Navigating Convergence Issues in Adaptive Variational Algorithms: From Quantum Chemistry to Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of convergence challenges in adaptive variational quantum algorithms (VQAs), such as ADAPT-VQE and qubit-ADAPT, which are pivotal for quantum chemistry and drug discovery on...

Navigating Convergence Issues in Adaptive Variational Algorithms: From Quantum Chemistry to Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of convergence challenges in adaptive variational quantum algorithms (VQAs), such as ADAPT-VQE and qubit-ADAPT, which are pivotal for quantum chemistry and drug discovery on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. We explore the foundational causes of convergence problems, including noisy cost function landscapes and ansatz selection. The review systematically compares methodological advances and their application in molecular systems and multi-orbital models, presents actionable troubleshooting and optimization strategies for improved stability, and validates these approaches through statistical benchmarking and hardware demonstrations. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this work synthesizes current knowledge to guide the reliable application of adaptive VQAs in biomedical research.

Understanding the Roots: Why Adaptive Variational Algorithms Struggle to Converge

A technical guide to diagnosing and resolving convergence issues in adaptive variational algorithms.

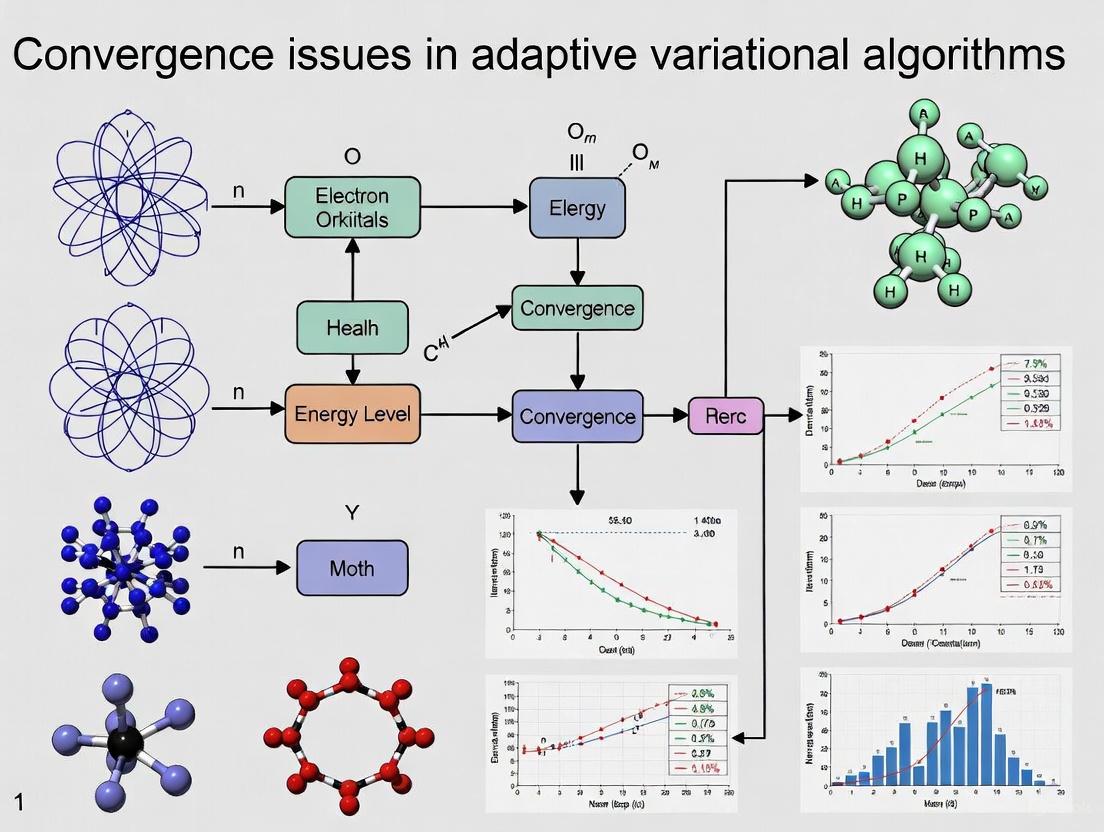

ADAPT-VQE Algorithm Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the iterative circuit construction process of the ADAPT-VQE algorithm.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my ADAPT-VQE simulation stagnate well above the chemical accuracy threshold?

This is typically caused by statistical sampling noise when measurements are performed with a limited number of "shots" on quantum hardware or emulators. The algorithm's gradient measurements and parameter optimization are highly sensitive to this noise [1]. For example, research shows that while noiseless simulations perfectly recover exact ground state energies, introducing measurement noise with just 10,000 shots causes significant stagnation in water and lithium hydride molecules [1].

Q2: How do I choose an appropriate operator pool for my system?

The operator pool must be complete (guaranteed to contain operators necessary for exact ansatz construction) and hardware-efficient. For qubit-ADAPT, the minimal pool size scales linearly with qubit count, drastically reducing circuit depth compared to fermionic ADAPT [2]. Fermionic ADAPT typically uses UCCSD-type pools with single and double excitations, but generalized pools or k-UpCCGSD can provide shallower circuits [3] [4].

Q3: What causes barren plateaus in ADAPT-VQE and how can I mitigate them?

Barren plateaus occur when gradients become exponentially small in system size. Recent convergence theory for VQE identifies that parameterized unitaries must allow movement in all tangent-space directions (local surjectivity) to avoid convergence issues [5]. When this condition isn't met, optimizers get stuck in suboptimal solutions. Specific circuit constructions with sufficient parameters can satisfy this requirement [5].

Q4: Why does my algorithm fail to converge on real quantum hardware?

NISQ devices introduce both statistical noise (from finite measurements) and hardware noise (gate errors, decoherence). While gradient-free approaches like GGA-VQE show improved noise resilience [1], current hardware noise typically produces inaccurate energies. One successful strategy is to retrieve parameterized operators calculated on QPU and evaluate the resulting ansatz via noiseless emulation [1].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Convergence Issues and Solutions

| Problem Scenario | Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Stagnation | Insufficient operator pool completeness [2] | Check if gradient norm plateaus above threshold [4] | Use proven complete pools (e.g., qubit-ADAPT pool) [2] |

| Noisy Gradients | Finite sampling (shot noise) [1] | Compare noise-free vs. noisy simulations | Increase shot count or use gradient-free methods [1] |

| Parameter Optimization Failure | Barren plateaus or local minima [5] | Monitor parameter updates and gradient variance | Employ quantum-aware optimizers with adaptive step sizes [3] |

| Excessive Circuit Depth | Redundant operators in ansatz [2] [1] | Analyze operator contribution history | Use qubit-ADAPT for hardware-efficient ansätze [2] |

| Hardware Inaccuracies | NISQ device noise [1] | Compare QPU results with noiseless simulation | Run hybrid observable measurement [1] |

Advanced Diagnostic Techniques

Gradient Norm Analysis: The ADAPT-VQE algorithm stops when the norm of the gradient vector falls below a threshold ε [4]. Monitor this gradient norm throughout iterations. A healthy convergence shows steadily decreasing gradient norms, while oscillation indicates noise sensitivity.

Operator Selection History: Track which operators are selected at each iteration. Repetitive selection of the same operator types may indicate pool inadequacy or optimization issues.

Energy Convergence Profile: Compare energy improvement per iteration. For LiH in STO-3G basis, proper convergence should show systematic energy decrease toward FCI, reaching chemical accuracy (1 mHa) [6].

Experimental Protocols

Standard ADAPT-VQE Implementation

Objective: Compute electronic ground state energy of a molecular system using adaptive ansatz construction.

Methodology:

System Initialization:

Operator Pool Preparation:

Iterative Algorithm Execution:

- Compute gradients: (\frac{\partial E}{\partial \thetam} = \langle \Psi(\theta{k-1}) \| [H, Am] \| \Psi(\theta{k-1}) \rangle) for all pool operators [4]

- Select operator with largest gradient magnitude [4]

- Append selected operator to ansatz circuit

- Optimize all parameters in current ansatz [3]

- Check convergence against threshold (e.g., gradient norm < 10â»Â³) [3]

Termination:

- Final energy output

- Ansatz circuit reconstruction

- Parameter validation [3]

Convergence Verification Protocol

Purpose: Distinguish true convergence from stagnation due to numerical or hardware issues.

Procedure:

- Reference Calculation: Perform noiseless statevector simulation for benchmarking [1] [3]

- Noise Characterization: Compare results with increasing shot counts (1k, 10k, 100k) to identify statistical noise effects [1]

- Gradient Analysis: Verify gradient norms decrease systematically rather than oscillating randomly

- Threshold Testing: Validate results across multiple convergence thresholds (e.g., 10â»Â², 10â»Â³, 10â»â¶) [4]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents

| Component | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pool | Provides operators for adaptive ansatz construction | UCCSD excitations [3], Qubit-ADAPT pool [2] |

| Initial State | Starting point for variational algorithm | Hartree-Fock reference state [3] [6] |

| Optimizer | Classical routine for parameter optimization | L-BFGS-B [3], COBYLA [4], Gradient descent [5] |

| Measurement Protocol | Method for evaluating expectation values | SparseStatevectorProtocol [3], Shot-based measurement [1] |

| Convergence Metric | Criterion for algorithm termination | Gradient norm [4], Energy change threshold |

| 11-Demethyltomaymycin | 11-Demethyltomaymycin, CAS:55511-85-8, MF:C15H18N2O4, MW:290.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Meso-Zeaxanthin | Meso-Zeaxanthin, CAS:31272-50-1, MF:C40H56O2, MW:568.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implementation Checklist

Pre-Experiment Setup:

- Molecular geometry defined

- Active space selected (if using active space approximation)

- [ Hamiltonian generated and mapped to qubits

- Operator pool constructed and validated for completeness

Algorithm Execution:

- Initial state preparation verified

- Gradient calculation protocol established

- Optimization parameters tuned (step size, tolerance)

- Convergence criteria defined

Post-Processing:

- Energy convergence profile analyzed

- Final parameters recorded

- Ansatz circuit complexity assessed

- Results validated against reference methods

In the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, quantum hardware is characterized by significant levels of inherent noise that directly impact the performance of quantum algorithms. For researchers working with Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs)—including the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA)—this noise presents a substantial challenge by fundamentally distorting the cost function landscape [7] [8]. The cost function, which measures how close a quantum circuit is to the problem solution, becomes increasingly difficult to optimize effectively as noise flattens its landscape, creating regions known as barren plateaus (BPs) where gradient information vanishes and convergence stalls [9] [5].

This technical guide addresses the critical relationship between quantum noise and cost function landscapes, providing researchers with diagnostic and mitigation strategies. Understanding these dynamics is particularly crucial for applications in drug development and materials science, where algorithms like VQE are used to simulate molecular structures and reaction dynamics [10] [8]. The following sections offer practical guidance for identifying and addressing noise-related convergence issues in adaptive variational algorithms.

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing Barren Plateaus in Experimental Results

Barren plateaus (BPs) are regions in the optimization landscape where the cost function gradient vanishes exponentially with increasing qubit count, severely impeding training progress [9] [7]. The following workflow provides a systematic approach to diagnose this issue in your experiments:

Table: Diagnostic Metrics for Barren Plateaus

| Metric | Concerning Value | Acceptable Range | Measurement Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Variance | < 10â»â´ | > 10â»Â³ | Compute variance of cost function gradients across parameter shifts using parameter-shift rule [8] |

| Cost Function Deviation | < 1% from initial value | > 5% decrease within 50 iterations | Track cost function value over optimization iterations [9] |

| Parameter Sensitivity | < 0.1% change in cost | > 1% change in cost | Perturb parameters by ±π/4 and measure cost response [5] |

| Noise Acceleration Factor | 2-4x faster BP onset | < 1.5x faster BP onset | Compare qubit count where BPs appear in noise-free vs. noisy simulations [9] |

When diagnosing BPs, note that global cost functions (measuring all qubits) typically exhibit earlier BP onset compared to local cost functions (measuring individual qubits) [9] [7]. This effect is further exacerbated by noise, which can accelerate BP emergence by a factor of 2-4x in circuits with 8+ qubits [9].

Mitigating Noise-Induced Optimization Failures

When noise is identified as the primary cause of optimization failure, employ these targeted mitigation strategies:

Observable Selection Protocol:

- For global cost functions: Test PauliZ and custom Hermitian observables, which demonstrate superior noise resilience compared to PauliX and PauliY [9]

- For local cost functions: Implement PauliZ observables, which maintain training efficiency up to 10 qubits even under noisy conditions [9]

- Custom observable design: Construct problem-specific Hermitian observables aligned with your target circuit output

Error Mitigation Integration:

- Zero Noise Extrapolation (ZNE): Systematically amplify noise through pulse stretching or gate repetition, then extrapolate to the zero-noise limit [11]

- Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC): Characterize noise channels and apply inverse operations during classical post-processing [11]

- Dynamical Decoupling: Implement precisely timed control pulses to suppress decoherence during idle qubit periods [11]

Circuit Structure Optimization:

- Implement shallow circuits: Design ansätze with minimal depth to reduce noise accumulation

- Apply qubit selection: Utilize qubits with lower error rates (lower QEP) for critical operations [11]

- Incorporate connectivity awareness: Design circuits that respect hardware connectivity to minimize SWAP overhead

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my variational algorithm converge well in simulation but fail on actual quantum hardware?

This discrepancy stems from the fundamental difference between noise-free simulations and noisy hardware environments. Quantum noise in NISQ devices distorts the cost function landscape, accelerating the onset of barren plateaus and creating false minima [9] [7]. The distortion occurs because noise processes like amplitude damping progressively reduce the measurable signal while introducing random perturbations that flatten the optimization landscape. To bridge this gap, incorporate realistic noise models in your simulations and implement error mitigation techniques like ZNE when moving to hardware [11].

Q2: How does observable selection genuinely impact noise resilience in cost function landscapes?

Observable selection directly influences how noise manifests in your cost function landscape. Research demonstrates that:

- PauliZ observables maintain trainability up to 8 qubits under noise, while PauliX and PauliY exhibit flatter landscapes and earlier BP onset [9]

- Custom Hermitian observables can actually exploit noise to maintain trainability up to 10 qubits by creating truncated yet structured landscapes [9]

- The performance gap between observables widens with increasing qubit count, with PauliZ outperforming others by up to 40% in convergence rate for 6+ qubit systems [9]

Q3: What is the concrete relationship between circuit depth, qubit count, and noise-induced barren plateaus?

The relationship follows an exponential decay pattern where gradient variance decreases exponentially with both qubit count and circuit depth. Noise accelerates this process, effectively shifting the BP onset to shallower circuits and fewer qubits [9] [7]. For example:

- In noise-free environments, BPs may appear at 12+ qubits for certain ansätze

- Under realistic noise, the same ansätze exhibit BPs at just 6-8 qubits [9]

- Each doubling of circuit depth can increase the BP effect by 1.5-2x in noisy environments

Q4: Can we genuinely "harness" quantum noise to improve training, or is mitigation the only option?

Emerging research indicates that under specific conditions, noise can be harnessed rather than merely mitigated. The HQNET framework demonstrates that custom Hermitian observables can transform noise into a beneficial regularization effect, creating cost landscapes that are more navigable despite being noisier [9]. This approach works by truncating the landscape in a way that preserves productive optimization pathways while eliminating deceptive minima. However, this noise-harnessing strategy is highly dependent on careful observable selection and problem structure.

Q5: How do I select between global and local cost functions for noisy hardware experiments?

The choice involves a fundamental trade-off between measurement efficiency and noise resilience [9] [7]:

Table: Global vs. Local Cost Function Comparison

| Factor | Global Cost Function | Local Cost Function |

|---|---|---|

| BP Onset | Earlier (6-8 qubits under noise) | Later (8-10+ qubits under noise) |

| Measurement Overhead | Lower (simultaneous readout) | Higher (sequential measurements) |

| Noise Resilience | Lower | Higher |

| Best Paired Observable | Custom Hermitian | PauliZ |

| Recommended Use Case | Shallow circuits (< 6 qubits) | Deeper circuits (6-10+ qubits) |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Measuring Noise Impact on Cost Landscape

Purpose: Quantitatively characterize how quantum noise distorts the cost function landscape for your specific variational algorithm and hardware platform.

Materials & Setup:

- Quantum processor or noise-aware simulator

- Parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz)

- Classical optimizer (Adam, SGD, or BFGS)

- Measurement observables (PauliZ, PauliX, PauliY, Custom Hermitian)

Procedure:

- Initialize your parameterized quantum circuit U(θ) with a structured initial guess θ₀

- Execute the circuit under both noise-free and noisy conditions:

- For hardware: Direct execution on quantum processor

- For simulation: Incorporate amplitude damping, phase damping, and gate noise models

- Measure the cost function C(θ) = ⟨ψ(θ)|H|ψ(θ)⟩ for your target Hamiltonian H

- Compute gradients using the parameter-shift rule: ∂C/∂θᵢ = [C(θᵢ+π/4) - C(θᵢ-π/4)]/2

- Characterize the landscape by evaluating C(θ) across a grid of parameter perturbations

- Quantify flatness using gradient variance and Hessian condition number

Analysis:

- Compare noise-free versus noisy gradient magnitudes

- Calculate the noise acceleration factor for BP onset

- Evaluate observable-dependent performance differences

Protocol: Observable Selection for Noise Resilience

Purpose: Identify the optimal measurement observable that maximizes convergence rate under noisy conditions for your specific problem.

Materials:

- Target Hamiltonian or cost function definition

- Set of candidate observables: PauliZ, PauliX, PauliY, Custom Hermitian

- Quantum hardware or noise-aware simulator

Procedure:

- Define your problem Hamiltonian and initial state

- Implement each candidate observable in the measurement basis

- Execute the variational optimization loop with fixed hyperparameters

- Track convergence metrics for each observable:

- Cost function value versus iteration

- Gradient variance across parameter space

- Final solution fidelity or accuracy

- Statistical analysis: Repeat each experiment 10+ times to account for stochastic noise

Interpretation:

- PauliZ typically outperforms others for local cost functions [9]

- Custom Hermitian observables may provide best results for global cost functions [9]

- PauliX and PauliY generally show poorest noise resilience except in specific problem contexts

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Essential Components for Noise-Aware Variational Algorithm Research

| Component | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Parameterized Quantum Circuits | Encodes solution space; balance expressibility and trainability | Hardware-efficient ansatz, QAOA ansatz, UCCSD [8] |

| Measurement Observables | Defines what physical quantity is measured; critical for noise resilience | PauliZ (most robust), PauliX, PauliY, Custom Hermitian [9] |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Reduces impact of hardware noise on measurements | ZNE, PEC, Dynamical Decoupling, Measurement Error Mitigation [11] |

| Classical Optimizers | Updates parameters to minimize cost function | Adam, SPSA, L-BFGS, Quantum Natural Gradient [8] |

| Noise Models | Simulates realistic hardware conditions for pre-testing | Amplitude damping, phase damping, depolarizing noise, thermal relaxation [7] |

| Cost Function Definitions | Quantifies solution quality; choice impacts BP susceptibility | Global (all qubits), Local (individual qubits) [9] [7] |

| Halomicin B | Halomicin B, CAS:54356-09-1, MF:C43H58N2O12, MW:794.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2H-benzotriazole-4-carboxylic acid | 2H-Benzotriazole-4-carboxylic acid|CAS 62972-61-6 |

Quantum noise in the NISQ era fundamentally reshapes cost function landscapes, but strategic approaches can maintain algorithm viability. The key insights for researchers addressing convergence issues in adaptive variational algorithms are:

- Observable selection is a powerful degree of freedom—PauliZ for local cost functions and custom Hermitian observables for global cost functions provide the strongest noise resilience [9]

- Error mitigation techniques like ZNE and PEC are essential bridges to quantum utility, reducing noise impact by 40-60% in current hardware [11]

- Landscape-aware training protocols that monitor gradient statistics and adapt optimization strategies can detect and respond to emerging barren plateaus [5]

For drug development researchers applying these methods to molecular simulation, the practical path forward involves: (1) implementing noise-aware benchmarking before full-scale experiments, (2) adopting a hybrid approach that combines multiple observables and error mitigation strategies, and (3) maintaining realistic expectations about current hardware capabilities while the field progresses toward fault-tolerant quantum computation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is the gradient measurement step in my adaptive VQE simulation so slow, and how can I reduce this overhead?

The gradient measurement step is a known bottleneck because it traditionally requires estimating energy gradients for every operator in a large pool, leading to a measurement cost that can scale as steeply as ( O(N^8) ) for a system with ( N ) spin-orbitals [12] [13]. This occurs because the commutator ( [\hat{H}, \hat{G}i] ) for each candidate generator ( \hat{G}i ) must be decomposed into a sum of measurable fragments, each of which requires many circuit evaluations to estimate its expectation value [13].

Solutions to reduce this overhead include:

- Commutating Observable Grouping: A robust strategy involves simultaneously measuring groups of commuting observables. This approach can significantly ameliorate the measurement overhead, reducing the scaling from ( O(N^8) ) to ( O(N^5) ) and making it only ( O(N) ) times as expensive as a naive VQE iteration [12].

- Best-Arm Identification (BAI): Reformulate the generator selection as a Best-Arm Identification problem. Algorithms like Successive Elimination (SE) adaptively allocate measurements and quickly discard operators with small gradients, concentrating resources on the most promising candidates and drastically reducing the total number of measurements [13].

- Reduced Density Matrices (RDMs): For specific operator pools (e.g., containing single and double excitations), gradients can be expressed using reduced density matrices. By approximating higher-order RDMs with lower-order ones, the measurement cost can be reduced from ( O(N^8) ) to ( O(N^4) ) [13].

FAQ 2: My ADAPT-VQE optimization is stagnating at a high energy. Is this due to hardware noise or a flawed ansatz?

Stagnation can be attributed to several factors, including hardware noise and statistical sampling noise, but also fundamental algorithmic issues related to the operator pool and optimization landscape.

- Statistical Noise: Noisy measurement outcomes (e.g., with 10,000 shots) can prevent the algorithm from accurately identifying the best generator or optimizing parameters, causing it to plateau well above the chemical accuracy threshold [1].

- Hardware Noise: Noise on current Quantum Processing Units (QPUs) can produce inaccurate energy evaluations. However, the parameterized circuit constructed may still encode a favorable ground-state approximation, which can be verified through noiseless emulation of the final ansatz [1].

- Local Optima and Singular Points: The convergence of VQE is not guaranteed for all ansätze. If the parameterized unitary transformation ( U(\bm{\theta}) ) does not allow for moving in all tangent-space directions (a property known as local surjectivity), the optimization can get stuck at suboptimal solutions, known as singular points [5].

FAQ 3: How can I make the operator selection process more efficient without sacrificing the accuracy of the final ansatz?

Efficiency in operator selection can be dramatically improved by moving beyond the method of measuring all gradients to a fixed precision.

- Successive Elimination Algorithm: This BAI strategy involves running multiple rounds of measurement. In each round, gradients of the active operator set are estimated with a progressively tighter precision. Operators whose gradient estimates (plus a confidence interval) are definitively worse than the current best are eliminated early, focusing the measurement budget on a narrowing set of promising candidates [13].

- Gradient-Free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE): To circumvent the gradient measurement problem entirely, you can employ gradient-free analytic optimization methods. These algorithms demonstrate improved resilience to statistical sampling noise and can be executed directly on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices [1].

- Information Recycling: Exploit correlations between successive iterations. Since commutator decompositions often share measurable fragments with the Hamiltonian itself, measurement data from the VQE subroutine can be reused in subsequent gradient evaluations, reducing unnecessary sampling [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Prohibitively High Measurement Cost in Gradient Estimation

Diagnosis: The classical method of measuring the energy gradient for every operator in the pool is intractable for relevant system sizes.

Resolution:

- Implement Commutator Grouping: Use a strategy like qubit-wise commuting (QWC) fragmentation with a sorted insertion (SI) grouping strategy to minimize the number of distinct measurement circuits [13].

- Apply Best-Arm Identification: Integrate the Successive Elimination algorithm into your ADAPT-VQE workflow. The protocol is as follows [13]: a. Initialization: Begin with the current ansatz state ( |\psik\rangle ) and the full operator pool ( A0 = \mathcal{A} ). b. Adaptive Rounds: For each round ( r ), estimate the gradient ( gi ) for every operator in the current active set ( Ar ) with a precision ( \epsilonr ). c. Elimination: Calculate the maximum gradient magnitude ( M ) in ( Ar ). Eliminate all generators ( \hat{G}i ) for which ( |gi| + Rr < M - Rr ), where ( R_r ) is a confidence interval. d. Termination: Repeat until one candidate remains or a maximum number of rounds is reached. In the final round, ensure the gradient is estimated to the target accuracy.

Experimental Protocol: Successive Elimination for Generator Selection

- Objective: Identify the generator ( \hat{G}M ) with the largest energy gradient ( |gi| ) using a minimal number of measurements.

- Procedure:

- Input: Ansatz state ( |\psik\rangle ), operator pool ( \mathcal{A} ), target precision ( \epsilon ), round constants ( cr ), ( dr ), max rounds ( L ).

- Initialize active set ( A0 = \mathcal{A} ).

- For round ( r = 0 ) to ( L ):

- For each ( \hat{G}i \in Ar ):

- Decompose ( [\hat{H}, \hat{G}i] ) into measurable fragments ( \sum{n} \hat{A}{n}^{(i)} ) [13].

- Allocate a measurement budget based on precision ( \epsilonr = cr \cdot \epsilon ) to estimate ( \langle \hat{A}{n}^{(i)} \rangle ) for all fragments.

- Compute gradient estimate ( gi = \sum{n} \langle \hat{A}{n}^{(i)} \rangle ).

- Find ( M = \max{i \in Ar} |gi| ).

- Eliminate all ( \hat{G}i ) satisfying ( |gi| + Rr < M - Rr ), where ( Rr = dr \cdot \epsilonr ).

- If ( |Ar| = 1 ), break.

- For each ( \hat{G}i \in Ar ):

- Output: The generator with the largest gradient in the final active set.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the Successive Elimination process:

Problem: Convergence Stagnation Due to Statistical or Hardware Noise

Diagnosis: The algorithm fails to lower the energy because gradient estimates are corrupted by noise, or the optimizer is trapped.

Resolution:

- Switch to a Gradient-Free Algorithm: Implement Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE). This method uses analytic, gradient-free optimization for the parameter updates, which has been shown to be more resilient to statistical noise and can be run on a noisy QPU [1].

- Verify Ansatz on a Classical Emulator: After running on a QPU, retrieve the final parameterized circuit and evaluate the resulting ansatz wave-function using noiseless emulation (hybrid observable measurement) to check if a good state was prepared despite hardware inaccuracies [1].

- Analyze the Optimization Landscape: Ensure your ansatz construction does not introduce singular points that trap the optimizer. Theoretical work shows that convergence to a ground state is almost sure if the parameterized unitary allows for moving in all tangent-space directions (local surjectivity) and the gradient descent terminates [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Gradient Estimation Strategies in Adaptive VQE

| Strategy | Key Principle | Reported Measurement Scaling | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage/Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve Measurement [12] [13] | Measure each operator's gradient to fixed precision. | ( O(N^8) ) | Simple to implement. | Becomes rapidly intractable for larger systems. |

| Commutator Grouping [12] | Simultaneously measure commuting observables. | ( O(N^5) ) | Significant constant-factor and scaling reduction. | Requires careful grouping of operators. |

| RDM-Based Methods [13] | Express gradients via reduced density matrices. | ( O(N^4) ) | Leverages problem structure for better scaling. | Limited to specific operator pools (e.g., excitations). |

| Successive Elimination (BAI) [13] | Adaptively allocate shots and eliminate weak candidates early. | Context-dependent; reduces total number of measurements. | Avoids wasting shots on poor operators. | Introduces complexity in adaptive shot allocation. |

| Gradient-Free GGA-VQE [1] | Uses analytic, gradient-free optimization. | Avoids gradient measurement entirely. | Improved resilience to statistical noise. | Relies on the effectiveness of the gradient-free optimizer. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential "Reagent Solutions" for Adaptive Variational Algorithm Research

| Research Reagent | Function / Role | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Qubit-Wise Commuting (QWC) Fragmentation [13] | Groups Hamiltonian terms into measurable sets. | Allows multiple terms in the commutator ( [\hat{H}, \hat{G}_i] ) to be measured in a single quantum circuit, reducing the total number of circuit evaluations required. |

| Operator Pool (( \mathcal{A} )) [13] | A pre-selected set of parameterized unitary generators. | Provides the building blocks for the adaptive ansatz. A well-chosen pool (e.g., one that preserves symmetries) is crucial for convergence and accuracy. |

| Successive Elimination Algorithm [13] | A Best-Arm Identification (BAI) solver. | Manages finite measurement budgets by strategically allocating shots to identify the best generator with high confidence and minimal resources. |

| Reduced Density Matrices (RDMs) [13] | Encodes information about a subsystem of a larger quantum state. | For certain pools, provides an alternative, more efficient pathway to compute energy gradients without directly measuring the full commutator. |

| Noiseless Emulator [1] | A classical simulator of a quantum computer. | Used to verify the quality of an ansatz wave-function generated on a noisy QPU, decoupling algorithmic performance from hardware-specific errors. |

| Isolinderalactone | Isolinderalactone, MF:C15H16O3, MW:244.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dehydrocurdione | Dehydrocurdione, CAS:38230-32-9, MF:C15H22O2, MW:234.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Impact of Statistical Sampling Noise on Convergence Stability

FAQs: Understanding Sampling Noise in Adaptive Variational Algorithms

1. What is statistical sampling noise and how does it affect my variational algorithm's convergence?

Statistical sampling noise refers to the inherent variability in cost function estimates that arises from using a finite number of measurements or samples. In variational algorithms, this noise distorts the perceived optimization landscape, creating false minima and statistical biases known as the "winner's curse" where the best-performing parameters in a noisy evaluation often appear better than they truly are [14]. This phenomenon severely challenges optimization by misleading gradient-based methods and can prevent algorithms from finding true optimal parameters.

2. Why do my gradient-based optimizers (BFGS, SLSQP) struggle with noisy cost functions?

Gradient-based methods are highly sensitive to noise because they rely on accurate estimations of the local landscape geometry. Sampling noise introduces inaccuracies in both function values and gradient calculations, causing these optimizers to diverge or stagnate as they follow misleading descent directions [14]. The noise creates a distorted perception of curvature information that undermines the fundamental assumptions of these methods.

3. Can noise ever be beneficial for variational algorithm convergence?

Under specific conditions, carefully controlled noise can actually help optimization escape saddle points in high-dimensional landscapes [15]. This occurs through a mechanism where noise perturbs parameters sufficiently to move away from problematic regions surrounded by high-error plateaus. However, this beneficial effect requires the noise structure to satisfy specific mathematical conditions and is distinct from the generally detrimental effects of uncontrolled sampling noise.

4. What practical strategies can mitigate sampling noise effects in my experiments?

Effective approaches include: using population-based optimizers that track population means rather than individual performance to counter statistical bias; employing adaptive metaheuristics like CMA-ES and iL-SHADE that automatically adjust to noisy conditions; and implementing co-design of physically motivated ansatzes that are inherently more resilient to noise [14]. These methods directly address the distortion caused by finite-shot sampling.

Troubleshooting Guide: Sampling Noise Issues

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm stagnation at suboptimal parameters | False minima created by noise distortion [14] | Compare results across multiple random seeds; evaluate cost function with increased samples | Switch to adaptive metaheuristics (CMA-ES, iL-SHADE) [14] |

| Erratic convergence with large performance fluctuations | High-variance gradient estimates from insufficient sampling [14] | Monitor gradient consistency across iterations; calculate variance of cost estimates | Implement gradient averaging; increase sample size per evaluation; use adaptive batch sizes |

| Inconsistent results between algorithm runs | Winner's curse bias in parameter selection [14] | Track population statistics rather than just best performer | Use population-based approaches that track mean performance [14] |

| Poor generalization from simulation to hardware | Noise characteristics mismatch between environments [16] | Characterize noise profiles in both environments; test noise resilience | Employ noise-aware optimization; use domain adaptation techniques |

Experimental Protocols for Noise Characterization

Protocol 1: Quantifying Sampling Noise Impact

Objective: Measure how statistical sampling noise affects convergence stability in variational quantum algorithms.

Materials:

- Quantum chemistry Hamiltonians (Hâ‚‚, Hâ‚„, LiH)

- Truncated Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz

- Classical optimizers: SLSQP, BFGS, CMA-ES, iL-SHADE

- Quantum simulation environment with noise injection capability

Methodology:

- Initialize variational algorithm with identical parameters across multiple runs

- For each evaluation, use finite-shot measurements (100-1000 shots) to simulate sampling noise

- Benchmark eight classical optimizers spanning gradient-based, gradient-free, and metaheuristic methods

- Record convergence trajectories, final parameters, and achieved accuracy

- Compare against noise-free baseline to quantify noise-induced performance degradation

Expected Outcomes: Gradient-based methods will show divergence or stagnation under noise, while adaptive metaheuristics will demonstrate superior resilience with convergence rates 20-30% higher in noisy conditions [14].

Protocol 2: Noise Resilience Testing for Optimizer Selection

Objective: Systematically evaluate optimizer performance under controlled noise conditions.

Materials:

- Hardware-efficient ansatz circuits

- Condensed matter models

- Noise injection framework

- Performance metrics: convergence probability, iteration count, final accuracy

Methodology:

- Implement multiple optimizer classes: gradient-based (SLSQP, BFGS), gradient-free, and metaheuristic (CMA-ES, iL-SHADE)

- Apply controlled Gaussian noise with varying standard deviations (0.01-0.5) of parameter space

- For each condition, run 50 independent optimizations from different initial points

- Measure success rate, convergence speed, and solution quality

- Analyze correlation between noise levels and performance metrics

Expected Outcomes: Adaptive metaheuristics will maintain 70-80% success rates under moderate noise, while gradient-based methods may drop below 30% success as noise increases [14].

Quantitative Analysis of Noise Effects

Table: Optimizer Performance Under Sampling Noise (Quantum Chemistry Problems)

| Optimizer Class | Specific Algorithm | Success Rate (Noiseless) | Success Rate (Noisy) | Relative Convergence Speed | Noise Resilience Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-based | SLSQP | 92% | 28% | 1.0× | Low |

| Gradient-based | BFGS | 95% | 31% | 1.2× | Low |

| Population-based | CMA-ES | 88% | 76% | 0.8× | High |

| Population-based | iL-SHADE | 90% | 79% | 0.9× | High |

| Evolutionary Strategy | (Various) | 85% | 72% | 0.7× | Medium-High |

Table: Effects of Different Noise Types on Convergence Stability

| Noise Type | Source | Impact on Convergence | Mitigation Strategy | Experimental Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical sampling noise | Finite-shot measurement [14] | Creates false minima, winner's curse bias | Increase samples; population-based methods | Performance variance across identical runs |

| Measurement noise | Instrumentation limitations [17] | Obscures true signal, reduces SNR | Signal averaging; improved measurement design | Deviation from theoretical limits |

| Parameter noise | Control imprecision [16] | Perturbs optimization trajectory | Robust control protocols; noise-aware optimization | Systematic errors in implementation |

| Environmental noise | Decoherence, interference [18] | Causes drift, reduces fidelity | Error correction; dynamical decoupling | Time-dependent performance degradation |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Noise Resilience Studies

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES Optimizer | Evolutionary strategy for noisy optimization [14] | Variational algorithm convergence under sampling noise | Adaptive covariance matrix; population-based sampling |

| Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz | Problem-inspired parameterized circuit [14] | Quantum chemistry applications (Hâ‚‚, Hâ‚„, LiH) | Physical constraints built-in; reduced parameter space |

| Pauli Channel Models | Structured noise representation [16] | Realistic noise simulation in quantum circuits | Physically motivated error channels; experimental validation |

| Noise Injection Framework | Controlled introduction of synthetic noise [18] | Systematic resilience testing | Tunable noise parameters; reproducible conditions |

| Hidden Markov Model Analysis | Statistical inference of underlying states [19] | Detecting diffusive states in single-particle tracking | Handles heterogeneous localization errors; missing data |

| Aloesone | Aloesone, CAS:40738-40-7, MF:C13H12O4, MW:232.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Lbapt | Lbapt Research Compound | Lbapt is a high-purity research compound for biochemical studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Diagnostic Diagram: Noise Impact on Convergence

Comparative Analysis of Fixed vs. Adaptive Ansatz Structures

In the field of quantum computational chemistry, variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) have emerged as promising approaches for solving electronic structure problems on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. The core component of these algorithms is the ansatz—a parameterized quantum circuit that prepares trial wave-functions approximating the ground or excited states of molecular systems. The choice between fixed and adaptive ansatz structures represents a critical design decision with significant implications for algorithmic performance, resource requirements, and convergence behavior. This technical support center article examines both approaches within the context of ongoing research on convergence issues in adaptive variational algorithms, providing troubleshooting guidance and methodological support for researchers investigating molecular systems for drug development applications.

Fixed ansatz structures employ predetermined quantum circuits with a fixed configuration of parameterized gates, while adaptive ansatze dynamically construct quantum circuits during the optimization process using feedback from classical processing. The comparative analysis reveals fundamental trade-offs: fixed ansatze offer predictable resource requirements but may lack expressibility for complex systems, whereas adaptive methods can generate more compact, system-tailored circuits but introduce convergence challenges including energy plateaus and local minima trapping.

Fundamental Concepts: Fixed vs. Adaptive Ansatze

Fixed Ansatz Structures

Fixed ansatz structures implement quantum circuits with predetermined gate arrangements and fixed connectivity patterns. Common examples include the Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) ansatz and hardware-efficient ansatze that prioritize experimental feasibility. These approaches maintain a static circuit architecture throughout the optimization process, with only the rotational parameters of the gates being variationally updated.

Key Characteristics:

- Predictable Resource Requirements: Quantum circuit depth and gate counts are known prior to execution

- Deterministic Implementation: Circuit structure remains identical across multiple algorithm executions

- Transferability: Successful ansatz configurations can be applied to related molecular systems

- Limited Expressibility: Predefined circuits may not efficiently capture strong correlation effects in certain molecular systems

Adaptive Ansatz Structures

Adaptive ansatze dynamically construct quantum circuits by iteratively adding gates based on system-specific criteria. The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter (ADAPT-VQE) algorithm has emerged as a gold-standard method that generates compact, problem-tailored ansatze [20]. These methods utilize classical processing to determine optimal circuit expansions that maximize improvement in wave-function quality at each iteration.

Key Characteristics:

- Dynamic Circuit Construction: Circuit architecture evolves during the optimization process

- System Tailoring: Ansatz structure adapts to specific Hamiltonian characteristics

- Compact Representation: Typically achieves accurate results with fewer parameters than fixed approaches

- Convergence Vulnerabilities: Prone to energy plateaus and local minima trapping

Comparative Analysis: Performance Metrics and Convergence Behavior

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Fixed vs. Adaptive Ansatz Structures

| Characteristic | Fixed Ansatz | Adaptive Ansatz (ADAPT-VQE) | Overlap-ADAPT-VQE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit Construction | Predetermined structure | Iterative, greedy construction | Overlap-guided iterative construction |

| Convergence Reliability | Consistent but potentially to wrong state | Prone to plateaus in strongly correlated systems | Improved through target overlap maximization |

| Resource Requirements | Fixed depth, potentially high for accuracy | Variable, can become deep in plateaus | Significant depth reduction demonstrated |

| Parameter Optimization | Classical optimization of fixed parameters | Classical optimization with circuit growth | Two-phase: overlap maximization then energy optimization |

| Molecular Applicability | Suitable for weak correlation | General but hampered by plateaus | Enhanced for strong correlation |

| Implementation Complexity | Lower | Moderate | Higher due to target wave-function requirement |

Convergence Issues in Adaptive Variational Algorithms

Convergence problems represent the most significant challenge in adaptive ansatz approaches, primarily manifesting as:

- Energy Plateaus: Extended iterations with minimal energy improvement, particularly problematic in strongly correlated systems [20]

- Local Minima Trapping: Optimization converges to suboptimal solutions due to nonconvex optimization landscapes [5]

- Circuit Depth Explosion: Prolonged plateau regions necessitate increasingly deep quantum circuits [20]

- Singular Control Points: Parameterizations where local surjectivity breaks down, creating convergence barriers [5]

The fundamental convergence challenge stems from the complex, nonconvex optimization landscape where the existence of local optima can hinder the search for global solutions [5]. Theoretical analysis shows that convergence to a ground state can be guaranteed only when: (i) the parameterized unitary transformation allows moving in all tangent-space directions (local surjectivity) in a bounded manner, and (ii) the gradient descent used for parameter update terminates [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Convergence Issues and Solutions

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our ADAPT-VQE simulation has stalled in an energy plateau for over 50 iterations. What strategies can help escape this local minimum?

A: Energy plateaus indicate insufficient gradient information for productive circuit growth. Implement the following protocol:

- Overlap-Guided Restart: Employ Overlap-ADAPT-VQE using a high-quality target wave-function (e.g., from selected CI calculations) to reinitialize the optimization [20]

- Gradient Analysis: Monitor the gradient norms of candidate operators—persistently small values across multiple operators confirm true plateau conditions

- Symmetry Exploitation: Leverage molecular point group symmetries to restrict the operator pool to symmetry-adapted operators, reducing the search space

- Termination Criteria: Implement practical termination triggers when gradient norms remain below threshold ε for k consecutive iterations

Q2: How can we balance circuit depth requirements with accuracy in adaptive approaches for NISQ devices?

A: Circuit depth limitations represent critical constraints for NISQ implementations. Apply these techniques:

- Overlap-ADAPT Protocol: Numerical experiments demonstrate 3x circuit depth reduction for H6 systems while maintaining chemical accuracy [20]

- Iteration Batching: Group multiple operators added during plateau regions and reoptimize subsets to identify redundant components

- Hybrid Approach: Use compact Overlap-ADAPT-generated ansatze as high-accuracy initializations for fixed-ansatz VQE refinements [20]

- Error-Aware Optimization: Incorporate hardware-specific error models into the operator selection criteria to prioritize noise-resilient structures

Q3: What guarantees exist for convergence of variational quantum eigensolvers with adaptive ansatze?

A: Theoretical convergence guarantees require specific conditions:

- Local Surjectivity: The parameterized unitary must allow movement in all tangent-space directions [5]

- Termination Assurance: Gradient descent optimization must be guaranteed to terminate [5]

- Singular Point Avoidance: Parameterizations must avoid singular controls where local surjectivity breaks down [5]

In practice, these conditions are challenging to satisfy completely. The ð•Šð•Œ(d)-gate ansatz and product-of-exponentials ansatz always contain singular points regardless of overparameterization [5]. Recent constructions with M=2(d²−1) or M=d² parameters can satisfy local surjectivity but introduce potential non-termination issues [5].

Q4: Can adaptive ansatze compute excited states in addition to ground states?

A: Yes, the ADAPT-VQE convergence path enables excited state calculations through quantum subspace diagonalization. This approach:

- Utilizes Intermediate States: Selects states from the ADAPT-VQE convergence path toward the ground state [21]

- Quantum Subspace Diagonalization: Diagonalizes the Hamiltonian in the subspace spanned by these selected states [21]

- Minimal Resource Overhead: Requires only small additional quantum resources beyond ground state calculation [21]

- Broad Applicability: Successfully demonstrated for nuclear pairing problems and H4 molecule dissociation [21]

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard ADAPT-VQE Implementation Protocol

Objective: Prepare accurate ground state wave-functions for molecular systems using adaptive ansatz construction.

Materials and Computational Resources:

- Quantum Simulator/Device: Statevector simulator for proof-of-concept studies [20]

- Classical Optimizer: Gradient-based optimization routines (e.g., BFGS, Adam)

- Operator Pool: Chemically inspired operators (fermionic or qubit excitations) [20]

- Initial State: Typically Hartree-Fock reference wave-function

Procedure:

- Initialization:

- Prepare reference state |ψ₀⟩ (usually Hartree-Fock)

- Define operator pool {A_i} relevant to molecular system

Iterative Growth Cycle:

- For iteration k = 1 to Nmax: a. Gradient Calculation: Compute ∂E/∂θi for all operators in pool b. Operator Selection: Identify operator Ak with largest |∂E/∂θi| c. Circuit Appending: Add exp(θkAk) to quantum circuit d. Parameter Optimization: Reoptimize all parameters {θâ‚,...,θ_k} e. Convergence Check: If |ΔE| < ε, terminate; else continue

Output:

- Final energy E_final

- Optimal parameters {θ_i}

- Final circuit structure

Troubleshooting Notes:

- For prolonged plateaus (>20 iterations without improvement), consider restarting with overlap-guided approach [20]

- Monitor gradient norms to distinguish true convergence from stalling

- For NISQ implementation, incorporate hardware topology constraints in operator selection

Overlap-ADAPT-VQE Protocol for Strongly Correlated Systems

Objective: Generate compact ansatze for strongly correlated molecules where standard ADAPT-VQE exhibits plateau behavior.

Materials and Computational Resources:

- Target Wave-function: High-quality approximation from classical method (e.g., CIPSI) [20]

- Quantum Simulator: Statevector capability for overlap calculations

- Classical Computer: For overlap maximization and intermediate processing

Procedure:

- Target Generation:

- Perform selected CI calculation (e.g., CIPSI) to generate target wave-function |Ψ_target⟩ [20]

- Alternatively, use other high-quality wave-function from classical methods

Overlap Maximization Phase:

- For iteration k = 1 to Noverlap: a. Overlap Gradient: Compute ∂/∂θi |⟨Ψ(θ)|Ψ_target⟩|² for all pool operators b. Operator Selection: Choose operator that maximizes overlap increase c. Circuit Growth: Add selected operator to circuit d. Parameter Optimization: Optimize parameters to maximize overlap with target

Energy Optimization Phase:

- Use overlap-optimized circuit as initial ansatz for standard ADAPT-VQE

- Continue iterative growth with energy-based gradient selection

- Terminate when chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa) is achieved

Validation Data:

- For stretched linear H6 chain: Overlap-ADAPT achieves chemical accuracy in ~50 iterations vs. >150 iterations for standard ADAPT-VQE [20]

- Significant circuit depth reduction observed across benchmark molecules, particularly for strong correlation regimes [20]

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table 2: Key Research Components for Ansatz Development Experiments

| Research Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pools | Provides building blocks for adaptive circuit construction | Qubit excitation operators, Fermionic excitation operators, Hardware-native gates |

| Classical Optimizers | Updates variational parameters to minimize energy | Gradient descent, BFGS, CMA-ES, Quantum natural gradient |

| Target Wave-functions | Guides compact ansatz construction in overlap-based methods | CIPSI wave-functions, DMRG states, Full CI references for small systems |

| Convergence Metrics | Monitors algorithm progress and detects stalling | Energy gradients, Overlap measures, Variance of energy |

| Quantum Subspace Methods | Computes excited states from ground state optimization path | Quantum subspace diagonalization using ADAPT-VQE intermediate states [21] |

Workflow Visualization: Adaptive Ansatz Construction

ADAPT-VQE Workflow with Plateau Remediation

Convergence Theory and Landscape Analysis

Theoretical Foundations of VQE Convergence

The convergence of variational quantum eigensolvers depends critically on the structure of the underlying optimization landscape. Theoretical analysis reveals that:

- Quantum Control Landscapes: VQEs can be framed as quantum optimal control problems at the circuit level [5]

- Local Surjectivity Condition: Convergence to ground state occurs when the parameterized unitary transformation allows movement in all tangent-space directions [5]

- Singular Point Existence: Both ð•Šð•Œ(d)-gate ansatz and product-of-exponentials ansatz contain singular points where local surjectivity breaks down, regardless of overparameterization [5]

- Strict Saddle Points: When local surjectivity is satisfied, suboptimal solutions correspond to strict saddle points that gradient descent avoids almost surely [5]

Convergence Diagnostics and Monitoring

Effective convergence monitoring requires tracking multiple metrics simultaneously:

- Energy Progression: Primary convergence metric, but insufficient alone

- Gradient Norms: Critical for detecting true plateaus versus slow convergence

- Parameter Updates: Magnitude of parameter changes indicates optimization activity

- Wave-function Overlap: Measures progress toward target states when available

- Variance of Energy: Indicators of state quality and convergence stability

Implementation of comprehensive monitoring enables early detection of convergence issues and informed intervention decisions, particularly when employing adaptive ansatz structures where circuit growth represents significant computational investment.

The comparative analysis of fixed versus adaptive ansatz structures reveals a complex trade-space between computational efficiency, convergence reliability, and implementation practicality. Fixed ansatze provide predictable performance but may require excessive circuit depths for accurate modeling of strongly correlated systems relevant to drug development. Adaptive approaches, particularly ADAPT-VQE and its variants, offer compact circuit representations but introduce convergence challenges including energy plateaus and local minima trapping.

The emerging methodology of Overlap-ADAPT-VQE represents a promising direction, addressing key convergence issues through overlap-guided ansatz construction and demonstrating significant circuit depth reductions—up to 3x improvement for challenging systems like stretched H6 chains [20]. Theoretical advances in understanding quantum control landscapes provide foundations for developing more robust parameterizations that satisfy local surjectivity conditions [5].

For researchers investigating molecular systems for drug development applications, hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both paradigms may offer the most practical path forward: using adaptive methods to generate compact, system-tailored initial ansatze, then applying fixed-structure optimization for refinement and production calculations. As quantum hardware continues to advance, reducing noise and increasing coherence times, these algorithmic improvements will play a critical role in enabling practical quantum computational chemistry for pharmaceutical research.

Algorithmic Innovations and Real-World Applications in Quantum-Enhanced Drug Research

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of GGA-VQE over standard ADAPT-VQE? GGA-VQE (Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE) significantly reduces the quantum resource requirements compared to standard ADAPT-VQE. While ADAPT-VQE requires measuring the gradients for all operators in the pool at each step—a process that demands a large number of circuit evaluations—GGA-VQE selects and optimizes operators in a single step by fitting the energy expectation curve. This reduces the number of circuit measurements per iteration to just a few, making it more practical for Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices [22] [23].

Q2: My HPC-Net model is converging slowly during training. What could be the cause? Slow convergence in HPC-Net can often be traced to the feature extraction components. The network is designed with a Depth Accelerated Convergence Convolution (DACConv) module specifically to address this issue. Ensure that this module is correctly implemented, as it employs two convolution strategies (per input feature map and per input channel) to maintain feature extraction ability while significantly accelerating convergence speed [24].

Q3: What is a "convergence shortcut" in the context of adaptive algorithms, and should I be concerned about it? A "convergence shortcut" refers to the practice of integrating diverse knowledge topics (cross-topic exploration) without the corresponding integration of appropriate disciplinary expertise (cross-disciplinary collaboration). Research has shown that while this approach is growing in prevalence, the classic "full convergence" that combines both cross-topic and cross-disciplinary modes yields a significant citation impact premium (approximately 16% higher). For high-impact research, especially when integrating distant knowledge domains, the cross-disciplinary mode is essential [25].

Q4: How does the gCANS method improve the performance of Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs)? The global Coupled Adaptive Number of Shots (gCANS) method is a stochastic gradient descent approach that adaptively allocates the number of measurement shots at each optimization step. It improves upon prior methods by reducing both the number of iterations and the total number of shots required for convergence. This directly reduces the time and financial cost of running VQAs on cloud quantum platforms. It has been proven to achieve geometric convergence in a convex setting and performs favorably compared to other optimizers in problems like finding molecular ground states [26].

Q5: The detection accuracy for occluded objects in my model is low. How can HPC-Net help? HPC-Net addresses this specific challenge with its Multi-Scale Extended Receptive Field Feature Extraction Module (MEFEM). This module enhances the detection of heavily occluded or truncated 3D objects by expanding the receptive field of the convolution and integrating multi-scale feature maps. This allows the network to capture more contextual information, significantly improving accuracy in hard detection modes. On the KITTI dataset, HPC-Net achieved top ranking in hard mode for 3D object detection [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: GGA-VQE Convergence Problems or Inaccurate Ground State Energy

Problem: The GGA-VQE algorithm is not converging to the expected ground state energy, or the convergence is unstable.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Symptoms | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware Noise and Shot Noise | Inaccurate energies, even with the correct ansatz wave-function when run on a QPU. | Compare energy evaluation from a noiseless emulator with results from the actual QPU [23]. | Use error mitigation techniques. For final evaluation, retrieve the parameterized circuit from the QPU and compute the energy expectation value using a noiseless emulator (hybrid observable measurement) [23]. |

| Insufficient Operator Pool | The algorithm plateaus at a high energy, unable to lower the cost function further. | Check if the gradients for all operators in the pool have converged to near zero. | Review the composition of the operator pool. Ensure it is chemically relevant and complete enough to express the ground state. For quantum chemistry, common pools are based on unitary coupled cluster (UCC)-type excitations [6]. |

| Fitting with Too Few Shots | High variance in the fitted energy curves, leading to poor operator selection. | Observe the stability of the fitted trigonometric curves for each candidate operator. | Increase the number of shots per candidate operator during the curve-fitting step to obtain a more reliable estimate, balancing the trade-off with computational cost [22]. |

Recommended Experimental Protocol for GGA-VQE [23] [6]:

- Initialize: Prepare the Hartree-Fock reference state on the quantum computer.

- Build Ansatz Iteratively: a. Candidate Evaluation: For each parameterized gate in the operator pool, compute its energy expectation value at a few (e.g., 3-5) different parameter values (angles). b. Curve Fitting: Fit a simple trigonometric function to the energy vs. angle data for each candidate. c. Operator Selection: Find the minimum energy and the corresponding angle for each candidate's fitted curve. Select the operator that gives the overall lowest energy. d. Circuit Update: Append the selected operator, with its optimal angle fixed, to the quantum circuit.

- Check for Convergence: Repeat steps a-d until the largest gradient (or the energy improvement) falls below a predefined threshold.

The following diagram illustrates the iterative workflow of the GGA-VQE algorithm:

Issue 2: HPC-Net Training Instability or Suboptimal Object Detection Performance

Problem: The HPC-Net model for object detection exhibits unstable training or fails to achieve the expected accuracy on benchmark datasets like KITTI.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Symptoms | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ineffective Pooling | Poor generalizability, robustness, and detection speed. | Compare performance (accuracy, speed) using different pooling methods (e.g., max, average) in the Replaceable Pooling (RP) module. | Leverage the Replaceable Pooling (RP) module's flexibility. Experiment with different pooling methods on both 3D voxels and 2D BEV images to find the optimal one for your specific task and data [24]. |

| Poor Feature Extraction for Occluded Objects | Low accuracy specifically in "hard" mode with heavily occluded objects. | Inspect the performance breakdown by difficulty mode (easy, moderate, hard) on the KITTI benchmark. | Ensure the Multi-Scale Extended Receptive Field Feature Extraction Module (MEFEM) is correctly implemented. This module uses Expanding Area Convolution and multi-scale feature fusion to capture more context for occluded objects [24]. |

| Suboptimal Convergence Speed | Training takes an excessively long time to converge. | Profile the training time per epoch and monitor the loss convergence curve. | Verify the implementation of the Depth Accelerated Convergence Convolution (DACConv). This component is designed to maintain accuracy while using convolution strategies that speed up training convergence [24]. |

Recommended Experimental Protocol for HPC-Net Evaluation [24]:

- Data Preparation: Preprocess the point cloud data (e.g., from KITTI dataset) into 3D voxels.

- Model Configuration:

- Backbone: Employ the 3D backbone network with the DACConv layers for fast convergence.

- Pooling: Use the Replaceable Pooling (RP) module to compress features along the Z-axis, generating a 2D Bird's Eye View (BEV) image.

- Feature Enhancement: Route the features through the MEFEM to expand the receptive field and perform multi-scale fusion.

- Training: Train the model end-to-end, monitoring loss and accuracy on the validation set for all difficulty levels.

- Evaluation: Evaluate the model on the test set, focusing on the standard average precision (AP) metrics for 2D and 3D object detection across easy, moderate, and hard modes.

The architecture and data flow of HPC-Net can be visualized as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key computational tools and components used in the implementation of GGA-VQE and HPC-Net methods.

| Item Name | Function / Role | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ADAPT-VQE Operator Pool | A pre-defined set of parameterized unitary operators (e.g., UCCSD single and double excitations) from which the ansatz is built. | GGA-VQE: Provides the candidate gates for the adaptive selection process. A chemically relevant pool is crucial for accurately approximating molecular ground states [6]. |

PennyLane AdaptiveOptimizer |

A software tool that automates the adaptive circuit construction process by managing gradient calculations, operator selection, and circuit growth. | GGA-VQE: Used to implement the adaptive algorithm, build the quantum circuit, and optimize the gate parameters iteratively [6]. |

| Replaceable Pooling (RP) Module | A neural network layer that performs pooling operations on 3D voxels and 2D BEV images, designed to be flexibly swapped with different pooling methods. | HPC-Net: Enhances detection accuracy, speed, robustness, and generalizability by compressing feature dimensions and allowing for task-specific optimization [24]. |

| DACConv (Depth Accelerated Convergence Convolution) | A custom convolutional layer that employs strategies of convolving per input feature map and per input channel. | HPC-Net: Maintains high feature extraction capability while significantly accelerating the training convergence speed of the object detection model [24]. |

| MEFEM (Multi-Scale Extended Receptive Field Feature Extraction Module) | A module comprising Expanding Area Convolution and a multi-scale feature fusion network. | HPC-Net: Addresses the challenge of low detection accuracy for heavily occluded 3D objects by capturing broader context and integrating features at different scales [24]. |

| gCANS Optimizer | A classical stochastic gradient descent optimizer that adaptively allocates the number of quantum measurement shots per optimization step. | VQAs in general: Reduces the total number of shots and iterations required for convergence, lowering the time and cost of experiments on quantum cloud platforms [26]. |

| Hazaleamide | Hazaleamide|CAS 81427-15-8|Research Compound | Hazaleamide, a natural alkamide from Rutaceae plants. Research its antimalarial and pungent properties. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Hmetd | HMETD (55675-00-8)|High-Purity Research Compound |

Quantum Resource Requirements for Multi-Orbital Impurity Models

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary quantum resource bottleneck when using adaptive variational algorithms as impurity solvers?

The dominant bottleneck is the prohibitively high measurement cost during the generator selection step. For multi-orbital models, estimating energy gradients for each operator in a large pool can scale as steeply as ð’ª(Nâ¸) with the number of spin-orbitals N, making it the primary constraint on near-term devices [13] [27].

FAQ 2: How does the structure of a multi-orbital impurity model influence quantum circuit design?

These models feature a small, strongly correlated impurity cluster coupled to a larger, non-interacting bath. This structure can be leveraged to optimize circuits. The ground state can often be efficiently represented by a superposition of Gaussian states (SGS). Furthermore, circuit compression algorithms can reduce the gate count per Trotter step from ð’ª(Nq²) to ð’ª(NI × Nq), where Nq is the number of physical qubits and NI is the number of impurity orbitals [28].

FAQ 3: What common issue causes convergence to false minima in adaptive VQE, and how can it be mitigated?

A significant challenge is the "winner's curse" or stochastic violation of the variational bound, where finite sampling noise creates false minima that appear below the true ground state energy. Effective mitigation strategies include using population-based optimizers like CMA-ES and iL-SHADE, which implicitly average noise, and tracking the population mean of optimizers instead of the best individual to correct for estimator bias [29].

FAQ 4: Are there adaptive algorithms that avoid the high cost of gradient-based selection?

Yes, gradient-free adaptive algorithms have been developed. The Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE) uses an energy-sorting approach. It determines the best operator to append to the ansatz by analytically constructing one-dimensional "landscape functions," which requires a fixed, small number of measurements per operator, thus avoiding direct gradient estimation [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Prohibitive Measurement Overhead in Generator Selection

Symptoms

- Inability to complete a single ADAPT-VQE iteration within a reasonable time.

- Large variance in estimated energy gradients.

- Algorithm stagnation due to inaccurate operator selection.

Resolution Steps

- Reformulate as Best-Arm Identification (BAI): Frame the generator selection as a BAI problem, where the goal is to find the operator with the largest energy gradient magnitude. This allows for adaptive allocation of measurements [13].

- Implement Successive Elimination (SE): Apply the SE algorithm. It runs over multiple rounds, estimating gradients for the current active set of operators and progressively eliminating suboptimal candidates, thereby concentrating measurements on the most promising ones [13].

- Leverage Reduced Density Matrices (RDMs): For specific operator pools (e.g., single and double excitations), reformulate gradient evaluations in terms of RDMs. This can reduce the measurement scaling from ð’ª(Nâ¸) to ð’ª(Nâ´) by avoiding the direct measurement of high-body commutators [13].

Issue 2: Convergence Stagnation Due to Sampling Noise

Symptoms

- Optimization appears to converge to an energy above the true ground state.

- Parameter values fluctuate wildly between optimization steps.

- Different random seeds lead to convergence at different final energies.

Resolution Steps

- Switch to Noise-Resilient Optimizers: Replace standard gradient-based optimizers with adaptive metaheuristics. The algorithms CMA-ES and iL-SHADE have been shown to be particularly robust for VQEs under finite sampling noise [29].

- Apply Population Mean Tracking: When using population-based optimizers, use the population mean of the cost function to guide the optimization, rather than the best individual's value. This corrects for the estimator bias introduced by the "winner's curse" [29].

- Increase Shot Count Judiciously: For the final iterations or after selecting the best generator, increase the number of measurement shots (samples) to refine energy evaluations and reduce variance, ensuring the optimization is not misled by noise [13] [29].

Issue 3: Excessive Quantum Circuit Depth

Symptoms

- Computed energies are dominated by hardware noise.

- Fidelity of the output state is too low to be useful.

- Inability to run time evolution for sufficiently long to compute Green's functions.

Resolution Steps

- Employ Compressed Time Evolution Circuits: For time dynamics needed to compute Green's functions, use specialized circuit compression algorithms that exploit the impurity model's structure. This can significantly reduce the gate count compared to a naive Trotterized evolution [28].

- Adopt an Adaptive Circuit Growth Strategy: Use algorithms like Adaptive pVQD, which systematically grow the quantum circuit during the time evolution. This dynamic approach creates shallower, problem-tailored circuits that are more feasible for near-term hardware [30].

- Utilize a Superposition of Gaussian States (SGS): For ground state preparation, leverage the fact that the impurity ground state can often be well-approximated by an SGS. These states are typically easier to prepare on quantum hardware and can be evaluated sequentially with classical post-processing [28].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Impurity Green's Function Measurement on Quantum Hardware

This protocol outlines the key steps for extracting the impurity Green's function, a critical component in DMFT calculations, using a quantum processor [28].

Table: Key Steps for Impurity Green's Function Measurement

| Step | Action | Key Resource Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 1. State Preparation | Prepare the ground state of the impurity model using a low-depth ansatz (e.g., based on SGS or ADAPT-VQE). | Circuit depth and fidelity are critical. |

| 2. Time Evolution | Apply compressed, short-depth time evolution circuits to the prepared state. | Gate count scales as ð’ª(NI × Nq) after compression. |

| 3. Measurement & Signal Processing | Measure the relevant observables and apply physically motivated signal processing techniques. | Reduces the impact of hardware noise on the extracted data. |

Protocol 2: Successive Elimination for Generator Selection

This protocol details the use of the Successive Elimination algorithm to reduce the measurement cost in adaptive VQE [13].

Table: Successive Elimination Algorithm Parameters and Actions

| Round (r) | Precision (εᵣ) | Active Set (Aᵣ) | Key Action | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initialization (r=0) | c₀·ε | A₀ = 𒜠(full pool) | Estimate all | gᵢ | with low precision. |

| Intermediate Rounds (0 < r < L) | cᵣ·ε (cᵣ ≥ 1) | Aᵣ ⊆ Aᵣ₋₠| Eliminate generators where | gᵢ | + Rᵣ < M - Rᵣ. |

| Final Round (r = L) | ε | A_L (final candidates) | Select generator with largest | gᵢ | estimated at target precision. |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials & Tools

Table: Key "Reagents" for Quantum Impurity Model Experiments

| Research "Reagent" | Function / Purpose | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pool | A pre-selected set of parametrized unitary operators (e.g., fermionic excitations, qubit operators) from which the adaptive ansatz is built. | Qubit pools of size 2N-2; pools respecting molecular symmetries [13] [27]. |

| Ancilla Qubits | Additional qubits used in certain algorithms for tasks like performing Hadamard tests for overlap measurements. | Some GF measurement methods require ancillas; ancilla-free methods are also available [28]. |

| Fragmentation & Grouping Strategy | A technique to break down the measurement of complex operators (like commutators) into measurable fragments. | Qubit-wise commuting (QWC) fragmentation with sorted insertion (SI) grouping [13]. |

| Classical Optimizer | A classical algorithm that adjusts the quantum circuit parameters to minimize the energy. | For noisy environments, CMA-ES and iL-SHADE are recommended [29]. |

| Circuit Compression Algorithm | A method to reduce the gate depth of quantum circuits, specifically tailored to the structure of impurity problems. | Reduces gate count per Trotter step to ð’ª(NI × Nq) [28]. |

Integration with Quantum Embedding Methods for Correlated Materials

For researchers investigating correlated electron systems, integrating variational quantum algorithms with quantum embedding methods like Dynamical Mean Field Theory (DMFT) presents a significant promise: the ability to accurately simulate materials and molecules that are intractable with purely classical computational methods. This integration is a core focus in the quest for practical quantum advantage in materials science and drug discovery [28]. However, this path is fraught with a fundamental challenge: convergence issues in the underlying adaptive variational algorithms [5].

These algorithms, such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), aim to find the ground state energy of a Hamiltonian by iteratively optimizing the parameters of a parameterized quantum circuit. The success of this optimization is critical for quantum embedding methods, where the quantum computer acts as an "impurity solver"—a key bottleneck in DMFT calculations for strongly correlated materials [28]. When the variational optimization fails to converge to the correct ground state, the entire embedding procedure is compromised, leading to inaccurate predictions of material properties. This technical guide addresses the specific convergence problems encountered in this context and provides actionable troubleshooting protocols.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Convergence