilla qubits and mid-circuit measurements [17]. These approaches maintain the advantages of Bravyi-Kitaev while offering additional flexibility.

Hybrid Mapping Strategies: Researchers have developed parametrized hybrid mappings that combine benefits of Jordan-Wigner and Bravyi-Kitaev transformations, producing drastically reduced gate counts that scale with N²/n compared with N² for standard mappings on an N×N lattice where n≪N [18].

Measurement Optimizations: New joint measurement strategies specifically designed for fermionic observables mapped using Bravyi-Kitaev and related transformations can estimate expectation values of all quadratic and quartic Majorana monomials with O(N log N/ε²) and O(N² log N/ε²) measurement rounds respectively [3].

Figure 2: Advanced Bravyi-Kitaev Transformation Methodologies

These advanced approaches demonstrate the ongoing evolution of fermion-to-qubit mapping strategies, with the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation serving as a fundamental building block for increasingly sophisticated quantum simulation methods. For pharmaceutical researchers, these developments translate to more practical and accurate quantum computational tools for investigating molecular systems of therapeutic interest.

The continued refinement of the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation and its hybrid variants promises to further bridge the gap between theoretical quantum algorithms and practical applications in drug discovery and development, potentially accelerating the identification and optimization of novel therapeutic compounds.

The simulation of fermionic systems, central to quantum chemistry and drug development, is a leading application of quantum computers. A critical first step in this process is the efficient mapping of fermionic operators, which describe electrons and molecular systems, onto the Pauli operators of a qubit-based quantum processor. While the Jordan-Wigner (JW) and Bravyi-Kitaev (BK) transformations have served as foundational tools, they possess significant limitations for practical, large-scale quantum simulations. The Jordan-Wigner transformation can introduce non-local operator strings with weights that scale linearly with system size in higher dimensions, while the Bravyi-Kitaev transformation offers only a logarithmic improvement. These limitations manifest as increased quantum gate counts and circuit depths, directly impacting the feasibility of simulations on near-term quantum hardware.

This application note surveys advanced encoding strategies that move beyond these conventional mappings. We focus particularly on ternary tree-based mappings and other modern approaches, such as ZX-calculus unifications and error-correcting frameworks. These methods aim to optimize key performance metrics, including Pauli weight (the number of non-identity terms in a Pauli string), qubit count, and inherent error resilience. For researchers in quantum chemistry, adopting these advanced encodings can lead to more efficient simulations of molecular energies, reaction pathways, and electronic properties, ultimately accelerating materials discovery and pharmaceutical development.

Foundational Mappings and Their Limitations

Before delving into advanced encodings, it is crucial to understand the baseline established by traditional transformations. The following table summarizes the core characteristics of the two most common foundational mappings.

Table 1: Comparison of Foundational Fermion-to-Qubit Mappings

| Mapping | Key Principle | Average Pauli Weight for Single Fermionic Operator | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner (JW) | Maps fermionic anti-commutation to string parity via phase strings. | O(n) | Simple, direct implementation. | Non-local operators in 2D/3D; high Pauli weight. |

| Bravyi-Kitaev (BK) | Uses a binary tree to track parity and occupancy. | O(log n) | Logarithmic scaling of Pauli weight. | More complex transformation logic. |

These foundational mappings, while conceptually critical, create performance bottlenecks. The high Pauli weights of JW and the intermediate scaling of BK translate directly into longer quantum circuits, increased susceptibility to noise, and higher resource overheads—a substantial barrier for quantum chemistry applications where complex molecules require a large number of fermionic modes.

Ternary Tree Mappings: A Log-Scaling Optimal Encoding

Ternary tree mappings represent a significant theoretical and practical advancement in fermion-to-qubit encodings. Introduced by Jiang et al., this approach is provably optimal for mapping single Majorana operators [20] [4].

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundation

The ternary tree mapping is defined on a ternary tree structure. In this framework, any single Majorana operator on an n-mode fermionic system is mapped to a multi-qubit Pauli operator that acts non-trivially on at most ⌈log₃(2n+1)⌉ qubits. This establishes a logarithmic scaling of Pauli weight, a qualitative improvement over the linear scaling of JW. Furthermore, this mapping has been proven to be optimal, meaning it is impossible to construct a fermion-to-qubit mapping where Pauli operators act non-trivially on less than log₃(2n) qubits on average [20] [4].

Application to Reduced Density Matrix Learning

A powerful application of this mapping in quantum chemistry is the efficient learning of k-fermion Reduced Density Matrices (RDMs). In quantum simulation, k-RDMs are essential for evaluating energy and other observable properties. The ternary tree mapping enables a highly efficient protocol for this task.

Using this encoding, one can determine individual elements of all k-fermion RDMs to a precision ε by repeating a single quantum circuit for ≲ (2n+1)^k ε^−2 times. This efficiency stems from a parallel method the authors developed for determining k-qubit RDMs by repeating a circuit ≲ 3^k ε^−2 times, independent of the total system size [4]. This is a substantial improvement over previous, less-scalable schemes.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics of Advanced Encodings

| Encoding Method | Key Innovation | Pauli Weight Scaling | Qubit Overhead | Error Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ternary Tree [20] [4] | Tree-based optimal mapping of Majorana operators. | O(log n) | Low (no ancillas) | No inherent correction. |

| HATT Framework [21] | Hamiltonian-adaptive ternary trees. | Optimal for target H | Low (no ancillas) | Vacuum state preservation. |

| Ladder Encodings [22] | Embedding into surface code defects. | Constant (for local ops) | High (ancillas) | Arbitrary code distance. |

| 3D High-Distance Codes [2] | Concatenation with fermionic color codes. | Constant (for local ops) | High (ancillas) | Arbitrary code distance in 3D. |

Figure 1: Ternary Tree Mapping Workflow. This diagram illustrates the process of applying a ternary tree structure to map a fermionic Hamiltonian to qubits with optimal logarithmic scaling, enabling efficient reduced density matrix (RDM) learning.

Recent Advancements and Unifying Frameworks

The field has progressed beyond the initial ternary tree construction, yielding both practical optimizations and profound theoretical unifications.

Hamiltonian-Adaptive Ternary Tree (HATT)

The HATT framework, introduced by Amazon Science, builds upon ternary tree mappings by optimizing them for specific fermionic Hamiltonians [21]. This is a crucial development for quantum chemistry, where simulations target a specific molecular Hamiltonian. HATT uses a bottom-up construction on the ternary tree to generate a Hamiltonian-aware mapping, directly reducing the Pauli weight of the resulting qubit Hamiltonian. This leads to tangible reductions in quantum circuit overhead, including 5-25% reductions in Pauli weight, gate count, and circuit depth compared to non-adaptive mappings, while retaining the important vacuum state preservation property [21].

A Unifying ZX-Calculus Perspective

A significant theoretical development is a graphical framework that unifies various representations of fermion-to-qubit mappings through ZX-calculus [23]. This work demonstrates the correspondence between linear Fock basis encodings and phase-free ZX-diagrams. It provides a translation from ternary tree mappings to scalable ZX-diagrams, which directly represent the encoder map as a CNOT circuit. A key outcome of this graphical approach is a clear proof that ternary tree transformations are equivalent to linear encodings, unifying seemingly disparate approaches and simplifying the analysis of mapping equivalence [23].

Error-Correcting and High-Distance Encodings

For quantum simulations to be reliable, especially on error-prone hardware, resilience to noise is paramount. A new class of encodings integrates fermion-to-qubit mapping directly with quantum error correction.

Ladder and Perforated Encodings

Recent research has introduced a framework for systematically scaling the code distance of local fermion-to-qubit encodings without increasing the weights of stabilizers [22]. This is achieved by embedding low-distance encodings into the surface code in the form of topological defects. The introduced Ladder Encodings (LE) are optimal for 1D Fermi-Hubbard models. Furthermore, Perforated Encodings were developed to locally encode two fermionic spin modes within the same surface code structure, which is highly relevant for quantum chemistry simulations involving electron spin [22].

High-Distance Codes for 2D and 3D Systems

This approach has been extended to create high-distance stabilizer codes for 2D and 3D fermionic systems [2]. These codes achieve arbitrarily large code distances while maintaining constant stabilizer weights and preserving the locality of operators—a first for 3D systems. The construction is based on concatenating a small-distance fermion-to-qubit code with a high-distance fermionic color code. The overall distance scales as Θ(dFf * dfq), allowing it to be increased arbitrarily by scaling dFf. This provides a robust, scalable pathway for fault-tolerant quantum simulation of fermionic systems in any dimension [2].

Figure 2: High-Distance Code Construction. This diagram shows the concatenation of a low-distance fermion-to-qubit mapping with a high-distance fermionic color code to create an encoding with arbitrarily scalable error correction.

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

Protocol: Hamiltonian-Adaptive Mapping Optimization

Purpose: To generate an optimized fermion-to-qubit mapping for a specific quantum chemistry Hamiltonian to minimize Pauli weight and subsequent circuit complexity.

Procedure:

- Hamiltonian Input: Begin with the second-quantized fermionic Hamiltonian of interest (e.g., for a drug-like molecule).

- Tree Construction: Initialize a ternary tree structure for the fermionic system.

- Clifford Optimization: Translate the mapping problem into a Clifford circuit optimization problem. This involves searching over Clifford circuits that transform the fermionic operators into Pauli operators.

- Simulated Annealing: Employ a simulated annealing algorithm to optimize the Clifford circuit. The cost function is the average Pauli weight of the Hamiltonian terms.

- Mapping Output: The algorithm outputs an optimized encoding, which can be a modified ternary tree or a completely novel mapping.

Validation: A 2025 study used this protocol and demonstrated 15-40% improvements in average Pauli weight for various Hamiltonians. Remarkably, for 6×6 nearest-neighbor Hubbard models, the optimized mapping improved the average Pauli weight by more than 20%, outperforming any non-adaptive ternary-tree-based mapping [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Solution | Function in Research | Example/Representation |

|---|---|---|

| Ternary Tree Data Structure | Provides the scaffolding for optimal, log-scaling Majorana operator mappings. | A balanced ternary tree with 2n+1 leaves for n fermionic modes [20]. |

| ZX-Calculus Software | Unifies different mapping representations and verifies equivalence; simplifies circuit synthesis. | PyZX or other diagrammatic reasoning tools used to represent encodings as phase-free ZX-diagrams [23]. |

| Clifford Circuit Optimizer | The core engine for performing heuristic numerical optimization of custom mappings. | A simulated annealing algorithm that explores the Clifford group to minimize average Pauli weight [24]. |

| Surface Code Simulator | Provides the substrate for embedding and testing high-distance, fault-tolerant encodings. | A library for simulating the surface code with twist defects, as used in Ladder Encodings [22] [2]. |

| Fermionic Color Code | Serves as the high-distance outer code in concatenated, fault-tolerant mapping constructions. | A 2D patch of the fermionic color code used to encode logical fermions with high distance [2]. |

| (R)-2-(Isoindolin-2-yl)butan-1-ol | (R)-2-(Isoindolin-2-yl)butan-1-ol|Research Chemical | |

| 4-(N-Methyl-N-nitroso)aminoantipyrine | 4-(N-Methyl-N-nitroso)aminoantipyrine, CAS:73829-38-6, MF:C12H14N4O2, MW:246.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The evolution beyond Jordan-Wigner and Bravyi-Kitaev transformations marks a mature phase in the development of quantum simulation tools. Ternary tree mappings and their adaptive extensions, such as HATT, offer tangible, near-term advantages for quantum chemistry applications by significantly reducing resource overhead. Concurrently, the unification of these mappings via ZX-calculus provides a powerful theoretical framework for future development.

The integration of fermion-to-qubit mappings with quantum error correction, exemplified by high-distance ladder and color code constructions, paves a clear path toward fault-tolerant quantum simulation of complex molecular systems. For researchers in drug development, these advancements mean that the simulation of increasingly large and biologically relevant molecules is becoming more practical, promising deeper insights into molecular interactions and reaction mechanisms on future quantum hardware.

The simulation of fermionic systems, central to predicting the properties of molecules and materials, is a leading application of quantum computing. A critical preliminary step in such simulations is the fermion-to-qubit mapping, which encodes the fermionic problem onto the qubits of a quantum processor. The choice of mapping profoundly impacts the feasibility and efficiency of the simulation by determining key resource requirements. This document details the three primary metrics for evaluating these mappings—Pauli weight, circuit depth, and qubit overhead—providing a structured framework for researchers in quantum chemistry and drug development to select and optimize encoding strategies. The subsequent sections define these metrics, present comparative data, and outline standardized experimental protocols for their evaluation.

Metric Definitions and Significance

- Pauli Weight: This refers to the number of qubits upon which a Pauli string (a tensor product of Pauli operators I, X, Y, Z) acts non-trivially (i.e., with an X, Y, or Z). After a fermionic operator (like a hopping term (ai^\dagger aj)) is mapped to qubits, it is expressed as a sum of such Pauli strings. The Pauli weight is a key determinant of the measurement cost and the gate complexity required to implement the term as a quantum circuit. Lower-weight operators are generally more efficient to simulate [25] [26] [27].

- Circuit Depth: Defined as the number of time steps needed to execute all gates in a quantum circuit, where gates that can be executed in parallel count as a single step [28]. Circuit depth is a critical metric, especially in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, because it is directly related to the execution time of an algorithm. Deeper circuits are more susceptible to errors from qubit decoherence and gate infidelities, threatening the validity of results [28].

- Qubit Overhead: The number of additional physical qubits required beyond the number of fermionic modes being simulated. Some advanced mappings use ancilla qubits (auxiliary qubits) to achieve lower Pauli weights or shallower circuit depths. While this can improve circuit performance, it comes at the cost of increased qubit count, which is a scarce resource on current hardware [15] [29].

Comparative Analysis of Fermion-to-Qubit Mappings

The table below summarizes the performance of various fermion-to-qubit mappings against the key metrics, highlighting the inherent trade-offs.

Table 1: Comparison of Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Strategies

| Mapping Strategy | Pauli Weight Scaling | Qubit Overhead | Key Characteristics and Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner (JW) [15] [25] | (O(N)) | None (1 qubit per mode) | Simple, but leads to high circuit depth overhead ((O(N))) due to parallelization restrictions. |

| Bravyi-Kitaev (BK) [15] [25] | (O(\log N)) | None (1 qubit per mode) | Reduces Pauli weight but often does not improve depth overhead due to shared qubits in operator strings. |

| Ancilla-Assisted Mappings [15] | (O(\log N)) to (O(1)) | (O(N)) ancillas | Trades space for time; can reduce depth overhead to (O(\log N)) or even (O(1)) for local models. |

| Tree-Based Mappings (e.g., Treespilation) [25] | (O(\log N)) | None to Low | Can be tailored to hardware connectivity; shown to reduce CNOT counts by up to 74% in VQE protocols. |

| Generalized Superfast (GSE) [29] | Tunable, e.g., (O(\log d)) | Moderate to High (e.g., 2N qubits for N modes) | Features built-in error detection/correction; optimizes Pauli weight via graph-theoretic paths. |

| Optimal Enumeration JW [27] | (O(N^{1/4})) improvement | None (or +2 ancillas) | Reduces average Pauli weight by 13.9% (37.9% with 2 ancillas) in 2D lattices via optimized mode ordering. |

Experimental Protocols for Metric Evaluation

Protocol for Pauli Weight Analysis

Objective: To determine the average and maximum Pauli weight of the Hamiltonian terms after a fermion-to-qubit mapping.

- Hamiltonian Term Selection: Identify a representative set of fermionic terms from the target Hamiltonian (e.g., electronic structure Hamiltonian for a molecule). This should include one-body terms ((ai^\dagger aj)) and two-body terms ((ai^\dagger aj^\dagger ak al)).

- Mapping Application: Apply the selected fermion-to-qubit mapping (e.g., JW, BK, GSE) to each fermionic term. This transforms each term into a linear combination of Pauli strings ((P_\ell)).

- Weight Calculation: For each Pauli string in the decomposition, calculate its weight (number of non-identity Pauli operators). For a given fermionic term, compute its average Pauli weight as the sum of the weights of all its constituent Pauli strings, weighted by the absolute value of their coefficients [29] [30].

- Aggregate Reporting: Report the overall average Pauli weight and the maximum Pauli weight across all terms in the Hamiltonian. This provides insight into the measurement cost and the potential gate complexity.

Protocol for Circuit Depth and Qubit Overhead Benchmarking

Objective: To quantify the circuit depth and qubit count required to implement a key quantum subroutine, such as a single Trotter step for time evolution or a VQE ansatz.

- Algorithm Selection: Select a standard algorithm for benchmarking. A common choice is a first-order Trotterization of the time-evolution operator (U = \exp(-iH t)) [15].

- Circuit Compilation:

- Use the fermion-to-qubit mapping to translate the Trotterized sequence of fermionic exponentials into a quantum circuit of native gates (e.g., CNOT, single-qubit rotations).

- Apply standard compilation techniques, including gate cancellation and transpilation for a specific quantum computer architecture (e.g., linear nearest-neighbor or heavy-hex connectivity).

- Depth and Qubit Count Calculation:

- Circuit Depth: Analyze the compiled circuit to determine the critical path of sequential gate operations. All gates that can be executed in parallel are counted as a single time step [28].

- Qubit Overhead: Count the total number of physical qubits required, including any ancilla qubits used by the mapping or compilation process.

- Comparative Analysis: Execute the above steps for different fermion-to-qubit mappings and report the final circuit depth and qubit count for each, enabling a direct comparison of their efficiency.

Visualization of Mapping Selection and Impact

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting a fermion-to-qubit mapping based on hardware constraints and desired simulation properties, and how the choice impacts the key metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section outlines the essential "research reagents"—the theoretical models, software, and hardware considerations—required for experimental work in this field.

Table 2: Essential Tools for Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Research

| Tool Category | Specific Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Models | Fermi-Hubbard Model, Quantum Chemistry Hamiltonians (e.g., from Hartree-Fock) | Serve as standard benchmarks for testing and comparing the performance of different mappings on physically relevant systems [15]. |

| Software Libraries | OpenFermion, PennyLane, Qiskit Nature | Provide high-level interfaces to generate fermionic Hamiltonians, apply various mappings, and compile/analyze the resulting qubit circuits [30]. |

| Algorithmic Primitives | Trotter-Suzuki Decomposition, VQE Ansätze (e.g., UCCSD) | Define the quantum circuits whose resource requirements (depth, gate count) are being optimized. They are the application for the mapped Hamiltonian [15] [25]. |

| Hardware Constraints | Qubit Connectivity (Linear, Square Lattice), Gate Fidelities, Coherence Times | Define the target architecture for circuit compilation. Mappings can be optimized for specific hardware topologies (e.g., using Treespilation for limited connectivity) [25]. |

| 1-[(2R)-piperidin-2-yl]propan-2-one | 1-[(2R)-piperidin-2-yl]propan-2-one, CAS:2858-66-4, MF:C8H15NO, MW:141.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1,2-Diselenolane-3-pentanoic acid | 1,2-Diselenolane-3-pentanoic Acid|High-Purity RUO | Explore 1,2-Diselenolane-3-pentanoic acid, a selenium analog of alpha-lipoic acid, for research into redox biology and enzyme inhibition. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Exponential Leaps: Advanced Methods and Real-World Chemistry Applications

Simulating fermionic systems, such as the electronic structure of molecules, is a prime application for quantum computers, with profound implications for drug discovery and materials science [31]. However, a fundamental challenge arises because quantum computers are built from qubits, which are fundamentally bosonic, while electrons are fermions with specific statistical properties that require careful encoding [17] [32]. Fermion-to-qubit mappings translate fermionic operations into the language of qubits and quantum gates. Traditional mappings like Jordan-Wigner (JW), Bravyi-Kitaev (BK), and Parity introduce significant computational overhead, often manifesting as long strings of Pauli operators that increase circuit depth and qubit requirements, thereby limiting the scale of quantum simulations that can be performed [17] [32].

Dynamical encodings represent a paradigm shift. Instead of using a single, static mapping throughout a computation, this approach dynamically changes the fermion-to-qubit mapping during the calculation using permutation operations and fermionic SWAP (fSWAP) networks [17] [33]. The core principle is to ensure that at any given step in a quantum circuit, the fermionic operations that need to be performed are "local" within the current encoding, dramatically reducing the gate complexity and circuit depth required to simulate fermionic interactions [17]. This technical note details the application of these methods to achieve exponentially lower overhead in quantum simulations for chemistry.

Core Principles and Quantitative Comparisons

The Mechanism of Dynamical Mappings

In a static Jordan-Wigner encoding, the fermionic creation and annihilation operators are mapped to qubit operators with a non-local string of Pauli Z gates: ( a{j}^{\dagger} = \frac{1}{2}(Xj - iYj) \otimes{kj depends on the distance |m(i) - m(j)| in the encoding map m. If the modes are adjacent (|m(i) - m(j)| = 1), the operation requires only a single two-qubit gate [17].

Dynamical encodings leverage this by applying fermionic permutation operators, ℱ_p, between layers of fermionic gates. These permutations reconfigure the mapping such that the next set of fermionic modes to interact are made adjacent in the new encoding [17]. The transformation between encodings is defined by a permutation p on the qubit indices, modifying the mapping from m_in to m_out such that m_out(i) = p(m_in(i)) [17]. This process effectively absorbs the overhead of simulating fermionic statistics into the implementation of these permutations.

Performance Overhead: Asymptotic and Practical Gains

The key breakthrough of recent work is the development of algorithms that implement arbitrary fermionic permutations ℱ_p with O(N log N) two-qubit gates in circuit depth O(log N) for N fermionic modes, an exponential improvement over previous methods [17] [33]. For specific, structured circuits like the Fermionic Fast Fourier Transform (FFFT), the overhead can be reduced further to O(1) by using O(N) ancilla qubits alongside mid-circuit measurement and classical feedforward [17]. This makes the simulation overhead negligible compared to a native fermionic processor.

Table 1: Asymptotic Overhead Comparison of Fermion Simulation Methods

| Method | Gate Count | Circuit Depth | Ancilla Qubits | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Jordan-Wigner | O(N) per gate [17] |

O(N) [17] |

0 | Static, simple mapping [32] |

| Bravyi-Kitaev | O(log N) per gate [32] |

O(log N) |

0 | Balances locality [32] |

| Dynamical (This work) | O(N log N) total [17] [33] |

O(log N) worst case [17] [33] |

0 (or O(N)) |

Time-dependent mapping via permutations [17] |

| Dynamical (with measurements) | Information Missing | O(1) for FFFT [17] |

O(N) [17] |

Adds mid-circuit measurement & feedforward [17] |

Table 2: Application Performance and Resource Estimates

| Application / Task | Key Metric | Standard Method Performance | Dynamical Encoding Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

General Permutation (ℱ_p) |

Circuit Depth | O(N) |

O(log N) |

[17] |

| Fermionic Fast Fourier Transform (FFFT) | Circuit Depth | O(N) |

O(log N) (no ancillas), O(1) (with ancillas) |

[17] [33] |

| Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev (SYK) Model Simulation | Practical Speed-up | Baseline | 10-100x for relevant instances | [17] |

| Quantum Chemistry Hamiltonian (Trotter Step) | Circuit Depth | Polynomial in N |

Polylog(N) with O(N) qubits |

[33] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Fast Fermionic Permutation

This protocol details the steps to implement an arbitrary fermionic permutation ℱ_p on N modes encoded in N qubits using the Jordan-Wigner encoding, achieving O(log N) depth [17].

Research Reagent Solutions Table 3: Essential Components for Permutation Protocol

| Component | Function & Specification |

|---|---|

| Qubit Register | A system of N qubits with non-local connectivity (e.g., trapped ions, neutral atoms) [17]. |

| Jordan-Wigner Basis | The initial static mapping of fermionic modes to qubits [32]. |

Interleave Circuit (â„_p) |

A sub-circuit that permutes modes between two designated groups (A and B) in O(1) depth [17]. |

| Decomposition Algorithm | A classical algorithm (e.g., based on mergesort) to break the target permutation into logâ‚‚(N) interleaves [17]. |

Methodology

- Input Definition: Classically, define the input Jordan-Wigner encoding

m_inand the target output encodingm_out, which is related by the permutationp[17]. - Permutation Compilation: Run the classical decomposition algorithm to compile the overall permutation

pinto a sequence oflogâ‚‚(N)interleave operations,â„_p¹, â„_p², ..., â„_p^{logâ‚‚(N)}[17]. - Circuit Synthesis: For each interleave

â„_pâ±in the sequence, synthesize the corresponding quantum circuit. This circuit will involve parallel two-qubit gates that implement the necessary swaps and reconfigurations between the two groups of modes [17]. - Execution: Apply the synthesized sequence of interleave circuits to the quantum register. The resulting state will be encoded under the desired mapping

m_out.

Protocol 2: Fermionic Fast Fourier Transform (FFFT) with O(1) Overhead

This protocol describes the implementation of the FFFT, a key subroutine for materials and high-energy physics simulation, using dynamical encodings with ancilla qubits to achieve constant depth overhead [17].

Research Reagent Solutions Table 4: Essential Components for FFFT Protocol

| Component | Function & Specification |

|---|---|

| Ancilla-Qubit Register | N data qubits plus O(N) ancilla qubits [17]. |

| Mid-Circuit Measurement | Hardware capability to measure a subset of qubits and use the result in the same circuit [17] [34]. |

| Classical Feedforward | Fast classical control unit to process measurement outcomes and conditionally apply subsequent gates [17]. |

Methodology

- State Preparation: Initialize the

Ndata qubits in the state representing the fermionic wavefunction in the original basis (e.g., real-space). - Dynamic Routing: Instead of a fixed network, use a sequence of fermionic permutations, mid-circuit measurements, and feedforward operations to dynamically route fermionic modes.