Optimizing Gradient Measurements in Adaptive VQE: Advanced Strategies for Quantum Chemistry and Drug Discovery

Adaptive Variational Quantum Eigensolvers (ADAPT-VQE) are promising for molecular simulation on near-term quantum devices but face a critical bottleneck: the overwhelming measurement overhead required for gradient-based operator selection and parameter...

Optimizing Gradient Measurements in Adaptive VQE: Advanced Strategies for Quantum Chemistry and Drug Discovery

Abstract

Adaptive Variational Quantum Eigensolvers (ADAPT-VQE) are promising for molecular simulation on near-term quantum devices but face a critical bottleneck: the overwhelming measurement overhead required for gradient-based operator selection and parameter optimization. This article synthesizes the latest advancements in mitigating this challenge. We explore the foundational principles of adaptive VQEs, detail novel gradient-free and quantum-aware optimizers like GGA-VQE and ExcitationSolve, and analyze practical strategies for shot-efficient measurement reuse and allocation. Through comparative validation across molecular systems and multi-orbital models, we provide a roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to implement these techniques, enhancing the feasibility of quantum-accelerated discovery in the NISQ era.

The Adaptive VQE Landscape: Why Gradient Measurement is a Critical Bottleneck

Core Principles of ADAPT-VQE and the Operator Selection Process

The Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) is an iterative, hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed to construct efficient, problem-tailored wavefunction ansätze for molecular simulations on quantum computers. It was developed to address critical limitations of standard VQE approaches, particularly the use of fixed, often over-parameterized ansätze like unitary coupled cluster (UCCSD), which can result in quantum circuits that are prohibitively deep for current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices [1] [2]. By dynamically building a compact ansatz, ADAPT-VQE achieves faster convergence, enhanced accuracy, and improved robustness against noise and errors [3].

This protocol details the core principles and operator selection process of ADAPT-VQE, with a specific focus on the central challenge of gradient measurement optimization. Efficiently evaluating the gradients used to select operators is a major bottleneck for the practical application of ADAPT-VQE on real hardware, driving a significant body of contemporary research [4] [5].

Core Algorithmic Principles

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm improves upon fixed-ansatz VQE by growing a circuit ansatz iteratively, adding operators that most effectively lower the energy at each step [3]. The fundamental workflow is as follows:

- Initialization: The algorithm begins with a simple reference state, typically the Hartree-Fock (HF) determinant ( |\Psi_{\mathrm{HF}}\rangle ) [2].

- Iterative Growth: For each iteration ( k ), the current ansatz state is ( |\Psi^{(k-1)}\rangle ).

- Gradient Measurement: The energy gradient with respect to each operator ( A_m ) in a pre-defined operator pool is computed [2].

- Operator Selection: The operator with the largest gradient magnitude is selected.

- Ansatz Update: The selected operator, parameterized by a new variational angle ( \thetak ), is appended to the ansatz: ( |\Psi^{(k)}\rangle = e^{\thetak A_m} |\Psi^{(k-1)}\rangle ) [2].

- Variational Optimization: All parameters ( {\theta1, ..., \thetak} ) in the new, longer ansatz are optimized to minimize the energy expectation value ( \langle \Psi^{(k)}| H |\Psi^{(k)}\rangle ) [4].

- Convergence Check: Steps 2-6 repeat until the norm of the gradient vector falls below a predefined threshold ( \epsilon ), indicating convergence to the ground state [2].

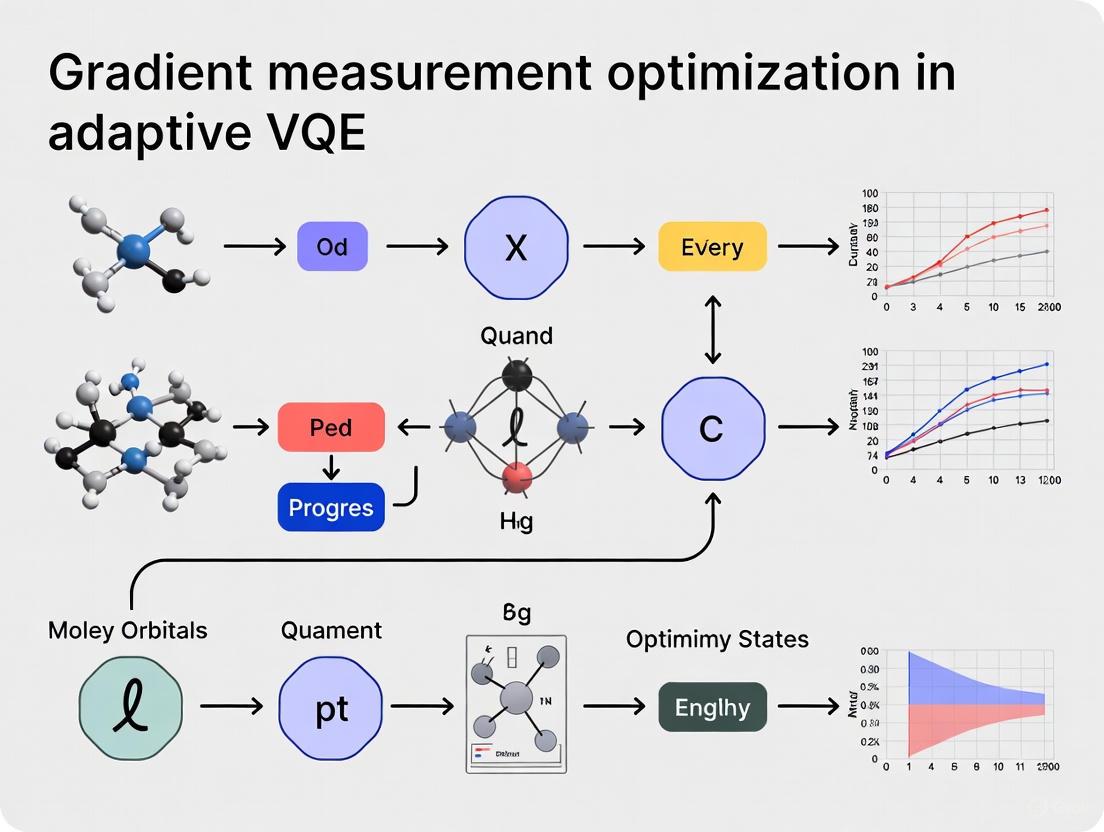

Figure 1: The ADAPT-VQE iterative workflow. The gradient measurement and operator selection steps (in blue) are the primary focus of optimization research.

The Operator Selection Process

The operator selection mechanism is the cornerstone of ADAPT-VQE's efficiency. It ensures that only the most physically significant operators are included in the ansatz.

The Gradient Criterion

At each iteration ( k ), the algorithm screens an operator pool ( \mathbb{U} ) to identify the operator that will yield the steepest descent in energy. The selection criterion is based on the gradient of the energy expectation value with respect to the parameter of a candidate unitary ( \mathscr{U}(\theta) = e^{\theta Am} ) before it is appended (i.e., at ( \theta = 0 )) [4]. The gradient for operator ( Am ) is given by: [ gm = \frac{\partial E^{(k-1)}}{\partial \thetam} \bigg|{\thetam=0} = \langle \Psi^{(k-1)} | \, [H, Am] \, | \Psi^{(k-1)} \rangle ] The operator ( \mathscr{U}^* ) with the largest gradient magnitude is chosen: [ \mathscr{U}^* = \underset{\mathscr{U} \in \mathbb{U}}{\text{argmax}} \, \left| gm \right| ] This gradient corresponds to the energy derivative and directly indicates which operator can lower the energy most rapidly [3] [2].

Operator Pools

The choice of operator pool is critical, as it defines the search space for the adaptive ansatz. Different pools offer trade-offs between expressibility and hardware efficiency.

Table 1: Common Operator Pools in ADAPT-VQE

| Pool Type | Description | Scaling | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fermionic UCCSD [3] | Single & double excitation operators from occupied to virtual HF orbitals. | ( \mathcal{O}(N^4) ) | Physically motivated, respects fermionic symmetries. |

| Generalized Fermionic [3] | Generalized single and pair-double excitations. | Larger than UCCSD | More expressive, can lead to more compact ansätze. |

| Qubit-ADAPT (QEB) [6] | Qubit excitation operators (e.g., Pauli string rotations). | Linear pool size possible | Hardware-efficient, shallower circuits, linear qubit scaling. |

| k-UpCCGSD [3] | Products of paired double and generalized single excitations. | ( \mathcal{O}(N^2) ) | Sparse, shallower circuits than UCCSD for some systems. |

Optimization of Gradient Measurements

The gradient measurement step is a primary source of computational overhead, as it requires evaluating the expectation value of the commutator ( [H, A_m] ) for every operator in the pool. This has spurred research into more efficient strategies.

Challenges in Measurement

The standard gradient evaluation faces two key challenges on NISQ devices:

- Measurement Overhead: The number of measurements (shots) required to estimate gradients for large operator pools can be immense [5].

- Noise Sensitivity: Noisy evaluations of the cost function can cause the algorithm to stagnate well above chemical accuracy, as shown in studies of Hâ‚‚O and LiH molecules [4].

Advanced Optimization Strategies

Recent research has produced several promising approaches to mitigate these issues.

Table 2: Strategies for Gradient Measurement Optimization

| Strategy | Core Principle | Key Advantage | Representative Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shot-Efficient Protocols | Reuse Pauli measurements from VQE optimization in subsequent gradient steps; use variance-based shot allocation [5]. | Significantly reduces the total number of shots required to achieve chemical accuracy. | Shot-Efficient ADAPT-VQE [5] |

| Overlap-Guided Selection | Avoid energy plateaus by growing the ansatz to maximize overlap with an accurate target wavefunction (e.g., from classical computation) [1]. | Produces ultra-compact ansätze, avoids local minima, reduces circuit depth. | Overlap-ADAPT-VQE [1] |

| Gradient-Free Optimization | Replace gradient-based selection with analytic, gradient-free methods for operator selection and parameter optimization [4]. | Improved resilience to statistical sampling noise. | Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE) [4] |

| Quantum-Aware Optimizers | Use closed-form expressions of the energy landscape for specific operator types (e.g., excitations) to find global minima [7]. | Reduces number of energy evaluations, robust to noise. | ExcitationSolve [7] |

Figure 2: Research pathways for optimizing the critical gradient measurement and operator selection process in ADAPT-VQE.

Experimental Protocols and Reagents

This section provides a detailed methodology for implementing a typical ADAPT-VQE simulation, using the Feâ‚„Nâ‚‚ molecule as an example [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Methods

| Category | Item | Function / Description | Example (from search results) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Frameworks | InQuanto [3] | A quantum computational chemistry platform for developing and running algorithms like ADAPT-VQE. | AlgorithmFermionicAdaptVQE |

| OpenFermion [1] | A library for obtaining and representing molecular Hamiltonians and fermionic operators. | OpenFermion-PySCF module | |

| Simulators & Hardware | Qulacs Backend [3] | A high-performance simulator for quantum circuits, used for statevector simulations. | QulacsBackend() |

| NISQ QPU [4] | A physical Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum computer for experimental execution. | 25-qubit error-mitigated QPU | |

| Classical Optimizers | Minimizer (L-BFGS-B) [3] | A classical optimization algorithm for the variational parameter tuning. | MinimizerScipy(method="L-BFGS-B") |

| COBYLA [2] | A gradient-free optimization algorithm for variational parameter tuning. | optimizer = 'COBYLA' |

|

| Operator Pools | UCCSD Operators [3] | A pool of fermionic excitation operators for building the ansatz. | construct_single_ucc_operators construct_double_ucc_operators |

| Qubit-ADAPT Pool [6] | A hardware-efficient pool of qubit operators (e.g., Pauli strings). | Linear-sized, hardware-efficient pool | |

| Carpetimycin C | Carpetimycin C, MF:C14H20N2O6S, MW:344.39 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (-)-Codonopsine | (-)-Codonopsine, CAS:26989-20-8, MF:C14H21NO4, MW:267.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Detailed Protocol: ADAPT-VQE for Feâ‚„Nâ‚‚

Objective: To calculate the electronic ground state energy of the Feâ‚„Nâ‚‚ molecule using the ADAPT-VQE algorithm [3].

Pre-requisites: A classical computation has been performed to define the chemical system, resulting in pickled files for the qubit Hamiltonian, initial state, and orbital space [3].

Key Parameters:

- Tolerance: The

toleranceparameter (e.g.,1e-3) sets the convergence threshold for the gradient norm [3]. This value is system-dependent and often relies on practical experience. - Minimizer: The choice of classical optimizer (e.g., L-BFGS-B) can significantly impact convergence performance [3].

ADAPT-VQE represents a significant advancement over fixed-ansatz VQE by systematically constructing compact, system-tailored quantum circuits. The core of its efficiency lies in the gradient-based operator selection process, which iteratively identifies and appends the most relevant operators from a predefined pool. However, the practical implementation of this process on NISQ devices is currently challenged by the significant measurement overhead and sensitivity to noise associated with gradient evaluations.

Ongoing research focused on gradient measurement optimization—through shot-efficient protocols, overlap-guided strategies, and robust gradient-free optimizers—is crucial for bridging this gap. These developments strengthen the promise of achieving chemically accurate molecular simulations on quantum computers, with profound potential implications for materials science and drug development.

A significant challenge in realizing practical variational quantum eigensolvers (VQEs) on near-term quantum hardware is the polynomially scaling measurement overhead associated with evaluating cost functions and their gradients. This overhead presents a critical bottleneck, particularly for adaptive VQE variants like the ADAPT-VQE algorithm, which employs iterative, greedy ansatz construction [4]. In these methods, each iteration requires estimating gradients for numerous operators in a predefined pool, potentially requiring tens of thousands of extremely noisy measurements on quantum devices [4]. For hardware-efficient operator pools, the gradient-measurement step of the ADAPT-VQE algorithm can require the estimation of O(Nâ¸) observables for N-qubit systems, creating a fundamental scalability barrier [8]. This application note dissects the sources of measurement overhead in gradient-based adaptive VQE protocols, presents structured optimization strategies, and provides detailed methodologies for efficient implementation on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices.

Quantitative Analysis of Measurement Overhead

Scaling Challenges Across Molecular Systems

The number of measurements required for VQE calculations scales significantly with molecular size. The table below illustrates this scaling by comparing the number of Hamiltonian terms for different molecules, which corresponds directly to the number of expectation values needing measurement in a naive approach.

Table 1: Measurement Scaling for Molecular Hamiltonians

| Molecule | Number of Qubits | Hamiltonian Terms | Measurement Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | 4 | 15 | Constant |

| Hâ‚‚O | 14 | 1086 | O(Nâ´) with N spin-orbitals |

| Larger Molecules | >14 | ~100,000+ | O(Nâ´) to O(Nâ¸) |

For the hydrogen molecule (Hâ‚‚), the Hamiltonian contains only 15 terms, making measurement tractable. However, for the water molecule (Hâ‚‚O) with 14 qubits, the Hamiltonian expands to 1,086 terms [9]. For more complex molecules, this number can grow to hundreds of thousands of terms, creating a substantial measurement bottleneck [10].

Gradient Measurement Overhead in Adaptive Algorithms

In adaptive VQE protocols like ADAPT-VQE, the measurement overhead is particularly pronounced due to the need to evaluate gradients across operator pools:

Table 2: Gradient Measurement Complexity in Adaptive VQE

| Algorithmic Step | Measurement Requirement | Theoretical Scaling | Optimized Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operator Selection | Gradient evaluation for each pool operator | O(Nâ¸) for hardware-efficient pools [8] | O(N) with commutativity-based grouping [8] |

| Cost Function Optimization | Expectation value of Hamiltonian | O(Nâ´) with term grouping | Similar with additional noise resilience [4] |

| Global Parameter Optimization | Multi-dimensional parameter optimization | High due to noisy cost function | Simplified via greedy, gradient-free methods [4] |

The Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE) algorithm addresses these challenges by employing analytic, gradient-free optimization, demonstrating improved resilience to statistical sampling noise [4].

Theoretical Framework: Efficiency vs. Expressivity Trade-offs

Simultaneous Measurability of Gradient Components

A fundamental relationship exists between gradient measurement efficiency and quantum neural network (QNN) expressivity. The gradient measurement efficiency (ℱeff) is defined as the mean number of simultaneously measurable components in the gradient, while expressivity (ð’³exp) quantifies the dimension of the Dynamical Lie Algebra (DLA) that characterizes which unitaries the QNN can express [11].

Research has rigorously proven that more expressive QNNs require higher measurement costs per parameter for gradient estimation. This trade-off implies that reducing QNN expressivity to suit a specific task can increase gradient measurement efficiency [11]. Formally, two gradient components ∂jC and ∂kC are simultaneously measurable if their gradient operators [Γj(θ), Γk(θ)] = 0 for all θ [11].

Exact Gradient Framework for General Cost Functions

Recent work has established a universal and exact framework for gradient derivation applicable to all differentiable cost functions in VQAs. This framework provides analytic gradients without restrictive assumptions, extending gradient-based optimization beyond conventional expectation-value settings [12]. The partial derivative of a general cost function C(θ) with respect to parameter θj can be computed exactly as:

∂C(θ)/∂θj = f[ð’°â€ (θ)∂ð’°(θ)/∂θj + ∂ð’°â€ (θ)/∂θjð’°(θ), {Ïk}, {Ok}]

For parameterized unitaries Uj(θj) = exp(-iθjPj/2) with Pauli operators Pj, the exact gradient can be obtained by evaluating the circuit at a Ï€-shifted parameter: ∂ð’°(θ)/∂θj = 1/2 ð’°(θ + Ï€eâ±¼) [12]. This enables direct hardware implementation through quantum subroutines like the Hadamard and Hilbert-Schmidt tests.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Efficient Gradient Measurement in ADAPT-VQE

Figure 1: Workflow for Commutativity-Based Gradient Measurement

The protocol for efficient gradient measurement in ADAPT-VQE involves:

Operator Pool Initialization: Prepare a pool of unitary operators {Uâ‚, Uâ‚‚, ..., Uₘ} from which the adaptive ansatz will be constructed [4].

Gradient Operator Computation: For each operator Uₖ in the pool, compute the gradient operator Γₖ(θ) = ∂ₖ[U†(θ)OU(θ)] at the current parameter value θ [11].

Commutativity Analysis: Identify sets of mutually commuting gradient operators where [Γᵢ(θ), Γⱼ(θ)] = 0 for all θ. This enables simultaneous measurement of multiple gradient components [11] [8].

Simultaneous Measurement: For each commuting set, measure all gradient components using a single quantum measurement configuration, dramatically reducing the total number of required measurements [8].

Operator Selection: Identify the operator with the largest gradient magnitude and append it to the growing ansatz, then optimize all parameters [4].

This approach reduces the measurement overhead of ADAPT-VQE from O(Nâ¸) to only O(N) times the cost of a naive VQE iteration, making practical implementation on real devices more feasible [8].

Hamiltonian Term Grouping Protocol

Figure 2: Measurement Optimization via Hamiltonian Term Grouping

For efficient estimation of the Hamiltonian expectation value:

Hamiltonian Decomposition: Express the electronic Hamiltonian H as a sum of Pauli strings: H = Σᵢ wᵢPᵢ, where Pᵢ are Pauli operators and wᵢ are coefficients [10].

Commuting Group Identification:

Diagonalizing Unitary Construction: For each group G, find a unitary U such that U†PᵢU is diagonal for all Pᵢ in G [10].

Simultaneous Measurement: For each group, apply the diagonalizing unitary U and measure in the computational basis, enabling simultaneous estimation of all terms in the group [10] [9].

Applied to molecular systems, this protocol achieves a 30% to 80% reduction in both the number of measurements and gate depth in measurement circuits compared to state-of-the-art methods [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Measurement Optimization

| Tool/Technique | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Commutativity-Based Grouping | Identifies simultaneously measurable operators to reduce measurement overhead | Algorithms include Sorted Insertion (SI) and Iterative Coefficient Splitting (ICS) [10] |

| Stabilizer-Logical Product Ansatz (SLPA) | QNN structure that optimizes trade-off between expressivity and measurement efficiency | Achieves theoretical upper bound of gradient measurement efficiency for given expressivity [11] |

| Generalized Parameter-Shift Rule | Computes exact gradients for arbitrary cost functions through parameter shifts | Enables gradient evaluation for non-expectation value cost functions [12] |

| Simultaneous Measurement of Commuting Operators | Enables parallel evaluation of multiple observables in a single circuit execution | Reduces required quantum circuit executions by up to 90% for some molecular systems [9] [8] |

| Hardware-Efficient Operator Pools | Provides problem-tailored ansätze with reduced circuit depth | Trade-off between expressivity and measurement requirements must be carefully balanced [4] [11] |

| Forphenicine | Forphenicine | Forphenicine is a potent alkaline phosphatase inhibitor and immunomodulator for research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Bephenium | Bephenium, CAS:7181-73-9, MF:C17H22NO+, MW:256.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Measurement optimization represents a critical path toward practical quantum advantage in chemical simulations using NISQ devices. By leveraging commutativity relationships among operators, researchers can dramatically reduce the measurement overhead associated with both gradient evaluations and energy estimation in adaptive VQE algorithms. The fundamental trade-off between quantum neural network expressivity and gradient measurement efficiency provides guiding principles for designing more efficient quantum algorithms tailored to specific chemical applications. As quantum hardware continues to improve, these measurement optimization strategies will play an increasingly vital role in enabling the simulation of larger molecular systems relevant to drug development and materials design.

Variational Quantum Eigensolvers (VQE), particularly their adaptive variants like ADAPT-VQE, represent a leading methodology for solving electronic structure problems on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. Their hybrid quantum-classical nature offers potential resilience to noise. However, practical implementations face significant bottlenecks from two interrelated challenges: statistical noise from finite measurement sampling (shots) and hardware limitations from current quantum processors' inherent noise. These challenges are particularly acute for the gradient measurements and optimization routines essential to adaptive protocols. This application note details these limitations and summarizes current experimental strategies for mitigating them, providing a framework for researchers navigating this landscape.

Quantitative Performance Analysis

The performance gap between simulated and real-hardware VQE executions can be quantified across several key metrics, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of VQE Algorithms in Different Execution Environments

| Algorithm / Protocol | Execution Environment | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Primary Limiting Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VQE for PDEs (4-qubit) [13] | Noiseless Statevector Simulator | Final-time Infidelity | $\mathcal{O}(10^{-9})$ | Algorithmic precision |

| Quantum Dynamics for PDEs (e.g., Trotterization) [13] | Real Hardware (IBM) | Final-time Infidelity | $\gtrsim 10^{-1}$ | Hardware noise (gate errors, decoherence) |

| ADAPT-VQE (H$_2$O, LiH) [4] | Noiseless Emulator | Energy Convergence | Reaches chemical accuracy | N/A (idealized simulation) |

| ADAPT-VQE (H$_2$O, LiH) [4] | Shot-Based Emulator (10,000 shots) | Energy Convergence | Stagnates above chemical accuracy | Statistical (shot) noise |

| ADAPT-VQE (Benzene) [14] [15] | Real Hardware (IBM) | Energy Estimation Accuracy | Insufficient for reliable chemical insights | Combined hardware and statistical noise |

| GGA-VQE (25-qubit Ising Model) [4] [16] | Real Hardware (25-qubit QPU) | Wavefunction Approximation | Favorable approximation achieved | Hardware noise (requires noiseless emulation for energy evaluation) |

Experimental Protocols for Noisy Environments

Protocol: Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE)

The GGA-VQE protocol is designed to drastically reduce the measurement overhead and statistical noise vulnerability of the standard ADAPT-VQE algorithm [4] [16].

Application Scope: Constructing system-tailored ansätze for ground-state energy calculations on NISQ devices. Experimental Workflow:

- Initialization: Begin with an initial state, typically the Hartree-Fock reference state

|ψ₀⟩, and an empty ansatz circuit. - Operator Pool Definition: Define a pool

Uof parameterized unitary operators (e.g., fermionic excitations). - Greedy Operator Selection & Angle Optimization:

a. For each candidate operator

U_k(θ)in the poolU: i. Energy Curve Fitting: Execute the current circuit appended withU_k(θ)for a minimum of five different values of the parameterθ(e.g.,θ = 0, Ï€/2, Ï€, 3Ï€/2). Measure the energy expectation value for each. ii. Analytical Fitting: Classically, fit the measured energies to the known analytical form of the energy landscape,E(θ) = aâ‚cos(θ) + aâ‚‚cos(2θ) + bâ‚sin(θ) + bâ‚‚sin(2θ) + c[7]. iii. Minimum Identification: Classically compute the valueθ*_kthat globally minimizes the fittedE(θ)curve. b. Operator Selection: From all candidates, select the operatorU_*that yields the lowest minimum energyE(θ*_k). - Circuit Update: Permanently append the selected operator

U_*(θ*)with its pre-optimized parameterθ*to the ansatz circuit. The parameters from previous steps are not re-optimized. - Iteration: Repeat steps 3-4 until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., the energy change between iterations falls below a predefined threshold).

Logical Workflow of the GGA-VQE Protocol:

This protocol optimizes the parameters of a fixed, physically-motivated ansatz (e.g., UCCSD) in a noise-resilient manner [7].

Application Scope: Efficient, global parameter optimization for fixed ansatz VQEs, compatible with excitation operators. Experimental Workflow:

- Initialization: Prepare the parameterized ansatz state

|ψ(θ)⟩ = U(θ)|ψ₀⟩with an initial parameter vectorθ. - Parameter Sweep:

a. For each parameter

θ_jin the ansatz: i. Energy Evaluation: On the quantum computer, measure the energy for at least five different values ofθ_jwhile keeping all other parameters fixed. The number of evaluations can be increased for better noise robustness [7]. ii. Landscape Reconstruction: Classically, use these energy values to reconstruct the full 1D analytical energy landscapef_θ(θ_j)(a second-order Fourier series, as in GGA-VQE). iii. Global Update: Classically, find the global minimum of the reconstructedf_θ(θ_j)and updateθ_jto this optimal value. b. A full sweep is completed once allNparameters have been updated. - Iteration: Perform repeated sweeps until the energy change between sweeps falls below a specified threshold.

Hardware Deployment and Noise Mitigation

Case Study: ADAPT-VQE for Benzene

A benchmark study to compute the ground-state energy of benzene (C₆H₆) on IBM hardware illustrates the current limitations [14] [15].

Experimental Procedure:

- System Preparation: a. Active Space Approximation: Reduce the full molecular Hamiltonian to an effective Hamiltonian focusing on a selected subset of active orbitals (e.g., π-orbitals) to minimize qubit count [15]. b. Qubit Mapping: Transform the fermionic effective Hamiltonian into a qubit Hamiltonian using a mapping (e.g., Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev).

- Algorithmic Optimization: Apply strategies to minimize resource use: a. Ansatz Optimization: Use adaptive methods to build compact, problem-tailored circuits. b. Optimizer Modifications: Employ classical optimizers like COBYLA, potentially with modifications for noisy landscapes [15].

- Hardware Execution & Post-Processing: a. Execute the quantum circuit on the IBM quantum processor. b. Use error mitigation techniques (e.g., read-out error mitigation) to partially correct hardware noise. c. For accurate energy evaluation, the parameterized circuit from the hardware run can be executed on a noiseless emulator in a "hybrid observable measurement" approach [4].

Reported Outcome: Despite all optimizations, the noise levels in current devices prevented the evaluation of the molecular Hamiltonian with sufficient accuracy for reliable quantum chemical insights [14] [15]. The study concluded that orders-of-magnitude improvement in hardware error rates are required for practical applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational "Reagents" for Adaptive VQE Experiments

| Research Reagent | Type | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pool (e.g., Fermionic excitations, Qubit excitations) [4] [7] | Algorithmic Component | Provides a library of unitary operators from which the adaptive algorithm constructs the problem-specific ansatz. |

| Active Space Hamiltonian [15] [17] | Physical Model | Reduces computational complexity by focusing on a correlated subset of molecular orbitals, making the problem tractable for limited qubit counts. |

| Parameter Shift Rule [18] | Algorithmic Protocol | Enables the calculation of exact gradients of expectation values on quantum hardware, essential for gradient-based optimization and operator selection in ADAPT-VQE. |

| Error Mitigation Techniques (e.g., Read-out error mitigation, Ansatz-based error mitigation) [4] [17] | Post-Processing Method | Reduces the impact of specific hardware noise sources on measured expectation values, improving the accuracy of energies and gradients. |

| Shot Noise Simulator (e.g., HPC emulator) [4] | Software Tool | Allows for the simulation of quantum algorithms under realistic statistical noise, enabling algorithm development and benchmarking before hardware deployment. |

| 4-Isopropylcatechol | 4-Isopropylcatechol|CAS 2138-43-4|For Research | High-purity 4-Isopropylcatechol for research on melanogenesis, vitiligo, and antimelanoma immunity. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or diagnostic use. |

| Vasicinol | Vasicinol, MF:C11H12N2O2, MW:204.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization of the Broader Adaptive VQE Challenge Landscape

The core challenges and mitigation strategies in adaptive VQE research are interconnected, as shown in the following system diagram.

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithm for finding ground state energies of molecular systems on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. By combining quantum circuit execution with classical optimization, VQE provides a practical approach to quantum chemistry simulations that avoids the prohibitive circuit depths of fault-tolerant algorithms [19]. The core of VQE involves minimizing the energy expectation value (E(\vec{\theta}) = \langle\psi(\vec{\theta})|\hat{H}|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle) through iterative parameter updates in a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) [20].

Adaptive VQE variants, particularly ADAPT-VQE, have demonstrated significant advantages over fixed ansatz approaches by systematically constructing problem-tailored quantum circuits. However, these methods introduce substantial measurement overhead through their operator selection process, which requires evaluating gradients for numerous candidate operators [21] [4]. Recent advances in gradient measurement optimization have directly addressed this bottleneck, enabling the application of VQE to increasingly complex molecular systems—from simple diatomic molecules to multi-orbital systems with strong correlation.

This application note documents how optimized gradient measurement techniques have expanded the practical applicability of VQE across the molecular complexity spectrum, with specific protocols for implementation and validated performance data from recent studies.

Gradient Measurement Techniques in Adaptive VQE

Fundamental Gradient Estimation Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Gradient Estimation Techniques in VQE

| Technique | Principle | Measurement Cost | Precision | Hardware Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter-Shift Rule (PSR) | Evaluates circuit at shifted parameters | 2 circuit executions per parameter | Exact | Qubit-based systems [22] |

| Photonic PSR | Specialized shift rules for photonic encodings | Linear in photon number | Exact | Photonic quantum processors [22] |

| Finite Differences | Numerical approximation via small parameter perturbations | 2 circuit executions per parameter | Approximate (noise-sensitive) | All platforms (but not recommended) [22] |

| QN-SPSA | Approximates quantum natural gradient with simultaneous perturbation | Constant per iteration (2 circuit executions) | Approximate | NISQ devices [19] |

| ExcitationSolve | Analytic energy landscape reconstruction for excitation operators | 4 circuit executions per parameter | Global optimum along parameter | Chemistry-inspired ansätze [7] |

The Parameter-Shift Rule (PSR) has emerged as the gold standard for exact gradient computation on quantum hardware, overcoming the noise sensitivity of finite-difference methods by evaluating circuits at strategically shifted parameter values rather than infinitesimal perturbations [22]. This approach has recently been extended to photonic quantum computing platforms through specialized photonic PSR, enabling exact gradient calculations on hardware that previously relied on approximate methods [22].

For higher-dimensional optimization problems, the QN-SPSA method provides a resource-efficient approximation of the quantum natural gradient by simultaneously perturbing all parameters and estimating the Fubini-Study metric tensor [19]. Recent hybrid approaches like QN-SPSA+PSR combine the computational efficiency of approximate metric estimation with the precision of exact gradient computation via PSR, demonstrating improved stability and convergence speed while maintaining low resource consumption [19].

For chemistry-specific applications, the ExcitationSolve algorithm enables globally-informed, gradient-free optimization of excitation operators that obey the generator property (Gj^3 = Gj), which includes fermionic and qubit excitation operators common in unitary coupled cluster ansätze [7]. This method reconstructs the analytical energy landscape using only four circuit evaluations per parameter and classically computes the global minimum, significantly reducing quantum resource requirements [7].

Measurement Overhead Reduction Strategies

Table 2: Shot-Efficient Measurement Techniques for ADAPT-VQE

| Strategy | Implementation | Reported Efficiency Gain | Applicable Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pauli Measurement Reuse | Reusing Pauli strings from VQE optimization in subsequent ADAPT iterations | 32.29% reduction in average shot usage [21] | Hâ‚‚ to BeHâ‚‚ (4-14 qubits), Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„ (16 qubits) [21] |

| Variance-Based Shot Allocation | Allocating measurement shots based on term variance | 5.77-51.23% reduction vs. uniform allocation [21] | Hâ‚‚, LiH with approximated Hamiltonians [21] |

| Commutativity-Based Grouping | Grouping commuting terms from Hamiltonian and gradient observables | 38.59% reduction with qubit-wise commutativity [21] | All molecular systems [21] |

Advanced measurement strategies have been developed specifically to address the shot overhead challenges in adaptive VQE. The integration of Pauli measurement reuse with variance-based shot allocation has demonstrated particularly strong results, reducing average shot consumption to approximately 32% of naive measurement schemes [21]. This approach leverages the observation that Pauli strings measured during VQE parameter optimization often overlap with those required for gradient computations in subsequent ADAPT-VQE iterations.

Variance-based shot allocation applies the theoretical optimum budget framework to both Hamiltonian and gradient measurements, dynamically distributing measurement shots according to term variance rather than using uniform allocation [21]. When combined with commutativity-based grouping (e.g., qubit-wise commutativity), this strategy enables efficient simultaneous measurement of compatible observables, further reducing the quantum resource requirements for practical implementations.

Application Progression: From Simple to Complex Molecular Systems

Simple Diatomic Molecules (Hâ‚‚, LiH)

Experimental Protocol: Ground State Energy Calculation for Hâ‚‚ Molecule

Hamiltonian Preparation: Map the electronic structure Hamiltonian of Hâ‚‚ to qubit operators using Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation, resulting in a 4-qubit Hamiltonian [21].

Ansatz Initialization: Begin with Hartree-Fock reference state (|01\rangle) (for minimal basis) and initialize ADAPT-VQE with fermionic excitation operator pool [4].

Gradient Measurement for Operator Selection:

- For each operator ( \taui ) in the pool, compute the gradient ( \frac{dE}{d\thetai} ) using Parameter-Shift Rule:

- Execute quantum circuit at parameters shifted by ( +\pi/4 ) and ( -\pi/4 )

- Calculate gradient as: ( g_i = [E(+\pi/4) - E(-\pi/4)] ) [22]

- Apply shot-efficient strategies: Reuse Pauli measurements from previous VQE optimization; allocate shots based on variance [21]

- For each operator ( \taui ) in the pool, compute the gradient ( \frac{dE}{d\thetai} ) using Parameter-Shift Rule:

Operator Selection and Addition: Identify operator with largest gradient magnitude ( |gi| ) and append to ansatz: ( U(\theta) \rightarrow e^{\thetai \tau_i} U(\theta) ) [4]

Parameter Optimization: Optimize all parameters in the expanded ansatz using ExcitationSolve:

- For each parameter, execute circuit at 4 different angles to reconstruct energy landscape

- Analytically determine global minimum via companion-matrix method [7]

Convergence Check: Repeat until energy change falls below chemical accuracy threshold (1.6 mHa) or gradient norms fall below ( 10^{-3} ) [4]

For simple diatomic molecules like Hâ‚‚, optimized gradient techniques have enabled rapid convergence to chemical accuracy. The ExcitationSolve algorithm has demonstrated particular effectiveness, achieving chemical accuracy for equilibrium geometries in a single parameter sweep [7]. On the Hâ‚‚ molecule (4-qubit system), variance-based shot allocation with Parameter-Shift Rule reduced measurement requirements by 43.21% compared to uniform shot distribution [21].

The LiH molecule presents increased complexity due to stronger electron correlation effects. On this system, shot-efficient ADAPT-VQE with variance-based shot allocation achieved 51.23% reduction in measurement requirements while maintaining chemical accuracy [21]. These results highlight how gradient optimization techniques enable practical computation even on early NISQ devices with limited measurement capabilities.

Multi-Orbital Systems (Hâ‚‚O, BeHâ‚‚, Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„)

Experimental Protocol: Strongly Correlated Systems with Adaptive Ansätze

Active Space Selection: For multi-orbital systems, identify chemically relevant active spaces (e.g., 8 electrons in 8 orbitals for Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„) to reduce qubit requirements [21].

Noise-Adaptive Gradient Measurements:

Iterative Ansatz Construction:

- At each iteration m, compute gradients for all pool operators using shot-reuse strategy

- Select operator with maximum gradient magnitude: ( \mathscr{U}^* = \underset{\mathscr{U} \in \mathbb{U}}{\text{argmax}} \left| \frac{d}{d\theta} \langle \Psi^{(m-1)} | \mathscr{U}(\theta)^\dagger H \mathscr{U}(\theta) | \Psi^{(m-1)} \rangle \right|_{\theta=0} ) [4]

- Exploit term commutativity to simultaneously measure multiple operator gradients [21]

Constrained Optimization: Incorporate physical constraints via penalty terms: ( E{\text{constrained}} = \langle H \rangle + \sumi \mui (\langle \hat{C}i \rangle - C_i)^2 ) to preserve particle number and spin symmetries [20]

For multi-orbital systems like Hâ‚‚O and BeHâ‚‚, measurement optimization becomes increasingly critical. The reused Pauli measurement protocol has been successfully demonstrated on systems ranging from Hâ‚‚ (4 qubits) to BeHâ‚‚ (14 qubits), maintaining approximately 32% shot efficiency compared to naive measurement approaches [21]. On the strongly correlated Hâ‚‚O molecule, gradient-free adaptive approaches have demonstrated improved resilience to statistical sampling noise, overcoming the stagnation issues that plague standard ADAPT-VQE under measurement noise [4].

The extension to larger multi-orbital systems like Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„ (16 qubits with 8 active electrons and 8 active orbitals) represents the current frontier for practical VQE applications. On these systems, the combination of shot reuse strategies and variance-based allocation has enabled convergence to chemically accurate energies while reducing measurement overhead by approximately two-thirds compared to unoptimized approaches [21].

Visualization of Optimized Adaptive VQE Workflows

Figure 1: Optimized Adaptive VQE Workflow with Gradient Measurement Core. The workflow highlights the central role of shot-efficient gradient measurement protocols (blue nodes) in the adaptive ansatz construction process, demonstrating how measurement optimization techniques are integrated throughout the iterative procedure.

Figure 2: Molecular Complexity and Corresponding Gradient Optimization Strategies. The progression from simple to complex molecular systems requires increasingly sophisticated gradient measurement and shot allocation techniques, with corresponding improvements in measurement efficiency.

Table 3: Essential Computational Resources for Gradient-Optimized VQE Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Application in Gradient-Optimized VQE |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Software Frameworks | Qiskit, PennyLane, Cirq, TensorFlow Quantum | Gradient computation via parameter-shift rules; hardware-efficient ansatz design [24] |

| Classical Optimizers | ExcitationSolve, Rotosolve, GGA-VQE | Quantum-aware optimization with minimal circuit evaluations [7] [4] |

| Measurement Reduction Libraries | Custom shot allocation, Pauli grouping algorithms | Variance-based shot allocation; commutativity-based measurement grouping [21] |

| Hardware Platforms | Neutral atom systems (qubit configuration optimization), Photonic processors (photonic PSR) | Problem-inspired ansatz via configurable qubit interactions; photonic-native gradient computation [25] [22] |

| Error Mitigation Tools | Zero-noise extrapolation, probabilistic error cancellation | Enhancing gradient measurement accuracy under NISQ device noise [20] |

Optimized gradient measurement techniques have fundamentally expanded the practical application range of variational quantum algorithms from simple diatomic molecules to complex multi-orbital systems. The integration of shot-efficient measurement strategies with problem-inspired ansätze has demonstrated measurable improvements in convergence behavior and resource requirements across the molecular complexity spectrum.

Future development directions include the refinement of hardware-specific gradient computation protocols, particularly for emerging quantum architectures like neutral atom and photonic platforms. The integration of machine learning techniques for predictive parameter initialization and the development of more sophisticated measurement reuse strategies represent promising avenues for further reducing the quantum resource requirements of practical quantum chemistry simulations on NISQ devices. As these gradient optimization techniques mature, they will continue to push the boundaries of computationally tractable quantum chemistry simulations, potentially enabling quantum advantage for specific molecular systems in the near future.

Advanced Optimization Techniques: From Gradient-Free Methods to Shot Recycling

The quest for molecular ground states, a cornerstone of quantum chemistry and drug development, represents a formidable challenge for classical computers due to exponentially scaling computational resources. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) emerges as a promising hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for near-term quantum devices, designed to approximate these ground-state energies by optimizing a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz). However, the optimization landscape of VQE is notoriously fraught with challenges, including barren plateaus where gradients vanish exponentially with system size, and the measurement overhead required for gradient estimation and parameter optimization [26] [27]. Adaptive approaches like ADAPT-VQE build circuits iteratively to navigate these plateaus but demand a prohibitively large number of quantum measurements for both operator selection and parameter re-optimization at each step, rendering them impractical for current noisy hardware [28] [16]. In response, the Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE) algorithm was developed, introducing a resource-efficient strategy that synergistically combines operator selection and parameter optimization into a single, measurement-frugal step [28] [26].

The GGA-VQE Algorithm: A Greedy Analytical Strategy

GGA-VQE fundamentally rethinks the adaptive VQE workflow. Its core innovation lies in leveraging the known analytic form of the energy landscape for a single parameterized gate. When a single gate (e.g., an excitation operator) is added to a circuit, the energy expectation value ( E(\theta) ) as a function of that gate's parameter ( \theta ) is a simple, predictable trigonometric function—typically a low-order Fourier series such as ( a1 \cos(\theta) + a2 \cos(2\theta) + b1 \sin(\theta) + b2 \sin(2\theta) + c ) [7] [29]. This mathematical insight allows the algorithm to determine the exact minimum for each candidate operator with very few energy evaluations.

The following diagram illustrates the streamlined, greedy workflow of the GGA-VQE algorithm.

The GGA-VQE protocol, as visualized, proceeds as follows:

- Initialization: Begin with a simple reference state, typically the Hartree-Fock state ( |\psi_0 \rangle ), and define a pool of physically motivated excitation operators (e.g., fermionic or qubit excitations).

- Candidate Evaluation: For every operator in the pool, perform steps 3 and 4.

- Landscape Sampling: Execute the quantum circuit, which includes the current ansatz plus the candidate operator at a few specific angles (e.g., 2 to 5 distinct ( \theta ) values). Measure the energy expectation value for each configuration [26] [16].

- Analytic Minimization: Classically, fit the measured energies to the known analytic form of the energy curve for that operator type. Solve analytically for the angle ( \theta^* ) that yields the global minimum on this one-dimensional landscape [7] [28].

- Greedy Selection: After processing all candidates, select the single operator and its corresponding optimal angle ( \theta^* ) that together achieve the lowest energy.

- Circuit Update: Append this new gate to the ansatz with its parameter fixed to ( \theta^* ). This parameter is not re-optimized in subsequent iterations.

- Termination Check: Repeat steps 2-6 until a convergence criterion is met, such as a minimal energy improvement between iterations or the magnitude of the available energy gradients falling below a threshold.

Comparative Analysis: GGA-VQE vs. Other Optimizers

The "greedy" and "gradient-free" nature of GGA-VQE gives it distinct advantages over other common optimizer classes in the NISQ era. The table below summarizes a qualitative comparison.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of optimizer classes for adaptive VQE.

| Optimizer Class | Example Algorithms | Key Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages for NISQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-based | Adam, BFGS [7] | Uses gradient estimates for parameter updates. | Well-established, can be efficient in low dimensions. | High measurement cost per step; vulnerable to noise and barren plateaus [27]. |

| Black-box Gradient-free | COBYLA, SPSA [7] | Treats energy function as a black box. | No explicit gradient calculation. | Requires many function evaluations; slow convergence in high dimensions [7]. |

| Quantum-Aware (Rotosolve-type) | Rotosolve, SMO [7] | Exploits known analytic form of energy for certain gates. | Resource-efficient for gates with ( G^2 = I ). | Incompatible with excitation operators (( G^3=G )) without decomposition [7] [29]. |

| Adaptive Gradient-based | ADAPT-VQE [28] | Selects operators by largest gradient; re-optimizes all parameters. | Bypasses barren plateaus; compact ansätze. | Extremely measurement-intensive; infeasible on real hardware [26] [16]. |

| Greedy Gradient-free | GGA-VQE [28] [26] | Selects operator & optimizes angle jointly via analytic minimization. | Very low measurement cost; noise-resilient; demonstrated on hardware. | Less flexible final circuit due to fixed parameters. |

Quantitative Performance and Resource Requirements

The theoretical advantages of GGA-VQE translate into concrete performance metrics, as evidenced by published benchmarks. The algorithm's efficiency is most apparent in its fixed, low measurement cost per iteration and its robustness in noisy environments.

Table 2: Key performance metrics of GGA-VQE from experimental studies.

| Metric | GGA-VQE Performance | Context & Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Measurements per Iteration | 2-5 circuit evaluations per candidate operator [26] [16]. | Fixed cost, independent of qubit count or pool size; drastically lower than ADAPT-VQE. |

| Noise Resilience | Nearly 2x more accurate for Hâ‚‚O, ~5x for LiH under shot noise compared to ADAPT-VQE [26]. | Maintains accuracy where gradient-based optimizers fail due to noise. |

| Hardware Demonstration | >98% fidelity for a 25-qubit Ising model on a trapped-ion QPU (IonQ Aria) [26] [16]. | First converged computation of an adaptive VQE method on a 25-qubit quantum computer. |

| Convergence Speed | Reaches chemical accuracy for small molecules in fewer iterations than ADAPT-VQE [28]. | Builds shorter, more efficient circuits by locking in optimal parameters early. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing GGA-VQE for Molecular Systems

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for running a GGA-VQE computation to find the ground state energy of a molecule, reflecting the methodologies used in the cited studies.

Pre-Computation: Classical Setup

- Molecular Hamiltonian: Classically compute the second-quantized electronic Hamiltonian ( H ) of the target molecule in a chosen basis set (e.g., STO-3G). Freeze core orbitals and specify an active space to reduce qubit count if necessary.

- Qubit Mapping: Map the fermionic Hamiltonian to a qubit operator using a transformation such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev.

- Operator Pool Generation: Define the pool of anti-Hermitian generators ( {G_j} ) for the variational ansatz. Common choices are:

- Initial State Preparation: Prepare the quantum circuit for the Hartree-Fock reference state ( |\psi_0\rangle ), which is a single determinant state easily preparable on a quantum computer.

Quantum-Classical Loop

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential components for a GGA-VQE experiment.

| Component | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Processing Unit (QPU) | Executes parameterized quantum circuits and returns measurement statistics. | 25-qubit trapped-ion system (IonQ Aria) used in proof-of-principle [16]. |

| Classical Optimizer | Executes the GGA-VQE logic: curve fitting, minimization, and operator selection. | A standard laptop or HPC node, running a classical script. |

| Operator Pool | The dictionary of quantum gates (excitations) used to build the ansatz. | UCCSD pool, QCCSD pool, or other physically-motivated sets [7]. |

| Energy Estimation Method | The technique for measuring the expectation value ( \langle H \rangle ) from qubit measurements. | Direct measurement with Hamiltonian term grouping; or Quantum Phase Estimation for fault-tolerant future. |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Post-processing methods to reduce the impact of hardware noise on results. | Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) or Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC). |

The following protocol details the iterative loop:

- Iteration Loop: For iteration ( k ) (starting from ( k=1 )):

- Candidate Operator Loop: For each candidate operator ( Gj ) in the pool: a. Parameter Shift: For a set of 4-5 different angles ( {\theta{j,1}, ..., \theta{j,5}} ), construct and run the circuit ( U(\thetaj) = e^{-i\thetaj Gj}...e^{-i\theta{j,1} G1} |\psi0\rangle ). The current ansatz includes all previously selected and fixed operators. b. Energy Measurement: For each angle configuration, measure the expectation value of the Hamiltonian ( H ) to obtain ( E(\theta{j,m}) ). On real hardware, this involves many "shots" (repetitions) per configuration to achieve statistical precision.

- Classical Curve Fitting: Use the measured energy points to solve for the coefficients ( a1, a2, b1, b2, c ) in the energy function ( E(\thetaj) = a1 \cos(\thetaj) + a2 \cos(2\thetaj) + b1 \sin(\thetaj) + b2 \sin(2\theta_j) + c ) [7]. This can be done via a least-squares fit or solving a linear system.

- Analytic Minimization: Using the fitted coefficients, find the global minimum ( \thetaj^* ) of the analytic function ( E(\thetaj) ). This can be achieved classically by finding the roots of its derivative or using a companion-matrix method [7]. Record the minimal energy value ( E_j^{min} ).

- Greedy Selection: After processing all candidates, identify the operator ( G{best} ) and its angle ( \theta{best}^* ) corresponding to the smallest ( E_j^{min} ).

- Ansatz Update: Permanently append the gate ( e^{-i\theta{best}^* G{best}} ) to the growing ansatz circuit.

- Check Convergence: If the energy reduction ( |E{k-1} - Ek| ) is below a predefined threshold (e.g., ( 10^{-6} ) Ha) or a maximum number of iterations is reached, exit the loop. Otherwise, set ( k = k+1 ) and return to step 2.

Post-Computation and Validation

- Final Energy Evaluation: Once converged, the final energy can be re-evaluated with a larger number of shots for higher precision or using a noiseless classical simulator to understand the impact of hardware noise.

- Wavefunction Analysis: The final parameterized circuit represents the approximated ground state wavefunction. This can be analyzed to compute other molecular properties beyond energy, such as dipole moments.

GGA-VQE represents a significant pragmatic advance in the field of variational quantum algorithms. By adopting a greedy, gradient-free strategy that exploits analytic insights, it directly addresses the most pressing constraints of the NISQ era: limited measurement budgets and hardware noise. Its successful demonstration on a 25-qubit quantum computer marks a milestone, proving that adaptive variational methods can be translated from theoretical simulators to actual quantum hardware for non-trivial problems [26] [16].

While the fixed-parameter strategy might yield slightly less compact circuits than ideally re-optimized ADAPT-VQE, this is a minor trade-off for the immense gains in feasibility and noise resilience. As quantum hardware continues to mature, the principles underpinning GGA-VQE—efficiency, robustness, and hardware-awareness—will remain critical. This algorithm provides a practical pathway for researchers in quantum chemistry and drug development to begin extracting tangible value from quantum computers today, charting a credible course toward future quantum advantage in computational chemistry.

The pursuit of calculating molecular ground states using the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is a cornerstone of quantum computational chemistry [7]. A significant challenge in this field is the optimization of the parameterized quantum circuit, or ansatz, especially when using physically-motivated ansätze that conserve crucial symmetries like particle number or spin [7] [30]. These ansätze, often composed of fermionic or qubit excitation operators as seen in the Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCCSD) ansatz, stand in contrast to problem-agnostic, hardware-efficient ansätze that may produce physically implausible states [7].

The optimization landscape of VQE is a high-dimensional, non-convex trigonometric function riddled with local minima, making it challenging for both gradient-based (e.g., Adam, BFGS) and gradient-free black-box (e.g., COBYLA, SPSA) optimizers [7]. While quantum-aware optimizers like Rotosolve have been introduced to leverage the analytical structure of the energy landscape, their application has been largely limited to quantum gates with generators ( G ) that are self-inverse ((G^2 = I)), such as Pauli rotation gates [7] [31]. This limitation has left a gap in efficiently optimizing the more general excitation operators prevalent in quantum chemistry, whose generators satisfy the condition (G^3 = G) and typically (G^2 \neq I) [7] [31].

This application note details ExcitationSolve, a novel quantum-aware optimizer that bridges this gap. ExcitationSolve is a fast, globally-informed, gradient-free, and hyperparameter-free optimizer specifically designed for ansätze containing excitation operators [7] [31]. By extending the principles of Rotosolve to a broader class of unitaries, it enables more efficient and robust optimization of molecular ground states, which is critical for applications such as computational drug development.

Core Innovation and Theoretical Foundation

ExcitationSolve directly addresses the limitation of previous quantum-aware optimizers by exploiting the specific mathematical form of excitation operators. The core innovation lies in the generalization of the analytical form of the energy landscape for a single parameter.

For a variational ansatz (U(\boldsymbol{\theta})) composed of parameterized unitaries (U(\thetaj) = \exp(-i\thetaj Gj)), the energy expectation value (f(\boldsymbol{\theta})) when varying only a single parameter (\thetaj) is a second-order Fourier series [7] [31]: [ f{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\thetaj) = a1 \cos(\thetaj) + a2 \cos(2\thetaj) + b1 \sin(\thetaj) + b2 \sin(2\thetaj) + c ] This formulation applies to generators (Gj) that fulfill (Gj^3 = Gj), a property exhibited by fermionic excitations, qubit excitations (e.g., in QCCSD), and Givens rotations [7]. The coefficients (a1, a2, b1, b2, c) are independent of (\thetaj) but depend on the other fixed parameters in (\boldsymbol{\theta}).

The ExcitationSolve algorithm, summarized in the workflow below, operates as follows [7] [31]:

- It iteratively sweeps through all (N) parameters in the ansatz.

- For each parameter (\theta_j), it obtains energy evaluations at a minimum of five distinct parameter values.

- These energy values are used to reconstruct the full analytical form of the 1D energy landscape by solving for the five Fourier coefficients.

- The global minimum of this reconstructed landscape is found classically using a direct numerical method like the companion-matrix method.

- The parameter (\theta_j) is updated to this optimal value before proceeding to the next parameter.

This process is repeated until convergence, defined by a threshold on the energy reduction. A key resource advantage is that after the initial minimum is found, only four new energy evaluations are needed per parameter to reconstruct the next landscape, as the previous minimum can be reused [7].

Figure 1. ExcitationSolve Optimization Workflow. The diagram illustrates the iterative parameter sweep process, showing the cycle of energy evaluation, landscape reconstruction, and global parameter update for both fixed and adaptive ansätze [7] [31].

Application Protocols

Protocol A: Optimization of Fixed Ansätze (e.g., UCCSD)

This protocol is designed for the optimization of fixed-structure ansätze, such as UCCSD, where the sequence and type of excitation operators are predetermined [7].

- Primary Objective: Efficiently find the parameter set (\boldsymbol{\theta}^*) that minimizes the energy of a fixed ansatz circuit.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Ansatz Preparation: Prepare the parameterized quantum circuit (U(\boldsymbol{\theta})) on the quantum processor. The initial state is typically the Hartree-Fock reference state (\lvert \psi0 \rangle).

- Parameter Initialization: Initialize all parameters (\boldsymbol{\theta}) to zero or a small random value.

- ExcitationSolve Loop: For each iteration until convergence: a. Parameter Selection: Sequentially iterate through all (N) parameters. The order can be random or fixed. b. Landscape Reconstruction: For the current parameter (\thetaj), execute the quantum circuit to measure the energy at at least five shifted values of (\thetaj) (e.g., (\thetaj, \thetaj+\pi/2, \thetaj-\pi/2, \thetaj+\pi/4, \thetaj-\pi/4)). c. Global Minimization: On the classical computer, use the energy values to solve for the coefficients in Eq. (3) and compute the global minimum (\thetaj^) via the companion-matrix method. d. Parameter Update: Set (\thetaj = \theta_j^).

- Convergence Check: After a full sweep through all parameters, check if the energy change since the last sweep is below a predefined threshold (e.g., (10^{-6}) Ha). If not, begin a new sweep.

- Key Advantages: The method is hyperparameter-free (no learning rate) and guaranteed to find the global optimum for each parameter per sweep, leading to faster convergence and reduced quantum resource requirements compared to black-box optimizers [7] [31].

Protocol B: Integration with Adaptive Ansätze (e.g., ADAPT-VQE)

This protocol integrates ExcitationSolve with adaptive ansatz construction methods like ADAPT-VQE, which iteratively grow the ansatz by selecting the most energetically favorable operators from a pool [7] [30].

- Primary Objective: Construct a compact, problem-tailored ansatz and optimize its parameters with minimal quantum resource overhead.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Initialization: Start with a simple initial state (e.g., Hartree-Fock) and define a pool of excitation operators (e.g., all fermionic singles and doubles).

- ADAPT Loop: For each iteration (m) until energy convergence: a. Operator Selection and Optimization: For every operator (Uk(\thetak)) in the pool: i. Analytically reconstruct the 1D energy landscape (f(\thetak)) using the same five-measurement strategy from Protocol A. ii. Classically compute the energy minimum (Ek^) and the corresponding angle (\thetak^). b. Greedy Selection: Identify the operator (U{k^*}) that yields the largest energy reduction, i.e., (k^* = \arg\mink Ek^*). c. Ansatz Growth: Append the selected operator (U{k^}(\theta{k^})) with its optimal parameter (\theta_{k^*}) to the current ansatz. This parameter is now "frozen" for the current ADAPT cycle. d. Optional Fine-Tuning: After adding one or several new operators, perform a full ExcitationSolve parameter sweep (as in Protocol A) over all parameters in the grown ansatz to refactor and fine-tune them.

- Key Advantages: This greedy, gradient-free approach (sometimes called GGA-VQE) avoids the high measurement overhead of measuring gradients for operator selection in standard ADAPT-VQE and circumvents the challenging optimization of a high-dimensional, noisy cost function [30]. It results in shallower circuits and demonstrates improved robustness to statistical shot noise and hardware errors [7] [30].

Experimental Validation and Benchmarking

ExcitationSolve has been rigorously tested on molecular ground state energy benchmarks. The following table summarizes key performance metrics compared to other state-of-the-art optimizers.

Table 1. Performance Benchmarking of ExcitationSolve on Molecular Systems

| Metric / Optimizer | ExcitationSolve | Rotosolve | Gradient-Based (e.g., Adam, BFGS) | Gradient-Free Black-Box (e.g., COBYLA, SPSA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convergence Speed | Faster convergence; chemical accuracy in a single sweep for some equilibrium geometries [7] [31]. | Slower for complex ansätze due to generator mismatch [7]. | Struggles with complex, multi-minima landscapes [7]. | Slow convergence due to high number of function evaluations [7]. |

| Quantum Resource Use | Determines global optimum per parameter with 4(+1) energy evaluations [7]. | Overestimates resources for decomposed excitations [7]. | Requires O(N) evaluations for gradient via parameter-shift [7]. | Very high, requires thousands of energy evaluations [7]. |

| Noise Robustness | Robust to real hardware noise; overdetermined equation solving improves noise resilience [7] [31]. | Performance degrades with noise [7]. | Highly sensitive to noise in gradient estimates [7]. | Moderately robust, but slow convergence amplifies noise effect [7]. |

| Ansatz Compactness (Adaptive) | Yields shallower adaptive ansätze [7]. | Not directly applicable to adaptive ansätze. | Standard ADAPT-VQE often produces deeper circuits [30]. | Standard ADAPT-VQE often produces deeper circuits [30]. |

| Hyperparameter Tuning | Hyperparameter-free [7] [31]. | Hyperparameter-free [7]. | Requires careful tuning of learning rate [7]. | May require tuning of trust-region or other parameters [7]. |

The experimental validation demonstrates that ExcitationSolve outperforms other optimizers by uniting physical insight with efficient optimization. Its ability to achieve chemical accuracy for equilibrium geometries in a single parameter sweep and its robustness to noise make it a particularly compelling choice for NISQ-era quantum chemistry simulations [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2. Essential Components for ExcitationSolve Experiments

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Quantum Processor/Simulator | Executes the parameterized quantum circuit (U(\boldsymbol{\theta})) to prepare the state (\lvert \psi(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \rangle) and measure expectation values of the Hamiltonian. |

| Classical Optimizer Unit | Hosts the ExcitationSolve algorithm; reconstructs 1D energy landscapes from quantum data and computes global minima using methods like the companion-matrix method [7]. |

| Hamiltonian Component | The target Hermitian operator (e.g., molecular electronic Hamiltonian in qubit form). Its expectation value (\langle H \rangle) is the cost function to be minimized. |

| Operator Pool | A pre-defined set of unitary generators (e.g., fermionic singles/doubles) used for adaptive ansatz growth in protocols like ADAPT-VQE [30]. |

| Initial Reference State | The initial quantum state for the VQE algorithm, typically the Hartree-Fock state (\lvert \psi_0 \rangle) for quantum chemistry problems [7]. |

| Sakyomicin D | Sakyomicin D|Quinone Antibiotic|RUO |

| 5-Ethyl-5-(2-methylbutyl)barbituric acid | 5-Ethyl-5-(2-methylbutyl)barbituric acid, CAS:36082-56-1, MF:C11H18N2O3, MW:226.27 g/mol |

Integration in the Research Ecosystem

The development of ExcitationSolve exists within a broader research landscape focused on mitigating the challenges of VQE. The following diagram illustrates its relationship with other key strategies, such as measurement reduction and advanced gradient-based methods.

Figure 2. ExcitationSolve in the VQE Research Ecosystem. The diagram positions ExcitationSolve as one of several complementary strategies aimed at the overarching goal of optimizing gradient measurement and resource use in adaptive VQE. It can be synergistically combined with measurement reuse techniques [5] [32] and advanced natural gradient methods [33] [34].

ExcitationSolve offers a distinct approach compared to other strategies. For instance, while shot-efficient ADAPT-VQE techniques focus on reusing Pauli measurement outcomes or using informationally complete POVMs to reduce the quantum overhead of operator selection [5] [32], ExcitationSolve circumvents the need for explicit gradient measurements entirely through its gradient-free, landscape-reconstruction paradigm [7] [30]. Similarly, advanced natural gradient methods like Momentum Quantum Natural Gradient (QNG) or Modified Conjugate QNG incorporate momentum or conjugate direction concepts to escape local minima and accelerate convergence in curved parameter spaces [33] [34]. ExcitationSolve provides an alternative pathway to robustness and efficiency without requiring the computationally expensive estimation of the quantum Fisher information matrix.

In the pursuit of quantum advantage for molecular simulation, the Adaptive Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) has emerged as a promising algorithm for the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era. By iteratively constructing an ansatz, it reduces circuit depth and mitigates trainability issues like barren plateaus compared to traditional VQE approaches [5] [21]. However, a significant bottleneck hindering its practical application, especially for drug development research, is the enormous measurement (shot) overhead required for both parameter optimization and operator selection in each iteration [21].

This application note details a strategic approach to overcoming this bottleneck by reusing Pauli measurement outcomes obtained during the VQE parameter optimization phase in the subsequent operator selection step. This methodology, positioned within a broader research thesis on gradient measurement optimization, directly addresses the critical need for shot-efficient quantum algorithms. By drastically reducing the quantum resource requirements, this protocol enables researchers and scientists to scale quantum computations to more complex molecular systems, such as those encountered in ligand-protein binding and toxicity prediction studies [35] [36].

Theoretical Background and Motivation

The ADAPT-VQE Workflow and Its Measurement Overhead

The ADAPT-VQE algorithm starts with a simple reference state (e.g., the Hartree-Fock state) and iteratively grows a parameterized ansatz circuit. Each iteration consists of two critical and measurement-intensive stages [21]:

- Operator Selection: Identifying the most promising operator from a predefined pool to add to the ansatz. This is typically done by evaluating gradients or other importance metrics for all pool operators.

- Parameter Optimization: Optimizing all parameters in the current ansatz to minimize the energy expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian.

The measurement overhead arises because both stages require estimating expectation values of various observables. The Hamiltonian itself is a sum of Pauli strings, ( H = \sumi wi Pi ), and the operator selection often involves evaluating commutators ( [H, Ai] ) for each pool operator ( A_i ), which themselves are sums of Pauli strings [21]. On quantum hardware, each distinct Pauli string measurement requires repeated circuit executions (shots) to build statistics, leading to a massive cumulative shot cost that scales with system size.

The Opportunity for Measurement Reuse

The core insight for measurement reuse stems from the observation that the Pauli strings required to evaluate the energy during the VQE parameter optimization stage exhibit significant overlap with the Pauli strings needed to compute the gradients for the operator pool in the next ADAPT iteration [5] [21]. Instead of discarding this measurement data, the proposed protocol systematically identifies and reuses these outcomes, thereby avoiding redundant measurements and realizing significant savings in quantum resources.

Protocol: Shot-Efficient ADAPT-VQE via Pauli Measurement Reuse

What follows is a detailed, step-by-step protocol for implementing the Pauli measurement reuse strategy within an ADAPT-VQE simulation.

Prerequisites and Initial Setup

- Molecular System: Define the molecule (e.g., geometry, basis set).

- Qubit Hamiltonian: Generate the electronic Hamiltonian in the second quantized form and map it to a qubit Hamiltonian using a transformation like Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev, resulting in ( H = \sumi wi P_i ) [10].

- Operator Pool: Select a set of operators ( {A_\alpha} ) (e.g., unitary coupled cluster singlet and double excitations) from which the ansatz will be adaptively built.

- Gradient Observable Construction: For each operator ( A\alpha ) in the pool, precompute the gradient observable ( G\alpha = i [H, A\alpha] ). This commutator will also be a sum of Pauli strings, ( G\alpha = \sumj v{\alpha j} Q_{\alpha j} ).

Step-by-Step Experimental Procedure

Step 1: Initialization Initialize the ansatz circuit ( V(\vec{\theta}) ) to a simple state, such as ( |\psi_0\rangle = V(\vec{\theta})|0\rangle ), which could be the Hartree-Fock state. Set the iteration counter ( k = 1 ).

Step 2: VQE Parameter Optimization Phase For the current ansatz ( Vk(\vec{\theta}) ) at iteration ( k ): 1. Prepare and Measure: For the current parameter set ( \vec{\theta}^* ), prepare the state ( |\psi(\vec{\theta}^*)\rangle = Vk(\vec{\theta}^)|0\rangle ) on the quantum processor. 2. Group Pauli Strings: Group the Hamiltonian Pauli strings ( {P_i} ) into mutually commuting sets (e.g., using Qubit-Wise Commutativity) to minimize the number of distinct measurement circuits [10] [21]. 3. Allocate Shots: Use a shot allocation strategy (e.g., uniform or variance-based [21]) across the groups. 4. Execute Measurements: Run the quantum circuits for each group and collect the measurement outcomes (bitstrings). 5. Calculate Energy: Classically compute the energy expectation value ( E(\vec{\theta}) = \sum_i w_i \langle \psi(\vec{\theta}) | P_i | \psi(\vec{\theta}) \rangle ) from the measurement data. 6. Optimize: Using a classical optimizer, update the parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) to minimize ( E ). Repeat steps 2.1-2.5 until convergence. Upon convergence, store *all raw measurement outcomes (bitstrings) for the final parameter set ( \vec{\theta}^*_k ) in a database, indexed by the measured Pauli group.

Step 3: Operator Selection Phase with Measurement Reuse This step identifies the next operator to add to the ansatz. 1. Identify Overlapping Paulis: For each gradient observable ( G\alpha = \sumj v{\alpha j} Q{\alpha j} ), identify all Pauli strings ( Q{\alpha j} ) that are also present in the Hamiltonian ( H ). These are the "reusable" measurements. 2. Compute Reused Expectation Values: For the overlapping Pauli strings, retrieve the pre-computed expectation values ( \langle Q{\alpha j} \rangle ) directly from the stored VQE measurement data from Step 2.6. 3. Measure New Pauli Strings: For any Pauli string in ( G\alpha ) that was not measured during the VQE phase, perform new quantum measurements on the state ( |\psi(\vec{\theta}^*k)\rangle ). Group these new Pauli strings commutatively to minimize overhead. 4. Calculate Gradient Components: For each pool operator ( A\alpha ), compute the gradient component: ( g\alpha = \langle \psi(\vec{\theta}^_k) | G_\alpha | \psi(\vec{\theta}^k) \rangle = \sumj v{\alpha j} \langle Q{\alpha j} \rangle ), where the values of ( \langle Q{\alpha j} \rangle ) are a mix of reused (Step 3.2) and newly measured (Step 3.3) values. 5. Select Operator: Choose the operator ( A{k} ) with the largest magnitude gradient, ( A{k} = \arg\max{A\alpha} |g\alpha| ).

Step 4: Ansatz Expansion and Iteration Append the selected operator ( A{k} ) (as a parameterized gate, e.g., ( e^{-i\theta{k+1} A_k} )) to the ansatz circuit, initializing its parameter to zero. Set ( k = k + 1 ) and return to Step 2. The algorithm terminates when the norm of the gradient vector falls below a predefined threshold, indicating convergence to the ground state.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and data reuse pathway of the protocol.

Results and Performance Analysis

The efficacy of the Pauli measurement reuse protocol is quantified through numerical simulations on molecular systems. The tables below summarize key performance metrics.

Table 1: Shot Reduction from Pauli Measurement Reuse and Grouping [21]

| Molecular System | Qubit Count | Naive Measurement (Shots) | Grouping Only (Shots) | Grouping + Reuse (Shots) | Reduction vs. Naive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | 4 | Baseline | 38.59% | 32.29% | ~67.71% |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | Baseline | 38.59% | 32.29% | ~67.71% |

| Nâ‚‚Hâ‚„ (8eâ», 8 orb) | 16 | Baseline | 38.59% | 32.29% | ~67.71% |

Note: The reported percentages are average shot usage relative to the naive baseline. A value of 32.29% indicates the method uses less than one-third of the shots required by the naive approach, equating to a reduction of approximately 67.71%.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Shot Reduction Techniques in ADAPT-VQE [21]

| Method Category | Specific Technique | Key Principle | Reported Shot Reduction | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Reuse | Reused Pauli Measurements | Leverages overlap in Pauli strings between VQE and gradient steps. | ~67.71% (vs. Naive) | Directly avoids redundant measurements. |

| Shot Allocation | Variance-Based Shot Allocation (VPSR) | Allocates more shots to noisier observables. | 43.21% (Hâ‚‚), 51.23% (LiH) vs. Uniform | Optimizes shot budget for target precision. |

| Algorithmic Modification | Greedy Gradient-Free ADAPT (GGA-VQE) [26] | One-step operator/parameter selection; no re-optimization. | Fixed 2-5 measurements per iteration. | Extreme noise resilience; demonstrated on 25-qubit hardware. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing the shot-efficient ADAPT-VQE protocol requires a combination of software and theoretical components.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Type | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qubit Hamiltonian | Input Data | The target molecular system encoded as a linear combination of Pauli strings. | Generated via frameworks like OpenFermion [10]. |

| Operator Pool | Algorithmic Component | A set of operators (e.g., fermionic excitations) used to build the ansatz adaptively. | UCCSD-type pools are common starting points [21]. |

| Commutativity Grouping | Software Module | Groups Pauli strings into mutually commuting sets to minimize measurement circuits. | Qubit-Wise Commutativity (QWC) or Fully Commuting (FC) [10] [21]. |

| Variance-Based Shot Allocator | Software Module | Optimally distributes a finite shot budget among observable groups based on their variance. | Can be applied to both Hamiltonian and gradient measurements [21]. |

| Classical Optimizer | Software Module | Updates circuit parameters to minimize the energy expectation value. | L-BFGS-B, SPSA, or gradient-based methods [21]. |