Optimizing Quantum Resources for Molecular Calculations: Strategies for Near-Term Applications in Drug Discovery

This article explores the cutting-edge methodologies and algorithmic advances that are making quantum simulations of molecules a tangible reality for researchers and drug development professionals.

Optimizing Quantum Resources for Molecular Calculations: Strategies for Near-Term Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the cutting-edge methodologies and algorithmic advances that are making quantum simulations of molecules a tangible reality for researchers and drug development professionals. With a focus on resource efficiency, we examine foundational concepts like qubit reduction and error mitigation, detail practical hybrid quantum-classical frameworks for geometry optimization and binding affinity calculations, and provide troubleshooting strategies for near-term hardware limitations. Through comparative analysis of case studies from catalyst design to pharmaceutical development, we validate the performance of these optimized approaches against classical methods, charting a course for their imminent impact on biomedical research.

The Quantum Resource Challenge: Why Efficient Molecular Simulation is Critical for Near-Term Devices

FAQs: Core Quantum Resource Concepts

What defines the fundamental resource bottleneck in a quantum computer? The fundamental bottleneck is the interplay between three resources: the number of qubits (scale), the number of sequential operations they can perform (circuit depth), and the duration for which they maintain their quantum state (coherence time). Useful computation requires that all gates are executed within the coherence limits of the qubits; if the computation is too deep, decoherence occurs, and the result is corrupted [1] [2].

Why is gate fidelity critical even if I have enough qubits and long coherence? Gate fidelity determines the accuracy of each operation. Errors compound as more gates are executed [3]. With a 2% gate error rate, a circuit with 7 sequential gates may see its output become nearly useless. High-fidelity gates are therefore a prerequisite for running deep, complex algorithms reliably [3].

How do these bottlenecks impact research in molecular calculations? Algorithms for molecular simulations, such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) used for finding molecular resonances, require a certain circuit depth to represent the problem accurately. If the combined gate time exceeds the qubit coherence time, or if gate errors are too high, the calculated energies and wavefunctions will be inaccurate, derailing the research [4].

What is the difference between quantum error mitigation and quantum error correction?

- Quantum Error Mitigation (QEM): A set of techniques used on today's noisy hardware to infer less noisy results, often by running many slightly different circuits and post-processing the data. It is a temporary solution for the NISQ era [5].

- Quantum Error Correction (QEC): A more fundamental solution that uses multiple physical qubits to encode a single, more robust "logical qubit." This actively detects and corrects errors in real-time but requires a significant overhead of extra qubits and fast classical processing [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Rapid Decoherence Corrupts Results

Problem: Your quantum circuit produces random or inconsistent results, especially as the circuit complexity increases. This is often due to the computation time exceeding the qubits' coherence time [2].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Check Coherence Specifications: Consult your hardware provider's documentation for the published coherence times (T1, T2) for the specific qubit type you are using [3] [2].

- Profile Circuit Depth: Calculate the total depth of your circuit, accounting for parallelization. Compare the estimated execution time against the known coherence times.

- Simplify the Circuit: Use circuit compilation techniques to reduce the overall gate count and depth.

Resolution Strategies:

- Algorithm Selection: Choose hybrid quantum-classical algorithms (like VQE) that break down the problem into smaller, shallower circuits executed over multiple iterations [4].

- Error Mitigation: Employ techniques like zero-noise extrapolation (ZNE) or probabilistic error cancellation to get closer to a noiseless result without changing the hardware [5].

- Hardware Choice: For algorithms requiring longer execution, consider hardware platforms with inherently longer coherence times, such as trapped ions [3] [2].

Issue: Excessive Gate Errors Limit Algorithmic Accuracy

Problem: Even with a shallow circuit, the final results have a high and unacceptable error margin, making it impossible to distinguish the true signal from noise.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Benchmark Gate Fidelity: Run standard benchmarking circuits (e.g., randomized benchmarking) to verify the single- and two-qubit gate fidelities of your hardware match the provider's specifications [3].

- Audit CNOT Count: Identify the number of two-qubit gates (like CNOT) in your circuit, as these typically have error rates an order of magnitude higher than single-qubit gates [1].

Resolution Strategies:

- CNOT Optimization: Actively work to minimize the number of two-qubit gates in your circuit during the compilation and transpilation stage.

- Leverage High-Fidelity Qubits: If your hardware allows, map the most critical parts of your circuit to the qubits with the best measured gate fidelities.

- Readout Error Mitigation: Apply readout error mitigation techniques to correct for errors that occur when measuring the qubits [4].

Issue: Insufficient Qubit Count for Target Molecule

Problem: The quantum system does not have enough qubits to represent the molecular system you intend to simulate, preventing you from running the experiment at all.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Calculate Qubit Requirement: Determine the number of qubits required to represent your molecular system. This is often determined by the size of the basis set used in the chemistry simulation [4].

- Check for Logical Qubits: Remember that if you are using Quantum Error Correction (QEC), the number of physical qubits required to create one logical qubit can be large (e.g., 100s or 1000s) [5].

Resolution Strategies:

- Active Space Reduction: In collaboration with a quantum chemist, reduce the active space of your calculation to focus on the most relevant molecular orbitals, thereby reducing the qubit count needed.

- Circuit Cutting: For very large circuits, investigate "circuit cutting" techniques that trade circuit depth for width, breaking one large circuit into multiple smaller, executable ones [1].

- Algorithmic Innovation: Utilize algorithms like qDRIVE, which break a large problem into a network of smaller, interconnected VQE tasks that can be run asynchronously and in parallel across multiple quantum processing units [4].

Quantitative Data for Resource Planning

The following tables consolidate key metrics to help researchers plan experiments and select appropriate hardware.

Table 1: Qubit Technology Comparison

| Qubit Type | Typical Coherence Time | Typical Gate Fidelity | Key Advantage | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superconducting [2] [6] | 20 - 100 microseconds | ~99.9% [5] | Fast gate operations | Requires ultra-low temperatures (~10 mK) |

| Trapped Ion [3] [2] [6] | 1 - 10 milliseconds | High (exact figure not stated) | Long coherence times, high connectivity | Slower gate speeds |

| Photonic [2] | Seconds to minutes | Information Missing | Very long coherence times | Challenging to manipulate and store |

Table 2: Error Correction Resource Requirements

| Metric | Target for Useful Computation | Current NISQ Era Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Qubit Error Rate | Below ~1% (QEC threshold) [5] | ~1 error in every 100-1000 operations (~99.9% fidelity) [5] |

| Logical Error Rate | 1 in 1 million (MegaQuOp) to 1 in 1 trillion (TeraQuOp) [5] | Not yet demonstrated |

| Classical Decoder Data Rate | Up to 100 TB per second [5] | Not yet achievable |

Experimental Protocol: qDRIVE for Molecular Resonances

The qDRIVE (Quantum Distributed Variational Eigensolver) protocol provides a methodology for identifying molecular resonance energies by efficiently distributing the computational load [4].

Workflow Description

The process begins by defining the molecular system and configuring the classical high-throughput computing (HTC) environment to manage parallel tasks. The system then decomposes the resonance identification problem into numerous independent variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) tasks, which are distributed across available quantum resources. Each VQE task executes asynchronously on quantum processing units, with results asynchronously returned to the HTC system for continuous analysis until convergence criteria for resonance energies are met.

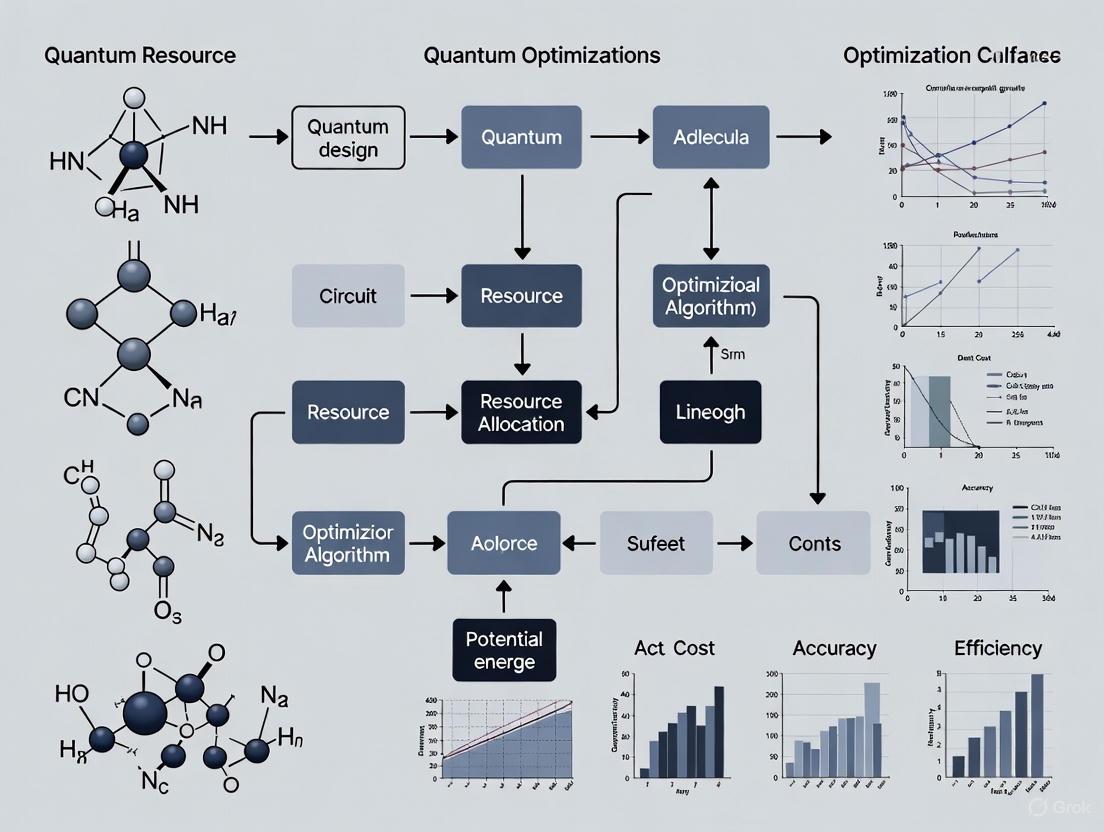

Diagram 1: qDRIVE Workflow

The diagram illustrates the parallelized workflow of the qDRIVE algorithm, showing how classical high-throughput computing (HTC) manages and refines multiple quantum processing unit (QPU) tasks to converge on a solution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | A hybrid algorithm used to find the ground (or excited) state energy of a molecular system, resistant to some noise [4]. |

| Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) | A significant algorithm for determining molecular properties with high precision, but it typically has substantial circuit depth and high gate counts [1]. |

| Complex Absorbing Potentials (CAPs) | A classical computational chemistry technique used in conjunction with quantum algorithms to model molecular resonances by preventing unphysical reflection of wavefunctions [4]. |

| Shadow Tomography | A method for efficiently characterizing quantum states with fewer measurements, reducing the resource overhead of state analysis [4]. |

| Sequential Minimal Optimization (SMO) | A classical optimization algorithm used in tandem with VQE to efficiently find the parameters that minimize the energy of the quantum system [4]. |

| N,3-dihydroxybenzamide | N,3-dihydroxybenzamide, CAS:16060-55-2, MF:C7H7NO3, MW:153.14 g/mol |

| N-(2-Mercapto-1-oxopropyl)-L-alanine | N-(2-Mercapto-1-oxopropyl)-L-alanine, CAS:26843-61-8, MF:C6H11NO3S, MW:177.22 g/mol |

Fundamental Concepts & FAQs

FAQ: Why is problem decomposition necessary in quantum computational chemistry? Classical computers struggle with the exponential scaling of resources required to simulate large molecular systems accurately. Problem decomposition techniques break down a single, intractable quantum computation into smaller, manageable subproblems that can be solved on today's noisy, intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. This can reduce the required number of qubits by a factor of 10 or more, making simulations of industrially relevant molecules feasible with current hardware [7].

FAQ: What is the core principle behind Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET)? DMET treats a fragment of a molecule as an open quantum system entangled with a surrounding "bath." The bath is constructed via a Schmidt decomposition of the mean-field wavefunction of the entire system. This creates a smaller, embedded quantum problem for each fragment that retains crucial correlation effects from the whole molecule. The process is iterated until the chemical potential and electron counts converge self-consistently [7] [8].

FAQ: My quantum hardware resources are limited. Which decomposition method should I prioritize? For near-term experiments, DMET is a highly recommended approach. It has been successfully demonstrated on real quantum hardware for systems like hydrogen rings and cyclohexane conformers, achieving chemical accuracy (within 1 kcal/mol of classical benchmarks) using only 27 to 32 qubits on an IBM quantum processor [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inaccurate Fragment Energy Despite Correct Circuit Execution

- Problem: The energy obtained for a fragment is not chemically accurate, even though the quantum circuit executed without apparent errors.

- Solution:

- Check Bath Orbital Construction: The accuracy of the bath orbitals in DMET is critical. Verify the initial mean-field (Hartree-Fock) calculation for the entire molecule.

- Review Active Space Selection: Ensure the fragment and its corresponding bath form a meaningful active space. Correlated electrons should be included in the fragment.

- Implement Error Mitigation: Apply readout error mitigation, gate twirling, and dynamical decoupling to reduce hardware noise impacting your results [8].

- Purify the Density Matrix: Use post-processing density matrix purification algorithms on the results from the quantum computer to mitigate residual errors and ensure the output represents a physically valid quantum state [7].

Issue: Failure to Achieve Self-Consistency in the DMET Cycle

- Problem: The DMET cycle does not converge; the total electron number oscillates or drifts.

- Solution:

- Adjust the Chemical Potential (μ): The update algorithm for the chemical potential between cycles is crucial for convergence. Implement a robust root-finding method to adjust μ based on the difference between the computed and actual electron count [7].

- Increase Fragment Size: If possible, slightly increase the fragment size. Larger fragments can capture more correlation effects and lead to more stable convergence, at the cost of requiring more qubits.

- Verify Qubit Connectivity: For the fragment calculation, ensure the variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) ansatz is compatible with your hardware's qubit connectivity. Use a qubit coupled-cluster (QCC) ansatz for efficient implementation on hardware with full connectivity, like trapped-ion systems [7].

Issue: High Sampling Overhead in Hybrid Quantum-Classical Algorithms

- Problem: Algorithms like Sample-Based Quantum Diagonalization (SQD) require a large number of quantum measurements (samples), making the process computationally slow.

- Solution:

- Optimize Sample Budget: Start with a lower number of samples (e.g., 1,000-2,000) to tune parameters, then increase to 8,000-10,000 for final, high-accuracy production runs [8].

- Use an Adaptive Ansatz: Employ adaptive VQE techniques that dynamically adjust the quantum circuit (ansatz) based on intermediate results, improving efficiency and reducing the number of required measurements [4].

- Leverage High-Throughput Computing: Use classical high-throughput computing (HTC) systems to run thousands of quantum circuit sampling jobs in parallel, as demonstrated by the qDRIVE algorithm, to minimize overall computation time [4].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: End-to-End DMET Pipeline for a Hydrogen Ring This protocol details the steps to simulate the potential energy curve of a ring of hydrogen atoms, a common benchmark system [7].

- System Fragmentation: Use DMET to divide the H10 ring into ten identical one-atom fragments. Due to symmetry, you only need to solve for one fragment.

- Hamiltonian Construction: For a single fragment, construct the embedded Hamiltonian (see Eqn. 1 in Fundamental Concepts). This includes one-electron and two-electron interactions within the fragment and its bath, minus a chemical potential term.

- Qubit Mapping: Transform the resulting fermionic Hamiltonian into a qubit Hamiltonian using the symmetry-conserving Bravyi-Kitaev (scBK) transformation to reduce qubit requirements [7].

- Ansatz Preparation: Prepare the quantum circuit using the Qubit Coupled Cluster (QCC) ansatz. The QCC operator is defined as: (\hat{U}(\boldsymbol{\tau}) = \prod{k}^{ng} \exp\left(-\frac{i \tauk \hat{P}k}{2}\right)) where (\tauk) is a variational parameter and (\hat{P}k) is a multi-qubit Pauli operator [7].

- VQE Execution: Run the VQE algorithm on the quantum hardware to find the minimal expectation value of the fragment's Hamiltonian.

- Post-Processing and Purification: Apply a density matrix purification algorithm to the raw quantum result to ensure physical consistency.

- DMET Cycle: Check for global self-consistency on the electron count. If not converged, update the chemical potential and return to step 2.

The workflow for this protocol and the related qDRIVE method can be visualized below.

Diagram 1: Hybrid Quantum-Classical Workflow for Molecular Simulation.

Diagram 2: The Self-Consistent DMET Cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 1: Key Computational Tools and Resources for Quantum Molecular Simulation.

| Item | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) | A problem decomposition technique that breaks a large molecular system into smaller, entangled fragment-bath subsystems. | Simulating a ring of 10 hydrogen atoms by decomposing it into ten 2-qubit problems instead of one 20-qubit problem [7]. |

| Sample-Based Quantum Diagonalization (SQD) | A quantum-tolerant algorithm that uses sampling and subspace projection to solve the Schrödinger equation. | Integrated with DMET to simulate cyclohexane conformers on real quantum hardware, achieving results within 1 kcal/mol of benchmarks [8]. |

| Qubit Coupled Cluster (QCC) Ansatz | A parametric quantum circuit ansatz designed for efficient execution on near-term quantum devices. | Used in VQE to compute the energy of a hydrogen ring fragment on a trapped-ion quantum computer [7]. |

| Quantum-Centric Supercomputing (QCSC) | A hybrid architecture where a quantum processor handles specific computation-intensive parts, supported by classical HPC. | The Cleveland Clinic's IBM-managed quantum computer is used in this paradigm for healthcare research, running fragment calculations [8]. |

| Error Mitigation Suite | A collection of techniques (e.g., gate twirling, dynamical decoupling) to reduce noise in NISQ devices. | Essential for achieving accurate energy results on current hardware like IBM's Eagle processors [8]. |

| 1-(3-Chlorophenyl)-2-methylpropan-2-amine | 1-(3-Chlorophenyl)-2-methylpropan-2-amine, CAS:103273-65-0, MF:C10H14ClN, MW:183.68 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Isopropylisothiazolidine 1,1-dioxide | 2-Isopropylisothiazolidine 1,1-dioxide, CAS:279669-65-7, MF:C6H13NO2S, MW:163.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Applications & Performance Data

Problem decomposition is enabling simulations of increasingly complex and chemically relevant systems. The table below summarizes performance data from recent experiments.

Table 2: Performance of Decomposition Methods on Quantum Hardware.

| Molecular System | Decomposition Method | Qubits Used | Accuracy Achieved | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H10 Ring | DMET with VQE & QCC [7] | 10 (as 10x 2-qubit problems) | Chemical Accuracy | Reproduced full configuration interaction (FCI) energy. |

| Cyclohexane Conformers | DMET with SQD [8] | 27-32 | Within 1 kcal/mol | Correct energy ordering of chair, boat, and twist-boat forms. |

| H18 Ring | DMET with SQD [8] | 27-32 | Minimal deviation from HCI benchmark | Accurately captured high electron correlation at stretched bond lengths. |

| General Molecular Resonances | qDRIVE [4] | 2-4 | Error below 1% (up to 0.00001% in ideal sim) | Identified resonance energies and wavefunctions for benchmark models. |

Core Concepts FAQ

What is the primary goal of the Active Space Approximation? The Active Space Approximation aims to make complex quantum chemical calculations computationally feasible by strategically focusing resources on the most electronically important parts of a molecular system. It classifies molecular orbitals into three categories: core orbitals (always doubly occupied), active orbitals (partially occupied), and virtual orbitals (always unoccupied) [9]. By solving the Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) problem exactly within a selected active space while treating the remaining orbitals in a mean-field manner, this method provides a balanced approach to capturing static correlation effects essential for accurately describing processes like bond dissociation without the prohibitive computational cost of a full FCI treatment on the entire system [9] [10].

How does Qubitized Downfolding (QD) optimize quantum resources? Qubitized Downfolding (QD) is a hybrid classical-quantum framework that dramatically reduces computational complexity by collapsing high-rank tensor operations into efficient, depth-optimal quantum circuits [11] [12]. It transforms the full many-body Hamiltonian into smaller-dimensional block-Hamiltonians through mathematical downfolding, reducing the scaling complexity from O(Nâ·â€“N¹â°) for methods like CCSD(T) and MRCI to O(N³) [11]. This approach implements these operations as tensor networks composed solely of two-rank tensors, enabling quantum circuits with O(N²) depth and requiring only O(log N) qubits [11] [12].

When should researchers choose between Active Space and Downfolding approaches? The choice depends on the specific computational constraints and research objectives. Active Space methods (like CASSCF) are well-established on classical computers for moderately sized systems where the active space remains small enough to handle the combinatorial growth of Slater determinants (typically up to 18 electrons in 18 orbitals) [10]. Qubitized Downfolding becomes advantageous when targeting larger molecular systems or when preparing for execution on quantum hardware, as it offers superior scaling and more efficient quantum resource utilization [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Implementation Challenges in Active Space Calculations

Problem: Exponential Growth of Active Space The number of Slater determinants in a Complete Active Space (CAS) calculation grows combinatorially with the number of active orbitals and electrons [10].

Table: Scaling of Slater Determinants in Active Space Calculations

| Active Orbitals | Active Electrons | Approximate Number of Determinants |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 6 | ~400 |

| 12 | 12 | ~270,000 |

| 18 | 18 | ~2 × 10⹠|

Solutions:

- Employ Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) to partition large systems into smaller, computationally tractable fragments while preserving entanglement [13]

- Use truncated CI methods (CIS, CISD, CISDT) within the active space instead of full CAS [10]

- Implement automated active space selection protocols based on natural orbital occupations or entanglement measures

Problem: Inaccurate Treatment of Dynamic Correlation Active Space methods primarily capture static correlation, potentially missing important dynamic correlation effects [9].

Solutions:

- Apply perturbative corrections such as CASPT2 or NEVPT2 to recover dynamic correlation [9]

- Use multi-reference approaches that combine active space wavefunctions with coupled-cluster methods

- Validate results against high-level benchmark calculations when possible

Quantum Resource Optimization in Downfolding

Problem: Excessive Qubit Requirements for Molecular Simulations Large molecules require substantial quantum resources that may exceed current hardware capabilities [13].

Solutions:

- Implement Tensor Factorized Hamiltonian Downfolding (TFHD) to reduce qubit requirements from O(N) to O(log N) [11]

- Apply fragmentation approaches like DMET to treat different molecular regions separately [13]

- Utilize qubit efficient encodings such as symmetry-adapted bases to minimize representation overhead

Problem: Unmanageable Quantum Circuit Depth Deep quantum circuits exceed coherence times of current NISQ devices [11].

Solutions:

- Employ block-encoding strategies that optimize circuit depth to O(N²) [11]

- Implement circuit compression techniques to consolidate redundant operations

- Use variational forms with minimal parameter counts and shallow depth

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) with VQE Co-optimization

This protocol enables geometry optimization of large molecules by combining DMET with Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) in a co-optimization framework [13].

Table: Key Components of DMET-VQE Co-optimization Framework

| Component | Function | Resource Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Fragment Partitioning | Divides molecular system into smaller subsystems | Reduces qubit requirements for quantum processing |

| Bath Orbital Construction | Preserves entanglement between fragments | Maintains accuracy despite system fragmentation |

| Embedded Hamiltonian | Projects full Hamiltonian into smaller subspace | Enables treatment of systems larger than quantum hardware limits |

| Simultaneous Co-optimization | Optimizes geometry and variational parameters together | Eliminates nested optimization loops, reducing computational cost |

Methodology:

- System Partitioning: Divide the molecular system into fragments, typically selecting individual atoms as fragments with the remaining system as the environment [13]

- Schmidt Decomposition: Perform bipartite decomposition of the quantum state to identify entangled bath orbitals [13]:

|Ψ⟩ = Σλâ‚|ψ~â‚ᴬ⟩|ψ~â‚ᴮ⟩ - Embedded Hamiltonian Construction: Project the full Hamiltonian into the combined fragment-bath space [13]:

Ĥemb = P̂ĤP̂ - Simultaneous Optimization: Co-optimize nuclear coordinates and quantum circuit parameters using gradient information from the generalized Fock matrix [13] [10]

DMET-VQE Co-optimization Workflow

Protocol 2: Tensor Factorized Hamiltonian Downfolding (TFHD)

This protocol implements the mathematical framework for reducing the scaling complexity of electronic correlation problems [11].

Methodology:

- Hilbert Space Bipartition: Partition the many-body Hilbert space into electron-occupied and electron-unoccupied blocks for a given orbital [11]

- Downfolding Transformation: Apply a unitary transformation that decouples the electron-occupied block from its complement [11]

- Tensor Factorization: Factorize high-rank electronic integrals and cluster amplitude tensors into low-rank tensor factors [11]

- Quantum Circuit Implementation: Implement the factorized tensors as depth-optimal, block-encoded quantum circuits [11]

Key Mathematical Operations:

- The downfolding transformation maps the full many-body Hamiltonian to smaller dimensional block-Hamiltonians

- High-rank tensors are decomposed into networks of rank-2 tensors

- Residual equations for Hamiltonian downfolding are solved with O(N³) complexity instead of O(Nâ·â€“N¹â°) [11]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Computational Resources for Active Space and Downfolding Methods

| Resource | Function | Implementation Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Fock Matrix | Provides orbital gradient information for MCSCF convergence | Fₘₙ = ΣDₚqʰₚq + ΣΓₘqᵣsɡₙqᵣs [10] | ||

| Inactive Fock Operator | Downfolds inactive orbitals into active space | Fₘₙᴵ = ʰₘₙ + Σ(2ɡₘₙᵢᵢ - ɡₘᵢᵢₙ) [10] | ||

| Active Space Transformer | Reduces Hamiltonian to active space representation | Replaces one-body integrals with inactive Fock operator [14] | ||

| Block-Encoding Framework | Implements tensor operations as quantum circuits | Creates O(N²) depth circuits with O(log N) qubits [11] | ||

| DMET Projector | Constructs embedded Hamiltonian for fragments | PÌ‚ = Σ | ψ~â‚ᴬψ~â‚ᴮ⟩⟨ψ~â‚ᴬψ~â‚á´· | [13] |

| 7-Bromo-4-chloro-8-methylquinoline | 7-Bromo-4-chloro-8-methylquinoline, CAS:1189106-50-0, MF:C10H7BrClN, MW:256.52 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | ||

| 2-(Azetidin-3-yl)-4-methylthiazole | 2-(Azetidin-3-yl)-4-methylthiazole|CAS 1228254-57-6 | High-purity 2-(Azetidin-3-yl)-4-methylthiazole for pharmaceutical research. Explore its applications in antiviral and antimicrobial studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Hybrid Quantum-Classical Computational Pathway

Performance Metrics & Validation

Benchmarking Results:

- The DMET-VQE framework successfully determined the equilibrium geometry of glycolic acid (C₂H₄O₃), a molecule previously considered intractable for quantum geometry optimization [13]

- TFHD demonstrates super-quadratic speedups for expensive quantum chemistry algorithms on both classical and quantum computers [11]

- The co-optimization approach drastically reduces computational cost while maintaining high accuracy compared to classical reference methods [13]

These methodologies represent significant advances toward practical, scalable quantum simulations that move beyond the small proof-of-concept molecules that have historically dominated quantum computational chemistry [13].

The Role of Error Mitigation in Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) Era

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between Quantum Error Correction (QEC) and Quantum Error Mitigation (QEM)?

A1: The core difference lies in their approach and target era:

- Quantum Error Correction (QEC): A long-term strategy for fault-tolerant quantum computing. It uses redundancy by encoding a single "logical qubit" into many physical qubits. QEC actively detects and corrects errors as they occur during the computation, preventing errors from accumulating. Its overhead is significant, requiring many extra qubits and complex control, but it enables arbitrarily long computations [15] [16] [17].

- Quantum Error Mitigation (QEM): A suite of strategies for the current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era. QEM does not prevent errors. Instead, it uses additional circuit runs and classical post-processing to estimate and subtract the effects of noise from the final computational results. It is a software-based "reliability layer" for today's imperfect hardware [15] [16] [18].

Q2: My VQE result for a molecule's ground state energy is noticeably off from the classical benchmark. What is a chemistry-specific error mitigation technique I can use?

A2: For quantum chemistry problems, Reference-State Error Mitigation (REM) is a highly effective and low-overhead technique [19]. The protocol is:

- Prepare a Reference State: Choose a classically tractable state close to your target state, typically the Hartree-Fock state, and prepare it on the quantum device.

- Measure Noisy Reference Energy: Run the circuit and measure the energy of this reference state on the noisy quantum hardware (

E_ref_noisy). - Compute Exact Reference Energy: Classically compute the exact energy for the same reference state (

E_ref_exact). - Apply the Correction: The error-mitigated energy for your target VQE state (

E_VQE_mitigated) is calculated as:E_VQE_mitigated = E_VQE_noisy - (E_ref_noisy - E_ref_exact). This method assumes the hardware-induced error is similar for the reference and target VQE states [19].

Q3: The measurement results from my quantum circuit show high bias. How can I correct for readout errors?

A3: You can apply Measurement Error Mitigation. This technique involves [15] [20]:

- Characterize the Readout Noise: Prepare each of the known computational basis states (e.g.,

|000...0>,|000...1>, ...,|111...1>) and measure them many times. - Build a Confusion Matrix: This constructs a calibration matrix

Mthat describes the probability of the device reporting outcomejwhen the true state wasi. - Invert the Matrix: Apply the inverse of this calibration matrix,

Mâ»Â¹, to the probability distribution obtained from your actual experiment. This classical post-processing step effectively corrects the biased statistics.

Q4: When I run deeper quantum circuits, the noise seems to overwhelm the results. Is there a way to extrapolate to a "zero-noise" result?

A4: Yes, Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) is designed for this scenario [15] [18] [21]. The methodology is:

- Intentionally Scale Noise: Run the same quantum circuit at multiple, intentionally increased noise levels. This can be done by stretching pulse durations (pulse stretching) or inserting pairs of identity gates that ideally cancel out but add more noise in practice.

- Measure at Different Noise Levels: For each noise scale factor (e.g., 1x, 2x, 3x the base noise level), compute your observable of interest (e.g., an energy value).

- Extrapolate: Fit a curve (e.g., linear, exponential) to the data points of observable vs. noise strength and extrapolate back to a hypothetical zero-noise limit to get a cleaner estimate.

Q5: For strongly correlated molecules, the simple REM method fails. What are my options?

A5: Recent research has developed Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM) for precisely this challenge [19]. Instead of using a single Hartree-Fock determinant, MREM uses a compact multireference wavefunction (a linear combination of a few dominant Slater determinants) as the reference state. These states have a much better overlap with the strongly correlated true ground state. They are prepared on the quantum device using structured circuits, such as those based on Givens rotations, and the same REM correction protocol is applied for significantly improved results [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Rapidly Growing Sampling Overhead in Error Mitigation

Symptoms: The number of circuit repetitions ("shots") required to obtain a result with an acceptable error bar becomes impractically large, especially as the circuit width or depth increases.

Diagnosis: This is a fundamental challenge with many powerful error mitigation techniques, particularly Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC). The sampling overhead, γ_tot, grows exponentially with the number of gates in the circuit [18].

Resolution Steps:

- Technique Selection: For large circuits, prefer ZNE over PEC, as its overhead is typically independent of qubit count and requires only a 3-5x increase in circuit evaluations, not an exponential number [21].

- Hybrid Approaches: Use a combination of lower-overhead techniques. For example, first apply measurement error mitigation, then use ZNE.

- Problem-Informed Mitigation: Leverage domain knowledge. In quantum chemistry, use REM or MREM [19], and symmetry verification [15], which exploit the specific structure of the problem to reduce overhead compared to general-purpose methods.

- Circuit Optimization: Before mitigation, aggressively optimize your quantum circuit to reduce its depth and gate count, as this directly reduces the mitigation overhead.

Problem 2: Inaccurate Zero-Noise Extrapolation

Symptoms: The ZNE result is unstable, highly sensitive to the choice of scale factors or extrapolation model, or clearly deviates from the expected value.

Diagnosis: The core assumption of ZNE—that the noise's impact on the observable follows a predictable trend—may be violated. The simple "unitary folding" method of scaling noise may not accurately represent how errors compound in your specific circuit [21].

Resolution Steps:

- Improve Noise Scaling: Instead of simple unitary folding, use pulse-level control (e.g., through OpenPulse) to stretch gate durations for a more physically accurate noise scaling [18] [21].

- Refine the Metric: Investigate new metrics like Qubit Error Probability (QEP) to more accurately quantify and scale noise, as proposed in the Zero Error Probability Extrapolation (ZEPE) method [21].

- Validate Extrapolation Model: Test multiple extrapolation models (linear, polynomial, exponential). Use Richardson extrapolation if the noise model is well-characterized. Cross-validate the results with simulator outputs for small, tractable instances.

- Control Data Points: Use more than two noise scale factors to better capture the trend and identify outliers.

Problem 3: Symmetry Violations in Quantum Simulation

Symptoms: In simulations of molecular systems or physical models, the computed state violates known conserved quantities, such as particle number (U(1) symmetry) or total spin (SU(2) symmetry).

Diagnosis: Quantum noise can kick the computed state out of the physical "legal" subspace defined by these symmetries [15].

Resolution Steps:

- Symmetry Verification: A post-processing technique where you:

- Measure Symmetry Operators: After running your main circuit, measure the operators corresponding to the conserved quantities (e.g., the total particle number

Nor total spinS²). - Post-Select or Re-weight: Discard (post-select) any circuit runs where the symmetry measurement does not match the known value. Alternatively, re-weight the results based on the measured symmetry value to suppress unphysical contributions [15] [19].

- Measure Symmetry Operators: After running your main circuit, measure the operators corresponding to the conserved quantities (e.g., the total particle number

- Use Symmetry-Preserving Ansätze: Design your variational quantum circuit (ansatz) to inherently preserve the symmetries of the problem, making the state more resilient to noise.

Comparison of Key Error Mitigation Techniques

The table below summarizes the core QEM techniques to help you select the right tool for your problem.

| Technique | Core Principle | Best For | Key Overhead | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Error Mitigation [15] [20] | Characterize and invert readout noise using a calibration matrix. | Correcting biased measurement outcomes at the end of any circuit. | Polynomial in number of qubits (building the matrix). | Only corrects measurement errors, not in-circuit noise. |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) [15] [18] [21] | Scale noise, run circuit at multiple noise levels, and extrapolate to zero noise. | Mid-depth circuits where noise has a predictable impact on an observable. | Constant factor (3-5x more circuit evaluations). | Sensitive to extrapolation method; can amplify statistical uncertainty. |

| Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC) [15] [18] | Represent ideal gates as a linear combination of noisy operations and sample from them. | High-accuracy results on shallower circuits where the sampling cost is tolerable. | Exponential in number of gates (sampling overhead). | Requires precise noise model; exponential scaling makes it infeasible for deep circuits. |

| Symmetry Verification [15] | Check conserved quantities and discard/re-weight results that violate them. | Quantum simulations where symmetries (particle number, spin) are known. | Polynomial in number of qubits (measuring symmetries). | Only mitigates errors that violate the specific symmetry; useful signal can be lost in post-selection. |

| (Multi)Reference-State Error Mitigation (MREM) [19] | Use a classically solvable reference state to estimate and subtract the hardware error. | Quantum chemistry calculations (VQE), especially with strong electron correlation. | Low (requires one extra classical computation and quantum measurement). | Effectiveness depends on the quality and overlap of the chosen reference state with the true target state. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Zero-Noise Extrapolation with a Quantum Chemistry VQE

This protocol details how to integrate ZNE into a Variational Quantum Eigensolver workflow to obtain a more accurate molecular ground-state energy.

1. Define the Problem and Run Standard VQE:

- Define the molecular Hamiltonian

H(x)for nuclear coordinatesx[22]. - Choose a variational ansatz

U(θ)and initial parametersθ. - Optimize the parameters to minimize the noisy energy expectation value

E(θ)_noisy = <0| U†(θ) H(x) U(θ) |0>measured on the quantum device.

2. Scale the Circuit Noise:

- Select a noise scaling method. A common digital approach is unitary folding, where you replace a gate

GwithG * (G†* G)^nto increase depth without changing the ideal functionality [18]. - Define a set of noise scale factors, e.g.,

[1, 2, 3].

3. Execute Scaled Circuits:

- For each scale factor

λin[1, 2, 3], create a scaled version of your optimized VQE circuit. - Run each scaled circuit on the quantum device and measure the energy expectation value

E(θ)_λ.

4. Perform Extrapolation:

- Plot the measured energies

E(θ)_λagainst their corresponding scale factorsλ. - Fit an extrapolation model (e.g., a linear or quadratic function) to these data points.

- Evaluate the fitted function at

λ = 0to obtain the error-mitigated, zero-noise energy estimateE_(ZNE).

Protocol 2: Applying Multireference Error Mitigation (MREM) for Strong Correlation

This protocol uses advanced classical chemistry methods to enhance error mitigation for challenging molecules like Fâ‚‚ or Nâ‚‚ at dissociation [19].

1. Generate a Multireference State Classically:

- Use an inexpensive classical method (e.g., CASSCF(2,2), DMRG, or selected CI) to generate a compact multireference wavefunction

|Ψ_MR>for your target molecule. - This wavefunction should be a linear combination of a few important Slater determinants:

|Ψ_MR> = c1 |D1> + c2 |D2> + ... + ck |Dk>.

2. Prepare the State on the Quantum Computer:

- Compile the multireference state

|Ψ_MR>into a quantum circuit. This can be efficiently done using Givens rotation circuits, which are structured and preserve physical symmetries [19]. - This circuit (

V), when applied to a simple initial state, prepares|Ψ_MR> ≈ V |0>.

3. Execute the MREM Protocol:

- Mitigated Target Energy: Prepare your final VQE state

|Ψ(θ)>and measure its noisy energy on the hardware:E_VQE_noisy. - Mitigated Reference Energy: Prepare the multireference state

|Ψ_MR>using circuitVand measure its noisy energy:E_MR_noisy. - Classical Reference Energy: Classically compute the exact energy of the multireference state

|Ψ_MR>:E_MR_exact. - Calculate Final Energy: Apply the MREM correction:

E_MREM = E_VQE_noisy - (E_MR_noisy - E_MR_exact).

Workflow and System Diagrams

ZNE for VQE Energy Estimation

MREM for Strong Correlation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key software tools and conceptual "reagents" essential for implementing quantum error mitigation in molecular calculations research.

| Item Name | Type | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Mitiq [18] | Software Library | An open-source Python toolkit for error mitigation. It seamlessly integrates with other libraries (Qiskit, Cirq) and provides implemented ZNE and PEC protocols. |

| Qiskit [23] [18] | Software Library | IBM's full-stack quantum SDK. Provides access to real devices, simulators with noise models, and built-in error mitigation methods like measurement error mitigation. |

| PennyLane [22] | Software Library | A cross-platform library for differentiable quantum programming. Excellent for hybrid quantum-classical algorithms like VQE and offers built-in tools for quantum chemistry and error mitigation. |

| Givens Rotations [19] | Quantum Circuit Component | A specific type of quantum gate used to prepare multireference states efficiently. They are crucial for implementing MREM, as they preserve symmetries and have a known, efficient circuit structure. |

| Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) [13] | Classical Method | A classical embedding theory used to fragment large molecules into smaller, tractable fragments. It reduces qubit requirements and can be combined with VQE in a co-optimization framework for larger systems. |

Symmetry Operators (e.g., N, S²) [15] |

Conceptual Tool | The operators corresponding to conserved quantities (particle number, total spin). Measuring them is the foundation of symmetry verification, a powerful QEM technique for quantum simulations. |

| Ethyl 2,2-Difluorocyclohexanecarboxylate | Ethyl 2,2-Difluorocyclohexanecarboxylate, CAS:186665-89-4, MF:C9H14F2O2, MW:192.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Cyclopropyloxazole-4-carbonitrile | 2-Cyclopropyloxazole-4-carbonitrile, CAS:1159734-36-7, MF:C7H6N2O, MW:134.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Practical Frameworks and Algorithms for Resource-Efficient Quantum Chemistry

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary resource optimization advantage of integrating DMET with VQE for molecular geometry optimization?

A1: The integration significantly reduces the quantum resource requirements, which is crucial for near-term quantum devices. Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) fragments a large molecule into smaller, manageable subsystems [24]. This means the VQE algorithm, which is used as a solver for the electronic structure within each fragment, only needs to run on a reduced number of qubits corresponding to the fragment size, not the entire molecule [24]. This approach makes the simulation of larger molecules, like glycolic acid, feasible on current hardware [24].

Q2: Our VQE optimization is stuck; the energy does not converge. What could be the cause?

A2: This is a common challenge and often points to the "barren plateau" phenomenon, where the gradient of the cost function vanishes exponentially with the number of qubits [25]. Other potential causes include:

- Inadequate circuit ansatz: The chosen parameterized quantum circuit might not be expressive enough for the system [25].

- Noise: Current NISQ devices have significant gate and readout errors that can impede convergence [4] [26].

- Classical optimizer failure: The classical optimization routine may be unsuitable for the quantum circuit's landscape [4]. Mitigation strategies include using error mitigation techniques, exploring different circuit ansatzes, and employing robust classical optimizers like BOBYQA or Sequential Minimal Optimization [4].

Q3: How does the direct co-optimization method in this framework improve efficiency?

A3: Unlike traditional methods that iteratively and separately optimize the electronic structure (with VQE) and then the molecular geometry, the direct co-optimization framework updates both the quantum variational parameters and the molecular geometry simultaneously [24]. This integrated approach removes the need for costly iterative loops, drastically reducing the number of quantum evaluations required and accelerating convergence [24].

Q4: What level of accuracy has been demonstrated with this hybrid approach?

A4: The framework has been rigorously validated. For the benchmark molecule glycolic acid (C₂H₄O₃), the method produced equilibrium geometries that matched the accuracy of classical reference methods while significantly reducing computational cost [24]. In other quantum-classical resonance identification simulations, methods like qDRIVE have achieved relative errors as low as 0.00001% in ideal noiseless simulations, with errors remaining below 1-2% in most simulations that incorporate statistical noise [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High Energy Error in Fragment Calculation

Problem: The energy calculated by VQE for a molecular fragment is significantly higher than expected, leading to inaccurate total energy.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate Bath Orbital Construction | Check the convergence of the low-level mean-field calculation for the entire molecule. | Ensure the DMET self-consistent field procedure is fully converged before fragmenting [25]. |

| VQE Not converged to Ground State | Monitor the VQE optimization trajectory. Check for large energy fluctuations or early stopping. | Use a more expressive quantum circuit ansatz. Restart the classical optimizer with different initial parameters [4] [25]. |

| Quantum Hardware Noise | Run the same VQE circuit on a noise-free simulator and compare results. | Employ readout error mitigation and, if available, zero-noise extrapolation techniques [4] [26]. |

Issue: Molecular Geometry Optimization Fails to Converge

Problem: The algorithm iterates but cannot find a stable molecular geometry (equilibrium structure).

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate Energy Gradient | The forces on atoms, computed via the Hellmann-Feynman theorem, are noisy or incorrect [24]. | Verify the implementation of the gradient calculation. Increase the number of measurement shots to reduce statistical noise. |

| Classical Optimizer Incompatibility | The geometry optimizer (e.g., BFGS) is sensitive to noise in the energy landscape. | Switch to a noise-resilient, derivative-free optimizer such as BOBYQA [4]. |

| Strong Correlation Between Parameters | The geometry parameters and quantum circuit parameters are highly correlated. | Leverage the direct co-optimization method to update all parameters simultaneously, which improves convergence [24]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Geometry Optimization of Glycolic Acid

This protocol is based on the landmark achievement of optimizing glycolic acid, a molecule of a size previously intractable for quantum algorithms [24].

- System Preparation: Generate an initial 3D structure for the glycolic acid (C₂H₄O₃) molecule using classical software.

- DMET Fragmentation: Partition the molecule into smaller fragments. The exact number and size of fragments are system-dependent [24].

- Quantum Resource Allocation: For each fragment, map the electronic structure problem to a qubit Hamiltonian using a transformation like Jordan-Wigner. The fragment size determines the number of qubits required on the quantum processor [24].

- VQE Execution per Fragment:

- Ansatz Selection: Choose a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) suitable for the chemical system.

- Parameter Optimization: For a given geometry, run the VQE algorithm to find the ground-state energy of each fragment. A classical optimizer (e.g., BOBYQA) adjusts the quantum circuit parameters to minimize the energy [4] [24].

- Direct Co-optimization: Use the Hellmann-Feynman theorem to compute the energy gradient with respect to atomic coordinates. A classical optimizer uses this information to propose a new, lower-energy molecular geometry. Crucially, the quantum circuit parameters and geometry parameters are optimized simultaneously [24].

- Convergence Check: Repeat steps 4 and 5 until the molecular geometry converges, meaning the energy and atomic forces are minimized below a predefined threshold.

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key quantitative results from relevant hybrid quantum-classical experiments, illustrating current capabilities and error tolerances.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Hybrid Quantum-Classical Methods

| Method / System | Key Metric | Result / Error | Conditions / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| qDRIVE (Resonance Identification) [4] | Relative Energy Error | < 1% (most simulations), max 2.8% | With statistical noise on simulator |

| As low as 0.00001% | Ideal, noiseless simulation | ||

| 0.91% - 35% | With simulated IBM Torino processor noise | ||

| DMET+VQE Framework (Geometry Optimization) [24] | System Size | Glycolic Acid (C₂H₄O₃) | First quantum geometry optimization of this size |

| Accuracy | High-fidelity geometries matching classical reference | ||

| MPS-VQE Emulation [26] | Emulation Scale | 92-1000 qubits | On Sunway supercomputer (classical emulation) |

| Performance | 216.9 PFLOP/s |

Workflow Visualization

Table 2: Key Resources for Hybrid Quantum-Classical Experiments

| Category | Item / Solution | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Frameworks | Qiskit, Intel Quantum SDK, CUDA-Q [4] [27] | Software development kits for designing, simulating, and running quantum circuits. |

| Classical Compute & HPC | High-Throughput Computing (HTC), Sunway/Condor/DIRAC systems [4] [26] | Manages the parallel execution of thousands of independent VQE tasks and complex classical post-processing. |

| Embedding & Fragmentation | Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) | Divides a large molecular system into smaller, quantum-manageable fragments, reducing qubit requirements [24]. |

| Quantum Solvers | Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | A hybrid algorithm used to find the ground-state energy of a quantum system (e.g., a molecular fragment) on a noisy quantum device [24]. |

| Classical Optimizers | BOBYQA, SMO (Sequential Minimal Optimization) [4] | Classical algorithms that adjust quantum circuit parameters to minimize energy; chosen for noise resilience. |

| Error Mitigation | Readout Error Mitigation, Zero-Noise Extrapolation [4] | Post-processing techniques to correct for errors inherent in NISQ-era quantum hardware. |

Leveraging Multi-Qubit Gates in Neutral-Atom Quantum Computers for Faster Simulations

For researchers in molecular calculations, neutral-atom quantum computers offer a unique path to quantum resource optimization through their native implementation of multi-qubit gates. Unlike most quantum computing platforms limited to two-qubit interactions, neutral-atom systems can execute gates that entangle three or more qubits in a single, native operation [28] [29]. This capability directly addresses a key bottleneck in quantum simulations: circuit depth. By significantly reducing the number of gate operations required for complex algorithms like Variational Quantum Eigensolvers (VQE) for molecular energy calculations, these multi-qubit gates minimize the accumulation of errors and accelerate simulation times, bringing practical quantum-enhanced drug discovery closer to reality [28].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the specific advantages of native multi-qubit gates for molecular simulations?

For molecular simulations, algorithms must often encode complex electron interactions, which can require many two-qubit gates on most hardware. Native multi-qubit gates, such as the controlled-phase gates with multiple controls (C_nP), allow you to implement these interactions more directly. This leads to a substantial reduction in circuit depth [28]. For near-term devices susceptible to errors, shorter circuits directly translate to higher overall fidelity in your computed molecular energies and properties.

2. How does the Rydberg blockade enable multi-qubit gates? The fundamental mechanism is the Rydberg blockade [29]. When an atom is excited to a high-energy Rydberg state, its electron cloud "puffs up" to a size much larger than the original atom. This creates a strong, long-range interaction that prevents other atoms within a certain "blockade radius" from being excited to the same Rydberg state. By cleverly designing laser pulses, you can engineer a conditional logic where the excitation of one "control" atom dictates the possible evolution of multiple "target" atoms, resulting in a native multi-qubit entangling gate.

3. What are the typical fidelities for these gates, and how do they impact error correction?

Current experimental demonstrations have achieved two-qubit gate fidelities of 99.5% on neutral-atom platforms, surpassing the common threshold for surface-code quantum error correction [30]. While specific fidelity numbers for N-qubit gates (where N>2) are an active area of research, their primary benefit for error correction is reducing the number of physical operations needed to implement a logical operation. Fewer operations mean fewer opportunities for errors to occur, thereby lowering the overhead required for fault-tolerant quantum computation [31].

4. My simulation requires all-to-all qubit connectivity. Is this possible? Yes, this is a key strength of the neutral-atom platform. Using optical tweezers, you can dynamically rearrange atoms into any desired configuration [29]. Furthermore, you can coherently "shuttle" atoms during a calculation, effectively creating a fully programmable interconnect between any qubits in the array [31] [29]. This is invaluable for molecular systems where interactions are not limited to nearest neighbors.

5. What is the difference between analog and digital modes for simulation? You can choose the optimal mode for your problem [29]:

- Digital Mode: You decompose your quantum algorithm into a discrete sequence of single-, two-, and multi-qubit gates. This offers universality but can accumulate errors from each gate.

- Analog Mode: You directly engineer the system's Hamiltonian to mimic the molecular Hamiltonian you wish to study. This approach can be more efficient and less prone to errors for specific simulation tasks, as it bypasses the need for gate decomposition.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Fidelity in Multi-Qubit Gate Operations

Problem: The measured fidelity of your implemented multi-qubit gate is below theoretical expectations, introducing errors in your molecular energy calculation.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Check Laser Pulse Calibration:

- Symptoms: Inconsistent gate performance, high population in unwanted Rydberg states.

- Solution: Implement optimal control techniques for pulse shaping. Use parametrized families of laser pulses (e.g., with sinusoidal phase modulation or smooth amplitude profiles) that are designed to be robust against experimental imperfections and minimize population in error-prone intermediate states [28] [30]. Re-calibrate global parameters like Rabi frequency and detuning.

Verify Rydberg Blockade Condition:

- Symptoms: Simultaneous excitation of atoms that should be blockaded.

- Solution: Confirm that the interatomic distances in your array are well within the Rydberg blockade radius. This radius is a function of the principal quantum number

nof the Rydberg state and the laser's Rabi frequency. Ensure your atom placement accounts for this physical constraint.

Mitigate Atomic Motion and Decoherence:

- Symptoms: Fidelity degrades with longer gate durations or larger arrays.

- Solution: Employ advanced cooling techniques like Λ-enhanced grey molasses to achieve lower atomic temperatures (reducing phonon occupation to

~1-2) [30]. Use faster gate protocols to complete operations within the system's coherence time, minimizing the impact of environmental noise and Rydberg state decay.

Issue 2: High Atom Loss During Experiments

Problem: Atoms are lost from the optical traps over the course of your circuit, particularly after Rydberg excitation, leading to incomplete data.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Optimize Trap Parameters:

- Symptoms: Sudden loss of atoms during or immediately after the application of Rydberg excitation pulses.

- Solution: Increase the depth of your optical tweezers to better confine atoms during state changes. Ensure the trap laser wavelength is far-detuned from atomic transitions to minimize scattering.

Implement Atom Replenishment and Loss-Tolerant Design:

- Symptoms: Gradual depletion of the array over multiple experimental cycles.

- Solution: Leverage the platform's capability for continuous atom replenishment, which can maintain thousands of atoms indefinitely [32]. For quantum error correction (QEC) experiments, design your circuits to be loss-tolerant. Use a machine learning-based decoder that can handle erasure errors and employ techniques like "superchecks" to validate stabilizer measurements even when individual atoms are lost [31].

Issue 3: Inconsistent Gate Performance Across the Array

Problem: The same gate operation has different fidelities when applied to different subsets of qubits in your processor.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Address Laser Intensity Inhomogeneity:

- Symptoms: A correlation between qubit position in the array and gate error rate.

- Solution: Use larger, top-hat profile Rydberg beams to ensure a uniform intensity across the entire processing zone [30]. Characterize the intensity profile and post-process results to account for spatial variations.

Characterize and Manage Crosstalk:

- Symptoms: Gates applied in parallel influence each other's outcomes.

- Solution: While Rydberg interactions are the basis for gates, unintended interactions between non-nearest neighbors can cause crosstalk. Introduce larger spacing between simultaneously executed gate operations or use pulse sequences that are designed to suppress such correlated errors [33].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Benchmarking a Parametrized Multi-Qubit Gate

This protocol outlines the steps to characterize a C_2P (double-controlled phase) gate for use in a molecular simulation circuit.

- Atom Array Preparation: Load a defect-free array of

^87Rb atoms using optical tweezers. Cool the atoms using Λ-enhanced grey molasses to a radial temperature with phonon occupation~1-2[30]. - Qubit Initialization: Initialize all qubits to the fiducial ground state

|0⟩via optical pumping and laser cooling techniques [34]. - Laser Pulse Application: Apply a globally addressed, parametrized laser pulse to perform the

C_2Pgate. The pulse should use a two-photon transition to a Rydberg state (e.g.,n=53), with a large intermediate-state detuning to minimize scattering [30]. The pulse profile (phase and amplitude) should be optimized via numerical methods for robustness [28]. - State Tomography: After gate application, perform quantum state tomography on the involved qubits to reconstruct the density matrix and calculate the process fidelity.

- Interleaved Randomized Benchmarking (Optional): For a more scalable benchmark, interleave the

C_2Pgate with random single-qubit gates and fit the decay of the sequence fidelity to extract the average gate fidelity [30].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Neutral-Atom Gates

| Metric | Current State-of-the-Art | Impact on Molecular Simulations |

|---|---|---|

| Two-Qubit Gate Fidelity | 99.5% [30] | Determines the baseline accuracy for simulating molecular bond interactions. |

| Single-Qubit Gate Fidelity | >99.97% [30] | Critical for preparing initial states and applying rotations in VQE. |

| Parallel Gate Operation | Up to 60 atoms simultaneously [30] | Dramatically reduces total circuit runtime for large molecules. |

| Qubit Coherence Time | >1 second [29] | Sets the maximum allowable depth for your quantum circuit. |

Protocol 2: Integrating Multi-Qubit Gates into a VQE for a Molecule

This protocol describes how to leverage a multi-qubit gate within a VQE cycle to compute the ground state energy of a molecule like Glycolic Acid (C₂H₄O₃).

- Molecular Hamiltonian Generation: Classically compute the one- and two-electron integrals of your target molecule in a chosen basis set. Then, map the fermionic Hamiltonian to a qubit Hamiltonian using a transformation like Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev.

- Circuit Ansatz Design: Design your parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz). Identify sub-circuits that implement many-body interaction terms (e.g., a cluster of interacting spin-orbitals) and replace sequences of two-qubit gates with a single, native

C_nPgate where possible [28]. - Hybrid Quantum-Classical Loop:

- Quantum Processing: On the neutral-atom processor, execute the ansatz circuit. This involves preparing the qubits, applying the sequence of gates (including the multi-qubit gate), and measuring the final energy expectation value.

- Classical Processing: A classical optimizer (e.g., BFGS) receives the energy value and suggests new parameters for the ansatz to lower the energy.

- Geometry Optimization (Co-optimization): To find the molecular equilibrium geometry, embed the VQE energy evaluation within an outer classical optimization loop that varies the nuclear coordinates. For large molecules, a Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) framework can be used to fragment the problem, reducing qubit requirements while preserving accuracy [13].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Technique | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Rubidium-85 Atoms | The physical qubits; chosen for their single valence electron and favorable energy level structure [34] [29]. |

| Optical Tweezers | Laser beams that trap and individually position atoms into programmable arrays [34] [29]. |

| Rydberg Excitation Lasers | Lasers used to excite atoms to high-energy Rydberg states, enabling long-range interactions for multi-qubit gates [30] [29]. |

| Spatial Light Modulator (SLM) | A device that shapes laser beams to create dynamic patterns of optical tweezers, allowing for flexible qubit rearrangement [34]. |

| Optimal Control Pulses | Pre-calculated, shaped laser pulses that implement high-fidelity gates while being robust to noise and imperfections [28] [30]. |

| Machine Learning Decoder | Classical software component for quantum error correction, capable of identifying and correcting errors, including those from atom loss [31]. |

Workflow and System Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the typical experimental workflow for running a molecular simulation, from problem definition to result analysis.

Molecular Simulation Workflow

The core of the quantum processing unit (QPU) in a neutral-atom computer is based on the interaction between Rydberg atoms. The diagram below shows this logical relationship.

Multi-Qubit Gate Mechanism

FAQ 1: What is qubitized downfolding and what quantum resource advantage does it offer for molecular calculations? Qubitized downfolding is a quantum algorithm that utilizes tensor-factorized Hamiltonian downfolding to significantly improve quantum resource efficiency compared to current algorithms [35]. It enables the execution of practical industrial applications on present-day quantum resources by reducing the qubit count and circuit depth required for accurate molecular simulations, moving beyond the limitations of small molecules typically used in proof-of-concept studies [35] [36].

FAQ 2: Why are polymorphic systems and macrocyclic drugs particularly challenging for classical computational methods? Polymorphic systems, like the ROY compound, possess multiple crystalline forms, posing severe challenges for standard density functional theory (DFT) methods [35]. Macrocyclic drugs, such as Paritaprevir, exhibit high conformational flexibility due to their large, cyclic structures beyond the traditional "rule of 5," making them prone to exist in multiple conformations and polymorphs, which complicates accurate property prediction [37].

FAQ 3: Our team is experiencing failed docking results with a macrocyclic drug candidate. Could the molecular conformation be the issue? Yes. Molecular docking results are highly sensitive to the conformation of the ligand. For instance, MicroED structures of Paritaprevir revealed distinct polymorphic forms (Form α and Form β) with different conformations of the macrocyclic core and substituents [37]. Molecular docking showed that only the Form β conformation fit well into the active site pocket of the HCV NS3/4A serine protease target and could interact with the catalytic triad, whereas Form α did not fit into the pocket [37]. Ensure the simulation uses a biologically relevant conformation.

FAQ 4: What are the key experimental validation steps after a quantum simulation predicts a stable polymorph or conformation? Experimental validation is crucial. For polymorphic systems, techniques like microcrystal electron diffraction (MicroED) can be used to determine distinct polymorphic crystal forms from the same powder preparation, revealing different conformations and packing patterns [37]. For drug-target interactions, experimental binding assays are necessary to validate computational predictions, as demonstrated in a quantum machine learning study targeting the KRAS protein [38].

Key Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Qubitized Downfolding for Molecular Simulation

This protocol outlines the application of qubitized downfolding to molecular systems, as highlighted in recent case studies [35].

- System Selection: Identify a target molecule with complexity challenging for standard DFT (e.g., a flexible macrocycle or a polymorphic system).

- Hamiltonian Downfolding: Apply tensor-factorized Hamiltonian downfolding to the molecular system. This step reduces the complexity of the electronic Hamiltonian, focusing on the most chemically relevant degrees of freedom.

- Qubitization: Map the downfolded Hamiltonian to a qubit representation suitable for execution on a quantum processor.

- Quantum Simulation: Execute the algorithm on quantum hardware or a simulator to compute the system's energy and properties.

- Validation: Compare the results against classical reference methods (e.g., high-level DFT) and, where possible, experimental data (e.g., crystal structures from MicroED [37]) to validate accuracy and resource efficiency.

Protocol: Microcrystal Electron Diffraction (MicroED) for Polymorph Structure Determination

This protocol details the experimental method used to resolve the structures of polymorphic macrocyclic drugs, providing validation data for computational predictions [37].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a powder sample of the target molecule and deposit it onto a transmission electron microscopy (TEM) grid, allowing solvents to evaporate.

- Grid Screening: Use low-magnification whole-grid atlases to identify microcrystals of different morphologies, which may indicate different polymorphs.

- Data Collection: For identified microcrystals, collect MicroED data continuously as the sample stage is rotated (e.g., from -30° to +30° at 1° per second) using a low electron dose rate.

- Data Processing: Process the collected data using standard crystallographic software (e.g., XDS).

- Structure Solving and Refinement: Solve the ab initio structure and refine it to high resolution.

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Quantum Resource Efficiency of Qubitized Downfolding

| Metric | Traditional Quantum Algorithms | Qubitized Downfolding | Improvement Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qubit Count | High | Significantly Reduced | Enabled simulation of previously intractable molecules like glycolic acid (C₂H₄O₃) [36]. |

| Circuit Depth | Deep | More shallow circuits | Achieved through co-optimization frameworks, reducing computational cost [36]. |

| Algorithmic Efficiency | Lower | High | Demonstrated significantly improved resource efficiency in case studies on ROY and Paritaprevir [35]. |

Table 2: Experimental Polymorph Data for Paritaprevir from MicroED [37]

| Parameter | Form α | Form β |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal Morphology | Needle-like | Rod-like |

| Space Group | P2â‚2â‚2â‚ | P2â‚2â‚2â‚ |

| Unit Cell Dimensions | a = 5.09 Ã…, b = 15.61 Ã…, c = 50.78 Ã… | a = 10.56 Ã…, b = 12.32 Ã…, c = 31.73 Ã… |

| Refinement Resolution | 0.85 Ã… | 0.95 Ã… |

| Intramolecular H-bond | Amide N (core) to Cyclopropyl sulfonamide (2.2 Ã…) | Amide carbonyl (core) to Amide N (cyclopropyl sulfonamide) (2.0 Ã…) |

| Solvent-Accessible Void | 7.6% | 2.2% |

| Docking Result | Does not fit target pocket | Fits well into HCV NS3/4A protease active site |

Workflow Visualization

Quantum Simulation Workflow

MicroED Structure Determination

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational and Experimental Resources

| Item/Resource | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Qubitized Downfolding Algorithm | Enables resource-efficient quantum simulation of complex molecular systems. | Key for polymorph stability studies and macrocyclic drug conformation analysis [35]. |

| Hybrid Quantum-Classical Framework (e.g., DMET+VQE) | Partitions large molecules for simulation on near-term quantum devices; co-optimizes geometry and circuit parameters [36]. | Used for large-scale molecule geometry optimization (e.g., glycolic acid) [36]. |

| Microcrystal Electron Diffraction (MicroED) | Determines atomic-level crystal structures from micron-sized crystals, bypassing the need for large single crystals [37]. | Critical for experimentally resolving different polymorphic forms (e.g., Paritaprevir Form α/β) [37]. |

| Knowledge Graph-Enhanced Learning (e.g., KANO) | Incorporates fundamental chemical knowledge (e.g., element properties, functional groups) to improve molecular property prediction and model interpretability [39]. | Provides a chemical prior to guide models and can improve prediction performance on tasks like molecular property prediction [39]. |

| Quantum Machine Learning (QML) | Enhances classical machine learning models for drug discovery by leveraging quantum effects for better pattern recognition in chemical space [38]. | Used to identify novel ligands for difficult drug targets like KRAS, with experimental validation [38]. |

| 4-Chlorophthalazine-1-carbonitrile | 4-Chlorophthalazine-1-carbonitrile |

Quantum Computing for Protein-Ligand Binding and Hydration Analysis

Troubleshooting Guides

Quantum Algorithm Implementation

Q1: My quantum circuit for docking site identification is failing to converge. What could be wrong? This issue often stems from problems with quantum state labeling, ansatz selection, or hardware noise. The quantum docking algorithm relies on expanded protein lattice models and modified Grover searches to identify interaction sites [40].

Problem: Low probability of correct answer.

- Solution: Verify the quantum state labeling for interaction sites is correctly implemented. Ensure the oracle in the modified Grover algorithm properly marks valid docking sites.

- Prevention: Test the oracle function on a quantum simulator first with a small, known protein model.

Problem: Results are inconsistent between simulator and real hardware.

- Solution: Implement readout error mitigation and use shorter-depth circuits. The algorithm has been successfully tested on both simulators and real quantum computers [40].

- Prevention: Design circuits with native gate sets for your target hardware to reduce compilation overhead.

Q2: How can I improve the accuracy of my hybrid quantum-neural wavefunction calculations? The pUNN (paired Unitary Coupled-Cluster with Neural Networks) framework addresses accuracy limitations from hardware noise and algorithmic constraints [41].

Problem: Energy calculations not reaching chemical accuracy.

- Solution: Ensure your neural network correctly accounts for contributions from unpaired configurations while the quantum circuit learns the quantum phase structure.

- Prevention: Use the combined pUCCD circuit with neural networks, which maintains low qubit count (N qubits) and shallow depth while achieving accuracy comparable to UCCSD and CCSD(T) [41].

Problem: Training is unstable or diverging.

- Solution: Implement the particle number conservation mask in the neural network to eliminate non-physical configurations [41].

- Prevention: Use the prescribed perturbation circuit with single-qubit rotation gates Ry (angle 0.2) to divert ancilla qubits from |0⟩ state.

Hardware and Performance Optimization

Q3: My quantum calculations for hydration analysis are exceeding coherence time limits. How can I optimize them? This common challenge in NISQ devices requires strategic circuit design and resource management.

Problem: Circuit depth too high for reliable execution.

- Solution: For protein hydration placement, use the hybrid quantum-classical approach where classical algorithms generate water density data and quantum algorithms handle precise placement in challenging regions [42].

- Prevention: Implement the qDRIVE method that distributes tasks across high-throughput computing resources, allowing asynchronous parallel execution that minimizes quantum computation time [4].

Problem: Excessive errors in molecular resonance identification.

- Solution: Use the integrated qDRIVE deflation resonance identification method that breaks problems into interconnected tasks executed simultaneously on quantum and classical resources [4].

- Prevention: For 2-4 qubit calculations, expect errors below 1%; employ error mitigation strategies for higher-qubit calculations where errors may reach 35% on current hardware [4].

Q4: How can I reduce the parameter count in hybrid quantum-classical binding affinity models? Hybrid Quantum Neural Networks (HQNNs) specifically address parameter efficiency while maintaining performance [43].

Problem: Model too large for practical deployment.

- Solution: Replace classical neural network components with hybrid quantum models using data re-uploading schemes. The HQDeepDTAF model demonstrates comparable performance with reduced parameters [43].

- Prevention: Use hybrid embedding schemes to reduce required qubit counts while maintaining expressivity.

Problem: Poor generalization on new protein-ligand pairs.

- Solution: Ensure your model architecture includes separate modules for entire protein, local pocket, and ligand SMILES information, with HQNN substitution in appropriate components [43].

- Prevention: Leverage classical regression networks for final prediction tasks while using quantum components for feature extraction.

Experimental Protocols

Core Methodologies for Quantum-Enhanced Binding and Hydration Analysis

Protocol 1: Quantum Algorithm for Protein-Ligand Docking Site Identification This protocol implements the quantum docking site identification algorithm tested on both simulators and real quantum computers [40].

Table 1: Quantum Docking Algorithm Components

| Component | Description | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Lattice Model | Expanded to include protein-ligand interactions | Must properly represent interaction space |

| Quantum State Labeling | Specialized labeling for interaction sites | Critical for algorithm success |