Mitigating Readout Errors in Quantum Molecular Computations: Strategies for Resilient Chemistry Simulations

Accurate molecular computations on near-term quantum hardware are critically limited by readout errors.

Mitigating Readout Errors in Quantum Molecular Computations: Strategies for Resilient Chemistry Simulations

Abstract

Accurate molecular computations on near-term quantum hardware are critically limited by readout errors. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on strategies to enhance the resilience of quantum chemistry simulations. We explore the fundamental nature of readout errors and their exponential impact on computational accuracy. The article details practical mitigation methodologies, including Quantum Detector Tomography and advanced shadow tomography, with applications in Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithms. We address key troubleshooting challenges, such as the systematic errors introduced by state preparation in mitigation protocols, and compare the performance and resource overhead of different techniques. Finally, we present validation frameworks and future directions for achieving chemical precision in molecular energy calculations, which is essential for reliable drug discovery and materials development.

Understanding Readout Errors: The Fundamental Challenge in Quantum Chemistry

Defining Readout Errors and Their Impact on Molecular Observables

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a readout error in quantum computing? A readout error, or measurement error, occurs when the process of measuring a qubit's state (typically |0⟩ or |1⟩) reports an incorrect outcome. On real devices, a qubit prepared in |0⟩ has a probability of being reported as |1⟩, and vice-versa. These errors are a significant source of noise in Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices and can heavily bias the results of quantum algorithms, including those for computing molecular observables [1] [2].

How do readout errors affect the calculation of molecular observables? In quantum chemistry simulations, such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), the energy of a molecule is computed as the expectation value of its qubit-mapped Hamiltonian. This Hamiltonian is a sum of Pauli strings [3]. Readout errors corrupt the measured probabilities of each computational basis state, leading to incorrect estimates of each Pauli string's expectation value and, consequently, an inaccurate total energy. This can jeopardize the prediction of molecular properties and reaction pathways in drug development research [2].

Can readout errors be correlated across multiple qubits? Yes. While errors are sometimes assumed to be independent on each qubit, correlated readout errors are common. This means the error probability for one qubit can depend on the state of its neighbors due to effects like classical crosstalk [4]. Simplified models that ignore these correlations may be insufficient for achieving high accuracy [5].

What is the difference between readout error mitigation and quantum error correction? Quantum error correction is a quantum-level process that encodes logical qubits into many physical qubits to detect and correct errors in real-time. In contrast, readout error mitigation is a classical post-processing technique applied to the measurement statistics (counts) from many runs of a quantum circuit. It does not require additional qubits and is designed for pre-fault-tolerant quantum devices [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: My mitigated results are unphysical (e.g., negative probabilities).

- Potential Cause: This is a known pathology of simple matrix inversion methods when the observed data has statistical fluctuations or the response matrix is ill-conditioned [2].

- Solutions:

- Use Constrained Methods: Apply algorithms like Iterative Bayesian Unfolding (IBU) or least-squares minimization with non-negativity constraints. These methods find the closest physical probability distribution to the raw result [1] [2].

- Increase Shot Count: Collect more measurement shots (repetitions of the circuit) to reduce statistical noise in the calibrated response matrix and experimental data [2].

Problem: The calibration process for readout mitigation is too expensive for my qubit count.

- Potential Cause: Characterizing the full

2^n x 2^nresponse matrix fornqubits requires preparing and measuring all2^nbasis states, which becomes intractable for largen[1] [4]. - Solutions:

- Use Bit-Flip Averaging (BFA): This technique applies random bit-flips before measurement and inverts them classically afterward. This symmetrizes the error model, reducing the number of parameters needed to characterize it and lowering the calibration cost [4].

- Assume a Simplified Model: Start with a Tensor Product Noise (TPN) model, which assumes errors are independent per qubit. This only requires calibrating

2nparameters instead ofO(2^n). Be aware that this may not correct for correlated errors [1] [4]. - Leverage Overlapping Tomography: Newer protocols can characterize correlated readout errors using only single-qubit Pauli measurements, avoiding the need for exhaustive calibration of all

2^nstates [7].

Problem: My circuit uses mid-circuit measurements and feedforward; how do I mitigate errors?

- Potential Cause: Standard post-processing mitigation fails here because an erroneous mid-circuit measurement result will cause the wrong feedforward quantum operation to be applied, corrupting the quantum state itself before the final measurement [5].

- Solution: Implement a method like Probabilistic Readout Error Mitigation (PROM). PROM uses gate twirling and probabilistic bit-flips in the feedforward data to average over different quantum trajectories, creating an unbiased estimator for the expectation value at a known sampling overhead [5].

Problem: Mitigation improves some observables but makes others worse.

- Potential Cause: The readout error model may be miscalibrated, or there could be significant time-dependent drift in the device's error rates between calibration and experiment [8].

- Solutions:

- Recalibrate Frequently: Re-run the calibration circuits as close in time to your main experiment as possible to capture the current error landscape [8].

- Use Self-Calibrating Protocols: Integrate calibration sequences directly into your experiment where feasible to ensure the error model and data are temporally aligned [8].

Comparison of Readout Error Mitigation Techniques

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of different mitigation methods to help you select an appropriate strategy.

| Method | Key Principle | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matrix Inversion [1] [2] | Apply pseudo-inverse of confusion matrix to noisy data. | Simple, direct, and fast for small qubit numbers. | Can produce unphysical (negative) probabilities; unstable for large qubit counts. | Small-scale simulations (<~5 qubits) with high shot counts. |

| Iterative Bayesian Unfolding (IBU) [2] | Iteratively apply Bayes' theorem to estimate true distribution. | Always produces physical probabilities; more robust to noise. | Higher computational cost; requires choice of iteration number (a regularization parameter). | Scenarios where matrix inversion fails and statistical noise is a concern. |

| Tensor Product Noise (TPN) [1] [4] | Assume independent errors per qubit; model is a tensor product of 2x2 matrices. | Highly scalable (O(n) parameters); very lightweight calibration and application. |

Cannot correct for correlated readout errors between qubits. | Early experimentation and large qubit counts where correlations are weak. |

| Bit-Flip Averaging (BFA) [4] | Use random bit-flips to symmetrize the error process. | Reduces model complexity; handles correlated errors; simplifies inversion. | Requires adding single-qubit gates to circuits; slight increase in classical post-processing. | General-purpose mitigation that balances scalability and accuracy. |

| Probabilistic REM (PROM) [5] | Use twirling and random bit-flips for feedforward data. | Specifically designed for circuits with mid-circuit measurements and feedforward. | Introduces a sampling overhead that grows with the number of measurements. | Dynamic circuits, quantum error correction syndrome measurements. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calibrating a Full Response Matrix

- Objective: To characterize the complete

2^n x 2^nreadout confusion matrix for a set ofnqubits [1] [2]. - Procedure:

- For each computational basis state

|k⟩(wherekis a bitstring from0...0to1...1):- Prepare the state

|k⟩on the quantum processor. This typically involves initializing all qubits to|0⟩and applyingXgates to qubits that should be in|1⟩. - Immediately measure all qubits in the computational basis.

- Repeat this process for a large number of shots (e.g.,

N_shots = 1000or more) to collect statistics.

- Prepare the state

- Analysis: For each prepared state

|k⟩, compute the probability of measuring each outcome|j⟩. This probabilityp(j|k)is the(j,k)-th entry of the response matrixM. The matrix is column-stochastic, meaning each columnkcontains the probability distribution of outcomes given the prepared state|k⟩[1].

- For each computational basis state

Protocol 2: Readout Error Mitigation via Matrix Inversion

- Objective: To correct the results of a quantum experiment in classical post-processing [1].

- Procedure:

- Calibration: Follow Protocol 1 to obtain the response matrix

M. - Experiment: Run your target quantum circuit (e.g., a VQE ansatz for a molecule) for many shots and record the observed outcome counts, forming a probability vector

p_obs. - Mitigation: Compute the mitigated probability vector by applying the pseudo-inverse of the response matrix:

p_mitigated = M^+ p_obs[1]. - Optional: Physicality Constraint: If

p_mitigatedhas negative entries, find the closest physical probability distribution by solving a constrained optimization problem (e.g., minimizing the L1-norm betweenp_mitigatedand a candidate distribution that is non-negative and sums to 1) [1].

- Calibration: Follow Protocol 1 to obtain the response matrix

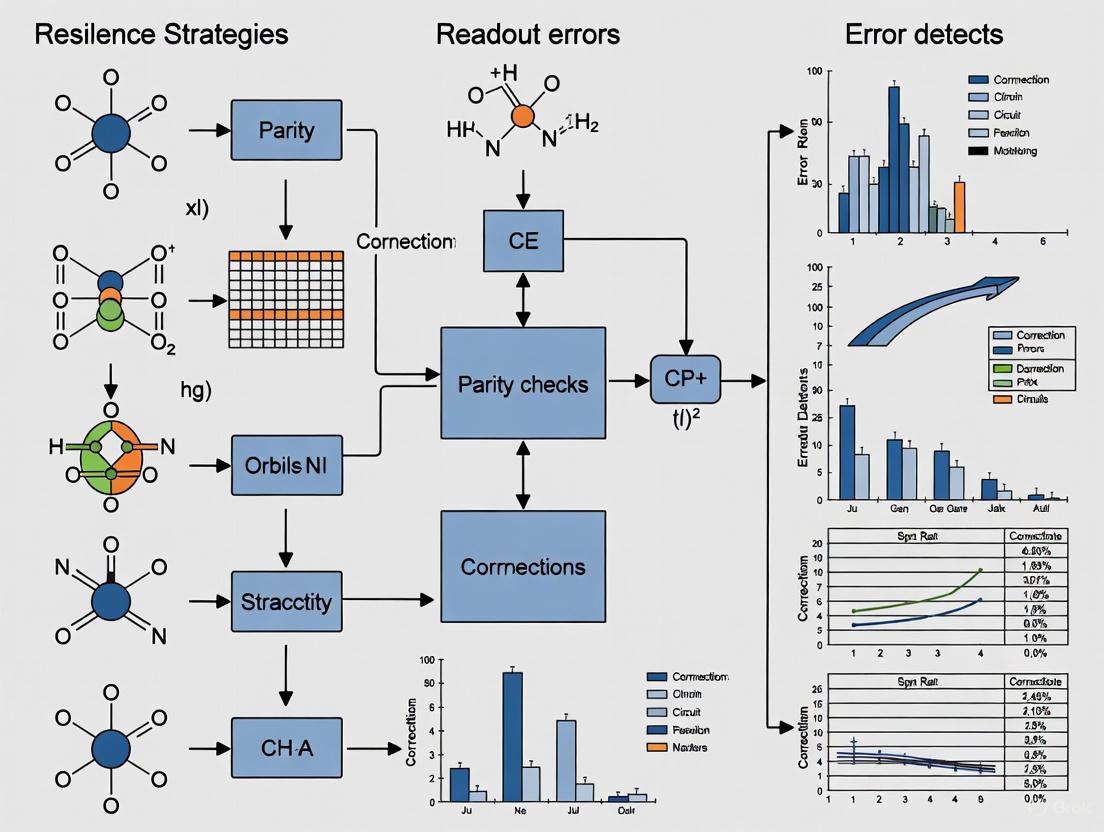

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow between the key concepts and protocols discussed in this guide.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key "research reagents"—the core methodological components and tools used in readout error mitigation.

| Item / Concept | Function / Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Response Matrix (M) | A core classical model of readout errors. Entry M(j,k) is the probability of measuring outcome | j⟩ when the true state was | k⟩ [2] [4]. |

| Confusion Matrix | Another name for the response matrix, often used when discussing the matrix inversion method [1]. | ||

| Bit-Flip Averaging (BFA) | A "symmetrizing reagent." Applying random X gates before measurement removes state-dependent bias, dramatically simplifying the response matrix and reducing calibration cost [4]. | ||

| Iterative Bayesian Unfolding (IBU) | A "stabilizing reagent." An algorithm that corrects the measured statistics iteratively, preventing unphysical results like negative probabilities that can occur with simple matrix inversion [2]. | ||

| Tensor Product Noise (TPN) Model | A "simplifying reagent." An assumption that errors are independent per qubit, which makes modeling and mitigation scalable, though potentially less accurate for correlated errors [1] [4]. | ||

| Positive Operator-Valued Measure (POVM) | The mathematical framework for describing generalized quantum measurements. Noisy detectors are characterized by a noisy POVM, which can be used for rigorous mitigation in tasks like quantum state tomography [6]. | ||

| Propyl pyrazole triol | Propyl pyrazole triol, CAS:263717-53-9, MF:C24H22N2O3, MW:386.4 g/mol | ||

| Talaglumetad Hydrochloride | Talaglumetad Hydrochloride |

For researchers in molecular science and drug development, the promise of quantum computing is immense: simulating molecular interactions and reaction dynamics with unprecedented accuracy. However, this potential is constrained by a fundamental challenge—the exponential scaling of readout errors with qubit count. In molecular computations, where simulating even moderately complex compounds requires numerous qubits, these errors can severely distort results, leading to inaccurate molecular property predictions or faulty drug interaction models. This technical guide examines the root causes of this exponential error scaling and provides practical mitigation strategies to enhance the resilience of your quantum experiments.

FAQ: Understanding Exponential Error Scaling

What is the exponential scaling problem in quantum readout?

The exponential scaling problem refers to the phenomenon where the systematic errors in quantum computation results grow exponentially as more qubits are added to the system. Research has demonstrated that conventional measurement error mitigation methods, which involve taking the inverse of the measurement error matrix, can introduce systematic errors that grow exponentially with increasing qubit count [9]. This occurs because state preparation and measurement (SPAM) errors are fundamentally difficult to distinguish, meaning that while readout calibration matrices mitigate readout errors, they simultaneously introduce extra initialization errors into experimental data [9].

Why is this problem particularly critical for molecular computations?

Molecular simulations require a significant number of qubits to accurately represent complex molecular structures and dynamics. As quantum computations scale to tackle more elaborate molecular systems, the exponential growth of readout errors can cause severe deviations in results. Studies have shown that for large-scale entangled state preparation and measurement—common in molecular simulations—the fidelity of these states can be significantly overestimated when state preparation error is present [9]. Furthermore, outcome results of quantum algorithms relevant to molecular research, such as variational quantum eigensolvers for calculating molecular energy states, can deviate severely from ideal results as system scale grows [9].

How does the readout problem fundamentally affect my quantum measurements?

The quantum readout problem stems from the inherent properties of quantum mechanics, where measuring the state of a quantum system can disturb the system itself, causing the state to change in an unpredictable way due to the uncertainty principle [10]. Quantum measurements are inherently probabilistic, leading to measurement errors where the measured state does not accurately reflect the true state of the system. Additionally, quantum systems are highly fragile and can easily interact with their environment, resulting in a loss of the delicate quantum coherence essential for accurate computation [10]. These challenges compound as qubit count increases, making readout accuracy a fundamental bottleneck.

What is the difference between error mitigation and quantum error correction?

Error mitigation encompasses techniques used on today's noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices to reduce errors without requiring additional qubits. Readout error mitigation specifically uses methods like confusion matrices to correct measurement errors in post-processing [1]. In contrast, quantum error correction (QEC) uses entanglement and redundancy to encode a single logical qubit into multiple physical qubits, allowing detection and correction of errors without directly measuring the quantum information [11] [12]. While QEC promises more robust error control, it requires substantial qubit overhead—currently estimated at 100-1,000 physical qubits per logical qubit—making it resource-intensive for near-term applications [12].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying Readout Error Symptoms

Symptom: Inconsistent results across repeated measurements

- Potential Cause: High readout error rates compounded by increasing qubit counts

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Run the same quantum circuit 10-20 times with identical parameters

- Compare the probability distribution of outcomes across runs

- Calculate the standard deviation of key measurement probabilities

- Resolution Protocol: Implement confusion matrix mitigation (see Experimental Protocols section)

Symptom: Declining fidelity metrics with scaled-up molecular simulations

- Potential Cause: Exponential deviation induced by readout error mitigation

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Benchmark fidelity for the same molecular problem at different qubit counts

- Compare error rates against the upper bound of acceptable state preparation error

- Monitor for overestimated fidelity in large-scale entangled states

- Resolution Protocol: Characterize state preparation error separately from readout error and apply bounds calculated for your qubit scale [9]

Symptom: Unexplained deviations in variational quantum eigensolver results

- Potential Cause: Accumulated readout errors distorting molecular energy calculations

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Compare results with classical simulations where possible

- Check for systematic drift in calculated molecular properties

- Analyze error correlation across qubits in your molecular representation

- Resolution Protocol: Implement correlated readout error mitigation instead of independent qubit error models

Experimental Protocols for Readout Error Mitigation

Protocol 1: Confusion Matrix Mitigation for Molecular computations

The confusion matrix method is a widely used approach for readout error mitigation that characterizes and corrects measurement errors [1].

Materials Required:

- Quantum processor or simulator with readout capabilities

- Classical computation resources for matrix inversion

- Calibration circuits for complete basis state preparation

Methodology:

- Construct the Confusion Matrix:

- Prepare each possible basis state |x⟩ for your n-qubit system

- Measure the resulting output state |y⟩

- Record the probability P(y|x) of observing state |y⟩ when the true state was |x⟩

- Populate confusion matrix A where A_{y,x} = P(y|x)

Apply Mitigation:

- For your experimental results with noisy probability distribution p_noisy

- Compute the pseudoinverse of the confusion matrix A+

- Calculate the mitigated probability distribution: pmitigated = A+ pnoisy

Handle Non-Physical Results:

- If p_mitigated contains negative probabilities, find the closest physical distribution using L1-norm minimization [1]

Limitations Note: This method becomes impractical for large numbers of qubits as the confusion matrix grows exponentially (size 2^n × 2^n) [1]. For molecular computations beyond approximately 10 qubits, consider correlated error mitigation approaches.

Protocol 2: k-Local Correlated Readout Error Mitigation

For larger molecular systems, a scalable approach to readout error mitigation focuses on local correlations.

Methodology:

- Measure confusion matrices for all subsets of k qubits (typically k=1 or 2)

- Assume independence between non-overlapping subsets

- Construct approximate full confusion matrix as tensor product of local matrices

- Apply the same mitigation procedure as in Protocol 1

Advantage: Reduced computational complexity from O(2^(2n)) to O(n choose k) × O(2^(2k))

Protocol 3: Resilience Characterization for Molecular Systems

Based on research into protein-protein interaction network resilience [13], adapt network resilience measures to quantify the robustness of your molecular quantum simulation.

Methodology:

- Model your molecular computation as a network structure

- Calculate baseline network resilience R(G) using information-theoretic measures

- Introduce simulated errors (node isolation/perturbation)

- Measure change in resilience to determine prospective resilience PR_Ï„(G)

- Use gene-expression-based preferential attachment strategies to optimize resilience [13]

Quantitative Analysis of Error Mitigation Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Readout Error Mitigation Approaches for Molecular Computations

| Method | Qubit Scalability | Computational Overhead | Error Model | Best For Molecular Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Confusion Matrix | Poor (>10 qubits) | Exponential O(2^(2n)) | Correlated errors | Small molecules (<8 qubits) |

| k-Local Mitigation | Good (10-20 qubits) | Polynomial O(n^k) | Local correlations | Medium molecules with localized interactions |

| Tensor Product Mitigation | Excellent (20+ qubits) | Linear O(n) | Independent errors | Large systems with minimal correlated noise |

| Resilience-Optimized | Variable | High for setup | Preferential attachment | Critical molecular pathway simulations |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Readout Error Mitigation Experiments

| Resource/Reagent | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Confusion Matrix Characterization Circuits | Calibrates readout error probabilities | Prepare-measure circuits for all basis states |

| Quantum Learning Tools | Extracts low-dimensional features from high-qubit outputs | Quantum scientific machine learning for shock wave detection in molecular dynamics [10] |

| FPGA-Based Control Systems | Enables low-latency feedback for error correction | Qblox control stack with ≈400 ns inter-module communication [12] |

| Real-Time Decoders | Interprets error syndromes for correction | Surface code decoders integrated via QECi or NVQLink interfaces [12] |

| Resilience Quantification Framework | Measures system tolerance to perturbations | Prospective resilience (PR) metric adapted from PPI network analysis [13] |

Visualizing Error Mitigation Workflows

Readout Error Mitigation Process

Exponential Error Scaling Visualization

Advanced Technical Notes

Calculating Acceptable State Preparation Error Bounds

Recent research provides a framework for calculating the upper bound of acceptable state preparation error rate for effective readout error mitigation at a given qubit scale [9]. The key insight is that there exists a critical threshold beyond which readout error mitigation techniques introduce more error than they correct due to the entanglement between state preparation and measurement errors.

For molecular computations, it's essential to:

- Characterize your state preparation error independently before applying readout mitigation

- Compare against the calculated upper bound for your specific qubit count

- Implement purification protocols if state preparation error exceeds acceptable bounds

Future Directions: Quantum Error Correction for Molecular Simulations

While current solutions focus on error mitigation, the field is progressing toward full quantum error correction (QEC). Recent milestones include Google's Willow chip demonstrating exponential reduction in error rate as qubit count scales [12], and advances in surface codes and qLDPC codes that promise reduced overhead for future logical qubits [12]. For molecular research teams, engaging with early QEC demonstrations provides crucial experience for the coming transition to fault-tolerant quantum computing specifically applied to pharmaceutical and molecular simulation challenges.

Distinguishing State Preparation and Measurement (SPAM) Errors

FAQs on SPAM Errors

What are State Preparation and Measurement (SPAM) errors?

In quantum computing, SPAM errors combine noise introduced during two critical stages: initializing qubits to a known state (State Preparation) and reading out their final state (Measurement). These errors are grouped because it is often difficult to separate their individual contributions, and they represent a significant source of inaccuracy that is independent of the quantum gates executed in your circuit [14] [15] [16].

Why is it so challenging to distinguish preparation errors from measurement errors?

Preparation and measurement errors are fundamentally intertwined in experimental data. Standard calibration techniques, like building a measurement error matrix, inherently capture the combined effect of both the initial state imperfection and the noisy readout process. Disentangling them requires specialized techniques, such as gate set tomography or methods that leverage non-computational states, as they must be characterized simultaneously [17] [18].

What are some concrete examples of SPAM errors on real hardware?

- State Preparation Errors: A qubit might fail to initialize to the perfect |0⟩ state due to thermal excitations, leaving it in a mixed state [16].

- Measurement (Readout) Errors: A qubit in state |0⟩ might be incorrectly recorded as |1⟩ (and vice versa). This is characterized by readout error rates, often denoted as δ₀ and δ₠[18].

- Cross-talk: Operations on one qubit can inadvertently affect the state of a neighboring qubit during preparation or measurement [16].

- Photon Loss: In photonic quantum systems, the loss of photons is a major source of error during measurement [16].

How do SPAM errors affect molecular energy calculations, like in VQE?

SPAM errors directly corrupt the expectation values of observables, such as molecular Hamiltonians. For high-precision requirements like chemical precision (1.6 × 10−3 Hartree), unmitigated SPAM errors can dominate the total error budget. Furthermore, conventional Quantum Readout Error Mitigation (QREM) can introduce systematic biases that grow exponentially with the number of qubits if state preparation errors are not properly accounted for, leading to inaccurate energy estimations [19] [18].

Can SPAM errors be separated from gate errors in characterization experiments?

Yes, protocols like Randomized Benchmarking (RB) are specifically designed to isolate the average error rate of quantum gates from SPAM errors. The fidelity decay in RB depends on the sequence of gates and its length, while the SPAM error contributes a constant offset that is independent of the sequence depth, allowing for their separation [15] [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Expectation Values Despite Readout Error Mitigation

Symptoms: After applying standard readout error mitigation (e.g., taking the inverse of a measurement error matrix), your results still show a significant and systematic bias compared to theoretical expectations. This bias may worsen as you scale up your system.

Diagnosis: This is a classic sign that the mitigation technique is not fully accounting for state preparation errors. The standard model p_noisy = M * p_ideal assumes perfect initialization, which is not physically realistic. When preparation errors q_i are present, the true relationship is more complex, and using Mâ»Â¹ alone introduces a systematic bias [18].

Solutions:

- Characterize Initialization Error: Independently benchmark the state preparation error rate

q_ifor each qubit. - Use a Combined SPAM Model: Apply a mitigation matrix

Λthat accounts for both the measurement errorMand the preparation errorq. For a single qubit, this is formulated as [18]:I = Λ * M * ((1-q, q), (q, 1-q))The mitigation matrix is thenΛ = [ [(1-q)/(1-2q), -q/(1-2q)], [-q/(1-2q), (1-q)/(1-2q)] ] * Mâ»Â¹. - Advanced Mitigation: Explore techniques like Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) performed in parallel with your main experiment, which can help build an unbiased estimator for your observables [19].

Problem: Results Degrade with Increasing Qubit Count

Symptoms: The performance of your algorithm (e.g., fidelity of an entangled state) drops more severely than expected as you increase the number of qubits in your molecule or simulation.

Diagnosis: SPAM errors accumulate exponentially with system size. Even if single-qubit SPAM errors are small, the combined error for an n-qubit system can become prohibitive.

Solutions:

- Benchmark Scaling: Perform fidelity estimations on graph states or GHZ states at different scales to quantify how SPAM errors scale on your target hardware [18].

- Error-Aware Algorithm Design: Choose algorithms that are more robust to SPAM errors or use techniques that reduce the required quantum resources.

- Hardware Selection: Choose a quantum processor with lower characterized SPAM errors for larger-scale problems. The table below provides a reference for error rates on different platforms.

Problem: Low Measurement Precision in Molecular Energy Estimation

Symptoms: The standard error in your estimated molecular energy (e.g., from a VQE run) is too high to achieve chemical precision, even with a large number of measurement shots.

Diagnosis: High readout noise and finite shot statistics are preventing you from reaching the required accuracy.

Solutions:

- Use Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements: Implement IC measurements, which allow you to estimate multiple observables from the same dataset and provide a seamless interface for error mitigation methods [19].

- Reduce Shot Overhead: Employ techniques like Locally Biased Random Measurements (classical shadows) to prioritize measurement settings that have a bigger impact on the energy estimation, thereby reducing the number of shots required [19].

- Mitigate Time-Dependent Noise: Use blended scheduling—interleaving circuits for QDT and your main experiment—to average over temporal fluctuations in detector noise [19].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) for SPAM Characterization

This protocol details how to characterize the combined SPAM error using informationally complete measurements [19].

- Input States: Prepare the

2â¿computational basis states for ann-qubit system. This is typically done by applyingXgates to flip qubits from the default |0...0⟩ state. - Measurement: For each prepared basis state, perform a large number of projective measurements in the computational basis.

- Data Analysis: Tally the results to construct a

2â¿ x 2â¿calibration matrixA, where the elementA_ijis the probability of measuring outcomeiwhen the statejwas prepared. - Mitigation: Use this matrix to mitigate future experiments. For a measured probability distribution

p_measured, the mitigated distribution is estimated asp_mitigated = Aâ»Â¹ * p_measured.

Protocol 2: Assessing SPAM Error Scaling with Graph State Fidelity

This protocol helps you understand how SPAM errors impact your specific hardware as you scale up [18].

- State Preparation: Prepare an

n-qubit graph state|GS⟩on your quantum processor. - Efficient Fidelity Estimation: Use randomized measurement techniques to estimate the fidelity

F = Tr(Ï_exp Ï_GS)without the exponential overhead of full quantum state tomography. - Repeat and Scale: Repeat the experiment for increasing values of

n(e.g., 4, 8, 12, ... qubits). - Analysis: Plot the estimated fidelity against the number of qubits. A sharp, exponential drop-off is indicative of significant SPAM error accumulation.

The following tables summarize key error metrics and mitigation overheads.

Table 1: Typical SPAM Error Rates on Various Platforms

| Platform | State Prep Error (per qubit) | Measurement Error (per qubit) | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superconducting (e.g., IBM Eagle) | ~0.1% - 1% (much smaller than readout) [18] | ~1% - 5% [19] [18] | QREM with Mâ»Â¹, QDT |

| Trapped Ions | Information Missing | Information Missing | Gate Set Tomography |

| Photonic | Information Missing | Photon loss is a major error source [16] | Error correction codes |

Table 2: Impact of Advanced Mitigation Techniques on Molecular Energy Calculation [19]

| Technique | Key Metric (Error in Hartree) | Key Metric (Reduction Factor) | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unmitigated Readout | 1% - 5% | (Baseline) | BODIPY molecule on IBM Eagle |

| With QDT & Blended Scheduling | 0.16% | ~6x - 30x reduction | 8-qubit Hamiltonian (Hartree-Fock state) |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for SPAM Error Mitigation

| Item | Function in Experiment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Informationally Complete (IC) Measurement | A framework for measuring a quantum state that allows for the estimation of any observable and provides a natural path for error mitigation [19]. | ||

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | A precise characterization technique used to model the actual measurement process of the quantum device, which is then used to build an unbiased estimator [19]. | ||

| Locally Biased Classical Shadows | A post-processing technique that reduces the number of measurement shots (shot overhead) required to achieve a given precision by prioritizing informative measurement settings [19]. | ||

| Blended Scheduling | An experimental scheduling technique that interleaves different types of circuits (e.g., main experiment and QDT calibration) to average out time-dependent noise [19]. | ||

| Non-Computational States | States outside the typical | 0⟩/ | 1⟩ qubit subspace used as an additional resource to fully constrain and learn state-preparation noise models in superconducting qubits [17]. |

| Thiazesim Hydrochloride | Thiazesim Hydrochloride, CAS:3122-01-8, MF:C19H23ClN2OS, MW:362.9 g/mol | ||

| Vapiprost Hydrochloride | Vapiprost Hydrochloride, CAS:87248-13-3, MF:C30H40ClNO4, MW:514.1 g/mol |

Workflow Diagrams

SPAM Error Mitigation Workflow

Distinguishing SPAM from Gate Errors

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the definitive target for "Chemical Accuracy" and why is it critical in computational chemistry? Chemical accuracy is defined as an error margin of 1.6 milliHartree (mHa) (or 0.0016 Hartree) relative to the exact ground state energy of a molecule [20] [21] [19]. This threshold is critical because reaction rates are highly sensitive to changes in energy; achieving calculations within this precision is necessary for predicting realistic outcomes of chemical experiments and simulations [19].

Q2: What is the fundamental difference between accuracy and precision in the context of molecular energy estimation? In molecular energy estimation, accuracy refers to how close a measured energy value is to the true value. Precision, often reported as the standard error, describes the reproducibility or consistency of repeated measurements [22] [19] [23]. High precision (low standard error) does not guarantee high accuracy, as systematic biases can make results consistently wrong. For results to be chemically useful, both high accuracy (within 1.6 mHa of the true value) and high precision are required [22] [24].

Q3: My unencoded quantum simulation results are consistently outside the chemical accuracy threshold. What is the most effective initial strategy? Encoding your quantum simulation with an error detection code like the [[4,2,2]] code is a highly recommended first step. Research has demonstrated that simulations encoded with this code, combined with readout error detection and post-selection, can produce energy estimates that fall within the 1.6 mHa chemical accuracy threshold, unlike their unencoded counterparts [20] [21].

Q4: How do I mitigate readout errors, especially in circuits with mid-circuit measurements? For circuits with terminal measurements only, Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) can be used to build an unbiased estimator and mitigate detector noise [19]. For the more complex case of mid-circuit measurements and feedforward, a technique called Probabilistic Readout Error Mitigation (PROM) has been developed. This method modifies the feedforward operations without increasing circuit depth and has been shown to reduce error by up to ~60% on superconducting processors [25].

Q5: Are current NISQ-era quantum devices capable of achieving chemical precision? Yes, but it requires sophisticated error mitigation. Recent experiments on IBM quantum hardware have successfully estimated molecular energies for a BODIPY molecule with errors reduced to 0.16% (close to chemical precision) through a combination of techniques including locally biased random measurements and blended scheduling to mitigate time-dependent noise [19]. This indicates that with the right protocols, current hardware can yield useful outcomes for chemical applications [20] [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Accuracy (Systematic Error)

Symptoms: Measurement results are consistently biased away from the known true value, even though the spread of data (precision) may be good [22] [24].

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Uncalibrated Equipment | Check calibration records for instrumentation like analytical balances or pipettes [24]. | Implement a regular calibration schedule using traceable standards [24]. |

| Unmitigated Quantum Readout Noise | Compare results from unencoded circuits with those from circuits using readout error mitigation [19] [25]. | Implement device-agnostic error-mitigation schemes like quantum error detection (QED) with post-selection [20] [21]. |

| Algorithmic Bias | Validate your method against a classical simulation for a small, known system. | Introduce error-correcting codes like the [[4,2,2]] code to detect and correct dominant error sources [20]. |

Poor Precision (Random Error)

Symptoms: High variability in repeated measurements; a large standard deviation in the estimated energy [23].

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Sampling (Shots) | Calculate the standard error of the mean; observe if it decreases as the square root of the number of shots [19]. | Drastically increase the number of measurement shots. Use techniques like locally biased random measurements to reduce the required shot overhead [19]. |

| Time-Dependent Noise Drift | Run the same circuit repeatedly over an extended period and look for systematic drifts in results. | Use blended scheduling, which interleaves different circuit executions to average out temporal noise fluctuations [19]. |

| Environmental Interference | Check for vibrations, temperature fluctuations, or electrical noise affecting sensitive equipment [24]. | Ensure stable operating conditions and proper isolation of equipment. |

Failures in Quantum Error Correction (QEC)

Symptoms: The logical error rate does not improve, or worsens, when using QEC codes.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Error Rate Above Threshold | Benchmark the physical error rates (gate, readout, decoherence) of your quantum hardware. | QEC requires physical error rates to be below a certain threshold (e.g., ~2.6% for atom loss in a specific neutral-atom code) to become effective [27] [28]. Ensure your hardware meets the threshold for your chosen code. |

| Biased Noise not Accounted For | Profile the noise on your hardware to determine if certain errors (e.g., phase-flip) are more likely. | Tailor your QEC code to the noise. For example, surface codes are a robust choice for varied noise profiles, with rotated surface codes often having superior thresholds [28]. |

| Inefficient Decoder | For specific errors like atom loss, compare the performance of a basic decoder versus an advanced one. | Use an adaptive decoder that leverages knowledge of error locations (e.g., from Loss Detection Units). This can improve logical error probabilities by orders of magnitude [27]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Methodology for [[4,2,2]]-Encoded VQE Simulation

This protocol outlines the process for simulating the ground state energy of molecular hydrogen (Hâ‚‚) with enhanced accuracy using a quantum error detection code [20] [21].

- Ansatz Preparation: Prepare the variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) ansatz state for the Hâ‚‚ molecule on the quantum device.

- Circuit Encoding: Encode the ansatz using the [[4,2,2]] quantum error detection code. This code uses 4 physical qubits to represent 2 logical qubits and has a distance of 2, allowing it to detect a single error [20].

- Error Mitigation:

- Execution & Analysis:

- Run the encoded and error-mitigated circuit on a quantum device or simulator with a realistic noise model.

- Estimate the ground state energy and calculate the precision (standard error) of the estimate.

- Compare the result with the exact energy to confirm it is within the 1.6 mHa chemical accuracy threshold.

Workflow for High-Precision Measurement on NISQ Hardware

This workflow details the techniques used to achieve high-precision energy estimation for the BODIPY molecule on an IBM quantum processor [19].

Figure 1: High-precision molecular energy estimation workflow.

Key Performance Data from Recent Studies

Table 1: Comparison of error mitigation techniques and outcomes from recent experiments.

| Molecule | Hardware / Simulator | Key Technique(s) | Reported Accuracy/Precision | Within Chemical Accuracy? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Hydrogen (Hâ‚‚) | Quantinuum H1-1E Emulator | [[4,2,2]] encoding with QED and readout detection [20] [21] | >1 mHa improvement; result within 1.6 mHa [20] [21] | Yes [20] [21] |

| BODIPY-4 (8-qubit Sâ‚€) | IBM Eagle r3 (ibm_cleveland) |

Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT), Blended Scheduling [19] | Reduction of measurement errors to 0.16% [19] | Close to chemical precision [19] |

| Generic Circuits | Superconducting Processors | Probabilistic Readout Error Mitigation (PROM) for mid-circuit measurements [25] | Up to ~60% reduction in readout error [25] | Technique enabler |

Table 2: Error thresholds for selected Quantum Error Correction (QEC) codes under specific noise models.

| QEC Code | Noise Model | Error Threshold | Key Requirement / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Code with Loss Detection [27] | Atom Loss (no depolarizing noise) | ~2.6% | For neutral-atom processors; uses adaptive decoding [27] |

| Rotated Surface Code [28] | Biased/General Noise | >10x higher than current processors | Favored for lower qubit overhead and less complexity [28] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential "reagents" for resilient molecular computations on quantum hardware.

| Item / Concept | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| [[4,2,2]] Code | A quantum error detection code that encodes 2 logical qubits into 4 physical qubits. It is used to detect a single error, allowing for post-selection to improve the accuracy of the computation [20]. |

| Chemical Accuracy (1.6 mHa) | The target precision threshold for quantum chemistry simulations to be considered predictive of real-world chemical behavior. It is the benchmark for successful computation [19]. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | A technique to characterize and model the readout errors of a quantum device. This model is then used to build an unbiased estimator for observables like molecular energy, thereby mitigating readout noise [19]. |

| Post-Selection | A classical processing technique where only measurement results that pass certain criteria (e.g., no errors detected by a QEC code) are kept for the final analysis, discarding erroneous runs [20]. |

| Locally Biased Random Measurements | A strategy for reducing the "shot overhead" (number of circuit repetitions). It prioritizes measurement settings that have a larger impact on the final energy estimate, making the collection of statistics more efficient [19]. |

| Blended Scheduling | An execution strategy that interleaves different quantum circuits (e.g., for measuring different Hamiltonian terms) to average out the effects of slow, time-dependent noise drift in the hardware [19]. |

| Probabilistic Readout Error Mitigation (PROM) | A protocol designed specifically to mitigate readout errors in circuits containing mid-circuit measurements and feedforward. It works by probabilistically sampling an engineered ensemble of feedforward trajectories [25]. |

| Loss Detection Unit (LDU) | A small circuit attached to data qubits in neutral-atom quantum computers to detect the physical loss of an atom, which is a major error source for that platform. It enables more efficient error correction [27]. |

| Tetrahydropyranyldiethyleneglycol | Tetrahydropyranyldiethyleneglycol, CAS:2163-11-3, MF:C9H18O4, MW:190.24 g/mol |

| Zinterol Hydrochloride | Zinterol Hydrochloride, CAS:38241-28-0, MF:C19H27ClN2O4S, MW:414.9 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Readout Errors in Quantum Calculations

This guide helps diagnose and resolve common readout error-related issues when estimating molecular energies on near-term quantum hardware.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Readout Error Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic energy overestimation | Unmitigated state preparation and measurement (SPAM) errors accumulating exponentially with qubit count [29] | Compare results with/without QREM; Check if error scales with system size [29] | Implement self-consistent characterization methods; Set stricter bounds on initialization error rates [29] |

| Failure to achieve chemical precision | High readout errors (∼10â»Â²) and low statistics from limited sampling shots [19] | Quantify readout error rates with detector tomography; Analyze estimator variance [19] | Apply QDT and repeated settings; Use locally biased measurements to reduce shot overhead [19] |

| Inconsistent results between runs | Temporal detector noise and calibration drift [19] | Perform repeated calibration measurements over time | Implement blended scheduling of circuits to average temporal noise [19] |

| Biased estimation of energy gaps | Non-homogeneous noise across different circuit configurations [19] | Check energy consistency across different Hamiltonian-circuit pairs | Use blended execution for all relevant circuits to ensure uniform noise impact [19] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical factors preventing chemical precision in molecular energy calculations? Achieving chemical precision (1.6×10â»Â³ Hartree) is challenged by several factors: inherent readout errors typically around 1-5% on current hardware, limited sampling statistics due to constrained shot numbers, and circuit overheads. Furthermore, state preparation errors can be exacerbated by standard Quantum Readout Error Mitigation (QREM) techniques, introducing systematic biases that grow exponentially with qubit count [19] [29].

Q2: How does qubit count specifically affect the accuracy of my calculations? As the number of qubits increases, the systematic errors introduced by state preparation and measurement (SPAM) can scale exponentially. This occurs because the mitigation matrix used in QREM inadvertently amplifies initial state errors. This effect can lead to a significant overestimation of fidelity for large-scale entangled states and distorts the outcomes of algorithms like VQE [29].

Q3: What practical techniques can I implement now to improve accuracy? The most effective practical techniques include:

- Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): Characterizes your specific hardware's readout noise to build an unbiased estimator [19].

- Locally Biased Random Measurements: Reduces the number of measurement shots required by prioritizing settings that most impact the energy estimation [19].

- Blended Scheduling: Executes different circuits (e.g., for various molecular states) in an interleaved manner to mitigate the impact of time-dependent noise [19].

Q4: Are the energy gaps between molecular states (e.g., Sâ‚€, Sâ‚, Tâ‚) affected differently by noise? Yes. If circuits for different states are run at different times or with different configurations, they can experience varying noise levels, biasing the estimated gaps. Blended scheduling, where all circuits are executed alongside each other, is crucial to ensure any temporal noise affects all estimations homogeneously, leading to more accurate energy differences [19].

Q5: My results looked better after basic error mitigation. Why is there now a warning about systematic errors? Basic error mitigation often improves initial results by correcting simple miscalibrations. However, advanced research shows that these techniques can introduce new, subtle systematic errors that become dominant as you scale up your experiments or require higher precision. It is essential to be aware that these methods have an upper limit of usefulness, dictated by factors like state preparation purity [29].

Experimental Protocols for High-Precision Measurement

Protocol 1: Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) for Readout Error Mitigation

Objective: To characterize and mitigate readout errors using parallel QDT, reducing the estimation bias in molecular energy calculations.

Materials:

- Near-term quantum processor (e.g., IBM Eagle series)

- Software for informationally complete (IC) measurement analysis

Method:

- Preparation: For each qubit, prepare the complete set of basis states (|0⟩, |1⟩, |+⟩, |−⟩, |+i⟩, |−i⟩).

- Execution: Run each preparation circuit multiple times to collect measurement statistics.

- Tomography Reconstruction: Use the collected data to reconstruct the positive operator-valued measure (POVM) that describes the noisy detector on your hardware.

- Inversion: Construct a mitigation matrix from the reconstructed POVM. This matrix is used to correct the results of subsequent experiments.

- Integration: In your molecular energy estimation workflow, execute QDT circuits blended with your main experiment circuits to account for temporal noise drift [19].

Protocol 2: Hamiltonian-Inspired Locally Biased Classical Shadows

Objective: To reduce the shot overhead required for measuring complex molecular Hamiltonians.

Method:

- Hamiltonian Analysis: Analyze the target molecular Hamiltonian (e.g., for BODIPY) to identify the Pauli strings that have the most significant contribution to the total energy.

- Setting Selection: Bias the random selection of measurement settings towards these informative Pauli terms. This maintains the informationally complete nature of the strategy while improving efficiency.

- Data Collection & Post-processing: Perform measurements using the biased settings and employ classical shadow estimation techniques to extract the expectation values of the Hamiltonian terms from the data [19].

Visualization of Resilience Strategies

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for mitigating readout errors in molecular energy estimation, combining the key protocols outlined above.

Workflow for Mitigating Readout Errors

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Resilient Molecular Energy Estimation

| Tool / Technique | Function | Role in Mitigating Readout Errors |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | Characterizes the actual measurement noise of the quantum hardware. | Provides a calibrated mitigation matrix to correct readout errors, directly reducing estimation bias [19]. |

| Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements | A measurement strategy that allows estimation of multiple observables from the same data set. | Enables the application of efficient error mitigation and post-processing methods, offering a robust interface between quantum and classical hardware [19]. |

| Locally Biased Classical Shadows | An advanced sampling technique that prioritizes informative measurements. | Reduces the number of experimental shots (shot overhead) required to achieve a target precision, countering statistical noise [19]. |

| Blended Scheduling | An execution method that interleaves different types of circuits. | Averages out time-dependent detector noise across all experiments, ensuring consistent error profiles [19]. |

| Self-Consistent Characterization | A method for benchmarking state preparation errors. | Helps quantify and set an upper bound on initialization errors, which are a key source of exponential systematic error [29]. |

| Pomalidomide-PEG1-C2-N3 | Pomalidomide-PEG1-C2-N3, MF:C17H18N6O5, MW:386.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fmoc-1,6-diaminohexane | Fmoc-1,6-diaminohexane, MF:C21H26N2O2, MW:338.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Practical Error Mitigation Techniques for Molecular Computations

Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) for Readout Error Characterization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) and why is it crucial for molecular computations? Quantum Detector Tomography is a method for fully characterizing a quantum measurement device by reconstructing its Positive Operator-Valued Measure (POVM). Unlike simple error models, QDT does not assume classical errors and can characterize complex noise sources [6]. For molecular computations, such as estimating energies for drug discovery, high measurement precision is required. Readout errors can severely degrade this precision, and QDT provides a way to mitigate these errors, enabling more reliable results from near-term quantum hardware [30].

How does QDT differ from other readout error mitigation methods? Many common techniques, like unfolding or T-matrix inversion, often assume that readout errors are classical—meaning they can be described as a stochastic redistribution of outcomes. QDT makes no such assumption. It is a more general protocol that is largely readout mode-, architecture-, noise source-, and quantum state-independent. It directly integrates detector characterization with state tomography for error mitigation [6].

What are the common sources of readout noise that QDT can help mitigate? Experimental noise sources that QDT can address include [6] [31]:

- Suboptimal readout signal amplification: Improper amplifier settings can distort the measurement signal.

- Insufficient resonator photon population: Using too few photons in a superconducting resonator readout can lead to non-zero probabilities of incorrect state identification.

- Off-resonant qubit drive: Driving a qubit at a frequency slightly off its resonance can lead to inaccurate state preparation and measurement.

- Shortened coherence times: Effective Tâ‚ and Tâ‚‚ times that are too short can cause the qubit state to decay or dephase during the measurement process.

Can QDT be used to measure multiple molecular observables? Yes. When an informationally complete (IC) POVM is used, the same measurement data can be processed to estimate the expectation values of multiple observables. This is particularly beneficial for measurement-intensive algorithms in quantum chemistry, such as ADAPT-VQE and qEOM [30].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause & Solution |

|---|---|

| Poor reconstruction fidelity after QDT | Cause: The POVM calibration states are poorly prepared or the measurement data is insufficient. Solution: Verify the state preparation circuits. Increase the number of measurement "shots" for each calibration state to reduce statistical fluctuations [6]. |

| Inconsistent QDT results over time | Cause: Temporal variations (drift) in the detector's noise properties. Solution: Implement blended scheduling, where calibration and main experiment circuits are interleaved in time to account for dynamic noise [30]. |

| High shot overhead for molecular energy estimation | Cause: The number of samples required to achieve chemical precision is prohibitively large. Solution: Use techniques like locally biased random measurements, which prioritize measurement settings that have a bigger impact on the energy estimation, thereby reducing the total number of shots required [30]. |

| Mitigation fails for certain noise sources | Cause: QDT performance depends on the type of noise. Solution: Characterize the specific noise source. QDT has been shown to work well for various noise sources, reducing infidelity by a factor of up to 30 in some cases, but its performance may vary [6] [31]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Integrated QDT and QST for Readout Error Mitigation [6]

This protocol uses QDT to characterize the measurement device and then uses that information to mitigate errors in Quantum State Tomography (QST).

- Choose a POVM: Select an informationally complete (IC) POVM, such as the Pauli-6 POVM. For a single qubit, this involves performing projective measurements in the X, Y, and Z bases.

- Perform Quantum Detector Tomography:

- Preparation: Prepare a complete set of calibration states that form a basis for the qubit's Hilbert space. These are typically the eigenstates of the Pauli operators (e.g., |0⟩, |1⟩, |+⟩, |−⟩, |i+⟩, |i−⟩).

- Measurement: For each calibration state, measure it a large number of times (shots) using the IC POVM. This builds a statistics of outcomes for each known input.

- Reconstruction: From this data, reconstruct the POVM elements that describe the actual measurement process, including its noise.

- Perform Quantum State Tomography:

- Preparation: Prepare the unknown quantum state of interest, Ï.

- Measurement: Measure this state using the same IC POVM from step 1, collecting outcome statistics.

- Mitigation: Use the reconstructed POVM effects from step 2 to post-process the outcome statistics from step 3. This yields an unbiased estimate of the ideal, noiseless density matrix ˆÏ.

Performance Data: Readout Error Mitigation

The following table summarizes the effectiveness of readout error mitigation (including QDT-based methods) under different noise conditions, as tested on superconducting qubits [6].

| Noise Source | Mitigation Performance | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal Readout Amplification | Good | Readout infidelity can be significantly reduced. |

| Insufficient Resonator Photon Population | Good | Readout infidelity can be significantly reduced. |

| Off-resonant Qubit Drive | Good | Readout infidelity can be significantly reduced. |

| Shortened Tâ‚ / Tâ‚‚ coherence | Variable | Effectiveness may be reduced for severe coherence losses. |

Application: Molecular Energy Estimation to Chemical Precision [30]

Objective: Estimate the energy of a molecule (e.g., BODIPY) on a near-term quantum device with chemical precision (1.6×10â»Â³ Hartree).

Methodology:

- State Preparation: A state (e.g., Hartree-Fock) is prepared on the quantum processor.

- Informationally Complete Measurement: An IC-POVM is implemented. This can be done through:

- Locally Biased Random Measurements: To reduce the shot overhead by prioritizing important measurement settings.

- Repeated Settings with Parallel QDT: To reduce circuit overhead and characterize the noisy detector.

- Error Mitigation: The data from QDT is used to mitigate readout errors in the energy estimation.

- Blended Scheduling: The circuits for the main experiment and QDT calibration are interleaved in time to mitigate the impact of time-dependent noise.

- Result: This methodology has demonstrated a reduction of measurement errors by an order of magnitude, from 1-5% down to 0.16%, on an IBM Eagle r3 quantum processor [30].

Workflow Diagrams

QDT and State Tomography Workflow

Molecular Energy Estimation with QDT

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function |

|---|---|

| Informationally Complete (IC) POVM | A set of measurement operators that forms a basis, allowing reconstruction of any quantum state or observable. Essential for QDT and mitigating readout errors in complex observable estimation [6] [30]. |

| Calibration States | A set of known quantum states (e.g., Pauli eigenstates) used to characterize the measurement device. They are the input for Quantum Detector Tomography [6]. |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | A hybrid quantum-classical algorithm used to find approximate ground states of molecular systems. Its measurement outcomes are susceptible to readout errors [32] [30]. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) Protocol | The specific procedure for characterizing a quantum measurement device. It involves preparing calibration states, measuring them, and reconstructing the POVM [6] [30]. |

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz | A parameterized quantum circuit designed to respect the constraints and connectivity of specific quantum hardware. Often used in VQE and other algorithms to prepare states [32]. |

| tert-Butyl (10-aminodecyl)carbamate | tert-Butyl (10-aminodecyl)carbamate, CAS:216961-61-4; 62146-58-1, MF:C15H32N2O2, MW:272.433 |

| 4-Carboxy-pennsylvania green | 4-Carboxy-Pennsylvania Green|Dye |

Measurement Error Mitigation via Inverse Matrix Transformation

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is the fundamental principle behind the inverse matrix transformation for measurement error mitigation?

This method operates on the principle that the relationship between ideal (p_ideal) and noisy (p_noisy) measurement probability distributions can be modeled by a classical response matrix, M [18]. The process is described by the linear equation p_noisy = M * p_ideal [18]. Error mitigation is achieved by applying the inverse (or a generalized inverse) of this matrix to the experimentally observed data: p_mitigated ≈ Mâ»Â¹ * p_noisy [4]. This reconstructs an estimate of the error-free probability distribution.

How does this method fit into the broader context of resilience strategies for molecular computations?

In molecular computations, such as those using the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) to calculate molecular energies for drug discovery, obtaining accurate measurement results is paramount [32]. Readout errors can significantly corrupt these results. Integrating inverse matrix mitigation as a post-processing step enhances the resilience of the computational pipeline, providing more reliable data for critical decisions in molecular design without requiring additional physical qubits for full quantum error correction [6] [32].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: The mitigation process seems to work well for small qubit numbers but fails for larger systems. What is happening?

Answer: This is a known scalability challenge. A primary cause is the unintentional incorporation of state preparation errors (SPAM errors) into the mitigation matrix [18]. When the response matrix M is calibrated, it is typically characterized using specific input states (e.g., |0...0⟩, |1...1⟩). If these initial states are prepared imperfectly, the calibration captures a combination of preparation and readout errors. When the inverse of this matrix is applied, it inadvertently amplifies the initial state errors. This systematic error can grow exponentially with the number of qubits, n, severely deviating results at scale [18].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Benchmark Preparation Errors: Independently characterize and quantify the state preparation error rates for your device.

- Refine the Model: If the preparation error rate

q_ifor each qubit is known, the standard inverse matrixMâ»Â¹can be replaced with a more accurate mitigation matrixΛthat accounts for both initialization and readout errors [18]. - Validate at Scale: Always test your mitigation protocol on well-understood benchmark circuits (e.g., GHZ state preparation) as you increase the qubit count to monitor for any emergent exponential bias [18].

FAQ: After applying the inverse matrix, my resulting probabilities are negative or unphysical. Why?

Answer: This is a common occurrence. The mathematically derived inverse of the response matrix, Mâ»Â¹, is not guaranteed to be a physical map (i.e., it may contain negative entries). When this matrix is applied to noisy data, it can produce negative "probabilities" [4]. This often indicates that the simplified error model is struggling to capture the complexity of the actual device noise, or that the matrix inversion is ill-conditioned due to a high level of noise.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Constrained Linear Inversion: Instead of a direct matrix inversion, solve a constrained linear optimization problem. Find a probability vector

pthat minimizes(p_noisy - M*p)²subject to the constraints that all elements ofpare non-negative and sum to one [4]. - Use a More Robust Model: Consider using a simplified error model, such as the Tensor Product Noise (TPN) model, which assumes errors are uncorrelated between qubits. The inverse of a TPN matrix is more tractable and less prone to producing severe unphysical results [4].

FAQ: The calibration of the full response matrix requires an exponentially large number of measurements. Is there a more efficient method?

Answer: Yes, the exponential calibration cost of O(2^n) is a major bottleneck. You can adopt more efficient strategies.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Bit-Flip Averaging (BFA): Implement the BFA protocol [4]. This technique uses random pre-measurement bit-flips (

Xgates) and classical post-processing to symmetrize the effective response matrix. This simplification reduces the number of independent parameters in the model fromO(2^(2n))toO(2^n), drastically cutting calibration costs [4]. - Tensor Product Noise (TPN) Assumption: If qubit readout errors are weakly correlated, you can calibrate a model that assumes errors are local to each qubit. This requires only

2ncalibration measurements (preparing|0...0⟩and|1...1⟩) instead of2^n[4].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calibrating the Full Response Matrix

Objective: To experimentally characterize the complete 2^n x 2^n response matrix M for n qubits.

Methodology:

- Preparation: For each of the

2^ncomputational basis states|k⟩(e.g.,|00...0⟩,|00...1⟩, ...,|11...1⟩):- Prepare the state

|k⟩on the quantum processor.

- Prepare the state

- Measurement:

- Perform a computational basis measurement.

- Repeat this measurement a large number of times (shots) to collect statistics.

- Estimation:

- For each prepared state

|k⟩, the vector of observed probabilities for measuring each outcome|σ⟩forms thek-th column ofM. That is,M_{σ,k} = p(σ | k), the probability of reading outσgiven the initial state wask[4].

- For each prepared state

Considerations: This protocol becomes intractable for even moderate n (e.g., n > 10) due to the exponential number of required experiments [4].

Protocol 2: Implementing Inverse Matrix Mitigation

Objective: To apply the calibrated response matrix to mitigate errors in a new experiment.

Methodology:

- Run Target Experiment: Execute your quantum circuit of interest (e.g., a VQE ansatz for a molecule) and measure the output in the computational basis. Collect statistics to form the noisy probability distribution vector

p_noisy[32]. - Application of Inverse:

- Calculate the mitigated distribution:

p_mitigated = Mâ»Â¹ * p_noisy. - If using a constrained method, solve the least-squares problem for

p_mitigatedwith physical constraints [4].

- Calculate the mitigated distribution:

- Compute Observables: Use the mitigated distribution

p_mitigatedto calculate expectation values of target observables for your application [32].

Quantitative Data and Performance

The performance of inverse matrix mitigation is highly dependent on the underlying noise sources and the system scale. The following table summarizes key findings from recent research.

Table 1: Performance and Scaling of Inverse Matrix Mitigation

| Metric | Reported Performance / Scaling | Context and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Readout Infidelity Reduction | Reduction by a factor of up to 30 [6] | Achieved on superconducting qubits when dominant noise sources were well-captured by the model [6]. |

| Bias Without Mitigation | Grows linearly with gate number: O(ϵN) [33] | ϵ is the base error rate, N is the number of gates. |

| Bias After Mitigation | Grows sub-linearly: O(ϵ'N^γ) with γ ≈ 0.5 [33] | Mitigation changes error scaling to follow the law of large numbers, offering greater relative benefit in larger circuits [33]. |

| Scalability Challenge | Systematic error can grow exponentially with qubit count n [18] |

Primarily linked to unaccounted state preparation errors during calibration [18]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Common Response Matrix Models

| Model Type | Calibration Cost | Key Assumptions | Pros & Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Matrix | O(2^n) states [4] | None; most general model. | Pro: Captures all correlated errors.Con: Exponentially expensive to calibrate and invert. |

| Tensor Product Noise (TPN) | O(n) states (e.g., |0⟩⿠and |1⟩â¿) [4] |

Readout errors are independent (uncorrelated) across qubits. | Pro: Efficient and tractable.Con: Inaccurate if significant correlated errors exist [4]. |

| Bit-Flip Averaging (BFA) | Factor of 2^n reduction vs. full model [4] | Biases can be averaged out via randomization. | Pro: Dramatically reduces cost while capturing correlations.Con: Requires additional random bit-flips during calibration and execution [4]. |

Visualization and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for implementing the inverse matrix transformation for measurement error mitigation, highlighting the two key phases of calibration and mitigation.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Concept | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Response Matrix (M) | A core mathematical object that models the classical readout noise channel. Its inversion is the foundation of the mitigation protocol [18] [4]. |

| Calibration Set ({|k⟩}) | The complete set of 2^n computational basis states. They are used as precise inputs to characterize the measurement apparatus [4]. |

| Bit-Flip Averaging (BFA) | A protocol that uses random X gates to symmetrize the error model, drastically reducing the cost and complexity of calibration [4]. |

| Constrained Linear Solver | A numerical optimization tool used to find physical (non-negative) probability distributions when a direct matrix inverse produces unphysical results [4]. |

| Tensor Product Noise (TPN) Model | A simplified error model that assumes qubit-wise independence, offering a highly efficient but sometimes less accurate mitigation alternative [4]. |

| Norbornene-methyl-NHS | Norbornene-methyl-NHS, MF:C13H15NO5, MW:265.26 g/mol |

| 2-Fluorophenylboronic acid | 2-Fluorophenylboronic Acid|High Purity |

Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements for Multiple Observable Estimation

# Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main advantages of using the tensor network post-processing method over classical shadows for multiple observable estimation?

The tensor network-based post-processing method for informationally complete measurements offers several key advantages over the classical shadows approach [34] [35] [36]:

- Reduced Statistical Error: It can be optimized to provide significantly lower statistical error, decreasing the required measurement budget to achieve a specified estimation precision.

- Scalability: The tensor network structure enables application to systems with a large number of qubits.

- Flexibility: It can be applied to any measurement protocol whose operators have an efficient tensor-network representation.

- Performance Gains: Numerical benchmarks demonstrate statistical errors can be orders of magnitude lower than classical shadows.

Q2: How can I implement a joint measurement strategy for estimating fermionic Hamiltonians in quantum chemistry simulations?

A simple joint measurement scheme for estimating fermionic observables uses the following approach [37]:

- Procedure: Sample from two subsets of unitaries. The first realizes products of Majorana operators, while the second consists of fermionic Gaussian unitaries that rotate blocks of Majorana operators.

- Measurement: Follow with fermionic occupation number measurements.

- Performance: This strategy can estimate expectation values of all quadratic and quartic Majorana monomials with a number of measurement rounds comparable to fermionic classical shadows, but with improved circuit depth requirements on a 2D qubit lattice.

Q3: What role do informationally complete measurements play in real-world drug discovery pipelines?

Informationally complete measurements, particularly when combined with variational quantum algorithms, are being developed to enhance critical calculations in drug discovery [32]:

- Applications: They are applied to tasks such as determining Gibbs free energy profiles for prodrug activation and simulating covalent bond interactions in drug-target complexes.

- Workflow: In a hybrid quantum computing pipeline, a parameterized quantum circuit prepares a molecular wave function. Informationally complete measurements are then performed on this state to estimate physical properties like energy.

- Benefit: This provides a more scalable approach to simulating molecular systems compared to full state tomography.

# Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: High Statistical Variance in Observable Estimation

Symptoms: Unacceptably large statistical errors in estimated expectation values, even with a substantial number of measurement shots.

Solutions:

- Implement Tensor Network Post-Processing: Replace standard classical shadows post-processing with a tensor network-based method. This optimizes the estimators for lower variance [34] [36].

- Leverage Informationally Overcomplete Measurements: Use measurement schemes that provide more information than the minimal IC requirement. The tensor network method can optimally process this extra data to reduce variance [36].

- Optimize Bond Dimension: In the tensor network approach, adjust the bond dimension parameter. Even reasonably low bond dimensions can dramatically reduce errors while maintaining efficiency [36].

Problem 2: Inefficient Scaling to Large Molecular Systems

Symptoms: Measurement protocols become computationally intractable as system size (qubit count) increases.

Solutions:

- Adopt Scalable Measurement Strategies: For fermionic systems, implement the joint measurement strategy which requires only ( \mathcal{O}(N \log(N) / \epsilon^2) ) rounds for quadratic observables in an N-mode system [37].

- Utilize Tensor Network Structure: The inherent scalability of tensor networks allows the method to handle large systems where other optimization techniques fail [34] [36].

- Circuit Depth Optimization: On 2D qubit lattices, the joint measurement scheme offers improved circuit depth (( \mathcal{O}(N^{1/2}) )) compared to classical shadows, making larger systems more feasible [37].

Problem 3: Implementation Complexity for Fermionic Observables

Symptoms: Difficulty in practically implementing measurement schemes for quantum chemistry Hamiltonians.

Solutions:

- Structured Gaussian Unitaries: Use a constant-size set of specifically chosen fermionic Gaussian unitaries to simplify the measurement process for Majorana pairs and quadruples [37].

- Tailored Hamiltonian Strategies: For electronic structure Hamiltonians, specialize the general joint measurement scheme, where only four fermionic Gaussian unitaries are sufficient [37].

- Error Localization: The joint measurement strategy localizes estimation errors to at most two qubits for Majorana pairs and quadruples, making it compatible with error mitigation techniques [37].

# Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Tensor Network Post-Processing for IC Measurements

This protocol details the methodology for implementing low-variance estimation of multiple observables using tensor networks [36].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Perform Informationally Complete Measurements: Prepare multiple copies of the quantum state Ï and measure each copy using a pre-selected informationally complete POVM ( { \Pi_k } ).

- Record Outcome Frequencies: For S total measurement shots (state preparations and measurements), record the frequency ( f_k ) of each outcome k.

- Construct Tensor Network Estimator: Instead of inverting the measurement channel, parameterize the estimator for each observable O as a tensor network. The goal is to find coefficients ( \hat{\omega}k ) such that ( \hat{O} = \sumk \hat{\omega}k \Pik ) provides an unbiased estimate of O with minimal variance.

- Optimize Using DMRG-like Algorithm: Variationally optimize the tensor network coefficients to minimize the expected variance. This involves solving a quadratic optimization problem constrained by the unbiasedness condition ( \sumk \hat{\omega}k \Pi_k = O ).

- Compute Estimates: For each observable of interest, compute the estimate ( \overline{\omega} = \sumk fk \hat{\omega}_k ).

Key Requirements:

- The measurement operators ( \Pi_k ) and target observables must have efficient tensor network representations.

- Classical computational resources for tensor network optimization.

Protocol 2: Joint Measurement of Fermionic Observables

This protocol describes the strategy for efficiently estimating fermionic Hamiltonians relevant to quantum chemistry [37].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Prepare the Quantum State: Prepare the fermionic state of interest on the quantum processor.

- Sample Unitaries: Randomly select a unitary from two distinct subsets:

- First Subset: Unitaries that realize products of Majorana fermion operators.

- Second Subset: Fermionic Gaussian unitaries (specifically chosen for the target observables).

- Apply Selected Unitary: Implement the selected unitary on the quantum state.