Navigating Quantum Hardware Constraints for Chemical Simulation: A 2025 Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current landscape of quantum computing for simulating chemical systems, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Navigating Quantum Hardware Constraints for Chemical Simulation: A 2025 Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current landscape of quantum computing for simulating chemical systems, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational hardware limitations of Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, details innovative methodological workarounds like hybrid algorithms and error mitigation, and presents real-world case studies from pharmaceutical R&D. The content synthesizes the latest research and industrial applications to offer a practical guide for validating quantum simulations and benchmarking them against established classical methods, outlining a clear path toward quantum utility in biomedical discovery.

The NISQ Era: Understanding Fundamental Quantum Hardware Barriers

FAQ: Understanding NISQ Hardware for Chemical Simulation

Q1: What do the terms "NISQ," qubit count, fidelity, and coherence time mean for my research?

The NISQ era (Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum) describes today's quantum devices, which have impressive capabilities but are limited by noise and errors [1]. For your chemical simulations, understanding the hardware's physical constraints is critical to designing viable experiments.

- Qubit Count: This is the number of quantum bits, or qubits, in a processor. While more qubits allow you to simulate larger molecules, the quality of these qubits is often more important than the quantity [1] [2].

- Fidelity: This measures the accuracy of a quantum operation. A fidelity of 99.9% means an error occurs 1 in 1,000 times. High-fidelity two-qubit gates (typically >99%) are essential for generating reliable results, as they are the main source of entanglement in quantum circuits [3] [2].

- Coherence Time: This defines how long a qubit can maintain its quantum state before information is lost to decoherence. Your quantum circuit's total runtime must be shorter than the coherence time to produce a meaningful output [1] [3].

Q2: My complex molecular simulation failed. Is the problem my algorithm or the hardware?

This is a common challenge. The issue often lies in the hardware's current limitations. The following table compares the resource requirements for a substantial chemical simulation (like the Google Quantum Echoes experiment) against the specifications of current and upcoming hardware [4].

Table: Resource Requirements vs. Current NISQ Hardware Capabilities

| Resource Type | Demand for Complex Simulation | Representative NISQ Hardware Specs (2025) |

|---|---|---|

| Qubit Count | ~65+ qubits [4] | • SPINQ C20: 20 qubits [3]• IBM Nighthawk: 120 qubits [5]• Rigetti 2025 Target: 100+ qubits [6] |

| Two-Qubit Gate Fidelity | >99.8% (for deep circuits) [4] | • SPINQ: ≥99% [3]• Google: ~99.85% [4]• Rigetti 2025 Target: 99.5% [6] |

| Total Gate Operations | Up to 5,000+ two-qubit gates [5] [4] | • IBM Nighthawk: 5,000 gates [5] |

| Coherence Time | Must support full circuit execution | • SPINQ: ~100 μs [3] |

Diagnosis: If your algorithm requires more qubits, higher fidelity, or a deeper circuit (more gates) than the hardware can provide, it will fail regardless of the algorithm's theoretical correctness [1] [2].

Q3: The results from my VQE calculation are too noisy. How can I improve accuracy?

Error mitigation techniques are essential for extracting usable data from NISQ devices. Here is a detailed protocol for implementing Zero Noise Extrapolation (ZNE), a widely used method referenced in the search results [7].

Table: Protocol for Zero Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) in a VQE Workflow

| Step | Action | Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Run Baseline | Execute your VQE circuit at the native noise level. | Establish a baseline energy expectation value. | Run 10,000 shots (circuit repetitions) to compute an average. |

| 2. Scale Noise | Intentionally increase noise by stretching pulse durations or inserting identity gates (gate folding). | Create a series of circuits with known, higher noise levels. | Scale noise by factors of 1.5x, 2.0x, and 2.5x. Run each scaled circuit. |

| 3. Measure & Fit | Record the energy expectation value at each noise scale. Fit this data to a model (e.g., linear, exponential). | Establish a trend between noise level and result inaccuracy. | Plot energy vs. noise scale factor and extrapolate the trend back to a zero-noise intercept. |

| 4. Extract Result | Use the extrapolated zero-noise value as your mitigated result. | Obtain a more accurate estimate of the molecular energy. | The mitigated result should have lower error than the raw baseline data. |

Q4: How do I choose the right quantum processor for my chemical simulation problem?

Selecting a processor requires balancing your problem size against hardware performance. Use this decision workflow to guide your choice.

Q5: What are the most critical hardware specs to check before running a simulation?

Always verify these three core metrics, which are the most direct determinants of algorithmic success or failure [1] [2]:

- Median Two-Qubit Gate Fidelity: This is often the most limiting factor. Aim for systems with 99.5% or higher for meaningful results [6] [4].

- Qubit Coherence Time (T1 & T2): Ensure the total estimated execution time of your circuit (number of gates × gate time) is significantly less than the coherence time.

- Total Usable Gate Count: The hardware platform will have a maximum number of gates (circuit depth) it can reliably execute before noise dominates. For example, IBM's Nighthawk targets 5,000 two-qubit gates [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential "Reagents" for NISQ-Era Chemical Simulation Research

| Tool / Solution | Function / Definition | Role in the Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Error Mitigation (e.g., ZNE) | A class of software techniques that post-process noisy results to infer a less noisy answer [8]. | A crucial "reagent" to purify signal from noise. It is a current stopgap before full error correction [7]. |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | A hybrid quantum-classical algorithm that uses a quantum computer to measure molecular energies and a classical computer to optimize parameters [7]. | The leading algorithm for near-term chemical simulations like calculating ground state energies, as it can be designed with relatively shallow circuits. |

| Logical Qubit | A fault-tolerant qubit encoded across multiple error-prone physical qubits, using quantum error correction codes [8]. | Not yet widely available, but represents the future "solvent" for the noise problem. Demonstrations are underway [7]. |

| Quantum Volume (QV) | A holistic benchmark metric that accounts for qubit count, fidelity, and connectivity [2]. | A useful "assay" for comparing the overall capability of different quantum processors, beyond just qubit count. |

| Hardware-Specific Compiler | Software that translates a high-level algorithm into the specific native gates and topology of a target QPU [1]. | The "pipette" that accurately delivers your instructions to the hardware, ensuring efficient execution. |

| 1-(4-Methoxycyclohexyl)propan-1-one | 1-(4-Methoxycyclohexyl)propan-1-one|High-Purity|RUO | 1-(4-Methoxycyclohexyl)propan-1-one is a high-purity ketone for research (RUO). Explore its applications as a synthetic intermediate. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2,2-Dimethylbutane-1-sulfonamide | 2,2-Dimethylbutane-1-sulfonamide, CAS:1566355-58-5, MF:C6H15NO2S, MW:165.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the fundamental bottleneck when simulating large molecules like catalysts or proteins? The core bottleneck is the number of qubits required to represent the molecule's electronic structure. While a hydrogen molecule might need only a few qubits, complex molecules like the iron-molybdenum cofactor (FeMoco) or Cytochrome P450 enzymes were initially estimated to require millions of physical qubits [9]. Although recent advances in algorithms and hardware have reduced this requirement to just under 100,000 qubits for some systems, this still far exceeds the capacity of today's most advanced quantum processors, which are in the thousand-qubit range [10] [9].

Which quantum algorithms are most practical for chemistry on today's limited hardware? The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is the most established near-term algorithm [9] [7]. It uses a hybrid quantum-classical approach, where the quantum computer calculates the molecular energy for a trial wavefunction and a classical computer adjusts the parameters to find the minimum energy (ground state). This is efficient for small qubit counts but faces challenges with optimization for larger systems. Other algorithms are emerging for specific tasks, such as computing forces between atoms or simulating chemical dynamics [9].

My results are noisy. What error mitigation techniques can I apply? Error mitigation is crucial for extracting meaningful data from current "noisy" hardware. Key techniques include:

- Zero Noise Extrapolation (ZNE): Intentionally running the same circuit at different noise levels (e.g., by stretching gate times or inserting identity gates) and then extrapolating the result back to the zero-noise limit [7].

- Algorithmic Fault Tolerance: New techniques, such as those published by QuEra, can reduce quantum error correction overhead by up to 100 times, making error correction more feasible on nearer-term hardware [10].

Are there any molecule simulation tasks that can be done on current hardware? Yes, but they are limited in scale. Successful demonstrations on current hardware include:

- Modeling small molecules like hydrogen, lithium hydride, and beryllium hydride [9].

- Estimating the energy of an iron-sulfur cluster using a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm [9].

- Simulating the folding of a 12-amino-acid protein chain [9].

- Quantum simulation of Cytochrome P450 with greater efficiency than traditional methods, as shown in a collaboration between Google and Boehringer Ingelheim [10].

How does qubit fidelity impact my chemical simulation results? Qubit fidelity directly determines the depth and complexity of the quantum circuits you can run before your results become unreliable. Low fidelity leads to rapid accumulation of errors, which obscures the true molecular energy you are trying to calculate. For example, achieving a high-fidelity "magic state" for universal quantum computation has been a major hurdle, with recent demonstrations showing improved logical fidelity through distillation processes [7] [11]. Breakthroughs in 2025 have pushed error rates to record lows of 0.000015% per operation, a critical improvement for running deeper, more meaningful chemistry simulations [10].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Energy calculation not converging (e.g., in VQE) | The classical optimizer is stuck in a local minimum or the quantum hardware noise is overwhelming the signal. | Use a different classical optimizer (e.g., SPSA, COBYLA). Employ error mitigation techniques like ZNE to get cleaner results from the quantum processor [7]. |

| Circuit depth exceeds coherence time | The molecule is too complex, requiring a circuit with more gates than the qubits can coherently maintain. | Simplify the problem using methods like the Compact Fermion to Qubit Mapping to reduce qubit and gate overhead [11]. Use a quantum processor with longer coherence times, such as neutral atom systems achieving 0.6 millisecond coherence times [10]. |

| Insufficient qubits for target molecule | The hardware's physical qubit count is less than the logical qubits required by the problem. | Employ problem decomposition techniques or use a quantum-classical hybrid algorithm that breaks the problem into smaller parts solvable by available hardware [9]. |

| High error rates in two-qubit gates | Imperfect gate calibration and crosstalk between qubits. | Check the latest calibration data from the hardware provider (e.g., IBM Quantum, QuEra). Use dynamical decoupling sequences on idle qubits to protect them from decoherence during the circuit execution [10]. |

Hardware Landscape and Molecular Qubit Requirements

The table below summarizes the current hardware capabilities and the estimated qubit requirements for simulating various molecules, highlighting the scaling challenge.

| Molecular System | Estimated Physical Qubits (Initial) | Estimated Physical Qubits (2025, with improvements) | Hardware Platform Examples (2025) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron-Molybdenum Cofactor (FeMoco) | ~2.7 million [9] | <100,000 [9] | N/A (Future fault-tolerant systems) |

| Cytochrome P450 | Similar scale to FeMoco [9] | N/A | N/A (Future fault-tolerant systems) |

| Small Molecules (e.g., Hâ‚‚, LiH) | < 10 | < 10 | IBM Nighthawk, Google Willow, IonQ systems |

| Utility-Scale Simulation | N/A | 3,000+ (for coherent storage) [12] [13] | Neutral atom arrays (e.g., QuEra, Atom Computing) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key components and their functions in a modern neutral-atom quantum experiment, which is a leading architecture for scaling qubit counts.

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| 87Rb Atoms | The physical medium for qubits. Rubidium-87 is a common choice due to its well-understood energy levels and compatibility with laser cooling techniques [12] [13]. |

| Optical Lattice Conveyor Belts | Transport a reservoir of cold atoms into the science region. This enables continuous reloading of the system, which is essential for maintaining large, stable qubit arrays over long durations [12] [13]. |

| Optical Tweezers | Created by acousto-optic deflectors (AODs) or spatial light modulators (SLMs) to trap and manipulate individual atoms, positioning them into ordered arrays for computation [12]. |

| Spatial Light Modulator (SLM) | Generates a static, defect-free array of optical tweezers for stable qubit storage and manipulation. AI-enhanced protocols can use SLMs for rapid assembly of thousands of atoms [11]. |

| Dynamical Decoupling Sequences | A sequence of pulses applied to qubits to protect them from dephasing due to environmental noise, thereby extending their coherence time [12]. |

| 3-Bromo-5,6-difluoro-1H-indazole | 3-Bromo-5,6-difluoro-1H-indazole, CAS:1017781-94-0, MF:C7H3BrF2N2, MW:233.01 g/mol |

| 3,4-Dichloro-3'-methylbenzophenone | 3,4-Dichloro-3'-methylbenzophenone, CAS:844885-24-1, MF:C14H10Cl2O, MW:265.1 g/mol |

Experimental Protocol: VQE with Error Mitigation for Molecular Energy Calculation

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for running a Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) experiment to calculate the ground-state energy of a molecule, incorporating error mitigation for more reliable results on noisy hardware.

VQE Workflow with Zero Noise Extrapolation (ZNE)

1. Problem Definition:

- Input: Define the target molecule and its geometry.

- Action: Generate the molecular Hamiltonian (H) in a qubit-representable form using a transformation like Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev. For a simple Hâ‚‚ molecule, this results in a weighted sum of Pauli terms (e.g., H = câ‚II + câ‚‚IZ + c₃ZI + câ‚„ZZ + câ‚…XX) [7].

2. Ansatz Preparation:

- Input: The qubit Hamiltonian.

- Action: Choose and prepare a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) that can represent the molecular wavefunction. A "hardware-efficient" ansatz, using native gates from the target quantum processor, is common for near-term devices [7].

3. Quantum Execution with ZNE:

- For a given set of ansatz parameters (θ), the quantum circuit is run multiple times.

- ZNE Implementation: The same circuit is executed at different scaled noise levels (e.g., scale_factors = [1, 2, 3]). Noise scaling can be achieved by "gate folding" (adding pairs of identity gates that logically cancel out but increase the exposure to noise) [7].

- The expectation value of the Hamiltonian ⟨H(θ)⟩ is measured for each noise level.

4. Classical Optimization Loop:

- Input: The measured expectation values from the quantum processor.

- Action:

- The classical optimizer (e.g., COBYLA, SPSA) receives the ZNE-extrapolated, zero-noise expectation value.

- The optimizer calculates a new set of parameters θ_new to minimize the energy.

- These new parameters are sent back to the quantum processor for the next iteration.

- This loop repeats until the energy converges to a minimum.

5. Result:

- The converged energy value is the computed estimate of the molecule's ground-state energy.

Protocol for Continuous Operation of Large-Scale Atom Arrays

For experiments requiring long-duration computation, such as deep quantum error correction or extended sensing, continuous operation is key. The following workflow, demonstrated with neutral atoms, outlines how to maintain a large qubit array.

Continuous Reloading Workflow

1. Reservoir Creation and Transport:

- Action: Load millions of â¸â·Rb atoms from a magneto-optical trap (MOT) into a first optical lattice conveyor belt.

- Transport: Move the atom cloud to a separate, ultra-high-vacuum science chamber and transfer it to a second conveyor belt, which acts as the main reservoir. This two-stage process protects the science region from background gas [12] [13].

- Output: A fresh, cold atom reservoir is delivered to the science region approximately every 150 ms.

2. Qubit Extraction and Preparation:

- Extraction: Optical tweezers are overlapped with the reservoir to capture atoms "in the dark" (without laser cooling) to avoid disturbing nearby qubits. The captured atoms are quickly moved to a dedicated "preparation zone" [12] [13].

- Initialization: In the preparation zone, atoms are laser-cooled, imaged via a high-resolution microscope, and rearranged into a defect-free array. They are then initialized into the qubit state |0⟩ via optical pumping, achieving high state preparation and measurement (SPAM) fidelity [12].

- Throughput: This architecture can achieve a flux of over 30,000 initialized qubits per second [12] [13].

3. Array Assembly and Coherent Storage:

- Action: The prepared qubits are transported to the final "storage zone," a large, static array of optical tweezers generated by a spatial light modulator (SLM).

- Assembly: The full array (e.g., of 3,000+ atoms) is assembled iteratively by loading multiple sub-arrays [12].

- Coherence Maintenance: Dynamical decoupling sequences are applied to the stored qubits to protect them from dephasing. The storage zone is spatially and spectrally shielded from the disruptive light used in the preparation zone [12] [13].

4. Monitoring and Reloading:

- Action: As qubits are lost during computation (e.g., from entangling gates or finite trap lifetime), the system detects the losses.

- Feedback Loop: A signal triggers the extraction and preparation of new qubits from the reservoir to refill the vacancies in the storage array, all without affecting the quantum state of the remaining qubits.

- Outcome: This allows for the maintenance of a large qubit array (e.g., >3,000 atoms) for hours, far beyond the typical trap lifetime of about 60 seconds [12] [13].

The Impact of Noise and Decoherence on Simulation Accuracy

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between noise and decoherence in quantum simulations?

A: Noise is a broader term encompassing all unwanted disturbances, such as gate errors or control signal imperfections. Decoherence is a specific type of noise where the qubit loses its quantum state due to interactions with the environment, causing the collapse of superposition and entanglement [14]. In chemical simulations, this means that the quantum state representing a molecule's electronic structure can be destroyed before the computation is complete.

Q2: How does decoherence directly impact the simulation of chemical systems?

A: Decoherence introduces errors in the quantum state of the system, which can manifest as incorrect molecular energies, faulty reaction pathways, or inaccurate vibrational frequencies. For example, in simulations of NMR spectroscopy, decoherence causes broadening of spectral lines, obscuring the true resonance frequencies of nuclear spins [15]. This limits the simulation's ability to predict precise chemical properties.

Q3: Can the noise present on quantum hardware ever be beneficial for simulating chemical systems?

A: In some specific contexts, yes. Since real chemical systems in a lab are also subject to environmental noise, the inherent noise of a quantum processor can be reinterpreted as simulating a more realistic, "open" quantum system. Research has shown that for certain quantum spin systems, the effects of hardware noise can be mapped to simulate the dynamics of a system coupled to its environment [16]. However, this is a non-trivial process and requires careful modeling.

Q4: What are the most common sources of noise that affect quantum simulations of molecules?

A: The primary sources include [17] [14]:

- Spin-lattice interactions: Vibrations (phonons) in the qubit substrate or material that cause the qubit to relax.

- Magnetic field noise: Fluctuations in local magnetic fields, often from nuclear spins in the lattice or control electronics.

- Control signal noise: Imperfections in the microwave or laser pulses used to manipulate qubits.

- Material defects: Microscopic imperfections in the qubit hardware that create unpredictable charge or magnetic fluctuations.

Q5: How can I determine if my quantum simulation of a molecule has been significantly impacted by decoherence?

A: Key indicators include:

- Results that violate physical laws, such as molecular energies that are not variational.

- Inconsistent outputs between successive runs of the same simulation.

- A significant drop in the fidelity of the final quantum state compared to the expected ideal state [18].

- For dynamics simulations, a faster decay of observables (like magnetization or correlation functions) than theoretically predicted [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating Decoherence in Trotterized Time Evolutions

Trotterized time evolution is a common method for simulating chemical dynamics, such as molecular vibrations or reaction pathways [19]. Decoherence can severely limit the depth and accuracy of such simulations.

Symptoms:

- Simulated correlation functions, like

Tr{Stotz(t)Stotz}for NMR spectra, decay too rapidly [15]. - The Fourier transform of the signal (

A(ω)) shows excessive broadening, making spectral peaks unresolvable. - The algorithm fails to converge as the Trotter step size is decreased.

Diagnostic Table: Common Decoherence Signatures

| Observable Anomaly | Possible Noise Source | Theoretical Scaling Hint |

|---|---|---|

| Exponential decay of signal fidelity | General energy relaxation (Tâ‚ noise) | 1/Tâ‚ decay rate [14] |

| Rapid loss of phase information (dephasing) | Magnetic field fluctuations (T₂ noise) | 1/B² scaling for pure magnetic noise [17] |

| Combined relaxation and dephasing | Spin-lattice and magnetic noise | 1/B scaling for Tâ‚; 1/B² for Tâ‚‚ [17] |

| Broadened spectral lines | Effective environmental coupling | Modeled by an effective decoherence rate Γ in A(ω) [15] |

Methodology & Mitigation Steps:

- Characterize Hardware Noise: Before running your chemistry simulation, determine the

T1(relaxation time) andT2(dephasing time) of the qubits you are using. Most quantum computing service providers report these values. - Benchmark with Simple Molecules: Run simulations for small, well-understood molecules (e.g., Hâ‚‚, LiH) and compare the output (e.g., ground state energy, simple spectrum) against known theoretical results. This establishes a baseline for noise impact on your specific algorithm [9].

- Use Effective Models: For advanced analysis, model the combined effect of your Trotterization algorithm and hardware noise as a Static Effective Lindbladian. This model describes the noisy algorithm as the original unitary dynamics plus static Lindblad (noise) terms [16].

- Apply Noise-Filtering Algorithms: If the ideal quantum state is still the principal component of your noise-affected output state, use quantum algorithms like Quantum Principal Component Analysis (qPCA) to filter out the noise and recover a higher-fidelity state [18].

- Optimize Algorithm Parameters: Shorten the total circuit depth or adjust the Trotter step size to complete the simulation within the coherence window of the hardware.

Guide 2: Improving Quantum Metrology for Chemical Sensing

Quantum metrology uses quantum properties to enhance the precision of measurements, such as detecting weak magnetic fields in chemical analysis. Noise is a fundamental barrier to achieving the theoretical Heisenberg limit.

Symptoms:

- Measurement accuracy and precision for a parameter (e.g., magnetic field strength) are far below the theoretical Heisenberg limit.

- The Quantum Fisher Information (QFI), which quantifies the ultimate precision, is significantly degraded.

Methodology for Noise-Resilient Metrology [18]:

This protocol involves using a secondary quantum processor to clean the noisy quantum state from a sensor.

- State Preparation: Initialize an entangled probe state (e.g., a GHZ state) on the sensor qubits.

- Parameter Encoding: Let the probe state evolve under the parameter

Ï•(e.g., a phase from a magnetic field) to become the ideal stateÏ_t. - Noisy Evolution: The sensor is subject to a noise channel

Λ, resulting in a noisy stateÏ~_t. - Quantum State Transfer: Transfer

Ï~_tto a more stable quantum processor using quantum state transfer or teleportation, avoiding a classical bottleneck. - Quantum Processing: On the processor, apply a noise-filtering algorithm like qPCA. This extracts the dominant, noise-free component from

Ï~_t. - Measurement: The output is a noise-resilient state

Ï_NRfrom which the parameterÏ•can be estimated with significantly higher accuracy and precision.

The workflow for this process is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

This table lists essential "research reagents"—in this context, key theoretical models, computational tools, and algorithms used to diagnose and combat noise in quantum simulations.

| Tool / "Reagent" | Function / Purpose | Example in Chemical Simulation Context |

|---|---|---|

| Static Effective Lindbladian [16] | Models how noise from the quantum hardware modifies the intended simulated dynamics. | Reinterprets noise in a Trotterized spin dynamics simulation as part of the effective open quantum system being studied. |

| Redfield Quantum Master Equation [17] | A theoretical framework used to predict the relaxation (Tâ‚) and dephasing (Tâ‚‚) times of a quantum system coupled to a environment. | Predicting the coherence times of a molecular spin qubit (e.g., in a copper porphyrin complex) based on atomistic fluctuations. |

| Quantum Principal Component Analysis (qPCA) [18] | A quantum algorithm that filters noise from a quantum state by extracting its dominant components. | Purifying a noisy quantum state that encodes a molecular property, thereby improving measurement accuracy in quantum sensing. |

| Haken-Strobl Theory [17] | A semi-classical noise model that treats environmental influence as stochastic fluctuations on the system's Hamiltonian. | Modeling the effect of random magnetic field noise (δB_i(t)) on the electronic spin Hamiltonian of a molecule. |

| ARTEMIS (Simulation Tool) [20] | An exascale electromagnetic modeling tool for simulating quantum chip performance before fabrication. | Predicting and minimizing crosstalk and signal propagation issues in a chip designed to run quantum chemistry algorithms. |

| Hybrid Atomistic-Parametric Model [17] | Combines first-principles molecular dynamics with parametric noise models to predict qubit coherence. | Quantifying the contribution of lattice phonons vs. nuclear spins to the decoherence of a molecular qubit. |

| Hydroxy-PEG3-2-methylacrylate | Hydroxy-PEG3-2-methylacrylate, CAS:2351-42-0, MF:C10H18O5, MW:218.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5-Aminoadamantan-2-ol;hydrochloride | 5-Aminoadamantan-2-ol;hydrochloride, CAS:180271-44-7, MF:C10H18ClNO, MW:203.71 | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs: Understanding Hardware Constraints

What are the most common quantum hardware constraints affecting chemical simulations? The most common constraints are qubit connectivity, limited gate sets, and qubit decoherence. Qubit connectivity refers to which qubits can directly interact to perform multi-qubit gates—some architectures only allow nearest-neighbor interactions, forcing additional "swap gates" that increase circuit depth and error rates. Each hardware platform also supports a specific native gate set (e.g., IBM's u1/u2/u3 gates vs. Rigetti's Rx/Rz/CZ gates), requiring transpilation that can substantially increase gate count and circuit depth. Furthermore, qubits have limited coherence times (microseconds to milliseconds), restricting the maximum possible circuit depth before quantum information is lost [21] [22].

How does qubit connectivity impact the simulation of molecular Hamiltonians? Molecular Hamiltonians for chemical systems generate quantum circuits that require specific interaction patterns between qubits. Restricted connectivity, such as the planar nearest-neighbor grid in Google's Sycamore processor, can make these interactions inefficient. For instance, implementing an entangling gate between two non-adjacent qubits may require a chain of SWAP operations to bring the quantum states physically "closer" in the qubit network. This overhead increases the circuit's depth, uses more gates, and compounds errors, potentially rendering deep chemical simulations like phase estimation infeasible on current hardware [23] [21].

My quantum circuit fails device validation. What should I check first? First, verify that all qubits in your circuit are actual physical qubits that exist on the target device. Second, check that all two-qubit gates are only applied to pairs of qubits that are directly connected according to the device's connectivity graph. Third, confirm that all gates in your circuit are part of the device's native gate set. Most software development kits, like Cirq, provide device validation methods that will explicitly state which of these constraints your circuit violates [23].

What is the trade-off between circuit depth and width (qubit count) in chemical simulations? There is often a direct trade-off between circuit depth (number of sequential gate operations) and width (number of qubits used). Synthesis tools can sometimes reduce circuit depth at the expense of using more ancillary qubits, for example, through qubit reuse strategies. Conversely, if qubits are a scarce resource, the compiler may be forced to create a deeper, more serialized circuit to accomplish the same computation with fewer qubits. This is critical because deeper circuits are more susceptible to decoherence and cumulative gate errors [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Two-Qubit Gate Errors in Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) Simulations

Issue: Energy calculations for molecular ground states are inaccurate or fail to converge, primarily due to noise from two-qubit gates.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Benchmark Gate Fidelity: Check the hardware provider's documented average fidelity for native two-qubit gates (e.g., CNOT, CZ, SYC). This is often 0.1% to 1% on current devices [22].

- Analyze Circuit: Count the number of two-qubit gates in your ansatz circuit. Multiply the average two-qubit gate error by this count to estimate the total error contribution.

- Check Connectivity Mapping: Use a tool like the Classiq Analyzer or Cirq's

validate_circuitfunction to see how many SWAP gates were added during the compilation process to accommodate hardware connectivity. A high number indicates significant overhead [23] [21].

Resolution Strategies:

- Choose an Efficient Ansatz: Select a molecular ansatz (e.g., QCC, qubit-ADAPT) that minimizes the number of two-qubit gates, even if it increases single-qubit gate count, as single-qubit gates typically have much higher fidelity.

- Leverage Global Gates (if available): On hardware like trapped ions that support global entangling gates, a single gate can replace multiple two-qubit gates. Consider using a variational approach with a parameterized circuit built from a finite number of global gates, which can be more efficient and noise-resilient for tasks like ground state preparation [24].

- Use Error Mitigation: Apply techniques like Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) to infer what the result would be in the absence of noise by running the same circuit at different noise levels.

Problem: Circuit Fails Validation Due to Connectivity or Gate Set

Issue: A circuit developed in a high-level framework (e.g., OpenFermion) fails when sent to a target device, returning validation errors.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Identify the Specific Error: The validation error message is the first clue. Common messages include:

- "Qubit not on device": You are using a qubit index that doesn't physically exist [23].

- "Qubit pair is not valid on device": You are applying a two-qubit gate to a pair of qubits that are not directly connected [23].

- "Gate not supported": You are using a gate (e.g., a multi-qubit rotation) that is not in the device's native gate set.

- Visualize Device Topology: Plot the device's connectivity graph (e.g., using

metadata.nx_graphin Cirq) to understand which qubit pairs can natively interact [23].

Resolution Strategies:

- Use a Hardware-Aware Compiler: Instead of manually rewriting the circuit, use a compiler or synthesizer tool (like Classiq, Cirq, or Qiskit's transpiler) that is aware of the target device's constraints. Provide it with your abstract circuit and the device's constraints (gate set, connectivity, etc.), and let it find an equivalent, executable circuit [21].

- Manually Adjust the Mapping: If necessary, you can manually reassign the logical qubits of your algorithm to different physical qubits on the device to minimize the distance between qubits that need to interact frequently.

Problem: Excessive Circuit Depth Leading to Decoherence

Issue: The circuit compiles successfully but the results are random noise. The circuit depth is longer than the qubits' coherence times.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Calculate Circuit Depth: Use your quantum SDK to determine the total depth of your compiled circuit.

- Compare with Coherence Time: Check the hardware specifications for the

T2coherence time (typically 100-200 microseconds for superconducting qubits). Estimate the total execution time by multiplying the circuit depth by the average gate time (e.g., ~100 ns for two-qubit gates). If the total time is a significant fraction of theT2time, decoherence is a likely cause of failure [22].

Resolution Strategies:

- Apply Circuit Optimization: Use the compiler's highest optimization level. Modern compilers can identify and remove redundant gates, merge consecutive rotations, and optimize the placement of SWAP gates to significantly reduce depth.

- Enforce a Depth Constraint: Some advanced synthesis platforms like Classiq allow you to set a maximum depth as a constraint. The synthesizer will then explore various implementations of your algorithm's functionality to find one that meets this depth limit, even if it requires more qubits [21].

- Simplify the Problem: For chemical simulations, consider reducing the active space in your molecular orbital calculations or using a simpler basis set to generate a shorter-depth quantum circuit.

Quantum Hardware Constraints for Chemical Simulations

The table below summarizes key constraints across leading qubit technologies that directly impact the simulation of chemical Hamiltonians.

| Qubit Technology | Native Gate Fidelity | Typical Connectivity | Coherence Time | Key Constraint for Chemistry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superconducting Circuits [25] [22] | Single-qubit: >99.9%; Two-qubit: ~99-99.9% | Planar nearest-neighbor (e.g., Google's Sycamore grid [23]) | ~100-200 microseconds | Limited connectivity increases SWAP gates for molecular orbital interactions. |

| Trapped Ions [25] [24] | Very high two-qubit fidelity; supports global gates | All-to-all | Minutes (exceptionally long) | Computation speed can be slower due to physical ion movement. |

| Neutral Atoms [25] | Higher error rates than other technologies | Can be reconfigured; long-range | Minutes | Higher gate error rates can overwhelm subtle chemical energy differences. |

| Spin Qubits [25] | Similar challenges to superconducting | Nearest-neighbor | Challenges with cooling and control at scale | Dense qubit packing leads to heat dissipation and crosstalk issues. |

| Tool Category | Example | Function in Chemical Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware SDKs & Validation | Cirq Device classes (e.g., Sycamore) [23] |

Validates circuits against specific hardware constraints (qubit set, connectivity, native gates) before execution. |

| Algorithm Synthesizers | Classiq Platform [21] | Converts high-level functional models (e.g., Hamiltonian specification) into optimized circuits that meet user-defined constraints (depth, width). |

| Error Mitigation Suites | Mitiq, Qiskit Runtime | Applies post-processing techniques to noisy results to more closely approximate the true, noiseless value. |

| Global Gate Compilers | Custom variational algorithms [24] | Designs parameterized circuits that leverage native global entangling gates on platforms like trapped ions for more efficient ansatzes. |

Experimental Protocol: VQE on Constrained Hardware

This protocol details the steps for executing a Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) experiment for a molecular ground state on hardware with limited connectivity.

Objective: To find the ground state energy of a molecule (e.g., Hâ‚‚) using a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) optimized for a specific quantum processor.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Problem Formulation:

- Input: Molecular geometry and basis set (e.g., STO-3G).

- Action: Use a classical electronic structure package (e.g., PySCF) to compute the second-quantized molecular Hamiltonian.

- Output: Qubit Hamiltonian via a fermion-to-qubit mapping (e.g., Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev).

Ansatz Selection and Parameterization:

- Action: Choose a hardware-efficient ansatz (e.g.,

EfficientSU2in Qiskit) that uses primarily native gates of the target device. - Parameterization: Initialize the parameters

θof the ansatz circuitU(θ).

- Action: Choose a hardware-efficient ansatz (e.g.,

Hardware-Aware Circuit Compilation:

- Input: The abstract ansatz circuit and the target device's constraints (from its

Deviceobject). - Action: Use the hardware provider's transpiler (e.g., Qiskit's

transpilefunction withoptimization_level=3) to map the logical circuit to the physical qubit layout, respecting connectivity and converting to the native gate set. - Validation: Run the device's

validate_circuitmethod to ensure the compiled circuit is executable [23].

- Input: The abstract ansatz circuit and the target device's constraints (from its

Hybrid Quantum-Classical Optimization Loop:

- Quantum Processing: For the current parameters

θ_i, execute the compiled circuit on the quantum processor (or simulator) multiple times (shots) to measure the expectation value⟨H⟩ = Σ c_j ⟨P_j⟩for each term in the Hamiltonian. - Classical Processing: A classical optimizer (e.g., COBYLA, SPSA) receives the computed energy

E(θ_i)and proposes new parametersθ_{i+1}to lower the energy. - Iteration: Repeat this loop until the energy converges to a minimum.

- Quantum Processing: For the current parameters

Result Validation and Error Mitigation:

- Action: Apply error mitigation techniques (e.g., readout error mitigation, ZNE) to the final results.

- Benchmarking: Compare the computed VQE energy with the exact classical result for the same molecule and active space to gauge accuracy.

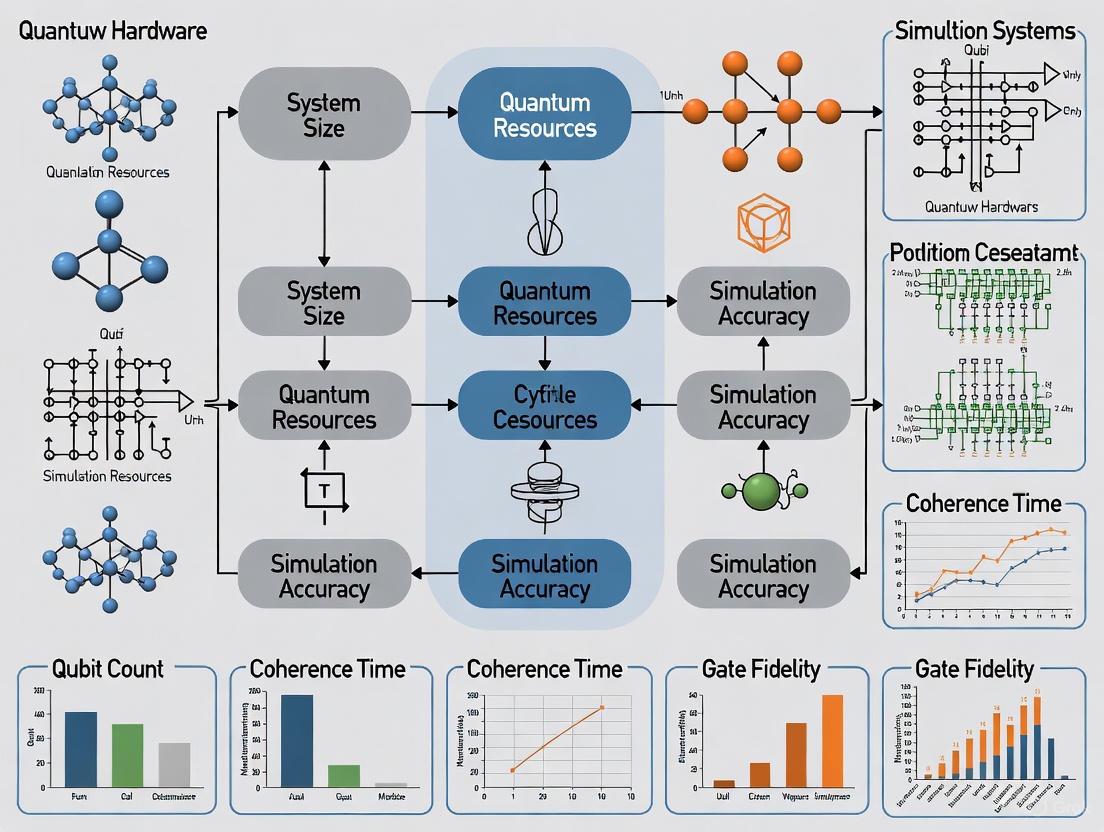

Workflow Diagram: Navigating Hardware Constraints

The diagram below illustrates the logical flow and decision points for designing and running a chemical simulation on constrained quantum hardware.

Bridging the Gap: Algorithmic and Hardware Strategies for Practical Simulation

For researchers in chemistry and drug development, hybrid quantum-classical algorithms represent the most promising path toward leveraging near-term quantum computers. However, current quantum hardware constraints—particularly noise and limited qubit coherence—present significant barriers to practical implementation. This technical support center addresses the specific experimental challenges you may encounter when applying the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and its next-generation successors to chemical system simulation.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

My VQE optimization is converging slowly or stuck in a flat region. What can I do?

Problem Explanation: This is a common issue known as a barren plateau, where the gradient of the cost function vanishes, making it difficult for the classical optimizer to find a direction for improvement [26]. This is often exacerbated by deep, hardware-efficient ansatzes and noise.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Switch Algorithms: Implement a greedy algorithm like Greedy Gradient-Free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE). It tests a few parameter directions and commits to the steepest descent, drastically reducing measurements and helping avoid flat spots [27].

- Reformulate the Problem: Consider moving from a constrained optimization (VQE) to a generalized eigenvalue problem framework, such as the Generator Coordinate Inspired Method (GCIM). This approach uses unitary coupled cluster (UCC) excitation generators to build a non-orthogonal subspace, bypassing the barren plateau issues common in standard VQE minimizers [28] [29].

- Refine Your Ansatz: Use an adaptive ansatz like ADAPT-VQE, which grows the circuit iteratively by selecting operators with the largest energy gradient, ensuring each new parameter provides meaningful progress [30] [26].

The results from my quantum hardware simulation are too noisy to be useful. What error mitigation strategies can I apply?

Problem Explanation: Current NISQ-era hardware introduces errors through decoherence, imperfect gate operations, and noisy measurements. These errors bias energy measurements and can lead to inaccurate results [30].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Apply Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE): Intentionally scale the noise in your quantum circuit by adding pairs of identity gates (which have no effect on an ideal state but increase the error rate on real hardware). By measuring the expectation value at different noise scales, you can extrapolate back to a "zero-noise" value [7].

- Use Quantum Autoencoders for Denoising: Implement a variational quantum denoising step, where an autoencoder is trained on noisy VQE outputs to predict and correct for the errors, increasing the final state fidelity [26].

- Leverage Classical Post-Processing: A Variational Quantum-Neural Hybrid Eigensolver (VQNHE) can enhance shallow, noisy ansatzes with a classical neural network, improving expressivity and accuracy with only polynomial classical overhead [26].

My molecular simulation requires too many qubits and gates. How can I reduce resource requirements?

Problem Explanation: The number of qubits required to simulate a molecule scales with the number of spin orbitals, and the circuit depth can grow rapidly, especially for chemistry-inspired ansatzes like UCCSD. This quickly exceeds the capabilities of current hardware [31] [9].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Employ Problem Decomposition: Use a method like ClusterVQE, which partitions the molecular problem into smaller, coupled fragments. Each fragment is solved with a shallow quantum circuit, and a dressed Hamiltonian accounts for the inter-cluster entanglement [26].

- Explore Contextual Subspace VQE: Partition the Hamiltonian into a part that is classically simulable (noncontextual) and a smaller, residual part (contextual) that is handled by the quantum computer. This can dramatically reduce quantum resource demands [26].

- Utilize Classical Pre-Processing: For specific problems like modeling catalyst spin properties, use a classical computer to simplify the Hamiltonian to focus only on the low-energy behavior of unpaired spins before mapping it to the quantum processor [32].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: ADAPT-VQE for Molecular Ground State Energy

This protocol is designed for finding the ground state energy of molecules like benzene, using an adaptive ansatz to minimize circuit depth [30].

- Problem Mapping: Transform the molecular electronic structure problem into a qubit Hamiltonian using a fermion-to-qubit mapping (e.g., Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev).

- Initialize Algorithm: Begin with a simple reference state, such as the Hartree-Fock state, prepared on the quantum computer.

- Operator Pool Definition: Define a pool of fermionic excitation operators (e.g., single and double excitations for UCCSD).

- Iterative Cycle:

- Step A: For each operator in the pool, measure the energy gradient with respect to adding that operator to the current ansatz.

- Step B: Identify and select the operator with the largest magnitude gradient.

- Step C: Add this operator to the ansatz circuit, introducing a new variational parameter.

- Step D: Use a classical optimizer (e.g., modified COBYLA) to minimize the energy expectation value with respect to all parameters in the now-grown ansatz.

- Convergence Check: Repeat the iterative cycle until the energy change falls below a predefined threshold. The final energy is the ground state estimate.

The following diagram illustrates the core adaptive workflow of the ADAPT-VQE protocol:

Protocol 2: Greedy Gradient-Free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE)

This protocol is optimized for noise resilience, reducing the quantum measurement burden which is a major source of error [27].

- Initialization: Prepare a parameterized ansatz state on the quantum processor.

- Parameter Perturbation: For the current parameter vector, generate a set of candidate parameter vectors by applying small perturbations in different directions.

- Energy Evaluation: For each candidate parameter vector, measure the energy expectation value on the quantum computer. The number of measurements per candidate can be minimized compared to standard VQE.

- Greedy Selection: Compare the measured energies and immediately select the candidate parameter set that yields the lowest energy.

- Iteration: Use the selected parameter set as the new starting point. Repeat steps 2-4 until the energy converges, without revisiting previous choices.

The diagram below contrasts the iterative "greedy" selection of GGA-VQE with the standard VQE optimization loop.

Reference Tables

Comparison of Advanced VQE Strategies

| Strategy | Core Principle | Key Advantage | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constrained VQE [26] | Adds penalty terms to cost function to preserve physical constraints (e.g., electron count). | Produces smooth, physically meaningful potential energy surfaces. | Simulating cations, anions, and systems where preserving symmetry is critical. |

| Evolutionary VQE (EVQE) [26] | Uses genetic algorithms to dynamically evolve circuit topology and parameters. | Automatically finds shallower, noise-resilient circuits. | Hardware-adaptive applications where optimal circuit design is unknown. |

| GCIM/ADAPT-GCIM [28] [29] | Builds a subspace from UCC generators, solving a generalized eigenvalue problem. | Bypasses barren plateaus; optimization-free for subspace construction. | Strongly correlated systems where standard VQE optimization fails. |

| GGA-VQE [27] | Employs a greedy, gradient-free parameter selection. | Reduces quantum measurements and is highly robust to noise. | Noisy hardware where measurement overhead is a primary bottleneck. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Solutions

This table details key computational "reagents" essential for running VQE experiments on quantum hardware or simulators.

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Optimizer | Finds parameters that minimize the energy measured by the quantum computer. | COBYLA, Nelder-Mead, or SPSA (for noise resilience) [30] [33]. |

| Ansatz Circuit | Parameterized quantum circuit that prepares the trial wavefunction. | Hardware-Efficient (low depth) or UCCSD (chemically accurate) [26]. |

| Qubit Hamiltonian | The molecular Hamiltonian translated into a sum of Pauli operators. | Generated via Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation [26]. |

| Error Mitigation | Techniques to extract accurate results from noisy quantum devices. | Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) and Quantum Autoencoder denoising [7] [26]. |

| Quantum Subspace | A set of quantum states used to approximate the true ground state. | Used in GCIM and QSE methods to avoid direct nonlinear optimization [29]. |

| 3-Ethyl-2,8-dimethylquinolin-4-ol | 3-Ethyl-2,8-dimethylquinolin-4-ol | |

| 1,4-Dibromonaphthalene-2,3-diamine | 1,4-Dibromonaphthalene-2,3-diamine, CAS:103598-22-7, MF:C10H8Br2N2, MW:315.99 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Active Space Approximation and Hamiltonian Downfolding Techniques

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary value of downfolding techniques for researchers working with near-term quantum hardware?

A1: Downfolding techniques, such as those based on Coupled Cluster (CC) and Double Unitary CC (DUCC) ansatzes, are essential for reducing the quantum resource requirements needed to simulate chemical systems [34] [35]. They act as a bridge between accurate ab initio methods and quantum solvers by constructing effective Hamiltonians in a reduced active space [36] [35]. This process integrates out high-energy or less relevant electronic degrees of freedom, allowing you to run simulations on current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices with limited qubits [35]. For instance, these methods enable the calculation of ground-state energy surfaces using Variational Quantum Eigensolvers (VQE) in a much smaller, chemically relevant orbital space [35].

Q2: My downfolded model for a transition metal complex is yielding inaccurate excitation energies. What are the key factors I should investigate?

A2: Comprehensive benchmarking on systems like the vanadocene molecule reveals several sensitive points in the downfolding procedure that can affect accuracy [36]. You should systematically check the following, in order of priority:

- Target-Space Basis Functions: The choice of localized orbitals for the target space has been identified as a key factor influencing the quality of the results [36].

- Double-Counting Corrections: The method used to correct for the interplay between the single-particle term and the two-body interaction term in the Hamiltonian is critical. Orbital-dependent double-counting corrections have been shown to sometimes diminish result quality [36].

- Screening Models: The approach used to model the screening of Coulomb interactions by electrons outside the active space primarily affects crystal-field excitations. Evaluating different constrained screening models, like cRPA, is recommended [36].

Q3: What does the experimental workflow for a hybrid quantum-classical simulation of a molecule look like?

A3: A practical workflow, as demonstrated in a recent supramolecular study, involves a quantum-centric supercomputing approach [37]. The process is iterative:

- Step 1: An initial effective Hamiltonian is prepared on a classical computer, often derived from Density Functional Theory (DFT).

- Step 2: This Hamiltonian is used to define a problem for a quantum processor (e.g., IBM Quantum System One). The quantum device's role is to generate samples of different possible molecular behaviors or states [37].

- Step 3: The samples from the quantum computer are processed by a classical high-performance computer (HPC). This classical post-processing calculates molecular properties, such as energies [37].

- Step 4: The results are fed back to refine the model or parameters for the next iteration. This hybrid loop continues until convergence, significantly reducing the time and cost of computation while tackling scientific bottlenecks [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: The Downfolded Hamiltonian Fails to Reproduce Reference Data

This occurs when the effective model derived from a full ab initio calculation does not match the accuracy of higher-level reference methods for ground-state or excited-state properties.

Diagnosis and Resolution Flowchart The following diagram outlines a systematic approach to diagnose and resolve issues with your downfolded Hamiltonian.

Title: Diagnostic Path for Downfolding Errors

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Against a Vanadocene Ground Truth

Objective: To systematically evaluate the sensitivity of your downfolding procedure by replicating a controlled benchmark on the vanadocene (VCp2) molecule, which provides a well-defined correlated target space [36].

Methodology:

- System Setup: Use the unperturbed eclipsed vanadocene molecule (VCp2) with D5h symmetry as your test system. This molecule has a well-isolated active space of 5 V 3d-dominated molecular orbitals hosting 3 electrons [36].

- Generate Reference Data: Employ highly accurate, systematically improvable many-body wave function methods to establish ground-truth data.

- Recommended Methods: Equation of Motion Coupled Cluster (EOM-CCSD), Auxiliary-Field Quantum Monte Carlo (AFQMC), and Fixed-Node Diffusion Monte Carlo (DMC) [36].

- Convergence: Ensure all calculations are systematically converged with respect to basis sets and other critical parameters.

- Execute Downfolding: Perform your downfolding procedure (e.g., using DFT+cRPA) starting from the same atomic positions and pseudopotentials as the reference methods.

- Solve the Model: Use exact diagonalization on the resulting downfolded model to avoid introducing errors from approximate solvers [36].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Vary one downfolding parameter at a time and compare the eigenstates and energies to the reference. The key parameters to test, in order, are:

Issue: Excessive Qubit Requirements for Quantum Simulations

The number of logical qubits required to simulate your downfolded model exceeds the capacity of current or near-future hardware.

Diagnosis and Resolution Flowchart This path helps you reduce the quantum resource demands of your simulation.

Title: Qubit Reduction Strategy

Protocol 2: Implementing DUCC for Qubit Reduction

Objective: To leverage the Hermitian Double Unitary Coupled-Cluster (DUCC) ansatz to create a smaller, effective Hamiltonian that is suitable for quantum algorithms like VQE and QPE, thereby reducing the number of required qubits [34] [35].

Methodology:

- Hamiltonian Formulation: Use the DUCC formalism to derive a Hermitian effective Hamiltonian. This is expressed in terms of non-terminating expansions of anti-Hermitian cluster operators that integrate out external (non-active) Fermionic degrees of freedom [35].

- Active Space Selection: Define a chemically relevant active space (e.g., frontier orbitals and correlated d-orbitals in a transition metal complex). The accuracy of the final result will depend on this choice.

- Integration with Quantum Solver: The resulting downfolded Hamiltonian, which acts only within the small active space, is then passed to a quantum solver.

- Validation: For a new system, validate the DUCC-reduced model against full classical simulations of small molecules where such calculations are still feasible to ensure the method's integrity [35].

Quantitative Data and Resource Tables

Table 1: Resource Estimates for Selected Chemical Simulations

| Target System / Problem | Classical Method | Estimated Qubits Required (Early Est.) | Refined Qubit Estimates (2025) | Key Downfolding/Algorithmic Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeMoco Cofactor (Nitrogen Fixation) | Classical HPC | ~2.7 million (2021 est.) [9] | ~100,000 (with error-corrected qubits) [10] | Advanced qubit encoding; error correction [10] |

| Cytochrome P450 Enzyme | DFT/Classical Force Fields | Similar to FeMoco [9] | N/A | Quantum simulation demonstrated [10] |

| Vanadocene Molecule (VCp2) | EOM-CCSD, AFQMC, DMC [36] | N/A | Minimal active space (e.g., 5 orbitals) [36] | DFT+cRPA benchmarking; exact diagonalization [36] |

| Supramolecular Systems (e.g., Water Dimer) | Classical ab initio | N/A | Demonstrated on ~100-qubit class processors [37] | Hybrid quantum-classical algorithms [37] |

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Computational "Reagents"

| Research Reagent Solution | Function in Experiment | Example in Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ARTEMIS (Exascale EM Tool) | Models electromagnetic wave propagation and crosstalk in quantum microchips before fabrication [20]. | Used on Perlmutter supercomputer (7,168 GPUs) to simulate a 10mm² quantum chip, optimizing signal coupling [20]. |

| DUCC Effective Hamiltonian | A Hermitian downfolded Hamiltonian that reduces the active space dimensionality for quantum simulations [34] [35]. | Integrated with VQE solvers to calculate ground-state potential energy surfaces on quantum computers, minimizing qubit count [35]. |

| cRPA (constrained RPA) | Calculates the screened Coulomb interaction matrix elements for a target orbital space, avoiding double-counting of screening [36]. | Used in benchmark studies (e.g., vanadocene) to derive interaction parameters (U) for downfolded model Hamiltonians [36]. |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | A hybrid quantum-classical algorithm used to find ground-state energies on NISQ-era quantum processors [9] [35]. | Applied to model small molecules (e.g., Hâ‚‚, LiH) and, combined with downfolding, for more complex systems [9] [35]. |

| Quantum-Centric Supercomputing | A hybrid paradigm where quantum processors and classical HPC work in tandem to solve parts of a problem [37]. | IBM and Cleveland Clinic used it to achieve chemical accuracy for supramolecular interactions (water dimer) [37]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common Quantum Simulation Issues and Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware Limitations | Limited qubit count restricts molecular system size [38] [39] | Quantum processors with low physical qubit numbers | Use active space approximation to reduce problem size; focus on key molecular orbitals [40] |

| High error rates corrupt simulation results [39] [41] | Decoherence, thermal noise, control inaccuracies | Apply quantum error correction codes (e.g., surface code); use error mitigation techniques [39] [41] | |

| Algorithm Implementation | Barren plateaus in training quantum generative models [38] | Gradient vanishing in large parameterized quantum circuits | Utilize quantum circuit Born machines (QCBMs) to help overcome barren plateaus [38] |

| Deep quantum circuits become unreliable [39] | Noise accumulation exceeding coherence times | Employ hybrid quantum-classical algorithms to reduce quantum circuit depth [38] [40] | |

| Chemical Accuracy | Energy profile calculations inaccurate for drug binding | Insufficient basis set or active space | Apply polarizable continuum model (PCM) for solvation effects; increase active space size if possible [40] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Quantum Hardware Constraints

| Constraint | Impact on Drug Discovery Simulations | Workarounds for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Qubit Count (Current: ~1000s physical qubits; Logical: Demonstrations [39] [42]) | Limits complexity of simulatable molecules; KRAS simulation required 16+ qubits [38] | Fragment large molecules; use embedding methods [40] |

| Coherence Time (Tens to hundreds of microseconds [39] [42]) | Restricts depth of executable quantum circuits | Optimize algorithms for shorter circuit depth; use classical co-processors [38] |

| Gate Fidelity (Single-qubit: >99.9%, Two-qubit: ~99% [41] [42]) | Accumulated errors in complex molecular simulations | Implement robust error mitigation; use hardware with higher fidelity gates [41] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the current practical limits for simulating drug molecules on today's quantum computers? Current hardware can handle small active spaces, typically 2 electrons in 2 orbitals for precise calculations, as demonstrated in prodrug activation studies [40]. For generative chemistry, 16-qubit processors have successfully created prior distributions for KRAS inhibitor design [38]. However, simulating full drug-target interactions requires larger systems that still need classical computing support through hybrid approaches.

Q2: How does quantum error correction impact the practical qubit count available for research? Quantum error correction creates a significant overhead. A single logical qubit requires multiple physical qubits for protection—for example, the Shor code uses 9 physical qubits per logical qubit [41]. While recent advancements have shown error rates 800 times better than physical qubits [39], the current limited number of logical qubits means researchers must carefully budget their quantum resources and use hybrid methods.

Q3: What evidence exists that quantum computing can provide advantages in real-world drug discovery? In a published KRAS inhibitor case study, a hybrid quantum-classical model (QCBM-LSTM) showed a 21.5% improvement in passing synthesizability and stability filters compared to classical models alone [38]. This approach led to two experimentally validated drug candidates (ISM061-018-2 and ISM061-022) with measured binding affinity to KRAS-G12D and selective inhibition in cell-based assays [38] [43].

Q4: How do researchers integrate quantum simulations into established drug discovery workflows? The most successful approach uses hybrid pipelines where quantum computers handle specific, computationally demanding tasks. For example, quantum processors can generate prior distributions for generative models or calculate precise energy profiles for key molecular interactions, while classical systems handle data management, filtering, and broader workflow integration [38] [40].

Q5: What are the key technical requirements for simulating covalent bond cleavage in prodrug activation? Accurate simulation requires calculating Gibbs free energy profiles with solvation effects [40] [44]. Researchers use VQE with active space approximation on 2-qubit quantum devices, incorporating polarizable continuum models to simulate aqueous environments. The energy barrier determination is critical for predicting if cleavage occurs under physiological conditions [40].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Hybrid Quantum-Classical Generative Model for KRAS Inhibitors

Objective: Design novel small molecules targeting KRAS protein using quantum-enhanced generative model [38].

Workflow:

- Training Data Compilation:

- Curate 650 known KRAS inhibitors from literature

- Screen 100 million molecules from Enamine REAL library using VirtualFlow 2.0, select top 250,000 by docking scores

- Generate 850,000 structurally similar compounds using STONED algorithm with SELFIES representation

- Apply synthesizability filtering to create final dataset of 1.1 million molecules

Quantum-Classical Generative Modeling:

- Quantum Component: 16-qubit QCBM generates prior distribution, leveraging superposition and entanglement

- Classical Component: LSTM network refines molecular structures

- Reward Function: P(x) = softmax(R(x)) calculated using Chemistry42 or local filters

- Iterative Cycle: Repeated sampling, training, and validation to improve structures

Experimental Validation:

- Sample 1 million compounds from trained models

- Screen for pharmacological viability using Chemistry42

- Rank candidates by docking scores (PLI score)

- Synthesize top 15 candidates for SPR binding assays and cell-based viability tests

Protocol 2: Quantum Simulation of Prodrug Activation via Covalent Bond Cleavage

Objective: Precisely determine Gibbs free energy profile for C-C bond cleavage in β-lapachone prodrug using quantum computation [40].

Workflow:

- System Preparation:

- Select 5 key molecules involved in C-C bond cleavage

- Perform conformational optimization using classical methods

- Apply active space approximation (2 electrons/2 orbitals) to reduce system size

Quantum Computation Setup:

- Transform fermionic Hamiltonian to qubit Hamiltonian using parity transformation

- Implement VQE with hardware-efficient R𑦠ansatz (single layer)

- Apply standard readout error mitigation

- Use 6-311G(d,p) basis set for both classical and quantum computations

Solvation Effects:

- Implement polarizable continuum model (PCM) for water solvation effects

- Perform single-point energy calculations with solvation influence

Energy Profile Construction:

- Calculate energy barrier for C-C bond cleavage

- Compare quantum results with classical references (HF, CASCI) and experimental data

Data Presentation

Table 3: Quantum Hardware Performance in Drug Discovery Applications

| Hardware Metric | Current Capability (2024-2025) | Requirement for Practical Drug Discovery | Impact on Simulation Fidelity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Qubits | ~1000s (e.g., IBM Condor: 1121 qubits [42]) | 10,000+ physical qubits for full error correction [39] | Limits molecular complexity; KRAS simulation used 16 qubits [38] |

| Logical Qubits | Experimental demonstrations (e.g., Google Willow [42]) | 200+ logical qubits (industry target by 2029 [39]) | Essential for fault-tolerant quantum algorithms |

| Error Rates | Physical: 0.1-1%; Logical: 800x improvement demonstrated [39] | Below threshold for deep circuit execution | Determines maximum reliable circuit depth |

| Coherence Times | Tens to hundreds of microseconds [39] [42] | Milliseconds for complex molecular simulations | Limits algorithm complexity and simulation accuracy |

Table 4: Experimental Results from Quantum-Designed KRAS Inhibitors

| Compound | Binding Affinity (SPR) | Biological Activity (IC50) | Selectivity Profile | Toxicity (Cell Viability) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISM061-018-2 | 1.4 μM to KRAS-G12D [38] | Micromolar range across KRAS WT & mutants [38] | Pan-Ras activity (WT & mutants of KRAS, NRAS, HRAS) [38] | No toxicity to HEK293 cells at 30 μM [38] |

| ISM061-022 | Not detected for KRAS-G12D [38] | Micromolar range; enhanced for G12R & Q61H [38] | Selective for KRAS-G12R & Q61H; less potent against HRAS [38] | Mild impact at high concentrations [38] |

Visualization Diagrams

Experimental Workflow for Quantum-Enhanced Drug Discovery

Quantum-Classical Hybrid Algorithm Architecture

VQE for Prodrug Activation Energy Calculation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Materials for Quantum-Enhanced Drug Discovery

| Item | Function | Application in Featured Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Processors (16+ qubits) | Generate prior distributions using quantum effects (superposition, entanglement) [38] | Creating initial molecular structures in QCBM-LSTM model [38] |

| Enamine REAL Library | Provides 100M+ commercially available compounds for virtual screening [38] | Source of training data and validation set for KRAS inhibitors [38] |

| Chemistry42 Platform | Validates pharmacological viability and ranks compounds by docking scores [38] | Filtering generated molecules; calculating reward functions [38] |

| VirtualFlow 2.0 | High-throughput virtual screening software [38] | Screening 100M molecules to select top 250,000 for training [38] |

| STONED Algorithm | Generates structurally similar compounds using SELFIES representation [38] | Data augmentation to create 850,000 additional training molecules [38] |

| Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) | Simulates solvation effects in quantum calculations [40] | Modeling water environment for prodrug activation energy profiles [40] |

| TenCirChem Package | Implements VQE workflow for quantum chemistry [40] | Calculating energy barriers for covalent bond cleavage [40] |

| 1,1,1-Trifluoro-5-bromo-2-pentanone | 1,1,1-Trifluoro-5-bromo-2-pentanone, CAS:121749-67-5, MF:C5H6BrF3O, MW:219 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Formyl-2,6-dimethylbenzoic acid | 4-Formyl-2,6-dimethylbenzoic acid, CAS:306296-76-4, MF:C10H10O3, MW:178.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs: Neutral Atom Hardware for Chemical Simulation

Q1: What are the primary advantages of neutral atom quantum processors for simulating chemical systems?

Neutral atom quantum processors offer several key benefits for chemical simulations:

- Native Multi-Qubit Gates: Unlike most platforms limited to 1- and 2-qubit gates, neutral atoms can natively implement multi-qubit gates like the Toffoli gate through the Rydberg blockade mechanism. This substantially reduces circuit depth for complex molecular simulations, mitigating errors [45].

- Long Coherence Times: Qubits encoded in the hyperfine ground states of neutral atoms can exhibit coherence times exceeding one second, which is crucial for sustained quantum computations [46] [45].

- Field Programmable Qubit Arrays (FPQA): Lasers can rearrange atoms into almost any configuration, allowing qubit connectivity to be adapted to the specific structure of a molecular Hamiltonian, minimizing gate overhead [45].

- Hybrid Operation Modes: They can operate in both analog and digital modes. The analog mode can be less susceptible to error accumulation for specific problems, while the digital mode offers universal programmability [45].

Q2: How does the Rydberg blockade enable multi-qubit gates?

The Rydberg blockade is a physical phenomenon where the excitation of one atom to a high-energy Rydberg state prevents nearby atoms from being excited to the same state due to strong dipole-dipole interactions [45] [47]. This collective inhibition forms the basis for implementing conditional quantum logic. When multiple atoms are within the "blockade radius" of a control atom, a single laser pulse can simultaneously entangle the control with multiple target qubits, enabling native multi-qubit gates that would otherwise require decomposing into many sequential two-qubit gates [45].

Q3: What are the dominant sources of error in neutral atom circuits for chemical calculations?

Key error sources include [48]:

- Gate Errors: Incoherent errors associated with single- and two-qubit (CZ) gates, including errors from Rydberg pulses and dynamical decoupling.

- Idling Errors: Decoherence affecting qubits that are stationary ("sitter" errors) during a computation, or while other qubits are being moved.

- Qubit Transport Errors: Pauli errors applied to qubits that are physically moved ("mover" errors) during a circuit to enable connectivity.

- Atom Loss: Qubits can be lost from their optical traps during the experiment, a dominant challenge in larger arrays [49].

Q4: Which software tools are available for compiling and simulating chemistry problems on neutral atom hardware?

Specialized software tools are available to assist researchers:

- Bloqade: A Python SDK for programming QuEra's neutral atom hardware, supporting both analog Hamiltonian simulation and digital gate-based computation, including noise models for realistic simulation [48].

- Kvantify Qrunch: A domain-specific platform designed for computational chemistry workflows. It abstracts complex quantum operations into an intuitive interface, allowing chemists to build and run quantum algorithms without deep quantum expertise and has demonstrated improved hardware utilization for molecular simulations [50].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High Incoherent Noise in Deep Quantum Circuits

Problem Description: The signal from a quantum circuit designed to estimate molecular ground state energy is suppressed or shows significant bias, likely due to incoherent noise accumulating over many gate operations.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Circuit Simulation with Noise: Use a high-level tool like

bloqade-circuit.cirq_utilsto annotate your quantum circuit with the platform's heuristic noise models (e.g., global/local single-qubit gate error, CZ gate error, mover/sitter error) [48]. - Fidelity Check: Run noisy simulations of your circuit for small, tractable system sizes (e.g., a small molecule fragment) and compare the output fidelity with noiseless simulations to gauge error impact [48].

- Zone Operation Analysis: Simulate your circuit using both one-zone and two-zone operational models. A two-zone model (with separate gate and storage zones) introduces mover errors but may allow for better parallelization; choose the configuration that yields higher simulated fidelity for your specific circuit [48].

Resolution Protocols:

- Protocol 1: Circuit Recompilation with Multi-Qubit Gates

- Objective: Minimize the total number of entangling layers and circuit depth.

- Methodology: Leverage compilation schemes that fuse multiple sequential two-qubit gates into a single, simultaneous multi-qubit entangling gate [51]. For example, replace a sequence of pairwise interactions in a quantum volume-like circuit with a single layer of an Ising-type gate,

UMQ(φ) = exp(i∑φn,m Zn Zm)[51]. - Validation: Compare the quantum volume (QV) of the original and recompiled circuits via simulation. The recompiled version should demonstrate a higher log2(QV), indicating improved performance [51].

- Protocol 2: Dynamical Decoupling Integration

- Objective: Mitigate idling errors on qubits not involved in a given gate operation.

- Methodology: Insert sequences of single-qubit pulses on idling qubits during circuit execution. These pulses refocus the qubits and suppress interactions with the environment [48].

- Validation: Use the processor's noise model to simulate circuits with and without dynamical decoupling sequences. Measure the improvement in state fidelity for benchmark states like GHZ states [48].

Issue: Atom Loss During Error-Correction Cycles

Problem Description: During sustained calculations protected by quantum error correction (QEC), such as those using the surface code, the random loss of atoms from optical tweezers disrupts the stabilizer measurement cycle and can lead to logical failures.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Erasure Identification: Confirm that the hardware/software stack is configured to identify and flag lost atoms (erasure errors) in real-time. This information is easier to correct than unknown errors [49].

- Decoder Check: Verify that the classical decoder processing the stabilizer measurements is optimized to handle erasures, for instance, by using a machine learning-based decoder that can incorporate "superchecks" (products of multiple stabilizers) which remain valid even if individual stabilizers fail due to atom loss [49].

Resolution Protocols:

- Protocol: Logical Teleportation for Qubit Reset

- Objective: Maintain computation integrity despite atom loss.

- Methodology: When an atom is identified as lost, use logical teleportation protocols to transfer the quantum information of the logical qubit to a new, stable physical qubit, effectively resetting the logical qubit without terminating the entire computation [49].

- Validation: Execute repeated rounds of surface code error correction on a logical qubit, intentionally inducing atom loss. The system should successfully complete multiple rounds (e.g., 3+ cycles) without resetting, using teleportation and advanced decoding to maintain logical coherence [49].

Performance Data and Benchmarks

Table 1: Neutral Atom Hardware Performance Metrics

| Metric | Current State-of-the-Art | Significance for Chemical Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Qubit Gate Fidelity | >0.999 [47] | High-fidelity state preparation and rotations are essential for algorithm accuracy. |

| Two-Qubit (CZ) Gate Fidelity | Requires improvement (cited as a challenge) [46] | Lower fidelity is a primary source of error in deep quantum circuits for molecular Hamiltonians. |

| Qubit Coherence Time | Exceeds 1 second [45] | Enables longer, more complex circuits necessary for simulating large molecules. |

| System Size (Physical Qubits) | Up to 448 atoms in a reconfigurable array [49] | Allows for encoding larger molecular systems and implementing quantum error correction. |

| Quantum Error Correction | Multiple rounds of surface code demonstrated on 288-atom blocks [49] | A critical step towards fault-tolerant quantum chemistry calculations. |

Table 2: Circuit Compilation Efficiency: Sequential vs. Multi-Qubit Gates