Noise-Adaptive Optimization for Quantum Computational Chemistry: Strategies for Robust VQE and QAOA on NISQ Hardware

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging noise-adaptive optimization to enhance the performance of quantum computational chemistry on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices.

Noise-Adaptive Optimization for Quantum Computational Chemistry: Strategies for Robust VQE and QAOA on NISQ Hardware

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging noise-adaptive optimization to enhance the performance of quantum computational chemistry on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. We explore the foundational challenges posed by quantum noise in Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA). The scope covers a methodological analysis of emerging noise-adaptive frameworks, including Noise-Directed Adaptive Remapping (NDAR) and overlap-guided ansätze, a practical troubleshooting guide for optimizer selection and error mitigation, and a comparative validation of techniques through recent statistical benchmarking studies. The goal is to bridge the gap between theoretical potential and practical implementation for quantum chemistry simulations in biomedical research.

The Noise Problem: Understanding Quantum Decoherence and Its Impact on Chemical Accuracy

The Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era is defined by quantum processors containing approximately 50 to 1,000 qubits that operate without comprehensive quantum error correction [1] [2]. These devices are characterized by significant noise that fundamentally limits circuit depth and algorithmic complexity. For researchers in quantum computational chemistry, understanding and mitigating the specific challenges of decoherence, gate errors, and sampling noise is paramount to extracting meaningful results from current hardware. This guide provides practical troubleshooting methodologies to navigate these limitations and advance noise-adaptive optimization strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the fundamental noise sources that limit quantum chemistry calculations on NISQ devices?

The primary noise sources are decoherence, gate errors, and measurement (sampling) noise. Decoherence causes qubits to lose their quantum state over time, with typical coherence times (Tâ‚ and Tâ‚‚) ranging from 10-100 microseconds for superconducting qubits [2]. Gate errors occur during quantum operations, with modern devices achieving 99.9% fidelity for single-qubit gates and 99.4-99.9% for two-qubit gates [1] [2]. Measurement errors misreport the final quantum state with typical fidelities of 95-99% [2]. These errors accumulate throughout quantum circuits, particularly impacting deeper algorithms like VQE for molecular simulations.

Q2: How can I determine if my quantum chemistry experiment is feasible on current NISQ hardware?

Estimate the total error probability using metrics like Qubit Error Probability (QEP) [3]. A practical rule of thumb: the product of your circuit depth and number of qubits should not exceed the device's quantum volume before noise dominates the output [2]. For variational algorithms like VQE, ensure the circuit depth allows completion within the qubit coherence time, including optimization iterations.

Q3: Which error mitigation technique should I implement first for molecular energy calculations?

Begin with measurement error mitigation, as it's straightforward to implement and addresses significant error sources [4] [5]. For molecular property calculations like ground state energies, symmetry verification is particularly effective as it exploits conserved quantities like particle number to detect and discard erroneous results [1] [5]. Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) also provides reliable improvements for expectation values needed in quantum chemistry [3] [5].

Q4: My VQE optimization is not converging. Is this due to hardware noise or my ansatz choice?

Hardware noise frequently causes barren plateaus and false minima in VQE optimization landscapes [1]. Diagnose this by comparing results across multiple devices with different noise profiles, implementing progressively stronger error mitigation techniques to observe if convergence improves, and testing your ansatz with noiseless simulation to isolate the issue [3] [4].

Troubleshooting Guides & Experimental Protocols

Diagnosing and Mitigating Decoherence

Symptoms: Results degrade significantly with increased circuit depth, inconsistent results between runs, measurements show faster-than-expected thermalization.

Diagnosis Protocol:

- Check device calibration reports for Tâ‚ and Tâ‚‚ times before each experiment [2]

- Run simple benchmarking circuits of varying depths to isolate coherence-limited performance

- Compare results for algorithms with similar gate counts but different execution times

Mitigation Strategies:

- Circuit Optimization: Design shallower circuits using commutation rules and optimal compilation [2]

- Dynamical Decoupling: Apply sequences of pulses to idle qubits to suppress environmental noise [6]

- Algorithm Selection: Prefer variational algorithms with minimal coherent depth requirements

Addressing Gate Errors

Symptoms: Consistent systematic errors in measurements, violation of known physical symmetries, poor reproducibility across different qubit layouts.

Diagnosis Protocol:

- Review gate fidelity metrics from recent device calibration data [2]

- Implement randomized benchmarking for specific qubit pairs used in your circuits

- Test with simple circuits that have known theoretical outcomes

Mitigation Strategies:

- Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE): Artificially increase circuit noise by stretching gates or inserting identities, then extrapolate back to zero noise [1] [3] [5]

- Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC): Implement quasi-probability decompositions to invert known error channels [1] [5]

- Qubit Selection: Use device calibration data to preferentially utilize higher-fidelity qubits and connections [3]

Managing Sampling Noise

Symptoms: High variance in repeated measurements, requirement for excessive shots to converge expectation values, inconsistent energy calculations in VQE.

Diagnosis Protocol:

- Characterize measurement error matrices for your target qubits [4] [5]

- Run classical simulations to determine fundamental shot noise limits for your circuit

- Compare empirical variance to theoretical lower bounds

Mitigation Strategies:

- Measurement Error Mitigation: Construct confusion matrix and invert it during post-processing [4] [5]

- Readout Calibration: Use dedicated techniques to correct for biased readout errors [2]

- Shot Allocation Optimization: Distribute measurement shots based on operator importance rather than uniform sampling

Quantitative Data Reference

Table 1: Typical NISQ Hardware Performance Metrics [2]

| Metric | Typical Value Range | Impact on Chemistry Calculations |

|---|---|---|

| T₠(Relaxation Time) | 20-100 μs | Limits total circuit execution time |

| T₂ (Dephasing Time) | 10-50 μs | Constrains coherent algorithm depth |

| Single-Qubit Gate Fidelity | 99.8-99.9% | Affects basis rotation accuracy in ansatz circuits |

| Two-Qubit Gate Fidelity | 99.4-99.9% | Impacts entanglement creation in correlated electron models |

| Measurement Fidelity | 95-99% | Introduces errors in expectation value measurements |

| Single-Qubit Error Rate | ~10â»Â³ | Contributes to cumulative circuit error |

| Two-Qubit Error Rate | ~3×10â»Â³ | Primary source of error in entanglement operations |

Table 2: Error Mitigation Techniques Comparison [1] [3] [4]

| Technique | Best For | Measurement Overhead | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Error Mitigation | Readout noise reduction | Low (2-5x) | Low |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | Gate error mitigation in shallow circuits | Moderate (3-5x) | Medium |

| Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC) | High-accuracy results with good noise models | High (10-100x) | High |

| Symmetry Verification | Quantum chemistry with conserved quantities | Low-Moderate (2-10x) | Medium |

| Dynamical Decoupling | Decoherence-limited circuits | Low (1.5-2x) | Low |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Zero-Noise Extrapolation for Molecular Energy Calculations

Purpose: Extract more accurate ground state energies from noisy VQE computations.

Procedure:

- Circuit Preparation: Implement your ansatz circuit for molecular Hamiltonian

- Noise Scaling: Create 3-5 circuit variants with intentionally scaled noise levels using:

- Pulse stretching (if available)

- Gate repetition (insert identity operations)

- Unified noise amplification methods

- Execution: Run each scaled circuit on the quantum processor with sufficient shots

- Extrapolation: Fit measured energies vs. noise scale factor using linear, polynomial, or exponential models

- Extraction: Extrapolate to zero noise to obtain mitigated energy estimate

Protocol 2: Symmetry Verification for Quantum Chemistry

Purpose: Detect and correct errors that violate physical symmetries in molecular simulations.

Procedure:

- Symmetry Identification: Determine conserved quantities in your molecular system (particle number, spin, etc.)

- Check Circuit Design: Implement quantum circuits to measure symmetry operators concurrently with your main computation

- Execution: Run the complete circuit including symmetry measurement

- Post-Selection: Discard results where symmetry measurements indicate error occurrence

- Re-normalization: Compute expectation values using only symmetry-conforming results

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for NISQ-Era Quantum Chemistry

| Tool/Technique | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | Molecular ground state energy calculation | Hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for electronic structure [1] |

| Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) | Combinatorial optimization for chemical configuration | Approximate solutions for molecular conformation problems [1] |

| Qubit Error Probability (QEP) Metric | Pre-execution error estimation for circuit design | Predicts circuit success probability before QPU execution [3] |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | Post-processing error mitigation | Extrapolates observable expectations to zero-noise limit [3] [5] |

| Dynamical Decoupling | Decoherence suppression during idle periods | Pulse sequences to protect qubit states between operations [6] |

| Measurement Error Mitigation | Readout error correction | Confusion matrix inversion for improved measurement fidelity [4] [5] |

| (D-Leu6,pro-nhet9)-lhrh (4-9) | (D-Leu6,Pro-NHEt9)-LHRH (4-9)|Research Peptide | (D-Leu6,Pro-NHEt9)-LHRH (4-9) is a polypeptide for research use. Explore its applications in biochemical assay development. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| 3'-Hydroxy Simvastatin | 3'-Hydroxy Simvastatin, MF:C25H38O6, MW:434.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why does my VQE optimization converge to poor local minima or appear to get stuck? Your VQE is likely experiencing one of two key issues related to noise. First, noise-induced local minima occur when hardware noise creates false variational minima in the energy landscape that trap optimization algorithms [7]. Second, you may be encountering barren plateaus, where gradients vanish exponentially with system size, making parameter updates ineffective [8] [9]. Quantum noise exacerbates both problems by distorting the true energy landscape and creating deceptive optimization pathways.

FAQ 2: How can I determine if poor VQE results come from algorithm failure or hardware noise? Implement a multi-step diagnostic procedure:

- Run noiseless simulations using state vector simulators to establish baseline performance [10]

- Compare energy trajectories between noisy and noiseless executions - significant deviation indicates noise dominance [11]

- Check parameter consistency - noisy environments cause high variance in optimized parameters across repeated runs [12]

- Monitor gradient magnitudes - consistently near-zero gradients suggest barren plateaus [8]

FAQ 3: What optimization strategies work best for noisy VQE landscapes? Metaheuristic algorithms generally outperform traditional methods under noise conditions. Adaptive metaheuristics like CMA-ES and iL-SHADE demonstrate particular resilience by maintaining population diversity and avoiding noise-induced traps [7]. For gradient-based approaches, consider tracking population means rather than best individuals to counter the "winner's curse" statistical bias [7]. The table below summarizes optimizer performance comparisons from recent studies:

Table: Optimizer Performance in Noisy VQE Environments

| Optimizer Class | Example Algorithms | Noise Resilience | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Metaheuristics | CMA-ES, iL-SHADE | High | Most effective and resilient strategies [7] |

| Swarm-based | PSO, SOMA | Medium-High | Collective behavior helps navigate noisy landscapes [8] |

| Evolution-based | DE, Genetic Algorithms | Medium | Population diversity aids escape from local minima [8] |

| Gradient-based | SLSQP, BFGS | Low | Struggle with distorted gradients, diverge or stagnate [7] |

| Traditional | COBYLA, SPSA | Low-Medium | Limited success in locating global minima under noise [8] |

FAQ 4: What quantum error mitigation techniques specifically address VQE landscape distortion? Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) effectively reduces noise impact by extrapolating measurements from intentionally noise-amplified circuits back to the zero-noise limit [10]. Twirled Readout Error Extinction (T-REx) provides cost-effective readout error mitigation, improving VQE accuracy by an order of magnitude in experimental tests [12]. For comprehensive mitigation, combine circuit-level techniques like T-REx with noise-adaptive algorithms such as Noise-Directed Adaptive Remapping (NDAR), which transforms noise attractors into solution-improvement mechanisms [13].

FAQ 5: How does ansatz choice influence susceptibility to noise-induced landscape problems? Ansatz structure critically determines noise vulnerability. Hardware-efficient ansatzes with deep circuits accumulate more noise and exacerbate barren plateaus [8]. Chemistry-inspired ansatzes like UCCSD benefit from physical constraints but still suffer from noise [11] [9]. Recent approaches using subspace optimization partition ansatzes into principal and auxiliary subspaces, restricting variational optimization to lower-dimensional components while reconstructing auxiliary parameters classically - this provides 1-2 orders of magnitude better minima estimation [9].

Quantitative Analysis of Noise Impact on VQE Performance

Table: Experimental Data on Noise Effects and Mitigation Efficacy

| Experimental Condition | System Size | Key Metric | Performance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard QAOA (without NDAR) | 82 qubits | Approximation Ratio | 0.34-0.51 | [13] |

| QAOA with Noise-Directed Adaptive Remapping | 82 qubits | Approximation Ratio | 0.90-0.96 | [13] |

| Unmitigated Readout Errors | 5-qubit molecular systems | Energy Estimation Accuracy | Order of magnitude less accurate | [12] |

| With T-REx Mitigation | 5-qubit molecular systems | Energy Estimation Accuracy | Significant improvement | [12] |

| Standard VQE Optimization | Varies | Convergence to True Minima | Often fails due to noise traps | [9] [7] |

| Subspace Optimization with ASC | Varies | Energy Landscape Navigation | 1-2 orders of magnitude improvement | [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Noise Characterization and Mitigation

Protocol 1: Noise-Directed Adaptive Remapping (NDAR)

NDAR transforms detrimental noise into an algorithmic asset by iteratively gauge-transforming the cost-function Hamiltonian [13]:

- Initialization: Run variational optimization to obtain initial candidate solution

- Remapping: Take the best bitstring from previous step and remap cost Hamiltonian to logically equivalent encoding

- Transformation: Transform noise attractor into better candidate solution based on previous results

- Iteration: Repeat remapping to make noise attractor progressively higher-quality solution

This protocol effectively uses asymmetric noise (like amplitude damping) to guide optimization, demonstrated on Rigetti's Ankaa-2 with 82-qubit fully-connected graphs achieving approximation ratios of 0.9-0.96 at only depth p=1 QAOA [13].

Protocol 2: Energy Landscape Plummeting with Subspace Optimization

This approach mitigates barren plateaus and local traps through dimensional reduction [9]:

- Ansatz Partitioning: Divide ansatz parameters into principal subspace (lower-dimensional) and auxiliary subspace (higher-dimensional) based on temporal hierarchy

- Restricted Optimization: Perform variational optimization only on principal subspace using standard optimizers

- Auxiliary Reconstruction: Reconstruct auxiliary parameters without variational optimization using adiabatic approximation

- Correction Application: Apply auxiliary subspace corrections (ASC) to plummet energy landscape toward more optimal minima

This method reduces quantum resource requirements while significantly improving convergence to global minima.

Protocol 3: Zero-Noise Extrapolation with Real Hardware Calibration

Implement ZNE using actual device noise characteristics [10]:

- Noise Model Construction: Build noise model using calibration data from target quantum processor (e.g., IQM Garnet via Amazon Braket)

- Circuit Execution: Run VQE circuits at multiple noise amplification levels using noise-aware simulators or actual hardware

- Extrapolation: Fit measurements to noise model and extrapolate to zero-noise limit using Mitiq or similar libraries

- Validation: Compare mitigated results with noiseless simulations to assess efficacy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Resources for Noise-Resilient VQE Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Error Mitigation Libraries | Mitiq, T-REx | Implement ZNE and readout error mitigation [12] [10] |

| Hybrid Quantum Cloud Platforms | Amazon Braket Hybrid Jobs | Provides priority QPU access and managed classical compute [10] |

| Quantum Programming Frameworks | PennyLane, Braket SDK | Define variational algorithms and interface with hardware [10] |

| Metaheuristic Optimizers | CMA-ES, iL-SHADE, PSO | Navigate noisy, multimodal landscapes [8] [7] |

| Noise Characterization Tools | Gate set tomography, process tomography | Quantify and model realistic noise channels [11] [10] |

| Subspace Optimization Methods | Principal-auxiliary partitioning, ASC | Reduce dimensionality and mitigate barren plateaus [9] |

| Noise-Adaptive Algorithms | NDAR | Leverage noise attractors for improvement [13] |

| 1,5,6-trihydroxy-3-methoxyxanthone | 1,5,6-trihydroxy-3-methoxyxanthone, CAS:50868-52-5, MF:C14H10O6, MW:274.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ethyl 3-oxoheptanoate | Ethyl 3-oxoheptanoate, CAS:7737-62-4, MF:C9H16O3, MW:172.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

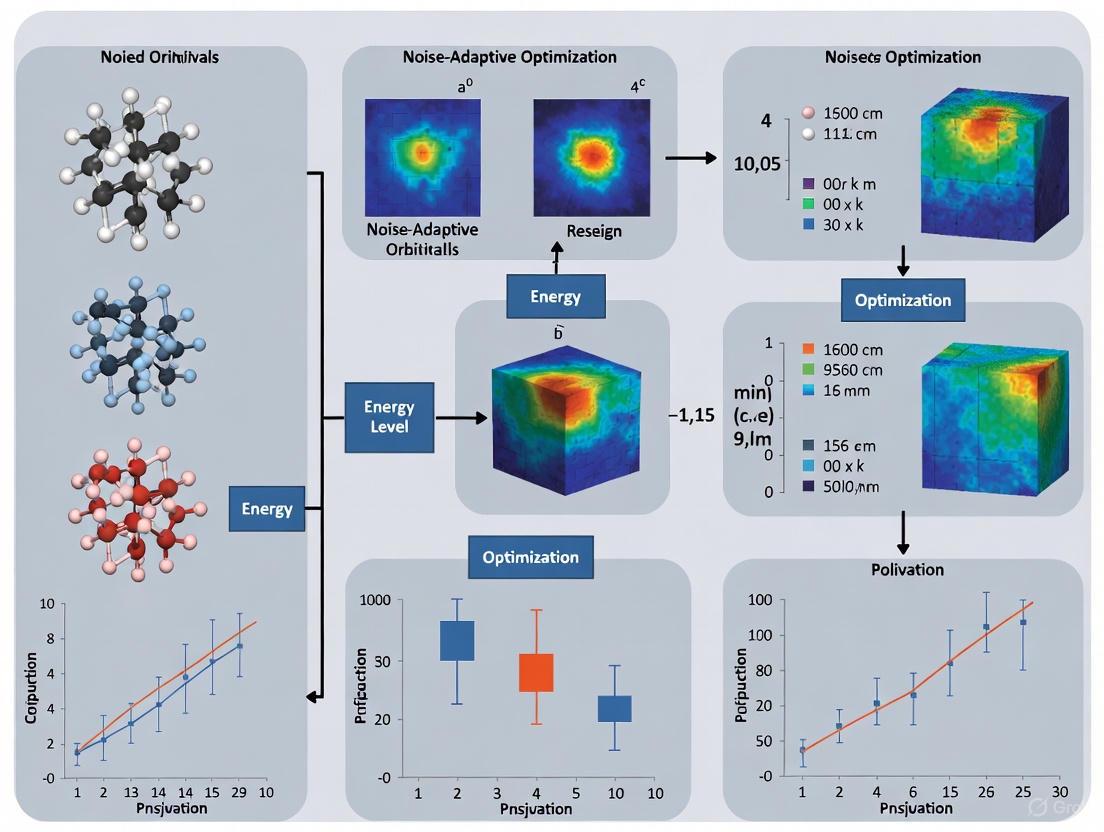

Workflow Visualization: Noise-Resilient VQE Optimization

Noise-Resilient VQE Workflow

Noise Impact and Mitigation Pathways

FAQs: Addressing Common Researcher Questions on Hâ‚‚ Quantum Simulations

This section answers frequently asked questions about using the Hâ‚‚ molecule in noisy quantum computing environments.

Q1: Why is the Hâ‚‚ molecule such a common benchmark for quantum chemistry algorithms? The Hâ‚‚ molecule is a cornerstone for benchmarking quantum algorithms due to its simplicity and the exact knowledge of its properties. Its small, well-understood electronic structure allows researchers to focus on algorithm performance, noise susceptibility, and error mitigation strategies without the computational overhead of larger molecules. It serves as an ideal testbed for validating methods like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) before scaling to more complex systems [14].

Q2: What are the most significant types of noise affecting VQE calculations for Hâ‚‚ on NISQ devices? The primary noise sources include depolarizing noise, which introduces significant randomness in quantum states; dephasing noise, which causes loss of phase coherence; amplitude damping, which models energy dissipation; gate errors from imperfect quantum operations; and measurement noise during qubit readout. Among these, depolarizing noise is often the most detrimental, while measurement noise typically has a comparatively milder effect [15].

Q3: My VQE optimization for Hâ‚‚ is stagnating or converging to an incorrect energy value. What could be wrong? This is a classic symptom of noise-induced optimization challenges. Finite-shot sampling noise can distort the cost landscape, create false variational minima, and induce a statistical bias known as the "winner's curse" [7]. It is often recommended to move away from simple gradient-based optimizers (e.g., SLSQP, BFGS) in noisy regimes and instead use adaptive metaheuristic strategies like CMA-ES or iL-SHADE, which have demonstrated greater resilience [7].

Q4: How can I reduce the number of qubits needed to simulate Hâ‚‚ with larger basis sets? Orbital optimization and active space selection techniques are crucial. The RO-VQE (Random Orbital-VQE) algorithm is a promising approach that employs a randomized procedure for selecting and optimizing orbitals from a larger basis set. This allows you to retain much of the accuracy of an expansive basis while reducing the number of required qubits, fitting the simulation within hardware constraints [16].

Troubleshooting Guides: Identifying and Mitigating Specific Issues

Use this guide to diagnose and resolve common experimental problems.

Symptom 1: Inaccurate Ground State Energy

- Problem: The computed ground state energy of Hâ‚‚ deviates significantly from the theoretical value, even with a seemingly converged VQE optimization.

- Potential Causes:

- Noise-distorted landscape: Quantum noise distorts the energy landscape, trapping the optimizer in a false minimum [7].

- Inadequate error mitigation: Basic error mitigation techniques are not applied or are insufficient for the current noise level.

- Suboptimal ansatz or optimizer: The chosen parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) or classical optimizer is not suited for the noisy environment.

- Resolution Protocol:

- Switch Optimizers: Replace gradient-based optimizers (like BFGS) with noise-resilient, adaptive metaheuristics such as CMA-ES [7].

- Implement Hybrid Error Mitigation: Apply a combination of:

- Validate with Single-Qubit Reduction: For a sanity check, confirm that your results are consistent with a simplified, single-qubit simulation of Hâ‚‚, which can be more noise-resistant [14].

Symptom 2: Unstable Optimization and Failure to Converge

- Problem: The VQE energy values fluctuate wildly across optimization steps, and the algorithm fails to converge to a stable solution.

- Potential Causes:

- Resolution Protocol:

- Adopt Population-Based Strategies: Use population-based optimizers (e.g., iL-SHADE) and track the population mean energy instead of the best individual's energy to correct for the "winner's curse" bias [7].

- Integrate Adaptive Policy Guidance: For Quantum Reinforcement Learning (QRL) approaches, use Adaptive Policy-Guided Error Mitigation (APGEM) to dynamically adjust the learning policy based on reward trends, stabilizing training under noise fluctuations [15].

Symptom 3: High Measurement Overhead and Cost

- Problem: The number of measurements (shots) required to obtain a precise energy estimate is prohibitively large, making the experiment infeasible.

- Potential Causes:

- Inefficient measurement strategy: Measuring each Pauli term in the Hamiltonian independently without grouping.

- Ignoring problem symmetries: Not leveraging molecular symmetries to reduce the number of terms that need to be measured.

- Resolution Protocol:

- Employ Pauli Saving: Use techniques like "Pauli saving" in subspace methods (e.g., quantum Linear Response) to significantly reduce the number of measurements required [17].

- Apply Qubit Tapering: Exploit the symmetries of the Hâ‚‚ molecular Hamiltonian to reduce the number of qubits needed for the simulation, which automatically reduces the number of terms to measure [16].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Noise on Hâ‚‚

Here are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in noise analysis studies.

Protocol 1: VQE Energy Calculation with a Two-Qubit and Single-Qubit System

- Objective: Calculate the ground state energy of the Hâ‚‚ molecule and verify the results under noise.

- Methodology:

- Hamiltonian Preparation: Map the electronic Hamiltonian of Hâ‚‚, derived in a minimal basis set (e.g., STO-3G), to a qubit Hamiltonian using the Jordan-Wigner transformation [16] [14].

- Ansatz Selection: Prepare the trial wavefunction using the Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) ansatz, implemented as a parameterized quantum circuit [14].

- Hybrid Optimization: On a quantum processor, measure the expectation value of the Hamiltonian. Use a classical computer to update the circuit parameters (θ) to minimize the energy [14].

- Single-Qubit Validation: Implement a reduced-order model that simulates the Hâ‚‚ molecule using only a single qubit to verify the results with fewer resources and potentially higher accuracy under noise [14].

Protocol 2: Randomized Orbital Optimization VQE (RO-VQE)

- Objective: Reduce qubit requirements for Hâ‚‚ simulations with larger basis sets while maintaining accuracy.

- Methodology:

- Orbital Pool Generation: Start with a large basis set (e.g., 6-31G or cc-pVTZ) that would normally require

Mqubits [16]. - Randomized Selection: Instead of systematically selecting orbitals based on Hartree-Fock energies (as in OptOrbVQE), employ a randomized procedure to select a smaller active space of

Norbitals (where N < M) [16]. - Orbital Optimization: Use a partial unitary matrix to rotate the orbital basis, optimizing the selected active space for the VQE calculation.

- Energy Calculation: Perform the standard VQE algorithm on the reduced

N-qubit system to obtain the ground state energy [16].

- Orbital Pool Generation: Start with a large basis set (e.g., 6-31G or cc-pVTZ) that would normally require

Performance Data and Benchmarking

Table 1: Benchmarking Classical Optimizers for VQE under Noise on Hâ‚‚ Systems

| Optimizer Type | Examples | Performance under Noise on Hâ‚‚ | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-Based | SLSQP, BFGS | Diverges or stagnates [7] | Sensitive to noise-distorted gradients. |

| Adaptive Metaheuristics | CMA-ES, iL-SHADE | Most effective and resilient [7] | Handles noisy, non-convex landscapes effectively. |

| Population-Based | iL-SHADE (with mean tracking) | Effective, avoids "winner's curse" [7] | Tracking population mean corrects for statistical bias. |

Table 2: Comparing Error Mitigation Techniques for Quantum Algorithms

| Mitigation Technique | Mechanism | Applicability to Hâ‚‚ Simulations | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | Extrapolates results from different noise scales to zero noise [15]. | Yes, general purpose | Requires running circuits at elevated noise levels. |

| Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC) | Applies corrective operations based on a known noise model [15]. | Yes, general purpose | Requires precise noise characterization; increases sampling overhead. |

| Adaptive Policy (APGEM) | Adjusts the learning policy based on reward trends in QRL [15]. | For Quantum Reinforcement Learning | Algorithm-level mitigation; stabilizes learning trajectories. |

| Pauli Saving | Reduces the number of measurements in subspace methods [17]. | Yes, for quantum linear response | Cuts measurement cost, which directly reduces noise. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Workflow for Hâ‚‚ Noise Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Computational "Reagents" for Hâ‚‚ Quantum Experiments

| Item / Solution | Function in Experiment | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Hardware Simulator | Provides a simulated noisy quantum environment for testing and development. | Qiskit AerSimulator with configurable noise models [15]. |

| VQE Framework | The core algorithmic framework for hybrid quantum-classical energy calculation. | Includes ansatz (e.g., UCCSD), classical optimizer, and measurement routines [14]. |

| Error Mitigation Suite | A collection of techniques to reduce the impact of noise on results. | A hybrid framework integrating ZNE, PEC, and APGEM [15]. |

| Orbital Optimization Package | Enables qubit reduction by selecting an optimized active space from a larger basis. | RO-VQE algorithm for randomized orbital selection [16]. |

| Molecular Integral Software | Computes the one- and two-electron integrals for the molecular Hamiltonian. | Used to generate the Hâ‚‚ Hamiltonian coefficients in a chosen basis set [16]. |

| D-Lactose monohydrate | D-Lactose monohydrate, CAS:5989-81-1, MF:C12H22O11.H2O, MW:360.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Biliverdin hydrochloride | Biliverdin hydrochloride, CAS:55482-27-4, MF:C33H36Cl2N4O6, MW:655.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is Layer Fidelity and why is it a fundamental metric? Layer Fidelity (LF) is a practical and efficient metric used to characterize the strength of noise in a quantum circuit. It is essentially equal to the probability that no error occurs during the execution of one layer of a quantum circuit. It is a fundamental metric because it directly determines the sampling overhead, which is the number of additional times a circuit must be run to obtain a reliable, error-mitigated result. A lower LF means a higher noise level, which in turn requires an exponentially greater number of samples to mitigate errors effectively [18].

How does the cost of error mitigation become exponential? The sampling overhead for advanced error mitigation techniques like Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC) scales exponentially with the number of qubits and the circuit depth. This relationship is often expressed as a factor of ( \gamma^L ), where ( \gamma ) is a parameter related to the noise strength (and connected to the Layer Fidelity, with ( 1/\sqrt{\gamma} ) representing the probability of no error), and ( L ) is the number of layers. This means that as the problem size or complexity grows, the number of required samples grows exponentially, quickly becoming impractical [18].

What is the difference between quantum error correction and quantum error mitigation? Quantum Error Correction (QEC) is a proactive approach that uses multiple physical qubits to form a single, more stable logical qubit. It can actively detect and correct errors during computation but requires a large overhead of additional qubits, making it infeasible for current NISQ devices. In contrast, Quantum Error Mitigation (QEM) is a post-processing technique applied to the results of noisy quantum computations. It does not require extra qubits but instead uses multiple runs of the same noisy circuit and classical post-processing to infer a less noisy result, making it the primary strategy for NISQ-era quantum computing [19].

Why do state preparation errors pose a particular challenge for readout error mitigation? Conventional measurement error mitigation methods often assume that state preparation errors are negligible. However, in reality, State Preparation and Measurement (SPAM) errors are hard to distinguish. When using the inverse of the measurement error matrix for mitigation, any state preparation error gets mixed in and amplified. This introduces a systematic error that itself grows exponentially with an increasing number of qubits, leading to a significant overestimation of performance metrics like the fidelity of large-scale entangled states [20].

How can the Conditional Value at Risk be used for error mitigation? The Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR) is an alternative loss function that can be more robust to noise. Instead of using the standard expectation value, CVaR uses the average of the top ( \alpha ) percent of best samples (e.g., the lowest energy states for a Hamiltonian). It can be shown that the CVaR of noisy samples can provide provable bounds on the true, noise-free expectation value. This approach can achieve a substantially lower sampling overhead (( \sqrt{\gamma} )) compared to the more exponential cost (( \gamma^2 )) of PEC for a similar task [18].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Over-Estimated Fidelity in Entangled State Preparation

- Problem: After applying standard readout error mitigation, the reported fidelity of a prepared graph state or GHZ state is suspiciously high and does not align with other indicators of performance.

- Diagnosis: This is a likely symptom of unaccounted state preparation errors being amplified by the standard measurement error mitigation process. As detailed in search results, this mixture of SPAM errors leads to a systematic deviation that grows exponentially with qubit count [20].

- Solution:

- Benchmark Separately: Independently characterize the state preparation error rate for your system if possible.

- Use a Unified Model: Employ a mitigation matrix ( \Lambda ) that explicitly accounts for both initialization and measurement errors, rather than just the inverse of the measurement matrix ( M^{-1} ). The mitigation matrix for each qubit should be constructed as: ( \Lambdai = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{1-qi}{1-2qi} & \frac{-qi}{1-2qi} \ \frac{-qi}{1-2qi} & \frac{1-qi}{1-2qi} \end{pmatrix} Mi^{-1} ) where ( qi ) is the initialization error rate and ( Mi ) is the readout error matrix [20].

- Set an Error Budget: Be aware of the upper bound for acceptable state preparation error as a function of system size to keep the final deviation within tolerable limits [20].

Unmanageable Sampling Overhead in VQE Calculations

- Problem: The number of shots required to mitigate errors for a Variational Quantum Eigensolver experiment is too high to be practically feasible, halting research.

- Diagnosis: You are likely hitting the fundamental exponential wall of error mitigation. The sampling cost for techniques like PEC scales as ( \gamma^{2L} ), where ( \gamma ) is related to your device's Layer Fidelity [18].

- Solution:

- Switch to a Frugal Method: For estimating expectation values, consider using the Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR) loss function, which has a provably lower sampling overhead of ( \sqrt{\gamma} ) [18].

- Use Chemistry-Inspired Mitigation: For quantum chemistry problems, leverage methods like Reference-State Error Mitigation (REM) or its multireference extension (MREM). These use classically computable reference states to calibrate out errors with low sampling overhead, as they exploit problem structure [21].

- Optimize Training Data: If using learning-based mitigation like Clifford Data Regression (CDR), carefully choose the training data and exploit problem symmetries to improve efficiency by an order of magnitude [22].

optimizer Divergence or Stagnation Due to Shot Noise

- Problem: The classical optimizer in a variational quantum algorithm (VQE, QAOA) fails to converge, appears to get stuck, or converges to a manifestly poor solution.

- Diagnosis: Finite-shot sampling noise distorts the cost landscape, creating false local minima and causing a statistical bias known as the "winner's curse." Furthermore, gradient-based optimizers are particularly vulnerable to the noisy estimates of the gradient [23].

- Solution:

- Choose a Robust Optimizer: Benchmark and use adaptive metaheuristic optimizers like CMA-ES or iL-SHADE, which have been shown to be more effective and resilient under noisy conditions compared to many gradient-based methods [23].

- Mitigate the "Winner's Curse": When using population-based optimizers, track the population mean energy rather than just the best individual's energy to correct for the downward bias of the best-sample estimate [23].

- Increase Shot Count Strategically: Consider dynamically increasing the number of measurement shots as the optimization progresses and gets closer to a suspected minimum.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Metrics & Methodologies

Key Metrics for Error Mitigation Scaling

The following table summarizes the core metrics that determine the feasibility of error mitigation.

| Metric | Formula/Relationship | Interpretation | Experimental Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Layer Fidelity (LF) | ( \text{LF} = \text{Probability(no error in a layer)} ) | A direct measure of the noise level per circuit layer. A higher LF is better. | Determines the base sampling overhead for all error mitigation techniques [18]. |

| Sampling Overhead (PEC) | ( \text{Overhead} \propto \gamma^{2L} ) | The number of samples needed for PEC scales exponentially with noise strength (\gamma) and circuit depth (L). | The primary bottleneck for large-scale applications; can become astronomically high [18]. |

| Sampling Overhead (CVaR) | ( \text{Overhead} \propto \sqrt{\gamma} ) | The number of samples for a provable bound via CVaR scales much more favorably. | Makes obtaining bounds on expectation values practical on near-term devices [18]. |

| SPAM-induced Deviation | ( \text{Deviation} \propto (1 + c)^n ) | The systematic error from unaccounted state prep errors can grow exponentially with qubit count (n) and a constant (c) [20]. | Can lead to over-optimistic fidelity estimates in multi-qubit experiments if not properly modeled [20]. |

| L-Histidine dihydrochloride | L-Histidine dihydrochloride, CAS:6027-02-7, MF:C6H11Cl2N3O2, MW:228.07 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| DMT-dU-CE Phosphoramidite | DMT-dU-CE Phosphoramidite, CAS:289712-98-7, MF:C39H47N4O8P, MW:730.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Layer Fidelity

Purpose: To empirically determine the Layer Fidelity of a quantum device, which is critical for estimating the sampling overhead of error mitigation. Principle: The Layer Fidelity can be efficiently estimated using a protocol that essentially measures the probability of no error occurring, which is directly related to the parameter ( \gamma ) used in sampling overhead calculations (( 1/\sqrt{\gamma} \approx \text{LF} )) [18].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Circuit Design: Select a set of benchmark circuits. These are typically random or structured circuits of a specific depth (d).

- Twirled Mirroring: For each benchmark circuit (U), construct a corresponding "mirror" circuit (U^\dagger). Then, implement this sequence: (U^\dagger U), which ideally should be the identity operation.

- Execution and Measurement: Run the (U^\dagger U) circuit on the quantum device. The initial state is typically (|0\rangle^{\otimes n}). Measure the output in the computational basis.

- Success Counting: Count the number of times the output state is the exact initial state (|00...0\rangle). The frequency of this outcome across many shots is the estimated Layer Fidelity for a circuit of depth (2d).

- Averaging: Repeat steps 1-4 for many different circuit instances to get a reliable average LF for the device.

This measured LF can then be used in the formulas in Table 1 to project the sampling cost for your specific experimental circuits.

Experimental Protocol: Multireference Error Mitigation for Strong Correlation

Purpose: To extend the power of reference-state error mitigation (REM) to strongly correlated molecular systems where a single Hartree-Fock reference state is insufficient. Principle: Multireference-state error mitigation (MREM) uses a compact wavefunction composed of a few dominant Slater determinants (a multireference state) that has substantial overlap with the true, strongly correlated ground state. The error is mitigated by comparing the noisy quantum result with the exact classical energy for this multireference state [21].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Generate Multireference State: Use an inexpensive classical method (e.g., CASSCF, selected CI) to generate a compact multireference wavefunction (|\psi_{MR}\rangle) for your target molecule (e.g., F2 in a bond-stretching region).

- Circuit Preparation: Prepare this multireference state on the quantum processor. A pivotal and efficient method is to use a quantum circuit constructed from Givens rotations, which preserves physical symmetries like particle number [21].

- Energy Evaluation:

- On Quantum Computer: Measure the energy (E{MR}^{(\text{noisy})}) of the prepared (|\psi{MR}\rangle) using the VQE algorithm on the noisy hardware.

- On Classical Computer: Compute the exact energy (E{MR}^{(\text{exact})}) of (|\psi{MR}\rangle) using classical methods.

- Error Calibration: The error for the reference state is ( \Delta{MR} = E{MR}^{(\text{noisy})} - E_{MR}^{(\text{exact})} ).

- Mitigate Target State: Prepare and measure the energy (E{\text{target}}^{(\text{noisy})}) of your full VQE target state (e.g., using a more expressive ansatz) on the quantum computer. The error-mitigated energy is then: ( E{\text{mitigated}} = E{\text{target}}^{(\text{noisy})} - \Delta{MR} ).

Conceptual Diagrams

Error Mitigation Scaling Relationships

MREM Workflow for Strong Correlation

Adaptive Algorithms in Action: From Noise-Resilient VQEs to Problem Remapping

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental principle that distinguishes NAQAs from traditional error mitigation? NAQAs operate on a fundamentally different principle: instead of attempting to suppress or correct noise, they actively exploit the inherent noise dynamics of the quantum processor to guide the optimization process. This is often done by aggregating information from multiple noisy outputs to adapt the original optimization problem, effectively using noise as a resource to steer the algorithm toward better solutions [24].

Q2: My variational algorithm (like VQE) is converging to a high-energy state. Could noise be the cause, and how can a NAQA help? Yes, noise can bias the optimization landscape, trapping algorithms in high-energy local minima. A NAQA framework like Noise-Directed Adaptive Remapping (NDAR) can help. NDAR iteratively identifies the noise "attractor state" and applies gauge transformations to the cost Hamiltonian, effectively reassigning lower energy values to states the hardware can more readily produce, thus breaking out of these noisy traps [24] [25].

Q3: For quantum computational chemistry, how can I make my parameterized quantum circuit (PQC) more resilient to noise without changing the hardware? The QuantumNAS framework addresses this by performing a noise-adaptive co-search of the variational circuit ansatz and its qubit mapping. It uses a trained "SuperCircuit" to efficiently evaluate many candidate circuit architectures (SubCircuits) under realistic noise models, automatically identifying a circuit structure that is inherently more robust to the specific noise present on your target device [26].

Q4: Are NAQAs only suitable for optimization problems, or can they be applied to quantum computational chemistry tasks like ground state energy estimation? While many NAQAs were developed for optimization (e.g., based on QAOA), the core principles are directly applicable to quantum chemistry. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is a primary algorithm for ground state energy problems. Integrating a NAQA approach with VQE, such as using noise-adaptive remapping or circuit search (QuantumNAS), can significantly improve the accuracy and reliability of energy estimations on noisy hardware [27] [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Solution Quality Despite Optimized Parameters

Problem Description: After running a variational algorithm (e.g., QAOA or VQE), the solution quality, measured by approximation ratio or energy estimation, is poor and does not meet expectations, even after extensive parameter tuning.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Verify Baseline Performance: Run the standard, non-adaptive version of your algorithm on the noisy simulator or hardware and record the baseline solution quality [25].

- Check for Attractor State Dominance: Analyze the distribution of multiple output samples. If the results are heavily biased towards a specific classical state (e.g.,

|0...0⟩), this indicates a strong attractor state that the algorithm is struggling to overcome [24] [25]. - Inspect Correlation Across Samples: For consensus-based methods, check if certain qubits or variables show strong correlation across many samples. A lack of consensus may indicate the noise is overwhelming the problem signal [24].

Solutions:

- Implement NDAR: If a dominant attractor state is identified, integrate the Noise-Directed Adaptive Remapping loop. This will iteratively transform the problem Hamiltonian to align the attractor with better solutions [25].

- Apply Quantum-Enhanced Greedy Fixing: Use multiple noisy samples to calculate correlation measures and fix the values of the most strongly correlated variables, then re-solve the reduced problem [24].

Issue 2: Unstable Learning and Convergence in Noisy Environments

Problem Description: The classical optimizer in a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm (like VQE or QRL) fails to converge stably, with the cost function or reward showing high variance and unpredictable jumps.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Identify Noise Type: Characterize the dominant noise type on your hardware (e.g., depolarizing, amplitude damping, measurement noise) as different noises affect learning dynamics differently [15].

- Monitor Reward Trend: Track the moving average of the reward or cost function. Erratic behavior under noise is a key indicator [15].

Solutions:

- Deploy a Hybrid Error Mitigation Framework: Integrate a combination of techniques like Zero Noise Extrapolation (ZNE), Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC), and Adaptive Policy-Guided Error Mitigation (APGEM). This multi-layered approach can stabilize the learning process [15].

- Leverage Noise-Adaptive Circuit Search: Use QuantumNAS to replace your default ansatz with a noise-resilient circuit architecture specifically searched for your problem and hardware profile [26].

Issue 3: Excessive Runtime Due to Computational Overhead

Problem Description: The NAQA procedure is effective but introduces significant computational overhead, making experiments prohibitively slow.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Profile the Workflow: Identify the most time-consuming step (e.g., sample generation, problem adaptation, re-optimization) [24].

- Check Adaptation Complexity: For methods that fix variables or perform remapping, check if the analysis step (e.g., calculating correlations) has a scalable implementation [24].

Solutions:

- Optimize the Sampling Step: Ensure the quantum program (circuit) is compiled efficiently for the target hardware to minimize queue time and execution time.

- Use a Multilevel Approach: For large-scale problems, adopt a hierarchical strategy that first solves a reduced problem and then refines the solution, which can drastically speed up convergence [24].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Implementing the NDAR Algorithm for Optimization

This protocol outlines the steps for applying Noise-Directed Adaptive Remapping to a QAOA workflow for a combinatorial optimization problem [25].

Workflow Diagram: NDAR for QAOA

Methodology:

- Initialization: Begin with the original cost Hamiltonian, H, and set the initial gauge transformation to the identity.

- Sample Generation: Run the QAOA circuit (or other stochastic optimizer) with the current Hamiltonian to obtain a set of noisy sample bitstrings.

- Identify Best Solution: From the sampled bitstrings, select the one with the lowest cost (highest quality) relative to the original problem.

- Problem Adaptation (Gauge Transformation): Calculate a new bitflip gauge

ybased on the best solution and the known noise attractor state (e.g.,|0...0⟩). The transformationP_yis applied to the Hamiltonian:H^y = P_y H P_y[25]. - Re-optimization: Use the transformed Hamiltonian

H^yfor the next iteration's sample generation. The noise attractor is now aligned with a better solution. - Termination: Iterate steps 2-5 until the solution quality meets a target threshold or stops improving.

Key Quantitative Results from NDAR Implementation: Table: NDAR Performance on Rigetti QPU (n=82 qubits, QAOA p=1) [25]

| Metric | Standard QAOA | QAOA with NDAR | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approximation Ratio | 0.34 – 0.51 | 0.9 – 0.96 | ~88% increase |

| Key Mechanism | Noise negatively impacts convergence | Noise attractor is guided toward better solutions | Exploitation of noise |

Protocol 2: QuantumNAS for Robust Circuit Design

This protocol describes using the QuantumNAS framework to find a noise-resilient parameterized quantum circuit for a quantum chemistry problem like VQE [26].

Workflow Diagram: QuantumNAS Framework

Methodology:

- SuperCircuit Construction: Define a large, over-parameterized quantum circuit (the SuperCircuit) composed of multiple layers of parameterized gates.

- SuperCircuit Training: Train the entire SuperCircuit by iteratively sampling smaller SubCircuits (e.g., by masking gates) and updating their parameters. This decouples circuit search from parameter training [26].

- Noise-Adaptive Co-Search: Perform an evolutionary search over SubCircuits and their qubit mappings. The performance of each candidate is estimated using parameters inherited from the SuperCircuit and evaluated under a realistic device noise model.

- Iterative Pruning: The best-found circuit is further refined by pruning redundant gates and fine-tuning the remaining parameters to enhance efficiency and performance.

Key Quantitative Results from QuantumNAS: Table: QuantumNAS Performance on QML and VQE Tasks [26]

| Task | Benchmark | Performance Achievement |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Machine Learning (QML) | 2-class classification | >95% accuracy on real quantum computer |

| 4-class classification | >85% accuracy on real quantum computer | |

| 10-class classification | >32% accuracy on real quantum computer | |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | Hâ‚‚, LiH, Hâ‚‚O, CHâ‚„, BeHâ‚‚ molecules | Achieved the lowest ground state energy eigenvalue compared to UCCSD ansatz |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational "Reagents" for NAQA Research

| Item Name | Function & Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Bitflip Gauge Transformation (P_y) | A unitary operator that remaps the problem Hamiltonian by redefining the |0⟩ and |1⟩ states for a set of qubits. It preserves the eigenvalue spectrum but permutes the eigenvectors [25]. |

Core component of the NDAR algorithm, used to adaptively align the noise attractor with better solutions [25]. |

| SuperCircuit | A large, pre-trained parameterized quantum circuit that contains many smaller SubCircuits within its architecture. It allows for efficient performance estimation of candidate circuits without training each from scratch [26]. | Foundation of the QuantumNAS framework, enabling scalable and noise-adaptive circuit architecture search [26]. |

| Dynamic Noise Adaptation (DNA) Network | A neural network (e.g., using bidirectional LSTM) that predicts short-term noise trajectories of quantum hardware from historical telemetry data, enabling proactive circuit compilation [28]. | Used in advanced compilation tools like DeepQMap to predict and adapt to temporal noise variations in multi-chip quantum systems [28]. |

| Hybrid Error Mitigation (APGEM-ZNE-PEC) | A combination of Adaptive Policy-Guided Error Mitigation (APGEM), Zero Noise Extrapolation (ZNE), and Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC) applied in concert [15]. | Provides a robust mitigation stack to stabilize Quantum Reinforcement Learning (QRL) and other iterative algorithms under realistic noise conditions [15]. |

| Methyl 19-methyleicosanoate | Methyl 19-methyleicosanoate, CAS:95799-86-3, MF:C22H44O2, MW:340.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Hydroxyl emodin-1-methyl ether | 2-Hydroxyl emodin-1-methyl ether, CAS:346434-45-5, MF:C16H12O6, MW:300.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Noise-Directed Adaptive Remapping (NDAR) is a heuristic algorithm designed to approximately solve binary optimization problems by leveraging specific types of noise found in quantum processors, rather than mitigating them [29] [13]. This approach is particularly valuable in the context of noise-adaptive optimization for quantum computational chemistry, where simulating molecular systems often requires finding the ground state energy of complex Hamiltonians—a task that can be formulated as a binary optimization problem [30] [31].

The core idea of NDAR is to exploit the fact that the noisy dynamics of a quantum processing unit (QPU) often have a global attractor state, typically the |0⋯0⟩ state [25] [32]. Instead of treating this noise as a detriment, NDAR bootstraps this attractor state. It iteratively applies gauge transformations (bitflip transforms) to the cost-function Hamiltonian, effectively remapping the problem so that the noise attractor state is transformed into progressively higher-quality solutions [29] [13]. This turns a fundamental hardware limitation into a computational asset, aligning the quantum optimization process with the device's native noise dynamics.

Key Concepts and Definitions

The Cost Hamiltonian

In quantum optimization for chemistry, the problem of interest (e.g., finding a molecular ground state) is often mapped to a diagonal cost Hamiltonian, H, of the form [25] [32]:

H = Σ_i h_i Z_i + Σ_{i<j} J_{ij} Z_i Z_j + ...

Here, Z_i is the Pauli Z operator on qubit i, h_i represents local field strengths, and J_{ij} represents interaction strengths between qubits i and j.

Bitflip Transforms (Gauge Transformations)

A bitflip transform is a unitary operation defined by a bitstring y and given by P_y = ⨂_{i=0}^{n-1} X_i^{y_i}, where X_i is the Pauli X operator on qubit i [25] [32]. Applying this transform to the cost Hamiltonian creates a new, logically equivalent Hamiltonian, H^y:

H^y = P_y H P_y = Σ_i (-1)^{y_i} h_i Z_i + Σ_{i<j} (-1)^{y_i + y_j} J_{ij} Z_i Z_j + ...

This transformation preserves the eigenvalue spectrum of H but permutes its eigenvectors. Critically, it changes the computational basis state that corresponds to a given solution. After this transformation, the former attractor state |0...0⟩ is mapped to the new state |y_0 ... y_{n-1}⟩ [25].

The NDAR Algorithm: A Step-by-Step Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the iterative feedback loop at the heart of the NDAR algorithm.

- Initialization: The algorithm begins with the noise attractor state,

|0...0⟩, and an initial problem Hamiltonian,H[13] [32]. - Variational Optimization Loop: A variational quantum algorithm (e.g., QAOA) is run on the current problem Hamiltonian,

H^y. The quantum computer samples from the output distribution to find a candidate solution bitstring [29] [25]. - Solution Extraction: The best solution bitstring,

s*, from the current run is identified. - Adaptive Remapping: The cost Hamiltonian is remapped using a bitflip transform where the bitstring

yis set to the best solutions*. This creates a new Hamiltonian,H^{new y} = P_{s*} H P_{s*}. This crucial step reassigns the energy value of the attractor state|0...0⟩to be equal to the energy of the previous best solution,s*[13] [25]. - Iteration: Steps 2-4 are repeated. With each iteration, the noise naturally drives the system toward the

|0...0⟩state, which now corresponds to a solution that is at least as good as the best solution from the previous run. - Termination: The loop continues until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., no improvement in solution quality after a set number of iterations). The final best solution is then output [29].

Experimental Protocol & Performance Data

Reference Experiment: QAOA with NDAR on Rigetti's Ankaa-2

A key experimental demonstration of NDAR involved implementing a p=1 QAOA (a low-depth circuit with just one layer of phase and mixer operators) to minimize fully-connected, randomly-weighted Sherrington-Kirkpatrick model Hamiltonians [13] [25].

- Objective: Minimize a given cost Hamiltonian.

- Hardware: A

n=82-qubit subsystem of Rigetti Computing's Ankaa-2 superconducting transmon QPU [13]. - Algorithm: Standard

p=1QAOA was compared againstp=1QAOA enhanced with the NDAR outer loop. - Metric: Approximation ratio (a value between 0 and 1, where 1 is the optimal solution).

- Constraint: Both methods were allocated an identical number of total circuit runs (function calls) for a fair comparison [29] [13].

Quantitative Performance Results

The table below summarizes the performance gains achieved by integrating NDAR with a shallow QAOA circuit.

| Metric | Standard QAOA (p=1) | QAOA with NDAR (p=1) | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approximation Ratio | 0.34 - 0.51 [29] | 0.9 - 0.96 [29] [13] | ~2x |

Problem Size (n) |

82 qubits [13] | 82 qubits [13] | Same |

Circuit Depth (p) |

1 [13] | 1 [13] | Same |

This data demonstrates that NDAR can dramatically enhance the performance of a low-depth, noisy quantum optimizer, achieving high approximation ratios where the standard algorithm fails [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details the essential "research reagents"—the core components and their functions—required to implement NDAR in an experimental setting.

| Item | Function / Definition | Role in NDAR Protocol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noisy QPU with Global Attractor | A quantum processor whose inherent noise dynamics bias the system toward a specific classical state (e.g., | 0...0⟩ for amplitude damping) [13]. | Provides the physical platform and the "resource" (the attractor state) that NDAR exploits. |

Cost Hamiltonian (H) |

A diagonal operator encoding the optimization problem, e.g., a molecular energy surface [31]. | Defines the target problem to be solved. Serves as the input for the gauge transformation process. | |

Bitflip Transform (P_y) |

A unitary operation P_y = ⨂_i X_i^{y_i} that performs a basis change on qubits specified by the bitstring y [25] [32]. |

The core tool for logically remapping the problem Hamiltonian in each iteration of the algorithm. | |

| Variational Solver (e.g., QAOA) | A parameterized quantum circuit that prepares a trial state, which is measured to estimate the expected value of H [33] [31]. |

The inner-loop subroutine that generates candidate solutions to inform the next adaptive remapping step. | |

| 7-(6'R-Hydroxy-3',7'-dimethylocta-2',7'-dienyloxy)coumarin | 7-(6'R-Hydroxy-3',7'-dimethylocta-2',7'-dienyloxy)coumarin, CAS:118584-19-3, MF:C19H22O4, MW:314.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | |

| 5,7,2',6'-Tetrahydroxyflavone | 5,7,2',6'-Tetrahydroxyflavone, CAS:82475-00-1, MF:C15H10O6, MW:286.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What types of quantum hardware noise is NDAR compatible with? NDAR is specifically designed to leverage asymmetric noise that has a well-defined classical attractor state, such as amplitude damping towards the |0⟩ state [13] [25]. It is not designed for generic, unstructured noise.

Q2: Can NDAR be used with algorithms other than QAOA? Yes. While the initial demonstrations used QAOA, the authors emphasize that NDAR is a higher-level algorithmic framework. The variational optimization component can be replaced with other quantum or even classical stochastic solvers, such as other types of Ising machines [25] [32].

Q3: How does NDAR differ from "gauge searching" in quantum annealing? The use of bitflip transforms (gauges) has been used in annealing, often selected at random or via a separate search [25] [32]. NDAR is conceptually different: it iteratively and adaptively selects the gauge based on the best solution from the previous run and, most importantly, is directed by the known noise model of the hardware [25].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution / Verification Step | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor convergence | The variational solver parameters are not being optimized effectively for the remapped problem. | Verify the classical optimizer's performance independently. Consider re-using or slightly perturbing parameters from previous successful iterations as a "warm start" [25]. | |

| Attractor state not dominant | The hardware noise may not have a strong or global attractor, or the circuit may be too short for the attractor dynamics to take effect. | Characterize the native noise dynamics of your QPU. Run simple characterization circuits to confirm the presence and strength of the | 0...0⟩ attractor. |

| Solution quality plateaus | The algorithm may have found a local optimum from which the simple greedy remapping cannot escape. | Implement a more sophisticated remapping strategy, such as occasionally exploring non-greedy transforms to escape local optima, similar to techniques in classical optimization. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between ADAPT-VQE and Overlap-ADAPT-VQE? ADAPT-VQE grows the ansatz by selecting operators that yield the largest energy gradient, making it susceptible to local energy minima and leading to over-parameterized circuits [34] [35]. Overlap-ADAPT-VQE avoids this by constructing the ansatz to maximize its overlap with an intermediate target wavefunction that already captures electronic correlation, guiding the construction away from local minima and producing more compact circuits [34] [36].

Q2: What types of target wavefunctions can be used to guide the Overlap-ADAPT-VQE procedure? The algorithm is flexible but typically uses classically computed wavefunctions that capture strong correlation. A highly effective choice is a Selected Configuration Interaction (SCI) wavefunction, such as one generated by the CIPSI (Configurations Interaction by Perturbative Selection Iterated) method [35]. In proof-of-concept studies, the exact Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) wavefunction has also been used as the target [34].

Q3: My Overlap-ADAPT ansatz has converged. What is the recommended next step? The compact ansatz produced by the overlap-guided procedure is designed to be used as a high-accuracy initialization for a subsequent ADAPT-VQE run [34] [36]. This hybrid approach leverages the compactness of the overlap-built ansatz to start the energy-based ADAPT-VQE closer to the true ground state, helping it avoid early plateaus and further improving the final result.

Q4: How does Overlap-ADAPT-VQE specifically help with noise resilience on NISQ devices? Its primary contribution is circuit-depth reduction. By producing ultra-compact ansätze, it directly addresses two major constraints of NISQ devices [34]:

- Reduced Decoherence: Shallower circuits are executed faster, minimizing the impact of decoherence.

- Fewer Measurements: Fewer parameters and operators mean the subsequent variational optimization requires fewer measurements, which is critical given the limited number of shots on real hardware [37].

Q5: For which molecular systems are the advantages of Overlap-ADAPT-VQE most pronounced? The benefits are most significant for strongly correlated systems where the standard ADAPT-VQE is most prone to getting stuck in energy plateaus. Notable examples from literature include stretched (dissociated) molecular geometries like BeH₂ and linear H₆ chains [34] [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Slow Convergence of the Overlap Value

Problem The overlap between the growing ansatz and the target wavefunction is increasing very slowly, requiring many iterations and leading to a deep circuit.

Possible Causes and Solutions

- Cause: Inadequate Target Wavefunction. The chosen target wavefunction may not be a good approximation of the true ground state.

- Solution: Use a higher-accuracy classical method to generate the target wavefunction. For example, increase the selection threshold in an SCI calculation or use a larger active space [35].

- Cause: Restricted Operator Pool. The pool of available unitary operators might be missing important correlations.

- Solution: Review the composition of your operator pool. Ensure it includes all relevant types of excitations (e.g., singles, doubles) for your system. Consider using a qubit-excitation-based pool for more efficient circuit implementation [34].

Issue 2: Final Energy is Not Chemically Accurate

Problem After completing the Overlap-ADAPT procedure and a final ADAPT-VQE refinement, the energy error is above the chemical accuracy threshold (1.6 mHa).

Possible Causes and Solutions

- Cause: Insufficient Classical Optimization. The classical optimizer may have stagnated in a local minimum during the final ADAPT-VQE phase.

- Solution: Use robust optimizers like BFGS and ensure convergence criteria are tight enough. Consider running the optimization from different initial parameter guesses to check for consistency [38].

- Cause: Over-compact Initial Ansatz. The overlap-guided ansatz might be too short to serve as a good starting point for the final ADAPT-VQE.

- Solution: Run the Overlap-ADAPT procedure for more iterations before switching to the energy-based criterion, ensuring the overlap value is sufficiently high (e.g., >0.99) [34].

Issue 3: High Measurement Overhead During Ansatz Construction

Problem The process of evaluating operator gradients for the selection criterion requires an impractically large number of quantum measurements.

Possible Causes and Solutions

- Cause: Naive Gradient Evaluation. Measuring each gradient term independently is inherently costly.

- Solution: Implement advanced measurement techniques that can reduce overhead. This can include using classical shadows, grouped measurement strategies, or methods that allow for simultaneous evaluation of multiple gradients [37].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Implementing the Core Overlap-ADAPT-VQE Algorithm

The following workflow details the steps to construct a compact ansatz using the overlap-guided method.

Protocol 2: Hybrid Overlap-ADAPT to ADAPT-VQE Switching Protocol

This protocol describes how to transition from the overlap-guided phase to the energy minimization phase.

- Run Overlap-ADAPT-VQE: Execute the workflow in Protocol 1 until the overlap with the target wavefunction reaches a predefined convergence threshold (e.g.,

1 - |⟨ψ(θ)|Ψ_target⟩|² < ε_overlap). - Switch Cost Function: Change the cost function from overlap maximization to energy minimization:

E(θ) = ⟨ψ(θ)|H|ψ(θ)⟩. - Continue with ADAPT-VQE: Using the current ansatz and parameters as the initial point, resume the standard ADAPT-VQE algorithm:

- At each iteration, compute the energy gradient for all operators in the pool.

- Select and append the operator with the largest energy gradient magnitude.

- Re-optimize all parameters to minimize the energy.

- Final Convergence: Continue until the energy gradient norm falls below a threshold (

||∇E|| < ε_energy), signaling convergence to the ground state.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for Overlap-ADAPT-VQE compared to standard ADAPT-VQE, as reported in proof-of-concept studies [34] [35].

Table 1: Performance Comparison for Strongly Correlated Molecules

| Molecular System | Algorithm | Number of Operators to Reach Chemical Accuracy | Reported Circuit Depth (CNOT Count) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretched Linear H₆ | QEB-ADAPT-VQE | >150 iterations | >1000 CNOTs | Baseline |

| Overlap-ADAPT-VQE | ~50 iterations | Not Explicitly Reported | ~3x reduction in iterations [35] | |

| Stretched BeHâ‚‚ | k-UpCCGSD (fixed ansatz) | N/A | >7000 CNOTs | Baseline |

| ADAPT-VQE | N/A | ~2400 CNOTs | >65% reduction in CNOTs [34] | |

| Overlap-ADAPT-VQE | Not Explicitly Reported | Substantial further savings | Further compaction vs. ADAPT [34] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Classical CI Solver | Generates the target wavefunction |Ψ_target⟩. |

CIPSI is highly effective [35]. Other SCI or full-CI solvers can be used. |

| Operator Pool | A set of unitary operators {A_i} used to grow the ansatz. |

Often consists of fermionic or qubit-based single and double excitations. A restricted pool (occupied to virtual only) speeds up selection [34]. |

| Overlap Evaluation Routine | Computes |⟨ψ(θ)|Ψ_target⟩|² between the quantum ansatz and classical target. |

Can be computed using the swap test or other efficient algorithms on a quantum computer. In classical simulations, the statevector is directly available. |

| Classical Optimizer | Finds parameters θ that maximize the overlap or minimize the energy. |

BFGS is commonly used in noiseless simulations [38]. For noisy hardware, noise-resilient optimizers are recommended. |

| Qubit Hamiltonian | The molecular electronic Hamiltonian mapped to qubit operators. | Generated via tools like OpenFermion with PySCF [34] [38], using Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation. |

| Tosufloxacin tosylate hydrate | Tosufloxacin tosylate hydrate, CAS:1400591-39-0, MF:C26H25F3N4O7S, MW:594.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Collagen proline hydroxylase inhibitor | Collagen proline hydroxylase inhibitor, CAS:223666-07-7, MF:C18H18N4O4, MW:354.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Leveraging Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR) for Robust Expectation Value Bounds

In near-term quantum devices, inherent noise significantly compromises the accuracy of calculated expectation values, which are fundamental to variational quantum algorithms used in computational chemistry and drug development. This technical guide explores the application of Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR), a risk measure from quantitative finance, to establish provable bounds on noise-free expectation values. By focusing on the tail of the measurement outcome distribution, the CVaR approach provides a scalable noise-management strategy with a lower sampling overhead compared to traditional error mitigation techniques like Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC), offering a practical path toward more reliable quantum simulations on current hardware [39].

# CVaR in Quantum Computation: Core Concepts

### What is Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR)?

Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR), also known as Expected Shortfall, is a spectral risk measure that quantifies the expected loss in the worst-case scenarios beyond a specified confidence level [40]. In finance, if Value at Risk (VaR) indicates the potential loss threshold, CVaR estimates the average loss exceeding that threshold, providing a more comprehensive view of tail risk [40].

### How is CVaR Applied to Quantum Computing?

In the context of quantum computation, the "loss" is redefined as the energy outcome of a quantum measurement. For a parameterized quantum circuit, the standard approach is to use the expected value (average) of all measurement outcomes as the cost function. In contrast, the CVaR method uses the average of only the worst-performing fraction of outcomes [39]. This focus on the lower tail of the energy distribution makes the optimization process more robust to noisy results that can randomly produce over-optimistic, low-energy values.

### Quantitative Comparison: CVaR vs. Traditional Methods

The table below summarizes key performance differences, as demonstrated in experiments on real quantum devices [39] [29].

| Feature | Traditional Expectation Value | CVaR-Based Estimation | Traditional Error Mitigation (e.g., PEC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noise Handling | Averages all noise effects | Bounds noise-free value by focusing on tail | Aims to fully correct for noise |

| Sampling Overhead | Low | Moderate | Exponentially high |

| Result Guarantees | None | Provable bounds on true value | Accurate correction in ideal case |

| Best Use Case | Low-noise systems | Noisy devices, optimization tasks | Small-scale circuits where overhead is tolerable |

# Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

### Q1: Why should I use CVaR over traditional error mitigation like PEC or ZNE?

A: The primary advantage is drastically reduced sampling overhead. Techniques like Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC) and Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) require a number of samples that grows exponentially with system size, making them infeasible for large-scale problems. CVaR, by contrast, provides provable bounds on noise-free values with a substantially lower and more scalable sampling cost [39]. It is ideal when your goal is to find a good solution (e.g., a low-energy molecular state) rather than perfectly characterizing the entire quantum system.

### Q2: How do I choose the correct alpha (α) parameter for my CVaR-VQE experiment?

A: The α parameter sets the confidence level and defines the tail of the distribution used for the CVaR calculation (e.g., α=0.5 uses the best 50% of samples).

- Start with a moderate value (e.g., α=0.25): This is often a good balance between noise resilience and convergence speed [41].

- If results are too noisy: Decrease α (e.g., to 0.1) to focus on a smaller set of the best outcomes. This increases robustness but may slow down optimization.

- Troubleshooting Tip: If your optimization is stuck, try gradually increasing α toward 0.5 over several iterations to smooth the optimization landscape.

### Q3: My CVaR-VQE optimization is converging to a poor local minimum. What can I do?

A: This can be a sign of a "barren plateau" or an ill-conditioned optimization landscape.

- Ansatz Choice: Consider using a problem-inspired ansatz (like the k-UpCCGSD for quantum chemistry) instead of a hardware-efficient one, as it may offer a more structured landscape [41].

- Classical Optimizer: Use robust classical optimizers that are less prone to getting stuck in local minima. Protocols in recent studies often employ optimizers like COBYLA or SPSA for this purpose [41].

- Initial Parameters: Utilize parameter initialization strategies specific to your problem to start closer to a good solution.

### Q4: In portfolio optimization, a major pitfall is inaccurate input data. Does this affect robust CVaR in quantum chemistry?

A: Yes, the principle is analogous. In quantum chemistry, the "input data" is often the measured energy from a noisy quantum device. While robust optimization in finance protects against uncertain asset returns [42] [43], in quantum computation, the CVaR method itself acts as a robust filter against the "uncertainty" introduced by noise. By focusing on the tail of measurements, it inherently reduces the impact of unreliable, noisy outliers, providing more stable and trustworthy results for downstream tasks like molecular dynamics comparison [41].

# Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

### Protocol 1: Implementing CVaR-VQE for Molecular Ground State Energy

This protocol outlines the steps to find the ground state energy of a molecule using CVaR-VQE [41].

- Problem Formulation:

- Map the electronic structure problem of your target molecule to a qubit Hamiltonian (H) using a transformation like Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev.

- Circuit Preparation:

- Select a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz). For molecular systems, a problem-inspired ansatz like UCCSD is often preferred.

- Algorithm Execution:

- For a given set of parameters θ, prepare the state |ψ(θ)⟩ and measure the energy (the Hamiltonian H) in the computational basis. Repeat this for a fixed number of

shots(e.g., 1000). - From the set of all measurement outcomes, select the subset corresponding to the (1-α) best (lowest) energy values.

- Compute the CVaR cost function as the mean of this subset.

- For a given set of parameters θ, prepare the state |ψ(θ)⟩ and measure the energy (the Hamiltonian H) in the computational basis. Repeat this for a fixed number of

- Classical Optimization:

- Use a classical optimizer (e.g., SLSQP, COBYLA) to adjust the parameters θ to minimize the CVaR cost function.

- Iterate until convergence is reached.

### Protocol 2: Fidelity Estimation Between Quantum States

Accurately estimating the fidelity between a prepared noisy state (Ï) and a target pure state (|ψ⟩) is critical for validating quantum simulations. The CVaR method provides reliable bounds for this task [39].

- Measurement Strategy:

- For the target state |ψ⟩, define an observable O = |ψ⟩⟨ψ|.